King George II Of The Hellenes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George II (; 19 July

George was born at the royal villa at Tatoi, near

George was born at the royal villa at Tatoi, near

George pursued a military career, training with the Prussian Guard at the age of 18, then serving in the

George pursued a military career, training with the Prussian Guard at the age of 18, then serving in the

George was in Romania when Alexander died following an infection from a monkey bite in 1920. Parliament continued to refuse the crown to either George or Constantine, so it was offered to Constantine's third son,

George was in Romania when Alexander died following an infection from a monkey bite in 1920. Parliament continued to refuse the crown to either George or Constantine, so it was offered to Constantine's third son,

Throughout the Axis occupation, George remained the internationally recognised head of state, backed by the

Throughout the Axis occupation, George remained the internationally recognised head of state, backed by the  In occupied Greece, however, the leftist partisans of the National Liberation Front (EAM) and National Popular Liberation Army (ELAS), now unfettered by Metaxas's oppression, had become the largest Greek Resistance movement, enjoying considerable popular support. As liberation drew nearer however, the prospect of George's return caused dissensions both inside Greece and among the Greeks abroad. Although he effectively renounced the Metaxas regime in a radio broadcast, a large section of the people and many politicians rejected his return on account of his support of the dictatorship. In November 1943, George wrote to Tsouderos, "I shall examine anew the question of the date of my return to Greece in agreement with the Government". Either deliberately or accidentally, the version released for publication omitted the words "of the date", creating the impression that George had agreed to a further plebiscite on the monarchy, even though a retraction was issued. After Italy joined the Allies on 8 September 1943, communists in Greece seized weapons of the Axis and gained territorial power within the country. There were growing calls for George to hold a referendum and appoint a regent before he returned to Greece. It was suggested that the regent be the Archbishop of Athens and All Greece, Archbishop Damaskinos, who was a strong supporter of republicanism, and thus George heavily opposed this. Communists became the monarchy's main political opponent and a rival communist-led government, called the

In occupied Greece, however, the leftist partisans of the National Liberation Front (EAM) and National Popular Liberation Army (ELAS), now unfettered by Metaxas's oppression, had become the largest Greek Resistance movement, enjoying considerable popular support. As liberation drew nearer however, the prospect of George's return caused dissensions both inside Greece and among the Greeks abroad. Although he effectively renounced the Metaxas regime in a radio broadcast, a large section of the people and many politicians rejected his return on account of his support of the dictatorship. In November 1943, George wrote to Tsouderos, "I shall examine anew the question of the date of my return to Greece in agreement with the Government". Either deliberately or accidentally, the version released for publication omitted the words "of the date", creating the impression that George had agreed to a further plebiscite on the monarchy, even though a retraction was issued. After Italy joined the Allies on 8 September 1943, communists in Greece seized weapons of the Axis and gained territorial power within the country. There were growing calls for George to hold a referendum and appoint a regent before he returned to Greece. It was suggested that the regent be the Archbishop of Athens and All Greece, Archbishop Damaskinos, who was a strong supporter of republicanism, and thus George heavily opposed this. Communists became the monarchy's main political opponent and a rival communist-led government, called the

From the announcement of Princess Katherine's engagement to British Major Richard Brandram, George's health began declining without his doctors being concerned. On 31 March 1947, George attended a performance of

From the announcement of Princess Katherine's engagement to British Major Richard Brandram, George's health began declining without his doctors being concerned. On 31 March 1947, George attended a performance of

Various stamps bearing the effigy of George II have been issued by Greek Post during his reign:

*A series of four stamps depicting the sovereign was thus issued, shortly after his restoration to the throne, on 1 November 1937, with face values of ₯1, ₯3, ₯8 and ₯100.

*A series of four stamps were issued in 1947 upon George's return to Greece after World War II.

*A commemorative stamp depicting George above Crete was issued in 1950 ''in memoriam'' the Battle of Crete.

*Two stamps were released in 1956 and 1957 that showcased each Greek monarch.

*A series of five stamps were released in 1963 to mark the centenary of the Greek monarchy. Each Greek monarch was depicted.

Various stamps bearing the effigy of George II have been issued by Greek Post during his reign:

*A series of four stamps depicting the sovereign was thus issued, shortly after his restoration to the throne, on 1 November 1937, with face values of ₯1, ₯3, ₯8 and ₯100.

*A series of four stamps were issued in 1947 upon George's return to Greece after World War II.

*A commemorative stamp depicting George above Crete was issued in 1950 ''in memoriam'' the Battle of Crete.

*Two stamps were released in 1956 and 1957 that showcased each Greek monarch.

*A series of five stamps were released in 1963 to mark the centenary of the Greek monarchy. Each Greek monarch was depicted.

Kongelig Dansk Hof-og Statskalendar (1943)

' (in Danish), "De Kongelig Danske Ridderordener", p. 82. ** Knight of the Elephant, with Collar, ''15 August 1909'' ** Cross of Honour of the Order of the Dannebrog, ''15 August 1909'' * : Grand Cross of the

issue 28272, p. 5537 ** Stranger Knight Companion of the Garter, ''7 November 1938'' ** Associate Bailiff Grand Cross of St. John ** Companion of the

Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, they refer to the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries betwe ...

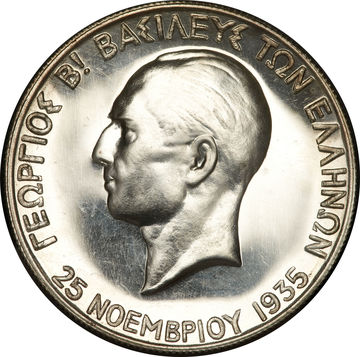

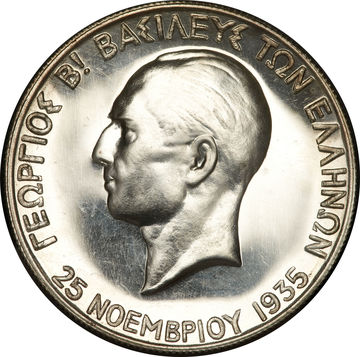

: 7 July] 1890 – 1 April 1947) was King of Greece from 27 September 1922 until 25 March 1924, and again from 25 November 1935 until his death on 1 April 1947.

The eldest son of King Constantine I of Greece and Princess Sophia of Prussia, George followed his father into exile in 1917 following the National Schism

The National Schism (), also sometimes called The Great Division, was a series of disagreements between Constantine I of Greece, King Constantine I and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos over Kingdom of Greece, Greece's foreign policy from 19 ...

