Ivor Armstrong Richards on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ivor Armstrong Richards CH (26 February 1893 – 7 September 1979), known as I. A. Richards, was an English educator,

Principles of Literary Criticism

' (1924), ''Practical Criticism'' (1929), and ''The Philosophy of Rhetoric'' (1936).

"Richards, Ivor Armstrong (1893–1979)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, October 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2024. In the 1929–30 biennium, as a visiting professor, he taught

Richards elaborated on an approach to literary criticism in ''The Principles of Literary Criticism'' (1924) and ''Practical Criticism'' (1929) which embodied aspects of the scientific approach from his study of psychology, particularly that of

Richards elaborated on an approach to literary criticism in ''The Principles of Literary Criticism'' (1924) and ''Practical Criticism'' (1929) which embodied aspects of the scientific approach from his study of psychology, particularly that of

The Principles of Literary Criticism

', Richards discusses the subjects of

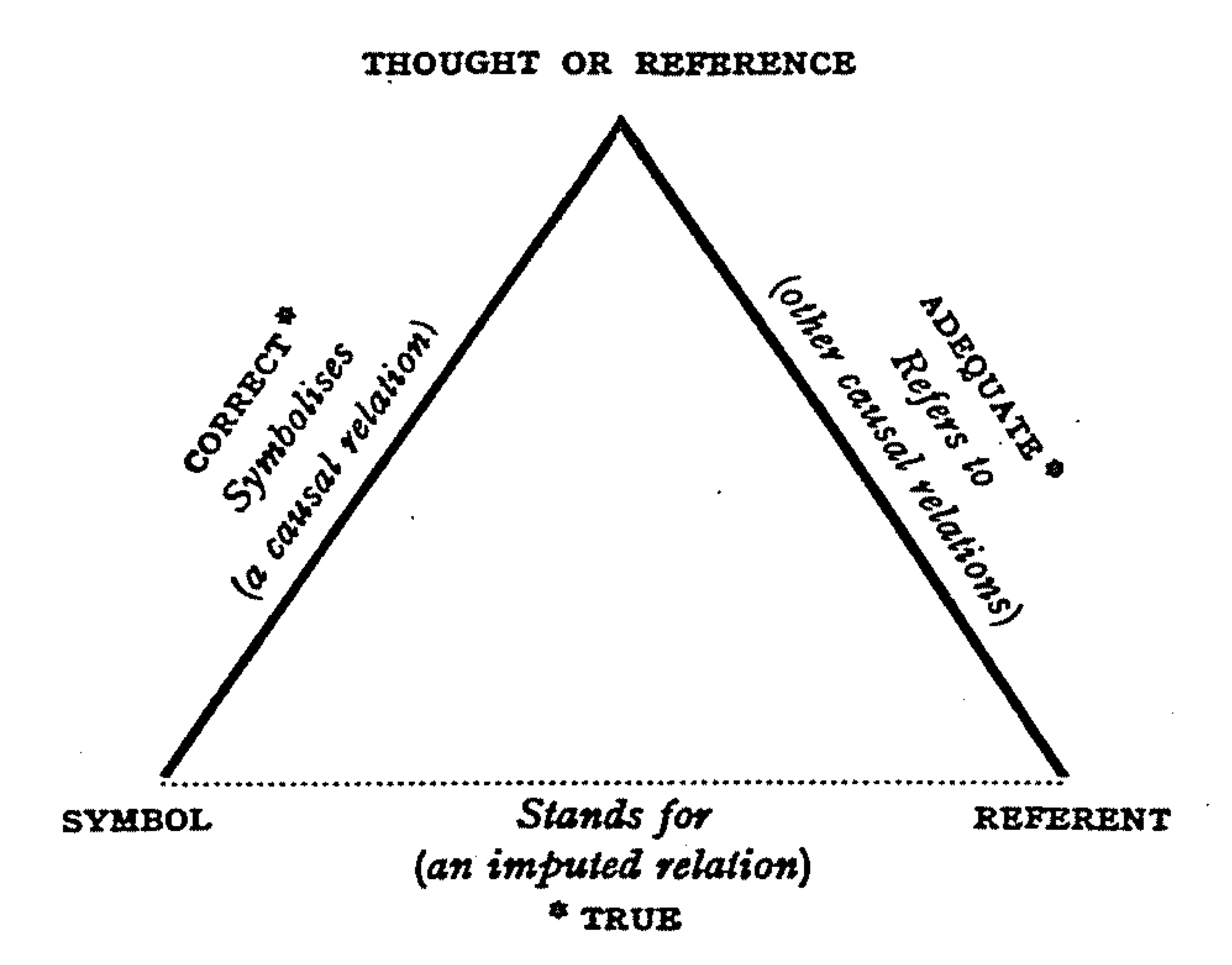

