History Of The Qing Dynasty on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Qing dynasty began in the first half of the 17th century, when the

Two years later, Nurhaci announced the "

Two years later, Nurhaci announced the " Some other important contributions by Nurhaci include ordering the creation of a written Manchu script, based on

Some other important contributions by Nurhaci include ordering the creation of a written Manchu script, based on

To redress the technological and numerical disparity, Hong Taiji created his own artillery corps in 1634, the ''ujen cooha'' (Chinese: ) from his existing Han troops who cast their own cannons in the European design with the help of defector Chinese metallurgists. One of the defining events of Hong Taiji's reign was the official adoption of the name "Manchu" for the united Jurchen people in November 1635. In 1635, the Manchus' Mongol allies were fully incorporated into a separate Banner hierarchy under direct Manchu command. Hong Taiji conquered the territory north of

To redress the technological and numerical disparity, Hong Taiji created his own artillery corps in 1634, the ''ujen cooha'' (Chinese: ) from his existing Han troops who cast their own cannons in the European design with the help of defector Chinese metallurgists. One of the defining events of Hong Taiji's reign was the official adoption of the name "Manchu" for the united Jurchen people in November 1635. In 1635, the Manchus' Mongol allies were fully incorporated into a separate Banner hierarchy under direct Manchu command. Hong Taiji conquered the territory north of  Meanwhile, Hong Taiji set up a rudimentary bureaucratic system based on the Ming model. He established six boards or executive level ministries in 1631 to oversee finance, personnel, rites, military, punishments, and public works. However, these administrative organs had very little role initially, and it was not until the eve of completing the conquest ten years later that they fulfilled their government roles.

Hong Taiji's bureaucracy was staffed with many Han Chinese, including many newly surrendered Ming officials. The Manchus' continued dominance was ensured by an ethnic quota for top bureaucratic appointments. Hong Taiji's reign also saw a fundamental change of policy towards his Han Chinese subjects. Nurhaci had treated Han in Liaodong differently according to how much grain they had: those with less than 5 to 7 sin were treated badly, while those with more than that amount were rewarded with property. Due to a revolt by Han in Liaodong in 1623, Nurhaci, who previously gave concessions to conquered Han subjects in Liaodong, turned against them and ordered that they no longer be trusted. He enacted discriminatory policies and killings against them, while ordering that Han who assimilated to the Jurchen (in Jilin) before 1619 be treated equally, as Jurchens were, and not like the conquered Han in Liaodong. Hong Taiji recognized that the Manchus needed to attract Han Chinese, explaining to reluctant Manchus why he needed to treat the Ming defector General

Meanwhile, Hong Taiji set up a rudimentary bureaucratic system based on the Ming model. He established six boards or executive level ministries in 1631 to oversee finance, personnel, rites, military, punishments, and public works. However, these administrative organs had very little role initially, and it was not until the eve of completing the conquest ten years later that they fulfilled their government roles.

Hong Taiji's bureaucracy was staffed with many Han Chinese, including many newly surrendered Ming officials. The Manchus' continued dominance was ensured by an ethnic quota for top bureaucratic appointments. Hong Taiji's reign also saw a fundamental change of policy towards his Han Chinese subjects. Nurhaci had treated Han in Liaodong differently according to how much grain they had: those with less than 5 to 7 sin were treated badly, while those with more than that amount were rewarded with property. Due to a revolt by Han in Liaodong in 1623, Nurhaci, who previously gave concessions to conquered Han subjects in Liaodong, turned against them and ordered that they no longer be trusted. He enacted discriminatory policies and killings against them, while ordering that Han who assimilated to the Jurchen (in Jilin) before 1619 be treated equally, as Jurchens were, and not like the conquered Han in Liaodong. Hong Taiji recognized that the Manchus needed to attract Han Chinese, explaining to reluctant Manchus why he needed to treat the Ming defector General

The first seven years of the Shunzhi Emperor's reign were dominated by the regent prince Dorgon. Because of his own political insecurity, Dorgon followed Hong Taiji's example by ruling in the name of the emperor at the expense of rival Manchu princes, many of whom he demoted or imprisoned under one pretext or another. Although the period of his regency was relatively short, Dorgon's precedents and example cast a long shadow over the dynasty.

First, the Manchus had entered "South of the Wall" because Dorgon responded decisively to Wu Sangui's appeal. Then, after capturing Beijing, instead of sacking the city as the rebels had done, Dorgon insisted, over the protests of other Manchu princes, on making it the dynastic capital and reappointing most Ming officials. Choosing Beijing as the capital had not been a straightforward decision, since no major Chinese dynasty had directly taken over its immediate predecessor's capital. Keeping the Ming capital and bureaucracy intact helped quickly stabilize the regime and sped up the conquest of the rest of the country. Dorgon then drastically reduced the influence of the eunuchs, a major force in the Ming bureaucracy, and directed Manchu women not to bind their feet in the Chinese style.

However, not all of Dorgon's policies were equally popular or as easy to implement. The controversial July 1645 edict (the "haircutting order") forced adult Han Chinese men to shave the front of their heads and comb the remaining hair into the queue hairstyle which was worn by Manchu men, on pain of death. The popular description of the order was: "To keep the hair, you lose the head; To keep your head, you cut the hair." To the Manchus, this policy was a test of loyalty and an aid in distinguishing friend from foe. For the Han Chinese, however, it was a humiliating reminder of Qing authority that challenged traditional Confucian values. The ''

The first seven years of the Shunzhi Emperor's reign were dominated by the regent prince Dorgon. Because of his own political insecurity, Dorgon followed Hong Taiji's example by ruling in the name of the emperor at the expense of rival Manchu princes, many of whom he demoted or imprisoned under one pretext or another. Although the period of his regency was relatively short, Dorgon's precedents and example cast a long shadow over the dynasty.

First, the Manchus had entered "South of the Wall" because Dorgon responded decisively to Wu Sangui's appeal. Then, after capturing Beijing, instead of sacking the city as the rebels had done, Dorgon insisted, over the protests of other Manchu princes, on making it the dynastic capital and reappointing most Ming officials. Choosing Beijing as the capital had not been a straightforward decision, since no major Chinese dynasty had directly taken over its immediate predecessor's capital. Keeping the Ming capital and bureaucracy intact helped quickly stabilize the regime and sped up the conquest of the rest of the country. Dorgon then drastically reduced the influence of the eunuchs, a major force in the Ming bureaucracy, and directed Manchu women not to bind their feet in the Chinese style.

However, not all of Dorgon's policies were equally popular or as easy to implement. The controversial July 1645 edict (the "haircutting order") forced adult Han Chinese men to shave the front of their heads and comb the remaining hair into the queue hairstyle which was worn by Manchu men, on pain of death. The popular description of the order was: "To keep the hair, you lose the head; To keep your head, you cut the hair." To the Manchus, this policy was a test of loyalty and an aid in distinguishing friend from foe. For the Han Chinese, however, it was a humiliating reminder of Qing authority that challenged traditional Confucian values. The ''

The sixty-one year reign of the

The sixty-one year reign of the  The second major source of stability was the

The second major source of stability was the  Manchu Generals and Bannermen were initially put to shame by the better performance of the Han Chinese

Manchu Generals and Bannermen were initially put to shame by the better performance of the Han Chinese

The reigns of the

The reigns of the  Yongzheng also inherited diplomatic and strategic problems. A team made up entirely of Manchus drew up the

Yongzheng also inherited diplomatic and strategic problems. A team made up entirely of Manchus drew up the  The Qianlong Emperor launched several ambitious cultural projects, including the compilation of the ''

The Qianlong Emperor launched several ambitious cultural projects, including the compilation of the '' China also began suffering from mounting overpopulation during this period. Population growth was stagnant for the first half of the 17th century due to civil wars and epidemics, but prosperity and internal stability gradually reversed this trend. The introduction of new crops from the Americas such as the

China also began suffering from mounting overpopulation during this period. Population growth was stagnant for the first half of the 17th century due to civil wars and epidemics, but prosperity and internal stability gradually reversed this trend. The introduction of new crops from the Americas such as the

Demand in Europe for Chinese goods such as silk, tea, and ceramics could only be met if European companies funneled their limited supplies of silver into China. In the late 1700s, the governments of Britain and France were deeply concerned about the imbalance of trade and the drain of silver. To meet the growing Chinese demand for opium, the British East India Company greatly expanded its production in Bengal. Since China's economy was essentially self-sufficient, the country had little need to import goods or raw materials from the Europeans, so the usual way of payment was through silver. The

Demand in Europe for Chinese goods such as silk, tea, and ceramics could only be met if European companies funneled their limited supplies of silver into China. In the late 1700s, the governments of Britain and France were deeply concerned about the imbalance of trade and the drain of silver. To meet the growing Chinese demand for opium, the British East India Company greatly expanded its production in Bengal. Since China's economy was essentially self-sufficient, the country had little need to import goods or raw materials from the Europeans, so the usual way of payment was through silver. The  The

The  The Western powers, largely unsatisfied with the Treaty of Nanjing, gave grudging support to the Qing government during the Taiping and

The Western powers, largely unsatisfied with the Treaty of Nanjing, gave grudging support to the Qing government during the Taiping and

