Jews In Egypt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Jews in Egypt goes back to ancient times. Egyptian Jews or Jewish Egyptians refer to the

At this time, Jews from North Africa came to settle in Egypt after the

At this time, Jews from North Africa came to settle in Egypt after the

In the mid thirteenth century the

In the mid thirteenth century the

After the foundation of Israel in 1948, and the subsequent

After the foundation of Israel in 1948, and the subsequent

Under international law, Jews displaced from Arab countries were indeed bona fide refugees, subject to full UN protection, Stanley A. Urman, ''

Bassatine News: The only Jewish newsletter reporting directly from EgyptHistorical Society of Jews from Egypt

A Jewish Refugee Answers... Middle East Times, October 30, 2004.

The International Association of Jews from Egypt

Jews expelled from Egypt left behind a piece of their hearts

*

Egyptian Jews look back with anger, love

Guernica Magazine (guernica.com) on the last Jews of Cairo

Jews Indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa

* ttp://www.tabletmag.com/life-and-religion/58487/out-of-egypt/ Out of Egypt*Jewish Writer Reviews His Diary And a Wonderful Book Is Bor

Victor Teboul - About my novel on our Second Exodus

Zeva Oelbaum Photographs

at the

Digital Heritage Archive of Egyptian Jewry

on the Digital collections of

Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

community in Egypt who mainly consisted of Egyptian Arabic

Egyptian Arabic, locally known as Colloquial Egyptian, or simply as Masri, is the most widely spoken vernacular Arabic variety in Egypt. It is part of the Afro-Asiatic language family, and originated in the Nile Delta in Lower Egypt. The esti ...

-speaking Rabbanites

Rabbinic Judaism (), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, Rabbanite Judaism, or Talmudic Judaism, is rooted in the many forms of Judaism that coexisted and together formed Second Temple Judaism in the land of Israel, giving birth to classical rabb ...

and Karaites. Though Egypt had its own community of Egyptian Jews, after the Jewish expulsion from Spain

The Expulsion of Jews from Spain was the expulsion of practicing Jews following the Alhambra Decree in 1492, which was enacted to eliminate their influence on Spain's large ''converso'' population and to ensure its members did not revert to Judais ...

more Sephardi

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

and Karaite Jews began to migrate to Egypt, and then their numbers increased significantly with the growth of trading prospects after the opening of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

in 1869. As a result, Jews from many territories of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

as well as Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

started to settle in the main cities of Egypt, where they thrived (see Mutammasirun).

The Ashkenazi

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim) form a distinct subgroup of the Jewish diaspora, that Ethnogenesis, emerged in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium Common era, CE. They traditionally spe ...

community, mainly confined to Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

's Darb al-Barabira quarter, began to arrive in the aftermath of the waves of pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s that hit Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

in the latter part of the 19th century.

In the aftermath of the 1948 Palestine War

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. During the war, the British withdrew from Palestine, Zionist forces conquered territory and established the Stat ...

, the 1954 Lavon Affair, and the 1956 Suez War

The Suez Crisis, also known as the Second Arab–Israeli War, the Tripartite Aggression in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel, was a British–French–Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956. Israel invaded on 29 October, having done so w ...

, Jewish (estimated at between 75,000 and 80,000 in 1948), and European groups like the French and British emigrated; much of their property was also confiscated (see 20th century departures of foreign nationals from Egypt

The 20th century departures of foreign nationals from Egypt primarily concerned European and Levantine communities. These communities consisting of British, French, Greeks, Italians, Armenians, Maltese and Jews of Egyptian descent had been establ ...

).

, the president of Cairo's Jewish community said that there were 6 Jews in Cairo, all women over age 65, and 12 Jews in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

. , there were at least 5 known Jews in Cairo and as of 2017, 12 were still reported in Alexandria. In December 2022, it was reported that only 3 Egyptian Jews were living in Cairo.

Ancient Egypt

TheHebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' Israelites Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age. Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

(the ancient Semitic-speaking people from whom Jews originate) settled in . '' Israelites Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age. Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

, were enslaved, and were ultimately liberated by Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

, who led them out of Egypt to Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

. This founding myth

An origin myth is a type of myth that explains the beginnings of a natural or social aspect of the world. Creation myths are a type of origin myth narrating the formation of the universe. However, numerous cultures have stories that take place a ...

of the Israelites—known as the Exodus

The Exodus (Hebrew language, Hebrew: יציאת מצרים, ''Yəṣīʾat Mīṣrayīm'': ) is the Origin myth#Founding myth, founding myth of the Israelites whose narrative is spread over four of the five books of the Torah, Pentateuch (specif ...

—is considered to be inaccurate or ahistorical by a majority of scholars. At the same time, most scholars also hold that the Exodus probably has some sort of historical basis, and that a small group of Egyptian origins may have merged with the early Israelites, who were predominantly indigenous to Canaan and begin appearing in the historical record by around 1200 BCE. In the Elephantine papyri and ostraca

The Elephantine Papyri and Ostraca consist of thousands of documents from the Egyptian border fortresses of Elephantine and Aswan, which yielded hundreds of Papyrus, papyri and ostracon, ostraca in hieratic and Demotic (Egyptian), demotic Egyptia ...

(c. 500 – 300 BCE), caches of legal documents and letters written in Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

amply document the lives of a community of Jewish soldiers stationed there as part of a frontier garrison in Egypt for the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

.

Established at Elephantine

Elephantine ( ; ; ; ''Elephantíne''; , ) is an island on the Nile, forming part of the city of Aswan in Upper Egypt. The archaeological site, archaeological digs on the island became a World Heritage Site in 1979, along with other examples of ...

in about 650 BCE during Manasseh

Manasseh () is both a given name and a surname. Its variants include Manasses and Manasse.

Notable people with the name include:

Surname

* Ezekiel Saleh Manasseh (died 1944), Singaporean rice and opium merchant and hotelier

* Jacob Manasseh ( ...

's reign, these soldiers assisted the Twenty-sixth Dynasty pharaoh Psamtik I

Wahibre Psamtik I (Ancient Egyptian: ) was the first pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt, the Saite period, ruling from the city of Sais in the Nile delta between 664 and 610 BC. He was installed by Ashurbanipal of the Neo-Assyrian E ...

of the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

in his campaigns against the Twenty-fifth Dynasty pharaoh Tantamani

Tantamani ( Meroitic: 𐦛𐦴𐦛𐦲𐦡𐦲, , Neo-Assyrian: , ), also known as Tanutamun or Tanwetamani (d. 653 BC) was ruler of the Kingdom of Kush located in Northern Sudan, and the last pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt. ...

of Napata

Napata

(2020). (Old Egyptian ''Npt'', ''Npy''; Meroitic language, Meroitic ''Napa''; and Ναπάται) was a city of ...

. Their religious system shows strong traces of (2020). (Old Egyptian ''Npt'', ''Npy''; Meroitic language, Meroitic ''Napa''; and Ναπάται) was a city of ...

Babylonian religion

Babylonian religion is the religious practice of Babylonia. Babylonia's mythology was largely influenced by its Sumerian counterparts and was written on clay tablets inscribed with the cuneiform script derived from Sumerian cuneiform. The myths ...

