Head Hunting on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Headhunting is the practice of hunting a human and

Headhunting is the practice of hunting a human and

Among the various

Among the various

Headhunting was a common practice among

Headhunting was a common practice among

Headhunting has been a practice among the Kukis, the Wa, Mizo, the Garo and the Naga ethnic groups of

Headhunting has been a practice among the Kukis, the Wa, Mizo, the Garo and the Naga ethnic groups of

A ''

A ''

The

The

During World War II, Allied (specifically including American) troops occasionally collected the skulls of dead Japanese as personal trophies, as souvenirs for friends and family at home, and for sale to others. (The practice was unique to the Pacific theater; United States forces did not take skulls of German and Italian soldiers.) In September 1942, the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet mandated strong disciplinary action against any soldier who took enemy body parts as souvenirs. But such trophy-hunting persisted: ''

During World War II, Allied (specifically including American) troops occasionally collected the skulls of dead Japanese as personal trophies, as souvenirs for friends and family at home, and for sale to others. (The practice was unique to the Pacific theater; United States forces did not take skulls of German and Italian soldiers.) In September 1942, the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet mandated strong disciplinary action against any soldier who took enemy body parts as souvenirs. But such trophy-hunting persisted: ''

File:Malayan Emergency Iban headhunter.jpg, alt=, An Iban headhunter wearing a Royal Marine beret prepares a human scalp above a basket of human body parts.

File:Iban headhunter holding scalp during Malayan Emergency.jpg, An Iban headhunter posing with a human scalp

File:This is the War in Malaya.jpg, The ''Daily Worker'' exposes the practice of headhunting among British troops in Malaya. 28 April 1952.

File:Headhunters Malayan Emergency.jpg, Commonwealth soldiers pose with a severed head inside a British military base in Malaya during the Malayan Emergency

File:Malayan Emergency headhunting and poles.jpg, Two corpses and a severed head belonging to guerrillas killed by the Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment.

File:Photo collection of British atrocities during the Malayan Emergency.png, Atrocity photographs (including headhunting) from the archives of the Working Class Movement Library, Manchester.

File:Beheaded MNLA guerrilla, Malayan Emergency.png, Severed head of MNLA guerrilla commander Hen Yan, killed in 1952 by the

File:Head trophy, Munduruku people, northern Brazil, c 1820 - Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde München - DSC08569.JPG, Head trophy,

Head-Hunting Roman Cavalry

- article about single combat and the taking of heads and scalps as trophies by Roman warriors

Les Romains, chasseurs de têtes

- paper by Jean-Louis Voisin about the Roman practice of head hunting *

{{Authority control Anthropology Human trophy collecting

Headhunting is the practice of hunting a human and

Headhunting is the practice of hunting a human and collecting

The hobby of collecting includes seeking, locating, acquiring, organizing, cataloging, displaying, storing, and maintaining items that are of interest to an individual ''collector''. Collections differ in a wide variety of respects, most obvi ...

the severed head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

after killing the victim. More portable body parts (such as ear

In vertebrates, an ear is the organ that enables hearing and (in mammals) body balance using the vestibular system. In humans, the ear is described as having three parts: the outer ear, the middle ear and the inner ear. The outer ear co ...

, nose

A nose is a sensory organ and respiratory structure in vertebrates. It consists of a nasal cavity inside the head, and an external nose on the face. The external nose houses the nostrils, or nares, a pair of tubes providing airflow through the ...

, or scalp

The scalp is the area of the head where head hair grows. It is made up of skin, layers of connective and fibrous tissues, and the membrane of the skull. Anatomically, the scalp is part of the epicranium, a collection of structures covering th ...

) can be taken as trophies

A trophy is a tangible, decorative item used to remind of a specific achievement, serving as recognition or evidence of merit. Trophies are most commonly awarded for sporting events, ranging from youth sports to professional level athletics. Add ...

, instead. Headhunting was practiced in historic times across parts of Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, East Asia

East Asia is a geocultural region of Asia. It includes China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan, plus two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau. The economies of Economy of China, China, Economy of Ja ...

, Oceania

Oceania ( , ) is a region, geographical region including Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Outside of the English-speaking world, Oceania is generally considered a continent, while Mainland Australia is regarded as its co ...

, Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

, South Asia

South Asia is the southern Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia that is defined in both geographical and Ethnicity, ethnic-Culture, cultural terms. South Asia, with a population of 2.04 billion, contains a quarter (25%) of the world's populatio ...

, Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El S ...

, South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

, West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

, and Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

.

The headhunting practice has been the subject of intense study within the anthropological community, where scholars try to assess and interpret its social roles

A role (also rôle or social role) is a set of connected behaviors, rights, obligations, beliefs, and norms as conceptualized by people in a social situation. It is an

expected or free or continuously changing behavior and may have a given indi ...

, functions, and motivations. Anthropological writings explore themes in headhunting that include mortification of the rival, ritual violence, cosmological

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

balance, the display of manhood

A man is an adult male human. Before adulthood, a male child or adolescent is referred to as a boy.

Like most other male mammals, a man's genome usually inherits an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chromosome from the fath ...

, cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is also well document ...

, dominance over the body and soul of his enemies in life and afterlife, as a trophy and proof of killing (achievement in hunting), show of greatness, prestige by taking on a rival's spirit and power, and as a means of securing the services of the victim as a slave in the afterlife.

Today's scholars generally agree that headhunting's primary function was ritual and ceremonial. It was part of the process of structuring, reinforcing, and defending hierarchical relationships between communities and individuals. Some experts theorize that the practice stemmed from the belief that the head contained the victim's "soul

The soul is the purported Mind–body dualism, immaterial aspect or essence of a Outline of life forms, living being. It is typically believed to be Immortality, immortal and to exist apart from the material world. The three main theories that ...

matter" or life force, which could be harnessed through its capture.

Austronesia

Among the various

Among the various Austronesian peoples

The Austronesian people, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples who have settled in Taiwan, maritime Southeast Asia, parts of mainland Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melan ...

, head-hunting

Headhunting is the practice of human hunting, hunting a human and human trophy collecting, collecting the decapitation, severed human head, head after killing the victim. More portable body parts (such as ear, rhinotomy, nose, or scalping, scal ...

raids were strongly tied to the practice of tattoo

A tattoo is a form of body modification made by inserting tattoo ink, dyes, or pigments, either indelible or temporary, into the dermis layer of the skin to form a design. Tattoo artists create these designs using several tattooing processes ...

ing. In head-hunting societies, tattoos were records of how many heads the warriors had taken in battle, and was part of the initiation rites into adulthood. The number and location of tattoos, therefore, were indicative of a warrior's status and prowess.