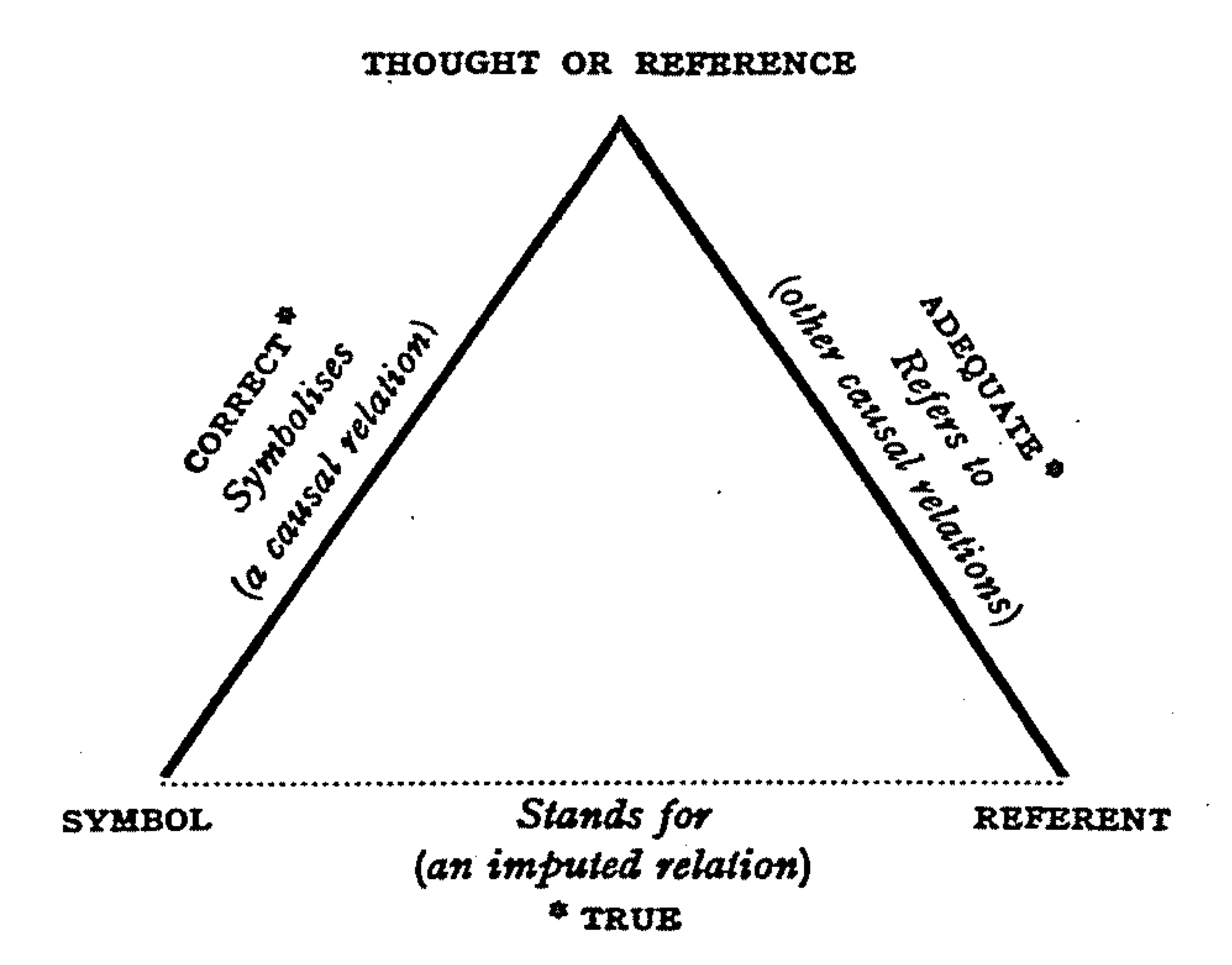

Richards and Ogden created the semantic triangle to deliver an improved understanding of how words come to mean. The semantic triangle has three parts, the symbol or word, the referent, and the thought or reference. In the bottom, right corner is the referent, the thing, in reality. Placed in the left corner is the symbol or word. At the top point, the convergence of the literal word and the object in reality; it is our intangible idea about the object. Ultimately, the English meaning of the words is determined by an individual's unique experience.

Richards and Ogden created the semantic triangle to deliver an improved understanding of how words come to mean. The semantic triangle has three parts, the symbol or word, the referent, and the thought or reference. In the bottom, right corner is the referent, the thing, in reality. Placed in the left corner is the symbol or word. At the top point, the convergence of the literal word and the object in reality; it is our intangible idea about the object. Ultimately, the English meaning of the words is determined by an individual's unique experience.

