seter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Transhumance is a type of

Transhumance is a type of

Khazanov categorizes nomadic forms of pastoralism into five groups as follows: "pure pastoral nomadism", "semi-nomadic pastoralism", "semi-sedentary pastoralism", "distant-pastures husbandry" and "seasonal transhumance". Eickelman does not make a distinction between transhumant pastoralism and seminomadism, but he clearly distinguishes between nomadic pastoralism and seminomadism.

Khazanov categorizes nomadic forms of pastoralism into five groups as follows: "pure pastoral nomadism", "semi-nomadic pastoralism", "semi-sedentary pastoralism", "distant-pastures husbandry" and "seasonal transhumance". Eickelman does not make a distinction between transhumant pastoralism and seminomadism, but he clearly distinguishes between nomadic pastoralism and seminomadism.

In the

In the

In Southern Italy, the practice of driving herds to hilly pasture in summer was also known in some parts of the regions l and has had a long-documented history until the 1950s and 1960s with the advent of alternative road transport.

In Southern Italy, the practice of driving herds to hilly pasture in summer was also known in some parts of the regions l and has had a long-documented history until the 1950s and 1960s with the advent of alternative road transport.

Transhumance is historically widespread throughout much of Spain, particularly in the regions of Castile, Leon and Extremadura, where nomadic cattle and sheep herders travel long distances in search of greener pastures in summer and warmer climatic conditions in winter. Spanish transhumance is the origin of numerous related cultures in the Americas such as the cowboys of the United States and the Gauchos of Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil.

A network of droveways, or , crosses the whole peninsula, running mostly south-west to north-east. They have been charted since ancient times, and classified according to width; the standard is between wide, with some (meaning ''royal droveways'') being wide at certain points. The land within the droveways is publicly owned and protected by law.

In some high valleys of the

Transhumance is historically widespread throughout much of Spain, particularly in the regions of Castile, Leon and Extremadura, where nomadic cattle and sheep herders travel long distances in search of greener pastures in summer and warmer climatic conditions in winter. Spanish transhumance is the origin of numerous related cultures in the Americas such as the cowboys of the United States and the Gauchos of Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil.

A network of droveways, or , crosses the whole peninsula, running mostly south-west to north-east. They have been charted since ancient times, and classified according to width; the standard is between wide, with some (meaning ''royal droveways'') being wide at certain points. The land within the droveways is publicly owned and protected by law.

In some high valleys of the

Transhumance in the

Transhumance in the

In Scandinavia, transhumance is practised to a certain extent; however, livestock are transported between pastures by motorised vehicles, changing the character of the movement. The

In Scandinavia, transhumance is practised to a certain extent; however, livestock are transported between pastures by motorised vehicles, changing the character of the movement. The

''Fulani'' is the Hausa word for the pastoral peoples of Nigeria belonging to the '' Fulbe'' migratory ethnic group. The ''Fulani'' rear the majority of Nigeria's cattle, traditionally estimated at 83% pastoral, 17% village cattle and 0.3% peri-urban). Text was copied from this source, which is available under

''Fulani'' is the Hausa word for the pastoral peoples of Nigeria belonging to the '' Fulbe'' migratory ethnic group. The ''Fulani'' rear the majority of Nigeria's cattle, traditionally estimated at 83% pastoral, 17% village cattle and 0.3% peri-urban). Text was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Cattle fulfil multiple roles in agro-pastoralist communities, providing meat, milk and draught power while sales of stock generate income and provide insurance against disasters. They also play a key role in status and prestige and for cementing social relationships such as kinship and marriage. For pastoralists, cattle represent the major household asset. Pastoralism, as a livelihood, is coming under increased pressure across Africa, due to changing social, economic, political and environmental conditions. Prior to the 1950s, a symbiotic relationship existed between pastoralists, crop farmers and their environment with pastoralists practising transhumance. During the dry season, pastoralists migrated to the southern parts of the Guinea savannah zone, where there was ample pasture and a lower density of crop farmers. In the wet season, these areas faced high challenge from African

The traditional economy of the

The traditional economy of the

Traditionally in the American West, shepherds spent most of the year with a sheep herd, searching for the best forage in each season. This type of shepherding peaked in the late nineteenth century. Cattle and sheep herds are generally based on private land, although this may be a small part of the total range when all seasons are included. Some farmers who raised sheep recruited Basque shepherds to care for the herds, including managing migration between grazing lands. Workers from Peru, Chile (often Native Americans), and Mongolia have now taken shepherd roles; the Basque have bought their own ranches or moved to urban jobs. Shepherds take the sheep into the mountains in the summer (documented in the 2009 film '' Sweetgrass'') and out on the desert in the winter, at times using crop stubble and pasture on private land when it is available. There are a number of different forms of transhumance in the United States:

The

Traditionally in the American West, shepherds spent most of the year with a sheep herd, searching for the best forage in each season. This type of shepherding peaked in the late nineteenth century. Cattle and sheep herds are generally based on private land, although this may be a small part of the total range when all seasons are included. Some farmers who raised sheep recruited Basque shepherds to care for the herds, including managing migration between grazing lands. Workers from Peru, Chile (often Native Americans), and Mongolia have now taken shepherd roles; the Basque have bought their own ranches or moved to urban jobs. Shepherds take the sheep into the mountains in the summer (documented in the 2009 film '' Sweetgrass'') and out on the desert in the winter, at times using crop stubble and pasture on private land when it is available. There are a number of different forms of transhumance in the United States:

The

Historical Archaeologies Of Transhumance Across Europe

Routledge, London, 2018. * Jones, Schuyler. ''Men of Influence: Social Control & Dispute Settlement in Waigal Valley, Afghanistan''. Seminar Press, London & New York, 1974.

Transhumance and 'The Waiting Zone' in North Africa

Limited traditional transhumance in Australia

Swiss land registry of alpine pastures (German)

The transhumance from Schnals Valley (Italy) to Ötz Valley (Austria)

{{Authority control

pastoralism

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as "livestock") are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands (pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The anim ...

or nomadism

Nomads are communities without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, Nomadic pastoralism, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and Merchant, trader nomads. In the twentieth century, ...

, a seasonal movement of livestock

Livestock are the Domestication, domesticated animals that are raised in an Agriculture, agricultural setting to provide labour and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, Egg as food, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The t ...

between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane

Montane ecosystems are found on the slopes of mountains. The alpine climate in these regions strongly affects the ecosystem because temperatures lapse rate, fall as elevation increases, causing the ecosystem to stratify. This stratification is ...

regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pasture

Pasture (from the Latin ''pastus'', past participle of ''pascere'', "to feed") is land used for grazing.

Types of pasture

Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, c ...

s in summer and lower valleys in winter. Herders have a permanent home, typically in valleys. Generally only the herd

A herd is a social group of certain animals of the same species, either wild or domestic. The form of collective animal behavior associated with this is called '' herding''. These animals are known as gregarious animals.

The term ''herd'' ...

s travel, with a certain number of people necessary to tend them, while the main population stays at the base. In contrast, movement in plains or plateaus ''(horizontal transhumance)'' is more susceptible to disruption by climatic, economic, or political change.

Traditional or fixed transhumance has occurred throughout the inhabited world, particularly Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and western Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

. It is often important to pastoralist societies, as the dairy

A dairy is a place where milk is stored and where butter, cheese, and other dairy products are made, or a place where those products are sold. It may be a room, a building, or a larger establishment. In the United States, the word may also des ...

products of transhumance flocks and herds (milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of lactating mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfeeding, breastfed human infants) before they are able to digestion, digest solid food. ...

, butter

Butter is a dairy product made from the fat and protein components of Churning (butter), churned cream. It is a semi-solid emulsion at room temperature, consisting of approximately 81% butterfat. It is used at room temperature as a spread (food ...

