Neoplesiosauria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an

Skeletal elements of plesiosaurs are among the first fossils of extinct reptiles recognised as such. In 1605, Richard Verstegen of

Skeletal elements of plesiosaurs are among the first fossils of extinct reptiles recognised as such. In 1605, Richard Verstegen of  During the eighteenth century, the number of English plesiosaur discoveries rapidly increased, although these were all of a more or less fragmentary nature. Important collectors were the reverends William Mounsey and Baptist Noel Turner, active in the

During the eighteenth century, the number of English plesiosaur discoveries rapidly increased, although these were all of a more or less fragmentary nature. Important collectors were the reverends William Mounsey and Baptist Noel Turner, active in the

In the early nineteenth century, plesiosaurs were still poorly known and their special build was not understood. No systematic distinction was made with

In the early nineteenth century, plesiosaurs were still poorly known and their special build was not understood. No systematic distinction was made with  Soon afterwards, the

Soon afterwards, the  Plesiosaurs became better known to the general public through two lavishly illustrated publications by the collector Thomas Hawkins: ''Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri'' of 1834 and ''The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons'' of 1840. Hawkins entertained a very idiosyncratic view of the animals, seeing them as monstrous creations of the devil, during a pre-Adamitic phase of history. Hawkins eventually sold his valuable and attractively restored specimens to the British Museum of Natural History.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the number of plesiosaur finds steadily increased, especially through discoveries in the sea cliffs of Lyme Regis. Sir

Plesiosaurs became better known to the general public through two lavishly illustrated publications by the collector Thomas Hawkins: ''Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri'' of 1834 and ''The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons'' of 1840. Hawkins entertained a very idiosyncratic view of the animals, seeing them as monstrous creations of the devil, during a pre-Adamitic phase of history. Hawkins eventually sold his valuable and attractively restored specimens to the British Museum of Natural History.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the number of plesiosaur finds steadily increased, especially through discoveries in the sea cliffs of Lyme Regis. Sir

In 1867, physician Theophilus Turner near

In 1867, physician Theophilus Turner near

The Plesiosauria have their origins within the

The Plesiosauria have their origins within the  From the earliest

From the earliest  The

The

The tooth form and number was very variable. Some forms had hundreds of needle-like teeth. Most species had larger conical teeth with a round or oval cross-section. Such teeth numbered four to six in the premaxilla and about fourteen to twenty-five in the

The tooth form and number was very variable. Some forms had hundreds of needle-like teeth. Most species had larger conical teeth with a round or oval cross-section. Such teeth numbered four to six in the premaxilla and about fourteen to twenty-five in the

order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

or clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

of extinct Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

marine reptile

Marine reptiles are reptiles which have become secondarily adapted for an aquatic or semiaquatic life in a marine environment. Only about 100 of the 12,000 extant reptile species and subspecies are classed as marine reptiles, including mari ...

s, belonging to the Sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic diapsid reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosau ...

.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

Period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Period (punctuation)

* Era, a length or span of time

*Menstruation, commonly referred to as a "period"

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (o ...

, possibly in the Rhaetian

The Rhaetian is the latest age (geology), age of the Triassic period (geology), Period (in geochronology) or the uppermost stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Triassic system (stratigraphy), System (in chronostratigraphy). It was preceded by the N ...

stage, about 203 million years ago. They became especially common during the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

Period, thriving until their disappearance due to the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, also known as the K–T extinction, was the extinction event, mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth approximately 66 million years ago. The event cau ...

at the end of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

Period, about 66 million years ago. They had a worldwide oceanic distribution, and some species at least partly inhabited freshwater environments.

Plesiosaurs were among the first fossil reptiles discovered. In the beginning of the nineteenth century, scientists realised how distinctive their build was and they were named as a separate order in 1835. The first plesiosaurian genus, the eponymous ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable by ...

'', was named in 1821. Since then, more than a hundred valid species have been described. In the early twenty-first century, the number of discoveries has increased, leading to an improved understanding of their anatomy, relationships and way of life.

Plesiosaurs had a broad flat body and a short tail. Their limbs had evolved into four long flippers, which were powered by strong muscles attached to wide bony plates formed by the shoulder girdle and the pelvis. The flippers made a flying movement through the water. Plesiosaurs breathed air, and bore live young; there are indications that they were warm-blooded.

Plesiosaurs showed two main morphological types. Some species, with the "plesiosauromorph" build, had (sometimes extremely) long necks and small heads; these were relatively slow and caught small sea animals. Other species, some of them reaching a length of up to seventeen meters, had the "pliosauromorph" build with a short neck and a large head; these were apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator or superpredator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the hig ...

s, fast hunters of large prey. The two types are related to the traditional strict division of the Plesiosauria into two suborders, the long-necked Plesiosauroidea

Plesiosauroidea (; Greek: 'near, close to' and 'lizard') is an extinct clade of carnivorous marine reptiles. They have the snake-like longest neck to body ratio of any reptile. Plesiosauroids are known from the Jurassic and Cretaceous perio ...

and the short-neck Pliosauroidea

Pliosauroidea is an extinct clade of plesiosaurs, known from the earliest Jurassic to early Late Cretaceous. They are best known for the subclade Thalassophonea, which contained crocodile-like short-necked forms with large heads and massive toot ...

. Modern research, however, indicates that several "long-necked" groups might have had some short-necked members or vice versa. Therefore, the purely descriptive terms "plesiosauromorph" and "pliosauromorph" have been introduced, which do not imply a direct relationship. "Plesiosauroidea" and "Pliosauroidea" today have a more limited meaning. The term "plesiosaur" is properly used to refer to the Plesiosauria as a whole, but informally it is sometimes meant to indicate only the long-necked forms, the old Plesiosauroidea.

Like other ancient marine reptiles, such as those in the clades Ichthyosauria

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on foss ...

and Mosasauria

Mosasauria is a clade of aquatic and semiaquatic squamates that lived during the Cretaceous period. Fossils belonging to the group have been found in all continents around the world. Early mosasaurians like dolichosaurs were small long-bodied ...

, the genera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

in Plesiosauria are not part of the clade Dinosauria.

History of discovery

Early finds

Skeletal elements of plesiosaurs are among the first fossils of extinct reptiles recognised as such. In 1605, Richard Verstegen of

Skeletal elements of plesiosaurs are among the first fossils of extinct reptiles recognised as such. In 1605, Richard Verstegen of Antwerp

Antwerp (; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of Antwerp Province, and the third-largest city in Belgium by area at , after ...

illustrated in his ''A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence'' plesiosaur vertebrae that he referred to fishes and saw as proof that Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

was once connected to the European continent. The Welshman Edward Lhuyd

Edward Lhuyd (1660– 30 June 1709), also known as Edward Lhwyd and by other spellings, was a Welsh scientist, geographer, historian and antiquary. He was the second Keeper of the University of Oxford's Ashmolean Museum, and published the firs ...

in his ''Lithophylacii Brittannici Ichnographia'' from 1699 also included depictions of plesiosaur vertebrae that again were considered fish vertebrae or ''Ichthyospondyli''. Other naturalists during the seventeenth century added plesiosaur remains to their collections, such as John Woodward John Woodward or ''variant'', may refer to:

Sports

*John Woodward (English footballer) (born 1947), former footballer

*John Woodward (Scottish footballer) (born 1949), former footballer

*Johnny Woodward (1924–2002), English footballer

*John D ...

