History Of Neuroscience on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

From the

The earliest reference to the brain occurs in the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, written in the 17th century BC. The

The earliest reference to the brain occurs in the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, written in the 17th century BC. The

Work by

Work by

One major question for neuroscientists in the early twentieth century was the physiology of nerve impulses. In 1902 and again in 1912, Julius Bernstein advanced the hypothesis that the action potential resulted from a change in the permeability of the axonal membrane to ions. Bernstein was also the first to introduce the Nernst equation for resting potential across the membrane. In 1907, Louis Lapicque suggested that the action potential was generated as a threshold was crossed, what would be later shown as a product of the

One major question for neuroscientists in the early twentieth century was the physiology of nerve impulses. In 1902 and again in 1912, Julius Bernstein advanced the hypothesis that the action potential resulted from a change in the permeability of the axonal membrane to ions. Bernstein was also the first to introduce the Nernst equation for resting potential across the membrane. In 1907, Louis Lapicque suggested that the action potential was generated as a threshold was crossed, what would be later shown as a product of the  In the process of treating

In the process of treating

International Brain Initiative

was created in 2017, currently integrated by more than seven national-level brain research initiatives (US,

Australia

CanadaKoreaIsrael

spanning four continents.

A History of the Brain

ten-part series of BBC radio programmes {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Neuroscience it:Cervello#Storia

ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

ian mummifications to 18th-century scientific research on "globules" and neuron

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, excitable cell (biology), cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network (biology), neural net ...

s, there is evidence of neuroscience

Neuroscience is the scientific study of the nervous system (the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system), its functions, and its disorders. It is a multidisciplinary science that combines physiology, anatomy, molecular biology, ...

practice throughout the early periods of history. The early civilizations lacked adequate means to obtain knowledge about the human brain. Their assumptions about the inner workings of the mind, therefore, were not accurate. Early views on the function of the brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

regarded it to be a form of "cranial stuffing" of sorts. In ancient Egypt, from the late Middle Kingdom onwards, in preparation for mummification, the brain was regularly removed, for it was the heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ found in humans and other animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels. The heart and blood vessels together make the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrie ...

that was assumed to be the seat of intelligence. According to Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, during the first step of mummification: "The most perfect practice is to extract as much of the brain as possible with an iron hook, and what the hook cannot reach is mixed with drugs." Over the next five thousand years, this view came to be reversed; the brain is now known to be the seat of intelligence, although colloquial variations of the former remain as in "memorizing something by heart".

Antiquity

The earliest reference to the brain occurs in the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, written in the 17th century BC. The

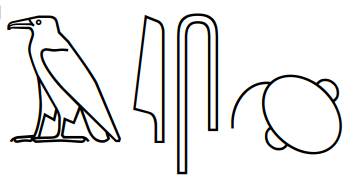

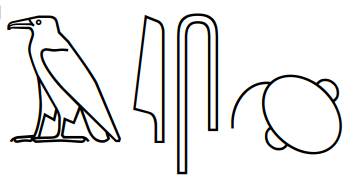

The earliest reference to the brain occurs in the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, written in the 17th century BC. The hieroglyph

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs ( ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined ideographic, logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with more than 1,000 distinct characters. ...

for brain, occurring eight times in this papyrus, describes the symptoms, diagnosis, and prognosis of two patients, wounded in the head, who had compound fractures of the skull. The assessments of the author (a battlefield surgeon) of the papyrus allude to ancient Egyptians having a vague recognition of the effects of head trauma. While the symptoms are well written and detailed, the absence of a medical precedent is apparent. The author of the passage notes "the pulsations of the exposed brain" and compared the surface of the brain to the rippling surface of copper slag (which indeed has a gyral-sulcal pattern). The laterality of injury was related to the laterality of symptom, and both aphasia ("he speaks not to thee") and seizures ("he shudders exceedingly") after head injury were described. Observations by ancient civilizations of the human brain suggest only a relative understanding of the basic mechanics and the importance of cranial security. Furthermore, considering the general consensus of medical practice pertaining to human anatomy was based on myths and superstition, the thoughts of the battlefield surgeon appear to be empirical and based on logical deduction and simple observation.

In Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

, interest in the brain began with the work of Alcmaeon, who appeared to have dissected the eye and related the brain to vision. He also suggested that the brain, not the heart, was the organ that ruled the body (what Stoics would call the ''hegemonikon'') and that the senses were dependent on the brain. According to ancient authorities, Alcmaeon believed the power of the brain to synthesize sensations made it also the seat of memories and thought. The author of '' On the Sacred Disease'', part of the Hippocratic corpus, likewise believed the brain to be the seat of intelligence.

The debate regarding the ''hegemonikon'' persisted among ancient Greek philosophers and physicians for a very long time. Already in the 4th century BC, Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

thought that the heart was the seat of intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

, while the brain was a cooling mechanism for the blood. He reasoned that humans are more rational than the beasts because, among other reasons, they have a larger brain to cool their hot-bloodedness. On the opposite end, during the Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

, Herophilus and Erasistratus of Alexandria engaged in studies that involved dissecting human bodies, providing evidence for the primacy of the brain. They affirmed the distinction between the cerebrum

The cerebrum (: cerebra), telencephalon or endbrain is the largest part of the brain, containing the cerebral cortex (of the two cerebral hemispheres) as well as several subcortical structures, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and olfac ...

and the cerebellum

The cerebellum (: cerebella or cerebellums; Latin for 'little brain') is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as it or eve ...

, and identified the ventricles and the dura mater. Their works are now mostly lost, and we know about their achievements due mostly to secondary sources. Some of their discoveries had to be re-discovered a millennium after their death.

During the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, the Greek physician and philosopher Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

dissected the brains of oxen, Barbary apes, swine, and other non-human mammals. He concluded that, as the cerebellum was denser than the brain, it must control the muscle

Muscle is a soft tissue, one of the four basic types of animal tissue. There are three types of muscle tissue in vertebrates: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle. Muscle tissue gives skeletal muscles the ability to muscle contra ...

s, while as the cerebrum was soft, it must be where the senses were processed. Galen further theorized that the brain functioned by the movement of animal spirits through the ventricles. He also noted that specific spinal nerves controlled specific muscles, and had the idea of the reciprocal action of muscles. Only in the 19th century, in the work of François Magendie and Charles Bell, would the understanding of spinal function surpass that of Galen.

Medieval to early modern

Islamic medicine in the middle ages was focused on how the mind and body interacted and emphasized a need to understand mental health. Circa 1000,Al-Zahrawi

Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbās al-Zahrāwī al-Ansari (; c. 936–1013), popularly known as al-Zahrawi (), Latinisation of names, Latinised as Albucasis or Abulcasis (from Arabic ''Abū al-Qāsim''), was an Arabs, Arab physician, su ...

, living in Islamic Iberia, evaluated neurological patients and performed surgical treatments of head injuries, skull fractures, spinal injuries, hydrocephalus, subdural effusions and headache. In Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

(Ibn-Sina) presented detailed knowledge about skull fractures and their surgical treatments.

Avicenna is regarded by some as the father of modern medicine. He wrote 40 pieces on medicine with the most notable being the Qanun, a medical encyclopedia that would become a staple at universities for nearly a hundred years. He also explained phenomena such as, insomnia, mania, hallucinations, nightmares, dementia, epilepsy, stroke, paralysis, vertigo, melancholia and tremors. He also described a condition similar to schizophrenia, which he called Junun Mufrit, characterized by agitation, behavioral and sleep disturbances, giving inappropriate answers to questions, and occasional inability to speak. Avicenna also discovered the cerebellar vermis, which he simply called the vermis, and the caudate nucleus. Both terms are still used in neuroanatomy today. He was also the first person to associate mental deficits with deficits in the brain's middle ventricle or frontal lobe. Abulcasis, Averroes

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinization of names, Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and Faqīh, jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astron ...

, Avenzoar, and Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

, active in the Medieval Muslim world, also described a number of medical problems related to the brain.

Between the 13th and 14th centuries, the first anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

textbooks in Europe, which included a description of the brain, were written by Mondino de Luzzi and Guido da Vigevano.

Renaissance

Work by

Work by Andreas Vesalius

Andries van Wezel (31 December 1514 – 15 October 1564), latinized as Andreas Vesalius (), was an anatomist and physician who wrote '' De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' ''in seven books''), which is ...

on human cadavers found problems with the Galenic view of anatomy. Vesalius noted many structural characteristics of both the brain and general nervous system during his dissections. In addition to recording many anatomical features such as the putamen and corpus callosum, Vesalius proposed that the brain was made up of seven pairs of 'brain nerves', each with a specialized function. Other scholars furthered Vesalius' work by adding their own detailed sketches of the human brain.

Scientific Revolution

In the 17th century,René Descartes

René Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramou ...

studied the physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

of the brain, proposing the theory of dualism to tackle the issue of the brain's relation to the mind. He suggested that the pineal gland was where the mind interacted with the body after recording the brain mechanisms responsible for circulating cerebrospinal fluid. Jan Swammerdam placed severed frog thigh muscle in an airtight syringe with a small amount of water in the tip and when he caused the muscle to contract by irritating the nerve, the water level did not rise but rather was lowered by a minute amount debunking balloonist theory. The idea that nerve stimulation led to movement had important implications by putting forward the idea that behaviour is based on stimuli. Thomas Willis studied the brain, nerves, and behavior to develop neurologic treatments. He described in great detail the structure of the brainstem

The brainstem (or brain stem) is the posterior stalk-like part of the brain that connects the cerebrum with the spinal cord. In the human brain the brainstem is composed of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The midbrain is conti ...

, the cerebellum, the ventricles, and the cerebral hemispheres.

Modern period

The role of electricity in nerves was first observed in dissected frogs by Luigi Galvani, Lucia Galeazzi Galvani and Giovanni Aldini in the second half of the 18th century. In 1811, César Julien Jean Legallois defined a specific function of a brain region for the first time. He studied respiration in animal dissection and lesions, and found the center of respiration in the medulla oblongata. Between 1811 and 1824, Charles Bell and François Magendie discovered throughdissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause of ...

and vivisection that the ventral roots in spine transmit motor impulses and the posterior roots receive sensory input ( Bell–Magendie law). In the 1820s, Jean Pierre Flourens pioneered the experimental method of carrying out localized lesions of the brain in animals describing their effects on motricity, sensibility and behavior. He concluded that the ablation of the cerebellum resulted in movements that “were not regular and coordinated". In 1843, Carlo Matteucci and Emil du Bois-Reymond demonstrated that nerve fibers transmitted electrical signals. Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (; ; 31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894; "von" since 1883) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The ...

measured these to travel at a rate between 24 and 38 meters per second in 1850.

In 1848, John Martyn Harlow described that Phineas Gage had his frontal lobe pierced by an iron tamping rod in a blasting accident. He became a case study in the connection between the prefrontal cortex

In mammalian brain anatomy, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) covers the front part of the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex. It is the association cortex in the frontal lobe. The PFC contains the Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA11, BA12, ...

and executive functions

In cognitive science and neuropsychology, executive functions (collectively referred to as executive function and cognitive control) are a set of cognitive processes that support goal-directed behavior, by regulating thoughts and actions thro ...

. In 1861, Paul Broca heard of a patient at the Bicêtre Hospital who had a 21-year progressive loss of speech and paralysis but neither a loss of comprehension nor mental function. Broca performed an autopsy and determined that the patient had a lesion in the frontal lobe

The frontal lobe is the largest of the four major lobes of the brain in mammals, and is located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere (in front of the parietal lobe and the temporal lobe). It is parted from the parietal lobe by a Sulcus (neur ...

in the left cerebral hemisphere

The vertebrate cerebrum (brain) is formed by two cerebral hemispheres that are separated by a groove, the longitudinal fissure. The brain can thus be described as being divided into left and right cerebral hemispheres. Each of these hemispheres ...

. Broca published his findings from the autopsies of twelve patients in 1865. His work inspired others to perform careful autopsies with the aim of linking more brain regions to sensory and motor functions. Another French neurologist, Marc Dax, made similar observations a generation earlier.Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed. Eric R. Kandel, James H. Schwartz, Thomas M. Jessel, eds. McGraw-Hill: New York, NY. 2000. Broca's hypothesis was supported by Gustav Fritsch

Gustav Theodor Fritsch (5 March 1838 – 12 June 1927) was a German anatomist, anthropologist, traveller and physiologist from Cottbus.

Fritsch studied natural science and medicine in Berlin, Breslau and Heidelberg. In 1874 he became an asso ...

and Eduard Hitzig

Eduard Hitzig (6 February 1838 – 20 August 1907) was a German neurologist and neuropsychiatrist of Jewish ancestryAndrew P. Wickens, ''A History of the Brain: From Stone Age Surgery to Modern Neuroscience'', Psychology Press (2014), p. 226 ...

who discovered in 1870 that electrical stimulation of motor cortex caused involuntary muscular contractions of specific parts of a dog's body and by observations of epileptic patients conducted by John Hughlings Jackson, who correctly deduced in the 1870s the organization of the motor cortex

The motor cortex is the region of the cerebral cortex involved in the planning, motor control, control, and execution of voluntary movements.

The motor cortex is an area of the frontal lobe located in the posterior precentral gyrus immediately ...

by watching the progression of seizures through the body. Carl Wernicke further developed the theory of the specialization of specific brain structures in language comprehension and production. Richard Caton presented his findings in 1875 about electrical phenomena of the cerebral hemispheres of rabbits and monkeys. In 1878, Hermann Munk found in dogs and monkeys that vision was localized in the occipital cortical area, David Ferrier

Sir David Ferrier FRS (13 January 1843 – 19 March 1928) was a pioneering Scottish neurologist and psychologist. Ferrier conducted experiments on the brains of animals such as monkeys and in 1881 became the first scientist to be prosecuted ...

found in 1881 that audition was localized in the superior temporal gyrus and Harvey Cushing found in 1909 that the sense of touch was localized in the postcentral gyrus. Modern research still uses the Korbinian Brodmann's cytoarchitectonic (referring to study of cell structure) anatomical definitions from this era in continuing to show that distinct areas of the cortex are activated in the execution of specific tasks.

Studies of the brain became more sophisticated after the invention of the microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory equipment, laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic ...

and the development of a staining procedure by Camillo Golgi during the late 1890s that used a silver chromate salt to reveal the intricate structures of single neurons. His technique was used by Santiago Ramón y Cajal and led to the formation of the neuron doctrine

The neuron doctrine is the concept that the nervous system is made up of discrete individual cells, a discovery due to decisive neuro-anatomical work of Santiago Ramón y Cajal and later presented by, among others, H. Waldeyer-Hartz. The term ' ...

, the hypothesis that the functional unit of the brain is the neuron. Golgi and Ramón y Cajal shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

in 1906 for their extensive observations, descriptions and categorizations of neurons throughout the brain. The hypotheses of the neuron doctrine were supported by experiments following Galvani's pioneering work in the electrical excitability of muscles and neurons. In 1898, British scientist John Newport Langley first coined the term "autonomic" in classifying the connections of nerve fibers to peripheral nerve cells. Langley is known as one of the fathers of the chemical receptor theory, and as the origin of the concept of "receptive substance". Towards the end of the nineteenth century Francis Gotch conducted several experiments on nervous system function. In 1899 he described the "inexcitable" or "refractory phase" that takes place between nerve impulse

An action potential (also known as a nerve impulse or "spike" when in a neuron) is a series of quick changes in voltage across a cell membrane. An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific Cell (biology), cell rapidly ri ...

s. His primary focus was on how nerve interaction affected the muscles and eyes.

Heinrich Obersteiner in 1887 founded the ‘‘Institute for Anatomy and Physiology of the CNS’’, later called Neurological or Obersteiner Institute of the Vienna University School of Medicine. It was one of the first brain research institutions in the world. He studied the cerebellar cortex, described the Redlich–Obersteiner's zone and wrote one of the first books on neuroanatomy in 1888. Róbert Bárány, who worked on the physiology and pathology of the vestibular apparatus, attended this school, graduating in 1900. Obersteiner was later superseded by Otto Marburg.

Twentieth century

Neuroscience during the twentieth century began to be recognized as a distinct unified academic discipline, rather than studies of the nervous system being a factor of science belonging to a variety of disciplines. Ivan Pavlov contributed to many areas of neurophysiology. Most of his work involved research intemperament

In psychology, temperament broadly refers to consistent individual differences in behavior that are biologically based and are relatively independent of learning, system of values and attitudes.

Some researchers point to association of tempera ...

, conditioning and involuntary reflex actions. In 1891, Pavlov was invited to the Institute of Experimental Medicine in St. Petersburg to organize and direct the Department of Physiology. He published ''The Work of the Digestive Glands'' in 1897, after 12 years of research. His experiments earned him the 1904 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine. During the same period, Vladimir Bekhterev discovered 15 new reflexes and is known for his competition with Pavlov regarding the study of conditioned reflexes. He founded the Psychoneurological Institute at the St. Petersburg State Medical Academy in 1907 where he worked with Alexandre Dogiel. In the institute, he attempted to establish a multidisciplinary approach to brain exploration. The Institute of Higher Nervous Activity in Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

was established on July 14, 1950.

Charles Scott Sherrington

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington (27 November 1857 – 4 March 1952) was a British neurophysiology, neurophysiologist. His experimental research established many aspects of contemporary neuroscience, including the concept of the spinal reflex as a ...

's work focused strongly on reflexes and his experiments led up to the discovery of motor unit

In biology, a motor unit is made up of a motor neuron and all of the skeletal muscle fibers innervated by the neuron's axon terminals, including the neuromuscular junctions between the neuron and the fibres. Groups of motor units often work tog ...

s. His concepts centered around unitary behaviour of cells activated or inhibited at what he called synapses. Sherrington received the Nobel prize for showing that reflexes require integrated activation and demonstrated reciprocal innervation of muscles ( Sherrington's law). Sherrington also worked with Thomas Graham Brown who developed one of the first ideas about central pattern generators in 1911. Brown recognized that the basic pattern of stepping can be produced by the spinal cord without the need of descending commands from the cortex.

Acetylcholine was the first neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a Chemical synapse, synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neurotra ...

to be identified. It was first identified in 1915 by Henry Hallett Dale for its actions on heart tissue. It was confirmed as a neurotransmitter in 1921 by Otto Loewi in Graz

Graz () is the capital of the Austrian Federal states of Austria, federal state of Styria and the List of cities and towns in Austria, second-largest city in Austria, after Vienna. On 1 January 2025, Graz had a population of 306,068 (343,461 inc ...

. Loewi demonstrated the ″humorale Übertragbarkeit der Herznervenwirkung″ first in amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s. He initially gave it the name Vagusstoff because it was released from the vagus nerve

The vagus nerve, also known as the tenth cranial nerve (CN X), plays a crucial role in the autonomic nervous system, which is responsible for regulating involuntary functions within the human body. This nerve carries both sensory and motor fibe ...

and in 1936 he wrote: ″I no longer hesitate to identify the ''Sympathicusstoff'' with adrenaline.″

dynamical system

In mathematics, a dynamical system is a system in which a Function (mathematics), function describes the time dependence of a Point (geometry), point in an ambient space, such as in a parametric curve. Examples include the mathematical models ...

s of ionic conductances. A great deal of study on sensory organs and the function of nerve cells was conducted by British physiologist Keith Lucas and his protege Edgar Adrian. Keith Lucas' experiments in the first decade of the twentieth century proved that muscles contract entirely or not at all, this was referred to as the all-or-none principle. Edgar Adrian observed nerve fibers in action during his experiments on frogs. This proved that scientists could study nervous system function directly, not just indirectly. This led to a rapid increase in the variety of experiments conducted in the field of neurophysiology

Neurophysiology is a branch of physiology and neuroscience concerned with the functions of the nervous system and their mechanisms. The term ''neurophysiology'' originates from the Greek word ''νεῦρον'' ("nerve") and ''physiology'' (whic ...

and innovation in the technology necessary for these experiments. Much of Adrian's early research was inspired by studying the way vacuum tubes intercepted and enhanced coded messages. Concurrently, Josepht Erlanger and Herbert Gasser were able to modify an oscilloscope

An oscilloscope (formerly known as an oscillograph, informally scope or O-scope) is a type of electronic test instrument that graphically displays varying voltages of one or more signals as a function of time. Their main purpose is capturing i ...

to run at low voltages and were able to observe that action potentials occurred in two phases—a spike followed by an after-spike. They discovered that nerves were found in many forms, each with their own potential for excitability. With this research, the pair discovered that the velocity of action potentials was directly proportional to the diameter of the nerve fiber and received a Nobel Prize for their work.

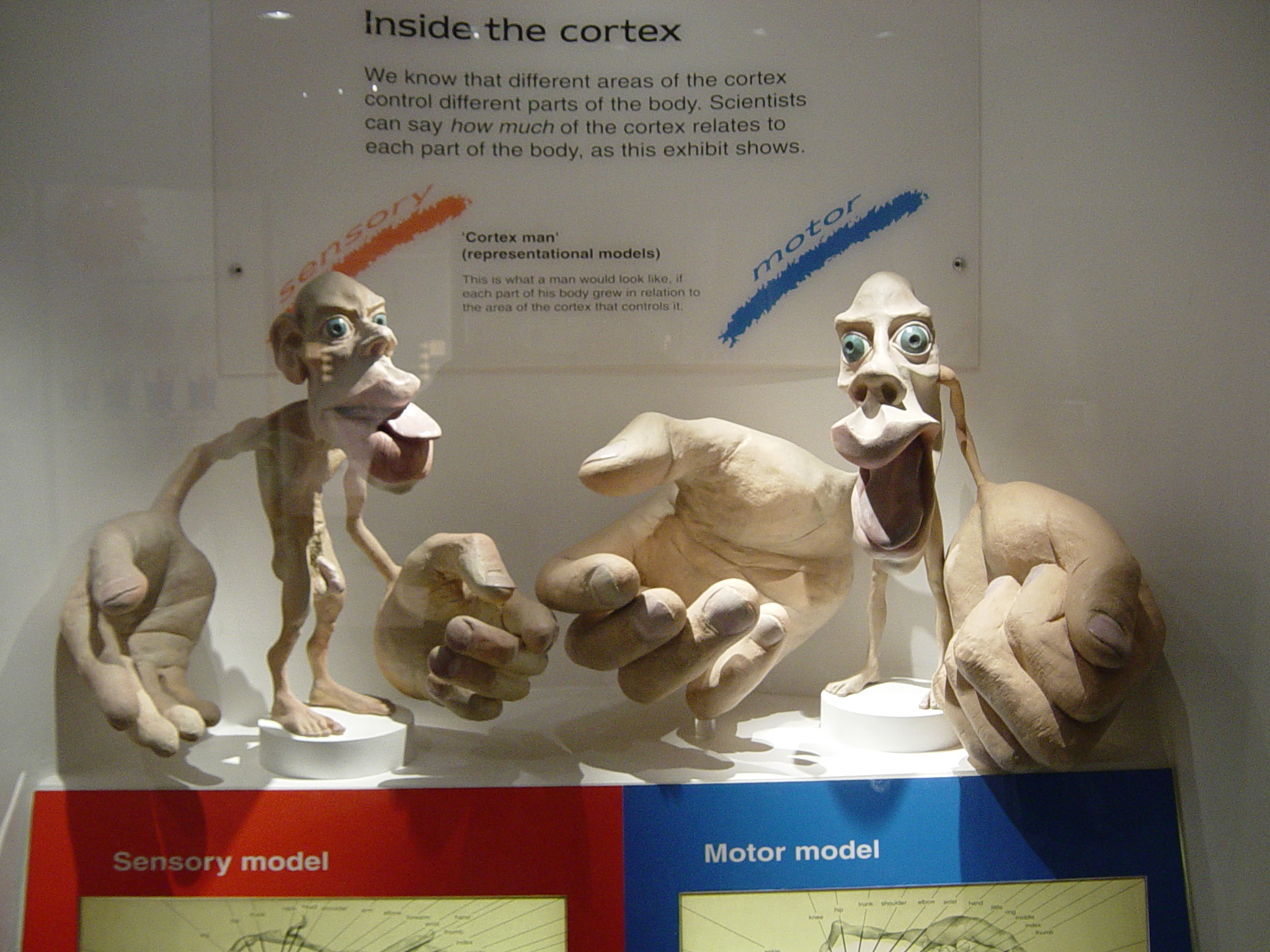

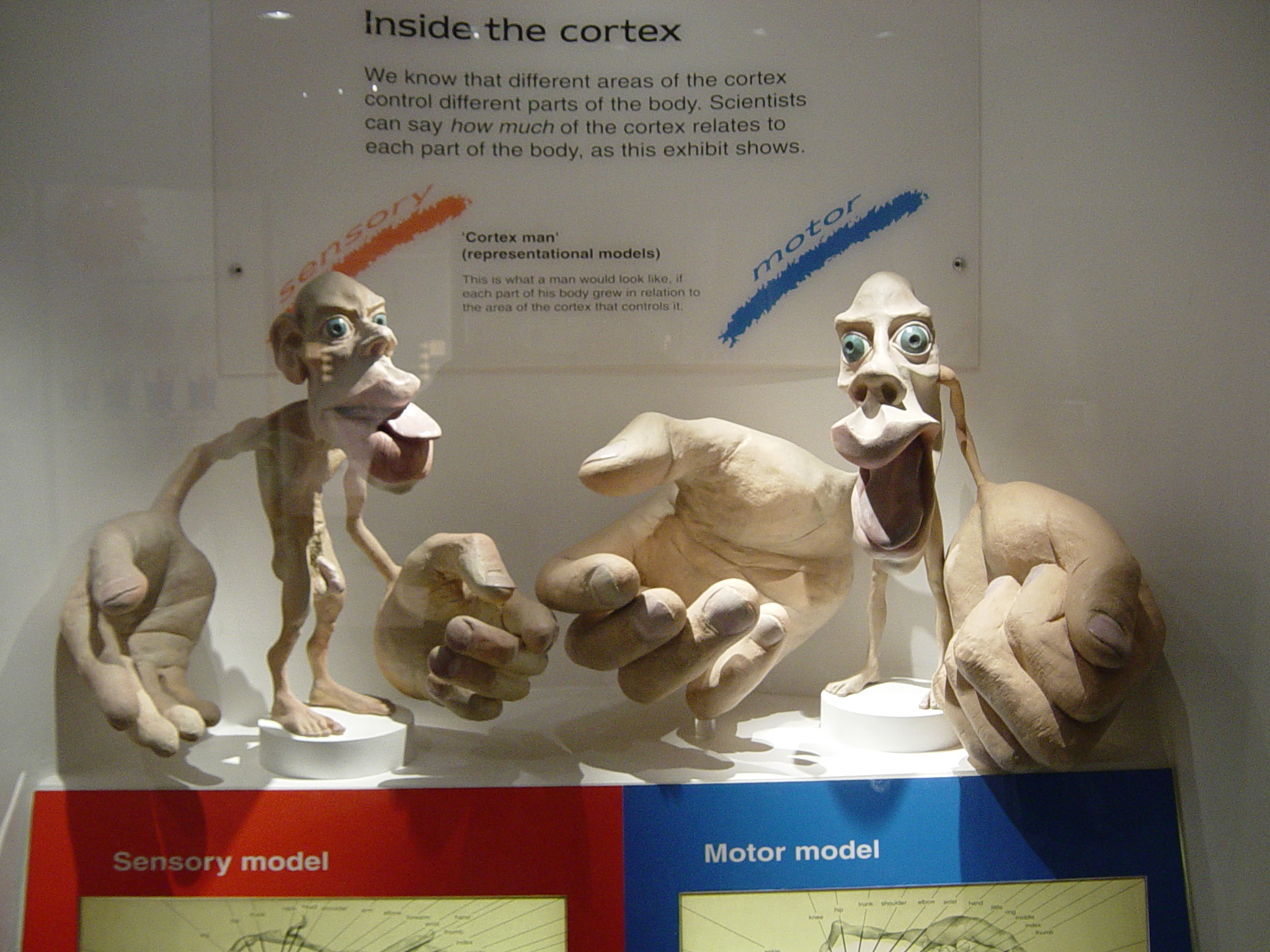

In the process of treating

In the process of treating epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of Non-communicable disease, non-communicable Neurological disorder, neurological disorders characterized by a tendency for recurrent, unprovoked Seizure, seizures. A seizure is a sudden burst of abnormal electrical activit ...

, Wilder Penfield produced maps of the location of various functions (motor, sensory, memory, vision) in the brain. He summarized his findings in a 1950 book called ''The Cerebral Cortex of Man''. Wilder Penfield and his co-investigators Edwin Boldrey and Theodore Rasmussen are considered to be the originators of the cortical homunculus.

Kenneth Cole joined Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

in 1937 and remained there until 1946 where he made pioneering advances modelling the electrical properties of nervous tissue. Bernstein's hypothesis about the action potential was confirmed by Cole and Howard Curtis, who showed that membrane conductance increases during an action potential. David E. Goldman worked with Cole and derived the Goldman equation in 1943 at Columbia University.

Alan Lloyd Hodgkin spent a year (1937–38) at the Rockefeller Institute, during which he joined Cole to measure the D.C. resistance of the membrane of the squid giant axon in the resting state. In 1939 they began using internal electrodes inside the giant nerve fibre of the squid and Cole developed the voltage clamp technique in 1947. Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley later presented a mathematical model for transmission of electrical signals in neurons of the giant axon of a squid and how they are initiated and propagated, known as the Hodgkin–Huxley model. In 1961–1962, Richard FitzHugh and J. Nagumo simplified Hodgkin–Huxley, in what is called the FitzHugh–Nagumo model. In 1962, Bernard Katz modeled neurotransmission across the space between neurons known as synapses. Beginning in 1966, Eric Kandel and collaborators examined biochemical changes in neurons associated with learning and memory storage in '' Aplysia''. In 1981 Catherine Morris and Harold Lecar combined these models in the Morris–Lecar model. Such increasingly quantitative work gave rise to numerous biological neuron models and models of neural computation.

Eric Kandel and collaborators have cited David Rioch, Francis O. Schmitt, and Stephen Kuffler as having played critical roles in establishing the field. Rioch originated the integration of basic anatomical and physiological research with clinical psychiatry at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, starting in the 1950s. During the same period, Schmitt established a neuroscience research program within the Biology Department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of moder ...

, bringing together biology, chemistry, physics, and mathematics. The first freestanding neuroscience department (then called Psychobiology) was founded in 1964 at the University of California, Irvine

The University of California, Irvine (UCI or UC Irvine) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Irvine, California, United States. One of the ten campuses of the University of California system, U ...

by James L. McGaugh. Stephen Kuffler started the Department of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School (HMS) is the medical school of Harvard University and is located in the Longwood Medical and Academic Area, Longwood Medical Area in Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1782, HMS is the third oldest medical school in the Un ...

in 1966. The first official use of the word "Neuroscience" may be in 1962 with Francis O. Schmitt's " Neuroscience Research Program", which was hosted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of moder ...

.

Over time, brain research has gone through philosophical, experimental, and theoretical phases, with work on brain simulation predicted to be important in the future.

Institutes and organizations

As a result of the increasing interest about the nervous system, several prominent neuroscience institutes and organizations have been formed to provide a forum to all neuroscientists. The largest professional neuroscience organization is the Society for Neuroscience (SFN), which is based in the United States but includes many members from other countries. In 2013, the BRAIN Initiative was announced in the US. AInternational Brain Initiative

was created in 2017, currently integrated by more than seven national-level brain research initiatives (US,

Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, Allen Institute, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

Australia

Canada

spanning four continents.

See also

* History of catecholamine research * History of neuraxial anesthesia * History of neurology and neurosurgery * History of psychiatry * History of psychology * History of neuropsychology * History of neurophysiology *History of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient history, ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural science, natural, social science, social, and formal science, formal. Pr ...

* List of neurologists

* List of neuroscientists

References

Further reading

* Rousseau, George S. (2004). ''Nervous Acts: Essays on Literature, Culture and Sensibility.'' Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. (Paperback) * Wickens, Andrew P. (2015) ''A History of the Brain: From Stone Age Surgery to Modern Neuroscience.'' London: Psychology Press. (Paperback), 978-84872-364-1 (Hardback), 978-1-315-79454-9 (Ebook)External links

*A History of the Brain

ten-part series of BBC radio programmes {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Neuroscience it:Cervello#Storia