, yogurt

Yogurt (; , from , ; also spelled yoghurt, yogourt or yoghourt) is a food produced by bacterial Fermentation (food), fermentation of milk. Fermentation of sugars in the milk by these bacteria produces lactic acid, which acts on milk protein to ...

and cheese

Cheese is a type of dairy product produced in a range of flavors, textures, and forms by coagulation of the milk protein casein. It comprises proteins and fat from milk (usually the milk of cows, buffalo, goats or sheep). During prod ...

) may form much of the diet of such populations. In many languages there are words for the higher summer pastures, and frequently these words have been used as place names: e.g. hafod in Wales, shieling

A shieling () is a hut or collection of huts on a seasonal pasture high in the hills, once common in wild or sparsely populated places in Scotland. Usually rectangular with a doorway on the south side and few or no windows, they were often c ...

in Scotland, or alp in Germany, Austria and German-speaking regions of Switzerland.

Etymology and definition

The word ''transhumance'' comes from French and derives from theLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

words "across" and "ground". Literally, it means crossing the land. Transhumance developed on every inhabited continent

A continent is any of several large geographical regions. Continents are generally identified by convention (norm), convention rather than any strict criteria. A continent could be a single large landmass, a part of a very large landmass, as ...

. Although there are substantial cultural and technological variations, the underlying practices for taking advantage of remote seasonal pastures are similar linguistically.

Khazanov categorizes nomadic forms of pastoralism into five groups as follows: "pure pastoral nomadism", "semi-nomadic pastoralism", "semi-sedentary pastoralism", "distant-pastures husbandry" and "seasonal transhumance". Eickelman does not make a distinction between transhumant pastoralism and seminomadism, but he clearly distinguishes between nomadic pastoralism and seminomadism.

Khazanov categorizes nomadic forms of pastoralism into five groups as follows: "pure pastoral nomadism", "semi-nomadic pastoralism", "semi-sedentary pastoralism", "distant-pastures husbandry" and "seasonal transhumance". Eickelman does not make a distinction between transhumant pastoralism and seminomadism, but he clearly distinguishes between nomadic pastoralism and seminomadism.

In prehistory

There is evidence that transhumance was practised world-wide prior to recorded history: in Europe, isotope studies of livestock bones suggest that certain animals were moved seasonally. The prevalence of various groups ofHill people

Hill people, also referred to as mountain people, is a general term for people who live in the hills and mountains.

This includes all rugged land above and all land (including plateaus) above elevation.

The climate is generally harsh, with s ...

around the world suggests that indigenous knowledge regarding transhumance must have developed and survived over generations to allow for the acquisition of sufficient skills to thrive in mountainous regions. Most drovers are conversant with subsistence agriculture

Subsistence agriculture occurs when farmers grow crops on smallholdings to meet the needs of themselves and their families. Subsistence agriculturalists target farm output for survival and for mostly local requirements. Planting decisions occu ...

, pastoralism

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as "livestock") are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands (pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The anim ...

as well as forestry

Forestry is the science and craft of creating, managing, planting, using, conserving and repairing forests and woodlands for associated resources for human and Natural environment, environmental benefits. Forestry is practiced in plantations and ...

and frozen water and fast stream management

Management (or managing) is the administration of organizations, whether businesses, nonprofit organizations, or a Government agency, government bodies through business administration, Nonprofit studies, nonprofit management, or the political s ...

.

Europe

Alps

Balkans

In the

In the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, Albanians

The Albanians are an ethnic group native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, Albanian culture, culture, Albanian history, history and Albanian language, language. They are the main ethnic group of Albania and Kosovo, ...

, Greek Sarakatsani

The Sarakatsani (), also called Karakachani (), are an ethnic Greeks, Greek population subgroup who were traditionally Transhumance, transhumant shepherds, native to Greece, with a smaller presence in neighbouring Bulgaria, southern Albania, an ...

, Eastern Romance

The Eastern Romance languages are a group of Romance languages. The group comprises the Romanian language (Daco-Romanian), the Aromanian language and two other related minor languages, Megleno-Romanian and Istro-Romanian.

The extinct Dalmatia ...

(Romanians

Romanians (, ; dated Endonym and exonym, exonym ''Vlachs'') are a Romance languages, Romance-speaking ethnic group and nation native to Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Sharing a Culture of Romania, ...

, Aromanians

The Aromanians () are an Ethnic groups in Europe, ethnic group native to the southern Balkans who speak Aromanian language, Aromanian, an Eastern Romance language. They traditionally live in central and southern Albania, south-western Bulgari ...

, Megleno-Romanians

The Megleno-Romanians, also known as Meglenites (), Moglenite Vlachs or simply Vlachs (), are an Eastern Romance ethnic group, originally inhabiting seven villages in the Moglena region spanning the Pella and Kilkis regional units of Central ...

and Istro-Romanians

The Istro-Romanians ( or ) are a Romance languages, Romance ethnic group native to or associated with the Istria, Istrian Peninsula. Historically, they inhabited vast parts of it, as well as the western side of the island of Krk until 1875. Howe ...

) and Turkish Yörük peoples traditionally spent summer months in the mountains and returned to lower plains in the winter. When the area was part of the Austro-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

and Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

s, borders between Greece, Albania, Bulgaria and the former Yugoslavia were relatively unobstructed. In summer, some groups went as far north as the Balkan Mountains

The Balkan mountain range is located in the eastern part of the Balkan peninsula in Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It is conventionally taken to begin at the peak of Vrashka Chuka on the border between Bulgaria and Serbia. It then runs f ...

, and they would spend the winter on warmer plains in the vicinity of the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

.

The Morlach or Karavlachs were a population of Eastern Romance

The Eastern Romance languages are a group of Romance languages. The group comprises the Romanian language (Daco-Romanian), the Aromanian language and two other related minor languages, Megleno-Romanian and Istro-Romanian.

The extinct Dalmatia ...

shepherds ("ancestors" of the Istro-Romanians) who lived in the Dinaric Alps

The Dinaric Alps (), also Dinarides, are a mountain range in Southern Europe, Southern and Southcentral Europe, separating the continental Balkan Peninsula from the Adriatic Sea. They stretch from Italy in the northwest through Slovenia, Croatia ...

(western Balkans in modern use), constantly migrating in search of better pastures for their sheep flocks. But as national states appeared in the area of the former Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, new state borders were developed that divided the summer and winter habitats of many of the pastoral groups. These prevented easy movement across borders, particularly at times of war, which have been frequent.

Poland

In Poland transhumance is known as redyk, and is the ceremonial departure of shepherds with their flocks of sheep and shepherd dogs to graze in the mountain pastures (spring redyk), as well as their return from grazing (autumn redyk). In the local mountain dialect, autumn redyk is called uosod, which comes from the Polish word "uosiadć" (ôsawiedź), meaning “to return sheep to individual farms”. There is also a theory that it comes from the word uozchod (ôzchod), which means “the separation of sheep from individual gazdōwek (farms)”. In this word, there may have been a complete loss of the pronunciation of ch, which in thePodhale

Podhale (; ), sometimes referred to as the Polish Highlands, is Poland's southernmost region. The Podhale is located in the foothills of the Tatra range of the Carpathian Mountains. It is the most famous region of the Goral Lands which are a ...

dialect (Poland) in this type of positions is pronounced as a barely audible h (so-called sonorous h), similarly to the word schować, which in the highlander language is pronounced as sowa. In the Memoir of the Tatra Society from 1876, the way in which this is done is described: "(...) they herd sheep from the entire village to one agreed place, give them to the shepherds and shepherds one by one, then mix them together and count the number of the whole herd (flock). This is what they call "the reading". The reading is done in such a way that one juhas, holding the chaplet in his hand, puts one bead for each ten sheep counted. The second one takes one sheep from the flock and, as he lets it out of the fenced barracks, counts: one, two, three, etc. up to ten, and after each ten he calls out: "desat"

The leading of the sheep was preceded by magical procedures that were supposed to protect them from bad fate and from being enchanted. For this purpose, bonfires were lit and sheep were led through the fire. It began with the resurrection of the "holy fire" in the kolyba (shepherd's hut). Custom dictated that from that day on, it was to be kept burning continuously by the main shepherd – the shepherd. Next, the sheep were led around a small chevron or spruce tree stuck in the ground – the so-called mojka (which was supposed to symbolize the health and strength of everyone present in the hall) and they were fumigated with burning herbs and a połazzka brought to the sałasz. This was intended to cleanse them of diseases and prevent misfortune. Then the flock was herded around it three times, which was intended to concentrate the sheep into one group and prevent individual animals from escaping.