; these were only much later understood to be of a plesiosaurian nature and are today partly preserved in the Sedgwick Museum

The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, is the geology museum of the University of Cambridge. It is part of the Department of Earth Sciences and is located on the university's Downing Site in Downing Street, central Cambridge, England. The Sedg ...

.

In 1719, William Stukeley

William Stukeley (7 November 1687 – 3 March 1765) was an English antiquarian, physician and Anglican clergyman. A significant influence on the later development of archaeology, he pioneered the scholarly investigation of the prehistoric ...

described a partial skeleton of a plesiosaur, which had been brought to his attention by the great-grandfather of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, Robert Darwin of Elston. The stone plate came from a quarry at Fulbeck

Fulbeck is a small village and civil parish in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. The population (including Byards Leap) taken at the 2011 census was 513. The village is on the A607 road, A607, north from Grantham and north-w ...

in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

and had been used, with the fossil at its underside, to reinforce the slope of a watering-hole in Elston

Elston is a village and civil parish in the Newark and Sherwood district, in Nottinghamshire, England, to the south-west of Newark, from the A46 Fosse Way. The population of the civil parish taken at the 2011 census was 631, increasing to 69 ...

in Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated ''Notts.'') is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. The county is bordered by South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. Th ...

. After the strange bones it contained had been discovered, it was displayed in the local vicarage as the remains of a sinner drowned in the Great Flood

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primeva ...

. Stukely affirmed its "diluvial

Diluvium is an archaic term applied during the 1800s to widespread surficial deposits of sediments that could not be explained by the historic action of rivers and seas. Diluvium was initially argued to have been deposited by the action of extra ...

" nature but understood it represented some sea creature, perhaps a crocodile or dolphin. The specimen is today on display at the Natural History Museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history scientific collection, collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleo ...

, and its inventory number is NHMUK PV R.1330 (formerly BMNH R.1330). It is the earliest discovered more or less complete fossil reptile skeleton in a museum collection. It can perhaps be referred to ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable by ...

dolichodeirus''.

During the eighteenth century, the number of English plesiosaur discoveries rapidly increased, although these were all of a more or less fragmentary nature. Important collectors were the reverends William Mounsey and Baptist Noel Turner, active in the

During the eighteenth century, the number of English plesiosaur discoveries rapidly increased, although these were all of a more or less fragmentary nature. Important collectors were the reverends William Mounsey and Baptist Noel Turner, active in the Vale of Belvoir

The Vale of Belvoir ( ) is in Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire, England. The name is from the Norman-French for "beautiful view".

Extent and geology

The vale is a tract of low ground rising east-north-east, drained by the ...

, whose collections were in 1795 described by John Nicholls in the first part of his ''The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicestershire''. One of Turner's partial plesiosaur skeletons is still preserved as specimen NHMUK PV R.45 (formerly BMNH R.45) in the British Museum of Natural History; this is today referred to ''Thalassiodracon

''Thalassiodracon'' (tha-LAS-ee-o-DRAY-kon) is an extinct genus of plesiosauroidea, plesiosauroid from the Pliosauridae that was alive during the Late Triassic-Early Jurassic (Rhaetian-Hettangian) and is known exclusively from the Lower Lias of ...

''.

Naming of ''Plesiosaurus''

In the early nineteenth century, plesiosaurs were still poorly known and their special build was not understood. No systematic distinction was made with

In the early nineteenth century, plesiosaurs were still poorly known and their special build was not understood. No systematic distinction was made with ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosauria is an taxonomy (biology), order of large extinction, extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of ...

, so the fossils of one group were sometimes combined with those of the other to obtain a more complete specimen. In 1821, a partial skeleton discovered in the collection of Colonel Thomas James Birch, was described by William Conybeare and Henry Thomas De la Beche, and recognised as representing a distinctive group. A new genus was named, ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable by ...

''. The generic name was derived from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

πλήσιος, ''plèsios'', "closer to" and the Latinised ''saurus'', in the meaning of "saurian", to express that ''Plesiosaurus'' was in the Chain of Being

The great chain of being is a hierarchical structure of all matter and life, thought by medieval Christianity to have been decreed by God. The chain begins with God and descends through angels, humans, animals and plants to minerals.

The great ...

more closely positioned to the Sauria

Sauria is the clade of diapsids containing the most recent common ancestor of Archosauria (which includes crocodilians and birds) and Lepidosauria (which includes squamates and the tuatara), and all its descendants. Since most molecular phyl ...

, particularly the crocodile, than ''Ichthyosaurus

''Ichthyosaurus'' (derived from Greek () meaning 'fish' and () meaning 'lizard') is a genus of ichthyosaurs from the Early Jurassic (Hettangian - Pliensbachian) of Europe (Belgium, England, Germany and Portugal). Some specimens of the ichthy ...

'', which had the form of a more lowly fish. The name should thus be rather read as "approaching the Sauria" or "near reptile" than as "near lizard". Parts of the specimen are still present in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History (OUMNH) is a museum displaying many of the University of Oxford's natural history specimens, located on Parks Road in Oxford, England. It also contains a lecture theatre which is used by the univers ...

.

