Second National Bank on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized

Opposition to a new bank emanated from two interests.

Opposition to a new bank emanated from two interests.

By the time of Jackson's inauguration in 1829, the bank appeared to be on solid footing. The Supreme Court had affirmed its constitutionality in ''

By the time of Jackson's inauguration in 1829, the bank appeared to be on solid footing. The Supreme Court had affirmed its constitutionality in ''

* William Jones, January 7, 1817 – January 25, 1819

* James Fisher, January 25, 1819 – March 6, 1819

*

* William Jones, January 7, 1817 – January 25, 1819

* James Fisher, January 25, 1819 – March 6, 1819

*

online review

* * * * * * Feller, Daniel. "The Bank War", in Julian E. Zelizer, ed. ''The American Congress'' (2004), pp 93–111. * * * * * * * * * * * Kahan, Paul. ''The Bank War: Andrew Jackson, Nicholas Biddle, and the Fight for American Finance'' (Yardley: Westholme, 2016. xii, 187 pp. * *

online review

* * * * * * * * * Ratner, Sidney, James H. Soltow, and Richard Sylla. ''The Evolution of the American Economy: Growth, Welfare, and Decision Making''. (1993) * * * * * * Schweikart, Larry. ''Banking in the American South from the Age of Jackson to Reconstruction'' (1987) * Taylor; George Rogers, ed. ''Jackson Versus Biddle: The Struggle over the Second Bank of the United States'' (1949). * Temin, Peter. ''The Jacksonian Economy'' (1969) * * * *

Second Bank

– official site at Independence Hall National Historical Park

Documents produced by the Second Bank of the United States

on

Andrew Jackson on the Web : Bank of the United States

* {{Authority control 14th United States Congress 1816 establishments in Massachusetts 1820s architecture in the United States American companies disestablished in 1841 Art museums and galleries in Philadelphia Bank buildings in Philadelphia Bank buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Philadelphia Banks based in Philadelphia Banks disestablished in 1841 Banks established in 1816 Buildings and structures in Independence National Historical Park Chestnut Street (Philadelphia) Commercial buildings completed in 1824 Defunct banks of the United States Defunct companies based in Pennsylvania Era of Good Feelings Financial history of the United States

Hamiltonian

Hamiltonian may refer to:

* Hamiltonian mechanics, a function that represents the total energy of a system

* Hamiltonian (quantum mechanics), an operator corresponding to the total energy of that system

** Dyall Hamiltonian, a modified Hamiltonian ...

national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

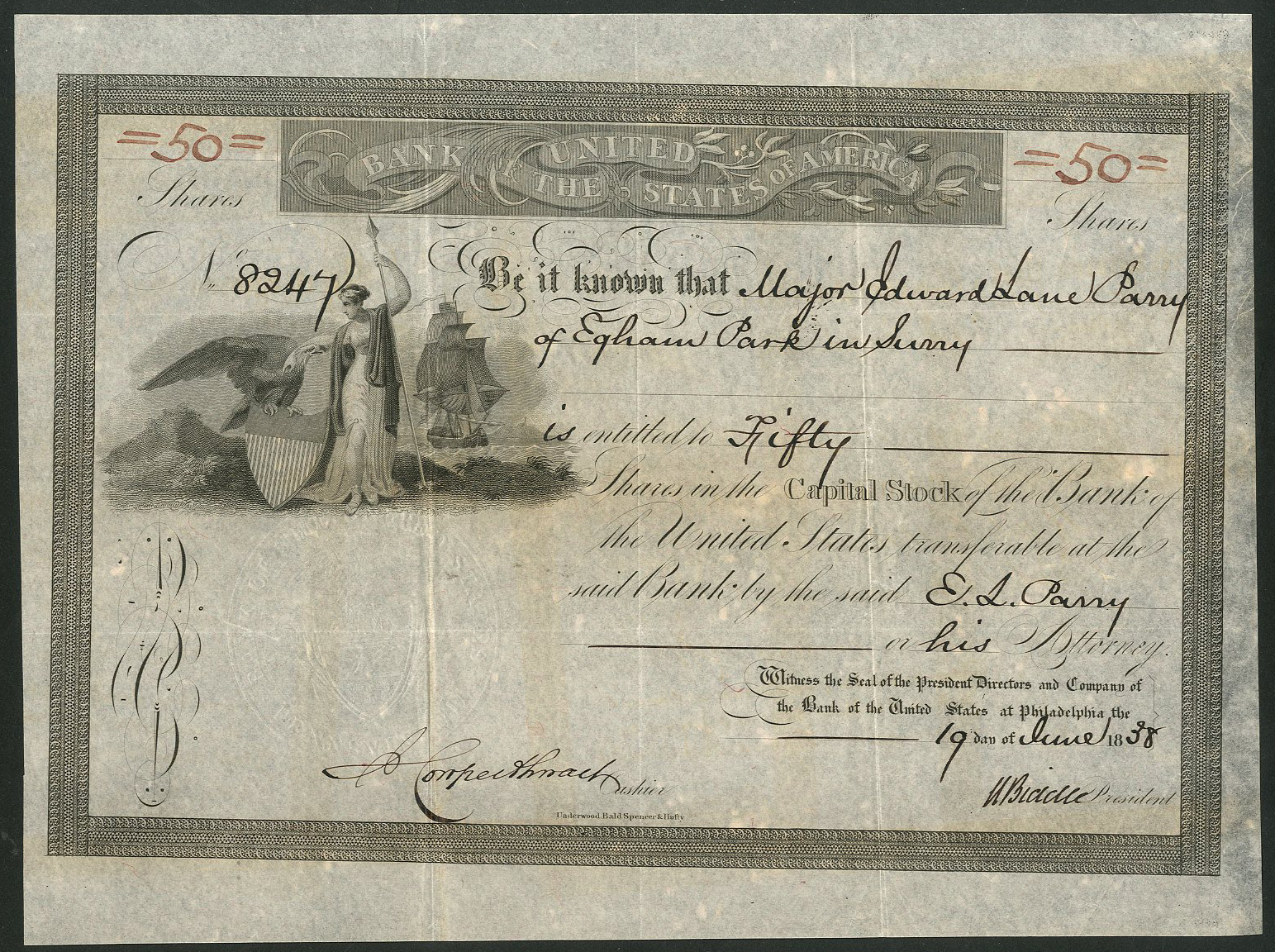

, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The bank's formal name, according to section 9 of its charter as passed by Congress, was "The President, Directors, and Company, of the Bank of the United States". While other banks in the US were chartered by and only allowed to have branches in a single state, it was authorized to have branches in multiple states and lend money to the US government.

