Merenre I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Merenre Nemtyemsaf (meaning "Beloved of Ra,

The earliest historical source on the matter is the South Saqqara Stone, a royal annal inscribed during the reign of either Merenre or Pepi II. An estimated 92% of the text inscribed on the stone was lost when it was roughly polished to be reused as a sarcophagus lid, possibly in the late First Intermediate ( 2160–2055 BC) to early Middle Kingdom period ( 2055–1650 BC). Nonetheless the few legible text fragments of the annal support the succession "

The earliest historical source on the matter is the South Saqqara Stone, a royal annal inscribed during the reign of either Merenre or Pepi II. An estimated 92% of the text inscribed on the stone was lost when it was roughly polished to be reused as a sarcophagus lid, possibly in the late First Intermediate ( 2160–2055 BC) to early Middle Kingdom period ( 2055–1650 BC). Nonetheless the few legible text fragments of the annal support the succession " Three more historical sources agree with this chronology, three of which date to the New Kingdom period. The

Three more historical sources agree with this chronology, three of which date to the New Kingdom period. The

The existence of the co-regency remains uncertain, lacking any definite proof. For Vassil Dobrev and Michel Baud, who analysed the royal annals of the South Saqqara Stone, Merenre directly succeeded his father in power. In particular, the legible parts of the annals bear with no traces in direct support of an interregnum or co-regency. More precisely, the document preserves the record of Pepi I's final year and proceeds immediately to the first year of Merenre. Furthermore, the shape and size of the stone on which the annals are inscribed makes it more probable that Merenre did not start to count his years of reign until soon after the death of his father. Furthermore, William J. Murnane writes that the gold pendant's context is unknown, making its significance regarding the co-regency difficult to appraise. The copper statues are similarly inconclusive as the identity of the smaller one, and whether they originally formed a group, remains uncertain.

The existence of the co-regency remains uncertain, lacking any definite proof. For Vassil Dobrev and Michel Baud, who analysed the royal annals of the South Saqqara Stone, Merenre directly succeeded his father in power. In particular, the legible parts of the annals bear with no traces in direct support of an interregnum or co-regency. More precisely, the document preserves the record of Pepi I's final year and proceeds immediately to the first year of Merenre. Furthermore, the shape and size of the stone on which the annals are inscribed makes it more probable that Merenre did not start to count his years of reign until soon after the death of his father. Furthermore, William J. Murnane writes that the gold pendant's context is unknown, making its significance regarding the co-regency difficult to appraise. The copper statues are similarly inconclusive as the identity of the smaller one, and whether they originally formed a group, remains uncertain.

Developments of the provincial administration were undertaken during Merenre's rule, with a marked increase in the number of provincial administrators including newly created titles for granary and treasury overseers, paralleled with a steep decline in the size of the central administration in Memphis. For the Egyptologists Nigel Strudwick and Petra Andrassy this witnesses to an incessantly evolving domestic policy aimed at managing the remote southern provinces.

The motivations behind such changes are not clear. Either an attempt was made at improving the provincial administration or the goal was to disperse powerful nobles throughout the realm, away from the royal court. Indeed, the many marriages of Pepi I may have generated instability by creating competing groups and factions at court. In any case, the reforms appear to have been implemented rather uniformly, suggesting that the central executive authority of the state was still substantial at that time.

With these changes, provincial officials were now directly responsible for the collection of local tax and labour and dealt with all works in their nomes from then on. The increasing political and economic importance of individual nomes and local centres is reflected in that even the highest ranking officials including the viziers and the

Developments of the provincial administration were undertaken during Merenre's rule, with a marked increase in the number of provincial administrators including newly created titles for granary and treasury overseers, paralleled with a steep decline in the size of the central administration in Memphis. For the Egyptologists Nigel Strudwick and Petra Andrassy this witnesses to an incessantly evolving domestic policy aimed at managing the remote southern provinces.

The motivations behind such changes are not clear. Either an attempt was made at improving the provincial administration or the goal was to disperse powerful nobles throughout the realm, away from the royal court. Indeed, the many marriages of Pepi I may have generated instability by creating competing groups and factions at court. In any case, the reforms appear to have been implemented rather uniformly, suggesting that the central executive authority of the state was still substantial at that time.

With these changes, provincial officials were now directly responsible for the collection of local tax and labour and dealt with all works in their nomes from then on. The increasing political and economic importance of individual nomes and local centres is reflected in that even the highest ranking officials including the viziers and the

During Merenre's reign

During Merenre's reign  In the year of the fifth cattle count since the beginning of his reign, Merenre travelled south to Elephantine from his capital to receive the submission of Nubian chieftains. This is indicated by an inscription and relief located opposite the cataract island of El-Hesseh near Philae:

On the same occasion, Merenre might also have visited the temple of Satet on Elephantine island to renew a naos erected by Pepi I. This is suggested by another inscription of Merenre on the rock face of a natural grotto in a niche of the temple:

Besides Harkhuf, another Egyptian high official who was active in Nubia at the time was Weni, who had been promoted to commander of the army by Pepi I. As such Weni hired Nubian mercenaries for his military campaigns in Sinai and the Levant, mercenaries which were also frequently employed as police force. Weni was also tasked with bringing back from Elephantine to Memphis a

In the year of the fifth cattle count since the beginning of his reign, Merenre travelled south to Elephantine from his capital to receive the submission of Nubian chieftains. This is indicated by an inscription and relief located opposite the cataract island of El-Hesseh near Philae:

On the same occasion, Merenre might also have visited the temple of Satet on Elephantine island to renew a naos erected by Pepi I. This is suggested by another inscription of Merenre on the rock face of a natural grotto in a niche of the temple:

Besides Harkhuf, another Egyptian high official who was active in Nubia at the time was Weni, who had been promoted to commander of the army by Pepi I. As such Weni hired Nubian mercenaries for his military campaigns in Sinai and the Levant, mercenaries which were also frequently employed as police force. Weni was also tasked with bringing back from Elephantine to Memphis a

In 1881, the Egyptologists Émile and

In 1881, the Egyptologists Émile and

Nemty

In Egyptian mythology, Nemty (Antaeus in Greek, but probably not connected to the Antaeus in Greek mythology) was a god whose worship centered at Antaeopolis in the northern part of Upper Egypt.

Nemty's worship is quite ancient, dating from at l ...

is his protection"; died 2278 BC) was an Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

ian king

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

, fourth king of the Sixth Dynasty

The Sixth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty VI), along with the Third Dynasty of Egypt, Third, Fourth Dynasty of Egypt, Fourth and Fifth Dynasty of Egypt, Fifth Dynasty, constitutes the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom of Dynastic Egyp ...

. He ruled Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

for around 5 years in the early 23rd century BC, toward the end of the Old Kingdom period. He was the son of his predecessor Pepi I Meryre

Pepi I Meryre (also Pepy I; died 2283 BC) was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, king, third king of the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt, who ruled for over 40 years from the 24th to the 23rd century BC, toward the end of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Ki ...

and queen Ankhesenpepi I

Ankhesenpepi I (also Ankhenespepi I or Ankhenesmeryre I; ) was a queen consort during the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt.

Biography

Ankhesenpepi was a daughter of the female vizier Nebet and her husband Khui, nomarch of Abydos. Ankhesenpepi's sister w ...

and was in turn succeeded by Pepi II Neferkare

Pepi II Neferkare ( 2284 BC – 2214 BC) was a king of the Sixth Dynasty in Egypt's Old Kingdom. His second name, Neferkare (''Nefer-ka-Re''), means "Beautiful is the Ka of Re". He succeeded to the throne at age six, after the death of Nemty ...

who might have been his son or less probably his brother. Pepi I may have shared power with Merenre in a co-regency at the very end of the former's reign. Merenre is frequently called Merenre I by Egyptologists.