Baca's task was to pull the sheep behind him, helping himself with salt which he sprinkled on the flock. With the help of dogs and whistles, the Juhasi encouraged the herd and made sure that the sheep followed the shepherd. Sheep that fell outside the circle boded ill. It was believed that the number of sheep that fell outside the circle would die in the coming season.

The stay in the pasture (hala) begins on St. Wojciech's Day (23 April), and ends on Michaelmas Day (29 September).

This method of sheep grazing is a relic of transhumant agriculture, which was once very common in the Carpathians. (Carpathian transhumance agriculture).

In the pastoral culture in Poland, Redyk was perceived as the greatest village festival. Farmers who gave their sheep to a shepherd for the entire season, before grazing in the pastures, listed them (most often by marking them with notches on the shepherd's stick, stick or beam), marked them and placed them in a basket made of tynin. In the Memoir of the Tatra Society from 1876, the way in which this is done is described: "(...) they herd sheep from the entire village to one agreed place, give them to the shepherds and shepherds one by one, then mix them together and count the number of the whole herd (flock).

The sheep of all the shepherds were gathered in one place at the foot of the mountains, and then one large herd was driven to the szalas. The entrance to the hala was also particularly emphasized: there was shooting, honking and shouting all the way. This was intended to drive away evil spirits from their animals and to keep the entire herd together.

At the end of the ceremony, there was music and dancing together. The musicians played traditional instruments: gajdas and violins. To the accompaniment of music, the Sałashniks performed the oldest individual dance – the owiedziok, the owczarza, the kolomajka, the swinszczok, the masztołka.

Redyk included many local practices, rituals and celebrations. In modern time it is mainly a part of local traditional entertainment. The modern spring and autumn Redyk (sheep drive) has the character of a folkloric spectacle addressed to locals and tourists, but also to the highlanders themselves, who to identify with their traditions. Sometimes common redyk was organised also in Czechia, Slovakia and Romania. In Poland, the organisers was the Transhumant Pastoral Foundation.

Britain

Wales

In most parts ofWales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, farm workers and sometimes the farmer would spend the summer months at a hillside summer house, or (), where the livestock would graze. During the late autumn the farm family and workers would drive the flocks down to the valleys and stay at the main house or ().

This system of transhumance has generally not been practised for almost a century; it continued in Snowdonia

Snowdonia, or Eryri (), is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in North Wales. It contains all 15 mountains in Wales Welsh 3000s, over 3000 feet high, including the country's highest, Snowdon (), which i ...

after it ceased elsewhere in Wales, and remnants of the practice can still be found in rural farming communities in the region to this day. Both "Hafod" and "Hendref" survive in Wales as place names and house names and in one case as the name of a raw milk cow cheese (Hafod). Today, cattle and sheep that summer on many hill farms are still transported to lowland winter pastures, but by truck rather than being driven overland.

Scotland

In many hilly and mountainous areas of Scotland, agricultural workers spent summer months in bothies or ''shieling

A shieling () is a hut or collection of huts on a seasonal pasture high in the hills, once common in wild or sparsely populated places in Scotland. Usually rectangular with a doorway on the south side and few or no windows, they were often c ...

s'' ( or in Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic (, ; Endonym and exonym, endonym: ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic language, Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongs ...

). Major drovers' road

A drovers' road, drove road, droveway, or simply a drove, is a route for droving livestock on foot from one place to another, such as to marketplace, market or between summer and winter pasture (see transhumance). Many drovers' roads were anci ...

s in the eastern part of Scotland include the Cairnamounth, Elsick Mounth

The Elsick Mounth is an ancient trackway crossing the Grampian Mountains in the vicinity of Netherley, Scotland. This trackway was one of the few means of traversing the Grampian Mounth area in prehistoric and medieval times. The highest pass o ...

and Causey Mounth

The Causey Mounth is an ancient drovers' road over the coastal fringe of the Grampian Mountains in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. This route was developed around the 12th century Anno Domini, AD as the main highway between Stonehaven and Aberdeen, a ...

. This practice has largely stopped but was practised within living memory in the Hebrides

The Hebrides ( ; , ; ) are the largest archipelago in the United Kingdom, off the west coast of the Scotland, Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Ou ...

and in the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands (; , ) is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Scottish Lowlands, Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Scots language, Lowland Scots language replaced Scottish Gae ...

. Today much transhumance is carried out by truck, with upland

Upland or Uplands may refer to:

Geography

*Hill, an area of higher land, generally

*Highland, an area of higher land divided into low and high points

*Upland and lowland, conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level

*I ...

flocks being transported under agistment

Agistment originally referred specifically to the proceeds of pasturage in the king's forests. To agist is, in English law, to take cattle to graze, in exchange for payment (derived, via Anglo-Norman ''agister'', from the Old French ''gîte">g ...

to lower-lying pasture during winter.

England

Evidence exists of transhumance being practised in England since at least medieval times, fromCornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

in the south-west, through to the north of England. In the Lake District, hill sheep breeds, such as the Herdwick and Swaledale are moved between moor and valley in summer and winter. This led to a trait and system known as "hefting", whereby sheep and flock remain in the farmer's allotted area (heaf) of the commons, which is still practised.

Ireland

In Ireland, transhumance is known as "booleying". Transhumance pastures were known as , variously anglicised as , , or . These names survive in many place names such as Buaile h'Anraoi in Kilcommon parish, Erris, North Mayo, where the landscape still clearly shows the layout of therundale

The rundale system (apparently from the Irish Gaelic words "" which refers to the division of something and "", in the sense of apportionment) was a form of occupation of land in Ireland, somewhat resembling the English common field system. The ...

system of agriculture. The livestock, usually cattle, was moved from a permanent lowland village to summer pastures in the mountains. The appearance of "Summerhill" () in many place names also bears witness to the practice. This transfer alleviated pressure on the growing crops and provided fresh pasture for the livestock. Mentioned in the Brehon Laws

Early Irish law, also called Brehon law (from the old Irish word breithim meaning judge), comprised the statutes which governed everyday life in Early Medieval Ireland. They were partially eclipsed by the Norman invasion of 1169, but underwe ...

, booleying dates back to the Early Medieval

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Middle Ages of Europ ...

period or even earlier. The practice was widespread in the west of Ireland up until the time of the Second World War. Seasonal migration of workers to Scotland and England for the winter months superseded this ancient system, together with more permanent emigration to the United States.

Italy

In Southern Italy, the practice of driving herds to hilly pasture in summer was also known in some parts of the regions l and has had a long-documented history until the 1950s and 1960s with the advent of alternative road transport.

