Renaissance music on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Renaissance music is traditionally understood to cover European music of the 15th and 16th centuries, later than the

Renaissance music is traditionally understood to cover European music of the 15th and 16th centuries, later than the

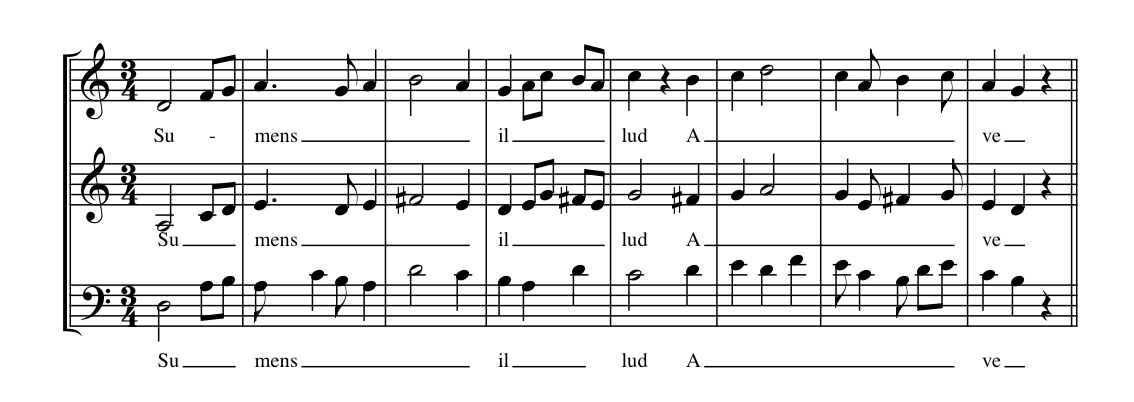

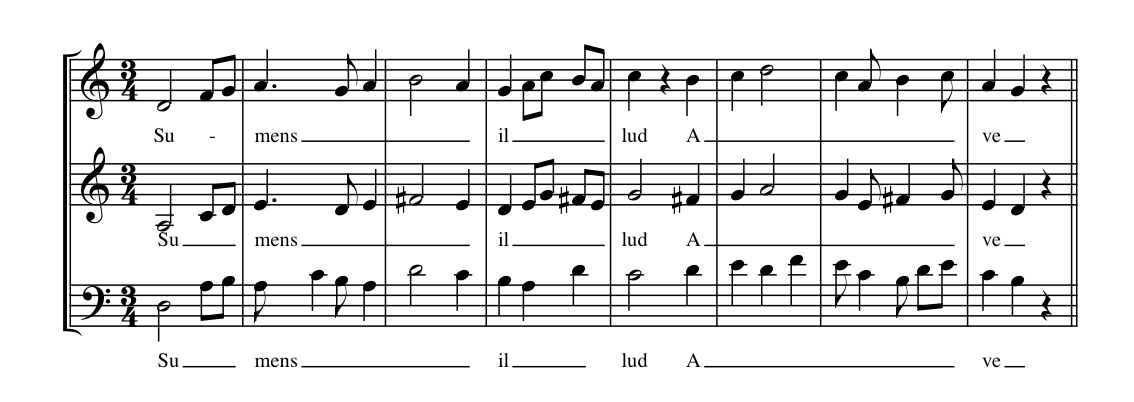

Many of Du Fay's compositions were simple settings of chant, obviously designed for liturgical use, probably as substitutes for the unadorned chant, and can be seen as chant harmonizations. Often the harmonization used a technique of parallel writing known as

Many of Du Fay's compositions were simple settings of chant, obviously designed for liturgical use, probably as substitutes for the unadorned chant, and can be seen as chant harmonizations. Often the harmonization used a technique of parallel writing known as

Many instruments originated during the Renaissance; others were variations of, or improvements upon, instruments that had existed previously. Some have survived to the present day; others have disappeared, only to be recreated in order to perform music of the period on authentic instruments. As in the modern day, instruments may be classified as brass, strings, percussion, and woodwind.

Medieval instruments in Europe had most commonly been used singly, often self-accompanied with a drone, or occasionally in parts. From at least as early as the 13th century through the 15th century there was a division of instruments into ''haut'' (loud, shrill, outdoor instruments) and ''bas'' (quieter, more intimate instruments). Only two groups of instruments could play freely in both types of ensembles: the

Many instruments originated during the Renaissance; others were variations of, or improvements upon, instruments that had existed previously. Some have survived to the present day; others have disappeared, only to be recreated in order to perform music of the period on authentic instruments. As in the modern day, instruments may be classified as brass, strings, percussion, and woodwind.

Medieval instruments in Europe had most commonly been used singly, often self-accompanied with a drone, or occasionally in parts. From at least as early as the 13th century through the 15th century there was a division of instruments into ''haut'' (loud, shrill, outdoor instruments) and ''bas'' (quieter, more intimate instruments). Only two groups of instruments could play freely in both types of ensembles: the

Pandora Radio: Renaissance Period

Ancient FM

(online radio featuring medieval and renaissance music)

nbsp;– descriptions, photos, and sounds.

Renaissance Period Music

Collection of music from 5 countries

"The Renaissance Channel"

– Renaissance Music Videos

– Medieval, Renaissance, Modern Classical music

Répertoire International des Sources Musicales (RISM)

a free, searchable database of worldwide locations for music manuscripts up to c. 1800

WQXR: Renaissance Notation Knives

;Modern performance

City of Lincoln Waites

''The Mayor of Lincoln's Own Band of Musick''

Pantagruel

nbsp;– A Renaissance Musicke Ensemble

Stella Fortuna: Medieval Minstrels (1370)

''from Ye Compaynye of Cheualrye Re-enactment Society. Photos and Audio Download.''

The Waits Website

nbsp;– Renaissance Civic Bands of Europe

Ensemble Feria VI

nbsp;– Six voices and a viola da gamba {{DEFAULTSORT:Renaissance Music

Renaissance music is traditionally understood to cover European music of the 15th and 16th centuries, later than the

Renaissance music is traditionally understood to cover European music of the 15th and 16th centuries, later than the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

era as it is understood in other disciplines. Rather than starting from the early 14th-century ''ars nova

''Ars nova'' ()Fallows, David. (2001). "Ars nova". ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan. refers to a musical style which flourished in the Kingdom of ...

'', the Trecento music was treated by musicology

Musicology is the academic, research-based study of music, as opposed to musical composition or performance. Musicology research combines and intersects with many fields, including psychology, sociology, acoustics, neurology, natural sciences, ...

as a coda to medieval music

Medieval music encompasses the sacred music, sacred and secular music of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. It is the Dates of classical music eras, first and longest major era of Western class ...

and the new era dated from the rise of triadic harmony and the spread of the ''contenance angloise

The ''Contenance angloise'', or English manner, a distinctive style of musical polyphony, developed in History of England, fifteenth-century England. It uses full, rich harmonies based on the Interval (music) , third and sixth. It became highly in ...

'' style from the British Isles to the Burgundian School

The Burgundian School was a group of composers active in the 15th century in what is now northern and eastern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, centered on the court of the Dukes of Burgundy. The school inaugurated the music of Burgundy.

Th ...

