Myristoylation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Myristoylation is a lipidation modification where a myristoyl group, derived from

Myristoylation is a lipidation modification where a myristoyl group, derived from

The enzyme ''N''-myristoyltransferase (NMT) or glycylpeptide ''N''-tetradecanoyltransferase is responsible for the irreversible addition of a myristoyl group to ''N''-terminal or internal glycine residues of proteins. This modification can occur co-translationally or post-translationally. In vertebrates, this modification is carried about by two NMTs, NMT1 and NMT2, both of which are members of the GCN5

The enzyme ''N''-myristoyltransferase (NMT) or glycylpeptide ''N''-tetradecanoyltransferase is responsible for the irreversible addition of a myristoyl group to ''N''-terminal or internal glycine residues of proteins. This modification can occur co-translationally or post-translationally. In vertebrates, this modification is carried about by two NMTs, NMT1 and NMT2, both of which are members of the GCN5

The MYR PredictorExPASy Myristoylation Tool

{{Protein posttranslational modification Post-translational modification Signal transduction

Myristoylation is a lipidation modification where a myristoyl group, derived from

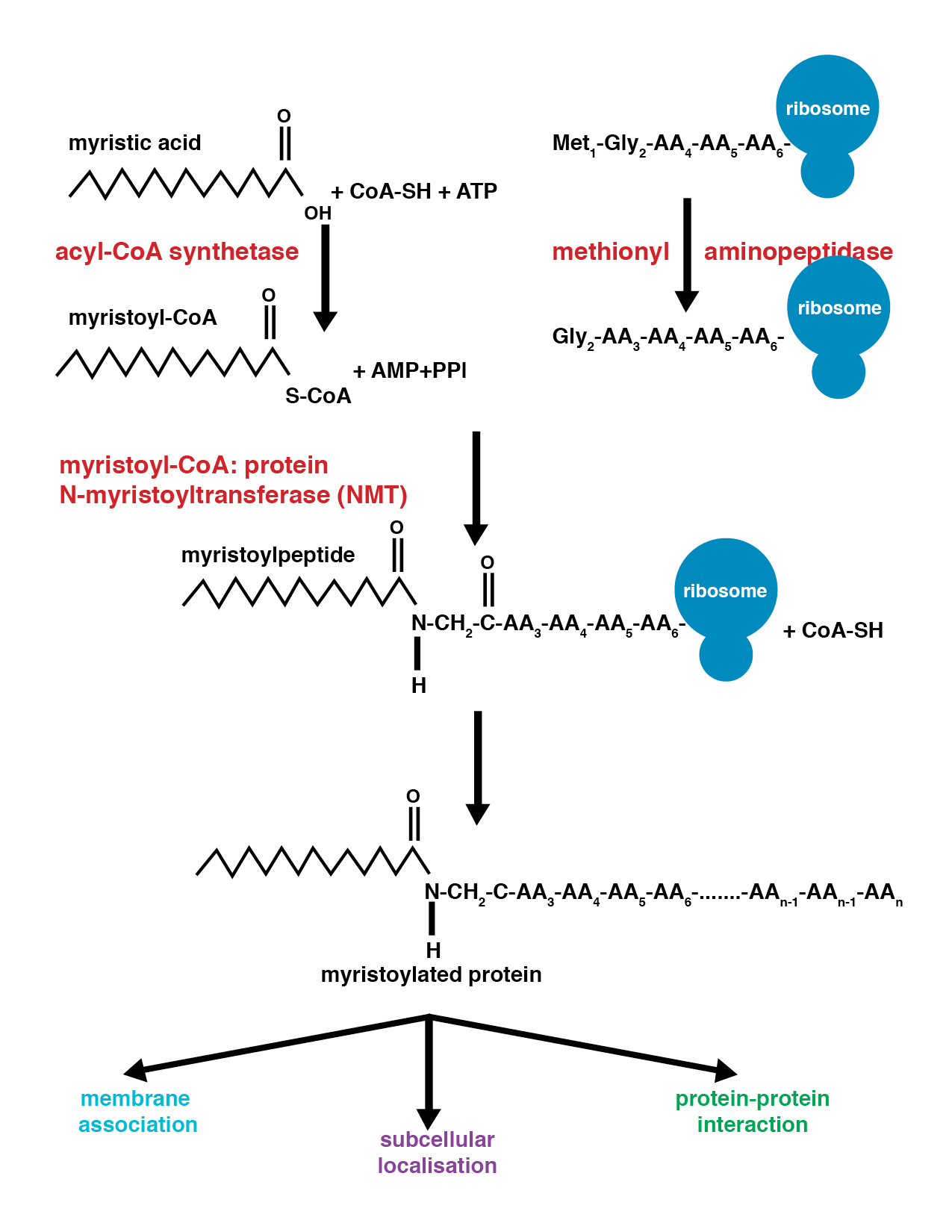

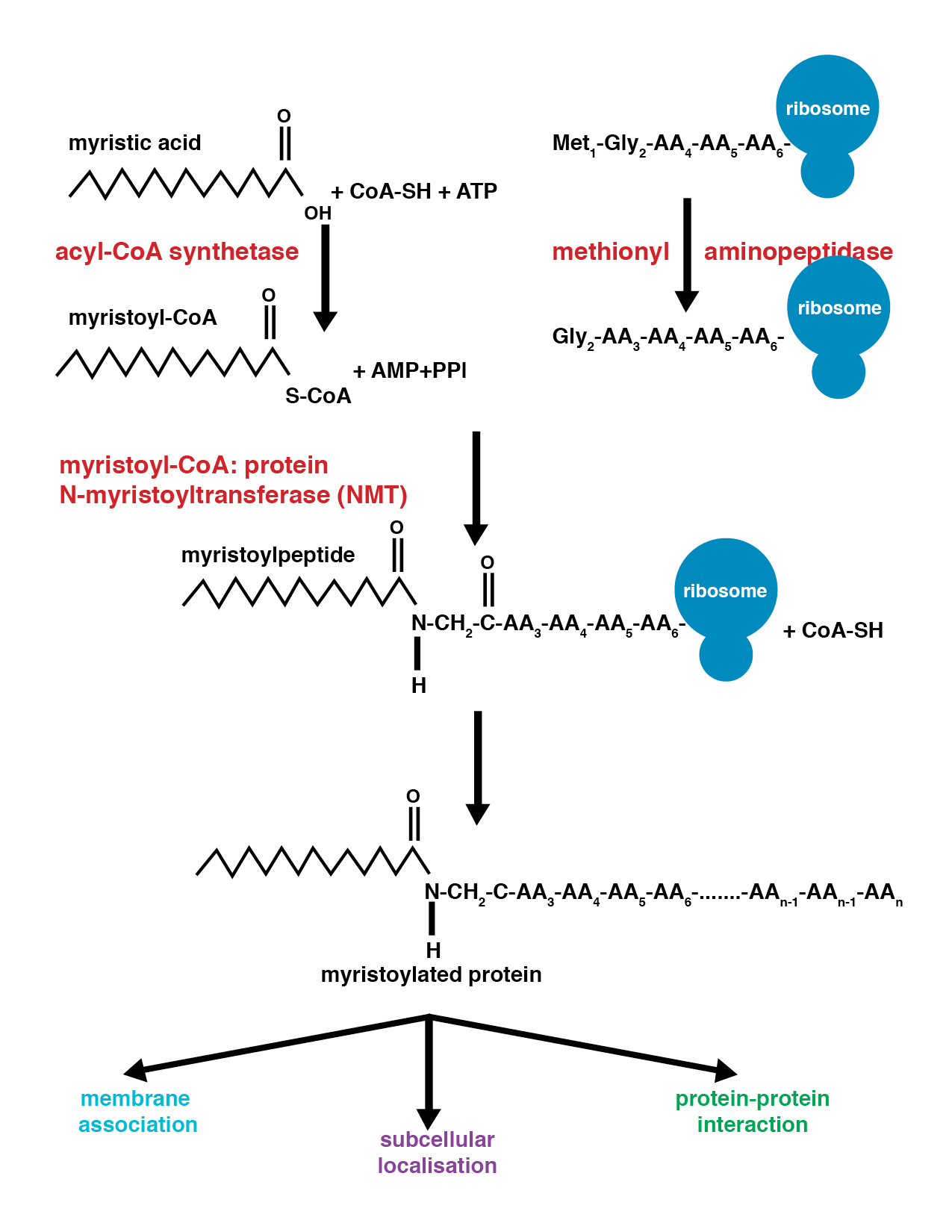

Myristoylation is a lipidation modification where a myristoyl group, derived from myristic acid

Myristic acid (IUPAC name: tetradecanoic acid) is a common saturated fatty acid with the molecular formula . Its salts and esters are commonly referred to as myristates or tetradecanoates. The name of the acyl group derived from myristic acid is m ...