A private corporation

A privately held company (or simply a private company) is a company whose Stock, shares and related rights or obligations are not offered for public subscription or publicly negotiated in their respective listed markets. Instead, the Private equi ...

with public duties

Public duties are performed by military personnel, and usually have a ceremonial or historic significance rather than an overtly operational role.

Armenia

Since September 2018, the Honour Guard Battalion (Armenia), Honour Guard Battalion of the Mi ...

, the bank handled all fiscal transactions for the U.S. government, and was accountable to Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

and the U.S. Treasury

The Department of the Treasury (USDT) is the Treasury, national treasury and finance department of the federal government of the United States. It is one of 15 current United States federal executive departments, U.S. government departments.

...

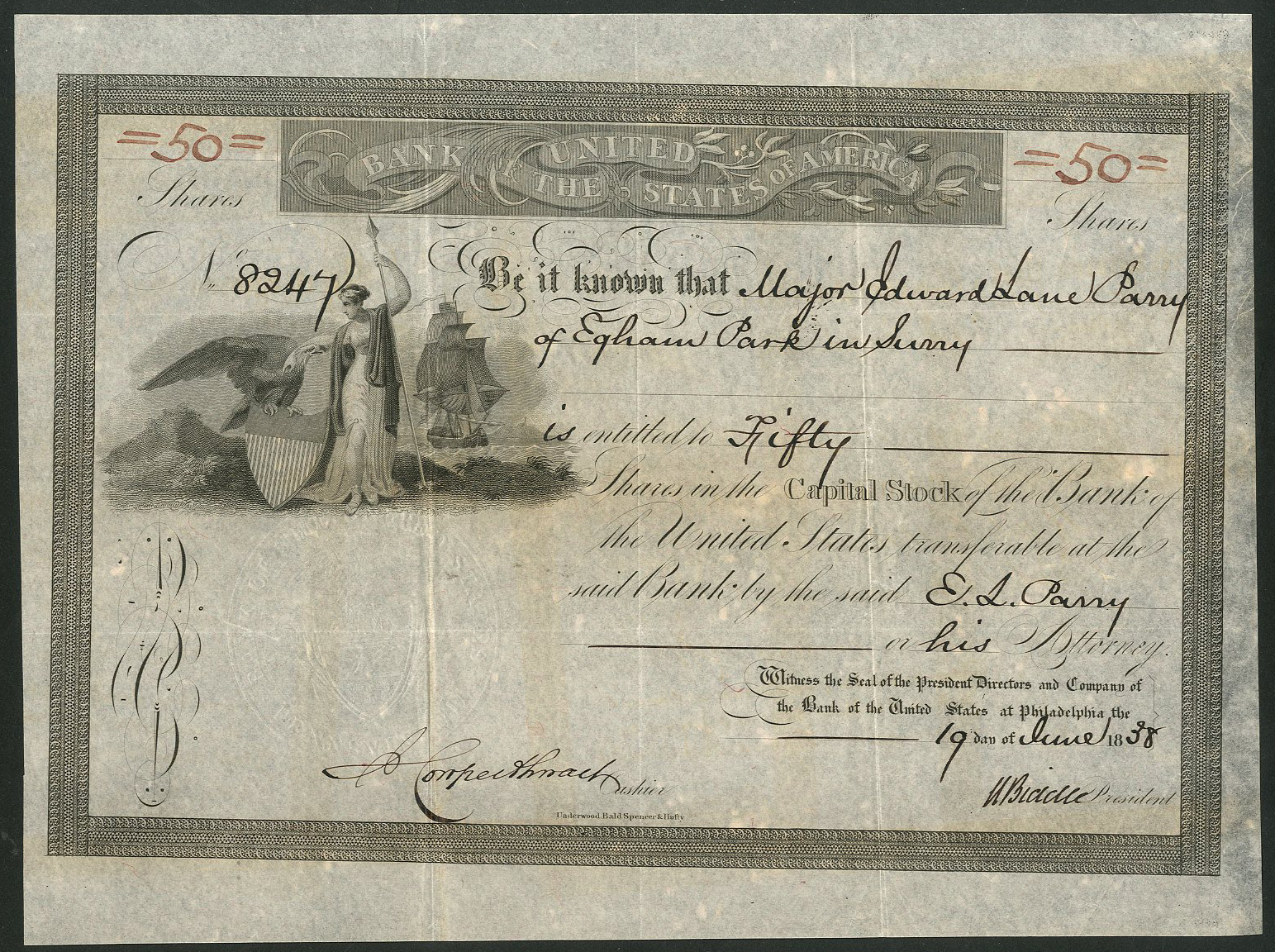

. Twenty percent of its capital was owned by the federal government, the bank's single largest stockholder

A shareholder (in the United States often referred to as stockholder) of corporate stock refers to an individual or legal entity (such as another corporation, a body politic, a trust or partnership) that is registered by the corporation as the l ...

.. Four thousand private investors held 80 percent of the bank's capital, including three thousand Europeans. The bulk of the stocks were held by a few hundred wealthy Americans. In its time, the institution was the largest monied corporation in the world.

The essential function of the bank was to regulate the public credit

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit occu ...

issued by private banking institutions through the fiscal duties it performed for the U.S. Treasury, and to establish a sound and stable national currency

Fiat money is a type of government-issued currency that is not backed by a precious metal, such as gold or silver, nor by any other tangible asset or commodity. Fiat currency is typically designated by the issuing government to be legal tender, ...

... The federal deposits endowed the bank with its regulatory capacity.

Modeled on Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

's First Bank of the United States

The President, Directors and Company of the Bank of the United States, commonly known as the First Bank of the United States, was a National bank (United States), national bank, chartered for a term of twenty years, by the United States Congress ...

