Marine life, sea life or ocean life is the collective

ecological communities

In ecology, a community is a group or association of populations of two or more different species occupying the same geographical area at the same time, also known as a biocoenosis, biotic community, biological community, ecological community ...

that encompass all

aquatic animal

An aquatic animal is any animal, whether vertebrate or invertebrate, that lives in a body of water for all or most of its lifetime. Aquatic animals generally conduct gas exchange in water by extracting dissolved oxygen via specialised respirato ...

s,

plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s,

algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

,

fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

,

protists

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any Eukaryote, eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, Embryophyte, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a Clade, natural group, or clade, but are a Paraphyly, paraphyletic grouping of all descendants o ...

,

single-celled

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell (biology), cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic ...

microorganisms

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic size, which may exist in its single-celled form or as a colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen microbial life was suspected from antiquity, with an early attestation in ...

and associated

virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es living in the

saline water

Saline water (more commonly known as salt water) is water that contains a high concentration of dissolved salts (mainly sodium chloride). On the United States Geological Survey (USGS) salinity scale, saline water is saltier than brackish wat ...

of

marine habitat

A marine habitat is a habitat that supports marine life. Marine life depends in some way on the seawater, saltwater that is in the sea (the term ''marine'' comes from the Latin ''mare'', meaning sea or ocean). A habitat is an ecological or Na ...

s, either the

sea water

Seawater, or sea water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has approximate ...

of

marginal sea

This is a list of seas of the World Ocean, including marginal seas, areas of water, various gulfs, bights, bays, and straits. In many cases it is a matter of tradition for a body of water to be named a sea or a bay, etc., therefore all these ...

s and

ocean

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Indian, Southern Ocean ...

s, or the

brackish water

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuary ...

of

coast

A coast (coastline, shoreline, seashore) is the land next to the sea or the line that forms the boundary between the land and the ocean or a lake. Coasts are influenced by the topography of the surrounding landscape and by aquatic erosion, su ...

al

wetland

A wetland is a distinct semi-aquatic ecosystem whose groundcovers are flooded or saturated in water, either permanently, for years or decades, or only seasonally. Flooding results in oxygen-poor ( anoxic) processes taking place, especially ...

s,

lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into ''coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons'') an ...

s,

estuaries

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environm ...

and

inland sea

An inland sea (also known as an epeiric sea or an epicontinental sea) is a continental body of water which is very large in area and is either completely surrounded by dry land (landlocked), or connected to an ocean by a river, strait or " arm of ...

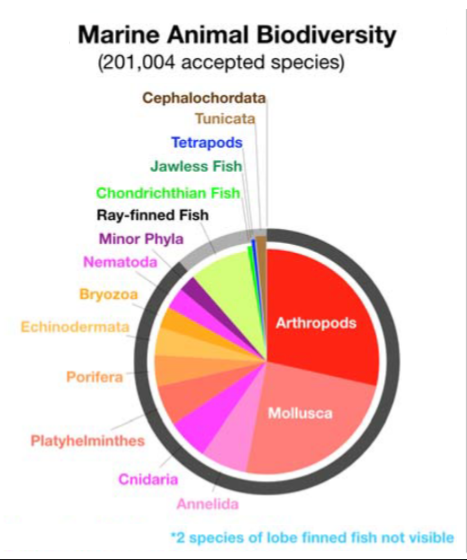

s. , more than 242,000 marine

species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

have been documented, and perhaps two million marine species are yet to be documented. An average of 2,332 new species per year are being described.

Marine life is studied scientifically in both

marine biology

Marine biology is the scientific study of the biology of marine life, organisms that inhabit the sea. Given that in biology many scientific classification, phyla, family (biology), families and genera have some species that live in the sea and ...

and in

biological oceanography

Biological oceanography is the study of how organisms affect and are affected by the physics, chemistry, and geology of the oceanographic system. Biological oceanography may also be referred to as ocean ecology, in which the root word of ecology ...

.

By volume, oceans provide about 90% of the living space on

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

,

and served as the

cradle of life

Abiogenesis is the natural process by which life arises from abiotic component, non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothesis is that the transition from non-living to organism, living entities on ...

and vital biotic sanctuaries throughout

Earth's geological history

The geological history of Earth follows the major geological events in Earth's past based on the geologic time scale, a system of chronological measurement based on the study of the planet's rock layers (stratigraphy). Earth formed approximat ...

. The

earliest known life forms

The earliest known life forms on Earth may be as old as 4.1 billion years (or Year#SI prefix multipliers, Ga) according to biologically fractionated graphite inside a single zircon grain in the Jack Hills range of Australia. The earliest evidenc ...

