SMS Stralsund on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS was a

was

was

After the war, was not included in the fleet that was interned at Scapa Flow during the peace negotiations. She was instead permitted to remain in Germany, and the naval command hoped that she could be preserved for the postwar . But after the scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow in June 1919, shortly before the Treaty of Versailles was signed, this proved to be an unrealistic expectation. The Treaty of Versailles specified that the ship was to be disarmed and handed over to the Allies within two months of the signing of the treaty.See: s:Treaty of Versailles 1919, Treaty of Versailles Section II: Naval Clauses, Article 185 was accordingly struck from the naval register on 5 November 1919. She was ceded to France as a war prize under the transaction name "Z". Departing Germany on 28 July 1920 in company with the torpedo boat , the ships arrived in Cherbourg, France, on 3 August. There, she was formally handed that day.

On arriving in France, she underwent a minor refit that consisted primarily of replacing her 8.8 cm guns with anti-aircraft guns, though the rest of her original armament remained. She was renamed in honor of the Mulhouse, eponymous city in Alsace that had been recovered from Germany at the end of World War I. She and four other ex-German or ex-Austro-Hungarian cruisers were commissioned into the

After the war, was not included in the fleet that was interned at Scapa Flow during the peace negotiations. She was instead permitted to remain in Germany, and the naval command hoped that she could be preserved for the postwar . But after the scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow in June 1919, shortly before the Treaty of Versailles was signed, this proved to be an unrealistic expectation. The Treaty of Versailles specified that the ship was to be disarmed and handed over to the Allies within two months of the signing of the treaty.See: s:Treaty of Versailles 1919, Treaty of Versailles Section II: Naval Clauses, Article 185 was accordingly struck from the naval register on 5 November 1919. She was ceded to France as a war prize under the transaction name "Z". Departing Germany on 28 July 1920 in company with the torpedo boat , the ships arrived in Cherbourg, France, on 3 August. There, she was formally handed that day.

On arriving in France, she underwent a minor refit that consisted primarily of replacing her 8.8 cm guns with anti-aircraft guns, though the rest of her original armament remained. She was renamed in honor of the Mulhouse, eponymous city in Alsace that had been recovered from Germany at the end of World War I. She and four other ex-German or ex-Austro-Hungarian cruisers were commissioned into the

light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

of the German Kaiserliche Marine

The adjective ''kaiserlich'' means "imperial" and was used in the German-speaking countries to refer to those institutions and establishments over which the ''Kaiser'' ("emperor") had immediate personal power of control.

The term was used partic ...

. Her class included three other ships: , , and . She was built at the AG Weser

Aktien-Gesellschaft "Weser" (abbreviated A.G. "Weser") was one of the major Germany, German shipbuilding companies, located at the Weser River in Bremen. Founded in 1872 it was finally closed in 1983. All together, A.G. „Weser" built about 1,4 ...

shipyard in Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (, ), is the capital of the States of Germany, German state of the Bremen (state), Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (), a two-city-state consisting of the c ...

from 1910 to December 1912, when she was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet () was the battle fleet of the German Empire, German Imperial German Navy, Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. In February 1907, the Home Fleet () was renamed the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpi ...