Indonesia and Malaysia

In Southeast Asia, anthropological writings have explored headhunting and other practices of the Murut, Dusun Lotud, Iban,Berawan

Berawan is an Austronesian language spoken in eastern Sarawak, Malaysia.

Dialects

# Lakiput

# Narom

# Lelak

# Dali

# Miri long teran

# Belait

# Tutong

# Long Terawan

# Long Tutoh

# Mulu Caves

Distribution

# Baram (Tutoh-Tinjar)

# Batu Bela ( ...

, Wana and Mappurondo tribes. Among these groups, headhunting was usually a ritual activity rather than an act of war or feuding. A warrior would take a single head. Headhunting acted as a catalyst for the cessation of personal and collective mourning

Mourning is the emotional expression in response to a major life event causing grief, especially loss. It typically occurs as a result of someone's death, especially a loved one.

The word is used to describe a complex of behaviors in which t ...

for the community's dead. Ideas of manhood and marriage were encompassed in the practice, and the taken heads were highly prized. Other reasons for headhunting included capture of enemies as slaves, looting of valuable properties, intra and inter-ethnic conflicts, and territorial expansion.

Italian anthropologist and explorer Elio Modigliani visited the headhunting communities in South Nias

Nias (, Nias: ''Tanö Niha'') is an island located off the western coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. Nias is also the name of the archipelago () of which the island is the centre, but also includes the Batu Islands to the southeast and the small ...

(an island to the west of Sumatra) in 1886; he wrote a detailed study of their society and beliefs. He found that the main purpose of headhunting was the belief that, if a man owned another person's skull, his victim would serve as a slave of the owner for eternity in the afterlife. Human skulls were a valuable commodity. Sporadic headhunting continued in Nias island until the late 20th century, the last reported incident dating from 1998.

Headhunting was practiced among Sumba people until the early 20th century. It was done only in large war parties. When the men hunted wild animals, by contrast, they operated in silence and secrecy. The skulls collected were hung on the skull tree erected in the center of village.

Kenneth George wrote about annual headhunting rituals that he observed among the Mappurondo religious minority, an upland tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

in the southwest part of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi

Sulawesi ( ), also known as Celebes ( ), is an island in Indonesia. One of the four Greater Sunda Islands, and the List of islands by area, world's 11th-largest island, it is situated east of Borneo, west of the Maluku Islands, and south of Min ...

. Heads are not taken; instead, surrogate heads in the form of coconuts are used in a ritual ceremony. The ritual, called ''pangngae,'' takes place at the conclusion of the rice-harvesting season. It functions to bring an end to communal mourning

Mourning is the emotional expression in response to a major life event causing grief, especially loss. It typically occurs as a result of someone's death, especially a loved one.

The word is used to describe a complex of behaviors in which t ...

for the deceased of the past year; express intercultural tensions and polemics; allow for a display of manhood; distribute communal resources; and resist outside pressures to abandon Mappurondo ways of life.

In Sarawak

Sarawak ( , ) is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia. It is the largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia. Sarawak is located in East Malaysia in northwest Borneo, and is ...

, the north-western region of the island of Borneo

Borneo () is the List of islands by area, third-largest island in the world, with an area of , and population of 23,053,723 (2020 national censuses). Situated at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, it is one of the Greater Sunda ...

, the first " White Rajah" James Brooke

James Brooke (29 April 1803 – 11 June 1868), was a British soldier and adventurer who founded the Raj of Sarawak in Borneo. He ruled as the first White Rajahs, White Rajah of Sarawak from 1841 until his death in 1868.

Brooke was born and ra ...

and his descendants established a dynasty. They eradicated headhunting in the hundred years before World War II. Before Brooke's arrival, the Iban had migrated from the middle Kapuas region into the upper Batang Lupar river region by fighting and displacing the small existing tribes, such as the Seru and Bukitan. Another successful migration by the Iban was from the Saribas region into the Kanowit area in the middle of the Batang Rajang river, led by the famous Mujah "Buah Raya". They fought and displaced such tribes as the Kanowit and Baketan.

Brooke first encountered the headhunting Iban of the Saribas-Skrang in Sarawak at the Battle of Betting Maru in 1849. He gained the signing of the Saribas Treaty with the Iban chief of that region, who was named Orang Kaya Pemancha Dana "Bayang". Subsequently, the Brooke dynasty expanded their territory from the first small Sarawak region to the present-day state of Sarawak. They enlisted the Malay, Iban, and other natives as a large unpaid force to defeat and pacify any rebellions in the states. The Brooke administration prohibited headhunting (''ngayau'' in Iban language) and issued penalties for disobeying the Rajah-led government decree. During expeditions sanctioned by the Brooke administration, they allowed headhunting. The natives who participated in Brooke-approved punitive expeditions were exempted from paying annual tax to the Brooke administration and/or given new territories in return for their service. There were intra-tribal and intertribal headhunting.

The most famous Iban warrior to resist the authority of the Brooke administration was Libau "Rentap". The Brooke government had to send three successive punitive expeditions in order to defeat Rentapi at his fortress on the top of Sadok Hill. Brooke's force suffered major defeats during the first two expeditions. During the third and final expedition, Brooke built a large cannon

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during th ...

called ''Bujang Sadok'' (Prince of Sadok Mount) to rival Rentap's cannon nicknamed ''Bujang Timpang Berang'' (The One Arm Bachelor) and made a truce with the sons of a famous chief, who supported Rentap in not recognizing the government of Brooke due to his policies.

The Iban performed a third major migration from upper Batang Ai region in the Batang Lupar region into the Batang Kanyau (Embaloh) onwards the upper Katibas and then to the Baleh/Mujong regions in the upper Batang Rajang region. They displaced the existing tribes of the Kayan, Kajang, Ukit, etc. The Brooke administration sanctioned the last migrations of the Iban, and reduced any conflict to a minimum. The Iban conducted sacred ritual ceremonies with special and complex incantations to invoke god's blessings, which were associated with headhunting. An example was the Bird Festival in the Saribas/Skrang region and Proper Festival in the Baleh region, both required for men of the tribes to become effective warriors.

During the Japanese occupation of British Borneo

Before the outbreak of World War II in the Pacific, the island of Borneo was divided into five territories. Four of the territories were in the north and under British control – Raj of Sarawak, Sarawak, Brunei, Crown Colony of Labuan, Labuan ...

during the Second World War, headhunting was revived among the natives. The Sukarno-led Indonesian forces fought against the formation of the Federation of Malaysia. Forces of Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak fought in addition, and headhunting was observed during the communist insurgency in Sarawak and what was then Malaya. The Iban were noted for headhunting, and were later recognised as good rangers and trackers during military operations, during which they were awarded fourteen medals of valour and honour.

