Saffron Scourge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Yellow fever is a

Yellow fever virus is mainly transmitted through the bite of the yellow fever mosquito ''Aedes aegypti'', but other mostly ''

Yellow fever virus is mainly transmitted through the bite of the yellow fever mosquito ''Aedes aegypti'', but other mostly ''

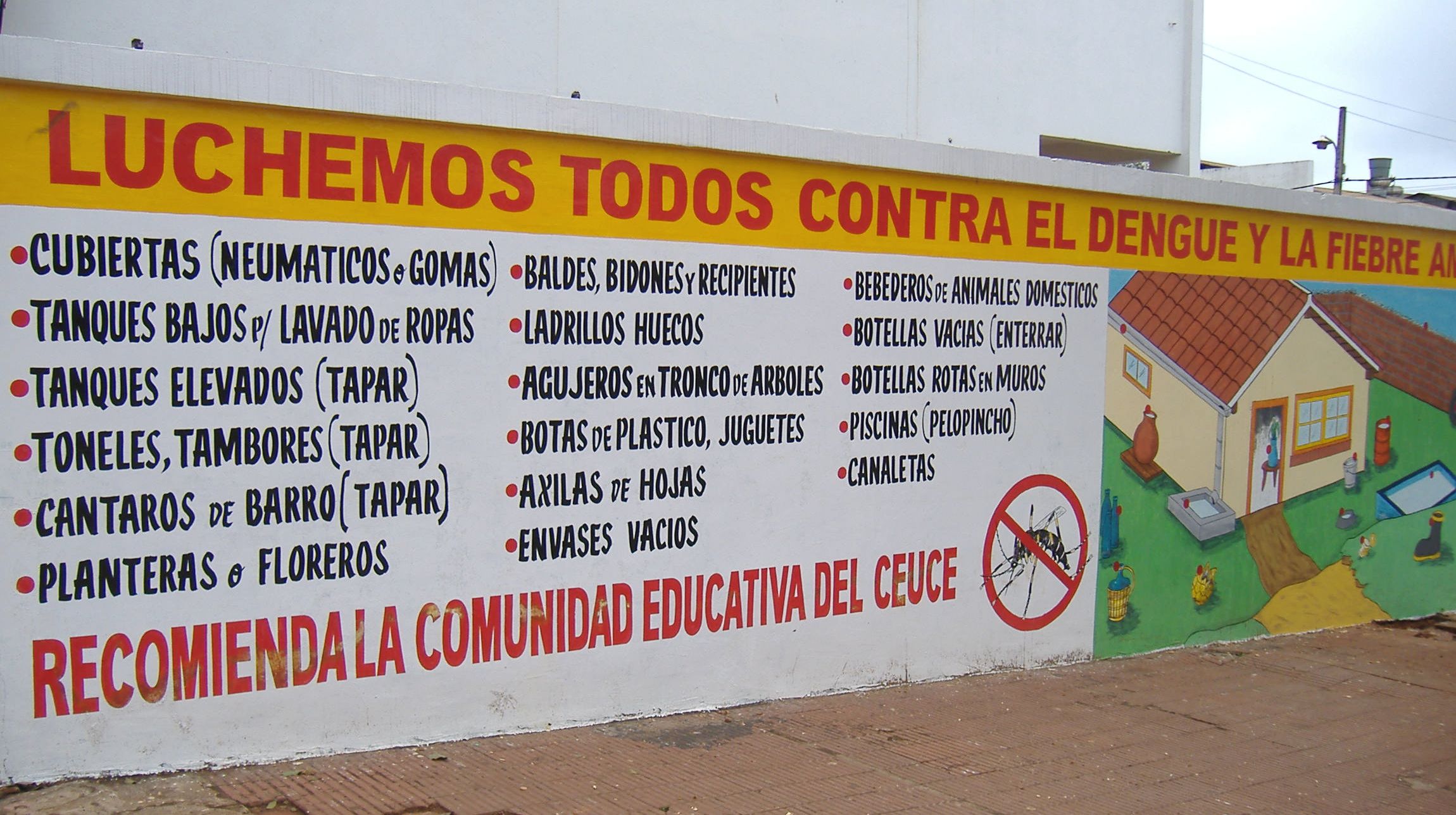

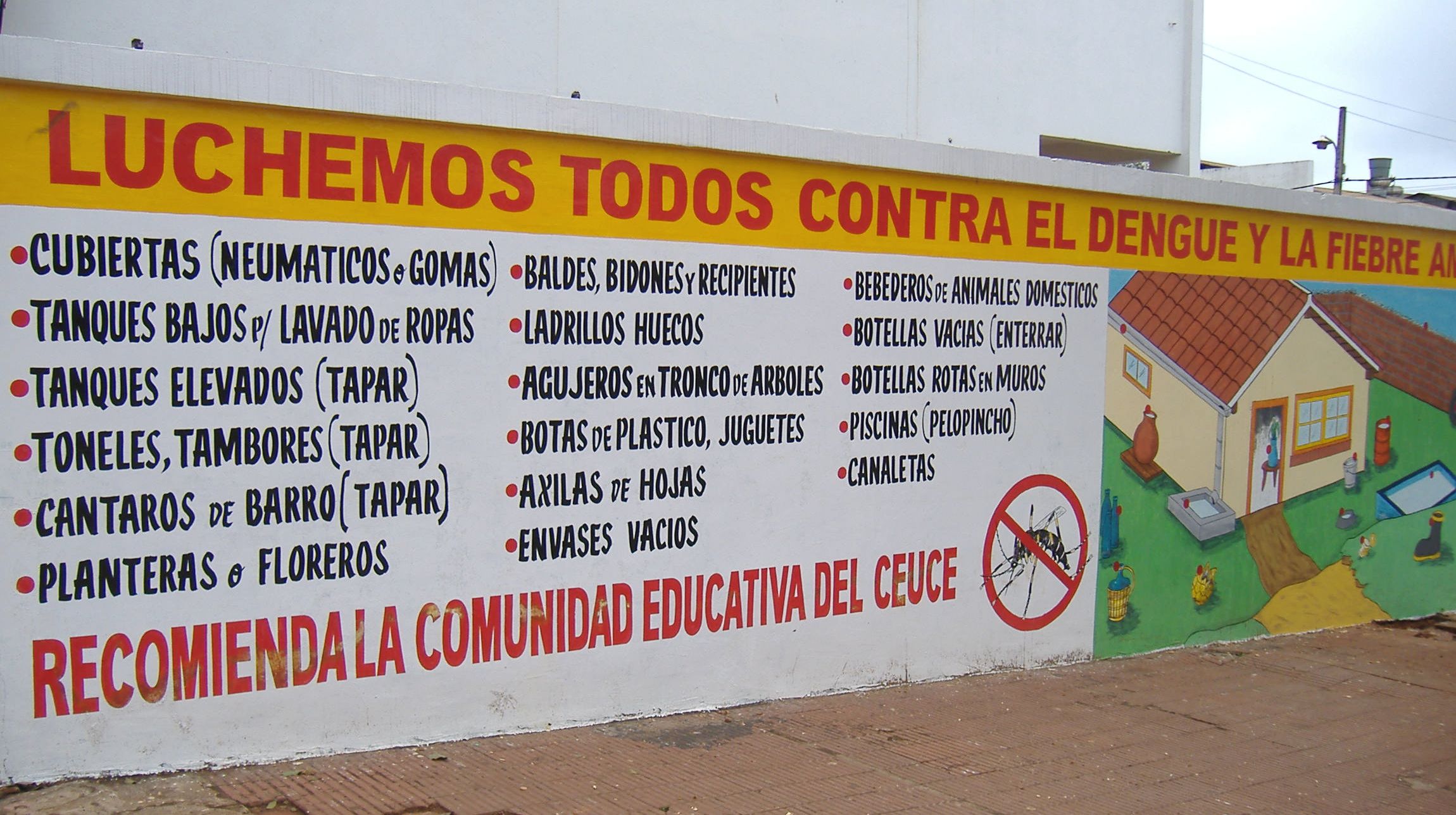

Control of the yellow fever mosquito ''A. aegypti'' is of major importance, especially because the same mosquito can also transmit dengue fever and

Control of the yellow fever mosquito ''A. aegypti'' is of major importance, especially because the same mosquito can also transmit dengue fever and

An estimated 90% of yellow fever infections occur on the African continent. In 2016, a large outbreak originated in Angola and spread to neighboring countries before being contained by a massive vaccination campaign. In March and April 2016, 11 imported cases of the Angola genotype in unvaccinated Chinese nationals were reported in China, the first appearance of the disease in Asia in recorded history.