The dynasty lost control of peripheral territories bit by bit. In return for promises of support against the British and the French, the

The dynasty lost control of peripheral territories bit by bit. In return for promises of support against the British and the French, the  These years saw an evolution in the participation of

These years saw an evolution in the participation of

By the early 20th century, mass civil disorder had begun in China, and it was growing continuously. To overcome such problems,

By the early 20th century, mass civil disorder had begun in China, and it was growing continuously. To overcome such problems,  The Guangxu Emperor died on 14 November 1908, and on 15 November 1908, Cixi also died. Rumors held that she or

The Guangxu Emperor died on 14 November 1908, and on 15 November 1908, Cixi also died. Rumors held that she or  Premier Yuan Shikai and his Beiyang commanders decided that going to war would be unreasonable and costly. Similarly, Sun Yat-sen wanted a republican constitutional reform, for the benefit of China's economy and populace. With permission from Empress Dowager Longyu, Yuan Shikai began negotiating with Sun Yat-sen, who decided that his goal had been achieved in forming a republic, and that therefore he could allow Yuan to step into the position of

Premier Yuan Shikai and his Beiyang commanders decided that going to war would be unreasonable and costly. Similarly, Sun Yat-sen wanted a republican constitutional reform, for the benefit of China's economy and populace. With permission from Empress Dowager Longyu, Yuan Shikai began negotiating with Sun Yat-sen, who decided that his goal had been achieved in forming a republic, and that therefore he could allow Yuan to step into the position of

Vol 1 of 1943 edition Internet ArchiveVol 2 Internet Archive

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Online

at

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

was established and became the last imperial dynasty of China, succeeding the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

(1368–1644). The Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic peoples, Tungusic East Asian people, East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized Ethnic minorities in China, ethnic minority in China and the people from wh ...

leader Hong Taiji

Hong Taiji (28 November 1592 – 21 September 1643), also rendered as Huang Taiji and sometimes referred to as Abahai in Western literature, also known by his temple name as the Emperor Taizong of Qing, was the second khan of the Later Jin ...

(Emperor Taizong) renamed the Later Jin established by his father Nurhaci

Nurhaci (14 May 1559 – 30 September 1626), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Taizu of Qing, was the founding khan of the Jurchen people, Jurchen-led Later Jin (1616–1636), Later Jin dynasty.

As the leader of the House of Aisin-Gi ...

to "Great Qing" in 1636, sometimes referred to as the Predynastic Qing in historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

. By 1644 the Shunzhi Emperor

The Shunzhi Emperor (15 March 1638 – 5 February 1661), also known by his temple name Emperor Shizu of Qing, personal name Fulin, was the second Emperor of China, emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the first Qing emperor to rule over China pro ...

and his prince regent

A prince regent or princess regent is a prince or princess who, due to their position in the line of succession, rules a monarchy as regent in the stead of a monarch, e.g., as a result of the sovereign's incapacity (minority or illness) or ab ...

seized control of the Ming capital Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

, and the year 1644 is generally considered the start of the dynasty's rule. The Qing dynasty lasted until 1912, when Puyi

Puyi (7 February 190617 October 1967) was the final emperor of China, reigning as the eleventh monarch of the Qing dynasty from 1908 to 1912. When the Guangxu Emperor died without an heir, Empress Dowager Cixi picked his nephew Puyi, aged tw ...

(Xuantong Emperor) abdicated the throne in response to the 1911 Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China (ROC). The revolution was the culmination of a decade ...

. As the final imperial dynasty in Chinese history

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

, the Qing dynasty reached heights of power unlike any of the Chinese dynasties

For most of its history, China was organized into various Dynasty, dynastic states under the rule of Hereditary monarchy, hereditary monarchs. Beginning with the establishment of dynastic rule by Yu the Great , and ending with the Imperial Edic ...

which preceded it, engaging in large-scale territorial expansion which ended with embarrassing defeat and humiliation to the foreign powers whom they believe to be inferior to them. The Qing dynasty's inability to successfully counter Western and Japanese imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

ultimately led to its downfall, and the instability which emerged in China during the final years of the dynasty ultimately paved the way for the Warlord Era

The Warlord Era was the period in the history of the Republic of China between 1916 and 1928, when control of the country was divided between rival Warlord, military cliques of the Beiyang Army and other regional factions. It began after the de ...

.

Though he did not officially found the Qing dynasty, Later Jin ruler Nurhaci, originally a Ming vassal who officially considered himself a local representative of imperial Ming power,The Cambridge History of China: Volume 9, The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, Part 1, by Willard J. Peterson, p. 29 laid the foundation for its emergence through his policies of uniting various Jurchen tribes, consolidating the Eight Banners

The Eight Banners (in Manchu language, Manchu: ''jakūn gūsa'', , ) were administrative and military divisions under the Later Jin (1616–1636), Later Jin and Qing dynasty, Qing dynasties of China into which all Manchu people, Manchu househol ...

military system and conquering territory from the Ming after he openly renounced the Ming overlordship with the Seven Grievances

The ''Seven Grievances'' (Manchu: ''nadan koro''; ) was a manifesto announced by Nurhaci, khan of the Later Jin, on the thirteenth day of the fourth lunar month in the third year of the ''Tianming'' () era of his reign; 7 May 1618. It effecti ...

in 1618. His son, Hong Taiji, who officially proclaimed the Qing dynasty, consolidated the territories that he had inherited control over from Nurhaci and laid the groundwork for the conquest of the Ming dynasty, although he died before this was accomplished. As Ming control disintegrated, peasant rebels led by Li Zicheng

Li Zicheng (22 September 1606 – 1645), born Li Hongji, also known by his nickname, the Thunder King, was a Chinese Late Ming peasant rebellions, peasant rebel leader who helped overthrow the Ming dynasty in April 1644 and ruled over northe ...

captured the Ming capital Beijing in 1644 and founded the short-lived Shun dynasty

The Shun dynasty, officially the Great Shun, also known as Li Shun, was a short-lived Dynasties of China, dynasty of China that existed during the Transition from Ming to Qing, Ming–Qing transition. The dynasty was founded in Xi'an on 8 Februa ...

, but the Ming general Wu Sangui

Wu Sangui (; 8 June 1612 – 2 October 1678), courtesy name Changbai () or Changbo (), was a Chinese military leader who played a key role in the fall of the Ming dynasty and the founding of the Qing dynasty. In Chinese folklore, Wu Sangui is r ...

opened the Shanhai Pass

The Shanhai Pass () is a major fortified gateway at the eastern end of the Great Wall of China and one of its most crucial fortifications, as the pass commands the narrowest choke point in the strategic Liaoxi Corridor, an elongated coasta ...

to the armies of the Qing regent Prince Dorgon

Dorgon (17 November 1612 – 31 December 1650) was a Manchu prince and regent of the early Qing dynasty. Born in the House of Aisin-Gioro as the 14th son of Nurhaci (the founder of the Later Jin dynasty, which was the predecessor of the Qi ...

, who defeated the rebels, seized the capital, and took over the government, although he also implemented the infamous queue decree to force the Han Chinese to adopt the hairstyle. Under the rule of the Shunzhi Emperor

The Shunzhi Emperor (15 March 1638 – 5 February 1661), also known by his temple name Emperor Shizu of Qing, personal name Fulin, was the second Emperor of China, emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the first Qing emperor to rule over China pro ...

, the Qing dynasty conquered most of the territory of the Ming dynasty, chasing loyalist remnants into the southwestern provinces, and establishing the basis of Qing rule over China proper

China proper, also called Inner China, are terms used primarily in the West in reference to the traditional "core" regions of China centered in the southeast. The term was first used by Westerners during the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dyn ...

. The Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 165420 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, personal name Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign of 61 ...

ascended to the throne in 1662, ruling for 61 years until 1722. During is reign, the Qing dynasty entered into an era of prosperity known as the High Qing era. The Revolt of the Three Feudatories

The Revolt of the Three Feudatories, () also known as the Rebellion of Wu Sangui, was a rebellion lasting from 1673 to 1681 in the early Qing dynasty of China, during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661–1722). The revolt was led by Wu San ...

was suppressed under his reign, and various border conflicts were resolved. Succeeding him was the Yongzheng Emperor

The Yongzheng Emperor (13 December 1678 – 8 October 1735), also known by his temple name Emperor Shizong of Qing, personal name Yinzhen, was the fourth List of emperors of the Qing dynasty, emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the third Qing em ...

, who proved to be an able reformer. Under the reign of him and his son, the Qianlong Emperor

The Qianlong Emperor (25 September 17117 February 1799), also known by his temple name Emperor Gaozong of Qing, personal name Hongli, was the fifth Emperor of China, emperor of the Qing dynasty and the fourth Qing emperor to rule over China pr ...

, the Qing military engaged in the Ten Great Campaigns

The Ten Great Campaigns () were a series of military campaigns launched by the Qing dynasty of China in the mid–late 18th century during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796). They included three to enlarge the area of Qing contr ...

on the Chinese frontier. During this period, the Qing dynasty, through its military conquests, reached a territorial extent never seen before in Chinese history.