Merenre's rule saw profound changes in the administration of the southern provinces of Egypt, with a marked increase in the number of

provincial administrators and a concurrent steep decline in the size of the central administration in the capital Memphis. As a consequence the provincial nobility became responsible for tax collection and resource management, gaining in political independence and economic power. This led to the first provincial burials for the highest officials including viziers

A vizier (; ; ) is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the Near East. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was at first merely a helper but afterwards became the rep ...

, governors of Upper Egypt and nomarch

A nomarch (, Great Chief) was a provincial governor in ancient Egypt; the country was divided into 42 provinces, called Nome (Egypt), nomes (singular , plural ). A nomarch was the government official responsible for a nome.

Etymology

The te ...

s.

Several trading and quarrying expeditions took place under Merenre, in particular to Nubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

where caravans numbering hundreds of donkeys were sent to fetch incense

Incense is an aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremonial reasons. It ...

, ebony

Ebony is a dense black/brown hardwood, coming from several species in the genus '' Diospyros'', which also includes the persimmon tree. A few ''Diospyros'' species, such as macassar and mun ebony, are dense enough to sink in water. Ebony is fin ...

, animal skins, ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

and exotic animals. Such was the interest in the region that Merenre had a canal dug to facilitate the navigation of the first cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens (anatomy), lens of the eye that leads to a visual impairment, decrease in vision of the eye. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colours, blurry or ...

into Nubia. Trade with the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

ine coast for lapis lazuli

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color. Originating from the Persian word for the gem, ''lāžward'', lapis lazuli is ...

, silver, bitumen

Bitumen ( , ) is an immensely viscosity, viscous constituent of petroleum. Depending on its exact composition, it can be a sticky, black liquid or an apparently solid mass that behaves as a liquid over very large time scales. In American Engl ...

, and tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

took place while quarrying for granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

, travertine

Travertine ( ) is a form of terrestrial limestone deposited around mineral springs, especially hot springs. It often has a fibrous or concentric appearance and exists in white, tan, cream-colored, and rusty varieties. It is formed by a process ...

and alabaster

Alabaster is a mineral and a soft Rock (geology), rock used for carvings and as a source of plaster powder. Archaeologists, geologists, and the stone industry have different definitions for the word ''alabaster''. In archaeology, the term ''alab ...

took place in the south and in the Eastern Desert

The Eastern Desert (known archaically as Arabia or the Arabian Desert) is the part of the Sahara Desert that is located east of the Nile River. It spans of northeastern Africa and is bordered by the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea to the east, a ...

.

A pyramid complex was built for Merenre in Saqqara

Saqqara ( : saqqāra ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for ...

, known as ''Khanefermerenre'' by the Ancient Egyptians meaning "The appearance of the perfection of Merenre" and likely completed prior to the king's death. The subterranean chambers were inscribed with the Pyramid Texts

The Pyramid Texts are the oldest ancient Egyptian funerary texts, dating to the late Old Kingdom. They are the earliest known corpus of ancient Egyptian religious texts. Written in Old Egyptian, the pyramid texts were carved onto the subterranea ...

. In the burial chamber, the black basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

sarcophagus of the king still held a mummy when it was entered in the 19th century. The identification of the mummy as Merenre's is still uncertain. Following his death, Merenre was the object of a funerary cult until at least the end of the Old Kingdom. During the New Kingdom period, he was in a selection of past kings to be honoured.

Family

Parents and siblings

Merenre was the son of kingPepi I Meryre

Pepi I Meryre (also Pepy I; died 2283 BC) was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, king, third king of the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt, who ruled for over 40 years from the 24th to the 23rd century BC, toward the end of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Ki ...

and queen Ankhesenpepi I

Ankhesenpepi I (also Ankhenespepi I or Ankhenesmeryre I; ) was a queen consort during the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt.

Biography

Ankhesenpepi was a daughter of the female vizier Nebet and her husband Khui, nomarch of Abydos. Ankhesenpepi's sister w ...

, also called Ankhesenmeryre. Pepi I probably begot him in his old age. Ankhesenpepi's motherhood is indicated by her titles. She bore the title of "mother of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt of the pyramid of Merenre" in tomb inscriptions, a style which at the time indicated relation to the king. Ankhesenpepi was a daughter of the nomarch

A nomarch (, Great Chief) was a provincial governor in ancient Egypt; the country was divided into 42 provinces, called Nome (Egypt), nomes (singular , plural ). A nomarch was the government official responsible for a nome.

Etymology

The te ...

of Abydos, Khui, and his wife Nebet

Nebet (“Lady”; ) was created Vizier (Ancient Egypt), vizier during the late Old Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, Egypt by Pharaoh, King Pepi I of the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt, Sixth Dynasty, who was her son-in-law (and possibly also her nephew). She ...

. Pepi I made her into a vizier

A vizier (; ; ) is a high-ranking political advisor or Minister (government), minister in the Near East. The Abbasids, Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was at first merely a help ...

, the sole woman of the Old Kingdom period known to have held such a title. Khui and Nebet's son, Merenre's uncle Djau

Djau () was a vizier of Upper Egypt during the Sixth Dynasty. He was a member of an influential family from Abydos; his mother was the vizier Nebet, and his father was Khui. His two sisters Ankhesenpepi I and Ankhesenpepi II married King Pepi ...

, served in the position of vizier under Merenre and Pepi II Neferkare

Pepi II Neferkare ( 2284 BC – 2214 BC) was a king of the Sixth Dynasty in Egypt's Old Kingdom. His second name, Neferkare (''Nefer-ka-Re''), means "Beautiful is the Ka of Re". He succeeded to the throne at age six, after the death of Nemty ...

.

Princess Neith

Neith (, a borrowing of the Demotic (Egyptian), Demotic form , also spelled Nit, Net, or Neit) was an ancient Egyptian deity, possibly of Ancient Libya, Libyan origin. She was connected with warfare, as indicated by her emblem of two crossed b ...

was Merenre's full sister. The archaeologist Gustave Jéquier has proposed that Neith was first married to Merenre then to Pepi II, explaining the absence of her tomb near that of Merenre as would be expected of a royal spouse. The Egyptologist Vivienne Callender observes however that among Neith's titles presented in her tomb, those referring to her relation to Merenre are now illegible. Consequently, Callender states that whether or not she was married to Merenre cannot be ascertained beyond doubt.

Probable children of Pepi I who might thus be at least half-siblings of Merenre include princes Hornetjerkhet and Tetiankh and princess Meritites IV.

Consorts and children

Sixth dynasty royal seals and stone blocks found atSaqqara

Saqqara ( : saqqāra ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for ...

demonstrate that Merenre's aunt Ankhesenpepi II

Ankhesenpepi II or Ankhesenmeryre II () was a queen consort during the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the wife of Kings Pepi I and Merenre Nemtyemsaf I, Nemtyemsaf I, and the mother of Pepi II. She likely served as regent during the minority of ...

, who married Pepi I, was also married to Merenre. She was the mother of the future pharaoh Pepi II. This is shown by her titles of "royal wife of the pyramid of Meryre", "Royal wife of the pyramid of Merenre" and "royal mother of the pyramid of Neferkare epi II.

Many Egyptologists favour Pepi I as the father of Pepi II. But the Egyptologist Philippe Collombert observes that since historical sources agree that Merenre's reign intervened between those of Pepi I and Pepi II and lasted for around a decade, and given that one source states that Pepi II acceded to the throne at the age of six, then this indirectly indicates that Merenre I, rather than Pepi I, was Pepi II's father. This opinion is shared by the Egyptologists Naguib Kanawati and Peter Brand.

Merenre had at least one daughter, Ankhesenpepi III

Ankhesenpepi III () was an ancient Egyptian queen of the Sixth Dynasty as a consort of Pepi II, who was probably her uncle. She was a daughter of Nemtyemsaf I and was named after her grandmother, Ankhesenpepi I.Dodson and Hilton: The Complete R ...

, who became the wife of Pepi II. Merenre could also be the father of queen Iput II, another wife of Pepi II.