Since 1997 serious inter-ethnic violence has erupted on the island of Kalimantan, involving the indigenous Dayak people

The Dayak (; older spelling: Dajak) or Dyak or Dayuh are the native groups of Borneo. It is a loose term for over 200 riverine and hill-dwelling ethnic groups, located principally in the central and southern interior of Borneo, each with its ...

s and immigrants from the island of Madura

is an list of islands of Indonesia, Indonesian island off the northeastern coast of Java. The island comprises an area of approximately (administratively including various smaller islands to the east, southeast and north that are administratively ...

. Events have included the Sambas riots and Sampit conflict. In 2001, during the Sampit conflict in the Central Kalimantan

Kalimantan (; ) is the Indonesian portion of the island of Borneo. It constitutes 73% of the island's area, and consists of the provinces of Central Kalimantan, East Kalimantan, North Kalimantan, South Kalimantan, and West Kalimantan. The non-Ind ...

town of Sampit, at least 500 Madurese were killed and up to 100,000 Madurese were forced to flee. Some Madurese bodies were decapitated in a ritual reminiscent of the Dayak headhunting tradition.

The Moluccans

Moluccans are the Melanesian- Austronesian and Papuan-speaking ethnic groups indigenous to the Maluku Islands (also called the Moluccas). The region was historically known as the Spice Islands, and today consists of two Indonesian provinces o ...

(especially Alfurs in Seram

Seram (formerly spelled Ceram; also Seran or Serang) is the largest and main island of Maluku province of Indonesia, despite Ambon Island's historical importance. It is located just north of the smaller Ambon Island and a few other adjacent i ...

), an ethnic group of mixed Austronesian-Papuan origin living in the Maluku Islands

The Maluku Islands ( ; , ) or the Moluccas ( ; ) are an archipelago in the eastern part of Indonesia. Tectonics, Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located in West ...

, were fierce headhunters until the Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia suppressed the practice.

Melanesia

Headhunting was practiced by manyAustronesian people

The Austronesian people, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples who have settled in Taiwan, maritime Southeast Asia, parts of mainland Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesi ...

in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands

The Pacific islands are a group of islands in the Pacific Ocean. They are further categorized into three major island groups: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Depending on the context, the term ''Pacific Islands'' may refer to one of several ...

. Headhunting has at one time or another been practiced among most of the peoples of Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from New Guinea in the west to the Fiji Islands in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Vanu ...

, including New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

. A missionary found 10,000 skulls in a community longhouse on Goaribari Island in 1901.

Historically, the Marind-anim

The Marind or Marind-Anim are an ethnic group of New Guinea, residing in the province of South Papua, Indonesia.

Geography

The Marind-anim live in South Papua, Indonesia.

They occupy a vast territory, which is situated on either side of the Bi ...

in New Guinea were famed because of their headhunting. The practice was rooted in their belief system and linked to the name-giving of the newborn. The skull was believed to contain a mana

Mana may refer to:

Religion and mythology

* Mana (Oceanian cultures), the spiritual life force energy or healing power that permeates the universe in Melanesian and Polynesian mythology

* Mana (food), archaic name for manna, an edible substance m ...

-like force. Headhunting was not motivated primarily by cannibalism, but the dead person's flesh was consumed in ceremonies following the capture and killing.

The Korowai, a Papuan tribe in the southeast of Irian Jaya

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Austral ...

, live in tree houses, some nearly high. This was originally believed to be a defensive practice, presumably as protection against the Citak, a tribe of neighbouring headhunters. Some researchers believe that the American Michael Rockefeller, who disappeared in New Guinea in 1961 while on a field trip, may have been taken by headhunters in the Asmat region. He was the son of New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller.

In '' The Cruise of the Snark'' (1911), the account by Jack London

John Griffith London (; January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors t ...

of his 1905 adventure sailing in Micronesia, he recounted that headhunters of Malaita

Malaita is the primary island of Malaita Province in Solomon Islands. Malaita is the most populous island of the Solomon Islands, with a population of 161,832 as of 2021, or more than a third of the entire national population. It is also the se ...

attacked his ship during a stay in Langa Langa Lagoon, particularly around Laulasi Island. His and other ships were kidnapping villagers as workers on plantations, a practice known as blackbirding

Blackbirding was the trade in indentured labourers from the Pacific in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It is often described as a form of slavery, despite the British Slavery Abolition Act 1833 banning slavery throughout the British Empire, ...

. Captain Mackenzie of the ship ''Minolta'' was beheaded by villagers as retribution for the loss of village men during an armed labour "recruiting" drive. The villagers believed that the ship's crew "owed" several more heads before the score was even.

New Zealand

In New Zealand, the Maori preserved the heads of some of their ancestors as well as certain enemies in a form known as '' mokomokai.'' They removed the brain and eyes, and smoked the head, preserving the moko tattoos. The heads were sold to European collectors in the late 1800s, in some instances having been commissioned and "made to order".Philippines

In the Philippines, headhunting was extensive among the various Cordilleran peoples (also known as "Igorot") of theLuzon

Luzon ( , ) is the largest and most populous List of islands in the Philippines, island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the List of islands of the Philippines, Philippine archipelago, it is the economic and political ce ...

highlands. It was tied with rites of passage, rice harvests, religious rituals to ancestor spirits, blood feud

A feud , also known in more extreme cases as a blood feud, vendetta, faida, clan war, gang war, private war, or mob war, is a long-running argument or fight, often between social groups of people, especially family, families or clans. Feuds begin ...

s, and indigenous tattooing. Cordilleran tribes used specific weapons for beheading enemies in raids and warfare, specifically the uniquely shaped head axes and various swords and knives. Though some Cordilleran tribes living near Christianized lowlanders during the Spanish colonial period had already abandoned the practice by the 19th century, they were still rampant in more remote areas beyond the reach of Spanish colonial authorities. The practices were finally suppressed in the early 20th century by the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

during the American colonial period of the Philippines

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

.

Taiwan

Headhunting was a common practice among

Headhunting was a common practice among Taiwanese aborigines

Taiwanese may refer to:

* of or related to Taiwan

**Culture of Taiwan

**Geography of Taiwan

** Taiwanese cuisine

*Languages of Taiwan

** Formosan languages

** Taiwanese Hokkien, also known as the Taiwanese language

* Taiwanese people, residents of ...

. All tribes practiced headhunting except the Yami people

The Tao people ( Yami: Tao no pongso) are an Austronesian ethnic group native to the tiny outlying Orchid Island of Taiwan. They have a maritime culture, with great ritual and spiritual significance placed on boat-building and fishing. Their wa ...

