Ptomaine Poisoning on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Foodborne illness (also known as foodborne disease and food poisoning) is any

Foodborne disease can be caused by a number of

Foodborne disease can be caused by a number of

A 2022 study concluded that the practice of washing uncooked chicken actually increases the risk of

A 2022 study concluded that the practice of washing uncooked chicken actually increases the risk of

Governments have the primary mandate of ensuring safe food for all, however all actors in the food chain are responsible to ensure only safe food reaches the consumer, thus preventing foodborne illnesses. This is achieved through the implementation of strict hygiene rules and a public veterinary and phytosanitary service that monitors animal products throughout the

Governments have the primary mandate of ensuring safe food for all, however all actors in the food chain are responsible to ensure only safe food reaches the consumer, thus preventing foodborne illnesses. This is achieved through the implementation of strict hygiene rules and a public veterinary and phytosanitary service that monitors animal products throughout the

** ''Sarcocystis hominis''

** ''Sarcocystis suihominis''

** ''

** ''Sarcocystis hominis''

** ''Sarcocystis suihominis''

** ''

"Codex Committee on Food Hygiene (CCFH)"

European Commission, Retrieved April 7, 2015

International Journal of Food Microbiology

, Elsevier

Foodborne Pathogens and Disease

,

Foodborne diseases, emerging

Foodborne illness information pages

, NSW Food Authority

Food safety and foodborne illness

UK Health protection Agency

US PulseNet

Food poisoning

from NHS Direct Online

Food Safety Network

hosted at the University of Guelph, Canada.

Food Standard Agency website

{{DEFAULTSORT:Foodborne Illness Food safety Health disasters

illness

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

resulting from the contamination of food by pathogenic bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es, or parasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted str ...

s,

as well as prions

A prion () is a misfolded protein that induces misfolding in normal variants of the same protein, leading to cellular death. Prions are responsible for prion diseases, known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSEs), which are fat ...

(the agents of mad cow disease

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly known as mad cow disease, is an incurable and always fatal neurodegenerative disease of cattle. Symptoms include abnormal behavior, trouble walking, and weight loss. Later in the course of th ...

), and toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. They occur especially as proteins, often conjugated. The term was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849–1919), derived ...

s such as aflatoxin

Aflatoxins are various toxicity, poisonous carcinogens and mutagens that are produced by certain Mold (fungus), molds, especially ''Aspergillus'' species such as ''Aspergillus flavus'' and ''Aspergillus parasiticus''. According to the USDA, "The ...

s in peanuts, poisonous mushrooms

Mushroom poisoning is poisoning resulting from the ingestion of mushrooms that contain toxic substances. Symptoms can vary from slight gastrointestinal discomfort to death in about 10 days. Mushroom toxins are secondary metabolites produced by the ...

, and various species of beans

A bean is the seed of some plants in the legume family (Fabaceae) used as a vegetable for human consumption or animal feed. The seeds are often preserved through drying (a ''pulse''), but fresh beans are also sold. Dried beans are tradition ...

that have not been boiled for at least 10 minutes. While contaminants directly cause some symptoms, many effects of foodborne illness result from the body's immune response to these agents, which can vary significantly between individuals and populations based on prior exposure.

Symptoms vary depending on the cause. They often include vomiting

Vomiting (also known as emesis, puking and throwing up) is the forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like food poisoning, gastroenteritis, pre ...

, fever

Fever or pyrexia in humans is a symptom of an anti-infection defense mechanism that appears with Human body temperature, body temperature exceeding the normal range caused by an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, s ...

, aches, and diarrhea

Diarrhea (American English), also spelled diarrhoea or diarrhœa (British English), is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements in a day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration d ...

. Bouts of vomiting can be repeated with an extended delay in between. This is because even if infected food was eliminated from the stomach in the first bout, microbe

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic size, which may exist in its single-celled form or as a colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen microbial life was suspected from antiquity, with an early attestation in ...

s, like bacteria (if applicable), can pass through the stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of Human, humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The Ancient Greek name for the stomach is ''gaster'' which is used as ''gastric'' in medical t ...

into the intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. T ...

and begin to multiply. Some types of microbes stay in the intestine.

For contaminants requiring an incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or ionizing radiation, radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infect ...

, symptoms may not manifest for hours to days, depending on the cause and on the quantity of consumption. Longer incubation periods tend to cause those affected to not associate the symptoms with the item consumed, so they may misattribute the symptoms to gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis, also known as infectious diarrhea, is an inflammation of the Human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract including the stomach and intestine. Symptoms may include diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Fever, lack of ...

, for example.

In low- and middle-income countries in 2010, foodborne disease were responsible for approximately 600 million illnesses and 420,000 deaths, along with an economic loss estimated at US$110 billion annually.

Causes

Foodborne disease can be caused by a number of

Foodborne disease can be caused by a number of bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, such as ''Campylobacter jejuni

''Campylobacter jejuni'' is a species of pathogenic bacteria that is commonly associated with poultry, and is also often found in animal feces. This species of microbe is one of the most common causes of food poisoning in Europe and in the US, w ...

'', and chemicals, such as pesticide

Pesticides are substances that are used to control pests. They include herbicides, insecticides, nematicides, fungicides, and many others (see table). The most common of these are herbicides, which account for approximately 50% of all p ...

s, medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

s, and natural toxic substances, such as vomitoxin

Vomitoxin, also known as deoxynivalenol (DON), is a type B trichothecene, an epoxy-sesquiterpenoid. This mycotoxin occurs predominantly in grains such as wheat, barley, oats, rye, and corn, and less often in rice, sorghum, and triticale. The occ ...

, poisonous mushrooms

Mushroom poisoning is poisoning resulting from the ingestion of mushrooms that contain toxic substances. Symptoms can vary from slight gastrointestinal discomfort to death in about 10 days. Mushroom toxins are secondary metabolites produced by the ...

, or reef fish

Coral reef fish are fish which live amongst or in close relation to coral reefs. Coral reefs form complex ecosystems with tremendous biodiversity. Among the myriad inhabitants, the fish stand out as colourful and interesting to watch. Hundreds ...

.

