Polonophile on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A Polonophile is an individual who respects and is fond of

When Polish King Stephen Bathory captured

When Polish King Stephen Bathory captured  During the

During the

One of the strongest centres of Polonophilia in 19th-century Europe was

One of the strongest centres of Polonophilia in 19th-century Europe was  In the early 20th century, a number of writers declared their admiration for the Poles, including

In the early 20th century, a number of writers declared their admiration for the Poles, including

In 1939, Germany's allies, traditionally Poland-friendly Italy, Japan and Hungary, did not approve of the German

In 1939, Germany's allies, traditionally Poland-friendly Italy, Japan and Hungary, did not approve of the German  Several people who had contact with the Polish resistance praised the Poles. Ron Jeffery, British prisoner of war who escaped from German captivity in

Several people who had contact with the Polish resistance praised the Poles. Ron Jeffery, British prisoner of war who escaped from German captivity in

Many

Many

Hungary and Poland have enjoyed good relations since the inauguration of diplomatic relations between the two countries in the

Hungary and Poland have enjoyed good relations since the inauguration of diplomatic relations between the two countries in the

Italy and Poland shared common historical backgrounds and common enemies (Austria), and a good relationship is maintained to this day. Poles and Italians supported each other's independence struggles. The Poles fought in the

Italy and Poland shared common historical backgrounds and common enemies (Austria), and a good relationship is maintained to this day. Poles and Italians supported each other's independence struggles. The Poles fought in the

Strong support for Poland and pro-Polish sentiment were also observed by US President

Strong support for Poland and pro-Polish sentiment were also observed by US President

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

's culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

as well as Polish history

The history of Poland spans over a thousand years, from Lechites, medieval tribes, Christianization of Poland, Christianization and Kingdom of Poland, monarchy; through Polish Golden Age, Poland's Golden Age, Polonization, expansionism and be ...

, traditions and customs. The term defining this kind of attitude is Polonophilia. The antonym

In lexical semantics, opposites are words lying in an inherently incompatible binary relationship. For example, something that is ''even'' entails that it is not ''odd''. It is referred to as a 'binary' relationship because there are two members i ...

and opposite of Polonophilia is Polonophobia

Polonophobia, also referred to as anti-Polonism () or anti-Polish sentiment are terms for negative attitudes, prejudices, and actions against Polish people, Poles as an ethnic group, Poland as their country, and Polish culture, their culture. ...

.

History

Duchy and Kingdom of Poland

The history of the concept dates back to the beginning of the Polish state in 966 AD under DukeMieszko I

Mieszko I (; – 25 May 992) was Duchy of Poland (966–1025), Duke of Poland from 960 until his death in 992 and the founder of the first unified History of Poland, Polish state, the Civitas Schinesghe. A member of the Piast dynasty, he was t ...

. It remained strong among ethnic minorities as in allied neighbouring countries and during Polonization

Polonization or Polonisation ()In Polish historiography, particularly pre-WWII (e.g., L. Wasilewski. As noted in Смалянчук А. Ф. (Smalyanchuk 2001) Паміж краёвасцю і нацыянальнай ідэяй. Польскі ...

of the Eastern Borderlands

Eastern Borderlands (), often simply Borderlands (, ) was a historical region of the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic. The term was coined during the interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural and extensively multi-ethnic with ...

, Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

and other acquired territories implied by the Polish Crown

The Crown of the Kingdom of Poland (; ) was a political and legal concept formed in the 14th century in the Kingdom of Poland, assuming unity, indivisibility and continuity of the state. Under this idea, the state was no longer seen as the pa ...

or the Polish government, thus also triggering Polonophobia.

One of the first recorded potential Polonophiles were exiled Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, who settled in Poland throughout the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, particularly following the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

(1096-1099). The culture and the intellectual output of the Jewish community in Poland had a profound impact on Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

as a whole over the next centuries, with both cultures becoming somewhat interconnected and being influenced by each other. Jewish historians claimed that the name of the country is pronounced as "Polania" or "Polin" in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

, which was interpreted as a good omen because Polania can be divided into three separate Hebrew words: ''po'' (here), ''lan'' (dwells), ''ya'' (God) and Polin into two words: ''po'' (here) ''lin'' (ou should

OU or Ou or ou may stand for:

Universities United States

* Oakland University in Oakland County, Michigan

* Oakwood University in Huntsville, Alabama

* Oglethorpe University in Atlanta, Georgia

* Ohio University in Athens, Ohio

* Olivet Univers ...

dwell). That suggested that Poland was a good destination for the Jews fleeing from persecution and anti-Semitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

in other European countries. Rabbi David HaLevi Segal

David ha-Levi Segal (c. 1586 – 20 February 1667), also known as the Turei Zahav (abbreviated Taz []) after the title of his significant ''halakha, halakhic'' commentary on the ''Shulchan Aruch'', was one of the greatest Jews of Poland, Polish ...

(Taz) expressed his pro-Polish views by stating in Poland, "most of the time the Gentiles do no harm; on the contrary they do right by Israel" (Divre David; 1689). Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim) form a distinct subgroup of the Jewish diaspora, that emerged in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium CE. They traditionally speak Yiddish, a language ...

willingly adopted some aspects of Polish cuisine

Polish cuisine ( ) is a style of food preparation originating in and widely popular in Poland. Due to History of Poland, Poland's history, Polish cuisine has evolved over the centuries to be very eclectic, and shares many similarities with other ...

, language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

and national dress

Folk costume, traditional dress, traditional attire or folk attire, is clothing of an ethnic group, nation or region, and expresses cultural, religious or national identity. An ethnic group's clothing may also be called ethnic clothing or ethnic ...

, which can be seen in Orthodox Jewish

Orthodox Judaism is a collective term for the traditionalist branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as literally revealed by God on Mount Sinai and faithfully tra ...

communities around the world.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

(Truce of Jam Zapolski

The Truce or Treaty of Yam-Zapolsky (Ям-Запольский) or Jam Zapolski, signed on 15 January 1582 between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia, was one of the treaties that ended the Livonian War. It followed t ...

), he granted the city of Tartu

Tartu is the second largest city in Estonia after Tallinn. Tartu has a population of 97,759 (as of 2024). It is southeast of Tallinn and 245 kilometres (152 miles) northeast of Riga, Latvia. Tartu lies on the Emajõgi river, which connects the ...

(Polish: ''Dorpat''), now in Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

, its own banner with the colours and layout resembling the Polish flag

The national flag of Poland ( ) consists of two horizontal stripes of equal width, the upper one white and the lower one red. The two colours are defined in the Polish constitution as the national colours. A variant of the flag with the nation ...

. The flag dates from 1584 and is still in use.

When the Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

invaded the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia, also known as the Tsardom of Moscow, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of tsar by Ivan the Terrible, Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter the Great in 1721.

...

in 1605, a self-identified prince, known as False Dmitry I

False Dmitry I or Pseudo-Demetrius I () reigned as the Tsar of all Russia from 10 June 1605 until his death on 17 May 1606 under the name of Dmitriy Ivanovich (). According to historian Chester S.L. Dunning, Dmitry was "the only Tsar ever raise ...