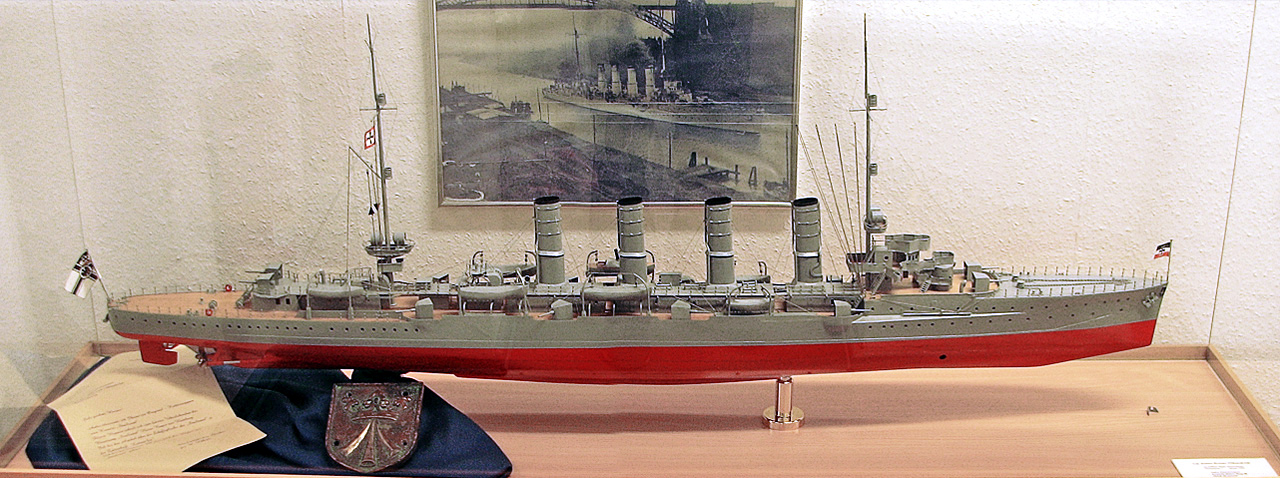

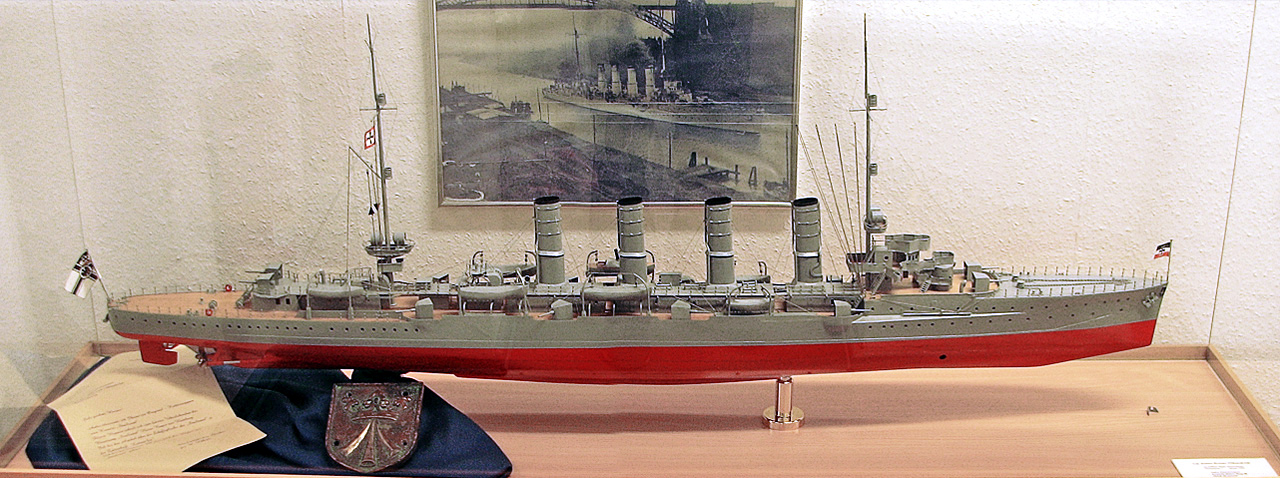

. The ship was armed with a main battery of twelve 10.5 cm SK L/45 guns and had a top speed of .

was assigned to the reconnaissance forces of the High Seas Fleet for the majority of her career. She saw significant action in the early years of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, including several operations off the British coast and the Battles of Heligoland Bight

The Heligoland Bight, also known as Helgoland Bight, (, ) is a bay which forms the southern part of the German Bight, itself a bay of the North Sea, located at the mouth of the Elbe river. The Heligoland Bight extends from the mouth of the Elb ...

and Dogger Bank

Dogger Bank ( Dutch: ''Doggersbank'', German: ''Doggerbank'', Danish: ''Doggerbanke'') is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about off the east coast of England.

During the last ice age, the bank was part of a large landmass ...

, in August 1914 and November 1915, respectively. She was not damaged in either action. The ship was in dockyard hands during the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland () was a naval battle between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, durin ...

, and so she missed the engagement. After the end of the war, she served briefly in the before being surrendered to the Allies. She was ceded to the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

, where she served as until 1925. She was formally stricken in 1933 and broken up for scrap two years later.