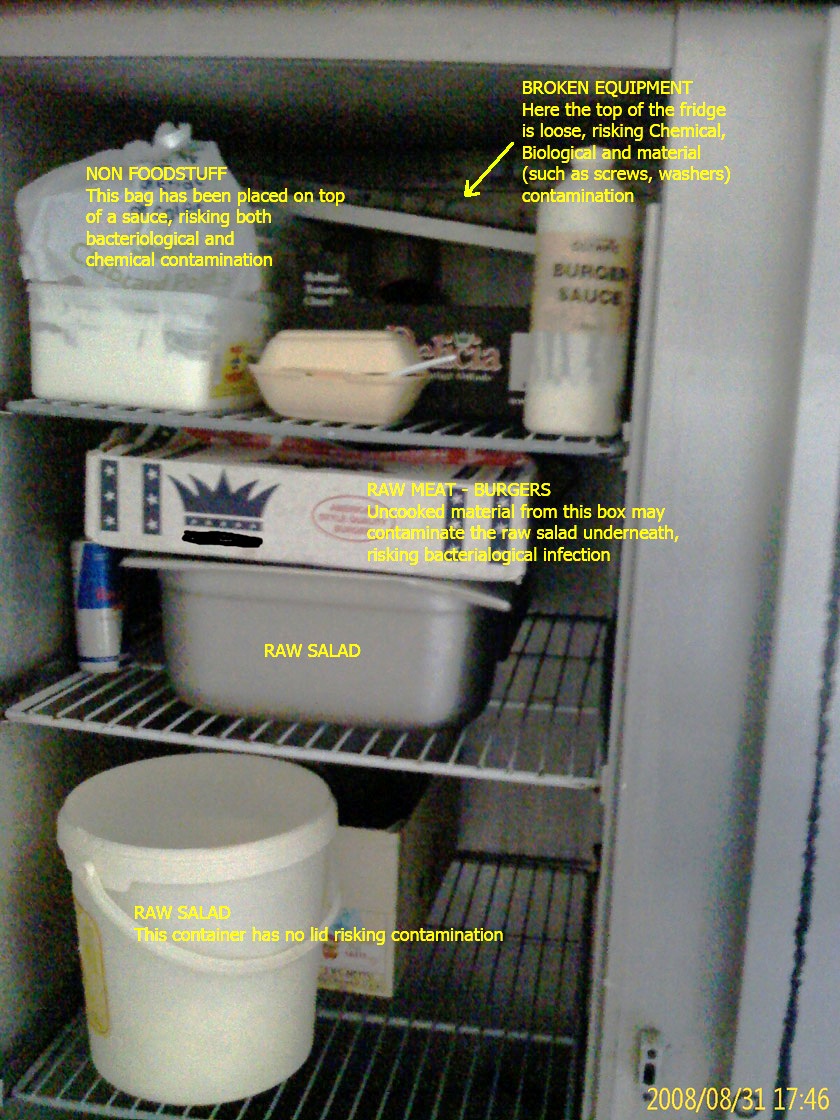

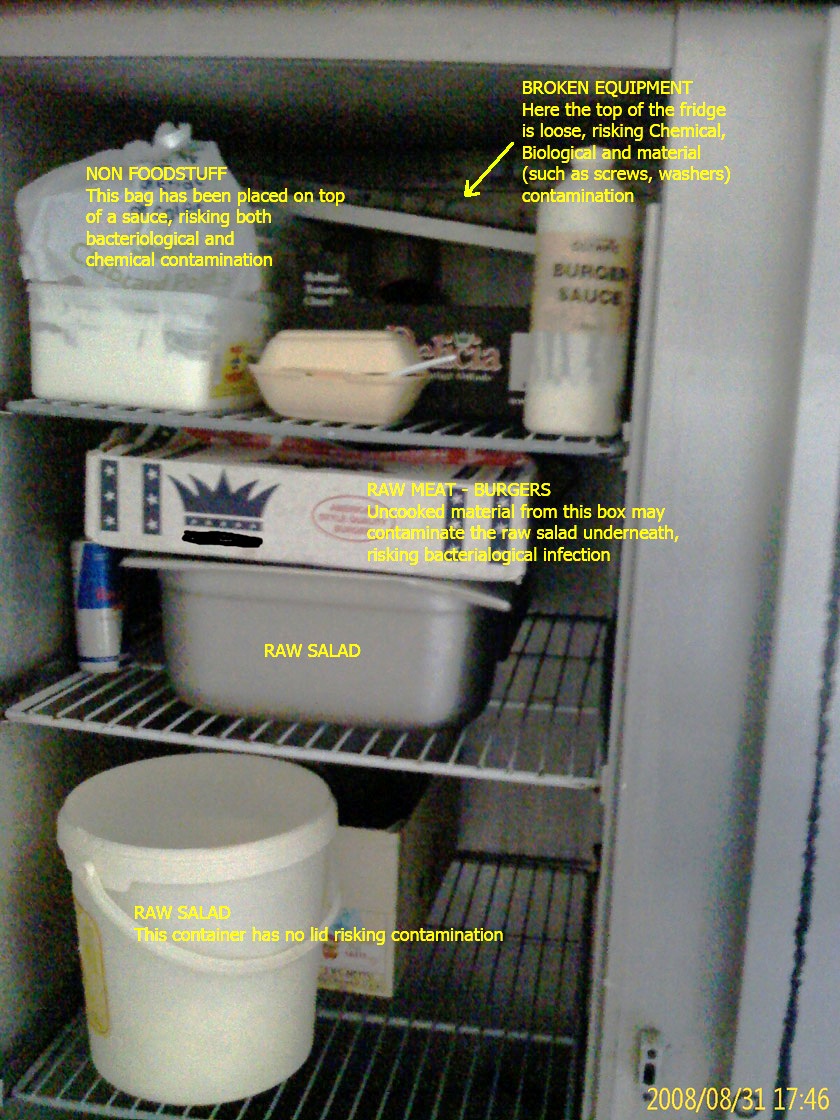

Foodborne illness usually arises from improper handling, preparation, or food storage

Food storage is a way of decreasing the variability of the food supply in the face of natural, inevitable variability. p.507 It allows food to be eaten for some time (typically weeks to months) after harvest rather than solely immediately. I ...

. However, many cases result from the immune system's response to unfamiliar microbes rather than from direct microbial damage, explaining why local populations often tolerate food that sickens travelers.

Good hygiene

Hygiene is a set of practices performed to preserve health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases." Personal hygiene refer ...

practices before, during, and after food preparation can reduce the chances of contracting an illness. There is a consensus in the public health community that regular hand-washing is one of the most effective defenses against the spread of foodborne illness. The action of monitoring food to ensure that it will not cause foodborne illness is known as food safety

Food safety (or food hygiene) is used as a scientific method/discipline describing handling, food processing, preparation, and food storage, storage of food in ways that prevent foodborne illness. The occurrence of two or more cases of a simi ...

.

Bacteria

Bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

are a common cause of foodborne illness. In 2000, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

reported the individual bacteria involved as the following: ''Campylobacter jejuni

''Campylobacter jejuni'' is a species of pathogenic bacteria that is commonly associated with poultry, and is also often found in animal feces. This species of microbe is one of the most common causes of food poisoning in Europe and in the US, w ...

'' 77.3%, ''Salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two known species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' ...

'' 20.9%, ''Escherichia coli'' O157:H7 1.4%, and all others less than 0.56%.

In the past, bacterial infections were thought to be more prevalent because few places had the capability to test for norovirus

Norovirus, also known as Norwalk virus and sometimes referred to as the winter vomiting disease, is the most common cause of gastroenteritis. Infection is characterized by non-bloody diarrhea, vomiting, and stomach pain. Fever or headaches may ...

and no active surveillance was being done for this particular agent. Toxins from bacterial infections are delayed because the bacteria need time to multiply. As a result, symptoms associated with intoxication are usually not seen until 12–72 hours or more after eating contaminated food. However, in some cases, such as Staphylococcal food poisoning, the onset of illness can be as soon as 30 minutes after ingesting contaminated food.

A 2022 study concluded that the practice of washing uncooked chicken actually increases the risk of

A 2022 study concluded that the practice of washing uncooked chicken actually increases the risk of pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

transfer through the splashing of water droplets, with factors such as faucet height, flow type, and surface stiffness affecting the risk of cross-contamination.

The most common bacterial foodborne pathogens are:

* ''Campylobacter jejuni

''Campylobacter jejuni'' is a species of pathogenic bacteria that is commonly associated with poultry, and is also often found in animal feces. This species of microbe is one of the most common causes of food poisoning in Europe and in the US, w ...

'' which can lead to secondary Guillain–Barré syndrome

Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) is a rapid-onset Paralysis, muscle weakness caused by the immune system damaging the peripheral nervous system. Typically, both sides of the body are involved, and the initial symptoms are changes in sensation ...

and periodontitis

Periodontal disease, also known as gum disease, is a set of inflammatory conditions affecting the tissues surrounding the teeth. In its early stage, called gingivitis, the gums become swollen and red and may bleed. It is considered the main c ...

* ''Clostridium perfringens

''Clostridium perfringens'' (formerly known as ''C. welchii'', or ''Bacillus welchii'') is a Gram-positive, bacillus (rod-shaped), anaerobic, spore-forming pathogenic bacterium of the genus '' Clostridium''. ''C. perfringens'' is ever-present ...

'', the "cafeteria germ"

* ''Salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two known species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' ...

'' spp. – its ''S. typhimurium'' infection is caused by consumption of eggs or poultry that are not adequately cooked or by other interactive human-animal pathogens

* '' Escherichia coli O157:H7'' enterohemorrhagic (EHEC) which can cause hemolytic-uremic syndrome

Other common bacterial foodborne pathogens are:

* ''Bacillus cereus

''Bacillus cereus'' is a Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-positive Bacillus, rod-shaped bacterium commonly found in soil, food, and marine sponges. The specific name, ''cereus'', meaning "waxy" in Latin, refers to the appearance of colonies grown o ...

''

* ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Escherichia'' that is commonly fo ...