,. the Second Bank was chartered by President James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

, who in 1791 had attacked the First Bank as unconstitutional, in 1816 and began operations at its main branch in Philadelphia on January 7, 1817,. managing 25 branch offices nationwide by 1832..

The efforts to renew the bank's charter put the institution at the center of the general election of 1832, in which the bank's president Nicholas Biddle

Nicholas Biddle (January 8, 1786February 27, 1844) was an American financier who served as the third and last president of the Second Bank of the United States (chartered 1816–1836). Throughout his life Biddle worked as an editor, diplomat, au ...

and pro-bank National Republicans

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States which evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John ...

led by Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

clashed with the " hard-money" Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

administration and eastern banking interests in the Bank War

The Bank War was a political struggle that developed over the issue of rechartering the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). The affair resulted in the shutdown of the Bank and its repl ...

. Failing to secure recharter, the Second Bank became a private corporation in 1836,. and underwent liquidation

Liquidation is the process in accounting by which a Company (law), company is brought to an end. The assets and property of the business are redistributed. When a firm has been liquidated, it is sometimes referred to as :wikt:wind up#Noun, w ...

in 1841.. There would not be national banks again until the passage of the National Bank Act

The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 were two United States federal banking acts that established a system of national banks chartered at the federal level, and created the United States National Banking System. They encouraged developmen ...

in 1863–1864.

History

Establishment

The political support for the revival of a national banking system was rooted in the early 19th century transformation of the country from simple Jeffersonian agrarianism towards one interdependent with industrialization and finance.. In the aftermath of theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, the federal government suffered from the disarray of an unregulated currency and a lack of fiscal order; business interests sought security for their government bonds.. A national alliance arose to legislate a national bank to address these needs..

The political climate—dubbed the Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The era saw the collapse of the Fe ...

—favored the development of national programs and institutions, including a protective tariff

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, ...

, internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, can ...

and the revival of a Bank of the United States. Southern and western support for a bank, led by Republican nationalists John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist who served as the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. Born in South Carolina, he adamantly defended American s ...

of South Carolina and Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

of Kentucky, was decisive in the successful chartering effort. The charter was signed into law by James Madison on April 10, 1816. Subsequent efforts by Calhoun and Clay to earmark the bank's $1.5 million establishment "bonus", and annual dividends estimated at $650,000, as a fund for internal improvements, were vetoed by President Madison, on strict constructionist grounds.

Opposition to a new bank emanated from two interests.

Opposition to a new bank emanated from two interests. Old Republican

The tertium quids (sometimes shortened to quids) were various factions of the Jeffersonian Republican Party in the United States during the early 1800s, which gradually faded into political obscurity by the 1820s.

In Latin, '' tertium quid'' m ...

s, represented by John Taylor of Caroline

John Taylor (December 19, 1753August 21, 1824), usually called John Taylor of Caroline (a reference to his home county), was a politician and writer. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates (1779–1781, 1783–1785, 1796–1800) and in the ...

and John Randolph of Roanoke

John Randolph (June 2, 1773May 24, 1833), commonly known as John Randolph of Roanoke,''Roanoke'' refers to Roanoke Plantation in Charlotte County, Virginia, not to the city of the same name. was an American planter, and a politician from Vi ...

, characterized the Second Bank as both constitutionally illegitimate and a direct threat to Jeffersonian agrarianism, state sovereignty and the institution of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, expressed by Taylor's statement that "...if Congress could incorporate a bank, it might emancipate a slave." Hostile to the regulatory effects of the national bank,. private banks—proliferating with or without state charters—had scuttled rechartering of the First Bank in 1811. These interests played significant roles in undermining the institution during the administration of U.S. President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

(1829–1837)..

Economic functions

The Second Bank was a national bank. However, it did not serve the functions of a moderncentral bank

A central bank, reserve bank, national bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the monetary policy of a country or monetary union. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central bank possesses a monopoly on increasing the mo ...

: It did not set monetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to affect monetary and other financial conditions to accomplish broader objectives like high employment and price stability (normally interpreted as a low and stable rat ...

, regulate private banks, hold their excess reserves

Excess reserves are bank reserves held by a bank in excess of a reserve requirement for it set by a central bank.

In the United States, bank reserves for a commercial bank are represented by its cash holdings and any credit balance in an accoun ...

, or act as a lender of last resort

In public finance, a lender of last resort (LOLR) is a financial entity, generally a central bank, that acts as the provider of liquidity to a financial institution which finds itself unable to obtain sufficient liquidity in the interbank ...

.

The bank was launched in the midst of a major global market readjustment as Europe recovered from the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

.. It was charged with restraining uninhibited private bank note issue—already in progress—that threatened to create a credit bubble

Credit (from Latin verb ''credit'', meaning "one believes") is the trust which allows one party to provide money or resources to another party wherein the second party does not reimburse the first party immediately (thereby generating a debt) ...

and the risks of a financial collapse. Government land sales in the West, fueled by European demand for agricultural products, ensured that a speculative bubble would form. Simultaneously, the national bank was engaged in promoting a democratized expansion of credit to accommodate laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

impulses among eastern business entrepreneurs and credit-hungry western and southern farmers.

Under the management of its first president William Jones, the bank failed to control paper money issued from its branch banks in the West and South, contributing to the post-war

A post-war or postwar period is the interval immediately following the end of a war. The term usually refers to a varying period of time after World War II, which ended in 1945. A post-war period can become an interwar period or interbellum, ...

speculative land boom. When the U.S. markets collapsed in the Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic ...

—a result of global economic adjustments—the bank came under withering criticism for its belated tight money policies—policies that exacerbated mass unemployment and plunging property values.. Further, it transpired that branch directors for the Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

office had engaged in fraud and larceny.

Resigning in January 1819, Jones was replaced by Langdon Cheves

Langdon Cheves ( September 17, 1776 – June 26, 1857) was an American politician, lawyer and businessman from South Carolina. He represented the city of Charleston in the United States House of Representatives from 1810 to 1815, where he played ...

