Static Defence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Trench warfare is a type of

Trench warfare is a type of

Field works have existed for as long as there have been armies.

Field works have existed for as long as there have been armies.

Although technology had dramatically changed the nature of warfare by 1914, the armies of the major combatants had not fully absorbed the implications. Fundamentally, as the range and rate of fire of rifled small-arms increased, a defender shielded from enemy fire (in a trench, at a house window, behind a large rock, or behind other cover) was often able to kill several approaching foes before they closed around the defender's position. Attacks across open ground became even more dangerous after the introduction of rapid-firing

Although technology had dramatically changed the nature of warfare by 1914, the armies of the major combatants had not fully absorbed the implications. Fundamentally, as the range and rate of fire of rifled small-arms increased, a defender shielded from enemy fire (in a trench, at a house window, behind a large rock, or behind other cover) was often able to kill several approaching foes before they closed around the defender's position. Attacks across open ground became even more dangerous after the introduction of rapid-firing  Digging-in when defending a position was a standard practice by the start of WWI. To attack frontally was to court crippling losses, so an outflanking operation was the preferred method of attack against an entrenched enemy. After the Battle of the Aisne in September 1914, an extended series of attempted flanking moves, and matching extensions to the fortified defensive lines, developed into the "

Digging-in when defending a position was a standard practice by the start of WWI. To attack frontally was to court crippling losses, so an outflanking operation was the preferred method of attack against an entrenched enemy. After the Battle of the Aisne in September 1914, an extended series of attempted flanking moves, and matching extensions to the fortified defensive lines, developed into the "

Early World War I trenches were simple. They lacked traverses, and according to pre-war doctrine were to be packed with men fighting shoulder to shoulder. This doctrine led to heavy casualties from artillery fire. This vulnerability, and the length of the front to be defended, soon led to frontline trenches being held by fewer men. The defenders augmented the trenches themselves with barbed wire strung in front to impede movement; wiring parties went out every night to repair and improve these forward defences.

The small, improvised trenches of the first few months grew deeper and more complex, gradually becoming vast areas of interlocking defensive works. They resisted both artillery bombardment and mass infantry assault. Shell-proof dugouts became a high priority.

A well-developed trench had to be at least deep to allow men to walk upright and still be protected.

There were three standard ways to dig a trench: entrenching, sapping, and tunneling. Entrenching, where a man would stand on the surface and dig downwards, was most efficient, as it allowed a large digging party to dig the full length of the trench simultaneously. However, entrenching left the diggers exposed above ground and hence could only be carried out when free of observation, such as in a rear area or at night.

Early World War I trenches were simple. They lacked traverses, and according to pre-war doctrine were to be packed with men fighting shoulder to shoulder. This doctrine led to heavy casualties from artillery fire. This vulnerability, and the length of the front to be defended, soon led to frontline trenches being held by fewer men. The defenders augmented the trenches themselves with barbed wire strung in front to impede movement; wiring parties went out every night to repair and improve these forward defences.

The small, improvised trenches of the first few months grew deeper and more complex, gradually becoming vast areas of interlocking defensive works. They resisted both artillery bombardment and mass infantry assault. Shell-proof dugouts became a high priority.

A well-developed trench had to be at least deep to allow men to walk upright and still be protected.

There were three standard ways to dig a trench: entrenching, sapping, and tunneling. Entrenching, where a man would stand on the surface and dig downwards, was most efficient, as it allowed a large digging party to dig the full length of the trench simultaneously. However, entrenching left the diggers exposed above ground and hence could only be carried out when free of observation, such as in a rear area or at night.

The banked earth on the lip of the trench facing the enemy was called the

The banked earth on the lip of the trench facing the enemy was called the

/ref> Often a steel plate was used with a "keyhole", which had a rotating piece to cover the loophole when not in use. German snipers used armour-piercing bullets that allowed them to penetrate loopholes. Another means to see over the parapet was the trench periscope – in its simplest form, just a stick with two angled pieces of mirror at the top and bottom. A number of armies made use of the

Very early in the war, British defensive doctrine suggested a main trench system of three parallel lines, interconnected by communications trenches. The point at which a communications trench intersected the front trench was of critical importance, and it was usually heavily fortified. The front trench was lightly garrisoned and typically occupied in force only during "stand to" at dawn and dusk. Between behind the front trench was located the support (or "travel") trench, to which the garrison would retreat when the front trench was bombarded.

Between further to the rear was located the third reserve trench, where the reserve troops could amass for a counter-attack if the front trenches were captured. This defensive layout was soon rendered obsolete as the power of artillery grew; however, in certain sectors of the front, the support trench was maintained as a decoy to attract the enemy bombardment away from the front and reserve lines. Fires were lit in the support line to make it appear inhabited and any damage done immediately repaired.

Temporary trenches were also built. When a major attack was planned, assembly trenches would be dug near the front trench. These were used to provide a sheltered place for the waves of attacking troops who would follow the first waves leaving from the front trench. "Saps" were temporary, unmanned, often dead-end utility trenches dug out into no-man's land. They fulfilled a variety of purposes, such as connecting the front trench to a listening post close to the enemy wire or providing an advance "jumping-off" line for a surprise attack. When one side's front line bulged towards the opposition, a salient was formed. The concave trench line facing the salient was called a "re-entrant." Large salients were perilous for their occupants because they could be assailed from three sides.

Behind the front system of trenches there were usually at least two more partially prepared trench systems, kilometres to the rear, ready to be occupied in the event of a retreat. The Germans often prepared multiple redundant trench systems; in 1916 their

Very early in the war, British defensive doctrine suggested a main trench system of three parallel lines, interconnected by communications trenches. The point at which a communications trench intersected the front trench was of critical importance, and it was usually heavily fortified. The front trench was lightly garrisoned and typically occupied in force only during "stand to" at dawn and dusk. Between behind the front trench was located the support (or "travel") trench, to which the garrison would retreat when the front trench was bombarded.

Between further to the rear was located the third reserve trench, where the reserve troops could amass for a counter-attack if the front trenches were captured. This defensive layout was soon rendered obsolete as the power of artillery grew; however, in certain sectors of the front, the support trench was maintained as a decoy to attract the enemy bombardment away from the front and reserve lines. Fires were lit in the support line to make it appear inhabited and any damage done immediately repaired.

Temporary trenches were also built. When a major attack was planned, assembly trenches would be dug near the front trench. These were used to provide a sheltered place for the waves of attacking troops who would follow the first waves leaving from the front trench. "Saps" were temporary, unmanned, often dead-end utility trenches dug out into no-man's land. They fulfilled a variety of purposes, such as connecting the front trench to a listening post close to the enemy wire or providing an advance "jumping-off" line for a surprise attack. When one side's front line bulged towards the opposition, a salient was formed. The concave trench line facing the salient was called a "re-entrant." Large salients were perilous for their occupants because they could be assailed from three sides.