'', other virulence properties, such as enteroinvasive (EIEC), enteropathogenic (EPEC), enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteroaggregative (EAEC or EAgEC)

* ''Listeria monocytogenes

''Listeria monocytogenes'' is the species of pathogenic bacteria that causes the infection listeriosis. It is a facultative anaerobic bacterium, capable of surviving in the presence or absence of oxygen. It can grow and reproduce inside the ho ...

''

* ''Shigella

''Shigella'' is a genus of bacteria that is Gram negative, facultatively anaerobic, non–spore-forming, nonmotile, rod shaped, and is genetically nested within ''Escherichia''. The genus is named after Kiyoshi Shiga, who discovered it in 1 ...

'' spp.

* ''Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often posi ...

''

* ''Streptococcus

''Streptococcus'' is a genus of gram-positive spherical bacteria that belongs to the family Streptococcaceae, within the order Lactobacillales (lactic acid bacteria), in the phylum Bacillota. Cell division in streptococci occurs along a sing ...

''

* ''Vibrio cholerae

''Vibrio cholerae'' is a species of Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-negative, Facultative anaerobic organism, facultative anaerobe and Vibrio, comma-shaped bacteria. The bacteria naturally live in Brackish water, brackish or saltwater where they att ...

'', including O1 and non-O1

* ''Vibrio parahaemolyticus

''Vibrio parahaemolyticus'' (V. parahaemolyticus) is a curved, rod-shaped, Gram-negative bacterial species found in the sea and in estuaries which, when ingested, may cause gastrointestinal illness in humans. ''V. parahaemolyticus'' is oxidas ...

''

* ''Vibrio vulnificus

''Vibrio vulnificus'' is a species of Gram-negative, motile, curved rod-shaped (vibrio), pathogenic bacteria of the genus ''Vibrio''. Present in marine environments such as estuaries, brackish ponds, or coastal areas, ''V. vulnificus'' is related ...

''

* ''Yersinia enterocolitica

''Yersinia enterocolitica'' is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium, belonging to the family Yersiniaceae. It is motile at temperatures of 22–29 ° C (72–84 °F), but it becomes nonmotile at normal human body temperature. ''Y. enterocolitica ...

'' and '' Yersinia pseudotuberculosis''

Less common bacterial agents:

* ''Brucella

''Brucella'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacterium, bacteria, named after David Bruce (microbiologist), David Bruce (1855–1931). They are small (0.5 to 0.7 by 0.6 to 1.5 μm), non-Bacterial capsule, encapsulated, non-motile, facultatively ...

'' spp.

* ''Corynebacterium ulcerans

''Corynebacterium ulcerans'' is a rod-shaped, aerobic, and Gram-positive bacterium. Most ''Corynebacterium'' species are harmless, but some cause serious illness in humans, especially in immunocompromised humans. ''C. ulcerans'' has been known ...

''

* ''Coxiella burnetii

''Coxiella burnetii'' is an obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen, and is the causative agent of Q fever. The genus ''Coxiella'' is morphologically similar to '' Rickettsia'', but with a variety of physiological differences genetically cla ...

'' or Q fever

* '' Plesiomonas shigelloides''

Emerging foodborne pathogens

* ''Aeromonas hydrophila

''Aeromonas hydrophila'' is a heterotrophic, Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium mainly found in areas with a warm climate. This bacterium can be found in fresh or brackish water. It can survive in aerobic and anaerobic environments, and can ...

'', ''Aeromonas caviae'', ''Aeromonas sobria''

Scandinavian outbreaks of ''Yersinia enterocolitica

''Yersinia enterocolitica'' is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium, belonging to the family Yersiniaceae. It is motile at temperatures of 22–29 ° C (72–84 °F), but it becomes nonmotile at normal human body temperature. ''Y. enterocolitica ...

'' have recently increased to an annual basis, connected to the non-canonical contamination of pre-washed salad.

Preventing bacterial food poisoning

Governments have the primary mandate of ensuring safe food for all, however all actors in the food chain are responsible to ensure only safe food reaches the consumer, thus preventing foodborne illnesses. This is achieved through the implementation of strict hygiene rules and a public veterinary and phytosanitary service that monitors animal products throughout the

Governments have the primary mandate of ensuring safe food for all, however all actors in the food chain are responsible to ensure only safe food reaches the consumer, thus preventing foodborne illnesses. This is achieved through the implementation of strict hygiene rules and a public veterinary and phytosanitary service that monitors animal products throughout the food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web, often starting with an autotroph (such as grass or algae), also called a producer, and typically ending at an apex predator (such as grizzly bears or killer whales), detritivore (such as ...

, from farming to delivery in shops and restaurants. This regulation includes:

* traceability

Traceability is the capability to trace something. In some cases, it is interpreted as the ability to verify the history, location, or application of an item by means of documented recorded identification.

Other common definitions include the capa ...

: the origin of the ingredients (farm of origin, identification of the crop or animal) and where and when it has been processed must be known in the final product; in this way, the origin of the disease can be traced and resolved (and possibly penalized), and the final products can be removed from sale if a problem is detected;

* enforcement of hygiene procedures such as HACCP

Hazard analysis and critical control points, or HACCP (), is a systematic preventive approach to food safety from biological hazard, biological, chemical hazard, chemical, and physical hazards in production processes that can cause the finished ...

and the "cold chain

A cold chain is a supply chain that uses refrigeration to maintain perishable goods, such as pharmaceuticals, produce or other goods that are temperature-sensitive. Common goods, sometimes called cool cargo, distributed in cold chains include fr ...

";

* power of control and of law enforcement of veterinarian

A veterinarian (vet) or veterinary surgeon is a medical professional who practices veterinary medicine. They manage a wide range of health conditions and injuries in non-human animals. Along with this, veterinarians also play a role in animal r ...

s.

In August 2006, the United States Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respo ...

approved phage therapy

Phage therapy, viral phage therapy, or phagotherapy is the therapeutic use of bacteriophages for the treatment of pathogenic bacterial infections. This therapeutic approach emerged at the beginning of the 20th century but was progressively r ...

which involves spraying meat with viruses that infect bacteria, and thus preventing infection. This has raised concerns because without mandatory labeling, consumers would not know that meat and poultry products have been treated with the spray.

At home, prevention mainly consists of good food safety

Food safety (or food hygiene) is used as a scientific method/discipline describing handling, food processing, preparation, and food storage, storage of food in ways that prevent foodborne illness. The occurrence of two or more cases of a simi ...

practices. Many forms of bacterial poisoning can be prevented by cooking food sufficiently, and either eating it quickly or refrigerating it effectively. Many toxins, however, are not destroyed by heat treatment.

Techniques that help prevent food borne illness in the kitchen are hand washing, rinsing produce

In American English, produce generally refers to wikt:fresh, fresh List of culinary fruits, fruits and Vegetable, vegetables intended to be Eating, eaten by humans, although other food products such as Dairy product, dairy products or Nut (foo ...

, preventing cross-contamination, proper storage, and maintaining cooking temperatures. In general, freezing or refrigerating prevents virtually all bacteria from growing, and heating food sufficiently kills parasites, viruses, and most bacteria. Bacteria grow most rapidly at the range of temperatures between , called the "danger zone". Storing food below or above the "danger zone" can effectively limit the production of toxins. For storing leftovers, the food must be put in shallow containers

for quick cooling and must be refrigerated within two hours. When food is reheated, it must reach an internal temperature of or until hot or steaming to kill bacteria.

Enterotoxins

Enterotoxin

An enterotoxin is a protein exotoxin released by a microorganism that targets the intestines. They can be chromosomally or plasmid encoded. They are heat labile (> 60 °C), of low molecular weight and water-soluble. Enterotoxins are frequently cy ...

s are potent compounds produced by various microorganisms that specifically target and damage the intestines, causing many of the most rapid and severe forms of food poisoning. Unlike bacterial infections that require live organisms to multiply in the gut, enterotoxins (a type of exotoxin

An exotoxin is a toxin secreted by bacteria. An exotoxin can cause damage to the host by destroying cells or disrupting normal cellular metabolism. They are highly potent and can cause major damage to the host. Exotoxins may be secreted, or, sim ...

