Lesvian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern

After the

After the

After the

After the  The relative prosperity of the island—wealth was apparently concentrated among the Greek Christian bourgeoisie rather than the Muslim community—contributed to the island not taking part in the

The relative prosperity of the island—wealth was apparently concentrated among the Greek Christian bourgeoisie rather than the Muslim community—contributed to the island not taking part in the

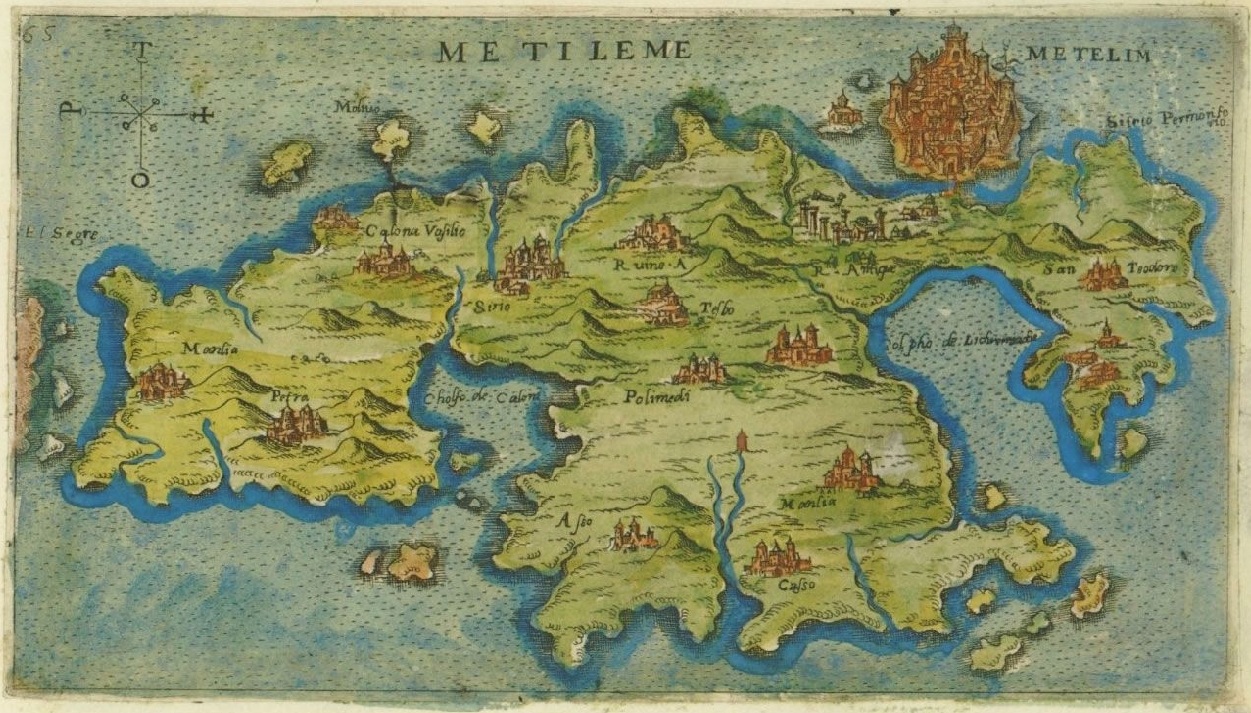

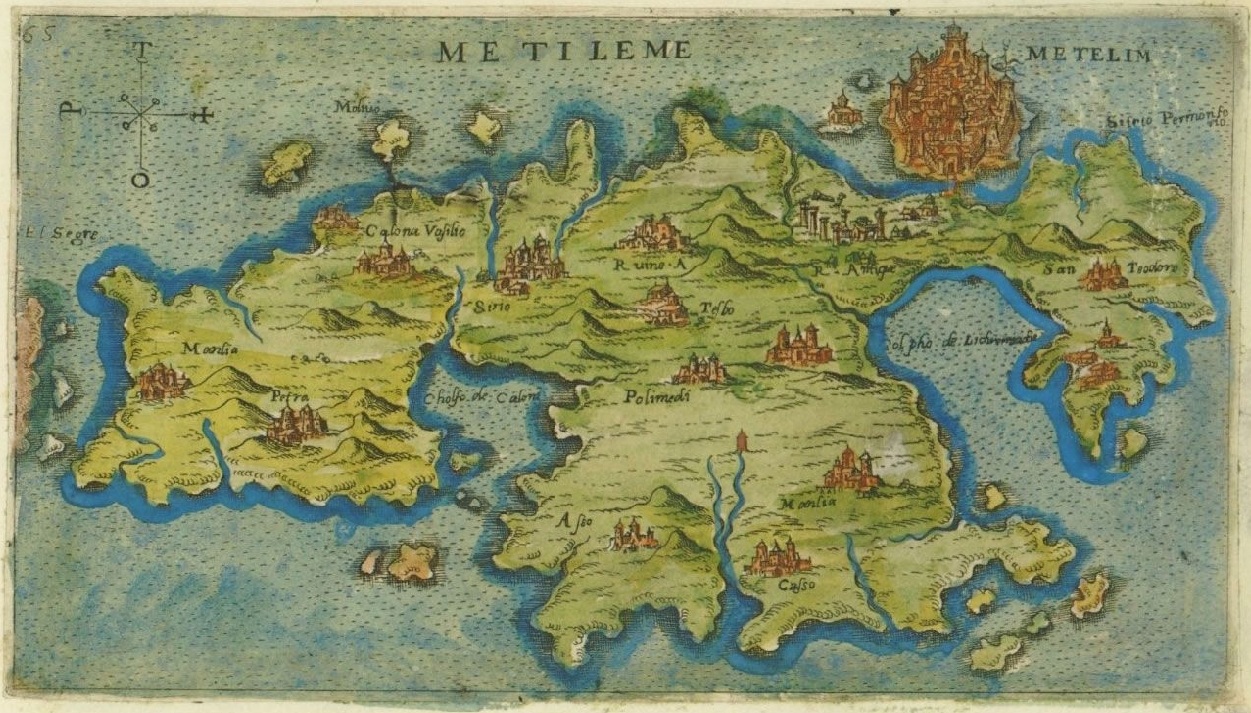

Lesbos lies in the far east of the Aegean sea, facing the Turkish coast ( Gulf of Edremit) from the north and east; at the narrowest point, the Mytilini Strait is about wide. In late Palaeolithic/Mesolithic times it was joined to the Anatolian mainland before the end of the Last Glacial Period. The shape of the island is roughly triangular, but it is deeply intruded by the gulfs of Kalloni, with an entry on the southern coast, and of

Lesbos lies in the far east of the Aegean sea, facing the Turkish coast ( Gulf of Edremit) from the north and east; at the narrowest point, the Mytilini Strait is about wide. In late Palaeolithic/Mesolithic times it was joined to the Anatolian mainland before the end of the Last Glacial Period. The shape of the island is roughly triangular, but it is deeply intruded by the gulfs of Kalloni, with an entry on the southern coast, and of