, who continued the contraction in credit in an effort to stop inflation and stabilize the bank, even as the economy began to correct. The bank's reaction to the crisis—a clumsy expansion, then a sharp contraction of credit—indicated its weakness, not its strength. The effects were catastrophic, resulting in a protracted recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction that occurs when there is a period of broad decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be tr ...

with mass unemployment and a sharp drop in property values that persisted until 1822. The financial crisis raised doubts among the American public as to the efficacy of paper money, and in whose interests a national system of finance operated.. Upon this widespread disaffection the anti-bank Jacksonian Democrats would mobilize opposition to the bank in the 1830s. The bank was in general disrepute among most Americans when Nicholas Biddle

Nicholas Biddle (January 8, 1786February 27, 1844) was an American financier who served as the third and last president of the Second Bank of the United States (chartered 1816–1836). Throughout his life Biddle worked as an editor, diplomat, au ...

, the third and last president of the bank, was appointed by President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American Founding Father of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. He was the last Founding Father to serve as presiden ...

in 1823..

Under Biddle's guidance, the bank evolved into a powerful institution that produced a strong and sound system of national credit and currency. From 1823 to 1833, Biddle expanded credit steadily, but with restraint, in a manner that served the needs of the expanding American economy. Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan-American politician, diplomat, ethnologist, and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years ...

, former Secretary of the Treasury under Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

and James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

, wrote in 1831 that the bank was fulfilling its charter expectations.

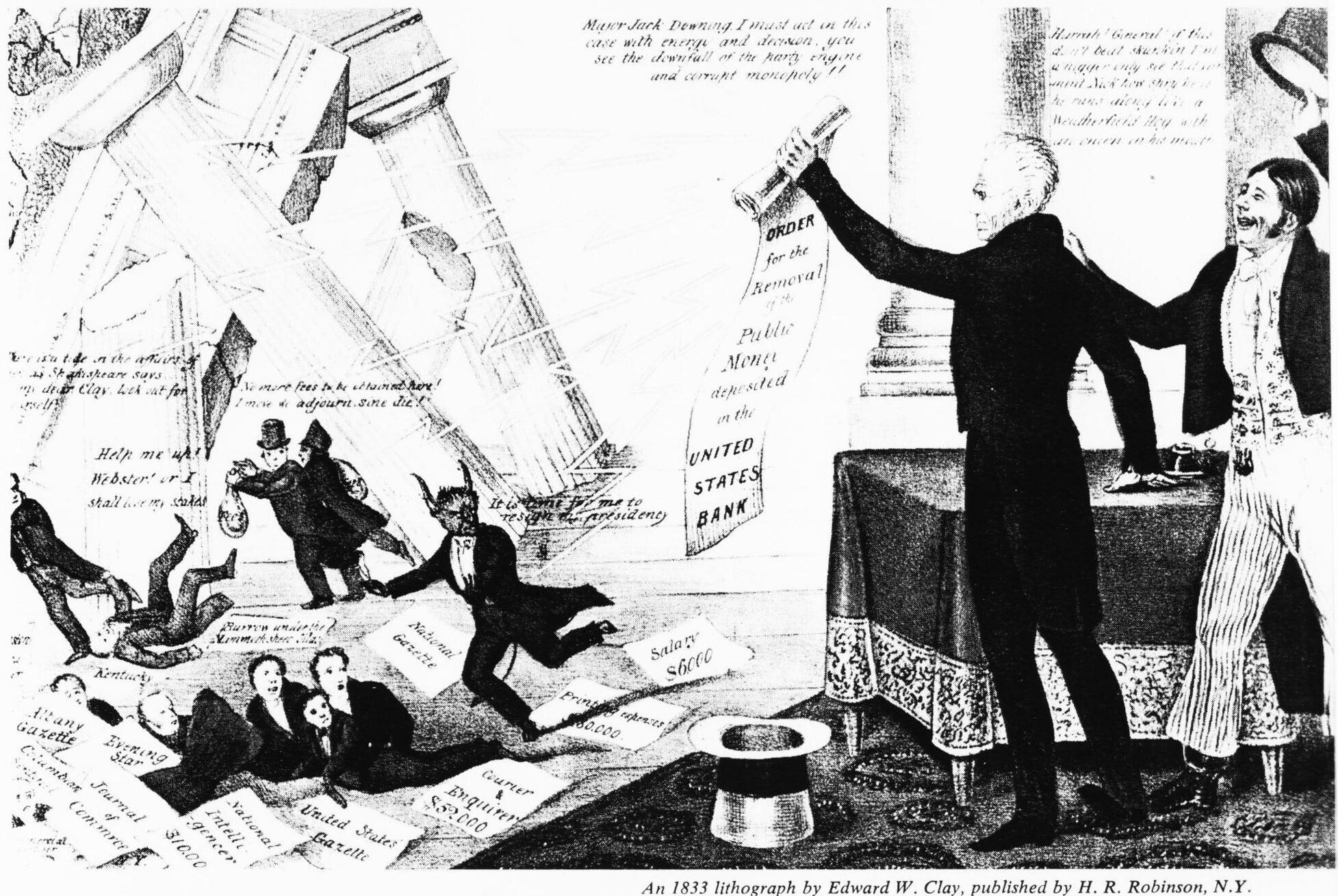

Jackson's Bank War

By the time of Jackson's inauguration in 1829, the bank appeared to be on solid footing. The Supreme Court had affirmed its constitutionality in ''