An estimated 90% of yellow fever infections occur on the African continent. In 2016, a large outbreak originated in Angola and spread to neighboring countries before being contained by a massive vaccination campaign. In March and April 2016, 11 imported cases of the Angola genotype in unvaccinated Chinese nationals were reported in China, the first appearance of the disease in Asia in recorded history.

In South America, two genotypes have been identified (South American genotypes I and II). Based on phylogenetic analysis these two genotypes appear to have originated in West Africa and were first introduced into Brazil. The date of introduction of the predecessor African genotype which gave rise to the South American genotypes appears to be 1822 (95% confidence interval 1701 to 1911). The historical record shows an outbreak of yellow fever occurred in Recife, Brazil, between 1685 and 1690. The disease seems to have disappeared, with the next outbreak occurring in 1849. It was likely introduced with the trafficking of slaves through the

In South America, two genotypes have been identified (South American genotypes I and II). Based on phylogenetic analysis these two genotypes appear to have originated in West Africa and were first introduced into Brazil. The date of introduction of the predecessor African genotype which gave rise to the South American genotypes appears to be 1822 (95% confidence interval 1701 to 1911). The historical record shows an outbreak of yellow fever occurred in Recife, Brazil, between 1685 and 1690. The disease seems to have disappeared, with the next outbreak occurring in 1849. It was likely introduced with the trafficking of slaves through the

(Mitchell's account of the Yellow Fever in Virginia in 1741–2)

, ''The Philadelphia Medical Museum,'' 1 (1) : 1–20. * (John Mitchell) (1814

"Account of the Yellow fever which prevailed in Virginia in the years 1737, 1741, and 1742, in a letter to the late Cadwallader Colden, Esq. of New York, from the late John Mitchell, M.D.F.R.S. of Virginia,"

''American Medical and Philosophical Register'', 4 : 181–215. The term "yellow fever" appears on p. 186. On p. 188, Mitchell mentions "… the distemper was what is generally called yellow fever in America". However, on pages 191–192, he states "… I shall consider the cause of the yellowness which is so remarkable in this distemper, as to have given it the name of the Yellow Fever." However, Dr. Mitchell misdiagnosed the disease that he observed and treated, and the disease was probably Weil's disease or hepatitis. McNeill argues that the environmental and ecological disruption caused by the introduction of In

In  The southern city of

The southern city of

viral

Viral means "relating to viruses" (small infectious agents).

Viral may also refer to:

Viral behavior, or virality

Memetic behavior likened that of a virus, for example:

* Viral marketing, the use of existing social networks to spread a marke ...

disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a temperature above the normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature set point. There is not a single agreed-upon upper limit for normal temperature with sources using val ...

, chills

Chills is a feeling of coldness occurring during a high fever, but sometimes is also a common symptom which occurs alone in specific people. It occurs during fever due to the release of cytokines and prostaglandins as part of the inflammatory ...

, loss of appetite

Anorexia is a medical term for a loss of appetite. While the term in non-scientific publications is often used interchangeably with anorexia nervosa, many possible causes exist for a loss of appetite, some of which may be harmless, while others i ...

, nausea

Nausea is a diffuse sensation of unease and discomfort, sometimes perceived as an urge to vomit. While not painful, it can be a debilitating symptom if prolonged and has been described as placing discomfort on the chest, abdomen, or back of the ...

, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headache

Headache is the symptom of pain in the face, head, or neck. It can occur as a migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. There is an increased risk of depression in those with severe headaches.

Headaches can occur as a resul ...

s. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In about 15% of people, within a day of improving the fever comes back, abdominal pain occurs, and liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it ...

damage begins causing yellow skin

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving abnormal heme me ...

. If this occurs, the risk of bleeding and kidney problems

Kidney failure, also known as end-stage kidney disease, is a medical condition in which the kidneys can no longer adequately filter waste products from the blood, functioning at less than 15% of normal levels. Kidney failure is classified as eit ...

is increased.

The disease is caused by the yellow fever virus and is spread by the bite of an infected mosquito

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning "gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "lit ...

. It infects humans, other primate

Primates are a diverse order (biology), order of mammals. They are divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include the Tarsiiformes, tarsiers and ...

s, and several types of mosquitoes. In cities, it is spread primarily by ''Aedes aegypti

''Aedes aegypti'', the yellow fever mosquito, is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by black and white markings on its l ...

'', a type of mosquito found throughout the tropics

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred ...

and subtropics. The virus is an RNA virus

An RNA virus is a virusother than a retrovirusthat has ribonucleic acid (RNA) as its genetic material. The nucleic acid is usually single-stranded RNA ( ssRNA) but it may be double-stranded (dsRNA). Notable human diseases caused by RNA viruse ...

of the genus ''Flavivirus

''Flavivirus'' is a genus of positive-strand RNA viruses in the family '' Flaviviridae''. The genus includes the West Nile virus, dengue virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, yellow fever virus, Zika virus and several other viruses which ma ...

''. The disease may be difficult to tell apart from other illnesses, especially in the early stages. To confirm a suspected case, blood-sample testing with polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) ...

is required.

A safe and effective vaccine against yellow fever exists, and some countries require vaccinations for travelers. Other efforts to prevent infection include reducing the population of the transmitting mosquitoes. In areas where yellow fever is common, early diagnosis of cases and immunization of large parts of the population are important to prevent outbreak

In epidemiology, an outbreak is a sudden increase in occurrences of a disease when cases are in excess of normal expectancy for the location or season. It may affect a small and localized group or impact upon thousands of people across an entire ...

s. Once a person is infected, management is symptomatic; no specific measures are effective against the virus. Death occurs in up to half of those who get severe disease.

In 2013, yellow fever resulted in about 127,050 severe infections and 45,000 deaths worldwide, with nearly 90 percent of these occurring in Africa. Nearly a billion people live in an area of the world where the disease is common. It is common in tropical areas of the continents of South America and Africa, but not in Asia. Since the 1980s, the number of cases of yellow fever has been increasing. This is believed to be due to fewer people being immune, more people living in cities, people moving frequently, and changing climate increasing the habitat for mosquitoes.

The disease originated in Africa and spread to the Americas starting in the 17th century with the European trafficking of enslaved Africans

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

from sub-Saharan Africa. Since the 17th century, several major outbreaks

In epidemiology, an outbreak is a sudden increase in occurrences of a disease when cases are in excess of normal expectancy for the location or season. It may affect a small and localized group or impact upon thousands of people across an entire ...

of the disease have occurred in the Americas, Africa, and Europe. In the 18th and 19th centuries, yellow fever was considered one of the most dangerous infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable d ...

s; numerous epidemics swept through major cities of the US and in other parts of the world.

In 1927, yellow fever virus was the first human virus to be isolated.

Signs and symptoms

Yellow fever begins after an incubation period of three to six days. Most cases cause only a mild infection with fever, headache, chills, back pain, fatigue, loss of appetite, muscle pain, nausea, and vomiting. In these cases, the infection lasts only three to six days. But in 15% of cases, people enter a second, toxic phase of the disease characterized by recurring fever, this time accompanied byjaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving abnormal heme met ...

due to liver damage

Liver disease, or hepatic disease, is any of many diseases of the liver. If long-lasting it is termed chronic liver disease. Although the diseases differ in detail, liver diseases often have features in common.