, who were previously isolated on Orchid Island

Orchid Island, known as Pongso no Tao by the indigenous inhabitants, is a volcanic island located off the southeastern coast of Taiwan, the island and the nearby are governed by Taiwan as in Taitung County, which is one of the county's two ...

, and the Ivatan people

The Ivatan people are an Austronesian ethnolinguistic group native to the Batanes and Babuyan Islands of the northernmost Philippines. They are genetically closely related to other ethnic groups in Northern Luzon, but also share close linguis ...

. It was associated with the peoples of the Philippines.

Taiwanese Plains Aborigines, Han Taiwanese

Han Taiwanese, also known as Taiwanese Han (), Taiwanese Han Chinese, or Han Chinese Taiwanese, are Taiwanese people of full or partial ethnic Han Chinese, Han ancestry. According to the Executive Yuan of Taiwan, they comprise 95 to 97 percent of ...

and Japanese settlers were choice victims of headhunting raids by Taiwanese Mountain Aborigines. The latter two groups were considered invaders, liars, and enemies. A headhunting raid would often strike at workers in the fields, or set a dwelling on fire and then kill and behead those who fled from the burning structure. The practice continued during the Japanese rule of Taiwan

The Geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, together with the Penghu, Penghu Islands, became an annexed territory of the Empire of Japan in 1895, when the Qing dynasty ceded Taiwan Province, Fujian-Taiwan Province in the Treaty of Shimonoseki a ...

, but ended in the 1930s due to brutal suppression by the Japanese colonial government.

The Taiwanese Aboriginal tribes, who were allied with the Dutch against the Chinese during the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion in 1652, turned against the Dutch in turn during the Siege of Fort Zeelandia. They defected to Koxinga

Zheng Chenggong (; 27 August 1624 – 23 June 1662), born Zheng Sen () and better known internationally by his honorific title Koxinga (, from Taiwanese: ''kok sèⁿ iâ''), was a Southern Ming general who resisted the Qing conquest of Chin ...

's Chinese forces. The Aboriginals (Formosans) of Sincan defected to Koxinga after he offered them amnesty. The Sincan Aboriginals fought for the Chinese and beheaded Dutch people in executions. The frontier aboriginals in the mountains and plains also surrendered and defected to the Chinese on May 17, 1661, celebrating their freedom from compulsory education under Dutch rule. They hunted down Dutch people, beheading them and trashing their Christian school textbooks.

At the Battle of Tamsui in the Keelung Campaign during the Sino-French War

The Sino-French or Franco-Chinese War, also known as the Tonkin War, was a limited conflict fought from August 1884 to April 1885 between the French Third Republic and Qing China for influence in Vietnam. There was no declaration of war.

The C ...

on 8 October 1884, the Chinese took prisoners and beheaded 11 French marines who were injured, in addition to ''La Galissonnière's'' captain Fontaine. The heads were mounted on bamboo poles and displayed to incite anti-French feelings. In China, pictures of the beheading of the Frenchmen were published in the ''Tien-shih-tsai Pictorial Journal'' in Shanghai.

Han Taiwanese and Taiwanese Aboriginals revolted against the Japanese in the Beipu Uprising in 1907 and Tapani Incident

The Tapani incident or Tapani uprising in 1915 was one of the biggest armed uprisings by Taiwanese Han Chinese, Han and Taiwanese aborigines, Aboriginals, including Taivoan people, Taivoan, against Taiwan under Japanese rule, Japanese rule in T ...

in 1915. The Seediq aboriginals revolted against the Japanese in the 1930 Musha Incident and resurrected the practice of headhunting, beheading Japanese during the revolt.

Mainland Asia

China

During theSpring and Autumn period

The Spring and Autumn period () was a period in History of China, Chinese history corresponding roughly to the first half of the Eastern Zhou (256 BCE), characterized by the gradual erosion of royal power as local lords nominally subject t ...

and Warring States period

The Warring States period in history of China, Chinese history (221 BC) comprises the final two and a half centuries of the Zhou dynasty (256 BC), which were characterized by frequent warfare, bureaucratic and military reforms, and ...

, Qin soldiers frequently collected their defeated enemies' heads as a means to accumulate merits. After Shang Yang

Shang Yang (; c. 390 – 338 BC), also known as Wei Yang () and originally surnamed Gongsun, was a Politician, statesman, chancellor and reformer of the Qin (state), State of Qin. Arguably the "most famous and most influential statesman of the ...

's reforms, the Qin armies adopted a meritocracy

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods or political power are vested in individual people based on ability and talent, rather than ...

system that awards the average soldiers, most of whom were conscripted serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed dur ...

and were not paid, an opportunity to earn promotions and rewards from their superiors by collecting the heads of enemies, a type of body count

A body count is the total number of people killed in a particular event. In combat, a body count is often based on the number of confirmed kills, but occasionally only an estimate. Often used in reference to military combat, the term can also r ...

. In this area, authorities also displayed heads of executed criminals in public spaces up to the early 20th century.

The Wa people

The Wa people ( Wa: Vāx; , ; ; ''Wáa'') are a Southeast Asian ethnic group that lives mainly in Northern Myanmar, in the northern part of Shan State and the eastern part of Kachin State, near and along Myanmar's border with China, as well as ...

, a mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher t ...

ethnic minority

The term "minority group" has different meanings, depending on the context. According to common usage, it can be defined simply as a group in society with the least number of individuals, or less than half of a population. Usually a minority g ...

in Southwest China

Southwestern China () is a region in the People's Republic of China. It consists of five provincial administrative regions, namely Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, and Xizang.

Geography

Southwestern China is a rugged and mountainous region, ...

, eastern Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

(Shan State

Shan State (, ; , ) is a administrative divisions of Myanmar, state of Myanmar. Shan State borders China (Yunnan) to the north, Laos (Louang Namtha Province, Louang Namtha and Bokeo Provinces) to the east, and Thailand (Chiang Rai Province, Chia ...

) and northern Thailand

Northern Thailand, or more specifically Lanna, is a region of Thailand. It is geographically characterized by several mountain ranges, which continue from the Shan Hills in bordering Myanmar to Laos, and the river valleys that cut through them. ...

, were once known as the "Wild Wa" by British colonists due to their traditional practice of headhunting.

Japan

Tom O'Neill wrote:Samurai The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...also sought glory by headhunting. When a battle ended, the warrior, true to his mercenary origins, would ceremoniously present trophy heads to a general, who would variously reward him with promotions in rank, gold or silver, or land from the defeated clan. Generals displayed the heads of defeated rivals in public squares.