. A convenient watershed for its end is the adoption of basso continuo

Basso continuo parts, almost universal in the Baroque era (1600–1750), provided the harmonic structure of the music by supplying a bassline and a chord progression. The phrase is often shortened to continuo, and the instrumentalists playing th ...

at the beginning of the Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

period.

The period may be roughly subdivided, with an early period corresponding to the career of Guillaume Du Fay

Guillaume Du Fay ( , ; also Dufay, Du Fayt; 5 August 1397 – 27 November 1474) was a composer and music theorist of early Renaissance music, who is variously described as French or Franco-Flemish. Considered the leading European composer of h ...

(–1474) and the cultivation of cantilena style, a middle dominated by Franco-Flemish School

The designation Franco-Flemish School, also called Netherlandish School, Burgundian School, Low Countries School, Flemish School, Dutch School, or Northern School, refers to the style of polyphonic vocal music composition originating from Franc ...

and the four-part textures favored by Johannes Ockeghem

Johannes Ockeghem ( – 6 February 1497) was a Franco-Flemish composer and singer of early Renaissance music. Ockeghem was a significant European composer in the period between Guillaume Du Fay and Josquin des Prez, and he was—with his colle ...

(1410s or '20s–1497) and Josquin des Prez

Josquin Lebloitte dit des Prez ( – 27 August 1521) was a composer of High Renaissance music, who is variously described as French or Franco-Flemish. Considered one of the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he was a central figure of the ...

(late 1450s–1521), and culminating during the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

in the florid counterpoint

In music theory, counterpoint is the relationship of two or more simultaneous musical lines (also called voices) that are harmonically dependent on each other, yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. The term originates from the Latin ...

of Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; , ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Prenestina. It is built upon ...

(–1594) and the Roman School.

Music was increasingly freed from medieval constraints, and more variety was permitted in range, rhythm, harmony, form, and notation. On the other hand, rules of counterpoint

In music theory, counterpoint is the relationship of two or more simultaneous musical lines (also called voices) that are harmonically dependent on each other, yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. The term originates from the Latin ...

became more constrained, particularly with regard to treatment of dissonances. In the Renaissance, music became a vehicle for personal expression. Composers found ways to make vocal music more expressive of the texts they were setting. Secular music

Non-religious secular music and Religious music, sacred music were the two main genres of Western world, Western music during the Middle Ages and Renaissance music, Renaissance era. The oldest written examples of secular music are songs with Lat ...

absorbed techniques from sacred music

Religious music (also sacred music) is a type of music that is performed or composed for religious use or through religious influence. It may overlap with ritual music, which is music, sacred or not, performed or composed for or as a ritual. Reli ...

, and vice versa. Popular secular forms such as the chanson and madrigal

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance (15th–16th centuries) and early Baroque (1580–1650) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the ...

spread throughout Europe. Courts employed virtuoso performers, both singers and instrumentalists. Music also became more self-sufficient with its availability in printed form, existing for its own sake.

Precursor versions of many familiar modern instruments (including the violin, guitar, lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck (music), neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lu ...

and keyboard instruments) developed into new forms during the Renaissance. These instruments were modified to respond to the evolution of musical ideas, and they presented new possibilities for composers and musicians to explore. Early forms of modern woodwind and brass instruments like the bassoon

The bassoon is a musical instrument in the woodwind family, which plays in the tenor and bass ranges. It is composed of six pieces, and is usually made of wood. It is known for its distinctive tone color, wide range, versatility, and virtuosity ...

and trombone

The trombone (, Italian, French: ''trombone'') is a musical instrument in the Brass instrument, brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's lips vibrate inside a mouthpiece, causing the Standing wave, air c ...

also appeared, extending the range of sonic color and increasing the sound of instrumental ensembles. During the 15th century, the sound of full triads became common, and towards the end of the 16th century the system of church mode

A Gregorian mode (or church mode) is one of the eight systems of pitch organization used in Gregorian chant.

History

The name of Pope Gregory I was attached to the variety of chant that was to become the dominant variety in medieval western and ...

s began to break down entirely, giving way to functional tonality (the system in which songs and pieces are based on musical "keys"), which would dominate Western art music for the next three centuries.

From the Renaissance era, notated secular and sacred music survives in quantity, including vocal and instrumental works and mixed vocal/instrumental works. A wide range of musical styles and genres flourished during the Renaissance, including masses, motets, madrigals, chansons, accompanied songs, instrumental dances, and many others. Beginning in the late 20th century, numerous early music

Early music generally comprises Medieval music (500–1400) and Renaissance music (1400–1600), but can also include Baroque music (1600–1750) or Ancient music (before 500 AD). Originating in Europe, early music is a broad Dates of classical ...

ensembles were formed. Ensembles specializing in music of the Renaissance era give concert tours and make recordings, using modern reproductions of historical instruments and using singing and performing styles which musicologist

Musicology is the academic, research-based study of music, as opposed to musical composition or performance. Musicology research combines and intersects with many fields, including psychology, sociology, acoustics, neurology, natural sciences, f ...

s believe were used during the era.

Overview

The main characteristics of Renaissance music are: * Music based on modes. * Rich texture, with four or more independent melodic parts being performed simultaneously. These interweaving melodic lines, a style calledpolyphony

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice ( monophony) or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chord ...

, is one of the defining features of Renaissance music.

* Blending, rather than contrasting, melodic lines in the musical texture.

* Harmony that placed a greater concern on the smooth flow of the music and its progression of chords.

The development of polyphony produced the notable changes in musical instruments that mark the Renaissance musically from the Middle Ages. Its use encouraged the development of larger ensembles and demanded sets of instruments that would blend together across the whole vocal range.

One of the most pronounced features of early Renaissance European art music was the increasing reliance on the interval of the third and its inversion, the sixth. (In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, thirds and sixths had been considered dissonances; and consonances were derived only of the perfect intervals: the perfect fourth

A fourth is a interval (music), musical interval encompassing four staff positions in the music notation of Western culture, and a perfect fourth () is the fourth spanning five semitones (half steps, or half tones). For example, the ascending int ...

, the perfect fifth

In music theory, a perfect fifth is the Interval (music), musical interval corresponding to a pair of pitch (music), pitches with a frequency ratio of 3:2, or very nearly so.

In classical music from Western culture, a fifth is the interval f ...

, the octave

In music, an octave (: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is an interval between two notes, one having twice the frequency of vibration of the other. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been referr ...

, and the unison

Unison (stylised as UNISON) is a Great Britain, British trade union. Along with Unite the Union, Unite, Unison is one of the two largest trade unions in the United Kingdom, with over 1.2 million members who work predominantly in public servic ...

). Polyphony

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice ( monophony) or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chord ...

—the use of multiple, independent melodic lines played simultaneously—became increasingly elaborate throughout the 14th century, with highly independent voices in both vocal music and instrumental music. The beginning of the 15th century showed simplification, with the composers often striving for smoothness in the melodic parts. This was possible because of a greatly increased vocal range in music. Previously, in the Middle Ages, the narrow vocal range necessitated frequent crossing of parts, thus requiring a greater contrast between them to distinguish the different parts.