Behind the front system of trenches there were usually at least two more partially prepared trench systems, kilometres to the rear, ready to be occupied in the event of a retreat. The Germans often prepared multiple redundant trench systems; in 1916 their

In the

In the

A specialised group of fighters called ''trench sweepers'' (''Nettoyeurs de Tranchées'' or ''Zigouilleurs'') evolved to fight within the trenches. They cleared surviving enemy personnel from recently overrun trenches and made clandestine raids into enemy trenches to gather intelligence. Volunteers for this dangerous work were often exempted from participation in frontal assaults over open ground and from routine work like filling sandbags, draining trenches, and repairing barbed wire in no-man's land. When allowed to choose their own weapons, many selected grenades, knives and pistols.

A specialised group of fighters called ''trench sweepers'' (''Nettoyeurs de Tranchées'' or ''Zigouilleurs'') evolved to fight within the trenches. They cleared surviving enemy personnel from recently overrun trenches and made clandestine raids into enemy trenches to gather intelligence. Volunteers for this dangerous work were often exempted from participation in frontal assaults over open ground and from routine work like filling sandbags, draining trenches, and repairing barbed wire in no-man's land. When allowed to choose their own weapons, many selected grenades, knives and pistols.  The Germans embraced the machine gun from the outset—in 1904, sixteen units were equipped with the 'Maschinengewehr'—and the machine gun crews were the elite infantry units; these units were attached to Jaeger (light infantry) battalions. By 1914, British infantry units were armed with two

The Germans embraced the machine gun from the outset—in 1904, sixteen units were equipped with the 'Maschinengewehr'—and the machine gun crews were the elite infantry units; these units were attached to Jaeger (light infantry) battalions. By 1914, British infantry units were armed with two  One

One

Mortars, which lobbed a shell in a high arc over a relatively short distance, were widely used in trench fighting for harassing the forward trenches, for cutting wire in preparation for a raid or attack, and for destroying dugouts, saps and other entrenchments. In 1914, the British fired a total of 545 mortar shells; in 1916, they fired over 6,500,000. Similarly, howitzers, which fire on a more direct arc than mortars, raised in number from over 1,000 shells in 1914, to over 4,500,000 in 1916. The smaller numerical difference in mortar rounds, as opposed to howitzer rounds, is presumed by many to be related to the expanded costs of manufacturing the larger and more resource intensive howitzer rounds.

The main British mortar was the Stokes, a precursor of the modern mortar. It was a light mortar, simple in operation, and capable of a rapid rate of fire by virtue of the propellant cartridge being attached to the base shell. To fire the Stokes mortar, the round was simply dropped into the tube, where the percussion cartridge was detonated when it struck the firing pin at the bottom of the barrel, thus being launched. The Germans used a range of mortars. The smallest were grenade-throwers (' Granatenwerfer') which fired the stick grenades which were commonly used. Their medium trench-mortars were called mine-throwers ('

Mortars, which lobbed a shell in a high arc over a relatively short distance, were widely used in trench fighting for harassing the forward trenches, for cutting wire in preparation for a raid or attack, and for destroying dugouts, saps and other entrenchments. In 1914, the British fired a total of 545 mortar shells; in 1916, they fired over 6,500,000. Similarly, howitzers, which fire on a more direct arc than mortars, raised in number from over 1,000 shells in 1914, to over 4,500,000 in 1916. The smaller numerical difference in mortar rounds, as opposed to howitzer rounds, is presumed by many to be related to the expanded costs of manufacturing the larger and more resource intensive howitzer rounds.

The main British mortar was the Stokes, a precursor of the modern mortar. It was a light mortar, simple in operation, and capable of a rapid rate of fire by virtue of the propellant cartridge being attached to the base shell. To fire the Stokes mortar, the round was simply dropped into the tube, where the percussion cartridge was detonated when it struck the firing pin at the bottom of the barrel, thus being launched. The Germans used a range of mortars. The smallest were grenade-throwers (' Granatenwerfer') which fired the stick grenades which were commonly used. Their medium trench-mortars were called mine-throwers ('

An individual unit's time in a front-line trench was usually brief; from as little as one day to as much as two weeks at a time before being relieved. The 31st Australian Battalion once spent 53 days in the line at

An individual unit's time in a front-line trench was usually brief; from as little as one day to as much as two weeks at a time before being relieved. The 31st Australian Battalion once spent 53 days in the line at  Even when in the front line, the typical

Even when in the front line, the typical  Some sectors of the front saw little activity throughout the war, making life in the trenches comparatively easy. When the

Some sectors of the front saw little activity throughout the war, making life in the trenches comparatively easy. When the  A sector of the front would be allocated to an army

A sector of the front would be allocated to an army

World War I saw large-scale use of poison gases. At the start of the war, the gas agents used were relatively weak and delivery unreliable, but by mid-war advances in this chemical warfare reached horrifying levels.

The first methods of employing gas was by releasing it from a cylinder when the wind was favourable. This was prone to miscarry if the direction of the wind was misjudged. Also, the cylinders needed to be positioned in the front trenches where they were likely to be ruptured by enemy bombardment. Later, gas was delivered directly to enemy trenches by artillery or mortar shell, reducing friendly casualties significantly. Lingering agents could still affect friendly troops that advanced to enemy trenches following its use.

Early on, soldiers made improvised

World War I saw large-scale use of poison gases. At the start of the war, the gas agents used were relatively weak and delivery unreliable, but by mid-war advances in this chemical warfare reached horrifying levels.

The first methods of employing gas was by releasing it from a cylinder when the wind was favourable. This was prone to miscarry if the direction of the wind was misjudged. Also, the cylinders needed to be positioned in the front trenches where they were likely to be ruptured by enemy bombardment. Later, gas was delivered directly to enemy trenches by artillery or mortar shell, reducing friendly casualties significantly. Lingering agents could still affect friendly troops that advanced to enemy trenches following its use.

Early on, soldiers made improvised

Tanks were developed by the British and French as a means to attack enemy trenches, by combining heavy firepower ( machine guns or light artillery guns), protection from

Tanks were developed by the British and French as a means to attack enemy trenches, by combining heavy firepower ( machine guns or light artillery guns), protection from

At the Battle of Sevastopol,

At the Battle of Sevastopol,

Trench warfare has been infrequent in recent wars. When two large armoured armies meet, the result has generally been mobile warfare of the type which developed in World War II. However, trench warfare re-emerged in the latter stages of the Chinese Civil War (Huaihai Campaign) and the Korean War (from July 1951 to its end).

During the Cold War, NATO forces routinely trained to fight through extensive works called "Soviet-style trench systems", named after the Warsaw Pact's complex systems of field fortifications, an extension of Soviet field entrenching practices for which they were famous in their Great Patriotic War (the Eastern Front of World War II).

In the Iran–Iraq War, both armies lacked training in

Trench warfare has been infrequent in recent wars. When two large armoured armies meet, the result has generally been mobile warfare of the type which developed in World War II. However, trench warfare re-emerged in the latter stages of the Chinese Civil War (Huaihai Campaign) and the Korean War (from July 1951 to its end).

During the Cold War, NATO forces routinely trained to fight through extensive works called "Soviet-style trench systems", named after the Warsaw Pact's complex systems of field fortifications, an extension of Soviet field entrenching practices for which they were famous in their Great Patriotic War (the Eastern Front of World War II).