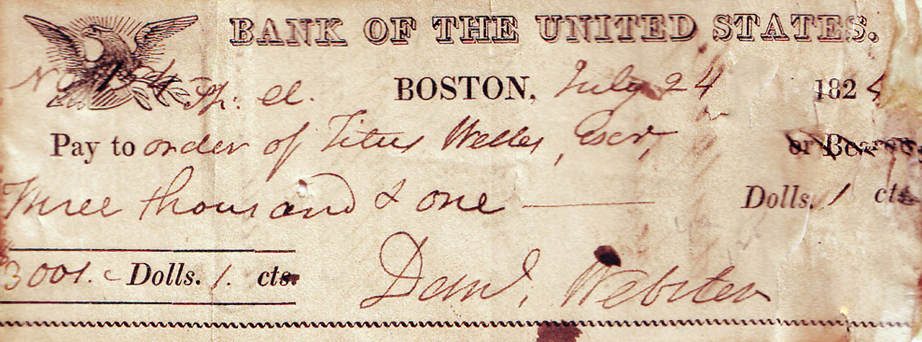

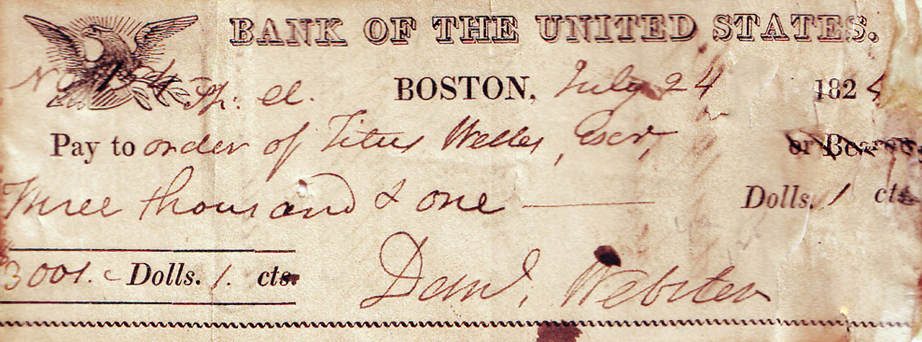

By the time of Jackson's inauguration in 1829, the bank appeared to be on solid footing. The Supreme Court had affirmed its constitutionality in ''McCulloch v. Maryland

''McCulloch v. Maryland'', 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316 (1819), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that defined the scope of the U.S. Congress's legislative power and how it relates to the powers of American state legislatures. The dispute in ...

'', the 1819 case which Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State, U.S. secretary o ...

had argued successfully on its behalf a decade earlier, the Treasury recognized the useful services it provided, and the American currency was healthy and stable. Public perceptions of the national bank were generally positive. The bank first came under attack by the Jackson administration in December 1829, on the grounds that it had failed to produce a stable national currency, and that it lacked constitutional legitimacy.. Both houses of Congress responded with committee investigations and reports affirming the historical precedents for the bank's constitutionality and its pivotal role in furnishing a uniform currency. Jackson rejected these findings, and privately characterized the bank as a corrupt institution, dangerous to American liberties.

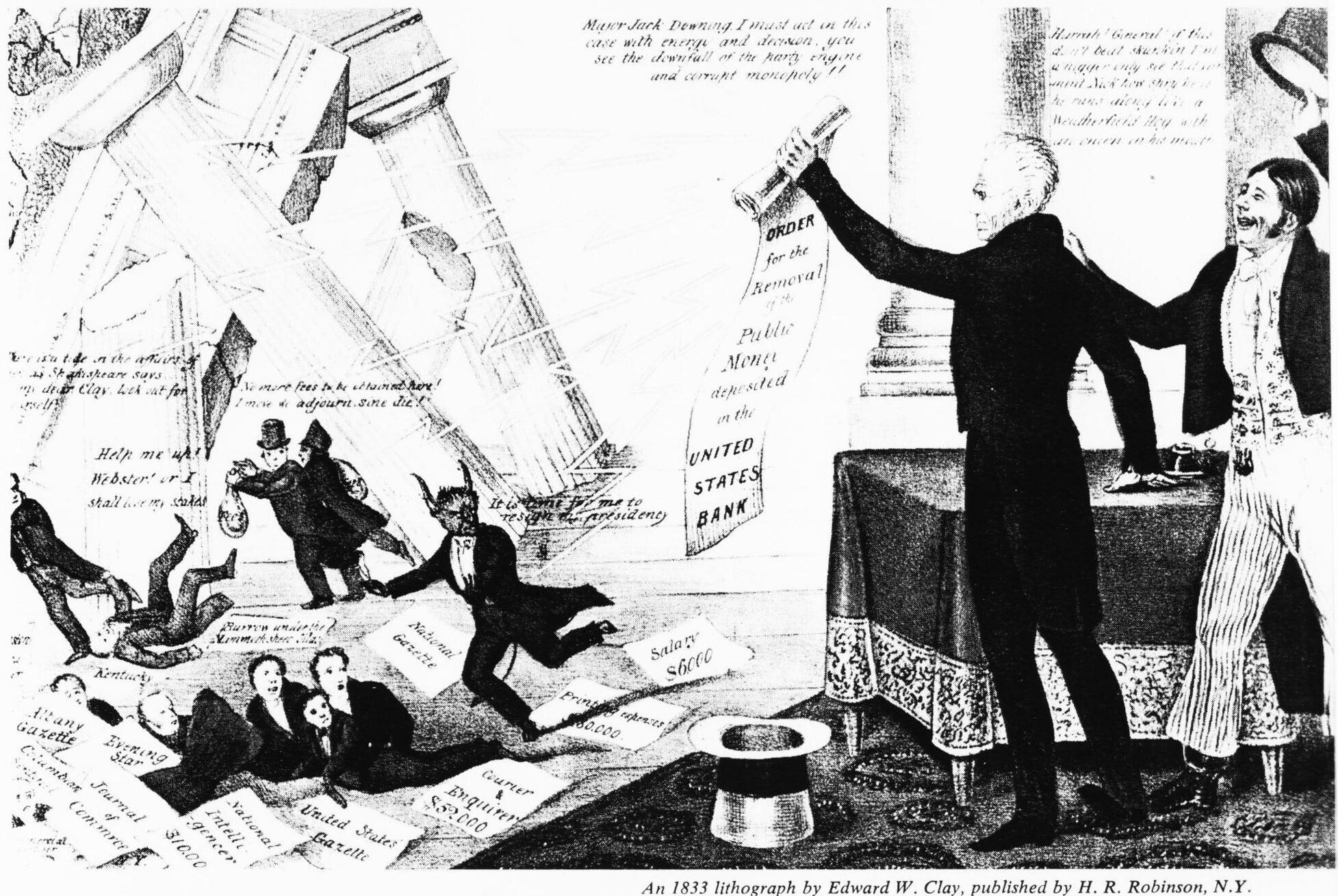

Biddle made repeated overtures to Jackson and his cabinet to secure a compromise on the bank's rechartering (its term due to expire in 1836) without success. Jackson and the anti-bank forces persisted in their condemnation of the bank, provoking an early recharter campaign by pro-bank National Republicans under Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

. Clay's political ultimatum to Jackson—with Biddle's financial and political support—sparked the Bank War

The Bank War was a political struggle that developed over the issue of rechartering the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). The affair resulted in the shutdown of the Bank and its repl ...