The modal character of Renaissance music—later replaced by the tonal approach developing in the subsequent Baroque music

Baroque music ( or ) refers to the period or dominant style of Classical music, Western classical music composed from about 1600 to 1750. The Baroque style followed the Renaissance music, Renaissance period, and was followed in turn by the Class ...

era—began to break down towards the end of the (Renaissance) period with the increased use of root motions of fifths or fourths; (see Circle of fifths

In music theory, the circle of fifths (sometimes also cycle of fifths) is a way of organizing pitches as a sequence of perfect fifths. Starting on a C, and using the standard system of tuning for Western music (12-tone equal temperament), the se ...

for details). An example of a chord progression

In a musical composition, a chord progression or harmonic progression (informally chord changes, used as a plural, or simply changes) is a succession of chords. Chord progressions are the foundation of harmony in Western musical tradition from ...

in which the chord roots move by the interval of a fourth is the chord progression in the key of C Major: "D minor/G Major/C Major"—these are all triads; three-note chords. The movement from the D minor chord to the G Major chord is an interval of a perfect fourth. The movement from the G Major chord to the C Major chord is also an interval of a perfect fourth. This later developed into one of the defining characteristics of tonality during the Baroque era.

Background

As in the other arts, the music of the period was significantly influenced by the developments which define theEarly Modern

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

period: the rise of humanistic

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

thought; the recovery of the literary and artistic heritage of Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

and Ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

; increased innovation and discovery; the growth of commercial enterprises; the rise of a bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

class; and the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

. From this changing society emerged a common, unifying musical language, in particular, the polyphonic

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice ( monophony) or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords ...

style of the Franco-Flemish school

The designation Franco-Flemish School, also called Netherlandish School, Burgundian School, Low Countries School, Flemish School, Dutch School, or Northern School, refers to the style of polyphonic vocal music composition originating from Franc ...

.

The invention of the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

in 1439 made it cheaper and easier to distribute music and music theory texts on a wider geographic scale and to more people. Prior to the invention of printing, written music and music theory texts had to be hand-copied, a time-consuming and expensive process. Demand for music as entertainment and as a leisure activity for educated amateurs increased with the emergence of a bourgeois class. Dissemination of chanson

A (, ; , ) is generally any Lyrics, lyric-driven French song. The term is most commonly used in English to refer either to the secular polyphonic French songs of late medieval music, medieval and Renaissance music or to a specific style of ...

s, motet

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the preeminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to the Eng ...

s, and masses throughout Europe coincided with the unification of polyphonic practice into the fluid style which culminated in the second half of the sixteenth century in the work of composers such as Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (between 3 February 1525 and 2 February 1526 – 2 February 1594) was an Italian composer of late Renaissance music. The central representative of the Roman School, with Orlande de Lassus and Tomás Luis de V ...

, Orlande de Lassus

Orlando di Lasso ( various other names; probably – 14 June 1594) was a composer of the late Renaissance. The chief representative of the mature polyphonic style in the Franco-Flemish school, Lassus stands with William Byrd, Giovanni Pierlui ...

, Thomas Tallis

Thomas Tallis (; also Tallys or Talles; 23 November 1585) was an English composer of High Renaissance music. His compositions are primarily vocal, and he occupies a primary place in anthologies of English choral music. Tallis is considered one ...

, William Byrd

William Byrd (; 4 July 1623) was an English Renaissance composer. Considered among the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he had a profound influence on composers both from his native country and on the Continental Europe, Continent. He i ...

and Tomás Luis de Victoria

Tomás Luis de Victoria (sometimes Italianised as ''da Vittoria''; ) was the most famous Spanish composer of the Renaissance. He stands with Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and Orlande de Lassus as among the principal composers of the late Re ...

. Relative political stability and prosperity in the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

, along with a flourishing system of music education

Music education is a field of practice in which educators are trained for careers as primary education, elementary or secondary education, secondary music teachers, school or music conservatory ensemble directors. Music education is also a rese ...

in the area's many churches and cathedrals allowed the training of large numbers of singers, instrumentalists, and composers. These musicians were highly sought throughout Europe, particularly in Italy, where churches and aristocratic courts hired them as composers, performers, and teachers. Since the printing press made it easier to disseminate printed music, by the end of the 16th century, Italy had absorbed the northern musical influences with Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, Rome, and other cities becoming centers of musical activity. This reversed the situation from a hundred years earlier. Opera, a dramatic staged genre in which singers are accompanied by instruments, arose at this time in Florence. Opera was developed as a deliberate attempt to resurrect the music of ancient Greece.

Genres

Principal liturgical (church-based) musical forms, which remained in use throughout the Renaissance period, were masses andmotet

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the preeminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to the Eng ...

s, with some other developments towards the end of the era, especially as composers of sacred music

Religious music (also sacred music) is a type of music that is performed or composed for religious use or through religious influence. It may overlap with ritual music, which is music, sacred or not, performed or composed for or as a ritual. Reli ...

began to adopt secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

(non-religious) musical forms (such as the madrigal

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance (15th–16th centuries) and early Baroque (1580–1650) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the ...

) for religious use. The 15th and 16th century masses had two kinds of sources that were used: monophonic (a single melody line) and polyphonic

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice ( monophony) or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords ...

(multiple, independent melodic lines), with two main forms of elaboration, based on ''cantus firmus

In music, a ''cantus firmus'' ("fixed melody") is a pre-existing melody forming the basis of a polyphonic composition.

The plural of this Latin term is , although the corrupt form ''canti firmi'' (resulting from the grammatically incorrect trea ...

'' practice or, beginning some time around 1500, the new style of "pervasive imitation", in which composers would write music in which the different voices or parts would imitate the melodic and/or rhythmic motifs performed by other voices or parts. Several main types of masses were used:

* Cyclic mass In Renaissance music, the cyclic mass was a musical setting of the Ordinary of the Roman Catholic Mass, in which each of the movements – Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei – shared a common musical theme, commonly a cantus ...

(tenor mass)

* Paraphrase mass

* Imitation mass

Masses were normally titled by the source from which they borrowed. ''Cantus firmus

In music, a ''cantus firmus'' ("fixed melody") is a pre-existing melody forming the basis of a polyphonic composition.

The plural of this Latin term is , although the corrupt form ''canti firmi'' (resulting from the grammatically incorrect trea ...

'' mass uses the same monophonic melody, usually drawn from chant and usually in the tenor and most often in longer note values than the other voices. Other sacred genres were the madrigale spirituale and the laude.

During the period, secular (non-religious) music had an increasing distribution, with a wide variety of forms, but one must be cautious about assuming an explosion in variety: since printing made music more widely available, much more has survived from this era than from the preceding medieval era, and probably a rich store of popular music of the late Middle Ages is lost. Secular music was music that was independent of churches. The main types were the German Lied

In the Western classical music tradition, ( , ; , ; ) is a term for setting poetry to classical music. The term is used for any kind of song in contemporary German and Dutch, but among English and French speakers, is often used interchangea ...

, Italian frottola

The frottola (; plural frottole) was the predominant type of Italian popular secular song of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century. It was the most important and widespread predecessor to the madrigal. The peak of activity in composit ...

, the French chanson

A (, ; , ) is generally any Lyrics, lyric-driven French song. The term is most commonly used in English to refer either to the secular polyphonic French songs of late medieval music, medieval and Renaissance music or to a specific style of ...

, the Italian madrigal

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance (15th–16th centuries) and early Baroque (1580–1650) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the ...

, and the Spanish villancico

The ''villancico'' ( Spanish, ) or vilancete ( Portuguese, ) was a common poetic and musical form of the Iberian Peninsula and Latin America popular from the late 15th to 18th centuries. Important composers of villancicos were Juan del Encina, P ...