, is covalent

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atom ...

ly attached by an amide bond to the alpha-amino group of an ''N''-terminal glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid. Glycine is one of the proteinogenic amino acids. It is encoded by all the codons starting with GG (G ...

residue. Myristic acid is a 14-carbon saturated fatty acid (14:0) with the systematic name of ''n''-tetradecanoic acid. This modification can be added either co-translationally or post-translationally. ''N''-myristoyltransferase (NMT) catalyzes the myristic acid

Myristic acid (IUPAC name: tetradecanoic acid) is a common saturated fatty acid with the molecular formula . Its salts and esters are commonly referred to as myristates or tetradecanoates. The name of the acyl group derived from myristic acid is m ...

addition reaction in the cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

of cells. This lipidation event is the most common type of fatty acylation and is present in many organisms, including animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Biology, biological Kingdom (biology), kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, ...

s, plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s, fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

, protozoan

Protozoa (: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically ...

s and virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es. Myristoylation allows for weak protein–protein and protein–lipid interactions and plays an essential role in membrane targeting, protein–protein interaction

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) are physical contacts of high specificity established between two or more protein molecules as a result of biochemical events steered by interactions that include electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding and t ...

s and functions widely in a variety of signal transduction

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a biochemical cascade, series of molecular events. Proteins responsible for detecting stimuli are generally termed receptor (biology), rece ...

pathways.

Discovery

In 1982, Koiti Titani's lab identified an "''N''-terminal blocking group" on the catalytic subunit of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in cows as ''n''-tetradecanoyl. Almost simultaneously in Claude B. Klee's lab, this same ''N''-terminal blocking group was further characterized as myristic acid. Both labs made this discovery utilizing similar techniques:mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a ''mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is used ...

and gas chromatography

Gas chromatography (GC) is a common type of chromatography used in analytical chemistry for Separation process, separating and analyzing compounds that can be vaporized without Chemical decomposition, decomposition. Typical uses of GC include t ...

.

''N''-myristoyltransferase

The enzyme ''N''-myristoyltransferase (NMT) or glycylpeptide ''N''-tetradecanoyltransferase is responsible for the irreversible addition of a myristoyl group to ''N''-terminal or internal glycine residues of proteins. This modification can occur co-translationally or post-translationally. In vertebrates, this modification is carried about by two NMTs, NMT1 and NMT2, both of which are members of the GCN5

The enzyme ''N''-myristoyltransferase (NMT) or glycylpeptide ''N''-tetradecanoyltransferase is responsible for the irreversible addition of a myristoyl group to ''N''-terminal or internal glycine residues of proteins. This modification can occur co-translationally or post-translationally. In vertebrates, this modification is carried about by two NMTs, NMT1 and NMT2, both of which are members of the GCN5 acetyltransferase

An acetyltransferase (also referred to as a transacetylase) is any of a class of transferase enzymes that transfers an acetyl group in a reaction called acetylation. In biological organisms, post-translational modification of a protein via acetyl ...

superfamily.

Structure

Thecrystal structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of ordered arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from intrinsic nature of constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that repeat ...

of NMT reveals two identical subunits, each with its own myristoyl CoA binding site. Each subunit consists of a large saddle-shaped β-sheet

The beta sheet (β-sheet, also β-pleated sheet) is a common structural motif, motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone chain, backbon ...

surrounded by α-helices

An alpha helix (or α-helix) is a sequence of amino acids in a protein that are twisted into a coil (a helix).

The alpha helix is the most common structural arrangement in the secondary structure of proteins. It is also the most extreme type of l ...

. The symmetry of the fold is pseudo twofold. Myristoyl CoA binds at the ''N''-terminal portion, while the ''C''-terminal end binds the protein.

Mechanism

The addition of the myristoyl group proceeds via a nucleophilic addition-elimination reaction. First, myristoyl coenzyme A (CoA) is positioned in its binding pocket of NMT so that thecarbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group with the formula , composed of a carbon atom double bond, double-bonded to an oxygen atom, and it is divalent at the C atom. It is common to several classes of organic compounds (such a ...

faces two amino acid residues, phenylalanine

Phenylalanine (symbol Phe or F) is an essential α-amino acid with the chemical formula, formula . It can be viewed as a benzyl group substituent, substituted for the methyl group of alanine, or a phenyl group in place of a terminal hydrogen of ...