. and placed the fate of the bank at center of the 1832 presidential election.

Jackson mobilized his political base by vetoing the recharter bill and, the veto sustained, easily won reelection on his anti-bank platform. Jackson proceeded to destroy the bank as a financial and political force by removing its federal deposits, and in 1833, federal revenue was diverted into selected private banks by executive order, ending the regulatory role of the Second Bank.

In hopes of extorting a rescue of the bank, Biddle induced a short-lived financial crisis that was initially blamed on Jackson's executive action. By 1834, a general backlash against Biddle's tactics developed, ending the panic, and all recharter efforts were abandoned.

State bank

In February 1836, the bank became a private corporation under Pennsylvania law. A shortage of hard currency ensued, causing thePanic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that began a major depression (economics), depression which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages dropped, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment rose, and pes ...

and lasting approximately seven years. The bank suspended payment from October 1839 to January 1841, and permanently in February 1841. It then started a lengthy liquidation process, complicated by lawsuits, that ended in 1852 when it assigned its remaining assets to trustees and surrendered the state charter.

Branches

The bank maintained the following branches. Listed is the year each branch opened. *Augusta, Georgia

Augusta is a city on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. The city lies directly across the Savannah River from North Augusta, South Carolina at the head of its navigable portion. Augusta, the third mos ...

(1817, closed 1817)

* Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the List of United States ...

(1817)

* Boston, Massachusetts

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

(1817)

* Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

(1817)

* Chillicothe, Ohio

Chillicothe ( ) is a city in Ross County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. The population was 22,059 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located along the Scioto River 45 miles (72 km) south of Columbus, Ohio, Columbus, ...

(1817)

* Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

(1817)

* Fayetteville, North Carolina

Fayetteville ( , ) is a city in and the county seat of Cumberland County, North Carolina, United States. It is best known as the home of Fort Bragg, a major U.S. Army installation northwest of the city.

Fayetteville has received the All-Ameri ...

(1817)

* Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city coterminous with and the county seat of Fayette County, Kentucky, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census the city's population was 322,570, making it the List of ...

(1817)

* Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the List of cities in Kentucky, most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeastern United States, Southeast, and the list of United States cities by population, 27th-most-populous city ...

(1817)

* Middletown, Connecticut

Middletown is a city in Middlesex County, Connecticut, United States. Located along the Connecticut River, in the central part of the state, 16 miles (25.749504 km) south of Hartford, Connecticut, Hartford. Middletown is the largest city in the L ...

(1817)

* New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

(1817)

* New York City, New York

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on New York Harbor, one of the world's largest natural harb ...

(1817)

* Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. It had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of cities in Virginia, third-most populous city ...

(1817)

* Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on ...

(1817)

* Providence, Rhode Island

Providence () is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Rhode Island, most populous city of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. The county seat of Providence County, Rhode Island, Providence County, it is o ...

(1817)

* Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

(1817)

* Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Brita ...

(1817)

* Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

(1817)

* Mobile, Alabama

Mobile ( , ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population was 187,041 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. After a successful vote to annex areas west of the city limits in July 2023, Mobil ...

(1826)

* Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

(1827)

* Portland, Maine

Portland is the List of municipalities in Maine, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine and the county seat, seat of Cumberland County, Maine, Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 at the 2020 census. The Portland metropolit ...

(1828)

* Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is a Administrative divisions of New York (state), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York and county seat of Erie County, New York, Erie County. It lies in Western New York at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of ...

(1829)

* St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Miss ...

(1829)

* Burlington, Vermont

Burlington, officially the City of Burlington, is the List of municipalities in Vermont, most populous city in the U.S. state of Vermont and the county seat, seat of Chittenden County, Vermont, Chittenden County. It is located south of the Can ...

(1830)

* Utica, New York

Utica () is the county seat of Oneida County, New York, United States. The tenth-most populous city in New York, its population was 65,283 in the 2020 census. It is located on the Mohawk River in the Mohawk Valley at the foot of the Adiro ...

(1830)

* Natchez, Mississippi

Natchez ( ) is the only city in and the county seat of Adams County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 14,520 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located on the Mississippi River across from Vidalia, Louisiana, Natchez was ...

(1830)

Presidents

* William Jones, January 7, 1817 – January 25, 1819

* James Fisher, January 25, 1819 – March 6, 1819

*

* William Jones, January 7, 1817 – January 25, 1819

* James Fisher, January 25, 1819 – March 6, 1819

* Langdon Cheves

Langdon Cheves ( September 17, 1776 – June 26, 1857) was an American politician, lawyer and businessman from South Carolina. He represented the city of Charleston in the United States House of Representatives from 1810 to 1815, where he played ...

, March 6, 1819 – January 6, 1823

* Nicholas Biddle

Nicholas Biddle (January 8, 1786February 27, 1844) was an American financier who served as the third and last president of the Second Bank of the United States (chartered 1816–1836). Throughout his life Biddle worked as an editor, diplomat, au ...

, January 6, 1823 – March 1836

* Matthew L. Bevan, March 1836 – 1837?

* Nicholas Biddle

Nicholas Biddle (January 8, 1786February 27, 1844) was an American financier who served as the third and last president of the Second Bank of the United States (chartered 1816–1836). Throughout his life Biddle worked as an editor, diplomat, au ...

, March 1836 – February 1839

* Thomas Dunlap, March 1839 – February 1841

* William Drayton

William Drayton (December 30, 1776May 24, 1846) was an American politician, banker, and writer who grew up in Charleston, South Carolina. He was the son of William Drayton Sr., who served as justice of the Province of East Florida (1765–1780 ...

, 1841

* James Robertson, 1841 – March 22, 1852

Terms of charter

The Second Bank was America's national bank, comparable to theBank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

and the Bank of France

The Bank of France ( ) is the national central bank for France within the Eurosystem. It was the French central bank between 1800 and 1998, issuing the French franc. It does not translate its name to English, and thus calls itself ''Banque de F ...

, with one key distinction – the United States government owned one-fifth (20 percent) of its capital. Whereas other national banks of that era were wholly private, the Second Bank was more characteristic of a government bank.