, assumed the Russian throne. A Polonophile, he assured that King Sigismund III of Poland

Sigismund III Vasa (, ; 20 June 1566 – 30 April 1632

N.S.) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1587 to 1632 and, as Sigismund, King of Sweden from 1592 to 1599. He was the first Polish sovereign from the House of Vasa. Relig ...

could control the country's internal and external affairs, secure Russia's conversion to Catholicism and thus make it a puppet state. Dmitry's murder was a possible justification for arranging a full-scale invasion by Sigismund in 1609. The Seven Boyars

The Seven Boyars () were a group of Russian nobles who deposed Tsar Vasili Shuisky on and later that year, after Russia lost the Battle of Klushino during the Polish–Russian War, acquiesced to the Polish–Lithuanian occupation of Moscow.

The ...

deposed reigning Tsar Boris Godunov

Boris Feodorovich Godunov (; ; ) was the ''de facto'' regent of Russia from 1585 to 1598 and then tsar from 1598 to 1605 following the death of Feodor I, the last of the Rurik dynasty. After the end of Feodor's reign, Russia descended into t ...

to demonstrate their support for the Polish cause. Godunov was transported as a prisoner to Poland, where he died. In 1610, the Boyars elected Sigismund's underage son Władysław as the new Tsar of Russia, but he was never crowned. This period was known as the Time of Troubles

The Time of Troubles (), also known as Smuta (), was a period of political crisis in Tsardom of Russia, Russia which began in 1598 with the death of Feodor I of Russia, Feodor I, the last of the Rurikids, House of Rurik, and ended in 1613 wit ...

, a major part in Russian history that remains relatively unmentioned in Polish historiography because of its implied Polonization policies.

During the

During the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, the Zaporizhian Cossack state was allied to the Catholic King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of Royal elections in Poland, free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electab ...

, and the Cossacks were often hired as mercenaries

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an War, armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rath ...

. That had a strong impact on the Ukrainian language

Ukrainian (, ) is an East Slavic languages, East Slavic language, spoken primarily in Ukraine. It is the first language, first (native) language of a large majority of Ukrainians.

Written Ukrainian uses the Ukrainian alphabet, a variant of t ...

and led to the establishment of a functioning Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC) is a Major archiepiscopal church, major archiepiscopal ''sui iuris'' ("autonomous") Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic church that is based in Ukraine. As a particular church of the Cathol ...

in 1596 at the Union of Brest

The Union of Brest took place in 1595–1596 and represented an agreement by Eastern Orthodox Churches in the Ruthenian portions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to accept the Pope's authority while maintaining Eastern Orthodox liturgical ...

. The Ukrainians, however, retained their Orthodox Christian faith and Cyrillic alphabet

The Cyrillic script ( ) is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic, Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Caucasian and Iranic-speaking countries in Southeastern Europe, Easte ...

. During the Russo-Polish War of 1654–1667, the Cossacks were divided into the pro-Polish (Right-bank Ukraine

The Right-bank Ukraine is a historical and territorial name for a part of modern Ukraine on the right (west) bank of the Dnieper River, corresponding to the modern-day oblasts of Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Kirovohrad, as well as the western parts o ...

) and pro-Russian (Left-bank Ukraine

The Left-bank Ukraine is a historic name of the part of Ukraine on the left (east) bank of the Dnieper River, comprising the modern-day oblasts of Chernihiv, Poltava and Sumy as well as the eastern parts of Kyiv and Cherkasy.

Left-bank Ukrain ...

) factions. Petro Doroshenko

Petro Dorofiiovich Doroshenko (; 1627–1698) was a Cossack political and military leader, Hetman of right-bank Ukraine (1665–1672) and a Russian voivode.

Background and early career

Petro Doroshenko was born in Chyhyryn into a noble ...

, who commanded the army of Right-bank Ukraine, and Pavlo Teteria and Ivan Vyhovsky

Ivan Vyhovsky (; ; date of birth unknown, died 1664), a Ukrainian military and political figure and statesman, served as hetman of the Zaporizhian Host and of the Cossack Hetmanate for three years (1657–1659) during the Russo-Polish War (1654 ...

were open Polonophiles and allied to the Polish king. The Polish influence on Ukraine ended with the partitions of the late 18th century, when the territory of contemporary Ukraine was annexed by the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

.

Under John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( (); (); () 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobieski was educated at the Jagiellonian University and toured Eur ...

, the Christian coalition forces defeated the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks () were a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group in Anatolia. Originally from Central Asia, they migrated to Anatolia in the 13th century and founded the Ottoman Empire, in which they remained socio-politically dominant for the e ...

at the Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mountain near Vienna on 1683 after the city had been besieged by the Ottoman Empire for two months. The battle was fought by the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarchy) and the Polish–Li ...

in 1683, which ironically sparked admiration for Poland and its Winged Hussars

The Polish hussars (; ), alternatively known as the winged hussars, were an elite heavy cavalry formation active in Poland and in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1503 to 1702. Their epithet is derived from large rear wings, which were ...

in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. The Sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

named Sobieski the "Lion of Lehistan

The ethnonyms for the Polish people, Poles (people) and Poland (their country) include Exonym and endonym, endonyms (the way Polish people refer to themselves and their country) and exonyms (the way other peoples refer to the Poles and their c ...

oland. It also sparked admiration in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, with the Persians granting Sobieski the proud title of '' Ghazi''. That tradition was cultivated when Poland disappeared from map for 123 years. The Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, along with Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, was the only major country in the world not to recognise the Partitions of Poland. The reception ceremony of a foreign ambassador or a diplomatic mission in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

began with an announcement sacred formula: "the Ambassador of Lehistan olandhas not yet arrived".

After Partitions

ThePartitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partition (politics), partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place between 1772 and 1795, toward the end of the 18th century. They ended the existence of the state, resulting in the eli ...

gave a rise to a new wave of Polonophilia in Europe and the world. Exiled revolutionaries such as Casimir Pulaski

Kazimierz Michał Władysław Wiktor Pułaski (; March 4 or 6, 1745 October 11, 1779), anglicised as Casimir Pulaski ( ), was a Polish nobleman, soldier, and military commander who has been called "The Father of American cavalry" or "The So ...

and Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko (; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish Military engineering, military engineer, statesman, and military leader who then became a national hero in Poland, the United States, Lithuania, and ...

, who fought for the independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

from Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, contributed to the sentiment that is relatively pro-Polish in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

.

In Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

, the leader of the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution ( or ; ) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolution was the only known Slave rebellion, slave up ...

and first head of state Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Haitian Creole: ''Jan-Jak Desalin''; ; 20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was the first Haitian Emperor, leader of the Haitian Revolution, and the first ruler of an independent First Empire of Haiti, Haiti under th ...

, called the Poles the ''white Negroes of Europe''. This was an expression of respect and empathy for the situation of the Poles, after Polish soldiers sent by Napoleon to suppress the Haitian Revolution defected to join the insurgents (see '' Haiti–Poland relations''). The 1805 Haitian constitution granted the Poles Haitian citizenship.

Newly established Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, which declared independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

from the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, was a very Polonophile country (see '' Belgium–Poland relations''). Belgian diplomacy refused to establish diplomatic relations with the Russian Empire for annexing a large portion of Poland's eastern territories during the Partitions. Diplomatic relations between Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

and Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

were established only decades later.

