Macedonia Region on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Macedonia ( ) is a

The definition of Macedonia has changed several times throughout history. Prior to its expansion under

The definition of Macedonia has changed several times throughout history. Prior to its expansion under

File:Ethnographische Karte von Makedonien (1899).jpg, Distribution of ethnic groups in Macedonia in 1892 (''Deutsche Rundschau für Geographie und Statistik'' – ''German Bevieiofor Geography and Statistics'')

File:Ethnographic map of the central Balkans, ca. 1900.png, Ethnographic map of the vilayets of Kosovo, Saloniki, Scutari, Janina and Monastir, ca. 1900 (''Institute and Museum of Military History'')

File:Distribution of races in the Balkans c.1910.jpg, Distribution of ethnic groups in the Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor in 1910 (''Historical Atlas'' by William R. Shepherd, New York)

File:Distribution Of Races 1918 National Geographic.jpg, Distribution of ethnic groups in the Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor in 1918 (''National Geographic'')

Most present-day inhabitants of the region are

Most present-day inhabitants of the region are

In classical times, the region of Macedonia comprised parts of what at the time was known as Macedonia, Illyria and Thrace. Among others, in its lands were located the kingdoms of Paeonia, Dardania, Macedonia and Pelagonia, historical tribes like the Agrianes, and colonies of southern Greek city states. Prior to the Macedonian ascendancy, parts of southern Macedonia were populated by the

In classical times, the region of Macedonia comprised parts of what at the time was known as Macedonia, Illyria and Thrace. Among others, in its lands were located the kingdoms of Paeonia, Dardania, Macedonia and Pelagonia, historical tribes like the Agrianes, and colonies of southern Greek city states. Prior to the Macedonian ascendancy, parts of southern Macedonia were populated by the

Since the middle of the 14th century, the Ottoman threat was looming in the Balkans, as the Ottomans defeated the various Christian principalities, whether Serb, Bulgarian or Greek. After the Ottoman victory in the

Since the middle of the 14th century, the Ottoman threat was looming in the Balkans, as the Ottomans defeated the various Christian principalities, whether Serb, Bulgarian or Greek. After the Ottoman victory in the

From a letter of Georgi Gogov, Voden, to G.S. Rakovski, Belgrade, regarding the abuses perpetrated by the Greek bishop Nikodim and his persecution of Bulgarian patriots

Vacalopulos, Konstandinos A. Modern history of Macedonia, Thessaloniki 1988, pp. 52, 57, 64 Eventually, in the 20th century, 'Bulgarians' came to be understood as synonymous with 'Macedonian Slavs' and, eventually, 'ethnic Macedonians'.  The 1878

The 1878  Baptizing Macedonian Slavs as Serbian or Bulgarian aimed therefore to justify these countries' territorial claims over Macedonia. The Greek side, with the assistance of the Patriarchate that was responsible for the schools, could more easily maintain control, because they were spreading Greek identity. For the very same reason the Bulgarians, when preparing the Exarchate's government (1871) included Macedonians in the assembly as "brothers" to prevent any ethnic diversification. On the other hand, the Serbs, unable to establish Serbian-speaking schools, used propaganda. Their main concern was to prevent the Slavic-speaking Macedonians from acquiring Bulgarian identity through concentrating on the myth of the ancient origins of the Macedonians and simultaneously by the classification of Bulgarians as Tatars and not as Slavs, emphasizing their 'Macedonian' characteristics as an intermediate stage between Serbs and Bulgarians. To sum up the Serbian propaganda attempted to inspire the Macedonians with a separate ethnic identity to diminish the Bulgarian influence. This choice was the 'Macedonian ethnicity'. The Bulgarians never accepted an ethnic diversity from the Slav Macedonians, giving geographic meaning to the term. In 1893 they established the

Baptizing Macedonian Slavs as Serbian or Bulgarian aimed therefore to justify these countries' territorial claims over Macedonia. The Greek side, with the assistance of the Patriarchate that was responsible for the schools, could more easily maintain control, because they were spreading Greek identity. For the very same reason the Bulgarians, when preparing the Exarchate's government (1871) included Macedonians in the assembly as "brothers" to prevent any ethnic diversification. On the other hand, the Serbs, unable to establish Serbian-speaking schools, used propaganda. Their main concern was to prevent the Slavic-speaking Macedonians from acquiring Bulgarian identity through concentrating on the myth of the ancient origins of the Macedonians and simultaneously by the classification of Bulgarians as Tatars and not as Slavs, emphasizing their 'Macedonian' characteristics as an intermediate stage between Serbs and Bulgarians. To sum up the Serbian propaganda attempted to inspire the Macedonians with a separate ethnic identity to diminish the Bulgarian influence. This choice was the 'Macedonian ethnicity'. The Bulgarians never accepted an ethnic diversity from the Slav Macedonians, giving geographic meaning to the term. In 1893 they established the  The rise of the Albanian and the Turkish nationalism after 1908, however, prompted Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria to bury their differences with regard to Macedonia and to form a joint coalition against the

The rise of the Albanian and the Turkish nationalism after 1908, however, prompted Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria to bury their differences with regard to Macedonia and to form a joint coalition against the  In June 1913, Bulgarian Tsar

In June 1913, Bulgarian Tsar

geographical

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

and historical

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some theorists categ ...

region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as areas, zones, lands or territories, are portions of the Earth's surface that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and ...

of the Balkan Peninsula

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

in Southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe is a geographical sub-region of Europe, consisting primarily of the region of the Balkans, as well as adjacent regions and Archipelago, archipelagos. There are overlapping and conflicting definitions of t ...

. Its boundaries have changed considerably over time; however, it came to be defined as the modern geographical region by the mid-19th century. Today the region is considered to include parts of six Balkan countries: all of North Macedonia

North Macedonia, officially the Republic of North Macedonia, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe. It shares land borders with Greece to the south, Albania to the west, Bulgaria to the east, Kosovo to the northwest and Serbia to the n ...

, large parts of Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

and Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, and smaller parts of Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

, Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

, and Kosovo

Kosovo, officially the Republic of Kosovo, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe with International recognition of Kosovo, partial diplomatic recognition. It is bordered by Albania to the southwest, Montenegro to the west, Serbia to the ...

. It covers approximately and has a population of around five million. Greek Macedonia

Macedonia ( ; , ) is a geographic and former administrative region of Greece, in the southern Balkans. Macedonia is the largest and geographic region in Greece, with a population of 2.36 million (as of 2020). It is highly mountainous, wit ...

comprises about half of Macedonia's area and population.

Its oldest known settlements date back approximately to 7,000 BC. From the middle of the 4th century BC, the Kingdom of Macedon

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchic state or realm ruled by a king or queen.

** A monarchic chiefdom, represented or governed by a king or queen.

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and me ...

became the dominant power on the Balkan Peninsula; since then Macedonia has had a diverse history.