) can cause illness even when the bacteria that produced them have been killed through cooking or other preservation methods.

Enterotoxins can produce illness even when the microbes that produced them have been killed. Symptom onset varies with the toxin but may be rapid in onset, as in the case of enterotoxins of ''Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often posi ...

'' in which symptoms appear in one to six hours. This causes intense vomiting

Vomiting (also known as emesis, puking and throwing up) is the forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like food poisoning, gastroenteritis, pre ...

including or not including diarrhea (resulting in staphylococcal enteritis

Staphylococcal enteritis is an inflammation that is usually caused by eating or drinking substances contaminated with staph enterotoxin. The toxin, not the bacterium, settles in the small intestine and causes inflammation and swelling. This in tu ...

), and staphylococcal enterotoxins (most commonly staphylococcal enterotoxin A

''Staphylococcus'', from Ancient Greek σταφυλή (''staphulḗ''), meaning "bunch of grapes", and (''kókkos''), meaning "kernel" or " Kermes", is a genus of Gram-positive bacteria in the family Staphylococcaceae from the order Bacillales ...

but also including staphylococcal enterotoxin B

In the field of molecular biology, enterotoxin type B, also known as Staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), is an enterotoxin produced by the gram-positive bacteria ''Staphylococcus aureus''. It is a common cause of food poisoning, with severe di ...

) are the most commonly reported enterotoxins although cases of poisoning are likely underestimated. It occurs mainly in cooked and processed foods due to competition with other biota in raw foods, and humans are the main cause of contamination as a substantial percentage of humans are persistent carriers of ''S. aureus''. The CDC has estimated about 240,000 cases per year in the United States.

* ''Clostridium botulinum

''Clostridium botulinum'' is a Gram-positive bacteria, gram-positive, Bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, Anaerobic organism, anaerobic, endospore, spore-forming, Motility, motile bacterium with the ability to produce botulinum toxin, which is a neurot ...

''

* ''Clostridium perfringens

''Clostridium perfringens'' (formerly known as ''C. welchii'', or ''Bacillus welchii'') is a Gram-positive, bacillus (rod-shaped), anaerobic, spore-forming pathogenic bacterium of the genus '' Clostridium''. ''C. perfringens'' is ever-present ...

''

* ''Bacillus cereus

''Bacillus cereus'' is a Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-positive Bacillus, rod-shaped bacterium commonly found in soil, food, and marine sponges. The specific name, ''cereus'', meaning "waxy" in Latin, refers to the appearance of colonies grown o ...

''

The rare but potentially deadly disease botulism

Botulism is a rare and potentially fatal illness caused by botulinum toxin, which is produced by the bacterium ''Clostridium botulinum''. The disease begins with weakness, blurred vision, Fatigue (medical), feeling tired, and trouble speaking. ...

occurs when the anaerobic

Anaerobic means "living, active, occurring, or existing in the absence of free oxygen", as opposed to aerobic which means "living, active, or occurring only in the presence of oxygen." Anaerobic may also refer to:

*Adhesive#Anaerobic, Anaerobic ad ...

bacterium ''Clostridium botulinum

''Clostridium botulinum'' is a Gram-positive bacteria, gram-positive, Bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, Anaerobic organism, anaerobic, endospore, spore-forming, Motility, motile bacterium with the ability to produce botulinum toxin, which is a neurot ...

'' grows in improperly canned low-acid foods and produces botulin

Botulinum toxin, or botulinum neurotoxin (commonly called botox), is a neurotoxic protein produced by the bacterium ''Clostridium botulinum'' and related species. It prevents the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine from axon endi ...

, a powerful paralytic toxin.

''Pseudoalteromonas tetraodonis'', certain species of ''Pseudomonas

''Pseudomonas'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria belonging to the family Pseudomonadaceae in the class Gammaproteobacteria. The 348 members of the genus demonstrate a great deal of metabolic diversity and consequently are able to colonize a ...

'' and ''Vibrio

''Vibrio'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria, which have a characteristic curved-rod (comma) shape, several species of which can cause foodborne infection or soft-tissue infection called Vibriosis. Infection is commonly associated with eati ...

'', and some other bacteria, produce the lethal tetrodotoxin

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is a potent neurotoxin. Its name derives from Tetraodontiformes, an Order (biology), order that includes Tetraodontidae, pufferfish, porcupinefish, ocean sunfish, and triggerfish; several of these species carry the toxin. Alt ...

, which is present in the tissues of some living animal species rather than being a product of decomposition

Decomposition is the process by which dead organic substances are broken down into simpler organic or inorganic matter such as carbon dioxide, water, simple sugars and mineral salts. The process is a part of the nutrient cycle and is ess ...

.

Cultural adaptation and food safety

Traditional preservation methods like fermentation, sun-drying, and smoking have been used for centuries. These methods not only preserve food but also enhance nutritional value and can reduce foodborne illnesses by creating environments that inhibit harmful bacteria. The notion that modern food safety standards are universally applicable is challenged by the effectiveness of these traditional methods. In cultures without access to modern refrigeration, traditional preservation techniques adapted to local climates and resources have proven effective in preventing spoilage and illness. Community knowledge and social practices can be as critical as technical standards in ensuring food safety, differing significantly from the regulatory focus in Western systems.Mycotoxins and alimentary mycotoxicoses

The termalimentary mycotoxicosis

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. T ...

refers to the effect of poisoning by mycotoxin

A mycotoxin (from the Greek μύκης , "fungus" and τοξικός , "poisonous") is a toxic secondary metabolite produced by fungi and is capable of causing disease and death in both humans and other animals. The term 'mycotoxin' is usually rese ...

s through food consumption. The term mycotoxin is usually reserved for the toxic chemical compounds naturally produced by fungi that readily colonize crops under specific temperature and moisture conditions.

Mycotoxins can have severe effects on human and animal health. For example, an outbreak which occurred in the UK during 1960 caused the death of 100,000 turkeys which had consumed aflatoxin

Aflatoxins are various toxicity, poisonous carcinogens and mutagens that are produced by certain Mold (fungus), molds, especially ''Aspergillus'' species such as ''Aspergillus flavus'' and ''Aspergillus parasiticus''. According to the USDA, "The ...

-contaminated peanut meal. In the USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, 5,000 people died due to alimentary toxic aleukia (ALA). In Kenya, mycotoxins led to the death of 125 people in 2004, after consumption of contaminated grains.

In animals, mycotoxicosis targets organ systems such as the liver and digestive system. Other effects can include reduced productivity and suppression of the immune system, thus pre-disposing the animals to other secondary infections.

The common foodborne Mycotoxins

A mycotoxin (from the Greek μύκης , "fungus" and τοξικός , "poisonous") is a toxic secondary metabolite produced by fungi and is capable of causing disease and death in both humans and other animals. The term 'mycotoxin' is usually r ...

include:

* Aflatoxin

Aflatoxins are various toxicity, poisonous carcinogens and mutagens that are produced by certain Mold (fungus), molds, especially ''Aspergillus'' species such as ''Aspergillus flavus'' and ''Aspergillus parasiticus''. According to the USDA, "The ...

s – originating from ''Aspergillus parasiticus

''Aspergillus'' () is a genus consisting of several hundred mold species found in various climates worldwide.

''Aspergillus'' was first catalogued in 1729 by the Italian priest and biologist Pier Antonio Micheli. Viewing the fungi under a microsc ...

'' and ''Aspergillus flavus

''Aspergillus flavus'' is a saprotrophic and pathogenic fungus with a cosmopolitan distribution. It is best known for its colonization of cereal grains, legumes, and tree nuts. Postharvest rot typically develops during harvest, storage, and/or ...

''. They are frequently found in tree nuts, peanuts, maize, sorghum and other oilseeds, including corn and cottonseeds. The pronounced forms of aflatoxins are those of B1, B2, G1, and G2, amongst which Aflatoxin B1 predominantly targets the liver, which will result in necrosis

Necrosis () is a form of cell injury which results in the premature death of cells in living tissue by autolysis. The term "necrosis" came about in the mid-19th century and is commonly attributed to German pathologist Rudolf Virchow, who i ...