The November Uprising

The November Uprising (1830–31) (), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in Russian Partition, the heartland of Partitions of Poland, partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. ...

in Congress Poland in 1830 against Russia prompted a wave of Polonophilia in Germany (excluding the partitioning state of Prussia), including financial contributions to exiles, the singing of pro-Polish songs, and pro-Polish literature. During the January uprising

The January Uprising was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at putting an end to Russian occupation of part of Poland and regaining independence. It began on 22 January 1863 and continued until the last i ...

in 1863, however, the pro-Polish sentiment had mostly vanished.

One of the strongest centres of Polonophilia in 19th-century Europe was

One of the strongest centres of Polonophilia in 19th-century Europe was Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

. The Young Ireland

Young Ireland (, ) was a political movement, political and cultural movement, cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly ''The Nation (Irish news ...

movement and the Fenian

The word ''Fenian'' () served as an umbrella term for the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and their affiliate in the United States, the Fenian Brotherhood. They were secret political organisations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries ...

s saw similarities in both countries as "Catholic nations and victims of larger imperial powers". In 1863, Irish newspapers expressed wide support for the January uprising

The January Uprising was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at putting an end to Russian occupation of part of Poland and regaining independence. It began on 22 January 1863 and continued until the last i ...

, which was then seen as a risky move.

Italians and Hungarians supported the Poles in the January Uprising

The January Uprising was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at putting an end to Russian occupation of part of Poland and regaining independence. It began on 22 January 1863 and continued until the last i ...

most numerously (see ''Hungary'' and ''Italy'' sections below), but other nations also showed sympathy for the uprising. In Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

, various newspapers sympathized with the Poles, with some stating that Russia was a common enemy of Sweden and Poland, pro-Polish rallies were held, attended by Swedish parliamentarians, and funds were collected for arms for the Polish insurgents. Swedish King Charles XV

Charles XV or Carl (''Carl Ludvig Eugen''; Swedish language, Swedish and Norwegian language, Norwegian officially: ''Karl''; 3 May 1826 – 18 September 1872) was King of Sweden and List of Norwegian monarchs, Norway, there often referred to as C ...

strongly supported Swedish involvement in the fight on the Polish side, which, however, did not take place due to the restrained stance of the Swedish government, which declared willingness to fight for Poland only alongside Western European powers of Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. An expedition of armed Polish volunteers from Western Europe assisted by foreigners of various nationalities, which stopped on the island of Öland

Öland (, ; ; sometimes written ''Oland'' internationally) is the second-largest Swedish island and the smallest of the traditional provinces of Sweden. Öland has an area of and is located in the Baltic Sea just off the coast of Småland. ...

and in Malmö

Malmö is the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, third-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg, and the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, sixth-largest city in Nordic countries, the Nordic region. Located on ...

on its way to Poland, was met with sympathy of the local Swedes.

Throughout modern history, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

was long Poland's ally, especially after French King Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

married Polish Princess Marie Leszczyńska

Maria Karolina Zofia Felicja Leszczyńska (; 23 June 1703 – 24 June 1768), also known as Marie Leczinska (), was Queen of France as the wife of King Louis XV from their marriage on 4 September 1725 until her death in 1768. The daughter of St ...

, the daughter of Stanislaus I. Polish customs and fashion became popular in the Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

such as the Polonaise dress (''robe à la polonaise''), which was adored by Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

. Polish cuisine

Polish cuisine ( ) is a style of food preparation originating in and widely popular in Poland. Due to History of Poland, Poland's history, Polish cuisine has evolved over the centuries to be very eclectic, and shares many similarities with other ...

also became known in French as ''à la polonaise''. Both Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

and Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

expressed strong pro-Polish sentiment after Poland had ceased to exist as a sovereign country in 1795. In 1807, Napoleon I established the Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw (; ; ), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a First French Empire, French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during the Napoleonic Wars. It initially comprised the ethnical ...

, a client state of the French Empire that was dissolved in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

. Napoleon III also called for a free Poland and his wife, Eugénie de Montijo

Eugénie de Montijo (; born María Eugenia Ignacia Agustina de Palafox y Kirkpatrick; 5 May 1826 – 11 July 1920) was Second French Empire, Empress of the French from her marriage to Napoleon III on 30 January 1853 until he was overthrown on 4 ...

, astonished the Austrian ambassador (Austria was one of three partitioning powers) by "unveiling a European map with a realignment of borders to accommodate independent Poland".

The closely related Sorbs

Sorbs (; ; ; ; ; also known as Lusatians, Lusatian Serbs and Wends) are a West Slavs, West Slavic ethnic group predominantly inhabiting the parts of Lusatia located in the German states of Germany, states of Saxony and Brandenburg. Sorbs tradi ...

, who were also under Polish rule in the Middle Ages, sympathised with the Poles and viewed them as allies in the resistance against Germanisation policies. 19th-century Sorbian activist declared his sympathy and admiration for the Poles, popularised knowledge of Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

and Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko (; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish Military engineering, military engineer, statesman, and military leader who then became a national hero in Poland, the United States, Lithuania, and ...

through Sorbian press, reported on the events of the January Uprising and made contacts with Poles during visits to Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

, Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

and Poznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

.