Signs and symptoms

Some of the sig ...

, as well as abdominal pain

Abdominal pain, also known as a stomach ache, is a symptom associated with both non-serious and serious medical issues.

Common causes of pain in the abdomen include gastroenteritis and irritable bowel syndrome. About 15% of people have a m ...

. Bleeding in the mouth, nose, the eyes, and the gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans a ...

cause vomit containing blood, hence the Spanish name for yellow fever, ("black vomit"). There may also be kidney failure, hiccups, and delirium.

Among those who develop jaundice, the fatality rate is 20 to 50%, while the overall fatality rate

In epidemiology, case fatality rate (CFR) – or sometimes more accurately case-fatality risk – is the proportion of people diagnosed with a certain disease, who end up dying of it. Unlike a disease's mortality rate, the CFR does not take into ...

is about 3 to 7.5%. Severe cases may have a mortality greater than 50%.

Surviving the infection provides lifelong immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

, and normally results in no permanent organ damage.

Complication

Yellow fever can lead to death for 20% to 50% of those who develop severe disease. Jaundice, fatigue, heart rhythm problems, seizures and internal bleeding may also appear as complications of yellow fever during recovery time.Cause

Yellow fever is caused by yellow fever virus, an envelopedRNA virus

An RNA virus is a virusother than a retrovirusthat has ribonucleic acid (RNA) as its genetic material. The nucleic acid is usually single-stranded RNA ( ssRNA) but it may be double-stranded (dsRNA). Notable human diseases caused by RNA viruse ...

40–50 in width, the type species and namesake of the family ''Flaviviridae

''Flaviviridae'' is a family of enveloped positive-strand RNA viruses which mainly infect mammals and birds. They are primarily spread through arthropod vectors (mainly ticks and mosquitoes). The family gets its name from the yellow fever viru ...

''. It was the first illness shown to be transmissible by filtered human serum and transmitted by mosquitoes, by American doctor Walter Reed

Walter Reed (September 13, 1851 – November 22, 1902) was a U.S. Army physician who in 1901 led the team that confirmed the theory of Cuban doctor Carlos Finlay that yellow fever is transmitted by a particular mosquito species rather than ...

around 1900. The positive-sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the central nervous system rec ...

, single-stranded RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

is around 10,862 nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecul ...

s long and has a single open reading frame

In molecular biology, open reading frames (ORFs) are defined as spans of DNA sequence between the start and stop codons. Usually, this is considered within a studied region of a Prokaryote, prokaryotic DNA sequence, where only one of the #Six-fra ...

encoding a polyprotein

Proteolysis is the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptides or amino acids. Uncatalysed, the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is extremely slow, taking hundreds of years. Proteolysis is typically catalysed by cellular enzymes called proteas ...

.Host

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

*Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

People

* Jim Host (born 1937), American businessman

* Michel Host ...

protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the form ...

s cut this polyprotein into three structural (C, prM, E) and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5); the enumeration corresponds to the arrangement of the protein coding gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s in the genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ...

. Minimal ''yellow fever virus'' (YFV) 3'UTR region is required for stalling of the host 5'-3' exonuclease XRN1. The UTR contains PKS3 pseudoknot structure, which serves as a molecular signal to stall the exonuclease and is the only viral requirement for subgenomic flavivirus RNA (sfRNA) production. The sfRNAs are a result of incomplete degradation of the viral genome by the exonuclease and are important for viral pathogenicity. Yellow fever belongs to the group of hemorrhagic fevers

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra ...

.

The viruses infect, amongst others, monocyte

Monocytes are a type of leukocyte or white blood cell. They are the largest type of leukocyte in blood and can differentiate into macrophages and conventional dendritic cells. As a part of the vertebrate innate immune system monocytes also i ...

s, macrophages, Schwann cells

Schwann cells or neurolemmocytes (named after German physiologist Theodor Schwann) are the principal glia of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Glial cells function to support neurons and in the PNS, also include satellite cells, olfactory en ...

, and dendritic cell

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells (also known as ''accessory cells'') of the mammalian immune system. Their main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system. ...

s. They attach to the cell surfaces via specific receptors

Receptor may refer to:

*Sensory receptor, in physiology, any structure which, on receiving environmental stimuli, produces an informative nerve impulse

*Receptor (biochemistry), in biochemistry, a protein molecule that receives and responds to a n ...

and are taken up by an endosomal vesicle

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

; In human embryology

* Vesicle (embryology), bulge-like features ...

. Inside the endosome

Endosomes are a collection of intracellular sorting organelles in eukaryotic cells. They are parts of endocytic membrane transport pathway originating from the trans Golgi network. Molecules or ligands internalized from the plasma membrane c ...

, the decreased pH induces the fusion of the endosomal membrane with the virus envelope

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes.

Numerous human pathogenic viruses in circulation are encase ...

. The capsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may ...

enters the cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells ( intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

, decays, and releases the genome. Receptor binding, as well as membrane fusion, are catalyzed

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycl ...

by the protein E, which changes its conformation at low pH, causing a rearrangement of the 90 homodimer

Dimer may refer to:

* Dimer (chemistry), a chemical structure formed from two similar sub-units

** Protein dimer, a protein quaternary structure

** d-dimer

* Dimer model, an item in statistical mechanics, based on ''domino tiling''

* Julius Dimer ( ...

s to 60 homo trimers.

After entering the host cell, the viral genome is replicated in the rough endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

(ER) and in the so-called vesicle packets. At first, an immature form of the virus particle is produced inside the ER, whose M-protein is not yet cleaved to its mature form, so is denoted as precursor M (prM) and forms a complex with protein E. The immature particles are processed in the Golgi apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (), also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply the Golgi, is an organelle found in most eukaryotic cells. Part of the endomembrane system in the cytoplasm, it packages proteins into membrane-bound vesicles ...

by the host protein furin

Furin is a protease, a proteolytic enzyme that in humans and other animals is encoded by the ''FURIN'' gene. Some proteins are inactive when they are first synthesized, and must have sections removed in order to become active. Furin cleaves these s ...

, which cleaves prM to M. This releases E from the complex, which can now take its place in the mature, infectious virion

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky ...

.

Transmission

Yellow fever virus is mainly transmitted through the bite of the yellow fever mosquito ''Aedes aegypti'', but other mostly ''

Yellow fever virus is mainly transmitted through the bite of the yellow fever mosquito ''Aedes aegypti'', but other mostly ''Aedes

''Aedes'' is a genus of mosquitoes originally found in tropical and subtropical zones, but now found on all continents except perhaps Antarctica. Some species have been spread by human activity: ''Aedes albopictus'', a particularly invasive spe ...

'' mosquitoes such as the tiger mosquito (''Aedes albopictus

''Aedes albopictus'' (''Stegomyia albopicta''), from the mosquito (Culicidae) family, also known as the (Asian) tiger mosquito or forest mosquito, is a mosquito native to the tropical and subtropical areas of Southeast Asia. In the past few ce ...