Reign

Attestations

Merenre is well attested by archaeology not only through his pyramid complex, but also through inscriptions and small artefacts bearing his name. These include * an alabaster vessel (inventory E 23140b) and ivory box (inventory N. 794), both in the Louvre Museum * a smallsphinx

A sphinx ( ; , ; or sphinges ) is a mythical creature with the head of a human, the body of a lion, and the wings of an eagle.

In Culture of Greece, Greek tradition, the sphinx is a treacherous and merciless being with the head of a woman, th ...

in the National Museum of Scotland

The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, Scotland, is a museum of Scottish history and culture.

It was formed in 2006 with the merger of the new Museum of Scotland, with collections relating to Scottish antiquities, culture and history, ...

(inventory 1984.405)

* another sphinx in the Pushkin Museum

The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts (, abbreviated as , ''GMII'') is the largest museum of European art in Moscow. It is located in Volkhonka street, just opposite the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. The International musical festival Sviatos ...

* a calcite vessel in shape of a mother monkey and her child in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an Encyclopedic museum, encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the List of largest museums, third-largest museum in the world and the List of larg ...

* a vase (inventory EA4493), a box (inventory EA65848) and a fragment of tomb painting (inventory EA65927), all in the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

* an alabaster vase (inventory no.3252) in the National Archaeological Museum, Florence

The National Archaeological Museum of Florence (Italian – Museo archeologico nazionale di Firenze) is an archaeological museum in Florence, Italy. It is located at 1 piazza Santissima Annunziata, in the Palazzo della Crocetta (a palace built ...

* a similar vessel from Elephantine

Elephantine ( ; ; ; ''Elephantíne''; , ) is an island on the Nile, forming part of the city of Aswan in Upper Egypt. The archaeological site, archaeological digs on the island became a World Heritage Site in 1979, along with other examples of ...

that was in the Egyptian Museum

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, commonly known as the Egyptian Museum (, Egyptian Arabic: ) (also called the Cairo Museum), located in Cairo, Egypt, houses the largest collection of Ancient Egypt, Egyptian antiquities in the world. It hou ...

in Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

(inventory CG 18694) in 1907

Chronology

Relative

The relative chronological position of Merenre Nemtyemsaf I within theSixth Dynasty

The Sixth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty VI), along with the Third Dynasty of Egypt, Third, Fourth Dynasty of Egypt, Fourth and Fifth Dynasty of Egypt, Fifth Dynasty, constitutes the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom of Dynastic Egyp ...

is certain. Historical sources and archaeological evidences agree that he succeeded Pepi I Meryre on the throne and was in turn succeeded by Pepi II Neferkare, evidencing that he was the fourth king of the dynasty.

The earliest historical source on the matter is the South Saqqara Stone, a royal annal inscribed during the reign of either Merenre or Pepi II. An estimated 92% of the text inscribed on the stone was lost when it was roughly polished to be reused as a sarcophagus lid, possibly in the late First Intermediate ( 2160–2055 BC) to early Middle Kingdom period ( 2055–1650 BC). Nonetheless the few legible text fragments of the annal support the succession "

The earliest historical source on the matter is the South Saqqara Stone, a royal annal inscribed during the reign of either Merenre or Pepi II. An estimated 92% of the text inscribed on the stone was lost when it was roughly polished to be reused as a sarcophagus lid, possibly in the late First Intermediate ( 2160–2055 BC) to early Middle Kingdom period ( 2055–1650 BC). Nonetheless the few legible text fragments of the annal support the succession "Teti

Teti, less commonly known as Othoes, sometimes also Tata, Atat, or Athath in outdated sources (died 2333 BC), was the first pharaoh, king of the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt. He was buried at Saqqara. The exact length of his reign has been destroye ...

→ Userkare

Userkare (also Woserkare, meaning "Powerful is the soul of Ra"; died 2332 BC) was the second Pharaoh, king of the Sixth dynasty of Egypt, Sixth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, Egypt, reigning briefly, 1 to 5 years, in the late 24th or the early 23rd ...

→ Pepi I → Merenre I" possibly followed by Pepi II, making Merenre the fourth king of the Sixth Dynasty.

Three more historical sources agree with this chronology, three of which date to the New Kingdom period. The

Three more historical sources agree with this chronology, three of which date to the New Kingdom period. The Abydos King List

The Abydos King List, also known as the Abydos Table or the Abydos Tablet, is a list of the names of 76 kings of ancient Egypt, found on a wall of the Temple of Seti I at Abydos, Egypt. It consists of three rows of 38 cartouches (borders enclos ...

, written under Seti I ( ) places Merenre I's cartouche as the 37th entry between those of Pepi I and Pepi II. The Turin Canon

The Turin King List, also known as the Turin Royal Canon, is an ancient Egyptian hieratic papyrus thought to date from the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II (r. 1279–1213 BC), now in the Museo Egizio (Egyptian Museum) in Turin. The papyrus is the m ...

, a list of kings on papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, ''Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'' or ''papyruses'') can a ...

dating to the reign of Ramses II ( ) probably records Merenre I in the fifth column, fourth row, and may have supported his relative position within the dynasty although his name as well as those of his predecessor and successor is illegible. If the attribution of the entry is correct, then Merenre is credited with a reign length ending with the number four, perhaps some years and four months, or four or 14 years. Also dating to the reign of Ramses II is the Saqqara Tablet

The Saqqara Tablet, also known as the Saqqara King List or the Saqqara Table, now in the Egyptian Museum, is an ancient stone engraving surviving from the Ramesside Period of Egypt which features a list of pharaohs. It was found in 1861 in Saqqar ...

, explicitly relating the succession "Pepi I → Merenre I → Pepi II", with Merenre located on the 24th entry.

The latest historical source recording a similar information is the (), a history of Egypt written in the third century BC during the reign of Ptolemy II

Ptolemy II Philadelphus (, ''Ptolemaîos Philádelphos'', "Ptolemy, sibling-lover"; 309 – 28 January 246 BC) was the pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt from 284 to 246 BC. He was the son of Ptolemy I, the Macedonian Greek general of Alexander the G ...

(283–246 BC) by the priest-historian Manetho

Manetho (; ''Manéthōn'', ''gen''.: Μανέθωνος, ''fl''. 290–260 BCE) was an Egyptian priest of the Ptolemaic Kingdom who lived in the early third century BCE, at the very beginning of the Hellenistic period. Little is certain about his ...

. No copies of the ''Aegyptiaca'' have survived and it is now known only through later writings by Sextus Julius Africanus

Sextus Julius Africanus ( 160 – c. 240; ) was a Christian traveler and historian of the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries. He influenced fellow historian Eusebius, later writers of Church history among the Church Fathers, and the Greek sch ...

and Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

. According to the Byzantine scholar George Syncellus

George Syncellus (, ''Georgios Synkellos''; died after 810) was a Byzantine chronicler and ecclesiastical official. He lived many years in Palestine (probably in the Old Lavra of Saint Chariton or Souka, near Tekoa) as a monk, before coming to Cons ...

, Africanus wrote that the mentioned the succession "Othoês → Phius → Methusuphis → Phiops" at the beginning of the Sixth Dynasty. Othoês, Phius, Methusuphis (in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, ) and Phiops are believed to be the Hellenised

Hellenization or Hellenification is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language, and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonisation often led to the Hellenisation of indigenous people in the Hellenistic period, many of the te ...

forms for Teti, Pepi I, Merenre and Pepi II, respectively. The ''Aegyptiaca'' credits Methusuphis with seven years of reign.

Absolute

Merenre's reign is difficult to date precisely in absolute terms. An absolute chronology referring to dates in our modern calendar is estimated by Egyptologists working backwards by adding reign lengths—themselves uncertain and inferred from historical sources and archaeological evidence—and, in a few cases, using ancient astronomical observations andradiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for Chronological dating, determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of carbon-14, radiocarbon, a radioactive Isotop ...