, something which suggests to certain scholars that the community was of mixed Judahite

The Kingdom of Judah was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Centered in the highlands to the west of the Dead Sea, the kingdom's capital was Jerusalem. It was ruled by the Davidic line for four centuries. Jews are n ...

and Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

n origins, and they maintained their own temple, functioning alongside that of the local deity Khnum

Khnum, also romanised Khnemu (; , ), was one of the earliest-known Egyptian deities in Upper Egypt, originally associated with the Nile cataract. He held the responsibility of regulating the annual inundation of the river, emanating from the ca ...

. The documents cover the period 495 to 399 BCE.

According to the Hebrew Bible, a large number of Judeans took refuge in Egypt after the destruction of the Kingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah was an Israelites, Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Centered in the highlands to the west of the Dead Sea, the kingdom's capital was Jerusalem. It was ruled by the Davidic line for four centuries ...

in 586 BCE, and the subsequent assassination of the Jewish governor, Gedaliah

Gedaliah ( or ; ''Gəḏalyyā)'' was a person from the Bible who was a governor of Yehud province. He was also the son of Ahikam, who saved the prophet Jeremiah.

Names

Gedaliah ( or ; ''Gəḏalyyā'' or ''Gəḏalyyāhū''; also written G ...

. (, ) On hearing of the appointment, the Jewish population that fled to Moab

Moab () was an ancient Levant, Levantine kingdom whose territory is today located in southern Jordan. The land is mountainous and lies alongside much of the eastern shore of the Dead Sea. The existence of the Kingdom of Moab is attested to by ...

, Ammon

Ammon (; Ammonite language, Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; '; ) was an ancient Semitic languages, Semitic-speaking kingdom occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Wadi Mujib, Arnon and Jabbok, in present-d ...

, Edom

Edom (; Edomite language, Edomite: ; , lit.: "red"; Akkadian language, Akkadian: , ; Egyptian language, Ancient Egyptian: ) was an ancient kingdom that stretched across areas in the south of present-day Jordan and Israel. Edom and the Edomi ...

and other countries returned to Judah. () However, before long Gedaliah was assassinated, and the population that was left in the land and those that had returned ran away to Egypt for safety. (, ) The numbers that made their way to Egypt are subject to debate. In Egypt, they settled in Migdol

Migdol, or migdal, is a Hebrew word (מגדּלה מגדּל, מגדּל מגדּול) which means either a tower (from its size or height), an elevated stage (a rostrum or pulpit), or a raised bed (within a river). Physically, it can mean fo ...

, Tahpanhes

Tahpanhes or Tehaphnehes (; or ) known by the Ancient Greeks as the ( Pelusian) Daphnae () and Taphnas () in the Septuagint, now Tell Defenneh, was a city in ancient Egypt. It was located on Lake Manzala on the Tanitic branch of the Nile, abou ...

, Noph Noph or Moph was the Hebrew name for the ancient Egyptian city of Memphis, capital of Lower Egypt,

References

Hebrew Bible cities

Ancient Egypt

{{Egypt-geo-stub ...

, and Pathros

Pathros (; ; , ; Koine , ) refers to Upper Egypt, primarily the Thebaid where it extended from Elephantine fort to modern Asyut north of Thebes. Gardiner argues it extended to the north no further than Abydos. It is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible ...

. ()

Ptolemaic and Roman periods

Further waves of Jewish immigrants settled in Egypt during thePtolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; , ''Ptolemaioi''), also known as the Lagid dynasty (, ''Lagidai''; after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal house which ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period. ...

, especially around Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

. Thus, their history in this period centers almost completely on Alexandria, though daughter communities rose up in places like the present Kafr ed-Dawar, and Jews served in the administration as custodians of the river. As early as the third century BCE, there was a widespread diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of birth, place of origin. The word is used in reference to people who identify with a specific geographic location, but currently resi ...

of Jews in many Egyptian towns and cities. In Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

's history, it is claimed that, after Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; , ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'', "Ptolemy the Savior"; 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian, and successor of Alexander the Great who went on to found the Ptolemaic Kingdom centered on Egypt. Pto ...

took Judea

Judea or Judaea (; ; , ; ) is a mountainous region of the Levant. Traditionally dominated by the city of Jerusalem, it is now part of Palestine and Israel. The name's usage is historic, having been used in antiquity and still into the pres ...

, he led some 120,000 Jewish captives to Egypt from the areas of Judea, Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

, and Mount Gerizim

Mount Gerizim ( ; ; ; , or ) is one of two mountains in the immediate vicinity of the State of Palestine, Palestinian city of Nablus and the biblical city of Shechem. It forms the southern side of the valley in which Nablus is situated, the nor ...

. With them, many other Jews, attracted by the fertile soil and Ptolemy's liberality, emigrated there of their own accord. An inscription recording a Jewish dedication of a synagogue to Ptolemy and Berenice

Berenice (, ''Bereníkē'') is the Ancient Macedonian form of the Attic Greek name ''Pherenikē'', which means "bearer of victory" . Berenika, priestess of Demeter in Lete ca. 350 BC, is the oldest epigraphical evidence. The Latin variant Veron ...

was discovered in the 19th century near Alexandria.

Josephus also claims that, soon after, these 120,000 captives were freed from bondage by Philadelphus.

The history of the Alexandrian Jews

The history of the Jews in Alexandria dates back to the founding of the city by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE. Jews in Alexandria played a crucial role in the political, economic, cultural and religious life of Hellenistic and Roman Alexandria ...

dates from the foundation of the city by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

, 332 BCE, at which they were present. They were numerous from the very outset, forming a notable portion of the city's population under Alexander's successors. The Ptolemies assigned them a separate section, two of the five districts of the city, to enable them to keep their laws pure of indigenous cultic influences. The Alexandrian Jews enjoyed a greater degree of political independence than elsewhere. While the Jewish population elsewhere throughout the later Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

frequently formed private societies for religious purposes, or organized corporations of ethnic groups like the Egyptian and Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

n merchants in the large commercial centers, those of Alexandria constituted an independent political community, side by side with that of the other ethnic groups. Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

reported that the Jews of Alexandria had their own ethnarch

Ethnarch (pronounced , also ethnarches, ) is a term that refers generally to political leadership over a common ethnic group or homogeneous kingdom. The word is derived from the Greek language, Greek words (''Ethnic group, ethnos'', "tribe/nation ...

, who managed community affairs and legal matters similarly to a head of state.

The Hellenistic Jewish community of Alexandria translated the Old Testament into Greek. This translation is called the ''Septuagint

The Septuagint ( ), sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy (), and abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Biblical Hebrew. The full Greek ...

''. The translation of the Septuagint itself began in the 3rd century BCE and was completed by 132 BCE," ..die griechische Bibelübersetzung, die einem innerjüdischen Bedürfnis entsprang .. on denRabbinern zuerst gerühmt (..) Später jedoch, als manche ungenaue Übertragung des hebräischen Textes in der Septuaginta und Übersetzungsfehler die Grundlage für hellenistische Irrlehren abgaben, lehnte man die Septuaginta ab." Verband der Deutschen Juden (Hrsg.), neu hrsg. von Walter Homolka, Walter Jacob, Tovia Ben Chorin: Die Lehren des Judentums nach den Quellen; München, Knesebeck, 1999, Bd.3, S. 43ff initially in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, but in time elsewhere as well. It became the source for the Old Latin

Old Latin, also known as Early, Archaic or Priscan Latin (Classical ), was the Latin language in the period roughly before 75 BC, i.e. before the age of Classical Latin. A member of the Italic languages, it descends from a common Proto-Italic ...