In the Iran–Iraq War, both armies lacked training in

In the Russo-Ukrainian War, to safeguard and assert their territories, both Ukrainian and Pro-Russian conflict in Ukraine, Russian proxy forces have resorted to digging small trench networks and engaging in warfare akin to the trench fights of World War I in some aspects. This involves soldiers spending extended periods within trenches, employing cement mixers and excavators to construct tunnel networks and deep bunkers for added protection. After the Minsk Protocol, Minsk peace agreements the front lines did not move significantly until the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, as both sides dug elaborate networks of trenches and deep bunkers for protection and the two sides mostly fired mortars and sniper shots at each other.

The 2022 invasion also saw the construction of trench lines and similar defensive structures by both sides, especially after the end of the initial Russian offensive, resulting in a static war of attrition with slow advances and artillery duels, especially in Donetsk Oblast. Pictures of muddy trenches, stumps of charred trees in a shell-pocked landscape made the Battle of Bakhmut emblematic for its trench warfare conditions, with neither side making any significant breakthroughs amid hundreds of casualties reported daily. Modern technology has adapted to the trench warfare, and use of drones and mobile networks is common. The battlefield has been described as "World War I with 21st-century Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance".

In the Russo-Ukrainian War, to safeguard and assert their territories, both Ukrainian and Pro-Russian conflict in Ukraine, Russian proxy forces have resorted to digging small trench networks and engaging in warfare akin to the trench fights of World War I in some aspects. This involves soldiers spending extended periods within trenches, employing cement mixers and excavators to construct tunnel networks and deep bunkers for added protection. After the Minsk Protocol, Minsk peace agreements the front lines did not move significantly until the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, as both sides dug elaborate networks of trenches and deep bunkers for protection and the two sides mostly fired mortars and sniper shots at each other.

The 2022 invasion also saw the construction of trench lines and similar defensive structures by both sides, especially after the end of the initial Russian offensive, resulting in a static war of attrition with slow advances and artillery duels, especially in Donetsk Oblast. Pictures of muddy trenches, stumps of charred trees in a shell-pocked landscape made the Battle of Bakhmut emblematic for its trench warfare conditions, with neither side making any significant breakthroughs amid hundreds of casualties reported daily. Modern technology has adapted to the trench warfare, and use of drones and mobile networks is common. The battlefield has been described as "World War I with 21st-century Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance".

In Depth: A century of mud and fire

BBC News, 27 June 2006 * Historic films and photos showing ''"Trench Warfare in World War I"'' a

europeanfilmgateway.eu

* World War I Tanks a

Tanks Encyclopedia

YouTube video of excavated and restored British WWI trench near Ypres

Preserved Trenches Sanctuary Wood, Ypres, Belgium

Trench Warfare , Apocalypse World War

Trench warfare: Britannica.com article

YouTube video of Hill 60 on the Messines Ridge, site of a huge underground explosion

* William Philpott

Warfare 1914–1918

in

* Jeffrey LaMonica

Infantry

in

* Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau

Weapons

in

* Markus Pöhlmann

Close Combat Weapons

in

* Nathan Watanabe

Hand Grenade

in

{{Authority control Trench warfare, Military doctrines Military strategy Subterranea (geography) Warfare by type

Trench warfare is a type of

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare

Land warfare or ground warfare is the process of military operations eventuating in combat that takes place predominantly on the battlespace land surface of the planet.

Land warfare is categorized by the use of large numbers of combat personne ...

using occupied lines largely comprising military trenches, in which combatant

Combatant is the legal status of a person entitled to directly participate in hostilities during an armed conflict, and may be intentionally targeted by an adverse party for their participation in the armed conflict. Combatants are not afforded i ...

s are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

. It became archetypically associated with World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

(1914–1918), when the Race to the Sea

The Race to the Sea (; , ) took place from 17 September to 19 October 1914 during the First World War, after the Battle of the Frontiers () and the German Empire, German advance into France. The invasion had been stopped at the First Battle of ...

rapidly expanded trench use on the Western Front starting in September 1914..

Trench warfare proliferated when a revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

in firepower

Firepower is the military capability to direct force at an enemy. It involves the whole range of potential weapons. The concept is generally taught as one of the three key principles of modern warfare wherein the enemy forces are destroyed or ...

was not matched by similar advances in mobility

Mobility may refer to:

Social sciences and humanities

* Economic mobility, ability of individuals or families to improve their economic status

* Geographic mobility, the measure of how populations and goods move over time

* Mobilities, a conte ...

, resulting in a grueling form of warfare in which the defender held the advantage. On the Western Front in 1914–1918, both sides constructed elaborate trench, underground, and dugout

Dugout may refer to:

* Dugout (shelter), an underground shelter

* Dugout (boat), a logboat

* Dugout (smoking), a marijuana container

Sports

* In bat-and-ball sports, a dugout is one of two areas where players of the home or opposing teams sit whe ...

systems opposing each other along a front

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* '' The Front'', 1976 film

Music

* The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and ...

, protected from assault by barbed wire

Roll of modern agricultural barbed wire

Barbed wire, also known as barb wire or bob wire (in the Southern and Southwestern United States), is a type of steel fencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the ...

. The area between opposing trench lines (known as " no man's land") was fully exposed to artillery fire from both sides. Attacks, even if successful, often sustained severe casualties

A casualty (), as a term in military usage, is a person in military service, combatant or non-combatant, who becomes unavailable for duty due to any of several circumstances, including death, injury, illness, missing, capture or desertion.

In c ...

.

The development of armoured warfare

Armoured warfare or armored warfare (American English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences), is the use of armoured fighting vehicles in modern warfare. It is a major component of modern Milita ...

and combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare that seeks to integrate different combat arms of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects—for example, using infantry and armoured warfare, armour in an Urban warfare, urban environment in ...

tactics permitted static lines to be bypassed and defeated, leading to the decline of trench warfare after the war. Following World War I, "trench warfare" became a byword for stalemate, attrition, siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

s, and futility in conflict.

Precursors

Field works have existed for as long as there have been armies.

Field works have existed for as long as there have been armies. Roman legions

The Roman legion (, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of Roman citizens serving as legionaries. During the Roman Republic the manipular legion comprised 4,200 infantry and 300 cavalry. After the Marian reforms in 1 ...

, when in the presence of an enemy, entrenched camps nightly when on the move. The Roman general Belisarius

BelisariusSometimes called Flavia gens#Later use, Flavius Belisarius. The name became a courtesy title by the late 4th century, see (; ; The exact date of his birth is unknown. March 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under ...

had his soldiers dig a trench as part of the Battle of Dara

The Battle of Dara was fought between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Sasanians in 530 AD. It was one of the battles of the Iberian War.

Procopius's account of this engagement is among the most detailed descriptions of a late Roman battle.

...

in 530 AD.

Trench warfare was also documented during the defence of Medina

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

in a siege known as the Battle of the Trench (627 AD). The architect of the plan was Salman the Persian

Salman Farsi (; ) was a Persian religious scholar and one of the companions of Muhammad. As a practicing Zoroastrian, he dedicated much of his early life to studying to become a magus, after which he began travelling extensively throughout Weste ...

who suggested digging a trench to defend Medina.

There are examples of trench digging as a defensive measure during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, such as during the Piedmontese Civil War

The Piedmontese Civil War, also known as the Savoyard Civil War, was a conflict for control of the Savoyard state from 1639 to 1642. Although not formally part of the 1635 to 1659 Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659), Franco-Spanish War, Savoy's strat ...