Design

The s were designed in response to the development of the British s, which were faster than all existing German light cruisers. As a result, speed of the new ships must be increased. To accomplish this, more powerful engines were fitted and their hulls were lengthened to improve their hydrodynamic efficiency. These changes increased top speed from over the preceding s. To save weight,longitudinal framing

Longitudinal framing (also called the Isherwood system after Great Britain, British naval architect Sir Joseph Isherwood, who patented it in 1906) is a method of ship construction in which large, widely spaced Transverse framing, transverse fram ...

was adopted for the first time in a major German warship design. In addition, the s were the first cruisers to carry belt armor

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

, which was necessitated by the adoption of more powerful guns in the latest British cruisers.

was

was long overall

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, and is also u ...

and had a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Radio beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially lo ...

of and a draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

of forward. She displaced normally and up to at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into weig ...

. The ship had a short forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck (ship), deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is t ...

deck and a minimal superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

that consisted primarily of a conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

located on the forecastle. She was fitted with two pole masts with platforms for searchlight

A searchlight (or spotlight) is an apparatus that combines an extremely luminosity, bright source (traditionally a carbon arc lamp) with a mirrored parabolic reflector to project a powerful beam of light of approximately parallel rays in a part ...

s. had a crew of 18 officers and 336 enlisted men.

Her propulsion system consisted of three sets of Bergmann steam turbine

A steam turbine or steam turbine engine is a machine or heat engine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work utilising a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Par ...

s driving three screw propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

s. These were powered by sixteen coal-fired Marine-type water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-generat ...

s, although they were later altered to use fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil (bunker fuel), marine f ...

that was sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate. The boilers were vented through four funnels

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its constructi ...

located amidships. They were designed to give for a top speed of , but she reached and a top speed of during her initial speed testing. carried of coal, and an additional of oil that gave her a range of approximately at .

The ship was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a naval gun or group of guns used in volleys, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, th ...

of twelve SK L/45 guns in single pedestal mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, eight were located on the broadside, four on either side, and two were side by side aft. The guns had a maximum elevation of 30 degrees, which allowed them to engage targets out to . They were supplied with 1,800 rounds of ammunition, for 150 shells per gun. She was also equipped with a pair of torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s with five torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

es; the tubes were submerged in the hull on the broadside. She could also carry 120 mines

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

*Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

Mi ...

.

was protected by a waterline armor belt

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

and a curved armor deck. The deck was flat across most of the hull, but angled downward at the sides and connected to the bottom edge of the belt. The belt and deck were both thick. The conning tower had thick sides.

Service history

was ordered under the contract name " ", and waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

at the AG Weser

Aktien-Gesellschaft "Weser" (abbreviated A.G. "Weser") was one of the major Germany, German shipbuilding companies, located at the Weser River in Bremen. Founded in 1872 it was finally closed in 1983. All together, A.G. „Weser" built about 1,4 ...

shipyard in Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (, ), is the capital of the States of Germany, German state of the Bremen (state), Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (), a two-city-state consisting of the c ...

in September 1910 and launched on 4 November 1911; during the launching ceremony, the mayor of Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish language, Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German language, German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklen ...

, Ernst Gronow, gave a speech. Fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work thereafter commenced. Named for the earlier schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

, she was commissioned into active service on 10 December 1912. (FK—Frigate Captain) Magnus von Levetzow served as her first commander, though he served only briefly in that role, before being replaced by FK Victor Harder in January 1913. After entering service, conducted sea trials

A sea trial or trial trip is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on o ...

, which lasted until 15 February. The ship then joined the Unit of Reconnaissance Ships, assigned to II Scouting Group

II is the Roman numeral for 2.

II may also refer to:

Biology and medicine

*Image intensifier, medical imaging equipment

*Invariant chain, a polypeptide involved in the formation and transport of MHC class II protein

*Optic nerve, the second c ...

, where she took part in the peacetime routine of training exercises and cruises with the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet () was the battle fleet of the German Empire, German Imperial German Navy, Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. In February 1907, the Home Fleet () was renamed the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpi ...

for the next year.

World War I

On 16 August, some two weeks after the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, and were ordered to carry out a sweep into the Hoofden to search for British reconnaissance forces, in the hopes of surprising patrolling British destroyers. The operation was led by Harder aboard . They were accompanied by the U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s ''U-19'' and ''U-24'', which were to ambush any British forces that counter-attacked. The two cruisers departed late on 17 August and early the following morning, they passed through the British patrol line in darkness; at around 04:45, they reversed course with the intention surprising the British destroyers from behind. and steamed about apart to increase their chances of locating British forces; at 06:39, spotted a group of eight or ten destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s and the light cruiser at a distance of about . The British commander aboard ''Fearless'' initially mistook for an armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a pre-dreadnought battles ...

and he initially ordered his ships to refrain from attacking her. , for her part, immediately opened fire on the nearest destroyers. After about half an hour of inaccurate shooting from both sides, German lookouts spotted what they thought was a second British cruiser approaching, so Harder decided to break off the engagement.