''Practical Criticism''

The Open Archive's copy of the first edition, 2nd impression, 1930; downloadable in DjVu, PDF and text formats. *''

I.A. Richards page from the Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory

(subscription required)

I.A. Richards page from LiteraryDictionary.com

* Richard Storer, 'Richards, Ivor Armstrong (1893–1979)'

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 18 May 2007 *

I.A. Richards' visit to the United States in May 1931 to meet American literary critic and New Rhetoric proponent Sterling A. Leonard, who had arranged for him to speak at the University of Wisconsin, his shock at being present at Dr. Leonard's death the next day when the two men were canoeing together on Lake Mendota and the canoe overturned. 3 July 2013: NEW INFORMATION from Dr. Leonard's grandson Tim Reynolds just added to this link: "Dr. Richards said he saw Dr. Leonard lose his grip and start to sink and he instinctively dived down, reaching for him. His hand brushed Sterling's bald head. Dr. R. told Tim, 'For a long time afterwards I was haunted with bad dreams, dreaming that Sterling was trying to come up and that my hand brushing across his head kept him from being able to.' Dr. R. told Dr. Leonard's grandson that he and Sterling had had a productive afternoon together and he believed if Dr. Leonard had survived, they (together) would have 'revolutionized English teaching.' Tim says Dr. R. seemed more concerned about him (Tim) than the past events and "he reassured me my grandfather was a very important person." {{DEFAULTSORT:Richards, Ivor 1893 births People educated at Clifton College 1979 deaths Alumni of Magdalene College, Cambridge Semioticians People from Sandbach English literary critics New Criticism English rhetoricians Communication scholars Cyberneticists Corresponding fellows of the British Academy Translation theorists British mountain climbers Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge

literary critic

A genre of arts criticism, literary criticism or literary studies is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis of literature' ...

, poet, and rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

ian. His work contributed to the foundations of New Criticism

New Criticism was a Formalism (literature), formalist movement in literary theory that dominated American literary criticism in the middle decades of the 20th century. It emphasized close reading, particularly of poetry, to discover how a work of l ...

, a formalist

Formalism may refer to:

* Legal formalism, legal positivist view that the substantive justice of a law is a question for the legislature rather than the judiciary

* Formalism (linguistics)

* Scientific formalism

* A rough synonym to the Formal sys ...

movement in literary theory

Literary theory is the systematic study of the nature of literature and of the methods for literary analysis. Culler 1997, p.1 Since the 19th century, literary scholarship includes literary theory and considerations of intellectual history, m ...

which emphasized the close reading

In literary criticism, close reading is the careful, sustained interpretation of a brief passage of a text. A close reading emphasizes the single and the particular over the general, via close attention to individual words, the syntax, the order ...

of a literary text, especially poetry

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

, in an effort to discover how a work of literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

functions as a self-contained and self-referential æsthetic object.

Richards' intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

contributions to the establishment of the literary methodology of New Criticism are presented in the books '' The Meaning of Meaning: A Study of the Influence of Language upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism'' (1923), by C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards, Principles of Literary Criticism

' (1924), ''Practical Criticism'' (1929), and ''The Philosophy of Rhetoric'' (1936).

Biography

Richards was born inSandbach

Sandbach (pronounced ) is a market town and civil parish in the Cheshire East borough of Cheshire, England. The civil parish contains four settlements: Sandbach, Elworth, Ettiley Heath and Wheelock, Cheshire, Wheelock. At the 2021 United Kingd ...

. He was educated at Clifton College

Clifton College is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in the city of Bristol in South West England, founded in 1862 and offering both boarding school, boarding and day school for pupils aged 13–18. In its early years, unlike mo ...

and Magdalene College, Cambridge

Magdalene College ( ) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1428 as a Benedictine hostel, in time coming to be known as Buckingham College, before being refounded in 1542 as the College of St Mary ...

, where his intellectual talents were developed by the scholar Charles Hicksonn 'Cabby' Spence. He began his career without formal training in literature; he studied philosophy (the "moral sciences") at Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

, from which derived his assertions that, in the 20th century, literary study cannot and should not be undertaken as a specialisation, in and of itself, but studied alongside a cognate field, such as philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

or rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

. His early teaching appointments were as adjunct faculty: at Cambridge, Magdalene College would not pay a salary for Richards to teach the new, and untested, academic field

An academic discipline or academic field is a subdivision of knowledge that is taught and researched at the college or university level. Disciplines are defined (in part) and recognized by the academic journals in which research is published, a ...

of English literature. Instead, like an old-style instructor, he collected weekly tuition directly from the students as they entered the classroom.