, Slavonic, Syriac, Old Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian diaspora, Armenian communities around the ...

, Old Georgian, and Coptic versions of the Christian Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

.Ernst Würthwein, ''The Text of the Old Testament,'' trans. Errol F. Rhodes, Grand Rapids, Mich.: Wm. Eerdmans, 1995. The Jews of Alexandria celebrated the translation with an annual festival on the island of Pharos, where the Lighthouse of Alexandria

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, sometimes called the Pharos of Alexandria, was a lighthouse built by the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (280–247 BC). It has been estimated to have been at least ...

stood, and where the translation was said to have taken place.

During the period of Roman occupation, there is evidence that at Oxyrhynchus

Oxyrhynchus ( ; , ; ; ), also known by its modern name Al-Bahnasa (), is a city in Middle Egypt located about 160 km south-southwest of Cairo in Minya Governorate. It is also an important archaeological site. Since the late 19th century, t ...

(now Behneseh), on the west side of the Nile, there was a Jewish community of some importance. Many of the Jews there may have become Christians, though they retained their Biblical names (e.g., "David" and "Elizabeth," who appear in litigation concerning an inheritance). Another example was Jacob, son of Achilles (c. 300 CE), who worked as a beadle

A beadle, sometimes spelled bedel, is an official who may usher, keep order, make reports, and assist in religious functions; or a minor official who carries out various civil, educational or ceremonial duties on the manor.

The term has pre- ...

in a local Egyptian temple

Egyptian temples were built for the official worship of the gods and in commemoration of the pharaohs in ancient Egypt and regions under Egyptian control. Temples were seen as houses for the gods or kings to whom they were dedicated. Within them ...

. Philo of Alexandria describes an isolated Jewish monastic community known as the Therapeutae

The Therapeutae were a religious sect which existed in Alexandria and other parts of the ancient Greek world. The primary source concerning the Therapeutae is the ''De vita contemplativa'' ("The Contemplative Life"), traditionally ascribed to the ...

, who lived near Lake Mareotis

Lake Mariout ( ', , also spelled Maryut or Mariut), is a brackish lake in northern Egypt near the city of Alexandria. The lake area covered and had a navigable canal at the beginning of the 20th century, but at the beginning of the 21st century, ...

.

The Roman suppression of the Diaspora Revolt

The term "Diaspora Revolt" (115–117 CE; , or ; ), also known as the Trajanic Revolt and sometimes as the Second Jewish–Roman War, refers to a series of uprisings that occurred in Jewish diaspora communities across the eastern provinces of ...

(115–117) led to the near-total expulsion and annihilation of Jews from Egypt and nearby Cyrenaica. The Jewish revolt, which is said to have begun in Cyrene and spread to Egypt, was largely motivated by the Zealots

The Zealots were members of a Jewish political movements, Jewish political movement during the Second Temple period who sought to incite the people of Judaea (Roman province), Judaea to rebel against the Roman Empire and expel it from the Land ...

, aggravation after the failed Great Revolt and destruction of the Second Temple

The siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE was the decisive event of the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), a major rebellion against Roman rule in the province of Judaea. Led by Titus, Roman forces besieged the Jewish capital, which had become ...

, and anger at discriminatory laws. Jewish communities are thought to have rebelled due to messianic expectations, hoping for the ingathering of the exiles and the reconstruction of the Temple. A festival celebrating the victory over the Jews continued to be observed eighty years later in Oxyrhynchus. It was not until the third century that Jewish communities were able to re-establish themselves in Egypt, although they never regained their former level of influence.

Late Roman and Byzantine periods

By the late third century, there is substantial evidence of established Jewish communities in Egypt. A papyrus from Oxyrhynchus, dated to 291 CE, confirms the existence of an active synagogue and identifies one of its officials as having come from Palestine. This period likely saw an increase in immigration fromSyria Palaestina

Syria Palaestina ( ) was the renamed Roman province formerly known as Judaea, following the Roman suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt, in what then became known as the Palestine region between the early 2nd and late 4th centuries AD. The pr ...

, as indicated by the rising number of inscriptions, letters, legal documents, liturgical poetry, and magical texts in Hebrew and Aramaic from the fourth and fifth centuries.

The greatest blow Alexandrian Jews received was during the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

rule and the rise of a new state religion: Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

. There was an expulsion of a large amount of Jews from Alexandria (the so-called "Alexandria Expulsion") in 414 or 415 CE by Saint Cyril, following a number of controversies, including threats from Cyril and supposedly (according to Christian historian Socrates Scholasticus

Socrates of Constantinople ( 380 – after 439), also known as Socrates Scholasticus (), was a 5th-century Greek Christian church historian, a contemporary of Sozomen and Theodoret.

He is the author of a ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' ("Church Hi ...

) a Jewish-led massacre in response. Later violence took on a decidedly anti-Semitic context with calls for ethnic cleansing. Before that time, state/religious-sanctioned claims of a Jewish pariah were not common. In The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', sometimes shortened to ''Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', is a six-volume work by the English historian Edward Gibbon. The six volumes cover, from 98 to 1590, the peak of the Ro ...

, Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English essayist, historian, and politician. His most important work, ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789, is known for ...

describes the Alexandria pogrom:

Without any legal sentence, without any royal mandate, the patriarch (Saint Cyril), at the dawn of day, led a seditious multitude to the attack of the synagogues. Unarmed and unprepared, the Jews were incapable of resistance; their houses of prayer were leveled with the ground, and the episcopal warrior, after rewarding his troops with the plunder of their goods, expelled from the city the remnant of the unbelieving nation.Some authors estimate that around 100 thousand Jews were expelled from the city. The expulsion then continued in the nearby regions of Egypt and Palestine followed by a forced Christianization of the Jews.

Arab rule (641 to 1250)

TheMuslim conquest of Egypt

The Arab conquest of Egypt, led by the army of Amr ibn al-As, took place between 639 and 642 AD and was overseen by the Rashidun Caliphate. It ended the seven-century-long Roman Egypt, Roman period in Egypt that had begun in 30 BC and, more broa ...

at first found support from Jewish residents as well, disgruntled by the corrupt administration of the Patriarch of Alexandria

The Patriarch of Alexandria is the archbishop of Alexandria, Egypt. Historically, this office has included the designation "pope" (etymologically "Father", like "Abbot").

The Alexandrian episcopate was revered as one of the three major epi ...

Cyrus of Alexandria

Cyrus of Alexandria ( '' al-Muqawqis'', ; 6th century – 21 March 642) was a prominent figure in the 7th century. He served as a Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria and held the position of the second-last Byzantine prefect of Egypt. As P ...