. Other secular vocal genres included the caccia, rondeau, virelai

A ''virelai'' is a form of medieval French verse used often in poetry and music. It is one of the three '' formes fixes'' (the others were the ballade and the rondeau) and was one of the most common verse forms set to music in Europe from the ...

, bergerette

A bergerette, or shepherdess' air, is a form of early rustic French song.

The bergerette, developed by Burgundian composers, is a virelai with only one stanza. It is one of the "fixed forms" of early French song and related to the rondeau. Exam ...

, ballade, musique mesurée, canzonetta, villanella, villotta, and the lute song. Mixed forms such as the motet-chanson The motet-chanson was a specialized musical form of the Renaissance, developed in Milan during the 1470s and 1480s, which combined aspects of the contemporary motet and chanson.

Many consisted of three voice parts, with the lowest voice, a tenor ...

and the secular motet also appeared.

Purely instrumental music included consort __NOTOC__

Consort may refer to:

Music

* "The Consort" (Rufus Wainwright song), from the 2000 album ''Poses''

* Consort of instruments, term for instrumental ensembles

* Consort song (musical), a characteristic English song form, late 16th–earl ...

music for recorders or viol

The viola da gamba (), or viol, or informally gamba, is a bowed and fretted string instrument that is played (i.e. "on the leg"). It is distinct from the later violin family, violin, or ; and it is any one of the earlier viol family of bow (m ...

s and other instruments, and dances for various ensembles. Common instrumental genres were the toccata

Toccata (from Italian ''toccare'', literally, "to touch", with "toccata" being the action of touching) is a virtuoso piece of music typically for a keyboard or plucked string instrument featuring fast-moving, lightly fingered or otherwise virt ...

, prelude, ricercar

A ricercar ( , ) or ricercare ( , ) is a type of late Renaissance and mostly early Baroque instrumental composition. The term ''ricercar'' derives from the Italian verb , which means "to search out; to seek"; many ricercars serve a preludial func ...

, and canzona

The canzona, also known as the canzon or canzone, is an Italian musical form derived from the Franco-Flemish and Parisian '' chansons''.

Background

The canzona is an instrumental musical form that differs from the similar forms of ricercare ...

. Dances played by instrumental ensembles (or sometimes sung) included the basse danse

The ''basse danse'', or "low dance", was a popular court dance in the 15th and early 16th centuries, especially at the Duchy of Burgundy, Burgundian court. The word ''basse'' describes the nature of the dance, in which partners move quietly and ...

(It. ''bassadanza''), tourdion, saltarello

The ''saltarello'' is a musical dance originally from Italy. The first mention of it is in Add MS 29987, a late-fourteenth- or early fifteenth-century manuscript of Tuscany, Tuscan origin, now in the British Library. It was usually played in a f ...

, pavane

The ''pavane'' ( ; , ''padovana''; ) is a slow processional dance common in Europe during the 16th century (Renaissance).

The pavane, the earliest-known music for which was published in Venice by Ottaviano Petrucci, in Joan Ambrosio Dalza's ...

, galliard

The ''galliard'' (; ; ) was a form of Renaissance dance and Renaissance music, music popular all over Europe in the 16th century. It is mentioned in dance manuals from England, Portugal, France, Spain, Germany, and Italy.

Dance form

The ''gal ...

, allemande

An ''allemande'' (''allemanda'', ''almain(e)'', or ''alman(d)'', French: "German (dance)") is a Renaissance and Baroque dance, and one of the most common instrumental dance styles in Baroque music, with examples by Couperin, Purcell, Bach ...

, courante

The ''courante'', ''corrente'', ''coranto'' and ''corant'' are some of the names given to a family of triple metre dances from the late Renaissance and the Baroque era. In a Baroque dance suite an Italian or French courante is typically pair ...

, bransle

A branle ( , ), also bransle, brangle, brawl(e), brall(e), braul(e), brando (in Italy), bran (in Spain), or brantle (in Scotland), is a type of France, French dance popular from the early 16th century to the present, danced by couples in either ...

, canarie

CANARIE (formerly the Canadian Network for the Advancement of Research, Industry and Education) is the not-for-profit organisation which operates the national backbone network of Canada's national research and education network (NREN). The org ...

, piva, and lavolta

The volta (plural: voltas) (Italian: "the turn" or "turning") is an anglicised name for a dance for couples that was popular during the later Renaissance period. This dance was associated with the galliard and done to the same kind of music. Its ...

. Music of many genres could be arranged for a solo instrument such as the lute, vihuela, harp, or keyboard. Such arrangements were called intabulations (It. ''intavolatura'', Ger. ''Intabulierung'').

Towards the end of the period, the early dramatic precursors of opera such as monody

In music, monody refers to a solo vocal style distinguished by having a single melody, melodic line and instrumental accompaniment. Although such music is found in various cultures throughout history, the term is specifically applied to Italy, ...

, the madrigal comedy, and the intermedio are heard.

Theory and notation

According to Margaret Bent: "Renaissancenotation

In linguistics and semiotics, a notation system is a system of graphics or symbols, Character_(symbol), characters and abbreviated Expression (language), expressions, used (for example) in Artistic disciplines, artistic and scientific disciplines ...

is under-prescriptive by our odernstandards; when translated into modern form it acquires a prescriptive weight that overspecifies and distorts its original openness". Renaissance compositions were notated only in individual parts; scores were extremely rare, and barlines were not used. Note value

In music notation, a note value indicates the relative duration (music), duration of a note (music), note, using the texture or shape of the ''notehead'', the presence or absence of a ''stem (music), stem'', and the presence or absence of ''flags ...

s were generally larger than are in use today; the primary unit of beat was the semibreve

A whole note (American) or semibreve (British) in musical notation is a single note equivalent to or lasting as long as two half notes or four quarter notes. Description

The whole note or semibreve has a note head in the shape of a hollow o ...

, or whole note

A whole note (American) or semibreve (British) in musical notation is a single note equivalent to or lasting as long as two half notes or four quarter notes. Description

The whole note or semibreve has a note head in the shape of a hollow ov ...

. As had been the case since the Ars Nova

''Ars nova'' ()Fallows, David. (2001). "Ars nova". ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan. refers to a musical style which flourished in the Kingdom of ...

(see Medieval music

Medieval music encompasses the sacred music, sacred and secular music of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. It is the Dates of classical music eras, first and longest major era of Western class ...

), there could be either two or three of these for each breve

A breve ( , less often , grammatical gender, neuter form of the Latin "short, brief") is the diacritic mark , shaped like the bottom half of a circle. As used in Ancient Greek, it is also called , . It resembles the caron (, the wedge or in ...

(a double-whole note), which may be looked on as equivalent to the modern "measure," though it was itself a note value and a measure is not. The situation can be considered this way: it is the same as the rule by which in modern music a quarter-note may equal either two eighth-notes or three, which would be written as a "triplet." By the same reckoning, there could be two or three of the next smallest note, the "minim," (equivalent to the modern "half note") to each semibreve.