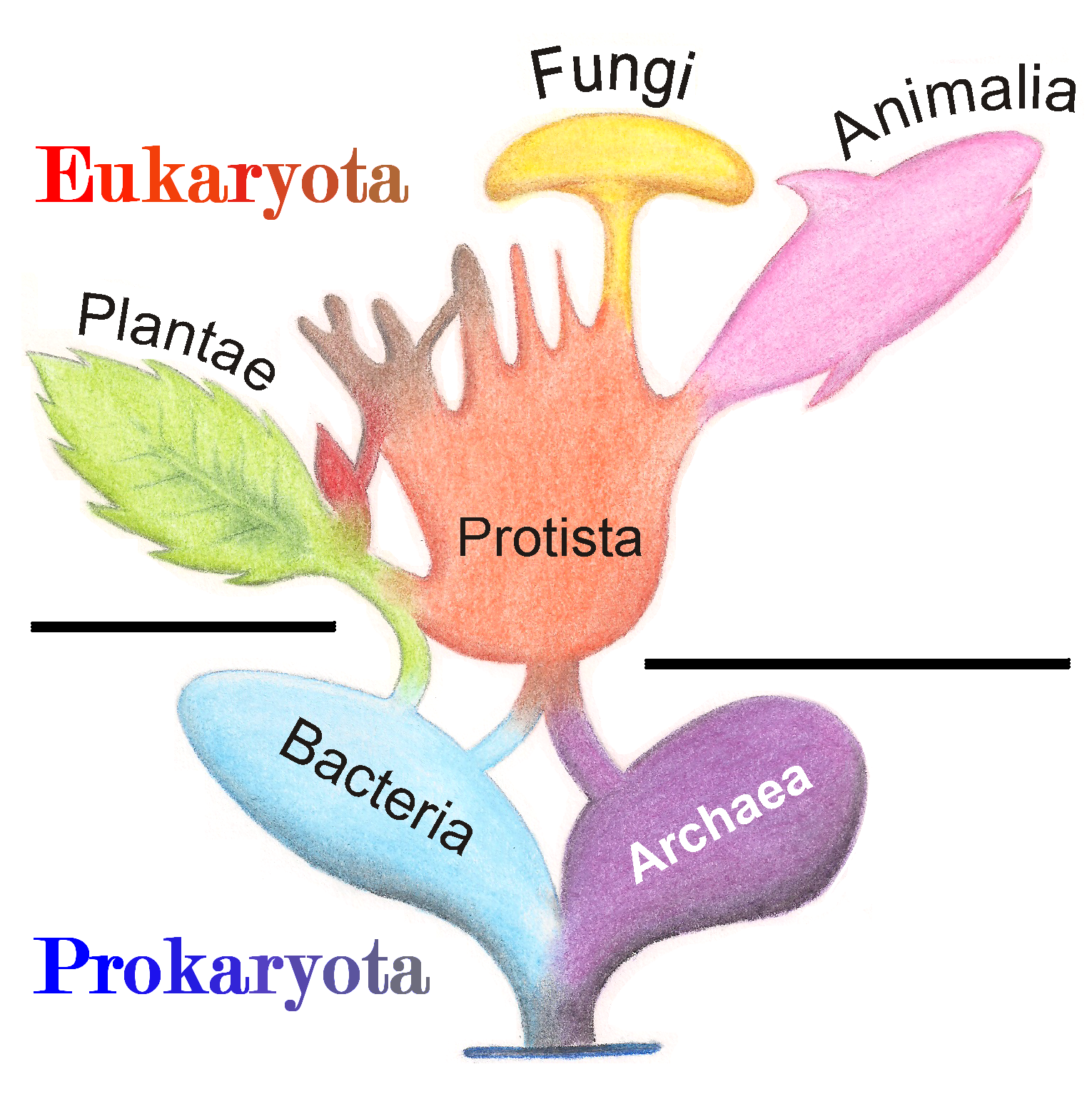

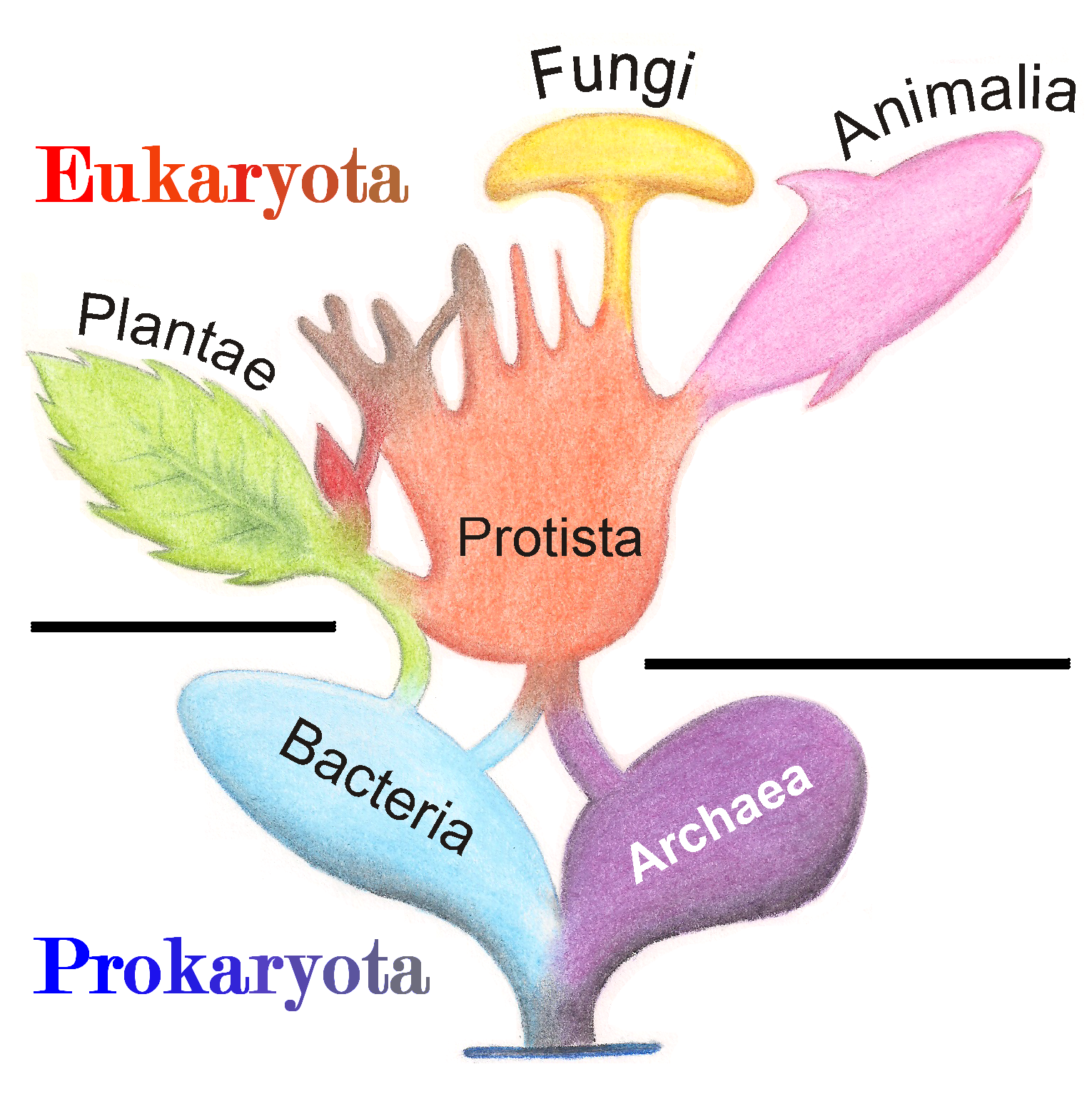

evolved as

anaerobic

Anaerobic means "living, active, occurring, or existing in the absence of free oxygen", as opposed to aerobic which means "living, active, or occurring only in the presence of oxygen." Anaerobic may also refer to:

*Adhesive#Anaerobic, Anaerobic ad ...

prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s (

archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

and

bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

) in the

Archean

The Archean ( , also spelled Archaean or Archæan), in older sources sometimes called the Archaeozoic, is the second of the four geologic eons of Earth's history of Earth, history, preceded by the Hadean Eon and followed by the Proterozoic and t ...

oceans around the

deep sea

The deep sea is broadly defined as the ocean depth where light begins to fade, at an approximate depth of or the point of transition from continental shelves to continental slopes. Conditions within the deep sea are a combination of low tempe ...

hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

s, before

photoautotroph

Photoautotrophs are organisms that can utilize light energy from sunlight, and elements (such as carbon) from inorganic compounds, to produce organic materials needed to sustain their own metabolism (i.e. autotrophy). Such biological activitie ...

s appeared and allowed the

microbial mat

A microbial mat is a multi-layered sheet or biofilm of microbial colonies, composed of mainly bacteria and/or archaea. Microbial mats grow at interfaces between different types of material, mostly on submerged or moist surfaces, but a few surviv ...

s to expand into

shallow water marine environment

Shallow water marine environment refers to the neritic marine environment between the shore and the shelf break. This environment is characterized by oceanic, geological and biological conditions, as described below, and water in this environmen ...

s. The

Great Oxygenation Event

The Great Oxidation Event (GOE) or Great Oxygenation Event, also called the Oxygen Catastrophe, Oxygen Revolution, Oxygen Crisis or Oxygen Holocaust, was a time interval during the Earth's Paleoproterozoic era when the Earth's atmosphere and ...

of the early

Proterozoic

The Proterozoic ( ) is the third of the four geologic eons of Earth's history, spanning the time interval from 2500 to 538.8 Mya, and is the longest eon of Earth's geologic time scale. It is preceded by the Archean and followed by the Phanerozo ...

significantly altered the

marine chemistry

Marine chemistry, also known as ocean chemistry or chemical oceanography, is the study of the chemical composition and processes of the world’s oceans, including the interactions between seawater, the atmosphere, the seafloor, and marine organ ...

, which likely caused a widespread anaerobe

extinction event

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp fall in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. It occ ...

but also led to the

evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

of

eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s through

symbiogenesis

Symbiogenesis (endosymbiotic theory, or serial endosymbiotic theory) is the leading evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms. The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and possibl ...

between surviving anaerobes and

aerobe

An aerobic organism or aerobe is an organism that can survive and grow in an oxygenated environment. The ability to exhibit aerobic respiration may yield benefits to the aerobic organism, as aerobic respiration yields more energy than anaerobic ...

s.

Complex life

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, unlike unicellular organisms. All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- and pa ...

eventually arose out of marine eukaryotes during the

Neoproterozoic

The Neoproterozoic Era is the last of the three geologic eras of the Proterozoic geologic eon, eon, spanning from 1 billion to 538.8 million years ago, and is the last era of the Precambrian "supereon". It is preceded by the Mesoproterozoic era an ...

, and which culminated in a large

evolutionary radiation

An evolutionary radiation is an increase in taxonomic diversity that is caused by elevated rates of speciation, that may or may not be associated with an increase in morphological disparity. A significantly large and diverse radiation within ...

event of

mostly sessile macrofaunae known as the

Avalon Explosion

The Avalon explosion, named from the Precambrian faunal trace fossils discovered on the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland, eastern Canada, is a proposed evolutionary radiation of prehistoric animals about 575 million years ago in the Ediacaran ...