, notorious for his Monotheletic proselytizing. In addition to the Jewish population settled there from ancient times, some are said to have come from the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

. The letter sent by Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

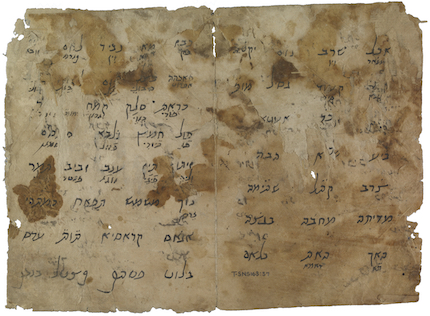

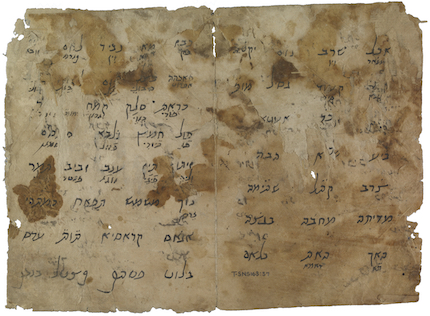

to the Jewish ''Banu Janba'' in 630 is said by Al-Baladhuri to have been seen in Egypt. A copy, written in Hebrew characters, has been found in the Cairo Geniza

The Cairo Geniza, alternatively spelled the Cairo Genizah, is a collection of some 400,000 Judaism, Jewish manuscript fragments and Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid administrative documents that were kept in the ''genizah'' or storeroom of the Ben Ezra ...

.

The Treaty of Alexandria, signed on in November 641, which sealed the Arab conquest of Egypt, provided for the rights of Jews (and Christians) to continue to practice their religion freely. 'Amr ibn al-'As

Amr ibn al-As ibn Wa'il al-Sahmi (664) was an Arab commander and companion of Muhammad who led the Muslim conquest of Egypt and served as its governor in 640–646 and 658–664. The son of a wealthy Qurayshite, Amr embraced Islam in and wa ...

, the Arab commander, claimed in a letter to Caliph Umar

Umar ibn al-Khattab (; ), also spelled Omar, was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () and is regarded as a senior companion and father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Mu ...

that there were 40,000 Jews in Alexandria at the time.

Of the fortunes of the Jewish population of Egypt under the Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a membe ...

and Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 CE), from whom the dynasty takes ...

s (641–868), little is known. Under the Tulunids

The Tulunid State, also known as the Tulunid Emirate or The State of Banu Tulun, and popularly referred to as the Tulunids () was a Mamluk dynasty of Turkic peoples, Turkic origin who was the first independent dynasty to rule Egypt in the Middle ...

(863–905), the Karaite community enjoyed robust growth.

Rule of the Fatimid Caliphs (969 to 1169)

At this time, Jews from North Africa came to settle in Egypt after the

At this time, Jews from North Africa came to settle in Egypt after the Fatimid conquest of Egypt

The Fatimid conquest of Egypt took place in 969 when the troops of the Fatimid Caliphate under the general Jawhar (general), Jawhar captured Medieval Egypt, Egypt, then ruled by the autonomous Ikhshidid dynasty in the name of the Abbasid Caliph ...

in 969. These Jewish immigrants made up a significant amount of the population from all the Jews living in Egypt. Due to the discovery of the Cairo Geniza documents at the end of the 19th century, a lot is known about Egyptian Jews. From private records, letters, public records, and documents, these sources held the information about the society of the Egyptian Jews.

The rule of the Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, i ...

was in general favorable for the Jewish communities, except the latter portion of al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah

Abu Ali al-Mansur (; 13 August 985 – 13 February 1021), better known by his regnal name al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (), was the sixth Fatimid caliph and 16th Ismaili imam (996–1021). Al-Hakim is an important figure in a number of Shia Ism ...

's reign. The foundation of Talmudic schools in Egypt is usually placed at this period. One of the Jewish citizens who rose to high position in that society was Ya'qub ibn Killis

Abu'l-Faraj Ya'qub ibn Yusuf ibn Killis (, ), (c. 930 in Baghdad – 991), commonly known simply by his patronymic surname as Ibn Killis, was a high-ranking official of the Ikhshidids who went on to serve as vizier under the Fatimids from 979 until ...

.

The caliph al-Hakim (996–1020) vigorously applied the Pact of Umar

The Pact of Umar (also known as the Covenant of Umar, Treaty of Umar or Laws of Umar; or or ) is a treaty between the Muslims and non-Muslims who were conquered by Umar during his conquest of the Levant (Syria and Lebanon) in the year 637 CE ...

, and compelled the Jewish residents to wear bells and to carry in public the wooden image of a calf. A street in the city, al-Jawdariyyah, was designated for Jewish residency. Al-Hakim, hearing allegations that some mocked him in verses, had the whole quarter burned down.

In the beginning of the 12th century, a Jewish man named Abu al-Munajja ibn Sha'yah was at the head of the Department of Agriculture. He is especially known as the constructor of a Nile sluice (1112), which was called after him "Baḥr Abi al-Munajja". He fell into disfavor because of the heavy expenses connected with the work, and was incarcerated in Alexandria, but was soon able to free himself. A document concerning a transaction of his with a banker has been preserved. Under the vizier

A vizier (; ; ) is a high-ranking political advisor or Minister (government), minister in the Near East. The Abbasids, Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was at first merely a help ...

Al-Malik al-Afḍal al-Malik (), literally "''the King''", is a name that may refer to:

*The title King of Kings

*One of the 99 names of God in Islam

*Imam Malik

*Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, Umayyad caliph

*Al-Malik al-Rahim, Buyid rulers

*Al-Malik al-Aziz, Buyid prince

...

(1137) there was a Jewish master of finances, whose name, however, is unknown. His enemies succeeded in procuring his downfall, and he lost all his property. He was succeeded by a brother of the Christian patriarch, who tried to drive the Jews out of the kingdom. Four leading Jews worked and conspired against the Christian, with what result is not known. There has been preserved a letter from this ex-minister to the Jews of Constantinople, begging for aid in a remarkably intricate poetical style. One of the physicians of the caliph Al-Ḥafiẓ (1131–49) was a Jew, Abu Manṣur ( Wüstenfeld, p. 306). Abu al-Faḍa'il ibn al-Nakid (died 1189) was a celebrated oculist.

As for government power in Egypt, the highest legal authority who was called chief scholar was held by Ephraim. Later on in the 11th century, this position was held by a father and son with the names of Shemarya b. Elhanan and Elhanan b. Shemarya. Soon the chief of the Palestinian Jews took over the position of chief scholar for the Rabbinates after the death of Elhanan. Around 1065, a Jewish leader was recognized as ''ráīs al-Yahūd'' meaning the head of the Jews in Egypt. Later for a sixty-year rule, three family members of court physicians took the position of ''ráīs al-Yahūd'' whose names were Judah b. Såadya, Mevorakh b. Såadya, and Moses b. Mevorakh. The position was eventually handed down from Moses Maimonides in the late 12th century to early 15th centuries and was given to his descendants.

As for the Jewish population, there were over 90 Jewish habitations known during the 11th and 12th centuries. These included cities, towns, and villages, contained over 4,000 Jewish citizens. Also for the Jewish population, a little more light is thrown upon the communities in Egypt through the reports of certain Jewish scholars and travelers who visited the country. Judah Halevi

Judah haLevi (also Yehuda Halevi or ha-Levi; ; ; c. 1075 – 1141) was a Sephardic Jewish poet, physician and philosopher. Halevi is considered one of the greatest Hebrew poets and is celebrated for his secular and religious poems, many of whic ...

was in Alexandria in 1141, and dedicated some beautiful verses to his fellow resident and friend Aaron Ben-Zion ibn Alamani and his five sons. At Damietta

Damietta ( ' ) is a harbor, port city and the capital of the Damietta Governorate in Egypt. It is located at the Damietta branch, an eastern distributary of the Nile Delta, from the Mediterranean Sea, and about north of Cairo. It was a Cath ...

