Refrigeration is any of various types of

cooling of a space, substance, or system to lower and/or maintain its

temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that quantitatively expresses the attribute of hotness or coldness. Temperature is measurement, measured with a thermometer. It reflects the average kinetic energy of the vibrating and colliding atoms making ...

below the ambient one (while the removed

heat is ejected to a place of higher temperature).

[IIR International Dictionary of Refrigeration, http://dictionary.iifiir.org/search.php ][ASHRAE Terminology, https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/free-resources/ashrae-terminology] Refrigeration is an artificial, or human-made,

cooling method.

Refrigeration refers to the process by which energy, in the form of heat, is removed from a low-temperature medium and transferred to a high-temperature medium.

This work of energy transfer is traditionally driven by

mechanical means (whether

ice

Ice is water that is frozen into a solid state, typically forming at or below temperatures of 0 ° C, 32 ° F, or 273.15 K. It occurs naturally on Earth, on other planets, in Oort cloud objects, and as interstellar ice. As a naturally oc ...

or

electromechanical machines), but it can also be driven by heat,

magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, ...

,

electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

,

laser

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word ''laser'' originated as an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radi ...

, or other means. Refrigeration has many applications, including household

refrigerator

A refrigerator, commonly shortened to fridge, is a commercial and home appliance consisting of a thermal insulation, thermally insulated compartment and a heat pump (mechanical, electronic or chemical) that transfers heat from its inside to ...

s, industrial

freezers,

cryogenics, and

air conditioning

Air conditioning, often abbreviated as A/C (US) or air con (UK), is the process of removing heat from an enclosed space to achieve a more comfortable interior temperature, and in some cases, also controlling the humidity of internal air. Air c ...

.

s may use the heat output of the refrigeration process, and also may be designed to be reversible, but are otherwise similar to air conditioning units.

Refrigeration has had a large impact on industry, lifestyle, agriculture, and settlement patterns.

The idea of preserving food dates back to human

prehistory

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use ...

, but for thousands of years humans were limited regarding the means of doing so. They used

curing via

salting and

drying, and they made use of natural coolness in

cave

Caves or caverns are natural voids under the Earth's Planetary surface, surface. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. Exogene caves are smaller openings that extend a relatively short distance undergrou ...

s,

root cellars, and

winter

Winter is the coldest and darkest season of the year in temperate and polar climates. It occurs after autumn and before spring. The tilt of Earth's axis causes seasons; winter occurs when a hemisphere is oriented away from the Sun. Dif ...

weather, but other means of cooling were unavailable. In the 19th century, they began to make use of the

ice trade to develop

cold chains. In the late 19th through mid-20th centuries, mechanical refrigeration was developed, improved, and greatly expanded in its reach.

Refrigeration has thus rapidly evolved in the past century, from

ice harvesting to

temperature-controlled rail cars,

refrigerator trucks, and ubiquitous

refrigerator

A refrigerator, commonly shortened to fridge, is a commercial and home appliance consisting of a thermal insulation, thermally insulated compartment and a heat pump (mechanical, electronic or chemical) that transfers heat from its inside to ...

s and

freezers in both stores and homes in many countries. The introduction of refrigerated rail cars contributed to the settlement of areas that were not on earlier main transport channels such as rivers, harbors, or valley trails.

These new settlement patterns sparked the building of large cities which are able to thrive in areas that were otherwise thought to be inhospitable, such as

Houston

Houston ( ) is the List of cities in Texas by population, most populous city in the U.S. state of Texas and in the Southern United States. Located in Southeast Texas near Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico, it is the county seat, seat of ...

, Texas, and

Las Vegas

Las Vegas, colloquially referred to as Vegas, is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Nevada and the county seat of Clark County. The Las Vegas Valley metropolitan area is the largest within the greater Mojave Desert, and second-l ...

, Nevada. In most developed countries, cities are heavily dependent upon refrigeration in

supermarket

A supermarket is a self-service Retail#Types of outlets, shop offering a wide variety of food, Drink, beverages and Household goods, household products, organized into sections. Strictly speaking, a supermarket is larger and has a wider selecti ...

s in order to obtain their food for daily consumption. The increase in food sources has led to a larger concentration of agricultural sales coming from a smaller percentage of farms.

Farms today have a much larger output per person in comparison to the late 1800s.

This has resulted in new food sources available to entire populations, which has had a large impact on the nutrition of society.

History

Earliest forms of cooling

The seasonal harvesting of snow and ice is an ancient practice estimated to have begun earlier than 1000 BC.

A Chinese collection of lyrics from this time period known as the ''

Sleaping'', describes religious ceremonies for filling and emptying ice cellars. However, little is known about the construction of these ice cellars or the purpose of the ice. The next ancient society to record the harvesting of ice may have been the Jews in the book of Proverbs, which reads, "As the cold of snow in the time of harvest, so is a faithful messenger to them who sent him." Historians have interpreted this to mean that the Jews used ice to cool beverages rather than to preserve food. Other ancient cultures such as the Greeks and the Romans dug large snow pits insulated with grass, chaff, or branches of trees as cold storage. Like the Jews, the Greeks and Romans did not use ice and snow to preserve food, but primarily as a means to cool beverages. Egyptians cooled water by evaporation in shallow earthen jars on the roofs of their houses at night. The ancient people of India used this same concept to produce ice. The Persians stored ice in a pit called a

Yakhchal and may have been the first group of people to use cold storage to preserve food. In the Australian outback before a reliable electricity supply was available many farmers used a

Coolgardie safe, consisting of a box frame with

hessian (burlap) sides soaked in water. The water would evaporate and thereby cool the interior air, allowing many perishables such as fruit, butter, and cured meats to be kept.

Ice harvesting

Before 1830, few Americans used ice to refrigerate foods due to a lack of ice-storehouses and iceboxes. As these two things became more widely available, individuals used axes and saws to

harvest ice for their storehouses. This method proved to be difficult, dangerous, and certainly did not resemble anything that could be duplicated on a commercial scale.

Despite the difficulties of harvesting ice, Frederic Tudor thought that he could capitalize on this new commodity by harvesting ice in New England and shipping it to the Caribbean islands as well as the southern states. In the beginning, Tudor lost thousands of dollars, but eventually turned a profit as he constructed icehouses in Charleston, Virginia and in the Cuban port town of Havana. These icehouses as well as better insulated ships helped reduce ice wastage from 66% to 8%. This efficiency gain influenced Tudor to expand his ice market to other towns with icehouses such as New Orleans and Savannah. This ice market further expanded as harvesting ice became faster and cheaper after one of Tudor's suppliers, Nathaniel Wyeth, invented a horse-drawn ice cutter in 1825. This invention as well as Tudor's success inspired others to get involved in the

ice trade and the ice industry grew.

Ice became a mass-market commodity by the early 1830s with the price of ice dropping from six cents per pound to a half of a cent per pound. In New York City, ice consumption increased from 12,000 tons in 1843 to 100,000 tons in 1856. Boston's consumption leapt from 6,000 tons to 85,000 tons during that same period. Ice harvesting created a "cooling culture" as majority of people used ice and iceboxes to store their dairy products, fish, meat, and even fruits and vegetables. These early cold storage practices paved the way for many Americans to accept the refrigeration technology that would soon take over the country.