, where it was documented that on the morning of May 12, 1640, the French soldiers, having already captured the left bank of the Po river

The Po ( , ) is the longest river in Italy. It flows eastward across northern Italy, starting from the Cottian Alps. The river's length is , or if the Maira (river), Maira, a right bank tributary, is included. The headwaters of the Po are forme ...

and gaining control of the bridge connecting the two banks of the river, and wanting to advance to the Capuchin Monastery of the Monte, deciding that their position wasn't secure enough for their liking, then choose to advance on a double attack on the trenches, but were twice repelled. Eventually, on the third attempt, the French broke through and the defenders were forced to flee with the civilian population, seeking the sanctuary of the local Catholic church, the Santa Maria al Monte dei Cappuccini

The Church of Santa Maria al Monte dei Cappuccini is a late-Renaissance-style church on a hill overlooking the River Po just south of the bridge of Piazza Vittorio Veneto in Turin, Italy. It was built for the Capuchin Order; construction began in ...

, in Turin, also known at that time as the Capuchin Monastery of the Monte.

In early modern warfare

Early modern warfare is the era of warfare during early modern period following medieval warfare. It is associated with the start of the widespread use of gunpowder and the development of suitable weapons to use the explosive, including art ...

, troops used field works to block possible lines of advance. Examples include the Lines of Stollhofen, built at the start of the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

of 1702–1714, the Lines of Weissenburg

The Lines of Weissenburg, or Lines of Wissembourg,Note: also known as the Weissenburg Lines or Lignes de Wissembourg. The alternative spellings are derived from the German and French were entrenched works — an earthen rampart dotted with smal ...

built under the orders of the Duke of Villars in 1706, the Lines of Ne Plus Ultra during the winter of 1710–1711, and the Lines of Torres Vedras

The Lines of Torres Vedras were lines of forts and other military defences built in secrecy to defend Lisbon during the Peninsular War. Named after the nearby town of Torres Vedras, they were ordered by Arthur Wellesley, Viscount Wellington, c ...

in 1809 and 1810.

Trenches at the Siege of Vicksburg 1863

In the New Zealand Wars

The New Zealand Wars () took place from 1845 to 1872 between the Colony of New Zealand, New Zealand colonial government and allied Māori people, Māori on one side, and Māori and Māori-allied settlers on the other. Though the wars were initi ...

(1845–1872), the Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

developed elaborate trench and bunker

A bunker is a defensive military fortification designed to protect people and valued materials from falling bombs, artillery, or other attacks. Bunkers are almost always underground, in contrast to blockhouses which are mostly above ground. T ...

systems as part of fortified areas known as pā

The word pā (; often spelled pa in English) can refer to any Māori people, Māori village or defensive settlement, but often refers to hillforts – fortified settlements with palisades and defensive :wikt:terrace, terraces – and also to fo ...

, employing them successfully as early as the 1840s to withstand British artillery bombardments. According to one British observer, "the fence round the pa is covered between every paling with loose bunches of flax, against which the bullets fall and drop; in the night they repair every hole made by the guns". These systems included firing trenches, communication trenches, tunnels

A tunnel is an underground or undersea passageway. It is dug through surrounding soil, earth or rock, or laid under water, and is usually completely enclosed except for the two portals common at each end, though there may be access and ve ...

, and anti-artillery bunkers. The Ngāpuhi

Ngāpuhi (also known as Ngāpuhi-Nui-Tonu or Ngā Puhi) is a Māori iwi associated with the Northland regions of New Zealand centred in the Hokianga, the Bay of Islands, and Whangārei.

According to the 2023 New Zealand census, the estimate ...

pā Ruapekapeka

The Battle of Ruapekapeka took place from late December 1845 to mid-January 1846 between British forces, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Despard, and Māori warriors of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe), led by Hōne Heke and Te Ruki Kawi ...

is often considered to be the most sophisticated and technologically impressive by historians. British casualties, such as at Gate Pa

Gate Pa or Gate Pā is a suburb of Tauranga, in the Bay of Plenty Region of New Zealand's North Island.

It is the location of the Battle of Gate Pā in the 1864 Tauranga campaign of the New Zealand Wars.

Demographics

Gate Pa covers and had ...

in 1864 and the Battle of Ohaeawai in 1845, suggested that contemporary weaponry, such as musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually dis ...

s and cannon, proved insufficient to dislodge defenders from a trench system. There has been an academic debate surrounding this since the 1980s, when in his book ''The New Zealand Wars,'' historian James Belich claimed that Northern Māori had effectively invented trench warfare during the first stages of the New Zealand Wars. However, this has been criticised by a few academics of the same period, with Gavin McLean noting that while the Māori had certainly adapted pa to suit contemporary weaponry, many historians have dismissed Belich's claim as "baseless... revisionism". Others more recently have said that while it is clear the Māori did not invent trench warfare ''first''—Māori did invent trench-based defences without any offshore aid— some believe they may have influenced 20th-century methods of trench design identified with it.

The Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

(1853–1856) saw "massive trench works and trench warfare", even though "the modernity of the trench war was not immediately apparent to the contemporaries".

Union and Confederate armies employed field works and extensive trench systems in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

(1861–1865) — most notably in the sieges of Vicksburg (1863) and Petersburg (1864–1865), the latter of which saw the first use by the Union Army of the rapid-fire Gatling gun

The Gatling gun is a rapid-firing multiple-barrel firearm invented in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling of North Carolina. It is an early machine gun and a forerunner of the modern electric motor-driven rotary cannon.

The Gatling gun's operatio ...

, the important precursor to modern-day machine guns. Trenches were also utilized in the Paraguayan War

The Paraguayan War (, , ), also known as the War of the Triple Alliance (, , ), was a South American war that lasted from 1864 to 1870. It was fought between Paraguay and the Triple Alliance of Argentina, the Empire of Brazil, and Uruguay. It wa ...

(which started in 1864), the Second Anglo-Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic an ...

(1899–1902), and the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

(1904–1905).

Adoption

Although technology had dramatically changed the nature of warfare by 1914, the armies of the major combatants had not fully absorbed the implications. Fundamentally, as the range and rate of fire of rifled small-arms increased, a defender shielded from enemy fire (in a trench, at a house window, behind a large rock, or behind other cover) was often able to kill several approaching foes before they closed around the defender's position. Attacks across open ground became even more dangerous after the introduction of rapid-firing

Although technology had dramatically changed the nature of warfare by 1914, the armies of the major combatants had not fully absorbed the implications. Fundamentally, as the range and rate of fire of rifled small-arms increased, a defender shielded from enemy fire (in a trench, at a house window, behind a large rock, or behind other cover) was often able to kill several approaching foes before they closed around the defender's position. Attacks across open ground became even more dangerous after the introduction of rapid-firing artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

, exemplified by the "French 75", and high explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An exp ...

fragmentation rounds. The increases in firepower had outstripped the ability of infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

(or even cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

) to cover the ground between firing lines, and the ability of armour to withstand fire. It would take a revolution in mobility to change that.