Halevi met his friend, the Spaniard Abu Sa'id ibn Ḥalfon ha-Levi. About 1160 Benjamin of Tudela

Benjamin of Tudela (), also known as Benjamin ben Jonah, was a medieval Jewish traveler who visited Europe, Asia, and Africa in the twelfth century. His vivid descriptions of western Asia preceded those of Marco Polo by a hundred years. With his ...

was in Egypt; he gives a general account of the Jewish communities which he found there. At Cairo there were 2,000 Jews; at Alexandria 3,000, whose head was the French-born R. Phineas b. Meshullam; in the Faiyum

Faiyum ( ; , ) is a city in Middle Egypt. Located southwest of Cairo, in the Faiyum Oasis, it is the capital of the modern Faiyum Governorate. It is one of Egypt's oldest cities due to its strategic location.

Name and etymology

Originally f ...

there were 20 families; at Damietta 200; at Bilbeis

Bilbeis ( ; Bohairic ' is an ancient fortress city on the eastern edge of the southern Nile Delta in Egypt, the site of the ancient city and former bishopric of Phelbes and a Latin Catholic titular see.

The city is small in size but dens ...

, east of the Nile, 300 persons; and at Damira 700.

From Saladin and Maimonides (1169 to 1250)

Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

's war with the Crusaders (1169–93) does not seem to have affected the Jewish population with communal struggle. A Karaite doctor, Abu al-Bayyan al-Mudawwar (d. 1184), who had been physician to the last Fatimid, treated Saladin also. Abu al-Ma'ali, brother-in-law of Maimonides, was likewise in his service. In 1166 Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

went to Egypt and settled in Fostat

Fustat (), also Fostat, was the first capital of Egypt under Muslim rule, though it has been integrated into Cairo. It was built adjacent to what is now known as Old Cairo by the Rashidun Muslim general 'Amr ibn al-'As immediately after the Musl ...

, where he gained much renown as a physician, practising in the family of Saladin and in that of his vizier al-Qadi al-Fadil

Muhyi al-Din (or Mujir al-Din) Abu Ali Abd al-Rahim ibn Ali ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Lakhmi al-Baysani al-Asqalani, better known by the honorific name al-Qadi al-Fadil (; 3 April 1135 – 26 January 1200) was an official who served the last F ...

, and Saladin's successors. The title ''Ra'is al-Umma'' or ''al-Millah'' (Head of the Nation or of the Faith), was bestowed upon him. In Fostat he wrote his ''Mishneh Torah

The ''Mishneh Torah'' (), also known as ''Sefer Yad ha-Hazaka'' (), is a code of Rabbinic Jewish religious law (''halakha'') authored by Maimonides (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon/Rambam). The ''Mishneh Torah'' was compiled between 1170 and 1180 CE ( ...

'' (1180) and ''The Guide for the Perplexed

''The Guide for the Perplexed'' (; ; ) is a work of Jewish theology by Maimonides. It seeks to reconcile Aristotelianism with Rabbinical Jewish theology by finding rational explanations for many events in the text.

It was written in Judeo-Arabic ...

'', both of which evoked opposition from Jewish scholars. From this place he sent many letters and responsa

''Responsa'' (plural of Latin , 'answer') comprise a body of written decisions and rulings given by legal scholars in response to questions addressed to them. In the modern era, the term is used to describe decisions and rulings made by scholars i ...

; and in 1173 he forwarded a request to the North African communities for help to secure the release of a number of captives. The original of the last document has been preserved. He caused the Karaites to be removed from the court.

Mameluks (1250 to 1517)

In the mid thirteenth century the

In the mid thirteenth century the Ayyubid empire

The Ayyubid dynasty (), also known as the Ayyubid Sultanate, was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish ori ...

was plagued with famine, disease, and conflict; a great period of upheaval would see the Golden Islamic Period come to a violent end. Foreign powers began to encircle the Islamic World as the French endeavored on the 7th crusade in 1248 and the Mongol campaigns in the east rapidly making its way into the heartland of Islam. These internal and external pressure weakened the Ayyubid empire.

In 1250 following the death of Sultan As-Salih Ayyub

Al-Malik as-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub (5 November 1205 – 22 November 1249), nickname: Abu al-Futuh (), also known as al-Malik al-Salih, was the Ayyubid ruler of Egypt from 1240 to 1249.

Early life

As-Salih was born in 1205, the son of Al-Kamil ...

, slave soldiers, Mamluk

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-so ...

s, rose up and slaughtered all the Ayyubid heirs and the Mamluk leader Aybak

Izz al-Din AybakThe name Aybeg or Aibak or Aybak is a combination of two Turkic words, "Ay" = Moon and "Beg" or variant "Bak" = Emir in Arabic. -(Al-Maqrizi, Note p.463/vol.1 ) () (''epithet:'' al-Malik al-Mu'izz Izz al-Din Aybak al-Jawshangir ...

became the new sultan. The Mamluks were quick to consolidate power using a strong spirit of defense growing among Muslim faithfuls to rally victoriously against the Mongols in the Battle of Ain Jalut

The Battle of Ain Jalut (), also spelled Ayn Jalut, was fought between the Bahri Mamluks of Egypt and the Ilkhanate on 3 September 1260 (25 Ramadan 658 AH) near the spring of Ain Jalut in southeastern Galilee in the Jezreel Valley. It marks ...

in 1260 and consolidating the remnants of the Ayyubid Syria in 1299.

In this period of aggressive posturing the ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' ( ; also spelled ''ulema''; ; singular ; feminine singular , plural ) are scholars of Islamic doctrine and law. They are considered the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam.

"Ulama ...

were quick to denounce foreign influences to safeguard the purity of Islam. This led to unfortunate situations for Mamluk Jews. In 1300 Sultan Al-Nasir Qalawan ordered all Jews under his rule to wear yellow headgear to isolate the Egyptian Jewish community. This law would be enforced for centuries and later amended in 1354 to force all Jews to wear a sign in addition to yellow headwear. On multiple occasions the ulema persuaded the government to close or convert synagogues. Even major places of pilgrimage for Egyptian Jews such as the Dammah Synagogue were forced to close in 1301. Jews subsequently were excluded from bath houses and were prohibited to work in the national treasury. This repression of the Jewish community would continue for centuries.

In all the religious fervor of the period the Mamluks began to adopt Sufism

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

in an attempt to assuage dissatisfaction with traditional Sunni Islam facilitated solely by the Sultan. At the same time the Mamluk government was unwilling to relinquish control of religion to a clerical class. They endeavored on a massive project of inviting and subsidizing Sufi clerics in an attempt to promote a new state religion. All throughout the country new government-backed Sufi brotherhoods and saint cults grew almost overnight and was able to quell the disapproval of the population. The Mamluk Sultanate would become a safe haven for Sufi mystics all throughout the Islamic world. Across the empire state-sponsored Sufi ceremonies were a clear sign of the full-fledged shift that took hold.

Jews who for the most part were kept segregated from Arab communities first came into contact with Sufism in these state sponsored ceremonies, as they were obliged to attend out of a show of loyalty to the sultan. It is in these ceremonies where many Egyptian Jews first came into contact with Sufism and it would eventually spark a massive movement amongst the Mamluk Jews.