, cirrhosis

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, chronic liver failure or chronic hepatic failure and end-stage liver disease, is a chronic condition of the liver in which the normal functioning tissue, or parenchyma, is replaced ...

, and carcinoma

Carcinoma is a malignancy that develops from epithelial cells. Specifically, a carcinoma is a cancer that begins in a tissue that lines the inner or outer surfaces of the body, and that arises from cells originating in the endodermal, mesoder ...

. Other forms of aflatoxins exist as metabolites

In biochemistry, a metabolite is an intermediate or end product of metabolism.

The term is usually used for small molecules. Metabolites have various functions, including fuel, structure, signaling, stimulatory and inhibitory effects on enzymes, c ...

such as Aflatoxin M1.

In the US, the acceptable level of total aflatoxins in foods is less than 20'' ''μg/kg, except for Aflatoxin M1 in milk, which should be less than 0.5'' ''μg/kg. The European union has more stringent standards, set at 10 μg/kg in cereals and cereal products. These references are also adopted in other countries.

* Altertoxins – are those of alternariol

Alternariol (commonly abbreviated as AOH) is a toxic metabolite of ''Alternaria'' fungi. It is an important contaminant in cereals and fruits.

Alternariol exhibits antifungal and phytotoxic activity. It is reported to inhibit cholinesterase enz ...

(AOH), alternariol methyl ether

Alternariol (commonly abbreviated as AOH) is a toxic metabolite of ''Alternaria'' fungi. It is an important contaminant in cereals and fruits.

Alternariol exhibits antifungal and phytotoxic activity. It is reported to inhibit cholinesterase enz ...

(AME), altenuene (ALT), altertoxin-1 (ATX-1), tenuazonic acid (TeA), and radicinin (RAD), originating from ''Alternaria

''Alternaria'' is a genus of Deuteromycetes fungi. All species are known as major Phytopathology, plant pathogens. They are also common allergens in humans, growing indoors and causing hay fever or hypersensitivity reactions that sometimes lead t ...

'' spp. Some of the toxins can be present in sorghum, ragi, wheat and tomatoes.

Some research has shown that the toxins can be easily cross-contaminated between grain commodities, suggesting that manufacturing and storage of grain commodities is a critical practice.

* Citrinin

Citrinin is a mycotoxin which is often found in food. It is a secondary metabolite produced by fungi that contaminates long-stored food and it can cause a variety of toxic effects, including kidney, liver and cell damage. Citrinin is mainly found ...

* Citreoviridin

Citreoviridin is a mycotoxin which is produced by ''Penicillium'' and ''Aspergillus

' () is a genus consisting of several hundred mold species found in various climates worldwide.

''Aspergillus'' was first catalogued in 1729 by the Italian pri ...

* Cyclopiazonic acid

* Cytochalasin

Cytochalasins are fungal metabolites that have the ability to bind to actin filaments and block polymerization and the elongation of actin. As a result of the inhibition of actin polymerization, cytochalasins can change cellular morphology, inhibi ...

s

* Ergot alkaloid

Ergoline is a core structure in many alkaloids and their synthetic derivatives. Ergoline alkaloids were first characterized in ergot. Some of these are implicated in the condition of ergotism, which can take a convulsive form or a gangrenous for ...

s / ergopeptine

Ergoline is a core structure in many alkaloids and their synthetic derivatives. Ergoline alkaloids were first characterized in ergot. Some of these are implicated in the condition of ergotism, which can take a convulsive form or a gangrenous for ...

alkaloids

Alkaloids are a broad class of naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large variety of organisms i ...

– ergotamine

Ergotamine, sold under the brand name Ergomar among others, is an ergopeptine and part of the ergot family of alkaloids; it is structurally and biochemically closely related to ergoline. It is structurally similar to several neurotransmitter ...

* Fumonisin

The fumonisins are a group of mycotoxins derived from ''Fusarium'' and their Liseola section. They have strong structural similarity to sphinganine, the backbone precursor of sphingolipids.

More specifically, it can refer to:

* Fumonisin B1 ...

s – Crop corn can be easily contaminated by the fungi ''Fusarium moniliforme

''Fusarium verticillioides'' is the most commonly reported fungal species infecting maize (''Zea mays''). ''Fusarium verticillioides'' is the accepted name of the species, which was also known as ''Fusarium moniliforme''. The species has also bee ...

'', and its fumonisin B1

Fumonisin B1 is the most prevalent member of a family of toxins, known as fumonisins, produced by multiple species of ''Fusarium'' Mold (fungus), molds, such as ''Fusarium verticillioides'', which occur mainly in maize (corn), wheat and other cere ...

will cause leukoencephalomalacia (LEM) in horses, pulmonary edema syndrome (PES) in pigs, liver cancer in rats and esophageal cancer

Esophageal cancer (American English) or oesophageal cancer (British English) is cancer arising from the esophagus—the food pipe that runs between the throat and the stomach. Symptoms often include dysphagia, difficulty in swallowing and weigh ...

in humans. For human and animal health, both the FDA

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food ...

and the EC have regulated the content levels of toxins in food and animal feed.

* Fusaric acid

Fusaric acid is a picolinic acid derivative and an antibiotic (wilting agent) first isolated from the fungus '' Fusarium heterosporium''.

It is typically isolated from various Fusarium species, and has been proposed for a various therapeutic appl ...

* Fusarochromanone

* Kojic acid

Kojic acid is an organic compound with the formula . It is a derivative of 4-Pyrone, 4-pyrone that functions in nature as a chelation agent produced by several species of fungus, especially ''Aspergillus oryzae'', which has the Japanese common na ...

* Lolitrem alkaloid

Lolitrem B is one of many Mycotoxin, toxins produced by a fungus called Epichloë festucae var. lolii, ''Epichloë festucae'' var. ''lolii''), which grows in ''Lolium perenne'' (perennial ryegrass). The fungus is symbiotic with the ryegrass; it d ...

s

* Moniliformin

Moniliformin is the organic compound with the formula (M+ = K+ or Na+). Both the sodium and potassium salts are generally hydrated, e.g. . In terms of its structure, it is the alkali metal salt of the conjugate base of 3-hydroxy-1,2-cyclobutene ...

* 3-Nitropropionic acid

3-Nitropropionic acid (3-NPA) is a mycotoxin, a potent mitochondrial inhibitor, which is toxic to humans. It is produced by a number of fungi, and may be found in food such as in sugar cane as well as Japanese fungally fermented staples, includin ...

* Nivalenol

Nivalenol (NIV) is a mycotoxin of the trichothecene group. In nature it is mainly found in fungi of the ''Fusarium'' species. The ''Fusarium'' species belongs to the most prevalent mycotoxin producing fungi in the temperate regions of the norther ...

* Ochratoxins – In Australia, The Limit of Reporting (LOR) level for ochratoxin A

Ochratoxin A—a toxin produced by different ''Aspergillus'' and ''Penicillium'' species — is one of the most-abundant food-contaminating mycotoxins. It is also a frequent contaminant of water-damaged houses and of heating ducts. Human exposure ...

(OTA) analyses in 20th Australian Total Diet Survey was 1 μg/kg, whereas the EC restricts the content of OTA to 5 μg/kg in cereal commodities, 3 μg/kg in processed products and 10 μg/kg in dried vine fruits.

* Oosporeine

* Patulin

Patulin is an organic compound classified as a polyketide. It is named after the fungus from which it was isolated, '' Penicillium patulum''. It is a white powder soluble in acidic water and in organic solvents. It is a lactone that is heat-stabl ...

– Currently, this toxin has been advisably regulated on fruit products. The EC and the FDA

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food ...

have limited it to under 50 μg/kg for fruit juice and fruit nectar, while limits of 25 μg/kg for solid-contained fruit products and 10 μg/kg for baby foods were specified by the EC.

* Phomopsins

* Sporidesmin A

* Sterigmatocystin

* Tremorgenic mycotoxins – Five of them have been reported to be associated with molds found in fermented meats. These are fumitremorgen B, paxilline

Paxilline is a toxic, tremorgenic diterpene indole polycyclic alkaloid molecule produced by '' Penicillium paxilli ''which was first characterized in 1975. Paxilline is one of a class of tremorigenic mycotoxins, is a potassium channel blocker, ...