These different permutations were called "perfect/imperfect tempus" at the level of the breve–semibreve relationship, "perfect/imperfect prolation" at the level of the semibreve–minim, and existed in all possible combinations with each other. Three-to-one was called "perfect," and two-to-one "imperfect." Rules existed also whereby single notes could be halved or doubled in value ("imperfected" or "altered," respectively) when preceded or followed by other certain notes. Notes with black noteheads (such as quarter note

A quarter note ( AmE) or crotchet ( BrE) () is a musical note played for one quarter of the duration of a whole note (or semibreve). Quarter notes are notated with a filled-in oval note head and a straight, flagless stem. The stem usually ...

s) occurred less often. This development of white mensural notation

Mensural notation is the musical notation system used for polyphony, polyphonic European vocal music from the late 13th century until the early 17th century. The term "mensural" refers to the ability of this system to describe precisely measur ...

may be a result of the increased use of paper (rather than vellum

Vellum is prepared animal skin or membrane, typically used as writing material. It is often distinguished from parchment, either by being made from calfskin (rather than the skin of other animals), or simply by being of a higher quality. Vellu ...

), as the weaker paper was less able to withstand the scratching required to fill in solid noteheads; notation of previous times, written on vellum, had been black. Other colors, and later, filled-in notes, were used routinely as well, mainly to enforce the aforementioned imperfections or alterations and to call for other temporary rhythmical changes.

Accidentals (e.g. added sharps, flats and naturals that change the notes) were not always specified, somewhat as in certain fingering notations for guitar-family instruments (tablature

Tablature (or tab for short) is a form of musical notation indicating instrument fingering or the location of the played notes rather than musical pitches.

Tablature is common for fretted stringed instruments such as the guitar, lute or vihuel ...

s) today. However, Renaissance musicians would have been highly trained in dyadic counterpoint and thus possessed this and other information necessary to read a score correctly, even if the accidentals were not written in. As such, "what modern notation requires ccidentalswould then have been perfectly apparent without notation to a singer versed in counterpoint." (See musica ficta

''Musica ficta'' (from Latin, "false", "feigned", or "fictitious" music) was a term used in European music theory from the late 12th century to about 1600 to describe pitches, whether notated or added at the time of performance, that lie outside ...

.) A singer would interpret his or her part by figuring cadential formulas with other parts in mind, and when singing together, musicians would avoid parallel octaves and parallel fifths or alter their cadential parts in light of decisions by other musicians. It is through contemporary tablatures for various plucked instruments that we have gained much information about which accidentals were performed by the original practitioners.

For information on specific theorists, see Johannes Tinctoris

Jehan le Taintenier or Jean Teinturier (Latinised as Johannes Tinctoris; also Jean de Vaerwere; – 1511) was a Renaissance music, Renaissance music theory, music theorist and composer from the Franco-Flemish School, Low Countries. Up to his ...

, Franchinus Gaffurius, Heinrich Glarean, Pietro Aron, Nicola Vicentino

Nicola Vicentino (1511 – 1575 or 1576) was an Italian music theory, music theorist and composer of the Renaissance music, Renaissance. He was one of the most progressive musicians of the age, inventing, among other things, a microtonal keyb ...

, Tomás de Santa María

Fr. Tomás de Santa María O.P. (also Tomás de Sancta Maria) (ca. 1510 – 1570) was a Spanish music theorist, organist and composer of the Renaissance music, Renaissance. He was born in Madrid but the date is highly uncertain; he died in Ri ...

, Gioseffo Zarlino

Gioseffo Zarlino (31 January or 22 March 1517 – 4 February 1590) was an Italian Music theory, music theorist and composer of the Renaissance music, Renaissance. He made a large contribution to the theory of counterpoint as well as to musical t ...

, Vicente Lusitano, Vincenzo Galilei

Vincenzo Galilei (3 April 1520 – 2 July 1591) was an Italian lutenist, composer, and music theory, music theorist. His children included the astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei and the lute virtuoso and composer Michelagnolo Galilei. Vinc ...

, Giovanni Artusi

Giovanni Maria Artusi (c. 154018 August 1613) was an Italian music theory, music theorist, composer, and writer.

Artusi fiercely condemned the new musical innovations that defined the early Baroque music, Baroque style developing around 1600 in h ...

, Johannes Nucius

Johannes Nucius (also Nux, Nucis) (c. 1556 – March 25, 1620) was a German composer and music theory, music theorist of the late Renaissance music, Renaissance and early Baroque music, Baroque eras. Although isolated from most of the major cente ...

, and Pietro Cerone.

Composers – timeline

Early period (1400–1470)

The key composers from the early Renaissance era also wrote in a late medieval style, and as such, they are transitional figures. Leonel Power (c. 1370s or 1380s–1445) was an English composer of the latemedieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

and early Renaissance music eras. Along with John Dunstaple

John Dunstaple (or Dunstable; – 24 December 1453) was an English composer whose music helped inaugurate the transition from the medieval to the Renaissance periods. The central proponent of the ''Contenance angloise'' style (), Dunstaple was ...

, he was one of the major figures in English music in the early 15th century. Power is the composer best represented in the '' Old Hall Manuscript'', one of the only undamaged sources of English music from the early 15th century. He was one of the first composers to set separate movements of the ordinary of the mass

The ordinary, in Catholic liturgy, Catholic liturgies, refers to the part of the Mass (liturgy), Mass or of the canonical hours that is reasonably constant without regard to the date on which the service is performed. It is contrasted with the ' ...

which were thematically unified and intended for contiguous performance. The Old Hall Manuscript contains his mass based on the Marian antiphon, Alma Redemptoris Mater

"Alma Redemptoris Mater" (; "Loving Mother of our Redeemer") is a Marian hymn, written in Latin hexameter, and one of four seasonal liturgical Marian antiphons sung at the end of the Liturgy of the Hours, office of Compline (the other three bein ...

, in which the antiphon is stated literally in the tenor voice in each movement, without melodic ornaments. This is the only cyclic setting of the mass ordinary which can be attributed to him. He wrote mass cycles, fragments, and single movements and a variety of other sacred works.

John Dunstaple

John Dunstaple (or Dunstable; – 24 December 1453) was an English composer whose music helped inaugurate the transition from the medieval to the Renaissance periods. The central proponent of the ''Contenance angloise'' style (), Dunstaple was ...

(c. 1390–1453) was an English composer of polyphonic

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice ( monophony) or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords ...

music of the late medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

era and early Renaissance periods. He was one of the most famous composers active in the early 15th century, a near-contemporary of Power, and was widely influential, not only in England but on the continent, especially in the developing style of the Burgundian School

The Burgundian School was a group of composers active in the 15th century in what is now northern and eastern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, centered on the court of the Dukes of Burgundy. The school inaugurated the music of Burgundy.

Th ...

.

Dunstaple's influence on the continent's musical vocabulary was enormous, particularly considering the relative paucity of his (attributable) works. He was recognized for possessing something never heard before in music of the Burgundian School

The Burgundian School was a group of composers active in the 15th century in what is now northern and eastern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, centered on the court of the Dukes of Burgundy. The school inaugurated the music of Burgundy.

Th ...

: '' la contenance angloise'' ("the English countenance"), a term used by the poet Martin le Franc

Martin le Franc ( – 1461) was a French poet of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance.