Etymology

Bothproper noun

A proper noun is a noun that identifies a single entity and is used to refer to that entity ('' Africa''; ''Jupiter''; '' Sarah''; ''Walmart'') as distinguished from a common noun, which is a noun that refers to a class of entities (''continent, ...

s ''Makedṓn'' and ''Makednós'' are morphologically derived from the Ancient Greek adjective ''makednós'' meaning "tall, slim", and are related to the term Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

.

Boundaries and definitions

Ancient times

The definition of Macedonia has changed several times throughout history. Prior to its expansion under

The definition of Macedonia has changed several times throughout history. Prior to its expansion under Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

, the ancient kingdom of Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

, to which the modern region owes its name, lay entirely within the central and western parts of the current Greek province of Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

and consisted of 17 provinces/districts or eparchies (Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

: επαρχία).

Expansion of Kingdom of Macedon:

# Kingdom of Perdiccas I: Macedonian Kingdom of Emathia consisting of six provinces Emathia, Pieria, Bottiaea

Bottiaea (Greek: ''Bottiaia'') was a geographical region of ancient Macedonia and an administrative district of the Macedonian Kingdom. It was previously inhabited by the Bottiaeans, a people of uncertain origin, later expelled by the Macedon ...

, Mygdonia

Mygdonia (; ) was an ancient territory, part of ancient Thrace, later conquered by Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon, which comprised the plains around Therma (Thessalonica) together with the valleys of Klisali and Besikia, including the ar ...

, Eordaea

Eordaea (also spelled Eordaia or Eordia, ) was a geographical region of upper Macedonia and later an administrative region of the kingdom of Macedon. Eordaea was located south of Lynkestis, west of Emathia, north of Elimiotis and east of ...

and Almopia

Almopia (), or Enotia (Greek: Ενωτία), also known in the Middle Ages as Moglena (Greek: Μογλενά, Macedonian and Bulgarian: Меглен or Мъглен), is a municipality and a former province (επαρχία) of the Pella regional ...

.

# Kingdom of Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon from 495 to 454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Alexander I Theopator Euergetes, surnamed Balas, ruler of the Seleucid Empire 150-145 BC

* Pope Alex ...

: All the above provinces plus the eastern annexations Crestonia

Crestonia (or Crestonice) () was an ancient region immediately north of Mygdonia. The Echeidorus river, which flowed through Mygdonia into the Thermaic Gulf, had its source in Crestonia. It was partly occupied by a remnant of the Pelasgi, who spo ...

, Bisaltia and the western annexations Elimiotis

Elimiotis or Elimeia () was a region of Upper Macedonia that was located along the Haliacmon river. The capital of Elimiotis was Aiani, located in the modern municipality of Kozani, Western Macedonia. It was bordered by Orestis and Eordaea ...

, Orestis and Lynkestis

Lynkestis, Lyncestis, Lyngistis, Lynkos or Lyncus ( or Λύγκος or ''Lyncus'') was a region and principality traditionally located in Upper Macedonia. It was the northernmost mountainous region of Upper Macedonia, located east of the Presp ...

.

# Kingdom of Philip II: All the above provinces plus the appendages of Pelagonia

Pelagonia (; ) is a geographical region of Macedonia named after the ancient kingdom. Ancient Pelagonia roughly corresponded to the present-day municipalities of Bitola, Prilep, Mogila, Novaci, Kruševo, and Krivogaštani in North Macedo ...

and Macedonian Paeonia to the north, Sintike, Odomantis and Edonis to the east and the Chalkidike to the south.

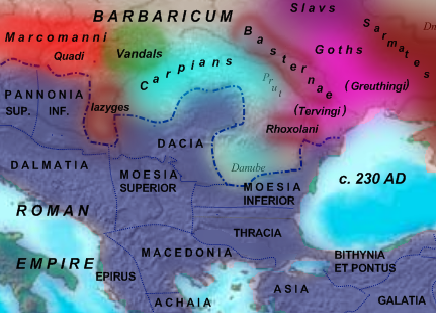

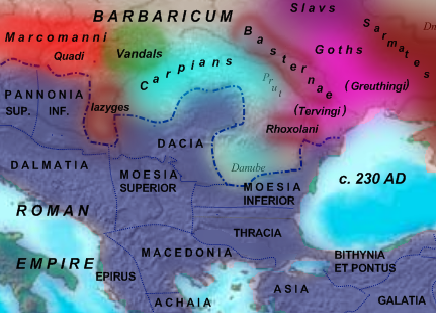

Roman era

In the 2nd century, Macedonia covered approximately the area where it is considered to be today, but the northern regions of today Republic of North Macedonia were not identified as Macedonian lands. For reasons that are still unclear, over the next eleven centuries Macedonia's location was changed significantly. The Roman province of Macedonia consisted of what is today Northern and Central Greece, much of the geographical area of the Republic of North Macedonia and southeast Albania. Simply put, the Romans created a much larger administrative area under that name than the original ancientMacedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

. In late Roman times, the provincial boundaries were reorganized to form the Diocese of Macedonia

The Diocese of Macedonia (; ) was a diocese of the later Roman Empire, forming part of the praetorian prefecture of Illyricum. Its administrative centre was Thessalonica.

History

The diocese was formed, probably under Constantine I (r. 306–337 ...

, consisting of most of modern mainland Greece right across the Aegean to include Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, southern Albania, southwest Bulgaria, and most of Republic of North Macedonia.

Byzantine era

In the Byzantine Empire, a province under the name of Macedonia was carved out of the original Theme of Thrace, which was well east of the Struma River. This '' thema'' variously included parts ofThrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

and gave its name to the Macedonian dynasty

The Macedonian dynasty () Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty, ruled the Byzantine Empire from 867 to 1056, following the Byzantium under the Amorian dynasty, Amorian dynasty. During this period, the Byzantine state reached its greates ...

. Hence, Byzantine documents of this era that mention Macedonia are most probably referring to the Macedonian thema. The region of Macedonia, on the other hand, which was ruled by the First Bulgarian Empire

The First Bulgarian Empire (; was a medieval state that existed in Southeastern Europe between the 7th and 11th centuries AD. It was founded in 680–681 after part of the Bulgars, led by Asparuh of Bulgaria, Asparuh, moved south to the northe ...

throughout the 9th and the 10th century, was incorporated into the Byzantine Empire in 1018 as the Themе of Bulgaria.

Ottoman era

With the gradual conquest of southeastern Europe by theOttomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

in the late 14th century, the name of Macedonia disappeared as an administrative designation for several centuries and was rarely displayed on maps. The name was again revived to mean a distinct geographical region in the 19th century, defining the region bounded by Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (, , ) is an extensive massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia, between the regional units of Larissa (regional unit), Larissa and Pieria (regional ...