, penitrem A, verrucosidin

Verrucosidin is a toxic pyrone-type polyketide produced by ''Penicillium aurantiogriseum'', ''Penicillium melanoconidium'', and ''Penicillium polonicum''.

References

2-Pyrones

Epoxides

Penicillium, Verrucosidin

Polyketides

Heterocyclic comp ...

, and verruculogen.

* Trichothecene

Trichothecenes constitute a large group of chemically related mycotoxins. They are produced by Fungus, fungi of the genera ''Fusarium'', ''Myrothecium'', ''Trichoderma'', ''Podostroma'', ''Trichothecium'', ''Cephalosporium'', ', ''Stachybotrys'' ...

s – sourced from ''Cephalosporium'', ''Fusarium

''Fusarium'' (; ) is a large genus of filamentous fungi, part of a group often referred to as hyphomycetes, widely distributed in soil and associated with plants. Most species are harmless saprobes, and are relatively abundant members of the s ...

'', ''Myrothecium'', ''Stachybotrys

''Stachybotrys'' () is a genus of molds, hyphomycetes or asexually reproducing, filamentous fungi, now placed in the family Stachybotryaceae. The genus was erected by August Carl Joseph Corda in 1837. Historically, it was considered closely ...

'', and ''Trichoderma

''Trichoderma'' is a genus of fungi in the family Hypocreaceae that is present in all soils, where they are the most prevalent culturable fungi. Many species in this genus can be characterized as opportunistic avirulent plant symbionts. This re ...

''. The toxins are usually found in molded maize, wheat, corn, peanuts and rice, or animal feed of hay and straw.

Four trichothecenes, T-2 toxin, HT-2 toxin, diacetoxyscirpenol (DAS), and deoxynivalenol

Vomitoxin, also known as deoxynivalenol (DON), is a type B trichothecene, an epoxy- sesquiterpenoid. This mycotoxin occurs predominantly in grains such as wheat, barley, oats, rye, and corn, and less often in rice, sorghum, and triticale. The o ...

(DON) have been most commonly encountered by humans and animals. The consequences of oral intake of, or dermal exposure to, the toxins will result in alimentary toxic aleukia, neutropenia

Neutropenia is an abnormally low concentration of neutrophils (a type of white blood cell) in the blood. Neutrophils make up the majority of circulating white blood cells and serve as the primary defense against infections by destroying bacteria ...

, aplastic anemia

Aplastic anemia (AA) is a severe hematologic condition in which the body fails to make blood cells in sufficient numbers.

Normally, blood cells are produced in the bone marrow by stem cells that reside there, but patients with aplastic anemia ...

, thrombocytopenia

In hematology, thrombocytopenia is a condition characterized by abnormally low levels of platelets (also known as thrombocytes) in the blood. Low levels of platelets in turn may lead to prolonged or excessive bleeding. It is the most common coag ...

and/or skin irritation. In 1993, the FDA

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food ...

issued a document for the content limits of DON in food and animal feed at an advisory level. In 2003, US published a patent that is very promising for farmers to produce a trichothecene-resistant crop.Hohn, Thomas M. "Trichothecene-resistant transgenic plants". . Priority date March 31, 1999.

* Zearalenone

Zearalenone (ZEN), also known as RAL and F-2 mycotoxin, is a potent estrogenic metabolite produced by some ''Fusarium'' and '' Gibberella'' species. Specifically, the '' Gibberella zeae'', the fungal species where zearalenone was initially detec ...

* Zearalenol Zearalenol may refer to:

* α-Zearalenol

* β-Zearalenol

See also

* Zearalanol

* Zearalenone

* Zearalanone

Zearalanone (ZAN) is a mycoestrogen that is a derivative of zearalenone (ZEN). Zearalanone can be extracted from foodstuffs along with a ...

s

Viruses

Viral infections make up perhaps one third of cases of food poisoning in developed countries. In the US, more than 50% of cases are viral andnoroviruses

Norovirus, also known as Norwalk virus and sometimes referred to as the winter vomiting disease, is the most common cause of gastroenteritis. Infection is characterized by non-bloody diarrhea, vomiting, and stomach pain. Fever or headaches may ...

are the most common foodborne illness, causing 57% of outbreaks in 2004. Foodborne viral infection are usually of intermediate (1–3 days) incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or ionizing radiation, radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infect ...

, causing illnesses which are self-limited in otherwise healthy individuals; they are similar to the bacterial forms described above.

* Enterovirus

''Enterovirus'' is a genus of positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses associated with several human and mammalian diseases. Enteroviruses are named by their transmission-route through the intestine ('enteric' meaning intestinal).

Serologic ...

* Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is an infectious liver disease caused by Hepatitis A virus (HAV); it is a type of viral hepatitis. Many cases have few or no symptoms, especially in the young. The time between infection and symptoms, in those who develop them, is ...

is distinguished from other viral causes by its prolonged (2–6 week) incubation period and its ability to spread beyond the stomach and intestines into the liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

. It often results in jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or, less frequently, greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving ...

, or yellowing of the skin, but rarely leads to chronic liver dysfunction. The virus has been found to cause infection due to the consumption of fresh-cut produce which has fecal contamination.

* Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E is inflammation of the liver caused by infection with the hepatitis E virus (HEV); it is a type of viral hepatitis. Hepatitis E has mainly a fecal-oral transmission route that is similar to hepatitis A, although the viruses are u ...

* Norovirus

Norovirus, also known as Norwalk virus and sometimes referred to as the winter vomiting disease, is the most common cause of gastroenteritis. Infection is characterized by non-bloody diarrhea, vomiting, and stomach pain. Fever or headaches may ...

* Rotavirus

Rotaviruses are the most common cause of diarrhea, diarrhoeal disease among infants and young children. Nearly every child in the world is infected with a rotavirus at least once by the age of five. Immunity (medical), Immunity develops with ...

Parasites

Most foodborneparasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted str ...

s are zoonoses

A zoonosis (; plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a virus, bacterium, parasite, fungi, or prion) that can jump from a non-human vertebrate to a human. When h ...

.

* Platyhelminthes

Platyhelminthes (from the Greek πλατύ, ''platy'', meaning "flat" and ἕλμινς (root: ἑλμινθ-), ''helminth-'', meaning "worm") is a phylum of relatively simple bilaterian, unsegmented, soft-bodied invertebrates commonly called f ...

:

** ''Diphyllobothrium

''Diphyllobothrium'' is a genus of cestoda, tapeworms which can cause diphyllobothriasis in humans through consumption of wikt:raw, raw or undercooked fish. The principal species causing diphyllobothriasis is ''D. latum'', known as the broad ...

'' sp.

** ''Nanophyetus'' sp.

** ''Taenia saginata

''Taenia saginata'' (synonym ''Taeniarhynchus saginatus''), commonly known as the beef tapeworm, is a zoonotic tapeworm belonging to the order Cyclophyllidea and genus ''Taenia''. It is an intestinal parasite in humans causing taeniasis (a type ...

''

** ''Taenia solium

''Taenia solium'', the pork tapeworm, belongs to the cyclophyllid cestode family Taeniidae. It is found throughout the world and is most common in countries where pork is eaten. It is a tapeworm that uses humans (''Homo sapiens'') as its definit ...

''

** ''Fasciola hepatica

''Fasciola hepatica'', also known as the common liver fluke or sheep liver fluke, is a parasitism, parasitic trematode (fluke (flatworm), fluke or flatworm, a type of helminth) of the class (biology), class Trematoda, phylum Platyhelminthes. It ...

''

** See also: Tapeworm

Eucestoda, commonly referred to as tapeworms, is the larger of the two subclasses of flatworms in the class Cestoda (the other subclass being Cestodaria). Larvae have six posterior hooks on the scolex (head), in contrast to the ten-hooked Ce ...

and Flatworm

Platyhelminthes (from the Greek language, Greek πλατύ, ''platy'', meaning "flat" and ἕλμινς (root: ἑλμινθ-), ''helminth-'', meaning "worm") is a Phylum (biology), phylum of relatively simple bilaterian, Segmentation (biology), ...