170 and leucine

Leucine (symbol Leu or L) is an essential amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Leucine is an α-amino acid, meaning it contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH3+ form under biological conditions), an α-Car ...

171. This polarizes the carbonyl so that there is a net positive charge on the carbon, making it susceptible to nucleophilic attack by the glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid. Glycine is one of the proteinogenic amino acids. It is encoded by all the codons starting with GG (G ...

residue of the protein to be modified. When myristoyl CoA binds, NMT reorients to allow binding of the peptide. The ''C''-terminus of NMT then acts as a general base to deprotonate

Deprotonation (or dehydronation) is the removal (transfer) of a proton (or hydron, or hydrogen cation), (H+) from a Brønsted–Lowry acid in an acid–base reaction.Henry Jakubowski, Biochemistry Online Chapter 2A3, https://employees.csbsju.ed ...

the NH3+, activating the amino group

In chemistry, amines (, ) are organic compounds that contain carbon-nitrogen bonds. Amines are formed when one or more hydrogen atoms in ammonia are replaced by alkyl or aryl groups. The nitrogen atom in an amine possesses a lone pair of elec ...

to attack at the carbonyl group

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group with the formula , composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom, and it is divalent at the C atom. It is common to several classes of organic compounds (such as aldehydes ...

of myristoyl-CoA. The resulting tetrahedral intermediate

A tetrahedral intermediate is a reaction intermediate in which the bond arrangement around an initially double-bonded carbon atom has been transformed from trigonal to tetrahedral. Tetrahedral intermediates result from nucleophilic addition to a c ...

is stabilized by the interaction between a positively charged oxyanion hole

An oxyanion hole is a pocket in the active site of an enzyme that stabilizes transition state negative charge on a deprotonation, deprotonated oxygen or alkoxide. The pocket typically consists of backbone amides or positively charged residues. Sta ...

and the negatively charged alkoxide

In chemistry, an alkoxide is the conjugate base of an alcohol and therefore consists of an organic group bonded to a negatively charged oxygen atom. They are written as , where R is the organyl substituent. Alkoxides are strong bases and, whe ...

anion. Free CoA is then released, causing a conformational change

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors.

A macromolecule is usually flexible and dynamic. Its shape can change in response to changes in its environment or othe ...

in the enzyme that allows the release of the myristoylated peptide.

Co-translational vs. post-translational addition

Co-translational and post-translational covalent modifications enable proteins to develop higher levels of complexity in cellular function, further adding diversity to theproteome

A proteome is the entire set of proteins that is, or can be, expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, or organism at a certain time. It is the set of expressed proteins in a given type of cell or organism, at a given time, under defined conditions. P ...

. The addition of myristoyl-CoA to a protein can occur during protein translation or after. During co-translational addition of the myristoyl group, the ''N''-terminal glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid. Glycine is one of the proteinogenic amino acids. It is encoded by all the codons starting with GG (G ...

is modified following cleavage of the ''N''-terminal methionine

Methionine (symbol Met or M) () is an essential amino acid in humans.

As the precursor of other non-essential amino acids such as cysteine and taurine, versatile compounds such as SAM-e, and the important antioxidant glutathione, methionine play ...

residue in the newly forming, growing polypeptide

Peptides are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. A polypeptide is a longer, continuous, unbranched peptide chain. Polypeptides that have a molecular mass of 10,000 Da or more are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty ...

. Post-translational myristoylation typically occurs following a caspase

Caspases (cysteine-aspartic proteases, cysteine aspartases or cysteine-dependent aspartate-directed proteases) are a family of protease enzymes playing essential roles in programmed cell death. They are named caspases due to their specific cyste ...

cleavage event, resulting in the exposure of an internal glycine residue, which is then available for myristic acid addition.

Functions

Myristoylated proteins

Myristoylation molecular switch

Myristoylation not only diversifies the function of a protein, but also adds layers of regulation to it. One of the most common functions of the myristoyl group is in membrane association and cellular localization of the modified protein. Though the myristoyl group is added onto the end of the protein, in some cases it is sequestered withinhydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the chemical property of a molecule (called a hydrophobe) that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water. In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, thu ...

regions of the protein rather than solvent exposed. By regulating the orientation of the myristoyl group, these processes can be highly coordinated and closely controlled. Myristoylation is thus a form of " molecular switch."