The entire territory of Lesbos is "Lesvos

The entire territory of Lesbos is "Lesvos

The economy of Lesbos is essentially

The economy of Lesbos is essentially

File:Fire ship by Volanakis.jpg, "The burning of the Ottoman frigate at Eresos by Dimitrios Papanikolis" by Konstantinos Volanakis

File:Lesbos. Port Authority Building Mytilene, c. 1910.jpg, Ottoman flag in Mytilene in the last days of the Ottoman period

File:Greek troops land at Mytilene, 1912.jpeg, Greek troops land at Mytilene, 1912

File:Petra town.JPG, Petra, Lesbos

File:After the scraping of the salt Kalloni.jpg, Extraction of the salt in Lesbos

File:Άποψη ελαιοτριβείου αριστερά.jpg, Museum of industrial olive oil production, Agia Paraskevi

File:Lesbos Limonas011.JPG, Limonas monastery

File:Μονή Παμμεγίστων Ταξιαρχών Μανταμάδου (2) ΛΕΣΒΟΣ.jpg, Taxiarchis Monastery

File:Lesbos Agiassos04.JPG, Panagia Church in Agiasos

Lesvos News

Elstat

*

Guide of Lesbos Island

News of Mytilene and Lesvos Island

* {{Authority control * Islands of Greece Regional units of the North Aegean Lesbianism Global Geoparks Network members Landforms of Lesbos Islands of the North Aegean Geoparks in Greece Territories of the Republic of Genoa Hellenic Navy bases Populated places in Lesbos

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline

A coast (coastline, shoreline, seashore) is the land next to the sea or the line that forms the boundary between the land and the ocean or a lake. Coasts are influenced by the topography of the surrounding landscape and by aquatic erosion, su ...

, making it the third largest island in Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

and the eighth largest in the Mediterranean. It is separated from Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

by the narrow Mytilini Strait. On the southeastern coast is the island's capital and largest city, Mytilene

Mytilene (; ) is the capital city, capital of the Greece, Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of the Aegean. It was fo ...

(), whose name is also used for the island as a whole. Lesbos is a separate regional unit with the seat in Mytilene, which is also the capital of the larger North Aegean

The North Aegean Region (, ) is one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece, and the smallest of the thirteen by population. It comprises the islands of the north-eastern Aegean Sea, called the North Aegean islands, except for Thasos an ...

region. The region includes the islands of Lesbos, Chios

Chios (; , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greece, Greek list of islands of Greece, island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, tenth largest island in the Medi ...

, Ikaria, Lemnos

Lemnos ( ) or Limnos ( ) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos (regional unit), Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean modern regions of Greece ...

, and Samos

Samos (, also ; , ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese archipelago, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the Mycale Strait. It is also a separate reg ...

. The total population of the island was 83,755 in 2021. A third of the island's inhabitants live in the capital, while the remainder are concentrated in small towns and villages. The largest are Plomari, Agia Paraskevi, Polichnitos, Agiassos, Eresos, Gera

Gera () is a city in the German state of Thuringia. With around 93,000 inhabitants, it is the third-largest city in Thuringia after Erfurt and Jena as well as the easternmost city of the ''Thüringer Städtekette'', an almost straight string of ...

, and Molyvos (the ancient Mythimna).

According to later Greek writers, Mytilene was founded in the 11th century BC by the family Penthilidae, who arrived from Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

and ruled the city-state until a popular revolt (590–580 BC) led by Pittacus of Mytilene ended their rule. In fact, the archaeological and linguistic records may indicate a late Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

arrival of Greek settlers, although references in Late Bronze Age Hittite archives indicate a likely Greek presence then. According to Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

's ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'', Lesbos was part of the kingdom of Priam

In Greek mythology, Priam (; , ) was the legendary and last king of Troy during the Trojan War. He was the son of Laomedon. His many children included notable characters such as Hector, Paris, and Cassandra.

Etymology

Most scholars take the e ...

, which was based in Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

. In the Middle Ages, it was under Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

and then Genoese rule. Lesbos was conquered

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or legal prohibitions against conquest ...

by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

in 1462. The Ottomans then ruled the island until the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League (the Kingdoms of Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Greece, Greece and Kingdom of Montenegro, Montenegro) agai ...

in 1912, when it became part of the Kingdom of Greece.

Names

The English name ''Lesbos'' (pronounced , also ) is fromAncient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

(). The name appears in Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

Hittite texts as ( ''Lāzpa''). The earliest reference to Lesbos in Greek texts comes from the Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

ic poems, where it is described as "well-built". The etymology of the name is obscure, but may have originally meant , .

In Modern Greek

Modern Greek (, or , ), generally referred to by speakers simply as Greek (, ), refers collectively to the dialects of the Greek language spoken in the modern era, including the official standardized form of the language sometimes referred to ...

, the letter beta

Beta (, ; uppercase , lowercase , or cursive ; or ) is the second letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 2. In Ancient Greek, beta represented the voiced bilabial plosive . In Modern Greek, it represe ...

⟨β⟩ is pronounced and transliterated as , thus producing the alternative form ''Lesvos''. An older name for the island that was maintained in Aeolic Greek

In linguistics, Aeolic Greek (), also known as Aeolian (), Lesbian or Lesbic dialect, is the set of dialects of Ancient Greek spoken mainly in Boeotia; in Thessaly; in the Aegean island of Lesbos; and in the Greek colonies of Aeolis in Anat ...

was (). Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

also refers to the island with the names (, ) and (, often understood as ). In Greece, Lesbos is commonly referred to as Mytilene () after its capital. Some suggest that the name derives from the Anatolian root "muwa" meaning power, while others have suggested a link to the ancient Greek word μυτίλος (''mytilos''), meaning mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

, or a type thereof. The ending ''-ene'' appears to be the common Greek place name suffix (''-enos'' in masculine

Masculinity (also called manhood or manliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles generally associated with men and boys. Masculinity can be theoretically understood as socially constructed, and there is also evidence that some beh ...

) indicating provenance. The island is also sometimes called the "Island of the Poets", alluding to renowned native poets like Alcaeus and Sappho

Sappho (; ''Sapphṓ'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; ) was an Ancient Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied by music. In ancient times, Sapph ...

.

History

Prehistory

Lesbos has been inhabited since at least 3000 BC. The oldest artifacts found on the island may date to the late Paleolithic period. Important archaeological sites on the island are theNeolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

cave of Kagiani, probably a refuge for shepherds, the Neolithic settlement of Chalakies, and the extensive habitation of Thermi (3000–1000 BC). The largest habitation is found in Lisvori, dating back to 2800–1900 BC, part of which is submerged in shallow coastal waters.

Lesbos is mentioned in two Hittite texts from the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, a period during which the island appears to have been a dependent of the Seha River Land. The Manapa-Tarhunta letter recounts an incident in which a group of purple-dyers from Lesbos defected from the Sehan king.

Ancient and Classical era

According to ClassicalGreek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of ancient Greek folklore, today absorbed alongside Roman mythology into the broader designation of classical mythology. These stories conc ...