Refrigeration research

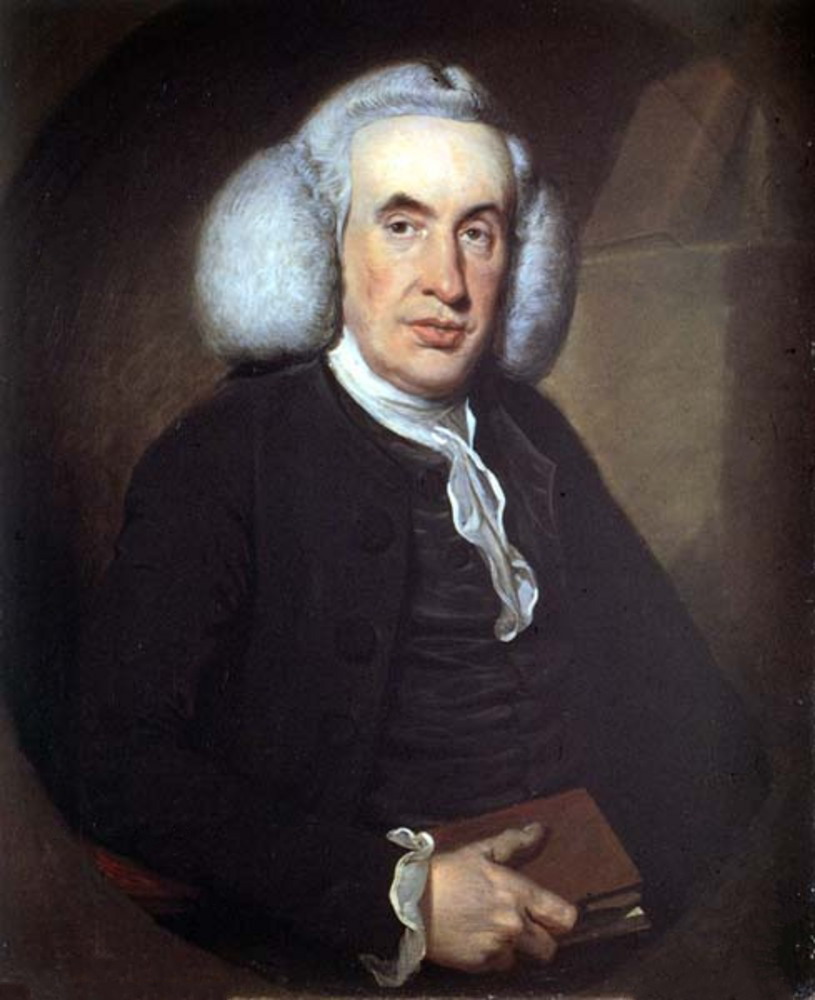

The history of artificial refrigeration began when Scottish professor

William Cullen designed a small refrigerating machine in 1755. Cullen used a pump to create a partial

vacuum over a container of

diethyl ether

Diethyl ether, or simply ether, is an organic compound with the chemical formula , sometimes abbreviated as . It is a colourless, highly Volatility (chemistry), volatile, sweet-smelling ("ethereal odour"), extremely flammable liquid. It belongs ...

, which then

boiled, absorbing

heat from the surrounding air. The experiment even created a small amount of ice, but had no practical application at that time.

In 1758,

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

and

John Hadley, professor of chemistry, collaborated on a project investigating the principle of evaporation as a means to rapidly cool an object at

Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

,

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. They confirmed that the evaporation of highly volatile liquids, such as alcohol and ether, could be used to drive down the temperature of an object past the freezing point of water. They conducted their experiment with the bulb of a mercury thermometer as their object and with a bellows used to quicken the evaporation; they lowered the temperature of the thermometer bulb down to , while the ambient temperature was . They noted that soon after they passed the freezing point of water , a thin film of ice formed on the surface of the thermometer's bulb and that the ice mass was about a thick when they stopped the experiment upon reaching . Franklin wrote, "From this experiment, one may see the possibility of freezing a man to death on a warm summer's day". In 1805, American inventor

Oliver Evans described a closed

vapor-compression refrigeration cycle for the production of ice by ether under vacuum.

In 1820, the English scientist

Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English chemist and physicist who contributed to the study of electrochemistry and electromagnetism. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

liquefied

ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

and other gases by using high pressures and low temperatures, and in 1834, an American expatriate to Great Britain,

Jacob Perkins, built the first working vapor-compression refrigeration system in the world. It was a closed-cycle that could operate continuously, as he described in his patent:

:I am enabled to use volatile fluids for the purpose of producing the cooling or freezing of fluids, and yet at the same time constantly condensing such volatile fluids, and bringing them again into operation without waste.

His prototype system worked although it did not succeed commercially.

In 1842, a similar attempt was made by American physician,

John Gorrie, who built a working prototype, but it was a commercial failure. Like many of the medical experts during this time, Gorrie thought too much exposure to tropical heat led to mental and physical degeneration, as well as the spread of diseases such as malaria. He conceived the idea of using his refrigeration system to cool the air for comfort in homes and hospitals to prevent disease. American engineer

Alexander Twining took out a British patent in 1850 for a vapour compression system that used ether.

The first practical vapour-compression refrigeration system was built by

James Harrison, a British journalist who had emigrated to

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

. His 1856 patent was for a vapour-compression system using ether, alcohol, or ammonia. He built a mechanical ice-making machine in 1851 on the banks of the Barwon River at Rocky Point in

Geelong

Geelong ( ) (Wathawurrung language, Wathawurrung: ''Djilang''/''Djalang'') is a port city in Victoria, Australia, located at the eastern end of Corio Bay (the smaller western portion of Port Phillip Bay) and the left bank of Barwon River (Victo ...

,

Victoria, and his first commercial ice-making machine followed in 1854. Harrison also introduced commercial vapour-compression refrigeration to breweries and meat-packing houses, and by 1861, a dozen of his systems were in operation. He later entered the debate of how to compete against the American advantage of unrefrigerated

beef sales to the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. In 1873 he prepared the sailing ship ''Norfolk'' for an experimental beef shipment to the United Kingdom, which used a cold room system instead of a refrigeration system. The venture was a failure as the ice was consumed faster than expected.

The first

gas absorption refrigeration system using gaseous ammonia dissolved in water (referred to as "aqua ammonia") was developed by

Ferdinand Carré of France in 1859 and patented in 1860.

Carl von Linde, an engineer specializing in

steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, Fuel oil, oil or, rarely, Wood fuel, wood) to heat ...

s and professor of engineering at the

Technological University of Munich in Germany, began researching refrigeration in the 1860s and 1870s in response to demand from brewers for a technology that would allow year-round, large-scale production of

lager; he patented an improved method of liquefying gases in 1876. His new process made possible using gases such as

ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

,

sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless gas with a pungent smell that is responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is r ...

(SO

2) and

methyl chloride (CH

3Cl) as refrigerants and they were widely used for that purpose until the late 1920s.

Thaddeus Lowe, an American balloonist, held several patents on ice-making machines. His "Compression Ice Machine" would revolutionize the cold-storage industry. In 1869, he and other investors purchased an old steamship onto which they loaded one of Lowe's refrigeration units and began shipping fresh fruit from New York to the Gulf Coast area, and fresh meat from Galveston, Texas back to New York, but because of Lowe's lack of knowledge about shipping, the business was a costly failure.

Commercial use

In 1842,

John Gorrie created a system capable of refrigerating water to produce ice. Although it was a commercial failure, it inspired scientists and inventors around the world. France's Ferdinand Carre was one of the inspired and he created an ice producing system that was simpler and smaller than that of Gorrie. During the Civil War, cities such as New Orleans could no longer get ice from New England via the coastal ice trade. Carre's refrigeration system became the solution to New Orleans' ice problems and, by 1865, the city had three of Carre's machines. In 1867, in San Antonio, Texas, a French immigrant named Andrew Muhl built an ice-making machine to help service the expanding beef industry before moving it to Waco in 1871. In 1873, the patent for this machine was contracted by the Columbus Iron Works, a company acquired by the W.C. Bradley Co., which went on to produce the first commercial ice-makers in the US.