Richards was appointed a college lecturer in English and moral sciences at Magdalene in 1922. Four years later, when the Faculty of English

Faculty or faculties may refer to:

Academia

* Faculty (academic staff), professors, researchers, and teachers of a given university or college (North American usage)

* Faculty (division), a large department of a university by field of study (us ...

at Cambridge was formally established, he was awarded a permanent post as a university lecturer.Storer, Richard"Richards, Ivor Armstrong (1893–1979)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, October 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2024. In the 1929–30 biennium, as a visiting professor, he taught

Basic English

Basic English (a backronym for British American Scientific International and Commercial English) is a controlled language based on standard English, but with a greatly simplified vocabulary and grammar. It was created by the linguist and philo ...

and Poetry at Tsinghua University

Tsinghua University (THU) is a public university in Haidian, Beijing, China. It is affiliated with and funded by the Ministry of Education of China. The university is part of Project 211, Project 985, and the Double First-Class Constructio ...

, Beijing. In the 1936–38 triennium, he was the director of the Orthological Institute of China. Eventually tiring of academic life at Cambridge, in 1939 he accepted an offer to teach in the school of education at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

. Appointed a professor in 1944, he remained there until his retirement in 1963. In 1974, he returned to Cambridge, having retained his fellowship at Magdalene, and lived in Wentworth House in the grounds of the college until his death five years later.

In 1926, Richards married Dorothy Pilley, whom he had met on a mountain climbing

Mountaineering, mountain climbing, or alpinism is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas that have become mounta ...

holiday in Wales. She died in 1986. Pilley's book recounts many of the climbs they did together in the 1920's and 1930s, including their celebrated 1928 first ascent of the north north west ridge of the Dent Blanche

The Dent Blanche is a mountain in the Pennine Alps, lying in the canton of Valais in Switzerland. At -high, it is one of the highest peaks in the Alps.

Naming

The original name was probably ''Dent d'Hérens'', the current name of the nearby De ...

in the Swiss Alps.

Contributions

Collaborations with C. K. Ogden

The life and intellectual influence of I. A. Richards approximately corresponds to hisintellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

interests; many endeavours were in collaboration with the linguist

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

, philosopher, and writer Charles Kay Ogden

Charles Kay Ogden (; 1 June 1889 – 20 March 1957) was a British linguist, philosopher, and writer. Described as a polymath but also an Eccentricity (behavior), eccentric and Emic and etic, outsider, he took part in many ventures related to lit ...

(C. K. Ogden), notably in four books:

I. ''Foundations of Aesthetics'' (1922) presents the principles of ''aesthetic reception'', the bases of the literary theory of “harmony”; aesthetic understanding derives from the balance of competing psychological impulses. The structure of the ''Foundations of Aesthetics''—a survey of the competing definitions of the term ''æsthetic''—prefigures the multiple-definitions work in the books ''Basic Rules of Reason'' (1933), ''Mencius on the Mind: Experiments in Multiple Definition'' (1932), and ''Coleridge on Imagination'' (1934)

II. '' The Meaning of Meaning: A Study of the Influence of Language upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism'' (1923) presents the triadic theory of semiotics

Semiotics ( ) is the systematic study of sign processes and the communication of meaning. In semiotics, a sign is defined as anything that communicates intentional and unintentional meaning or feelings to the sign's interpreter.

Semiosis is a ...

that depends upon psychological theory, and so anticipates the importance of psychology in the exercise of literary criticism. Semioticians, such as Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco (5 January 1932 – 19 February 2016) was an Italian Medieval studies, medievalist, philosopher, Semiotics, semiotician, novelist, cultural critic, and political and social commentator. In English, he is best known for his popular ...

, acknowledged that the methodology of the triadic theory of semiotics improved upon the methodology of the dyadic theory of semiotics presented by Ferdinand de Saussure

Ferdinand Mongin de Saussure (; ; 26 November 185722 February 1913) was a Swiss linguist, semiotician and philosopher. His ideas laid a foundation for many significant developments in both linguistics and semiotics in the 20th century. He is wi ...

(1857–1913).

III. ''Basic English: A General Introduction with Rules and Grammar'' (1930) describes a simplified English based upon a vocabulary of 850 words.

IV. ''The Times of India Guide to Basic English'' (1938) sought to develop Basic English

Basic English (a backronym for British American Scientific International and Commercial English) is a controlled language based on standard English, but with a greatly simplified vocabulary and grammar. It was created by the linguist and philo ...

as an international auxiliary language, an interlanguage

An interlanguage is an idiolect developed by a learner of a second language (L2) which preserves some features of their first language (L1) and can overgeneralize some L2 writing and speaking rules. These two characteristics give an interlangu ...

.