Battle of Helgoland Bight

In response to s raid on the British patrol line, the British naval command decided to stage a retaliatory raid on the German defenses in the Helgoland Bight, to be carried out by theHarwich Force

The Harwich Force originally called Harwich Striking Force was a squadron of the Royal Navy, formed during the First World War and based in Harwich. It played a significant role in the war.

History

After the outbreak of the First World War, it ...

. This led to the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28 August 1914. British battlecruisers and light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

s raided the German reconnaissance screen in the Heligoland Bight

The Heligoland Bight, also known as Helgoland Bight, (, ) is a bay which forms the southern part of the German Bight, itself a bay of the North Sea, located at the mouth of the Elbe river. The Heligoland Bight extends from the mouth of the Elb ...

. At the start of the action, and the rest of II Scouting Group were at anchor in Wilhelmshaven, and as soon as reports of British cruisers arrived at the naval command, II Scouting Group was ordered to sea immediately. By 11:30, had gotten underway, following and the light cruiser .

At around 13:40, , heard the sound of shooting in the distance, and shortly after 14:00, she encountered three British cruisers and a battlecruiser. She came under heavy fire, but suffered only a single hit that failed to explode, though shell fragments from near misses injured several crewmen. quickly disengaged and fled south before turning north to come to the aid of the stricken , which had been badly damaged by the British battlecruisers and picked up around sixty men from . and the rest of the surviving light cruisers retreated into the haze and were reinforced by the battlecruisers of the I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group () was a special reconnaissance unit within the German '' Kaiserliche Marine''. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the most active formations in th ...

under (KAdm—Rear Admiral) Franz Hipper

Franz Ritter von Hipper (born Franz Hipper; 13 September 1863 – 25 May 1932) was an admiral in the German Imperial Navy, (''Kaiserliche Marine'') who played an important role in the naval warfare of World War I. Franz von Hipper joined th ...

. and returned and rescued most of the crew of . During the battle, only received a single hit, and none of her crew were wounded.

Raid on Yarmouth

On 9 September, and the cruiser escorted the minelaying cruisers and and the auxiliary minelayer while they laid a minefield in the North Sea. In late September, was temporarily moved to theBaltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

, where she took part in a sweep for Russian forces as far north as the northern tip of Gotland

Gotland (; ; ''Gutland'' in Gutnish), also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (), is Sweden's largest island. It is also a Provinces of Sweden, province/Counties of Sweden, county (Swedish län), Municipalities of Sweden, municipality, a ...

. She soon returned to the North Sea, and with II Scouting Group, sortied with the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group for the raid on Yarmouth

The Raid on Yarmouth, on 3 November 1914, was an attack by the Imperial German Navy on the British North Sea port and town of Great Yarmouth. German shells only landed on the beach causing little damage to the town, after German ships laying m ...

. The operation was carried out on 2–3 November 1914, and the ships of II Scouting Group served as the reconnaissance screen for battlecruisers. While the battlecruisers bombarded the town of Yarmouth, laid a minefield, which sank a steamer and the submarine which had sortied to intercept the German raiders. After completing the bombardment, the German squadron returned to port without encountering British forces. and II Scouting Group next went to sea on 20 November in company with I Scouting Group for an uneventful patrol.

Raid of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby

Another battlecruiser raid was carried out on 15–16 December, this time against the coastal towns of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby. The two scouting groups left the Jade at 03:20. Hipper's ships sailed north, through the channels in the minefields, past Helgoland to theHorns Rev

Horns Rev is a shallow sandy reef of glacial deposits in the eastern North Sea, about off the westernmost point of Denmark, Blåvands Huk.

light vessel, at which point the ships turned westward, towards the English coast. The main battle squadrons of the High Seas Fleet left in the late afternoon of the 15th. During the night of 15 December, the main body of the High Seas Fleet encountered British destroyers, and fearing the prospect of a night-time torpedo attack, Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Friedrich von Ingenohl (30 June 1857 – 19 December 1933) was a German admiral from Neuwied best known for his command of the German High Seas Fleet at the beginning of World War I.