By the 1870s, breweries had become the largest users of harvested ice. Though the ice-harvesting industry had grown immensely by the turn of the 20th century, pollution and sewage had begun to creep into natural ice, making it a problem in the metropolitan suburbs. Eventually, breweries began to complain of tainted ice. Public concern for the purity of water, from which ice was formed, began to increase in the early 1900s with the rise of germ theory. Numerous media outlets published articles connecting diseases such as typhoid fever with natural ice consumption. This caused ice harvesting to become illegal in certain areas of the country. All of these scenarios increased the demands for modern refrigeration and manufactured ice. Ice producing machines like that of Carre's and Muhl's were looked to as means of producing ice to meet the needs of grocers, farmers, and food shippers.

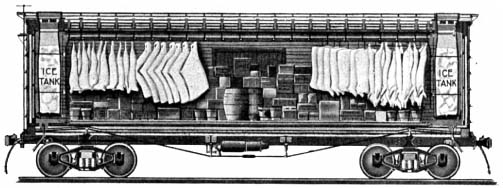

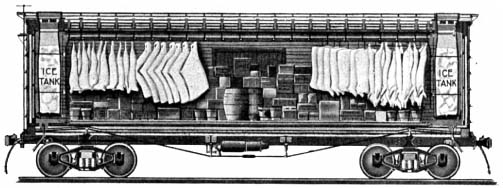

Refrigerated railroad cars were introduced in the US in the 1840s for short-run transport of dairy products, but these used harvested ice to maintain a cool temperature.

The new refrigerating technology first met with widespread industrial use as a means to freeze meat supplies for transport by sea in

reefer ship

A reefer ship is a refrigerated cargo ship typically used to transport perishable cargo, which require air conditioning, temperature-controlled handling, such as fruits, meat, vegetables, dairy products, and similar items.

Description

''Types ...

s from the British

Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

s and other countries to the

British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

. Although not actually the first to achieve successful transportation of frozen goods overseas (the ''Strathleven'' had arrived at the London docks on 2 February 1880 with a cargo of frozen beef, mutton and butter from Sydney and Melbourne ), the breakthrough is often attributed to

William Soltau Davidson, an entrepreneur who had emigrated to

New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

. Davidson thought that Britain's rising population and meat demand could mitigate the slump in world

wool

Wool is the textile fiber obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have some properties similar to animal w ...

markets that was heavily affecting New Zealand. After extensive research, he commissioned the

''Dunedin'' to be refitted with a compression refrigeration unit for meat shipment in 1881. On February 15, 1882, the ''Dunedin'' sailed for London with what was to be the first commercially successful refrigerated shipping voyage, and the foundation of the refrigerated

meat industry.

''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' commented "Today we have to record such a triumph over physical difficulties, as would have been incredible, even unimaginable, a very few days ago...". The ''

Marlborough''—sister ship to the ''Dunedin'' – was immediately converted and joined the trade the following year, along with the rival

New Zealand Shipping Company vessel ''Mataurua'', while the German Steamer ''Marsala'' began carrying frozen New Zealand lamb in December 1882. Within five years, 172 shipments of frozen meat were sent from New Zealand to the United Kingdom, of which only 9 had significant amounts of meat condemned. Refrigerated shipping also led to a broader meat and dairy boom in

Australasia

Australasia is a subregion of Oceania, comprising Australia, New Zealand (overlapping with Polynesia), and sometimes including New Guinea and surrounding islands (overlapping with Melanesia). The term is used in a number of different context ...

and South America.

J & E Hall of

Dartford

Dartford is the principal town in the Borough of Dartford, Kent, England. It is located south-east of Central London and

is situated adjacent to the London Borough of Bexley to its west. To its north, across the Thames Estuary, is Thurrock in ...

, England outfitted the ''SS Selembria'' with a vapor compression system to bring 30,000 carcasses of

mutton from the

Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; ), commonly referred to as The Falklands, is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and from Cape Dub ...

in 1886. In the years ahead, the industry rapidly expanded to Australia, Argentina and the United States.

By the 1890s, refrigeration played a vital role in the distribution of food. The meat-packing industry relied heavily on natural ice in the 1880s and continued to rely on manufactured ice as those technologies became available. By 1900, the meat-packing houses of Chicago had adopted ammonia-cycle commercial refrigeration. By 1914, almost every location used artificial refrigeration. The

major meat packers, Armour, Swift, and Wilson, had purchased the most expensive units which they installed on train cars and in branch houses and storage facilities in the more remote distribution areas.

By the middle of the 20th century, refrigeration units were designed for installation on trucks or lorries. Refrigerated vehicles are used to transport perishable goods, such as frozen foods, fruit and vegetables, and temperature-sensitive chemicals. Most modern refrigerators keep the temperature between –40 and –20 °C, and have a maximum payload of around 24,000 kg gross weight (in Europe).

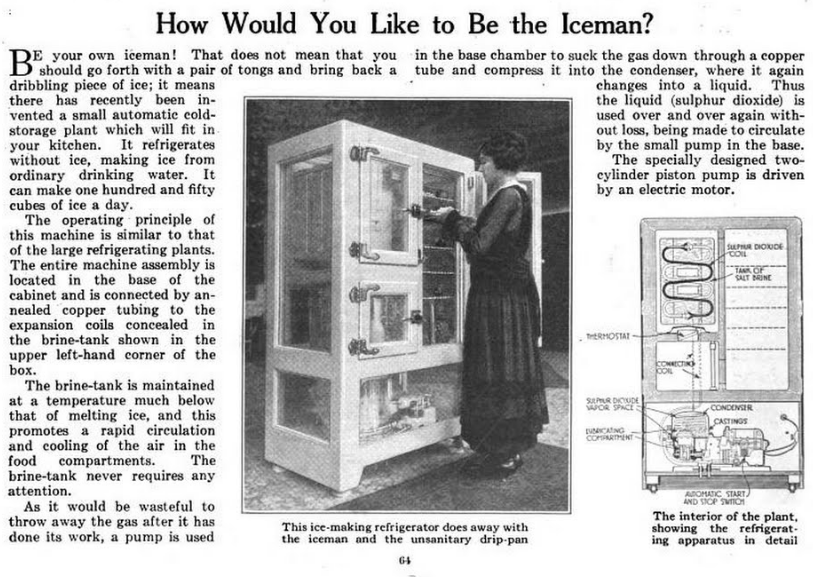

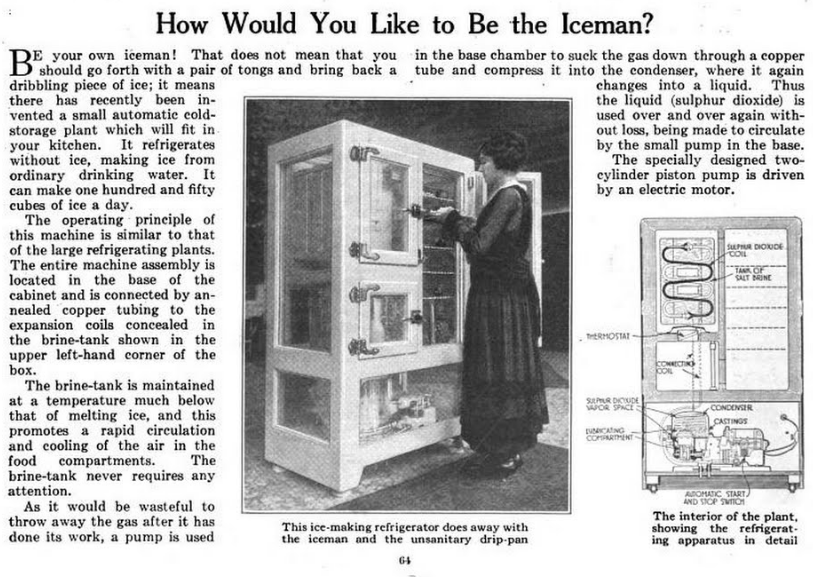

Although commercial refrigeration quickly progressed, it had limitations that prevented it from moving into the household. First, most refrigerators were far too large. Some of the commercial units being used in 1910 weighed between five and two hundred tons. Second, commercial refrigerators were expensive to produce, purchase, and maintain. Lastly, these refrigerators were unsafe. It was not uncommon for commercial refrigerators to catch fire, explode, or leak toxic gases. Refrigeration did not become a household technology until these three challenges were overcome.

