Miles Davis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

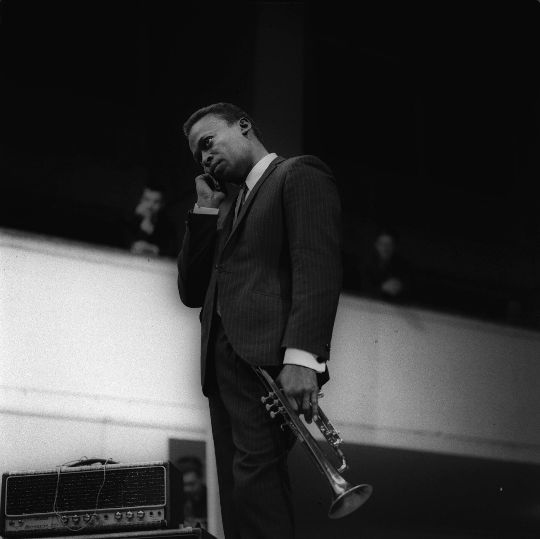

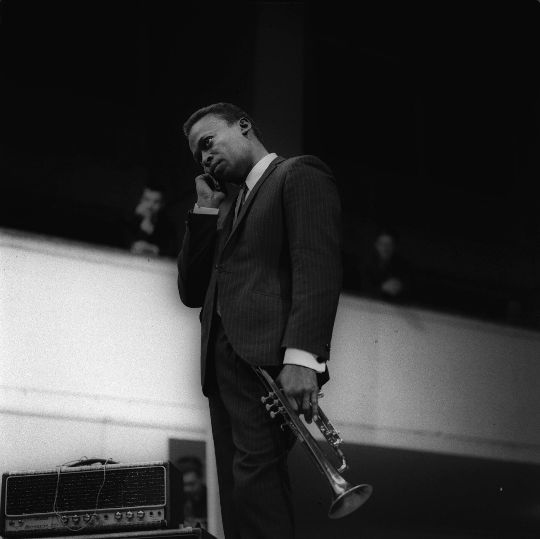

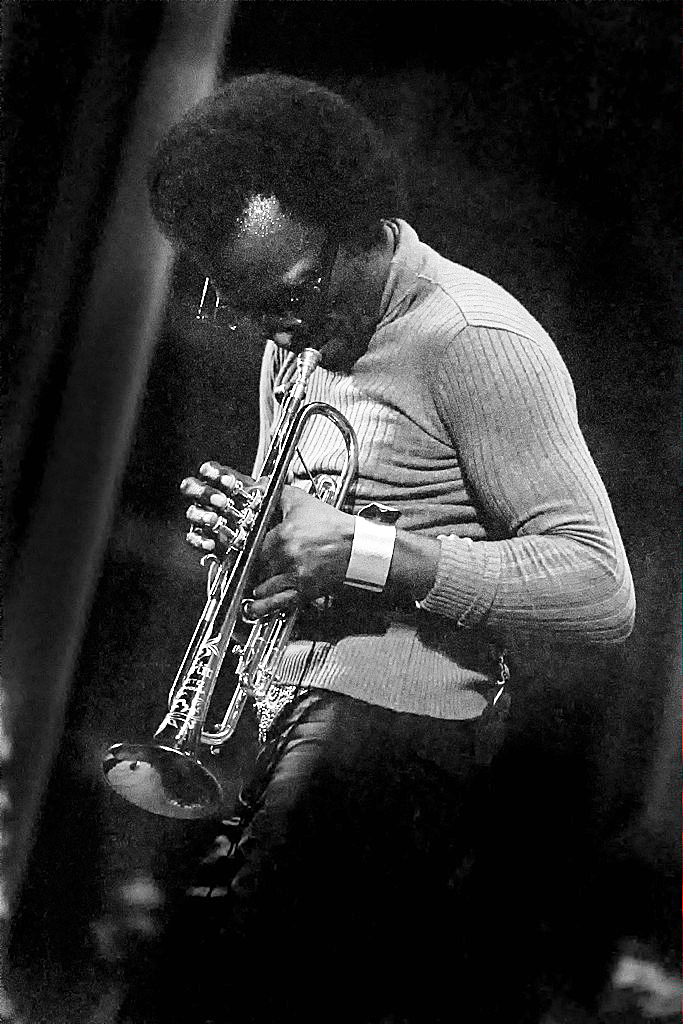

Miles Dewey Davis III (May 26, 1926September 28, 1991) was an American

In 1935, Davis received his first trumpet as a gift from John Eubanks, a friend of his father. He then took weekly lessons from "the biggest influence on my life", Elwood Buchanan, a teacher and musician who was a patient of his father. His mother wanted him to play the violin instead. Against the fashion of the time, Buchanan stressed the importance of playing without vibrato and encouraged him to use a clear, mid-range tone. Davis said that whenever he started playing with heavy vibrato, Buchanan slapped his knuckles. In later years Davis said, "I prefer a round sound with no attitude in it, like a round voice with not too much tremolo and not too much bass. Just right in the middle. If I can't get that sound I can't play anything." The family soon moved to 1701 Kansas Avenue in East St. Louis.

In his autobiography, Davis stated, "By the age of 12, music had become the most important thing in my life." On his thirteenth birthday his father bought him a new trumpet, and Davis began to play in local bands. He took additional trumpet lessons from Joseph Gustat, principal trumpeter of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. Davis would also play the trumpet in talent shows he and his siblings would put on.

In 1941, the 15-year-old attended East St. Louis Lincoln High School, where he joined the marching band directed by Buchanan and entered music competitions. Years later, Davis said that he was discriminated against in these competitions due to his race, but he added that these experiences made him a better musician. When a drummer asked him to play a certain passage of music, and he couldn't do it, he began to learn

In 1935, Davis received his first trumpet as a gift from John Eubanks, a friend of his father. He then took weekly lessons from "the biggest influence on my life", Elwood Buchanan, a teacher and musician who was a patient of his father. His mother wanted him to play the violin instead. Against the fashion of the time, Buchanan stressed the importance of playing without vibrato and encouraged him to use a clear, mid-range tone. Davis said that whenever he started playing with heavy vibrato, Buchanan slapped his knuckles. In later years Davis said, "I prefer a round sound with no attitude in it, like a round voice with not too much tremolo and not too much bass. Just right in the middle. If I can't get that sound I can't play anything." The family soon moved to 1701 Kansas Avenue in East St. Louis.

In his autobiography, Davis stated, "By the age of 12, music had become the most important thing in my life." On his thirteenth birthday his father bought him a new trumpet, and Davis began to play in local bands. He took additional trumpet lessons from Joseph Gustat, principal trumpeter of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. Davis would also play the trumpet in talent shows he and his siblings would put on.

In 1941, the 15-year-old attended East St. Louis Lincoln High School, where he joined the marching band directed by Buchanan and entered music competitions. Years later, Davis said that he was discriminated against in these competitions due to his race, but he added that these experiences made him a better musician. When a drummer asked him to play a certain passage of music, and he couldn't do it, he began to learn

Davis abandoned the bebop style and turned to the music of pianist

Davis abandoned the bebop style and turned to the music of pianist

Davis needed medical attention for hip pain, which had worsened since his Japanese tour during the previous year. He underwent hip replacement surgery in April 1965, with bone taken from his shin, but it failed. After his third month in the hospital, he discharged himself due to boredom and went home. He returned to the hospital in August after a fall required the insertion of a plastic hip joint. In November 1965, he had recovered enough to return to performing with his quintet, which included gigs at the Plugged Nickel in Chicago. Teo Macero returned as his record producer after their rift over ''Quiet Nights'' had healed.

In January 1966, Davis spent three months in the hospital with a liver infection. When he resumed touring, he performed more at colleges because he had grown tired of the typical jazz venues. Columbia president Clive Davis reported in 1966 his sales had declined to around 40,000–50,000 per album, compared to as many as 100,000 per release a few years before. Matters were not helped by the press reporting his apparent financial troubles and imminent demise. After his appearance at the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival, he returned to the studio with his quintet for a series of sessions. He started a relationship with actress Cicely Tyson, who helped him reduce his alcohol consumption.

Material from the 1966–1968 sessions was released on '' Miles Smiles'' (1966), '' Sorcerer'' (1967), '' Nefertiti'' (1967), '' Miles in the Sky'' (1968), and '' Filles de Kilimanjaro'' (1968). The quintet's approach to the new music became known as "time no changes"—which referred to Davis's decision to depart from chordal sequences and adopt a more open approach, with the rhythm section responding to the soloists' melodies. Through ''Nefertiti'' the studio recordings consisted primarily of originals composed by Shorter, with occasional compositions by the other sidemen. In 1967, the group began to play their concerts in continuous sets, each tune flowing into the next, with only the melody indicating any sort of change. His bands performed this way until his hiatus in 1975.

''Miles in the Sky'' and ''Filles de Kilimanjaro''—which tentatively introduced electric bass, electric piano, and electric guitar on some tracks—pointed the way to the fusion phase of Davis's career. He also began experimenting with more rock-oriented rhythms on these records. By the time the second half of ''Filles de Kilimanjaro'' was recorded, bassist Dave Holland and pianist Chick Corea had replaced Carter and Hancock. Davis soon took over the compositional duties of his sidemen.

Davis needed medical attention for hip pain, which had worsened since his Japanese tour during the previous year. He underwent hip replacement surgery in April 1965, with bone taken from his shin, but it failed. After his third month in the hospital, he discharged himself due to boredom and went home. He returned to the hospital in August after a fall required the insertion of a plastic hip joint. In November 1965, he had recovered enough to return to performing with his quintet, which included gigs at the Plugged Nickel in Chicago. Teo Macero returned as his record producer after their rift over ''Quiet Nights'' had healed.

In January 1966, Davis spent three months in the hospital with a liver infection. When he resumed touring, he performed more at colleges because he had grown tired of the typical jazz venues. Columbia president Clive Davis reported in 1966 his sales had declined to around 40,000–50,000 per album, compared to as many as 100,000 per release a few years before. Matters were not helped by the press reporting his apparent financial troubles and imminent demise. After his appearance at the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival, he returned to the studio with his quintet for a series of sessions. He started a relationship with actress Cicely Tyson, who helped him reduce his alcohol consumption.