'') can also serve as a vector

Vector most often refers to:

*Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

*Vector (epidemiology), an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematic ...

for this virus. Like other arbovirus

Arbovirus is an informal name for any virus that is transmitted by arthropod vectors. The term ''arbovirus'' is a portmanteau word (''ar''thropod-''bo''rne ''virus''). ''Tibovirus'' (''ti''ck-''bo''rne ''virus'') is sometimes used to more spe ...

es, which are transmitted by mosquitoes, ''yellow fever virus'' is taken up by a female mosquito when it ingests the blood of an infected human or another primate. Viruses reach the stomach of the mosquito, and if the virus concentration is high enough, the virions can infect epithelial cell

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. It is a thin, continuous, protective layer of compactly packed cells with a little intercell ...

s and replicate there. From there, they reach the haemocoel

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

(the blood system of mosquitoes) and from there the salivary gland

The salivary glands in mammals are exocrine glands that produce saliva through a system of ducts. Humans have three paired major salivary glands ( parotid, submandibular, and sublingual), as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands. Salivar ...

s. When the mosquito next sucks blood, it injects its saliva into the wound, and the virus reaches the bloodstream of the bitten person. Transovarial transmissionial and transstadial transmission

Transstadial transmission occurs when a pathogen remains with the vector from one life stage ("stadium") to the next. For example, the bacteria ''Borrelia burgdorferi'', the causative agent for Lyme disease, infects the tick vector as a larva, and ...

of yellow fever virus within ''A. aegypti'', that is, the transmission from a female mosquito to its eggs and then larvae, are indicated. This infection of vectors without a previous blood meal seems to play a role in single, sudden breakouts of the disease.

Three epidemiologically different infectious cycles occur in which the virus is transmitted from mosquitoes to humans or other primates. In the "urban cycle", only the yellow fever mosquito ''A. aegypti'' is involved. It is well adapted to urban areas, and can also transmit other diseases, including Zika fever

Zika fever, also known as Zika virus disease or simply Zika, is an infectious disease caused by the Zika virus. Most cases have no symptoms, but when present they are usually mild and can resemble dengue fever. Symptoms may include fever, red ...

, dengue fever

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by the dengue virus. Symptoms typically begin three to fourteen days after infection. These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic ...

, and chikungunya

Chikungunya is an infection caused by the ''Chikungunya virus'' (CHIKV). Symptoms include fever and joint pains. These typically occur two to twelve days after exposure. Other symptoms may include headache, muscle pain, joint swelling, and a ras ...

. The urban cycle is responsible for the major outbreaks of yellow fever that occur in Africa. Except for an outbreak in Bolivia in 1999, this urban cycle no longer exists in South America.

Besides the urban cycle, both in Africa and South America, a sylvatic cycle

The sylvatic cycle, also enzootic or sylvatic transmission cycle, is a portion of the natural transmission cycle of a pathogen. Sylvatic refers to the occurrence of a subject in or affecting wild animals. The sylvatic cycle is the fraction of the p ...

(forest or jungle cycle) is present, where ''Aedes africanus

''Aedes africanus'' is a species of mosquito that is found on the continent of Africa with the exclusion of Madagascar.Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit, Systematic Catalog of Culicidae, ''Aedes aegypti'' and ''Aedes africanus'' are the two main y ...

'' (in Africa) or mosquitoes of the genus ''Haemagogus

''Haemagogus'' is a genus of mosquitoes in the dipteran family Culicidae. They mainly occur in Central America and northern South America (including Trinidad), although some species inhabit forested areas of Brazil, and range as far as northern A ...

'' and ''Sabethes

''Sabethes'' mosquitoes are primarily an arboreal genus, breeding in plant cavities.Ralph E. Harbach. 1994. The subgenus ''Sabethinus'' of ''Sabethes'' (Diptera: Culicidae). ''Systematic Entomology'', 19: 207-234; https://www.researchgate.net/p ...

'' (in South America) serve as vectors. In the jungle, the mosquitoes infect mainly nonhuman primates; the disease is mostly asymptomatic in African primates. In South America, the sylvatic cycle is currently the only way humans can become infected, which explains the low incidence of yellow fever cases on the continent. People who become infected in the jungle can carry the virus to urban areas, where ''A. aegypti'' acts as a vector. Because of this sylvatic cycle, yellow fever cannot be eradicated except by eradicating the mosquitoes that serve as vectors.

In Africa, a third infectious cycle known as "savannah cycle" or intermediate cycle, occurs between the jungle and urban cycles. Different mosquitoes of the genus ''Aedes'' are involved. In recent years, this has been the most common form of transmission of yellow fever in Africa.

Concern exists about yellow fever spreading to southeast Asia, where its vector ''A. aegypti'' already occurs.

Pathogenesis

After transmission from a mosquito, the viruses replicate in thelymph node

A lymph node, or lymph gland, is a kidney-shaped organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphocytes that inc ...

s and infect dendritic cell

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells (also known as ''accessory cells'') of the mammalian immune system. Their main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system. ...

s in particular. From there, they reach the liver and infect hepatocyte

A hepatocyte is a cell of the main parenchymal tissue of the liver. Hepatocytes make up 80% of the liver's mass.

These cells are involved in:

* Protein synthesis

* Protein storage

* Transformation of carbohydrates

* Synthesis of cholesterol, ...

s (probably indirectly via Kupffer cell

Kupffer cells, also known as stellate macrophages and Kupffer–Browicz cells, are specialized cells localized in the liver within the lumen of the liver sinusoids and are adhesive to their endothelial cells which make up the blood vessel walls. Ku ...

s), which leads to eosinophilic degradation of these cells and to the release of cytokine

Cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling. Cytokines are peptides and cannot cross the lipid bilayer of cells to enter the cytoplasm. Cytokines have been shown to be involved in a ...

s. Apoptotic masses known as Councilman bodies appear in the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. ...

of hepatocytes.

Fatality may occur when cytokine storm

A cytokine storm, also called hypercytokinemia, is a physiological reaction in humans and other animals in which the innate immune system causes an uncontrolled and excessive release of pro-inflammatory signaling molecules called cytokines. Norm ...

, shock

Shock may refer to:

Common uses Collective noun

*Shock, a historic commercial term for a group of 60, see English numerals#Special names

* Stook, or shock of grain, stacked sheaves

Healthcare

* Shock (circulatory), circulatory medical emerge ...

, and multiple organ failure

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) is altered organ function in an acutely ill patient requiring medical intervention to achieve homeostasis.

Although Irwin and Rippe cautioned in 2005 that the use of "multiple organ failure" or "multis ...

follow.

Diagnosis

Yellow fever is most frequently a clinicaldiagnosis

Diagnosis is the identification of the nature and cause of a certain phenomenon. Diagnosis is used in many different disciplines, with variations in the use of logic, analytics, and experience, to determine " cause and effect". In systems engin ...

, based on symptomatology

Signs and symptoms are the observed or detectable signs, and experienced symptoms of an illness, injury, or condition. A sign for example may be a higher or lower temperature than normal, raised or lowered blood pressure or an abnormality showin ...

and travel history. Mild cases of the disease can only be confirmed virologically. Since mild cases of yellow fever can also contribute significantly to regional outbreaks, every suspected case of yellow fever (involving symptoms of fever, pain, nausea, and vomiting 6–10 days after leaving the affected area) is treated seriously.

If yellow fever is suspected, the virus cannot be confirmed until 6–10 days following the illness. A direct confirmation can be obtained by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is a laboratory technique combining reverse transcription of RNA into DNA (in this context called complementary DNA or cDNA) and amplification of specific DNA targets using polymerase chai ...

, where the genome of the virus is amplified. Another direct approach is the isolation of the virus and its growth in cell culture using blood plasma

Blood plasma is a light amber-colored liquid component of blood in which blood cells are absent, but contains proteins and other constituents of whole blood in suspension. It makes up about 55% of the body's total blood volume. It is the ...

; this can take 1–4 weeks.

Serologically, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay uses a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence ...

during the acute phase of the disease using specific IgM

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) is one of several isotypes of antibody (also known as immunoglobulin) that are produced by vertebrates. IgM is the largest antibody, and it is the first antibody to appear in the response to initial exposure to an antige ...

against yellow fever or an increase in specific IgG titer

Titer (American English) or titre (British English) is a way of expressing concentration. Titer testing employs serial dilution to obtain approximate quantitative information from an analytical procedure that inherently only evaluates as posit ...