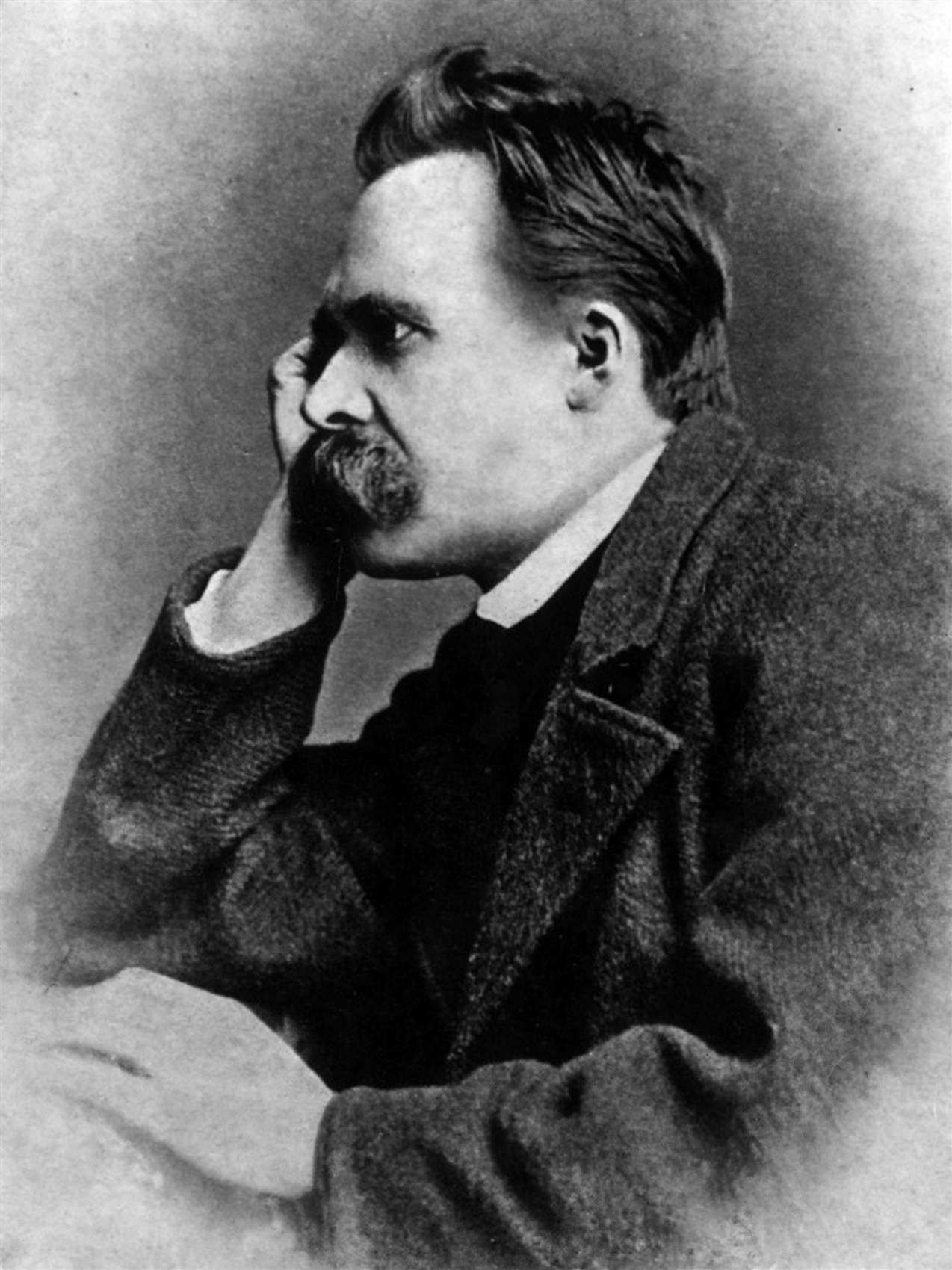

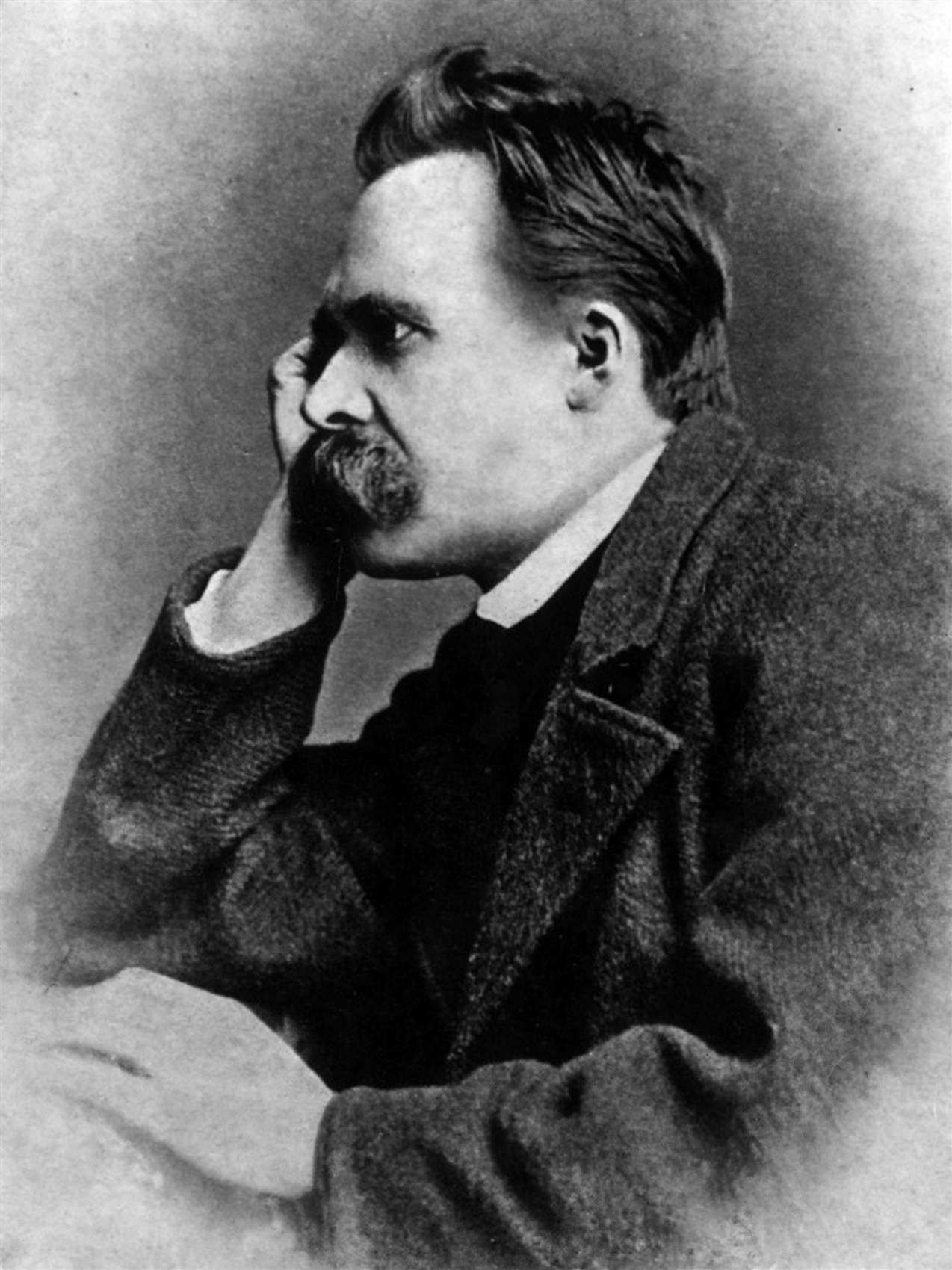

One of the most prominent and self-declared Polonophiles of the late 19th century was the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

, who was certain of his Polish heritage. He often expressed his positive views and admiration towards Poles and their culture. However, modern scholars believe that Nietzsche's claim of Polish ancestry was a pure invention. According to biographer R. J. Hollingdale, Nietzsche's propagation of the Polish ancestry myth may have been part of his "campaign against Germany".

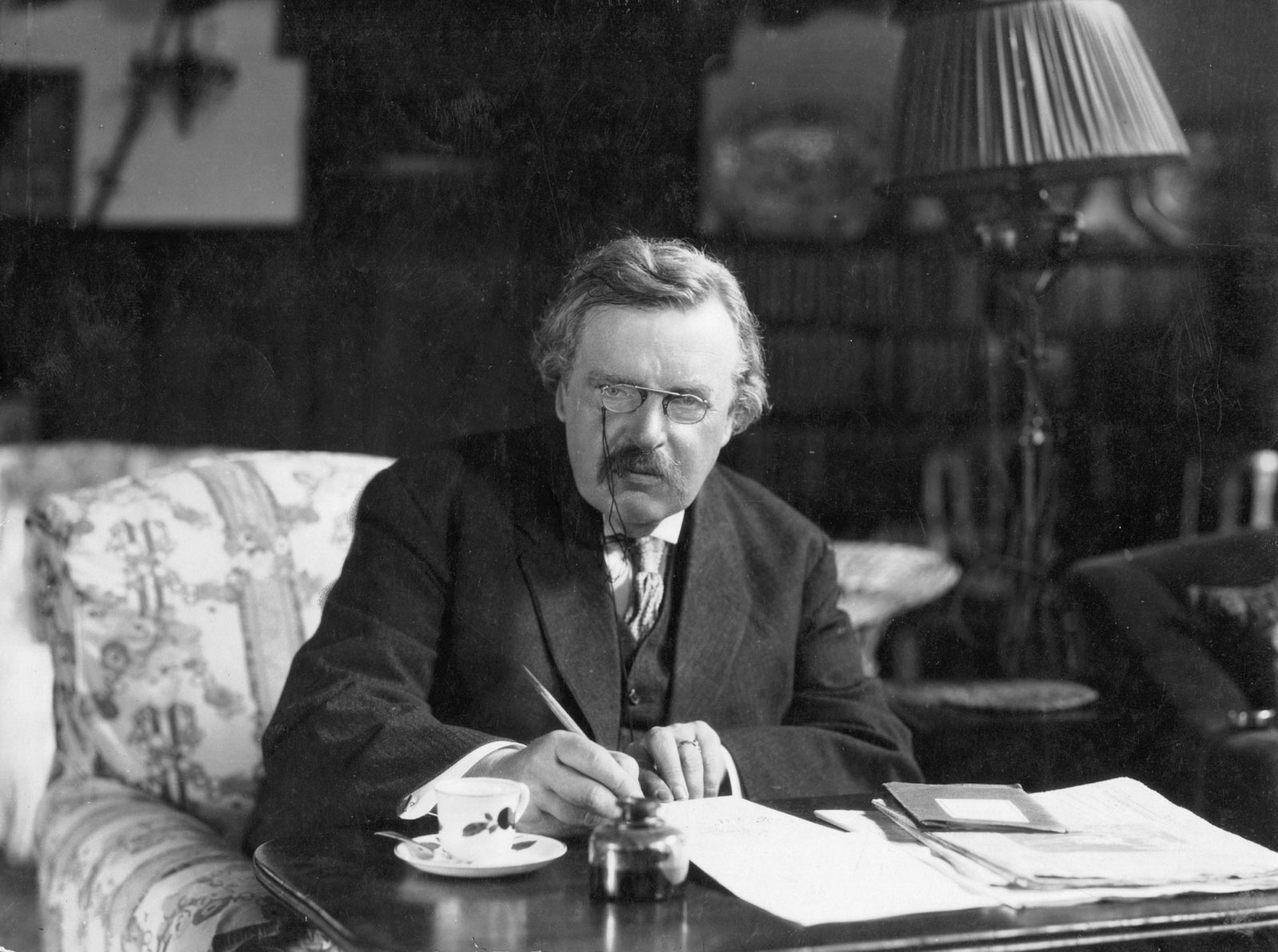

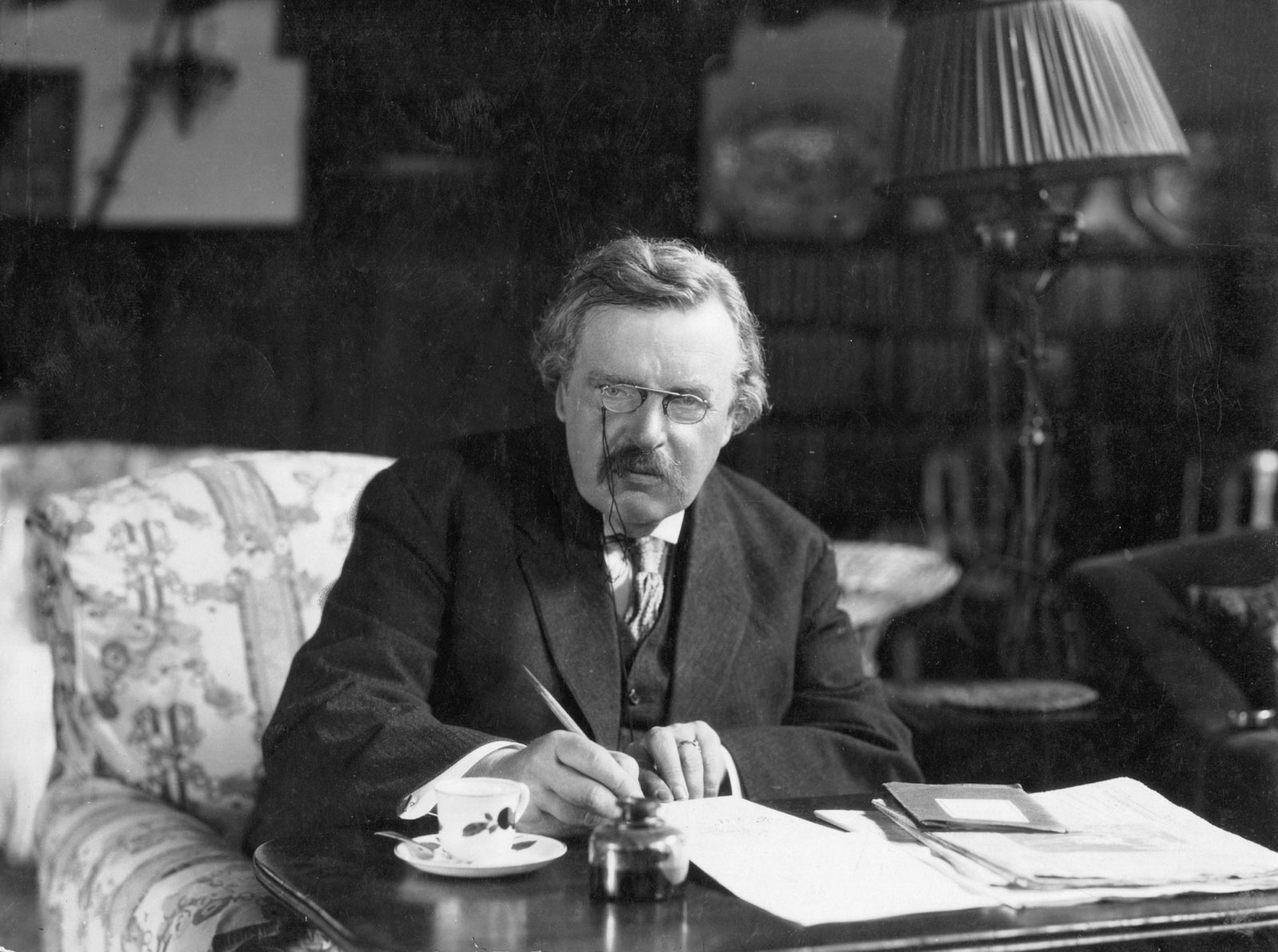

In the early 20th century, a number of writers declared their admiration for the Poles, including

In the early 20th century, a number of writers declared their admiration for the Poles, including Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

's Ruy Barbosa

Ruy Barbosa de Oliveira (5 November 1849 – 1 March 1923), also known as Rui Barbosa, was a Brazilian politician, writer, jurist, and diplomat.

He was a prominent defender of civil liberties who called for the abolition of slavery in Brazi ...

, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

's Nitobe Inazō

was a Japanese agronomist, diplomat, political scientist, politician, and writer. He studied at Sapporo Agricultural College under the influence of its first president William S. Clark and later went to the United States to study agricultural ...

and Britain's G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English author, philosopher, Christian apologist, journalist and magazine editor, and literary and art critic.

Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brow ...

. Nitobe Inazō called Poles a ''brave and chivalrous nation,'' and valued Polish devotion to history and patriotism. Ruy Barbosa advocated for Polish independence at the Hague Conventions of 1907.