, the Pindus

The Pindus (also Pindos or Pindhos; ; ; ) is a mountain range located in Northern Greece and Southern Albania. It is roughly long, with a maximum elevation of (Smolikas, Mount Smolikas). Because it runs along the border of Thessaly and Epiru ...

range, mounts Shar and Osogovo, the western Rhodopes, the lower course of the river Mesta (Greek Nestos) and the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

, developing roughly the same borders that it has today.

Demographics

During medieval and modern times, Macedonia has been known as a Balkan region inhabited by many ethnic groups. Today, as a frontier region where several very different cultures meet, Macedonia has an extremely diverse demographic profile. The current demographics of Macedonia include: * Macedonian Greeks self-identify culturally and regionally as "Macedonians" (Greek: Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes''). They form the majority of the region's population (~51%). They number approximately 2,500,000 and, today, they live almost entirely inGreek Macedonia

Macedonia ( ; , ) is a geographic and former administrative region of Greece, in the southern Balkans. Macedonia is the largest and geographic region in Greece, with a population of 2.36 million (as of 2020). It is highly mountainous, wit ...

. The Greek Macedonian population is mixed, with other indigenous groups and with a large influx of Greek refugees descending from Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks (; or ; , , ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group indigenous to the region of Pontus, in northeastern Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). They share a common Pontic Greek culture that is di ...

, and East Thracian Greeks in the early 20th century. This is due to the population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at Lausanne, Switzerland, on 30 January 1923, by the governments of Greece and Turkey. It involv ...

, during which over 1.2 million Anatolian Greek refugees replaced departing Turks and settled in Greece, including 638,000 in the Greek province of Macedonia. Smaller Greek minorities exist in Bulgaria and the Republic of North Macedonia, although their numbers are difficult to ascertain. In official census results, only 86 persons declared themselves Greeks in Bulgarian Macedonia (Blagoevgrad Province) in 2011, out of a total of 1,379 in all of Bulgaria; while only 294 persons described themselves as Greeks in the 2021 census in the Republic of North Macedonia.

* Ethnic Macedonians

Macedonians ( ) are a nation and a South Slavic ethnic group native to the region of Macedonia in Southeast Europe. They speak Macedonian, a South Slavic language. The large majority of Macedonians identify as Eastern Orthodox Christians, ...

self-identify as "Macedonians" (Macedonian: Македонци, ''Makedonci'') in an ethnic sense as well as in the regional sense. They are the second largest ethnic group in the region. Being a South Slavic ethnic group

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

they are also known as "Macedonian Slavs" and "Slav Macedonians" (Greek: Σλαβομακεδόνες, "Slavomakedones") in Greece, though this term can be viewed as derogatory by ethnic Macedonians, including those in Greek Macedonia

Macedonia ( ; , ) is a geographic and former administrative region of Greece, in the southern Balkans. Macedonia is the largest and geographic region in Greece, with a population of 2.36 million (as of 2020). It is highly mountainous, wit ...

. They form the majority of the population in the Republic of North Macedonia

North Macedonia, officially the Republic of North Macedonia, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe. It shares land borders with Greece to the south, Albania to the west, Bulgaria to the east, Kosovo to the northwest and Serbia to the n ...

where according to the 2021 census, approximately 1,100,000 people declared themselves as Macedonians. In 1999, the Greek Helsinki Monitor estimated a significant minority of ethnic Macedonians ranging from 10,000 to 30,000 that exist among the Slavic-speakers of Greek Macedonia. There has not been a census in Greece on the question of mother tongue since 1951, when the census recorded 41,017 Slavic-speakers, mostly in the West Macedonia periphery of Greece. The linguistic classification of the Slavic dialects spoken by these people are nowadays typically classified as Macedonian, with the exception of some eastern dialects which can also be classified as Bulgarian, although the people themselves call their native language a variety of terms, including ''makedonski'', ''makedoniski'' ("Macedonian"), ''slaviká'' (, "Slavic"), ''dópia'' or ''entópia'' (, "local/indigenous anguage), ''balgàrtzki'', ''bògartski'' ("Bulgarian") along with ''naši'' ("our own") and ''stariski'' ("old"). Most Slavic-speakers declare themselves as ethnic Greeks ( Slavophone Greeks), although there are small groups espousing ethnic Macedonian"Northwestern Greece is home to an indeterminate number of citizens who speak a Slavic dialect at home, particularly in Florina province. Estimates ranged widely, from under 10,000 to 50,000. A small number identified themselves as belonging to a distinct ethnic group and asserted their right to "Macedonian" minority status" and Bulgarian national identities, however some groups reject all these ethnic designations and prefer terms such as ''"natives"'' instead. The Macedonian minority in Albania are an officially recognised minority in Albania and are primarily concentrated around the Prespa region and Golo Brdo and are primarily Eastern Orthodox Christian

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

with the exception of the later region where Macedonians are predominantly Muslim. In the 2011 Albanian census, 5,870 Albanian citizens declared themselves Macedonians. According to the latest Bulgarian census held in 2011, there are 561 people declaring themselves ethnic Macedonians in the Blagoevgrad Province

Blagoevgrad Province (, ''oblast Blagoevgrad'' or Благоевградска област, ''Blagoevgradska oblast''), also known as Pirin Macedonia or Bulgarian Macedonia (), (''Pirinska Makedoniya or Bulgarska Makedoniya'') is a province ('' ...

of Bulgaria (Pirin Macedonia

Pirin Macedonia or Bulgarian Macedonia () (''Pirinska Makedoniya or Bulgarska Makedoniya''), which today is in southwestern Bulgaria, is the third-biggest part of the geographical region of Macedonia. This part coincides with the borders of Blag ...

). The official number of ethnic Macedonians in Bulgaria is 1,654.

* Macedonian Bulgarians

Macedonians or Macedonian Bulgarians (), sometimes also referred to as Macedono-Bulgarians, Macedo-Bulgarians, or Bulgaro-Macedonians are a regional, ethnographic group of ethnic Bulgarians, inhabiting or originating from the region of Ma ...

are ethnic Bulgarians who self-identify regionally as "Macedonians" (Bulgarian: Mакедонци, ''Makedontsi''). They represent the bulk of the population of Bulgarian Macedonia (also known as "Pirin Macedonia

Pirin Macedonia or Bulgarian Macedonia () (''Pirinska Makedoniya or Bulgarska Makedoniya''), which today is in southwestern Bulgaria, is the third-biggest part of the geographical region of Macedonia. This part coincides with the borders of Blag ...

"). They number approximately 250,000 in the Blagoevgrad Province

Blagoevgrad Province (, ''oblast Blagoevgrad'' or Благоевградска област, ''Blagoevgradska oblast''), also known as Pirin Macedonia or Bulgarian Macedonia (), (''Pirinska Makedoniya or Bulgarska Makedoniya'') is a province ('' ...

where they are mainly situated. There are small Bulgarian-identifying groups in Albania, Greece and the Republic of North Macedonia. In the Republic of North Macedonia, 3,504 people claimed a Bulgarian ethnic identity in the 2021 census.