(compared to an earlier sample) can confirm yellow fever. Together with clinical symptoms, the detection of IgM or a four-fold increase in IgG titer is considered sufficient indication for yellow fever. As these tests can cross-react with other flaviviruses, such as dengue virus

''Dengue virus'' (DENV) is the cause of dengue fever. It is a mosquito-borne, single positive-stranded RNA virus of the family ''Flaviviridae''; genus ''Flavivirus''. Four serotypes of the virus have been found, a reported fifth has yet to be c ...

, these indirect methods cannot conclusively prove yellow fever infection.

Liver biopsy

A biopsy is a medical test commonly performed by a surgeon, interventional radiologist, or an interventional cardiologist. The process involves extraction of sample cells or tissues for examination to determine the presence or extent of a d ...

can verify inflammation

Inflammation (from la, wikt:en:inflammatio#Latin, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or Irritation, irritants, and is a protective response involving im ...

and necrosis

Necrosis () is a form of cell injury which results in the premature death of cells in living tissue by autolysis. Necrosis is caused by factors external to the cell or tissue, such as infection, or trauma which result in the unregulated dig ...

of hepatocytes and detect viral antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

s. Because of the bleeding tendency of yellow fever patients, a biopsy is only advisable ''post mortem'' to confirm the cause of death.

In a differential diagnosis, infections with yellow fever must be distinguished from other feverish illnesses such as malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or deat ...

. Other viral hemorrhagic fever

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of animal and human illnesses in which fever and hemorrhage are caused by a viral infection. VHFs may be caused by five distinct families of RNA viruses: the families ''Filoviridae'', ''Flavi ...

s, such as Ebola virus

''Zaire ebolavirus'', more commonly known as Ebola virus (; EBOV), is one of six known species within the genus '' Ebolavirus''. Four of the six known ebolaviruses, including EBOV, cause a severe and often fatal hemorrhagic fever in humans and o ...

, Lassa virus

''Lassa mammarenavirus'' (LASV) is an arenavirus that causes Lassa hemorrhagic fever,

a type of viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF), in humans and other primates. ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' is an emerging virus and a select agent, requiring Biosafety ...

, Marburg virus

Marburg virus (MARV) is a hemorrhagic fever virus of the '' Filoviridae'' family of viruses and a member of the species ''Marburg marburgvirus'', genus ''Marburgvirus''. It causes Marburg virus disease in primates, a form of viral hemorrhagic ...

, and Junin virus

''Argentinian mammarenavirus'', better known as the ''Junin virus'' or ''Junín virus'' (JUNV), is an arenavirus in the '' Mammarenavirus'' genus that causes Argentine hemorrhagic fever (AHF). The virus took its original name from the city of J ...

, must be excluded as the cause.

Prevention

Personal prevention of yellow fever includes vaccination and avoidance of mosquito bites in areas where yellow fever is endemic. Institutional measures for prevention of yellow fever include vaccination programmes and measures to control mosquitoes. Programmes for distribution of mosquito nets for use in homes produce reductions in cases of both malaria and yellow fever. Use of EPA-registered insect repellent is recommended when outdoors. Exposure for even a short time is enough for a potential mosquito bite. Long-sleeved clothing, long pants, and socks are useful for prevention. The application of larvicides to water-storage containers can help eliminate potential mosquito breeding sites. EPA-registered insecticide spray decreases the transmission of yellow fever. * Use insect repellent when outdoors such as those containingDEET

''N'',''N''-Diethyl-''meta''-toluamide, also called DEET () or diethyltoluamide, is the most common active ingredient in insect repellents. It is a slightly yellow oil intended to be applied to the skin or to clothing and provides protection ag ...

, picaridin

Icaridin, also known as picaridin, is an insect repellent which can be used directly on skin or clothing. It has broad efficacy against various arthropods such as mosquitos, ticks, gnats, flies and fleas, and is almost colorless and odorless. A s ...

, ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate

Ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate (trade name IR3535) is an insect repellent which is applied topically to prevent bites and stings from mosquitos, ticks, and other insects. It is a colorless and almost odorless oil, has efficacy against a broad ran ...

(IR3535), or oil of lemon eucalyptus

''p''-Menthane-3,8-diol, also known as ''para''-menthane-3,8-diol, PMD, or menthoglycol, is an organic compound classified as a diol and a terpenoid. It is colorless. Its name reflects the hydrocarbon backbone, which is that of ''p''-menthane ...

on exposed skin.

* Mosquitoes may bite through thin clothing, so spraying clothes with repellent containing permethrin

Permethrin is a medication and an insecticide. As a medication, it is used to treat scabies and lice. It is applied to the skin as a cream or lotion. As an insecticide, it can be sprayed onto clothing or mosquito nets to kill the insects tha ...

or another EPA-registered repellent gives extra protection. Clothing treated with permethrin is commercially available. Mosquito repellents containing permethrin are not approved for application directly to the skin.

* The peak biting times for many mosquito species are dusk to dawn. However, ''A. aegypti'', one of the mosquitoes that transmits yellow fever virus, feeds during the daytime. Staying in accommodations with screened or air-conditioned rooms, particularly during peak biting times, also reduces the risk of mosquito bites.

Vaccination

Vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

is recommended for those traveling to affected areas, because non-native people tend to develop more severe illness when infected. Protection begins by the 10th day after vaccine administration in 95% of people, and had been reported to last for at least 10 years. The World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level o ...

(WHO) now states that a single dose of vaccine is sufficient to confer lifelong immunity against yellow fever disease. The attenuated live vaccine stem 17D was developed in 1937 by Max Theiler

Max Theiler (30 January 1899 – 11 August 1972) was a South African-American virologist and physician. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1951 for developing a vaccine against yellow fever in 1937, becoming the firs ...

. The WHO recommends routine vaccination for people living in affected areas between the 9th and 12th month after birth.

Up to one in four people experience fever, aches, and local soreness and redness at the site of injection. In rare cases (less than one in 200,000 to 300,000), the vaccination can cause yellow fever vaccine-associated viscerotropic disease, which is fatal in 60% of cases. It is probably due to the genetic morphology of the immune system. Another possible side effect is an infection of the nervous system, which occurs in one in 200,000 to 300,000 cases, causing yellow fever vaccine-associated neurotropic disease, which can lead to meningoencephalitis

Meningoencephalitis (; from ; ; and the medical suffix ''-itis'', "inflammation"), also known as herpes meningoencephalitis, is a medical condition that simultaneously resembles both meningitis, which is an infection or inflammation of the meni ...

and is fatal in less than 5% of cases.

The Yellow Fever Initiative, launched by the WHO in 2006, vaccinated more than 105 million people in 14 countries in West Africa. No outbreaks were reported during 2015. The campaign was supported by the GAVI

GAVI, officially Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (previously the GAVI Alliance, and before that the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization) is a public–private global health partnership with the goal of increasing access to immunization ...

alliance and governmental organizations in Europe and Africa. According to the WHO, mass vaccination cannot eliminate yellow fever because of the vast number of infected mosquitoes in urban areas of the target countries, but it will significantly reduce the number of people infected.

Demand for yellow fever vaccine has continued to increase due to the growing number of countries implementing yellow fever vaccination as part of their routine immunization programmes. Recent upsurges in yellow fever outbreaks in Angola (2015), the Democratic Republic of Congo (2016), Uganda (2016), and more recently in Nigeria and Brazil in 2017 have further increased demand, while straining global vaccine supply. Therefore, to vaccinate susceptible populations in preventive mass immunization campaigns during outbreaks, fractional dosing of the vaccine is being considered as a dose-sparing strategy to maximize limited vaccine supplies. Fractional dose yellow fever vaccination refers to administration of a reduced volume of vaccine dose, which has been reconstituted as per manufacturer recommendations. The first practical use of fractional dose yellow fever vaccination was in response to a large yellow fever outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in mid-2016.