Under its charter, the bank had a capital limit of $35 million, $7.5 million of which represented the government-owned share. It was required to remit a "bonus" payment of $1.5 million, payable in three installments, to the government for the privilege of using the public funds, interest free, in its private banking ventures. The institution was answerable for its performance to the U.S. Treasury and Congress. and subject to Treasury Department inspection.

As exclusive fiscal agent for the federal government, it provided a number of services as part of its charter, including holding and transfer of all U.S. deposits, payment and receipt of all government transactions, and processing of tax payments. In other words, the bank was "the depository of the federal government, which was its principal stockholder and customer."

The chief personnel for the bank comprised 25 directors, five of whom were appointed by the President of the United States, subject to Senate approval. Federally appointed directors were barred from acting as officials in other banks. Two of the three Bank presidents, William Jones and Nicholas Biddle, were chosen from among these government directors.

Headquartered in Philadelphia, the bank was authorized to establish branch offices where it deemed suitable, and these were immune from state taxation.

Regulatory mechanisms

The primary regulatory task of the Second Bank, as chartered by Congress in 1816, was to restrain the uninhibited proliferation of paper money (bank notes) by state or private lenders, which was highly profitable to these institutions. In this capacity, the bank would preside over this democratization of credit,. contributing to a vast and profitable disbursement of bank loans to farmers, small manufacturers and entrepreneurs, encouraging rapid and healthy economic expansion. HistorianBray Hammond

Bray Hammond (November 20, 1886 – July 20, 1968) was an American financial historian and assistant secretary to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in 1944–1950. He won the 1958 Pulitzer Prize for History for '' Banks and ...

describes the mechanism by which the bank exerted its anti-inflationary influence:

Under this banking regime, the impulse towards over-speculation, with the risks of creating a national financial crisis, would be avoided, or at least mitigated. It was just this mechanism that the local private banks found objectionable, because it yoked their lending strategies to the fiscal operations of the national government, requiring them to maintain adequate gold and silver reserves to meet their debt obligations to the U.S. Treasury. The proliferation of private-sector banking institutions – from 31 banks in 1801 to 788 in 1837 – meant that the Second Bank faced strong opposition from this sector during the Jackson administration.

Architecture

The architect of the Second Bank was William Strickland (1788–1854), a former student ofBenjamin Latrobe

Benjamin Henry Boneval Latrobe (May 1, 1764 – September 3, 1820) was a British-American neoclassical architect who immigrated to the United States. He was one of the first formally trained, professional architects in the new United States, dr ...

(1764–1820), the man who is often called the first professionally trained American architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs, and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

. Latrobe and Strickland were both disciples of the Greek Revival

Greek Revival architecture is a architectural style, style that began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe, the United States, and Canada, ...

style. Strickland went on to design many other American public buildings in this style, including financial structures such as the Mechanics National Bank (also in Philadelphia). He also designed the second building for the main U.S. Mint in Philadelphia in 1833, as well as the New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

, Dahlonega

Dahlonega ( ) is the county seat of Lumpkin County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 5,242, and in 2018 the population was estimated to be 6,884.

Dahlonega is located at the north end of Georgia h ...

, and Charlotte branch mints in the mid-to-late 1830s.

Strickland's design for the Second Bank is in essence based on the Parthenon

The Parthenon (; ; ) is a former Ancient Greek temple, temple on the Acropolis of Athens, Athenian Acropolis, Greece, that was dedicated to the Greek gods, goddess Athena. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of c ...

in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, and is a significant early and monumental example of Greek Revival architecture.. The hallmarks of the Greek Revival style can be seen immediately in the north and south façades, which use a large set of steps leading up to the main level platform, known as the stylobate

In classical Greek architecture, a stylobate () is the top step of the crepidoma, the stepped platform upon which colonnades of temple columns are placed (it is the floor of the temple). The platform was built on a leveling course that fl ...

. On top of these, Strickland placed eight severe Doric columns, which are crowned by an entablature containing a triglyph

Triglyph is an architectural term for the vertically channeled tablets of the Doric frieze in classical architecture, so called because of the angular channels in them. The rectangular recessed spaces between the triglyphs on a Doric frieze are ...

frieze

In classical architecture, the frieze is the wide central section of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic order, Ionic or Corinthian order, Corinthian orders, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Patera (architecture), Paterae are also ...

and simple triangular pediment

Pediments are a form of gable in classical architecture, usually of a triangular shape. Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the cornice (an elaborated lintel), or entablature if supported by columns.Summerson, 130 In an ...

. The building appears much as an ancient Greek temple, hence the stylistic name. The interior consists of an entrance hallway in the center of the north façade flanked by two rooms on either side. The entry leads into two central rooms, one after the other, that span the width of the structure east to west. The east and west sides of the first large room are each pierced by a large arched fan window. The building's exterior uses Pennsylvania blue marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock consisting of carbonate minerals (most commonly calcite (CaCO3) or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) that have recrystallized under the influence of heat and pressure. It has a crystalline texture, and is ty ...

, which, due to the manner in which it was cut, has begun to deteriorate due to weak parts of the stone being exposed to the elements. This phenomenon is most visible on the Doric columns of the south façade. Construction lasted from 1819 to 1824.

The Greek Revival style used for the Second Bank contrasts with the earlier, Federal style

Federal-style architecture is the name for the classical architecture built in the United States following the American Revolution between 1780 and 1830, and particularly from 1785 to 1815, which was influenced heavily by the works of And ...

in architecture used for the First Bank of the United States

The President, Directors and Company of the Bank of the United States, commonly known as the First Bank of the United States, was a National bank (United States), national bank, chartered for a term of twenty years, by the United States Congress ...

, which also still stands and is located nearby in Philadelphia. This can be seen in the more Roman-influenced Federal structure's ornate, colossal Corinthian columns

The Corinthian order (, ''Korinthiakós rythmós''; ) is the last developed and most ornate of the three principal classical orders of Ancient Greek architecture and Roman architecture. The other two are the Doric order, which was the earliest, ...

of its façade, which is also embellished by Corinthian pilasters and a symmetric arrangement of sash windows piercing the two stories of the façade. The roofline is also topped by a balustrade

A baluster () is an upright support, often a vertical moulded shaft, square, or lathe-turned form found in stairways, parapets, and other architectural features. In furniture construction it is known as a spindle. Common materials used in its ...