In Southern Italy, the practice of driving herds to hilly pasture in summer was also known in some parts of the regions l and has had a long-documented history until the 1950s and 1960s with the advent of alternative road transport. Drovers' road

A drovers' road, drove road, droveway, or simply a drove, is a route for droving livestock on foot from one place to another, such as to marketplace, market or between summer and winter pasture (see transhumance). Many drovers' roads were anci ...

s, or , up to wide and more than long, permitted the passage and grazing of herds, principally sheep, and attracted regulation by law and the establishment of a mounted police force as far back as the 17th century. The tratturi remain public property and subject to conservation by the law protecting cultural heritage. The Molise

Molise ( , ; ; , ) is a Regions of Italy, region in Southern Italy. Until 1963, it formed part of the region of Abruzzi e Molise together with Abruzzo. The split, which did not become effective until 1970, makes Molise the newest region in Ital ...

region candidates the tratturi to the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

as a world heritage.

Spain

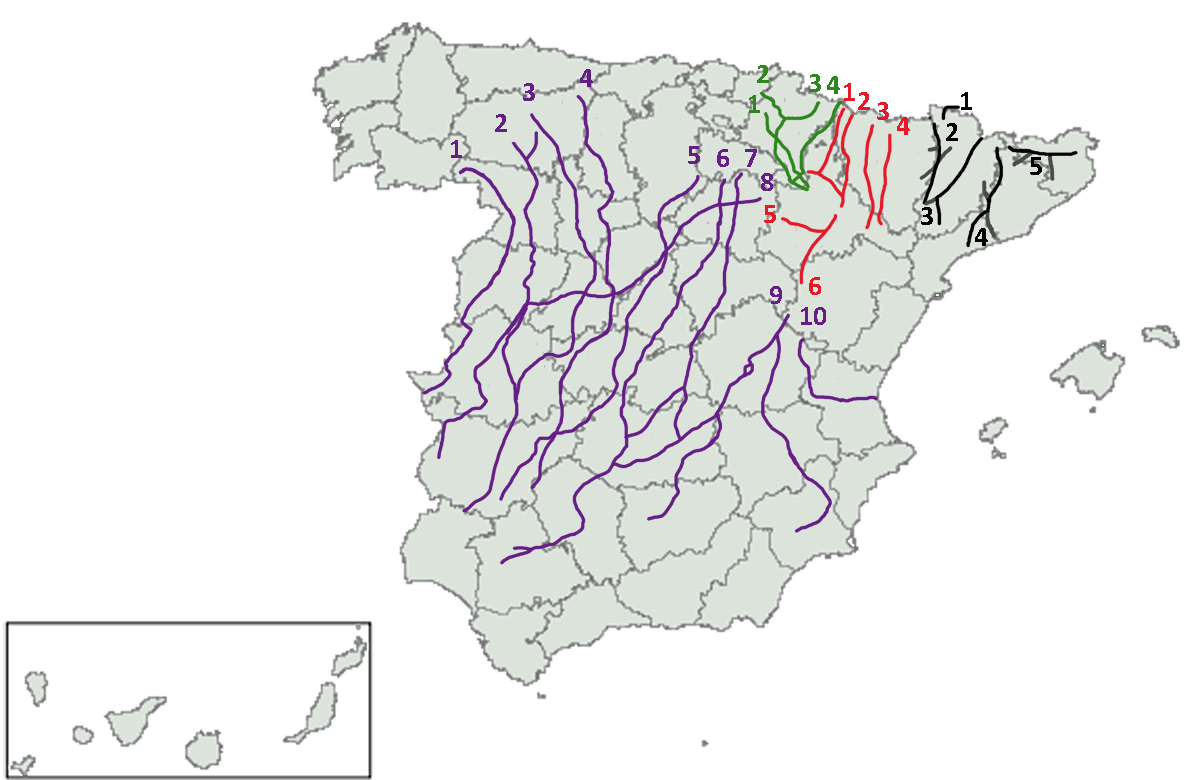

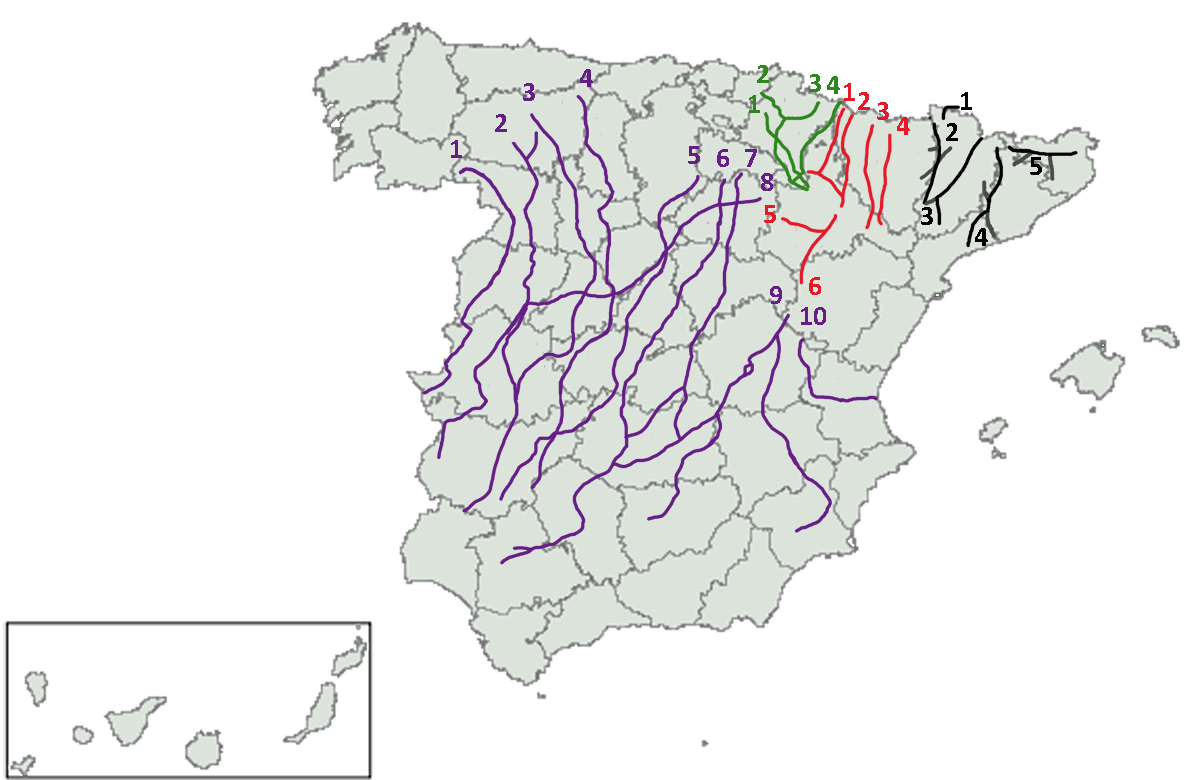

Transhumance is historically widespread throughout much of Spain, particularly in the regions of Castile, Leon and Extremadura, where nomadic cattle and sheep herders travel long distances in search of greener pastures in summer and warmer climatic conditions in winter. Spanish transhumance is the origin of numerous related cultures in the Americas such as the cowboys of the United States and the Gauchos of Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil.

A network of droveways, or , crosses the whole peninsula, running mostly south-west to north-east. They have been charted since ancient times, and classified according to width; the standard is between wide, with some (meaning ''royal droveways'') being wide at certain points. The land within the droveways is publicly owned and protected by law.

In some high valleys of the

Transhumance is historically widespread throughout much of Spain, particularly in the regions of Castile, Leon and Extremadura, where nomadic cattle and sheep herders travel long distances in search of greener pastures in summer and warmer climatic conditions in winter. Spanish transhumance is the origin of numerous related cultures in the Americas such as the cowboys of the United States and the Gauchos of Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil.

A network of droveways, or , crosses the whole peninsula, running mostly south-west to north-east. They have been charted since ancient times, and classified according to width; the standard is between wide, with some (meaning ''royal droveways'') being wide at certain points. The land within the droveways is publicly owned and protected by law.