However, the large size of the Qing empire and its stagnating economy would soon start to take its toll. Corruption began an increasingly widespread issue, as Chinese officials such as Heshen

Heshen (; ; 1 July 1750 – 22 February 1799) of the Manchu Niohuru clan, was an official of the Qing dynasty. Favored by the Qianlong Emperor, he was described as the most corrupt official in Chinese history, having acquired an estimated 1.1 ...

regularly stole tax revenue and public fund

Government spending or expenditure includes all government consumption, investment, and transfer payments. In national income accounting, the acquisition by governments of goods and services for current use, to directly satisfy the individual or ...

s, leading to widespread starvation among the Chinese public. The Jiaqing Emperor

The Jiaqing Emperor (13 November 1760 – 2 September 1820), also known by his temple name Emperor Renzong of Qing, personal name Yongyan, was the sixth emperor of the Qing dynasty and the fifth Qing emperor to rule over China proper. He was ...

attempted to stamp out corruption, and suppressed the White Lotus and Miao Miao may refer to:

* Miao people, linguistically and culturally related group of people, recognized as such by the government of the People's Republic of China

* Miao script or Pollard script, writing system used for Miao languages

* Miao (Unicode ...

rebellions. His successor, the Daoguang Emperor

The Daoguang Emperor (16 September 1782 – 26 February 1850), also known by his temple name Emperor Xuanzong of Qing, personal name Mianning, was the seventh List of emperors of the Qing dynasty, emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the sixth Qing e ...

, attempted to suppress the opium trade in China, which brought the Qing dynasty into conflict with the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

in the First Opium War

The First Opium War ( zh, t=第一次鴉片戰爭, p=Dìyīcì yāpiàn zhànzhēng), also known as the Anglo-Chinese War, was a series of military engagements fought between the British Empire and the Chinese Qing dynasty between 1839 and 1 ...

. The war resulted in a Chinese defeat and the Treaty of Nanjing, an "unequal treaty

The unequal treaties were a series of agreements made between Asian countries—most notably Qing dynasty, Qing China, Tokugawa shogunate, Tokugawa Japan and Joseon, Joseon Korea—and Western countries—most notably the United Kingdom of Great ...

" which ceded Hong Kong Island

Hong Kong Island () is an island in the southern part of Hong Kong. The island, known originally and on road signs simply as "Hong Kong", had a population of 1,289,500 and a population density of , . It is the second largest island in Hong Kon ...

to the British and opened several ports to foreign trade. In 1856, further tensions between the Qing dynasty and foreign powers led to the outbreak of the Second Opium War

The Second Opium War (), also known as the Second Anglo-Chinese War or ''Arrow'' War, was fought between the United Kingdom, France, Russia, and the United States against the Qing dynasty of China between 1856 and 1860. It was the second major ...

, which resulted in further "unequal treaties" being signed by the Chinese government

The government of the People's Republic of China is based on a system of people's congress within the parameters of a Unitary state, unitary communist state, in which the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) enacts its policies through people's ...

. Amidst a backdrop of rising economic issues, sectarian tension and foreign interventions, the Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion, also known as the Taiping Civil War or the Taiping Revolution, was a civil war in China between the Qing dynasty and the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. The conflict lasted 14 years, from its outbreak in 1850 until the fall of ...

broke out in 1850. Led by Christian revolutionary Hong Xiuquan

Hong Xiuquan (1 January 1814 – 1 June 1864), born Hong Huoxiu and with the courtesy name Renkun, was a Chinese revolutionary and religious leader who led the Taiping Rebellion against the Qing dynasty. He established the Taiping Heavenly K ...

, the rebels established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, or the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace (1851–1864), was a theocratic monarchy which sought to overthrow the Qing dynasty. The Heavenly Kingdom, or Heavenly Dynasty, was led by Hong Xiuquan, a Hakka man from Guan ...

. The rebellion ultimately became one of the bloodiest conflicts in history, killing roughly 20 to 30 million people, and proved to be a pyrrhic victory at best for the Qing dynasty, as it would collapse less than 50 years after the rebellion. The rebellion resulted in increased sectarian tension and accelerated regionalism, in what would prove to be a foreshadowing of the Warlord Era that would come after the fall of the Qing.

