John Y. Brown Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Young Brown Jr. (December 28, 1933 – November 22, 2022) was an American politician, entrepreneur, and businessman from

Concurrent with his post-KFC business ventures, Brown purchased an ownership stake in several professional basketball teams. He owned three professional basketball teams, one of those being the Boston Celtics. In 1970, Wendell Cherry assembled a group that included Brown to buy the

Concurrent with his post-KFC business ventures, Brown purchased an ownership stake in several professional basketball teams. He owned three professional basketball teams, one of those being the Boston Celtics. In 1970, Wendell Cherry assembled a group that included Brown to buy the

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virgini ...

. He served as the 55th governor of Kentucky

The governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of government of Kentucky. Sixty-two men and one woman have served as governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re-el ...

from 1979 to 1983, and built Kentucky Fried Chicken

KFC (Kentucky Fried Chicken) is an American fast food restaurant chain headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky, that specializes in fried chicken. It is the world's second-largest restaurant chain (as measured by sales) after McDonald's, with ...

(KFC) into a multimillion-dollar restaurant chain.

The son of United States Congressman John Y. Brown Sr., Brown's talent for business became evident in college, where he made a substantial amount of money selling ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The ( Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various ...

'' sets. After briefly practicing law with his father, he purchased Kentucky Fried Chicken from founder Harland Sanders

Colonel Harland David Sanders (September 9, 1890

December 16, 1980) was an American businessman, best known for founding fast food chicken restaurant chain Kentucky Fried Chicken (also known as KFC) and later acting as the company's brand amba ...

in 1964. Brown turned the company into a worldwide success and sold his interest in the company for a huge profit in 1971. He then invested in several other restaurant ventures, but none matched the success of KFC. During the 1970s, he also owned, at various times, three professional basketball teams: the American Basketball Association

The American Basketball Association (ABA) was a major men's professional basketball league from 1967 to 1976. The ABA ceased to exist with the American Basketball Association–National Basketball Association merger in 1976, leading to four A ...

's Kentucky Colonels

The Kentucky Colonels were a member of the American Basketball Association for all of the league's nine years. The name is derived from the historic Kentucky colonels. The Colonels won the most games and had the highest winning percentage of ...

, and the National Basketball Association

The National Basketball Association (NBA) is a professional basketball sports league, league in North America. The league is composed of 30 teams (29 in the United States and 1 in Canada) and is one of the major professional sports leagues i ...

's Boston Celtics

The Boston Celtics ( ) are an American professional basketball team based in Boston. The Celtics compete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) as a member of the league's Eastern Conference Atlantic Division. Founded in 1946 as one of ...

and Buffalo Braves (currently the Los Angeles Clippers

The Los Angeles Clippers are an American professional basketball team based in Los Angeles. The Clippers compete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) as a member of the Pacific Division in the league's Western Conference. The Clipper ...

).

Despite having previously shown little inclination toward politics, Brown surprised political observers by declaring his candidacy for governor in the 1979 election. With the state and nation facing difficult economic times, Brown promised to run the state government like a business. A strong media campaign funded by his personal fortune allowed him to win the Democratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

primary

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Work ...

and go on to defeat former Republican governor Louie B. Nunn

Louie Broady Nunn (March 8, 1924 – January 29, 2004) was an American politician who served as the 52nd governor of Kentucky. Elected in 1967, he was the only Republican to hold the office between the end of Simeon Willis's term in 1947 and t ...

in the general election. Because he owed few favors to established political leaders, he appointed many successful businesspeople to state posts instead of making political appointments. Following through on his campaign promise to make more diverse appointments, he named a woman and an African-American to his cabinet. During his tenure, Brown exerted less influence over the legislature than previous governors and was frequently absent from the state, leaving Lieutenant Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

Martha Layne Collins

Martha Layne Collins (née Hall; born December 7, 1936) is an American former businesswoman and politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky; she was elected as the state's 56th governor from 1983 to 1987, the first woman to hold the office and ...

as acting governor

An acting governor is a person who acts in the role of governor. In Commonwealth jurisdictions where the governor is a vice-regal position, the role of "acting governor" may be filled by a lieutenant governor (as in most Australian states) or an ...

for more than one-quarter of his term. He briefly competed for the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

after his gubernatorial term in the 1984 election but withdrew from the race after only six weeks, citing health issues. He continued to invest in business ventures, the most high profile of which was Kenny Rogers Roasters, a wood-roasted chicken restaurant he founded with country music

Country (also called country and western) is a genre of popular music that originated in the Southern and Southwestern United States in the early 1920s. It primarily derives from blues, church music such as Southern gospel and spirituals, o ...

star Kenny Rogers

Kenneth Ray Rogers (August 21, 1938 – March 20, 2020) was an American singer, songwriter, and actor. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2013. Rogers was particularly popular with country audiences but also charted m ...

.

Brown married three times, the second time to former Miss America

Miss America is an annual competition that is open to women from the United States between the ages of 17 and 25. Originating in 1921 as a "bathing beauty revue", the contest is now judged on competitors' talent performances and interviews. As ...

Phyllis George

Phyllis Ann George (June 25, 1949 – May 14, 2020) was an American businesswoman, actress, and sportscaster. In 1975, George was hired as a reporter and co-host of the CBS Sports pre-show ''The NFL Today'', becoming one of the first women ...

. Among his children are news anchor Pamela Ashley Brown and former Secretary of State of Kentucky

The secretary of state of Kentucky is one of the constitutional officers of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It is now an elected office, but was an appointed office prior to 1891. The current secretary of state is Republican Michael Adams, who was ...

John Young Brown III

John Young Brown III (born June 2, 1963) is an American politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Brown served as Secretary of State of Kentucky from 1996 to 2004. In 2007, Brown ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination for Lieut ...

.

Early life

Brown was born on December 28, 1933, inLexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County. By population, it is the second-largest city in Kentucky and 57th-largest city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 28th-largest ...

."Kentucky Governor John Y. Brown Jr.". National Governors Association. He was the only son of five children born to John Y. and Dorothy Inman Brown.Demaret, "Kissin', but Not Cousins, John Y. and Phyllis George Aim to Do Kentucky Up Brown". His father was a member of the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

from Kentucky and a member of the Kentucky state legislature

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky. It comprises the Kentucky Senate and the Kentucky House of Representatives.

The General Assembly meets annually in the ...

for nearly three decades, including a term as Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hunger ...

. John Sr. was named for, but not related to, the nineteenth century governor of the same name.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 373. A 1979 ''People

A person ( : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of proper ...

'' magazine article recounts that the elder Brown's nine unsuccessful political races – for either governor or the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

– took a toll on his family and left his mother resentful of all the money spent on campaigns.

Brown attended Lafayette High School in Lexington, where he was a seventeen-time letterman in various sports.Berman, p. B1. During one summer, his father expressed disappointment that he had decided to spend the summer selling vacuum cleaners instead of working on a road construction crew with the rest of his football teammates. Motivated by his father's disapproval, Brown averaged $1,000 in monthly commissions from vacuum cleaner sales. After high school, Brown matriculated at the University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a public land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Kentucky, the university is one of the state's ...

, where he earned a bachelor's degree in 1957 and a law degree in 1960.Harrison in ''The Kentucky Encyclopedia'', p. 130. As an undergraduate, he was a member of the golf

Golf is a club-and-ball sport in which players use various clubs to hit balls into a series of holes on a course in as few strokes as possible.

Golf, unlike most ball games, cannot and does not use a standardized playing area, and coping ...

team and Phi Delta Theta

Phi Delta Theta (), commonly known as Phi Delt, is an international secret and social fraternity founded at Miami University in 1848 and headquartered in Oxford, Ohio. Phi Delta Theta, along with Beta Theta Pi and Sigma Chi form the Miami Tria ...

fraternity. While in law school, he made as much as $25,000 a year selling Encyclopædia Britannica

The ( Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various ...

sets and employed a sales crew made up of classmates to increase his profits.

Brown joined his father's law practice after earning his law degree. From 1959 to 1965, he also served in the United States Army Reserve

The United States Army Reserve (USAR) is a reserve force of the United States Army. Together, the Army Reserve and the Army National Guard constitute the Army element of the reserve components of the United States Armed Forces.