Home and consumer use

During the early 1800s, consumers preserved their food by storing food and ice purchased from ice harvesters in iceboxes. In 1803, Thomas Moore patented a metal-lined butter-storage tub which became the prototype for most iceboxes. These iceboxes were used until nearly 1910 and the technology did not progress. In fact, consumers that used the icebox in 1910 faced the same challenge of a moldy and stinky icebox that consumers had in the early 1800s.

General Electric (GE) was one of the first companies to overcome these challenges. In 1911, GE released a household refrigeration unit that was powered by gas. The use of gas eliminated the need for an electric compressor motor and decreased the size of the refrigerator. However, electric companies that were customers of GE did not benefit from a gas-powered unit. Thus, GE invested in developing an electric model. In 1927, GE released the Monitor Top, the first refrigerator to run on electricity.

In 1930, Frigidaire, one of GE's main competitors, synthesized

Freon. With the invention of synthetic refrigerants based mostly on a

chlorofluorocarbon

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) are fully or partly Halogenation, halogenated hydrocarbons that contain carbon (C), hydrogen (H), chlorine (Cl), and fluorine (F). They are produced as volatility (chemistry), volat ...

(CFC) chemical, safer refrigerators were possible for home and consumer use. Freon led to the development of smaller, lighter, and cheaper refrigerators. The average price of a refrigerator dropped from $275 to $154 with the synthesis of Freon. This lower price allowed ownership of refrigerators in American households to exceed 50% by 1940. Freon is a trademark of the DuPont Corporation and refers to these CFCs, and later hydro chlorofluorocarbon (HCFC) and hydro fluorocarbon (HFC), refrigerants developed in the late 1920s. These refrigerants were considered — at the time — to be less harmful than the commonly-used refrigerants of the time, including methyl formate, ammonia, methyl chloride, and sulfur dioxide. The intent was to provide refrigeration equipment for home use without danger. These CFC refrigerants answered that need. In the 1970s, though, the compounds were found to be reacting with atmospheric ozone, an important protection against solar ultraviolet radiation, and their use as a refrigerant worldwide was curtailed in the

Montreal Protocol of 1987.

Impact on settlement patterns in the United States of America

In the last century, refrigeration allowed new settlement patterns to emerge. This new technology has allowed for new areas to be settled that are not on a natural channel of transport such as a river, valley trail or harbor that may have otherwise not been settled. Refrigeration has given opportunities to early settlers to expand westward and into rural areas that were unpopulated. These new settlers with rich and untapped soil saw opportunity to profit by sending raw goods to the eastern cities and states. In the 20th century, refrigeration has made "Galactic Cities" such as Dallas, Phoenix, and Los Angeles possible.

Refrigerated rail cars

The refrigerated rail car (

refrigerated van or

refrigerator car), along with the dense railroad network, became an exceedingly important link between the marketplace and the farm allowing for a national opportunity rather than a just a regional one. Before the invention of the refrigerated rail car, it was impossible to ship perishable food products long distances. The beef packing industry made the first demand push for refrigeration cars. The railroad companies were slow to adopt this new invention because of their heavy investments in cattle cars, stockyards, and feedlots. Refrigeration cars were also complex and costly compared to other rail cars, which also slowed the adoption of the refrigerated rail car. After the slow adoption of the refrigerated car, the beef packing industry dominated the refrigerated rail car business with their ability to control ice plants and the setting of icing fees. The United States Department of Agriculture estimated that, in 1916, over sixty-nine percent of the cattle killed in the country was done in plants involved in interstate trade. The same companies that were also involved in the meat trade later implemented refrigerated transport to include vegetables and fruit. The meat packing companies had much of the expensive machinery, such as refrigerated cars, and cold storage facilities that allowed for them to effectively distribute all types of perishable goods. During World War I, a national refrigerator car pool was established by the United States Administration to deal with problem of idle cars and was later continued after the war. The idle car problem was the problem of refrigeration cars sitting pointlessly in between seasonal harvests. This meant that very expensive cars sat in rail yards for a good portion of the year while making no revenue for the car's owner. The car pool was a system where cars were distributed to areas as crops matured ensuring maximum use of the cars. Refrigerated rail cars moved eastward from vineyards, orchards, fields, and gardens in western states to satisfy Americas consuming market in the east. The refrigerated car made it possible to transport perishable crops hundreds and even thousands of kilometres or miles. The most noticeable effect the car gave was a regional specialization of vegetables and fruits. The refrigeration rail car was widely used for the transportation of perishable goods up until the 1950s. By the 1960s, the nation's interstate highway system was adequately complete allowing for trucks to carry the majority of the perishable food loads and to push out the old system of the refrigerated rail cars.

Expansion west and into rural areas

The widespread use of refrigeration allowed for a vast amount of new agricultural opportunities to open up in the United States. New markets emerged throughout the United States in areas that were previously uninhabited and far-removed from heavily populated areas. New agricultural opportunity presented itself in areas that were considered rural, such as states in the south and in the west. Shipments on a large scale from the south and California were both made around the same time, although natural ice was used from the Sierras in California rather than manufactured ice in the south. Refrigeration allowed for many areas to specialize in the growing of specific fruits. California specialized in several fruits, grapes, peaches, pears, plums, and apples, while Georgia became famous for specifically its peaches. In California, the acceptance of the refrigerated rail cars led to an increase of car loads from 4,500 carloads in 1895 to between 8,000 and 10,000 carloads in 1905. The Gulf States, Arkansas, Missouri and Tennessee entered into strawberry production on a large-scale while Mississippi became the center of the

tomato industry. New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and Nevada grew cantaloupes. Without refrigeration, this would have not been possible. By 1917, well-established fruit and vegetable areas that were close to eastern markets felt the pressure of competition from these distant specialized centers. Refrigeration was not limited to meat, fruit and vegetables but it also encompassed dairy product and dairy farms. In the early twentieth century, large cities got their dairy supply from farms as far as . Dairy products were not as easily transported over great distances like fruits and vegetables due to greater perishability. Refrigeration made production possible in the west far from eastern markets, so much in fact that dairy farmers could pay transportation cost and still undersell their eastern competitors. Refrigeration and the refrigerated rail gave opportunity to areas with rich soil far from natural channel of transport such as a river, valley trail or harbors.