In March 2017, the WHO launched a vaccination campaign in Brazil with 3.5 million doses from an emergency stockpile. In March 2017 the WHO recommended vaccination for travellers to certain parts of Brazil. In March 2018, Brazil shifted its policy and announced it planned to vaccinate all 77.5 million currently unvaccinated citizens by April 2019.

Compulsory vaccination

Some countries in Asia are considered to be potentially in danger of yellow fever epidemics, as both mosquitoes with the capability to transmit yellow fever as well as susceptible monkeys are present. The disease does not yet occur in Asia. To prevent introduction of the virus, some countries demand previous vaccination of foreign visitors who have passed through yellow fever areas. Vaccination has to be proved by a vaccination certificate, which is valid 10 days after the vaccination and lasts for 10 years. Although the WHO on 17 May 2013 advised that subsequent booster vaccinations are unnecessary, an older (than 10 years) certificate may not be acceptable at all border posts in all affected countries. A list of the countries that require yellow fever vaccination is published by the WHO. If the vaccination cannot be given for some reason, dispensation may be possible. In this case, an exemption certificate issued by a WHO-approved vaccination center is required. Although 32 of 44 countries where yellow fever occurs endemically do have vaccination programmes, in many of these countries, less than 50% of their population is vaccinated.Vector control

Control of the yellow fever mosquito ''A. aegypti'' is of major importance, especially because the same mosquito can also transmit dengue fever and

Control of the yellow fever mosquito ''A. aegypti'' is of major importance, especially because the same mosquito can also transmit dengue fever and chikungunya

Chikungunya is an infection caused by the ''Chikungunya virus'' (CHIKV). Symptoms include fever and joint pains. These typically occur two to twelve days after exposure. Other symptoms may include headache, muscle pain, joint swelling, and a ras ...

disease. ''A. aegypti'' breeds preferentially in water, for example, in installations by inhabitants of areas with precarious drinking water supplies, or in domestic refuse, especially tires, cans, and plastic bottles. These conditions are common in urban areas in developing countries.

Two main strategies are employed to reduce ''A. aegypti'' populations. One approach is to kill the developing larvae. Measures are taken to reduce the water accumulations in which the larvae develop. Larvicide

A larvicide (alternatively larvacide) is an insecticide that is specifically targeted against the larval life stage of an insect. Their most common use is against mosquitoes. Larvicides may be contact poisons, stomach poisons, growth regulators, ...

s are used, along with larvae-eating fish and copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

s, which reduce the number of larvae. For many years, copepods of the genus ''Mesocyclops

''Mesocyclops'' is a genus of copepod crustaceans in the family Cyclopidae. Because the various species of ''Mesocyclops'' are known to prey on mosquito larvae, it is used as a nontoxic and inexpensive form of biological mosquito control.

Biol ...

'' have been used in Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making it ...

for preventing dengue fever. This eradicated the mosquito vector in several areas. Similar efforts may prove effective against yellow fever. Pyriproxyfen

Pyriproxyfen is a pesticide which is found to be effective against a variety of insects. It was introduced to the US in 1996, to protect cotton crops against whitefly. It has also been found useful for protecting other crops. It is also used as a ...

is recommended as a chemical larvicide, mainly because it is safe for humans and effective in small doses.

The second strategy is to reduce populations of the adult yellow fever mosquito. Lethal ovitrap

A lethal ovitrap is a device which attracts gravid female container-breeding mosquitoes and kills them. The traps halt the insect's life cycle by killing adult insects and stopping reproduction. The original use of ovitraps was to monitor the spr ...

s can reduce ''Aedes'' populations, using lesser amounts of pesticide because it targets the pest directly. Curtains and lids of water tanks can be sprayed with insecticides, but application inside houses is not recommended by the WHO. Insecticide-treated mosquito net

A mosquito net is a type of meshed curtain that is circumferentially draped over a bed or a sleeping area, to offer the sleeper barrier protection against bites and stings from mosquitos, flies, and other pest insects, and thus against the d ...

s are effective, just as they are against the ''Anopheles

''Anopheles'' () is a genus of mosquito first described and named by J. W. Meigen in 1818. About 460 species are recognised; while over 100 can transmit human malaria, only 30–40 commonly transmit parasites of the genus '' Plasmodium'', whi ...

'' mosquito that carries malaria.

Treatment

As with other ''Flavivirus'' infections, no cure is known for yellow fever. Hospitalization is advisable and intensive care may be necessary because of rapid deterioration in some cases. Certain acute treatment methods lack efficacy:passive immunization Passive immunity is the transfer of active humoral immunity of ready-made antibodies. Passive immunity can occur naturally, when maternal antibodies are transferred to the fetus through the placenta, and it can also be induced artificially, when hi ...

after the emergence of symptoms is probably without effect; ribavirin

Ribavirin, also known as tribavirin, is an antiviral medication used to treat RSV infection, hepatitis C and some viral hemorrhagic fevers. For hepatitis C, it is used in combination with other medications such as simeprevir, sofosbuvir, ...

and other antiviral drug

Antiviral drugs are a class of medication used for treating viral infections. Most antivirals target specific viruses, while a broad-spectrum antiviral is effective against a wide range of viruses. Unlike most antibiotics, antiviral drugs d ...

s, as well as treatment with interferon

Interferons (IFNs, ) are a group of signaling proteins made and released by host cells in response to the presence of several viruses. In a typical scenario, a virus-infected cell will release interferons causing nearby cells to heighten t ...

s, are ineffective in yellow fever patients. Symptomatic treatment includes rehydration and pain relief with drugs such as paracetamol

Paracetamol, also known as acetaminophen, is a medication used to treat fever and mild to moderate pain. Common brand names include Tylenol and Panadol.

At a standard dose, paracetamol only slightly decreases body temperature; it is inferi ...

(acetaminophen). Acetylsalicylic acid

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and/or inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions which aspirin is used to treat in ...

(aspirin). However, aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are members of a therapeutic drug class which reduces pain, decreases inflammation, decreases fever, and prevents blood clots. Side effects depend on the specific drug, its dose and duration of ...

(NSAIDs) are often avoided because of an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding due to their anticoagulant effects.

Epidemiology

Yellow fever iscommon

Common may refer to:

Places

* Common, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Boston Common, a central public park in Boston, Massachusetts

* Cambridge Common, common land area in Cambridge, Massachusetts

* Clapham Common, originally ...

in tropical and subtropical areas of South America and Africa. Worldwide, about 600 million people live in endemic areas. The WHO estimates 200,000 cases of yellow fever worldwide each year. About 15% of people infected with yellow fever progress to a severe form of the illness, and up to half of those will die, as there is no cure for yellow fever.

Africa

An estimated 90% of yellow fever infections occur on the African continent. In 2016, a large outbreak originated in Angola and spread to neighboring countries before being contained by a massive vaccination campaign. In March and April 2016, 11 imported cases of the Angola genotype in unvaccinated Chinese nationals were reported in China, the first appearance of the disease in Asia in recorded history.

An estimated 90% of yellow fever infections occur on the African continent. In 2016, a large outbreak originated in Angola and spread to neighboring countries before being contained by a massive vaccination campaign. In March and April 2016, 11 imported cases of the Angola genotype in unvaccinated Chinese nationals were reported in China, the first appearance of the disease in Asia in recorded history.

Phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

analysis has identified seven genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

s of yellow fever viruses, and they are assumed to be differently adapted to humans and to the vector ''A. aegypti''. Five genotypes (Angola, Central/East Africa, East Africa, West Africa I, and West Africa II) occur only in Africa. West Africa genotype I is found in Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of G ...

and the surrounding region. West Africa genotype I appears to be especially infectious, as it is often associated with major outbreaks. The three genotypes found outside of Nigeria and Angola occur in areas where outbreaks are rare. Two outbreaks, in Kenya (1992–1993) and Sudan (2003 and 2005), involved the East African genotype, which had remained undetected in the previous 40 years.