Life and career

He was born in Normandy, and studied in Paris. He entered clerical orders, becoming an prothonotary, apostolic prothonotary, and later bec ...

in his ''Le Champion des Dames.'' Le Franc added that the style influenced Dufay and Binchois. Writing a few decades later in about 1476, the Flemish composer and music theorist Tinctoris reaffirmed the powerful influence Dunstaple had, stressing the "new art" that Dunstaple had inspired. Tinctoris hailed Dunstaple as the ''fons et origo'' of the style, its "wellspring and origin."

The ''contenance angloise'', while not defined by Martin le Franc, was probably a reference to Dunstaple's stylistic trait of using full triadic harmony (three note chords), along with a liking for the interval of the third. Assuming that he had been on the continent with the Duke of Bedford, Dunstaple would have been introduced to French ''fauxbourdon

Fauxbourdon (also fauxbordon, and also commonly two words: faux bourdon or faulx bourdon, and in Italian falso bordone) – Music of France, French for ''false drone'' – is a technique of musical harmony, harmonisation used in the late Medieval ...

''; borrowing some of the sonorities, he created elegant harmonies in his own music using thirds and sixths (an example of a third interval is the notes C and E; an example of a sixth interval is the notes C and A). Taken together, these are seen as defining characteristics of early Renaissance music. Many of these traits may have originated in England, taking root in the Burgundian School around the middle of the century.

Because numerous copies of Dunstaple's works have been found in Italian and German manuscripts, his fame across Europe must have been widespread. Of the works attributed to him only about fifty survive, among which are two complete masses, three connected mass sections, fourteen individual mass sections, twelve complete isorhythmic motet

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the preeminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to the Eng ...

s and seven settings of Marian antiphons, such as ''Alma redemptoris Mater

"Alma Redemptoris Mater" (; "Loving Mother of our Redeemer") is a Marian hymn, written in Latin hexameter, and one of four seasonal liturgical Marian antiphons sung at the end of the Liturgy of the Hours, office of Compline (the other three bein ...

'' and '' Salve Regina, Mater misericordiae''. Dunstaple was one of the first to compose masses using a single melody as ''cantus firmus

In music, a ''cantus firmus'' ("fixed melody") is a pre-existing melody forming the basis of a polyphonic composition.

The plural of this Latin term is , although the corrupt form ''canti firmi'' (resulting from the grammatically incorrect trea ...

.'' A good example of this technique is his ''Missa Rex seculorum''. He is believed to have written secular (non-religious) music, but no songs in the vernacular can be attributed to him with any degree of certainty.

Oswald von Wolkenstein

Oswald von Wolkenstein (1376 or 1377 in Pfalzen – August 2, 1445, in Meran) was a poetry, poet, composer and diplomacy, diplomat. In his diplomatic capacity, he traveled through much of Europe to as far as Georgia (country), Georgia (as recoun ...

(c. 1376–1445) is one of the most important composers of the early German Renaissance. He is best known for his well-written melodies, and for his use of three themes: travel, God and sex.

Gilles Binchois

Gilles de Bins dit Binchois (also Binchoys; – 20 September 1460) was a Franco-Flemish composer and singer of early Renaissance music. A central figure of the Burgundian School, Binchois is renowned a melodist and miniaturist; he generally a ...

(–1460) was a Dutch composer, one of the earliest members of the Burgundian school and one of the three most famous composers of the early 15th century. While often ranked behind his contemporaries Guillaume Dufay

Guillaume Du Fay ( , ; also Dufay, Du Fayt; 5 August 1397 – 27 November 1474) was a composer and music theorist of early Renaissance music, who is variously described as French or Franco-Flemish. Considered the leading European composer of h ...

and John Dunstaple by contemporary scholars, his works were still cited, borrowed and used as source material after his death. Binchois is considered to be a fine melodist, writing carefully shaped lines which are easy to sing and memorable. His tunes appeared in copies decades after his death and were often used as sources for mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

composition by later composers. Most of his music, even his sacred music, is simple and clear in outline, sometimes even ascetic (monk-like). A greater contrast between Binchois and the extreme complexity of the '' ars subtilior'' of the prior (fourteenth) century would be hard to imagine. Most of his secular songs are rondeaux, which became the most common song form during the century. He rarely wrote in strophic form

Strophic form – also called verse-repeating form, chorus form, AAA song form, or one-part song form – is a song structure in which all verses or stanzas of the text are sung to the same music. Contrasting song forms include through-composed, ...

, and his melodies are generally independent of the rhyme scheme of the verses they are set to. Binchois wrote music for the court, secular songs of love and chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric language, is an informal and varying code of conduct that developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It is associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood, with knights being members of ...

that met the expectations and satisfied the taste of the Dukes of Burgundy

Burgundy ( ; ; Burgundian: ''Bregogne'') is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. ...

who employed him, and evidently loved his music accordingly. About half of his extant secular music is found in the Oxford Bodleian Library.

Guillaume Du Fay

Guillaume Du Fay ( , ; also Dufay, Du Fayt; 5 August 1397 – 27 November 1474) was a composer and music theorist of early Renaissance music, who is variously described as French or Franco-Flemish. Considered the leading European composer of h ...

(–1474) was a Franco-Flemish composer of the early Renaissance. The central figure in the Burgundian School

The Burgundian School was a group of composers active in the 15th century in what is now northern and eastern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, centered on the court of the Dukes of Burgundy. The school inaugurated the music of Burgundy.

Th ...

, he was regarded by his contemporaries as the leading composer in Europe in the mid-15th century. Du Fay composed in most of the common forms of the day, including masses, motet

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the preeminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to the Eng ...

s, Magnificat

The Magnificat (Latin for "y soulmagnifies he Lord) is a canticle, also known as the Song of Mary or Canticle of Mary, and in the Byzantine Rite as the Ode of the Theotokos (). Its Western name derives from the incipit of its Latin text. This ...

s, hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' d ...

s, simple chant settings in fauxbourdon

Fauxbourdon (also fauxbordon, and also commonly two words: faux bourdon or faulx bourdon, and in Italian falso bordone) – Music of France, French for ''false drone'' – is a technique of musical harmony, harmonisation used in the late Medieval ...

, and antiphon

An antiphon ( Greek ἀντίφωνον, ἀντί "opposite" and φωνή "voice") is a short chant in Christian ritual, sung as a refrain. The texts of antiphons are usually taken from the Psalms or Scripture, but may also be freely compo ...

s within the area of sacred music, and rondeaux, ballades, virelai

A ''virelai'' is a form of medieval French verse used often in poetry and music. It is one of the three '' formes fixes'' (the others were the ballade and the rondeau) and was one of the most common verse forms set to music in Europe from the ...

s and a few other chanson types within the realm of secular music. None of his surviving music is specifically instrumental, although instruments were certainly used for some of his secular music, especially for the lower parts; all of his sacred music is vocal. Instruments may have been used to reinforce the voices in actual performance for almost any of his works. Seven complete masses, 28 individual mass movements, 15 settings of chant used in mass propers, three Magnificats, two Benedicamus Domino settings, 15 antiphon settings (six of them Marian antiphons), 27 hymns, 22 motets (13 of these isorhythm

Isorhythm (from the Greek for "the same rhythm") is a musical technique using a repeating rhythmic pattern, called a ''talea'', in at least one voice part throughout a composition. ''Taleae'' are typically applied to one or more melodic patterns o ...

ic in the more angular, austere 14th-century style which gave way to more melodic, sensuous treble-dominated part-writing with phrases ending in the "under-third" cadence in Du Fay's youth) and 87 chansons definitely by him have survived.