Indian subcontinent and Indochina

Headhunting has been a practice among the Kukis, the Wa, Mizo, the Garo and the Naga ethnic groups of

Headhunting has been a practice among the Kukis, the Wa, Mizo, the Garo and the Naga ethnic groups of India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

and Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

till the 19th century. Nuristanis

The Nuristanis are an Indo-Iranian ethnic group native to the Nuristan Province (formerly Kafiristan) of northeastern Afghanistan and Chitral District of northwestern Pakistan. Their languages comprise the Nuristani branch of Indo-Iranian la ...

in eastern Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

were headhunters until the late 19th century.

Mizo people

Mizo warfare would often rely on secret attacks and ambushing in surprise of their enemies. This led to superstitions as to the time and auspciciousness to conduct a raid. A headhunting expedition would concern stargazing where the crescent of the moon would be studied as an omen. If a star accompanied the new moon on its right side, this was considered "the moon is brandishing a knife" hence not permitting a raid to occur. If the star appeared left of the crescent moon then this would be perceived as "the moon is carrying a head" which was auspicious for a raid. Another superstition concerned the minivet. If on a journey to raid, the minivet flew away from the village it was a sign of success. If it flew to the village while screeching then the omen would lead the party to turn back. A portion of men would be assigned to a raid and a portion to remain home to defend the village. After killing one's enemies, the victor was required to place their foot on the corpse and shout their name three times and sing a ''Bawhhla'' (battle song). This was due to the belief that doing so would enable the killed warrior to become the victor's slave in the afterlife. By proclaiming his name and singing a song, the slave would recognise his master's voice. Following this, the heads would be decapitated. If the journey home was too long then the scalps of the heads would be taken instead as proof of their victory. Returning to the village, it was a taboo to bring the heads in during daylight. The war party would remain outside the village and delay their entrance. Only after dinner and the courtship hours between young men and women in the evening would permit for the party to enter. The arrival with the heads would announce themselves with gunshots and a ''bawhhla'' of their victory. Village maidens would then take initiative throughout the night to make an ''Arkeziak'' to tie on the heads, necks, wrists, ankles or upper arms of the warriors. The ''Arkeziak'' was made with a white spun cotton not boiled with rice and plaited into a pattern with tassels. The rest of the village would not meet the party out of taboo while the return was being celebrated with battle songs and gunshots. The following morning, the women tied the ''Arkeziak'' made during the night. The village chief and ''upas'' would honour the warriors with necklaces of amber and semi-precious stones. Even if a warrior had failed to bring back a head or scalp, any assistance in procuring the heads of the corpses would see them on equal footing with the rest of the warriors, however, with less rewards. The heads would be accompanied with other spoils of war such as guns, gongs, spears and knives distributed to the families of the warriors via small payments. It was forbidden to ask for trophies or receive them as a gift. The heads of the warriors would be stored in the ''Thirdengsa'' (blacksmiths forge). After breakfast, a ceremony would be held. The heads would be retrieved from the forge and each warrior would carry the head they procured from slaying and assemble in front of the chief's house in the village square. A small table would be made for the heads to be placed. A broken piece of pottery would be placed with stale rice in it. A ritual dance would be performed for the ceremony. Young women would alsojoin the ritual dance. The warriors would surround the table to perform another custom. The party leader would have a boiled egg in his bag. Half of the egg would be consumed with the other half squeezed and sprinkled into the stale rice in the broken pot. A spell would be chanted to curse the heads on the table. A battle song would be sung and the gun would be fired three times. Music and song would then play following this. The warriors would also during this period taunt, gloat and scoff at the heads. Guns would be loaded with gunpowder but no bullets as they were fired at the heads. Following this, a pot of zu would be placed in the village square. A mithun would be killed and offered to the warriors. A feast would be held with the customs of serving zu. After the complete ceremony, the heads would be taken and fixed on the ends of freshly cut poles. The poles would be placed on the west side of the village and erected in a row in the ''lungdawh'' (cemetery). Some heads would be suspended to the entrance to the village. Any tree hanging the heads of enemies would be known as ''Sah-lam''. A headhunter was also expected to sacrifice a mithun or a pig under a superstition that doing so would not engage the spirit of the head to turn the headhunter insane.Wa people

TheWa people

The Wa people ( Wa: Vāx; , ; ; ''Wáa'') are a Southeast Asian ethnic group that lives mainly in Northern Myanmar, in the northern part of Shan State and the eastern part of Kachin State, near and along Myanmar's border with China, as well as ...

, whose domain straddles the Burma-China border, were once known to Europeans as the "Wild Wa" for their "savage" behavior. Until the 1970s, the Wa practiced headhunting.

Americas

Amazon

Several tribes of the Jivaroan group, including theShuar

The Shuar, also known as Jivaro, are an indigenous ethnic group that inhabits the Ecuadorian and Peruvian Amazonia. They are famous for their hunting skills and their tradition of head shrinking, known as Tzantsa.

The Shuar language belongs to ...

in Eastern Ecuador and Northern Peru, along the rivers Chinchipe, Bobonaza, Morona, Upano, and Pastaza, main tributaries of the Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technology company

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek myth ...

, practiced headhunting for trophies. The heads were shrunk, and were known locally as ''Tzan-Tzas''. The people believed that the head housed the soul of the person killed.

In the 21st century, the Shuar produce Tzan-tza replicas. They use their traditional process on heads of monkeys

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes. Thus monkeys, in that sense, co ...

and sloths, selling the items to tourists. It is believed that splinter groups in the local tribes continue with these practices when there is a tribal feud over territory or as revenge for a crime of passion.

The Kichwa-Lamista people in Peru used to be headhunters.

Mesoamerican civilizations

A ''

A ''tzompantli

A () or skull rack was a type of wooden rack or palisade documented in several Mesoamerican civilizations, which was used for the public display of human skulls, typically those of human trophy taking in Mesoamerica, war captives or other huma ...

'' is a type of wooden rack or palisade documented in several Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El S ...

n civilizations. It was used for the public display of human skull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominen ...

s, typically those of war captives or other sacrificial victims.

A tzompantli-type structure has been excavated at the La Coyotera, Oaxaca

Oaxaca, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca, is one of the 32 states that compose the political divisions of Mexico, Federative Entities of the Mexico, United Mexican States. It is divided into municipalities of Oaxaca, 570 munici ...

site. It is dated to the Proto-Classic Zapotec civilization

The Zapotec civilization ( "The People"; 700 BC–1521 AD) is an Indigenous peoples, indigenous Pre-Columbian era, pre-Columbian civilization that flourished in the Valley of Oaxaca in Mesoamerica. Archaeological evidence shows that their cultu ...