Rise of the galactic city

"Edge city" was a term coined by

Joel Garreau, whereas the term "galactic city" was coined by

Lewis Mumford. These terms refer to a concentration of business, shopping, and entertainment outside a traditional downtown or central business district in what had previously been a residential or rural area. There were several factors contributing to the growth of these cities such as Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Houston, and Phoenix. The factors that contributed to these large cities include reliable automobiles, highway systems, refrigeration, and agricultural production increases. Large cities such as the ones mentioned above have not been uncommon in history, but what separates these cities from the rest are that these cities are not along some natural channel of transport, or at some crossroad of two or more channels such as a trail, harbor, mountain, river, or valley. These large cities have been developed in areas that only a few hundred years ago would have been uninhabitable. Without a cost efficient way of cooling air and transporting water and food from great distances, these large cities would have never developed. The rapid growth of these cities was influenced by refrigeration and an agricultural productivity increase, allowing more distant farms to effectively feed the population.

Impact on agriculture and food production

Agriculture's role in developed countries has drastically changed in the last century due to many factors, including refrigeration. Statistics from the 2007 census gives information on the large concentration of agricultural sales coming from a small portion of the existing farms in the United States today. This is a partial result of the market created for the frozen meat trade by the first successful shipment of frozen sheep carcasses coming from New Zealand in the 1880s. As the market continued to grow, regulations on food processing and quality began to be enforced. Eventually, electricity was introduced into rural homes in the United States, which allowed refrigeration technology to continue to expand on the farm, increasing output per person. Today, refrigeration's use on the farm reduces humidity levels, avoids spoiling due to bacterial growth, and assists in preservation.

Demographics

The introduction of refrigeration and evolution of additional technologies drastically changed agriculture in the United States. During the beginning of the 20th century, farming was a common occupation and lifestyle for United States citizens, as most farmers actually lived on their farm. In 1935, there were 6.8 million farms in the United States and a population of 127 million. Yet, while the United States population has continued to climb, citizens pursuing agriculture continue to decline. Based on the 2007 US Census, less than one percent of a population of 310 million people claim farming as an occupation today. However, the increasing population has led to an increasing demand for agricultural products, which is met through a greater variety of crops, fertilizers, pesticides, and improved technology. Improved technology has decreased the risk and time involved for agricultural management and allows larger farms to increase their output per person to meet society's demand.

Meat packing and trade

Prior to 1882, the

South Island

The South Island ( , 'the waters of Pounamu, Greenstone') is the largest of the three major islands of New Zealand by surface area, the others being the smaller but more populous North Island and Stewart Island. It is bordered to the north by ...

of New Zealand had been experimenting with sowing grass and crossbreeding sheep, which immediately gave their farmers economic potential in the exportation of meat. In 1882, the first successful shipment of sheep carcasses was sent from

Port Chalmers

Port Chalmers () is a town serving as the main port of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand. Port Chalmers lies ten kilometres inside Otago Harbour, some 15 kilometres northeast of Dunedin's city centre.

History

Early Māori settlement

The or ...

in

Dunedin

Dunedin ( ; ) is the second-most populous city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from ("fort of Edin"), the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of S ...

, New Zealand, to

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. By the 1890s, the frozen meat trade became increasingly more profitable in New Zealand, especially in

Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the county of Kent, England; it was a county borough until 1974. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour. The city has a mild oceanic climat ...

, where 50% of exported sheep carcasses came from in 1900. It was not long before Canterbury meat was known for the highest quality, creating a demand for New Zealand meat around the world. In order to meet this new demand, the farmers improved their feed so sheep could be ready for the slaughter in only seven months. This new method of shipping led to an economic boom in New Zealand by the mid 1890s.

In the United States, the Meat Inspection Act of 1891 was put in place in the United States because local butchers felt the refrigerated railcar system was unwholesome. When meat packing began to take off, consumers became nervous about the quality of the meat for consumption.

Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American author, muckraker journalist, and political activist, and the 1934 California gubernatorial election, 1934 Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

's 1906 novel ''

The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a novel by American author and muckraking-journalist Upton Sinclair, known for his efforts to expose corruption in government and business in the early 20th century.

In 1904, Sinclair spent seven weeks gathering information ...

'' brought negative attention to the meat packing industry, by drawing to light unsanitary working conditions and processing of diseased animals. The book caught the attention of President

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, and

the 1906 Meat Inspection Act was put into place as an amendment to the Meat Inspection Act of 1891. This new act focused on the quality of the meat and environment it is processed in.

Electricity in rural areas

In the early 1930s, 90 percent of the urban population of the United States

had electric power, in comparison to only 10 percent of rural homes. At the time, power companies did not feel that extending power to rural areas (

rural electrification

Rural electrification is the process of bringing electrical power to rural and remote areas. Rural communities are suffering from colossal market failures as the national grids fall short of their demand for electricity. As of 2019, 770 million ...

) would produce enough profit to make it worth their while. However, in the midst of the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

realized that rural areas would continue to lag behind urban areas in both poverty and production if they were not electrically wired. On May 11, 1935, the president signed an executive order called the

Rural Electrification Administration, also known as REA. The agency provided loans to fund electric infrastructure in the rural areas. In just a few years, 300,000 people in rural areas of the United States had received power in their homes.

While electricity dramatically improved working conditions on farms, it also had a large impact on the safety of food production. Refrigeration systems were introduced to the farming and

food distribution processes, which helped in

food preservation

Food preservation includes processes that make food more resistant to microorganism growth and slow the redox, oxidation of fats. This slows down the decomposition and rancidification process. Food preservation may also include processes that in ...

and

kept food supplies safe. Refrigeration also allowed for shipment of perishable commodities throughout the United States. As a result, United States farmers quickly became the most productive in the world, and entire new

food systems

The term food system describes the interconnected systems and processes that influence nutrition, food, health, community development, and agriculture. A food system includes all processes and infrastructure involved in feeding a population: grow ...

arose.

Farm use

In order to reduce humidity levels and spoiling due to bacterial growth, refrigeration is used for meat, produce, and dairy processing in farming today. Refrigeration systems are used the heaviest in the warmer months for farming produce, which must be cooled as soon as possible in order to meet quality standards and increase the shelf life. Meanwhile, dairy farms refrigerate milk year round to avoid spoiling.

Effects on lifestyle and diet

In the late 19th Century and into the very early 20th Century, except for staple foods (sugar, rice, and beans) that needed no refrigeration, the available foods were affected heavily by the seasons and what could be grown locally. Refrigeration has removed these limitations. Refrigeration played a large part in the feasibility and then popularity of the modern supermarket. Fruits and vegetables out of season, or grown in distant locations, are now available at relatively low prices. Refrigerators have led to a huge increase in meat and dairy products as a portion of overall supermarket sales. As well as changing the goods purchased at the market, the ability to store these foods for extended periods of time has led to an increase in leisure time. Prior to the advent of the household refrigerator, people would have to shop on a daily basis for the supplies needed for their meals.

Impact on nutrition

The introduction of refrigeration allowed for the hygienic handling and storage of perishables, and as such, promoted output growth, consumption, and the availability of nutrition. The change in our method of food preservation moved us away from salts to a more manageable sodium level. The ability to move and store perishables such as meat and dairy led to a 1.7% increase in dairy consumption and overall protein intake by 1.25% annually in the US after the 1890s.

People were not only consuming these perishables because it became easier for they themselves to store them, but because the innovations in refrigerated transportation and storage led to less spoilage and waste, thereby driving the prices of these products down. Refrigeration accounts for at least 5.1% of the increase in adult stature (in the US) through improved nutrition, and when the indirect effects associated with improvements in the quality of nutrients and the reduction in illness is additionally factored in, the overall impact becomes considerably larger.

Recent studies have also shown a negative relationship between the number of refrigerators in a household and the rate of gastric cancer mortality.