, while his younger brother Alexander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here ar ...

was installed as king. Constantine was restored to the throne in 1920 after Alexander's death, but was forced to abdicate two years later in the aftermath of the Greco-Turkish War. George acceded to the Greek throne, but after a failed royalist coup in October 1923 he was exiled to Romania. Greece was proclaimed a republic in March 1924 and George was formally deposed and stripped of Greek nationality. He remained in exile until the Greek monarchy was restored in 1935, following a rigged referendum, upon which he resumed his royal duties. The king supported Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; 12 April 187129 January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who was dictator of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for the first four months of his tenure, and thereafter as th ...

' 1936 self-coup

A self-coup, also called an autocoup () or coup from the top, is a form of coup d'état in which a political leader, having come to power through legal means, stays in power illegally through the actions of themselves or their supporters. The le ...

, which established an authoritarian, nationalist and anti-communist dictatorship

A dictatorship is an autocratic form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, who hold governmental powers with few to no Limited government, limitations. Politics in a dictatorship are controlled by a dictator, ...

known as 4th of August Regime

The 4th of August Regime (), commonly also known as the Metaxas regime (, ''Kathestós Metaxá''), was a dictatorial regime under the leadership of General Ioannis Metaxas that ruled the Kingdom of Greece from 1936 to 1941.

On 4 August 1936, ...

.

Greece was overrun following a German invasion in April 1941, forcing George into his third exile. He left for Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

and then Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

before settling in London, where he headed the Greek government-in-exile

The Greek government-in-exile was formed in 1941, in the aftermath of the Battle of Greece and the subsequent occupation of Greece by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The government-in-exile was based first in South Africa, then London, then, ...

. At the end of the war, George returned to Greece after a 1946 referendum had preserved the monarchy. He died of arteriosclerosis

Arteriosclerosis, literally meaning "hardening of the arteries", is an umbrella term for a vascular disorder characterized by abnormal thickening, hardening, and loss of elasticity of the walls of arteries; this process gradually restricts th ...

in April 1947 at the age of 56. Having no children, he was succeeded by his younger brother, Paul

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo ...

.

Early life

Birth and childhood

George was born at the royal villa at Tatoi, near

George was born at the royal villa at Tatoi, near Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, the eldest son of Crown Prince Constantine of Greece and his wife, Sophia of Prussia

Sophia of Prussia (Sophie Dorothea Ulrike Alice, ; 14 June 1870 – 13 January 1932) was Queen of Greece from 18 March 1913 to 11 June 1917 and again from 19 December 1920 to 27 September 1922 as the wife of King Constantine I.

A member of the H ...

. George was a great-grandson of both Christian IX of Denmark

Christian IX (8 April 181829 January 1906) was King of Denmark from 15 November 1863 until his death in 1906. From 1863 to 1864, he was concurrently Duke of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg.

A younger son of Frederick William, Duke of Schlesw ...

, the "father-in-law of Europe

The father-in-law of Europe is a sobriquet which has been used to refer to two European monarchs of the late 19th and early 20th century: Christian IX of Denmark and Nicholas I of Montenegro, both on account of their children's marriages to foreig ...

", and of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

, the "grandmother of Europe

The sobriquet grandmother of Europe has been given to various women, primarily female sovereigns who are the ascendant of many members of European nobility and royalty, as well as women who made important contributions to Europe.

Royalty

* Elean ...

". George was born nine months after his parents married. Queen Victoria speculated that George was premature, being born a week before his due date. During George's birth, his mother struggled and George's umbilical cord

In Placentalia, placental mammals, the umbilical cord (also called the navel string, birth cord or ''funiculus umbilicalis'') is a conduit between the developing embryo or fetus and the placenta. During prenatal development, the umbilical cord i ...

was strapped around his neck. A German midwife, who was sent specially by his grandmother, Victoria, Princess Royal

Victoria, Princess Royal (Victoria Adelaide Mary Louisa; 21 November 1840 – 5 August 1901) was German Empress and Queen of Prussia as the wife of Frederick III, German Emperor. She was the eldest child of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom ...

, assisted in George's birth. George was named after his paternal grandfather, King George I of Greece

George I (Greek language, Greek: Γεώργιος Α΄, Romanization, romanized: ''Geórgios I''; 24 December 1845 – 18 March 1913) was King of Greece from 30 March 1863 until Assassination of George I of Greece, his assassination on 18 March ...

, following traditional Greek naming practices

In the modern world, Greek names are the personal names among people of Greek language and culture, generally consisting of a given name and a family name.

History

Ancient Greeks generally had a single name, often qualified with a patronymic, ...

. He was baptized on 18 August ld Style: 5 August1890 by multiple Godparents, including Queen Victoria.

George was the eldest of six siblings, born between 1890 and 1913, and spent most of his childhood in Athens in a villa on Kifisias Avenue in the former Presidential Mansion, which was the residence of the Crown Prince. The mansion is now the official residence of the President of Greece

The president of Greece, officially the president of the Hellenic Republic (), commonly referred to in Greek as the president of the Republic (, ΠτΔ), is the head of state of Greece. The president is elected by the Hellenic Parliament; the ...

. As a child, George also made numerous visits to Great Britain, where he stayed for several weeks to visit his British relatives. The Greek royals often stayed in Seaford and Eastbourne

Eastbourne () is a town and seaside resort in East Sussex, on the south coast of England, east of Brighton and south of London. It is also a non-metropolitan district, local government district with Borough status in the United Kingdom, bor ...

. George also made visits to Germany to see his mother's family and they stayed in Schlosshotel Kronberg

Schlosshotel Kronberg (Castle Hotel Kronberg) in Kronberg im Taunus, Hesse, near Frankfurt am Main, was built between 1889 and 1893 for the dowager German Empress Victoria, Princess Royal, Victoria and originally named Schloss Friedrichshof ...

with his grandmother, Victoria, but also took summer holidays in Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

and Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, travelling on their private yacht, ''Amphritrite IV''.

George has been described by historians John Van der Kiste and Vicente Mateos Sáinz de Medrano as the most introverted and distant of his siblings, having been aware of his role as heir from a young age. Van der Kiste presents George as a child who often misbehaved, especially during visits to Germany, but less turbulent than his younger brother, Alexander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here ar ...

, who was described as mischievous, and less sporty his younger sister, Helen, who was seen as a tomboy.

Goudi coup and Balkan Wars

George pursued a military career, training with the Prussian Guard at the age of 18, then serving in the

George pursued a military career, training with the Prussian Guard at the age of 18, then serving in the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

as a member of the 1st Infantry Regiment. George received a military education as the heir to the throne. He was trained at the Hellenic Military Academy

The Hellenic Army Academy (, ΣΣΕ), commonly known as the Evelpidon, is a military academy. It is the Officer cadet school of the Greek Army and the oldest third-level educational institution in Greece. It was founded in 1828 in Nafplio by Io ...

in Athens, which allowed him to enroll in Greece's infantry as a second lieutenant on 27 May nowiki/>Old Style: 14 May1909. However, a few months after he joined, on 15 August nowiki/>Old Style: 2 August1909, a group of military officers organised a coup d'état against George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George of Beltan (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgoruk ...

, the concurrent king and grandfather of George. The coup d'état became known as the Goudi coup

The Goudi coup () was a military coup d'état by a group of military officers that took place on the night of , at the barracks in Goudi, located on the eastern outskirts of Athens, Greece. The coup was pivotal in modern Greek history, ending th ...

and was led by Nikolaos Zorbas, who declared himself a monarchist, but campaigned for the dismissal of all princes from the army. Zorbas argued that dismissing princely soldiers would protect the popularity of the royal family. However, it is argued by Van der Kiste that many of the officers involved in the coup blamed the high-ranking princes for the defeat of Greece in the 1897 Greco-Turkish War

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War (), was a war fought between the Kingdom of Greece and the O ...

. They particularly placed blame on George's father, Crown Prince Constantine, believing that the royal family was monopolising the highest army positions.

Some of the officers involved in the coup believed that the country would be better off if King George I was deposed and replaced by another neutral candidate, such as by George, his grandson. Proposed candidates included the Austrian duke Francis of Teck or a member of the German royal House of Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, ; , ; ) is a formerly royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) German dynasty whose members were variously princes, Prince-elector, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern Castle, Hohenzollern, Margraviate of Bran ...

. However, George was the most desirable candidate as he was more popular than his father, was an adult and was politically inexperienced, so was seen as easily more controllable. Violence sparked by the coup continued until February 1910 and members of the royal family were forced to resign from the military in order to avoid a revolution. George, his siblings and his parents evacuated Greece and moved to Germany for three years in exile. To avoid controversy, their exile was branded as a three-year "education leave", which was approved and so George continued his military training, but with the prestigious First Foot Guards Regiment of the Prussian army. This period of absence from Greece reduced his popularity as a potential replacement for his grandfather.

As Greece became more politically stable as violent protests lessened, George, his siblings and his parents returned to Greece at the end of 1910. In 1911, Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Cretan State, Cretan Greeks, Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. As the leader of the Liberal Party (Greece), Liberal Party, Venizelos ser ...

allowed members of the royal family to be given back their former ranks in the military, but George returned to Germany to continue training with the Prussian army. When the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League (the Kingdoms of Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Greece, Greece and Kingdom of Montenegro, Montenegro) agai ...

commenced in October 1912, George returned to Greece to fight against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. George and his brother, Alexander, served as officers on his father's staff. George served in numerous battles, which was criticised by the media as it put the country's future monarch as risk of being killed. One such battle that George participated in was the capture of Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

on 8 November nowiki/>Old Style: 26 October1912, which marked major progress for Greece in the war.

Crown Prince

World War I

On 18 March nowiki/>Old Style: 5 March1913, George's grandfather and the reigning king, George I, was assassinated while taking his daily walk in Thessaloniki. Crown Prince Constantine, whose popularity had grown due to Greece's successes in the First Balkan War, acceded to the throne as King Constantine I. George thus became theCrown Prince of Greece

The Crown Prince of Greece () is the heir apparent or presumptive to the defunct throne of Greece. Since the abolition of the Greek monarchy by the then-ruling military regime on 1 June 1973, it is merely considered a courtesy title.

Title ...

at age 23. In the early weeks of being crown prince, George and his family moved to their new residence, where George developed a close friendship with his uncle, Prince Christopher, who was only two years older than him. On 30 June nowiki/>Old Style: 17 June1913, the Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict that broke out when Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia and Kingdom of Greece, Greece, on 1 ...

broke out between Bulgaria and its former allies, which included Greece. Relations between Greece and many of its Balkan allies grew during the war, notably with Romania, which paved the way towards the marriage between George and his future wife, Elisabeth of Romania

Elisabeth of Romania (Elisabeth Charlotte Josephine Alexandra Victoria; , , Romanization, romanized: ''Elisábet''; 12 October 1894 – 14 November 1956) was the second child and eldest daughter of Ferdinand I of Romania, King Ferdinand I an ...

, the daughter of King Ferdinand I and Queen Marie of Romania

Marie (born Princess Marie Alexandra Victoria of Edinburgh; 29 October 1875 – 18 July 1938) was the last queen of Romania from 10 October 1914 to 20 July 1927 as the wife of King Ferdinand I.

Marie was born into the British royal fa ...

. When Greece and its allies won the war in August 1913, George and his family resumed their European trips. George accompanied his father on a state visit to Berlin and received the Order of the Red Eagle

The Order of the Red Eagle () was an order of chivalry of the Kingdom of Prussia. It was awarded to both military personnel and civilians, to recognize valor in combat, excellence in military leadership, long and faithful service to the kingdom, o ...

from his uncle, Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as th ...

, the German Kaiser. The following summer, George travelled to the United Kingdom with Christopher and was in London when he heard of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was one of the key events that led to World War I. Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg ...

of Austria on 28 June 1914.

The assassination sparked the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, in which Constantine wished to maintain Greece's neutrality. Constantine believed that Greece was unready to fight after its involvement in the Balkan Wars and also feared displeasing his brother-in-law, Wilhelm II. Opposition soon accused Constantine of supporting the Triple Alliance, made up of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy, and relations between him and Venizelos, who believed that Greece should side with the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

, made up of Great Britain, France and Russia, quickly deteriorated. The entire Greek government, supported by the French government, soon declared in October 1916 that siding with the Entente was their preferred option. Central Greece was occupied by the Western Allies

Western Allies was a political and geographic grouping among the Allied Powers of the Second World War. It primarily refers to the leading Anglo-American Allied powers, namely the United States and the United Kingdom, although the term has also be ...

, an extension of the Triple Entente, and a National Schism

The National Schism (), also sometimes called The Great Division, was a series of disagreements between Constantine I of Greece, King Constantine I and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos over Kingdom of Greece, Greece's foreign policy from 19 ...

between supporters of Constantine and supporters of Venizelos broke out. Constantine refused to alter his opinion and his popularity heavily decreased. A fire in Tatoi Palace broke out on 14 July nowiki/>Old Style: 1 July1916 and French agents were blamed for it. Multiple members of the royal family were close fatalities of it. Though George was not present at the time, his younger sister, Princess Katherine, who was only three years old, was carried into the palace woods for two kilometres to be saved. Between sixteen and eighteen people, made up of firefighters and palace staff, died.

On 19 June nowiki/>Old Style: 6 June1917, French politician and leader of the Entente Charles Jonnart

Charles Célestin Auguste Jonnart (27 December 1857 – 30 December 1927) was a French politician.

Early years

Born into a bourgeois family in Fléchin, Pas-de-Calais, Charles Jonnart was educated at Saint-Omer, then in Paris. Interested in th ...

ordered George's father, Constantine, to abdicate. Due to worry of the impending Allied invasion at Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; ; , Ancient: , Katharevousa: ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens city centre along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf in the Ath ...

, Constantine agreed to be placed in exile without having to abdicate. The Allies were against establishing a republic in Greece and thus looked for a replacement. George's name was put forward, but the Allies perceived him as a germanophile

A Germanophile, Teutonophile, or Teutophile is a person who is fond of Culture of Germany, German culture, Germans, German people and Germany in general, or who exhibits German patriotism in spite of not being either an ethnic German or a German ...

, like his father, due to his links to the Prussian army and German imperial family. George's uncle, Prince George, was offered the position, but he refused out of loyalty to Constantine. Ultimately, George's younger brother, Alexander, was chosen by Venizelos and the Entente to replace Constantine.

On 10 June nowiki/>Old Style: 28 May1917, Alexander officially ascended to the throne in a small ceremony that was only attended by George and former prime minister Alexandros Zaimis

Alexandros Zaimis (, Romanization, romanized: ''Aléxandros Zaímis''; 28 October 1855 – 15 September 1936) was a Greeks, Greek politician who served as Greece's Prime Minister of Greece, Prime Minister, Minister of the Interior (Greece), Minist ...

. In addition, , the Archbishop of Athens and All Greece

The Archbishopric of Athens () is a Greek Orthodox archiepiscopal see based in the city of Athens, Greece. It is the senior see of Greece, and the seat of the autocephalous Church of Greece. Its incumbent (since 2008) is Ieronymos II of Athens. ...

, did not attend. The ceremony is kept secret from the public and there are no state celebrations that occur. Alexander, who was only 23 years old, was described as having a "broken voice" and teary eyes when he took the oath of loyalty to the constitution. Historians, such as Van der Kiste, argue that he was fearful of dealing with his opponents and the fact that his reign was illegitimate according to succession laws. Neither Constantine nor George had renounced their rights to the throne, and Constantine told Alexander that he viewed him as the country's regent, not monarch. On the evening of the ceremony, Alexander moved from the future presidential mansion in inner Athens to Tatoi. George and all other members of the royal family had planned to leave for exile, however crowds of people protested outside the mansion to prevent them from leaving, so they had to escape in secret the following day. They reached the port of Oropos

Oropos () is a small town and a municipality in East Attica, Greece.

The village of Skala Oropou, within the bounds of the municipality, was the site an important ancient Greek city, Oropus, and the famous nearby sanctuary of Amphiaraos is sti ...

and fled the country due to the war. This was the final time that George had contact with his brother, Alexander.

First exile

George and his family settled in Switzerland, first inSaint Moritz

St. Moritz ( , , ; ; ; ; ) is a high Alps, Alpine resort town in the Engadine in Switzerland, at an elevation of about above sea level. It is Upper Engadine's major town and a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in the Maloja Regi ...

and then in Zürich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

. Almost all members of the royal family moved with them after Venizelos returned to power as head of the Cabinet and organised Greece's entry into World War I. The family were financially strained and Constantine soon became ill. He almost died in 1918 upon also contracting the Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or by the common misnomer Spanish flu, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 subtype of the influenza A virus. The earliest docum ...

. At the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres () was a 1920 treaty signed between some of the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire, but not ratified. The treaty would have required the cession of large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, ...

and Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine

The Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine (; ) was a treaty between the victorious Allies of World War I on the one hand, and Bulgaria, one of the defeated Central Powers in World War I, on the other. The treaty required Bulgaria to cede various territor ...

, part of the end of World War I, Greece made territorial gains in Thrace and Anatolia. Although initially seen as gains to the country, Greece soon fell into the Second Greco-Turkish War in 1919. Tension between Venizelos and the royal family remained high and was not helped when Alexander decided to marry aristocrat Aspasia Manos

Aspasia Manou (; 4 September 1896 – 7 August 1972) was a Greek aristocrat who became the wife of Alexander I, King of Greece. Due to the controversy over her marriage, she was styled Madame Manou instead of "Queen Aspasia", until recognized ...

, rather than a foreign royal, which dismayed Venizelos. Venizelos saw this decision as a missed opportunity to move closer to Great Britain.

According to historian Marlene Eilers Koenig, George was in love with his cousin Anastasia de Torby, however their relationship was opposed by George's mother, Sophia, as Anastasia was the result of a morganatic marriage

Morganatic marriage, sometimes called a left-handed marriage, is a marriage between people of unequal social rank, which in the context of royalty or other inherited title prevents the principal's position or privileges being passed to the spou ...

. George later became engaged in October 1920 to Elisabeth of Romania, who had been in touch with George since 1911. George had previously asked Elisabeth to marry in 1914, but she declined off the advice of her great-aunt, Elisabeth of Wied

Elisabeth of Wied (Pauline Elisabeth Ottilie Luise; 29 December 18432 March 1916) was the first Queen of Romania as the wife of King Carol I from 15 March 1881 to 27 September 1914. She had been the princess consort of Romania since her marriage ...

, who thought of George as being two small and too English. Elisabeth herself had declared that George was a prince whom God had forgotten to complete. Her feelings remain the same when the pair meet in Switzerland, however she accepted on the basis of her own imperfections. Although George's family had lost most of their wealth in exile, the Romanian royal family

The Romanian royal family () constitutes the Romanian subbranch of the Swabian branch of the House of Hohenzollern (also known as the ''House of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen''), and was the ruling dynasty of the Kingdom of Romania, a constitutional ...

swiftly invited George and Elisabeth to return to Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

, in Romania, to announce their engagement.

Greco-Turkish war

George was in Romania when Alexander died following an infection from a monkey bite in 1920. Parliament continued to refuse the crown to either George or Constantine, so it was offered to Constantine's third son,

George was in Romania when Alexander died following an infection from a monkey bite in 1920. Parliament continued to refuse the crown to either George or Constantine, so it was offered to Constantine's third son, Paul

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo ...

, who refused to break the legitimate line of succession. Greece was making no progress in the Greco-Turkish War and in the 1920 Greek legislative election

Parliamentary elections were held in Greece on Sunday, 14 November 1920, or 1 November 1920 old style. They were possibly the most crucial elections in the modern history of Greece, influencing not only the few years afterwards, including the G ...

, Venizelos was voted out of office. Dimitrios Rallis

Dimitrios Rallis (Greek: Δημήτριος Ράλλης; 1844–1921) was a Greek politician, founder and leader of the Neohellenic or "Third Party".

Family

He was born in Athens in 1844. He was descended from an old Greek political family. ...

, a monarchist, was appointed prime minister and the 1920 Greek referendum

A referendum on the return of King Constantine I was held in Greece on Sunday, 5 December 1920 (22 November o.s.). It followed the death of his son, King Alexander. The proposal was approved by nearly 99% of voters.Nohlen & Stöver, p838 The ant ...

restored Constantine to the throne. According to Van der Kiste, the referendum was most likely rigged by Rallis. Before Venizelos fled to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

in exile, he asked George's grandmother, Olga Constantinovna, to act as regent while Constantine returned to Greece. On 19 December, George returned to Greece as the crown prince under his father's second reign. Many portraits of Venizelos were torn down in state celebrations and replaced with photos of the royal family. Upon their return, the royals made numerous balcony appearances to please the large crowd that had turned out to see them return.

A few weeks later, on 27 February nowiki/>Old Style: 14 February1921, George married Elisabeth in Bucharest. Two weeks later, George's younger sister, Helen, married Elisabeth's brother, Crown Prince Carol of Romania, in Athens. Constantine's restoration to the Greek throne was opposed by the former Allies of World War I, and thus Greece received minimal support in the Greco-Turkish War against Mustafa Kemal

Mustafa () is one of the names of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and the name means "chosen, selected, appointed, preferred", used as an Arabic given name and surname. Mustafa is a common name in the Muslim world.

Given name Moustafa

* Moustafa A ...

's Turkey. The former Allies stated that they were not ready to provide support, and continued to hold distaste against Constantine. For example, at the wedding of Princess Helen and Crown Prince Carol, the British ambassador and his wife refused to greet Constantine and Sophia.

In response to the ongoing war, Constantine quickly assumed the role of commander-in-chief of the army and resided in Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

from May to September 1921. George served as a colonel, and later a major general in the war. He travelled with his father to Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

and other battlefronts, where he visited wounded Greek soldiers and civilians in hospital. Greece was pushed back from the Anatolian lands granted to them in the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres () was a 1920 treaty signed between some of the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire, but not ratified. The treaty would have required the cession of large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, ...

to Ankara

Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and List of national capitals by area, the largest capital by area in the world. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5,290,822 in its urban center ( ...

and suffered heavy defeats at the Battle of Sakarya

The Battle of the Sakarya (), also known as the Battle of the Sangarios (), was an important engagement in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922).

The battle went on for 21 days from August 23 to September 13, 1921, close to the banks of the Sakar ...

in August and September 1921. The royal family became more criticised and Greek media turned against George and two of his uncles when they made comments critiquing Venizelos. Prince Andrew

Prince Andrew, Duke of York (Andrew Albert Christian Edward; born 19 February 1960) is a member of the British royal family. He is the third child and second son of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and a younger broth ...

, the father of the future Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 19219 April 2021), was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he was the consort of the British monarch from h ...

, fled from Asia Minor before Greece's defeat at Sakarya, which was mocked by Turkish forces. In the next few months, Greek forces continued to be defeated and slowly retreated towards Smyrna, while George was stationed in Ionia

Ionia ( ) was an ancient region encompassing the central part of the western coast of Anatolia. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionians who ...

and Elisabeth joined the Red Cross

The organized International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 16million volunteering, volunteers, members, and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ...

to help Christian refugees who had escaped villages that had fallen to the Turkish army. Elisabeth's distance from George furthers her struggles of integrating into the Greek culture. Mateos Sáinz de Medrano documents that Elisabeth was jealous of the successes of her sister, Queen Maria of Yugoslavia.

Elisabeth had been pregnant since her and George's marriage, but suffered a miscarriage while travelling to Smyrna. Some historians argue that her miscarriage was actually the abortion of an illegitimate child that was the result of an affair between her and British diplomat Frank Rattigan, the father of Terence Rattigan

Sir Terence Mervyn Rattigan (10 June 191130 November 1977) was a British dramatist and screenwriter. He was one of England's most popular mid-20th-century dramatists. His plays are typically set in an upper-middle-class background.Geoffrey Wan ...

. Elisabeth soon contracted typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often ther ...

, pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (Pulmonary pleurae, pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant d ...

and depression, before returning to Bucharest. Though George and Elisabeth's mother were attempting to convince her to return to Greece, her health never fully recovered after her miscarriage. Simultaneously, Turkish forces had organised an invasion of Smyrna, which fell on 9 September nowiki/>Old Style: 27 August1922. Around two weeks later, the city was ransacked and burned. An estimated tens of thousands of Greeks and Armenians were killed, which influenced a greater degree of republicanism in Athens. When the Turks again defeated Greece at the Battle of Dumlupınar

The Battle of Dumlupınar (, ), or known as Field Battle of the Commander-in-Chief () in Turkey, was one of the important battles in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) (part of the Turkish War of Independence). The battle was fought from 26 ...

, a sector of the military, led by colonels Nikolaos Plastiras

Nikolaos Plastiras (; 4 November 1883 – 26 July 1953) was a Greek general and politician, who served three times as Prime Minister of Greece. A distinguished soldier known for his personal bravery, he became famous as "The Black Rider" d ...

and Stylianos Gonatas, demanded the abdication of Constantine and the dissolution of the parliament.

First reign

To avoid more unrest, Constantine officially abdicated on 27 September nowiki/>Old Style: 14 September1922 and moved to Italy with Sophia and his daughters in exile, while George prepared to become the monarch. George left for Bucharest to retrieve his wife and the pair returned to Greece to be crowned. George officially ascended to the throne as George II, but did not receive a happy reception and faced harsh criticism. In Greece, there had been greater political instability since the 1922 Greek coup d'état, which influenced Constantine's abdication, and a large influx of refugees from Asia Minor as a result of the war. Supporters of Venizelos still maintained a high degree of influence and power in the country, with Plastiras and Gonatas leading the country. George and Elisabeth were confined to Tatoi and were highly monitored by the government, while George worried about the growing instability in Greece and criticism from the former Allies, who had previously refused to recognise Constantine's second reign. Between 13 October and 28 November 1922, theTrial of the Six

The Trial of the Six (, ''Díki ton Éx(i)'') or the Execution of the Six was the trial for treason, in late 1922, of the Anti-Venizelist officials held responsible for the Greek military defeat in Asia Minor. The trial culminated in the death ...

took place and saw the punishment of numerous monarchist politicians who had opposed the Venizelos administration. The verdict of the trial resulted in former prime ministers Dimitrios Gounaris

Dimitrios Gounaris (; 5 January 1867 – 28 November 1922) was a Greek politician who served as the prime minister of Greece from 25 February to 10 August 1915 and 26 March 1921 to 3 May 1922. The leader of the People's Party, he was the ma ...

, Petros Protopapadakis and Nikolaos Stratos

Nikolaos Stratos (; 16 May 1872 – 28 November 1922 (15 November Old Style dating)) was a Prime Minister of Greece for a few days in May 1922. He was later tried and executed for his role in the Catastrophe of 1922.

Early political career

Born ...

, as well as politicians Georgios Baltatzis, Nikolaos Theotokis and Georgios Hatzanestis, being shot on 28 November. All six of them had been strong supporters of the monarchy and their executions were to the dismay of George, who had lost his right to pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

and could not intervene in the trial. Continued opposition to the royal family was occurring, such as the arrest of Prince Andrew on 26 October at the royal residence of Mon Repos on Corfu. Andrew was later transported to Athens and imprisoned for "disobeying an order" and "acting on his own initiative" during battles in Anatolia. The Greek government was criticised by George V of the United Kingdom

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

George was born during the reign of his pa ...

, Alfonso XIII of Spain

Alfonso XIII ( Spanish: ''Alfonso León Fernando María Jaime Isidro Pascual Antonio de Borbón y Habsburgo-Lorena''; French: ''Alphonse Léon Ferdinand Marie Jacques Isidore Pascal Antoine de Bourbon''; 17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also ...

and Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI (; born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, ; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939) was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 until his death in February 1939. He was also the first sovereign of the Vatican City State u ...

, before Andrew's sentence was reduced to capital banishment in order to avoid sanctions. On 5 December nowiki/>Old Style: 22 November a British ship was sent to transport Andrew and his family, including the young Prince Philip, out of Greece and to Britain, to the dismay of George.

Constantine died in Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

on 11 January 1923 nowiki/>Old Style: 29 December 1922without being granted a state funeral, which left George considering abdication. General Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; 12 April 187129 January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who was dictator of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for the first four months of his tenure, and thereafter as th ...

, who was a supporter of the monarchy, encouraged George to stay in the country with the hope that instability would gradually reduce. Following a failed royalist coup d'état in October 1923, the Greek government, led by the republican prime minister, Gonatas, asked George to leave the country while the National Assembly considered the question of the future form of government. Though most likely uninvolved, George was accused of initiating the coup d'état, and Plastiras and Theodoros Pangalos

Theodoros Pangalos (, romanized: ''Theódoros Pángalos''; 11 January 1878 – 26 February 1952) was a Greek general, politician and dictator. A distinguished staff officer and an ardent Venizelist and anti-royalist, Pangalos played a leading r ...

openly campaigned for the abolition of the monarchy for the first time. The 1923 Greek legislative election determined that Venizelos would replace Gonatas, however before the changeover in government, Gonatas demanded that George leave the country. George complied and although he refused to abdicate, George departed on 19 December 1923 for exile in his wife's home nation of Romania. Before fleeing, George was described as a cold and aloof man, who rarely inspired love or affection from his subjects. Many commented that his moody, sullen personality seemed more appropriate for his ancestral homeland of Denmark than Greece. Furthermore, George's long years spent living abroad had caused him to struggle in identifying with the Greek culture.

Second exile

TheSecond Hellenic Republic

The Second Hellenic Republic is a modern Historiography, historiographical term used to refer to the Greece, Greek state during a period of republican governance between 1924 and 1935. To its contemporaries it was known officially as the Hellenic ...

was proclaimed by parliament on 25 March 1924, before being confirmed by the 1924 Greek republic referendum

Nineteen or 19 may refer to:

* 19 (number)

* One of the years 19 BC, AD 19, 1919, 2019

Films

* ''19'' (film), a 2001 Japanese film

* ''Nineteen'' (1987 film), a 1987 science fiction film

* '' 19-Nineteen'', a 2009 South Korean film

* '' D ...

two and a half weeks later. George and Elisabeth were officially deposed and banished, along with all members of the royal family, who were stripped of their Greek citizenship. Royal properties were also confiscated by the government of the new republic. Rendered stateless, they were issued new passports from their cousin, Christian X of Denmark

Christian X (; 26 September 1870 – 20 April 1947) was King of Denmark from 1912 until his death in 1947, and the only King of Iceland as Kristján X, holding the title as a result of the personal union between Denmark and independent Icel ...

. Exiled in Romania from December 1923, George and his wife settled in Bucharest, where Elisabeth's parents, King Ferdinand and Queen Marie, put at their disposal a wing of the Cotroceni Palace

Cotroceni Palace (Romanian language, Romanian: ''Palatul Cotroceni'') is the official residence of the President of Romania. It is located at ''Bulevardul Geniului, nr. 1'', in Bucharest, Romania. The palace also houses the National Cotroceni Mu ...

for some time. After several weeks however, the couple moved and established their residence in a more modest villa on Victory Avenue. As regular guests of the Romanian sovereigns, George and Elisabeth took part in the ceremonies which punctuated the life of the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen

Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen () was a principality in southwestern Germany. Its rulers belonged to the junior House of Hohenzollern#Swabian branch, Swabian branch of the House of Hohenzollern. The Swabian Hohenzollerns were elevated to princes in 162 ...

family. Despite the kindness with which his mother-in-law treated him, George felt idle in Bucharest and struggled to hide the boredom he felt from the splendors of the Romanian court.

After their exile, financial difficulties and absence of children, George and Elisabeth's marriage deteriorated. Elisabeth carried out multiple extra-marital affairs with various married men. When visiting her sick sister, Maria, in Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

, she reportedly flirted with her own brother-in-law, Alexander I of Yugoslavia

Alexander I Karađorđević (, ; – 9 October 1934), also known as Alexander the Unifier ( / ), was King of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from 16 August 1921 to 3 October 1929 and King of Yugoslavia from 3 October 1929 until his assassinati ...

. Later, she began an affair with her husband's banker, a Greek named Alexandros Scavani, whom she made her chamberlain to cover up the scandal. In exile, George stayed half the year in Romania with Elisabeth, and the other half living with his mother at Villa Bobolina in Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

, either with or without his wife. George eventually moved to the United Kingdom, where he had numerous extended family members and friends. On 16 September 1930, George was initiated into Freemasonry

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

in London and became venerable master of the Wellwood Lodge in 1933. After the death of Sophia in 1932, George chose to permanently leave Bucharest and his wife to establish his residence in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. Accompanied by his squire, Major Dimitrios Levidis, and one of his servants, Mitso Panteleos, George rented a small suite with two rooms at Brown's Hotel in Mayfair

Mayfair is an area of Westminster, London, England, in the City of Westminster. It is in Central London and part of the West End. It is between Oxford Street, Regent Street, Piccadilly and Park Lane and one of the most expensive districts ...

.

George still lacked much wealth and received a mixed reception in Britain, where he was criticised for his relations with Wilhelm II. In London, George was finally reunited with Andrew and his wife. George also regularly attended hunting trips in Scotland with his companions and members of the British royal family

The British royal family comprises Charles III and other members of his family. There is no strict legal or formal definition of who is or is not a member, although the Royal Household has issued different lists outlining who is considere ...

, who he frequently went to pubs and antique dealers with. George became quite knowledgeable in old furniture and English silverware. George avoided mentioning his political views or any plans for restoring the Greek monarchy, but made himself clear that he would return as monarch if asked to and that he still considered himself Greek. George attended the wedding of his cousin, Marina

A marina (from Spanish , Portuguese and Italian : "related to the sea") is a dock or basin with moorings and supplies for yachts and small boats.

A marina differs from a port in that a marina does not handle large passenger ships or cargo ...

, and George, Duke of Kent, in Greek army uniform. After the wedding celebrations had concluded, George left on a trip to British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

for several months. Under Freeman Freeman-Thomas, the Viceroy and Governor-General of India

The governor-general of India (1833 to 1950, from 1858 to 1947 the viceroy and governor-general of India, commonly shortened to viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom in their capacity as the emperor o ...

, George was treated as the sovereign of Greece and met numerous officials stationed there, while being enthusiastically interested in the Indian culture. During his stay, George fell in love with a young woman named Joyce Wallach, who was married to John Britten-Jones, the aide-de-camp to the Governor of India. Wallach filed for divorce and moved back to London with George, however would continue to have numerous affairs up until George's death in 1947. On 6 July 1935, George learned through the newspaper that Elisabeth had filed for divorce after she accused him of "desertion from the family home". A court in Bucharest processed the divorce without inviting George to attend.

Second reign

Restoration of the monarchy

After the abolition of the monarchy in 1924, leaders who opposed Venizelos, except for Metaxas, refused to recognise the new regime. This "regime issue" that arose just after the proclamation of the republic, haunted Greek politics for more than a decade and eventually led to the restoration of monarchy. In just over ten years, Greece had twenty-three governments, thirteen coup d'états and one dictatorship. On average, each Cabinet lasted six months and a coup d'état was organised every 42 weeks. Having failed to restore political instability, the republicanism movement in Greece became criticised and opposed by the public. Gradually, there were more and more protests that voiced to restore the monarchy. Although most protestors wished to have George reinstalled, there were voices to have a new monarch from a new dynasty be inducted, such as George, Duke of Kent. On 10 October 1935, GeneralGeorgios Kondylis

Georgios Kondylis (, romanized: ''Geórgios Kondýlis''; 14 August 1878 – 1 February 1936) was a Greek general, politician and prime minister of Greece. He was nicknamed ''Keravnos'', Greek for " thunder" or " thunderbolt".

Military ca ...

, a former supporter of Venizelos who had suddenly decided to support the monarchist forces, overthrew the government and appointed himself prime minister, replacing Panagis Tsaldaris

Panagis Tsaldaris (also Panagiotis Tsaldaris or Panayotis Tsaldaris; ; 5 March 1868 – 17 May 1936) was a Greek politician who served as Prime Minister of Greece twice. He was a revered conservative politician and leader for many years (1922– ...

and Zaimis, who were prime minister and president respectively. Aware of Kondylis' ultimate aim of restoring the monarchy, George, who had been living at Brown's Hotel, demanded a plebiscite be held in order to determine whether he would be reinstalled. Kondylis thus arranged the rigged 1935 Greek plebiscite

A referendum on restoring the monarchy was held in Greece on 3 November 1935.Dieter Nohlen & Phillip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p830 The proposal was approved by nearly 97.9% of voters, although the conduct during ...

, both to approve his government and to bring an end to the republic. On 3 November 1935, almost 98% of the reported votes supported the restoration of the monarchy. The balloting was not secret, and participation was compulsory. As ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' described it at the time, "As a voter one could drop into the ballot box a blue vote for George II and please General George Kondylis ... or one could cast a red ballot for the Republic and get roughed up."

The organisation of the plebiscite discontented the Greek government. When the election results were announced, a delegation was sent to the Greek embassy in London to officially ask George and his younger brother, Paul, to return to Athens, which they accepted on 5 November 1935. Before returning to Greece, they first travelled to France and Italy. In Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, George and Prince Andrew were greeted by French President Albert Lebrun

Albert François Lebrun (; 29 August 1871 – 6 March 1950) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1932 to 1940. He was the last president of the Third Republic. He was a member of the centre-right Democratic Republica ...

and interviewed by French media. George and Paul then travelled to Villa Sparta, Italy, to retrieve their sisters and pay respects to their parents' graves at the Church of the Nativity of Christ and St. Nicholas, a Russian Orthodox

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

Church in Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

. After a brief stay in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

with Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albania ...

, the Greek royals boarded the cruiser ''Elli

In Norse mythology (a subset of Germanic mythology), Elli (Old Norse: , "old age"Orchard (1997:38).) is a personification of old age who, in the ''Prose Edda'' book ''Gylfaginning'', defeats Thor in a wrestling match.Graeme Davis (2013). ''Thor: ...

'' in Brindisi

Brindisi ( ; ) is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Historically, the city has played an essential role in trade and culture due to its strategic position ...

and returned to Phalerum

Phalerum or Phaleron ( ' ; ''()'', ) was a port of Ancient Athens, 5 km southwest of the Acropolis of Athens, on a bay of the Saronic Gulf. The bay is also referred to as "Bay of Phalerum" ( '').''

The area of Phalerum is now occupied by ...

in Athens on 25 November.

Kondylis lost his status as Regent of Greece, but ensured that George kept him as prime minister, before awarding him with the Grand Cross of the Order of George I

The Royal Order of George I () is a Greek Order (distinction), order instituted by King Constantine I of Greece, Constantine I in 1915. Since the monarchy's abolition in 1973, it has been considered a dynastic order of the former Greek royal fami ...

. Almost immediately after being restored, George and Kondylis disagreed over the terms of a general amnesty that George wanted to declare, so Kondylis resigned on 30 November 1935 and George appointed Konstantinos Demertzis

Konstantinos Demertzis (; January 12, 1876, in Athens – April 13, 1936, in Athens) was a Greek academic and politician. He was the 49th Prime Minister of Greece from November 1935 to April 1936. Demertzis died during his mandate, of a heart att ...

as interim prime minister. The 1936 Greek legislative election

Parliamentary elections were held in Greece on 26 January 1936.Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p830 The Liberal Party emerged as the largest party in Parliament, winning 126 of the 300 seats.Nohlen ...

confirmed that communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

was gaining popularity within the country. This was perhaps due to the continuing large influx of refugees from Asia Minor, who had been arriving since 1922. In the election, the Communist Party of Greece

The Communist Party of Greece (, ΚΚΕ; ''Kommounistikó Kómma Elládas'', KKE) is a Marxist–Leninist political party in Greece. It was founded in 1918 as the Socialist Workers' Party of Greece (SEKE) and adopted its current name in Novem ...

(KKE) gained fifteen seats, which established it as a buffer between monarchists and republicans. Political instability ensued after the unexpected, but natural, deaths of Demertzis, Kondylis, Venizelos and Tsaldaris. George appointed Metaxas as prime minister on 13 April 1936. Metaxas was opposed by the country's communist forces, who were against his policies. Metaxas also told George that he wished to suspend certain articles of the constitution in order to establish a dictatorship.

Metaxas dictatorship

On 4 August 1936, George endorsed Metaxas's dictatorship, known as the "4th of August Regime

The 4th of August Regime (), commonly also known as the Metaxas regime (, ''Kathestós Metaxá''), was a dictatorial regime under the leadership of General Ioannis Metaxas that ruled the Kingdom of Greece from 1936 to 1941.

On 4 August 1936, ...

", signing decrees that dissolved the parliament, banned political parties, abolished the constitution and purported to create a "Third Hellenic Civilization". George, ruling jointly with Metaxas, oversaw a right-wing

Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property ...

regime in which political opponents were arrested and strict censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governmen ...

was imposed. Many books, such as the works of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

and Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

, were banned. Though not branded as a fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

regime, Metaxas's dictatorship was arguably quasi-fascist and heavily imitated that of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

in Italy, whom Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

had also been inspired by in Germany. George disliked dealing with both Greek politicians and ordinary Greeks, and preferred to let Metaxas undertake tours around the country.. George retained full control of the army and he was largely responsible for foreign policy making. Metaxas's support of the monarch has been likened to that of Venizelos with Alexander. Although his reign was mostly guaranteed under the dictatorship, George was weary of Metaxas' growing power and the influence of the army. George told his cousin, Princess Victoria Louise of Prussia

Princess Victoria Louise of Prussia (; 13 September 1892 – 11 December 1980) was the only daughter and youngest child of Wilhelm II, German Emperor, and Augusta Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein. Through her father, Victoria Louise was a great-g ...

, that he felt so isolated that he could not trust anyone in Greece. To avoid a possible overthrow by Metaxas, George declared to the Greek ambassador to the United Kingdom that he supported Metaxas's policies, though he also voiced his concern.

Most of the royal family's possessions had been either ransacked, lost or sold during the republic. For example, the Presidential Palace in Athens had been almost completely emptied, its furniture sold by the republican Greek government. When the monarchy was restored, George nor any member of the royal family requested compensation for their lost property. Lacking wealth, George took charge of the restoration and redecoration works of his residencies, which he refurnished by gaining items from auctions and markets. George continued his relationship with Wallach, but it was kept secret from the public and any possible marriage between the pair would not be allowed due to Wallach's commoner status. When engagements required a first lady to be present, George would call his sister Katherine or his sister Irene

Irene is a name derived from εἰρήνη (eirēnē), Greek for "peace".

Irene, and related names, may refer to:

* Irene (given name)

Places

* Irene, Gauteng, South Africa

* Irene, South Dakota, United States

* Irene, Texas, United States

...

, who were both single at the time. George made very frequent visits back to London, at least once every year, typically at the end of the year, to reunite with his extended family and friends. He was weary of Metaxas when taking these trips and would never be away from Greece for too long. His trips though allowed for the acquisition by Greece of more military equipment and vehicles from Britain. One of George's priorities was to retrieve the bodies of his mother and father from Italy. In November 1936, he sent Paul to Florence to recover the bodies of their parents, Constantine and Sophie, and of their grandmother, Olga. They were transferred to Greece by the ship '' Averof'' and exhibited for the public for six days in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens

The Metropolitan Cathedral of the Annunciation (), popularly known as the Metropolis or Mitropoli (), is the cathedral church of the Archbishopric of Athens and all of Greece.

History

Construction of the cathedral began on Christmas Day, 1842 ...

. On 23 November, a small ceremony was held at the Church of the Resurrection at Tatoi. It was attended by members of the royal family and foreign European royals and nobles. George would go on, in 1940, to retrieve the remains of his aunt, Alexandra, who had died in Russia in 1891, from the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. This satisfied the wishes of his grandmother.

With George's divorce, his relationship with a commoner and his lack of offspring, Paul assumed the role of heir apparent to the throne, however he too was still single. Succession laws were semi-Salic

The Salic law ( or ; ), also called the was the ancient Frankish civil law code compiled around AD 500 by Clovis, the first Frankish King. The name may refer to the Salii, or "Salian Franks", but this is debated. The written text is in Late L ...

, meaning that one of their uncles or cousins would have to inherit the throne after Paul, however all their uncles were aging and their cousins were estranged from the country. After facing pressure to marry, Paul wedded Frederica of Hanover

Frederica of Hanover (German: ''Friederike Luise''; , romanized: ''Freideríki Luísa''; 18 April 1917 – 6 February 1981) was Queen of Greece from 1 April 1947 until 6 March 1964 as the wife of King Paul and the Queen Mother of Greece from ...

, the daughter of his cousin, Victoria Louise, and Ernest Augustus, Duke of Brunswick

Ernest Augustus (Ernest Augustus Christian George; ; 17 November 1887 – 30 January 1953) was Duke of Brunswick from 2 November 1913 to 8 November 1918. He was a grandson of George V of Hanover, thus a Prince of Hanover and a Prince of the Unit ...

, on 9 January 1938. Though a notable amount of dignitaries were in Athens for their wedding, many Greeks feared having another queen who was German and who was the granddaughter of Wilhelm II. Hitler, now the Führer

( , spelled ''Fuehrer'' when the umlaut is unavailable) is a German word meaning "leader" or " guide". As a political title, it is strongly associated with Adolf Hitler, the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. Hitler officially cal ...

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, also wished to take advantage of the wedding by incorporating Nazi swastikas

The swastika (卐 or 卍, ) is a symbol used in various Eurasian religions and cultures, as well as a few Indigenous peoples of Africa, African and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, American cultures. In the Western world, it is widely rec ...

into the ceremony. George was quick to oppose this and managed to avoid any Nazi influence on the day. On 1 July 1939, George's sister, Irene, married Prince Aimone, Duke of Aosta

Prince Aimone, 4th Duke of Aosta (''Aimone Roberto Margherita Maria Giuseppe Torino''; 9 March 1900 – 29 January 1948), was a prince of Italy's reigning House of Savoy and an officer of the Royal Italian Navy. The second son of Prince Eman ...

, a cousin of Victor Emmanuel III and the future King of Croatia

This is a complete list of dukes and kings of Croatia () under domestic ethnic and elected Dynasty, dynasties during the Duchy of Croatia (until 925), the Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102), the Croatia in personal union with Hungary, Kingdom of Croa ...

. Their wedding in Florence was to the dismay of Mussolini, who forbade the Greek flag from being raised on Italian soil. As a result, George threatened to boycott the ceremony, but Metaxas advised him to attend to avoid further deterioration in Greco-Italian relations.

World War II