Since July 2020, ...

. He served as legal counsel for Paul Hornung

Paul Vernon Hornung (December 23, 1935 – November 13, 2020), nicknamed "the Golden Boy", was an American professional football player who was a Hall of Fame running back for the Green Bay Packers of the National Football League (NFL) from 1 ...

when Hornung was suspended for the 1963

Events January

* January 1 – Bogle–Chandler case: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation scientist Dr. Gilbert Bogle and Mrs. Margaret Chandler are found dead (presumed poisoned), in bushland near the Lane Co ...

National Football League

The National Football League (NFL) is a professional American football league that consists of 32 teams, divided equally between the American Football Conference (AFC) and the National Football Conference (NFC). The NFL is one of the ma ...

season for gambling.Golden, "Brown Yearns for Old Kentucky Home". After only a few years, Brown left his father's law firm and began a career in business.

Business ventures

In 1960, Brown married Eleanor Bennett Durall and had three children includingJohn Young Brown III

John Young Brown III (born June 2, 1963) is an American politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Brown served as Secretary of State of Kentucky from 1996 to 2004. In 2007, Brown ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination for Lieut ...

, Eleanor Faris, and Sandra Bennett.Tachau, p. 222. He got his wife involved in managing a barbecue

Barbecue or barbeque (informally BBQ in the UK, US, and Canada, barbie in Australia and braai in South Africa) is a term used with significant regional and national variations to describe various cooking methods that use live fire and smoke ...

restaurant; upon seeing its success, he became convinced of the financial potential of the fast food

Fast food is a type of mass-produced food designed for commercial resale, with a strong priority placed on speed of service. It is a commercial term, limited to food sold in a restaurant or store with frozen, preheated or precooked ingredie ...

industry.Weston, "Welcome to the Conglomerate". During a 1963 political breakfast, Brown met Colonel Harland Sanders, the founder of Kentucky Fried Chicken

KFC (Kentucky Fried Chicken) is an American fast food restaurant chain headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky, that specializes in fried chicken. It is the world's second-largest restaurant chain (as measured by sales) after McDonald's, with ...

(KFC), and the two discussed selling Sanders' chicken in Brown's chain of barbecue restaurants. By 1964, Brown persuaded Jack C. Massey

Jack Carroll Massey (June 15, 1904 – February 15, 1990) was an American venture capitalist and entrepreneur who owned Kentucky Fried Chicken, co-founded the Hospital Corporation of America, and owned one of the largest franchisees of Wendy's.Gl ...

to purchase KFC from Sanders for $2 million (). The investment group changed the restaurant's format from the diner-style restaurant envisioned by Sanders to a fast-food take out model."KFC Corporation". Company Profiles for Students. Giving all their restaurants a distinct red-and-white striped color pattern, the group opened over 1,500 restaurants, including locations in all 50 U.S. states and several international locations. By 1967, KFC had become the nation's sixth-largest restaurant chain by volume and first offered its stock for public purchase in 1969.

For his work with KFC, Brown was named one of the Outstanding Young Men of America by the Junior Chamber of Commerce

The United States Junior Chamber, also known as the Jaycees, JCs or JCI USA, is a leadership training, service organization and civic organization for people between the ages of 18 and 40. It is a branch of Junior Chamber International (JCI). ...

in 1966; the following year, the Chamber named him one of the Outstanding Civic Leaders of America."John Young Brown Jr. Hall of Distinguished Alumni. Eventually, he became a member of both the Kentucky and Louisville Chambers of Commerce. The Louisville Junior Chamber of Commerce honored him as Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border. ...

's Outstanding Young Man in 1969, and he was inducted into the University of Kentucky Alumni Association Hall of Distinguished Alumni on November 6, 1970.

In 1971, Brown sold his interest in KFC to Heublein Heublein Inc. (also known as Heublein Spirits) was an American producer and distributor of alcoholic beverages and food throughout the 20th century. During the 1960s and 1970s its stock was regarded as one of the most stable financial investments, ...

for $284 million ().Williams, "Business Update – Brown Backs Rogers' New Chicken Chain". Using some of the profits from the KFC sale, Brown and some associates bought the Miami-based Lum's

Lum's was an American family restaurant chain based in Florida with additional locations in several states. It was founded in 1956 in Miami Beach, Florida, by Stuart and Clifford S. Perlman when they purchased Lum's hot dog stand for $10,000. ...

chain of restaurants from its founders, Stuart and Clifford S. Perlman, for $4 million. Of the 340-outlet beer-and-hot-dog chain, Brown said "they did not have very good food. I figured that upgrading it would be my first task." Accordingly, he hired a group of young executives to find "the perfect hamburger". After a three-month courtship, he hired Ollie Gleichenhaus, owner of Ollie's Sandwich Shop, a small diner in Miami Beach, Florida

Miami Beach is a coastal resort city in Miami-Dade County, Florida. It was incorporated on March 26, 1915. The municipality is located on natural and man-made barrier islands between the Atlantic Ocean and Biscayne Bay, the latter of which sep ...

, to train Lum's staff to prepare his "Ollie Burger" hamburgers. He later started a chain of take-out restaurants called Ollie's Trolley, named for Gleichenhaus. Initially successful, Brown said "that venture llie's Trolleycollapsed".Book, "You get your learnin' from your burnin'". Lions Clubs International

The International Association of Lions Clubs, more commonly known as Lions Clubs International, is an international non-political service organization established originally in 1916 in Chicago, Illinois, by Melvin Jones. It is now headquarte ...

in Tampa, Florida

Tampa () is a city on the Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The city's borders include the north shore of Tampa Bay and the east shore of Old Tampa Bay. Tampa is the largest city in the Tampa Bay area and the seat of Hillsborough C ...

, honored Brown with its Service to America Award in 1974. Brown sold the Lum's chain for $9.5 million to Friedrich Jahn's Wienerwald holding group in 1978. A few years later, Brown launched John Y's Chicken, a venture which also subsequently failed. Kenny Rogers Roasters, another chain founded with country music superstar Kenny Rogers

Kenneth Ray Rogers (August 21, 1938 – March 20, 2020) was an American singer, songwriter, and actor. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2013. Rogers was particularly popular with country audiences but also charted m ...

proved more successful.