Both hydrophobic myristoyl groups and "basic patches" (highly positive regions on the protein) characterize myristoyl-electrostatic switches. The basic patch allows for favorable electrostatic interaction

Electrostatics is a branch of physics that studies slow-moving or stationary electric charges.

Since classical times, it has been known that some materials, such as amber, attract lightweight particles after rubbing. The Greek word (), meani ...

s to occur between the negatively charged phospholipid heads of the membrane and the positive surface of the associating protein. This allows tighter association and directed localization of proteins.

Myristoyl-conformational switches can come in several forms. Ligand binding to a myristoylated protein with its myristoyl group sequestered can cause a conformational change

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors.

A macromolecule is usually flexible and dynamic. Its shape can change in response to changes in its environment or othe ...

in the protein, resulting in exposure of the myristoyl group. Similarly, some myristoylated proteins are activated not by a designated ligand, but by the exchange of GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the total market value of all the final goods and services produced and rendered in a specific time period by a country or countries. GDP is often used to measure the economic performance o ...

for GTP by guanine nucleotide exchange factor

Guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) are proteins or protein domains that activate monomeric GTPases by stimulating the release of guanosine diphosphate (GDP) to allow binding of guanosine triphosphate (GTP). A variety of unrelated structu ...

s in the cell. Once GTP is bound to the myristoylated protein, it becomes activated, exposing the myristoyl group. These conformational switches can be utilized as a signal for cellular localization, membrane-protein, and protein–protein interaction

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) are physical contacts of high specificity established between two or more protein molecules as a result of biochemical events steered by interactions that include electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding and t ...

s.

Dual modifications of myristoylated proteins

Further modifications on ''N''-myristoylated proteins can add another level of regulation for myristoylated protein. Dualacylation

In chemistry, acylation is a broad class of chemical reactions in which an acyl group () is added to a substrate. The compound providing the acyl group is called the acylating agent. The substrate to be acylated and the product include the foll ...

can facilitate more tightly regulated protein localization, specifically targeting proteins to lipid rafts at membranes or allowing dissociation of myristoylated proteins from membranes.

Myristoylation and palmitoylation

In molecular biology, palmitoylation is the covalent attachment of fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, to cysteine (''S''-palmitoylation) and less frequently to serine and threonine (''O''-palmitoylation) residues of proteins, which are typic ...

are commonly coupled modifications. Myristoylation alone can promote transient membrane interactions that enable proteins to anchor to membranes but dissociate easily. Further palmitoylation allows for tighter anchoring and slower dissociation from membranes when required by the cell. This specific dual modification is important for G protein-coupled receptor

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), also known as seven-(pass)-transmembrane domain receptors, 7TM receptors, heptahelical receptors, serpentine receptors, and G protein-linked receptors (GPLR), form a large group of evolutionarily related ...

pathways and is referred to as the dual fatty acylation switch.

Myristoylation is often followed by phosphorylation

In biochemistry, phosphorylation is described as the "transfer of a phosphate group" from a donor to an acceptor. A common phosphorylating agent (phosphate donor) is ATP and a common family of acceptor are alcohols:

:

This equation can be writ ...

of nearby residues. Additional phosphorylation of the same protein can decrease the electrostatic affinity of the myristoylated protein for the membrane, causing translocation of that protein to the cytoplasm following dissociation from the membrane.

Signal transduction

Myristoylation plays a vital role in membrane targeting andsignal transduction

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a biochemical cascade, series of molecular events. Proteins responsible for detecting stimuli are generally termed receptor (biology), rece ...

in plant responses to environmental stress. In addition, in signal transduction via G protein, palmitoylation

In molecular biology, palmitoylation is the covalent attachment of fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, to cysteine (''S''-palmitoylation) and less frequently to serine and threonine (''O''-palmitoylation) residues of proteins, which are typic ...

of the α subunit, prenylation

Prenylation (also known as isoprenylation or lipidation) is the addition of hydrophobic molecules to a protein or a biomolecule. It is usually assumed that prenyl groups (3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl) facilitate attachment to cell membranes, similar to ...

of the γ subunit, and myristoylation is involved in tethering the G protein to the inner surface of the plasma membrane so that the G protein can interact with its receptor.

Apoptosis

Myristoylation is an integral part ofapoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

, or programmed cell death. Apoptosis is necessary for cell homeostasis and occurs when cells are under stress such as hypoxia or DNA damage

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is constantly modified ...