Material from the 1966–1968 sessions was released on '' Miles Smiles'' (1966), '' Sorcerer'' (1967), '' Nefertiti'' (1967), '' Miles in the Sky'' (1968), and '' Filles de Kilimanjaro'' (1968). The quintet's approach to the new music became known as "time no changes"—which referred to Davis's decision to depart from chordal sequences and adopt a more open approach, with the rhythm section responding to the soloists' melodies. Through ''Nefertiti'' the studio recordings consisted primarily of originals composed by Shorter, with occasional compositions by the other sidemen. In 1967, the group began to play their concerts in continuous sets, each tune flowing into the next, with only the melody indicating any sort of change. His bands performed this way until his hiatus in 1975.

''Miles in the Sky'' and ''Filles de Kilimanjaro''—which tentatively introduced electric bass, electric piano, and electric guitar on some tracks—pointed the way to the fusion phase of Davis's career. He also began experimenting with more rock-oriented rhythms on these records. By the time the second half of ''Filles de Kilimanjaro'' was recorded, bassist Dave Holland and pianist Chick Corea had replaced Carter and Hancock. Davis soon took over the compositional duties of his sidemen.

For the double album '' Bitches Brew'' (1970), he hired Jack DeJohnette, Harvey Brooks, and Bennie Maupin. The album contained long compositions, some over twenty minutes, that more often than not, were constructed from several takes by Macero and Davis via splicing and tape loops amid epochal advances in multitrack recording technologies. ''Bitches Brew'' peaked at No. 35 on the ''Billboard'' Album chart. In 1976, it was certified gold for selling over 500,000 records. By 2003, it had sold one million copies.

In March 1970, Davis began to perform as the opening act for rock bands, allowing Columbia to market ''Bitches Brew'' to a larger audience. He shared a

For the double album '' Bitches Brew'' (1970), he hired Jack DeJohnette, Harvey Brooks, and Bennie Maupin. The album contained long compositions, some over twenty minutes, that more often than not, were constructed from several takes by Macero and Davis via splicing and tape loops amid epochal advances in multitrack recording technologies. ''Bitches Brew'' peaked at No. 35 on the ''Billboard'' Album chart. In 1976, it was certified gold for selling over 500,000 records. By 2003, it had sold one million copies.

In March 1970, Davis began to perform as the opening act for rock bands, allowing Columbia to market ''Bitches Brew'' to a larger audience. He shared a  In 1972, composer-arranger Paul Buckmaster introduced Davis to the music of avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, leading to a period of creative exploration. Biographer J. K. Chambers wrote, "The effect of Davis' study of Stockhausen could not be repressed for long ... Davis' own 'space music' shows Stockhausen's influence compositionally." His recordings and performances during this period were described as "space music" by fans, Feather, and Buckmaster, who described it as "a lot of mood changes—heavy, dark, intense—definitely space music". The studio album '' On the Corner'' (1972) blended the influence of Stockhausen and Buckmaster with funk elements. Davis invited Buckmaster to New York City to oversee the writing and recording of the album with Macero. The album reached No. 1 on the ''Billboard'' jazz chart but peaked at No. 156 on the more heterogeneous Top 200 Albums chart. Davis felt that Columbia marketed it to the wrong audience. "The music was meant to be heard by young black people, but they just treated it like any other jazz album and advertised it that way, pushed it on the jazz radio stations. Young black kids don't listen to those stations; they listen to R&B stations and some rock stations." In October 1972, he broke his ankles in a car crash. He took painkillers and cocaine to cope with the pain. Looking back at his career after the incident, he wrote, "Everything started to blur."

After recording ''On the Corner'', he assembled a group with Henderson, Mtume, Carlos Garnett, guitarist Reggie Lucas, organist Lonnie Liston Smith, tabla player Badal Roy, sitarist Khalil Balakrishna, and drummer Al Foster. In striking contrast to that of his previous lineups, the music emphasized rhythmic density and shifting textures instead of solos. This group was recorded live in 1972 for '' In Concert'', but Davis found it unsatisfactory, leading him to drop the tabla and sitar and play organ himself. He also added guitarist Pete Cosey. The compilation studio album '' Big Fun'' contains four long improvisations recorded between 1969 and 1972.

Studio sessions throughout 1973 and 1974 led to '' Get Up with It'', an album which included four long pieces alongside four shorter recordings from 1970 and 1972. The track "He Loved Him Madly", a thirty-minute tribute to the recently deceased Duke Ellington, influenced

In 1972, composer-arranger Paul Buckmaster introduced Davis to the music of avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, leading to a period of creative exploration. Biographer J. K. Chambers wrote, "The effect of Davis' study of Stockhausen could not be repressed for long ... Davis' own 'space music' shows Stockhausen's influence compositionally." His recordings and performances during this period were described as "space music" by fans, Feather, and Buckmaster, who described it as "a lot of mood changes—heavy, dark, intense—definitely space music". The studio album '' On the Corner'' (1972) blended the influence of Stockhausen and Buckmaster with funk elements. Davis invited Buckmaster to New York City to oversee the writing and recording of the album with Macero. The album reached No. 1 on the ''Billboard'' jazz chart but peaked at No. 156 on the more heterogeneous Top 200 Albums chart. Davis felt that Columbia marketed it to the wrong audience. "The music was meant to be heard by young black people, but they just treated it like any other jazz album and advertised it that way, pushed it on the jazz radio stations. Young black kids don't listen to those stations; they listen to R&B stations and some rock stations." In October 1972, he broke his ankles in a car crash. He took painkillers and cocaine to cope with the pain. Looking back at his career after the incident, he wrote, "Everything started to blur."

After recording ''On the Corner'', he assembled a group with Henderson, Mtume, Carlos Garnett, guitarist Reggie Lucas, organist Lonnie Liston Smith, tabla player Badal Roy, sitarist Khalil Balakrishna, and drummer Al Foster. In striking contrast to that of his previous lineups, the music emphasized rhythmic density and shifting textures instead of solos. This group was recorded live in 1972 for '' In Concert'', but Davis found it unsatisfactory, leading him to drop the tabla and sitar and play organ himself. He also added guitarist Pete Cosey. The compilation studio album '' Big Fun'' contains four long improvisations recorded between 1969 and 1972.

Studio sessions throughout 1973 and 1974 led to '' Get Up with It'', an album which included four long pieces alongside four shorter recordings from 1970 and 1972. The track "He Loved Him Madly", a thirty-minute tribute to the recently deceased Duke Ellington, influenced

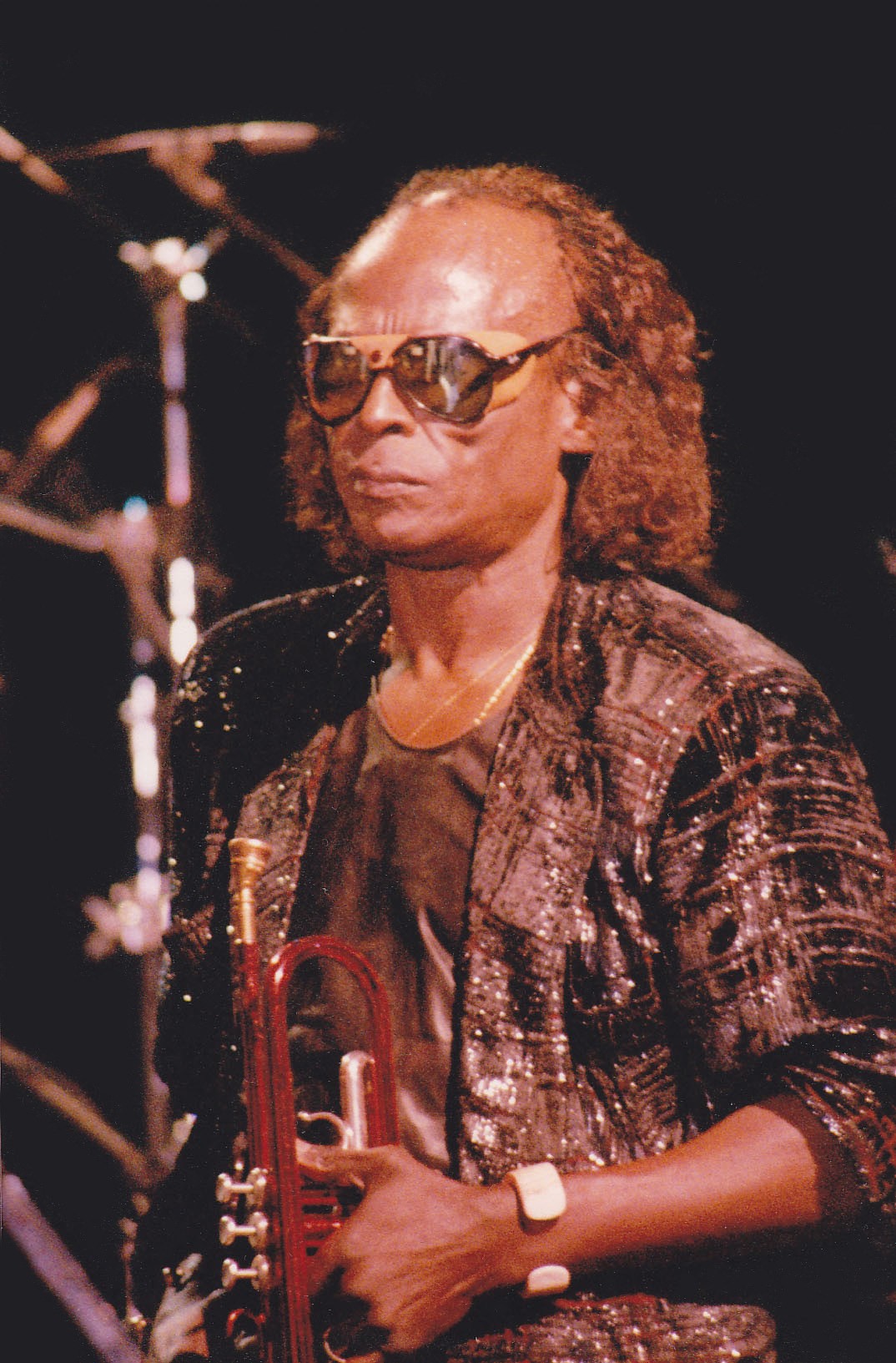

In January 1982, while Tyson was working in Africa, Davis "went a little wild" with alcohol and suffered a stroke that temporarily paralyzed his right hand. Tyson returned home and cared for him. After three months of treatment with a Chinese acupuncturist, he was able to play the trumpet again. He listened to his doctor's warnings and gave up alcohol and drugs. He credited Tyson with helping his recovery, which involved exercise, piano playing, and visits to spas. She encouraged him to draw, which he pursued for the rest of his life. Takao Ogawa, a Japanese jazz journalist who befriended Davis during this period, took pictures of his drawings and put them in his book along with the interviews of Davis at his apartment in New York. Davis told Ogawa: "I'm interested in line and color, line is like phrase and coating colors is like code. When I see good paintings, I hear good music. That is why my paintings are the same as my music. They are different than any paintings."