In some high valleys of the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

and the Cantabrian Mountains

The Cantabrian Mountains or Cantabrian Range () are one of the main systems of mountain ranges in Spain.

They stretch for over 300 km (180 miles) across northern Spain, from the western limit of the Pyrenees to the Galician Massif ...

, transhumant herding has been the main, or only, economic activity. Regulated passes and pasturage have been distributed among different valleys and communities according to the seasonal range of use and community jurisdiction. Unique social groups associated with the transhumant lifestyle are sometimes identified as a remnant of an older ethnic culture now surviving in isolated minorities, such as the " Pasiegos" in Cantabria

Cantabria (, ; ) is an autonomous community and Provinces of Spain, province in northern Spain with Santander, Cantabria, Santander as its capital city. It is called a , a Nationalities and regions of Spain, historic community, in its current ...

, " Agotes" in Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

, and "Vaqueiros de alzada

The Vaqueiros de Alzada ( Asturian: Vaqueiros d'Alzada, "nomadic cowherds" in Asturian language, from their word for cow, cognate of Spanish ) are a northern Spanish nomadic people in the mountains of Asturias and León, who traditionally practi ...

" in Asturias

Asturias (; ; ) officially the Principality of Asturias, is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in northwest Spain.

It is coextensive with the provinces of Spain, province of Asturias and contains some of the territory t ...

and León.

The Pyrenees

Transhumance in the

Transhumance in the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

involves relocation of livestock (cows, sheep, horses) to high mountains during the summer months, because farms in the lowland are too small to support a larger herd all year round. The mountain period starts in late May or early June, and ends in early October. Until the 1970s, transhumance was used mainly for dairy cows, and cheese-making was an important activity in the summer months. In some regions, nearly all members of a family decamped to higher mountains with their cows, living in rudimentary stone cabins for the summer grazing season. That system, which evolved during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, lasted into the 20th century. It declined and broke down under pressure from industrialisation

Industrialisation ( UK) or industrialization ( US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive reorganisation of an economy for th ...

, as people left the countryside for jobs in cities. However, the importance of transhumance continues to be recognised through its celebration in popular festivals.

The Mont Perdu / Monte Perdido region of the Pyrenees has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

by virtue of its association with the transhumance system of agriculture.

Scandinavian Peninsula

In Scandinavia, transhumance is practised to a certain extent; however, livestock are transported between pastures by motorised vehicles, changing the character of the movement. The

In Scandinavia, transhumance is practised to a certain extent; however, livestock are transported between pastures by motorised vehicles, changing the character of the movement. The Sami people

Acronyms

* SAMI, ''Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange'', a closed-captioning format developed by Microsoft

* Saudi Arabian Military Industries, a government-owned defence company

* South African Malaria Initiative, a virtual expertise ...

practice transhumance with reindeer

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, taiga, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only re ...

by a different system than is described immediately below.

The common mountain or forest pasture used for transhumance in summer is called or / . The same term is used for a related mountain cabin, which was used as a summer residence. In summer (usually late June), livestock is moved to a mountain farm, often quite distant from a home farm, to preserve meadow

A meadow ( ) is an open habitat or field, vegetated by grasses, herbs, and other non- woody plants. Trees or shrubs may sparsely populate meadows, as long as they maintain an open character. Meadows can occur naturally under favourable con ...

s in valleys for producing hay

Hay is grass, legumes, or other herbaceous plants that have been cut and dried to be stored for use as animal fodder, either for large grazing animals raised as livestock, such as cattle, horses, goats, and sheep, or for smaller domesticate ...

. Livestock is typically tended during the summer by girls and younger women, who also milk and make cheese. Bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not Castration, castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e. cows proper), bulls have long been an important symbol cattle in r ...

s usually remain at the home farm. As autumn approaches and grazing is exhausted, livestock is returned to the farm.

In Sweden, this system was predominantly used in Värmland

Värmland () is a ''Provinces of Sweden, landskap'' (historical province) in west-central Sweden. It borders Västergötland, Dalsland, Dalarna, Västmanland, and Närke, and is bounded by Norway in the west.

Name

Several Latinized version ...

, Dalarna

Dalarna (; ), also referred to by the English exonyms Dalecarlia and the Dales, is a (historical province) in central Sweden.

Dalarna adjoins Härjedalen, Hälsingland, Gästrikland, Västmanland and Värmland. It is also bordered by Nor ...

, Härjedalen

Härjedalen () is a historical province (''landskap'') in the centre of Sweden. It borders the Norwegian county of Trøndelag, as well as the provinces of Dalarna, Hälsingland, Medelpad and Jämtland. The province originally belonged to Norway, ...

, Jämtland

Jämtland () is a historical provinces of Sweden, province () in the centre of Sweden in northern Europe. It borders Härjedalen and Medelpad to the south, Ångermanland to the east, Lapland, Sweden, Lapland to the north and Trøndelag and Norw ...

, Hälsingland

Hälsingland (), sometimes referred to by the Latin name Helsingia, is a historical Provinces of Sweden, province or ''landskap'' in central Sweden. It borders Gästrikland, Dalarna, Härjedalen, Medelpad and the Gulf of Bothnia. It is part of ...

, Medelpad

Medelpad ( or ) is a historical province or ''landskap'' in the north of Sweden. It borders Hälsingland, Härjedalen, Jämtland, Ångermanland and the Gulf of Bothnia.

The province is a part of Norrland and as such considered to be Northe ...

and Ångermanland

Ångermanland ( or ) is a historical province (''landskap'') in the northern part of Sweden. It is bordered (clockwise from the north) by Swedish Lapland, Västerbotten, the Gulf of Bothnia, Medelpad and Jämtland.

The name is derived from the ...

.

The practice was common throughout most of Norway, due to its highly mountainous nature and limited areas of lowland for cultivation.

While previously many farms had their own seters, it is more usual for several farmers to share a modernised common seter (). Most of the old seters have been left to decay or are used as recreational cabins.

The name for the common mountain pasture in most Scandinavian languages derives from the Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

term . In Norwegian, the term is or ; in Swedish, . The place name appears in Sweden in several forms as and , and as a suffix: -, -, - and -. Those names appear extensively across Sweden with a centre in the Mälaren

Mälaren ( , , or ), historically referred to as Lake Malar in English, is the third-largest freshwater lake in Sweden (after Vänern and Vättern). Its area is and its greatest depth is 64 m (210 ft). Mälaren spans from east to west. The l ...

basin and in Östergötland

Östergötland (; English exonym: East Gothland) is one of the traditional provinces of Sweden (''landskap'' in Swedish) in the south of Sweden. It borders Småland, Västergötland, Närke, Södermanland and the Baltic Sea. In older English li ...

. The surname "Satter" is derived from these words.

In the heartland of the Swedish transhumance region, the most commonly used term is or (the word is also used for small storage houses and the like; it has evolved in English as ''booth''); in modern Standard Swedish, .

The oldest mention of in Norway is in ''Heimskringla

() is the best known of the Old Norse kings' sagas. It was written in Old Norse in Iceland. While authorship of ''Heimskringla'' is nowhere attributed, some scholars assume it is written by the Icelandic poet and historian Snorri Sturluson (117 ...

'', the saga of Olaf II of Norway

Saint Olaf ( – 29 July 1030), also called Olaf the Holy, Olaf II, Olaf Haraldsson, and Olaf the Stout or "Large", was List of Norwegian monarchs, King of Norway from 1015 to 1028. Son of Harald Grenske, a petty king in Vestfold, Norway, he w ...