, Lesbos was the patron god of the island. Macareus of Rhodes was reputedly the first king whose many daughters bequeathed their names to some of the present larger towns. In Classical myth his sister, Canace, was killed to have him made king. The place names with female origins are claimed by some to be much earlier settlements named after local goddesses, who were replaced by gods; however, there is little evidence to support this. Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

refers to the island as "''Macaros edos''," the seat of Macar. Hittite records from the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

name the island ''Lazpa'' and must have considered its population significant enough to allow the Hittites to "borrow their Gods" (presumably idols) to cure their king when the local gods were not forthcoming. It is believed that emigrants from mainland Greece, mainly from Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

, entered the island in the Late Bronze Age and bequeathed it with the Aeolic dialect of the Greek language, whose written form survives in the poems of Sappho

Sappho (; ''Sapphṓ'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; ) was an Ancient Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied by music. In ancient times, Sapph ...

, amongst others. In classical times, the cities of the island formed a pentapolis

A pentapolis (from Ancient Greek, Greek ''penta-'', 'five' and ''polis'', 'city') is a geographic and/or institutional grouping of five cities. Cities in the ancient world probably formed such groups for political, commercial and military rea ...

, comprising Mytilene

Mytilene (; ) is the capital city, capital of the Greece, Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of the Aegean. It was fo ...

, Methymna, Antissa, Eresos, and Pyrrha

In Greek mythology, Pyrrha (; ) was the daughter of Epimetheus and Pandora and wife of Deucalion of whom she had three sons, Hellen, Amphictyon, Orestheus; and three daughters Protogeneia, Pandora and Thyia. According to some accounts, Hell ...

. Pyrrha was destroyed in an earthquake in 231 BC, and Antissa by the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

in 168 BC.

Two of the nine lyric poets in the Ancient Greek canon, Sappho and Alcaeus, were from Lesbos. Phanias wrote history. The seminal artistic creativity of those times brings to mind the myth of Orpheus

In Greek mythology, Orpheus (; , classical pronunciation: ) was a Thracians, Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet. He was also a renowned Ancient Greek poetry, poet and, according to legend, travelled with Jason and the Argonauts in se ...

to whom Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

gave a lyre

The lyre () (from Greek λύρα and Latin ''lyra)'' is a string instrument, stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the History of lute-family instruments, lute family of instruments. In organology, a ...

and the Muse

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, the Muses (, ) were the Artistic inspiration, inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the poetry, lyric p ...

s taught to play and sing. When Orpheus incurred the wrath of the god Dionysus he was dismembered by the Maenads and of his body parts his head and his lyre found their way to Lesbos where they have "remained" ever since. Pittacus was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. In classical times, Hellanicus advanced historiography and Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

, the father of botany, succeeded Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

as the head of the Lyceum. Aristotle and Epicurus

Epicurus (, ; ; 341–270 BC) was an Greek philosophy, ancient Greek philosopher who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy that asserted that philosophy's purpose is to attain as well as to help others attain tranqui ...

lived there for some time, and it is there that Aristotle began systematic zoological investigations.

Theophanes, the historian who recorded Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey ( ) or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman who was prominent in the last decades of the Roman Republic. ...

's campaigns, was also from Lesbos. As the Greek novel '' Daphnis and Chloe'' is set on Lesbos, the author, Longus

Longus, sometimes Longos (), was the author of an ancient Greek novel or romance, '' Daphnis and Chloe''. Nothing is known of his life; it is assumed that he lived on the isle of Lesbos (setting for ''Daphnis and Chloe'') during the 2nd centu ...

, is usually assumed to be from the island. The abundant grey pottery ware found on the island and the worship of Cybele

Cybele ( ; Phrygian: ''Matar Kubileya, Kubeleya'' "Kubeleya Mother", perhaps "Mountain Mother"; Lydian: ''Kuvava''; ''Kybélē'', ''Kybēbē'', ''Kybelis'') is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible forerunner in the earliest ...

, the great mother-goddess of Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, suggest the cultural continuity of the population from Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

times. When the Persian king Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

defeated Croesus

Croesus ( ; ; Latin: ; reigned:

)

was the Monarch, king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his Siege of Sardis (547 BC), defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC. According to Herodotus, he reigned 14 years. Croesus was ...

(546 BC) the Ionic Greek cities of Anatolia and the adjacent islands became Persian subjects and remained such until the Persians were defeated by the Greeks at the Battle of Salamis (480 BC). The island was governed by an oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

in archaic times, followed by quasi-democracy in classical times. Around this time, Arion

Arion (; ) was a kitharode in ancient Greece, a Dionysiac poet credited with inventing the dithyramb. The islanders of Lesbos claimed him as their native son, but Arion found a patron in Periander, tyrant of Corinth. Although notable for his mu ...

developed the type of poem called dithyramb

The dithyramb (; , ''dithyrambos'') was an ancient Greek hymn sung and danced in honor of Dionysus, the god of wine and fertility; the term was also used as an epithet of the god. Plato, in '' The Laws'', while discussing various kinds of music m ...

, the progenitor of tragedy, and Terpander

Terpander ( ''Terpandros''), of Antissa in Lesbos Island, Lesbos, was a Ancient Greece, Greek poet and citharede who lived about the first half of the 7th century BC. He was the father of Greek music and through it, of lyric poetry, although his o ...

invented the seven-note musical scale for the lyre. For a short period it was a member of the Athenian confederacy, its apostasy from which is recounted by Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

in the '' Mytilenian Debate'', in Book III of his ''History of the Peloponnesian War

The ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' () is a historical account of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), which was fought between the Peloponnesian League (led by Sparta) and the Delian League (led by Classical Athens, Athens). The account, ...

''. In Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

times, the island belonged to various Successor kingdoms until 79 BC when it passed into Roman hands. Remnants of its Roman medieval history are three impressive castles. The cities of Mytilene and Methymna have been bishoprics since the 5th century. By the early 10th century, Mytilene had been raised to the status of a metropolitan see

Metropolitan may refer to:

Areas and governance (secular and ecclesiastical)

* Metropolitan archdiocese, the jurisdiction of a metropolitan archbishop

** Metropolitan bishop or archbishop, leader of an ecclesiastical "mother see"

* Metropolitan ...

. Methymna achieved the same by the 12th century.

Middle Ages and Byzantine era

During the Middle Ages, Lesbos belonged to theByzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. In 802, the Byzantine Empress Irene was exiled to Lesbos after her deposition and died there. The island served as a gathering base for the fleet of the rebel Thomas the Slav in the early 820s. In the late 9th century, it was heavily raided by the Emirate of Crete

The Emirate of Crete ( or , ; ) was an Arab Islamic state that existed on the Mediterranean island of Crete from the late 820s to Siege of Chandax, the reconquest of the island by the Byzantine Empire in 961. Although the emirate recognized the ...

. As a result, the inhabitants of Eresos abandoned their town and settled in Mount Athos

Mount Athos (; ) is a mountain on the Athos peninsula in northeastern Greece directly on the Aegean Sea. It is an important center of Eastern Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodox monasticism.