. This was followed in the early

Phanerozoic

The Phanerozoic is the current and the latest of the four eon (geology), geologic eons in the Earth's geologic time scale, covering the time period from 538.8 million years ago to the present. It is the eon during which abundant animal and ...

by a more prominent radiation event known as the

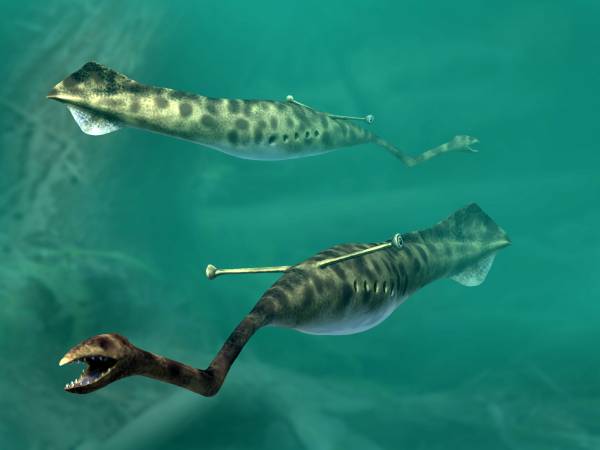

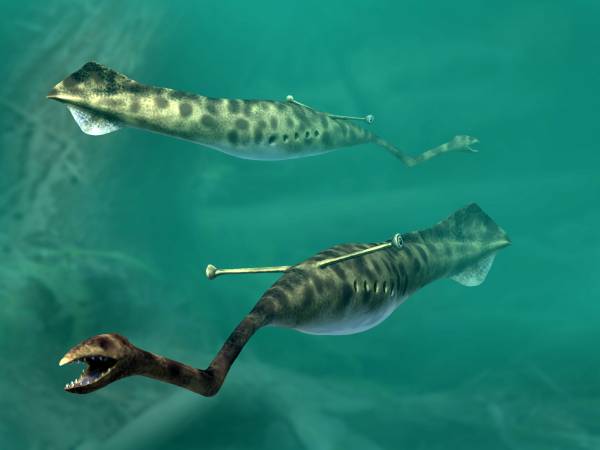

Cambrian Explosion, where actively moving

eumetazoan became prevalent. These marine life also expanded into

fresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salt (chemistry), salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include ...

s, where fungi and

green algae

The green algae (: green alga) are a group of chlorophyll-containing autotrophic eukaryotes consisting of the phylum Prasinodermophyta and its unnamed sister group that contains the Chlorophyta and Charophyta/ Streptophyta. The land plants ...

that were washed ashore onto

riparian area

A riparian zone or riparian area is the interface between land and a river or stream. In some regions, the terms riparian woodland, riparian forest, riparian buffer zone, riparian corridor, and riparian strip are used to characterize a ripar ...

s started to take hold later during the

Ordivician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era, and the second of twelve periods of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period Ma (millio ...

before

rapidly expanding inland during the

Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 23.5 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the third and shortest period of t ...

and

Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

, paving the way for

terrestrial ecosystem

Terrestrial ecosystems are ecosystems that are found on land. Examples include tundra, taiga, temperate deciduous forest, tropical rain forest, grassland, deserts.

Terrestrial ecosystems differ from aquatic ecosystems by the predominant presen ...

s to develop.