Davis resumed touring in May 1982 with a lineup that included percussionist Mino Cinelu and guitarist John Scofield, with whom he worked closely on the album '' Star People'' (1983). In mid-1983, he worked on the tracks for '' Decoy'', an album mixing soul music and

In January 1982, while Tyson was working in Africa, Davis "went a little wild" with alcohol and suffered a stroke that temporarily paralyzed his right hand. Tyson returned home and cared for him. After three months of treatment with a Chinese acupuncturist, he was able to play the trumpet again. He listened to his doctor's warnings and gave up alcohol and drugs. He credited Tyson with helping his recovery, which involved exercise, piano playing, and visits to spas. She encouraged him to draw, which he pursued for the rest of his life. Takao Ogawa, a Japanese jazz journalist who befriended Davis during this period, took pictures of his drawings and put them in his book along with the interviews of Davis at his apartment in New York. Davis told Ogawa: "I'm interested in line and color, line is like phrase and coating colors is like code. When I see good paintings, I hear good music. That is why my paintings are the same as my music. They are different than any paintings."

Davis resumed touring in May 1982 with a lineup that included percussionist Mino Cinelu and guitarist John Scofield, with whom he worked closely on the album '' Star People'' (1983). In mid-1983, he worked on the tracks for '' Decoy'', an album mixing soul music and

After taking part in the recording of the 1985 protest song " Sun City" as a member of Artists United Against Apartheid, Davis appeared on the instrumental "Don't Stop Me Now" by Toto for their album ''

After taking part in the recording of the 1985 protest song " Sun City" as a member of Artists United Against Apartheid, Davis appeared on the instrumental "Don't Stop Me Now" by Toto for their album '' Davis followed ''Tutu'' with '' Amandla'' (1989) and soundtracks to four films: '' Street Smart'', '' Siesta'', '' The Hot Spot'', and '' Dingo.'' His last albums were released posthumously: the hip hop-influenced ''

Davis followed ''Tutu'' with '' Amandla'' (1989) and soundtracks to four films: '' Street Smart'', '' Siesta'', '' The Hot Spot'', and '' Dingo.'' His last albums were released posthumously: the hip hop-influenced ''

On October 10, 1969, Davis was shot at five times while in his Ferrari with Marguerite Eskridge, one of his lovers. One bullet grazed his hip; Eskridge was unharmed.

Davis later wrote that the incident arose from a dispute among nightclub promoters.

In 1970, Marguerite gave birth to their son Erin. By 1979, Davis rekindled his relationship with actress Cicely Tyson, who helped him to overcome his cocaine addiction and regain his enthusiasm for music. The two married in November 1981, but their tumultuous marriage ended with Tyson filing for divorce in 1988, which was finalized in 1989.

In 1984, Davis met 34-year-old sculptor Jo Gelbard. Gelbard would teach Davis how to paint; the two were frequent collaborators and were soon romantically involved. By 1985, Davis was diabetic and required daily injections of insulin. Davis became increasingly aggressive in his final year due in part to the medication he was taking, and his aggression manifested as violence towards Gelbard.

On October 10, 1969, Davis was shot at five times while in his Ferrari with Marguerite Eskridge, one of his lovers. One bullet grazed his hip; Eskridge was unharmed.

Davis later wrote that the incident arose from a dispute among nightclub promoters.

In 1970, Marguerite gave birth to their son Erin. By 1979, Davis rekindled his relationship with actress Cicely Tyson, who helped him to overcome his cocaine addiction and regain his enthusiasm for music. The two married in November 1981, but their tumultuous marriage ended with Tyson filing for divorce in 1988, which was finalized in 1989.

In 1984, Davis met 34-year-old sculptor Jo Gelbard. Gelbard would teach Davis how to paint; the two were frequent collaborators and were soon romantically involved. By 1985, Davis was diabetic and required daily injections of insulin. Davis became increasingly aggressive in his final year due in part to the medication he was taking, and his aggression manifested as violence towards Gelbard.

In early September 1991, Davis checked into St. John's Hospital near his home in Santa Monica, California, for routine tests. Doctors suggested he have a tracheal tube implanted to relieve his breathing after repeated bouts of bronchial pneumonia. The suggestion provoked an outburst from Davis that led to an intracerebral hemorrhage followed by a coma. According to Jo Gelbard, on September 26, Davis painted his final painting – and that painting, composed of dark, ghostly figures dripping blood "was full of his imminent demise". After several days on life support, his machine was turned off and he died on September 28, 1991, in the arms of Gelbard. He was 65 years old. His death was attributed to the combined effects of a stroke, pneumonia, and respiratory failure. According to Troupe, Davis was taking azidothymidine (AZT), a type of

In early September 1991, Davis checked into St. John's Hospital near his home in Santa Monica, California, for routine tests. Doctors suggested he have a tracheal tube implanted to relieve his breathing after repeated bouts of bronchial pneumonia. The suggestion provoked an outburst from Davis that led to an intracerebral hemorrhage followed by a coma. According to Jo Gelbard, on September 26, Davis painted his final painting – and that painting, composed of dark, ghostly figures dripping blood "was full of his imminent demise". After several days on life support, his machine was turned off and he died on September 28, 1991, in the arms of Gelbard. He was 65 years old. His death was attributed to the combined effects of a stroke, pneumonia, and respiratory failure. According to Troupe, Davis was taking azidothymidine (AZT), a type of

Miles Davis is considered one of the most innovative, influential, and respected figures in the history of music. ''

Miles Davis is considered one of the most innovative, influential, and respected figures in the history of music. ''

jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots are in blues, ragtime, European harmony, African rhythmic rituals, spirituals, h ...

trumpeter, bandleader, and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the history of jazz and 20th-century music. Davis adopted a variety of musical directions in a roughly five-decade career that kept him at the forefront of many major stylistic developments in jazz.

Born into an upper-middle-class family in Alton, Illinois

Alton ( ) is a city on the Mississippi River in Madison County, Illinois, United States, about north of St. Louis, Missouri. The population was 25,676 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is a part of the River Bend (Illinois), Riv ...

, and raised in East St. Louis, Davis started on the trumpet in his early teens. He left to study at Juilliard in New York City, before dropping out and making his professional debut as a member of saxophonist Charlie Parker

Charles Parker Jr. (August 29, 1920 – March 12, 1955), nicknamed "Bird" or "Yardbird", was an American jazz Saxophone, saxophonist, bandleader, and composer. Parker was a highly influential soloist and leading figure in the development of beb ...

's bebop

Bebop or bop is a style of jazz developed in the early to mid-1940s in the United States. The style features compositions characterized by a fast tempo (usually exceeding 200 bpm), complex chord progressions with rapid chord changes and numerou ...

quintet from 1944 to 1948. Shortly after, he recorded the '' Birth of the Cool'' sessions for Capitol Records

Capitol Records, LLC (known legally as Capitol Records, Inc. until 2007), and simply known as Capitol, is an American record label owned by Universal Music Group through its Capitol Music Group imprint. It was founded as the first West Coast-base ...

, which were instrumental to the development of cool jazz. In the early 1950s, while addicted to heroin, Davis recorded some of the earliest hard bop music under Prestige Records. After a widely acclaimed comeback performance at the Newport Jazz Festival, he signed a long-term contract with Columbia Records

Columbia Records is an American reco ...

, and recorded the album '' 'Round About Midnight'' in 1955. It was his first work with saxophonist John Coltrane

John William Coltrane (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967) was an American jazz saxophonist, bandleader and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the Jazz#Post-war jazz, history of jazz and 20th-century musi ...

and bassist Paul Chambers

Paul Laurence Dunbar Chambers Jr. (April 22, 1935 – January 4, 1969) was an American jazz double bassist. A fixture of rhythm sections during the 1950s and 1960s, he has become one of the most widely-known jazz bassists of the hard bop er ...

, key members of the sextet he led into the early 1960s. During this period, he alternated between orchestral jazz collaborations with arranger Gil Evans, such as the Spanish music–influenced '' Sketches of Spain'' (1960), and band recordings, such as '' Milestones'' (1958) and '' Kind of Blue'' (1959). The latter recording remains one of the most popular jazz albums of all time, having sold over five million copies in the U.S.

Davis made several lineup changes while recording '' Someday My Prince Will Come'' (1961), his 1961 Blackhawk concerts, and '' Seven Steps to Heaven'' (1963), another commercial success that introduced bassist Ron Carter, pianist Herbie Hancock

Herbert Jeffrey Hancock (born April 12, 1940) is an American jazz musician, bandleader, and composer. He started his career with trumpeter Donald Byrd's group. Hancock soon joined the Miles Davis Quintet, where he helped to redefine the role of ...