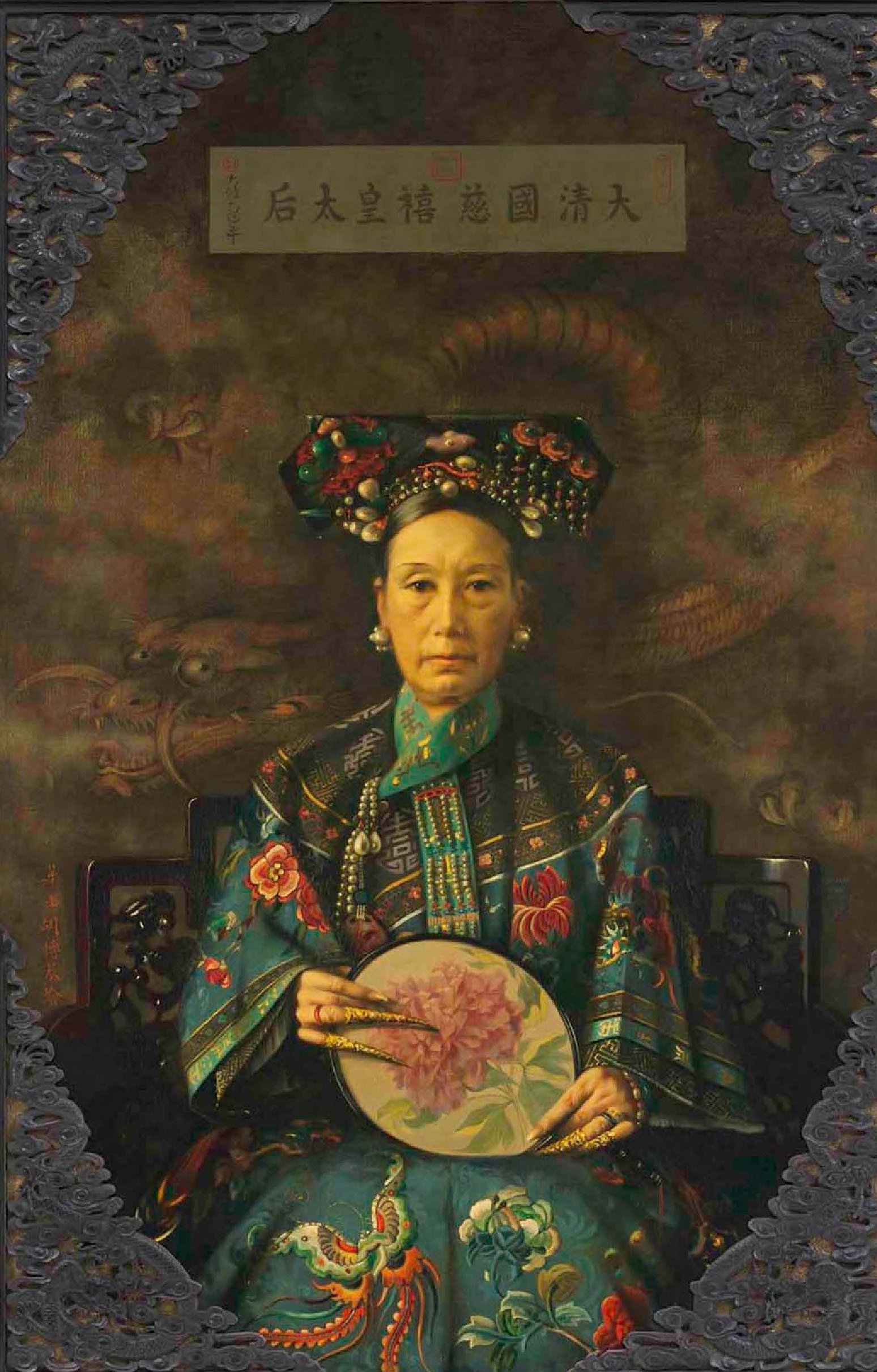

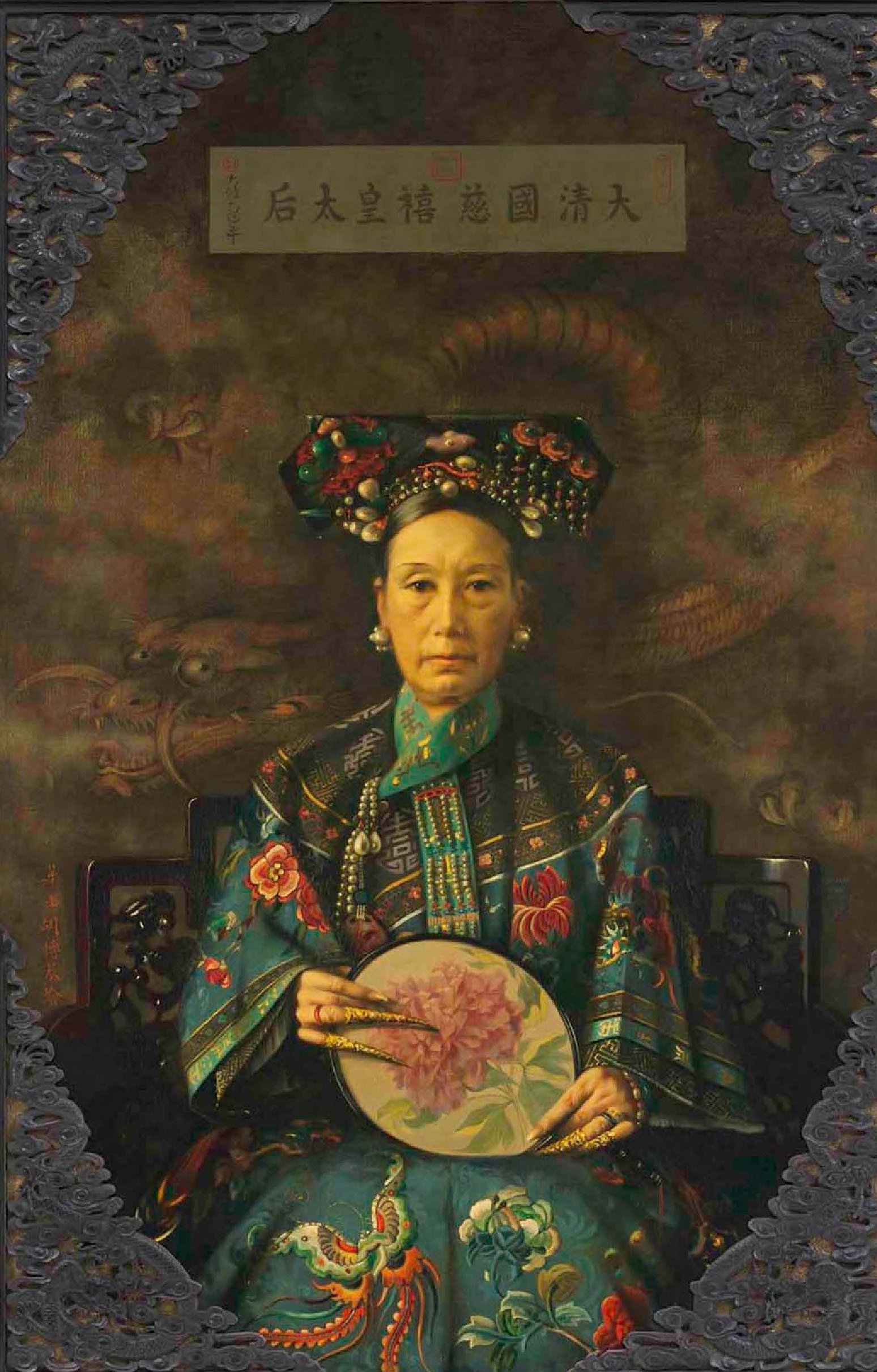

Despite these issues, the Qing dynasty carried on after the rebellion, with Empress Dowager Cixi

Empress Dowager Cixi ( ; 29 November 1835 – 15 November 1908) was a Manchu noblewoman of the Yehe Nara clan who effectively but periodically controlled the Chinese government in the late Qing dynasty as empress dowager and regent for almost 50 ...

as its effective head from 1861 to 1908. She was a moderate reformer, overseeing the Tongzhi Restoration

The Tongzhi Restoration (; c. 1860–1874) was an attempt to arrest the dynastic decline of the Qing dynasty by restoring the traditional order. The harsh realities of the Opium Wars, the unequal treaties, and the mid-century mass uprisings of t ...

. The turn of the century Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious F ...

exemplified popular discontent, and led to an international coalition invading China to protect foreign citizens and interests. Cixi sided with the rebels, and was dealt a decisive defeat by the combined forces of the coalition. Cixi's death in 1908 left the country in deep trouble and without an effective leader. The emperor, Puyi, was a toddler, and the control of his regency was fiercely contested. Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 18596 June 1916) was a Chinese general and statesman who served as the second provisional president and the first official president of the Republic of China, head of the Beiyang government from 1912 to 1916 and ...

maneuvered himself into power as president of an ineffectual Republic, and forced the abdication of Puyi, the last emperor, in 1912. This brought an end to the Qing dynasty, and over 2,000 years of imperial rule in China. Shikai briefly ruled as a dictator, but proved incapable of ruling all China, and the country splintered apart, not to be fully reunited until 1928 under Chiang Kai-shek. A brief and ineffective restoration of the dynasty occurred in 1917 with Puyi at its head, emblematic of the chaotic and inconclusive conflicts that would wrack China until Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

rule.

Formation of the Manchu state

Overview

The Qing dynasty was founded not byHan Chinese

The Han Chinese, alternatively the Han people, are an East Asian people, East Asian ethnic group native to Greater China. With a global population of over 1.4 billion, the Han Chinese are the list of contemporary ethnic groups, world's la ...

, who constitute the majority of the Chinese population, but by the Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic peoples, Tungusic East Asian people, East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized Ethnic minorities in China, ethnic minority in China and the people from wh ...

, descendants of a sedentary farming people known as the Jurchen, a Tungusic people who lived around the region now comprising the Chinese provinces of Jilin

)

, image_skyline = Changbaishan Tianchi from western rim.jpg

, image_alt =

, image_caption = View of Heaven Lake

, image_map = Jilin in China (+all claims hatched).svg

, mapsize = 275px

, map_al ...

and Heilongjiang

Heilongjiang is a province in northeast China. It is the northernmost and easternmost province of the country and contains China's northernmost point (in Mohe City along the Amur) and easternmost point (at the confluence of the Amur and Us ...

. The Manchus are sometimes mistaken for a nomad

Nomads are communities without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the population of nomadic pa ...

ic people, which they were not. Early European writers had used the term "Tartar" indiscriminately for all the peoples of Northern Eurasia but in the 17th century Catholic missionary writings established "Tartar" to refer only to the Manchus and "Tartary

Tartary (Latin: ''Tartaria''; ; ; ) or Tatary () was a blanket term used in Western European literature and cartography for a vast part of Asia bounded by the Caspian Sea, the Ural Mountains, the Pacific Ocean, and the northern borders of China, ...

" for the lands they ruled, that is, Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

and adjacent parts of Inner Asia

Inner Asia refers to the northern and landlocked regions spanning North Asia, North, Central Asia, Central, and East Asia. It includes parts of Western China, western and northeast China, as well as southern Siberia. The area overlaps with some d ...

as ruled by the Qing before the Ming-Qing transition (see also Chinese Tartary

Chinese Tartary ( zh, t=中國韃靼利亞, p=Zhōngguó Dádálìyà or zh, t=中属鞑靼利亚, p=Zhōng shǔ Dádálìyà) is an archaic geographical term referring to the regions of Manchuria, Mongolia, Xinjiang (also referred to as Chin ...

).

Nurhaci

What was to become the Manchu state was founded byNurhaci

Nurhaci (14 May 1559 – 30 September 1626), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Taizu of Qing, was the founding khan of the Jurchen people, Jurchen-led Later Jin (1616–1636), Later Jin dynasty.

As the leader of the House of Aisin-Gi ...

, the chieftain of a minor Jurchen tribethe Aisin Gioro

The House of Aisin-Gioro is a Manchu clan that ruled the Later Jin dynasty (1616–1636), the Qing dynasty (1636–1912), and Manchukuo (1932–1945) in the history of China. Under the Ming dynasty, members of the Aisin Gioro clan served as chie ...

in Jianzhou in the early 17th century. Nurhaci may have spent time in a Chinese household in his youth, and became fluent in Chinese as well as Mongol, and read the Chinese novels Romance of the Three Kingdoms

''Romance of the Three Kingdoms'' () is a 14th-century historical novel attributed to Luo Guanzhong. It is set in the turbulent years towards the end of the Han dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period in Chinese history, starting in 184 AD and ...

and Water Margin

''Water Margin'' (), also called ''Outlaws of the Marsh'' or ''All Men Are Brothers'', is a Chinese novel from the Ming dynasty that is one of the preeminent Classic Chinese Novels. Attributed to Shi Nai'an, ''Water Margin'' was one of the e ...

. As a vassal of the Ming emperors who officially considered himself a guardian of the Ming border and a local representative of imperial power of the Ming dynasty, Nurhaci embarked on an intertribal feud in 1582 that escalated into a campaign to unify the nearby tribes. By 1616, however, he had sufficiently consolidated Jianzhou so as to be able to proclaim himself Khan of the Great Jin in reference to the previous Jurchen Jin dynasty.

Two years later, Nurhaci announced the "

Two years later, Nurhaci announced the "Seven Grievances

The ''Seven Grievances'' (Manchu: ''nadan koro''; ) was a manifesto announced by Nurhaci, khan of the Later Jin, on the thirteenth day of the fourth lunar month in the third year of the ''Tianming'' () era of his reign; 7 May 1618. It effecti ...

" and openly renounced the sovereignty of Ming overlordship in order to complete the unification of those Jurchen tribes still allied with the Ming emperor. After a series of successful battles, he relocated his capital from Hetu Ala to successively bigger captured Ming cities in Liaodong: first Liaoyang

Liaoyang ( zh, s=辽阳 , t=遼陽 , p=Liáoyáng) is a prefecture-level city of east-central Liaoning province, China, situated on the Taizi River. It is approximately one hour south of Shenyang, the provincial capital, by car. Liaoyang is hom ...

in 1621, then Shenyang

Shenyang,; ; Mandarin pronunciation: ; formerly known as Fengtian formerly known by its Manchu language, Manchu name Mukden, is a sub-provincial city in China and the list of capitals in China#Province capitals, provincial capital of Liaonin ...