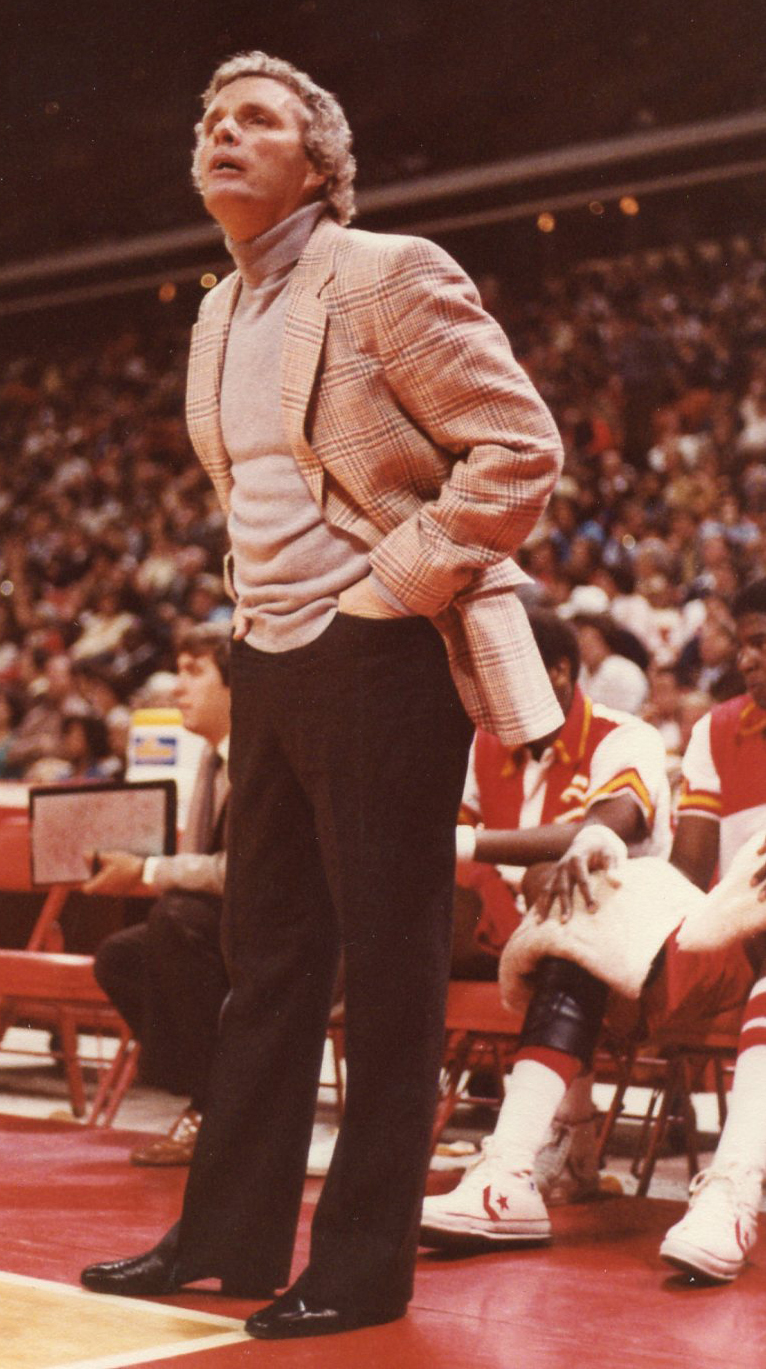

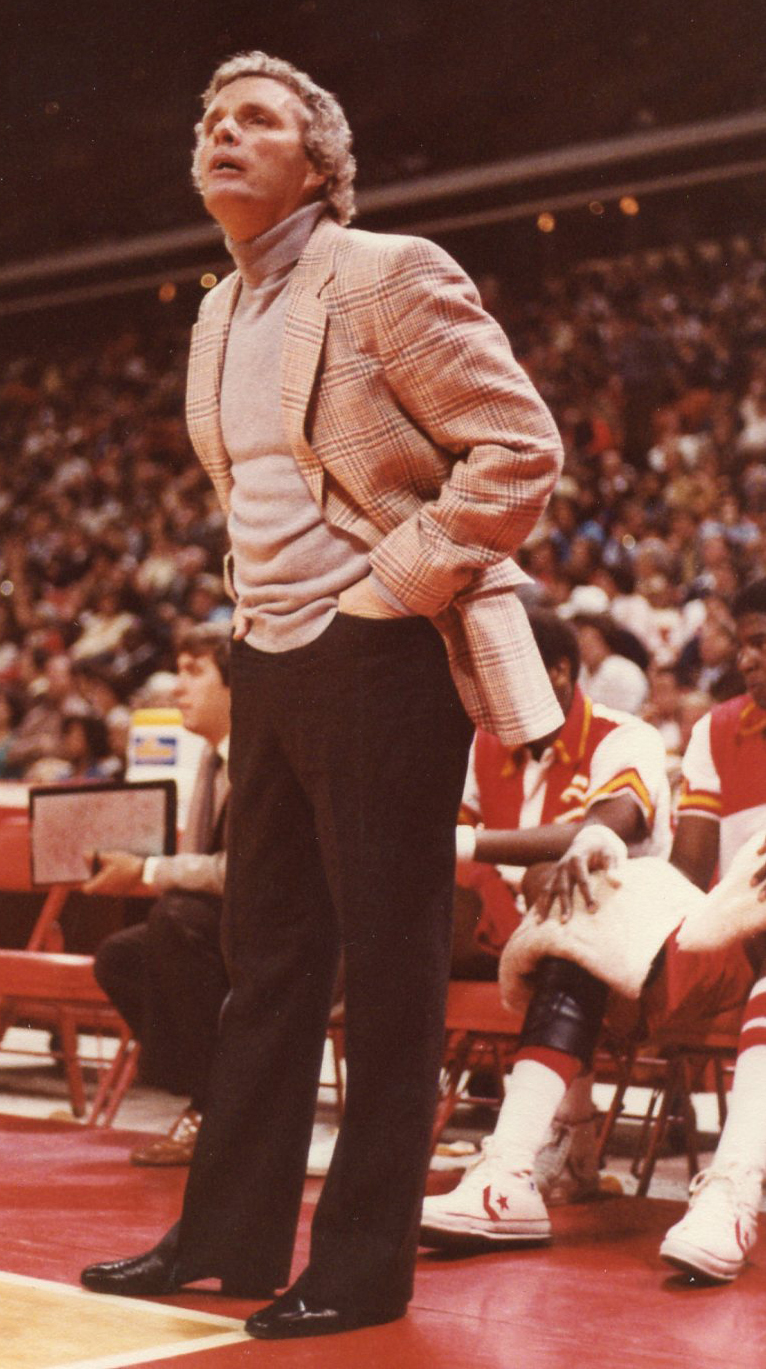

Basketball ventures

Concurrent with his post-KFC business ventures, Brown purchased an ownership stake in several professional basketball teams. He owned three professional basketball teams, one of those being the Boston Celtics. In 1970, Wendell Cherry assembled a group that included Brown to buy the

Concurrent with his post-KFC business ventures, Brown purchased an ownership stake in several professional basketball teams. He owned three professional basketball teams, one of those being the Boston Celtics. In 1970, Wendell Cherry assembled a group that included Brown to buy the American Basketball Association

The American Basketball Association (ABA) was a major men's professional basketball league from 1967 to 1976. The ABA ceased to exist with the American Basketball Association–National Basketball Association merger in 1976, leading to four A ...

's (ABA) Kentucky Colonels

The Kentucky Colonels were a member of the American Basketball Association for all of the league's nine years. The name is derived from the historic Kentucky colonels. The Colonels won the most games and had the highest winning percentage of ...

.Pluto, p. 330. Following the 1972–73 season, Cherry sold his interest in the Colonels to a group from Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state lin ...

; Brown immediately purchased Cherry's interest from the group, reportedly to keep the team from moving to Cincinnati.Pluto, p. 338. He put his wife and a 10-woman board of directors in charge of the team.Pluto, p. 339. Colonels general manager Mike Storen felt that this was a sign that Brown was going to run the team "his way" and left the team as a result; two months later, he accepted the job of ABA league commissioner.Carry, "Having a Ball With the ABA". Head coach Joe Mullaney followed soon after, saying that Brown was going to be too meddlesome in personnel decisions. Babe McCarthy

James Harrison "Babe" McCarthy (October 1, 1923 – March 17, 1975), was an American professional and collegiate basketball coach. McCarthy was originally from Baldwyn, Mississippi. McCarthy may best be remembered for Mississippi State's appearanc ...

lasted only one season as Mullaney's replacement; in 1975, Brown hired Hubie Brown

Hubert Jude Brown (born September 25, 1933) is an American retired basketball coach and player and a current television analyst. Brown is a two-time NBA Coach of the Year, the honors being separated by 26 years. Brown was inducted into the Naism ...

as head coach. The team won the ABA championship the following year.Pluto, p. 344.

Although he had been hailed as a hero, first for saving the Colonels from moving to Cincinnati and then for bringing a championship to Louisville, Brown came under intense public criticism following the Colonels' championship season for selling the rights to center Dan Issel

Daniel Paul Issel (born October 25, 1948) is an American former professional basketball player and coach. An outstanding collegian at the University of Kentucky, Issel was twice named an All-American en route to a school-record 25.7 points per ...

to the Baltimore Claws in a cost-saving move.Pluto, p. 345. He frequently clashed with coach Hubie Brown during the 1975–76 season, and at the end of the year, he accepted $3 million to fold the team during the 1976 ABA–NBA merger

The ABA-NBA merger was a major pro sports business maneuver in 1976 when the American Basketball Association (ABA) combined with the National Basketball Association (NBA), after multiple attempts over several years. The NBA and ABA had entered m ...

rather than paying $3 million for the team to join the National Basketball Association

The National Basketball Association (NBA) is a professional basketball sports league, league in North America. The league is composed of 30 teams (29 in the United States and 1 in Canada) and is one of the major professional sports leagues i ...