He was the son of a tradesman. He j ...

ordered the ships to retreat. Hipper's ships carried out the bombardment regardless, though they were unaware of Ingenohl's withdrawal. They then turned back to rendezvous with the German fleet.

By this time, the British battlecruiser force was in position to block Hipper's egress route, while other forces were en route to complete the encirclement. At 12:25, the light cruisers of II Scouting Group began to pass the British forces searching for Hipper. One of the cruisers in the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron spotted , and signaled a report to Beatty. At 12:30, Beatty turned his battlecruisers towards the German ships. Beatty presumed that the German cruisers were the advance screen for Hipper's ships, however, those were some 50 km (31 mi) ahead. The 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, which had been screening for Beatty's ships, detached to pursue the German cruisers, but a misinterpreted signal from the British battlecruisers sent them back to their screening positions. This confusion allowed the German light cruisers to escape, and alerted Hipper to the location of the British battlecruisers. The German battlecruisers wheeled to the northeast of the British forces and made good their escape.

1915

On 25 December 1914, the British launched theCuxhaven Raid

The Raid on Cuxhaven (, Christmas Raid) was a British ship-based air-raid on the Imperial German Navy at Cuxhaven mounted on Christmas Day, 1914.

Aircraft of the Royal Naval Air Service were carried to within striking distance by seaplane tend ...

, an air attack on the German naval base in Cuxhaven

Cuxhaven (; ) is a town and seat of the Cuxhaven district, in Lower Saxony, Germany. The town includes the northernmost point of Lower Saxony. It is situated on the shore of the North Sea at the mouth of the Elbe River. Cuxhaven has a footprint o ...

and the Nordholz Airbase. engaged one of the attacking seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tech ...

s, but was unable to shoot it down. joined the light cruiser on 3 January 1915 for a patrol into the North Sea to the west of Amrun Bank that ended without locating British forces. next carried out a minelaying operation in company with on 14–15 January off the Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Trent, Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms ...

. The ship was again part of the reconnaissance screen for the I Scouting Group at the Battle of Dogger Bank on 24 January. and were assigned to the front of the screen and and steamed on either side of the formation; each cruiser was supported by a half-flotilla of torpedo boats. At 08:15, lookouts on and spotted heavy smoke from large British warships approaching the formation. As the main German fleet was in port and therefore unable to support the battlecruisers, Hipper decided to retreat at high speed. The British battlecruisers were able to catch up to the Germans, however, and in the ensuing battle, the large armored cruiser was sunk.

moved to the Baltic for another operation from 17 to 28 March, which targeted Russian forces that were attacking near Memel. On 23 March, she bombarded Russian positions and troop concentrations at Polangen

Palanga (; ; ) is a resort city in western Lithuania, on the shore of the Baltic Sea.

Palanga is the busiest and the largest summer resort in Lithuania and has sandy beaches (18 km, 11 miles long and up to 300 metres, 1000 ft wide) an ...

, just to the north of Memel. She returned to the North Sea immediately, in time to participate in a fleet sweep into the North Sea on 29–30 March. She went to sea again on 17 April for a minelaying operation in company with that lasted until the following day, this time to lay mines off the Swarte Bank

Swart is an Afrikaans, Dutch and German surname meaning "black" (spelled ''zwart'' in modern Dutch). Variations on it are ''de Swart'', ''Swarte'', ''de Swarte'', ''Swarts'', Zwart, de Zwart, and Zwarts. People with this surname include:

* Alfr ...

. and the rest of II Scouting Group carried out a patrol to the Dogger Bank area on 17–18 May. Another sortie by the entire High Seas Fleet took place on 29–30 May, and like the previous operations, the Germans failed to locate any British vessels. embarked on sweeps on 28 June in the direction of Terschelling

Terschelling (; ; Terschelling dialect: ''Schylge'') is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and an island in the northern Netherlands, one of the West Frisian Islands. It is situated between the islands of Vlieland and Ameland.

...

and on 2 July toward Horns Rev, again without result. That month, FK Karl Weniger replaced Harder as the ship's commander.