Richards' travels, especially in China, effectively situated him as the advocate for an international program, such as Basic English. Moreover, at Harvard University, in his international pedagogy, he began to integrate the available new media for mass communications, especially television

Television (TV) is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. Additionally, the term can refer to a physical television set rather than the medium of transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, ...

.

Aesthetics and literary criticism

Theory

Richards elaborated on an approach to literary criticism in ''The Principles of Literary Criticism'' (1924) and ''Practical Criticism'' (1929) which embodied aspects of the scientific approach from his study of psychology, particularly that of

Richards elaborated on an approach to literary criticism in ''The Principles of Literary Criticism'' (1924) and ''Practical Criticism'' (1929) which embodied aspects of the scientific approach from his study of psychology, particularly that of Charles Scott Sherrington

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington (27 November 1857 – 4 March 1952) was a British neurophysiology, neurophysiologist. His experimental research established many aspects of contemporary neuroscience, including the concept of the spinal reflex as a ...

.

In The Principles of Literary Criticism

', Richards discusses the subjects of

form

Form is the shape, visual appearance, or configuration of an object. In a wider sense, the form is the way something happens.

Form may also refer to:

*Form (document), a document (printed or electronic) with spaces in which to write or enter dat ...

, value, rhythm

Rhythm (from Greek , ''rhythmos'', "any regular recurring motion, symmetry") generally means a " movement marked by the regulated succession of strong and weak elements, or of opposite or different conditions". This general meaning of regular r ...

, coenesthesia (an awareness of inhabiting one's body, caused by stimuli from various organs), literary infectiousness, allusiveness, divergent readings, and belief

A belief is a subjective Attitude (psychology), attitude that something is truth, true or a State of affairs (philosophy), state of affairs is the case. A subjective attitude is a mental state of having some Life stance, stance, take, or opinion ...

. He starts from the premise that "A book is a machine to think with, but it need not, therefore, usurp the functions either of the bellows or the locomotive."

''Practical Criticism'' (1929), is an empirical study

Empirical research is research using empirical evidence. It is also a way of gaining knowledge by means of direct and indirect observation or experience. Empiricism values some research more than other kinds. Empirical evidence (the record of one ...

of ''inferior response'' to a literary text. As an instructor in English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from the English-speaking world. The English language has developed over more than 1,400 years. The earliest forms of English, a set of Anglo-Frisian languages, Anglo-Frisian d ...

at Cambridge University, Richards tested the critical-thinking abilities of his pupils; he removed author

In legal discourse, an author is the creator of an original work that has been published, whether that work exists in written, graphic, visual, or recorded form. The act of creating such a work is referred to as authorship. Therefore, a sculpt ...

ial and contextual information from thirteen poems and asked undergraduates to write interpretations, in order to ascertain the likely impediments to an ''adequate response'' to a literary text. That experiment in the pedagogical

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political, and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken ...

approach—critical reading without contexts—demonstrated the variety and depth of the possible textual misreadings that might be committed, by university students and laymen alike.

The critical method derived from that pedagogical approach did not propose a new hermeneutics

Hermeneutics () is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. As necessary, hermeneutics may include the art of understanding and communication.

...

, a new methodology of interpretation, but questioned the purposes and efficacy of the critical process of literary interpretation, by analysing the self-reported critical interpretations of university students. To that end, effective critical work required a closer aesthetic interpretation

In the philosophy of art, an interpretation is an explanation of the meaning of a work of art.} An aesthetic interpretation expresses a particular emotional or experiential understanding most often used in reference to a poem or piece of literatu ...

of the literary text as an object.

To substantiate interpretive criticism, Richards provided theories of metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide, or obscure, clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are usually meant to cr ...

, value, and tone

Tone may refer to:

Visual arts and color-related

* Tone (color theory), a mix of tint and shade, in painting and color theory

* Tone (color), the lightness or brightness (as well as darkness) of a color

* Toning (coin), color change in coins

* ...

, of stock response, incipient action, and pseudo-statement; and of ambiguity

Ambiguity is the type of meaning (linguistics), meaning in which a phrase, statement, or resolution is not explicitly defined, making for several interpretations; others describe it as a concept or statement that has no real reference. A com ...

. This last subject, the theory of ''ambiguity'', was developed in '' Seven Types of Ambiguity'' (1930), by William Empson

Sir William Empson (27 September 1906 – 15 April 1984) was an English literary critic and poet, widely influential for his practice of closely reading literary works, a practice fundamental to New Criticism. His best-known work is his firs ...

, a former student of Richards'; moreover, additional to ''The Principles of Literary Criticism'' and ''Practical Criticism'', Empson's book on ambiguity became the third foundational document for the methodology of the New Criticism

New Criticism was a Formalism (literature), formalist movement in literary theory that dominated American literary criticism in the middle decades of the 20th century. It emphasized close reading, particularly of poetry, to discover how a work of l ...