's travel through Valldal

Sylte or Valldal is a village in Fjord Municipality in Møre og Romsdal county, Norway. The village is situated at the southern end of the Valldalen valley along the shore of the Norddalsfjorden near the mouth of the Valldøla river, just west ...

to Lesja

Lesja is a municipality in Innlandet county, Norway. It is located in the traditional district of Gudbrandsdal. The administrative centre of the municipality is the village of Lesja. Other villages in the municipality include Bjorli, Lesjas ...

.

The practice of summer farming at fäbod and seter in Sweden and Norway has been included in UNESCO's Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage since 2024.

Caucasus and northern Anatolia

In the heavily forestedCaucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

and Pontic mountain ranges, various peoples still practice transhumance to varying degrees. During the relatively short summer, wind from the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

brings moist air up the steep valleys, which supports fertile grasslands at altitudes up to , and a rich tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

at altitudes up to . Traditionally, villages were divided into two, three or even four distinct settlements (one for each season) at different heights of a mountain slope. Much of this rural life came to an end during the first half of the 20th century, as the Kemalist

Kemalism (, also archaically ''Kamâlizm'') or Atatürkism () is a political ideology based on the ideas of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder and first president of the Turkey, Republic of Turkey.Eric J. Zurcher, Turkey: A Modern History. Ne ...

and later Soviet governments tried to modernise the societies and stress urban development, rather than maintaining rural traditions.

In the second half of the 20th century, migration for work from the Pontic mountains to cities in Turkey and western Europe, and from the northern Caucasus to Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, dramatically reduced the number of people living in transhumance. It is estimated, however, that tens of thousands of rural people still practice these traditions in villages on the northern and southwestern slopes of the Caucasus, in the lesser Caucasus in Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

, and in the Turkish Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

region.

Some communities continue to play out ancient migration patterns. For example, the Pontic Greeks visit the area and the monastery Sumela in the summer. Turks from cities in Europe have built a summer retreat on the former ''yayla'' grazing land.

Transhumance related to sheep farming is still practised in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

. The shepherds with their flocks have to cross the high Abano Pass from the mountains of Tusheti

Tusheti ( ka, თუშეთი, tr; Bats: თუშითა, romanized: tushita) is a historic region in northeast Georgia. A mountainous area, it is home to the Tusheti National Park. By the conventional definition of the Europe-Asia boundar ...

to the plains of Kakheti

Kakheti (; ) is a region of Georgia. Telavi is its administrative center. The region comprises eight administrative districts: Telavi, Gurjaani, Qvareli, Sagarejo, Dedoplistsqaro, Signagi, Lagodekhi and Akhmeta.

Kakhetians speak the ...

. Up until the dissolution of Soviet Union they intensively used the Kizlyar

Kizlyar (; ; , ''Qızlar'') is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town in the Republic of Dagestan, Russia, located on the border with the Chechen Republic in the river delta, delta of the Terek River northwest of Makhachkala, the cap ...

plains of Northern Dagestan

Dagestan ( ; ; ), officially the Republic of Dagestan, is a republic of Russia situated in the North Caucasus of Eastern Europe, along the Caspian Sea. It is located north of the Greater Caucasus, and is a part of the North Caucasian Fede ...

for the same purpose.

Asia

Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, the central Afghan highlands surround theKoh-i-Baba

The Baba Mountain range ( Bâbâ Ǧar; Kōh-i Bābā; or Kūh-e Bābā; ''Kōh'' or ''Kūh'' meaning ′mountain′, ''Bābā'' meaning ′father′) is the western extension of the Hindu Kush, and the origin of Afghanistan's Kabul, Arghandab ...

and continue eastward into the Hindu Kush

The Hindu Kush is an mountain range in Central Asia, Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas. It stretches from central and eastern Afghanistan into northwestern Pakistan and far southeastern Tajikistan. The range forms the wester ...

range. Summers are short and cool while winters are very cold. These highlands have mountain pastures during summer (), watered by many small streams and rivers. Winter pastures in the neighboring warm lowlands () make the region ideal for seasonal transhumance. The Afghan Highlands contain about of summer pasture, which is used by both settled communities and nomadic pastoralists like the Pashtun

Pashtuns (, , ; ;), also known as Pakhtuns, or Pathans, are an Iranic ethnic group primarily residing in southern and eastern Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan. They were historically also referred to as Afghans until 1964 after the ...

Kuchis

Kochis also spelt as Kuchis (Pashto Language, Pashto: کوچۍ Kuchis) are pastoral nomads belonging primarily to the Ghilji Pashtuns. It is a social rather than ethnic grouping, although they have some of the characteristics of a distinct et ...

. Major pastures in the region include the Nawur pasture

Dasht-e Nāwar () is an archaeological site in Ghazni province in Afghanistan.

It's situated at the northern end of the lake, on and around Tepe Qādagak, c. 60 km west of Ghazni. A brackish lake measuring c. 60 x 15 km. On the "beache ...

in northern Ghazni Province

Ghazni (; ) is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan, located in southeastern Afghanistan. The province contains 19 Districts of Afghanistan, districts, encompassing over a thousand villages and roughly 1.3 million people, making it the 5th most ...

(whose area is about 600 km2 at elevation of up to 3,350 m), and the Shewa pasture and the Little Pamir in eastern Badakhshan Province

Badakhshan Province (Dari: بدخشان) is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan, located in the northeastern part of the country. It is bordered by Tajikistan's Gorno-Badakhshan in the north and the Pakistani regions of Lower and Upper C ...

. The Little Pamir pasture, whose elevation is above , is used by the Afghan Kyrgyz to raise livestock.

In Nuristan

Nuristan, also spelled as Nurestan or Nooristan (Pashto: ; Katë: ), is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan, located in the eastern part of the country. It is divided into seven districts and is Afghanistan's least populous province, with a ...

, the inhabitants live in permanent villages surrounded by arable fields on irrigated terraces. Most of the livestock are goats. They are taken up to a succession of summer pastures each spring by herdsmen while most of the villagers remain behind to irrigate the terraced fields and raise millet, maize, and wheat; work mostly done by the women. In the autumn after the grain and fruit harvest, livestock are brought back to spend the winter stall-fed in stables.

India

Jammu and Kashmir in India has the world's highest transhumant population as per a survey conducted by a team led by Dr Shahid Iqbal Choudhary, IAS, Secretary to the Government of Jammu and Kashmir, Tribal Affairs Department. The 1st Survey of Transhumance in 2021 captured details of 6,12,000 members of ethnic tribal communities viz Gujjars, Bakkerwals, Gaddis and Sippis. The survey was carried out for development and welfare planning for these communities notified as Scheduled tribes under theConstitution of India

The Constitution of India is the supreme law of India, legal document of India, and the longest written national constitution in the world. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures ...

. Subsequent to the survey a number of flagship initiatives were launched by the Government for their welfare and development especially in sectors like healthcare, veterinary services, education, livelihood and transportation support for migration. Transhumance in Jammu and Kashmir is mostly vertical while some families in the plains of the Jammu, Samba and Kathua districts also practice lateral or horizontal transhumance. More than 85% of the migratory transhumant population moves within the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir while the remaining 15% undertakes inter-state movement to the neighbouring Punjab State and to the Ladakh Union territory. Gujjars – a migratory tribe – also sparsely inhabit several areas in parts of Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. The Gujjar-Bakkerwal tribe represents the highest transhumant population in the world and accounts for nearly 98% of the transhumant population in Jammu and Kashmir. The Bhotiya

Bhotiya or Bhot (, ) is an Indian and Nepali exonym lumping together various ethnic groups speaking Tibetic languages, as well as some groups speaking other Tibeto-Burman languages living in the Transhimalayan region that divides India from T ...

communities of Uttarakhand

Uttarakhand (, ), also known as Uttaranchal ( ; List of renamed places in India, the official name until 2007), is a States and union territories of India, state in North India, northern India. The state is bordered by Himachal Pradesh to the n ...

historically practiced transhumance. They would spend the winter months at low altitude settlements in the Himalayan foothills, gathering resources to trade in Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

over the summer. In the summer, they would move up to high-altitude settlements along various river valleys. Traditionally involved in wool cleaning, spinning, and weaving items like shawls and carpets, these villagers now rely on transhumant herders for raw materials as they no longer keep livestock. Some people would remain at these settlements to cultivate farms; some would head to trade marts, crossing high mountain passes into western Tibet, while some others would practice nomadic pastoralism. This historic way of life came to an abrupt halt due to the closure of the Sino-Indian border following the Sino-Indian War

The Sino–Indian War, also known as the China–India War or the Indo–China War, was an armed conflict between China and India that took place from October to November 1962. It was a military escalation of the Sino–Indian border dispu ...

of 1962. In the decades following this war, transhumance as a way of life rapidly declined among the Bhotiya people.

The pastoral Gujars of northern India rely on state forests for pasture but face increasing restrictions from the government. This has led to significant impoverishment as they lose traditional grazing land and fall into debt. Transhumant pastoralism, guided by traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), helps the Kinnaura community in Himachal Pradesh adapt to harsh high-altitude conditions. However, this age-old practice is under threat due to socioeconomic, policy, and environmental changes, risking the erosion of pastoralism-related TEK.

Iran

The Bakhtiari tribe of Iran still practised this way of life in the mid-20th century. All along theZagros Mountains

The Zagros Mountains are a mountain range in Iran, northern Iraq, and southeastern Turkey. The mountain range has a total length of . The Zagros range begins in northwestern Iran and roughly follows Iran's western border while covering much of s ...

from Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan, officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is a Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental and landlocked country at the boundary of West Asia and Eastern Europe. It is a part of the South Caucasus region and is bounded by ...

to the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea () is a region of sea in the northern Indian Ocean, bounded on the west by the Arabian Peninsula, Gulf of Aden and Guardafui Channel, on the northwest by Gulf of Oman and Iran, on the north by Pakistan, on the east by India, and ...

, pastoral tribes move back and forth with their herds annually according to the seasons, between their permanent homes in the valley and one in the foothills.

The Qashqai (Kashkai) are a Turkic tribe of southern Iran, who in the mid-20th century still practised transhumance. The tribe was said to have settled in ancient times in the province of Fars, near the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

, and by the mid-20th century lived beyond the Makran

Makran (), also mentioned in some sources as ''Mecran'' and ''Mokrān'', is the southern coastal region of Balochistan. It is a semi-desert coastal strip in the Balochistan province in Pakistan and in Iran, along the coast of the Gulf of Oman. I ...

mountains. In their yearly migrations for fresh pastures, the Kashkai drove their livestock from south to north, where they lived in summer quarters, known as , in the high mountains from April to October. They traditionally grazed their flocks on the slopes of the Kuh-e-Dinar, a group of mountains from , part of the Zagros chain.

In autumn the Kashkai broke camp, leaving the highlands to winter in warmer regions near Firuzabad, Kazerun, Jerrè, Farashband, on the banks of the Mond River

The Mond River (), also known in English as the Mand River, runs through Fars province and Bushehr province in south-western Iran, flowing to the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, me ...

. Their winter quarters were known as . The migration was organised and controlled by the Kashkai Chief. The tribes avoided villages and towns, such as Shiraz and Isfahan, because their large flocks, numbering seven million head, could cause serious damage.

In the 1950s, the Kashkai tribes were estimated to number 400,000 people in total. There have been many social changes since that time.

Lebanon

Examples of fixed transhumance are found in theNorth Governorate

North Governorate (, ') is one of the governorates of Lebanon and one of the two governorates of North Lebanon. Its capital is Tripoli, Lebanon, Tripoli. Ramzi Nohra has been its governor since May 2, 2014. The population of North Governorate is ...

of Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

. Towns and villages located in the Qadisha valley are at an average altitude of . Some settlements, like Ehden

Ehden (, Syriac language, Syriac-Aramaic:ܐܗܕ ܢ) is a mountainous city in the heart of the northern mountains of Lebanon and on the southwestern slopes of Mount Makmal in the Mount Lebanon, Mount Lebanon Range. Its residents are the people of Z ...

and Kfarsghab, are used during summer periods from the beginning of June until mid-October. Inhabitants move in October to coastal towns situated at an average of above sea level. The transhumance is motivated by agricultural activities (historically by the mulberry

''Morus'', a genus of flowering plants in the family Moraceae, consists of 19 species of deciduous trees commonly known as mulberries, growing wild and under cultivation in many temperate world regions. Generally, the genus has 64 subordinat ...

silkworm

''Bombyx mori'', commonly known as the domestic silk moth, is a moth species belonging to the family Bombycidae. It is the closest relative of '' Bombyx mandarina'', the wild silk moth. Silkworms are the larvae of silk moths. The silkworm is of ...

culture). The main crops in the coastal towns are olive

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'' ("European olive"), is a species of Subtropics, subtropical evergreen tree in the Family (biology), family Oleaceae. Originating in Anatolia, Asia Minor, it is abundant throughout the Mediterranean ...

, grape

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non- climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of grapes began approximately 8,0 ...

and citrus

''Citrus'' is a genus of flowering trees and shrubs in the family Rutaceae. Plants in the genus produce citrus fruits, including important crops such as oranges, mandarins, lemons, grapefruits, pomelos, and limes.

''Citrus'' is nativ ...

. For the mountain towns, the crops are summer fruits, mainly apple

An apple is a round, edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus'' spp.). Fruit trees of the orchard or domestic apple (''Malus domestica''), the most widely grown in the genus, are agriculture, cultivated worldwide. The tree originated ...

s and pear

Pears are fruits produced and consumed around the world, growing on a tree and harvested in late summer into mid-autumn. The pear tree and shrub are a species of genus ''Pyrus'' , in the Family (biology), family Rosaceae, bearing the Pome, po ...

s. Other examples of transhumance exist in Lebanon.

Kyrgyzstan

InKyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan, officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia lying in the Tian Shan and Pamir Mountains, Pamir mountain ranges. Bishkek is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Kyrgyzstan, largest city. Kyrgyz ...

, transhumance practices, which never ceased during the Soviet period

The history of the Soviet Union (USSR) (1922–91) began with the ideals of the Russian Bolshevik Revolution and ended in dissolution amidst economic collapse and political disintegration. Established in 1922 following the Russian Civil War, ...

, have undergone a resurgence in the difficult economic times following independence in 1991. Transhumance is integral to Kyrgyz national culture. The people use a wool felt tent, known as the yurt

A yurt (from the Turkic languages) or ger (Mongolian language, Mongolian) is a portable, round tent covered and Thermal insulation, insulated with Hide (skin), skins or felt and traditionally used as a dwelling by several distinct Nomad, nomad ...

or , while living on these summer pastures. It is symbolised on their national flag

A national flag is a flag that represents and national symbol, symbolizes a given nation. It is Fly (flag), flown by the government of that nation, but can also be flown by its citizens. A national flag is typically designed with specific meanin ...

. Those shepherds prize a fermented drink

This is a list of fermented foods, which are foods produced or preserved by the action of microorganisms. In this context, Fermentation in food processing, fermentation typically refers to the fermentation of sugar to ethanol, alcohol using yeas ...

made from mare's milk, known as . A tool used in its production is the namesake for Bishkek

Bishkek, formerly known as Pishpek (until 1926), and then Frunze (1926–1991), is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Kyrgyzstan. Bishkek is also the administrative centre of the Chüy Region. Bishkek is situated near the Kazakhstan ...

, the country's capital city.