The mountain and most of the Athos peninsula are governed ...

. In the 10th century, it was part of the theme of the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

, while in the late 11th century it formed a (fiscal district) under a in Mytilene. In –1093, the island was briefly occupied by the Seljuk Turkish emir Tzachas, ruler of Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

, but he was unable to capture Methymna, which resisted throughout. In the 12th century, the island became a frequent target for plundering raids by the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

.

After the

After the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

(1202–1204) the island passed to the Latin Empire

The Latin Empire, also referred to as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, was a feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to replace the Byzantin ...

, but was reconquered by the Empire of Nicaea

The Empire of Nicaea (), also known as the Nicene Empire, was the largest of the three Byzantine Greeks, Byzantine Greek''A Short history of Greece from early times to 1964'' by Walter Abel Heurtley, W. A. Heurtley, H. C. Darby, C. W. Crawley, C ...

sometime after 1224. In 1354, it was granted as a dowry and fief to the Genoese Francesco I Gattilusio by the Byzantine emperor John V Palaiologos

John V Palaiologos or Palaeologus (; 18 June 1332 – 16 February 1391) was Byzantine emperor from 1341 to 1391, with interruptions. His long reign was marked by constant civil war, the spread of the Black Death and several military defea ...

. The Gattilusio family ruled the island for over a century, engaging in fortifications at the Castle of Mytilene, Molyvos (ancient Methymna), and the fort of Agios Theodoros at the site of ancient Antissa.

Ottoman era

After the

After the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 55-da ...

in 1453, the Gattilusi continued to rule Lesbos as tributary vassals to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, until the island was conquered

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or legal prohibitions against conquest ...

by Sultan Mehmed II

Mehmed II (; , ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror (; ), was twice the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from August 1444 to September 1446 and then later from February 1451 to May 1481.

In Mehmed II's first reign, ...

in September 1462. After the capture of Lesbos, the richer inhabitants were moved to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

in order to repopulate the city, some boys and girls were taken away into imperial service, but the rest of the population remained. Mehmed II brought in Muslim settlers from Rumelia

Rumelia (; ; ) was a historical region in Southeastern Europe that was administered by the Ottoman Empire, roughly corresponding to the Balkans. In its wider sense, it was used to refer to all Ottoman possessions and Vassal state, vassals in E ...

and Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, and encouraged his Janissaries

A janissary (, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops. They were the first modern standing army, and perhaps the first infantry force in the world to be equipped with firearms, adopted du ...

to settle there and take local wives. Among them was Yakub, the father of the pirate admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa

Hayreddin Barbarossa (, original name: Khiḍr; ), also known as Hayreddin Pasha, Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1483 – 4 July 1546), was an Ottoman corsair and later admiral of the Ottoman Navy. Barbarossa's ...

. Named Midilli () after its capital, Mytilene, the island became a (province) of the Eyalet of Rumelia, and after 1534 of the Eyalet of the Archipelago. Mytilene and Molova (the Turkish name for Molyvos/Methymna) became seats of kadis. The cathedral of Mytilene was converted into a mosque. Otherwise, the organization of the local Orthodox church was not altered.

In 1464, as part of the First Ottoman–Venetian War, the Venetians under Orsato Giustiniani occupied the fort of Agios Theodoros, but failed to capture the rest of the island, and destroyed the castle upon their withdrawal. Another attack occurred in 1474, when the Venetians under Pietro Mocenigo raided the island. During the Second Ottoman–Venetian War, a Venetian-led fleet of 200 ships besieged Mytilene, but the attack was defeated by Şehzade Korkut. His father, Sultan Bayezid II

Bayezid II (; ; 3 December 1447 – 26 May 1512) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1481 to 1512. During his reign, Bayezid consolidated the Ottoman Empire, thwarted a pro-Safavid dynasty, Safavid rebellion and finally abdicated his throne ...

, then reinforced the Castle of Mytilene with artillery bastions.

The large majority of the island's population remained Greek Christian, although there was a sizeable Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

community, formed from both immigrants and converts; from 7.4% of households in 1488, it rose to a peak of 19.45% in 1831 before starting to decline in relative terms, reaching 14% in 1892. The Islamization process peaked between 1602 and 1644. The Muslims lived throughout the island. Relations between the two communities were generally good, and Lesbians were often bilingual in both Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Ottoman Turkish

Ottoman Turkish (, ; ) was the standardized register of the Turkish language in the Ottoman Empire (14th to 20th centuries CE). It borrowed extensively, in all aspects, from Arabic and Persian. It was written in the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. ...

. During Ottoman rule, the compulsory devshirme

Devshirme (, usually translated as "child levy" or "blood tax", , .) was the Ottoman practice of forcibly recruiting soldiers and bureaucrats from among the children of their Balkan Christian subjects and raising them in the religion of Islam ...

system was implemented into the island, where the locals including Muslim landowners and the state representatives negotiated enlisting their teenagers into the Ottoman military by preventing some boys from being levied and sneaking others into the levied groups. For example, in the winter between 1603 and 1604, 105 boys were levied from the island and Lesvos was the only Island that the levy was implemented on the levy of this period.

Lesbos prospered from trade, and Mytilene was considered the busiest Ottoman port in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

. West European representatives are attested in the city already in 1700, acting as vice-consuls for the consulates in Smyrna. The island exported olives and olive oil, wheat, grapes, raisins and wine, figs, fish, dairy products, acorns, soap, leather and hides, pitch and livestock. Mytilene itself increased five-fold in population during the Ottoman period. A number of new mosques were erected in the city, and Hayreddin Barbarossa built a madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , ), sometimes Romanization of Arabic, romanized as madrasah or madrassa, is the Arabic word for any Educational institution, type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whet ...

, dervish lodge, and imaret erected in his hometown. Many of the early Ottoman buildings, as well as the city walls, were destroyed in the earthquake of 1867. Mevlevi

The Mevlevi Order or Mawlawiyya (; ) is a Sufi order that originated in Konya, Turkey (formerly capital of the Sultanate of Rum) and which was founded by the followers of Jalaluddin Muhammad Balkhi Rumi, a 13th-century Persian poet, Sufi ...

and Bektashi

Bektashism (, ) is a tariqa, Sufi order of Islam that evolved in 13th-century western Anatolia and became widespread in the Ottoman Empire. It is named after the wali, ''walī'' "saint" Haji Bektash Veli, with adherents called Bektashis. The ...

lodges are attested, since 1544 for the former, and since 1699 for the latter. Molyvos, which was the island's second city for most of the Ottoman period, also experienced growth, doubling in size; unlike Mytilene, the Muslim element came to predominate, and comprised over half the population by 1874. Mosques were built and fortifications were undertaken during the long Cretan War with Venice. But during the 19th century, the town declined rapidly in importance and number of inhabitants, a decline which continued to modern times. In the mid-18th century, the castle and settlement of Sigri were established to protect the western coast from pirate attacks.