The French and German armies adopted different tactical doctrines: the French relied on the attack with speed and surprise, and the Germans relied on firepower

Firepower is the military capability to direct force at an enemy. It involves the whole range of potential weapons. The concept is generally taught as one of the three key principles of modern warfare wherein the enemy forces are destroyed or ...

, investing heavily in howitzer

The howitzer () is an artillery weapon that falls between a cannon (or field gun) and a mortar. It is capable of both low angle fire like a field gun and high angle fire like a mortar, given the distinction between low and high angle fire break ...

s and machine guns. The British lacked an official tactical doctrine, with an officer corps that rejected theory in favour of pragmatism.

While the armies expected to use entrenchments and cover, they did not allow for the effect of defences in depth. They required a deliberate approach to seizing positions from which fire support could be given for the next phase of the attack, rather than a rapid move to break the enemy's line. It was assumed that artillery could still destroy entrenched troops, or at least suppress them sufficiently for friendly infantry and cavalry to manoeuvre.

Digging-in when defending a position was a standard practice by the start of WWI. To attack frontally was to court crippling losses, so an outflanking operation was the preferred method of attack against an entrenched enemy. After the Battle of the Aisne in September 1914, an extended series of attempted flanking moves, and matching extensions to the fortified defensive lines, developed into the "

Digging-in when defending a position was a standard practice by the start of WWI. To attack frontally was to court crippling losses, so an outflanking operation was the preferred method of attack against an entrenched enemy. After the Battle of the Aisne in September 1914, an extended series of attempted flanking moves, and matching extensions to the fortified defensive lines, developed into the "race to the sea

The Race to the Sea (; , ) took place from 17 September to 19 October 1914 during the First World War, after the Battle of the Frontiers () and the German Empire, German advance into France. The invasion had been stopped at the First Battle of ...

", by the end of which German and Allied armies had produced a matched pair of trench lines from the Swiss

Swiss most commonly refers to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Swiss may also refer to: Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss Café, an old café located ...

border in the south to the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

coast of Belgium.

By the end of October 1914, the whole front in Belgium and France had solidified into lines of trenches, which lasted until the last weeks of the war. Mass infantry assaults were futile in the face of artillery fire, as well as rapid rifle and machine-gun fire. Both sides concentrated on breaking up enemy attacks and on protecting their own troops by digging deep into the ground. After the buildup of forces in 1915, the Western Front became a stalemated struggle between equals, to be decided by attrition. Frontal assaults, and their associated casualties, became inevitable because the continuous trench lines had no open flanks. Casualties of the defenders matched those of the attackers, as vast reserves were expended in costly counter-attacks or exposed to the attacker's massed artillery. There were periods in which rigid trench warfare broke down, such as during the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (; ), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and the French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 Nove ...

, but the lines never moved very far. The war would be won by the side that was able to commit the last reserves to the Western Front. Trench warfare prevailed on the Western Front until the Germans launched their Spring Offensive on 21 March 1918. Trench warfare also took place on other front

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* '' The Front'', 1976 film

Music

* The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and ...

s, including in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

.

Armies were also limited by logistics. The heavy use of artillery meant that ammunition expenditure was far higher in WWI than in any previous conflict. Horses and carts were insufficient for transporting large quantities over long distances, so armies had trouble moving far from railheads. This greatly slowed advances, making it impossible for either side to achieve a breakthrough that would change the war. This situation would only be altered in WWII with greater use of motorized vehicles.

Construction

Early World War I trenches were simple. They lacked traverses, and according to pre-war doctrine were to be packed with men fighting shoulder to shoulder. This doctrine led to heavy casualties from artillery fire. This vulnerability, and the length of the front to be defended, soon led to frontline trenches being held by fewer men. The defenders augmented the trenches themselves with barbed wire strung in front to impede movement; wiring parties went out every night to repair and improve these forward defences.

The small, improvised trenches of the first few months grew deeper and more complex, gradually becoming vast areas of interlocking defensive works. They resisted both artillery bombardment and mass infantry assault. Shell-proof dugouts became a high priority.

A well-developed trench had to be at least deep to allow men to walk upright and still be protected.

There were three standard ways to dig a trench: entrenching, sapping, and tunneling. Entrenching, where a man would stand on the surface and dig downwards, was most efficient, as it allowed a large digging party to dig the full length of the trench simultaneously. However, entrenching left the diggers exposed above ground and hence could only be carried out when free of observation, such as in a rear area or at night.

Early World War I trenches were simple. They lacked traverses, and according to pre-war doctrine were to be packed with men fighting shoulder to shoulder. This doctrine led to heavy casualties from artillery fire. This vulnerability, and the length of the front to be defended, soon led to frontline trenches being held by fewer men. The defenders augmented the trenches themselves with barbed wire strung in front to impede movement; wiring parties went out every night to repair and improve these forward defences.

The small, improvised trenches of the first few months grew deeper and more complex, gradually becoming vast areas of interlocking defensive works. They resisted both artillery bombardment and mass infantry assault. Shell-proof dugouts became a high priority.

A well-developed trench had to be at least deep to allow men to walk upright and still be protected.

There were three standard ways to dig a trench: entrenching, sapping, and tunneling. Entrenching, where a man would stand on the surface and dig downwards, was most efficient, as it allowed a large digging party to dig the full length of the trench simultaneously. However, entrenching left the diggers exposed above ground and hence could only be carried out when free of observation, such as in a rear area or at night. Sapping

Sapping is a term used in siege operations to describe the digging of a covered trench (a "sap") to approach a besieged place without danger from the enemy's fire. (verb) The purpose of the sap is usually to advance a besieging army's position ...

involved extending the trench by digging away at the end face. The diggers were not exposed, but only one or two men could work on the trench at a time. Tunnelling was like sapping except that a "roof" of soil was left in place while the trench line was established and then removed when the trench was ready to be occupied. The guidelines for British trench construction stated that it would take 450 men 6 hours at night to complete of front-line trench system. Thereafter, the trench would require constant maintenance to prevent deterioration caused by weather or shelling.

Trenchmen were a specialized unit of trench excavators and repairmen. They usually dug or repaired in groups of four with an escort of two armed soldiers. Trenchmen were armed with one 1911 semi-automatic pistol, and were only utilized when either a new trench needed to be dug or expanded quickly, or when a trench was destroyed by artillery fire. Trenchmen were trained to dig with incredible speed; in a dig of three to six hours they could accomplish what would take a normal group of frontline infantry soldiers around two days. Trenchmen were usually looked down upon by fellow soldiers because they did not fight. They were usually called cowards because if they were attacked while digging, they would abandon the post and flee to safety. They were instructed to do this though because through the war there were only around 1,100 trained trenchmen. They were highly valued only by officers higher on the chain of command.

Components

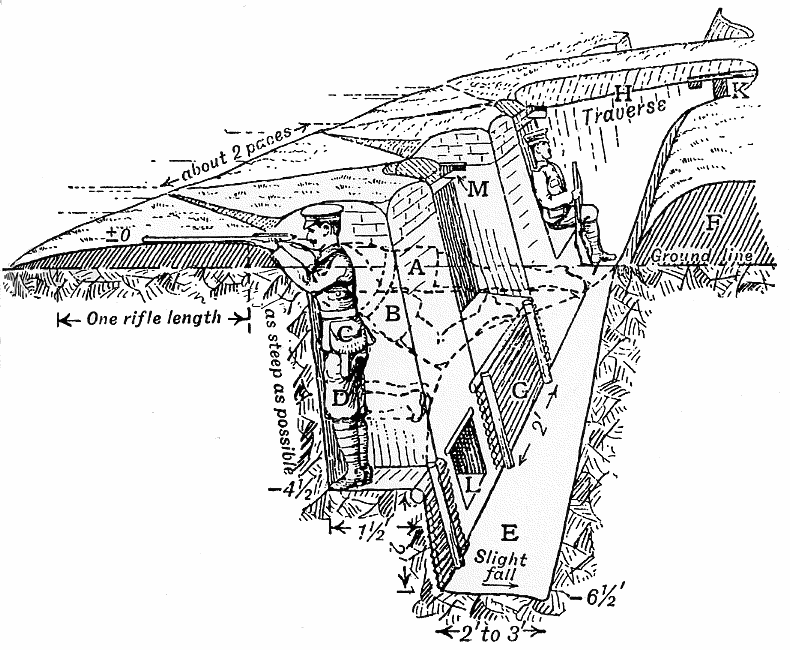

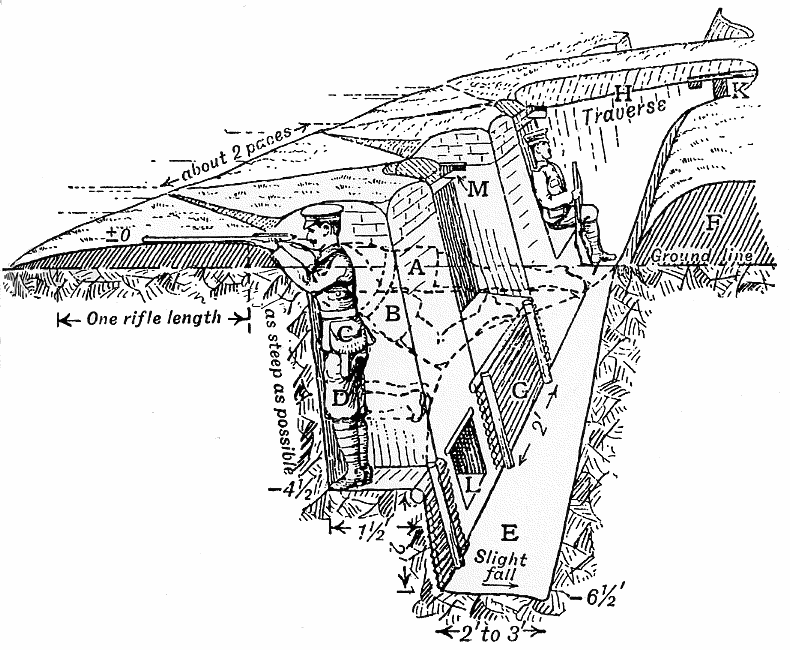

The banked earth on the lip of the trench facing the enemy was called the

The banked earth on the lip of the trench facing the enemy was called the parapet

A parapet is a barrier that is an upward extension of a wall at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony, walkway or other structure. The word comes ultimately from the Italian ''parapetto'' (''parare'' 'to cover/defend' and ''petto'' 'chest/brea ...

and had a fire step. The embanked rear lip of the trench was called the parados

A parados is a bank of earth built behind a trench or military emplacement to protect soldier

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a Conscription, conscripted or volunteer Enlisted rank, enlisted person, a non-c ...

, which protected the soldier's back from shells falling behind the trench. The sides of the trench were often revetted with sandbag

A sandbag or dirtbag is a bag or sack made of Hessian (cloth), hessian (burlap), polypropylene or other sturdy materials that is filled with sand or soil and used for such purposes as flood control, military fortification in trenches and bunke ...

s, wire mesh

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) is a comprehensive controlled vocabulary for the purpose of indexing journal articles and books in the life sciences. It serves as a thesaurus of index terms that facilitates searching. Created and updated by th ...

, wooden frames and sometimes roofs. The floor of the trench was usually covered by wooden duckboards

A boardwalk (alternatively board walk, boarded path, or promenade) is an elevated footpath, walkway, or causeway typically built with wooden planks, which functions as a type of low water bridge or small viaduct that enables pedestrians to bet ...

. In later designs the floor might be raised on a wooden frame to provide a drainage channel underneath. Due to the substantial casualties taken from indirect fire, some trenches were reinforced with corrugated metal roofs over the top as an improvised defence from shrapnel.

The static movement of trench warfare and a need for protection from sniper

A sniper is a military or paramilitary marksman who engages targets from positions of concealment or at distances exceeding the target's detection capabilities. Snipers generally have specialized training and are equipped with telescopic si ...

s created a requirement for loopholes both for discharging firearms and for observation.Trench Loopholes, Le Linge/ref> Often a steel plate was used with a "keyhole", which had a rotating piece to cover the loophole when not in use. German snipers used armour-piercing bullets that allowed them to penetrate loopholes. Another means to see over the parapet was the trench periscope – in its simplest form, just a stick with two angled pieces of mirror at the top and bottom. A number of armies made use of the

periscope rifle

A periscope rifle is a rifle that has been adapted to enable it to be sighted by the use of a periscope. This enables the shooter to remain concealed below cover. The device was independently invented by a number of individuals in response to the ...

, which enabled soldiers to snipe at the enemy without exposing themselves over the parapet, although at the cost of reduced shooting accuracy. The device is most associated with Australian and New Zealand troops at Gallipoli, where the Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic of Turkey

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic lang ...

held the high ground.

Dugouts

Dugout may refer to:

* Dugout (shelter), an underground shelter

* Dugout (boat), a logboat

* Dugout (smoking), a marijuana container

Sports

* In bat-and-ball sports, a dugout is one of two areas where players of the home or opposing teams sit whe ...

of varying degrees of comfort were built in the rear of the support trench. British dugouts were usually deep. The Germans, who had based their knowledge on studies of the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

,. made something of a science out of designing and constructing defensive works. They used reinforced concrete to construct deep, shell-proof, ventilated dugouts, as well as strategic strongpoints. German dugouts were typically much deeper, usually a minimum of deep and sometimes dug three stories down, with concrete staircases to reach the upper levels.

Layout

Trenches were never straight but were dug in azigzag

A zigzag is a pattern made up of small corners at variable angles, though constant within the zigzag, tracing a path between two parallel lines; it can be described as both jagged and fairly regular.

In geometry, this pattern is described as a ...

ging or stepped pattern, with all straight sections generally kept less than ten yards. Later, this evolved to have the combat trenches broken into distinct fire bays connected by traverses. While this isolated the view of friendly soldiers along their own trench, this ensured the entire trench could not be enfiladed if the enemy gained access at any one point; or if a bomb, grenade, or shell landed in the trench, the blast could not travel far.

Very early in the war, British defensive doctrine suggested a main trench system of three parallel lines, interconnected by communications trenches. The point at which a communications trench intersected the front trench was of critical importance, and it was usually heavily fortified. The front trench was lightly garrisoned and typically occupied in force only during "stand to" at dawn and dusk. Between behind the front trench was located the support (or "travel") trench, to which the garrison would retreat when the front trench was bombarded.