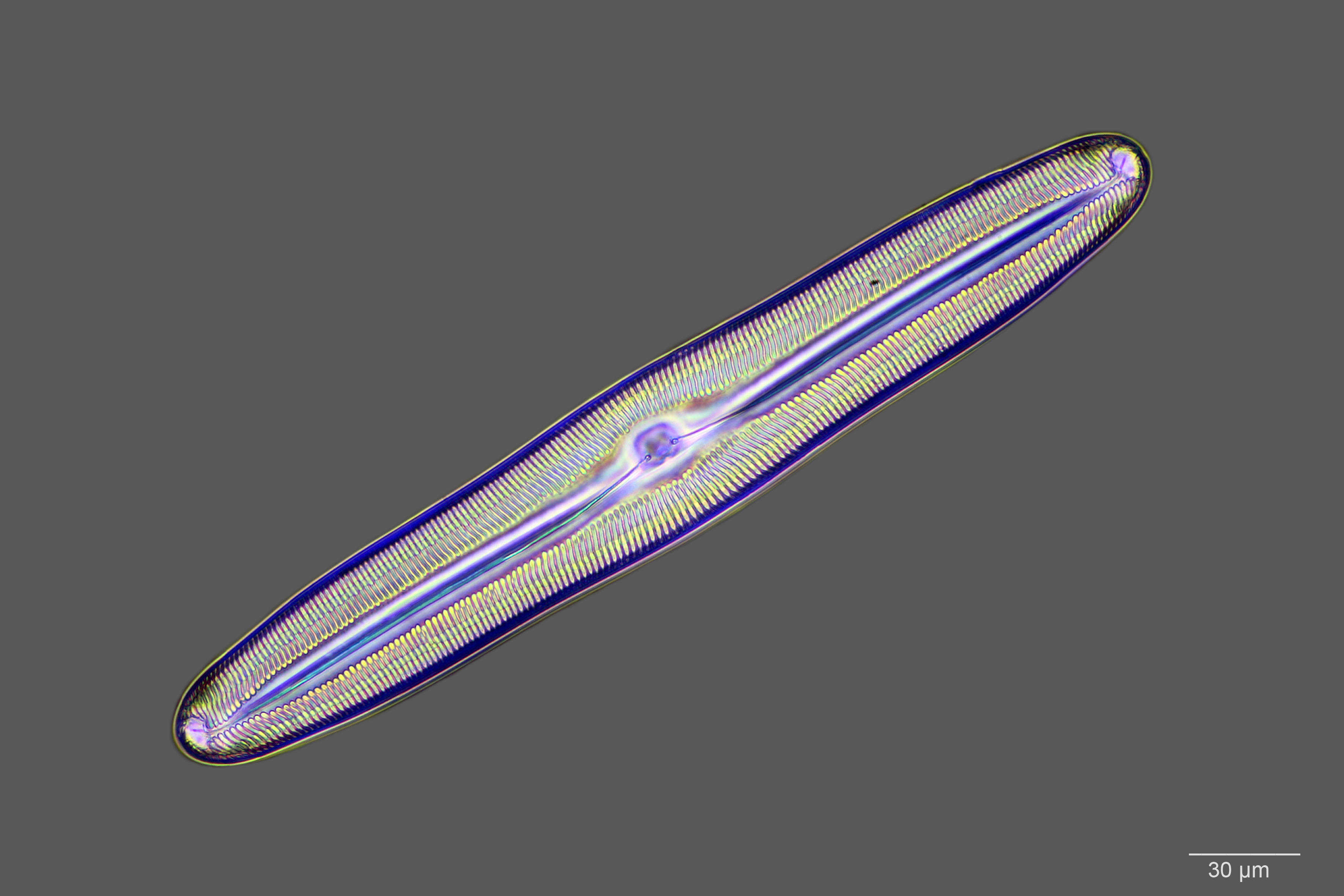

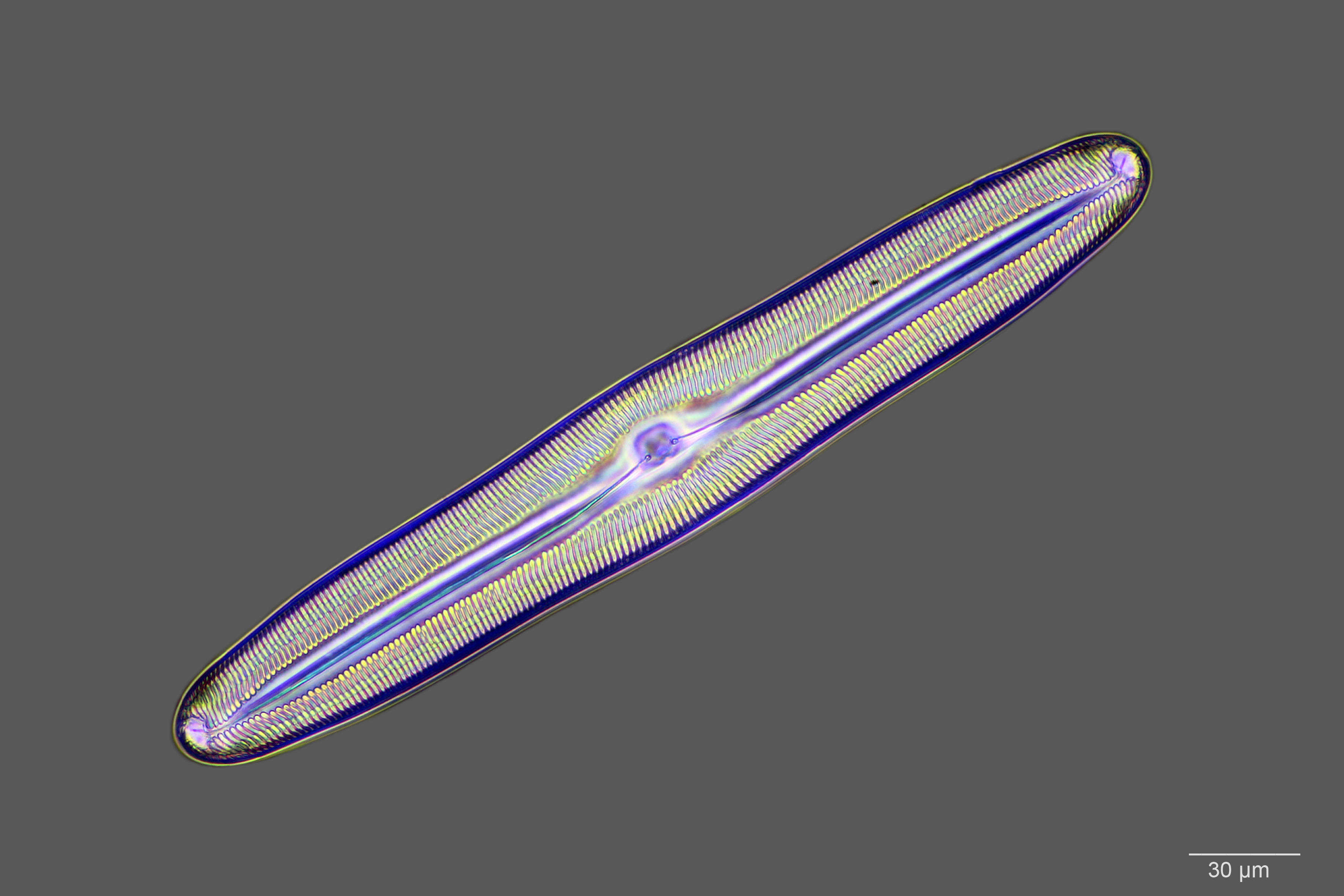

Today, marine species range in size from the microscopic

phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

, which can be as small as 0.02–

micrometers; to huge

cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

s like the

blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

, which can reach in length. Marine microorganisms have been variously estimated as constituting about 70%

or about 90%

[ Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under ]

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

of the total marine

biomass

Biomass is a term used in several contexts: in the context of ecology it means living organisms, and in the context of bioenergy it means matter from recently living (but now dead) organisms. In the latter context, there are variations in how ...

.

Marine primary producers, mainly

cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

and

chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle, organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant cell, plant and algae, algal cells. Chloroplasts have a high concentration of chlorophyll pigments which captur ...

ic

algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

,

produce oxygen and

sequester carbon

Carbon sequestration is the process of storing carbon in a carbon pool. It plays a crucial role in limiting climate change by reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. There are two main types of carbon sequestration: biologic ( ...

via

photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

, which generate enormous biomass and significantly influence the

atmospheric chemistry

Atmospheric chemistry is a branch of atmospheric science that studies the chemistry of the Earth's atmosphere and that of other planets. This multidisciplinary approach of research draws on environmental chemistry, physics, meteorology, comput ...

.

Migratory species, such as

oceanodromous

Fish migration is mass relocation by fish from one area or body of water to another. Many types of fish migrate on a regular basis, on time scales ranging from daily to annually or longer, and over distances ranging from a few metres to thousa ...

and

anadromous

Fish migration is mass relocation by fish from one area or body of water to another. Many types of fish migrate on a regular basis, on time scales ranging from daily to annually or longer, and over distances ranging from a few metres to thousa ...

fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

, also create biomass and

biological energy

{{Research paper, date=August 2024

Biological thermodynamics (Thermodynamics of biological systems) is a science that explains the nature and general laws of thermodynamic processes occurring in living organisms as nonequilibrium thermodynamic sy ...

transfer between different regions of Earth, with many serving as

keystone species

A keystone species is a species that has a disproportionately large effect on its natural environment relative to its abundance. The concept was introduced in 1969 by the zoologist Robert T. Paine. Keystone species play a critical role in main ...

of various ecosystems. At a fundamental level, marine life affects the nature of the planet, and in part, shape and protect shorelines, and some marine organisms (e.g.

coral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoology), polyps. Coral species include the important Coral ...

s) even help create new

land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of Earth not submerged by the ocean or another body of water. It makes up 29.2% of Earth's surface and includes all continents and islands. Earth's land sur ...

via accumulated

reef

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral, or similar relatively stable material lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic component, abiotic (non-living) processes such as deposition (geol ...

-building.

Marine life can be roughly grouped into

autotroph

An autotroph is an organism that can convert Abiotic component, abiotic sources of energy into energy stored in organic compounds, which can be used by Heterotroph, other organisms. Autotrophs produce complex organic compounds (such as carbohy ...

s and

heterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

s according to their roles within the

food web

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Position in the food web, or trophic level, is used in ecology to broadly classify organisms as autotrophs or he ...

: the former include photosynthetic and the much rarer

chemosynthetic

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon-containing molecules (usually carbon dioxide or methane) and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic compounds (e.g., hydrogen gas, hydrog ...

organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

s (

chemoautotroph

A chemotroph is an organism that obtains energy by the oxidation of electron donors in their environments. These molecules can be organic (chemoorganotrophs) or inorganic (chemolithotrophs). The chemotroph designation is in contrast to phototroph ...

s) that can convert

inorganic molecules into

organic compound

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

s using energy from

sunlight

Sunlight is the portion of the electromagnetic radiation which is emitted by the Sun (i.e. solar radiation) and received by the Earth, in particular the visible spectrum, visible light perceptible to the human eye as well as invisible infrare ...

or

exothermic

In thermodynamics, an exothermic process () is a thermodynamic process or reaction that releases energy from the system to its surroundings, usually in the form of heat, but also in a form of light (e.g. a spark, flame, or flash), electricity (e ...

oxidation

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

, such as cyanobacteria,

iron-oxidizing bacteria

Iron-oxidizing bacteria in surface water

Iron-oxidizing bacteria (or iron bacteria) are chemotrophic bacteria that derive energy by oxidizing dissolved iron. They are known to grow and proliferate in waters containing iron concentrations as low a ...

, algae (

seaweed

Seaweed, or macroalgae, refers to thousands of species of macroscopic, multicellular, marine algae. The term includes some types of ''Rhodophyta'' (red), '' Phaeophyta'' (brown) and ''Chlorophyta'' (green) macroalgae. Seaweed species such as ...

s and various

microalgae

Microalgae or microphytes are microscopic scale, microscopic algae invisible to the naked eye. They are phytoplankton typically found in freshwater and marine life, marine systems, living in both the water column and sediment. They are unicellul ...

) and

seagrass

Seagrasses are the only flowering plants which grow in marine (ocean), marine environments. There are about 60 species of fully marine seagrasses which belong to four Family (biology), families (Posidoniaceae, Zosteraceae, Hydrocharitaceae and ...

; the latter include all the rest that must

feed on other organisms to acquire

nutrient

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excret ...