In August, and the rest of II Scouting Group returned to the Baltic to take part in the Battle of the Gulf of Riga

The Battle of the Gulf of Riga was a World War I naval operation of the German High Seas Fleet against the Russian Baltic Fleet in the Gulf of Riga in the Baltic Sea in August 1915. The operation's objective was to destroy the Russian naval forc ...

. The ships served as part of the covering force, under Hipper's command, that patrolled outside the gulf to prevent any Russian ships from counterattacking. During this period, came under attack by the British submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

, but the submarine's torpedoes missed. By 29 August, had returned to the North Sea. She loaded 140 mines for another minelaying operation on 11–12 September; she laid this field between Terschelling and the Swarte Bank. Another fleet sortie took place on 23–24 October. For , the year's operations came to an end with a sweep by II Scouting Group into the Skagerrak

The Skagerrak (; , , ) is a strait running between the North Jutlandic Island of Denmark, the east coast of Norway and the west coast of Sweden, connecting the North Sea and the Kattegat sea.

The Skagerrak contains some of the busiest shipping ...

and Kattegat

The Kattegat (; ; ) is a sea area bounded by the peninsula of Jutland in the west, the Danish straits islands of Denmark and the Baltic Sea to the south and the Swedish provinces of Bohuslän, Västergötland, Halland and Scania in Swede ...

from 16 to 18 December.

1916–1918

participated in a pair of patrols into the North Sea on 2–3 and 11 February 1916. She was then detached from II Scouting Group on 19 February for a major refit that began two days later at the shipyard inKiel

Kiel ( ; ) is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein. With a population of around 250,000, it is Germany's largest city on the Baltic Sea. It is located on the Kieler Förde inlet of the Ba ...

. Her twelve 10.5 cm guns were replaced with seven 15 cm SK L/45

The 15 cm SK L/45SK - ''Schnelladekanone'' (quick loading cannon); ''L - Länge in Kaliber'' ( length in caliber) was a German naval gun used in World War I and World War II.

Naval service

The 15 cm SK L/45 was a widely used naval gun o ...

guns and two 8.8 cm SK L/45 guns. She also had her forecastle extended by to raise the height of her broadside guns a deck higher, and her torpedo tubes were moved to the middle deck. She also had a night-fighting control station installed on the roof of her bridge

A bridge is a structure built to Span (engineering), span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or railway) without blocking the path underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, whi ...

. The work lasted until 17 June, and as a result, the ship was not available for the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland () was a naval battle between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, durin ...

on 31 May – 1 June. In June, (KzS—Captain at Sea) Hans Gygas relieved Weniger as the ship's captain. returned to active service on 6 July, and she briefly served as the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

of KAdm Ludwig von Reuter

Hans Hermann Ludwig von Reuter (9 February 1869 – 18 December 1943) was a German admiral who commanded the High Seas Fleet when it was interned at Scapa Flow in the north of Scotland at the end of World War I. On 21 June 1919 he ordered t ...

, the commander of IV Scouting Group; she held this role from 10 to 17 July. She then returned to II Scouting Group, serving as its flagship from 4 August to 30 October, initially under KAdm Friedrich Boedicker until 11 September, when he was replaced by Reuter. During this period, she led II Scouting Group during the fleet sortie on 18–20 August, which resulted in the action of 19 August 1916

The action of 19 August 1916 was one of two attempts in 1916 by the German High Seas Fleet to engage elements of the British Grand Fleet, following the mixed results of the Battle of Jutland, during the First World War. The lesson of Jutland for ...

, an inconclusive clash that left several ships on both sides damaged or sunk by submarines, but no direct fleet encounter.

On 12 September, embarked a floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

, which was used operationally for the first time during a fleet sweep to the east of the Dogger Bank on 18–20 October. She went to sea on 4–5 November with the High Seas Fleet to come to the aid of the U-boats ''U-20'' and ''U-30'', which had run aground

Ship grounding or ship stranding is the impact of a ship on seabed or

waterway side. It may be intentional, as in beaching to land crew or cargo, and careening, for maintenance or repair, or unintentional, as in a marine accident. In accidenta ...

on the coast of Denmark. was transferred from II Scouting Group to IV Scouting Group on 2 December, where she became the flagship of KAdm Karl Seiferling, though he remained aboard for only nine days. participated in a patrol out to the Fisher Bank on 27–28 December. On 10 January 1917, the ships of IV Scouting Group carried out a minelaying operation in the North Sea between Helgoland and Norderney

Norderney (; ) is one of the seven populated East Frisian Islands off the North Sea coast of Germany.