Between further to the rear was located the third reserve trench, where the reserve troops could amass for a counter-attack if the front trenches were captured. This defensive layout was soon rendered obsolete as the power of artillery grew; however, in certain sectors of the front, the support trench was maintained as a decoy to attract the enemy bombardment away from the front and reserve lines. Fires were lit in the support line to make it appear inhabited and any damage done immediately repaired.

Temporary trenches were also built. When a major attack was planned, assembly trenches would be dug near the front trench. These were used to provide a sheltered place for the waves of attacking troops who would follow the first waves leaving from the front trench. "Saps" were temporary, unmanned, often dead-end utility trenches dug out into no-man's land. They fulfilled a variety of purposes, such as connecting the front trench to a listening post close to the enemy wire or providing an advance "jumping-off" line for a surprise attack. When one side's front line bulged towards the opposition, a salient was formed. The concave trench line facing the salient was called a "re-entrant." Large salients were perilous for their occupants because they could be assailed from three sides.

Behind the front system of trenches there were usually at least two more partially prepared trench systems, kilometres to the rear, ready to be occupied in the event of a retreat. The Germans often prepared multiple redundant trench systems; in 1916 their

Very early in the war, British defensive doctrine suggested a main trench system of three parallel lines, interconnected by communications trenches. The point at which a communications trench intersected the front trench was of critical importance, and it was usually heavily fortified. The front trench was lightly garrisoned and typically occupied in force only during "stand to" at dawn and dusk. Between behind the front trench was located the support (or "travel") trench, to which the garrison would retreat when the front trench was bombarded.

Between further to the rear was located the third reserve trench, where the reserve troops could amass for a counter-attack if the front trenches were captured. This defensive layout was soon rendered obsolete as the power of artillery grew; however, in certain sectors of the front, the support trench was maintained as a decoy to attract the enemy bombardment away from the front and reserve lines. Fires were lit in the support line to make it appear inhabited and any damage done immediately repaired.

Temporary trenches were also built. When a major attack was planned, assembly trenches would be dug near the front trench. These were used to provide a sheltered place for the waves of attacking troops who would follow the first waves leaving from the front trench. "Saps" were temporary, unmanned, often dead-end utility trenches dug out into no-man's land. They fulfilled a variety of purposes, such as connecting the front trench to a listening post close to the enemy wire or providing an advance "jumping-off" line for a surprise attack. When one side's front line bulged towards the opposition, a salient was formed. The concave trench line facing the salient was called a "re-entrant." Large salients were perilous for their occupants because they could be assailed from three sides.

Behind the front system of trenches there were usually at least two more partially prepared trench systems, kilometres to the rear, ready to be occupied in the event of a retreat. The Germans often prepared multiple redundant trench systems; in 1916 their Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

* Somme, Queensland, Australia

* Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), ...

front featured two complete trench systems, one kilometre apart, with a third partially completed system a further kilometre behind. This duplication made a decisive breakthrough virtually impossible. In the event that a section of the first trench system was captured, a "switch" trench would be dug to connect the second trench system to the still-held section of the first.

Wire

The use of lines ofbarbed wire

Roll of modern agricultural barbed wire

Barbed wire, also known as barb wire or bob wire (in the Southern and Southwestern United States), is a type of steel fencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the ...

, razor wire

Barbed tape or razor wire is a mesh of metal strips with sharp edges whose purpose is to prevent trespassing by humans or to secure facilities such as prisons where there is a risk of escape. The term "razor wire", through long usage, has gener ...

, and other wire obstacle

In the military science of fortification, wire obstacles are defensive obstacles made from barbed wire, barbed tape or concertina wire. They are designed to disrupt, delay and generally slow down an attacking enemy. During the time that the att ...

s, in belts deep or more, is effective in stalling infantry travelling across the battlefield. Although the barbs or razors might cause minor injuries, the purpose was to entangle the limbs of enemy soldiers, forcing them to stop and methodically pull or work the wire off, likely taking several seconds, or even longer. This is deadly when the wire is emplaced at points of maximum exposure to concentrated enemy firepower, in plain sight of enemy fire bays and machine guns. The combination of wire and firepower was the cause of most failed attacks in trench warfare and their very high casualties. Liddell Hart

Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart (31 October 1895 – 29 January 1970), commonly known throughout most of his career as Captain B. H. Liddell Hart, was a British soldier, military historian, and military theorist. He wrote a series of military his ...

identified barbed wire and the machine gun as the elements that had to be broken to regain a mobile battlefield.

A basic wire line could be created by draping several strands of barbed wire between wooden posts driven into the ground. Loose lines of wire can be more effective in entangling than tight ones, and it was common to use the coils of barbed wire as delivered only partially stretched out, called concertina wire

Concertina wire or Dannert wire is a type of barbed wire or razor wire that is formed in large coils which can be expanded like a concertina. In conjunction with plain barbed wire (and/or razor wire/tape) and steel pickets, it is most oft ...

. Placing and repairing wire in no man's land relied on stealth, usually done at night by special wiring parties, who could also be tasked with secretly sabotaging enemy wires. The screw picket

A screw picket is a metal device which is used to secure objects to the ground. Today, screw pickets are used widely to temporarily "picket" dogs. They are also used to graze animals such as sheep, goats, and horses. Screw pickets are also used ...

, invented by the Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

and later adopted by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

during the war, was quieter than driving stakes. Wire often stretched the entire length of a battlefield's trench line, in multiple lines, sometimes covering a depth or more.

Methods to defeat it were rudimentary. Prolonged artillery bombardment could damage them, but not reliably. The first soldier meeting the wire could jump onto the top of it, hopefully depressing it enough for those that followed to get over him; this still took at least one soldier out of action for each line of wire. In World War I, British and Commonwealth forces relied on wire cutter

Diagonal pliers (also known as wire cutters or diagonal cutting pliers, or under many regional names) are pliers intended for the cutting of wire or small stock, rather than grabbing or turning. The plane defined by the cutting edges of the jaw ...

s, which proved unable to cope with the heavier gauge German wire. The Bangalore torpedo

A Bangalore torpedo is an explosive charge placed within one or several connected tubes. It is used by combat engineers to clear obstacles that would otherwise require them to approach directly, possibly under fire. It is sometimes colloquially ...

was adopted by many armies, and continued in use past the end of World War II.

The barbed wire used differed between nations; the German wire was heavier gauge, and British wire cutters, designed for the thinner native product, were unable to cut it.''Canada's Army'', p. 79.

Geography

The confined, static, and subterranean nature of trench warfare resulted in it developing its own peculiar form ofgeography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

. In the forward zone, the conventional transport infrastructure of roads and rail were replaced by the network of trenches and trench railways

A trench railway was a type of railway that represented military adaptation of early 20th-century railway technology to the problem of keeping soldiers supplied during the static trench warfare phase of World War I. The large concentrations of so ...

. The critical advantage that could be gained by holding the high ground meant that minor hills and ridges gained enormous significance. Many slight hills and valleys were so subtle as to have been nameless until the front line encroached upon them. Some hills were named for their height in metres, such as Hill 60. A farmhouse, windmill, quarry, or copse of trees would become the focus of a determined struggle simply because it was the largest identifiable feature. However, it would not take the artillery long to obliterate it, so that thereafter it became just a name on a map.