(Manchu: Mukden) in 1625.

When the Jurchens were reorganized by Nurhaci into the Eight Banners, many Manchu clans were artificially created as a group of unrelated people founded a new Manchu clan (Manchu: ''mukūn'') using a geographic origin name such as a toponym for their ''hala'' (clan name). The irregularities over Jurchen and Manchu clan origin led the Qing to document and systematize the creation of histories for Manchu clans, including manufacturing an entire legend around the origin of the Aisin Gioro clan by taking mythology from the northeast.

Relocating his court from Jianzhou to Liaodong provided Nurhaci access to more resources; it also brought him in close contact with the Khorchin Mongol domains on the plains of Mongolia. Although by this time the once-united Mongol nation had long since fragmented into individual and hostile tribes, these tribes still presented a serious security threat to the Ming borders. Nurhaci's policy towards the Khorchins was to seek their friendship and cooperation against the Ming, securing his western border from a powerful potential enemy.Bernard Hung-Kay Luk, Amir Harrak-Contacts between cultures, Volume 4, p.25

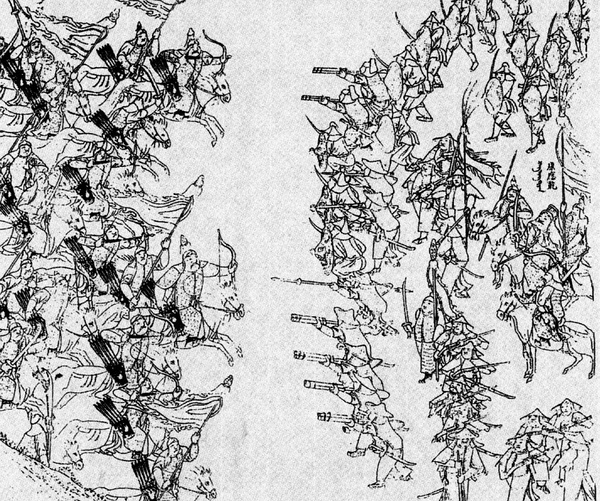

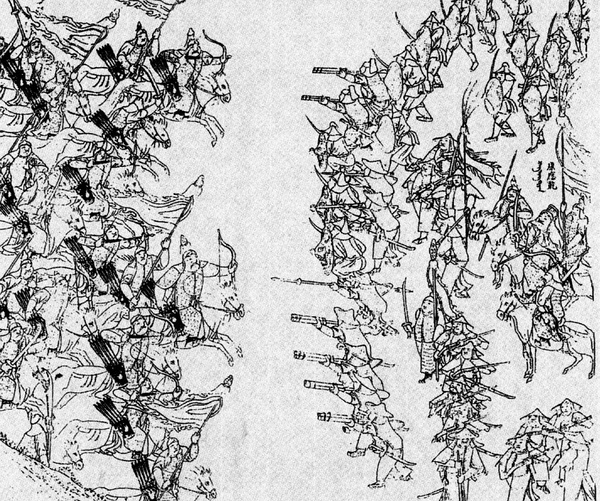

Furthermore, the Khorchin proved a useful ally in the war, lending the Jurchens their expertise as cavalry archers. To guarantee this new alliance, Nurhaci initiated a policy of inter-marriages between the Jurchen and Khorchin nobilities, while those who resisted were met with military action. This is a typical example of Nurhaci's initiatives that eventually became official Qing government policy. During most of the Qing period, the Mongols gave military assistance to the Manchus.

Some other important contributions by Nurhaci include ordering the creation of a written Manchu script, based on

Some other important contributions by Nurhaci include ordering the creation of a written Manchu script, based on Mongolian script

The traditional Mongolian script, also known as the Hudum Mongol bichig, was the first Mongolian alphabet, writing system created specifically for the Mongolian language, and was the most widespread until the introduction of Cyrillic script, Cy ...

, after the earlier Jurchen script

The Jurchen script (Jurchen: ; ) was the writing system used to write the Jurchen language, the language of the Jurchen people who created the Jin Empire in northeastern China in the 12th–13th centuries. It was derived from the Khitan scrip ...

was forgotten (it had been derived from Khitan and Chinese). Nurhaci also created the civil and military administrative system that eventually evolved into the Eight Banners

The Eight Banners (in Manchu language, Manchu: ''jakūn gūsa'', , ) were administrative and military divisions under the Later Jin (1616–1636), Later Jin and Qing dynasty, Qing dynasties of China into which all Manchu people, Manchu househol ...

, the defining element of Manchu identity and the foundation for transforming the loosely-knitted Jurchen tribes into a single nation.

There were too few ethnic Manchus to conquer China proper

China proper, also called Inner China, are terms used primarily in the West in reference to the traditional "core" regions of China centered in the southeast. The term was first used by Westerners during the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dyn ...

, so they gained strength by defeating and absorbing Mongols. More importantly, they added Han Chinese to the Eight Banners. The Manchus had to create an entire "Jiu Han jun" (Old Han Army) due to the massive number of Han Chinese soldiers who were absorbed into the Eight Banners by both capture and defection. Ming artillery was responsible for many victories against the Manchus, so the Manchus established an artillery corps made out of Han Chinese soldiers in 1641, and the swelling of Han Chinese numbers in the Eight Banners led in 1642 to all Eight Han Banners being created. Armies of defected Ming Han Chinese conquered southern China for the Qing.

Han Chinese played a massive role in the Qing conquest of China proper. Han Chinese Generals who defected to the Manchu were often given women from the Imperial Aisin Gioro family in marriage while the ordinary soldiers who surrendered were often given non-royal Manchu women as wives. Jurchen (Manchu) women married Han Chinese in Liaodong. Manchu Aisin Gioro princesses were also given in marriage to Han Chinese officials' sons.

Hong Taiji

The unbroken series of Nurhaci's military successes ended in January 1626 when he was defeated byYuan Chonghuan

Yuan Chonghuan (; 6 June 1584 – 22 September 1630), courtesy name Yuansu, art name Ziru, was a Chinese politician, military general and writer who served under the Ming dynasty. Remembered as a national hero of Ming China and widely regarded ...

while laying siege to Ningyuan. He died a few months later and was succeeded by his eighth son, Hong Taiji

Hong Taiji (28 November 1592 – 21 September 1643), also rendered as Huang Taiji and sometimes referred to as Abahai in Western literature, also known by his temple name as the Emperor Taizong of Qing, was the second khan of the Later Jin ...

, who emerged as the new Khan after a short political struggle amongst other contenders . Although Hong Taiji was an experienced leader and the commander of two Banners at the time of his succession, his reign did not start well on the military front. The Jurchens suffered yet another defeat in 1627 at the hands of Yuan Chonghuan. This defeat was also in part due to the Ming's newly acquired Portuguese cannons.

To redress the technological and numerical disparity, Hong Taiji created his own artillery corps in 1634, the ''ujen cooha'' (Chinese: ) from his existing Han troops who cast their own cannons in the European design with the help of defector Chinese metallurgists. One of the defining events of Hong Taiji's reign was the official adoption of the name "Manchu" for the united Jurchen people in November 1635. In 1635, the Manchus' Mongol allies were fully incorporated into a separate Banner hierarchy under direct Manchu command. Hong Taiji conquered the territory north of

To redress the technological and numerical disparity, Hong Taiji created his own artillery corps in 1634, the ''ujen cooha'' (Chinese: ) from his existing Han troops who cast their own cannons in the European design with the help of defector Chinese metallurgists. One of the defining events of Hong Taiji's reign was the official adoption of the name "Manchu" for the united Jurchen people in November 1635. In 1635, the Manchus' Mongol allies were fully incorporated into a separate Banner hierarchy under direct Manchu command. Hong Taiji conquered the territory north of Shanhai Pass

The Shanhai Pass () is a major fortified gateway at the eastern end of the Great Wall of China and one of its most crucial fortifications, as the pass commands the narrowest choke point in the strategic Liaoxi Corridor, an elongated coasta ...

by Ming dynasty and Ligdan Khan

Khutugtu Khan (; ), born Ligdan (; ), (1588–1634) was a khagan of the Northern Yuan dynasty, reigning from 1604 to 1634. During his reign, he vigorously attempted to reunify the divided Mongol Empire, achieving moderate levels of success. Howev ...

in Inner Mongolia. In April 1636, Mongol nobility of Inner Mongolia, Manchu nobility and the Han mandarin held the Kurultai

A kurultai (, ),Derived from Russian language, Russian , ultimately from Middle Mongol ( ), whence Chinese language, Chinese 忽里勒台 ''Hūlǐlēitái'' (); ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; (). also called a qurultai, was a political and military counc ...

in Shenyang, and recommended the khan of Later Jin to be the emperor of the Great Qing empire. One of the Yuan Dynasty's jade seal was also dedicated to the emperor (Bogd Setsen Khan) by the nobility. When he was presented with the imperial seal of the Yuan dynasty after the defeat of the last Khagan

Khagan or Qaghan (Middle Mongol:; or ''Khagan''; ) or zh, c=大汗, p=Dàhán; ''Khāqān'', alternatively spelled Kağan, Kagan, Khaghan, Kaghan, Khakan, Khakhan, Khaqan, Xagahn, Qaghan, Chagan, Қан, or Kha'an is a title of empire, im ...

of the Mongols, Hong Taiji renamed his state from "Great Jin" to "Great Qing" and elevated his position from Khan to Emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

, suggesting imperial ambitions beyond unifying the Manchu territories. Hong Taiji then proceeded to invade Korea again in 1636.

The change of name from Jurchen to Manchu was made to hide the fact that the ancestors of the Manchus, the Jianzhou Jurchens, were ruled by the Chinese. The Qing dynasty carefully hid the original editions of the books of "''Qing Taizu Wu Huangdi Shilu''" and the "''Manzhou Shilu Tu''" (Taizu Shilu Tu) in the Qing palace, forbidden from public view because they showed that the Manchu Aisin Gioro family had been ruled by the Ming dynasty and followed many Manchu customs that seemed "uncivilized" to later observers. The Qing also deliberately excluded references and information that showed the Jurchens (Manchus) as subservient to the Ming dynasty, from the History of Ming

The ''History of Ming'' is the final official Chinese history included in the '' Twenty-Four Histories''. It consists of 332 volumes and covers the history of the Ming dynasty from 1368 to 1644. It was written by a number of officials commissio ...

to hide their former subservient relationship to the Ming. The Veritable Records of Ming were not used to source content on Jurchens during Ming rule in the History of Ming because of this.

In the Ming period, the Koreans of Joseon

Joseon ( ; ; also romanized as ''Chosun''), officially Great Joseon (), was a dynastic kingdom of Korea that existed for 505 years. It was founded by Taejo of Joseon in July 1392 and replaced by the Korean Empire in October 1897. The kingdom w ...

referred to the Jurchen-inhabited lands north of the Korean peninsula, above the rivers Yalu and Tumen to be part of Ming China, as the "superior country" (sangguk) which they called Ming China. After the Second Manchu invasion of Korea

The Qing invasion of Joseon () occurred in the winter of 1636 when the newly established Qing dynasty invaded the Joseon dynasty, establishing the former's status as the hegemon in the Imperial Chinese Tributary System and formally severing Jo ...

, Joseon Korea was forced to give several of their royal princesses as concubines to the Qing Manchu regent Prince Dorgon

Dorgon (17 November 1612 – 31 December 1650) was a Manchu prince and regent of the early Qing dynasty. Born in the House of Aisin-Gioro as the 14th son of Nurhaci (the founder of the Later Jin dynasty, which was the predecessor of the Qi ...

. In 1650, Dorgon married the Korean Princess Uisun.

This was followed by the creation of the first two Han Banners in 1637 (increasing to eight in 1642). Together these military reforms enabled Hong Taiji to resoundingly defeat Ming forces in a series of battles from 1640 to 1642 for the territories of Songshan and Jinzhou

Jinzhou (, zh, s= , t=錦州 , p=Jǐnzhōu), formerly Chinchow, is a coastal prefecture-level city in central-west Liaoning province, China. It is a geographically strategic city located in the Liaoxi Corridor, which connects most of the la ...

. This final victory resulted in the surrender of many of the Ming dynasty's most battle-hardened troops, the death of Yuan Chonghuan at the hands of the Chongzhen Emperor

The Chongzhen Emperor (6 February 1611 – 25 April 1644), personal name Zhu Youjian, courtesy name Deyue,Wang Yuan (王源),''Ju ye tang wen ji'' (《居業堂文集》), vol. 19. "聞之張景蔚親見烈皇帝神主題御諱字德約,行� ...

(who thought Yuan had betrayed him), and the complete and permanent withdrawal of the remaining Ming forces north of the Great Wall

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand Li (unit), ''li'' long wall") is a series of fortifications in China. They were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection agains ...

.

Meanwhile, Hong Taiji set up a rudimentary bureaucratic system based on the Ming model. He established six boards or executive level ministries in 1631 to oversee finance, personnel, rites, military, punishments, and public works. However, these administrative organs had very little role initially, and it was not until the eve of completing the conquest ten years later that they fulfilled their government roles.

Hong Taiji's bureaucracy was staffed with many Han Chinese, including many newly surrendered Ming officials. The Manchus' continued dominance was ensured by an ethnic quota for top bureaucratic appointments. Hong Taiji's reign also saw a fundamental change of policy towards his Han Chinese subjects. Nurhaci had treated Han in Liaodong differently according to how much grain they had: those with less than 5 to 7 sin were treated badly, while those with more than that amount were rewarded with property. Due to a revolt by Han in Liaodong in 1623, Nurhaci, who previously gave concessions to conquered Han subjects in Liaodong, turned against them and ordered that they no longer be trusted. He enacted discriminatory policies and killings against them, while ordering that Han who assimilated to the Jurchen (in Jilin) before 1619 be treated equally, as Jurchens were, and not like the conquered Han in Liaodong. Hong Taiji recognized that the Manchus needed to attract Han Chinese, explaining to reluctant Manchus why he needed to treat the Ming defector General

Meanwhile, Hong Taiji set up a rudimentary bureaucratic system based on the Ming model. He established six boards or executive level ministries in 1631 to oversee finance, personnel, rites, military, punishments, and public works. However, these administrative organs had very little role initially, and it was not until the eve of completing the conquest ten years later that they fulfilled their government roles.

Hong Taiji's bureaucracy was staffed with many Han Chinese, including many newly surrendered Ming officials. The Manchus' continued dominance was ensured by an ethnic quota for top bureaucratic appointments. Hong Taiji's reign also saw a fundamental change of policy towards his Han Chinese subjects. Nurhaci had treated Han in Liaodong differently according to how much grain they had: those with less than 5 to 7 sin were treated badly, while those with more than that amount were rewarded with property. Due to a revolt by Han in Liaodong in 1623, Nurhaci, who previously gave concessions to conquered Han subjects in Liaodong, turned against them and ordered that they no longer be trusted. He enacted discriminatory policies and killings against them, while ordering that Han who assimilated to the Jurchen (in Jilin) before 1619 be treated equally, as Jurchens were, and not like the conquered Han in Liaodong. Hong Taiji recognized that the Manchus needed to attract Han Chinese, explaining to reluctant Manchus why he needed to treat the Ming defector General Hong Chengchou

Hong Chengchou (; 1593–1665), courtesy name Yanyan and art name Hengjiu, was a Chinese official who served under the Ming and Qing dynasties. He was born in present-day Liangshan Village, Yingdu Town, Fujian Province, China. After obtaining ...

leniently. Hong Taiji instead incorporated them into the Jurchen "nation" as full (if not first-class) citizens, obligated to provide military service. By 1648, less than one-sixth of the bannermen were of Manchu ancestry. This change of policy not only increased Hong Taiji's manpower and reduced his military dependence on banners not under his personal control, it also greatly encouraged other Han Chinese subjects of the Ming dynasty to surrender and accept Jurchen rule when they were defeated militarily. Through these and other measures Hong Taiji was able to centralize power unto the office of the Khan, which in the long run prevented the Jurchen federation from fragmenting after his death.

Claiming the Mandate of Heaven

Hong Taiji died suddenly in September 1643. As the Jurchens had traditionally "elected" their leader through a council of nobles, the Qing state did not have a clear succession system. The leading contenders for power were Hong Taiji's oldest son Hooge and Hong Taiji's half brotherDorgon

Dorgon (17 November 1612 – 31 December 1650) was a Manchu prince and regent of the early Qing dynasty. Born in the House of Aisin-Gioro as the 14th son of Nurhaci (the founder of the Later Jin dynasty, which was the predecessor of the Qi ...

. A compromise installed Hong Taiji's five-year-old son, Fulin, as the Shunzhi Emperor

The Shunzhi Emperor (15 March 1638 – 5 February 1661), also known by his temple name Emperor Shizu of Qing, personal name Fulin, was the second Emperor of China, emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the first Qing emperor to rule over China pro ...

, with Dorgon as regent and de facto leader of the Manchu nation.

Meanwhile, Ming government officials fought against each other, against fiscal collapse, and against a series of peasant rebellions. They were unable to capitalise on the Manchu succession dispute and the presence of a minor as emperor. In April 1644, the capital, Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

, was sacked by a coalition of rebel forces led by Li Zicheng

Li Zicheng (22 September 1606 – 1645), born Li Hongji, also known by his nickname, the Thunder King, was a Chinese Late Ming peasant rebellions, peasant rebel leader who helped overthrow the Ming dynasty in April 1644 and ruled over northe ...

, a former minor Ming official, who established a short-lived Shun dynasty

The Shun dynasty, officially the Great Shun, also known as Li Shun, was a short-lived Dynasties of China, dynasty of China that existed during the Transition from Ming to Qing, Ming–Qing transition. The dynasty was founded in Xi'an on 8 Februa ...

. The last Ming ruler, the Chongzhen Emperor

The Chongzhen Emperor (6 February 1611 – 25 April 1644), personal name Zhu Youjian, courtesy name Deyue,Wang Yuan (王源),''Ju ye tang wen ji'' (《居業堂文集》), vol. 19. "聞之張景蔚親見烈皇帝神主題御諱字德約,行� ...

, committed suicide when the city fell to the rebels, marking the official end of the dynasty.

Li Zicheng then led a collection of rebel forces numbering some 200,000 to confront Wu Sangui

Wu Sangui (; 8 June 1612 – 2 October 1678), courtesy name Changbai () or Changbo (), was a Chinese military leader who played a key role in the fall of the Ming dynasty and the founding of the Qing dynasty. In Chinese folklore, Wu Sangui is r ...

, the general commanding the Ming garrison at Shanhai Pass

The Shanhai Pass () is a major fortified gateway at the eastern end of the Great Wall of China and one of its most crucial fortifications, as the pass commands the narrowest choke point in the strategic Liaoxi Corridor, an elongated coasta ...

, a key pass of the Great Wall

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand Li (unit), ''li'' long wall") is a series of fortifications in China. They were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection agains ...

, located northeast of Beijing, which defended the capital. Wu Sangui, caught between a rebel army twice his size and an enemy he had fought for years, cast his lot with the foreign but familiar Manchus. Wu Sangui may have been influenced by Li Zicheng's mistreatment of wealthy and cultured officials, including Li's own family; it was said that Li took Wu's concubine Chen Yuanyuan

Chen Yuanyuan (c. 1623–1689 or 1695) was a Chinese courtesan who later became the concubine of military leader Wu Sangui. In Chinese folklore, the Shun army's capture of her in 1644 prompted Wu's fateful decision to let the Qing armies en ...

for himself. Wu and Dorgon allied in the name of avenging the death of the Chongzhen Emperor

The Chongzhen Emperor (6 February 1611 – 25 April 1644), personal name Zhu Youjian, courtesy name Deyue,Wang Yuan (王源),''Ju ye tang wen ji'' (《居業堂文集》), vol. 19. "聞之張景蔚親見烈皇帝神主題御諱字德約,行� ...

. Together, the two former enemies met and defeated Li Zicheng's rebel forces in battle on May 27, 1644.

The newly allied armies captured Beijing on 6 June. The Shunzhi Emperor

The Shunzhi Emperor (15 March 1638 – 5 February 1661), also known by his temple name Emperor Shizu of Qing, personal name Fulin, was the second Emperor of China, emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the first Qing emperor to rule over China pro ...

was invested as the "Son of Heaven

Son of Heaven, or ''Tianzi'' (), was the sacred monarchial and imperial title of the Chinese sovereign. It originated with the Zhou dynasty and was founded on the political and spiritual doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven. Since the Qin dynasty ...

" on 30 October. The Manchus, who had positioned themselves as political heirs to the Ming emperor by defeating Li Zicheng, completed the symbolic transition by holding a formal funeral for the Chongzhen Emperor. However, conquering the rest of China Proper took another seventeen years of battling Ming loyalists, pretender

A pretender is someone who claims to be the rightful ruler of a country although not recognized as such by the current government. The term may often be used to either refer to a descendant of a deposed monarchy or a claim that is not legitimat ...

s and rebels. The last Ming pretender, Prince Gui, sought refuge with the King of Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

, Pindale Min, but was turned over to a Qing expeditionary army commanded by Wu Sangui, who had him brought back to Yunnan

Yunnan; is an inland Provinces of China, province in Southwestern China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 47.2 million (as of 2020). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the Chinese provinces ...

province and executed in early 1662.

The Qing had taken shrewd advantage of Ming civilian government discrimination against the military and encouraged the Ming military to defect by spreading the message that the Manchus valued their skills. Banners made up of Han Chinese who defected before 1644 were classed among the Eight Banners, giving them social and legal privileges in addition to being acculturated to Manchu traditions. Han defectors swelled the ranks of the Eight Banners so greatly that ethnic Manchus became a minority—only 16% in 1648, with Han Bannermen dominating at 75% and Mongol Bannermen making up the rest. Gunpowder weapons like muskets and artillery were wielded by the Chinese Banners. Normally, Han Chinese defector troops were deployed as the vanguard, while Manchu Bannermen acted as reserve forces or in the rear and were used predominantly for quick strikes with maximum impact, so as to minimize ethnic Manchu losses.

This multi-ethnic Qing force conquered China proper

China proper, also called Inner China, are terms used primarily in the West in reference to the traditional "core" regions of China centered in the southeast. The term was first used by Westerners during the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dyn ...

, and the three Liaodong Han Bannermen officers who played key roles in the conquest of southern China were Shang Kexi, Geng Zhongming, and Kong Youde, who governed southern China autonomously as viceroys for the Qing after the conquest. Han Chinese Bannermen made up the majority of governors in the early Qing, and they governed and administered China after the conquest, stabilizing Qing rule. Han Bannermen dominated the post of governor-general in the time of the Shunzhi and Kangxi Emperors, and also the post of governor, largely excluding ordinary Han civilians from these posts.

To promote ethnic harmony, a 1648 decree allowed Han Chinese civilian men to marry Manchu women from the Banners with the permission of the Board of Revenue if they were registered daughters of officials or commoners, or with the permission of their banner company captain if they were unregistered commoners. Later in the dynasty the policies allowing intermarriage were done away with.

The southern cadet branch of Confucius

Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ...

' descendants who held the title ''Wujing boshi'' (Doctor of the Five Classics) and 65th generation descendant in the northern branch who held the title Duke Yansheng

The Duke Yansheng, literally "Honorable Overflowing with Wisdom", sometimes translated as Holy Duke of Yen, was a Chinese title of nobility. It was originally created as a marquis title in the Western Han dynasty for a direct descendant ...

both had their titles confirmed by the Shunzhi Emperor upon the Qing entry into Beijing on 31 October. The Kong's title of Duke was maintained in later reigns.

The first seven years of the Shunzhi Emperor's reign were dominated by the regent prince Dorgon. Because of his own political insecurity, Dorgon followed Hong Taiji's example by ruling in the name of the emperor at the expense of rival Manchu princes, many of whom he demoted or imprisoned under one pretext or another. Although the period of his regency was relatively short, Dorgon's precedents and example cast a long shadow over the dynasty.

First, the Manchus had entered "South of the Wall" because Dorgon responded decisively to Wu Sangui's appeal. Then, after capturing Beijing, instead of sacking the city as the rebels had done, Dorgon insisted, over the protests of other Manchu princes, on making it the dynastic capital and reappointing most Ming officials. Choosing Beijing as the capital had not been a straightforward decision, since no major Chinese dynasty had directly taken over its immediate predecessor's capital. Keeping the Ming capital and bureaucracy intact helped quickly stabilize the regime and sped up the conquest of the rest of the country. Dorgon then drastically reduced the influence of the eunuchs, a major force in the Ming bureaucracy, and directed Manchu women not to bind their feet in the Chinese style.

However, not all of Dorgon's policies were equally popular or as easy to implement. The controversial July 1645 edict (the "haircutting order") forced adult Han Chinese men to shave the front of their heads and comb the remaining hair into the queue hairstyle which was worn by Manchu men, on pain of death. The popular description of the order was: "To keep the hair, you lose the head; To keep your head, you cut the hair." To the Manchus, this policy was a test of loyalty and an aid in distinguishing friend from foe. For the Han Chinese, however, it was a humiliating reminder of Qing authority that challenged traditional Confucian values. The ''

The first seven years of the Shunzhi Emperor's reign were dominated by the regent prince Dorgon. Because of his own political insecurity, Dorgon followed Hong Taiji's example by ruling in the name of the emperor at the expense of rival Manchu princes, many of whom he demoted or imprisoned under one pretext or another. Although the period of his regency was relatively short, Dorgon's precedents and example cast a long shadow over the dynasty.

First, the Manchus had entered "South of the Wall" because Dorgon responded decisively to Wu Sangui's appeal. Then, after capturing Beijing, instead of sacking the city as the rebels had done, Dorgon insisted, over the protests of other Manchu princes, on making it the dynastic capital and reappointing most Ming officials. Choosing Beijing as the capital had not been a straightforward decision, since no major Chinese dynasty had directly taken over its immediate predecessor's capital. Keeping the Ming capital and bureaucracy intact helped quickly stabilize the regime and sped up the conquest of the rest of the country. Dorgon then drastically reduced the influence of the eunuchs, a major force in the Ming bureaucracy, and directed Manchu women not to bind their feet in the Chinese style.

However, not all of Dorgon's policies were equally popular or as easy to implement. The controversial July 1645 edict (the "haircutting order") forced adult Han Chinese men to shave the front of their heads and comb the remaining hair into the queue hairstyle which was worn by Manchu men, on pain of death. The popular description of the order was: "To keep the hair, you lose the head; To keep your head, you cut the hair." To the Manchus, this policy was a test of loyalty and an aid in distinguishing friend from foe. For the Han Chinese, however, it was a humiliating reminder of Qing authority that challenged traditional Confucian values. The ''Classic of Filial Piety

The ''Classic of Filial Piety'', also known by its Chinese name as the ''Xiaojing'', is a Confucian classic treatise giving advice on filial piety: that is, how to behave towards a senior such as a father, an elder brother, or a ruler.