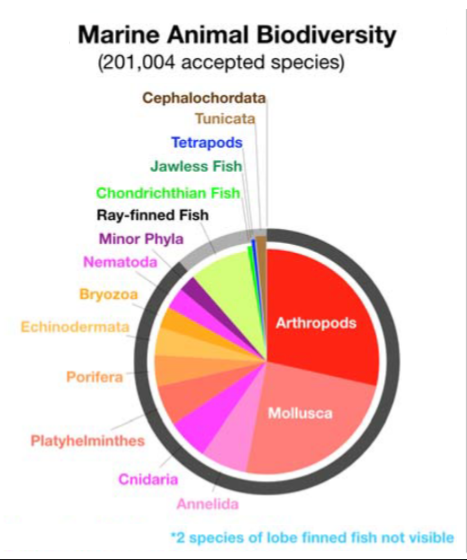

s and energy, which include animals, fungi, protists and non-photosynthetic microorganisms. Marine animals are further informally divided into

marine vertebrates and marine

invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s, both of which are

polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage that includes organisms with mixed evolutionary origin but does not include their most recent common ancestor. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as Homoplasy, homoplasies ...

groupings with the former including all

saltwater fish

Saltwater fish, also called marine fish or sea fish, are fish that live in seawater. Saltwater fish can swim and live alone or in a large group called a school.

Saltwater fish are very commonly kept in aquariums for entertainment. Many saltwater ...

,

marine mammal

Marine mammals are mammals that rely on marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as cetaceans, pinnipeds, sirenians, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their reliance on marine enviro ...

s,

marine reptile

Marine reptiles are reptiles which have become secondarily adapted for an aquatic or semiaquatic life in a marine environment. Only about 100 of the 12,000 extant reptile species and subspecies are classed as marine reptiles, including mari ...

s and

seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adaptation, adapted to life within the marine ecosystem, marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent ...

s, and the latter include all that are not considered

vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s. Generally, marine vertebrates are much more

nekton

Nekton or necton (from the ) is any aquatic organism that can actively and persistently propel itself through a water column (i.e. swimming) without touching the bottom. Nektons generally have powerful tails and appendages (e.g. fins, pleopods, ...

ic and

metabolic

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the ...

ally demanding of

oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

and nutrients, often suffering distress or even

mass deaths (a.k.a. "

fish kill

The term fish kill, known also as fish die-off, refers to a localized mass mortality event, mass die-off of fish populations which may also be associated with more generalized mortality of aquatic life.University of Florida. Gainesville, FL (200 ...

s") during

anoxic event

An anoxic event describes a period wherein large expanses of Earth's oceans were depleted of dissolved oxygen (O2), creating toxic, euxinic ( anoxic and sulfidic) waters. Although anoxic events have not happened for millions of years, the geol ...

s, while marine invertebrates are a lot more

hypoxia-tolerant and exhibit a wide range of morphological and physiological modifications to survive in

poorly oxygenated waters.

Water

There is no life without water. It has been described as the ''universal solvent'' for its ability to

dissolve many substances, and as the ''solvent of life''. Water is the only common substance to exist as a

solid

Solid is a state of matter where molecules are closely packed and can not slide past each other. Solids resist compression, expansion, or external forces that would alter its shape, with the degree to which they are resisted dependent upon the ...

, liquid, and

gas

Gas is a state of matter that has neither a fixed volume nor a fixed shape and is a compressible fluid. A ''pure gas'' is made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon) or molecules of either a single type of atom ( elements such as ...

under conditions normal to life on Earth. The

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

winner

Albert Szent-Györgyi

Albert Imre Szent-Györgyi de Rapoltu Mare, Nagyrápolt (; September 16, 1893 – October 22, 1986) was a Hungarian biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1937. He is credited with first isolating vitamin C and disc ...

referred to water as the ''mater und matrix'': the mother and womb of life.

The abundance of surface water on Earth is a unique feature in the

Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

. Earth's

hydrosphere

The hydrosphere () is the combined mass of water found on, under, and above the Planetary surface, surface of a planet, minor planet, or natural satellite. Although Earth's hydrosphere has been around for about 4 billion years, it continues to ch ...

consists chiefly of the oceans but technically includes all water surfaces in the world, including inland seas, lakes, rivers, and underground waters down to a depth of . The deepest underwater location is

Challenger Deep

The Challenger Deep is the List of submarine topographical features#List of oceanic trenches, deepest known point of the seabed of Earth, located in the western Pacific Ocean at the southern end of the Mariana Trench, in the ocean territory o ...

of the

Mariana Trench

The Mariana Trench is an oceanic trench located in the western Pacific Ocean, about east of the Mariana Islands; it is the deep sea, deepest oceanic trench on Earth. It is crescent-shaped and measures about in length and in width. The maxi ...

in the

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

, having a depth of .

[

Conventionally, the planet is divided into five separate oceans, but these oceans all connect into a single ]world ocean

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Antarctic/Southern, and ...

. The mass of this world ocean is 1.35 metric ton

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1,000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton in the United States to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the sh ...

s or about 1/4400 of Earth's total mass. The world ocean covers an area of with a mean depth of , resulting in an estimated volume of . About 97.5% of the water on Earth is saline; the remaining 2.5% is

About 97.5% of the water on Earth is saline; the remaining 2.5% is fresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salt (chemistry), salts and other total dissolved solids. The term excludes seawater and brackish water, but it does include ...

. Most fresh water – about 69% – is present as ice in ice cap

In glaciology, an ice cap is a mass of ice that covers less than of land area (usually covering a highland area). Larger ice masses covering more than are termed ice sheets.

Description

By definition, ice caps are not constrained by topogra ...

s and glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

s. The average salinity of Earth's oceans is about of salt per kilogram of seawater (3.5% salt).volcanic activity

Volcanism, vulcanism, volcanicity, or volcanic activity is the phenomenon where solids, liquids, gases, and their mixtures erupt to the surface of a solid-surface astronomical body such as a planet or a moon. It is caused by the presence of a he ...

or extracted from cool igneous rock

Igneous rock ( ), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rocks are formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava.

The magma can be derived from partial ...

s.heat reservoir

A thermal reservoir, also thermal energy reservoir or thermal bath, is a thermodynamic system with a heat capacity so large that the temperature of the reservoir changes relatively little when a significant amount of heat is added or extracted. ...

.El Niño-Southern Oscillation

EL, El or el may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Fictional entities

* El, a character from the manga series ''Shugo Chara!'' by Peach-Pit

* Eleven (''Stranger Things'') (El), a fictional character in the TV series ''Stranger Things''

* El, fami ...

.Arthur C. Clarke

Sir Arthur Charles Clarke (16 December 191719 March 2008) was an English science fiction writer, science writer, futurist, inventor, undersea explorer, and television series host.

Clarke co-wrote the screenplay for the 1968 film '' 2001: A ...

has pointed out it would be more appropriate to refer to planet Earth as planet Ocean.

However, water is found elsewhere in the Solar System. Europa

Europa may refer to:

Places

* Europa (Roman province), a province within the Diocese of Thrace

* Europa (Seville Metro), Seville, Spain; a station on the Seville Metro

* Europa City, Paris, France; a planned development

* Europa Cliffs, Alexan ...

, one of the moons orbiting Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

, is slightly smaller than the Earth's Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It orbits around Earth at an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth's diameter). The Moon rotates, with a rotation period (lunar day) that is synchronized to its orbital period (lunar mo ...

. There is a strong possibility a large saltwater ocean exists beneath its ice surface.microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s if hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

s are active on the ocean floor.Enceladus

Enceladus is the sixth-largest moon of Saturn and the 18th-largest in the Solar System. It is about in diameter, about a tenth of that of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. It is covered by clean, freshly deposited snow hundreds of meters thick, ...

, a small icy moon of Saturn, also has what appears to be an underground ocean which actively vents warm water from the moon's surface.

Evolution

Historical development

The Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

is about 4.54 billion years old.Eoarchean

The Eoarchean ( ; also spelled Eoarchaean) is the first Era (geology), era of the Archean, Archean Eon of the geologic record. It spans 431 million years, from the end of the Hadean Eon 4031 annum, Mya to the start of the Paleoarchean Era 3600 M ...

era after a geological crust started to solidify following the earlier molten Hadean

The Hadean ( ) is the first and oldest of the four geologic eons of Earth's history, starting with the planet's formation about 4.6 billion years ago (estimated 4567.30 ± 0.16 million years ago set by the age of the oldest solid material ...

Eon. Microbial mat

A microbial mat is a multi-layered sheet or biofilm of microbial colonies, composed of mainly bacteria and/or archaea. Microbial mats grow at interfaces between different types of material, mostly on submerged or moist surfaces, but a few surviv ...

fossils

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

have been found in 3.48 billion-year-old sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

in Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

. Other early physical evidence of a biogenic substance

A biogenic substance is a product made by or of life forms. While the term originally was specific to metabolite compounds that had toxic effects on other organisms, it has developed to encompass any constituents, secretions, and metabolites of p ...

is graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

in 3.7 billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks

In geology, metasedimentary rock is a type of metamorphic rock. Such a rock was first formed through the deposition and solidification of sediment

Sediment is a solid material that is transported to a new location where it is deposited. It occu ...

discovered in Western Greenlanduniverse

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

."common ancestor

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. According to modern evolutionary biology, all living beings could be descendants of a unique ancestor commonl ...

or ancestral gene pool

The gene pool is the set of all genes, or genetic information, in any population, usually of a particular species.

Description

A large gene pool indicates extensive genetic diversity, which is associated with robust populations that can survi ...

.RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

and the assembly of simple cells. In 2016 scientists reported a set of 355 gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s from the last universal common ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the hypothesized common ancestral cell from which the three domains of life, the Bacteria, the Archaea, and the Eukarya originated. The cell had a lipid bilayer; it possessed the genetic code a ...

(LUCA) of all life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

, including microorganisms, living on Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

.horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

, this "tree of life" may be more complicated than a simple branching tree since some genes have spread independently between distantly related species.

Past species have also left records of their evolutionary history. Fossils, along with the comparative anatomy of present-day organisms, constitute the morphological, or anatomical, record.nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

s and amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s. The development of molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a branch of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the st ...

has revealed the record of evolution left in organisms' genomes: dating when species diverged through the molecular clock

The molecular clock is a figurative term for a technique that uses the mutation rate of biomolecules to deduce the time in prehistory when two or more life forms diverged. The biomolecular data used for such calculations are usually nucleot ...

produced by mutations. For example, these DNA sequence comparisons have revealed that humans and chimpanzees share 98% of their genomes and analyzing the few areas where they differ helps shed light on when the common ancestor of these species existed.

Prokaryotes inhabited the Earth from approximately 3–4 billion years ago.morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

or cellular organization occurred in these organisms over the next few billion years.endosymbiosis

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

.hydrogenosome

A hydrogenosome is a membrane-enclosed organelle found in some Anaerobic organism, anaerobic Ciliate, ciliates, Flagellate, flagellates, Fungus, fungi, and three species of Loricifera, loriciferans. Hydrogenosomes are highly variable organelles t ...

s. Another engulfment of cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

l-like organisms led to the formation of chloroplasts in algae and plants.

The history of life was that of the

The history of life was that of the unicellular

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

eukaryotes, prokaryotes and archaea until about 610 million years ago when multicellular organisms began to appear in the oceans in the Ediacaran

The Ediacaran ( ) is a geological period of the Neoproterozoic geologic era, Era that spans 96 million years from the end of the Cryogenian Period at 635 Million years ago, Mya to the beginning of the Cambrian Period at 538.8 Mya. It is the last ...

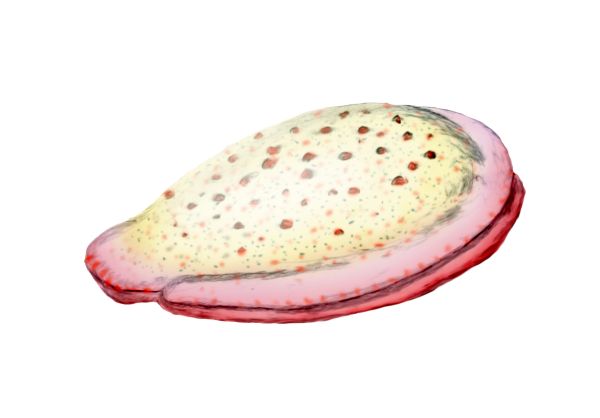

period.sponge

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and a ...

s, brown algae

Brown algae (: alga) are a large group of multicellular algae comprising the class (biology), class Phaeophyceae. They include many seaweeds located in colder waters of the Northern Hemisphere. Brown algae are the major seaweeds of the temperate ...

, cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

, slime mould

Slime mold or slime mould is an informal name given to a polyphyletic assemblage of unrelated eukaryotic organisms in the Stramenopiles, Rhizaria, Discoba, Amoebozoa and Holomycota clades. Most are near-microscopic; those in the Myxogastria ...

s and myxobacteria

The myxobacteria ("slime bacteria") are a group of bacteria that predominantly live in the soil and feed on insoluble organic substances. The myxobacteria have very large genomes relative to other bacteria, e.g. 9–10 million nucleotides except ...

. In 2016 scientists reported that, about 800 million years ago, a minor genetic change in a single molecule called GK-PID

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, unlike unicellular organisms. All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- and part ...

may have allowed organisms to go from a single cell organism to one of many cells.types

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* Ty ...

of modern animals appeared in the fossil record, as well as unique lineages that subsequently became extinct.oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

in the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

from photosynthesis.

About 500 million years ago, plants and fungi started colonizing the land. Evidence for the appearance of the first land plants

The embryophytes () are a clade of plants, also known as Embryophyta (Plantae ''sensu strictissimo'') () or land plants. They are the most familiar group of photoautotrophs that make up the vegetation on Earth's dry lands and wetlands. Embryophy ...

occurs in the Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and System (geology), system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era (geology), Era, and the second of twelve periods of the Phanerozoic Eon (geology), Eon. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years f ...

, around , in the form of fossil spores.Late Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 23.5 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the third and shortest period of t ...

, from around . The colonization of the land by plants was soon followed by arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s and other animals. Insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s were particularly successful and even today make up the majority of animal species. Amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s first appeared around 364 million years ago, followed by early amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

s and bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s around 155 million years ago (both from "reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

"-like lineages), mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s around 129 million years ago, homininae

Homininae (the hominines) is a subfamily of the family Hominidae (hominids). (The Homininae——encompass humans, and are also called "African hominids" or "African apes".) This subfamily includes two tribes, Hominini and Gorillini, both having ...

around 10 million years ago and modern humans

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are great apes characterized by their hairlessness, bipedalism, and high intelligen ...

around 250,000 years ago. However, despite the evolution of these large animals, smaller organisms similar to the types that evolved early in this process continue to be highly successful and dominate the Earth, with the majority of both biomass and species being prokaryotes.species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

range from 10 million to 14 million,

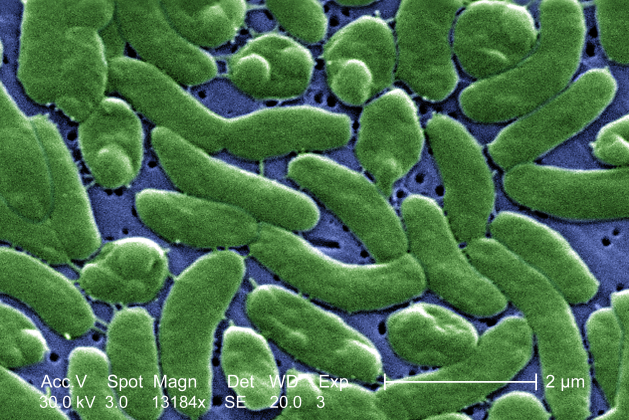

Microorganisms

Microorganisms make up about 70% of the marine biomass.microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

, or microbe, is a microscopic

The microscopic scale () is the scale of objects and events smaller than those that can easily be seen by the naked eye, requiring a lens or microscope to see them clearly. In physics, the microscopic scale is sometimes regarded as the scale betwe ...

organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

too small to be recognized with the naked eye. It can be single-celled

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell (biology), cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic ...

multicellular

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell (biology), cell, unlike unicellular organisms. All species of animals, Embryophyte, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organism ...