. Apoptosis can proceed by either mitochondrial or receptor mediated activation. In receptor mediated apoptosis, apoptotic pathways are triggered when the cell binds a death receptor. In one such case, death receptor binding initiates the formation of the death-inducing signaling complex

The death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) is a multiprotein complex formed by members of the death receptor family of apoptosis-inducing cellular receptors. A typical example is FasR, which forms the DISC upon trimerization as a result of it ...

, a complex composed of numerous proteins including several caspases, including caspase 3

Caspase-3 is a caspase protein that interacts with caspase-8 and caspase-9. It is encoded by the ''CASP3'' gene. ''CASP3'' orthologs have been identified in numerous mammals for which complete genome data are available. Unique orthologs are als ...

. Caspase 3 cleaves a number of proteins that are subsequently myristoylated by NMT. The pro-apoptotic BH3-interacting domain death agonist (Bid) is one such protein that once myristoylated, translocates to the mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

where it prompts the release of cytochrome c leading to cell death. Actin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of ...

, gelsolin

Gelsolin is an actin-binding protein that is a key regulator of actin filament assembly and disassembly. Gelsolin is one of the most potent members of the actin-severing gelsolin/villin superfamily, as it severs with nearly 100% efficiency.

Cellu ...

and p21-activated kinase 2 PAK2 are three other proteins that are myristoylated following cleavage by caspase 3

Caspase-3 is a caspase protein that interacts with caspase-8 and caspase-9. It is encoded by the ''CASP3'' gene. ''CASP3'' orthologs have been identified in numerous mammals for which complete genome data are available. Unique orthologs are als ...

, which leads to either the up-regulation or down-regulation of apoptosis.

Impact on human health

Cancer

''c-Src'' is a gene that codes for proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src, a protein important for normal mitotic cycling. It is phosphorylated and dephosphorylated to turn signaling on and off. Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src must be localized to theplasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

in order to phosphorylate other downstream targets; myristoylation is responsible for this membrane targeting event. Increased myristoylation of ''c-Src'' can lead to enhanced cell proliferation

Cell proliferation is the process by which ''a cell grows and divides to produce two daughter cells''. Cell proliferation leads to an exponential increase in cell number and is therefore a rapid mechanism of tissue growth. Cell proliferation ...

and be responsible for transforming normal cells into cancer cells. Activation of ''c-Src'' can lead to the so-called " hallmarks of cancer", among them upregulation of angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is the physiological process through which new blood vessels form from pre-existing vessels, formed in the earlier stage of vasculogenesis. Angiogenesis continues the growth of the vasculature mainly by processes of sprouting and ...

, proliferation, and invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory (country subdivision), territory controlled by another similar entity, ...

.

Viral infectivity

HIV-1

The subtypes of HIV include two main subtypes, known as HIV type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV type 2 (HIV-2). These subtypes have distinct genetic differences and are associated with different epidemiological patterns and clinical characteristics.

HIV-1 e ...

is a retrovirus

A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a DNA copy of its RNA genome into the DNA of a host cell that it invades, thus changing the genome of that cell. After invading a host cell's cytoplasm, the virus uses its own reverse transcriptase e ...

that relies on myristoylation of one of its structural proteins in order to successfully package its genome, assemble and mature into a new infectious particle. Viral matrix protein

Viral matrix proteins are structural proteins linking the viral envelope with the virus core. They play a crucial role in virus assembly, and interact with the RNP complex as well as with the viral membrane. They are found in many enveloped viru ...

, the ''N''-terminal–most domain of the gag polyprotein, is myristoylated. This myristoylation modification targets gag to the membrane of the host cell. Utilizing the myristoyl-electrostatic switch, including a basic patch on the matrix protein, gag can assemble at lipid raft

The cell membrane, plasma membranes of cells contain combinations of glycosphingolipids, cholesterol and protein Receptor (biochemistry), receptors organized in glycolipoprotein lipid microdomains termed lipid rafts. Their existence in cellular me ...

s at the plasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

for viral assembly, budding and further maturation. In order to prevent viral infectivity, myristoylation of the matrix protein could become a good drug target.

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic infections

Certain NMTs are therapeutic targets for development of drugs against bacterialinfection

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

s. Myristoylation has been shown to be necessary for the survival of a number of disease-causing fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

, among them '' C. albicans'' and '' C. neoformans''. In addition to prokaryotic

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' ...

bacteria, the NMTs of numerous disease-causing eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

organisms have been identified as drug target

A biological target is anything within a living organism to which some other entity (like an endogenous ligand or a drug) is directed and/or binds, resulting in a change in its behavior or function. Examples of common classes of biological targets ...

s as well. Proper NMT functioning in the protozoa

Protozoa (: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically ...