* Albanians

The Albanians are an ethnic group native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, Albanian culture, culture, Albanian history, history and Albanian language, language. They are the main ethnic group of Albania and Kosovo, ...

are another major ethnic group in the region. Ethnic Albanians make up the majority in certain northern and western parts of the Republic of North Macedonia, and account for 24.3% of the total population of the Republic of North Macedonia, according to the 2021 census.

* Smaller numbers of Turks, Bosniaks

The Bosniaks (, Cyrillic script, Cyrillic: Бошњаци, ; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to the Southeast European historical region of Bosnia (region), Bosnia, today part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and who sha ...

, Roma, Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of Serbia, history, and Serbian lan ...

, Aromanians

The Aromanians () are an Ethnic groups in Europe, ethnic group native to the southern Balkans who speak Aromanian language, Aromanian, an Eastern Romance language. They traditionally live in central and southern Albania, south-western Bulgari ...

, Megleno-Romanians

The Megleno-Romanians, also known as Meglenites (), Moglenite Vlachs or simply Vlachs (), are an Eastern Romance ethnic group, originally inhabiting seven villages in the Moglena region spanning the Pella and Kilkis regional units of Central ...

, Egyptians

Egyptians (, ; , ; ) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian identity is closely tied to Geography of Egypt, geography. The population is concentrated in the Nile Valley, a small strip of cultivable land stretchi ...

, Armenians

Armenians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the Armenian highlands of West Asia.Robert Hewsen, Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiq ...

and Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

(Sephardim

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendan ...

and Romaniotes) can also be found in Macedonia.

Religion

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

, principally of the Bulgarian Orthodox, Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Rom ...

, Macedonian Orthodox and Serbian Orthodox

The Serbian Orthodox Church ( sr-Cyrl-Latn, Српска православна црква, Srpska pravoslavna crkva) is one of the autocephalous (ecclesiastically independent) Eastern Orthodox Christian churches.

The majority of the populat ...

Churches. Notable Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

minorities are present among the Albanian, Bulgarian (Pomaks

Pomaks (; Macedonian: Помаци ; ) are Bulgarian-speaking Muslims inhabiting Bulgaria, northwestern Turkey, and northeastern Greece. The strong ethno-confessional minority in Bulgaria is recognized officially as Bulgarian Muslims by th ...

), Macedonian ( Torbeš), Bosniak

The Bosniaks (, Cyrillic script, Cyrillic: Бошњаци, ; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to the Southeast European historical region of Bosnia (region), Bosnia, today part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and who sha ...

, and Turkish populations.

During the period of classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

, main religion in the region of Macedonia was the Ancient Greek religion

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and Greek mythology, mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and Cult (religious practice), cult practices. The application of the modern concept ...

. After the Roman conquest of Macedonia, the Ancient Roman religion

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the Roman people, people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

The Romans thought of themselves as high ...

was also introduced. Many ancient religious monuments, dedicated to Greek and Roman deities are preserved in this region. During the period of Early Christianity

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the History of Christianity, historical era of the Christianity, Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Spread of Christianity, Christian ...

, ecclesiastical structure was established in the region of Macedonia, and the see of Thessaloniki became the metropolitan diocese

A metropolis, metropolitanate or metropolitan diocese is an episcopal see whose bishop is the metropolitan bishop or archbishop of an ecclesiastical province. Metropolises, historically, have been important cities in their provinces.

Eastern Ortho ...

of the Roman province of Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

. The archbishop of Thessaloniki also became the senior ecclesiastical primate of the entire Eastern Illyricum

The praetorian prefecture of Illyricum (; , also termed simply the prefecture of Illyricum) was one of four praetorian prefectures into which the Late Roman Empire was divided.

The administrative centre of the prefecture was Sirmium (375–379 ...

, and in 535 his jurisdiction was reduced to the administrative territory of the Diocese of Macedonia

The Diocese of Macedonia (; ) was a diocese of the later Roman Empire, forming part of the praetorian prefecture of Illyricum. Its administrative centre was Thessalonica.

History

The diocese was formed, probably under Constantine I (r. 306–337 ...

. Later it came under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople () is the List of ecumenical patriarchs of Constantinople, archbishop of Constantinople and (first among equals) among the heads of the several autocephalous churches that comprise the Eastern Orthodox ...

.

During the Middle Ages and up to 1767, western and northern regions of Macedonia were under the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Ohrid

The Archbishopric of Ohrid, also known as the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid

*T. Kamusella in The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe, Springer, 2008, p. 276

*Aisling Lyon, Decentralisation and the Management of Ethni ...

. Northern fringes of the region (areas surrounding Skopje

Skopje ( , ; ; , sq-definite, Shkupi) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It lies in the northern part of the country, in the Skopje Basin, Skopje Valley along the Vardar River, and is the political, economic, and cultura ...

and Tetovo

Tetovo (, ; , sq-definite, Tetova) is a city in the northwestern part of North Macedonia, built on the foothills of Šar Mountain and divided by the Pena (river), Pena River. The municipality of Tetovo covers an area of at above sea level, wit ...

) had temporary jurisdiction under the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć

Serbian Patriarchate of Peć (, ''Srpska patrijaršija u Peći''), or simply Peć Patriarchate (, ''Pećka patrijaršija''), was an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Patriarchate that existed from 1346 to 1463, and then again from 155 ...

. Both the Archbishopric of Ohrid and the Patriarchate of Peć became abolished and absorbed into the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople () is the List of ecumenical patriarchs of Constantinople, archbishop of Constantinople and (first among equals) among the heads of the several autocephalous churches that comprise the Eastern Orthodox ...

in the middle of the 18th century. During the period of Ottoman rule, a partial islamization

The spread of Islam spans almost 1,400 years. The early Muslim conquests that occurred following the death of Muhammad in 632 CE led to the creation of the caliphates, expanding over a vast geographical area; conversion to Islam was boosted ...

was also recorded. In spite of that, the Eastern Orthodox Christianity

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

remained the dominant religion of local population.

During the 19th century, religious life in the region was strongly influenced by rising national movements. Several major ethnoreligious disputes arose in the region of Macedonia, main of them being schisms between the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople () is the List of ecumenical patriarchs of Constantinople, archbishop of Constantinople and (first among equals) among the heads of the several autocephalous churches that comprise the Eastern Orthodox ...

and the newly created Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate (; ) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953.

The Exarchate (a de facto autocephaly) ...

(1872), and later between the Serbian Orthodox Church

The Serbian Orthodox Church ( sr-Cyrl-Latn, Српска православна црква, Srpska pravoslavna crkva) is one of the autocephalous (ecclesiastically independent) Eastern Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodox Eastern Orthodox Church#Constit ...

and the newly created Macedonian Orthodox Church

The Macedonian Orthodox Church – Archdiocese of Ohrid (MOC-AO; ), or simply the Macedonian Orthodox Church (MOC) or the Archdiocese of Ohrid (AO), is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church in North Macedonia. The Macedonian Orthodox Church ...