, which flourished from c. 2nd century BCE to the 3rd century CE. ''Tzompantli'' are also noted in other Mesoamerican pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, or as the pre-Cabraline era specifically in Brazil, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European col ...

cultures, such as the Toltec

The Toltec culture () was a Pre-Columbian era, pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture that ruled a state centered in Tula (Mesoamerican site), Tula, Hidalgo (state), Hidalgo, Mexico, during the Epiclassic and the early Post-Classic period of Mesoam ...

and Mixtec

The Mixtecs (), or Mixtecos, are Indigenous Mesoamerican peoples of Mexico inhabiting the region known as La Mixteca of Oaxaca and Puebla as well as La Montaña Region and Costa Chica of Guerrero, Costa Chica Regions of the state of Guerre ...

.

Based on numbers given by the conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (; ; ) were Spanish Empire, Spanish and Portuguese Empire, Portuguese colonizers who explored, traded with and colonized parts of the Americas, Africa, Oceania and Asia during the Age of Discovery. Sailing ...

Andrés de Tapia and Fray Diego Durán

Diego Durán (c. 1537 – 1588) was a Dominican friar best known for his authorship of one of the earliest Western books on the history and culture of the Aztecs, ''The History of the Indies of New Spain'', a book that was much criticised in ...

, Bernard Ortiz de Montellano has calculated in the late 20th century that there were at most 60,000 skulls on the ''Hueyi Tzompantli'' (great Skullrack) of Tenochtitlan

, also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear, but the date 13 March 1325 was chosen in 1925 to celebrate the 600th annivers ...

. There were at least five more skullracks in Tenochtitlan, but, by all accounts, they were much smaller.

Other examples are indicated from Maya civilization

The Maya civilization () was a Mesoamerican civilization that existed from antiquity to the early modern period. It is known by its ancient temples and glyphs (script). The Maya script is the most sophisticated and highly developed writin ...

sites. A particularly fine and intact inscription example survives at the extensive Chichen Itza

Chichén Itzá , , often with the emphasis reversed in English to ; from () "at the mouth of the well of the Itza people, Itza people" (often spelled ''Chichen Itza'' in English and traditional Yucatec Maya) was a large Pre-Columbian era, ...

site.

Nazca culture

The Nazca used severed heads, known as trophy heads, in various religious rituals. Late Nazca iconography suggests that the prestige of the leaders of Late Nazca society was enhanced by successful headhunting.Europe

Celts

TheCelts

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

of Europe practiced headhunting as the head was believed to house a person's soul. Ancient Romans and Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

recorded the Celts' habits of nailing heads of personal enemies to walls or dangling them from the necks of horses. The Celtic Gaels practiced headhunting a great deal longer. In the ''Ulster Cycle

The Ulster Cycle (), formerly known as the Red Branch Cycle, is a body of medieval Irish heroic legends and sagas of the Ulaid. It is set far in the past, in what is now eastern Ulster and northern Leinster, particularly counties Armagh, Do ...

'' of Irish mythology

Irish mythology is the body of myths indigenous to the island of Ireland. It was originally Oral tradition, passed down orally in the Prehistoric Ireland, prehistoric era. In the History of Ireland (795–1169), early medieval era, myths were ...

, the demigod

A demigod is a part-human and part-divine offspring of a deity and a human, or a human or non-human creature that is accorded divine status after death, or someone who has attained the "divine spark" (divine illumination). An immortality, immor ...

Cúchulainn beheads the three sons of Nechtan and mounting their heads on his chariot. This is believed to have been a traditional warrior, rather than religious, practice. The practice continued approximately to the end of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

among the Irish clan

Irish clans are traditional kinship groups sharing a common surname and heritage and existing in a lineage-based society, originating prior to the 17th century. A clan (or in Irish, plural ) included the chief and his patrilineal relatives; howe ...

s and even later among the Border Reivers

Border Reivers were Cattle raiding, raiders along the Anglo-Scottish border. They included both Scotland, Scottish and England, English people, and they raided the entire border country without regard to their victims' nationality.Hay, D. "E ...

of the Anglo-Scottish marches. The pagan religious reasons for headhunting were likely lost after the Celts' conversion to Christianity, even though the practice continued.

In former Celtic areas, cephalophore

A cephalophore (from the Greek for 'head-carrier') is a saint who is generally depicted carrying their severed head. In Christian art, this was usually meant to signify that the subject in question had been martyred by beheading. Depicting the ...

representations of saints (miraculously carrying their severed heads) were common."The stories of St. Edmund, St. Kenelm, St. Osyth, and St. Sidwell in England, St. Denis in France, St. Melor and St. Winifred in Celtic territory, preserve the pattern and strengthen the link between legend and folklore," Beatrice White observes. .

Heads were also taken among the Germanic tribes

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who lived in Northern Europe in Classical antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In modern scholarship, they typically include not only the Roman-era ''Germani'' who lived in both ''Germania'' and parts ...

and among Iberians

The Iberians (, from , ''Iberes'') were an ancient people settled in the eastern and southern coasts of the Iberian Peninsula, at least from the 6th century BC. They are described in Greek and Roman sources (among others, by Hecataeus of Mil ...

, but the purpose is unknown.