South America

In South America, two genotypes have been identified (South American genotypes I and II). Based on phylogenetic analysis these two genotypes appear to have originated in West Africa and were first introduced into Brazil. The date of introduction of the predecessor African genotype which gave rise to the South American genotypes appears to be 1822 (95% confidence interval 1701 to 1911). The historical record shows an outbreak of yellow fever occurred in Recife, Brazil, between 1685 and 1690. The disease seems to have disappeared, with the next outbreak occurring in 1849. It was likely introduced with the trafficking of slaves through the

In South America, two genotypes have been identified (South American genotypes I and II). Based on phylogenetic analysis these two genotypes appear to have originated in West Africa and were first introduced into Brazil. The date of introduction of the predecessor African genotype which gave rise to the South American genotypes appears to be 1822 (95% confidence interval 1701 to 1911). The historical record shows an outbreak of yellow fever occurred in Recife, Brazil, between 1685 and 1690. The disease seems to have disappeared, with the next outbreak occurring in 1849. It was likely introduced with the trafficking of slaves through the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

from Africa. Genotype I has been divided into five subclades, A through E.

In late 2016, a large outbreak began in Minas Gerais

Minas Gerais () is a state in Southeastern Brazil. It ranks as the second most populous, the third by gross domestic product (GDP), and the fourth largest by area in the country. The state's capital and largest city, Belo Horizonte (literall ...

state of Brazil that was characterized as a sylvan or jungle epizootic

In epizoology, an epizootic (from Greek: ''epi-'' upon + ''zoon'' animal) is a disease event in a nonhuman animal population analogous to an epidemic in humans. An epizootic may be restricted to a specific locale (an "outbreak"), general (an "ep ...

. It began as an outbreak in brown howler monkeys, which serve as a sentinel species

Sentinel species are organisms, often animals, used to detect risks to humans by providing advance warning of a danger. The terms primarily apply in the context of environmental hazards rather than those from other sources. Some animals can act ...

for yellow fever, that then spread to men working in the jungle. No cases had been transmitted between humans by the ''A. aegypti'' mosquito, which can sustain urban outbreaks that can spread rapidly. In April 2017, the sylvan outbreak continued moving toward the Brazilian coast, where most people were unvaccinated. By the end of May the outbreak appeared to be declining after more than 3,000 suspected cases, 758 confirmed and 264 deaths confirmed to be yellow fever. The Health Ministry launched a vaccination campaign and was concerned about spread during the Carnival

Carnival is a Catholic Christian festive season that occurs before the liturgical season of Lent. The main events typically occur during February or early March, during the period historically known as Shrovetide (or Pre-Lent). Carnival ...

season in February and March. The CDC issued a Level 2 alert (practice enhanced precautions.)

A Bayesian analysis of genotypes I and II has shown that genotype I accounts for virtually all the current infections in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, Colombia, Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in ...

, and Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

and Tobago

Tobago () is an island and ward within the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. It is located northeast of the larger island of Trinidad and about off the northeastern coast of Venezuela. It also lies to the southeast of Grenada. The offici ...

, while genotype II accounted for all cases in Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

. Genotype I originated in the northern Brazilian region around 1908 (95% highest posterior density interval PD 1870–1936). Genotype II originated in Peru in 1920 (95% HPD: 1867–1958). The estimated rate of mutation for both genotypes was about 5 × 10−4 substitutions/site/year, similar to that of other RNA viruses.

Asia

The main vector (''A. aegypti'') also occurs in tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, the Pacific, and Australia, but yellow fever has never occurred there, until jet travel introduced 11 cases from the2016 Angola and DR Congo yellow fever outbreak

On 20 January 2016, the health minister of Angola reported 23 cases of yellow fever with 7 deaths among Eritrean and Congolese citizens living in Angola in Viana municipality, a suburb of the capital of Luanda. The first cases (hemorrhagic feve ...

in Africa. Proposed explanations include:

* That the strains of the mosquito in the east are less able to transmit ''yellow fever virus''.

* That immunity is present in the populations because of other diseases caused by related viruses (for example, dengue

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by the dengue virus. Symptoms typically begin three to fourteen days after infection. These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic ...

).

* That the disease was never introduced because the shipping trade was insufficient.

But none is considered satisfactory. Another proposal is the absence of a slave trade to Asia on the scale of that to the Americas. The trans-Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

probably introduced yellow fever into the Western Hemisphere from Africa.

History

Early history

The evolutionary origins of yellow fever most likely lie in Africa, with transmission of the disease from nonhuman primates to humans. The virus is thought to have originated in East or Central Africa and spread from there to West Africa. As it was endemic in Africa, local populations had developed some immunity to it. When an outbreak of yellow fever would occur in an African community where colonists resided, most Europeans died, while the indigenous Africans usually developed nonlethal symptoms resemblinginfluenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

. This phenomenon, in which certain populations develop immunity to yellow fever due to prolonged exposure in their childhood, is known as acquired immunity. The virus, as well as the vector ''A. aegypti,'' were probably transferred to North and South America with the trafficking of slaves from Africa, part of the Columbian exchange

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the New World (the Americas) in ...

following European exploration and colonization. However, some researchers have argued that yellow fever might have existed in the Americas during the pre-Columbian period as mosquitoes of the genus ''Haemagogus'', which is indigenous to the Americas, have been known to carry the disease.

The first definitive outbreak of yellow fever in the New World was in 1647 on the island of Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate ...

. An outbreak was recorded by Spanish colonists in 1648 in the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula (, also , ; es, Península de Yucatán ) is a large peninsula in southeastern Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north ...

, where the indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

* Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

* Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehor ...

Mayan people

Mayan most commonly refers to:

* Maya peoples, various indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica and northern Central America

* Maya civilization, pre-Columbian culture of Mesoamerica and northern Central America

* Mayan languages, language family spoken ...

called the illness ''xekik'' ("blood vomit"). In 1685, Brazil suffered its first epidemic in Recife

That it may shine on all ( Matthew 5:15)

, image_map = Brazil Pernambuco Recife location map.svg

, mapsize = 250px

, map_caption = Location in the state of Pernambuco

, pushpin_map = Brazil#South A ...

. The first mention of the disease by the name "yellow fever" occurred in 1744.

* (John Mitchell) (1805(Mitchell's account of the Yellow Fever in Virginia in 1741–2)

, ''The Philadelphia Medical Museum,'' 1 (1) : 1–20. * (John Mitchell) (1814

"Account of the Yellow fever which prevailed in Virginia in the years 1737, 1741, and 1742, in a letter to the late Cadwallader Colden, Esq. of New York, from the late John Mitchell, M.D.F.R.S. of Virginia,"

''American Medical and Philosophical Register'', 4 : 181–215. The term "yellow fever" appears on p. 186. On p. 188, Mitchell mentions "… the distemper was what is generally called yellow fever in America". However, on pages 191–192, he states "… I shall consider the cause of the yellowness which is so remarkable in this distemper, as to have given it the name of the Yellow Fever." However, Dr. Mitchell misdiagnosed the disease that he observed and treated, and the disease was probably Weil's disease or hepatitis. McNeill argues that the environmental and ecological disruption caused by the introduction of

sugar plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

created the conditions for mosquito and viral reproduction, and subsequent outbreaks of yellow fever. Deforestation reduced populations of insectivorous birds and other creatures that fed on mosquitoes and their eggs.

Colonial times

The ''Colonial Times'' was a newspaper in what is now the Australian state of Tasmania. It was established as the ''Colonial Times, and Tasmanian Advertiser'' in 1825 in Hobart, Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the col ...

and during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, the West Indies were known as a particularly dangerous posting for soldiers due to yellow fever being endemic in the area. The mortality rate in British garrisons in Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispan ...

was seven times that of garrisons in Canada, mostly because of yellow fever and other tropical diseases. Both English and French forces posted there were seriously affected by the "yellow jack". Wanting to regain control of the lucrative sugar trade in Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to ref ...