(NBA).Pluto, p. 346.

After folding the Colonels, Brown stated that basketball was not the kind of business he wanted to be involved in.Pluto, p. 347. Despite this declaration, he purchased half-ownership in the NBA's Buffalo Braves

The Buffalo Braves were an American professional basketball franchise based in Buffalo, New York. The Braves competed in the National Basketball Association (NBA) as a member club of the league's Eastern Conference Atlantic Division from 1970 ...

later in 1976.Usiak, p. 22. The Braves had posted a dismal 30–52 record in the 1975–76 season, and Brown immediately set out to make moves that would improve the franchise's fortunes in the next season.Kirkpatrick and Papanek, "Scouting Reports". He re-signed All Star guard Randy Smith, who had threatened to leave as a free agent, then traded the club's first-round draft pick to the Milwaukee Bucks

The Milwaukee Bucks are an American professional basketball team based in Milwaukee. The Bucks compete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) as a member of the league's Eastern Conference Central Division. The team was founded in 1968 ...

for center Swen Nater

Swen Erick Nater (born January 14, 1950) is a Dutch former professional basketball player. He played primarily in the American Basketball Association (ABA) and National Basketball Association (NBA), and is the only player to have led both the NBA ...

. In a single day, he made two significant trades. In the first, he swapped reigning Rookie of the Year Adrian Dantley

Adrian Delano Dantley (born February 28, 1955) is an American former professional basketball player and coach who played 15 seasons in the National Basketball Association (NBA). Dantley is a six-time NBA All-Star, a two-time All-NBA selection and ...

for the Indiana Pacers

The Indiana Pacers are an American professional basketball team based in Indianapolis. The Pacers compete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) as a member of the league's Eastern Conference Central Division. The Pacers were first est ...

' Billy Knight, who was second in the league in scoring the previous season. Four hours later, he acquired Nate "Tiny" Archibald from the New York Nets

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

for George Johnson and a first-round draft pick in 1979. In 1977, Brown purchased the remaining share of the team from the owner Paul Snyder.

The following year, Brown traded franchises with Boston Celtics

The Boston Celtics ( ) are an American professional basketball team based in Boston. The Celtics compete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) as a member of the league's Eastern Conference Atlantic Division. Founded in 1946 as one of ...

owner Irv Levin

Irving H. Levin (September 8, 1921 – March 20, 1996) was an American film producer and business executive with the National General Corporation. He was also the owner of the National Basketball Association's Boston Celtics and San Diego Clippers ...

.Distel, p. B5. The move allowed Levin to move his franchise to his home state of California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the ...

, while giving Brown ownership of one of the league's most storied franchises. Two weeks before the swap of franchises was made official, details of a six-player trade between the two were reported.Reid, "Will Red And Brown Harmonize?" Boston sent Freeman Williams

Freeman Williams Jr. (May 15, 1956 – April 19, 2022) was an American professional basketball player in the National Basketball Association (NBA). He played college basketball for the Portland State Vikings, where he was a two-time All-Americ ...

, Kevin Kunnert, and Kermit Washington to the Braves for "Tiny" Archibald, Billy Knight, and Marvin Barnes

Marvin Jerome "Bad News" Barnes (July 27, 1952 – September 8, 2014) was an American professional basketball player. A forward, he was an All-American at Providence College, and played professionally in both the American Basketball Association ...

. The move turned Boston fans against Brown, both because Kunnert and Washington were seen as key pieces of the team's future and because team president and legendary former coach Red Auerbach

Arnold Jacob "Red" Auerbach (September 20, 1917 – October 28, 2006) was an American professional basketball coach and executive. He served as a head coach in the National Basketball Association (NBA), most notably with the Boston Celtics. ...

publicly stated that he was not consulted about the trade. The relationship between Brown and Auerbach worsened with Brown's decision to trade three first-round draft picks that Auerbach had planned to use to rebuild the franchise for Bob McAdoo

Robert Allen McAdoo Jr. ( ; born September 25, 1951) is an American former professional basketball player and coach. He played 14 seasons in the National Basketball Association (NBA), where he was a five-time NBA All-Star and named the NBA Most ...

. Again, Brown made the trade without consulting Auerbach.May, "Vindicated McAdoo Happily Heading for the Hall". Auerbach almost left Boston to take a job with the New York Knicks

The New York Knickerbockers, shortened and more commonly referred to as the New York Knicks, are an American professional basketball team based in the New York City borough of Manhattan. The Knicks compete in the National Basketball Associa ...

as a result. Brown eventually sold his interest in the team to co-owner Harry Mangurian in 1979."Celtics Shuffle Bad Combination". ''The Prescott Courier''.