Montenegrins

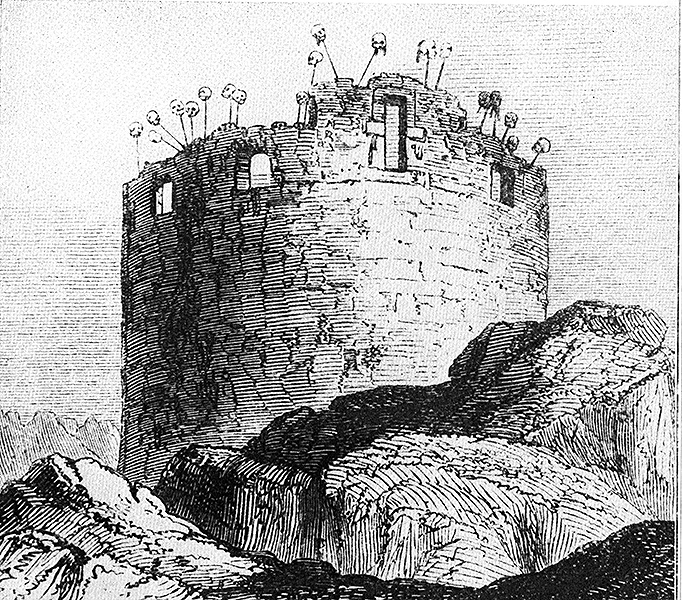

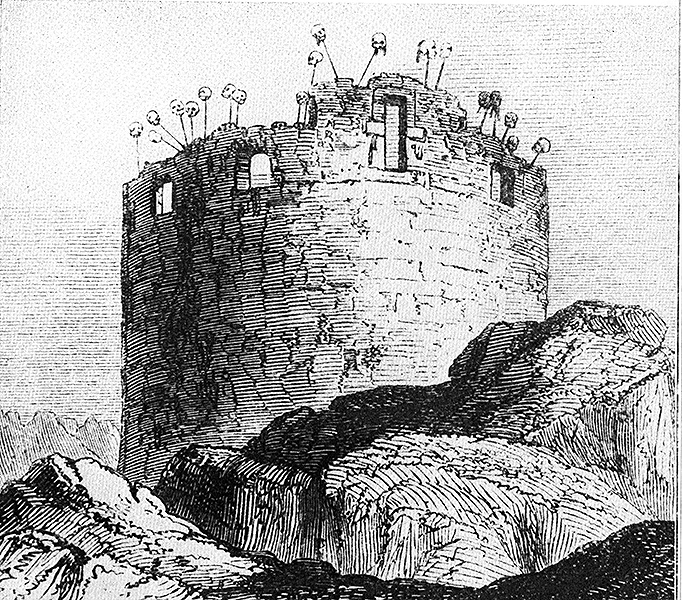

The

The Montenegrins

Montenegrins (, or ) are a South Slavic ethnic group that share a common ancestry, culture, history, and language, identified with the country of Montenegro.

Montenegrins are mostly Orthodox Christians; however, the population also includes ...

are an ethnic group in Southeastern Europe who are centered around the Dinaric mountains and are extremely closely related to Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of Serbia, history, and Serbian lan ...

. They practiced headhunting until 1876, allegedly carrying the head from a lock of hair grown specifically for that purpose.

In the 1830s, Montenegrin ruler Petar II Petrović-Njegoš

Petar II Petrović-Njegoš ( sr-cyrl, Петар II Петровић-Његош, ; – ), commonly referred to simply as Njegoš (), was a List of rulers of Montenegro, Prince-Bishop (''vladika'') of Montenegro, poet and philosopher whose ...

started building a tower called ''"Tablja"'' above Cetinje Monastery. The tower was never finished, and Montenegrins used it to display Turkish heads taken in battle, as they were in frequent conflict with the Ottoman Empire. In 1876 King Nicholas I of Montenegro

Nikola I Petrović-Njegoš ( sr-Cyrl, Никола I Петровић-Његош; – 1 March 1921) was the last monarch of Montenegro from 1860 to 1918, reigning as Principality of Montenegro, prince from 1860 to 1910 and as the country's first ...

ordered that the practice should end. He knew that European diplomats considered it to be barbaric. The ''Tablja'' was demolished in 1937.

Scythians

TheScythians

The Scythians ( or ) or Scyths (, but note Scytho- () in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern Iranian peoples, Iranian Eurasian noma ...

were excellent horsemen. Ancient Greek historian Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

wrote that some of their tribes practiced human sacrifice, drinking the blood of victims, scalping

Scalping is the act of cutting or tearing a part of the human scalp, with hair attached, from the head, and generally occurred in warfare with the scalp being a trophy. Scalp-taking is considered part of the broader cultural practice of the taki ...

their enemies, and drinking wine from the enemies' skulls.

Modern times

Second Sino-Japanese War

Nanjing Massacre

Many Chinese soldiers and civilians were beheaded by some Japanese soldiers, who even made contests to see who would kill more people ''(see Hundred man killing contest)'', and took photos with the piles of heads as souvenirs.World War II

During World War II, Allied (specifically including American) troops occasionally collected the skulls of dead Japanese as personal trophies, as souvenirs for friends and family at home, and for sale to others. (The practice was unique to the Pacific theater; United States forces did not take skulls of German and Italian soldiers.) In September 1942, the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet mandated strong disciplinary action against any soldier who took enemy body parts as souvenirs. But such trophy-hunting persisted: ''

During World War II, Allied (specifically including American) troops occasionally collected the skulls of dead Japanese as personal trophies, as souvenirs for friends and family at home, and for sale to others. (The practice was unique to the Pacific theater; United States forces did not take skulls of German and Italian soldiers.) In September 1942, the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet mandated strong disciplinary action against any soldier who took enemy body parts as souvenirs. But such trophy-hunting persisted: ''Life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

'' published a photograph in its issue of May 22, 1944, of a young woman posing with the autographed skull sent to her by her Navy boyfriend. There was public outrage in the US in response.

Historians have suggested that the practice related to Americans viewing the Japanese as lesser people, and in response to mutilation and torture of American war dead. In Borneo

Borneo () is the List of islands by area, third-largest island in the world, with an area of , and population of 23,053,723 (2020 national censuses). Situated at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, it is one of the Greater Sunda ...

, retaliation by natives against the Japanese was based on atrocities having been committed by the Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

in that area. Following their ill treatment by the Japanese, the Dayak of Borneo formed a force to help the Allies. Australian and British special operatives of Z Special Unit developed some of the inland Dayak tribesmen into a thousand-strong headhunting army. This army of tribesmen killed or captured some 1,500 Japanese soldiers.

Malayan Emergency

During theMalayan Emergency

The Malayan Emergency, also known as the Anti–British National Liberation War, was a guerrilla warfare, guerrilla war fought in Federation of Malaya, Malaya between communist pro-independence fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Arm ...

(1948–1960), British and Commonwealth forces recruited Iban (Dayak) headhunters from Borneo

Borneo () is the List of islands by area, third-largest island in the world, with an area of , and population of 23,053,723 (2020 national censuses). Situated at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, it is one of the Greater Sunda ...

to fight and decapitate suspected guerrillas of the socialist and pro-independence Malayan National Liberation Army

The Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) was a Communist guerrilla army that fought for Malayan independence from the British Empire during the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960) and later fought against the Malaysian government in the Commun ...

, officially claiming this was done for "identification" purposes. Iban headhunters were permitted to keep the scalps of corpses as trophies. Privately, the Colonial Office noted that "there is no doubt that under international law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

a similar case in wartime would be a war crime

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hostage ...

". Skull fragments from a trophy skull was later found to have been displayed in a British regimental museum.

In April 1952, the British Communist Party's official newspaper the ''Daily Worker'' (today known as the ''Morning Star'') published a photograph of Royal Marines

The Royal Marines provide the United Kingdom's amphibious warfare, amphibious special operations capable commando force, one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighting arms of the Royal Navy, a Company (military unit), company str ...

in a British military base in Malaya openly posing with severed human heads. Initially, British government spokespersons belonging to the Admiralty and the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created in 1768 from the Southern Department to deal with colonial affairs in North America (particularly the Thirteen Colo ...

denied the newspaper's claims and insisted that the photograph was a forgery. In response, the ''Daily Worker'' released yet another photograph taken in Malaya showing other British soldiers posing with a severed human head. In response, Colonial Secretary Oliver Lyttelton was forced to admit before the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

that the ''Daily Worker'' headhunting photographs were indeed genuine. In response to the ''Daily Worker'' articles, headhunting was banned by Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, who feared that further photographs would continue being exploited for communist propaganda.

Despite the shocking imagery of the photographs of soldiers posing with severed heads in Malaya, the ''Daily Worker'' was the only British newspaper to publish them during the 20th century, and the photographs were virtually ignored by the mainstream British press.

Interpretations of Headhunting

Headhunting attracts attention to cultures uninvolved in the ritualism of its practice. Early Western observers often considered it taboo, claiming the behavior to be evident of savage intent. Due to the tradition’s misunderstanding across most colonial Euro-American cultures, it fueled discrimination. Headhunting was easily attributed to an interpreted primitive life in the cultures that engaged in the behaviors. The belief that cultures performing headhunting rituals late into human history were savage led to forcible attempts of religious conversation made by Western colonizers. Ecocentric perspective created a divide between parties involved in these rituals and those witnessing from outside.Cultural Impact

Art

Headhunting appears frequently in many forms of tribal art. Trophy heads have been depicted in numerous cultures’ artwork, including sculptures, carvings, tattoos, and ceremonial masks. Each culture depicts their headhunting rituals distinctly through different art forms. In all art forms, the works depict powerful symbolic and cultural significance, varying in stylistic design. Mediums vary from wood to skin to textile. Fashion and dance are even recorded to depict representations of pride, sometimes even involving the severed heads, themselves. Mask usage in these ritualistic dances often depicted social status, power, and pride in affiliation with headhunting.Suffolk Regiment

The Suffolk Regiment was an infantry regiment Line infantry, of the line in the British Army with a history dating back to 1685. It saw service for three centuries, participating in many wars and conflicts, including the World War I, First and ...

.

File:Suspected MNLA guerrilla decapitated by British or Commonwealth during Malayan Emergency.png, Photographs of decapitated MNLA member held in the archives of the National Army Museum

The National Army Museum is the British Army's central museum. It is located in the Chelsea district of central London, adjacent to the Royal Hospital Chelsea, the home of the " Chelsea Pensioners". The museum is a non-departmental public bod ...

, London.

File:Stop This Horror in Malaya. Page 1 of 4.png, Anti-war leaflet published in 1952 protesting British headhunting in Malaya

Vietnam War

During theVietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, some American soldiers engaged in the practice of taking "trophy skulls".

Gallery

Munduruku

The Munduruku, also known as Mundurucu or Wuy Jugu, are an indigenous people of Brazil living in the Amazon River basin. Some Munduruku communities are part of the Coatá-Laranjal Indigenous Land. They had an estimated population in 2014 of 13 ...

people, northern Brazil, c. 1820

File:Dahomey amazon1.jpg, Seh-Dong-Hong-Beh, leader of the Dahomey Amazons

The Dahomey Amazons ( Fon: Agojie, Agoji, Mino, or Minon) were a Fon all-female military regiment of the Kingdom of Dahomey (in today's Benin, West Africa) that existed from the 17th century until the late 19th century. They were the only femal ...

, holding a severed head.

File:Ifugao headhunter.jpg, An Ifugao

Ifugao, officially the Province of Ifugao (; ), is a landlocked province of the Philippines in the Cordillera Administrative Region in Luzon. Its capital is Lagawe and it borders Benguet to the west, Mountain Province to the north, Isabela t ...

warrior with some of his trophies, Philippines, 1912

File:Dajakfrauen mit Menschenschädeln den Händen, zu einem Tanze versammelt.jpg, Dayak women dancing with human heads, 1912

File:The pagan tribes of Borneo; a description of their physical, moral and intellectual condition, with some discussion of their ethnic relations (1912) (14598073888).jpg, The Dayak longhouse

A longhouse or long house is a type of long, proportionately narrow, single-room building for communal dwelling. It has been built in various parts of the world including Asia, Europe, and North America.

Many were built from lumber, timber and ...

File:Kuniyoshi - 6 Select Heroes (S81.5), A back view of Onikojima Yatarô Kazutada in armor holding a spear and a severed head.jpg, Japanese samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

holding a severed head

File:Heads of Bandits Shot to Death in Tieling.jpg, Severed heads of bandits Tieling, Manchuria in 1928, during the government of Zhang Xueliang

Zhang Xueliang ( zh, t=張學良; June 3, 1901 – October 15, 2001), also commonly known by his nickname "the Young Marshal", was a Chinese general who in 1928 succeeded his father Zhang Zuolin as the commander of the Northeastern Army. He is bes ...

See also

*Shrunken head

A shrunken head is a severed and specially-prepared human head with the skull removed many times smaller than its original size that is used for trophy, ritual, trade, or other purposes.

Headhunting is believed to have occurred in many regi ...

* Scalping

Scalping is the act of cutting or tearing a part of the human scalp, with hair attached, from the head, and generally occurred in warfare with the scalp being a trophy. Scalp-taking is considered part of the broader cultural practice of the taki ...

* Decapitation

Decapitation is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and all vertebrate animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood by way of severing through the jugular vein and common c ...

* Skull cup

* Human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...

* Human trophy collecting

The practice of human trophy collecting involves the acquisition of human body parts as trophy, usually as war trophy. The intent may be to demonstrate dominance over the deceased (such as scalp-taking or forming necklaces of severed ears or t ...

* Macheteros de Jara

* Laulasi Island

* Beheading in Islam

* Headless Horseman

The Headless Horseman is an archetype of mythical figure that has appeared in folklore around Europe since the Middle Ages. The figures are traditionally depicted as riders on horseback who are missing their heads. These myths have since inspired ...

* Plastered human skulls

Plastered human skulls are human skulls covered in layers of plaster and typically found in the ancient Levant, most notably around the city of Jericho, between 8,000 and 6,000 BC (approximately 9000 years ago), in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B per ...

* ''Crypteia

The Crypteia, also referred to as Krypteia or Krupteia (Greek: κρυπτεία ''krupteía'' from κρυπτός ''kruptós'', "hidden, secret"; members were κρύπται ''kryptai''), was an ancient Spartan state institution. The ''kryptai'' ...

'', a Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

n organization who routinely practised headhunting against the servile Helot

The helots (; , ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristics ...

population.

* Tribal warfare

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

Head-Hunting Roman Cavalry

- article about single combat and the taking of heads and scalps as trophies by Roman warriors

Les Romains, chasseurs de têtes

- paper by Jean-Louis Voisin about the Roman practice of head hunting *

External links

{{Authority control Anthropology Human trophy collecting