.

To Richards, literary criticism was impressionistic

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by visible brush strokes, open Composition (visual arts), composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage ...

, too abstract to be readily grasped and understood, by most readers; and he proposed that literary criticism could be precise in communicating meanings, by way of denotation and connotation. To establish critical precision, Richards examined the psychological processes of writing and reading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of symbols, often specifically those of a written language, by means of Visual perception, sight or Somatosensory system, touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifacete ...

poetry. In reading poetry and making sense of it "in the degree in which we can order ourselves, we need nothing more"; the reader need not believe the poetry, because the literary importance of poetry is in provoking emotions in the reader.

New rhetoric

As a rhetorician, Richards said that the old form of studyingrhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

(the art of discourse

Discourse is a generalization of the notion of a conversation to any form of communication. Discourse is a major topic in social theory, with work spanning fields such as sociology, anthropology, continental philosophy, and discourse analysis. F ...

) was too concerned with the mechanics of formulating argument

An argument is a series of sentences, statements, or propositions some of which are called premises and one is the conclusion. The purpose of an argument is to give reasons for one's conclusion via justification, explanation, and/or persu ...

s and with conflict; instead, he proposed the New Rhetoric to study the meaning of the parts of discourse, as "a study of misunderstanding and its remedies" to determine how language works. That ambiguity

Ambiguity is the type of meaning (linguistics), meaning in which a phrase, statement, or resolution is not explicitly defined, making for several interpretations; others describe it as a concept or statement that has no real reference. A com ...

is expected, and that meanings (denotation and connotation) are not inherent to words, but are inherent to the perception of the reader, the listener, and the viewer. By their usages, compiled from experience, people decide and determine meaning by "how words are used in a sentence", in spoken and written language.Hochmuth, Marie. "I. A Richards and the 'New Rhetoric' new royal", ''Quarterly Journal of Speech'' 44.1 (1958): 1. Communication & Mass Media Complete.

= The semantic triangle

= Richards and Ogden created the semantic triangle to deliver an improved understanding of how words come to mean. The semantic triangle has three parts, the symbol or word, the referent, and the thought or reference. In the bottom, right corner is the referent, the thing, in reality. Placed in the left corner is the symbol or word. At the top point, the convergence of the literal word and the object in reality; it is our intangible idea about the object. Ultimately, the English meaning of the words is determined by an individual's unique experience.

Richards and Ogden created the semantic triangle to deliver an improved understanding of how words come to mean. The semantic triangle has three parts, the symbol or word, the referent, and the thought or reference. In the bottom, right corner is the referent, the thing, in reality. Placed in the left corner is the symbol or word. At the top point, the convergence of the literal word and the object in reality; it is our intangible idea about the object. Ultimately, the English meaning of the words is determined by an individual's unique experience.

Feedforward

When the ''Saturday Review'' asked Richards to write a piece for their "What I Have Learned" series, Richards (then aged 75) took the opportunity to expound upon hiscybernetic

Cybernetics is the transdisciplinary study of circular causal processes such as feedback and recursion, where the effects of a system's actions (its outputs) return as inputs to that system, influencing subsequent action. It is concerned with ...

concept of "feedforward". The ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the principal historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP), a University of Oxford publishing house. The dictionary, which published its first editio ...

'' records that Richards coined the term feedforward in 1951 at the Eighth Macy Conferences

The Macy conferences were a set of meetings of scholars from various academic disciplines held in New York under the direction of Frank Fremont-Smith at the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation starting in 1941 and ending in 1960. The explicit aim of th ...

on cybernetics

Cybernetics is the transdisciplinary study of circular causal processes such as feedback and recursion, where the effects of a system's actions (its outputs) return as inputs to that system, influencing subsequent action. It is concerned with ...

. In the event, the term extended the intellectual and critical influence of Richards to cybernetics which applied the term in a variety of contexts. Moreover, among Richards' students was Marshall McLuhan

Herbert Marshall McLuhan (, ; July 21, 1911 – December 31, 1980) was a Canadian philosopher whose work is among the cornerstones of the study of media studies, media theory. Raised in Winnipeg, McLuhan studied at the University of Manitoba a ...

, who also applied and developed the term and the concept of feedforward.

According to Richards, feedforward is the concept of anticipating the effect of one's words by acting as our own critic. It is thought to work in the opposite direction of feedback, though it works essentially towards the same goal: to clarify unclear concepts. Existing in all forms of communication, feedforward acts as a pretest that any writer can use to anticipate the impact of their words on their audience. According to Richards, feedforward allows the writer to then engage with their text to make necessary changes to create a better effect. He believes that communicators who do not use feedforward will seem dogmatic. Richards wrote more in depth about the idea and importance of feedforward in communication in his book ''Speculative Instruments'' and said that feedforward was his most important learned concept.