The battlefield of Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

presented numerous problems for the practice of trench warfare, especially for the Allied forces, mainly British and Canadians, who were often compelled to occupy the low ground. Heavy shelling quickly destroyed the network of ditches and water channels which had previously drained this low-lying area of Belgium. In most places, the water table

The water table is the upper surface of the phreatic zone or zone of saturation. The zone of saturation is where the pores and fractures of the ground are saturated with groundwater, which may be fresh, saline, or brackish, depending on the loc ...

was only a metre or so below the surface, meaning that any trench dug in the ground would quickly flood. Consequently, many "trenches" in Flanders were actually above ground and constructed from massive breastworks of sandbags filled with clay. Initially, both the parapet and parados of the trench were built in this way, but a later technique was to dispense with the parados for much of the trench line, thus exposing the rear of the trench to fire from the reserve line in case the front was breached.

In the

In the Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

, trench warfare even stretched onto vertical slopes and deep into the mountains, to heights of above sea level. The Ortler

Ortler (; ) is, at above sea level, the highest mountain in the Eastern Alps outside the Bernina Range. It is the main peak of the Ortler Range. It is the highest point of the Southern Limestone Alps, of South Tyrol in Italy, of Tyrol overall ...

had an artillery position on its summit near the front line. The trench-line management and trench profiles had to be adapted to the rough terrain, hard rock, and harsh weather conditions. Many trench systems were constructed within glaciers such as the Adamello-Presanella

The Adamello-Presanella Alps Alpine group is a mountain range in the Southern Limestone Alps mountain group of the Eastern Alps. It is located in northern Italy, in the provinces of Trentino and Brescia. The name stems from its highest peaks: Ad ...

group or the famous city below the ice on the Marmolada

Marmolada (Ladin language, Ladin: ''Marmolèda''; German language, German: ''Marmolata'', ) is a mountain in northeastern Italy and the highest mountain of the Dolomites (a section of the Alps). It lies between the borders of Trentino and Ven ...

in the Dolomites

The Dolomites ( ), also known as the Dolomite Mountains, Dolomite Alps or Dolomitic Alps, are a mountain range in northeastern Italy. They form part of the Southern Limestone Alps and extend from the River Adige in the west to the Piave Va ...

.

Observation

Observing the enemy in trench warfare was difficult, prompting the invention of technology such as the camouflage tree.No man's land

The space between the opposing trenches was referred to as " no man's land" and varied in width depending on the battlefield. On the Western Front it was typically between , though only onVimy Ridge

The Battle of Vimy Ridge was part of the Battle of Arras, in the Pas-de-Calais department of France, during the First World War. The main combatants were the four divisions of the Canadian Corps in the First Army, against three divisions of ...

.

After the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line

The Hindenburg Line (, Siegfried Position) was a German Defense line, defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front in France during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to ...

in March 1917, no man's land stretched to over a kilometre in places. At the "Quinn's Post

Quinn's Post Cemetery is a Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery from World War I in the former Anzac sector of the Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey. The battles at Gallipoli, some of whose participating soldiers are buried at this cemetery, w ...

" in the cramped confines of the Anzac battlefield at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

, the opposing trenches were only apart and the soldiers in the trenches constantly threw hand grenade

A grenade is a small explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a Shell (projectile), shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A mod ...

s at each other. On the Eastern Front and in the Middle East, the areas to be covered were so vast, and the distances from the factories supplying shells, bullets, concrete and barbed wire so great, trench warfare in the West European style often did not occur.

Weaponry

Infantry weapons and machine guns

At the start of the First World War, the standardinfantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

soldier's primary weapons were the rifle

A rifle is a long gun, long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting and higher stopping power, with a gun barrel, barrel that has a helical or spiralling pattern of grooves (rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus o ...

and bayonet

A bayonet (from Old French , now spelt ) is a -4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, when it wa ... , now spelt ) is a knife, dagger">knife">-4; we might wonder whethe ...

; other weapons got less attention. Especially for the British, what hand grenade

A grenade is a small explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a Shell (projectile), shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A mod ...

s were issued tended to be few in numbers and less effective. This emphasis began to shift as soon as trench warfare began; militaries rushed improved grenades into mass production, including rifle grenade

A rifle grenade is a grenade that uses a rifle-based launcher to permit a longer effective range than would be possible if the grenade were thrown by hand.

The practice of projecting grenades with rifle-mounted launchers was first widely used dur ...

s.

The hand grenade came to be one of the primary infantry weapons of trench warfare. Both sides were quick to raise specialist grenadier groups. The grenade enabled a soldier to engage the enemy without exposing himself to fire, and it did not require precise accuracy to kill or maim. Another benefit was that if a soldier could get close enough to the trenches, enemies hiding in trenches could be attacked. The Germans and Turks were well equipped with grenades from the start of the war, but the British, who had ceased using grenadiers in the 1870s and did not anticipate a siege war, entered the conflict with virtually none, so soldiers had to improvise bombs with whatever was available (see Jam Tin Grenade

The double cylinder, Nos. 8 and No. 9 hand grenades, also known as the "jam tins", are a type of improvised explosive device used by the British and Commonwealth forces, notably the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) in World War I. T ...

). By late 1915, the British Mills bomb

"Mills bomb" is the popular name for a series of British hand grenades which were designed by William Mills. They were the first modern fragmentation grenades used by the British Army and saw widespread use in the First and Second World Wars ...

had entered wide circulation, and by the end of the war 75 million had been used.

Since the troops were often not adequately equipped for trench warfare, improvised weapons were common in the first encounters, such as short wooden clubs and metal maces, spear

A spear is a polearm consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with Fire hardening, fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable materia ...

s, hatchet

A hatchet (from the Old French language, Old French , a diminutive form of ''hache'', 'axe' of Germanic origin) is a Tool, single-handed striking tool with a sharp blade on one side used to cut and split wood, and a hammerhead on the other side ...

s, hammer

A hammer is a tool, most often a hand tool, consisting of a weighted "head" fixed to a long handle that is swung to deliver an impact to a small area of an object. This can be, for example, to drive nail (fastener), nails into wood, to sh ...

s, entrenching tool

An entrenching tool (UK), intrenching tool (US), E-tool, or trenching tool is a digging tool used by military forces for a variety of military purposes. Survivalists, campers, hikers, and other outdoors groups have found it to be indispensable i ...

s, as well as trench knives and brass knuckles

Brass knuckles (also referred to as brass knucks, knuckledusters, iron fist and paperweight, among other names) are a melee weapon used primarily in Hand to hand combat, hand-to-hand combat. They are fitted and designed to be worn around the kn ...

. According to the semi-biographical war novel ''All Quiet on the Western Front

''All Quiet on the Western Front'' () is a semi-autobiographical novel by Erich Maria Remarque, a German veteran of World War I. The book describes the German soldiers' extreme physical and mental trauma during the war as well as the detachme ...

'', many soldiers preferred to use a sharpened spade

A spade is a tool primarily for digging consisting of a long handle and blade, typically with the blade narrower and flatter than the common shovel. Early spades were made of riven wood or of animal bones (often shoulder blades). After the a ...