(1967).

History

Early Neolithic

While Macedonia shows signs of human habitation as old as thePaleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

period (among which is the Petralona cave with the oldest European humanoid), the earliest known settlements, such as Nea Nikomedeia in Imathia

Imathia ( ) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Macedonia, within the geographic regions of Greece, geographic region of Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia. The capital of Imathia is the ...

(today's Greek Macedonia), date back 9,000 years. The houses at Nea Nikomedeia were constructed—as were most structures throughout the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

in northern Greece—of wattle and daub

Wattle and daub is a composite material, composite building method in which a woven lattice of wooden strips called "wattle (construction), wattle" is "daubed" with a sticky material usually made of some combination of wet soil, clay, sand, and ...

on a timber frame. The cultural assemblage includes well-made pottery in simple shapes with occasional decoration in white on a red background, clay female figurines of the 'rod-headed' type known from Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

to the Danube Valley, stone axes and adzes, chert blades, and ornaments of stone including curious 'nose plugs' of uncertain function. The assemblage of associated objects differs from one house to the next, suggesting some degree of craft specialisation had already been established from the beginning of the site's history. The farming economy was based on the cultivation of cereal crops such as wheat and barley and pulses and on the herding of sheep and goats, with some cattle and pigs. Hunting played a relatively minor role in the economy. Surviving from 7000 to 5500 BCE, this Early Neolithic settlement was occupied for over a thousand years.

Middle Neolithic

The Middle Neolithic period ( to 4500 BCE) is at present best represented at Servia in theHaliacmon

The Haliacmon (, ''Aliákmonas''; formerly: , ''Aliákmon'' or ''Haliákmōn'') is the longest river flowing entirely in Greece, with a total length of . In Greece there are three rivers longer than Haliacmon: Maritsa (), Struma (Strymónas), bot ...

Valley in western Macedonia, where the typical red-on-cream pottery in the Sesklo

Sesklo (; ) is a village in Greece that is located near Volos, a city located within the municipality of Aisonia. The municipality is located within the regional unit of Magnesia that is located within the administrative region of Thessaly. ...

style emphasises the settlement's southern orientation. Pottery of this date has been found at a number of sites in Central and Eastern Macedonia but so far none has been extensively excavated.

Late Neolithic

The Late Neolithic period ( to 3500 BCE) is well represented by both excavated and unexcavated sites throughout the region (though in Eastern Macedonia levels of this period are still called Middle Neolithic according to the terminology used in the Balkans). Rapid changes in pottery styles, and the discovery of fragments of pottery showing trade with quite distant regions, indicate that society, economy and technology were all changing rapidly. Among the most important of these changes were the start of copper working, convincingly demonstrated by Renfrew to have been learnt from the cultural groups of Bulgaria and Roumania to the North. Principal excavated settlements of this period include Makryialos and Paliambela near the western shore of the Thermaic gulf, Thermi to the south ofThessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

and Sitagroi and Dikili Tas in the Drama plain. Some of these sites were densely occupied and formed large mounds (known to the local inhabitants of the region today as 'toumbas'). Others were much less densely occupied and spread for as much as a kilometer (Makryialos). Both types are found at the same time in the same districts and it is presumed that differences in social organisation are reflected by these differences in settlement organisation. Some communities were clearly concerned to protect themselves with different kinds of defensive arrangements: ditches at Makryialos and concentric walls at Paliambela. The best preserved buildings were discovered at Dikili Tas, where long timber-framed structures had been organised in rows and some had been decorated with bulls' skulls fastened to the outside of the walls and plastered over with clay.

Remarkable evidence for cult activity has been found at Promachonas-Topolnica, which straddles the Greek Bulgarian border to the north of Serres

Serres ( ) is a city in Macedonia, Greece, capital of the Serres regional unit and second largest city in the region of Central Macedonia, after Thessaloniki.

Serres is one of the administrative and economic centers of Northern Greece. The c ...

. Here a deep pit appeared to have been roofed to make a subterranean room; in it were successive layers of debris including large numbers of figurines, bulls' skulls, and pottery, including several rare and unusual shapes.

The farming economy of this period continued the practices established at the beginning of the Neolithic, although sheep and goats were less dominant among the animals than they had previously been, and the cultivation of vines (''Vitis vinifera

''Vitis vinifera'', the common grape vine, is a species of flowering plant, native to the Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean region, Central Europe, and southwestern Asia, from Morocco and Portugal north to southern Germany and east to northern ...

'') is well attested.

Only a few burials have been discovered from the whole of the Neolithic period in northern Greece and no clear pattern can be deduced. Grave offerings, however, seem to have been very limited.

Ancient Macedonia (500 to 146 BCE)

In classical times, the region of Macedonia comprised parts of what at the time was known as Macedonia, Illyria and Thrace. Among others, in its lands were located the kingdoms of Paeonia, Dardania, Macedonia and Pelagonia, historical tribes like the Agrianes, and colonies of southern Greek city states. Prior to the Macedonian ascendancy, parts of southern Macedonia were populated by the

In classical times, the region of Macedonia comprised parts of what at the time was known as Macedonia, Illyria and Thrace. Among others, in its lands were located the kingdoms of Paeonia, Dardania, Macedonia and Pelagonia, historical tribes like the Agrianes, and colonies of southern Greek city states. Prior to the Macedonian ascendancy, parts of southern Macedonia were populated by the Bryges

Bryges or Briges () is the historical name given to a people of the ancient Balkans. They are generally considered to have been related to the Phrygians, who during classical antiquity lived in western Anatolia. Both names, ''Bryges'' and ''Phryg ...

, while western, (i. e., Upper) Macedonia, was inhabited by Macedonian and Illyrian tribes. Whilst numerous wars are later recorded between the Illyrian and Macedonian Kingdoms, the Bryges might have co-existed peacefully with the Macedonians. In the time of Classical Greece

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in ancient Greece,The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the period from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C." ( Thomas R. Mar ...

, Paionia

In antiquity, Paeonia or Paionia () was the land and kingdom of the Paeonians (or Paionians; ).

The exact original boundaries of Paeonia, like the early history of its inhabitants, are obscure, but it is known that it roughly corresponds to m ...

, whose exact boundaries are obscure, originally included the whole Axius River valley and the surrounding areas, in what is now the northern part of the Greek region of Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

, most of the Republic of North Macedonia

North Macedonia, officially the Republic of North Macedonia, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe. It shares land borders with Greece to the south, Albania to the west, Bulgaria to the east, Kosovo to the northwest and Serbia to the n ...

, and a small part of western Bulgaria. By 500 BCE, the ancient kingdom of Macedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

was centered somewhere between the southern slopes of Lower Olympus and the lowest reach of the Haliakmon River. Since 512/511 BCE, the kingdom of Macedonia was subject to the Persians

Persians ( ), or the Persian people (), are an Iranian ethnic group from West Asia that came from an earlier group called the Proto-Iranians, which likely split from the Indo-Iranians in 1800 BCE from either Afghanistan or Central Asia. They ...