A display of sympathy and gratitude towards Poland in Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

was the unveiling of a memorial complex and symbolic mausoleum of King Władysław III of Poland

Władysław III of Poland (31 October 1424 – 10 November 1444), also known as Ladislaus of Varna, was King of Poland and Union of Horodło, Supreme Duke of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from 1434 as well as King of Hungary and List of duk ...

in Varna

Varna may refer to:

Places Europe

*Varna, Bulgaria, a city

** Varna Province

** Varna Municipality

** Gulf of Varna

** Lake Varna

**Varna Necropolis

* Vahrn, or Varna, a municipality in Italy

* Varna (Šabac), a village in Serbia

Asia

* Var ...

. Władysław III commanded a coalition of Central and Eastern European countries at the Battle of Varna

The Battle of Varna took place on 10 November 1444 near Varna in what is today eastern Bulgaria. The Ottoman army under Sultan Murad II (who did not actually rule the sultanate at the time) defeated the Crusaders commanded by King Władysła ...

in 1444 in an attempt to repel the Ottoman invasion of Europe and liberate Bulgaria. Also, football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kick (football), kicking a football (ball), ball to score a goal (sports), goal. Unqualified, football (word), the word ''football'' generally means the form of football t ...

club SK Vladislav Varna, the first ever Bulgarian football champion, was named after the Polish king.

Following the restoration of Polish independence

When Poland finally regained its independence followingWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Polonophilia gradually transformed into a demonstration of patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and a sense of attachment to one's country or state. This attachment can be a combination of different feelings for things such as the language of one's homeland, and its ethnic, cultural, politic ...

and solidarity, especially during the horrors of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and the Polish struggle against communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

.

In 1939, Germany's allies, traditionally Poland-friendly Italy, Japan and Hungary, did not approve of the German

In 1939, Germany's allies, traditionally Poland-friendly Italy, Japan and Hungary, did not approve of the German invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

, which started World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Despite declared neutrality and German and Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

pressure, Hungary, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, Italy, Bulgaria, Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

and Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

sympathized with Poland and secretly allowed the escape of Poles through their territories to Polish-allied France, where the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the Army, land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 110,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military histor ...

was reconstituted to continue the fight against Germany. Eventually, Greece and Yugoslavia, fearing Germany, became reluctant to further allow Poles to escape through their territories, however Bulgaria and Turkey allowed the escape through their lands to continue. The Japanese helped secretly evacuate a portion of the Polish gold reserve

A gold reserve is the gold held by a national central bank, intended mainly as a guarantee to redeem promises to pay depositors, note holders (e.g. paper money), or trading peers, during the eras of the gold standard, and also as a store of v ...

from occupied Poland and closely co-operated with Polish intelligence. Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

declared appreciation for the Polish resistance against the German invasion.

Polish troops took part in the liberation of a number of nations from German occupation

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the government of Nazi Germany at ...

, which is, for example, particularly strongly remembered in Breda

Breda ( , , , ) is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the southern part of the Netherlands, located in the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of North Brabant. ...

in the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

. There is a Polish military cemetery, where Polish general and war hero Stanisław Maczek

Lieutenant General Stanisław Władysław Maczek (; 31 March 1892 – 11 December 1994) was a Polish tank commander of World War II, whose division was instrumental in the Allied liberation of France, closing the Falaise pocket, resulting in the ...

is buried, and the anniversary of the liberation is commemorated in the city, also by supporters of the local football club NAC Breda

NAC Breda (), often simply known as NAC, is a Dutch professional football club, based in Breda, Netherlands. NAC Breda play in the Rat Verlegh Stadium, named after their most important player, Antoon 'Rat' Verlegh. They play in the Eredivisi ...

(see '' Netherlands–Poland relations'').

Several people who had contact with the Polish resistance praised the Poles. Ron Jeffery, British prisoner of war who escaped from German captivity in

Several people who had contact with the Polish resistance praised the Poles. Ron Jeffery, British prisoner of war who escaped from German captivity in occupied Poland

' (Norwegian language, Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV 2 (Norway), TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. ...

and joined the Polish resistance, stated in his memoirs that ''People of more matchless moral and physical courage than the Poles have never existed, and a sense of pride at having fought and been closely associated with them in their scarce unbroken struggles, is always with me.'' Australian Walter Edward Smith, who similarly escaped from German captivity and joined the Polish resistance, declared that Poles, not Australians as he ''previously believed'', were ''the best soldiers in the world.''

Despite Soviet rule, Polish cemeteries and graves from World War II in Uzbekistan

, image_flag = Flag of Uzbekistan.svg

, image_coat = Emblem of Uzbekistan.svg

, symbol_type = Emblem of Uzbekistan, Emblem

, national_anthem = "State Anthem of Uzbekistan, State Anthem of the Republ ...

have mostly survived the post-war period. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

and restoration of independent Uzbekistan, Uzbeks often annotated Polish cemeteries with inscriptions referring to buried Poles as their ''friends'' (see '' Poland–Uzbekistan relations'').

In Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

, 8 June is celebrated as the "Day of the Polish Settler" to honour the contribution of Polish immigrants to Argentina.

Nations with strong pro-Polish sentiments

Armenia

Armenians in Poland

Armenians in Poland (; ) are one of nine legally recognized national minorities in Poland, their historical presence is going back to the Middle Ages. According to the Polish census of 2021 there are 6,772 ethnic Armenians in Poland. They are s ...

have an important and historical presence which dates back to the 14th century, however, the first Armenian settlers arrived in the 12th century, which makes them the oldest minority in Poland with the Jews. A very significant and independent Armenian diaspora

The Armenian diaspora refers to the communities of Armenians outside Armenia and other locations where Armenians are considered an indigenous population. Since antiquity, Armenians have established communities in many regions throughout the world. ...

existed in Poland but was assimilated over the centuries because of Polonization

Polonization or Polonisation ()In Polish historiography, particularly pre-WWII (e.g., L. Wasilewski. As noted in Смалянчук А. Ф. (Smalyanchuk 2001) Паміж краёвасцю і нацыянальнай ідэяй. Польскі ...

and the absorption of Polish culture

The culture of Poland () is the product of its Geography of Poland, geography and distinct historical evolution, which is closely connected to History of Poland, an intricate thousand-year history. Poland has a Catholic Church, Roman Catholic ma ...

. Between 40,000 and 80,000 people in Poland today claim Armenian nationality or Armenian heritage. Mass waves of Armenian immigration to Poland has occurred since the collapse of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in 1991.

Armenians are highly fond of Polish culture and history. Several Armenian cultural features also exist in the Polish national dress, most notably the Karabela

A karabela was a type of Polish sabre () popular in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Polish fencer Wojciech Zabłocki defines a karabela as a decorated sabre with the handle stylized as the head of a bird and an open crossguard.

Etymol ...

sabre introduced by Armenian merchants under Poland-Lithuania.

There are khachkar

A ''khachkar'' (also spelled as ''khatchkar'') or Armenian cross-stone (, , խաչ ''xačʿ'' "cross" + քար ''kʿar'' "stone") is a carved, memorial stele bearing a cross, and often with additional motifs such as rosette (design), rosettes ...

s commemorating Armenian-Polish friendship in Zamość

Zamość (; ; ) is a historical city in southeastern Poland. It is situated in the southern part of Lublin Voivodeship, about from Lublin, from Warsaw. In 2021, the population of Zamość was 62,021.

Zamość was founded in 1580 by Jan Zamoyski ...

, Szczecinek

Szczecinek (; ) is a historic city in Middle Pomerania, northwestern Poland, capital of Szczecinek County in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, with a population of more than 40,000 (2011). The town's total area is .

The turbulent history of Szcze ...

and Zabrze

Zabrze (; German: 1915–1945: , full form: , , ) is an industrial city put under direct government rule in Silesia in southern Poland, near Katowice. It lies in the western part of the Metropolis GZM, a metropolis with a population of around 2 m ...

in Poland, and Yerevan

Yerevan ( , , ; ; sometimes spelled Erevan) is the capital and largest city of Armenia, as well as one of the world's List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities. Situated along the Hrazdan River, Yerev ...

in Armenia.

Georgia

Many

Many Georgians

Georgians, or Kartvelians (; ka, ქართველები, tr, ), are a nation and Peoples of the Caucasus, Caucasian ethnic group native to present-day Georgia (country), Georgia and surrounding areas historically associated with the Ge ...

participated in military campaigns that were led by Poland in the 17th century. Bogdan Gurdziecki, an ethnic Georgian, became the Polish king's ambassador to the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

and made frequent diplomatic trips to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

to represent Polish interests. As both nations shared a similar fate, with Poland partitioned by Russia, Prussia and Austria in the late 18th century, and Georgia annexed by Russia in the 19th century, the two nations had more frequent encounters, particularly as a result of Russian deportations of Poles to Georgia and Georgians to Poland. Both nations supported each other's independence movements, and young Georgians came to study in Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

as they considered Poles an inspiration and model for their national liberation activity.

Following the Red Army invasion of Georgia

The Red Army invasion of Georgia (12 February17 March 1921), also known as the Georgian–Soviet War or the Soviet invasion of Georgia,Debo, R. (1992). ''Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918-1921'', pp. 182, 361� ...

, many Georgian military officers found refuge in Poland and joined the Polish Army. They later fought in Polish defense during the joint German-Soviet invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

at the start of World War II and afterwards many joined the Polish resistance movement.

During the Russo-Georgian War

The August 2008 Russo-Georgian War, also known as the Russian invasion of Georgia,Occasionally, the war is also referred to by other names, such as the Five-Day War and August War. was a war waged against Georgia by the Russian Federation and the ...

of 2008, Poland strongly supported Georgia. Polish President Lech Kaczyński

Lech Aleksander Kaczyński (; 18 June 194910 April 2010) was a Polish politician who served as the city mayor of Warsaw from 2002 until 2005, and as President of Poland from 2005 until his death in 2010 in an air crash. The aircraft carrying ...

flew to Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი, ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), ( ka, ტფილისი, tr ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia ( ...

to rally against the Russian military intervention and the subsequent military conflict. Several European leaders met with Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili

Mikheil "Misha" Saakashvili (born 21 December 1967) is a Georgian and Ukrainian politician and jurist. He was the third president of Georgia for two consecutive terms from 25 January 2004 to 17 November 2013. He is the founder and former chair ...

at Kaczyński's initiative at the rally held on 12 August 2008, which was attended by over 150,000 people. The crowd responded enthusiastically to the Polish president's speech and chanted, "Poland, Poland", "Friendship, Friendship" and "Georgia, Georgia".

The main boulevard in the city of Batumi

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ), historically Batum or Batoum, is the List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), second-largest city of Georgia (country), Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast ...

, Georgia, is named after Lech Kaczyński and his wife, Maria

Maria may refer to:

People

* Mary, mother of Jesus

* Maria (given name), a popular given name in many languages

Place names Extraterrestrial

* 170 Maria, a Main belt S-type asteroid discovered in 1877

* Lunar maria (plural of ''mare''), large, ...

.

Hungary

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. Hungary and Poland have maintained a very close friendship and brotherhood "rooted in a deep history of shared monarchs, cultures, and common faith". Both countries commemorate a fraternal relationship and Friendship Day.

Poles and Hungarians have repeatedly supported each other's national liberation uprisings, including the Polish November Uprising

The November Uprising (1830–31) (), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in Russian Partition, the heartland of Partitions of Poland, partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. ...

, January Uprising

The January Uprising was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at putting an end to Russian occupation of part of Poland and regaining independence. It began on 22 January 1863 and continued until the last i ...

and Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising (; ), sometimes referred to as the August Uprising (), or the Battle of Warsaw, was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from ...

and Hungarian Rákóczi's War of Independence

Rákóczi's War of Independence (1703–1711) was the first significant attempt to topple the rule of the Habsburgs over Royal Hungary, Hungary. The war was conducted by a group of noblemen, wealthy and high-ranking progressives and was led by F ...

, Revolution of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

and Revolution of 1956. After the fall of the Rákóczi's War of Independence, Poland took in fugitive Hungarian insurgents, including its leader Francis II Rákóczi

Francis II Rákóczi (, ; 27 March 1676 – 8 April 1735) was a Hungarian nobleman and leader of the Rákóczi's War of Independence against the Habsburgs in 1703–1711 as the prince () of the Estates Confederated for Liberty of the Kingdom of ...

, and following the fall of the January Uprising, Hungary received Polish refugees. Polish general Józef Bem

Józef Zachariasz Bem (, ; 14 March 1794 – 10 December 1850) was a Polish engineer and general, an Ottoman pasha and a national hero of Poland and Hungary, and a figure intertwined with other European patriotic movements. Like Tadeusz Kościus ...

is considered a national hero in Hungary, and is commemorated with several monuments.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Hungary refused to allow Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's troops to pass through the country during the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

in September 1939. Although Hungary, which was ruled by Miklós Horthy

Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya (18 June 1868 – 9 February 1957) was a Hungarian admiral and statesman who was the Regent of Hungary, regent of the Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1946), Kingdom of Hungary Hungary between the World Wars, during the ...

, was allied with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, it declined to participate in the invasion as a matter of "Hungarian honour".

On 12 March 2007, the Hungarian Parliament

The National Assembly ( ) is the parliament of Hungary. The unicameral body consists of 199 (386 between 1990 and 2014) members elected to four-year terms. Election of members is done using a semi-proportional representation: a mixed-member ...

declared 23 March as the "Day of Hungarian-Polish Friendship", with 324 votes in favor, none opposed, and no abstentions. Four days later, the Polish Parliament

The parliament of Poland is the Bicameralism, bicameral legislature of Poland. It is composed of an upper house (the Senate of Poland, Senate) and a lower house (the Sejm). Both houses are accommodated in the Sejm and Senate Complex of Poland, S ...

declared 23 March as the "Day of Polish-Hungarian Friendship" by acclamation. The Hungarian Parliament also voted 2016 as the Year of Hungarian-Polish solidarity.

The Hungarian-born Prince Stephen Báthory

Stephen Báthory (; ; ; 27 September 1533 – 12 December 1586) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (1576–1586) as well as Prince of Transylvania, earlier Voivode of Transylvania (1571–1576).

The son of Stephen VIII Báthory ...

was elected King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of Royal elections in Poland, free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electab ...

in 1576 and is the primary figure of the close ties between the countries.