* Nematode

The nematodes ( or ; ; ), roundworms or eelworms constitute the phylum Nematoda. Species in the phylum inhabit a broad range of environments. Most species are free-living, feeding on microorganisms, but many are parasitic. Parasitic worms (h ...

:

** ''Anisakis

''Anisakis'' ( ) is a genus of parasitic nematodes that have life cycles involving fish and marine mammals. They are infective to humans and cause #Anisakiasis, anisakiasis. People who produce immunoglobulin E in response to this parasite may su ...

'' sp.

** ''Ascaris lumbricoides

''Ascaris lumbricoides'' is a large parasitic worm, parasitic Nematoda, roundworm of the genus ''Ascaris.'' It is the most common parasitic worm in humans. An estimated 807 million–1.2 billion people are infected with ''Ascaris lumbricoides'' ...

''

** ''Eustrongylides

''Eustrongylides'' is a genus of nematodes belonging to the family Dioctophymidae. The species of this genus cause eustrongylidosis.

The genus has almost cosmopolitan distribution.

Species:

*''Eustrongylides excisus''

*''Eustrongylides ignotu ...

'' sp.

** ''Toxocara

The Toxocaridae are a zoonotic family of parasitic nematodes that infect canids and felids and which cause toxocariasis in humans ( visceral larva migrans and ocular larva migrans). The worms are unable to reproduce in humans.

Notable species ...

''

** ''Trichinella spiralis

''Trichinella spiralis'' is a viviparous nematode parasite, occurring in rodents, pigs, bears, hyenas and humans, and is responsible for the disease trichinosis. It is sometimes referred to as the "pork worm" due to it being typically encount ...

''

** ''Trichuris trichiura

''Trichuris trichiura, Trichocephalus trichiuris'' or whipworm, is a parasitic roundworm (a type of helminth) that causes trichuriasis (a type of helminthiasis which is one of the neglected tropical diseases) when it infects a human large inte ...

''

* Protozoa

Protozoa (: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically ...

:

** ''Acanthamoeba

''Acanthamoeba'' is a genus of amoeboid, amoebae that are commonly recovered from soil, fresh water, and other habitat (ecology), habitats.

The genus ''Acanthamoeba'' has two stages in its life cycle, the metabolically active trophozoite stage a ...

'' and other free-living amoeba

An amoeba (; less commonly spelled ameba or amœba; : amoebas (less commonly, amebas) or amoebae (amebae) ), often called an amoeboid, is a type of Cell (biology), cell or unicellular organism with the ability to alter its shape, primarily by ...

e

** ''Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidiosis, sometimes informally called crypto, is a parasitic disease caused by ''Cryptosporidium'', a genus of protozoan parasites in the phylum Apicomplexa. It affects the ileum, distal small intestine and can affect the respiratory tr ...

''

** ''Cyclospora cayetanensis

''Cyclospora cayetanensis'' is a coccidian parasite that causes a diarrheal disease called cyclosporiasis in humans and possibly in other primates. Originally reported as a novel pathogen of probable coccidian nature in the 1980s and described i ...

''

** ''Entamoeba histolytica

''Entamoeba histolytica'' is an anaerobic organism, anaerobic parasitic amoebozoan, part of the genus ''Entamoeba''. Predominantly infecting humans and other primates causing amoebiasis, ''E. histolytica'' is estimated to infect about 35-50 mil ...

''

** ''Giardia lamblia

''Giardia duodenalis'', also known as ''Giardia intestinalis'' and ''Giardia lamblia'', is a flagellated Parasitism, parasitic protozoan microorganism of the genus ''Giardia'' that colonizes the small intestine, causing a diarrheal condition kn ...

'' ** ''Sarcocystis hominis''

** ''Sarcocystis suihominis''

** ''

** ''Sarcocystis hominis''

** ''Sarcocystis suihominis''

** ''Toxoplasma

''Toxoplasma gondii'' () is a species of parasitic alveolate that causes toxoplasmosis. Found worldwide, ''T. gondii'' is capable of infecting virtually all warm-blooded animals, but members of the cat family (felidae) are the only known d ...

''

Natural toxins

Several foods can naturally containtoxins

A toxin is a naturally occurring poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. They occur especially as proteins, often conjugated. The term was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849–1919), derived ...

, many of which are not produced by bacteria. Plants in particular may be toxic; animals which are naturally poisonous to eat are rare. In evolutionary terms, animals can escape being eaten by fleeing; plants can use only passive defenses such as poisons and distasteful substances, for example capsaicin

Capsaicin (8-methyl-''N''-vanillyl-6-nonenamide) (, rarely ) is an active component of chili peppers, which are plants belonging to the genus ''Capsicum''. It is a potent Irritation, irritant for Mammal, mammals, including humans, and produces ...

in chili pepper

Chili peppers, also spelled chile or chilli ( ), are varieties of fruit#Berries, berry-fruit plants from the genus ''Capsicum'', which are members of the nightshade family Solanaceae, cultivated for their pungency. They are used as a spice to ...

s and pungent sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

compounds in garlic

Garlic (''Allium sativum'') is a species of bulbous flowering plants in the genus '' Allium''. Its close relatives include the onion, shallot, leek, chives, Welsh onion, and Chinese onion. Garlic is native to central and south Asia, str ...

and onion

An onion (''Allium cepa'' , from Latin ), also known as the bulb onion or common onion, is a vegetable that is the most widely cultivated species of the genus '' Allium''. The shallot is a botanical variety of the onion which was classifie ...

s. Most animal poisons are not synthesised by the animal, but acquired by eating poisonous plants to which the animal is immune, or by bacterial action.

* Alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

s

* Ciguatera poisoning

Ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP), also known as ciguatera, is a foodborne illness caused by eating tropical reef fish contaminated with ciguatoxins. Such individual fish are said to be ciguatoxic. Symptoms may include diarrhea, vomiting, numbness, ...

* Grayanotoxin

Grayanotoxins are a group of closely related neurotoxins named after ''Leucothoe grayana'', a plant native to Japan and named for 19th-century American botanist Asa Gray. Grayanotoxin I (grayanotoxane-3,5,6,10,14,16-hexol 14-acetate) is also known ...

(honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several species of bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of pl ...

intoxication)

* Hormones from the thyroid gland

The thyroid, or thyroid gland, is an endocrine gland in vertebrates. In humans, it is a butterfly-shaped gland located in the neck below the Adam's apple. It consists of two connected lobes. The lower two thirds of the lobes are connected by ...

s of slaughtered animals (especially triiodothyronine

Triiodothyronine, also known as T3, is a thyroid hormone. It affects almost every physiological process in the body, including growth and development, metabolism, body temperature, and heart rate.

Production of T3 and its prohormone thyroxi ...

in cases of ''hamburger thyrotoxicosis'' or ''alimentary thyrotoxicosis'')

* Mushroom toxins

* Phytohaemagglutinin

Phytohaemagglutinin (PHA, or phytohemagglutinin) is a lectin found in plants, especially certain legumes. PHA actually consists of two closely related proteins, called leucoagglutinin (PHA-L) and PHA-E. These proteins cause blood cells to clump ...

(red kidney bean

The kidney bean is a variety of the common bean (''Phaseolus vulgaris'') named for its resemblance to a human kidney.

Classification

There are different classifications of kidney beans, such as:

*Red kidney bean (also known as common kidney ...

poisoning; destroyed by boiling)

* Pyrrolizidine alkaloid

Pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs), sometimes referred to as necine bases, are a group of naturally occurring alkaloids based on the structure of pyrrolizidine. Their use dates back centuries and is intertwined with the discovery, understanding, and e ...

s

* Shellfish toxin, including paralytic shellfish poisoning

Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) is one of the four recognized syndromes of shellfish poisoning, which share some common features and are primarily associated with bivalve mollusks (such as mussels, clams, oysters and scallops). These shellfi ...