, and drummer Tony Williams. After adding saxophonist Wayne Shorter to his new quintet in 1964, Davis led them on a series of more abstract recordings often composed by the band members, helping pioneer the post-bop

Post-bop is a jazz term with several possible definitions and usages.Yudkin, Jeremy (2007), p. 125 It has been variously defined as a musical period, a musical genre, a musical style, and a body of music, sometimes in different chronological perio ...

genre with albums such as '' E.S.P.'' (1965) and '' Miles Smiles'' (1967), before transitioning into his electric period. During the 1970s, he experimented with rock, funk, African rhythms, emerging electronic music technology, and an ever-changing lineup of musicians, including keyboardist Joe Zawinul, drummer Al Foster, bassist Michael Henderson, and guitarist John McLaughlin. This period, beginning with Davis's 1969 studio album '' In a Silent Way'' and concluding with the 1975 concert recording '' Agharta'', was the most controversial in his career, alienating and challenging many in jazz. His million-selling 1970 record '' Bitches Brew'' helped spark a resurgence in the genre's commercial popularity with jazz fusion as the decade progressed.

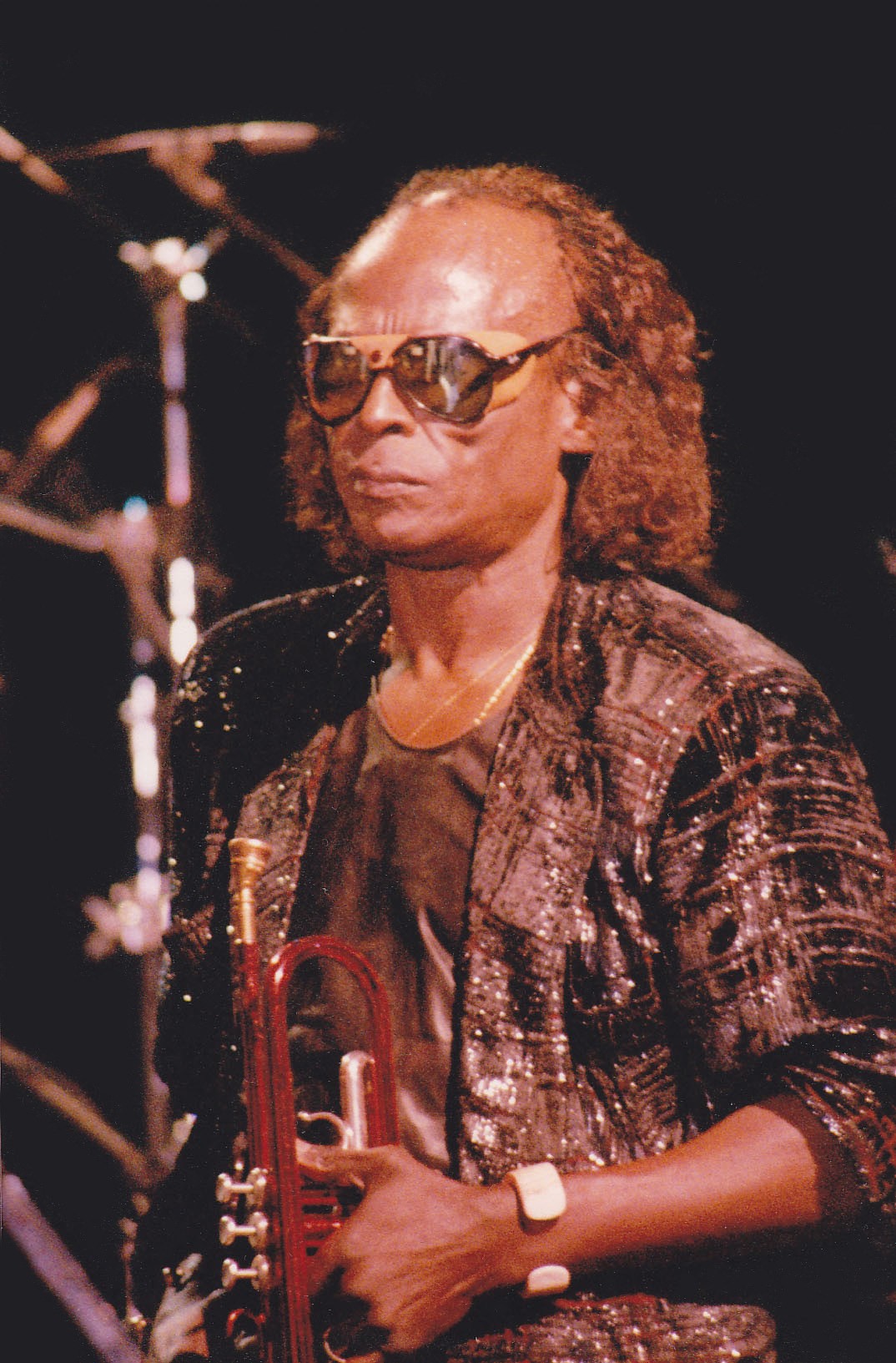

After a five-year retirement due to poor health, Davis resumed his career in the 1980s, employing younger musicians and pop sounds on albums such as '' The Man with the Horn'' (1981), '' You're Under Arrest'' (1985) and '' Tutu'' (1986). Critics were often unreceptive but the decade garnered Davis his highest level of commercial recognition. He performed sold-out concerts worldwide, while branching out into visual arts, film, and television work, before his death in 1991 from the combined effects of a stroke, pneumonia and respiratory failure

Respiratory failure results from inadequate gas exchange by the respiratory system, meaning that the arterial oxygen, carbon dioxide, or both cannot be kept at normal levels. A drop in the oxygen carried in the blood is known as hypoxemia; a r ...

. In 2006, Davis was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which recognized him as "one of the key figures in the history of jazz". ''Rolling Stone

''Rolling Stone'' is an American monthly magazine that focuses on music, politics, and popular culture. It was founded in San Francisco, California, in 1967 by Jann Wenner and the music critic Ralph J. Gleason.

The magazine was first known fo ...

'' described him as "the most revered jazz trumpeter of all time, not to mention one of the most important musicians of the 20th century," while Gerald Early called him inarguably one of the most influential and innovative musicians of that period.

Early life

Davis was born on May 26, 1926, to an affluent African-American family in Alton, Illinois, north of St. Louis. He had an older sister, Dorothy Mae (1925–1996) and a younger brother, Vernon (1929–1999). His mother, Cleota Mae Henry ofArkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

, was a music teacher and violinist, and his father, Miles Dewey Davis Jr., also of Arkansas, was a dentist. They owned a estate near Pine Bluff, Arkansas, with a profitable pig farm. In Pine Bluff, he and his siblings fished, hunted, and rode horses. Davis's grandparents were the owners of an Arkansas farm where he would spend many summers.

In 1927, the family moved to East St. Louis, Illinois. They lived on the second floor of a commercial building behind a dental office in a predominantly white neighborhood. Davis's father would soon become distant to his children as the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank an ...

caused him to become increasingly consumed by his job, typically working six days a week. From 1932 to 1934, Davis attended John Robinson Elementary School, an all-black school, then Crispus Attucks, where he performed well in mathematics, music, and sports. Davis had previously attended Catholic school. At an early age he liked music, especially blues, big bands, and gospel.

In 1935, Davis received his first trumpet as a gift from John Eubanks, a friend of his father. He then took weekly lessons from "the biggest influence on my life", Elwood Buchanan, a teacher and musician who was a patient of his father. His mother wanted him to play the violin instead. Against the fashion of the time, Buchanan stressed the importance of playing without vibrato and encouraged him to use a clear, mid-range tone. Davis said that whenever he started playing with heavy vibrato, Buchanan slapped his knuckles. In later years Davis said, "I prefer a round sound with no attitude in it, like a round voice with not too much tremolo and not too much bass. Just right in the middle. If I can't get that sound I can't play anything." The family soon moved to 1701 Kansas Avenue in East St. Louis.

In his autobiography, Davis stated, "By the age of 12, music had become the most important thing in my life." On his thirteenth birthday his father bought him a new trumpet, and Davis began to play in local bands. He took additional trumpet lessons from Joseph Gustat, principal trumpeter of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. Davis would also play the trumpet in talent shows he and his siblings would put on.

In 1941, the 15-year-old attended East St. Louis Lincoln High School, where he joined the marching band directed by Buchanan and entered music competitions. Years later, Davis said that he was discriminated against in these competitions due to his race, but he added that these experiences made him a better musician. When a drummer asked him to play a certain passage of music, and he couldn't do it, he began to learn

In 1935, Davis received his first trumpet as a gift from John Eubanks, a friend of his father. He then took weekly lessons from "the biggest influence on my life", Elwood Buchanan, a teacher and musician who was a patient of his father. His mother wanted him to play the violin instead. Against the fashion of the time, Buchanan stressed the importance of playing without vibrato and encouraged him to use a clear, mid-range tone. Davis said that whenever he started playing with heavy vibrato, Buchanan slapped his knuckles. In later years Davis said, "I prefer a round sound with no attitude in it, like a round voice with not too much tremolo and not too much bass. Just right in the middle. If I can't get that sound I can't play anything." The family soon moved to 1701 Kansas Avenue in East St. Louis.

In his autobiography, Davis stated, "By the age of 12, music had become the most important thing in my life." On his thirteenth birthday his father bought him a new trumpet, and Davis began to play in local bands. He took additional trumpet lessons from Joseph Gustat, principal trumpeter of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. Davis would also play the trumpet in talent shows he and his siblings would put on.

In 1941, the 15-year-old attended East St. Louis Lincoln High School, where he joined the marching band directed by Buchanan and entered music competitions. Years later, Davis said that he was discriminated against in these competitions due to his race, but he added that these experiences made him a better musician. When a drummer asked him to play a certain passage of music, and he couldn't do it, he began to learn music theory

Music theory is the study of theoretical frameworks for understanding the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory": The first is the "Elements of music, ...

. "I went and got everything, every book I could get to learn about theory." At Lincoln, Davis met his first girlfriend, Irene Birth (later Cawthon). He had a band that performed at the Elks Club. Part of his earnings paid for his sister's education at Fisk University. Davis befriended trumpeter Clark Terry, who suggested he play without vibrato, and performed with him for several years.

With encouragement from his teacher and girlfriend, Davis filled a vacant spot in the Rhumboogie Orchestra, also known as the Blue Devils, led by Eddie Randle. He became the band's musical director, which involved hiring musicians and scheduling rehearsal. Years later, Davis considered this job one of the most important of his career. Sonny Stitt

Sonny Stitt (born Edward Hammond Boatner Jr.; February 2, 1924 – July 22, 1982) was an American jazz saxophonist of the bebop/hard bop idiom. Known for his warm tone, he was one of the best-documented saxophonists of his era, recording over ...

tried to persuade him to join the Tiny Bradshaw band, which was passing through town, but his mother insisted he finish high school before going on tour. He said later, "I didn't talk to her for two weeks. And I didn't go with the band either." In January 1944, Davis finished high school and graduated in absentia in June. During the next month, his girlfriend gave birth to a daughter, Cheryl.

In July 1944, Billy Eckstine visited St. Louis with a band that included Art Blakey, Dizzy Gillespie

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie ( ; October 21, 1917 – January 6, 1993) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer, educator and singer. He was a trumpet virtuoso and improvisation, improviser, building on the virtuosic style of Roy El ...

, and Charlie Parker

Charles Parker Jr. (August 29, 1920 – March 12, 1955), nicknamed "Bird" or "Yardbird", was an American jazz Saxophone, saxophonist, bandleader, and composer. Parker was a highly influential soloist and leading figure in the development of beb ...

. Trumpeter Buddy Anderson was too sick to perform, so Davis was invited to join. He played with the band for two weeks at Club Riviera. After playing with these musicians, he was certain he should move to New York City, "where the action was". His mother wanted him to go to Fisk University, like his sister, and study piano or violin. Davis had other interests.

Career

1944–1948: New York City and the bebop years

In September 1944, Davis accepted his father's idea of studying at the Juilliard School of Music in New York City. After passing the audition, he attended classes in music theory, piano and dictation. Davis often skipped his classes. Much of Davis's time was spent in clubs seeking his idol, Charlie Parker. According to Davis,Coleman Hawkins

Coleman Randolph Hawkins (November 21, 1904 – May 19, 1969), nicknamed "Hawk" and sometimes "Bean", was an American jazz tenor saxophonist.Yanow, Scot"Coleman Hawkins: Artist Biography" AllMusic. Retrieved December 27, 2013. One of the first ...

told him "finish your studies at Juilliard and forget Bird arker. After finding Parker, he joined a cadre of regulars at Minton's and Monroe's in Harlem who held jam sessions every night. The other regulars included J. J. Johnson, Kenny Clarke, Thelonious Monk, Fats Navarro, and Freddie Webster. Davis reunited with Irene and their daughter Cheryl when they moved to New York City. Parker became a roommate. Around this time Davis was paid an allowance of $40 ().

In mid-1945, Davis failed to register for the year's autumn term at Juilliard and dropped out after three semesters because he wanted to perform full-time. Years later he criticized Juilliard for concentrating too much on classical European and "white" repertoire, but he praised the school for teaching him music theory and improving his trumpet technique.

Davis began performing at clubs on 52nd Street with Coleman Hawkins and Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis. He recorded for the first time on April 24, 1945, when he entered the studio as a sideman for Herbie Fields's band. During the next year, he recorded as a leader for the first time with the Miles Davis Sextet plus Earl Coleman and Ann Baker, one of the few times he accompanied a singer.

In 1945, Davis replaced Dizzy Gillespie in Charlie Parker's quintet. On November 26, he participated in several recording sessions as part of Parker's group Reboppers that also involved Gillespie and Max Roach, displaying hints of the style he would become known for. On Parker's tune " Now's the Time", Davis played a solo that anticipated cool jazz. He next joined a big band led by Benny Carter, performing in St. Louis and remaining with the band in California. He again played with Parker and Gillespie. In Los Angeles, Parker had a nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

that put him in the hospital for several months. In March 1946, Davis played in studio sessions with Parker and began a collaboration with bassist Charles Mingus that summer. Cawthon gave birth to Davis's second child, Gregory, in East St. Louis before reuniting with Davis in New York City the following year. Davis noted that by this time, "I was still so much into the music that I was even ignoring Irene." He had also turned to alcohol and cocaine.

Davis was a member of Billy Eckstine's big band in 1946 and Gillespie's in 1947. He joined a quintet led by Parker that also included Max Roach. Together they performed live with Duke Jordan and Tommy Potter for much of the year, including several studio sessions. In one session that May, Davis wrote the tune "Cheryl", for his daughter. Davis's first session as a leader followed in August 1947, playing as the Miles Davis All Stars that included Parker, pianist John Lewis, and bassist Nelson Boyd; they recorded "Milestones", "Half Nelson", and "Sippin' at Bells". After touring Chicago and Detroit with Parker's quintet, Davis returned to New York City in March 1948 and joined the Jazz at the Philharmonic tour, which included a stop in St. Louis on April 30.

1948–1950: Miles Davis Nonet and ''Birth of the Cool''

In August 1948, Davis declined an offer to joinDuke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American Jazz piano, jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous Big band, jazz orchestra from 1924 through the rest of his life.

Born and raised in Washington, D ...

's orchestra as he had entered rehearsals with a nine-piece band featuring baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan and arrangements by Gil Evans, taking an active role on what soon became his own project. Evans' Manhattan apartment had become the meeting place for several young musicians and composers such as Davis, Roach, Lewis, and Mulligan who were unhappy with the increasingly virtuoso instrumental techniques that dominated bebop. These gatherings led to the formation of the Miles Davis Nonet, which included atypical modern jazz instruments such as French horn and tuba, leading to a thickly textured, almost orchestral sound. The intent was to imitate the human voice through carefully arranged compositions and a relaxed, melodic approach to improvisation. In September, the band completed their sole engagement as the opening band for Count Basie

William James "Count" Basie (; August 21, 1904 – April 26, 1984) was an American jazz pianist, organist, bandleader, and composer. In 1935, he formed the Count Basie Orchestra, and in 1936 took them to Chicago for a long engagement and the ...

at the Royal Roost for two weeks. Davis had to persuade the venue's manager to write the sign "Miles Davis Nonet. Arrangements by Gil Evans, John Lewis and Gerry Mulligan". Davis returned to Parker's quintet, but relationships within the quintet were growing tense mainly due to Parker's erratic behavior caused by his drug addiction. Early in his time with Parker, Davis abstained from drugs, chose a vegetarian diet, and spoke of the benefits of water and juice.

In December 1948, Davis quit, saying he was not being paid. His departure began a period when he worked mainly as a freelancer and sideman. His nonet remained active until the end of 1949. After signing a contract with Capitol Records

Capitol Records, LLC (known legally as Capitol Records, Inc. until 2007), and simply known as Capitol, is an American record label owned by Universal Music Group through its Capitol Music Group imprint. It was founded as the first West Coast-base ...

, they recorded sessions in January and April 1949, which sold little but influenced the "cool" or "west coast" style of jazz. The lineup changed throughout the year and included tuba player Bill Barber, alto saxophonist Lee Konitz, pianist Al Haig, trombone players Mike Zwerin with Kai Winding, French horn players Junior Collins with Sandy Siegelstein and Gunther Schuller, and bassists Al McKibbon and Joe Shulman. One track featured singer Kenny Hagood. The presence of white musicians in the group angered some black players, many of whom were unemployed at the time, yet Davis rebuffed their criticisms. Recording sessions with the nonet for Capitol continued until April 1950. The Nonet recorded a dozen tracks which were released as singles and subsequently compiled on the 1957 album '' Birth of the Cool''.

In May 1949, Davis performed with the Tadd Dameron

Tadley Ewing Peake Dameron (February 21, 1917 – March 8, 1965) was an American jazz composer, arranger, and pianist.

Biography

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Dameron was the most influential arranger of the bebop era, but also wrote charts for swi ...

Quintet with Kenny Clarke and James Moody at the Paris International Jazz Festival. On his first trip abroad Davis took a strong liking to Paris and its cultural environment, where he felt black jazz musicians and people of color in general were better respected than in the U.S. The trip, he said, "changed the way I looked at things forever". He began an affair with singer and actress Juliette Gréco.

1949–1955: Signing with Prestige, heroin addiction, and hard bop

After returning from Paris in mid-1949, he became depressed and found little work except a short engagement with Bud Powell in October and guest spots in New York City, Chicago, and Detroit until January 1950. He was falling behind in hotel rent and attempts were made to repossess his car. His heroin use became an expensive addiction, and Davis, not yet 24 years old, "lost my sense of discipline, lost my sense of control over my life, and started to drift". In August 1950, Cawthon gave birth to Davis's second son, Miles IV. Davis befriended boxer Johnny Bratton which began his interest in the sport. Davis left Cawthon and his three children in New York City in the hands of one his friends, jazz singer Betty Carter. He toured with Eckstine andBillie Holiday

Billie Holiday (born Eleanora Fagan; April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959) was an American jazz and swing music singer. Nicknamed "Lady Day" by her friend and music partner, Lester Young, Holiday made significant contributions to jazz music and pop ...

and was arrested for heroin possession in Los Angeles. The story was reported in ''DownBeat

''DownBeat'' (styled in all caps) is an American music magazine devoted to "jazz, blues and beyond", the last word indicating its expansion beyond the jazz realm that it covered exclusively in previous years. The publication was established in 1 ...

'' magazine, which led to a further reduction in work, though he was acquitted weeks later. By the 1950s, Davis had become more skilled and was experimenting with the middle register of the trumpet alongside harmonies and rhythms.

In January 1951, Davis's fortunes improved when he signed a one-year contract with Prestige after owner Bob Weinstock became a fan of the nonet. Davis chose Lewis, trombonist Bennie Green, bassist Percy Heath, saxophonist Sonny Rollins, and drummer Roy Haynes; they recorded what became part of '' Miles Davis and Horns'' (1956). Davis was hired for other studio dates in 1951 and began to transcribe scores for record labels to fund his heroin addiction. His second session for Prestige was released on '' The New Sounds'' (1951), '' Dig'' (1956), and '' Conception'' (1956).