South and East Asia

Transhumance practices are found in temperate areas, above ≈ in theHimalaya

The Himalayas, or Himalaya ( ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the Earth's highest peaks, including the highest, Mount Everest. More than 100 pea ...

–Hindu Kush

The Hindu Kush is an mountain range in Central Asia, Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas. It stretches from central and eastern Afghanistan into northwestern Pakistan and far southeastern Tajikistan. The range forms the wester ...

area (referred to below as Himalaya); and the cold semi-arid zone north of the Himalaya, through the Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or Qingzang Plateau, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central Asia, Central, South Asia, South, and East Asia. Geographically, it is located to the north of H ...

and northern China to the Eurasian Steppe

The Eurasian Steppe, also called the Great Steppe or The Steppes, is the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands biome. It stretches through Manchuria, Mongolia, Xinjiang, Kazakhstan, Siberia, Europea ...

.

Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

, China, Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

, Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan, officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia lying in the Tian Shan and Pamir Mountains, Pamir mountain ranges. Bishkek is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Kyrgyzstan, largest city. Kyrgyz ...

, Bhutan

Bhutan, officially the Kingdom of Bhutan, is a landlocked country in South Asia, in the Eastern Himalayas between China to the north and northwest and India to the south and southeast. With a population of over 727,145 and a territory of , ...

, India, Nepal

Nepal, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mainly situated in the Himalayas, but also includes parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China Ch ...

and Pakistan all have vestigial transhumance cultures. The Bamar people

The Bamar people ( Burmese: ဗမာလူမျိုး, ''ba. ma lu myui:'' ) (formerly known as Burmese people or Burmans) are a Sino-Tibetan-speaking ethnic group native to Myanmar (formerly known as Burma). With an estimated population ...

of Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

were transhumance prior to their arrival to the region. In Mongolia, transhumance is used to avoid livestock losses during harsh winters, known as ''zud

A zud, dzud (), dzhut, zhut, djut, or jut (, , ) is a periodic disaster in steppe, semi-desert and desert regions in Mongolia and Central Asia (including Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan) in which large numbers of livestock die, primarily due t ...

s''. For regions of the Himalaya, transhumance still provides mainstay for several near-subsistence economiesfor example, that of Zanskar

Zanskar, Zahar (locally) or Zangskar, is the southwestern region of Kargil district in the Indian union territory of Ladakh. The administrative centre of Zanskar is Padum. Zanskar, together with the rest of Ladakh, was briefly a part of the kin ...

in northwest India, Van Gujjars and Bakarwals of Jammu and Kashmir in India, Kham Magar

The Kham Magars (खाम मगर), also known in scholarship as the Northern Magars, are a (Tibeto-Burman languages, Tibeto-Burman language) Magar Kham language or Kham Kura speaking indigenous ethnic tribal community native to Nepal. In g ...

in western Nepal and Gaddis of Bharmaur region of Himachal Pradesh. In some cases, the distances travelled by the people with their livestock may be great enough to qualify as nomadic pastoralism

Nomadic pastoralism, also known as nomadic herding, is a form of pastoralism in which livestock are herded in order to seek for fresh pastures on which to graze. True nomads follow an irregular pattern of movement, in contrast with transhumance ...

.

Oceania

Australia

In Australia, which has a largestation

Station may refer to:

Agriculture

* Station (Australian agriculture), a large Australian landholding used for livestock production

* Station (New Zealand agriculture), a large New Zealand farm used for grazing by sheep and cattle

** Cattle statio ...

(i.e., ranch) culture, stockmen provide the labour to move the herds to seasonal pastures.

Transhumant grazing is an important aspect of the cultural heritage of the Australian Alps, an area of which has been included on the Australian National Heritage List. Colonists started using this region for summer grazing in the 1830s, when pasture lower down was poor. The practice continued during the 19th and 20th centuries, helping make pastoralism

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as "livestock") are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands (pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The anim ...

in Australia viable. Transhumant grazing created a distinctive way of life that is an important part of Australia's pioneering history and culture. There are features in the area that are reminders of transhumant grazing, including abandoned stockman's huts, stock yards and stock routes.

Africa

North Africa

TheBerber people

Berbers, or the Berber peoples, also known as Amazigh or Imazighen, are a diverse grouping of distinct ethnic groups indigenous to North Africa who predate the arrival of Arabs in the Maghreb. Their main connections are identified by their u ...

of North Africa were traditionally farmers, living in mountains relatively close to the Mediterranean coast, or oasis dwellers. However, the Tuareg

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym, depending on variety: ''Imuhaɣ'', ''Imušaɣ'', ''Imašeɣăn'' or ''Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group, traditionally nomadic pastoralists, who principally inhabit th ...

and Zenaga of the southern Sahara practice nomadic transhumance. Other groups, such as the Chaouis, practised fixed transhumance.

Horn of Africa

In rural areas, the Somali and Afar of Northeast Africa also traditionally practise nomadic transhumance. Their pastoralism is centred oncamel

A camel (from and () from Ancient Semitic: ''gāmāl'') is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. Camels have long been domesticated and, as livestock, they provid ...

husbandry, with additional sheep and goat herding.

The classic, "fixed" transhumance is practiced in the Ethiopian Highlands

The Ethiopian Highlands (also called the Abyssinian Highlands) is a rugged mass of mountains in Ethiopia in Northeast Africa. It forms the largest continuous area of its elevation in the continent, with little of its surface falling below , whil ...

. During the cropping season the lands around the villages are not accessible for grazing. For instance, farmers with livestock in Dogu'a Tembien organise annual transhumance, particularly towards remote and vast grazing grounds, deep in valleys (where the grass grows early due to temperature) or mountain tops. Livestock will stay there overnight (transhumance) with children and a few adults keeping them.

For instance, the cattle of Addi Geza'iti () are brought every rainy season to the gorge of River Tsaliet () that holds dense vegetation. The cattle keepers establish enclosures for the cattle and places for them to sleep, often in rock shelters. The cattle stay there until harvesting time, when they are needed for threshing, and when the stubble becomes available for grazing. Many cattle of Haddinnet

Haddinnet, also transliterated as Hadnet, is a ''tabia'' or municipality in the Degua Tembien, Dogu'a Tembien district of the Tigray Region of Ethiopia. The ''tabia'' centre is in Addi Idaga village, located approximately 6.5 km to the north ...

and also Ayninbirkekin

Ayninbirkekin is a ''tabia'' or municipality in the Degua Tembien, Dogu'a Tembien district of the Tigray Region of Ethiopia. Literal meaning of Ayninbirkekin in Tigrinya is "We will not bend". The ''tabia'' centre is in Halah village, located app ...

in Dogu'a Tembien are brought to the foot of the escarpment at Ab'aro

The Ab’aro is a river of the Nile basin. Rising in the mountains of Degua Tembien , Dogu’a Tembien in northern Ethiopia, it flows northwestward to empty into the Wari River, Weri’i, which is a tributary of Tekezé River.

Characteristics ...

. Cattle stay on there on wide rangelands. Some cattle keepers move far down to open woodland and establish their camp in large caves in sandstone.

East Africa

The Pokot community are semi-nomadic pastoralists who are predominantly found in northwesternKenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

and Amudat district of Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

. The community practices nomadic transhumance, with seasonal movement occurring between grasslands of Kenya (North Pokot sub-county) and Uganda (Amudat, Nakapiripirit and Moroto districts) (George Magak Oguna, 2014).

The Maasai Maasai may refer to:

*Maasai people

*Maasai language

*Maasai mythology

* MAASAI (band)

See also

* Masai (disambiguation)

Masai may refer to:

*Masai, Johor, a town in Malaysia

* Masai Plateau, a plateau in Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India

*Maasai peopl ...

are semi-nomadic people located primarily in Kenya