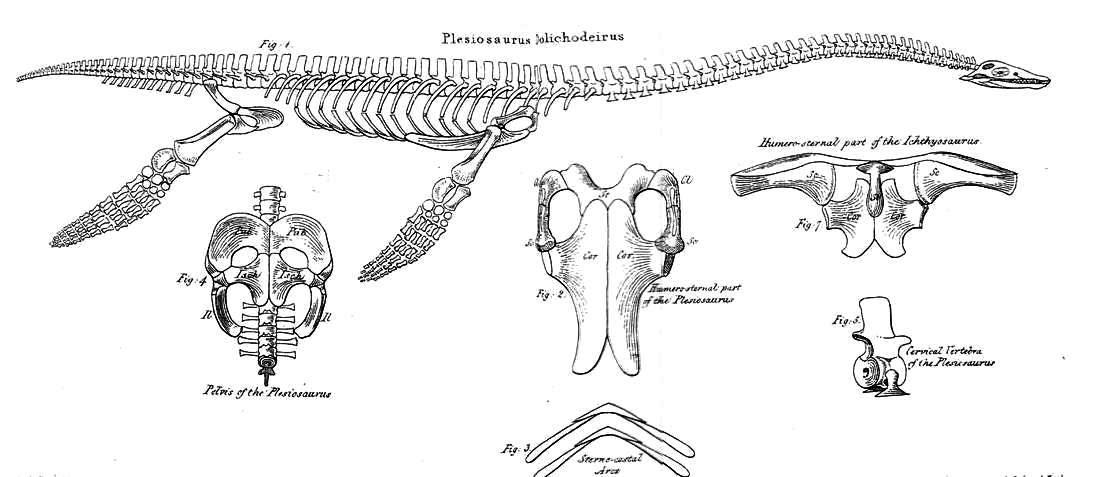

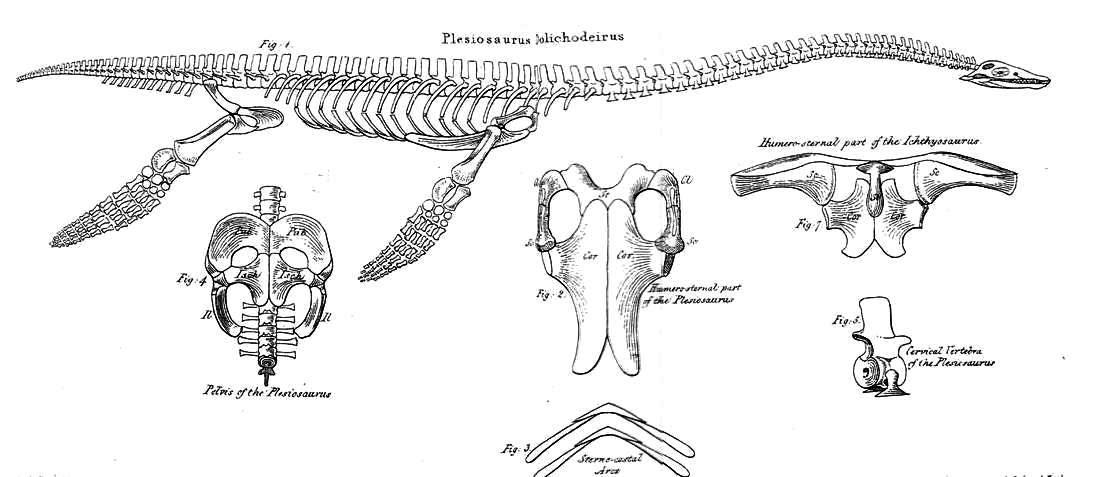

Soon afterwards, the

Soon afterwards, the morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

became much better known. In 1823, Thomas Clark reported an almost complete skull, probably belonging to ''Thalassiodracon'', which is now preserved by the British Geological Survey

The British Geological Survey (BGS) is a partly publicly funded body which aims to advance Earth science, geoscientific knowledge of the United Kingdom landmass and its continental shelf by means of systematic surveying, monitoring and research. ...

as specimen BGS GSM 26035. The same year, commercial fossil collector Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, fossil trade, dealer, and palaeontologist. She became known internationally for her discoveries in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Cha ...

and her family uncovered an almost complete skeleton at Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis ( ) is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester, Dorset, Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and ...

in Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

, England, on what is today called the Jurassic Coast

The Jurassic Coast, also known as the Dorset and East Devon Coast, is a World Heritage Site on the English Channel coast of southern England. It stretches from Exmouth in East Devon to Studland Bay in Dorset, a distance of about , and was ins ...

. It was acquired by the Duke of Buckingham

Duke of Buckingham, referring to the market town of Buckingham, England, is an extinct title that has been created several times in the peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. There were creations of double dukedoms of Bucki ...

, who made it available to the geologist William Buckland

William Buckland Doctor of Divinity, DD, Royal Society, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian, geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist.

His work in the early 1820s proved that Kirkdale Cave in North Yorkshire h ...

. He in turn let it be described by Conybeare on 20 February 1824 in a paper read at the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe, with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

, during the same meeting in which for the first time a dinosaur was named, ''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Ancient Greek, Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic Epoch (Bathonian stage, 166 ...

''. The two finds revealed the unique and bizarre build of the animals, in 1832 by Professor Buckland likened to "a sea serpent run through a turtle". In 1824, Conybeare also provided a specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

to ''Plesiosaurus'': ''dolichodeirus'', meaning "longneck". In 1848, the skeleton was bought by the British Museum of Natural History and catalogued as specimen NHMUK OR 22656 (formerly BMNH 22656). When the paper was published in the Transactions of the Geological Society, Conybeare provisionally named a second species: ''Plesiosaurus giganteus''. This was a short-necked form later assigned to the Pliosauroidea

Pliosauroidea is an extinct clade of plesiosaurs, known from the earliest Jurassic to early Late Cretaceous. They are best known for the subclade Thalassophonea, which contained crocodile-like short-necked forms with large heads and massive toot ...

.

Plesiosaurs became better known to the general public through two lavishly illustrated publications by the collector Thomas Hawkins: ''Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri'' of 1834 and ''The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons'' of 1840. Hawkins entertained a very idiosyncratic view of the animals, seeing them as monstrous creations of the devil, during a pre-Adamitic phase of history. Hawkins eventually sold his valuable and attractively restored specimens to the British Museum of Natural History.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the number of plesiosaur finds steadily increased, especially through discoveries in the sea cliffs of Lyme Regis. Sir

Plesiosaurs became better known to the general public through two lavishly illustrated publications by the collector Thomas Hawkins: ''Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri'' of 1834 and ''The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons'' of 1840. Hawkins entertained a very idiosyncratic view of the animals, seeing them as monstrous creations of the devil, during a pre-Adamitic phase of history. Hawkins eventually sold his valuable and attractively restored specimens to the British Museum of Natural History.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the number of plesiosaur finds steadily increased, especially through discoveries in the sea cliffs of Lyme Regis. Sir Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

alone named nearly a hundred new species. The majority of their descriptions were, however, based on isolated bones, without sufficient diagnosis to be able to distinguish them from the other species that had previously been described. Many of the new species described at this time have subsequently been invalidated. The genus ''Plesiosaurus'' is particularly problematic, as the majority of the new species were placed in it so that it became a wastebasket taxon

Wastebasket taxon (also called a wastebin taxon, dustbin taxon or catch-all taxon) is a term used by some taxonomists to refer to a taxon that has the purpose of classifying organisms that do not fit anywhere else. They are typically defined by e ...

. Gradually, other genera were named. Hawkins had already created new genera, though these are no longer seen as valid. In 1841, Owen named ''Pliosaurus

''Pliosaurus'' (meaning 'more lizard') is an extinct genus of thalassophonean pliosaurid known from the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages) of Europe and South America. This genus has contained many species in the past but recent ...

brachydeirus''. Its etymology

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

referred to the earlier ''Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus'' as it is derived from πλεῖος, ''pleios'', "more fully", reflecting that according to Owen it was closer to the Sauria than ''Plesiosaurus''. Its specific name means "with a short neck". Later, the Pliosauridae

Pliosauridae is a family of plesiosaurian marine reptiles from the Latest Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous ( Rhaetian to Turonian stages). The family is more inclusive than the archetypal short-necked large headed species that are placed ...

were recognised as having a morphology fundamentally different from the plesiosaurids. The family Plesiosauridae

The Plesiosauridae are a monophyletic family (biology), family of plesiosaurs named by John Edward Gray in 1825.Ketchum, H. F., and Benson, R. B. J., 2010. "Global interrelationships of Plesiosauria (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) and the pivotal role ...

had already been coined by John Edward Gray

John Edward Gray (12 February 1800 – 7 March 1875) was a British zoologist. He was the elder brother of zoologist George Robert Gray and son of the pharmacologist and botanist Samuel Frederick Gray (1766–1828). The same is used for a z ...

in 1825. In 1835, Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville

Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville (; 12 September 1777 – 1 May 1850) was a French zoologist and anatomist.

Life

Blainville was born at Arques-la-Bataille, Arques, near Dieppe, Seine-Maritime, Dieppe. As a young man, he went to Paris to study a ...

named the order Plesiosauria itself.

American discoveries

In the second half of the nineteenth century, important finds were made outside of England. While this included some German discoveries, it mainly involved plesiosaurs found in the sediments of the American CretaceousWestern Interior Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, or the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea (geology), inland sea that existed roughly over the present-day Great Plains of ...

, the Niobrara Chalk

The Niobrara Formation , also called the Niobrara Chalk, is a Formation (stratigraphy), geologic formation in North America that was deposited between 87 and 82 million years ago during the Coniacian, Santonian, and Campanian stages of the La ...