The island is , having a total area of about and is therefore Germany's ninth-largest island. Norderney's population amounts to about 5,850 ...

; they were reinforced by the cruiser during the operation. On 15 January, (Commodore) Max Hahn

Max Hahn (born 30 April 1981) is a Luxembourgish politician of the Democratic Party serving as Minister for Family Affairs since 2023. He was previously a member of the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many ...

took command of IV Scouting Group, making his flagship. spent the next several months participating in patrols of the southern North Sea, interrupted only by a period in the shipyard at the in Kiel for repairs to her turbines, which lasted from 7 August to 15 October. While was under repair, Hahn shifted his flag permanently to the cruiser .

On 22 October, was ready to return to service, and she was sent to Libau in the Baltic. Operation Albion

Operation Albion was a German air, land and naval operation in the First World War, against Russian forces in October 1917 to occupy the West Estonian Archipelago. The campaign aimed to occupy the Baltic islands of Saaremaa (Ösel), Hii ...

, the amphibious attack on the islands in the Gulf of Riga

The Gulf of Riga, Bay of Riga, or Gulf of Livonia (, , ) is a bay of the Baltic Sea between Latvia and Estonia.

The island of Saaremaa (Estonia) partially separates it from the rest of the Baltic Sea. The main connection between the gulf and t ...

, had already ended in a German victory, so the ship quickly returned to the North Sea. From 11 to 20 November, KzS Paul Heinrich

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo P ...

—the commander of I Torpedo-boat Flotilla—used as his flagship. While Heinrich was aboard, the ship took part in a pair of sweeps into the North Sea as far as the lightship

A lightvessel, or lightship, is a ship that acts as a lighthouse. It is used in waters that are too deep or otherwise unsuitable for lighthouse construction. Although some records exist of fire beacons being placed on ships in Roman times, the ...

on 12 and 17 November. On 2 February 1918, while covering a minesweeping unit in the North Sea, struck a mine laid by British ships. Though two of her watertight compartments flooded, she was able to steam under her own power back to Wilhelmshaven. The dreadnought and several other ships steamed out to escort back to port. Repairs lasted from 4 February to 25 April, and as a result, the ship was unavailable for the major fleet operation on 23–24 April to intercept a British convoy to Norway.

After returning to service, joined the rest of IV Scouting Group for training exercises in the Baltic on 27 April. There, on 16 May, she was assigned as the flagship of KAdm Hugo Meurer, the commander of a (special unit) that was to operate in the eastern Baltic. She sailed to Mariehamn, arriving on 19 May, where she relieved the cruiser , which had been operating in the area. From there, sailed for Helsingfors, Finland; there, KAdm Ludolf von Uslar replaced Meurer as the commander of naval forces in the area. Over the next few weeks, the ship cruised to various ports in the region, including Reval, Estonia; Mariehamn, Hanko, Finland, Hanko, and Turku, Finland; Windau, Latvia; and Libau. The ship then departed Libau for Kiel, before moving back to the North Sea on 24 June. She remained there until 8 August, when she was ordered back to the Baltic for a major operation.

Operation Schlußstein and the end of the war

was assigned to a new , which was to carry out Operation Schlußstein, under the command of now (Vice Admiral) Boedicker. The planned operation came about as a result of the uncertain military and political situation in Russia in the summer of 1918. The nascent Soviet government was fighting the Russian Civil War against the White movement, Whites, and British forces had North Russia intervention, intervened in northern Russia, occupying Murmansk. The Soviets, who had signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany, requested German help to expel the British, fight White forces, and suppress the Don Cossacks. Though Germany was interested in defeating British forces in north Russia, the German command had no desire to fight the anti-communist Whites or the Cossacks. Operation Schlußstein marked the beginning phase of the campaign against the British intervention in northern Russia; it was to begin with the occupation of St. Petersburg. The ships assigned to Operation Schlußstein included the dreadnoughts , , and ; the ships of IV Scouting Group—, , , and —the cruiser ; the aviso ; V Torpedoboat Flotilla; a seaplane tender, and numerous mine-warfare vessels and smaller craft. On 12 August, German forces began clearing minefields in the eastern Gulf of Finland, though the major warships of the unit remained behind in Kiel. Four days later, Boedicker and his staff moved to , which sailed that day in company with , bound for Libau. The ships then continued on to Reval, Helsingfors, Narva, Narva-Jõesuu, Hungerburg, and Primorsk, Leningrad Oblast, Björkö. The wartime situation continued to deteriorate for Germany, which led to the postponement of Operation Schlußstein, and was soon recalled. She passed through Helsingfors, Reval, and Libau before arriving back in Kiel. She then returned to the North Sea, arriving in Wilhelmshaven on 9 September, where Boedicker and his staff left the ship. On 12 September, returned to the Baltic and sailed back east, arriving in Björkö to relieve as the guardship there on 16 September. She remained there for more than a month, during which time Operation Schlußstein was formally cancelled on 27 September. By that time, Germany's position in the Balkans began to collapse after the Vardar offensive on the Macedonian front inflicted a decisive defeat on German and Bulgarian forces. On 22 October, the old coastal defense ship arrived to replace , which departed for Helsingfors. She spent the last weeks of the war there, after which she returned to Kiel, where she was decommissioned on 17 December.Postwar and French service