Davis supported his heroin habit by playing music and by living the life of a hustler, exploiting prostitutes, and receiving money from friends. By 1953, his addiction began to impair his playing. His drug habit became public in a ''DownBeat'' interview with Cab Calloway, whom he never forgave as it brought him "all pain and suffering". He returned to St. Louis and stayed with his father for several months. After a brief period with Roach and Mingus in September 1953, he returned to his father's home, where he concentrated on addressing his addiction.

Davis lived in Detroit for about six months, avoiding New York City, where it was easy to get drugs. Though he used heroin, he was still able to perform locally with Elvin Jones

Elvin Ray Jones (September 9, 1927 – May 18, 2004) was an American jazz drummer of the post-bop era. Most famously a member of John Coltrane's quartet, with whom he recorded from late 1960 to late 1965, Jones appeared on such albums as ''My Fa ...

and Tommy Flanagan as part of Billy Mitchell's house band at the Blue Bird club. He was also "pimping a little". However, he was able to end his addiction, and, in February 1954, Davis returned to New York City, feeling good "for the first time in a long time", mentally and physically stronger, and joined a gym. He informed Weinstock and Blue Note that he was ready to record with a quintet, which he was granted. He considered the albums that resulted from these and earlier sessions – '' Miles Davis Quartet'' and '' Miles Davis Volume 2'' – "very important" because he felt his performances were particularly strong. He was paid roughly $750 () for each album and refused to give away his publishing rights.

Davis abandoned the bebop style and turned to the music of pianist

Davis abandoned the bebop style and turned to the music of pianist Ahmad Jamal

Ahmad Jamal (born Frederick Russell Jones; July 2, 1930 – April 16, 2023) was an American jazz pianist, composer, bandleader, and educator. For six decades, he was one of the most successful small-group leaders in jazz. He was a NEA Jazz Ma ...

, whose approach and use of space influenced him. When he returned to the studio in June 1955 to record ''The Musings of Miles'', he wanted a pianist like Jamal and chose Red Garland

William McKinley "Red" Garland Jr. (May 13, 1923 – April 23, 1984) was an American modern jazz pianist. Known for his work as a bandleader and during the 1950s with Miles Davis, Garland helped popularize the block chord style of playing in jazz ...

. '' Blue Haze'' (1956), '' Bags' Groove'' (1957), '' Walkin''' (1957), and '' Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants'' (1959) documented the evolution of his sound with the Harmon mute placed close to the microphone, and the use of more spacious and relaxed phrasing. He assumed a central role in hard bop, less radical in harmony and melody, and used popular songs and American standards as starting points for improvisation. Hard bop distanced itself from cool jazz with a harder beat and music inspired by the blues. A few critics consider ''Walkin' ''(April 1954) the album that created the hard bop genre.

Davis gained a reputation for being cold, distant, and easily angered. He wrote that in 1954 Sugar Ray Robinson "was the most important thing in my life besides music", and he adopted Robinson's "arrogant attitude". He showed contempt for critics and the press.

Davis had an operation to remove polyps from his larynx in October 1955. The doctors told him to remain silent after the operation, but he got into an argument that permanently damaged his vocal cords and gave him a raspy voice for the rest of his life. He was called the "prince of darkness", adding a patina of mystery to his public persona.

1955–1959: Signing with Columbia, first quintet, and modal jazz

In July 1955, Davis's fortunes improved considerably when he played at the Newport Jazz Festival, with a lineup of Monk, Heath, drummer Connie Kay, and horn players Zoot Sims and Gerry Mulligan. The performance was praised by critics and audiences alike, who considered it to be a highlight of the festival as well as helping Davis, the least well known musician in the group, to increase his popularity among affluent white audiences. He tied with Dizzy Gillespie for best trumpeter in the 1955 ''DownBeat'' magazine Readers' Poll. George Avakian ofColumbia Records

Columbia Records is an American reco ...

heard Davis perform at Newport and wanted to sign him to the label. Davis had one year left on his contract with Prestige, which required him to release four more albums. He signed a contract with Columbia that included a $4,000 advance () and required that his recordings for Columbia remain unreleased until his agreement with Prestige expired.

At the request of Avakian, he formed the Miles Davis Quintet for a performance at Café Bohemia. The quintet contained Sonny Rollins on tenor saxophone, Red Garland

William McKinley "Red" Garland Jr. (May 13, 1923 – April 23, 1984) was an American modern jazz pianist. Known for his work as a bandleader and during the 1950s with Miles Davis, Garland helped popularize the block chord style of playing in jazz ...

on piano, Paul Chambers

Paul Laurence Dunbar Chambers Jr. (April 22, 1935 – January 4, 1969) was an American jazz double bassist. A fixture of rhythm sections during the 1950s and 1960s, he has become one of the most widely-known jazz bassists of the hard bop er ...

on double bass, and Philly Joe Jones

Joseph Rudolph "Philly Joe" Jones (July 15, 1923 – August 30, 1985) was an American Jazz drumming, jazz drummer.

Biography Early career

As a child, Jones appeared as a featured tap dancer on ''The Kiddie Show'' on the Philadelphia radio stat ...

on drums. Rollins was replaced by John Coltrane

John William Coltrane (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967) was an American jazz saxophonist, bandleader and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the Jazz#Post-war jazz, history of jazz and 20th-century musi ...

, completing the membership of the first quintet. To fulfill Davis' contract with Prestige, this new group worked through two marathon sessions in May and October 1956 that were released by the label as four LPs: '' Cookin' with the Miles Davis Quintet'' (1957), '' Relaxin' with the Miles Davis Quintet'' (1958), '' Workin' with the Miles Davis Quintet'' (1960) and '' Steamin' with the Miles Davis Quintet'' (1961). Each album was critically acclaimed and helped establish Davis's quintet as one of the best.

The style of the group was an extension of their experience playing with Davis. He played long, legato, melodic lines, while Coltrane contrasted with energetic solos. Their live repertoire was a mix of bebop, standards from the Great American Songbook and pre-bop eras, and traditional tunes. They appeared on '' 'Round About Midnight'', Davis's first album for Columbia.

In 1956, he left his quintet temporarily to tour Europe as part of the Birdland All-Stars, which included the Modern Jazz Quartet and French and German musicians. In Paris, he reunited with Gréco and they "were lovers for many years". He then returned home, reunited his quintet and toured the US for two months. Conflict arose on tour when he grew impatient with the drug habits of Jones and Coltrane. Davis was trying to live a healthier life by exercising and reducing his use of alcohol. But he continued to use cocaine. At the end of the tour, he fired Jones and Coltrane and replaced them with Sonny Rollins and Art Taylor.

In November 1957, Davis went to Paris and recorded the soundtrack

A soundtrack is a recorded audio signal accompanying and synchronised to the images of a book, drama, motion picture, radio program, television show, television program, or video game; colloquially, a commercially released soundtrack album of m ...

to ''Ascenseur pour l'échafaud''. directed by Louis Malle and starring Jeanne Moreau. Consisting of French jazz musicians Barney Wilen, Pierre Michelot, and René Urtreger, and American drummer Kenny Clarke, the group avoided a written score and instead improvised while they watched the film in a recording studio.

After returning to New York, Davis revived his quintet with Adderley and Coltrane, who was clean from his drug habit. Now a sextet, the group recorded material in early 1958 that was released on '' Milestones'', an album on which the title track demonstrated Davis's interest in modal jazz. A performance by Les Ballets Africains drew him to slower, deliberate music that allowed the creation of solos from static harmony rather than constant changing chords.

By May 1958, he had replaced Jones with drummer Jimmy Cobb, and Garland left the group, leaving Davis to play piano on "Sid's Ahead" for ''Milestones''. He wanted someone who could play modal jazz, so he hired Bill Evans, a young pianist with a background in classical music. This new edition of the sextet made their recording debut on '' Jazz Track'' (1958).

Evans had an impressionistic approach to piano. His ideas greatly influenced Davis. But after eight months of touring, a tired Evans left. Wynton Kelly, his replacement, brought to the group a swinging style that contrasted with Evans's delicacy.

1957–1963: Collaborations with Gil Evans and ''Kind of Blue''

By early 1957, Davis was exhausted from recording and touring and wished to pursue new projects. In March, the 30-year-old Davis told journalists of his intention to retire soon and revealed offers he had received to teach atHarvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

and be a musical director at a record label. Avakian agreed that it was time for Davis to explore something different, but Davis rejected his suggestion of returning to his nonet as he considered that a step backward. Avakian then suggested that he work with a bigger ensemble, similar to ''Music for Brass'' (1957), an album of orchestral and brass-arranged music led by Gunther Schuller featuring Davis as a guest soloist.

Davis accepted and worked with Gil Evans in what became a five-album collaboration from 1957 to 1962. '' Miles Ahead'' (1957) showcased Davis on flugelhorn and a rendition of "The Maids of Cadiz" by Léo Delibes, the first piece of classical music that Davis recorded. Evans devised orchestral passages as transitions, thus turning the album into one long piece of music. ''Porgy and Bess

''Porgy and Bess'' ( ) is an English-language opera by American composer George Gershwin, with a libretto written by author DuBose Heyward and lyricist Ira Gershwin. It was adapted from Dorothy Heyward and DuBose Heyward's play ''Porgy (play), ...

'' (1959) includes arrangements of pieces from George Gershwin's opera

Opera is a form of History of theatre#European theatre, Western theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by Singing, singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically ...

. '' Sketches of Spain'' (1960) contained music by Joaquín Rodrigo and Manuel de Falla and originals by Evans. The classical musicians had trouble improvising, while the jazz musicians couldn't handle the difficult arrangements, but the album was a critical success, selling over 120,000 copies in the US. Davis performed with an orchestra conducted by Evans at Carnegie Hall in May 1961 to raise money for charity. The pair's final album was '' Quiet Nights'' (1963), a collection of bossa nova songs released against their wishes. Evans stated it was only half an album and blamed the record company; Davis blamed producer Teo Macero and refused to speak to him for more than two years. The boxed set '' Miles Davis & Gil Evans: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings'' (1996) won the Grammy Award for Best Historical Album and Best Album Notes in 1997.