, but after the battle of Plataia it regained its independence. Under Philip II and Alexander the Great, the kingdom of Macedonia forcefully expanded, placing the whole of the region of Macedonia under their rule.

Alexander's conquests produced a lasting extension of Hellenistic culture and thought across the ancient Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

, but his empire broke up on his death. His generals divided the empire between them, founding their own states and dynasties. The kingdom of Macedon was taken by Cassander

Cassander (; ; 355 BC – 297 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 305 BC until 297 BC, and '' de facto'' ruler of southern Greece from 317 BC until his death.

A son of Antipater and a contemporary of Alexander the ...

, who ruled it until his death in 297 BC. At the time, Macedonian control over the Thracoillyrian states of the region slowly waned, although the kingdom of Macedonia remained the most potent regional power. This period also saw several Celtic invasions into Macedonia. However, the Celts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

were each time successfully repelled by Cassander, and later Antigonus, leaving little overall influence on the region.

Roman Macedonia (146 BC–395 AD)

Macedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

ian sovereignty in the region was brought to an end at the hands of the rising power of Rome in the 2nd century BC. Philip V of Macedon

Philip V (; 238–179 BC) was king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by the Social War (220–217 BC), Social War in Greece (220-217 BC) ...

took his kingdom to war against the Romans in two wars during his reign (221–179 BC). The First Macedonian War (215–205 BC) was fairly successful for the Macedonians but Philip was decisively defeated in the Second Macedonian War

The Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC) was fought between Macedon, led by Philip V of Macedon, and Rome, allied with Pergamon and Rhodes. Philip was defeated and was forced to abandon all possessions in southern Greece, Thrace and Asia Minor. ...

in (200–197 BC). Although he survived war with Rome, his successor Perseus of Macedon

Perseus (; – 166 BC) was king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon from 179 until 168BC. He is widely regarded as the last List of kings of Macedonia, king of Macedonia and the last ruler from th ...

(reigned 179–168 BC) did not; having taken Macedon into the Third Macedonian War

The Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC) was a war fought between the Roman Republic and King Perseus of Macedon. In 179 BC, King Philip V of Macedon died and was succeeded by his ambitious son Perseus. He was anti-Roman and stirred anti-Roman fe ...

in (171–168 BC), he lost his kingdom when he was defeated. Macedonia was initially divided into four republics subject to Rome before finally being annexed in 146 BC as a Roman province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as Roman g ...

. Around this time, vulgar Latin was introduced in the Balkans by Latin-speaking colonists and military personnel. With the division of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

into west and east in 298 AD, Macedonia came under the rule of Rome's Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

successors. The population of the entire region was, however, depleted by destructive invasions of various Gothic and Hun tribes c. 300 – 5th century AD. Despite this, other parts of the Byzantine empire continued to flourish, in particular some coastal cities such as Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

became important trade and cultural centres.

Medieval Macedonia

Despite the Byzantine empire's power, from the beginning of the 6th century the Byzantine dominions were subject to frequent raids by various Slavic tribes which, in the course of centuries, eventually resulted in drastic demographic and cultural changes in the Empire's Balkan provinces. Although traditional scholarship attributes these changes to large-scale colonizations by Slavic-speaking groups, it has been proposed that a generalized dissipation of Roman identity might have commenced in the 3rd century, especially among rural provincials who were crippled by harsh taxation and famines. Given this background, penetrations carried by successive waves of relatively small numbers of Slavic warriors and their families might have been capable of assimilating large numbers of indigenes into their cultural model, which was sometimes seen as a more attractive alternative. In this way and in the course of time, great parts of Macedonia came to be controlled by Slavic-speaking communities. Despite numerous attacks on Thessaloniki, the city held out, and Byzantine-Roman culture continued to flourish, although Slavic cultural influence steadily increased. The Slavic settlements organized themselves along tribal and territorially based lines which were referred to by Byzantine Greek historians as "Sklaviniai". The Sklaviniai continued to intermittently assault the Byzantine Empire, either independently, or aided by Bulgar or Avar contingents. Around 680 AD a "Bulgar" group (which was largely composed of the descendants of former Roman Christians taken captive by the Avars), led by KhanKuber

Kuber (also Kouber or Kuver) was a Bulgar leader who, according to the '' Miracles of Saint Demetrius'', liberated a mixed Bulgar and Byzantine Christian population in the 670s, whose ancestors had been transferred from the Eastern Roman Empi ...

(theorized to have belonged to the same clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

as the Danubian Bulgarian khan Asparukh

Asparuh (also ''Ispor'' or (rarely) ''Isperih'') was а Bulgar Khan in the second half of the 7th century and is credited with the establishment of the First Bulgarian Empire in 681.

Early life

The '' Nominalia of the Bulgarian Khans'' states ...

), settled in the Pelagonian plain, and launched campaigns to the region of Thessaloniki. When the Empire could spare imperial troops, it attempted to regain control of its lost Balkan territories. By the time of Constans II

Constans II (; 7 November 630 – 15 July 668), also called "the Bearded" (), was the Byzantine emperor from 641 to 668. Constans was the last attested emperor to serve as Roman consul, consul, in 642, although the office continued to exist unti ...

a significant number of the Slavs of Macedonia were captured and transferred to central Asia Minor where they were forced to recognize the authority of the Byzantine emperor and serve in his ranks. In the late 7th century, Justinian II

Justinian II (; ; 668/69 – 4 November 711), nicknamed "the Slit-Nosed" (), was the last Byzantine emperor of the Heraclian dynasty, reigning from 685 to 695 and again from 705 to 711. Like his namesake, Justinian I, Justinian II was an ambitio ...

again organized a massive expedition against the Sklaviniai and Bulgars of Macedonia. Launching from Constantinople, he subdued many Slavic tribes and established the ''Theme of Thrace'' in the hinterland of the Great City, and pushed on into Thessaloniki. However, on his return he was ambushed by the Slavo-Bulgars of Kuber, losing a great part of his army, booty, and subsequently his throne. Despite these temporary successes, rule in the region was far from stable since not all of the Sklaviniae were pacified, and those that were often rebelled. The emperors rather resorted to withdrawing their defensive line south along the Aegean coast, until the late 8th century. Although a new theme—that of "Macedonia"—was subsequently created, it did not correspond to today's geographic territory, but one farther east (centred on Adrianople), carved out of the already existing Thracian and Helladic themes.

There are no Byzantine records of "Sklaviniai" after 836/837 as they were absorbed into the expanding First Bulgarian Empire

The First Bulgarian Empire (; was a medieval state that existed in Southeastern Europe between the 7th and 11th centuries AD. It was founded in 680–681 after part of the Bulgars, led by Asparuh of Bulgaria, Asparuh, moved south to the northe ...