. One fossil in particular marked the start of the Bone Wars

The Bone Wars, also known as the Great Dinosaur Rush, was a period of intense and ruthlessly competitive fossil hunting and discovery during the Gilded Age of American history, marked by a heated rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope (of the Aca ...

between the rival paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

and Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of paleontology. A prolific fossil collector, Marsh was one of the preeminent paleontologists of the nineteenth century. Among his legacies are the discovery or ...

.

In 1867, physician Theophilus Turner near

In 1867, physician Theophilus Turner near Fort Wallace

Fort Wallace ( 1865–1882) was a US Cavalry fort built in Wallace County, Kansas to help defend settlers against Cheyenne and Sioux raids and protect the stages. It is located on Pond Creek, and it was named after General W. H. L. Wallace. The ...

in Kansas

Kansas ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the west. Kansas is named a ...

uncovered a plesiosaur skeleton, which he donated to Cope. Cope attempted to reconstruct the animal on the assumption that the longer extremity of the vertebral column was the tail, the shorter one the neck. He soon noticed that the skeleton taking shape under his hands had some very special qualities: the neck vertebrae had chevrons and with the tail vertebrae the joint surfaces were orientated back to front. Excited, Cope concluded to have discovered an entirely new group of reptiles: the Streptosauria or "Turned Saurians", which would be distinguished by reversed vertebrae and a lack of hindlimbs, the tail providing the main propulsion. After having published a description of this animal, followed by an illustration in a textbook about reptiles and amphibians, Cope invited Marsh and Joseph Leidy

Joseph Mellick Leidy (September 9, 1823 – April 30, 1891) was an American paleontologist, parasitologist and anatomist.

Leidy was professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania, later becoming a professor of natural history at Swarth ...

to admire his new ''Elasmosaurus

''Elasmosaurus'' () is a genus of plesiosaur that lived in North America during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous period, at about 80.6 to 77million years ago. The first specimen was discovered in 1867 near Fort Wallace, Kansas, US, and ...

platyurus''. Having listened to Cope's interpretation for a while, Marsh suggested that a simpler explanation of the strange build would be that Cope had reversed the vertebral column relative to the body as a whole. When Cope reacted indignantly to this suggestion, Leidy silently took the skull and placed it against the presumed last tail vertebra, to which it fitted perfectly: it was in fact the first neck vertebra, with still a piece of the rear skull attached to it. Mortified, Cope tried to destroy the entire edition of the textbook and, when this failed, immediately published an improved edition with a correct illustration but an identical date of publication. He excused his mistake by claiming that he had been misled by Leidy himself, who, describing a specimen of ''Cimoliasaurus

''Cimoliasaurus'' was a plesiosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of the eastern United States, with fossils known from New Jersey, North Carolina, and Maryland.

Etymology

The name is derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek ...

'', had also reversed the vertebral column. Marsh later claimed that the affair was the cause of his rivalry with Cope: "he has since been my bitter enemy". Both Cope and Marsh in their rivalry named many plesiosaur genera and species, most of which are today considered invalid.

Around the turn of the century, most plesiosaur research was done by a former student of Marsh, Professor Samuel Wendell Williston

Samuel Wendell Williston (July 10, 1852 – August 30, 1918) was an American educator, entomologist, and Paleontology, paleontologist who was the first to propose that birds developed flight Origin of birds#Origin of bird flight, cursorially (by ...

. In 1914, Williston published his ''Water reptiles of the past and present''. Despite treating sea reptiles in general, it would for many years remain the most extensive general text on plesiosaurs. In 2013, a first modern textbook was being prepared by Olivier Rieppel. During the middle of the twentieth century, the USA remained an important centre of research, mainly through the discoveries of Samuel Paul Welles

Samuel Paul Welles (November 9, 1909 – August 6, 1997) was an American palaeontologist. Welles was a research associate at the Museum of Palaeontology, University of California, Berkeley. He took part in excavations at the Placerias Quarry in ...

.

Recent discoveries

Whereas during the nineteenth and most of the twentieth century, new plesiosaurs were described at a rate of three or four novel genera each decade, the pace suddenly picked up in the 1990s, with seventeen plesiosaurs being discovered in this period. The tempo of discovery accelerated in the early twenty-first century, with about three or four plesiosaurs being named each year. This implies that about half of the known plesiosaurs are relatively new to science, a result of a far more intense field research. Some of this is taking place away from the traditional areas, e.g. in new sites developed inNew Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

and Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

, but the locations of the more original discoveries have proven to be still productive, with important new finds in England and Germany. Some of the new genera are a renaming of already known species, which were deemed sufficiently different to warrant a separate genus name.

In 2002, the " Monster of Aramberri" was announced to the press. Discovered in 1982 at the village of Aramberri, in the northern Mexican state of Nuevo León

Nuevo León, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Nuevo León, is a Administrative divisions of Mexico, state in northeastern Mexico. The state borders the Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Coahuila, Zacatecas, and San Luis Potosí, San Luis ...

, it was originally classified as a dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

. The specimen is actually a very large plesiosaur, possibly reaching in length. The media published exaggerated reports claiming it was long, and weighed up to , which would have made it among the largest predators of all time.

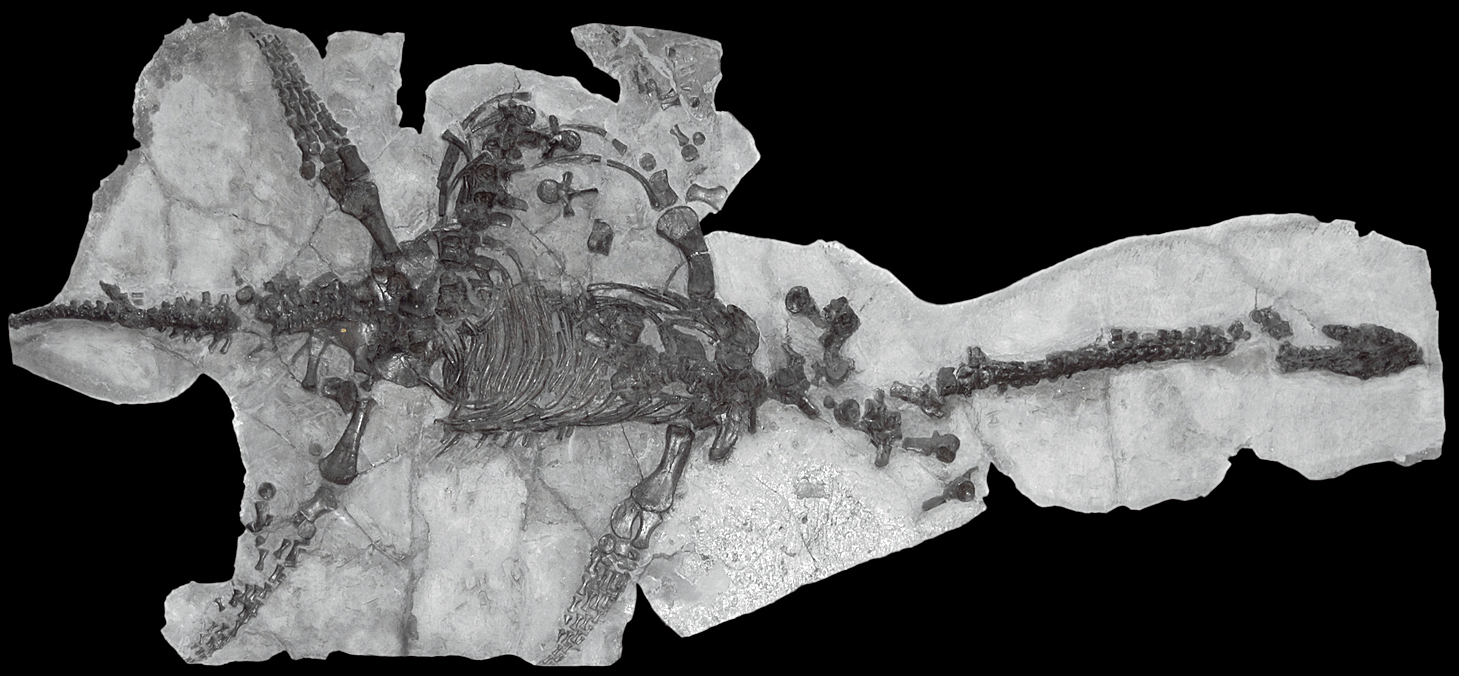

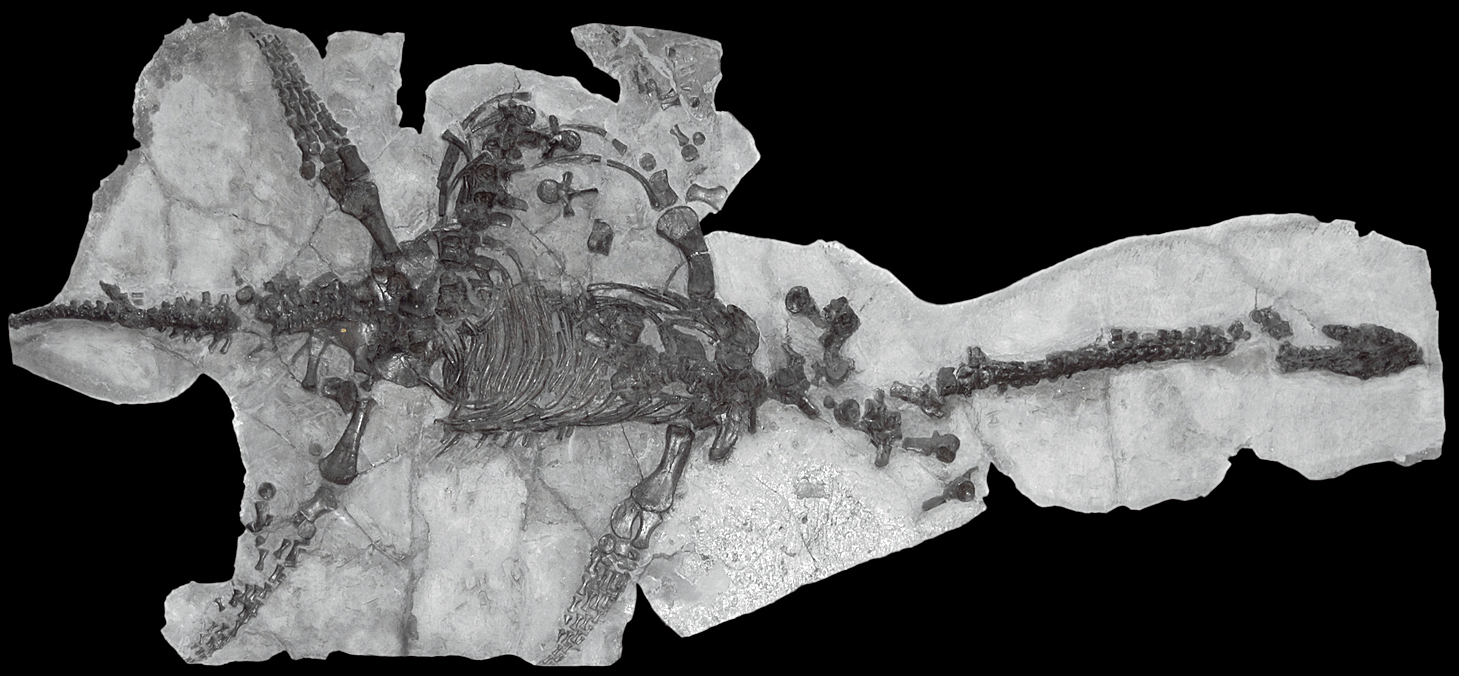

In 2004, what appeared to be a completely intact juvenile plesiosaur was discovered, by a local fisherman, at Bridgwater Bay

Bridgwater Bay is on the Bristol Channel, north of Bridgwater in Somerset, England at the mouth of the River Parrett and the end of the River Parrett Trail. It stretches from Minehead at the southwestern end of the bay to Brean Down in the ...

National Nature Reserve in Somerset, UK. The fossil, dating from 180 million years ago as indicated by the ammonite

Ammonoids are extinct, (typically) coiled-shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (which comprise the clade Coleoidea) than they are to nautiluses (family N ...

s associated with it, measured in length, and may be related to ''Rhomaleosaurus

''Rhomaleosaurus'' (meaning "strong lizard") is an extinct genus of Early Jurassic (Toarcian Faunal stage, age, about 183 to 175.6 million years ago) rhomaleosaurid pliosauroid known from Northamptonshire and from Yorkshire of the United Kingdom. ...

''. It is probably the best preserved specimen of a plesiosaur yet discovered.

In 2005, the remains of three plesiosaurs (''Dolichorhynchops herschelensis

''Dolichorhynchops'' is an extinct genus of polycotylid plesiosaur from the Late Cretaceous of North America, containing the species ''D. osborni'' and ''D. herschelensis'', with two previous species having been assigned to new genera. Definitive ...

'') discovered in the 1990s near Herschel, Saskatchewan

Herschel is a special service area in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Saskatchewan. It is the seat of the Rural Municipality of Mountain View No. 318 and held village status prior to December 31, 2006. The populat ...

were found to be a new species, by Dr. Tamaki Sato, a Japanese vertebrate paleontologist.

In 2006, a combined team of American and Argentinian investigators (the latter from the Argentinian Antarctic Institute and the La Plata Museum

The La Plata Museum () is a natural history museum in La Plata, Argentina. It is part of the (Natural Sciences School) of the National University of La Plata.

The building, long, today houses three million fossils and relics (including 44,000 bo ...

) found the skeleton of a juvenile plesiosaur measuring in length on Vega Island

Vega Island () is an island in Antarctica, long and wide, which is the northernmost of the James Ross Island group and lies in the west part of Erebus and Terror Gulf.

It is separated from James Ross Island by Herbert Sound and from Trinit ...

in Antarctica. The fossil is currently on display at the geological museum of South Dakota School of Mines and Technology

The South Dakota School of Mines & Technology (South Dakota Mines, SD Mines, or SDSM&T) is a public university in Rapid City, South Dakota. It is governed by the South Dakota Board of Regents and was founded in 1885. South Dakota Mines offers b ...

.

In 2008, fossil remains of an undescribed plesiosaur that was named Predator X

''Pliosaurus'' (meaning 'more lizard') is an extinct genus of thalassophonean pliosaurid known from the Late Jurassic ( Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages) of Europe and South America. This genus has contained many species in the past but recent ...

, now known as '' Pliosaurus funkei'', were unearthed in Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norway, Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of continental Europe, mainland Europe, it lies about midway be ...

. It had a length of , and its bite force of is one of the most powerful known.

In December 2017, a large skeleton of a plesiosaur was found on the continent of Antarctica, the oldest creature on the continent, and the first of its species from Antarctica.