Most Egyptian Jews of the time were members of the Karaite Judaism

Karaite Judaism or Karaism is a Rabbinic Judaism, non-Rabbinical Jewish religious movements, Jewish sect characterized by the recognition of the written Tanakh alone as its supreme religious text, authority in ''halakha'' (religious law) and t ...

. This was an anti-rabbinical movement that rejected the teachings of the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

. It is believed by historians such as Paul Fenton that the Karaites settled in Egypt as early as the seventh century, and Egypt would remain a bastion for Karaites all the way through the 19th century. As time passed in contact with these relatively new Sufi ideas many Karaites began to push towards reform. Admiration for the structure of khanqah

A Sufi lodge is a building designed specifically for gatherings of a Sufi brotherhood or ''tariqa'' and is a place for spiritual practice and religious education. They include structures also known as ''khānaqāh'', ''zāwiya'', ''ribāṭ'' ...

s (Sufi schools), and its doctrinal focus on mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute (philosophy), Absolute, but may refer to any kind of Religious ecstasy, ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or Spirituality, spiritual meani ...

began to make many Egyptian Jews long to adopt something similar.

Abraham Maimonides

Abraham Maimonides (; also known as Rabbeinu Avraham ben ha-Rambam, and Avraham Maimuni, June 13, 1186 – December 7, 1237) was the son of Maimonides and succeeded his father as nagid of the Egyptian Jewish community.

Biography

Avraham w ...

(1204–1237), who was considered to be the most prominent leader and government representative of all Mamluk Jews, advocated reorganizing Jewish schools to be more like Sufi Hanaqas. His heir Obadyah Maimonides(1228–1265) wrote the ''Treatise of the Pool'', which is a mystical manual written in Arabic and filled with Sufi technical terms. In it he laid out how one may obtain union with the unintelligible world, showing his full adherence and advocacy of mysticism. He also began to reform practices advocating for celibacy and Halwa, solitary meditation, to better tune oneself to the spiritual plane. These were imitations of long held Sufi practices. In fact, he would often portrayed Jewish patriarchs such as Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

and Isaac

Isaac ( ; ; ; ; ; ) is one of the three patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith. Isaac first appears in the Torah, in wh ...

as hermits who relied on isolated meditation to remain in touch with God. The Maimonides dynasty would essentially spark a new movement, Pietism, amongst Egyptian Jews.

Pietism gained a huge following, mainly amongst the Jewish elite, and it would continue to gain momentum until the end of the Maimonides dynasty in the 15th century. Additionally, forced conversions in Yemen, Eighth Crusade

The Eighth Crusade was the second Crusade launched by Louis IX of France, this one against the Hafsid dynasty in Tunisia in 1270. It is also known as the Crusade of Louis IX Against Tunis or the Second Crusade of Louis. The Crusade did not see an ...

and Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).

The Almohad ...

massacres in North Africa, and the collapse of al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

forced large number of Jews to resettle to Egypt, many of whom would join the Pietist movement enthusiastically. This enthusiasm may have been largely practical, as the adoption of Sufi ideas did much to ingratiate the Mamluk Jewish community with their Muslim overlords. This may have appealed to many of these refugees, as some historians state that the Maimonides dynasty itself originated from Al Andalus and resettled in Egypt.

Pietism would in some ways become indistinguishable from Sufism. Pietists would clean their hands and feet before praying in the temple. They would face Jerusalem as they prayed. They frequently practiced daytime fasting and group meditation or muraqaba.

There was vehement opposition to the revisionism of Pietism just as there was with Hasidism. Opposition was so strong there are records of Jews reporting fellow Jews to Muslim authorities on the grounds that they were practicing Islamic heresy. David Maimonides, brother of Obadyah and his heir, was eventually exiled to Palestine at the behest of other leaders in the Jewish community. Eventually Pietism fell out of favor in Egypt, as its leaders were exiled and Jewish immigration slowed.

Per Fenton, the influence of Sufism is still present in many Kabbalistic rituals, and some of the manuscripts authored under the Maimonides dynasty are still read and revered in Kabbalist circles.

Ottoman rule (1517 to 1914)

On January 22, 1517, the Ottoman sultan,Selim I

Selim I (; ; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute (), was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite lasting only eight years, his reign is ...

, defeated Tuman Bey, the last of the Mamelukes. He made radical changes in the governance of the Jewish community, abolishing the office of nagid, making each community independent, and placing David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra

David ben Solomon ibn (Abi) Zimra () (1479–1573) also called the Radbaz () after the initials of his name, Rabbi David ben Zimra, was an early acharon of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries who was a leading ''posek'', ''rosh yeshiva'', chie ...

at the head of that of Cairo. He also appointed Abraham de Castro

Abraham de Castro (Hebrew: אברהם קסטרו; d. 1560) was an Ottoman Jewish financialist who served as the head of the mint for Ottoman Sultan, Selim I and played an active role in the Cairo Purim.

Biography

Possibly born in Spain, into ...

to be master of the mint. It was during the reign of Selim's successor, Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I (; , ; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the Western world and as Suleiman the Lawgiver () in his own realm, was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman sultan between 1520 a ...

, that Hain Ahmed Pasha

Hain Ahmed Pasha ( Ahmed Pasha 'the Traitor'; died 1524), was an Ottoman governor (beylerbey) and a statesman, who became the Ottoman governor of Egypt Eyalet in 1523.

Early life

Ahmed Pasha was of Georgian origin. He was educated in the Ende ...

, Viceroy of Egypt

The Ottoman Empire's governors of Egypt from 1517 to 1805 were at various times known by different but synonymous titles, among them ''beylerbey'', viceroy, governor, governor-general, or, more generally, ''wāli''. Furthermore, the Ottoman sult ...

, revenged himself upon the Jews because de Castro had revealed in 1524 to the sultan of his designs for independence. The Cairo Purim of 28 Adar

Adar (Hebrew: , ; from Akkadian ''adaru'') is the sixth month of the civil year and the twelfth month of the religious year on the Hebrew calendar, roughly corresponding to the month of March in the Gregorian calendar. It is a month of 29 days. ...

is still celebrated in commemoration of their escape.

Towards the end of the 16th century, Talmudic studies in Egypt were greatly fostered by Bezalel Ashkenazi

Bezalel ben Abraham Ashkenazi () ( 1520 – 1592) was a rabbi and talmudist who lived in Ottoman Israel during the 16th century. He is best known as the author of the ''Shitah Mekubetzet'', a commentary on the Talmud. Among his disciples were ...

, author of the ''Shiṭṭah Mequbbeṣet''. Among his pupils were Isaac Luria

Isaac ben Solomon Ashkenazi Luria (; #FINE_2003, Fine 2003, p24/ref>July 25, 1572), commonly known in Jewish religious circles as Ha'ari, Ha'ari Hakadosh or Arizal, was a leading rabbi and Jewish mysticism, Jewish mystic in the community of Saf ...

, who as a young man had gone to Egypt to visit a rich uncle, the tax-farmer Mordecai Francis (Azulai, "Shem ha-Gedolim," No. 332); and Abraham Monson. Ishmael Kohen Tanuji finished his ''Sefer ha-Zikkaron'' in Egypt in 1543. Joseph ben Moses di Trani was in Egypt for a time (Frumkin, l.c. p. 69), as well as Ḥayyim Vital Aaron ibn Ḥayyim, the Biblical and Talmudical commentator (1609; Frumkin, l.c. pp. 71, 72). Of Isaac Luria's pupils, a Joseph Ṭabul is mentioned, whose son Jacob, a prominent man, was put to death by the authorities.