. Slavic influence in the region strengthened along with the rise of this state, which incorporated parts of the region to its domain in 837. In the early 860s Saints Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (; born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (; born Michael, 815–885) were brothers, Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are ...

, two Byzantine Greek

Medieval Greek (also known as Middle Greek, Byzantine Greek, or Romaic; Greek: ) is the stage of the Greek language between the end of classical antiquity in the 5th–6th centuries and the end of the Middle Ages, conventionally dated to the F ...

brothers from Thessaloniki, created the first Slavic Glagolitic alphabet

The Glagolitic script ( , , ''glagolitsa'') is the oldest known Slavic alphabet. It is generally agreed that it was created in the 9th century for the purpose of translating liturgical texts into Old Church Slavonic by Saints Cyril and Methodi ...

in which the Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic ( ) is the first Slavic languages, Slavic literary language and the oldest extant written Slavonic language attested in literary sources. It belongs to the South Slavic languages, South Slavic subgroup of the ...

language was first transcribed, and are thus commonly referred to as the apostles of the Slavic world. Their cultural heritage was acquired and developed in medieval Bulgaria, where after 885 the region of Ohrid

Ohrid ( ) is a city in North Macedonia and is the seat of the Ohrid Municipality. It is the largest city on Lake Ohrid and the eighth-largest city in the country, with the municipality recording a population of over 42,000 inhabitants as of ...

(present-day Republic of North Macedonia) became a significant ecclesiastical center with the nomination of the Saint Clement of Ohrid

Saint Clement (or Kliment) of Ohrid ( Bulgarian, Macedonian, , ''Kliment Ohridski''; , ''Klḗmēs tē̂s Akhrídas''; ; – 916) was one of the first medieval Bulgarian saints, scholar, writer, and apostle to the Slavs. He was one of the mos ...

for "first archbishop in Bulgarian language" with residence in this region. In conjunction with another disciple of Saints Cyril and Methodius, Saint Naum

Naum ( Bulgarian and ), also known as Naum of Ohrid or Naum of Preslav (c. 830 – December 23, 910), was a medieval Bulgarian writer and missionary among the Slavs, considered one of the Seven Apostles of the First Bulgarian Empire. He was a ...

, Clement created a flourishing Slavic cultural center around Ohrid, where pupils were taught theology in the Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic ( ) is the first Slavic languages, Slavic literary language and the oldest extant written Slavonic language attested in literary sources. It belongs to the South Slavic languages, South Slavic subgroup of the ...

language and the Glagolitic and Cyrillic script

The Cyrillic script ( ) is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic languages, Slavic, Turkic languages, Turkic, Mongolic languages, Mongolic, Uralic languages, Uralic, C ...

at what is now called Ohrid Literary School

The Ohrid Literary School or Ohrid- ''Devol'' Literary school was one of the two major cultural centres of the First Bulgarian Empire, along with the Preslav Literary School ( Pliska Literary School). The school was established in Ohrid (in what i ...

. The Bulgarian-Byzantine boundary in the beginning of 10th century passed approximately north of Thessaloniki according to the inscription of Narash. According to the Byzantine author John Kaminiates, at that time the neighbouring settlements around Thessaloniki were inhabited by "Scythians" (Bulgarians) and the Slavic tribes of Drugubites and Sagudates, in addition to Greeks.

At the end of the 10th century, what is now the Republic of North Macedonia became the political and cultural heartland of the First Bulgarian Empire

The First Bulgarian Empire (; was a medieval state that existed in Southeastern Europe between the 7th and 11th centuries AD. It was founded in 680–681 after part of the Bulgars, led by Asparuh of Bulgaria, Asparuh, moved south to the northe ...

, after Byzantine emperors John I Tzimiskes

John I Tzimiskes (; 925 – 10 January 976) was the senior Byzantine emperor from 969 to 976. An intuitive and successful general who married into the influential Skleros family, he strengthened and expanded the Byzantine Empire to inclu ...

conquered the eastern part of the Bulgarian state during the Rus'–Byzantine War of 970–971. The Bulgarian capital Preslav

The modern Veliki Preslav or Great Preslav (, ), former Preslav (; until 1993), is a city and the seat of government of the Veliki Preslav Municipality (Great Preslav Municipality, new Bulgarian: ''obshtina''), which in turn is part of Shumen P ...

and the Bulgarian Tsar Boris II were captured, and with the deposition of the Bulgarian regalia in the Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia (; ; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque (; ), is a mosque and former Church (building), church serving as a major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The last of three church buildings to be successively ...

, Bulgaria was officially annexed to Byzantium. A new capital was established at Ohrid, which also became the seat of the Bulgarian Patriarchate. A new dynasty, that of the Comitopuli

The Kometopuli dynasty (Bulgarian language, Bulgarian: , ; Medieval Greek, Byzantine Greek: , ) was the last royal dynasty in the First Bulgarian Empire, ruling from until the fall of Bulgaria under Byzantine Empire, Byzantine rule in 1018. T ...

under Tsar Samuil and his successors, continued resistance against the Byzantines for several more decades, before also succumbing in 1018. The western part of Bulgaria including Macedonia was incorporated into the Byzantine Empire as the province of Bulgaria ( Theme of Bulgaria) and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was reduced in rank to an Archbishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associated ...

.

Intermittent Bulgarian uprisings continued to occur, often with the support of the Serbian princedoms to the north. Any temporary independence that might have been gained was usually crushed swiftly by the Byzantines. It was also marked by periods of war between the Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

and Byzantium. The Normans launched offensives from their lands acquired in southern Italy, and temporarily gained rule over small areas in the northwestern coast.

At the end of the 12th century, some northern parts of Macedonia were temporarily conquered by Stefan Nemanja

Stefan Nemanja (Serbian Cyrillic alphabet, Serbian Cyrillic: , ; – 13 February 1199) was the Grand Prince (Grand Župan#Serbia, Veliki Župan) of the Grand Principality of Serbia, Serbian Grand Principality (also known as Raška (region), Raš ...

of Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

. In the 13th century, following the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

, Macedonia was disputed among Byzantine Greeks

The Byzantine Greeks were the Medieval Greek, Greek-speaking Eastern Romans throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. They were the main inhabitants of the lands of the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire), of Constantinople and Asia ...

, Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

crusaders of the short-lived Kingdom of Thessalonica

The Kingdom of Thessalonica () was a short-lived Crusader State founded after the Fourth Crusade over conquered Byzantine lands in today's territory of Northern Greece and Thessaly.

History

Background

After the fall of Constantinople to the ...

, and the revived Bulgarian state. Most of southern Macedonia was secured by the Despotate of Epirus

The Despotate of Epirus () was one of the Greek Rump state, successor states of the Byzantine Empire established in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 by a branch of the Angelos dynasty. It claimed to be the legitimate successor of the ...

and then by the Empire of Nicaea

The Empire of Nicaea (), also known as the Nicene Empire, was the largest of the three Byzantine Greeks, Byzantine Greek''A Short history of Greece from early times to 1964'' by Walter Abel Heurtley, W. A. Heurtley, H. C. Darby, C. W. Crawley, C ...