The ...

'' (''Xiaojing'') held that "a person's body and hair, being gifts from one's parents, are not to be damaged". Under the Ming dynasty, adult men did not cut their hair but instead wore it in the form of a top-knot. The order triggered strong resistance to Qing rule in Jiangnan

Jiangnan is a geographic area in China referring to lands immediately to the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, including the southern part of its delta. The region encompasses the city of Shanghai, the southern part of Jiangsu ...

and massive killing of Han Chinese. It was Han Chinese defectors who carried out massacres against people refusing to wear the queue. Li Chengdong, a Han Chinese general who had served the Ming but surrendered to the Qing, ordered his Han troops to carry out three separate massacres in the city of Jiading within a month, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths. At the end of the third massacre, there was hardly a living person left in this city. Jiangyin

Jiangyin (, Jiangyin dialect: ) is a county-level city on the southern bank of the Yangtze River. It is administered by the Wuxi, Jiangsu province. Jiangyin is an important transport hub on the Yangtze River and one of the most developed counties ...

also held out against about 10,000 Han Chinese Qing troops for 83 days. When the city wall was finally breached on 9 October 1645, the Han Chinese Qing army led by the Han Chinese Ming defector Liu Liangzuo

Liu (; or ) is an East Asian surname. pinyin: in Mandarin Chinese, in Cantonese. It is the family name of the Han dynasty emperors. The character originally meant 'battle axe', but is now used only as a surname. It is listed 252nd in the clas ...

(劉良佐), who had been ordered to "fill the city with corpses before you sheathe your swords", massacred the entire population, killing between 74,000 and 100,000 people.

Han Chinese did not object to wearing the queue braid on the back of the head, as they traditionally wore all their hair long, but fiercely objected to shaving the forehead, which the Qing government focused on. Han rebels in the first half of the Qing wore the braid but defied orders to shave the front of the head. One person was executed for refusing to shave the front but he had willingly braided the back of his hair. Later westernized revolutionaries, influenced by western hairstyle began to view the braid as backward and advocated adopting short haired western hairstyles. Han rebels, such as the Taiping, even retained their queue braids but grew hair on the front of the head. The Qing government accordingly viewed shaving the front of the head as the primary sign of loyalty, rather than the braid on the back, which traditional Han did not object to. Koxinga

Zheng Chenggong (; 27 August 1624 – 23 June 1662), born Zheng Sen () and better known internationally by his honorific title Koxinga (, from Taiwanese: ''kok sèⁿ iâ''), was a Southern Ming general who resisted the Qing conquest of Chin ...

insulted and criticized the Qing hairstyle by referring to the shaven pate as looking like a fly. Koxinga and his men objected when the Qing demanded they shave in exchange for recognizing Koxinga as a feudatory. The Qing demanded that Zheng Jing

Zheng Jing, Prince of Yanping (; 25 October 1642 – 17 March 1681), courtesy names Xianzhi () and Yuanzhi (), Art name, pseudonym Shitian (), was initially a Southern Ming military general who later became the second ruler of the Tungning King ...

and his men on Taiwan shave in order to receive recognition as a fiefdom. His men and Ming prince Zhu Shugui fiercely objected to shaving.

On 31 December 1650, Dorgon suddenly died during a hunting expedition, marking the official start of the Shunzhi Emperor's personal rule. Because the emperor was only 12 years old at that time, most decisions were made on his behalf by his mother, Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang, who turned out to be a skilled political operator.

Although his support had been essential to Shunzhi's ascent, Dorgon had centralised so much power in his hands as to become a direct threat to the throne. So much so that upon his death he was bestowed the extraordinary posthumous title of Emperor Yi (), the only instance in Qing history in which a Manchu " prince of the blood" () was so honored. Two months into Shunzhi's personal rule, however, Dorgon was not only stripped of his titles but his corpse was disinterred and mutilated to atone for multiple "crimes", one of which was persecuting to death Shunzhi's agnate eldest brother, Hooge. More importantly, Dorgon's symbolic fall from grace also led to the purge of his family and associates at court, thus reverting power back to the person of the emperor. After a promising start, Shunzhi's reign was cut short by his early death in 1661 at the age of 24 from smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

. He was succeeded by his third son Xuanye, who reigned as the Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 165420 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, personal name Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign of 61 ...

.

The Manchus sent Han Bannermen to fight against Koxinga's Ming loyalists in Fujian. They removed the population from coastal areas in order to deprive Koxinga's Ming loyalists of resources. This led to a misunderstanding that Manchus were "afraid of water". Han Bannermen carried out the fighting and killing, casting doubt on the claim that fear of the water led to the coastal evacuation and ban on maritime activities. Even though a poem refers to the soldiers carrying out massacres in Fujian as "barbarians", both Han Green Standard Army

The Green Standard Army (; ) was the name of a category of military units under the control of Qing dynasty in China. It was made up mostly of ethnic Han soldiers and operated concurrently with the Manchu-Mongol- Han Eight Banner armies. In are ...

and Han Bannermen were involved and carried out the worst slaughter. 400,000 Green Standard Army soldiers were used against the Three Feudatories in addition to the 200,000 Bannermen.

Kangxi Emperor's reign and consolidation

The sixty-one year reign of the

The sixty-one year reign of the Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 165420 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, personal name Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper. His reign of 61 ...

was the longest of any Chinese emperor. Kangxi's reign is also celebrated as the beginning of an era known as the " High Qing", during which the dynasty reached the zenith of its social, economic and military power. Kangxi's long reign started when he was eight years old upon the untimely demise of his father. To prevent a repeat of Dorgon

Dorgon (17 November 1612 – 31 December 1650) was a Manchu prince and regent of the early Qing dynasty. Born in the House of Aisin-Gioro as the 14th son of Nurhaci (the founder of the Later Jin dynasty, which was the predecessor of the Qi ...

's dictatorial monopolizing of power during the regency, the Shunzhi Emperor, on his deathbed, hastily appointed four senior cabinet ministers to govern on behalf of his young son. The four ministers – Sonin, Ebilun

Ebilun (Manchu:, Möllendorff: ebilun; ; died 1673) was a Manchu noble and warrior of the Niohuru clan, most famous for being one of the Four Regents assisting the young Kangxi Emperor from 1661 to 1667, during the early Qing dynasty (1644– ...

, Suksaha

Suksaha (Manchu: ; ; died 1667) was a Manchu official of the early Qing dynasty from the Nara clan. A military officer who participated in the Manchu conquest of China, Suksaha became one of the Four Regents during the early reign of the Kangxi ...

, and Oboi

Oboi (Manchu: , Mölendorff: Oboi; ) (c. 1610–1669) was a prominent Manchu military commander and courtier who served in various military and administrative posts under three successive emperors of the early Qing dynasty. Born to the Guwalg ...

– were chosen for their long service, but also to counteract each other's influences. Most important, the four were not closely related to the imperial family and laid no claim to the throne. However, as time passed, through chance and machination, Oboi, the most junior of the four, achieved such political dominance as to be a potential threat. Even though Oboi's loyalty was never an issue, his personal arrogance and political conservatism led him into an escalating conflict with the young emperor. In 1669 Kangxi, through trickery, disarmed and imprisoned Oboi – a significant victory for a fifteen-year-old emperor over a wily politician and experienced commander.

The early Manchu rulers established two foundations of legitimacy that help to explain the stability of their dynasty. The first was the bureaucratic institutions and the neo-Confucian

Neo-Confucianism (, often shortened to ''lǐxué'' 理學, literally "School of Principle") is a Morality, moral, Ethics, ethical, and metaphysics, metaphysical Chinese philosophy influenced by Confucianism, which originated with Han Yu (768� ...

culture that they adopted from earlier dynasties. Manchu rulers and Han Chinese scholar-official

The scholar-officials, also known as literati, scholar-gentlemen or scholar-bureaucrats (), were government officials and prestigious scholars in Chinese society, forming a distinct social class.

Scholar-officials were politicians and governmen ...

elites gradually came to terms with each other. The examination system

A standardized test is a test that is administered and scored in a consistent or standard manner. Standardized tests are designed in such a way that the questions and interpretations are consistent and are administered and scored in a predetermined ...

offered a path for ethnic Han to become officials. Imperial patronage of Kangxi Dictionary

The ''Kangxi Dictionary'' () is a Chinese dictionary published in 1716 during the High Qing, considered from the time of its publishing until the early 20th century to be the most authoritative reference for written Chinese characters. Wanting ...

demonstrated respect for Confucian learning, while the Sacred Edict of 1670 effectively extolled Confucian family values. His attempts to discourage Chinese women from foot binding

Foot binding (), or footbinding, was the Chinese custom of breaking and tightly binding the feet of young girls to change their shape and size. Feet altered by foot binding were known as lotus feet and the shoes made for them were known as lotus ...

, however, were unsuccessful.

The second major source of stability was the

The second major source of stability was the Inner Asia

Inner Asia refers to the northern and landlocked regions spanning North Asia, North, Central Asia, Central, and East Asia. It includes parts of Western China, western and northeast China, as well as southern Siberia. The area overlaps with some d ...