After the war, was not included in the fleet that was interned at Scapa Flow during the peace negotiations. She was instead permitted to remain in Germany, and the naval command hoped that she could be preserved for the postwar . But after the scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow in June 1919, shortly before the Treaty of Versailles was signed, this proved to be an unrealistic expectation. The Treaty of Versailles specified that the ship was to be disarmed and handed over to the Allies within two months of the signing of the treaty.See: s:Treaty of Versailles 1919, Treaty of Versailles Section II: Naval Clauses, Article 185 was accordingly struck from the naval register on 5 November 1919. She was ceded to France as a war prize under the transaction name "Z". Departing Germany on 28 July 1920 in company with the torpedo boat , the ships arrived in Cherbourg, France, on 3 August. There, she was formally handed that day.

On arriving in France, she underwent a minor refit that consisted primarily of replacing her 8.8 cm guns with anti-aircraft guns, though the rest of her original armament remained. She was renamed in honor of the Mulhouse, eponymous city in Alsace that had been recovered from Germany at the end of World War I. She and four other ex-German or ex-Austro-Hungarian cruisers were commissioned into the

After the war, was not included in the fleet that was interned at Scapa Flow during the peace negotiations. She was instead permitted to remain in Germany, and the naval command hoped that she could be preserved for the postwar . But after the scuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow in June 1919, shortly before the Treaty of Versailles was signed, this proved to be an unrealistic expectation. The Treaty of Versailles specified that the ship was to be disarmed and handed over to the Allies within two months of the signing of the treaty.See: s:Treaty of Versailles 1919, Treaty of Versailles Section II: Naval Clauses, Article 185 was accordingly struck from the naval register on 5 November 1919. She was ceded to France as a war prize under the transaction name "Z". Departing Germany on 28 July 1920 in company with the torpedo boat , the ships arrived in Cherbourg, France, on 3 August. There, she was formally handed that day.

On arriving in France, she underwent a minor refit that consisted primarily of replacing her 8.8 cm guns with anti-aircraft guns, though the rest of her original armament remained. She was renamed in honor of the Mulhouse, eponymous city in Alsace that had been recovered from Germany at the end of World War I. She and four other ex-German or ex-Austro-Hungarian cruisers were commissioned into the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

in the early 1920s. was commissioned on 3 August 1922.

was assigned to the French Mediterranean Fleet as part of the 3rd Light Division in company with the other ex-German cruisers and and the ex-Austro-Hungarian . The unit, which was renamed the 2nd Light Division in December 1926, was moved to the Atlantic in August 1928, though all of the ex-German and ex-Austro-Hungarian vessels were then placed in reserve fleet, reserve, since the first generation of post-war cruisers were entering service in the French fleet. and the other old ships were first stationed in Brest, France, Brest, but were moved to the Landévennec in 1930. As the French fleet completed additional cruisers, it no longer had a need to keep in reserve, and she was struck from the naval register on 15 February 1933. She was sold to ship breakers in September, and was broken up in Brest by 1935. The ship's bell was later returned to Germany and is now on display at the Laboe Naval Memorial.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Stralsund Magdeburg-class cruisers Ships built in Bremen (state) 1911 ships World War I cruisers of Germany Magdeburg-class cruisers of the French Navy, Mulhouse