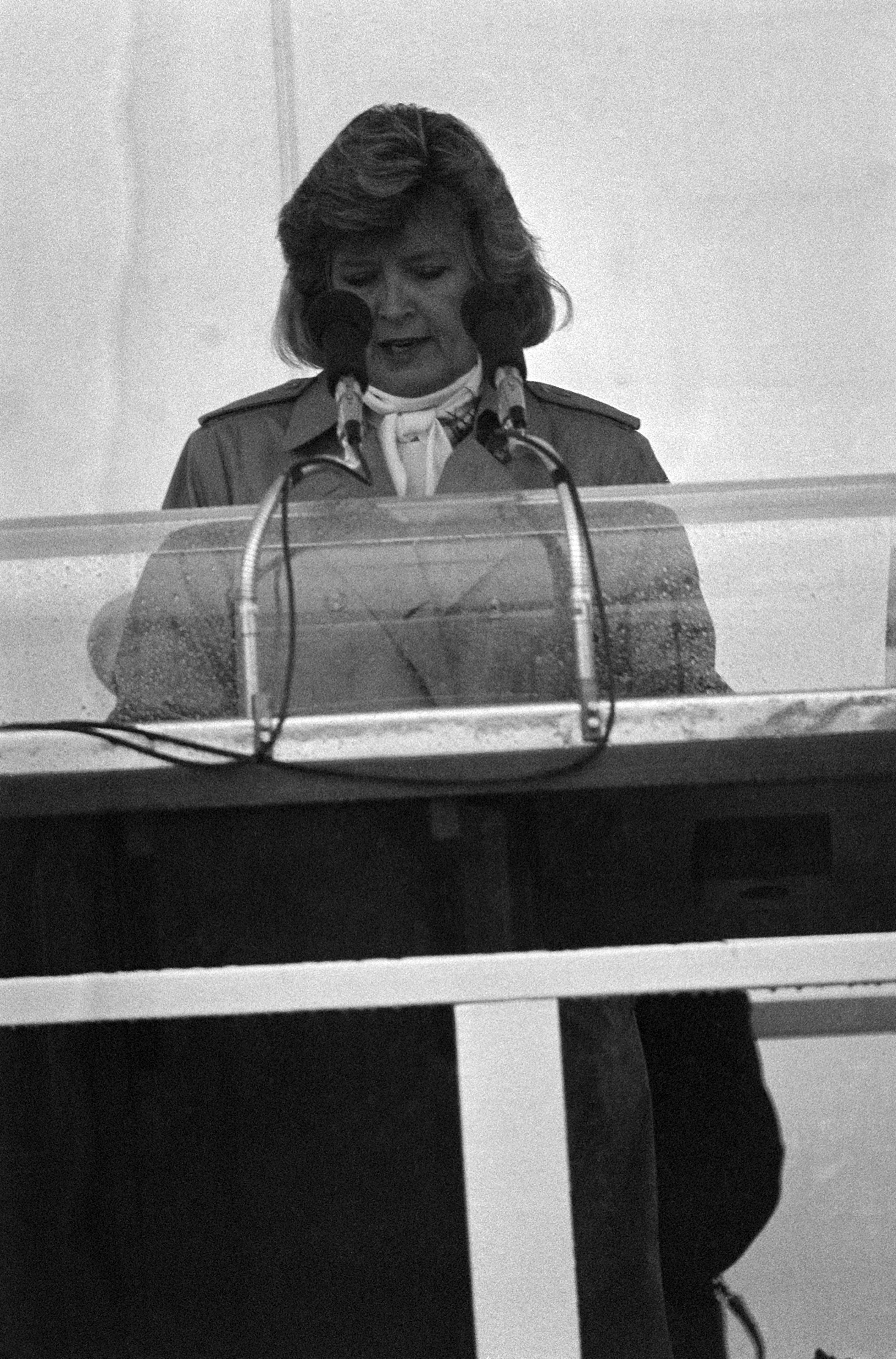

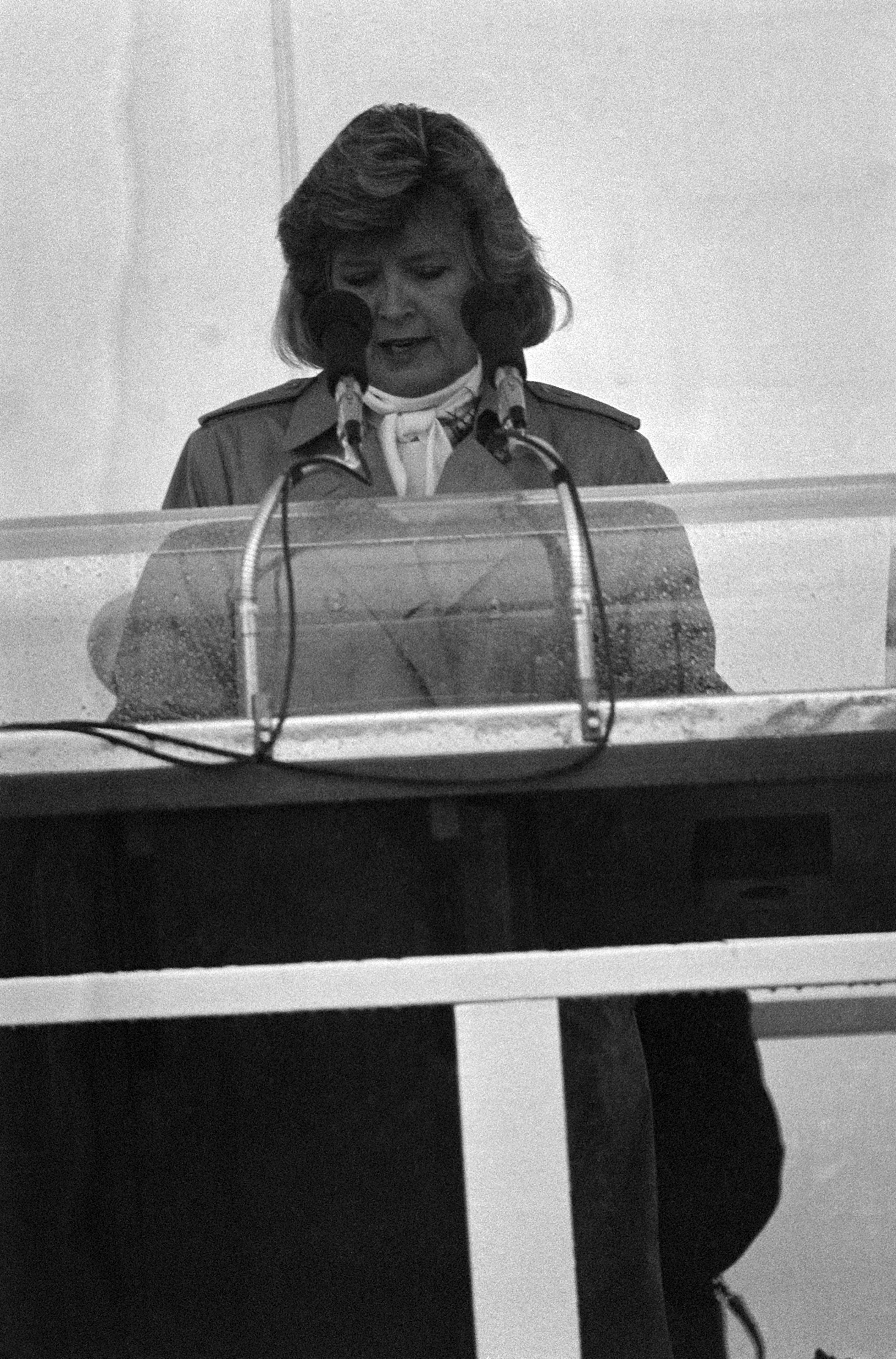

Brown and his first wife divorced in 1977. On March 17, 1979, he married former Miss America

Miss America is an annual competition that is open to women from the United States between the ages of 17 and 25. Originating in 1921 as a "bathing beauty revue", the contest is now judged on competitors' talent performances and interviews. As ...

and CBS sportscaster Phyllis George

Phyllis Ann George (June 25, 1949 – May 14, 2020) was an American businesswoman, actress, and sportscaster. In 1975, George was hired as a reporter and co-host of the CBS Sports pre-show ''The NFL Today'', becoming one of the first women ...

. The ceremony was performed by Norman Vincent Peale

Norman Vincent Peale (May 31, 1898 – December 24, 1993) was an American Protestant clergyman, and an author best known for popularizing the concept of positive thinking, especially through his best-selling book ''The Power of Positive ...

. Brown and George had two children, Lincoln Tyler George Brown and Pamela Ashley Brown.Tachau, p. 226.

Political career

Unlike his father, Brown showed only a passing interest in politics prior to 1979. In the 1960 election, he was named vice-chairman ofJohn F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

's presidential campaign in Kentucky."Law Hall of Fame Announced, Alumni Honored". U.S. Federal News Service. He was a member of the Young Leadership Council of the Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the governing body of the United States Democratic Party. The committee coordinates strategy to support Democratic Party candidates throughout the country for local, state, and national office, as well ...

, and was named honorary chairman of the National Democratic Party in 1972. Later that year, he considered running for the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

, but decided against it once former governor Louie B. Nunn

Louie Broady Nunn (March 8, 1924 – January 29, 2004) was an American politician who served as the 52nd governor of Kentucky. Elected in 1967, he was the only Republican to hold the office between the end of Simeon Willis's term in 1947 and t ...

entered the race."Entrepreneurs: John Brown's Buddy". ''Time''. From 1972 to 1974, he hosted the Democratic National Telethon. He founded the Governor's Economic Development Commission of Kentucky and served as chair from 1975 to 1977.

Gubernatorial election of 1979

On March 27, 1979, Brown interrupted his honeymoon with Phyllis George to announce his candidacy for governor of Kentucky.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 417. The announcement surprised most political observers because of his prior political apathy and because Brown had spent considerable time out of the state with his business ventures and lavish lifestyle. Funding his campaign with his own personal fortune, Brown launched a massive media campaign promoting his candidacy to help him overcome his late start in the race. He promised to run the state government like a business and to be a salesman for the state as governor. Other candidates in the Democratic field included sitting lieutenant governorThelma Stovall

Thelma Loyace Stovall (nee Hawkins; April 1, 1919 – February 4, 1994) was a pioneering American politician in the state of Kentucky. In 1949 she won election as state representative for Louisville, and served three consecutive terms. Over the n ...

, Terry McBrayer (the choice of sitting governor Julian Carroll), congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivale ...

Carroll Hubbard

Carroll Hubbard Jr. (July 7, 1937 – November 12, 2022) was an American politician and attorney from Kentucky. He began his political career in the Kentucky Senate, and was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1974. He serve ...

, state auditor George Adkins, and Louisville mayor Harvey Sloane. Initially the leading candidate, Stovall was hampered during the campaign by ill health.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 416. During the campaign, Brown was attacked by McBrayer for refusing to release his federal tax returns."McBreyer Hits Brown on Voting, Finances". ''Kentucky New Era

The ''Kentucky New Era'' is the major daily newspaper in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, in the United States.