, diarrhetic shellfish poisoning, neurotoxic shellfish poisoning, amnesic shellfish poisoning

Amnesic shellfish poisoning (ASP) is an illness caused by consumption of shellfish that contain the marine biotoxin called domoic acid. In mammals, including humans, domoic acid acts as a neurotoxin

Neurotoxins are toxins that are destructive ...

and ciguatera

Ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP), also known as ciguatera, is a foodborne illness caused by eating tropical reef fish contaminated with ciguatoxins. Such individual fish are said to be ciguatoxic. Symptoms may include diarrhea, vomiting, numbness ...

fish poisoning

* Scombrotoxin

Scombroid food poisoning, also known as simply scombroid, is a foodborne illness that typically results from eating spoiled fish. Symptoms may include flushed skin, sweating, headache, itchiness, blurred vision, abdominal cramps and diarrhea. ...

* Solanine

Solanine is a glycoalkaloid poison found in species of the Solanaceae, nightshade family within the genus ''Solanum'', such as the potato (''Solanum tuberosum''). It can occur naturally in any part of the plant, including the Leaf, leaves, frui ...

(green potato

The potato () is a starchy tuberous vegetable native to the Americas that is consumed as a staple food in many parts of the world. Potatoes are underground stem tubers of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'', a perennial in the nightshade famil ...

poisoning)

* Tetrodotoxin

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is a potent neurotoxin. Its name derives from Tetraodontiformes, an Order (biology), order that includes Tetraodontidae, pufferfish, porcupinefish, ocean sunfish, and triggerfish; several of these species carry the toxin. Alt ...

( fugu fish poisoning)

* Tremetol (milk sickness

Milk sickness, also known as tremetol vomiting, is a kind of poisoning characterized by trembling, vomiting, and severe intestinal pain that affects individuals who ingest milk, other dairy products, or meat from a cow that has fed on white sna ...

stemming from a cow that ate white snakeroot)

Some plants contain substances which are toxic in large doses, but have therapeutic properties in appropriate dosages.

* Foxglove

''Digitalis'' ( or ) is a genus of about 20 species of herbaceous perennial plants, shrubs, and biennials, commonly called foxgloves.

''Digitalis'' is native to Europe, Western Asia, and northwestern Africa. The flowers are tubular in sha ...

contains cardiac glycosides

Cardiac glycosides are a class of organic compounds that increase the output force of the heart and decrease its rate of contractions by inhibiting the cellular sodium-potassium ATPase pump. Their beneficial medical uses include treatments for ...

.

* Poisonous hemlock (conium

''Conium'' ( or ) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Apiaceae. , Plants of the World Online accepts six species.

All species of the genus are poisonous to humans. ''C. maculatum'', also known as hemlock, is infamous for being highly ...

) has medicinal uses.

Other pathogenic agents

*Prion

A prion () is a Proteinopathy, misfolded protein that induces misfolding in normal variants of the same protein, leading to cellular death. Prions are responsible for prion diseases, known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSEs), w ...

s, resulting in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) is an incurable, always fatal neurodegenerative disease belonging to the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) group. Early symptoms include memory problems, behavioral changes, poor coordination, visu ...

(CJD) and its variant ( vCJD)

"Ptomaine poisoning" misconception

Ptomaine poisoning was a myth that persisted in the public consciousness, in newspaper headlines, and legal cases as an official diagnosis, decades after it had been scientifically disproven in the 1910s. In the 19th century, the Italian chemistFrancesco Selmi

Francesco Selmi (7 April 1817 – 13 August 1881) was an Italian chemist and patriot, one of the founders of colloid chemistry.

Selmi was born in Vignola, then part of the Duchy of Modena and Reggio. He became head of a chemistry laborator ...

, of Bologna, introduced the generic name ' (from Greek ''ptōma'', "fall, fallen body, corpse") for alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

s found in decaying animal and vegetable matter, especially (as reflected in their names) putrescine

Putrescine is an organic compound with the formula (CH2)4(NH2)2. It is a colorless solid that melts near room temperature. It is classified as a diamine. Together with cadaverine, it is largely responsible for the foul odor of Putrefaction, putref ...

and cadaverine

Cadaverine is an organic compound with the formula (CH2)5(NH2)2. Classified as a diamine, it is a colorless liquid with an unpleasant odor. It is present in small quantities in living organisms but is often associated with the putrefaction of Tiss ...

. The 1892 ''Merck's Bulletin'' stated, "We name such products of bacterial origin ptomaines; and the special alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

produced by the comma bacillus is variously named Cadaverine, Putrescine, etc." while ''The Lancet

''The Lancet'' is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal, founded in England in 1823. It is one of the world's highest-impact academic journals and also one of the oldest medical journals still in publication.

The journal publishes ...

'' stated, "The chemical ferments produced in the system, the... ptomaines which may exercise so disastrous an influence." It is now known that the "disastrous... influence" is due to the direct action of bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

and only slightly due to the alkaloids. Thus, the use of the phrase "ptomaine poisoning" is obsolete.

At a Communist Party political convention in Massillon, Ohio

Massillon is a city in western Stark County, Ohio, United States, along the Tuscarawas River. The population was 32,146 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Massillon is a principal city of the Canton–Massillon metropolitan area, whic ...

, and aboard a cruise ship in Washington, D.C., hundreds of people were sickened in separate incidents by tainted potato salad

Potato salad is a salad dish made from boiled potatoes, usually containing a dressing and a variety of other ingredients such as boiled eggs and raw vegetables. It is usually served as a side dish.

History and varieties

Potato salad is foun ...

, during a single week in 1932, drawing national attention to the dangers of so-called "ptomaine poisoning" in the pages of the American news weekly, ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

.'' In 1944, another newspaper article reported that over 150 people in Chicago were hospitalized with ptomaine poisoning, apparently from rice pudding

Rice pudding is a dish made from rice mixed with water or milk and commonly other ingredients such as sweeteners, spices, flavourings and sometimes eggs.

Variants are used for either desserts or dinners. When used as a dessert, it is commonly c ...

served by a restaurant chain.

Mechanism

Incubation period

The delay between the consumption of contaminated food and the appearance of the firstsymptom

Signs and symptoms are diagnostic indications of an illness, injury, or condition.

Signs are objective and externally observable; symptoms are a person's reported subjective experiences.

A sign for example may be a higher or lower temperature ...

s of illness is called the incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or ionizing radiation, radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infect ...

. This ranges from hours to days (and rarely months or even years, such as in the case of listeriosis

Listeriosis is a bacterial infection most commonly caused by '' Listeria monocytogenes'', although '' L. ivanovii'' and '' L. grayi'' have been reported in certain cases. Listeriosis can cause severe illness, including severe sepsis, me ...

or bovine spongiform encephalopathy

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly known as mad cow disease, is an incurable and always fatal neurodegenerative disease of cattle. Symptoms include abnormal behavior, trouble walking, and weight loss. Later in the course of th ...

), depending on the agent, and on how much was consumed. If symptoms occur within one to six hours after eating the food, it suggests that it is caused by a bacterial toxin or a chemical rather than live bacteria.

The long incubation period of many foodborne illnesses tends to cause those affected to attribute their symptoms to gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis, also known as infectious diarrhea, is an inflammation of the Human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract including the stomach and intestine. Symptoms may include diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Fever, lack of ...

.

During the incubation period, microbe

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic size, which may exist in its single-celled form or as a colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen microbial life was suspected from antiquity, with an early attestation in ...

s pass through the stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of Human, humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The Ancient Greek name for the stomach is ''gaster'' which is used as ''gastric'' in medical t ...

into the intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. T ...

, attach to the cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a d ...

lining the intestinal walls, and begin to multiply there. Some types of microbes stay in the intestine, some produce a toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. They occur especially as proteins, often conjugated. The term was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849–1919), derived ...

that is absorbed into the blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells.

Blood is com ...

stream, and some can directly invade the deeper body tissues. The symptoms produced depend on the type of microbe.

In cases of foodborne illness, particularly traveler's diarrhea, symptoms often result from the immune system's response rather than direct pathogen damage. This inflammatory response can lead to post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS), where 3-20% of affected individuals develop chronic gastrointestinal symptoms even after the pathogen is cleared. This suggests that the body's immune reaction, particularly inflammation, plays a significant role in both acute symptoms and long-term effects of foodborne illness.

Infectious dose