''Leishmania major

''Leishmania major'' is a species of parasite found in the genus ''Leishmania'', and is associated with the disease zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (also known as Aleppo boil, Baghdad boil, Bay sore, Biskra button, Chiclero ulcer, Delhi boil, Ka ...

'' and ''Leishmania donovani

''Leishmania donovani'' is a species of intracellular parasites belonging to the genus ''Leishmania'', a group of haemoflagellate kinetoplastids that cause the disease leishmaniasis. It is a human blood parasite responsible for visceral leishm ...

'' (leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is a wide array of clinical manifestations caused by protozoal parasites of the Trypanosomatida genus ''Leishmania''. It is generally spread through the bite of Phlebotominae, phlebotomine Sandfly, sandflies, ''Phlebotomus'' an ...

), ''Trypanosoma brucei

''Trypanosoma brucei'' is a species of parasitic Kinetoplastida, kinetoplastid belonging to the genus ''Trypanosoma'' that is present in sub-Saharan Africa. Unlike other protozoan parasites that normally infect blood and tissue cells, it is excl ...

'' ( African sleeping sickness), and '' P. falciparum'' (malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

) is necessary for survival of the parasites. Inhibitors of these organisms are under current investigation. A pyrazole

Pyrazole is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula . It is a heterocycle characterized as an azole with a 5-membered ring of three carbon atoms and two adjacent nitrogen atoms, which are in Arene substitution pattern, ortho-substi ...

sulfonamide

In organic chemistry, the sulfonamide functional group (also spelled sulphonamide) is an organosulfur group with the Chemical structure, structure . It consists of a sulfonyl group () connected to an amine group (). Relatively speaking this gro ...

inhibitor

Inhibitor or inhibition may refer to:

Biology

* Enzyme inhibitor, a substance that binds to an enzyme and decreases the enzyme's activity

* Reuptake inhibitor, a substance that increases neurotransmission by blocking the reuptake of a neurotransmi ...

has been identified that selectively binds ''T. brucei'', competing for the peptide binding site, thus inhibiting enzymatic activity and eliminating the parasite from the bloodstream of mice with African sleeping sickness.

Treatment

Inhibition of myristoylated proteins that are essential for the viral life cycle would inhibit viral propagation. Indeed, this has been shown with mammarenaviruses, including the hemorrhagic fever viruses such as lassa and junin, where the affected myristoylated proteins are Z matrix protein, which aids in viral assembly and budding, and the glycoprotein 1 (GP1), specifically the signal peptide of GP1. Inhibition of myristoylation in cells infected with mammarenaviruses, signaled Z protein and signal peptide of GP1 for degradation, which limits viral assembly, budding and propagation. Bothvaccinia

The vaccinia virus (VACV or VV) is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, which encodes approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the ...

and monkeypox

Mpox (, ; formerly known as monkeypox) is an infectious viral disease that can occur in humans and other animals. Symptoms include a rash that forms blisters and then crusts over, fever, and lymphadenopathy, swollen lymph nodes. The illness ...

viruses have four myristoylated proteins that can be targeted which would interrupt viral lifecycle, inhibition of myristoylation has been shown to completely inhibit viral propagation in combination therapies, L1R is an essential protein, for the life cycle, in both vaccinia and monkeypox viruses, and myristoylation inhibition in montherapy and combination resulted in complete inhibition.

See also

*Acylation

In chemistry, acylation is a broad class of chemical reactions in which an acyl group () is added to a substrate. The compound providing the acyl group is called the acylating agent. The substrate to be acylated and the product include the foll ...

*Prenylation

Prenylation (also known as isoprenylation or lipidation) is the addition of hydrophobic molecules to a protein or a biomolecule. It is usually assumed that prenyl groups (3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl) facilitate attachment to cell membranes, similar to ...

*Palmitoylation

In molecular biology, palmitoylation is the covalent attachment of fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, to cysteine (''S''-palmitoylation) and less frequently to serine and threonine (''O''-palmitoylation) residues of proteins, which are typic ...

* Palmitoleoylation

* Glycophosphatidylinositol

References

External links

The MYR Predictor

{{Protein posttranslational modification Post-translational modification Signal transduction