Influence

Richards served as a mentor and teacher to other prominent critics, most notablyWilliam Empson

Sir William Empson (27 September 1906 – 15 April 1984) was an English literary critic and poet, widely influential for his practice of closely reading literary works, a practice fundamental to New Criticism. His best-known work is his firs ...

and F. R. Leavis

Frank Raymond "F. R." Leavis ( ; 14 July 1895 – 14 April 1978) was an English literary critic of the early-to-mid-twentieth century. He taught for much of his career at Downing College, Cambridge, and later at the University of York.

Leav ...

, although Leavis was contemporary with Richards, and Empson was much younger. Other critics primarily influenced by his writings included Cleanth Brooks

Cleanth Brooks ( ; October 16, 1906 – May 10, 1994) was an American literary critic and professor. He is best known for his contributions to New Criticism in the mid-20th century and for revolutionizing the teaching of poetry in American higher ...

and Allen Tate

John Orley Allen Tate (November 19, 1899 – February 9, 1979), known professionally as Allen Tate, was an American poet, essayist, social commentator, and poet laureate from 1943 to 1944. Among his best known works are the poems " Ode to th ...

. Later critics who refined the formalist approach to New Criticism by actively rejecting his psychological emphasis included, besides Brooks and Tate, John Crowe Ransom

John Crowe Ransom (April 30, 1888 – July 3, 1974) was an American educator, scholar, literary critic, poet, essayist and editor. He is considered to be a founder of the New Criticism school of literary criticism. As a faculty member at Kenyon ...

, W. K. Wimsatt

William Kurtz Wimsatt Jr. (November 17, 1907 – December 17, 1975) was an American professor of English, literary theorist, and critic. Wimsatt is often associated with the concept of the intentional fallacy, which he developed with Monroe Beard ...

, R. P. Blackmur, and Murray Krieger

Murray Krieger (November 27, 1923 – August 5, 2000) was an American literary critic and theorist. He was a professor at the University of Minnesota, the University of Iowa from 1963, and then the University of California, Irvine. In 1999, t ...

. R. S. Crane of the Chicago School was both indebted to Richards's theory and critical of its psychological assumptions. They all admitted the value of his seminal ideas but sought to salvage what they considered his most useful assumptions from the theoretical excesses they felt he brought to bear in his criticism. Like Empson, Richards proved a difficult model for the New Critics, but his model of close reading

In literary criticism, close reading is the careful, sustained interpretation of a brief passage of a text. A close reading emphasizes the single and the particular over the general, via close attention to individual words, the syntax, the order ...

provided the basis for their interpretive methodology.

Works

* ''The Foundations of Aesthetics'' (George Allen and Unwin: London, 1922); co-authored with C. K. Ogden, and James Wood. 2nd ed. with revised preface, (Lear Publishers: New York 1925). * ''The Principles of Literary Criticism'' (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner: London, 1924; New York, 1925); subsequent eds.: London 1926 (with two new appendices), New York 1926; London 1926, with new preface, New York, April 1926; and 1928, with a revised preface. * ''Science and Poetry'' (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner: London, 1926).; reset edition, New York, W. W. Norton, 1926; 2nd ed., revised and enlarged: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner: London, 1935. The 1935 edition was reset, with a preface, a commentary, and the essay, “How Does a Poem Know When it is Finished” (1963), as ''Poetries and Sciences'' (W. W. Norton: New York and London, 1970). * ''Practical Criticism'' (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner: London, 1929); revised edition, 1930. * ''Coleridge on Imagination'' (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner: London, 1934; New York, 1935); revised editions with a new preface, New York and London 1950; Bloomington, 1960; reprints 1950, with new foreword by Richards, and an introduction by K. Raine. * ''The Philosophy of Rhetoric'' (Oxford UP: London, 1936). * ''Speculative Instruments'' (Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, 1955). * ''So Much Nearer: Essays toward a World English'' (Harcourt, Brace & World: New York, 1960, 1968), includes the essay, "The Future of Poetry".Rhetoric, semiotics and prose interpretation

Works

*''The Meaning of Meaning: A Study of the Influence of Language upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism''. Co-authored with C. K. Ogden. With an introduction byJ. P. Postgate

John Percival Postgate, Fellow of the British Academy, FBA (24 October 1853 – 15 July 1926) was an England, English classics, classicist and academic. He was a Fellow (Oxbridge), fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge from 1878 until his death ...

, and supplementary essays by Bronisław Malinowski

Bronisław Kasper Malinowski (; 7 April 1884 – 16 May 1942) was a Polish anthropologist and ethnologist whose writings on ethnography, social theory, and field research have exerted a lasting influence on the discipline of anthropology.