The relative prosperity of the island—wealth was apparently concentrated among the Greek Christian bourgeoisie rather than the Muslim community—contributed to the island not taking part in the

The relative prosperity of the island—wealth was apparently concentrated among the Greek Christian bourgeoisie rather than the Muslim community—contributed to the island not taking part in the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

in 1821–1829. During the second half of the 19th century, this prosperity became evident in the construction of large and ornamented mansions and churches; the Muslims followed suit, employing the fashionable Neo-Classical and Neo-Gothic

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half of the 19th century ...

styles in their own renovations of their mosques, especially after the destructive 1867 earthquake. The Ottoman writer and liberal politician Namık Kemal served in the local administration in 1877–1884. In 1905, four European powers seized the customs and telegraph offices in the island to pressure the Ottoman government to accept their plan for an international commission that would supervise the provinces of Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

.

Modern era

In 1912, theFirst Balkan War

The First Balkan War lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League (the Kingdoms of Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Greece, Greece and Kingdom of Montenegro, Montenegro) agai ...

broke out between the kingdoms of Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

and Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

, against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

over the independence and expansion of Christian Balkan states. Under Rear Admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis, Greek naval forces landed at Lesbos on 21 November 1912, commencing the Battle of Lesbos. Kountouriotis sent an ultimatum to secure Mytilene under Greece, which Ottoman officials agreed to, before fleeing the city. The operation to annex the rest of the island was placed under Colonel Apollodoros Syrmakezis. Syrmakezis led 3,175 troops towards an Ottoman camp in Filia, reaching the outskirts of the city on 19 December, with an attack planned for the following morning. However, Ottoman military commanders approached Syrmakezis with a request for an armistice and Ottoman surrender was finalised on 21 December 1912, a month after the commencement of the battle. Nine Greek troops were killed and 81 were injured during the battle. The following year, the Ottoman Empire denied their previous agreement to cede Lesbos to Greece, until the Treaty of London.

In the Greco-Turkish population exchange that followed World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, the local Muslims left the island and Lesbos returned to a fully Greek Christian population, as it had been before the Ottoman era. In 1922, many Greek refugees

Greek refugees is a collective term used to refer to the more than one million Greek Orthodox natives of Asia Minor, Thrace and the Black Sea areas who fled during the Greek genocide (1914-1923) and Greece's later defeat in the Greco-Turkish W ...

of the war and the concurrent Greek genocide settled in Lesbos. These refugees were mostly women and children as the men were either fighting or had died in battle. A statue of a mother cradling her children named the "Statue of the Asia Minor Mother" was donated by the refugees and erected in Mytilene. Twenty years later, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

conducted an invasion of Greece and Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

, with both being defeated in 1941 and subsequently divided between the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

. Lesbos was occupied by Germany until 10 September 1944, when Greece was liberated.

The poet Odysseus Elytis, the descendant of an old family of Lesbos, received the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

in 1979.

Tourism

Lesbos is known to be one of the Greek island touristic hotspots, especially during its tourism season of April, May, June, and July. Mytilene airport management recorded 47,379 tourists visiting Lesbos in its 2015 tourism season. Therefugee crisis

A refugee crisis can refer to difficulties and/or dangerous situations in the reception of large groups of refugees. These could be Forced displacement, forcibly displaced persons, internally displaced persons, asylum seekers or any other huge ...

has since slowed down tourism to the island, with a 67.89% decrease rate from June 2015 to June 2016. 6,841 Europeans on 47 flights arrived in Lesbos during its 2016 tourism season, compared to July the previous year, which saw 18,373 Europeans fly to the island on 130 flights. 94 cruise ships full of tourists arrived in Lesbos in 2011 and only one in 2018. Of the refugee crisis' impact on tourism, Maria Dimitriou, a local shop owner from Mithymna, said, "2015 was a very good year for tourism and then, suddenly they started to arrive. The refugees began arriving in mid-July, when the hotels were full of tourists. There were refugees everywhere, lying down with all their trash. And after this, tourism stopped."

In 2019, the head of the Lesbos chamber of commerce, Vangelis Mirsinias, told ''The Jakarta Post

''The Jakarta Post'' is a daily English-language newspaper in Indonesia. The paper is owned by PT Bina Media Tenggara and based in the nation's capital, Jakarta.

''The Jakarta Post'' started as a collaboration between four Indonesian media ...

'' that the island's administration is trying to "woo back the tourists" and they "want to remind people of how beautiful" Lesbos is." He advocated for the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

to help in advertising and also said, "The economy is still paying the impact of the crisis. It will need time and money to change this image." Lesbos is also a hotspot for Dutch tourists and one Dutch tourist said that tourism had halted because people "did not feel like seeing all this misery" of the refugees. One local told the publication that residents had become "fed up" and "people are angry towards the government and towards Europe: they told us not to worry, the camps won't last. But it's still there", whilst another business owner explained that he had lost a third of his business and "blames all the negative media attention" for the lack of tourists. ''The Jakarta Post'' also reported that tourists have increased in numbers in recent years, with 63,000 arriving in 2018. The COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

has also damaged the island's tourism industry.

In April 2022, the Greek government announced a dedication of €2 million in restoring tourism in Lesbos and four other islands. In October 2022, it was announced that Lesbos would return to the cruise ship industry. Konstantinos Moutzouris, the governor of the North Aegean Region, which Lesbos is under, explained that the region's administration will run a study "in order to develop cruise tourism on the island." The deputy governor of tourism, Nikolaos Nyktas, believed that the cruise industry "suits the island and its culture", while the head of development for the project, Ioannis Bras, said that the island could "offer a lot to the cruise market".

In English and most other European languages, including Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, the term ''lesbian

A lesbian is a homosexual woman or girl. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate nouns with female homosexu ...

'' is commonly used to refer to homosexual women. This use of the term derives from the poems of Sappho

Sappho (; ''Sapphṓ'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; ) was an Ancient Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied by music. In ancient times, Sapph ...

, who was born in Lesbos and who wrote with powerful emotional content directed toward other women. Due to this association, the town of Eresos, her birthplace, is visited frequently by LGBT tourists.

Geography

Lesbos lies in the far east of the Aegean sea, facing the Turkish coast ( Gulf of Edremit) from the north and east; at the narrowest point, the Mytilini Strait is about wide. In late Palaeolithic/Mesolithic times it was joined to the Anatolian mainland before the end of the Last Glacial Period. The shape of the island is roughly triangular, but it is deeply intruded by the gulfs of Kalloni, with an entry on the southern coast, and of

Lesbos lies in the far east of the Aegean sea, facing the Turkish coast ( Gulf of Edremit) from the north and east; at the narrowest point, the Mytilini Strait is about wide. In late Palaeolithic/Mesolithic times it was joined to the Anatolian mainland before the end of the Last Glacial Period. The shape of the island is roughly triangular, but it is deeply intruded by the gulfs of Kalloni, with an entry on the southern coast, and of Gera

Gera () is a city in the German state of Thuringia. With around 93,000 inhabitants, it is the third-largest city in Thuringia after Erfurt and Jena as well as the easternmost city of the ''Thüringer Städtekette'', an almost straight string of ...