, and the heavy modillion

A modillion is an ornate bracket, more horizontal in shape and less imposing than a corbel. They are often seen underneath a Cornice (architecture), cornice which helps to support them. Modillions are more elaborate than dentils (literally transl ...

s adorning the pediment give the First Bank an appearance more like a Roman villa

A Roman villa was typically a farmhouse or country house in the territory of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, sometimes reaching extravagant proportions.

Nevertheless, the term "Roman villa" generally covers buildings with the common ...

than a Greek temple.

Current building use

Since the bank's closing in 1841, the edifice has performed a variety of functions. Today, it is part ofIndependence National Historical Park

Independence National Historical Park is a federally protected historic district in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania that preserves several sites associated with the American Revolution and the nation's founding history. Administered by the National ...

in Philadelphia. The structure is open to the public free of charge and serves as an art gallery, housing a large collection of portraits of prominent early Americans painted by Charles Willson Peale

Charles Willson Peale (April 15, 1741 – February 22, 1827) was an American painter, military officer, scientist, and naturalist.

In 1775, inspired by the American Revolution, Peale moved from his native Maryland to Philadelphia, where he set ...

and many others. The portrait gallery also includes the wooden statue of George Washington by William Rush.

The building was designated a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a National Register of Historic Places property types, building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the Federal government of the United States, United States government f ...

in 1987 for its architectural and historic significance.

The Wall Street

Wall Street is a street in the Financial District, Manhattan, Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs eight city blocks between Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway in the west and South Street (Manhattan), South Str ...

branch in New York City was converted into the United States Assay Office before it was demolished in 1915. The federal-style façade was saved and installed in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an Encyclopedic museum, encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the List of largest museums, third-largest museum in the world and the List of larg ...

in 1924.

In popular culture

The Second Bank building was described byCharles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

in a chapter of his 1842 travelogue ''American Notes for General Circulation'', Philadelphia, and its solitary prison: We reached the city, late that night. Looking out of my chamber-window, before going to bed, I saw, on the opposite side of the way, a handsome building of white marble, which had a mournful ghost-like aspect, dreary to behold. I attributed this to the sombre influence of the night, and on rising in the morning looked out again, expecting to see its steps and portico thronged with groups of people passing in and out. The door was still tight shut, however; the same cold cheerless air prevailed: and the building looked as if the marble statue of Don Guzman could alone have any business to transact within its gloomy walls. I hastened to inquire its name and purpose, and then my surprise vanished. It was the Tomb of many fortunes; the Great Catacomb of investment; the memorable United States Bank.

The stoppage of this bank, with all its ruinous consequences, had cast (as I was told on every side) a gloom on Philadelphia, under the depressing effect of which it yet laboured. It certainly did seem rather dull and out of spirits..

See also

*Banking in the Jacksonian Era

The Second Bank of the United States opened in January 1817, six years after the First Bank of the United States lost its charter. The Second Bank of the United States was headquartered in Carpenter's Hall, Philadelphia, the same as the First B ...

* Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of ...

* Federal Reserve Act

The Federal Reserve Act was passed by the 63rd United States Congress and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December 23, 1913. The law created the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States.

After Dem ...

* First Bank of the United States

The President, Directors and Company of the Bank of the United States, commonly known as the First Bank of the United States, was a National bank (United States), national bank, chartered for a term of twenty years, by the United States Congress ...

* History of central banking in the United States

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some theorists categ ...

* ''McCulloch v. Maryland

''McCulloch v. Maryland'', 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316 (1819), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that defined the scope of the U.S. Congress's legislative power and how it relates to the powers of American state legislatures. The dispute in ...

''

* Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that began a major depression (economics), depression which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages dropped, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment rose, and pes ...

* List of National Historic Landmarks in Philadelphia

There are 67 National Historic Landmarks within Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

See also the List of National Historic Landmarks in Pennsylvania, which covers the 102 landmarks in the rest of the state.

Current listings

...

* National Register of Historic Places listings in Center City, Philadelphia

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* *online review

* * * * * * Feller, Daniel. "The Bank War", in Julian E. Zelizer, ed. ''The American Congress'' (2004), pp 93–111. * * * * * * * * * * * Kahan, Paul. ''The Bank War: Andrew Jackson, Nicholas Biddle, and the Fight for American Finance'' (Yardley: Westholme, 2016. xii, 187 pp. * *

online review

* * * * * * * * * Ratner, Sidney, James H. Soltow, and Richard Sylla. ''The Evolution of the American Economy: Growth, Welfare, and Decision Making''. (1993) * * * * * * Schweikart, Larry. ''Banking in the American South from the Age of Jackson to Reconstruction'' (1987) * Taylor; George Rogers, ed. ''Jackson Versus Biddle: The Struggle over the Second Bank of the United States'' (1949). * Temin, Peter. ''The Jacksonian Economy'' (1969) * * * *

External links

Second Bank

– official site at Independence Hall National Historical Park

Documents produced by the Second Bank of the United States

on

FRASER Fraser may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Fraser Point, South Orkney Islands

Australia

* Fraser, Australian Capital Territory, a suburb in the Canberra district of Belconnen

* Division of Fraser (Australian Capital Territory), a former federal ...

Andrew Jackson on the Web : Bank of the United States

* {{Authority control 14th United States Congress 1816 establishments in Massachusetts 1820s architecture in the United States American companies disestablished in 1841 Art museums and galleries in Philadelphia Bank buildings in Philadelphia Bank buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Philadelphia Banks based in Philadelphia Banks disestablished in 1841 Banks established in 1816 Buildings and structures in Independence National Historical Park Chestnut Street (Philadelphia) Commercial buildings completed in 1824 Defunct banks of the United States Defunct companies based in Pennsylvania Era of Good Feelings Financial history of the United States

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

Greek Revival architecture in Pennsylvania

Historic American Buildings Survey in Philadelphia

Independence National Historical Park

Museums in Philadelphia

National Historic Landmarks in Pennsylvania

Neoclassical architecture in Pennsylvania

Presidency of Andrew Jackson

Presidency of James Madison