In March and April 1959, Davis recorded what some consider his greatest album, '' Kind of Blue''. He named the album for its mood. He called back Bill Evans, as the music had been planned around Evans's piano style. Both Davis and Evans were familiar with George Russell's ideas about modal jazz. But Davis neglected to tell pianist Wynton Kelly that Evans was returning, so Kelly appeared on only one song, " Freddie Freeloader". The sextet had played " So What" and " All Blues" at performances, but the remaining three compositions they saw for the first time in the studio.

Released in August 1959, ''Kind of Blue'' was an instant success, with widespread radio airplay and rave reviews from critics. It has remained a strong seller over the years. In 2019, the album achieved 5× platinum certification from the Recording Industry Association of America

The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) is a trade organization that represents the music recording industry in the United States. Its members consist of record labels and distributors that the RIAA says "create, manufacture, and/o ...

for sales of over five million copies in the US, making it one of the most successful jazz albums in history. In 2009, the US House of Representatives passed a resolution that honored it as a national treasure.

In August 1959, during a break in a recording session at the Birdland nightclub in New York City, Davis was escorting a blonde-haired woman to a taxi outside the club when policeman Gerald Kilduff told him to "move on". Davis said that he was working at the club, and he refused to move. Kilduff arrested and grabbed Davis as he tried to protect himself. Witnesses said the policeman hit Davis in the stomach with a nightstick without provocation. Two detectives held the crowd back, while a third approached Davis from behind and beat him over the head. Davis was taken to jail, charged with assaulting an officer, then taken to the hospital where he received five stitches. By January 1960, he was acquitted of disorderly conduct and third-degree assault. He later stated the incident "changed my whole life and whole attitude again, made me feel bitter and cynical again when I was starting to feel good about the things that had changed in this country".

Davis and his sextet toured to support ''Kind of Blue''. Cannonball Adderley left the group September of that year reducing the band back to a quintet. Coltrane was ready to leave as well but Davis persuaded him to play with the group on one final European tour in the spring of 1960. Coltrane then departed to form his quartet, though he returned for a couple tracks on Davis's album '' Someday My Prince Will Come'' (1961). Its front cover shows a photograph of his wife, Frances Taylor, after Davis demanded that Columbia depict black women on his album covers.

1963–1968: Second quintet

In December 1962, Davis, Rollins, Kelly, Chambers and Cobb played together for the last time as the latter three wanted to leave and play as a trio. Rollins left them soon after, leaving Davis to pay over $25,000 () to cancel upcoming gigs and quickly assemble a new group. Following auditions, he found his new band in tenor saxophonist George Coleman, bassist Ron Carter, pianist Victor Feldman, and drummer Frank Butler. By May 1963, Feldman and Butler were replaced by 23-year-old pianistHerbie Hancock

Herbert Jeffrey Hancock (born April 12, 1940) is an American jazz musician, bandleader, and composer. He started his career with trumpeter Donald Byrd's group. Hancock soon joined the Miles Davis Quintet, where he helped to redefine the role of ...

and 17-year-old drummer Tony Williams who made Davis "excited all over again". With this group, Davis completed the rest of what became '' Seven Steps to Heaven'' (1963) and recorded the live albums '' Miles Davis in Europe'' (1964), '' My Funny Valentine'' (1965), and '' Four & More'' (1966). The quintet played essentially the same bebop tunes and standards that Davis's previous bands had played, but they approached them with structural and rhythmic freedom and occasionally breakneck speed.

In 1964, Coleman was briefly replaced by saxophonist Sam Rivers (who recorded with Davis on '' Miles in Tokyo'') until Wayne Shorter was persuaded to leave the Jazz Messengers. The quintet with Shorter lasted through 1968, with Shorter becoming the group's principal composer. The album '' E.S.P.'' (1965) was named after his composition. While touring Europe, the group made its first album, '' Miles in Berlin'' (1965).

Davis needed medical attention for hip pain, which had worsened since his Japanese tour during the previous year. He underwent hip replacement surgery in April 1965, with bone taken from his shin, but it failed. After his third month in the hospital, he discharged himself due to boredom and went home. He returned to the hospital in August after a fall required the insertion of a plastic hip joint. In November 1965, he had recovered enough to return to performing with his quintet, which included gigs at the Plugged Nickel in Chicago. Teo Macero returned as his record producer after their rift over ''Quiet Nights'' had healed.

In January 1966, Davis spent three months in the hospital with a liver infection. When he resumed touring, he performed more at colleges because he had grown tired of the typical jazz venues. Columbia president Clive Davis reported in 1966 his sales had declined to around 40,000–50,000 per album, compared to as many as 100,000 per release a few years before. Matters were not helped by the press reporting his apparent financial troubles and imminent demise. After his appearance at the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival, he returned to the studio with his quintet for a series of sessions. He started a relationship with actress Cicely Tyson, who helped him reduce his alcohol consumption.

Material from the 1966–1968 sessions was released on '' Miles Smiles'' (1966), '' Sorcerer'' (1967), '' Nefertiti'' (1967), '' Miles in the Sky'' (1968), and '' Filles de Kilimanjaro'' (1968). The quintet's approach to the new music became known as "time no changes"—which referred to Davis's decision to depart from chordal sequences and adopt a more open approach, with the rhythm section responding to the soloists' melodies. Through ''Nefertiti'' the studio recordings consisted primarily of originals composed by Shorter, with occasional compositions by the other sidemen. In 1967, the group began to play their concerts in continuous sets, each tune flowing into the next, with only the melody indicating any sort of change. His bands performed this way until his hiatus in 1975.

''Miles in the Sky'' and ''Filles de Kilimanjaro''—which tentatively introduced electric bass, electric piano, and electric guitar on some tracks—pointed the way to the fusion phase of Davis's career. He also began experimenting with more rock-oriented rhythms on these records. By the time the second half of ''Filles de Kilimanjaro'' was recorded, bassist Dave Holland and pianist Chick Corea had replaced Carter and Hancock. Davis soon took over the compositional duties of his sidemen.

Davis needed medical attention for hip pain, which had worsened since his Japanese tour during the previous year. He underwent hip replacement surgery in April 1965, with bone taken from his shin, but it failed. After his third month in the hospital, he discharged himself due to boredom and went home. He returned to the hospital in August after a fall required the insertion of a plastic hip joint. In November 1965, he had recovered enough to return to performing with his quintet, which included gigs at the Plugged Nickel in Chicago. Teo Macero returned as his record producer after their rift over ''Quiet Nights'' had healed.

In January 1966, Davis spent three months in the hospital with a liver infection. When he resumed touring, he performed more at colleges because he had grown tired of the typical jazz venues. Columbia president Clive Davis reported in 1966 his sales had declined to around 40,000–50,000 per album, compared to as many as 100,000 per release a few years before. Matters were not helped by the press reporting his apparent financial troubles and imminent demise. After his appearance at the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival, he returned to the studio with his quintet for a series of sessions. He started a relationship with actress Cicely Tyson, who helped him reduce his alcohol consumption.

Material from the 1966–1968 sessions was released on '' Miles Smiles'' (1966), '' Sorcerer'' (1967), '' Nefertiti'' (1967), '' Miles in the Sky'' (1968), and '' Filles de Kilimanjaro'' (1968). The quintet's approach to the new music became known as "time no changes"—which referred to Davis's decision to depart from chordal sequences and adopt a more open approach, with the rhythm section responding to the soloists' melodies. Through ''Nefertiti'' the studio recordings consisted primarily of originals composed by Shorter, with occasional compositions by the other sidemen. In 1967, the group began to play their concerts in continuous sets, each tune flowing into the next, with only the melody indicating any sort of change. His bands performed this way until his hiatus in 1975.

''Miles in the Sky'' and ''Filles de Kilimanjaro''—which tentatively introduced electric bass, electric piano, and electric guitar on some tracks—pointed the way to the fusion phase of Davis's career. He also began experimenting with more rock-oriented rhythms on these records. By the time the second half of ''Filles de Kilimanjaro'' was recorded, bassist Dave Holland and pianist Chick Corea had replaced Carter and Hancock. Davis soon took over the compositional duties of his sidemen.