, in the southeast.

The island is forested and mountainous with two large peaks, Mount Lepetymnos at and Mount Olympus at (not to be confused with Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (, , ) is an extensive massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia, between the regional units of Larissa (regional unit), Larissa and Pieria (regional ...

in Thessaly on the Greek mainland), dominating its northern and central sections. The island's volcanic origin is manifested in several hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a Spring (hydrology), spring produced by the emergence of Geothermal activity, geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow ...

s and the two gulfs. Lesbos is verdant, aptly named ''Emerald Island'', with a greater variety of flora than expected for the island's size. Eleven million olive tree

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'' ("European olive"), is a species of Subtropics, subtropical evergreen tree in the Family (biology), family Oleaceae. Originating in Anatolia, Asia Minor, it is abundant throughout the Mediterranean ...

s cover 40% of the island, together with other fruit trees. Forests of Mediterranean pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae.

''World Flora Online'' accepts 134 species-rank taxa (119 species and 15 nothospecies) of pines as cu ...

s, chestnut trees and some oak

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisp ...

s occupy 20%, and the remainder is scrub, grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominance (ecology), dominated by grasses (Poaceae). However, sedge (Cyperaceae) and rush (Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes such as clover, and other Herbaceo ...

or urban. The island is also one of the best in the world for bird watching.

Climate

The island has ahot-summer Mediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate ( ), also called a dry summer climate, described by Köppen and Trewartha as ''Cs'', is a temperate climate type that occurs in the lower mid-latitudes (normally 30 to 44 north and south latitude). Such climates typic ...

(''Csa'' in the Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification divides Earth climates into five main climate groups, with each group being divided based on patterns of seasonal precipitation and temperature. The five main groups are ''A'' (tropical), ''B'' (arid), ''C'' (te ...

). The mean annual temperature is , and the mean annual rainfall is . Its exceptional sunshine makes it one of the sunniest islands in the Aegean Sea. Snow and very low temperatures are rare.

Geology

The entire territory of Lesbos is "Lesvos

The entire territory of Lesbos is "Lesvos Geopark

A geopark is a protected area with internationally significant geology within which Sustainability, sustainable development is sought and which includes tourism, conservation, education and research concerning not just geology but other relevant s ...

", which is a member of the European Geoparks Network (since 2000) and Global Geoparks Network

UNESCO Global Geoparks (UGGp) are geoparks certified by the UNESCO Global Geoparks Council as meeting all the requirements for belonging to the Global Geoparks Network (GGN). The GGN is both a network of geoparks and the agency of the United Nati ...

(since 2004) on account of its outstanding geological heritage, educational programs and projects, and promotion of geotourism.

This geopark was enlarged from former "Lesvos Petrified Forest Geopark". Lesbos contains one of the few known petrified forests, called the Petrified forest of Lesbos, and it has been declared a Protected Natural Monument. Fossilised plants have been found in many localities on the western parts of the island. The fossilised forest was formed during the Late Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

to Lower–Middle Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

, as determined by the intense volcanic activity

Volcanism, vulcanism, volcanicity, or volcanic activity is the phenomenon where solids, liquids, gases, and their mixtures erupt to the surface of a solid-surface astronomical body such as a planet or a moon. It is caused by the presence of a he ...

in the area. Neogene volcanic rock

Volcanic rocks (often shortened to volcanics in scientific contexts) are rocks formed from lava erupted from a volcano. Like all rock types, the concept of volcanic rock is artificial, and in nature volcanic rocks grade into hypabyssal and me ...

s dominate the central and western part of the island, comprising andesite

Andesite () is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predomina ...

s, dacite

Dacite () is a volcanic rock formed by rapid solidification of lava that is high in silica and low in alkali metal oxides. It has a fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic texture and is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyolite. ...

s and rhyolite

Rhyolite ( ) is the most silica-rich of volcanic rocks. It is generally glassy or fine-grained (aphanitic) in texture (geology), texture, but may be porphyritic, containing larger mineral crystals (phenocrysts) in an otherwise fine-grained matri ...

s, ignimbrite

Ignimbrite is a type of volcanic rock, consisting of hardened tuff. Ignimbrites form from the deposits of pyroclastic flows, which are a hot suspension of particles and gases flowing rapidly from a volcano, driven by being denser than the surrou ...

, pyroclastics, tuff

Tuff is a type of rock made of volcanic ash ejected from a vent during a volcanic eruption. Following ejection and deposition, the ash is lithified into a solid rock. Rock that contains greater than 75% ash is considered tuff, while rock co ...

s, and volcanic ash

Volcanic ash consists of fragments of rock, mineral crystals, and volcanic glass, produced during volcanic eruptions and measuring less than 2 mm (0.079 inches) in diameter. The term volcanic ash is also often loosely used to r ...

. The products of the volcanic activity covered the vegetation

Vegetation is an assemblage of plants and the ground cover they provide. It is a general term, without specific reference to particular Taxon, taxa, life forms, structure, Spatial ecology, spatial extent, or any other specific Botany, botanic ...

of the area and the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

ization process took place during favourable conditions. The fossilized plants are silicified remnants of a sub-tropical forest that existed on the northwest part of the island 20–15 million years ago.

Landmarks

* Petrified forest of Lesbos * Catholic Church of Theotokos, where part of the relics of Saint Valentine are kept *Castle of Molyvos (Mithymna) * Castle of Mytilene *Castle of Sigri *Church of Panagia Agiasos *Monastery of Agios Raphael *Monastery of Taxiarchis *Roman Aqueduct of Lesbos (Mória) *The Bridge at Kremasti *Early Christian Basilica of Agios Andreas in Eressos *Temple of Klopedi *Christian Temple of Chalinados * Ancient Sanctuary of Messa *Acropolis of Ancient Pyrra *Monastery of Ipsilou *Monastery of Limonas * Statue of Liberty (Mytilene) *Ouzo Museum "The World of Ouzo" in Plomari *Barbayannis Ouzo Museum (Plomari) *The Mosque in Parakila *Catacomb of Mary Magdalene * Sourlangas Leather FactoryEndangered sites

Twelve historic churches on the island were listed together on the 2008 World Monuments Fund's Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites in the world. The churches date from the Early Christian Period to the 19th century. Exposure to the elements, outmoded conservation methods, and increased tourism are all threats to the structures. The following are the 12 churches: *Katholikon of Moni Perivolis *Early Christian Basilica Agios Andreas Eressos *Early Christian Basilica Afentelli Eressos *Church of Agios Stephanos Mantamados *Katholikon of Moni Taxiarchon Kato Tritos *Katholikon of Moni Damandriou Polichnitos *Metamorphosi Soteros Church in Papiana *Church of Agios Georgios Anemotia *Church of Agios Nikolaos Petra *Monastery of Ipsilou *Church of Agios Ioannis Kerami *Church of Taxiarchon VatousaAdministration

Lesbos is a separate regional unit of theNorth Aegean

The North Aegean Region (, ) is one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece, and the smallest of the thirteen by population. It comprises the islands of the north-eastern Aegean Sea, called the North Aegean islands, except for Thasos an ...

region. Since 2019, it consists of two municipalities

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having municipal corporation, corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality' ...

: Mytilene

Mytilene (; ) is the capital city, capital of the Greece, Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of the Aegean. It was fo ...

and West Lesbos. Between the 2011 Kallikratis government reform and 2019, there was one single municipality on the island: Lesbos, created out of the 13 former municipalities on the island. At the same reform, the regional unit Lesbos was created out of part of the former Lesbos Prefecture.

The municipality of Mytilene consists of the following municipal units (former municipalities):

* Agiasos (Αγιάσος)

* Evergetoulas (Ευεργέτουλας)

*Gera

Gera () is a city in the German state of Thuringia. With around 93,000 inhabitants, it is the third-largest city in Thuringia after Erfurt and Jena as well as the easternmost city of the ''Thüringer Städtekette'', an almost straight string of ...

(Γέρα)

* Loutropoli Thermis (Λουτρόπολη Θερμής)

*Mytilene

Mytilene (; ) is the capital city, capital of the Greece, Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of the Aegean. It was fo ...

(Μυτιλήνη)

* Plomari (Πλωμάρι)

The municipality of West Lesbos consists of the following municipal units:

* Agia Paraskevi (Αγία Παρασκευή)

*Eresos-Antissa

Eresos-Antissa () is a former Communities and Municipalities of Greece, municipality on the island of Lesbos, North Aegean, Greece. From the 2010 local government reform until 2019 it was part of the municipality of Lesbos and since 2019 it is a m ...

(Ερεσός-Άντισσα)

* Kalloni (Καλλονή)

* Mantamados (Μανταμάδος)

* Mithymna (Μήθυμνα)

*Petra

Petra (; "Rock"), originally known to its inhabitants as Raqmu (Nabataean Aramaic, Nabataean: or , *''Raqēmō''), is an ancient city and archaeological site in southern Jordan. Famous for its rock-cut architecture and water conduit systems, P ...

(Πέτρα)

* Polichnitos (Πολίχνιτος)

Economy

The economy of Lesbos is essentially

The economy of Lesbos is essentially agricultural

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created f ...

, with olive oil

Olive oil is a vegetable oil obtained by pressing whole olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea'', a traditional Tree fruit, tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin) and extracting the oil.

It is commonly used in cooking for frying foods, as a cond ...

being the main source of income

Income is the consumption and saving opportunity gained by an entity within a specified timeframe, which is generally expressed in monetary terms. Income is difficult to define conceptually and the definition may be different across fields. F ...

. Tourism in Mytilene

Mytilene (; ) is the capital city, capital of the Greece, Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of the Aegean. It was fo ...

, encouraged by its international airport and the coastal towns of Petra

Petra (; "Rock"), originally known to its inhabitants as Raqmu (Nabataean Aramaic, Nabataean: or , *''Raqēmō''), is an ancient city and archaeological site in southern Jordan. Famous for its rock-cut architecture and water conduit systems, P ...

, Plomari, Molyvos and Eresos, contributes substantially to the island's economy. Fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment (Freshwater ecosystem, freshwater or Marine ecosystem, marine), but may also be caught from Fish stocking, stocked Body of water, ...

and the manufacture

Manufacturing is the creation or production of goods with the help of equipment, labor, machines, tools, and chemical or biological processing or formulation. It is the essence of the

secondary sector of the economy. The term may refer to a r ...

of soap

Soap is a salt (chemistry), salt of a fatty acid (sometimes other carboxylic acids) used for cleaning and lubricating products as well as other applications. In a domestic setting, soaps, specifically "toilet soaps", are surfactants usually u ...

and ouzo, the Greek national liqueur

A liqueur ( , ; ) is an alcoholic drink composed of Liquor, spirits (often rectified spirit) and additional flavorings such as sugar, fruits, herbs, and spices. Often served with or after dessert, they are typically heavily sweetened and un-age ...

, are the remaining sources of income.

Migrants

Due to its proximity to the Turkish mainland, Lesbos is one of the Greek islands most affected by theEuropean migrant crisis

The 2015 European migrant crisis was a period of significantly increased movement of refugees and Human migration, migrants into Europe, mostly from the Middle East. An estimated 1.3 million people came to the continent to request Right of asyl ...

that started in 2015. Refugees of the Syrian Civil War came to the island in multiple vessels every day. As of June 2018, 8,000 refugees were trapped when a deal between Europe and Turkey removed their route to the continent in 2016. After that, living conditions deteriorated and the possibility of movement to Europe dimmed. Moria Refugee Camp was the largest of the refugee camps and held twice as many people as it was designed to accommodate. By May 2020, Moria had 17,421 refugees living there.

On 9 September 2020, thousands of migrants fled from the overcrowded Moria camp after a fire broke out. At least 25 firefighters, with 10 engines, were battling the flames both inside and outside the facility. A smaller-scale facility, the Pikpa camp catered for a segment of the refugee population until its closure in October 2020, whereupon the occupants were transferred to the "old" Kara Tepe Refugee Camp.

The Greek government maintains that the fires were started deliberately by migrants protesting that the camp had been put in lockdown due to a COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. In January 2020, the disease spread worldwide, resulting in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The symptoms of COVID‑19 can vary but often include fever ...

outbreak amongst the migrants in the camp. On 16 September 2020, four Afghan men were formally charged with arson for allegedly starting the fire. Two other migrants, both aged 17, which is below the age of full adult criminal responsibility in Greece, were also allegedly involved in starting the fire, and were held in police detention on the mainland.

After the closure of the Moria camp, a temporary facility was rapidly set up at Kara Tepe. The Greek government announced in November 2020 that a new closed reception centre will be built in the Vastria area near Nees Kydonies, on the border between Mytilene and Western Lesbos, and will be completed by late 2021.

Culture

Cuisine

Local specialties: *''Chachles'', type of tarhana *''Kydonato'', meat with quinces *''Revithato'', meat with chickpeas *'' Sardeles'' from Kalloni * Ladotyri Mytilinis, cheese *''Selinato'', meat with celery *'' Sfougato'', omelette *''Skafoudes'', stuffed eggplants *''Sougania'', stuffed onions * Ouzo *'' Platseda'' (dessert) *'' Finikia'' (dessert) *'' Amygdalota'' *''Retseli''In popular culture

*Films shot on the island include '' Daphnis and Chloe'' (1931) by Orestis Laskos, ''The tree under the sea'' (1985) by Philippe Muyl and ''One Love and the Other'' (1994) by Eva Bergman. *Lesbos is depicted in ''Assassin's Creed Odyssey

''Assassin's Creed Odyssey'' is a 2018 action role-playing game developed by Ubisoft Quebec and published by Ubisoft. It is the eleventh major installment in the ''Assassin's Creed'' series and the successor to ''Assassin's Creed Origins'' (2 ...

'' as the northeasternmost Aegean Island, the center of the island is where the player's character can encounter Medusa

In Greek mythology, Medusa (; ), also called Gorgo () or the Gorgon, was one of the three Gorgons. Medusa is generally described as a woman with living snakes in place of hair; her appearance was so hideous that anyone who looked upon her wa ...

.

Sports

The main football clubs in the island are Aiolikos F.C., Kalloni F.C. and Sappho Lesvou F.C.Media

Radio

TV

A regional television station operates from the city of Mytilene; Aeolos TV.Newspapers

The main printed newspapers of the city are ''Empros'', ''Ta Nea tis Lesvou'', and ''Dimokratis''. Online newspapers include ''Aeolos'', ''Stonisi'', ''Emprosnet'', ''Lesvosnews'', ''Lesvospost'', and ''Kalloninews''.Notable residents

* Lesches (8th or 7th century BC), early poet *Sappho

Sappho (; ''Sapphṓ'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; ) was an Ancient Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied by music. In ancient times, Sapph ...

(7th and 6th centuries BC), poet

* Terpander

Terpander ( ''Terpandros''), of Antissa in Lesbos Island, Lesbos, was a Ancient Greece, Greek poet and citharede who lived about the first half of the 7th century BC. He was the father of Greek music and through it, of lyric poetry, although his o ...

(7th century BC), poet and citharede

A kitharode ( Latinized citharode)

( and ; ) or citharist,

was a classical Greek professional performer (singer) of the cithara, as one who used the cithara to accompany their singing. Famous citharodes included Terpander, Sappho

Sappho ...

* Alcaeus of Mytilene

Alcaeus of Mytilene (; , ''Alkaios ho Mutilēnaios''; – BC) was a lyric poet from the Greek island of Lesbos who is credited with inventing the Alcaic stanza. He was included in the canonical list of nine lyric poets by the scholars of H ...

(7th century BC), poet and politician

* Arion

Arion (; ) was a kitharode in ancient Greece, a Dionysiac poet credited with inventing the dithyramb. The islanders of Lesbos claimed him as their native son, but Arion found a patron in Periander, tyrant of Corinth. Although notable for his mu ...

(7th century BC), poet

* Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

(384–322 BC), philosopher, was born in Chalkidike but lived for a time on the island.

* Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

(370–285 BC), philosopher and botanist, successor to Aristotle

* Theophanes of Mytilene (1st century BC), ancient Greek historian

* Longus

Longus, sometimes Longos (), was the author of an ancient Greek novel or romance, '' Daphnis and Chloe''. Nothing is known of his life; it is assumed that he lived on the isle of Lesbos (setting for ''Daphnis and Chloe'') during the 2nd centu ...

(2nd century AD), ancient Greek author

* Theoctiste of Lesbos (9th century), hermit saint

* Thomais of Lesbos (c. 909–947), lay woman saint

* Constantine IX Monomachos

Constantine IX Monomachos (; 980/ 1000

– 11 January 1055) reigned as Byzantine emperor from June 1042 to January 1055. Empress Zoë Porphyrogenita chose him as a husband and co-emperor in 1042, although he had been exiled for conspiring agai ...

Byzantine emperor (1042–1055), resident of Mytilene prior to accession.

* Christopher of Mytilene (11th century), poet

* Doukas (c. 1400 – after 1462), Byzantine historian

* Hayreddin Barbarossa

Hayreddin Barbarossa (, original name: Khiḍr; ), also known as Hayreddin Pasha, Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1483 – 4 July 1546), was an Ottoman corsair and later admiral of the Ottoman Navy. Barbarossa's ...

(1470s–1546), Ottoman admiral

* Demetrios Bernardakis (1833–1907), dramatist

* Tamburi Ali Efendi (1836–1902), Turkish classical composer

* Gregorios Bernardakis (1848–1925), classical philologist and palaeographer

* Georgios Jakobides (1853–1932), painter

* Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha (1 April 1855 – 1922), Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire

* Theophilos Hatzimihail (c. 1870–1934), painter

* Ahmed Djemal (1872–1922), Ottoman commander, politician

* Georgios Emmanouil Kaldis (1875–1953) lawyer, journalist and politician

* Tériade (1889–1983), art critic, patron, and publisher

* Hermon di Giovanno (c. 1900–1968), painter

* Odysseas Elytis (1911–1996), poet, Nobel Prize in Literature 1979

* Stratis Myrivilis (1890–1969), writer

* Elias Venezis (1904–1973), writer

* Tzeli Hadjidimitriou

Tzeli Hadjidimitriou () is a Greece, Greek independent filmmaker, fine art photographer,and travel writer from Lesbos, Greece. She is known for her work on cultural memory, LGBTQ issues, and rural Greek life. A pioneer in queer Cinema of Greece, ...

(b. 1962), photographer and writer

* Kostas Kenteris (b. 1973), athlete (running, 200 meters), Gold Olympic medal Sydney 2000, World and European championship gold medal

* Alex Martinez, graffiti artist, illustrator, muralist

* Steffen Streich, ultra-endurance cyclist

Gallery

See also

* Adobogiona – an inscription in Lesbos honors thisCelt

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

ic princess

* Aeolic Greek

In linguistics, Aeolic Greek (), also known as Aeolian (), Lesbian or Lesbic dialect, is the set of dialects of Ancient Greek spoken mainly in Boeotia; in Thessaly; in the Aegean island of Lesbos; and in the Greek colonies of Aeolis in Anat ...

* Assos

* Lesbian rule – historically a flexible lead mason's rule associated with Lesbos

* Lesbian wine

Lesbos wine is wine made on the Greek island of Lesbos in the Aegean Sea. The island has a long history of winemaking dating back to at least the 7th century BC when it was mentioned in the works of Homer. During this time the area competed with ...

* List of islands of Greece

Greece has many islands, with estimates ranging from somewhere around 1,200 to 6,000, depending on the minimum size to take into account. The number of inhabited islands is variously cited as between 166 and 227.

The largest Greek island by ...

* List of traditional Greek place names

This is a list of Greek place names as they exist in the Greek language.

*Places involved in the history of Greek culture, including:

**Historic Greek regions, including:

***Ancient Greece, including colonies and contacted peoples

*** Hellenis ...

* University of the Aegean

The University of the Aegean (UA; ) is a public, multi-campus university located in Lesvos, Chios, Samos, Rhodes, Syros and Lemnos, Greece. It was founded on March 20, 1984, by the Presidential Act 83/1984 and its administrative headquarters ar ...

* Ancient regions of Anatolia

References

Works cited

* * * *External links

*Lesvos News

Elstat

*

Guide of Lesbos Island

News of Mytilene and Lesvos Island

* {{Authority control * Islands of Greece Regional units of the North Aegean Lesbianism Global Geoparks Network members Landforms of Lesbos Islands of the North Aegean Geoparks in Greece Territories of the Republic of Genoa Hellenic Navy bases Populated places in Lesbos