, while the north was ruled by Bulgaria. After 1261 however, all of Macedonia returned to Byzantine rule, where it largely remained until the Byzantine civil war of 1341–1347

The Byzantine civil war of 1341–1347, sometimes referred to as the Second Palaiologan Civil War, was a conflict that broke out in the Byzantine Empire after the death of Andronikos III Palaiologos over the guardianship of his nine-year-old son ...

. Taking advantage of this conflict, the Serb ruler Stefan Dushan expanded his realm and founded the Serbian Empire

The Serbian Empire ( sr-Cyrl-Latn, Српско царство, Srpsko carstvo, separator=" / ", ) was a medieval Serbian state that emerged from the Kingdom of Serbia. It was established in 1346 by Dušan the Mighty, who significantly expande ...

, which included all of Macedonia, northern and central Greece – excluding Thessaloniki, Athens and the Peloponnese. Dushan's empire however broke up shortly after his death in 1355. After his death local rulers in the regions of Macedonia were despot Jovan Uglješa in eastern Macedonia, and kings Vukašin Mrnjavčević

Vukašin () is an old Slavic name of Serbian origin. It is composed from two words: Vuk (wolf) and sin ( son), so it means sin vuka (son of wolf). In some places in Croatia and Bosnia it can be found as a surname.

The name Vukašin can be foun ...

and his son Marko Mrnjavčević in western regions of Macedonia.

Ottoman Macedonia

Since the middle of the 14th century, the Ottoman threat was looming in the Balkans, as the Ottomans defeated the various Christian principalities, whether Serb, Bulgarian or Greek. After the Ottoman victory in the

Since the middle of the 14th century, the Ottoman threat was looming in the Balkans, as the Ottomans defeated the various Christian principalities, whether Serb, Bulgarian or Greek. After the Ottoman victory in the Battle of Maritsa

The Battle of Maritsa or Battle of Chernomen (; in tr. ''Second Battle of Maritsa'') took place at the Maritsa River near the village of Chernomen (present-day Ormenio, Greece) on 26 September 1371 between Ottoman forces commanded by Lala S ...

in 1371, most of Macedonia accepted vassalage to the Ottomans and by the end of the 14th century the Ottoman Empire gradually annexed the region. The final Ottoman capture of Thessalonica

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area) and the capital city, capital of the geographic reg ...

(1430) was seen as the prelude to the fall of Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

itself. Macedonia remained a part of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

for nearly 500 years, during which time it gained a substantial Turkish minority. Thessaloniki later become the home of a large Sephardi Jewish population following the expulsions of Jews after 1492 from Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

.

Birth of nationalism and of Macedonian identities

Over the centuries Macedonia had become a multicultural region. The historical references mention Greeks, Bulgarians, Turks, Albanians, Gypsies, Jews, Aromanians and Megleno-Romanians. It is often claimed that macédoine, the fruit or vegetable salad, was named after the area's very mixed population, as it could be witnessed at the end of the 19th century. From the Middle Ages to the early 20th century the Slavic-speaking population in Macedonia was identified mostly as Bulgarian. During the period ofBulgarian National Revival

The Bulgarian Revival (, ''Balgarsko vazrazhdane'' or simply: Възраждане, ''Vazrazhdane'', and ), sometimes called the Bulgarian National Revival, was a period of socio-economic development and national integration among Bulgarian pe ...

many Bulgarians from these regions supported the struggle for creation of Bulgarian cultural educational and religious institutions, including Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate (; ) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953.

The Exarchate (a de facto autocephaly) ...

.Journal Bulgarski knizhitsi, Constantinople, No. 10 May 1858, p. 19, in English �Vacalopulos, Konstandinos A. Modern history of Macedonia, Thessaloniki 1988, pp. 52, 57, 64

Krste Misirkov

Krste Petkov Misirkov (, ; ; Serbian Cyrillic: Крста Петковић Мисирков; ; 18 November 1874 – 26 July 1926) was a philologist, journalist, historian and ethnographer from the region of Macedonia.

In the period between 1903 ...

, a philologist and publicist, wrote his work " On the Macedonian Matters" (1903), for which he is heralded by Macedonians as one of the founders of the Macedonian nation.

After the revival of Greek, Serbian, and Bulgarian statehood in the 19th century, the Ottoman lands in Europe that became identified as "Macedonia", were contested by all three governments, leading to the creation in the 1890s and 1900s of rival armed groups who divided their efforts between fighting the Turks and one another. The most important of these was the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO; ; ), was a secret revolutionary society founded in the Ottoman territories in Europe, that operated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Founded in 1893 in Salonica, it initia ...

, which organized the so-called Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising in 1903, fighting for an autonomous or independent Macedonian state, and the Greek efforts from 1904 until 1908 ( Greek Struggle for Macedonia). Diplomatic intervention by the European powers led to plans for an autonomous Macedonia under Ottoman rule.

The restricted borders of the modern Greek state at its inception in 1830 disappointed the inhabitants of northern Greece (Epirus and Macedonia). Addressing these concerns in 1844, the Greek Prime Minister Kolettis addressed the constitutional assembly in Athens that "the Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece (, Romanization, romanized: ''Vasíleion tis Elládos'', pronounced ) was the Greece, Greek Nation state, nation-state established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally ...

is not Greece; it is only a part, the smallest and poorest, of Greece. The Greek is not only he who inhabits the kingdom, but also he who lives in Ioannina, or Thessaloniki, or Serres, or Odrin" . He mentions cities and islands that were under Ottoman possession as composing the Great Idea (Greek: Μεγάλη Ιδέα, ''Megáli Idéa'') which meant the reconstruction of the classical Greek world

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in ancient Greece,The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the period from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C." ( Thomas R. Mar ...

or the revival of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. The important idea here is that for Greece, Macedonia was a region with large Greek populations expecting annexation to the new Greek state.

The 1878

The 1878 Congress of Berlin

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire on the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Rus ...

changed the Balkan map again. The treaty restored Macedonia and Thrace to the Ottoman Empire. Serbia, Romania and Montenegro were granted full independence, and some territorial expansion at the expense of the Ottoman Empire. Russia would maintain military advisors in Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia until May 1879. Austria-Hungary was permitted to occupy Bosnia, Herzegovina and the Sanjak of Novi Pazar. The Congress of Berlin also forced Bulgaria, newly given autonomy by the 1878 Treaty of San Stefano, to return over half of its newly gained territory to the Ottoman Empire. This included Macedonia, a large part of which was given to Bulgaria, due to Russian pressure and the presence of significant numbers of Bulgarians and adherents to the Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate (; ) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953.

The Exarchate (a de facto autocephaly) ...