The 1648–1657 Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

forced local Jews to flee to Ottoman lands, including Egypt. The responsa

''Responsa'' (plural of Latin , 'answer') comprise a body of written decisions and rulings given by legal scholars in response to questions addressed to them. In the modern era, the term is used to describe decisions and rulings made by scholars i ...

of Hakham Mordecai ha-Levi document how several Ashkenazi

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim) form a distinct subgroup of the Jewish diaspora, that Ethnogenesis, emerged in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium Common era, CE. They traditionally spe ...

women, who arrived in Egypt and became ''agunot'' due to the chaos, faced challenges with the validity of their divorce documents. The rabbi accepted the documents, enabling the women to remarry.

According to Manasseh b. Israel from 1656, "The viceroy of Egypt has always at his side a Jew with the title ''zaraf bashi'', or 'treasurer,' who gathers the taxes of the land. At present Abraham Alkula holds the position". He was succeeded by Raphael Joseph Çelebi, nagid

Nagid ( ) is a Hebrew term meaning a prince or leader. This title was often applied to the religious leader in Sephardic communities of the Middle Ages. In Egypt, the Jewish ''Nagid'' was appointed over all the Jews living under the dominion of the ...

of Egypt and rich friend and protector of Sabbatai Zevi

Sabbatai Zevi (, August 1, 1626 – ) was an Ottoman Jewish mystic and ordained rabbi from Smyrna (now İzmir, Turkey). His family were Romaniote Jews from Patras. His two names, ''Shabbethay'' and ''Ṣebi'', mean Saturn and mountain gazelle, ...

. Sabbatai Zevi was twice in Cairo, the second time in 1660. It was there that he married Sarah Ashkenazi, who had been brought from Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 152,916 residents as of 2025. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn ...

. The Sabbatian movement naturally created a great stir in Egypt. It was in Cairo that Abraham Miguel Cardoso

Abraham Miguel Cardozo (also Cardoso; c. 1626–1706) was a Sabbatean prophet and physician born in Rio Seco, Spain.

Biography

A descendant of ''Marranos'' from around the city of Celorico da Beira in Portugal, he studied medicine at the Univer ...

, the Sabbatian prophet and physician, settled in 1703, becoming physician to Kara Mehmed Pasha

Kara or KARA may refer to:

Geography Localities

* Kara, Chad, a sub-prefecture

* Kára, Hungary, a village

* Kara, Uttar Pradesh, India, a township

* Kara, Iran, a village in Lorestan Province

* Kara, Republic of Dagestan, a rural locality in ...

. In 1641 Samuel ben David, a Karaite, visited Egypt. The account of his journey supplies special information in regard to his fellow sectarians. He describes three synagogues of the Rabbinites at Alexandria and two at Rosetta

Rosetta ( ) or Rashid (, ; ) is a port city of the Nile Delta, east of Alexandria, in Egypt's Beheira governorate. The Rosetta Stone was discovered there in 1799.

Founded around the 9th century on the site of the ancient town of Bolbitine, R ...

. A second Karaite, Moses ben Elijah ha-Levi, has left a similar account of the year 1654, but it contains only a few points of special interest to the Karaites.

Joseph ben Isaac Sambari

Joseph ben Isaac Sambari (Hebrew: יוסף בן יצחק סמברי; – 1703) also known as Qātāya (Arabic: قاطية) was a 17th century Egyptian Jewish historian and chronicler whose works provide important details about the affairs and co ...

mentions a severe trial which came upon the Jews, due to a certain ''qāḍī al-ʿasākir'' ("generalissimo," not a proper name) sent from Constantinople to Egypt, who robbed and oppressed them, and whose death was in a certain measure occasioned by the graveyard invocation of one Moses of Damwah. This may have occurred in the 17th century. David Conforte

David Conforte (c. 1618 – c. 1685) () was a Hebrew literary historian born in Salonica, author of the literary chronicle known by the title ''Ḳore ha-Dorot.''

Biography

Conforte came of a family of scholars. His early instructors were rabbi ...

was dayyan in Egypt in 1671.

In consequence of the Damascus affair, Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 – 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, Philanthropy, philanthropist and Sheriffs of the City of London, Sheriff of London. Born to an History ...

, Adolphe Crémieux

Isaac-Jacob Adolphe Crémieux (; 30 April 1796 – 10 February 1880) was a French lawyer and politician who served as Minister of Justice under the Second Republic (1848) and Government of National Defense (1870–1871). Raised Jewish, he ...

, and Salomon Munk

Salomon Munk (14 May 1803 – 5 February 1867) was a German-born Jewish-French Orientalist.

Biography

Munk was born in Gross Glogau in the Kingdom of Prussia. He received his first instruction in Hebrew from his father, an official of the J ...

visited Egypt in 1840, and the last two did much to raise the intellectual status of their Egyptian brethren by the founding, in connection with Rabbi Moses Joseph Algazi, of schools in Cairo. According to the official census published in 1898 (i., xviii.), there were in Egypt 25,200 Jews in a total population of 9,734,405.

One famous Egyptian Jew of this period was Yaqub Sanu

Yaqub Sanu (, , anglicized as James Sanua), also known by his pen name "Abu Naddara" ( ''Abū Naẓẓārah'' "the man with glasses"; January 9, 1839 – 1912), was an Egyptian scriptwriter writing in Egyptian Arabic. He was a pioneer of political ...

, who became a patriotic Egyptian nationalist advocating the removal of the British. He edited the nationalist publication Abu Naddara 'Azra from exile. This was one of the first magazines written in Egyptian Arabic

Egyptian Arabic, locally known as Colloquial Egyptian, or simply as Masri, is the most widely spoken vernacular Arabic variety in Egypt. It is part of the Afro-Asiatic language family, and originated in the Nile Delta in Lower Egypt. The esti ...

, and mostly consisted of satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of exposin ...

, poking fun at the British as well as the ruling Muhammad Ali dynasty

The Muhammad Ali dynasty or the Alawiyya dynasty was the ruling dynasty of Egypt and Sudan from the 19th to the mid-20th century. It is named after its progenitor, the Albanians, Albanian Muhammad Ali of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, regarded as the fou ...

, seen as puppets of the British.

At the turn of the 20th century, a Jewish observer noted with 'true satisfaction that a great spirit of tolerance sustains the majority of our fellow Jews in Egypt, and it would be difficult to find a more liberal population or one more respectful of all religious beliefs.’

Modern times (since 1919)

Since 1919

During British rule, and underKing Fuad I

Fuad I ( ''Fu’ād al-Awwal''; 26 March 1868 – 28 April 1936) was the Sultan and later King of Egypt and the Sudan. The ninth ruler of Egypt and Sudan from the Muhammad Ali dynasty, he became Sultan in 1917, succeeding his elder brother Huss ...

, Egypt was friendly towards its Jewish population, although between 86% and 94% of Jews in Egypt, mostly European immigrants, did not possess Egyptian nationality. Jews played important roles in the economy, and their population climbed to nearly 80,000 as Jewish refugees settled there in response to increasing persecution in Europe. Many Jewish families, such as the Qatawi family

The Qatawi family (also spelled Qatawwi, Catawi, or Cattaui) (Arabic:عائلة قطاوي) is an Egyptian Sephardic Jews, Sephardic Jewish family. A number of its members engaged in political and economic activity in Egypt in the late nineteent ...