. Microorganisms are diverse and include all bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

and archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

, most protozoa

Protozoa (: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically ...

such as algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

, fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

, and certain microscopic animals such as rotifer

The rotifers (, from Latin 'wheel' and 'bearing'), sometimes called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic Coelom#Pseudocoelomates, pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first describ ...

s.

Many macroscopic

The macroscopic scale is the length scale on which objects or phenomena are large enough to be visible with the naked eye, without magnifying optical instruments. It is the opposite of microscopic.

Overview

When applied to physical phenome ...

animals and plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s have microscopic juvenile stages. Some microbiologists also classify virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es (and viroid

Viroids are small single-stranded, circular RNAs that are infectious pathogens. Unlike viruses, they have no protein coating. All known viroids are inhabitants of angiosperms (flowering plants), and most cause diseases, whose respective eco ...

s) as microorganisms, but others consider these as nonliving.ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

s as they act as decomposer

Decomposers are organisms that break down dead organisms and release the nutrients from the dead matter into the environment around them. Decomposition relies on chemical processes similar to digestion in animals; in fact, many sources use the word ...

s. Some microorganisms are pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

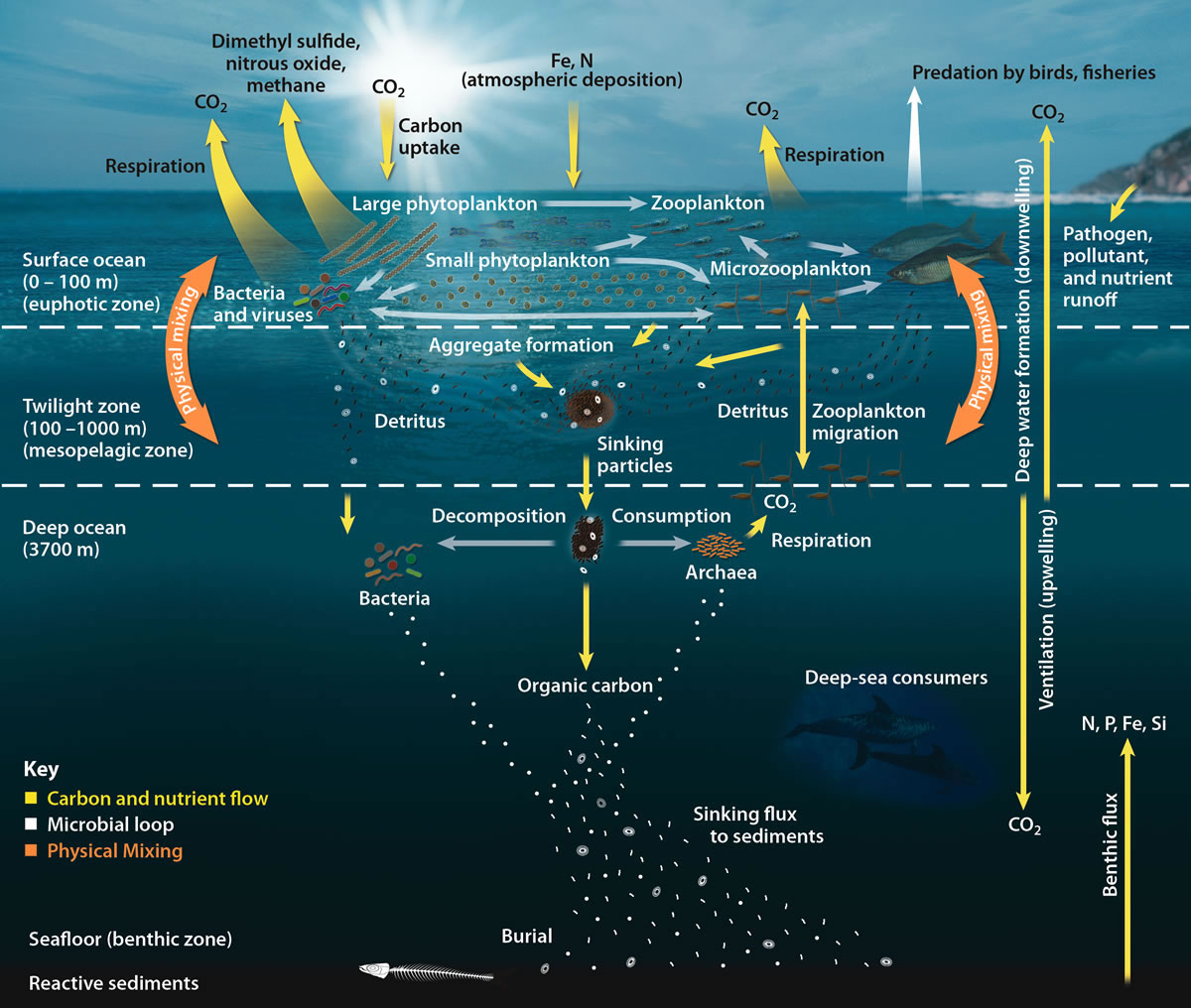

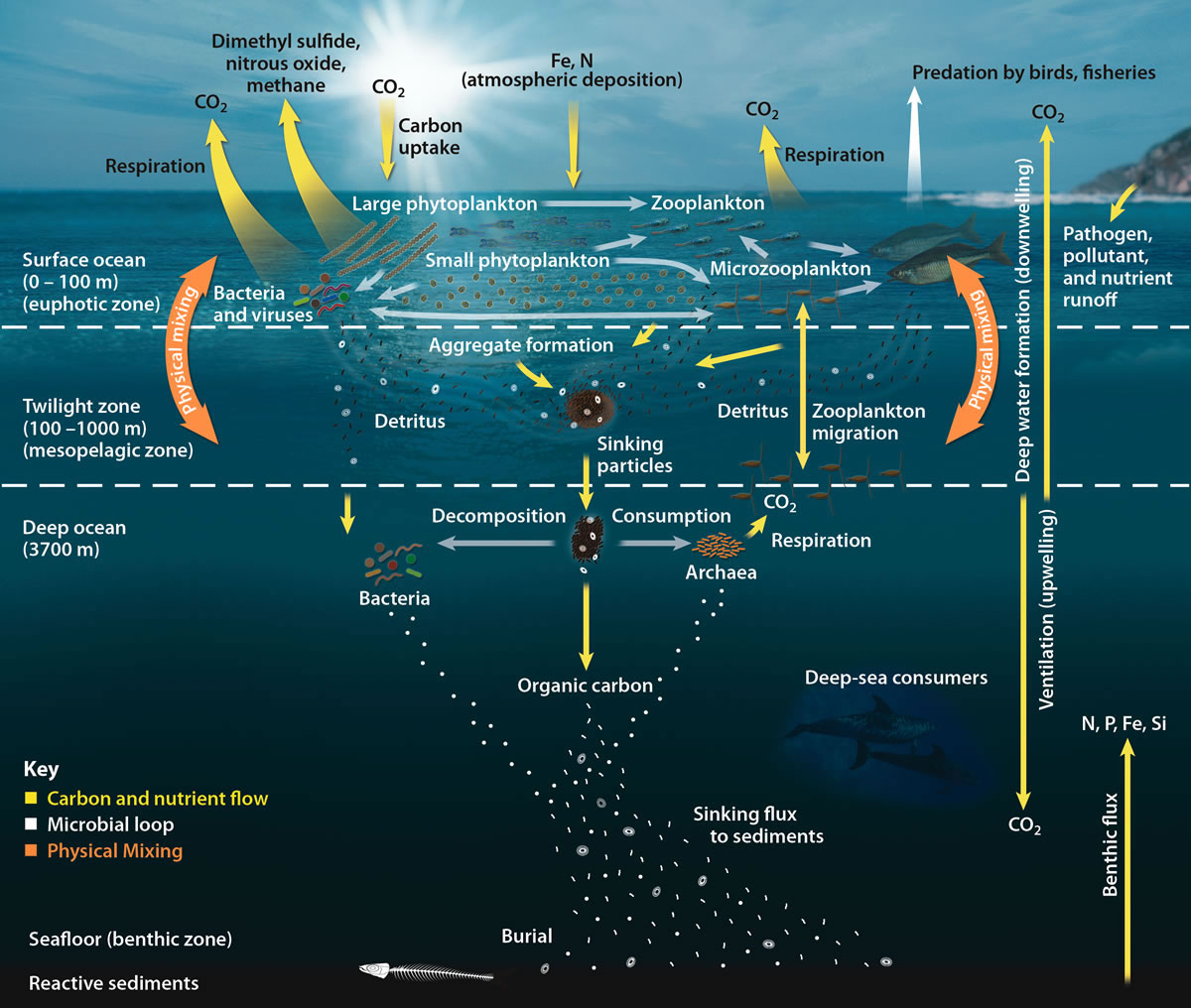

ic, causing disease and even death in plants and animals. As inhabitants of the largest environment on Earth, microbial marine systems drive changes in every global system. Microbes are responsible for virtually all the photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

that occurs in the ocean, as well as the cycling of carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

, nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

, phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol P and atomic number 15. All elemental forms of phosphorus are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive and are therefore never found in nature. They can nevertheless be prepared ar ...

, other nutrients

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excret ...

and trace elements.

Microscopic life undersea is diverse and still poorly understood, such as for the role of

Microscopic life undersea is diverse and still poorly understood, such as for the role of virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es in marine ecosystems. Most marine viruses are bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

s, which are harmless to plants and animals, but are essential to the regulation of saltwater and freshwater ecosystems.biological pump

The biological pump (or ocean carbon biological pump or marine biological carbon pump) is the ocean's biologically driven Carbon sequestration, sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere and land runoff to the ocean interior and seafloor sedim ...

, the process whereby carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

is sequestered in the deep ocean. A stream of airborne microorganisms circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes. Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in

A stream of airborne microorganisms circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes. Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in sea spray

Sea spray consists of aerosol particles formed from the ocean, primarily by ejection into Earth's atmosphere through bursting bubbles at the air-sea interface Sea spray contains both organic matter and inorganic salts that form sea salt aeroso ...

. In 2018, scientists reported that hundreds of millions of viruses and tens of millions of bacteria are deposited daily on every square meter around the planet.biosphere

The biosphere (), also called the ecosphere (), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also be termed the zone of life on the Earth. The biosphere (which is technically a spherical shell) is virtually a closed system with regard to mat ...

. The mass of prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

microorganisms — which includes bacteria and archaea, but not the nucleated eukaryote microorganisms — may be as much as 0.8 trillion tons of carbon (of the total biosphere mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

, estimated at between 1 and 4 trillion tons).Mariana Trench

The Mariana Trench is an oceanic trench located in the western Pacific Ocean, about east of the Mariana Islands; it is the deep sea, deepest oceanic trench on Earth. It is crescent-shaped and measures about in length and in width. The maxi ...

, the deepest spot in the Earth's oceans.Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

.

Marine viruses

Viruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are found in almo ...

are small infectious agent

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ.

The term ...

s that do not have their own metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

and can replicate only inside the living cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a d ...

of other organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

s.life forms

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to life forms:

A life form (also spelled life-form or lifeform) is an entity that is living, such as plants (flora), animals (fauna), and fungi ( funga). It is estimated tha ...

, from animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

s and plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s to microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s, including bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

and archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

.bacterium

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the ...

. Most viruses cannot be seen with an optical microscope

The optical microscope, also referred to as a light microscope, is a type of microscope that commonly uses visible light and a system of lenses to generate magnified images of small objects. Optical microscopes are the oldest design of micros ...

so electron microscope

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of electrons as a source of illumination. It uses electron optics that are analogous to the glass lenses of an optical light microscope to control the electron beam, for instance focusing it ...

s are used instead.

Viruses are found wherever there is life and have probably existed since living cells first evolved.molecular techniques

Molecular biology is a branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions.

Though cells and other microscop ...

have been used to compare the DNA or RNA of viruses and are a useful means of investigating how they arise.evolutionary history of life

The history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and extinct organisms evolved, from the earliest emergence of life to the present day. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as ''Ga'', for '' gigaannum'') and ...

are unclear: some may have evolved

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

from plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and ...

s—pieces of DNA that can move between cells—while others may have evolved from bacteria. In evolution, viruses are an important means of horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

, which increases genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species. It ranges widely, from the number of species to differences within species, and can be correlated to the span of survival for a species. It is d ...

. Opinions differ on whether viruses are a form of

Opinions differ on whether viruses are a form of life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

or organic structures that interact with living organisms.natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

. However they lack key characteristics such as a cellular structure generally considered necessary to count as life. Because they possess some but not all such qualities, viruses have been described as replicatorsBacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

s, often just called ''phages'', are viruses that parasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted str ...

bacteria and archaea. Marine phages parasite marine bacteria and archaea, such as cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

.Inoviridae

Filamentous bacteriophages are a family of viruses (''Inoviridae'') that infect bacteria, or bacteriophages. They are named for their filamentous shape, a worm-like chain (long, thin, and flexible, reminiscent of a length of cooked spaghetti), ...

and Microviridaealgal bloom

An algal bloom or algae bloom is a rapid increase or accumulation in the population of algae in fresh water or marine water systems. It is often recognized by the discoloration in the water from the algae's pigments. The term ''algae'' encompass ...

s,archaeal viruses

An archaeal virus is a virus that infects and replicates in archaea, a domain of unicellular, prokaryotic organisms. Archaeal viruses, like their hosts, are found worldwide, including in extreme environments inhospitable to most life such as aci ...

which replicate within archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

: these are double-stranded DNA viruses with unusual and sometimes unique shapes.thermophilic

A thermophile is a type of extremophile that thrives at relatively high temperatures, between . Many thermophiles are archaea, though some of them are bacteria and fungi. Thermophilic eubacteria are suggested to have been among the earliest bact ...

archaea, particularly the orders Sulfolobales

Sulfolobales is an order of archaeans in the class Thermoprotei.

Phylogeny

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)

...

and Thermoproteales

Thermoproteales are an order of archaeans in the class Thermoprotei. They are the only organisms known to lack the SSB proteins, instead possessing the protein ThermoDBP that has displaced them.

The rRNA genes of these organisms contain multi ...

.

Viruses are an important natural means of transferring genes between different species, which increases genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species. It ranges widely, from the number of species to differences within species, and can be correlated to the span of survival for a species. It is d ...

and drives evolution.last universal common ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the hypothesized common ancestral cell from which the three domains of life, the Bacteria, the Archaea, and the Eukarya originated. The cell had a lipid bilayer; it possessed the genetic code a ...

of life on Earth.

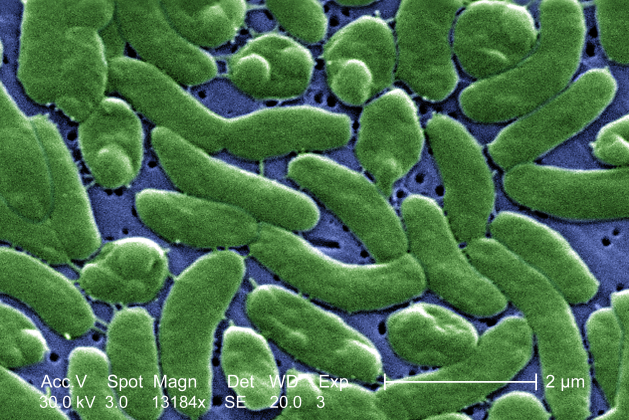

Marine bacteria

Bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

constitute a large domain

A domain is a geographic area controlled by a single person or organization. Domain may also refer to:

Law and human geography

* Demesne, in English common law and other Medieval European contexts, lands directly managed by their holder rather ...

of prokaryotic

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' ...

microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s. Typically a few micrometers in length, bacteria have a number of shapes, ranging from spheres to rods and spirals. Bacteria were among the first life forms to appear on Earth