History

The paper was founded in 1869 by John D. Morris and Asher Graham Caruth, as the ''Weekly Kentucky New Era.''Republican governor

Within a month of moving into the Governor's Mansion, Brown noticed significant deterioration in the wiring and ordered a full inspection.Clark, p. 191. The Department of Buildings and Construction's preliminary report stated "If this was a privately operated structure, this office would have no alternative other than to give the operator 30 to 60 days to rewire the structure."Clark, p. 192. The report went on to say that the mansion was a virtual firetrap. Upon receiving the report, Brown immediately moved his family out of the mansion and back to Cave Hill, his estate in Lexington. The Department of Buildings and Construction forbade use of the mansion for overnight purposes or group meetings until repairs could be made. Brown's Cave Hill estate was officially designated the temporary executive mansion, and the state agreed to furnish Brown's groceries, reimburse him for entertaining official guests, and pay for telephone calls made in his capacity as governor.Clark, p. 193. He was also given a travel allowance.

In March 1980, the

Within a month of moving into the Governor's Mansion, Brown noticed significant deterioration in the wiring and ordered a full inspection.Clark, p. 191. The Department of Buildings and Construction's preliminary report stated "If this was a privately operated structure, this office would have no alternative other than to give the operator 30 to 60 days to rewire the structure."Clark, p. 192. The report went on to say that the mansion was a virtual firetrap. Upon receiving the report, Brown immediately moved his family out of the mansion and back to Cave Hill, his estate in Lexington. The Department of Buildings and Construction forbade use of the mansion for overnight purposes or group meetings until repairs could be made. Brown's Cave Hill estate was officially designated the temporary executive mansion, and the state agreed to furnish Brown's groceries, reimburse him for entertaining official guests, and pay for telephone calls made in his capacity as governor.Clark, p. 193. He was also given a travel allowance.

In March 1980, the

Because he owed few favors to the state's established politicians, many of Brown's top appointees were businesspeople. Keeping a campaign promise to appoint a woman and an African-American to his cabinet, Brown named

Because he owed few favors to the state's established politicians, many of Brown's top appointees were businesspeople. Keeping a campaign promise to appoint a woman and an African-American to his cabinet, Brown named  Brown was less involved with the legislative process than previous governors. For example, he did not attempt to influence the choice of legislative leadership, while most previous governors had practically hand-selected the presiding officers in each house. During one of the two legislative sessions of his term, he went on vacation. Consequently, many of his legislative recommendations were not enacted. Among his failed proposals were a multi-county banking law, a flat rate income tax, professional negotiations for teachers, and a constitutional amendment to allow a governor to be elected to successive terms. In all, Brown was out of the state – leaving Lieutenant Governor

Brown was less involved with the legislative process than previous governors. For example, he did not attempt to influence the choice of legislative leadership, while most previous governors had practically hand-selected the presiding officers in each house. During one of the two legislative sessions of his term, he went on vacation. Consequently, many of his legislative recommendations were not enacted. Among his failed proposals were a multi-county banking law, a flat rate income tax, professional negotiations for teachers, and a constitutional amendment to allow a governor to be elected to successive terms. In all, Brown was out of the state – leaving Lieutenant Governor

In 1991, Brown formed a partnership with recording artist

In 1991, Brown formed a partnership with recording artist  In late 2006, Brown partnered with actress

In late 2006, Brown partnered with actress

Louie B. Nunn

Louie Broady Nunn (March 8, 1924 – January 29, 2004) was an American politician who served as the 52nd governor of Kentucky. Elected in 1967, he was the only Republican to hold the office between the end of Simeon Willis's term in 1947 and t ...

in the 1979 general election by a vote of 588,088 to 381,278.

Renovation of Governor's Mansion

Within a month of moving into the Governor's Mansion, Brown noticed significant deterioration in the wiring and ordered a full inspection.Clark, p. 191. The Department of Buildings and Construction's preliminary report stated "If this was a privately operated structure, this office would have no alternative other than to give the operator 30 to 60 days to rewire the structure."Clark, p. 192. The report went on to say that the mansion was a virtual firetrap. Upon receiving the report, Brown immediately moved his family out of the mansion and back to Cave Hill, his estate in Lexington. The Department of Buildings and Construction forbade use of the mansion for overnight purposes or group meetings until repairs could be made. Brown's Cave Hill estate was officially designated the temporary executive mansion, and the state agreed to furnish Brown's groceries, reimburse him for entertaining official guests, and pay for telephone calls made in his capacity as governor.Clark, p. 193. He was also given a travel allowance.

In March 1980, the

Within a month of moving into the Governor's Mansion, Brown noticed significant deterioration in the wiring and ordered a full inspection.Clark, p. 191. The Department of Buildings and Construction's preliminary report stated "If this was a privately operated structure, this office would have no alternative other than to give the operator 30 to 60 days to rewire the structure."Clark, p. 192. The report went on to say that the mansion was a virtual firetrap. Upon receiving the report, Brown immediately moved his family out of the mansion and back to Cave Hill, his estate in Lexington. The Department of Buildings and Construction forbade use of the mansion for overnight purposes or group meetings until repairs could be made. Brown's Cave Hill estate was officially designated the temporary executive mansion, and the state agreed to furnish Brown's groceries, reimburse him for entertaining official guests, and pay for telephone calls made in his capacity as governor.Clark, p. 193. He was also given a travel allowance.

In March 1980, the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of pres ...

created a committee to study whether it would be more feasible to construct a new governor's mansion or repair the old one.Clark, p. 194. Ultimately, they decided to renovate the existing mansion, and Brown's wife Phyllis was given liberal input into the decision making. The state had expected to cover the cost of the repairs using federal revenue sharing

Revenue sharing is the distribution of revenue, the total amount of income generated by the sale of goods and services among the stakeholders or contributors. It should not be confused with profit shares, in which scheme only the profit is share ...

funds, but President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 19 ...

ordered a halt to the funds in May 1980. First lady Phyllis Brown organized a group called "Save the Mansion" to raise private funds to offset the repair costs. Independently wealthy, Governor Brown donated his first year's salary to the project. He waived his salary for the remainder of his term. The renovation and repairs were completed in March 1983, and the Brown family returned to the mansion in April.Clark, p. 212.

Governorship

Because he owed few favors to the state's established politicians, many of Brown's top appointees were businesspeople. Keeping a campaign promise to appoint a woman and an African-American to his cabinet, Brown named

Because he owed few favors to the state's established politicians, many of Brown's top appointees were businesspeople. Keeping a campaign promise to appoint a woman and an African-American to his cabinet, Brown named William E. McAnulty Jr.

William Eugene McAnulty Jr. (October 9, 1947 – August 23, 2007) was an American attorney and judge in Louisville, Kentucky who became the first African American justice on the Kentucky Supreme Court. He served on every level court in Kentucky. ...

, and Jacqueline Swigart to his cabinet.Tachau, p. 223. McAnulty resigned his post as secretary of the state's Justice Cabinet within one month, saying the position would keep him from spending enough time with his family.Hewlett, "1st African-American Ky. High-Court Justice – William E. McAnulty 1947–2007". Brown re-appointed McAnulty to his former position as a judge with the Jefferson County District Court and replaced him with another African-American, George W. Wilson. He also appointed Viola Davis Brown as Executive Director of the Office of Public Health Nursing in 1980, she was the first African-American nurse to lead a state office of public health nursing in the United States. His most controversial appointment was Frank Metts, his secretary of transportation.Tachau, p. 224. Metts broke with political tradition in Kentucky, announcing that contracts would be awarded on the basis of competitive bids and performance rather than political patronage. Despite cutting personnel from the department, Metts doubled the miles of road that were resurfaced.

Difficult economic times marked Brown's term in office. During his tenure, the state's unemployment rate climbed from 5.6 percent to 11.7 percent. Brown stuck to his campaign promise not to raise taxes. When state income fell short of expectations, he reduced the state budget by 22 percent and cut the number of state employees from 37,241 to 30,783, mostly through transfer and attrition. At the same time, his merit pay policies increased salaries for the remaining employees by an average of 34 percent. He cut the executive office staff from ninety-seven to thirty and sold seven of the state's eight government airplanes.

Brown appointed a group of insurance experts to study the state's policies and put them out for bid, ultimately saving $2 million. He also required competitive bids from banks where state funds were deposited; the extra interest generated by this process generated an additional $50 million in revenue to the general fund.Tachau, p. 225. He opened communications and contacts with Japan, setting the stage for future economic relations between that country and Kentucky. Among his other accomplishments as governor were the implementation of competitive bidding for government contracts and passage of a weight-distance tax on trucks.