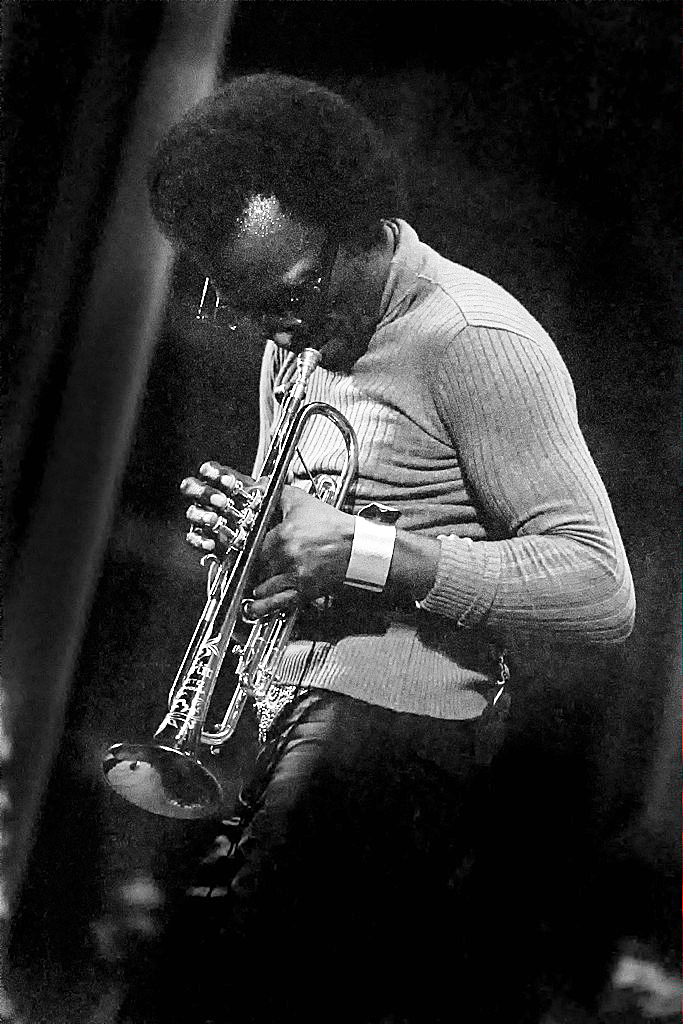

1968–1975: The electric period

'' In a Silent Way'' was recorded in a single studio session in February 1969, with Shorter, Hancock, Holland, and Williams alongside keyboardists Chick Corea and Joe Zawinul and guitarist John McLaughlin. The album contains two side-long tracks that Macero pieced together from different takes recorded at the session. When the album was released later that year, some critics accused him of "selling out" to the rock and roll audience. Nevertheless, it reached number 134 on the US ''Billboard'' Top LPs chart, his first album since ''My Funny Valentine'' to reach the chart. ''In a Silent Way'' was his entry into jazz fusion. The touring band of 1969–1970—with Shorter, Corea, Holland, and DeJohnette—never completed a studio recording together, and became known as Davis's "lost quintet", though radio broadcasts from the band's European tour have been extensively bootlegged. For the double album '' Bitches Brew'' (1970), he hired Jack DeJohnette, Harvey Brooks, and Bennie Maupin. The album contained long compositions, some over twenty minutes, that more often than not, were constructed from several takes by Macero and Davis via splicing and tape loops amid epochal advances in multitrack recording technologies. ''Bitches Brew'' peaked at No. 35 on the ''Billboard'' Album chart. In 1976, it was certified gold for selling over 500,000 records. By 2003, it had sold one million copies.

In March 1970, Davis began to perform as the opening act for rock bands, allowing Columbia to market ''Bitches Brew'' to a larger audience. He shared a

For the double album '' Bitches Brew'' (1970), he hired Jack DeJohnette, Harvey Brooks, and Bennie Maupin. The album contained long compositions, some over twenty minutes, that more often than not, were constructed from several takes by Macero and Davis via splicing and tape loops amid epochal advances in multitrack recording technologies. ''Bitches Brew'' peaked at No. 35 on the ''Billboard'' Album chart. In 1976, it was certified gold for selling over 500,000 records. By 2003, it had sold one million copies.

In March 1970, Davis began to perform as the opening act for rock bands, allowing Columbia to market ''Bitches Brew'' to a larger audience. He shared a Fillmore East

The Fillmore East was Promoter (entertainment), rock promoter Bill Graham (promoter), Bill Graham's rock venue on Second Avenue (Manhattan), Second Avenue near 6th Street (Manhattan), East 6th Street on the Lower East Side section of Manhattan, ...

bill with the Steve Miller Band

The Steve Miller Band is an American rock music, rock band formed in San Francisco, California in 1966. The band is led by Steve Miller (musician), Steve Miller on guitar and lead vocals. The group had a string of mid- to late-1970s hit singles ...

and Neil Young

Neil Percival Young (born November 12, 1945) is a Canadian and American singer-songwriter. After embarking on a music career in Winnipeg in the 1960s, Young moved to Los Angeles, forming the folk rock group Buffalo Springfield. Since the begi ...

with Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse ( , ; – September 5, 1877) was a Lakota people, Lakota war leader of the Oglala band. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by White Americans, White American settlers on Nativ ...

on March 6 and 7. Biographer Paul Tingen wrote, "Miles' newcomer status in this environment" led to "mixed audience reactions, often having to play for dramatically reduced fees, and enduring the 'sell-out' accusations from the jazz world", as well as being "attacked by sections of the black press for supposedly genuflecting to white culture". The 1970 tours included the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival on August 29 when he performed to an estimated 600,000 people, the largest of his career. Plans to record with Hendrix ended after the guitarist's death; his funeral was the last one that Davis attended. Several live albums with a transitional sextet/septet including Corea, DeJohnette, Holland, Airto Moreira, saxophonist Steve Grossman, and keyboardist Keith Jarrett

Keith Jarrett (born May 8, 1945) is an American pianist and composer. Jarrett started his career with Art Blakey and later moved on to play with Charles Lloyd (jazz musician), Charles Lloyd and Miles Davis. Since the early 1970s, he has also be ...

were recorded during this period, including '' Miles Davis at Fillmore'' (1970) and '' Black Beauty: Miles Davis at Fillmore West'' (1973).

By 1971, Davis had signed a contract with Columbia that paid him $100,000 a year () for three years in addition to royalties. He recorded a soundtrack album ('' Jack Johnson'') for the 1970 documentary film about heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson, containing two long pieces of 25 and 26 minutes in length with Hancock, McLaughlin, Sonny Sharrock, and Billy Cobham. He was committed to making music for African-Americans who liked more commercial, pop, groove-oriented music. By November 1971, DeJohnette and Moreira had been replaced in the touring ensemble by drummer Leon "Ndugu" Chancler and percussionists James Mtume and Don Alias

Charles "Don" Alias (December 25, 1939 – March 28, 2006) was an American jazz percussionist.

Alias was best known for playing congas and other hand drums. He was also a capable drum kit performer. He played drums on the song "Miles Runs the V ...

. '' Live-Evil'' was released in the same month. Showcasing bassist Michael Henderson, who had replaced Holland in 1970, the album demonstrated that Davis's ensemble had transformed into a funk-oriented group while retaining the exploratory imperative of ''Bitches Brew''.

In 1972, composer-arranger Paul Buckmaster introduced Davis to the music of avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, leading to a period of creative exploration. Biographer J. K. Chambers wrote, "The effect of Davis' study of Stockhausen could not be repressed for long ... Davis' own 'space music' shows Stockhausen's influence compositionally." His recordings and performances during this period were described as "space music" by fans, Feather, and Buckmaster, who described it as "a lot of mood changes—heavy, dark, intense—definitely space music". The studio album '' On the Corner'' (1972) blended the influence of Stockhausen and Buckmaster with funk elements. Davis invited Buckmaster to New York City to oversee the writing and recording of the album with Macero. The album reached No. 1 on the ''Billboard'' jazz chart but peaked at No. 156 on the more heterogeneous Top 200 Albums chart. Davis felt that Columbia marketed it to the wrong audience. "The music was meant to be heard by young black people, but they just treated it like any other jazz album and advertised it that way, pushed it on the jazz radio stations. Young black kids don't listen to those stations; they listen to R&B stations and some rock stations." In October 1972, he broke his ankles in a car crash. He took painkillers and cocaine to cope with the pain. Looking back at his career after the incident, he wrote, "Everything started to blur."

After recording ''On the Corner'', he assembled a group with Henderson, Mtume, Carlos Garnett, guitarist Reggie Lucas, organist Lonnie Liston Smith, tabla player Badal Roy, sitarist Khalil Balakrishna, and drummer Al Foster. In striking contrast to that of his previous lineups, the music emphasized rhythmic density and shifting textures instead of solos. This group was recorded live in 1972 for '' In Concert'', but Davis found it unsatisfactory, leading him to drop the tabla and sitar and play organ himself. He also added guitarist Pete Cosey. The compilation studio album '' Big Fun'' contains four long improvisations recorded between 1969 and 1972.

Studio sessions throughout 1973 and 1974 led to '' Get Up with It'', an album which included four long pieces alongside four shorter recordings from 1970 and 1972. The track "He Loved Him Madly", a thirty-minute tribute to the recently deceased Duke Ellington, influenced

In 1972, composer-arranger Paul Buckmaster introduced Davis to the music of avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, leading to a period of creative exploration. Biographer J. K. Chambers wrote, "The effect of Davis' study of Stockhausen could not be repressed for long ... Davis' own 'space music' shows Stockhausen's influence compositionally." His recordings and performances during this period were described as "space music" by fans, Feather, and Buckmaster, who described it as "a lot of mood changes—heavy, dark, intense—definitely space music". The studio album '' On the Corner'' (1972) blended the influence of Stockhausen and Buckmaster with funk elements. Davis invited Buckmaster to New York City to oversee the writing and recording of the album with Macero. The album reached No. 1 on the ''Billboard'' jazz chart but peaked at No. 156 on the more heterogeneous Top 200 Albums chart. Davis felt that Columbia marketed it to the wrong audience. "The music was meant to be heard by young black people, but they just treated it like any other jazz album and advertised it that way, pushed it on the jazz radio stations. Young black kids don't listen to those stations; they listen to R&B stations and some rock stations." In October 1972, he broke his ankles in a car crash. He took painkillers and cocaine to cope with the pain. Looking back at his career after the incident, he wrote, "Everything started to blur."

After recording ''On the Corner'', he assembled a group with Henderson, Mtume, Carlos Garnett, guitarist Reggie Lucas, organist Lonnie Liston Smith, tabla player Badal Roy, sitarist Khalil Balakrishna, and drummer Al Foster. In striking contrast to that of his previous lineups, the music emphasized rhythmic density and shifting textures instead of solos. This group was recorded live in 1972 for '' In Concert'', but Davis found it unsatisfactory, leading him to drop the tabla and sitar and play organ himself. He also added guitarist Pete Cosey. The compilation studio album '' Big Fun'' contains four long improvisations recorded between 1969 and 1972.

Studio sessions throughout 1973 and 1974 led to '' Get Up with It'', an album which included four long pieces alongside four shorter recordings from 1970 and 1972. The track "He Loved Him Madly", a thirty-minute tribute to the recently deceased Duke Ellington, influenced Brian Eno

Brian Peter George Jean-Baptiste de la Salle Eno (, born 15 May 1948), also mononymously known as Eno, is an English musician, songwriter, record producer, visual artist, and activist. He is best known for his pioneering contributions to ambien ...

's ambient music