(Hispaniola), and with an eye on regaining France's New World empire, Napoleon sent an army under the command of his brother-in-law General Charles Leclerc

Charles Marc Hervé Perceval Leclerc (; born 16 October 1997) is a Monégasque racing driver, currently racing in Formula One for Scuderia Ferrari. He won the GP3 Series championship in 2016 and the FIA Formula 2 Championship in .

Leclerc ma ...

to Saint-Domingue to seize control after a slave revolt. The historian J. R. McNeill asserts that yellow fever accounted for about 35,000 to 45,000 casualties of these forces during the fighting. Only one third of the French troops survived for withdrawal and return to France. Napoleon gave up on the island and his plans for North America, selling the Louisiana Purchase to the US in 1803. In 1804, Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

proclaimed its independence as the second republic in the Western Hemisphere. Considerable debate exists over whether the number of deaths caused by disease in the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt began on 22 ...

was exaggerated.

Although yellow fever is most prevalent in tropical-like climates, the northern United States were not exempted from the fever. The first outbreak in English-speaking North America occurred in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

in 1668. English colonists in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

and the French in the Mississippi River Valley

The Mississippi embayment is a physiographic feature in the south-central United States, part of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain. It is essentially a northward continuation of the fluvial sediments of the Mississippi River Delta to its confl ...

recorded major outbreaks in 1669, as well as additional yellow fever epidemics in Philadelphia, Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, and New York City in the 18th and 19th centuries. The disease traveled along steamboat routes from New Orleans, causing some 100,000–150,000 deaths in total. The yellow fever epidemic of 1793

During the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, 5,000 or more people were listed in the official register of deaths between August 1 and November 9. The vast majority of them died of yellow fever, making the epidemic in the city of 50,000 ...

in Philadelphia, which was then the capital of the United States, resulted in the deaths of several thousand people, more than 9% of the population. One of these deaths was James Hutchinson, a physician helping to treat the population of the city. The national government fled the city to Trenton, New Jersey, including President George Washington.

The southern city of

The southern city of New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

At least 25 major outbreaks took place in the Americas during the 18th and 19th centuries, including particularly serious ones in  In 1853,

In 1853,

Ezekiel Stone Wiggins, known as the Ottawa Prophet, proposed that the cause of a yellow fever epidemic in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1888, was astrological.

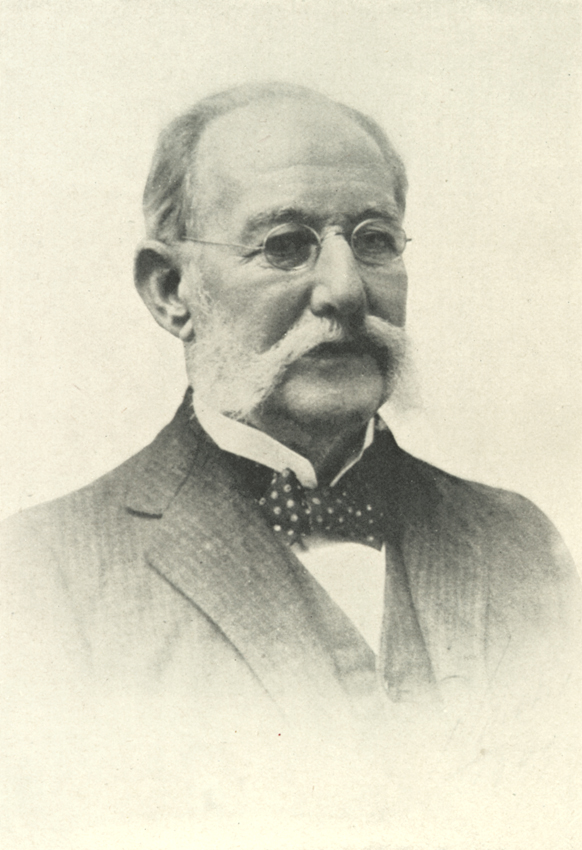

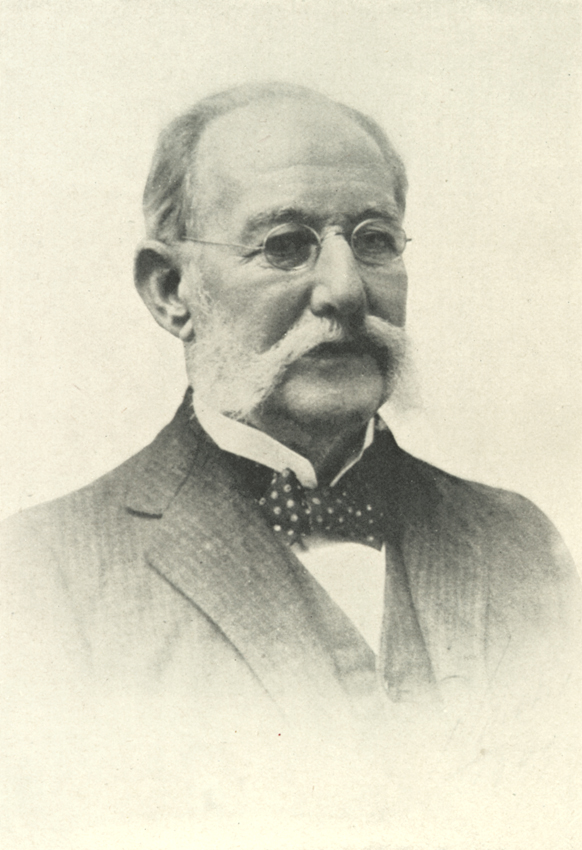

In 1848, Josiah C. Nott suggested that yellow fever was spread by insects such as moths or mosquitoes, basing his ideas on the pattern of transmission of the disease. Carlos Finlay, a Cuban doctor and scientist, proposed in 1881 that yellow fever might be transmitted by previously infected

Ezekiel Stone Wiggins, known as the Ottawa Prophet, proposed that the cause of a yellow fever epidemic in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1888, was astrological.

In 1848, Josiah C. Nott suggested that yellow fever was spread by insects such as moths or mosquitoes, basing his ideas on the pattern of transmission of the disease. Carlos Finlay, a Cuban doctor and scientist, proposed in 1881 that yellow fever might be transmitted by previously infected  During 1920–1923, the Rockefeller Foundation's International Health Board undertook an expensive and successful yellow fever eradication campaign in Mexico. The IHB gained the respect of Mexico's federal government because of the success. The eradication of yellow fever strengthened the relationship between the US and Mexico, which had not been very good in the years prior. The eradication of yellow fever was also a major step toward better global health.

In 1927, scientists isolated the ''yellow fever virus'' in West Africa. Following this, two vaccines were developed in the 1930s.

During 1920–1923, the Rockefeller Foundation's International Health Board undertook an expensive and successful yellow fever eradication campaign in Mexico. The IHB gained the respect of Mexico's federal government because of the success. The eradication of yellow fever strengthened the relationship between the US and Mexico, which had not been very good in the years prior. The eradication of yellow fever was also a major step toward better global health.

In 1927, scientists isolated the ''yellow fever virus'' in West Africa. Following this, two vaccines were developed in the 1930s.

"U.S. Army Yellow Fever Commission."

Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia * {{DEFAULTSORT:Yellow Fever Yellow fever, Biological weapons Epidemics Wikipedia medicine articles ready to translate Wikipedia infectious disease articles ready to translate Tropical diseases Vaccine-preventable diseases

Cartagena, Chile

Cartagena is a Chilean Communes of Chile, commune located in the San Antonio Province, Valparaíso Region. The commune spans an area of .

History

In the seventeenth century the area surrounding the town became a major producer of wheat, which wa ...

, in 1741; Cuba in 1762 and 1900; Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

in 1803; and Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the County seat, seat of Shelby County, Tennessee, Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 Uni ...

, in 1878.

In the early nineteenth century, the prevalence of yellow fever in the Caribbean "led to serious health problems" and alarmed the United States Navy