Brown was less involved with the legislative process than previous governors. For example, he did not attempt to influence the choice of legislative leadership, while most previous governors had practically hand-selected the presiding officers in each house. During one of the two legislative sessions of his term, he went on vacation. Consequently, many of his legislative recommendations were not enacted. Among his failed proposals were a multi-county banking law, a flat rate income tax, professional negotiations for teachers, and a constitutional amendment to allow a governor to be elected to successive terms. In all, Brown was out of the state – leaving Lieutenant Governor

Brown was less involved with the legislative process than previous governors. For example, he did not attempt to influence the choice of legislative leadership, while most previous governors had practically hand-selected the presiding officers in each house. During one of the two legislative sessions of his term, he went on vacation. Consequently, many of his legislative recommendations were not enacted. Among his failed proposals were a multi-county banking law, a flat rate income tax, professional negotiations for teachers, and a constitutional amendment to allow a governor to be elected to successive terms. In all, Brown was out of the state – leaving Lieutenant Governor Martha Layne Collins

Martha Layne Collins (née Hall; born December 7, 1936) is an American former businesswoman and politician from the Commonwealth of Kentucky; she was elected as the state's 56th governor from 1983 to 1987, the first woman to hold the office and ...

as acting governor – for more than five hundred days during his four-year term. As noted by Kentucky historian Lowell H. Harrison, Brown's hands-off approach allowed the legislature to gain power relative to the governor for the first time in Kentucky history, a trend which continued into the terms of his successors.

During his term, Brown served as co-chairman of the Appalachian Regional Commission

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) is a United States federal–state partnership that works with the people of Appalachia to create opportunities for self-sustaining economic development and improved quality of life. Congress established A ...

and chair of the Southern States' Energy Board. In May 1981, he was awarded an honorary

An honorary position is one given as an honor, with no duties attached, and without payment. Other uses include:

* Honorary Academy Award, by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, United States

* Honorary Aryan, a status in Nazi Germany ...

Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor ( ...

degree from the University of Kentucky, and in May 1982, he was the recipient of the Father of the Year award. In September 1983, the national Democratic Party named him Democrat of the Year, and he was later made the party's lifetime Honorary Treasurer.

In 1982, Brown was briefly hospitalized for hypertension, and near the end of his term, he underwent quadruple bypass surgery. While recovering from the surgery, Brown suffered a rare pulmonary disease, keeping him hospitalized for weeks, during part of which time he was coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle and does not initiate voluntary actions. Coma patients exhi ...

tose.Tachau, p. 227. He had no pulse for a period of time, and one of his lungs partially collapsed.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 418. Brown's office tried to conceal the seriousness of his condition, drawing fire from the press. Following his recovery, he gave up smoking

Smoking is a practice in which a substance is burned and the resulting smoke is typically breathed in to be tasted and absorbed into the bloodstream. Most commonly, the substance used is the dried leaves of the tobacco plant, which have bee ...

and took up jogging.

In ''Kentucky's Governors'', Brown biographer Mary K. Bonsteel Tachau said of his administration: "There were no scandals. Neither he nor any of his people were accused of corruption." Scandal did touch Brown personally, however, as well as some of his close associates. In 1981, he was investigated for withdrawing $1.3 million in personal cash from the All American Bank of Miami.Rugeley, "Friendship of Brown, Lambert Focus of Ads". The bank failed to report the transaction to the Internal Revenue Service as required by law. When the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

probed the matter in 1983, Brown claimed he withdrew the money to cover gambling debts he ran up during "one bad night gambling" in Las Vegas

Las Vegas (; Spanish language, Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the List of United States cities by population, 25th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the U.S. state, state of Neva ...

. Brown, who was not the focus of the FBI's investigation, later recanted that statement.

Some of Brown's associates were involved with a Lexington cocaine

Cocaine (from , from , ultimately from Quechua: ''kúka'') is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant mainly used recreationally for its euphoric effects. It is primarily obtained from the leaves of two Coca species native to South Am ...

and gun-smuggling ring called "The Company".Urch, "Scandals Beset Ky. Governors". James P. Lambert, an associate of Brown's since they attended the University of Kentucky together, was indicted on more than 60 drug charges."Former Governor Enters Kentucky Senate Race". ''The New York Times''. Phone records also showed calls from the governor's mansion to several individuals eventually convicted of drug charges in connection with the investigation.

Later political career

On March 15, 1984, Brown filed as a candidate for theU.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

seat held by Walter "Dee" Huddleston

Walter Darlington "Dee" Huddleston (April 15, 1926 – October 16, 2018) was an American politician. He was a Democrat from Kentucky who represented the state in the United States Senate from 1973 until 1985. Huddleston lost his 1984 Senate re- ...

just hours before the filing deadline. Six weeks later, on April 27, he withdrew his candidacy, citing the effects of his serious illness and surgery from the previous year.

In 1987

File:1987 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: The MS Herald of Free Enterprise capsizes after leaving the Port of Zeebrugge in Belgium, killing 193; Northwest Airlines Flight 255 crashes after takeoff from Detroit Metropolitan Airpor ...

, Brown again ran for governor, entering a crowded Democratic primary that included Lieutenant Governor Steve Beshear

Steven Lynn Beshear (born September 21, 1944) is an American attorney and politician who served as the 61st governor of Kentucky from 2007 to 2015. He served in the Kentucky House of Representatives from 1974 to 1980, was the state's 44th atto ...

, former governor Julian Carroll, Grady Stumbo, and political newcomer Wallace Wilkinson.Harrison in ''A New History of Kentucky'', p. 420. He entered the race late – filing his candidacy papers in late February before the primary election in late May.Schwartz, "A Kentucky Rebound". When Brown approached the state capitol

This is a list of state and territorial capitols in the United States, the building or complex of buildings from which the government of each U.S. state, the District of Columbia and the organized territories of the United States, exercise its ...

to file his papers, Beshear met him outside the filing office and challenged him to an impromptu debate, but Brown declined. As Brown quickly became the frontrunner, Beshear attacked his lavish lifestyle in a series of campaign ads, one of which was based on the popular television show ''Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous

''Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous'' is an American television series that aired in syndication from 1984 to 1995. The show featured the extravagant lifestyles of wealthy entertainers, athletes, socialites and magnates.

It was hosted by ...

''.Peterson, "In Kentucky, Life Style Is Now a Political Issue". Other ads by Beshear played up Brown's ties to James P. Lambert, while still others claimed that Brown would raise taxes.Dionne, "Brown Upset in Kentucky Primary". Brown refuted Beshear's claims in ads of his own, and the battle between Beshear and Brown opened an opportunity for Wilkinson – who distinguished himself from the field by advocating for a state lottery – to make a late surge. He defeated Brown, his closest competitor, by a margin of 58,000 votes.

Later life

Following his unsuccessful run for the governorship in 1987, Brown resumed his career in the restaurant industry. He started the Chicken Grill restaurant in Louisville and helped his wife, Phyllis, launchChicken By George

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domesticated junglefowl species, with attributes of wild species such as the grey and the Ceylon junglefowl that are originally from Southeastern Asia. Rooster or cock is a term for an ad ...

, a line of boneless, skinless chicken breast products designed for sale in supermarkets and preparation at home.Darby, "One success after another, by George". In 1988, Hormel

Hormel Foods Corporation is an American food processing company founded in 1891 in Austin, Minnesota, by George A. Hormel as George A. Hormel & Company. The company originally focused on the packaging and selling of ham, sausage and other pork, ...

made Chicken By George one of its subsidiaries. Brown expanded several other restaurants including Miami Subs, Texas Roadhouse

Texas Roadhouse is an American steakhouse chain that specializes in steaks in a Texan and Southwestern cuisine style. It is a subsidiary of Texas Roadhouse Inc, which has two other concepts (Bubba's 33 and Jaggers) and is headquartered in Louisv ...

, and Roadhouse Grill. None of these ventures matched the success he experienced early in his career.

In 1991, Brown formed a partnership with recording artist

In 1991, Brown formed a partnership with recording artist Kenny Rogers

Kenneth Ray Rogers (August 21, 1938 – March 20, 2020) was an American singer, songwriter, and actor. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2013. Rogers was particularly popular with country audiences but also charted m ...