Many of Du Fay's compositions were simple settings of chant, obviously designed for liturgical use, probably as substitutes for the unadorned chant, and can be seen as chant harmonizations. Often the harmonization used a technique of parallel writing known as

Many of Du Fay's compositions were simple settings of chant, obviously designed for liturgical use, probably as substitutes for the unadorned chant, and can be seen as chant harmonizations. Often the harmonization used a technique of parallel writing known as fauxbourdon

Fauxbourdon (also fauxbordon, and also commonly two words: faux bourdon or faulx bourdon, and in Italian falso bordone) – Music of France, French for ''false drone'' – is a technique of musical harmony, harmonisation used in the late Medieval ...

, as in the following example, a setting of the Marian antiphon '' Ave maris stella''. Du Fay may have been the first composer to use the term "fauxbourdon" for this simpler compositional style, prominent in 15th-century liturgical music in general and that of the Burgundian school in particular. Most of Du Fay's secular (non-religious) songs follow the formes fixes ( rondeau, ballade, and virelai), which dominated secular European music of the 14th and 15th centuries. He also wrote a handful of Italian ballate, almost certainly while he was in Italy. As is the case with his motets, many of the songs were written for specific occasions, and many are datable, thus supplying useful biographical information. Most of his songs are for three voices, using a texture dominated by the highest voice; the other two voices, unsupplied with text, were probably played by instruments.

Du Fay was one of the last composers to make use of late-medieval polyphonic structural techniques such as isorhythm

Isorhythm (from the Greek for "the same rhythm") is a musical technique using a repeating rhythmic pattern, called a ''talea'', in at least one voice part throughout a composition. ''Taleae'' are typically applied to one or more melodic patterns o ...

, and one of the first to employ the more mellifluous harmonies, phrasing and melodies characteristic of the early Renaissance. His compositions within the larger genres (masses, motets and chansons) are mostly similar to each other; his renown is largely due to what was perceived as his perfect control of the forms in which he worked, as well as his gift for memorable and singable melody. During the 15th century, he was universally regarded as the greatest composer of his time, an opinion that has largely survived to the present day.

Middle period (1470–1530)

During the 16th century,Josquin des Prez

Josquin Lebloitte dit des Prez ( – 27 August 1521) was a composer of High Renaissance music, who is variously described as French or Franco-Flemish. Considered one of the greatest composers of the Renaissance, he was a central figure of the ...

( – 27 August 1521) gradually acquired the reputation as the greatest composer of the age, his mastery of technique and expression universally imitated and admired. Writers as diverse as Baldassare Castiglione

Baldassare Castiglione, Count of Casatico (; 6 December 1478 – 2 February 1529),Dates of birth and death, and cause of the latter, fro, ''Italica'', Rai International online. was an Italian courtier, diplomat, soldier and a prominent Renaissan ...

and Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

wrote about his reputation and fame.

Late period (1530–1600)

InVenice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, from about 1530 until around 1600, an impressive polychoral style developed, which gave Europe some of the grandest, most sonorous music composed up until that time, with multiple choirs of singers, brass and strings in different spatial locations in the Basilica San Marco di Venezia

The Patriarchal Cathedral Basilica of Saint Mark (), commonly known as St Mark's Basilica (; ), is the cathedral church of the Patriarchate of Venice; it became the episcopal seat of the Patriarch of Venice in 1807, replacing the earlier cathed ...

(see Venetian School). These multiple revolutions spread over Europe in the next several decades, beginning in Germany and then moving to Spain, France, and England somewhat later, demarcating the beginning of what we now know as the Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

musical era.

The Roman School was a group of composers of predominantly church music in Rome, spanning the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. Many of the composers had a direct connection to the Vatican and the papal chapel, though they worked at several churches; stylistically they are often contrasted with the Venetian School of composers, a concurrent movement which was much more progressive. By far the most famous composer of the Roman School is Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. While best known as a prolific composer of masses and motets, he was also an important madrigalist. His ability to bring together the functional needs of the Catholic Church with the prevailing musical styles during the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

period gave him his enduring fame.

The brief but intense flowering of the musical madrigal in England, mostly from 1588 to 1627, along with the composers who produced them, is known as the English Madrigal School

The English Madrigal School was the intense flowering of the musical madrigal in England, mostly from 1588 to 1627, along with the composers who produced them. The English madrigals were a cappella, predominantly light in style, and generally bega ...

. The English madrigals were a cappella, predominantly light in style, and generally began as either copies or direct translations of Italian models. Most were for three to six voices.

'' Musica reservata'' is either a style or a performance practice in a cappella vocal music of the latter half of the 16th century, mainly in Italy and southern Germany, involving refinement, exclusivity, and intense emotional expression of sung text.

The cultivation of European music in the Americas began in the 16th century soon after the arrival of the Spanish, and the conquest of Mexico. Although fashioned in European style, uniquely Mexican hybrid works based on native Mexican language and European musical practice appeared very early. Musical practices in New Spain continually coincided with European tendencies throughout the subsequent Baroque and Classical music periods. Among these New World composers were Hernando Franco, Antonio de Salazar, and Manuel de Zumaya.

In addition, writers since 1932 have observed what they call a '' seconda prattica'' (an innovative practice involving monodic style and freedom in treatment of dissonance, both justified by the expressive setting of texts) during the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

Mannerism

In the late 16th century, as the Renaissance era closed, an extremely manneristic style developed. In secular music, especially in themadrigal

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance (15th–16th centuries) and early Baroque (1580–1650) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the ...

, there was a trend towards complexity and even extreme chromaticism (as exemplified in madrigals of Luzzaschi, Marenzio, and Gesualdo). The term ''mannerism'' derives from art history.

Transition to the Baroque

Beginning inFlorence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, there was an attempt to revive the dramatic and musical forms of Ancient Greece, through the means of monody

In music, monody refers to a solo vocal style distinguished by having a single melody, melodic line and instrumental accompaniment. Although such music is found in various cultures throughout history, the term is specifically applied to Italy, ...

, a form of declaimed music over a simple accompaniment; a more extreme contrast with the preceding polyphonic style would be hard to find; this was also, at least at the outset, a secular trend. These musicians were known as the Florentine Camerata.

We have already noted some of the musical developments that helped to usher in the Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

, but for further explanation of this transition, see antiphon

An antiphon ( Greek ἀντίφωνον, ἀντί "opposite" and φωνή "voice") is a short chant in Christian ritual, sung as a refrain. The texts of antiphons are usually taken from the Psalms or Scripture, but may also be freely compo ...

, concertato

Concertato is a term in early Baroque music referring to either a ''genre'' or a ''style'' of music in which groups of instruments or voices share a melody, usually in alternation, and almost always over a basso continuo. The term derives from It ...

, monody

In music, monody refers to a solo vocal style distinguished by having a single melody, melodic line and instrumental accompaniment. Although such music is found in various cultures throughout history, the term is specifically applied to Italy, ...

, madrigal

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance (15th–16th centuries) and early Baroque (1580–1650) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the ...

, and opera, as well as the works given under "Sources and further reading."

Instruments

Many instruments originated during the Renaissance; others were variations of, or improvements upon, instruments that had existed previously. Some have survived to the present day; others have disappeared, only to be recreated in order to perform music of the period on authentic instruments. As in the modern day, instruments may be classified as brass, strings, percussion, and woodwind.