...

, 'The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Languages', and F. G. Crookshank, 'The Importance of a Theory of Signs and a Critique of Language in the Study of Medicine'. London and New York, 1923.

:1st: 1923 (Preface Date: Jan. 1923)

:2nd: 1927 (Preface Date: June 1926)

:3rd: 1930 (Preface Date: Jan. 1930)

:4th: 1936 (Preface Date: May 1936)

:5th: 1938 (Preface Date: June 1938)

:8th: 1946 (Preface Date: May 1946)

:NY: 1989 (with a preface by Umberto Eco)

*''Mencius on the Mind: Experiments in Multiple Definition'' (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.: London; Harcourt, Brace: New York, 1932).

*''Basic Rules of Reason'' (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.: London, 1933).

*''The Philosophy of Rhetoric'' (Oxford University Press: New York and London, 1936).

*''Interpretation in Teaching'' (Routledge & Kegan Paul: London; Harcourt, Brace: New York, 1938). Subsequent editions: 1973 (with 'Retrospect').

*''Basic in Teaching: East and West'' (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner: London, 1935).

*''How To Read a Page: A Course in Effective Reading, With an Introduction to a Hundred Great Words'' (W. W. Norton: New York, 1942; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, 1943). Subsequent editions: 1959 (Beacon Press: Boston. With new 'Introduction').

*''The Wrath of Achilles: The Iliad of Homer, Shortened and in a New Translation'' (W. W. Norton: New York, 1950; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, 1951).

*''So Much Nearer: Essays toward a World English'' (Harcourt, Brace & World: New York, 1960, 1968). Includes the important essay, "The Future of Poetry."

*''Complementarities: Uncollected Essays,'' ed. by John Paul Russo (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1976).

*''Times of India Guide to Basic English'' (Bombay

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial centre, financial capital and the list of cities i ...

: The Times of India Press), 1938; Odgen, C. K. & Richards, I. A.

See also

* M. H. AbramsReferences

Further reading

*Howarth, T. E. B., ''Cambridge Between Two Wars'' (London: Collins, 1978) * *Tong, Q. S. "The Bathos of a Universalism, I. A. Richards and His Basic English." In ''Tokens of Exchange: The Problem of Translation in Global Circulation.'' Duke University Press, 1999. 331–354.External links

''Practical Criticism''

The Open Archive's copy of the first edition, 2nd impression, 1930; downloadable in DjVu, PDF and text formats. *''

The Meaning Of Meaning

''The Meaning of Meaning: A Study of the Influence of Language upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism'' (1923) is a book by C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards. It is accompanied by two supplementary essays by Bronisław Malinowski and F. G ...

'' at Internet Archive

I.A. Richards page from the Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory

(subscription required)

I.A. Richards page from LiteraryDictionary.com

* Richard Storer, 'Richards, Ivor Armstrong (1893–1979)'

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 18 May 2007 *

Barbara Leonard Reynolds

Barbara Leonard Reynolds (born Barbara Dorrit Leonard; Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, June 12, 1915 – February 11, 1990), was an American author who became a Quaker, peace activist and educator.

In 1951, Reynolds moved with her husband t ...

I.A. Richards' relationship with his American mentor, author and educator Sterling A. Leonard.

* Jessica Renshaw, 'FAMILY: My Grandfather SterlingI.A. Richards' visit to the United States in May 1931 to meet American literary critic and New Rhetoric proponent Sterling A. Leonard, who had arranged for him to speak at the University of Wisconsin, his shock at being present at Dr. Leonard's death the next day when the two men were canoeing together on Lake Mendota and the canoe overturned. 3 July 2013: NEW INFORMATION from Dr. Leonard's grandson Tim Reynolds just added to this link: "Dr. Richards said he saw Dr. Leonard lose his grip and start to sink and he instinctively dived down, reaching for him. His hand brushed Sterling's bald head. Dr. R. told Tim, 'For a long time afterwards I was haunted with bad dreams, dreaming that Sterling was trying to come up and that my hand brushing across his head kept him from being able to.' Dr. R. told Dr. Leonard's grandson that he and Sterling had had a productive afternoon together and he believed if Dr. Leonard had survived, they (together) would have 'revolutionized English teaching.' Tim says Dr. R. seemed more concerned about him (Tim) than the past events and "he reassured me my grandfather was a very important person." {{DEFAULTSORT:Richards, Ivor 1893 births People educated at Clifton College 1979 deaths Alumni of Magdalene College, Cambridge Semioticians People from Sandbach English literary critics New Criticism English rhetoricians Communication scholars Cyberneticists Corresponding fellows of the British Academy Translation theorists British mountain climbers Fellows of Magdalene College, Cambridge