, co-founding and serving as CEO of Kenny Rogers Roasters, an international chain of wood-roasted chicken restaurants. The founding of Kenny Rogers Roasters was part of a larger movement in the restaurant industry toward healthier, take-home offerings.Stouffer, "A High Stakes Game of Chicken". Roasters immediately found itself in competition with Boston Chicken (later known as Boston Market

Boston Market Corporation, known as Boston Chicken until 1995, is an American fast casual restaurant chain headquartered in Golden, Colorado. It is owned by the Rohan Group.

Boston Market has its greatest presence in the Northeastern and Midwest ...

) and several smaller roasted chicken chains. Kentucky Fried Chicken also introduced a roasted chicken line of products called Rotisserie Gold to compete with Roasters and Boston Chicken. In December 1992, Clucker's, a smaller player in the roasted chicken market, sued Kenny Rogers Roasters, claiming the chain had copied its recipes and menus.Seline, "Clucker's is First Casualty in Chicken Wars". The lawsuit continued until Roasters purchased a majority stake in Cluckers in August 1994. Brown then took Roasters public and grew it to a chain of more than 1,000 restaurants before selling his interest in the franchise to the Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

-based Berjaya Group

Berjaya Corporation Berhad (; formerly known as the Berjaya Group Berhad, Inter-Pacific Industrial Group Berhad and Raleigh Berhad) is a Malaysia-based corporation which controls a wide array of businesses, including consumer marketing, Property ...

in 1996.Hutt, "Kenny Rogers Wants to Take Name with Him from Bankrupt Roaster Chain".

Brown and his wife Phyllis separated in August 1995.Fleischman, p. 1B. Phyllis filed for divorce in Kentucky in 1996, but withdrew the petition amid settlement talks with her husband. After Brown reportedly cut off much of his wife's financial support, she filed a second divorce petition in 1997, this time in Broward County, Florida

Broward County ( , ) is a county in the southeastern part of Florida, located in the Miami metropolitan area. It is Florida's second-most populous county after Miami-Dade County and the 17th-most populous in the United States, with over 1.94 ...

where her husband was living at the time. After a brief legal fight over whether the proceedings should take place in Kentucky or Florida, the divorce became final in 1998."Former Ky. governor files for third divorce". ''Cincinnati Enquirer''. Later that year, he married former Mrs. Kentucky Jill Louise Roach, 27 years his junior, but they divorced in 2003 for reasons not released. When asked why they divorced he stated "I do have great love for Jill, but something which cannot be overlooked has come up in our marriage. I will always love her and her children, but it seems a divorce is our only option now."

In 1997, Brown agreed to be co-chairman of Governor Paul E. Patton

Paul Edward Patton (born May 26, 1937) is an American politician who served as the 59th governor of Kentucky from 1995 to 2003. Because of a 1992 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution, he was the first governor eligible to run for a second ter ...

's Council on Domestic Violence along with Patton's wife, Judi

Judi is a name with multiple origins. It is a short form of the Hebrew name Judith. It is also an Arabic name referring to a mountain mentioned in the Quran. It may refer to:

* Judi Andersen (born 1958), beauty pageant titleholder from Hawaii who ...

.Brammer, p. C1. Brown said he had always been interested in curbing domestic violence, but his interest became personal after he discovered that his sister, Betty "Boo" McCann, had been a victim. In 2003, Patton renamed Kentucky Route 9

Kentucky Route 9 (KY 9) is a state highway maintained by the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet in the U.S. Commonwealth of Kentucky. The highway extends from Grayson to Newport (a city in Kentucky across the Ohio River from Cincinnati ...

as the "John Y. Brown Jr. AA Highway".Leightty, K1. The "AA" designation comes from the fact that the highway originally connected the cities of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

and Ashland.

In late 2006, Brown partnered with actress

In late 2006, Brown partnered with actress Suzanne Somers

Suzanne Marie Somers (née Mahoney; born October 16, 1946) is an American actress, author, singer, businesswoman, and health spokesperson. She appeared in the television role of Chrissy Snow on '' Three's Company'' and as Carol Foster Lambert on ...

to open a do-it-yourself meal preparation store called Suzanne's Kitchen. The flagship store opened in Tates Creek Centre in Lexington, and a second store was opened in New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York (state), New York; on the ea ...

. Brown intended to build the business into a chain, but five months after the Lexington location opened, both stores closed. Brown said he wanted to "revamp the whole format to get something even more convenient" and promised to re-open both stores at some unspecified future date.Fortune, p. B1. Investor John Shannon Bouchillon sued Brown and Somers, claiming they had deceived him both before and after his investment of $400,000."US Lawsuit Against Actress Somers Dismissed". AP Worldstream. The case against Brown was dropped before it went to trial. In 2011, a Fayette County, Kentucky

Fayette County is located in the central part of the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 322,570, making it the second-most populous county in the commonwealth. Its territory, population and government are coexten ...

judge dismissed the suit against Somers for lack of evidence.

Brown refused to serve on the inaugural committee of his old political foe, Steve Beshear, when Beshear was elected governor in 2007. All of Kentucky's living former Democratic governors were invited to participate, and each accepted the invitation with the exception of Brown. Of his refusal, Brown stated "I don't respect him. I don't want to be part of it. I'm not really interested in being politically correct." Referring to the 1987 Democratic gubernatorial primary campaign, Brown continued, "He said things that were not true, like we had raised taxes. I just never respected him after that."Brammer, "Former Governor Declines Offer; Brown Doesn't Want to Be Part of Inauguration". However, when Beshear was reelected in 2011, Brown did serve as inauguration co-chair with the other former governors.Governor's Inauguration to be Frugal, Family-Friendly Celebration". U.S. Federal News Service.

In 2008, Brown was named to the University of Kentucky College of Law

The University of Kentucky J. David Rosenberg College of Law, also known as UK Rosenberg College of Law, is the law school of the University of Kentucky located in Lexington, Kentucky. Founded initially from a law program at Transylvania Universit ...

Alumni Association's Hall of Fame. In a press release, the association cited Brown's success at Kentucky Fried Chicken, his political career, and his help in establishing the university's Sanders–Brown Center on Aging as reasons for his induction. The center is named in honor of Harland Sanders and Brown's father. Brown divided his time between homes in Lexington, Kentucky, and Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Fort Lauderdale () is a coastal city located in the U.S. state of Florida, north of Miami along the Atlantic Ocean. It is the county seat of and largest city in Broward County with a population of 182,760 at the 2020 census, making it the tenth ...

.

Death

Brown died at a hospital in Lexington on November 22, 2022, at age 88. He had been dealing with health complications derived fromCOVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by a virus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The first known case was identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. The disease quickl ...

since the summer. His casket lay in state in the Kentucky Capitol's rotunda for two days starting on November 29, 2022. His funeral was held at the Kentucky Capitol on November 30. Brown would be buried in the Lexington Cemetery

Lexington Cemetery is a private, non-profit rural cemetery and arboretum located at 833 W. Main Street, Lexington, Kentucky.

The Lexington Cemetery was established in 1848 as a place of beauty and a public cemetery, in part to deal ...

.

References

Citations

General and cited references

* * * * * * * * * * *Denton, Sally. ''The Bluegrass Conspiracy: An Inside Story of Power, Greed, Drugs, and Murder.'' An Authors Guild Backprint.com Edition. Avon, 1990; Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse, 2001. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Brown, John Y. Jr. 1933 births 2022 deaths 20th-century American businesspeople 20th-century American politicians American Basketball Association executives American chief executives of food industry companies Boston Celtics owners Brown family of Kentucky Businesspeople from Lexington, Kentucky Deaths from the COVID-19 pandemic in Kentucky Democratic Party governors of Kentucky Kentucky Colonels executives Kentucky lawyers KFC people Los Angeles Clippers owners Military personnel from Lexington, Kentucky National Basketball Association executives National Basketball Association owners Politicians from Fort Lauderdale, Florida Politicians from Lexington, Kentucky University of Kentucky College of Law alumni United States Army reservists