Medieval instruments in Europe had most commonly been used singly, often self-accompanied with a drone, or occasionally in parts. From at least as early as the 13th century through the 15th century there was a division of instruments into ''haut'' (loud, shrill, outdoor instruments) and ''bas'' (quieter, more intimate instruments). Only two groups of instruments could play freely in both types of ensembles: the

Many instruments originated during the Renaissance; others were variations of, or improvements upon, instruments that had existed previously. Some have survived to the present day; others have disappeared, only to be recreated in order to perform music of the period on authentic instruments. As in the modern day, instruments may be classified as brass, strings, percussion, and woodwind.

Medieval instruments in Europe had most commonly been used singly, often self-accompanied with a drone, or occasionally in parts. From at least as early as the 13th century through the 15th century there was a division of instruments into ''haut'' (loud, shrill, outdoor instruments) and ''bas'' (quieter, more intimate instruments). Only two groups of instruments could play freely in both types of ensembles: the cornett

The cornett (, ) is a lip-reed wind instrument that dates from the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods, popular from 1500 to 1650. Although smaller and larger sizes were made in both straight and curved forms, surviving cornetts are most ...

and sackbut

A sackbut is an early form of the trombone used during the Renaissance music, Renaissance and Baroque music, Baroque eras. A sackbut has the characteristic telescopic slide of a trombone, used to vary the length of the tube to change Pitch (m ...

, and the tabor and tambourine

The tambourine is a musical instrument in the percussion family consisting of a frame, often of wood or plastic, with pairs of small metal jingles, called "zills". Classically the term tambourine denotes an instrument with a drumhead, thoug ...

.

At the beginning of the 16th century, instruments were considered to be less important than voices. They were used for dances and to accompany vocal music. Instrumental music remained subordinated to vocal music, and much of its repertory was in varying ways derived from or dependent on vocal models.

Organs

Various kinds of organs were commonly used in the Renaissance, from large church organs to small portatives and reed organs called regals.Brass

Brass instruments in the Renaissance were traditionally played by professionals. Some of the more common brass instruments that were played: * Slide trumpet: Similar to the trombone of today except that instead of a section of the body sliding, only a small part of the body near the mouthpiece and the mouthpiece itself is stationary. Also, the body was an S-shape so it was rather unwieldy, but was suitable for the slow dance music which it was most commonly used for. *Cornett

The cornett (, ) is a lip-reed wind instrument that dates from the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods, popular from 1500 to 1650. Although smaller and larger sizes were made in both straight and curved forms, surviving cornetts are most ...

: Made of wood and played like the recorder (by blowing in one end and moving the fingers up and down the outside) but using a cup mouthpiece like a trumpet.

* Trumpet: Early trumpets had no valves, and were limited to the tones present in the overtone series

The harmonic series (also overtone series) is the sequence of harmonics, musical tones, or pure tones whose frequency is an integer multiple of a ''fundamental frequency''.

Pitched musical instruments are often based on an acoustic resonator s ...

. They were also made in different sizes.

* Sackbut

A sackbut is an early form of the trombone used during the Renaissance music, Renaissance and Baroque music, Baroque eras. A sackbut has the characteristic telescopic slide of a trombone, used to vary the length of the tube to change Pitch (m ...

(sometimes sackbutt or sagbutt): A different name for the trombone, which replaced the slide trumpet by the middle of the 15th century.

Strings

As a family, strings were used in many circumstances, both sacred and secular. A few members of this family include: *Viol

The viola da gamba (), or viol, or informally gamba, is a bowed and fretted string instrument that is played (i.e. "on the leg"). It is distinct from the later violin family, violin, or ; and it is any one of the earlier viol family of bow (m ...

: This instrument, developed in the 15th century, commonly has six strings. It was usually played with a bow. It has structural qualities similar to the Spanish plucked vihuela

The vihuela () is a 15th-century fretted plucked Spanish string instrument, shaped like a guitar (figure-of-eight form offering strength and portability) but tuned like a lute. It was used in 15th- and 16th-century Spain as the equivalent of t ...

(called ''viola da mano'' in Italy); its main separating trait is its larger size. This changed the posture of the musician in order to rest it against the floor or between the legs in a manner similar to the cello. Its similarities to the vihuela were sharp waist-cuts, similar frets, a flat back, thin ribs, and identical tuning. When played in this fashion, it was sometimes referred to as "viola da gamba", in order to distinguish it from viols played "on the arm": viole da braccio, which evolved into the violin family.

* Lyre

The lyre () (from Greek λύρα and Latin ''lyra)'' is a string instrument, stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the History of lute-family instruments, lute family of instruments. In organology, a ...

: Its construction is similar to a small harp, although instead of being plucked, it is strummed with a plectrum. Its strings varied in quantity from four, seven, and ten, depending on the era. It was played with the right hand, while the left hand silenced the notes that were not desired. Newer lyres were modified to be played with a bow.

* Irish Harp: Also called the Clàrsach in Scottish Gaelic, or the Cláirseach in Irish, during the Middle Ages it was the most popular instrument of Ireland and Scotland. Due to its significance in Irish history, it is seen even on the Guinness

Guinness () is a stout that originated in the brewery of Arthur Guinness at Guinness Brewery, St. James's Gate, Dublin, Ireland, in the 18th century. It is now owned by the British-based Multinational corporation, multinational alcoholic bever ...

label and is Ireland's national symbol even to this day. To be played it is usually plucked. Its size can vary greatly from a harp that can be played in one's lap to a full-size harp that is placed on the floor

* Hurdy-gurdy

The hurdy-gurdy is a string instrument that produces sound by a hand-turned crank, rosined wheel rubbing against the strings. The wheel functions much like a violin (or nyckelharpa) bow, and single notes played on the instrument sound similar ...

: (Also known as the wheel fiddle), in which the strings are sounded by a wheel which the strings pass over. Its functionality can be compared to that of a mechanical violin, in that its bow (wheel) is turned by a crank. Its distinctive sound is mainly because of its "drone strings" which provide a constant pitch similar in their sound to that of bagpipes.

* Gittern

The gittern was a relatively small gut-strung, round-backed instrument that first appeared in literature and pictorial representation during the 13th century in Western Europe (Iberian Peninsula, Italy, France, England). It is usually depicted p ...

and mandore

Mandore is a suburb and historical town located 9 km north of Jodhpur city in the Jodhpur district of the north-western Indian state of Rajasthan.

History

Mandore is an ancient town, and was the seat of the Gurjar Pratiharas of Mandavy ...

: these instruments were used throughout Europe. Forerunners of modern instruments including the mandolin and guitar.

* Lira da braccio

The lira da braccio (or ''lira de braccio'' or ''lyra de bracio''Michael Praetorius. Syntagma Musicum Theatrum Instrumentorum seu Sciagraphia Wolfenbüttel 1620) was a European Bow (music), bowed string instrument of the Renaissance music, Renaiss ...

* Bandora

* Cittern

* Lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck (music), neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lu ...

* Orpharion

* Vihuela

The vihuela () is a 15th-century fretted plucked Spanish string instrument, shaped like a guitar (figure-of-eight form offering strength and portability) but tuned like a lute. It was used in 15th- and 16th-century Spain as the equivalent of t ...

* Clavichord