Italy

Italy and Poland shared common historical backgrounds and common enemies (Austria), and a good relationship is maintained to this day. Poles and Italians supported each other's independence struggles. The Poles fought in the

Italy and Poland shared common historical backgrounds and common enemies (Austria), and a good relationship is maintained to this day. Poles and Italians supported each other's independence struggles. The Poles fought in the First Italian War of Independence

The First Italian War of Independence (), part of the ''Risorgimento'' or unification of Italy, was fought by the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont) and Italian volunteers against the Austrian Empire and other conse ...

and the Expedition of the Thousand

The Expedition of the Thousand () was an event of the unification of Italy that took place in 1860. A corps of volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi sailed from Quarto al Mare near Genoa and landed in Marsala, Sicily, in order to conquer the Ki ...

, contributing to the birth of a unified Italy. The Italian government subsequently agreed to establish a Polish Military School in Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, which trained Polish officers in exile, who then fought in the Polish January Uprising

The January Uprising was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at putting an end to Russian occupation of part of Poland and regaining independence. It began on 22 January 1863 and continued until the last i ...

against Russia. Italian volunteers formed the Garibaldi Legion which also fought for Poland's independence in the uprising. Its leader Francesco Nullo was killed at the Battle of Krzykawka in 1863. In Poland, Nullo is a national hero, and numerous streets and schools are named in his honour.

The struggle for a united and sovereign nation was a common goal for both countries and was noticed by Goffredo Mameli

Goffredo Mameli (; 5 September 1827 – 6 July 1849) was an Italian patriot, poet, writer and a notable figure in the Risorgimento. He is also the author of the lyrics of "Il Canto degli Italiani", the national anthem of Italy.

Biography

The ...

, a Polonophile and the author of the lyrics in the Italian national anthem, ''Il Canto degli Italiani

"" (; ) is a patriotic song written by Goffredo Mameli and set to music by Michele Novaro in 1847, currently used as the national anthem of Italy. It is best known among Italians as the "" (; ), after the author of the lyrics, or "" (; ), from ...

''. Mameli featured a prominent statement in the last verse of the anthem, ''Già l'Aquila d'Austria, le penne ha perdute. Il sangue d'Italia, il sangue Polacco....'' ("Already the Eagle of Austria has lost its plumes. The blood of Italy, the Polish blood...").

During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Italy established two POW camps for soldiers of Polish nationality conscripted to the Austrian Army, who were then allowed to leave Italy and join the Polish Blue Army in France to fight for Polish independence. The Italian government and people were friendly towards the Polish troops, and Italian cities gifted banners to the newly formed Polish units in Italy.

Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

also greatly contributed to a favourable opinion of the Polish people in Italy and in the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

during his pontificate

The pontificate is the form of government used in Vatican City. The word came to English from French and simply means ''papacy'', or "to perform the functions of the Pope or other high official in the Church". Since there is only one bishop of Ro ...

.

United States

Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko (; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish Military engineering, military engineer, statesman, and military leader who then became a national hero in Poland, the United States, Lithuania, and ...

and Casimir Pulaski

Kazimierz Michał Władysław Wiktor Pułaski (; March 4 or 6, 1745 October 11, 1779), anglicised as Casimir Pulaski ( ), was a Polish nobleman, soldier, and military commander who has been called "The Father of American cavalry" or "The So ...

, who fought for the independence of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and Poland, are seen as the foundation of Polish-American relations. However, the United States began to be involved in Poland's struggle for sovereignty during two uprisings, which took place in the 19th century.

When the November Uprising

The November Uprising (1830–31) (), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in Russian Partition, the heartland of Partitions of Poland, partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. ...

started in 1830, there were very few Poles in the United States, but American views of Poland were shaped positively by their support for the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

. Several young men offered their military services to fight for Poland, the most well-known of which was Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely re ...

, who wrote a letter to his commanding officer on 10 March 1831 to join the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the Army, land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 110,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military histor ...

if it was created in France. Support for Poland was highest in the South, as Pulaski's death in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Brita ...

, was well-remembered and memorialized. The most famous landmark representing American Polonophilia of the time was Fort Pulaski

Fort Pulaski National Monument is located on Cockspur Island between Savannah and Tybee Island, Georgia. It preserves Fort Pulaski, the place where the Union Army successfully tested rifled cannons in 1862, the success of which rendered brick ...

in the State of Georgia

Georgia is a state in the Southeastern United States. It borders Tennessee and North Carolina to the north, South Carolina and the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Florida to the south, and Alabama to the west. Of the 50 U.S. states, Georgia i ...

.

Włodzimierz Bonawentura Krzyżanowski was another hero who fought at the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was a three-day battle in the American Civil War, which was fought between the Union and Confederate armies between July 1 and July 3, 1863, in and around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle, won by the Union, ...

and helped to repel the Louisiana Tigers

"Louisiana Tigers" was the nickname of several infantry units of the Confederate States Army from Louisiana during the American Civil War. Originally applied to a specific company, the nickname expanded to a battalion, then to a brigade, and ...

. He was appointed the governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

of Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

and served as administrator of Alaska Territory

The Territory of Alaska or Alaska Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from August 24, 1912, until Alaska was granted statehood on January 3, 1959. The territory was previously Russian America, 1784–1867; th ...

, a high distinction for a foreigner at the time. He had fled Poland after the failed 1848 Greater Poland Uprising.

Strong support for Poland and pro-Polish sentiment were also observed by US President

Strong support for Poland and pro-Polish sentiment were also observed by US President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

. In 1918, delivered his Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

as peace settlement to end World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and stated in Point 13 that "an independent Polish state should be erected... with a free and secure access to the sea...".

US President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

also expressed his sentiment towards Poland and Polish history in his speech

Speech is the use of the human voice as a medium for language. Spoken language combines vowel and consonant sounds to form units of meaning like words, which belong to a language's lexicon. There are many different intentional speech acts, suc ...

in Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

on 6 July 2017. Trump spoke highly of the spirit of the Polish for defending the freedom and the independence of the country several times at the speech, notably the unity of Poles against the oppression of communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

. He applauded the Poles' prevailing spiritual determination and recalled the gathering of the Poles in 1979 with the famous chant "We want God". Trump also made remarks on Polish economic success and policies towards migrants.

The large Polish-American community maintains some traditional folk customs and contemporary observances, such as Dyngus Day and Pulaski Day, which became well known in American culture. It also includes the influence of Polish cuisine

Polish cuisine ( ) is a style of food preparation originating in and widely popular in Poland. Due to History of Poland, Poland's history, Polish cuisine has evolved over the centuries to be very eclectic, and shares many similarities with other ...

and the spread of famous specialties from Poland like pierogi

Pierogi ( ; ) are filled dumplings made by wrapping Leavening, unleavened dough around a Stuffing, filling and cooked in boiling water. They are occasionally flavored with a savory or sweet garnish. Typical fillings include potato, cheese, ...

, kielbasa

Kielbasa (, ; from Polish ) is any type of meat sausage from Poland and a staple of Polish cuisine. In American English, it is typically a coarse, U-shaped smoked sausage of any kind of meat, which closely resembles the ''Wiejska'' ''sausage'' ...

, Kabana sausage and bagels

A bagel (; ; also spelled beigel) is a bread roll originating in the Jewish communities of Poland. Bagels are traditionally made from yeasted wheat dough that is shaped by hand into a torus or ring, briefly boiled in water, and then baked. T ...

.

See also

*Polonophobia