Not only has the number of field discoveries increased, but also, since the 1950s, plesiosaurs have been the subject of more extensive theoretical work. The methodology of cladistics

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to Taxonomy (biology), biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesiz ...

has, for the first time, allowed the exact calculation of their evolutionary relationships. Several hypotheses have been published about the way they hunted and swam, incorporating general modern insights about biomechanics

Biomechanics is the study of the structure, function and motion of the mechanical aspects of biological systems, at any level from whole organisms to Organ (anatomy), organs, Cell (biology), cells and cell organelles, using the methods of mechani ...

and ecology

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their Natural environment, environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosystem, and biosphere lev ...

. The many recent discoveries have tested these hypotheses and given rise to new ones.

Evolution

The Plesiosauria have their origins within the

The Plesiosauria have their origins within the Sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic diapsid reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosau ...

, a group of perhaps archelosauria

Archelosauria is a clade grouping turtles and archosaurs (birds and crocodilians) and their fossil relatives, to the exclusion of lepidosaurs (the clade containing lizards, snakes and the tuatara). The majority of phylogenetic analyses based on ...

n reptiles that returned to the sea. An advanced sauropterygian subgroup, the carnivorous Eusauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic diapsid reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosauri ...

with small heads and long necks, split into two branches during the Upper Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch of the Triassic Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch and followed by the Early Jurassic Epoch. T ...

. One of these, the Nothosauroidea, kept functional elbow and knee joints; but the other, the Pistosauria, became more fully adapted to a sea-dwelling lifestyle. Their vertebral column became stiffer and the main propulsion while swimming no longer came from the tail but from the limbs, which changed into flippers. The Pistosauria became warm-blooded and viviparous

In animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the mother, with the maternal circulation providing for the metabolic needs of the embryo's development, until the mother gives birth to a fully or partially developed juve ...

, giving birth to live young. Early, basal, members of the group, traditionally called " pistosaurids", were still largely coastal animals. Their shoulder girdles remained weak, their pelves could not support the power of a strong swimming stroke, and their flippers were blunt. Later, a more advanced pistosaurian group split off: the Plesiosauria. These had reinforced shoulder girdles, flatter pelves, and more pointed flippers. Other adaptations allowing them to colonise the open seas included stiff limb joints; an increase in the number of phalanges of the hand and foot; a tighter lateral connection of the finger and toe phalanx series, and a shortened tail.Rieppel, O., 1997, "Introduction to Sauropterygia", In: Callaway, J. M. & Nicholls, E. L. (eds.), ''Ancient marine reptiles'' pp 107–119. Academic Press, San Diego, California

From the earliest

From the earliest Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

, the Hettangian

The Hettangian is the earliest age and lowest stage of the Jurassic Period of the geologic timescale. It spans the time between 201.3 ± 0.2 Ma and 199.3 ± 0.3 Ma (million years ago). The Hettangian follows the Rhaetian (part of the Triass ...

stage, a rich radiation of plesiosaurs is known, implying that the group must already have diversified in the Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch (geology), epoch of the Triassic geologic time scale, Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between annum, Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch a ...

; of this diversification, however, only a few (very) basal forms have been discovered, the most derived '' Rhaeticosaurus''. The subsequent evolution of the plesiosaurs is very contentious. The various cladistic analyses have not resulted in a consensus about the relationships between the main plesiosaurian subgroups. Traditionally, plesiosaurs have been divided into the long-necked Plesiosauroidea

Plesiosauroidea (; Greek: 'near, close to' and 'lizard') is an extinct clade of carnivorous marine reptiles. They have the snake-like longest neck to body ratio of any reptile. Plesiosauroids are known from the Jurassic and Cretaceous perio ...

and the short-necked Pliosauroidea

Pliosauroidea is an extinct clade of plesiosaurs, known from the earliest Jurassic to early Late Cretaceous. They are best known for the subclade Thalassophonea, which contained crocodile-like short-necked forms with large heads and massive toot ...

. However, modern research suggests that some generally long-necked groups might have had short-necked members. To avoid confusion between the phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or Taxon, taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, M ...

, the evolutionary relationships, and the morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

, the way the animal is built, long-necked forms are therefore called "plesiosauromorph" and short-necked forms are called "pliosauromorph", without the "plesiosauromorph" species necessarily being more closely related to each other than to the "pliosauromorph" forms.

The

The latest common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

of the Plesiosauria was probably a rather small short-necked form. During the earliest Jurassic, the subgroup with the most species was the Rhomaleosauridae

Rhomaleosauridae is a family of plesiosaurs from the Earliest Jurassic to the latest Middle Jurassic (Hettangian to Callovian stages) of Europe, North America, South America and possibly Asia. Most rhomaleosaurids are known from England, many s ...

, a possibly very basal split-off of species which were also short-necked. Plesiosaurs in this period were at most five meters (sixteen feet) long. By the Toarcian

The Toarcian is, in the International Commission on Stratigraphy, ICS' geologic timescale, an age (geology), age and stage (stratigraphy), stage in the Early Jurassic, Early or Lower Jurassic. It spans the time between 184.2 Megaannum, Ma (million ...

, about 180 million years ago, other groups, among them the Plesiosauridae

The Plesiosauridae are a monophyletic family (biology), family of plesiosaurs named by John Edward Gray in 1825.Ketchum, H. F., and Benson, R. B. J., 2010. "Global interrelationships of Plesiosauria (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) and the pivotal role ...

, became more numerous and some species developed longer necks, resulting in total body lengths of up to .

In the middle of the Jurassic, very large Pliosauridae

Pliosauridae is a family of plesiosaurian marine reptiles from the Latest Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous ( Rhaetian to Turonian stages). The family is more inclusive than the archetypal short-necked large headed species that are placed ...

evolved. These were characterized by a large head and a short neck, such as ''Liopleurodon

''Liopleurodon'' (; meaning 'smooth-sided teeth') is an extinct genus of carnivorous pliosaurid pliosaurs that lived from the Callovian stage of the Middle Jurassic to the Kimmeridgian stage of the Late Jurassic period (c. 166 to 155 mya). T ...

'' and ''Simolestes

''Simolestes'' (meaning "snub-nosed thief") is an extinct pliosaurid genus that lived in the Middle to Late Jurassic. The type specimen, NHMUK PV R 3319 is an almost complete but crushed skeleton diagnostic to ''Simolestes vorax'', dating back ...

''. These forms had skulls up to three meters (ten feet) long and reached a length of up to and a weight of ten tons. The pliosaurids had large, conical teeth and were the dominant marine carnivores of their time. During the same time, approximately 160 million years ago, the Cryptoclididae

Cryptoclididae is a family of medium-sized plesiosaurs that existed from the Middle Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous. They had long necks, broad and short skulls and densely packed teeth. They fed on small soft-bodied preys such as small fish and ...

were present, shorter species with a long neck and a small head.

The Leptocleididae

Leptocleididae is a family of small-sized plesiosaurs that lived during the Early Cretaceous period (early Berriasian to early Albian stage). They had small bodies with small heads and short necks. '' Leptocleidus'' and '' Umoonasaurus'' had roun ...

radiated during the Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronology, geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphy, chronostratigraphic name) is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 143.1 ...

. These were rather small forms that, despite their short necks, might have been more closely related to the Plesiosauridae than to the Pliosauridae. Later in the Early Cretaceous, the Elasmosauridae

Elasmosauridae, often called elasmosaurs or elasmosaurids, is an extinct family of plesiosaurs that lived from the Hauterivian stage of the Early Cretaceous to the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period (c. 130 to 66 mya). The taxo ...

appeared; these were among the longest plesiosaurs, reaching up to fifteen meters (fifty feet) in length due to very long necks containing as many as 76 vertebrae, more than any other known vertebrate. Pliosauridae were still present as is shown by large predators, such as ''Kronosaurus

''Kronosaurus'' ( ) is an extinct genus of large short-necked pliosaur that lived during the Aptian to Albian Stage (stratigraphy), stages of the Early Cretaceous in what is now Australia. The first known specimen was received in 1899 and consis ...

''.

At the beginning of the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

, the Ichthyosauria

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on foss ...

became extinct; perhaps a plesiosaur group evolved to fill their niches: the Polycotylidae

Polycotylidae is a family of plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous, a sister group to Leptocleididae. They are known as false pliosaurs. Polycotylids first appeared during the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous, before becoming abundant and widesprea ...

, which had short necks and peculiarly elongated heads with narrow snouts. During the Late Cretaceous, the elasmosaurids still had many species.

All plesiosaurs became extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

as a result of the K-T event at the end of the Cretaceous period, approximately million years ago.

Relationships

In modernphylogeny

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or Taxon, taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, M ...

, clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

s are defined groups that contain all species belonging to a certain branch of the evolutionary tree. One way to define a clade is to let it consist of the last common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

of two such species and all its descendants. Such a clade is called a " node clade". In 2008, Patrick Druckenmiller

Patrick Scott Druckenmiller is a Mesozoic paleontologist, taxonomist, associate professor of geology, Earth Sciences curator, and museum director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North, where he oversees the largest single collection of ...

and Anthony Russell in this way defined Plesiosauria as the group consisting of the last common ancestor of ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable by ...

dolichocheirus'' and ''Peloneustes

''Peloneustes'' (meaning ) is a genus of pliosaurid plesiosaur from the Middle Jurassic of England. Its remains are known from the Peterborough Member of the Oxford Clay Formation, which is Callovian in age. It was originally described as a sp ...

philarchus'' and all its descendants. ''Plesiosaurus'' and ''Peloneustes'' represented the main subgroups of the Plesiosauroidea and the Pliosauroidea and were chosen for historical reasons; any other species from these groups would have sufficed.

Another way to define a clade is to let it consist of all species more closely related to a certain species that one in any case wishes to include in the clade than to another species that one to the contrary desires to exclude. Such a clade is called a " stem clade". Such a definition has the advantage that it is easier to include all species with a certain morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

. Plesiosauria was in 2010 by Hillary Ketchum

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, lawyer and diplomat. She was the 67th United States secretary of state in the administration of Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, a U.S. senator represent ...

and Roger Benson

Roger is a masculine given name, and a surname. The given name is derived from the Old French personal names ' and '. These names are of Germanic languages">Germanic origin, derived from the elements ', ''χrōþi'' ("fame", "renown", "honour") ...

defined as such a stem-based taxon

Phylogenetic nomenclature is a method of nomenclature for taxon, taxa in biology that uses phylogenetics, phylogenetic definitions for taxon names as explained below. This contrasts with Biological classification, the traditional method, by which ...

: "all taxa more closely related to ''Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias Group, Lias of England. It is disting ...

'' and ''Pliosaurus brachydeirus

''Pliosaurus'' (meaning 'more lizard') is an extinct genus of thalassophonean pliosaurid known from the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages) of Europe and South America. This genus has contained many species in the past but recent re ...

'' than to ''Augustasaurus hagdorni

''Augustasaurus'' is an extinct genus of sauropterygians that lived during the Anisian stage of the Middle Triassic in what is now North America. Only one species is known, ''A. hagdorni'', described in 1997 from fossils discovered in the Favret ...

''". Ketchum and Benson (2010) also coined a new clade Neoplesiosauria, a node-based taxon

Phylogenetic nomenclature is a method of nomenclature for taxon, taxa in biology that uses phylogenetics, phylogenetic definitions for taxon names as explained below. This contrasts with Biological classification, the traditional method, by which ...

that was defined by as "''Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus'', ''Pliosaurus brachydeirus'', their most recent common ancestor and all of its descendants". The clade Neoplesiosauria very likely is materially identical to Plesiosauria ''sensu'' Druckenmiller & Russell, thus would designate exactly the same species, and the term was meant to be a replacement of this concept.

Benson ''et al.'' (2012) found the traditional Pliosauroidea to be paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

in relation to Plesiosauroidea. Rhomaleosauridae was found to be outside Neoplesiosauria, but still within Plesiosauria. The early Carnian

The Carnian (less commonly, Karnian) is the lowermost stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Upper Triassic series (stratigraphy), Series (or earliest age (geology), age of the Late Triassic Epoch (reference date), Epoch). It lasted from 237 to 227.3 ...

pistosaur '' Bobosaurus'' was found to be one step more advanced than ''Augustasaurus

''Augustasaurus'' is an extinct genus of sauropterygians that lived during the Anisian stage of the Middle Triassic in what is now North America. Only one species is known, ''A. hagdorni'', described in 1997 from fossils discovered in the Favr ...

'' in relation to the Plesiosauria and therefore it represented by definition the basalmost known plesiosaur. This analysis focused on basal plesiosaurs and therefore only one derived pliosaurid and one cryptoclidia

Plesiosauroidea (; Ancient Greek, Greek: 'near, close to' and 'lizard') is an extinct clade of carnivore, carnivorous Marine (ocean), marine Reptilia, reptiles. They have the snake-like longest neck to body ratio of any reptile. Plesiosauroid ...

n were included, while elasmosaurid

Elasmosauridae, often called elasmosaurs or elasmosaurids, is an extinct family of plesiosaurs that lived from the Hauterivian stage of the Early Cretaceous to the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period (c. 130 to 66 mya). The taxo ...

s were not included at all. A more detailed analysis published by both Benson and Druckenmiller in 2014 was not able to resolve the relationships among the lineages at the base of Plesiosauria.

The following cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

follows an analysis by Benson & Druckenmiller (2014).

Description

Size

In general, plesiosaurians varied in adult length from between to about . The group thus contained some of the largest marineapex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator or superpredator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the hig ...

s in the fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

, roughly equalling the longest ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosauria is an taxonomy (biology), order of large extinction, extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of ...

, mosasaurids

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains were discovered in ...

, sharks

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch cartilaginous fish characterized by a ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, five to seven gill slits on each side, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the ...

and toothed whales

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales with teeth, such as beaked whales and the sperm whales. 73 species of toothed whales are ...

in size. Some plesiosaurian remains, such as a set of highly reconstructed and fragmentary lower jaws preserved in the Oxford University Museum

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History (OUMNH) is a museum displaying many of the University of Oxford's natural history specimens, located on Parks Road in Oxford, England. It also contains a lecture theatre which is used by the univers ...

and referable to ''Pliosaurus rossicus

''Pliosaurus'' (meaning 'more lizard') is an extinct genus of thalassophonean pliosaurid known from the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages) of Europe and South America. This genus has contained many species in the past but recent r ...

'' (previously referred to '' Stretosaurus'' and ''Liopleurodon

''Liopleurodon'' (; meaning 'smooth-sided teeth') is an extinct genus of carnivorous pliosaurid pliosaurs that lived from the Callovian stage of the Middle Jurassic to the Kimmeridgian stage of the Late Jurassic period (c. 166 to 155 mya). T ...