Current applications of refrigeration

Probably the most widely used current applications of refrigeration are for

air conditioning

Air conditioning, often abbreviated as A/C (US) or air con (UK), is the process of removing heat from an enclosed space to achieve a more comfortable interior temperature, and in some cases, also controlling the humidity of internal air. Air c ...

of private homes and public buildings, and refrigerating foodstuffs in homes, restaurants and large storage warehouses. The use of

refrigerator

A refrigerator, commonly shortened to fridge, is a commercial and home appliance consisting of a thermal insulation, thermally insulated compartment and a heat pump (mechanical, electronic or chemical) that transfers heat from its inside to ...

s and walk-in coolers and freezers in kitchens, factories and warehouses for storing and processing fruits and vegetables has allowed adding fresh salads to the modern diet year round, and storing fish and meats safely for long periods.

The optimum temperature range for perishable food storage is .

[Keep your fridge-freezer clean and ice-free](_blank)

''BBC''. 30 April 2008

In commerce and manufacturing, there are many uses for refrigeration. Refrigeration is used to liquefy gases –

oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

,

nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

,

propane

Propane () is a three-carbon chain alkane with the molecular formula . It is a gas at standard temperature and pressure, but becomes liquid when compressed for transportation and storage. A by-product of natural gas processing and petroleum ref ...

, and

methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The abundance of methane on Earth makes ...

, for example. In compressed air purification, it is used to

condense water vapor from compressed air to reduce its moisture content. In

oil refineries,

chemical plants, and

petrochemical plants, refrigeration is used to maintain certain processes at their needed low temperatures (for example, in

alkylation Alkylation is a chemical reaction that entails transfer of an alkyl group. The alkyl group may be transferred as an alkyl carbocation, a free radical, a carbanion, or a carbene (or their equivalents). Alkylating agents are reagents for effecting al ...

of

butenes and

butane to produce a high-

octane gasoline component). Metal workers use refrigeration to temper steel and cutlery. When transporting temperature-sensitive foodstuffs and other materials by trucks, trains, airplanes and seagoing vessels, refrigeration is a necessity.

Dairy products are constantly in need of refrigeration,

and it was only discovered in the past few decades that eggs needed to be refrigerated during shipment rather than waiting to be refrigerated after arrival at the grocery store. Meats, poultry and fish all must be kept in climate-controlled environments before being sold.

Refrigeration also helps keep fruits and vegetables edible longer.

One of the most influential uses of refrigeration was in the development of the

sushi

is a traditional Japanese dish made with , typically seasoned with sugar and salt, and combined with a variety of , such as seafood, vegetables, or meat: raw seafood is the most common, although some may be cooked. While sushi comes in n ...

/

sashimi

is a Japanese cuisine, Japanese delicacy consisting of fresh raw fish or Raw meat, meat sliced into thin pieces and often eaten with soy sauce.

Origin

The word ''sashimi'' means 'pierced body', i.e., "wikt:刺身, 刺身" = ''sashimi'', whe ...

industry in Japan. Before the discovery of refrigeration, many sushi connoisseurs were at risk of contracting diseases. The dangers of unrefrigerated sashimi were not brought to light for decades due to the lack of research and healthcare distribution across rural Japan. Around mid-century, the

Zojirushi corporation, based in Kyoto, made breakthroughs in refrigerator designs, making refrigerators cheaper and more accessible for restaurant proprietors and the general public.

Methods of refrigeration

Methods of refrigeration can be classified as ''non-cyclic'', ''cyclic'', ''thermoelectric'' and ''magnetic''.

Non-cyclic refrigeration

This refrigeration method cools a contained area by melting ice, or by sublimating

dry ice

Dry ice is the solid form of carbon dioxide. It is commonly used for temporary refrigeration as CO2 does not have a liquid state at normal atmospheric pressure and Sublimation (phase transition), sublimes directly from the solid state to the gas ...

. Perhaps the simplest example of this is a portable cooler, where items are put in it, then ice is poured over the top. Regular ice can maintain temperatures near, but not below the freezing point, unless salt is used to cool the ice down further (as in a

traditional ice-cream maker). Dry ice can reliably bring the temperature well below water freezing point.

Cyclic refrigeration

This consists of a refrigeration cycle, where heat is removed from a low-temperature space or source and rejected to a high-temperature sink with the help of external work, and its inverse, the

thermodynamic power cycle. In the power cycle, heat is supplied from a high-temperature source to the engine, part of the heat being used to produce work and the rest being rejected to a low-temperature sink. This satisfies the

second law of thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law based on Universal (metaphysics), universal empirical observation concerning heat and Energy transformation, energy interconversions. A simple statement of the law is that heat always flows spont ...

.

A ''refrigeration cycle'' describes the changes that take place in the refrigerant as it alternately absorbs and rejects heat as it circulates through a

refrigerator

A refrigerator, commonly shortened to fridge, is a commercial and home appliance consisting of a thermal insulation, thermally insulated compartment and a heat pump (mechanical, electronic or chemical) that transfers heat from its inside to ...

. It is also applied to heating, ventilation, and air conditioning

HVACR work, when describing the "process" of refrigerant flow through an HVACR unit, whether it is a packaged or split system.

Heat naturally flows from hot to cold.

Work is applied to cool a living space or storage volume by pumping heat from a lower temperature heat source into a higher temperature heat sink.

Insulation is used to reduce the work and

energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

needed to achieve and maintain a lower temperature in the cooled space. The operating principle of the refrigeration cycle was described mathematically by

Sadi Carnot in 1824 as a

heat engine.

The most common types of refrigeration systems use the reverse-Rankine

vapor-compression refrigeration cycle, although

absorption heat pumps are used in a minority of applications.

Cyclic refrigeration can be classified as:

#Vapor cycle, and

#Gas cycle

Vapor cycle refrigeration can further be classified as:

#

Vapor-compression refrigeration

#Sorption Refrigeration

##

Vapor-absorption refrigeration

##

Adsorption refrigeration

Vapor-compression cycle

The vapor-compression cycle is used in most household refrigerators as well as in many large commercial and

industrial refrigeration systems. Figure 1 provides a schematic diagram of the components of a typical vapor-compression refrigeration system.

The

thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, Work (thermodynamics), work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed b ...

of the cycle can be analyzed on a diagram as shown in Figure 2. In this cycle, a circulating refrigerant such as a low boiling hydrocarbon or

hydrofluorocarbons enters the

compressor as a vapour. From point 1 to point 2, the vapor is compressed at constant

entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, most commonly associated with states of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynamics, where it was first recognized, to the micros ...

and exits the compressor as a vapor at a higher temperature, but still below the

vapor pressure at that temperature. From point 2 to point 3 and on to point 4, the vapor travels through the

condenser which cools the vapour until it starts condensing, and then condenses the vapor into a liquid by removing additional heat at constant pressure and temperature. Between points 4 and 5, the liquid refrigerant goes through the

expansion valve (also called a throttle valve) where its pressure abruptly decreases, causing

flash evaporation and auto-refrigeration of, typically, less than half of the liquid.

That results in a mixture of liquid and vapour at a lower temperature and pressure as shown at point 5. The cold liquid-vapor mixture then travels through the evaporator coil or tubes and is completely vaporized by cooling the warm air (from the space being refrigerated) being blown by a fan across the evaporator coil or tubes. The resulting refrigerant vapour returns to the compressor inlet at point 1 to complete the thermodynamic cycle.

The above discussion is based on the ideal vapour-compression refrigeration cycle, and does not take into account real-world effects like frictional pressure drop in the system, slight

thermodynamic irreversibility during the compression of the refrigerant vapor, or

non-ideal gas behavior, if any. Vapor compression refrigerators can be arranged in two stages in

cascade refrigeration systems, with the second stage cooling the condenser of the first stage. This can be used for achieving very low temperatures.

More information about the design and performance of vapor-compression refrigeration systems is available in the classic ''

Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook''.

Sorption cycle

=Absorption cycle

=

In the early years of the twentieth century, the vapor absorption cycle using water-ammonia systems or

LiBr-water was popular and widely used. After the development of the vapor compression cycle, the vapor absorption cycle lost much of its importance because of its low

coefficient of performance (about one fifth of that of the vapor compression cycle). Today, the vapor absorption cycle is used mainly where fuel for heating is available but electricity is not, such as in

recreational vehicles that carry

LP gas. It is also used in industrial environments where plentiful waste heat overcomes its inefficiency.

The absorption cycle is similar to the compression cycle, except for the method of raising the pressure of the refrigerant vapor. In the absorption system, the compressor is replaced by an absorber which dissolves the refrigerant in a suitable liquid, a liquid pump which raises the pressure and a generator which, on heat addition, drives off the refrigerant vapor from the high-pressure liquid. Some work is needed by the liquid pump but, for a given quantity of refrigerant, it is much smaller than needed by the compressor in the vapor compression cycle. In an absorption refrigerator, a suitable combination of refrigerant and absorbent is used. The most common combinations are ammonia (refrigerant) with water (absorbent), and water (refrigerant) with lithium bromide (absorbent).

=Adsorption cycle

=

The main difference from absorption cycle is that in adsorption cycle, the refrigerant (adsorbate) can be ammonia, water,

methanol, etc., while the adsorbent is a solid, such as

silica gel,

activated carbon, or

zeolite, while in the absorption cycle the absorbent is liquid.

The reason adsorption refrigeration technology has been extensively researched in recent 30 years lies in that the operation of an adsorption refrigeration system is often noiseless, non-corrosive and environmentally friendly.

Gas cycle

When the

working fluid is a gas that is compressed and expanded but does not change phase, the refrigeration cycle is called a ''gas cycle''.

Air is most often this working fluid. As there is no condensation and evaporation intended in a gas cycle, components corresponding to the condenser and evaporator in a vapor compression cycle are the hot and cold gas-to-gas

heat exchangers in gas cycles.

The gas cycle is less efficient than the vapor compression cycle because the gas cycle works on the reverse

Brayton cycle instead of the reverse

Rankine cycle. As such, the working fluid does not receive and reject heat at constant temperature. In the gas cycle, the refrigeration effect is equal to the product of the specific heat of the gas and the rise in temperature of the gas in the low temperature side. Therefore, for the same cooling load, a gas refrigeration cycle needs a large mass flow rate and is bulky.

Because of their lower efficiency and larger bulk, ''air cycle'' coolers are not often used nowadays in terrestrial cooling devices. However, the

air cycle machine is very common on

gas turbine

A gas turbine or gas turbine engine is a type of Internal combustion engine#Continuous combustion, continuous flow internal combustion engine. The main parts common to all gas turbine engines form the power-producing part (known as the gas gene ...

-powered jet

aircraft

An aircraft ( aircraft) is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or, i ...

as cooling and ventilation units, because compressed air is readily available from the engines' compressor sections. Such units also serve the purpose of pressurizing the aircraft.

Thermoelectric refrigeration

Thermoelectric cooling uses the

Peltier effect to create a heat

flux between the junction of two types of material.

This effect is commonly used in camping and portable coolers and for cooling electronic components and small instruments. Peltier coolers are often used where a traditional vapor-compression cycle refrigerator would be impractical or take up too much space, and in cooled image sensors as an easy, compact and lightweight, if inefficient, way to achieve very low temperatures, using two or more stage peltier coolers arranged in a

cascade refrigeration configuration, meaning that two or more Peltier elements are stacked on top of each other, with each stage being larger than the one before it, in order to extract more heat and waste heat generated by the previous stages. Peltier cooling has a low COP (efficiency) when compared with that of the vapor-compression cycle, so it emits more waste heat (heat generated by the Peltier element or cooling mechanism) and consumes more power for a given cooling capacity.

Magnetic refrigeration

Magnetic refrigeration, or

adiabatic demagnetization, is a cooling technology based on the magnetocaloric effect, an

intrinsic property of magnetic solids. The refrigerant is often a

paramagnetic salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as r ...

, such as

cerium magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 ...

nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . salt (chemistry), Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are solubility, soluble in wa ...

. The active

magnetic dipoles in this case are those of the

electron shells of the paramagnetic atoms.

A strong magnetic field is applied to the refrigerant, forcing its various magnetic dipoles to align and putting these degrees of freedom of the refrigerant into a state of lowered

entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, most commonly associated with states of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodynamics, where it was first recognized, to the micros ...

. A heat sink then absorbs the heat released by the refrigerant due to its loss of entropy. Thermal contact with the heat sink is then broken so that the system is insulated, and the magnetic field is switched off. This increases the heat capacity of the refrigerant, thus decreasing its temperature below the temperature of the heat sink.

Because few materials exhibit the needed properties at room temperature, applications have so far been limited to

cryogenics and research.

Other methods

Other methods of refrigeration include the

air cycle machine used in aircraft; the

vortex tube used for spot cooling, when compressed air is available; and

thermoacoustic refrigeration using sound waves in a pressurized gas to drive heat transfer and heat exchange;

steam jet cooling popular in the early 1930s for air conditioning large buildings; thermoelastic cooling using a smart metal alloy stretching and relaxing. Many

Stirling cycle

The Stirling cycle is a thermodynamic cycle that describes the general class of Stirling devices. This includes the original Stirling engine that was invented, developed and patented in 1816 by Robert Stirling with help from his brother, an en ...

heat engines can be run backwards to act as a refrigerator, and therefore these engines have a niche use in

cryogenics. In addition, there are other types of

cryocoolers such as Gifford-McMahon coolers, Joule-Thomson coolers,

pulse-tube refrigerators and, for temperatures between 2 mK and 500 mK,

dilution refrigerators.

Elastocaloric refrigeration

Another potential solid-state refrigeration technique and a relatively new area of study comes from a special property of

super elastic materials. These materials undergo a temperature change when experiencing an applied mechanical

stress (called the elastocaloric effect). Since super elastic materials deform reversibly at high

strains, the material experiences a flattened

elastic

Elastic is a word often used to describe or identify certain types of elastomer, Elastic (notion), elastic used in garments or stretch fabric, stretchable fabrics.

Elastic may also refer to:

Alternative name

* Rubber band, ring-shaped band of rub ...

region in its

stress-strain curve caused by a resulting phase transformation from an

austenitic to a

martensitic crystal phase.

When a super elastic material experiences a stress in the austenitic phase, it undergoes an

exothermic phase transformation to the martensitic phase, which causes the material to heat up. Removing the stress reverses the process, restores the material to its austenitic phase, and

absorbs heat from the surroundings cooling down the material.

The most appealing part of this research is how potentially energy efficient and environmentally friendly this cooling technology is. The different materials used, commonly

shape-memory alloys, provide a non-toxic source of emission free refrigeration. The most commonly studied materials studied are shape-memory alloys, like

nitinol

Nickel titanium, also known as nitinol, is a metal alloy of nickel and titanium, where the two elements are present in roughly equal atomic percentages. Different alloys are named according to the weight percentage of nickel; e.g., nitinol 55 and ...

and Cu-Zn-Al. Nitinol is of the more promising alloys with output heat at about 66 J/cm

3 and a temperature change of about 16–20 K. Due to the difficulty in manufacturing some of the shape memory alloys, alternative materials like

natural rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds.

Types of polyisoprene ...

have been studied. Even though rubber may not give off as much heat per volume (12 J/cm

3 ) as the shape memory alloys, it still generates a comparable temperature change of about 12 K and operates at a suitable temperature range, low stresses, and low cost.

The main challenge however comes from potential energy losses in the form of

hysteresis

Hysteresis is the dependence of the state of a system on its history. For example, a magnet may have more than one possible magnetic moment in a given magnetic field, depending on how the field changed in the past. Plots of a single component of ...

, often associated with this process. Since most of these losses comes from incompatibilities between the two phases, proper alloy tuning is necessary to reduce losses and increase reversibility and

efficiency

Efficiency is the often measurable ability to avoid making mistakes or wasting materials, energy, efforts, money, and time while performing a task. In a more general sense, it is the ability to do things well, successfully, and without waste.

...

. Balancing the transformation strain of the material with the energy losses enables a large elastocaloric effect to occur and potentially a new alternative for refrigeration.

Fridge Gate

The Fridge Gate method is a theoretical application of using a single logic gate to drive a refrigerator in the most energy efficient way possible without violating the laws of thermodynamics. It operates on the fact that there are two energy states in which a particle can exist: the ground state and the excited state. The excited state carries a little more energy than the ground state, small enough so that the transition occurs with high probability. There are three components or particle types associated with the fridge gate. The first is on the interior of the refrigerator, the second on the outside and the third is connected to a power supply which heats up every so often that it can reach the E state and replenish the source. In the cooling step on the inside of the refrigerator, the g state particle absorbs energy from ambient particles, cooling them, and itself jumping to the e state. In the second step, on the outside of the refrigerator where the particles are also at an e state, the particle falls to the g state, releasing energy and heating the outside particles. In the third and final step, the power supply moves a particle at the e state, and when it falls to the g state it induces an energy-neutral swap where the interior e particle is replaced by a new g particle, restarting the cycle.

Passive systems

When combining a

passive daytime radiative cooling

Passive daytime radiative cooling (PDRC) (also passive radiative cooling, daytime passive radiative cooling, radiative sky cooling, photonic radiative cooling, and terrestrial radiative cooling) is the use of unpowered, reflective/Emissivity, ther ...

system with

thermal insulation and

evaporative cooling, one study found a 300% increase in ambient cooling power when compared to a stand-alone radiative cooling surface, which could extend the

shelf life of food by 40% in

humid climates and 200% in

desert climates without refrigeration. The system's evaporative cooling layer would require water "re-charges" every 10 days to a month in humid areas and every 4 days in hot and dry areas.

Capacity ratings

The refrigeration capacity of a refrigeration system is the product of the

evaporators'

enthalpy rise and the evaporators'

mass flow rate. The measured capacity of refrigeration is often dimensioned in the unit of kW or BTU/h. Domestic and commercial refrigerators may be rated in kJ/s, or Btu/h of cooling. For commercial and industrial refrigeration systems, the kilowatt (kW) is the basic unit of refrigeration, except in North America, where both

ton of refrigeration and BTU/h are used.

A refrigeration system's

coefficient of performance (CoP) is very important in determining a system's overall efficiency. It is defined as refrigeration capacity in kW divided by the energy input in kW. While CoP is a very simple measure of performance, it is typically not used for industrial refrigeration in North America. Owners and manufacturers of these systems typically use performance factor (PF). A system's PF is defined as a system's energy input in horsepower divided by its refrigeration capacity in

TR. Both CoP and PF can be applied to either the entire system or to system components. For example, an individual compressor can be rated by comparing the energy needed to run the compressor versus the expected refrigeration capacity based on inlet volume flow rate. It is important to note that both CoP and PF for a refrigeration system are only defined at specific operating conditions, including temperatures and thermal loads. Moving away from the specified operating conditions can dramatically change a system's performance.

Air conditioning systems used in residential application typically use

SEER (Seasonal Energy Efficiency Ratio)for the energy performance rating. Air conditioning systems for commercial application often use EER (

Energy Efficiency Ratio) and IEER (Integrated Energy Efficiency Ratio) for the energy efficiency performance rating.

See also

*

Air conditioning

Air conditioning, often abbreviated as A/C (US) or air con (UK), is the process of removing heat from an enclosed space to achieve a more comfortable interior temperature, and in some cases, also controlling the humidity of internal air. Air c ...

*

Auto-defrost

*

Beef ring

*

Carnot heat engine

*

Cold chain

*

Coolgardie safe

*

Cryocooler

A cryocooler is a refrigerator designed to reach cryogenic temperatures (below 120 K, -153 °C, -243.4 °F). The term is most often used for smaller systems, typically table-top size, with input powers less than about 20 kW. Some can have inpu ...

*

Darcy friction factor formulae

*

Einstein refrigerator

*

Freezer

*

Heat pump

*

Heat pump and refrigeration cycle

Thermodynamic heat pump cycles or refrigeration cycles are the conceptual and mathematical models for heat pump, air conditioning and refrigeration systems. A heat pump is a mechanical system that transmits heat from one location (the "source") a ...

*

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC ) is the use of various technologies to control the temperature, humidity, and purity of the air in an enclosed space. Its goal is to provide thermal comfort and acceptable indoor air quality. H ...

(HVAC, HVACR)

*

Icebox

*

Icyball

*

Joule–Thomson effect

*

Laser cooling

Laser cooling includes several techniques where atoms, molecules, and small mechanical systems are cooled with laser light. The directed energy of lasers is often associated with heating materials, e.g. laser cutting, so it can be counterintuit ...

*

Pot-in-pot refrigerator

*

Pumpable ice technology

*

Quantum refrigerators

*

Redundant refrigeration system

*

Reefer ship

A reefer ship is a refrigerated cargo ship typically used to transport perishable cargo, which require air conditioning, temperature-controlled handling, such as fruits, meat, vegetables, dairy products, and similar items.

Description

''Types ...

*

Refrigerant

*

Refrigerated container

*

Refrigerator

A refrigerator, commonly shortened to fridge, is a commercial and home appliance consisting of a thermal insulation, thermally insulated compartment and a heat pump (mechanical, electronic or chemical) that transfers heat from its inside to ...

*

Refrigerator car

*

Refrigerator truck

*

Seasonal energy efficiency ratio (SEER)

*

Steam jet cooling

*

Thermoacoustics

*

Vapor-compression refrigeration

*

Working fluid

*

World Refrigeration Day

References

Further reading

*''Refrigeration volume'',

ASHRAE Handbook

The ASHRAE Handbook is the four-volume flagship publication of the nonprofit technical organization ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers). This Handbook is considered the most comprehensive and aut ...

, ASHRAE, Inc., Atlanta, GA

*Stoecker and Jones, ''Refrigeration and Air Conditioning'', Tata-McGraw Hill Publishers

*Mathur, M.L., Mehta, F.S., ''Thermal Engineering'' Vol II

*MSN Encarta Encyclopedia

*

*

*

*

External links

Green Cooling Initiative on alternative natural refrigerants cooling technologies"The Refrigeration", from frigokey

American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE)International Institute of Refrigeration (IIR)British Institute of Refrigeration

* ttps://www.ior.org.uk/ Institute of Refrigeration

{{Authority control

Chemical processes

Cooling technology

Food preservation

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning

Thermodynamics

Refrigeration is any of various types of cooling of a space, substance, or system to lower and/or maintain its

Refrigeration is any of various types of cooling of a space, substance, or system to lower and/or maintain its  The history of artificial refrigeration began when Scottish professor William Cullen designed a small refrigerating machine in 1755. Cullen used a pump to create a partial vacuum over a container of

The history of artificial refrigeration began when Scottish professor William Cullen designed a small refrigerating machine in 1755. Cullen used a pump to create a partial vacuum over a container of