. These methodologies do not agree perfectly and some uncertainty remains. As a result, Merenre's rule is generally dated to the early 23rd century BC. Various hypotheses have been proposed by scholars though it is impossible to determine which one is right.

Duration

During the Old Kingdom period, Ancient Egyptians dated their documents and inscriptions by counting the years since the accession of the current king to the throne. These years were often referred to by the number of cattle counts which had taken place since the reign's start. The cattle count, which involved counting cattle, oxen and small livestock, was an important event aimed at evaluating the amount of taxes to be levied on the population. During the early Sixth Dynasty this count was perhaps biennial, occurring every two years. The latest surviving inscription written during Merenre's rule is located in a quarry at Hatnub mentioning the year after the 5th cattle count. If the cattle count was regular and purely biennial, this might correspond to Merenre's tenth year on the throne. Similarly, for Baud and Dobrev a regular biennial count implies that the South Saqqara Stone recorded at least 11 to 13 years of reign for Merenre, almost twice the figure of seven years attributed to him in the ''Aegyptiaca''. For Baud such a reign length is consistent with the finished state of Merenre's pyramid complex. In 1959, the Egyptologist and philologistAlan Gardiner

Sir Alan Henderson Gardiner, (29 March 1879 – 19 December 1963) was an English Egyptologist, linguist, philologist, and independent scholar. He is regarded as one of the premier Egyptologists of the early and mid-20th century.

Personal li ...

proposed reading a now discounted 44 years figure on the Turin canon for Merenre, which the Egyptologist and art historian William Stevenson Smith later took to be 14 years instead, of which he attributes nine to a co-regency between Merenre and Pepi I. The Egyptologist Elmar Edel thought such lengths of reign would explain the time necessary for the peaceful relations that Egypt entertained with Lower Nubian chiefs under Merenre to switch to more adversarial ones under Pepi II.

In contrast, because of doubts on the regularity of the cattle count and of the general paucity of monuments and documents datable to his reign, Merenre is often credited with less than a decade on the throne by most modern Egyptologists: some give him nine to eleven years; while others propose six or seven years of reign.

Accession to the throne: co-regency

Merenre's father Pepi's rule seemed to have been troubled at times, with at least one conspiracy against him hatched by one of his harem consorts. This may have given him the impetus to ally himself with Khui, the nomarch of Coptos, by marrying his daughters, queens Ankhesenpepi I and II. The EgyptologistNaguib Kanawati

Naguib Kanawati (born 1941) is an Egyptian Australian Egyptologist and Professor of Egyptology at Macquarie University in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Early life

Kanawati was born in Alexandria, Egypt to a Melkite Greek Catholic Churc ...

conjectures that Pepi faced another conspiracy toward the end of his reign, in which his vizier Rawer may have been involved. To support his theory, Kanawati observes that Rawer's image in his tomb has been desecrated, with his name, hands and feet chiselled off, while this same tomb is dated to the second half of Pepi's reign on stylistic grounds. Kanawati further posits that the conspiracy may have aimed at having someone else made heir to the throne at the expense of the designated heir Merenre. Because of this failed conspiracy, Pepi I may have taken the drastic step of crowning Merenre during his own reign, possibly "in an

attempt to secure stability and continuity within the family" as Miroslav Bárta writes; thereby creating the earliest documented co-regency in the history of Egypt. The Egyptologists Jaromir Málek and Miroslav Verner agree with this analysis; Verner adds that Merenre acceded to the throne at an early age and died young.

That such a co-regency took place was first proposed by Étienne Drioton

Étienne Marie Felix Drioton (21 November 1889 – 17 January 1961) was a French Egyptologist, archaeologist, and Catholic Canon (priest), canon. He was born in Nancy, France, Nancy and died in Montgeron.

Biography

Etienne Drioton, his father, wa ...

who pointed to a gold pendant bearing the names of both Pepi I and Merenre I as living kings, implying that both ruled concurrently for some time. In support of this hypothesis, the Egyptologist Hans Goedicke mentions the inscription dated to Merenre's year of the fifth cattle count from Hatnub which he takes to indicate ten years of rule hence contradicting Manetho's figure of seven years. This could be evidence that Merenre dated the start of his reign before the end of his father's reign, as a co-regency would permit.

A possible further piece of evidence for a co-regency is given by two copper statues uncovered in an underground store beneath the floor of a Ka-chapel of Pepi in Hierakonpolis

Nekhen (, ), also known as Hierakonpolis (; , meaning City of Hawks or City of Falcons, a reference to Horus; ) was the religious and political capital of Upper Egypt at the end of prehistoric Egypt ( 3200–3100 BC) and probably also during th ...

. There the Egyptologist James Quibell

James Edward Quibell (11 November 1867 – 5 June 1935) was a British Egyptologist.

Life

Quibell was born in Newport, Shropshire. He married the Scottish artist and archaeologist Annie Abernethie Pirie in 1900.Bierbrier, M. L. 2012. ''Who Was W ...

uncovered a statue of King Khasekhemwy

Khasekhemwy (ca. 2690 BC; ', also rendered ''Kha-sekhemui'') was the last Pharaoh of the Second Dynasty of Egypt. Little is known about him, other than that he led several significant military campaigns and built the mudbrick fort known as S ...

of the Second Dynasty, a terracotta lion cub made during the Thinite era, a golden mask representing Horus and two copper statues. Originally fashioned by hammering plates of copper over a wooden base, these statues had been disassembled, placed inside one another and then sealed with a thin layer of engraved copper bearing the titles and names of Pepi I "on the first day of the Sed festival

The Sed festival (''ḥb-sd'', Egyptian language#Egyptological pronunciation, conventional pronunciation ; also known as Heb Sed or Feast of the Tail) was an ancient Egyptian ceremony that celebrated the continued rule of a pharaoh. The name is ...

". The two statues were symbolically "trampling underfoot the Nine bows

The Nine Bows is a visual representation in Art of ancient Egypt, Ancient Egyptian art of foreigners or others. Besides the nine bows, there were no other generic representations of foreigners. Due to its ability to stand in for any nine enemies ...

"—the enemies of Egypt—a stylized representation of Egypt's conquered foreign subjects. While the identity of the larger adult figure as Pepi I is revealed by the inscription, the identity of the smaller statue showing a younger person remains unresolved. The most common hypothesis among Egyptologists is that the young man shown is Merenre. As Alessandro Bongioanni and Maria Croce write: " erenrewas publicly associated as his father's successor on the occasion of the Jubilee he Sed festival The placement of his copper effigy inside that of his father would therefore reflect the continuity of the royal succession and the passage of the royal sceptre from father to son before the death of the pharaoh could cause a dynastic split." Alternatively, Bongioanni and Croce have also proposed the smaller statue may represent "a more youthful Pepi I, reinvigorated by the celebration of the Jubilee ceremonies".

The existence of the co-regency remains uncertain, lacking any definite proof. For Vassil Dobrev and Michel Baud, who analysed the royal annals of the South Saqqara Stone, Merenre directly succeeded his father in power. In particular, the legible parts of the annals bear with no traces in direct support of an interregnum or co-regency. More precisely, the document preserves the record of Pepi I's final year and proceeds immediately to the first year of Merenre. Furthermore, the shape and size of the stone on which the annals are inscribed makes it more probable that Merenre did not start to count his years of reign until soon after the death of his father. Furthermore, William J. Murnane writes that the gold pendant's context is unknown, making its significance regarding the co-regency difficult to appraise. The copper statues are similarly inconclusive as the identity of the smaller one, and whether they originally formed a group, remains uncertain.

The existence of the co-regency remains uncertain, lacking any definite proof. For Vassil Dobrev and Michel Baud, who analysed the royal annals of the South Saqqara Stone, Merenre directly succeeded his father in power. In particular, the legible parts of the annals bear with no traces in direct support of an interregnum or co-regency. More precisely, the document preserves the record of Pepi I's final year and proceeds immediately to the first year of Merenre. Furthermore, the shape and size of the stone on which the annals are inscribed makes it more probable that Merenre did not start to count his years of reign until soon after the death of his father. Furthermore, William J. Murnane writes that the gold pendant's context is unknown, making its significance regarding the co-regency difficult to appraise. The copper statues are similarly inconclusive as the identity of the smaller one, and whether they originally formed a group, remains uncertain.

Domestic activities

Administration

overseers of Upper Egypt

Overseer may refer to:

Professions

*Supervisor or superintendent; one who keeps watch over and directs the work of others

* Plantation overseer, often in the context of forced labor or slavery

*Overseer of the poor, an official who administered re ...

started to be abundantly buried in the provinces rather than close to the royal necropolis. For example, the nomarch of the second nome Qar was buried in Edfu, nomarchs Harkhuf and later Heqaib in Qubbet el-Hawa

Qubbet el-Hawa or "Dome of the Wind" is a site on the western bank of the Nile, opposite Aswan, that serves as the resting place of ancient nobles and priests from the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old and Middle Kingdom of Egypt, Middle Kingdoms of anc ...

near Aswan

Aswan (, also ; ) is a city in Southern Egypt, and is the capital of the Aswan Governorate.

Aswan is a busy market and tourist centre located just north of the Aswan Dam on the east bank of the Nile at the first cataract. The modern city ha ...

, vizier Idi near modern-day Asyut

AsyutAlso spelled ''Assiout'' or ''Assiut''. ( ' ) is the capital of the modern Asyut Governorate in Egypt. It was built close to the ancient city of the same name, which is situated nearby. The modern city is located at , while the ancient city i ...

and vizier Weni in the eighth nome at Abydos. More provincial burials of Upper Egyptian nomarchs from this time period have been uncovered in Elephantine, Thebes (fourth nome), Coptos (fifth nome), Dendera

Dendera ( ''Dandarah''; ; Bohairic ; Sahidic ), also spelled ''Denderah'', ancient Iunet 𓉺𓈖𓏏𓊖 “jwn.t”, Tentyris,(Arabic: Ewan-t إيوان-ة ), or Tentyra is a small town and former bishopric in Egypt situated on the west bank of ...

(sixth nome), Qasr el-Sayed (seventh nome), Akhmim

Akhmim (, ; Akhmimic , ; Sahidic/Bohairic ) is a city in the Sohag Governorate of Upper Egypt. Referred to by the ancient Greeks as Khemmis or Chemmis () and Panopolis (), it is located on the east bank of the Nile, to the northeast of Sohag.

...

(ninth nome), Deir el-Gabrawi (12th nome), Meir

Meir () is a Jewish male given name and an occasional surname. It means "one who shines". It is often Germanized as Maier, Mayer, Mayr, Meier, Meyer, Meijer, Italianized as Miagro, or Anglicized as Mayer, Meyer, or Myer. Alfred J. Kolatch, ''T ...

(14th nome), El Sheikh Sa'id (15th nome), Zawyet el-Maiyitin (16th nome), Kom el-Ahmar (18th nome), Dishasha (20th nome) and Balat in the Dakhla Oasis

Dakhla Oasis or Dakhleh Oasis ( Egyptian Arabic: , , "''the inner oases"''), is one of the seven oases of Egypt's Western Desert. Dakhla Oasis lies in the New Valley Governorate, 350 km (220 mi.) from the Nile and between the oases ...

. These rock-cut tombs are markedly different from the mastaba

A mastaba ( , or ), also mastabah or mastabat) is a type of ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inward sloping sides, constructed out of mudbricks or limestone. These edifices marked the burial sites ...

s of the royal necropolises. At the same time, Pepi I, Merenre and Pepi II deliberately set up cults for queens Ankhesenpepi I, Ankhesenpepi II and later Iput II in the Qift

Qift ( ; ''Keft'' or ''Kebto''; Egyptian Gebtu; ''Coptos'' / ''Koptos''; Roman Justinianopolis) is a city in the Qena Governorate of Egypt about north of Luxor, situated a little south of latitude 26° north, on the east bank of the Nile. In a ...

province, whence they originated. Richard Bußmann says this was an effort to "strengthen the kings' ties to powerful families in Upper Egypt".

At the personal level, Merenre may have appointed Idi, possibly a relative of Djau, to the courtly rank of sole companion of the king and nomarch of the Upper Egyptian eighth nome. Idi later served Pepi II in the 12th nome. Another administrative official whom Merenre promoted was Weni. He was made leader of quarrying expeditions then a count and governor of Upper Egypt. In this role Weni organised two censuses and two corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid forced labour that is intermittent in nature, lasting for limited periods of time, typically only a certain number of days' work each year. Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state (polity), state for the ...

s in the South on behalf of the court. Weni was then elevated to the highest offices, those of vizier and chief judge, and likely died during Merenre's reign. Merenre appointed Qar nomarch of Edfu and overseer of Upper Egyptian grain and livestock resources. He was also appointed chief judge over the whole of Upper Egypt. Merenre also made Kaihap Tjeti, a provincial-born young royal courtier under Pepi I, into a stolist of the god Min. Kaihap Tjeti later became nomarch of the ninth Upper Egyptian nome under Merenre or Pepi II, and was buried near Akhmim.

Cultic activities

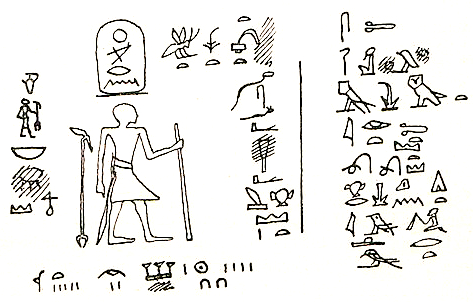

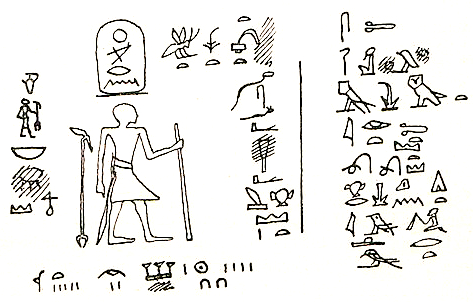

upright=1.15, Fragments of private stele bearing Merenre's cartouche from Kom el-Sultan, alt=Drawing in black ink on yellow paper of pieces of hieroglyphic inscriptions Religious activities dating to Merenre's reign are recorded on the legible passages of the South Saqqara Stone: early in his reign he offered 30 oxen to an unidentified god and five toWadjet

Wadjet (; "Green One"), known to the Greek world as Uto (; ) or Buto (; ) among other renderings including Wedjat, Uadjet, and Udjo, was originally the ancient Egyptian Tutelary deity, local goddess of the city of Dep or Buto in Lower Egypt, ...

. To Seth

Seth, in the Abrahamic religions, was the third son of Adam and Eve. The Hebrew Bible names two of his siblings (although it also states that he had others): his brothers Cain and Abel. According to , Seth was born after Abel's murder by Cain, ...

he offered a lost number of oxen. A statue of the king might also have been erected in the first couple of years of his reign. Additional offerings can be inferred from the surviving remnants of the texts, numbering hundreds or even thousands of oxen, lapis-lazuli, loincloths, incense to Ptah

Ptah ( ; , ; ; ; ) is an ancient Egyptian deity, a creator god, and a patron deity of craftsmen and architects. In the triad of Memphis, he is the husband of Sekhmet and the father of Nefertem. He was also regarded as the father of the ...

, Heryshaf

In Egyptian mythology, Heryshaf, or Hershef ( "He who is on His Lake"),Forty, Jo. ''Mythology: A Visual Encyclopedia'', Sterling Publishing Co., 2001, p. 84. transcribed in Greek as Harsaphes or Arsaphes () was an ancient ram deity whose cult was ...

, Nefertum

Nefertem (; possibly "beautiful one who closes" or "one who does not close"; also spelled Nefertum or Nefer-temu) was, in Egyptian mythology, originally a lotus flower at the creation of the world, who had arisen from the primal waters.Nefertem pa ...

and the Ennead

The Ennead or Great Ennead was a group of nine deities in Egyptian mythology worshipped at Heliopolis: the sun god Atum; his children Shu and Tefnut; their children Geb and Nut; and their children Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys. The Enn ...

, hundreds of birds and perfumed oil to Khenti-Amentiu

Khenti-Amentiu, also Khentiamentiu, Khenti-Amenti, Kenti-Amentiu and many other spellings, is an ancient Egyptian deity whose name was also used as a title for Osiris and Anubis. The name means " Foremost of the Westerners" or "Chief of the Wester ...

, and silver objects and kohl

Kohl may refer to:

*Kohl (cosmetics), an ancient eye cosmetic

*Kohl (surname), including a list of people with the surname

*Kohl's

Kohl's Corporation (Kohl's is stylized in all caps) is an American department store retail chain store, chain. ...

to Khenti-kheti. The list of offerings also mentions Djedkare Isesi

Djedkare Isesi (known in Greek as Tancheres; died 2375 BC) was a king, the eighth and penultimate ruler of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt in the late 25th century to mid-24th century BC, during the Old Kingdom. Djedkare succeeded Menkauhor Kaiu ...

, penultimate king of the Fifth Dynasty, who seems to have been held in high esteem during Merenre's reign. Merenre even chose to place his pyramid complex close to that of Djedkare.

In addition to these activities, Merenre made a decree pertaining to the funerary cult of Menkaure

Menkaure or Menkaura (; 2550 BC - 2503 BC) was a king of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt during the Old Kingdom. He is well known under his Hellenized names Mykerinos ( by Herodotus), in turn Latinized as Mycerinus, and Menkheres ( by Manetho). ...

as shown by fragmentary inscriptions uncovered in the latter's mortuary temple.

Construction works

The main monument dating to Merenre's reign is his pyramid complex. Apart from this, there are tentative indications that Merenre had work carried out in the temple ofOsiris

Osiris (, from Egyptian ''wikt:wsjr, wsjr'') was the ancient Egyptian deities, god of fertility, agriculture, the Ancient Egyptian religion#Afterlife, afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life, and vegetation in ancient Egyptian religion. He was ...

and Khenti-Amentiu in modern-day Kom el-Sultan, near Abydos. There, fragments of several private stelae

A stele ( ) or stela ( )The plural in English is sometimes stelai ( ) based on direct transliteration of the Greek, sometimes stelae or stelæ ( ) based on the inflection of Greek nouns in Latin, and sometimes anglicized to steles ( ) or stela ...

dating to his reign were uncovered in the temple's foundations, which was completely renovated in the 12th dynasty

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is a series of rulers reigning from 1991–1802 BC (190 years), at what is often considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom (Dynasties XI–XIV). The dynasty periodically expanded its terr ...

(). The nature and extent of the works undertaken at the time cannot be fully ascertained; possibly Merenre had a Ka-chapel built there following his father who built such chapels extensively throughout Egypt.

End of reign

A second co-regency between Merenre and Pepi II has been proposed by Stevenson Smith following the discovery of a cylinder seal inTell el-Maskhuta

Pithom (; ; or , and ) was an ancient city of Egypt. References in the Hebrew Bible and ancient Greek and Roman sources exist for this city, but its exact location remains somewhat uncertain. Some scholars identified it as the later archaeol ...

. The seal, belonging to an administrative official, is inscribed with "the King of Upper and Lower Egypt Merenre, living forever like Re" and shows the king smiting an enemy and the Horus name

The Horus name is the oldest known and used crest of ancient Egyptian rulers. It belongs to the " great five names" of an Egyptian pharaoh. However, modern Egyptologists and linguists are starting to prefer the more neutral term "serekh name". T ...

s of both Merenre and Pepi II in serekh

In Egyptian hieroglyphs, a serekh is a rectangular enclosure representing the niched or gated façade of a palace surmounted by (usually) the Horus falcon, indicating that the text enclosed is a royal name. The serekh was the earliest conven ...

s facing one another. This evidence for a shared reign is circumstantial and could equally well indicate that the official meant to convey that he served in the army under both kings, or that the kings were close kin. Given Pepi II's youth on acceding to the throne and Merenre's likely short reign, William J. Murnane and others after him including Anthony Spalinger and Nigel Strudwick have rejected the idea of a co-regency between the two rulers. In contrast for Miroslav Bárta the possibility of this co-regency cannot be excluded.

Foreign activities

Eastern Desert and Levant

Merenre sent at least one mining expedition toWadi Hammamat

Wadi Hammamat (, ) is a dry river bed in Egypt's Eastern Desert, about halfway between Al-Qusayr and Qena. It was a major mining region and trade route east from the Nile Valley in ancient times, and three thousand years of rock carvings and ...

in the Eastern Desert

The Eastern Desert (known archaically as Arabia or the Arabian Desert) is the part of the Sahara Desert that is located east of the Nile River. It spans of northeastern Africa and is bordered by the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea to the east, a ...

to collect greywacke

Greywacke or graywacke ( ) is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness (6–7 on Mohs scale), dark color, and Sorting (sediment), poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or sand-size Lith ...

and siltstone

Siltstone, also known as aleurolite, is a clastic sedimentary rock that is composed mostly of silt. It is a form of mudrock with a low clay mineral content, which can be distinguished from shale by its lack of fissility.

Although its permeabil ...

. Weni, who began his career under Teti, rose through the ranks of the administration under Pepi I was the leader of this expedition and reported its goal:

The expedition left two inscriptions in the Wadi, indicating that it took place on the year of the second cattle count, probably Merenre's fourth year on the throne.

Alabaster

Alabaster is a mineral and a soft Rock (geology), rock used for carvings and as a source of plaster powder. Archaeologists, geologists, and the stone industry have different definitions for the word ''alabaster''. In archaeology, the term ''alab ...

was extracted from Hatnub, also in the Eastern Desert, a location where an expedition under the leadership of Weni was tasked with the quarrying of a very large travertine

Travertine ( ) is a form of terrestrial limestone deposited around mineral springs, especially hot springs. It often has a fibrous or concentric appearance and exists in white, tan, cream-colored, and rusty varieties. It is formed by a process ...

altar stone for the pyramid of Merenre:

While there is no direct evidence for Egyptian activity in Sinai specifically during Merenre's reign, frequent expeditions were sent in the region for turquoise

Turquoise is an opaque, blue-to-green mineral that is a hydrous phosphate of copper and aluminium, with the chemical formula . It is rare and valuable in finer grades and has been prized as a gemstone for millennia due to its hue.

The robi ...

and other resources during the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties. Egypt in all probability maintained diplomatic and trade relations with Byblos

Byblos ( ; ), also known as Jebeil, Jbeil or Jubayl (, Lebanese Arabic, locally ), is an ancient city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. The area is believed to have been first settled between 8800 and 7000BC and continuously inhabited ...

to procure cedar

Cedar may refer to:

Trees and plants

*''Cedrus'', common English name cedar, an Old-World genus of coniferous trees in the plant family Pinaceae

* Cedar (plant), a list of trees and plants known as cedar

Places United States

* Cedar, Arizona

...

wood, and with Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

and the wider Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

—then in the Early Bronze Age IV to Middle Bronze Age I period—as witnessed by imported jars found in the tombs of Idi and Weni. Further abroad, the high official Iny, who served under Pepi I, Merenre and Pepi II, either led or participated in a sea-borne mission to Syria-Palestine, possibly during Merenre's rule, to obtain lapis lazuli

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color. Originating from the Persian word for the gem, ''lāžward'', lapis lazuli is ...

, silver, bitumen

Bitumen ( , ) is an immensely viscosity, viscous constituent of petroleum. Depending on its exact composition, it can be a sticky, black liquid or an apparently solid mass that behaves as a liquid over very large time scales. In American Engl ...

and lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

or tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

. In addition, a possible military campaign in the southern Levant which Weni may have conducted under Pepi I shows the continuing interest in those regions to the east and northeast of the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

on behalf of the Egyptian state at the time.

Nubia

During Merenre's reign

During Merenre's reign Lower Nubia

Lower Nubia (also called Wawat) is the northernmost part of Nubia, roughly contiguous with the modern Lake Nasser, which submerged the historical region in the 1960s with the construction of the Aswan High Dam. Many ancient Lower Nubian monuments, ...

was the focus of Egypt's foreign policy interests. Two rock reliefs depict the king receiving the submission of Nubian chieftains, the earlier of which, located on the ancient route from Aswan to Philae

The Philae temple complex (; , , Egyptian: ''p3-jw-rķ' or 'pA-jw-rq''; , ) is an island-based temple complex in the reservoir of the Aswan Low Dam, downstream of the Aswan Dam and Lake Nasser, Egypt.

Originally, the temple complex was ...

near the First Cataract, shows Merenre standing on the symbol for the union of the two lands, suggesting that it was carved during his first year of reign. Toward the end of the Old Kingdom period, Nubia saw the arrival of the C-Group people from the south. Centred at Kerma

Kerma was the capital city of the Kerma culture, which was founded in present-day Sudan before 3500 BC. Kerma is one of the largest archaeological sites in ancient Nubia. It has produced decades of extensive excavations and research, including t ...

, they struggled intermittently with Egypt and its allies over control of the region which, for the Egyptians, was a source of incense, ebony

Ebony is a dense black/brown hardwood, coming from several species in the genus '' Diospyros'', which also includes the persimmon tree. A few ''Diospyros'' species, such as macassar and mun ebony, are dense enough to sink in water. Ebony is fin ...

, animal skins, ivory and exotic animals. Three Egyptian hosts were sent in expeditions by Merenre to procure luxury goods from Lower Nubia, where tribes had united to form a state, into the , possibly modern-day Dongola

Dongola (), also known as Urdu or New Dongola, is the capital of Northern State in Sudan, on the banks of the Nile. It should not be confused with Old Dongola, a now deserted medieval city located 80 km upstream on the opposite bank.

Et ...

or Shendi

Shendi or Shandi () is a small city in northern Sudan, situated on the southeastern bank of the Nile River 150 km northeast of Khartoum. Shandi is also about 45 km southwest of the ancient city of Meroë. Located in the River Nile s ...

.

These expeditions took place under the direction of the caravan conductor and later nomarch of Elephantine Harkhuf. He claimed to have pacified the land South of Egypt but his expeditions likely constituted a labour force and a traders' caravan above all. The aim of such expeditions was first and foremost to exploit resources the locals would not or could not use, and only rarely did they have to fight.

The first expedition, during which Harkhuf was accompanied by his father the lector priest

A lector priest was a priest in ancient Egypt who recited spells and hymns during temple rituals and official ceremonies. Such priests also sold their services to laymen, reciting texts during private apotropaic rituals or at funerals.Ritner, Rob ...

Iri, lasted for seven months while the second took eight months. On the third expedition, which took place at the end of Merenre's reign or early in Pepi II's, Harkhuf was informed that the king of Yam had gone to war against the Tjemehu people, possibly Libyans or people to the west of Nubia. He consequently either joined his forces with those of Yam, in order to defeat their adversaries and gain riches; or he caught up with the king of Yam to prevent the outbreak of hostilities. The ruler of Irtjet, Setju and Wawat might have further threatened to interfere with Harkhuf's return to Egypt but changed stance, offering cattle and goats to Harkhuf. This was possibly after he had received gifts or because of Harkhuf's strong escort. At any rate, Harkhuf went to great length to explain to the king his unexpected delays as the duration of these expeditions was a matter of pride to him. He was greeted in return by an envoy from the court bringing date-wine, cakes, bread, and beer.

Such expeditions, each of which represented a round-trip journey, took the form of large caravans of donkeys. The third one led by Harkhuf numbered three hundred asses carrying various goods including incense, ebony and grain in large storage jars. To meet the demands of trade within Egypt and outside of Egypt for pack animals, donkeys were raised in large numbers in Egypt since at least the Fourth Dynasty.

In the year of the fifth cattle count since the beginning of his reign, Merenre travelled south to Elephantine from his capital to receive the submission of Nubian chieftains. This is indicated by an inscription and relief located opposite the cataract island of El-Hesseh near Philae:

On the same occasion, Merenre might also have visited the temple of Satet on Elephantine island to renew a naos erected by Pepi I. This is suggested by another inscription of Merenre on the rock face of a natural grotto in a niche of the temple:

Besides Harkhuf, another Egyptian high official who was active in Nubia at the time was Weni, who had been promoted to commander of the army by Pepi I. As such Weni hired Nubian mercenaries for his military campaigns in Sinai and the Levant, mercenaries which were also frequently employed as police force. Weni was also tasked with bringing back from Elephantine to Memphis a

In the year of the fifth cattle count since the beginning of his reign, Merenre travelled south to Elephantine from his capital to receive the submission of Nubian chieftains. This is indicated by an inscription and relief located opposite the cataract island of El-Hesseh near Philae:

On the same occasion, Merenre might also have visited the temple of Satet on Elephantine island to renew a naos erected by Pepi I. This is suggested by another inscription of Merenre on the rock face of a natural grotto in a niche of the temple:

Besides Harkhuf, another Egyptian high official who was active in Nubia at the time was Weni, who had been promoted to commander of the army by Pepi I. As such Weni hired Nubian mercenaries for his military campaigns in Sinai and the Levant, mercenaries which were also frequently employed as police force. Weni was also tasked with bringing back from Elephantine to Memphis a false door

A false door, or recessed niche, is an artistic representation of a door which does not function like a real door. They can be carved in a wall or painted on it. They are a common architectural element in the tombs of ancient Egypt, but appeared p ...

of granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

and granite doorway and lintels for the upper chamber of the pyramid complex of Merenre. He did so, sailing down-stream with six cargo-boats, three tow boats and one warship, finally mooring by the pyramid. The tow-boats were large barges capable of transporting heavy loads; Weni's biography gives their dimensions as in length and -wide. Overall, Egyptian activities in Lower Nubia were sufficiently important that Weni was directed to oversee the excavation of a five-channels canal near modern-day Shellal. The canal ran parallel to the Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

, in order to facilitate the navigation of the First Cataract. On the same occasion, Weni had seven boats of acacia

''Acacia'', commonly known as wattles or acacias, is a genus of about of shrubs and trees in the subfamily Mimosoideae of the pea family Fabaceae. Initially, it comprised a group of plant species native to Africa, South America, and Austral ...

built from timber he had received from Nubian chieftains.

Pyramid complex

Main pyramid

Thepyramid of Merenre

The Pyramid of Merenre was constructed for Merenre Nemtyemsaf I during the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt at Saqqara to the south-west of the pyramid of Pepi I and a similar distance to the pyramid of Djedkare.Kinnaer, Jacques"The Pyramid of Merenre I ...

was built at South Saqqara. The Ancient Egyptians named it ''Khanefermerenre'', which is variously translated as "Merenre appears in glory and is beautiful", "The perfection of Merenre rises", "The appearance of the perfection of Merenre", and "Merenre appears and is beautiful". The pyramid is located to the south-west of the pyramid of Pepi I

The pyramid of Pepi I (in ancient Egyptian Men-nefer-Pepi meaning Pepi's splendour is enduring) is the pyramid complex built for the Egyptian pharaoh Pepi I of the Sixth Dynasty in the 24th or 23rd century BC. The complex gave its name to the c ...

and a similar distance to the pyramid of Djedkare. The pyramid originally reached a height of 100 Egyptian cubits, , and had a square base side-length of 150 cubits, . This would give the elevation of Merenre's pyramid a hypotenuse of 125 cubits, and consequently an elevation (slope) in the same proportion as Khafre's pyramid at Giza. The triangle formed by half of the base, the height, and the hypotenuse (75, 100, 125 cubits)form a Pythagorean Triple, reduceable to proportions of 3,4,5. It may have been accessed via a causeway starting from a harbour located on the nearby Wadi Tafla, some away, but also below. Fine limestone for the pyramid was quarried in Tura, the quarries being administered from Saqqara or Memphis.