''), indicated a length of . However, it was recently argued that its size cannot be currently determined due to their being poorly reconstructed and a length of or less is more likely.McHenry, Colin Richard (2009). "Devourer of Gods: the palaeoecology of the Cretaceous pliosaur ''Kronosaurus queenslandicus''" (PDF): 1–460 In 2023, the length of its mandible was estimated to be 2.6m, suggesting a length of and a weight of over . MCZ 1285, a specimen currently referable to ''Kronosaurus queenslandicus

''Kronosaurus'' ( ) is an extinct genus of large short-necked pliosaur that lived during the Aptian to Albian stages of the Early Cretaceous in what is now Australia. The first known specimen was received in 1899 and consists of a partially pres ...

'', from the Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronology, geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphy, chronostratigraphic name) is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 143.1 ...

of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, was estimated to have a skull length of . A series of neck vertebrae from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation indicate a pliosaur, probably ''Pliosaurus'', that may have been up to long. A later estimate suggests a length of for these cervicals, as well as for another specimen known from an isolated cervical.

Skeleton

The typical plesiosaur had a broad, flat, body and a shorttail

The tail is the elongated section at the rear end of a bilaterian animal's body; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage extending backwards from the midline of the torso. In vertebrate animals that evolution, evolved to los ...

. Plesiosaurs retained their ancestral two pairs of limbs, which had evolved into large flipper

Flipper may refer to:

Common meanings

*Flipper (anatomy), a forelimb of an aquatic animal, useful for steering and/or propulsion in water

*Swimfins, footwear that boosts human swimming efficiency, also known as flippers

* Flipper (cricket), a typ ...

s. Plesiosaurs were related to the earlier Nothosauridae

Nothosauridae are an extinct family (biology), family of carnivore, carnivorous aquatic sauropterygian reptiles from the Triassic time period of China, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Netherlands, Russia, Switzerland, and northern Africa.

Phyl ...

, that had a more crocodile-like body. The flipper arrangement is unusual for aquatic animals in that probably all four limbs were used to propel the animal through the water by up-and-down movements. The tail was most likely only used for helping in directional control. This contrasts to the ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosauria is an taxonomy (biology), order of large extinction, extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of ...

and the later mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Ancient Greek, Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains wer ...

s, in which the tail provided the main propulsion.

To power the flippers, the shoulder girdle

The shoulder girdle or pectoral girdle is the set of bones in the appendicular skeleton which connects to the arm on each side. In humans, it consists of the clavicle and scapula; in those species with three bones in the shoulder, it consists o ...

and the pelvis

The pelvis (: pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of an Anatomy, anatomical Trunk (anatomy), trunk, between the human abdomen, abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also c ...

had been greatly modified, developing into broad bone plates at the underside of the body, which served as an attachment surface for large muscle groups, able to pull the limbs downwards. In the shoulder, the coracoid

A coracoid is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is present as part of the scapula, but this is n ...

had become the largest element covering the major part of the breast. The scapula

The scapula (: scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side ...

was much smaller, forming the outer front edge of the trunk. To the middle, it continued into a clavicle

The clavicle, collarbone, or keybone is a slender, S-shaped long bone approximately long that serves as a strut between the scapula, shoulder blade and the sternum (breastbone). There are two clavicles, one on each side of the body. The clavic ...

and finally a small interclavicular bone. As with most tetrapods

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four- limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetrapoda (). Tetrapods include all extant and extinct amphibians and amniotes, with the lat ...

, the shoulder joint was formed by the scapula and coracoid. In the pelvis, the bone plate was formed by the ischium

The ischium (; : is ...

at the rear and the larger pubic bone

In vertebrates, the pubis or pubic bone () forms the lower and anterior part of each side of the hip bone. The pubis is the most forward-facing (ventral and anterior) of the three bones that make up the hip bone. The left and right pubic bones ar ...

in front of it. The ilium, which in land vertebrates bears the weight of the hindlimb, had become a small element at the rear, no longer attached to either the pubic bone or the thighbone. The hip joint was formed by the ischium and the pubic bone. The pectoral and pelvic plates were connected by a plastron

The turtle shell is a shield for the ventral and dorsal parts of turtles (the Order (biology), order Testudines), completely enclosing all the turtle's vital organs and in some cases even the head. It is constructed of modified bony elements such ...

, a bone cage formed by the paired belly ribs that each had a middle and an outer section. This arrangement immobilised the entire trunk.

To become flippers, the limbs had changed considerably. The limbs were very large, each about as long as the trunk. The forelimbs and hindlimbs strongly resembled each other. The humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

in the upper arm, and the femur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many quadrupeds, four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The Femo ...

in the upper leg, had become large flat bones, expanded at their outer ends. The elbow joints and the knee joints were no longer functional: the lower arm and the lower leg could not flex in relation to the upper limb elements, but formed a flat continuation of them. All outer bones had become flat supporting elements of the flippers, tightly connected to each other and hardly able to rotate, flex, extend or spread. This was true of the ulna

The ulna or ulnar bone (: ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone in the forearm stretching from the elbow to the wrist. It is on the same side of the forearm as the little finger, running parallel to the Radius (bone), radius, the forearm's other long ...

, radius

In classical geometry, a radius (: radii or radiuses) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its Centre (geometry), center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The radius of a regular polygon is th ...

, metacarpals

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus, also known as the "palm bones", are the appendicular skeleton, appendicular bones that form the intermediate part of the hand between the phalanges (fingers) and the carpal bones (wrist, wris ...

and fingers, as well of the tibia

The tibia (; : tibiae or tibias), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two Leg bones, bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outsi ...

, fibula

The fibula (: fibulae or fibulas) or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. ...

, metatarsals

The metatarsal bones or metatarsus (: metatarsi) are a group of five long bones in the midfoot, located between the tarsal bones (which form the heel and the ankle) and the phalanges (toes). Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are nu ...

and toes. Furthermore, in order to elongate the flippers, the number of phalanges had increased, up to eighteen in a row, a phenomenon called hyperphalangy. The flippers were not perfectly flat, but had a lightly convexly curved top profile, like an airfoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is a streamlined body that is capable of generating significantly more Lift (force), lift than Drag (physics), drag. Wings, sails and propeller blades are examples of airfoils. Foil (fl ...

, to be able to "fly" through the water.

While plesiosaurs varied little in the build of the trunk, and can be called "conservative" in this respect, there were major differences between the subgroups as regards the form of the neck and the skull. Plesiosaurs can be divided into two major morphological types that differ in head and neck

The neck is the part of the body in many vertebrates that connects the head to the torso. It supports the weight of the head and protects the nerves that transmit sensory and motor information between the brain and the rest of the body. Addition ...

size. "Plesiosauromorphs", such as Cryptoclididae

Cryptoclididae is a family of medium-sized plesiosaurs that existed from the Middle Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous. They had long necks, broad and short skulls and densely packed teeth. They fed on small soft-bodied preys such as small fish and ...

, Elasmosauridae

Elasmosauridae, often called elasmosaurs or elasmosaurids, is an extinct family of plesiosaurs that lived from the Hauterivian stage of the Early Cretaceous to the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period (c. 130 to 66 mya). The taxo ...

, and Plesiosauridae

The Plesiosauridae are a monophyletic family (biology), family of plesiosaurs named by John Edward Gray in 1825.Ketchum, H. F., and Benson, R. B. J., 2010. "Global interrelationships of Plesiosauria (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) and the pivotal role ...