, had extensive economic relations with non-Jews.

A sharp distinction had long existed between the respective Karaite and Rabbanite communities, among whom traditionally intermarriage was forbidden. They dwelt in Cairo in two contiguous areas, the former in the ''harat al-yahud al-qara’in'', and the latter in the adjacent ''harat al-yahud'' quarter. Notwithstanding the division, they often worked together and the younger educated generation pressed for improving relations between the two.

Individual Jews played an important role in Egyptian nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

. René Qatawi, leader of the Cairo Sephardi community, endorsed the creation in 1935 of the Association of Egyptian Jewish Youth, with its slogan: 'Egypt is our homeland, Arabic is our language.' Qattawi strongly opposed political Zionism

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

and wrote a note on 'The Jewish Question' to the World Jewish Congress

The World Jewish Congress (WJC) is an international federation of Jewish communities and organizations, founded in Geneva, Switzerland, in August 1936. According to its mission statement, the World Jewish Congress's main purpose is to act as ...

in 1943 in which he argued that Palestine would be unable to absorb Europe's Jewish refugees.

Nevertheless, various wings of the Zionist movement had representatives in Egypt. Karaite Jewish scholar (1866–1956) was both an Egyptian nationalist and a passionate Zionist. His poem, 'My Homeland Egypt, Place of my Birth', expresses loyalty to Egypt, while his book, ''al-Qudsiyyat'' (Jerusalemica, 1923), defends the right of the Jews to a State. ''al-Qudsiyyat'' is perhaps the most eloquent defense of Zionism in the Arabic language. Mourad Farag was also one of the coauthors of Egypt's first Constitution in 1923.

In 1943 Henri Curiel

Henri Curiel (13 September 1914 – 4 May 1978) was a left-wing political activist in Egypt and France. Born in Egypt, Curiel led the communist Democratic Movement for National Liberation until he was expelled from the country in 1950.

Settling ...

founded 'The Egyptian Movement for National Liberation' in 1943, an organization that was to form the core of the Egyptian Communist party. Curiel was later to play an important role in establishing early informal contacts between the PLO and Israel.

In 1934, Saad Malki founded newspaper ''Ash-Shams

Ash-Shams (, "The Sun") is the 91st surah of the Qur'an, with 15 ayat or verses. It opens with a series of solemn oaths sworn on various Islamic astronomy, astronomical phenomena, the first of which, "by the sun", gives the sura its name, then ...

'' (, 'The Sun'). The weekly was closed down by the Egyptian government in May 1948.

In 1937, the Egyptian government annulled the Capitulations, which gave foreign nationals a virtual status of exterritoriality: the minority groups affected were mainly from Syria, Greece, and Italy, ethnic Armenians, and some Jews who were nationals of other countries. The foreign nationals‘ immunity from taxation ('' mutamassir'') had given the minority groups trading within Egypt highly favourable advantages. Many European Jews used Egyptian banks as a vehicle for transferring money from central Europe, not least those Jews escaping the Fascist regimes. In addition to this, many Jewish people living in Egypt were known to possess foreign citizenship, while those possessing Egyptian citizenship often had extensive ties to European countries.

The impact of the well-publicized Arab-Jewish clash in Palestine from 1936 to 1939, together with the rise of Nazi Germany, also began to affect Jewish relations with Egyptian society, despite the fact that the number of active Zionists in their ranks was small. The rise of local militant nationalistic societies like ''Young Egypt'' and the ''Society of Muslim Brothers'', who were sympathetic to the various models evinced by the Axis Powers in Europe, and organized themselves along similar lines, were also increasingly antagonistic to Jews. Groups including the Muslim Brotherhood circulated reports in Egyptian mosques and factories claiming that Jews and the British were destroying holy places in Jerusalem, as well as sending other false reports stating that hundreds of Arab women and children were being killed. The leader of the popular liberal Wafd party

The Wafd Party (; , ''Ḥizb al-Wafd'') was a nationalist Liberalism, liberal political party in Egypt. It was said to be Egypt's most popular and influential political party for a period from the end of World War I through the 1930s. During th ...

Mustafa al-Nahhas led the movement against Young Egypt's radicalism, going so far as to promise rabbi Chaim Nahum

Chaim (Haim) Nahum Effendi (; ; ) (1872–1960) was a Turkish Jewish scholar, jurist, and linguist of the early 20th century.

He served as the Grand Rabbi of the Ottoman Empire.Kuneralp, Sinan. "Ottoman Diplomatic and Consular Personnel in t ...

that if Egypt were to fall to Nazi Germany, Egypt would not enact any anti-Jewish laws. Much of the anti-Semitism of the 1930s and 1940s was fueled by a close association between Hitler's new regime in Germany and anti-imperialist Arab powers. One of these Arab authorities was Haj Amin al-Husseini

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini (; 4 July 1974) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine. was the scion of the family of Jerusalemite Arab nobles, who trace their origins to the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Hussein ...

, who was influential in securing Nazi funds that were appropriated to the Muslim Brotherhood for the operation of a printing press for the distribution of thousands of Anti-Semitic propaganda pamphlets.

The situation worsened in the late 1930s, with the growth of what Georges Bensoussan

Georges Bensoussan (born 17 February 1952) is a French historian. Bensoussan was born in Morocco. He is the editor of the '' Revue d'histoire de la Shoah'' ("Shoah History Review"). He won the Memory of the Shoah Prize from the Jacob Buchman Found ...

referred to as "Nazification," "propaganda," and "militant Judeophobia." In 1939, bombs were discovered in synagogues in Cairo.

The Jewish quarter of Cairo was severely damaged in the 1945 Cairo pogrom. As the Partition of Palestine

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations to partition Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. Drafted by the U.N. Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) on 3 September 1947, the Pl ...

and the founding of Israel drew closer, hostility towards the Egyptian Jews strengthened, fed also by press attacks on all foreigners accompanying the rising ethnocentric nationalism of the age.

The legal nationality of the Jewish population at this period was and is a contentious point, as some authors have argued that most of the population were foreigners and not 'real' Egyptians. Egyptian censuses give the figures for the population of Jews as 63,550 in 1927, 62,953 in 1929 and 65,953 in 1947. Najat Abdulhaq (2016) argues that a previously accepted figure of 5,000 Jews with Egyptian nationality is an politically motivated underestimate. The 1947 census had counted 50,831 Jews as Egyptian nationals; this number counted those who had lived in Egyptian for two generations, spoke Arabic and identified as Egyptian, not necessarily if they had the papers to prove it. Ironically, Jews who felt comfortable in identifying as Egyptians, even 'foreign' Sephardic Jews, did not feel the need to register themselves, while Ashkenazi Jews who fled pogroms in Europe were more keen to possess papers.

In 1947, the Company Law set quotas for employing Egyptian nationals in incorporated firms, requiring that 75% of salaried employees, and 90% of all workers, must be Egyptian. As Jews were often considered foreign or stateless persons, this constrained Jewish and foreign-owned entrepreneurs to reduce recruitment for employment positions from their own ranks. The law also required that just over half of the paid-up capital of joint stock companies be Egyptian.

The Egyptian Prime Minister Nuqrashi told the British ambassador: