Nazi Ukraine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' (RKU; ) was an administrative entity of the

On 22 June 1941,

On 22 June 1941,

The administrative capital of the ''Reichskommissariat'' was Rovno, and it was divided into six ''Generalbezirke'' (general districts), called ''Generalkommissariate'' (general commissariats) in the pre-Barbarossa planning. This administrative structure was in turn subdivided into 114 ''Kreisgebiete'', and further into 443 ''Parteien''.

Each ''Generalbezirk'' was administered by a ''Generalkommissar''; each ''Kreisgebiete'' "circular .e., districtarea" was led by a ''Gebietskommissar'' and each ''Partei'' "party" was governed by a Ukrainian or German "Parteien Chef" ( Party Chief). At the level below were German or Ukrainian ''Akademiker'' ("Academics" – i.e., District Chiefs) (similar to Polish " Wojts" in the General Government). At the same time at a smaller scale, the local Municipalities were administered by native "

The administrative capital of the ''Reichskommissariat'' was Rovno, and it was divided into six ''Generalbezirke'' (general districts), called ''Generalkommissariate'' (general commissariats) in the pre-Barbarossa planning. This administrative structure was in turn subdivided into 114 ''Kreisgebiete'', and further into 443 ''Parteien''.

Each ''Generalbezirk'' was administered by a ''Generalkommissar''; each ''Kreisgebiete'' "circular .e., districtarea" was led by a ''Gebietskommissar'' and each ''Partei'' "party" was governed by a Ukrainian or German "Parteien Chef" ( Party Chief). At the level below were German or Ukrainian ''Akademiker'' ("Academics" – i.e., District Chiefs) (similar to Polish " Wojts" in the General Government). At the same time at a smaller scale, the local Municipalities were administered by native "

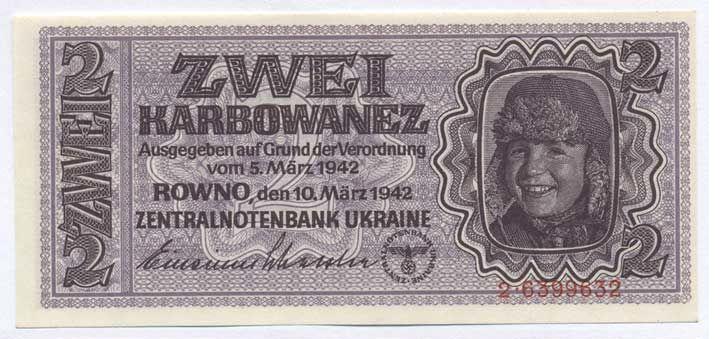

The ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' paid occupation taxes and funds to the

The ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' paid occupation taxes and funds to the

Map of Occupied Europe

{{Authority control *

Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories

The Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (RMfdbO; ), commonly known as the ''Ostministerium'', (; "Eastern Ministry") was a ministry of Nazi Germany responsible for occupied territories in the Baltic states and Soviet Union fro ...

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

from 1941 to 1944. It served as the German civilian

A civilian is a person who is not a member of an armed force. It is war crime, illegal under the law of armed conflict to target civilians with military attacks, along with numerous other considerations for civilians during times of war. If a civi ...

occupation regime in the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

, and parts of the Byelorussian SSR

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, Byelorussian SSR or Byelorussia; ; ), also known as Soviet Belarus or simply Belarus, was a republic of the Soviet Union (USSR). It existed between 1920 and 1922 as an independent state, and ...

, Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

, and eastern Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

during the Eastern Front of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

''Ukraine'' was established after the early success of the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

''s Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

from territory under the military administration

Military administration identifies both the techniques and systems used by military departments, agencies, and armed services involved in managing the armed forces. It describes the processes that take place within military organisations outs ...

of Army Group South Rear Area. The German civil administration was based in Rovno (Rivne) with Erich Koch

Erich Koch (; 19 June 1896 – 12 November 1986) was a ''Gauleiter'' of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in East Prussia from 1 October 1928 until 1945. Between 1941 and 1945 he was Chief of Civil Administration (''Chef der Zivilverwaltung'') of Bezi ...

serving as the only ''Reichskommissar

(, rendered as "Commissioner of the Empire", "Reich Commissioner" or "Imperial Commissioner"), in German history, was an official governatorial title used for various public offices during the period of the German Empire and Nazi Germany.

Ger ...

'' during its existence. ''Ukraine'' was part of the Generalplan Ost

The (; ), abbreviated GPO, was Nazi Germany's plan for the settlement and "Germanization" of captured territory in Eastern Europe, involving the genocide, extermination and large-scale ethnic cleansing of Slavs, Eastern European Jews, and o ...

which included the genocide of the Jewish population, the expulsion and murder of some of the native non-Jewish population, the settlement of Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who lived in Northern Europe in Classical antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In modern scholarship, they typically include not only the Roman-era ''Germani'' who lived in both ''Germania'' and parts of ...

, and the Germanization

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, German people, people, and German culture, culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nati ...

of the rest. The SS and their ''Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also 'task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the imp ...

'', with active participation of the Order Police battalions

Order Police battalions were battalion-sized militarised units of Nazi Germany's ''Ordnungspolizei'' which existed during World War II from 1939 to 1945. They were subordinated to the ''Schutzstaffel'' and deployed in areas of German-occupied E ...

and Ukrainian collaborators. Slavica Publishers. It is estimated 900,000 to 1.6 million Jews and 3 to 4 million non-Jewish Ukrainians

Ukrainians (, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. Their native tongue is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, and the majority adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, forming the List of contemporary eth ...

were killed during the occupation; other sources estimate that 5.2 million Ukrainian civilians (of all ethnic groups) perished due to crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

, war-related disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

, and famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food caused by several possible factors, including, but not limited to war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenom ...

amounting to more than 12% of Ukraine's population at the time.

In the course of 1943 and 1944, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

recaptured most of ''Ukraine'' in their advance westwards. Koch was appointed ''Reichskommissar'' of ''Reichskommissariat Ostland

The (RKO; ) was an Administrative division, administrative entity of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories of Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1945. It served as the German Civil authority, civilian occupation regime in Lithuania, La ...

'' in August 1944 and it was formally dissolved on 10 November 1944.

History

On 22 June 1941,

On 22 June 1941, Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

launched Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

against the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in breach of the mutual Treaty of Non-Aggression. In anticipation of the invasion, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

had tasked Alfred Rosenburg with preparing the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories

The Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (RMfdbO; ), commonly known as the ''Ostministerium'', (; "Eastern Ministry") was a ministry of Nazi Germany responsible for occupied territories in the Baltic states and Soviet Union fro ...

(''Ostministerium'') to oversee administration of the Soviet territories conquered by the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

''.

On 17 July 1941, Hitler issued a Führer decree defining the administration of the newly-occupied Eastern territories.

On 20 August, Hitler established the ''Reichskommissariat

() is a German word for a type of administrative entity headed by a government official known as a '' Reichskommissar'' (). Although many offices existed, primarily throughout the Imperial German and Nazi periods in a number of fields (ranging ...

Ukraine'' and appointed Erich Koch

Erich Koch (; 19 June 1896 – 12 November 1986) was a ''Gauleiter'' of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in East Prussia from 1 October 1928 until 1945. Between 1941 and 1945 he was Chief of Civil Administration (''Chef der Zivilverwaltung'') of Bezi ...

, the ''Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a ''Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany, Gau'' or ''Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest Ranks and insignia of the Nazi Party, rank in ...

'' of East Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

, as its ''Reichskommissar

(, rendered as "Commissioner of the Empire", "Reich Commissioner" or "Imperial Commissioner"), in German history, was an official governatorial title used for various public offices during the period of the German Empire and Nazi Germany.

Ger ...

''. On the same day, Hitler announced that the region would be under civil administration

Civil authority or civil government is the practical implementation of a state on behalf of its citizens, other than through military units (martial law), that enforces law and order and that is distinguished from religious authority (for exampl ...

from noon on 1 September and delineated the boundaries of the region.Berkhoff, p. 36.

In the mind of Hitler and other German expansionists, the destruction of the Soviet Union, dubbed a "Judeo-Bolshevist

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an antisemitic and anti-communist conspiracy theory that claims that the Russian Revolution of 1917 was a Jewish plot and that Jews controlled the Soviet Union and international communist movement ...

" state, would remove a threat from Germany's eastern borders and allow for the colonization of the vast territories of Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

under the banner of ''Lebensraum

(, ) is a German concept of expansionism and Völkisch movement, ''Völkisch'' nationalism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' beca ...

'' for the fulfilment of the material needs of the Germanic people

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who lived in Northern Europe in Classical antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In modern scholarship, they typically include not only the Roman-era ''Germani'' who lived in both ''Germania'' and parts of ...

. Ideological declarations about the German ''Herrenvolk

The master race ( ) is a pseudoscientific concept in Nazi ideology, in which the putative Aryan race is deemed the pinnacle of human racial hierarchy. Members were referred to as ''master humans'' ( ).

The Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg b ...

'' (master race) having a right to expand their territory especially in the East were widely spread among the German public and Nazi officials of various ranks. Later on, in 1943, Koch said about his mission: "We are a master race, which must remember that the lowliest German worker is racially and biologically a thousand times more valuable than the population here."

On 14 December 1941, Rosenberg discussed with Hitler various administrative issues regarding the ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine''.

On 28 July 1944, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

occupied the last part of the ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' in Brest, though it continued to exist as a legal entity. In August 1944, Koch was transferred to ''Reichskommissariat Ostland

The (RKO; ) was an Administrative division, administrative entity of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories of Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1945. It served as the German Civil authority, civilian occupation regime in Lithuania, La ...

'' when its ''Reichskommissar'' Hinrich Lohse

Hinrich Lohse (2 September 1896 – 25 February 1964) was a German Nazi Party official, politician and convicted war criminal. He served as the ''Gauleiter'' and ''Oberpräsident'' of Province of Schleswig-Holstein, Schleswig-Holstein and was an S ...

fled the territory without permission due to the Red Army advance. ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' was officially dissolved on 10 November 1944.

Geography

The ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' excluded several parts of present-dayUkraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, and included some territories outside of its modern borders. It extended in the west from the Volhynia

Volhynia or Volynia ( ; see #Names and etymology, below) is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and northwestern Ukraine. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, but in ...

region around Lutsk

Lutsk (, ; see #Names and etymology, below for other names) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Volyn Oblast and the administrative center of Lutsk Raion within the oblast. Lutsk has a populati ...

, to a line from Vinnytsia

Vinnytsia ( ; , ) is a city in west-central Ukraine, located on the banks of the Southern Bug. It serves as the administrative centre, administrative center of Vinnytsia Oblast. It is the largest city in the historic region of Podillia. It also s ...

to Mykolaiv along the Southern Bug

The Southern Bug, also called Southern Buh (; ; ; or just ), and sometimes Boh River (; ),

river in the south, to the areas surrounding Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, Poltava

Poltava (, ; , ) is a city located on the Vorskla, Vorskla River in Central Ukraine, Central Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Poltava Oblast as well as Poltava Raion within the oblast. It also hosts the administration of Po ...

and Zaporozhye

Zaporizhzhia, formerly known as Aleksandrovsk or Oleksandrivsk until 1921, is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper River. It is the administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zaporizhzhia has a population of

...

in the east. Conquered territories further to the east, including the rest of Ukraine (Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

, Chernigov

Chernihiv (, ; , ) is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within the oblast. Chernihiv's population is

The city was designated as a Hero City of Ukrain ...

, Kharkov

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

, and the Donets Basin

The Seversky Donets () or Siverskyi Donets (), usually simply called the Donets (), is a river on the south of the East European Plain. It originates in the Central Russian Upland, north of Belgorod, flows south-east through Ukraine (Kharkiv ...

), were under military governance until the German withdrawal 1943–44.Berkhoff, pp. 299ff.

Eastern Galicia

Eastern Galicia (; ; ) is a geographical region in Western Ukraine (present day oblasts of Lviv Oblast, Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil Oblast, Ternopil), having also essential historic importance in Poland.

Galicia ( ...

was transferred to the control of the General Government

The General Government (, ; ; ), formally the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (), was a German zone of occupation established after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, Slovak Republic (1939–1945), Slovakia and the Soviet ...

following a Hitler decree, becoming its fifth district, (District of Galicia

The District of Galicia (, , ) was a World War II administrative unit of the General Government created by Nazi Germany on 1 August 1941 after the start of Operation Barbarossa, based loosely within the borders of the ancient Principality o ...

).

It also encompassed several southern parts of today's Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

, including Polesia

Polesia, also called Polissia, Polesie, or Polesye, is a natural (geographic) and historical region in Eastern Europe within the East European Plain, including the Belarus–Ukraine border region and part of eastern Poland. This region shou ...

, a large area to the north of the Pripyat River

The Pripyat or Prypiat is a river in Eastern Europe. The river, which is approximately long, flows east through Ukraine, Belarus, and into Ukraine again, before draining into the Dnieper at Kyiv Reservoir.

Name etymology

Max Vasmer notes in h ...

with forests and marshes, as well as the city of Brest-Litovsk

Brest, formerly Brest-Litovsk and Brest-on-the-Bug, is a city in south-western Belarus at the border with Poland opposite the Polish town of Terespol, where the Bug and Mukhavets rivers meet, making it a border town. It serves as the admini ...

, and the towns of Pinsk

Pinsk (; , ; ; ; ) is a city in Brest Region, Belarus. It serves as the administrative center of Pinsk District, though it is administratively separated from the district. It is located in the historical region of Polesia, at the confluence of t ...

and Mozyr

Mazyr or Mozyr (, ; , ; ; ) is a city in Gomel Region, Belarus. It serves as the administrative center of Mazyr District. It is situated on the Pripyat River about east of Pinsk and northwest of Chernobyl in Ukraine. As of 2025, it has a po ...

.Berkhoff, Karel C. (2004). ''Harvest of despair: life and death in Ukraine under Nazi rule'', p. 37. President and Fellows of Harvard College

The President and Fellows of Harvard College, also called the Harvard Corporation or just the Corporation, is the smaller and more powerful of Harvard University's two governing boards. It refers to itself as the oldest corporation in the Western ...

. This was done by the Germans in order to secure a steady wood supply and efficient railroad and water transportation.

Administration

Political figures related to the German administration of Ukraine

* Alfred Rosenberg,Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories

( ; ) is a German word whose meaning is analogous to the English word "realm". The terms and are respectively used in German in reference to empires and kingdoms. In English usage, the term " Reich" often refers to Nazi Germany, also calle ...

** Georg Leibbrandt

Georg Leibbrandt (6 September 1899 – 16 June 1982) was a German Nazi Party official and civil servant. He occupied leading foreign policy positions in the Nazi Party Foreign Policy Office (APA) and the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern T ...

, Eastern Ministry

** Otto Bräutigam

Otto Bräutigam (14 May 1895 – 30 April 1992) was a German diplomat and lawyer who worked for the '' Auswärtiges Amt'' (German Foreign Office) and for the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories, which was led by Alfred Rosenberg ...

, Eastern Ministry

* ''Reichskommissar

(, rendered as "Commissioner of the Empire", "Reich Commissioner" or "Imperial Commissioner"), in German history, was an official governatorial title used for various public offices during the period of the German Empire and Nazi Germany.

Ger ...

'' of Ukraine, Erich Koch

Erich Koch (; 19 June 1896 – 12 November 1986) was a ''Gauleiter'' of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in East Prussia from 1 October 1928 until 1945. Between 1941 and 1945 he was Chief of Civil Administration (''Chef der Zivilverwaltung'') of Bezi ...

** Alfred Eduard Frauenfeld, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Krim-Taurien

** Kurt Klemm, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Shitomir (October 1941 – October 1942)

** Ernst Ludwig Leyser, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Shitomir (October 1942 – October 1943)

** Helmut Quitzrau, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Kiev (September 1941 – February 1942)

** Waldemar Magunia, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Kiev (February 1942 – 1944)

** Ewald Oppermann, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Nikolajev

** Heinrich Schoene

Heinrich Schoene (25 November 1889 – 9 April 1945) was a Nazi Party official, politician and member of the '' Reichstag''. He was also a member of the Nazi paramilitary ''Sturmabteilung'' (SA) who rose to the rank of SA-''Obergruppenführer''. ...

, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Wolhynien-Podolien (September 1941 – February 1944)

** Claus Selzner, Generalkommissar for Generalbezirk Dnepropetrowsk (September 1941 – June 1944)

* Karl Stumpp, ethnographer

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

and leader of the ''SS Sonderkommando Dr Karl Stumpp''

Military commanders linked with the German administration of Ukraine

* Wehrmachtsbefehlshaber Ukraine (WBU) **Generalleutnant

() is the German-language variant of lieutenant general, used in some German speaking countries.

Austria

Generalleutnant is the second highest general officer rank in the Austrian Armed Forces (''Bundesheer''), roughly equivalent to the NATO ...

d.R. Waldemar Henrici (until October 1942)

** General der Flieger

() was a General of the branch rank of the Luftwaffe (air force) in Nazi Germany. Until the end of World War II in 1945, this particular general officer rank was on three-star level ( OF-8), equivalent to a US Lieutenant general.

The "Genera ...

Karl Kitzinger (from October 1942)

* Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer

The title of SS and Police Leader (') designated a senior Nazi Party official who commanded various components of the SS and the German uniformed police (''Ordnungspolizei''), before and during World War II in the German Reich proper and in the oc ...

Southern Russia ( HSSPF Russland-Süd)

** SS-Obergruppenführer

(, ) was a paramilitary rank in Nazi Germany that was first created in 1932 as a rank of the ''Sturmabteilung'' (SA) and adopted by the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) one year later. Until April 1942, it was the highest commissioned SS rank after ...

Friedrich Jeckeln

Friedrich August Jeckeln (2 February 1895 – 3 February 1946) was a German Nazi Party member, police official and SS-'' Obergruppenführer'' during the Nazi era. He served as a Higher SS and Police Leader in Germany and in the occupied Sov ...

(June–October 1941)

** SS-Obergruppenführer Hans-Adolf Prützmann

Hans-Adolf Prützmann (31 August 1901 – 16 May 1945) was among the highest-ranking German SS officials during the Nazi era. From June 1941 to September 1944, he served as a Higher SS and Police Leader in the occupied Soviet Union, and from Nov ...

(October 1941 – 1944; from October 1943 also Höchster SS- und Polizeiführer (HöSSPF) Ukraine)

* Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer Black Sea ( HSSPF Schwarzes Meer)

** SS-Gruppenführer Ludolf-Hermann von Alvensleben (October–December 1943)

** SS-Obergruppenführer Richard Hildebrandt

Richard Hermann Hildebrandt (13 March 1897 – 10 March 1951) was a German Nazi politician and SS-''Obergruppenführer''. During the Second World War, he served as a Higher SS and Police Leader (HSSPF) in Nazi-occupied Poland, the Soviet Union ...

(December 1943 – August 1944)

* SS-Gruppenführer Adolf von Bomhard, head of police

* SS-Gruppenführer Walter Schimana

Walter Schimana (12 March 1898 – 12 September 1948) was an Austrian Nazi and a general in the SS during the Nazi era. He was SS and Police Leader in the occupied Soviet Union in 1942 and Higher SS and Police Leader in occupied Greece from ...

, commander of the SS Division Galicia

* SS-Brigadeführer Fritz Freitag

Fritz Freitag (28 April 1894 – 10 May 1945) was a German SS commander during the Nazi era. During World War II, he commanded the 2nd SS Infantry Brigade, the SS Cavalry Division Florian Geyer, and the SS Division Galicia. Freitag committed ...

, commander of the SS Division Galicia

Administrative divisions

The administrative capital of the ''Reichskommissariat'' was Rovno, and it was divided into six ''Generalbezirke'' (general districts), called ''Generalkommissariate'' (general commissariats) in the pre-Barbarossa planning. This administrative structure was in turn subdivided into 114 ''Kreisgebiete'', and further into 443 ''Parteien''.

Each ''Generalbezirk'' was administered by a ''Generalkommissar''; each ''Kreisgebiete'' "circular .e., districtarea" was led by a ''Gebietskommissar'' and each ''Partei'' "party" was governed by a Ukrainian or German "Parteien Chef" ( Party Chief). At the level below were German or Ukrainian ''Akademiker'' ("Academics" – i.e., District Chiefs) (similar to Polish " Wojts" in the General Government). At the same time at a smaller scale, the local Municipalities were administered by native "

The administrative capital of the ''Reichskommissariat'' was Rovno, and it was divided into six ''Generalbezirke'' (general districts), called ''Generalkommissariate'' (general commissariats) in the pre-Barbarossa planning. This administrative structure was in turn subdivided into 114 ''Kreisgebiete'', and further into 443 ''Parteien''.

Each ''Generalbezirk'' was administered by a ''Generalkommissar''; each ''Kreisgebiete'' "circular .e., districtarea" was led by a ''Gebietskommissar'' and each ''Partei'' "party" was governed by a Ukrainian or German "Parteien Chef" ( Party Chief). At the level below were German or Ukrainian ''Akademiker'' ("Academics" – i.e., District Chiefs) (similar to Polish " Wojts" in the General Government). At the same time at a smaller scale, the local Municipalities were administered by native "Bailiffs

A bailiff is a manager, overseer or custodian – a legal officer to whom some degree of authority or jurisdiction is given. There are different kinds, and their offices and scope of duties vary.

Another official sometimes referred to as a '' ...

" and "Mayors", accompanied by respective German political advisers if needed. In the most important areas, or where a German Army detachment remained, the local administration was always led by a German; in less significant areas local personnel was in charge.

The six general districts were (English names and administrative centres in parentheses):

* Shitomir (Zhytomyr

Zhytomyr ( ; see #Names, below for other names) is a city in the north of the western half of Ukraine. It is the Capital city, administrative center of Zhytomyr Oblast (Oblast, province), as well as the administrative center of the surrounding ...

) – headed by Regierungpräsident Kurt Klemm, then by SS-Brigadeführer Ernst Ludwig Leyser (from 1942)

* Kiew (Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

) – headed by SA-Brigadeführer Helmut Quitzrau (till February 14, 1942), then SA-Oberführer Waldemar Magunia (from February 14, 1942)

* Nikolajew ( Nikolayev) – headed by NSFK-Obergruppenführer Ewald Oppermann

* Wolhynien und Podolien (Volhynia

Volhynia or Volynia ( ; see #Names and etymology, below) is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and northwestern Ukraine. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, but in ...

and Podolia

Podolia or Podillia is a historic region in Eastern Europe located in the west-central and southwestern parts of Ukraine and northeastern Moldova (i.e. northern Transnistria).

Podolia is bordered by the Dniester River and Boh River. It features ...

; Luzk

Lutsk (, ; see below for other names) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Volyn Oblast and the administrative center of Lutsk Raion within the oblast. Lutsk has a population of

A city with al ...

) – headed by SA Obergruppenführer

(, ) was a paramilitary rank in Nazi Germany that was first created in 1932 as a rank of the ''Sturmabteilung'' (SA) and adopted by the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) one year later. Until April 1942, it was the highest commissioned SS rank after ...

Heinrich Schoene

* Dnjepropetrowsk (Dnepropetrovsk

Dnipro is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper River, Dnipro River, from which it takes its name. Dnipro is t ...

) – headed by '' Oberbefehlshaber der NSDAP'' ('party commander in chief') Claus Selzner

* Krym-Taurien (Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

-Taurida

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as ''Tauris'', ''Taurica'' (), and the ''Tauric Chersonese'' (, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the 5th century BCE when several Greek colonies were established along its coast ...

; Melitopol

Melitopol is a city and municipality in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, southeastern Ukraine. It is situated on the Molochna River, which flows through the eastern edge of the city into the Molochnyi Lyman estuary. Melitopol is the second-largest city ...

) – headed by Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a ''Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany, Gau'' or ''Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest Ranks and insignia of the Nazi Party, rank in ...

Alfred Frauenfeld

Alfred Eduard Frauenfeld (18 May 1898 – 10 May 1977) was an Austrian Nazi leader. An engineer by occupation, he was associated with the pro-German wing of Austrian Nazism.

Early life

Frauenfeld was born in Vienna, the son of a privy councill ...

Scheduled for incorporation into the ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' but never transferred to civil administration were the ''Generalkommissariate Tschernigow'' (Chernigov

Chernihiv (, ; , ) is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within the oblast. Chernihiv's population is

The city was designated as a Hero City of Ukrain ...

), ''Charkow'' (Kharkov

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

), ''Stalino'' (Donetsk

Donetsk ( , ; ; ), formerly known as Aleksandrovka, Yuzivka (or Hughesovka), Stalin, and Stalino, is an industrial city in eastern Ukraine located on the Kalmius River in Donetsk Oblast, which is currently occupied by Russia as the capita ...

), ''Woronezh'' (Voronezh

Voronezh ( ; , ) is a city and the administrative centre of Voronezh Oblast in southwestern Russia straddling the Voronezh River, located from where it flows into the Don River. The city sits on the Southeastern Railway, which connects wes ...

), ''Rostow'' (Rostov-on-Don

Rostov-on-Don is a port city and the administrative centre of Rostov Oblast and the Southern Federal District of Russia. It lies in the southeastern part of the East European Plain on the Don River, from the Sea of Azov, directly north of t ...

), Stalingrad

Volgograd,. geographical renaming, formerly Tsaritsyn. (1589–1925) and Stalingrad. (1925–1961), is the largest city and the administrative centre of Volgograd Oblast, Russia. The city lies on the western bank of the Volga, covering an area o ...

, and ''Saratow'' (Saratov

Saratov ( , ; , ) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River. Saratov had a population of 901,361, making it the List of cities and tow ...

), which would have brought the boundary of the province to the western border of Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

. In addition, ''Reichskommissar'' Koch had wishes of further extending his ''Reichskommissariat'' to Ciscaucasia

The North Caucasus, or Ciscaucasia, is a subregion in Eastern Europe governed by Russia. It constitutes the northern part of the wider Caucasus region, which separates Europe and Asia. The North Caucasus is bordered by the Sea of Azov and the B ...

.

Krym-Taurien

The administrative position of the Krim ''Generalbezirk'' remained ambiguous. According to the original German plan it was to correspond approximately to the oldTaurida Governorate

Taurida Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit ('' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire. It included the territory of the Crimean Peninsula and the mainland between the lower Dnieper River with the coasts of the Black Sea and Sea o ...

(therefore including also mainland portions of Ukraine), and was to consist of two ''Teilbezirke'' (sub-districts):

* Taurien (the mainland sections, including parts of the Nikolayev and Zaporozhye

Zaporizhzhia, formerly known as Aleksandrovsk or Oleksandrivsk until 1921, is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper River. It is the administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zaporizhzhia has a population of

...

provinces.)

* Krym (the Crimean peninsula

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrai ...

)

Only the first of these saw transfer to civil administration in September 1942, with the peninsula remaining under military control for the duration of the war. Its administrator, Frauenfeld, played off the military and civil authorities against each other and gained the freedom to run the territory as he saw fit. He thereby enjoyed complete autonomy, verging on independence, from Koch's authority. Frauenfeld's administration was much more moderate than Koch's and consequentially more economically successful. Koch was greatly angered by Fraunfeld's insubordination (a comparable situation also existed in the administrative relationship between the Estonian general commissariat and ''Reichskommissariat Ostland

The (RKO; ) was an Administrative division, administrative entity of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories of Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1945. It served as the German Civil authority, civilian occupation regime in Lithuania, La ...

'').

The district's title was a misnomer, it only included the area north of the Crimean peninsula

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrai ...

up to the Dnieper river

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

.Berkhoff, p. 39.

Demographics

The official German press, in 1941, reported the Ukrainian urban and rural populations as 19 million each. During the commissariat's existence the Germans only undertook one official census, for January 1, 1943, documenting a population of 16,910,008 people. The 1926 Soviet official census recorded the urban population as 5,373,553 and the rural population as 23,669,381 – a total of 29,042,934, however the borders of the administrative region of the Soviet Ukrainian SSR were noticeably different from those of the ''Reichskommissariat''. In 1939, a new census reported the Ukrainian urban population as 11,195,620 and rural population as 19,764,601 – a total of 30,960,221. The Ukrainian Soviets counted 17% of total Soviet population, and a significant portion was also separately occupied by Romania.Security

The Wehrmacht came under pressure for political reasons to gradually restore private property in zones under military control and to accept local volunteer recruits into their units and into theWaffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

, as promoted by local Ukrainian nationalist organizations, the OUN-B and the OUN-M, whilst receiving political support from the Wehrmacht.

The German ''Reichsführer-SS

(, ) was a special title and rank that existed between the years of 1925 and 1945 for the commander of the (SS). ''Reichsführer-SS'' was a title from 1925 to 1933, and from 1934 to 1945 it was the highest Uniforms and insignia of the Schut ...

'' and chief of German Police, Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and military leader who was the 4th of the (Protection Squadron; SS), a leading member of the Nazi Party, and one of the most powerful p ...

, initially had direct authority over any SS formations in Ukraine to order "Security Operations", but soon lost it – especially after the summer of 1942 when he tried to regain control over policing in Ukraine by gaining authority for the collection of the harvest, and failed miserably, in large part because Koch withheld cooperation. In Ukraine, Himmler soon became the voice of relative moderation, hoping that an improvement in the Ukrainians' living conditions would encourage greater numbers of them to join the Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

's foreign divisions. Koch, appropriately nicknamed the "hangman of Ukraine", was contemptuous of Himmler's efforts. In this matter Koch had the support of Hitler, who remained skeptical when not hostile to the idea of recruiting Slavs

The Slavs or Slavic people are groups of people who speak Slavic languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout the northern parts of Eurasia; they predominantly inhabit Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and ...

in general and Soviet nationals in particular into the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

.

Economic exploitation

In the civil administration of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories numerous technical staff worked underGeorg Leibbrandt

Georg Leibbrandt (6 September 1899 – 16 June 1982) was a German Nazi Party official and civil servant. He occupied leading foreign policy positions in the Nazi Party Foreign Policy Office (APA) and the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern T ...

, former chief of the east section of the foreign political office in the Nazi Party, now chief of the political section in the Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories. Leibbrandt's deputy, Otto Bräutigam

Otto Bräutigam (14 May 1895 – 30 April 1992) was a German diplomat and lawyer who worked for the '' Auswärtiges Amt'' (German Foreign Office) and for the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories, which was led by Alfred Rosenberg ...

, had previously worked as a consul with experience in the Soviet Union. Economic affairs remained under the direct management of Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

(the Plenipotentiary

A ''plenipotentiary'' (from the Latin ''plenus'' "full" and ''potens'' "powerful") is a diplomat who has full powers—authorization to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of a sovereign. When used as a noun more generally, the word can als ...

of Germany's Four Year Plan). From 21 March 1942 Fritz Sauckel

Ernst Friedrich Christoph Sauckel (27 October 1894 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician and convicted war criminal. As General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment ('' Arbeitseinsatz'') from March 1942 until the end of the Second Wor ...

had the role of "General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment" (Generalbevollmächtigter für den Arbeitseinsatz), charged with recruiting manpower for Germany throughout Europe, though in Ukraine Koch insisted that Sauckel confine himself to setting requirements, leaving the actual "recruitment" of ''Ost-Arbeiter

' (, "Eastern worker") was a Nazi German designation for foreign slave workers gathered from occupied Central and Eastern Europe to perform forced labor in Germany during World War II. The Germans started deporting civilians at the beginning ...

'' to Koch and his brutes. The Todt Organization

Organisation Todt (OT; ) was a civil and military engineering organisation in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945, named for its founder, Fritz Todt, an engineer and senior member of the Nazi Party. The organisation was responsible for a huge range o ...

Ost Branch operated from Kiev. Other members of the German administration in Ukraine included Generalkommissar Leyser and Gebietkommissar Steudel.

The Ministry of Transport had direct control of " Ostbahns" and "Generalverkehrsdirektion Osten" (the railway administration in the eastern territories). These German central government interventions in the affairs of the East Affairs by ministries were known as ''Sonderverwaltungen'' (special administrations).

The position of the Eastern Affairs Ministry was weak because its department chiefs: (Economy, Work, Foods & Crops and Forest & Woods) held similar posts in other government departments (The Four-Year Plan, Eastern Economic Office, Foods and Farming Ministry, etc.) with other supplementary junior staff. Thus the East Ministry was managed by personal criteria and particular interests over official orders. Additionally, they failed to maintain the "Political Section" at an equal level with more specialized departments (Economy, Works, Farms, etc.) because political considerations clashed with exploitation plans in the territory.

German Reich

German ''Reich'' (, from ) was the constitutional name for the German nation state that existed from 1871 to 1945. The ''Reich'' became understood as deriving its authority and sovereignty entirely from a continuing unitary German ''Volk'' ("na ...

until February 1944 in the amount of (equivalent to € billion ) and 107.9 million Rbls, in accord with information composed by Lutz von Krosigk, the Reich Minister of Finances.

The Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories ordered Koch and Hinrich Lohse

Hinrich Lohse (2 September 1896 – 25 February 1964) was a German Nazi Party official, politician and convicted war criminal. He served as the ''Gauleiter'' and ''Oberpräsident'' of Province of Schleswig-Holstein, Schleswig-Holstein and was an S ...

(the ''Reichskommissar'' of Ostland) in March 1942 to supply 380,000 farm workers and 247,000 industrial workers for German work needs. Later Koch was mentioned during the new year message of 1943, how he "recruited" 710,000 workers in Ukraine. This and subsequent "worker registration" drives in Ukraine would eventually backfire after the Battle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk, also called the Battle of the Kursk Salient, was a major World War II Eastern Front battle between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union near Kursk in southwestern Russia during the summer of 1943, resulting in ...

(July–August 1943) when the Germans would attempt to build a defensive line along the Dnieper only to discover that the necessary manpower had been either recruited to forced labour in Germany or had gone underground to forestall such "recruitment".

Alfred Rosenberg implemented an " Agrarian New Order" in Ukraine, ordering the confiscation of Soviet state properties to establish German state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

properties. Additionally the replacement of Russian Kolkhoz

A kolkhoz ( rus, колхо́з, a=ru-kolkhoz.ogg, p=kɐlˈxos) was a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union. Kolkhozes existed along with state farms or sovkhoz. These were the two components of the socialized farm sector that began to eme ...

es and Sovkhoz

A sovkhoz ( rus, совхо́з, p=sɐfˈxos, a=ru-sovkhoz.ogg, syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated from , ''sovetskoye khozyaystvo''; ) was a form of state-owned farm or agricultural enterprise in the Soviet Union.

It is usually contrasted w ...

es, by their own "Gemeindwirtschaften" (German Communal Farms), the installation of state enterprise "Landbewirstschaftungsgessellschaft Ukraine M.b.H." for managing the new German state farms and cooperatives, and the foundation of numerous "Kombines" (Great German exploitation Monopolies) with government or private capital in the territory, to exploit the resources and Donbas

The Donbas (, ; ) or Donbass ( ) is a historical, cultural, and economic region in eastern Ukraine. The majority of the Donbas is occupied by Russia as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

The word ''Donbas'' is a portmanteau formed fr ...

area.

German intentions

According to the Nazis, both Jewish and Slavic Ukrainians wereuntermensch

''Untermensch'' (; plural: ''Untermenschen'') is a German language word literally meaning 'underman', 'sub-man', or ' subhuman', which was extensively used by Germany's Nazi Party to refer to their opponents and non- Aryan people they deemed ...

and therefore only fit for enslavement or extermination. Erich Koch

Erich Koch (; 19 June 1896 – 12 November 1986) was a ''Gauleiter'' of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in East Prussia from 1 October 1928 until 1945. Between 1941 and 1945 he was Chief of Civil Administration (''Chef der Zivilverwaltung'') of Bezi ...

, who was chosen by Adolf Hitler to rule Ukraine, made the point about the inferiority of Ukrainians with a certain simplicity: "Even if I find a Ukrainian who is worthy of sitting at my table, I must have him shot" and "remember that the lowliest German worker is racially and biologically a thousand times more valuable than the population here, which is more distinct from Aryan

''Aryan'' (), or ''Arya'' (borrowed from Sanskrit ''ārya''), Oxford English Dictionary Online 2024, s.v. ''Aryan'' (adj. & n.); ''Arya'' (n.)''.'' is a term originating from the ethno-cultural self-designation of the Indo-Iranians. It stood ...

genealogy than Leningrad."

The regime was planning to encourage the settlement of German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

and other " Germanic" farmers in the region after the war, along with the empowerment of some ethnic Germans in the territory. Ukraine was the furthest eastern settlement of the migrating ancient Goths between the 2nd and 4th centuries and subsequently, according to Hitler, "Only German should be spoken here".

In Ukraine, the Germans published a local journal in the German language, the ''Deutsche Ukrainezeitung''.

During the occupation a very small number of cities and their accompanying districts maintained German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

names. These cities were designated as urban strongholds for Volksdeutsche natives.Lower, p. 267. '' Hegewald'' (Himmler's field headquarters and the location of a small, experimental German colony), '' Försterstadt'' (also a Volksdeutsche colony), '' Halbstadt'' (a Low German Mennonite

Mennonites are a group of Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian communities tracing their roots to the epoch of the Radical Reformation. The name ''Mennonites'' is derived from the cleric Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, part of ...

settlement), ''Alexanderstadt'', ''Kronau'' and '' Friesendorf'' were some of these.

On 12 August 1941, Hitler ordered the complete destruction of the Ukrainian capital of Kiev by the use of incendiary bombs

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires. They may destroy structures or sensitive equipment using fire, and sometimes operate as anti-personnel weaponry. Incendiarie ...

and gunfire.Berkhoff, pp. 164–165. Because the German military lacked sufficient material for this operation it wasn't carried out, after which the Nazi planners instead decided to starve the city's inhabitants. Heinrich Himmler on the other hand considered Kiev to be "an ancient German city" because of the Magdeburg city rights

Magdeburg rights (, , ; also called Magdeburg Law) were a set of town privileges first developed by Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor (936–973) and based on the Flemish Law, which regulated the degree of internal autonomy within cities and villages gr ...

that it had acquired centuries prior.

See also

*Babi Yar

Babi Yar () or Babyn Yar () is a ravine in the Ukraine, Ukrainian capital Kyiv and a site of massacres carried out by Nazi Germany's forces during Eastern Front (World War II), its campaign against the Soviet Union in World War II. The first and ...

* The Death Match

The Death Match (, ) is a name given in postwar Soviet historiography to the football match played on 9 August 1942 in Kyiv in ''Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' under occupation by Nazi Germany. The Kyiv city team ''Start'' (Cyrillic: Старт), w ...

* Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

The Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia (; ) were carried out in Occupation of Poland (1939–1945), German-occupied Poland by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), with the support of parts of the local Ukrainians, Ukrainian popu ...

* ''Ostarbeiter

' (, "Eastern worker") was a Nazi German designation for foreign slave workers gathered from occupied Central and Eastern Europe to perform forced labor in Germany during World War II. The Germans started deporting civilians at the beginning ...

''

* '' Word of the Righteous''

References

Further reading

* . * . * .External links

*Map of Occupied Europe

{{Authority control *

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

German occupation of Poland during World War II

Byelorussia in World War II

Military history of Germany during World War II

Military history of the Soviet Union during World War II

Holocaust locations

*

1941 establishments in Ukraine

1944 disestablishments in Ukraine

States and territories established in 1941

States and territories disestablished in 1944

Babi Yar

German military occupations