The inner passages of the pyramid were laid out according to those found in Djedkare Isesi's pyramid. They are inscribed with the Pyramid Texts

The Pyramid Texts are the oldest ancient Egyptian funerary texts, dating to the late Old Kingdom. They are the earliest known corpus of ancient Egyptian religious texts. Written in Old Egyptian, the pyramid texts were carved onto the subterranea ...

. Discovered by the Egyptologist Gaston Maspero

Sir Gaston Camille Charles Maspero (23 June 1846 – 30 June 1916) was a French Egyptologist and director general of excavations and antiquities for the Egyptian government. Widely regarded as the foremost Egyptologist of his generation, he be ...

at the end of the nineteenth century, the texts of the pyramid of Merenre were only published in full in 2019 by the Egyptologist Isabelle Pierre-Croisiau. The north wall of the burial chamber, now completely ruined, bore offering ritual formulae which continued onto the east wall, as is the case in the pyramids of Unas

Unas or Wenis, also spelled Unis (, Hellenization, hellenized form Oenas or Onnos; died 2345), was a pharaoh, king, the ninth and last ruler of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt during the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom. Unas reigned for 15 to 3 ...

, Teti and Pepi I. The Pyramid Texts are made of hundreds of utterances organised in groups of inscriptions, yet in different copies the utterances could be in varying position within a group and exchanged between groups. This reveals some editorial dynamism in the composition of the rites they represent. The south and west wall of the burial chamber of Merenre bear texts concerning the transfiguration of the king.

On the east wall are utterances calling for the perpetuation of the cult of the deceased ruler, while two further groups of texts on the resurrection of Horus

Horus (), also known as Heru, Har, Her, or Hor () in Egyptian language, Ancient Egyptian, is one of the most significant ancient Egyptian deities who served many functions, most notably as the god of kingship, healing, protection, the sun, and t ...

and the protection of Nut are found on the opposite wall. The rest of the texts found in the burial chamber pertain to the anointing and wrapping of the king, his provisioning, summons by Isis

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom () as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her sla ...

and Nephthys

Nephthys or Nebet-Het in ancient Egyptian () was a goddess in ancient Egyptian religion. A member of the Great Ennead of Heliopolis in Egyptian mythology, she was a daughter of Nut and Geb. Nephthys was typically paired with her sister Isis ...

, and the ascent to the sky. Leading out of the sarcophagus chamber, the walls of the antechamber bear texts calling for the king's joining the company of the gods and apotropaic

Apotropaic magic (From ) or protective magic is a type of magic intended to turn away harm or evil influences, as in deflecting misfortune or averting the evil eye. Apotropaic observances may also be practiced out of superstition or out of tr ...

formulae. The remaining corridors and vestibules of the tomb bear utterances on the celestial circuit of the king and gods.

Mortuary temple

The pyramid of Merenre is surrounded by a wider mortuary complex, its offering chapel located on the north face of the pyramid. Fragments of reliefs showing the gods greeting the king in the afterlife have been uncovered there. The hall of the chapel is paved with limestone. Further on stands the base of a granite false-door. Some of the decoration of the complex was left unfinished, as work likely stopped at the death of the king.Mummy

In 1881, the Egyptologists Émile and

In 1881, the Egyptologists Émile and Heinrich Brugsch

Heinrich Karl Brugsch (also ''Brugsch-Pasha'') (18 February 18279 September 1894) was a German Egyptologist. He was associated with Auguste Mariette in his excavations at Memphis. He became director of the School of Egyptology at Cairo, producin ...

managed to enter the burial chamber of Merenre's pyramid via a robber's tunnel. They found its massive ceiling beams of limestone hanging dangerously as the lower retaining walls of the chamber had been removed by stone robbers. The black basalt sarcophagus was still intact, its lid pushed back, and in it lay the mummy of a -tall man. The mummy was in a poor condition because ancient tomb robbers had partially torn off its wrappings. The Brugsch brothers decided to transport the mummy to Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

, in order to show it to Auguste Mariette

François Auguste Ferdinand Mariette (11 February 182118 January 1881) was a French scholar, archaeologist and Egyptologist, and the founder of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities, the forerunner of the Supreme Council of Antiquities.

Earl ...

, head of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities and by then dying. During the transport, the mummy suffered further damage: problems with the railroads prevented the mummy from being taken to Cairo by train and the Brugschs took the decision to carry it on foot. After the wooden sarcophagus employed to that end had become too heavy, they took out the mummy and broke it into two pieces. The mummy was first housed in the various incarnations of the Egyptian Museum

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, commonly known as the Egyptian Museum (, Egyptian Arabic: ) (also called the Cairo Museum), located in Cairo, Egypt, houses the largest collection of Ancient Egypt, Egyptian antiquities in the world. It hou ...

in Cairo, until moved to the Imhotep Museum at Saqqara in 2006. Émile Brugsch donated some fragments, a collarbone, cervical vertebrae and a rib to the Egyptian Museum of Berlin

The Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection of Berlin () is home to one of the world's most important collections of ancient Egyptian artefacts, including the Nefertiti Bust. Since 1855, the collection is a part of the Neues Museum on Berlin's ...

. These have not been located since World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Preliminary forensic analyses of the mummy by Grafton Smith indicate that it is that of a young man, as suggested by possible traces of a sidelock of youth. The identity of the mummy remains uncertain as Elliot Smith observed that the technique employed for the wrapping was typical of the Eighteenth Dynasty

The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XVIII, alternatively 18th Dynasty or Dynasty 18) is classified as the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. The Eighteenth Dynasty ...

() rather than the Sixth. Re-wrapping of older mummies is known to have occurred, so that this observation does not necessarily preclude that the mummy is that of Merenre. The mummy has not been properly studied since Elliott Smith's analyses in the early 20th century, and its identification remains uncertain.

Legacy

Old Kingdom

Like other kings of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties, Merenre was the object of an official, state-sponsored funerary cult which took place in his pyramid complex. In the mid-Sixth Dynasty, nomarchs were overseer of the priests of such cults. For instance, Qar, nomarch ofEdfu

Edfu (, , , ; also spelt Idfu, or in modern French as Edfou) is an Egyptian city, located on the west bank of the Nile River between Esna and Aswan, with a population of approximately 60,000 people. Edfu is the site of the Ptolemaic Temple of H ...

and Gegi, nomarch of the Thinite nome, were "instructor of the priests of the pyramid 'Merenre appears and is beautiful'"; Heqaib, nomarch of the first nome of Upper Egypt under Pepi II, was "leader of the phyle of the pyramid of Merenre".

Some of the priests serving the cult in the pyramid complex of Merenre are known by name, including Iarti and his son Merenreseneb; a certain Meru called Bebi; and Nipepy, who also officiated in the pyramid of Pepi I. Another piece of evidence concerning this cult comes from a decree of Pepi II exempting people living in the pyramid town of Merenre from tax or corvée. A fragmentary papyrus letter from a certain Ankhpepy, inspector of the royal granary at the pyramid town of Merenre, further confirms its existence and prosperity at the time of Merenre's and Pepi II's reigns:

A few priests serving the funerary cult of Merenre during the later Sixth Dynasty are known; for example the priest Idu Seneni served in both Merenre's and Pepi II's pyramids. The cult was active even outside of Merenre's mortuary temple at Saqqara: inscriptions in Elkab