Gulf of Mexico on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Gulf of Mexico () is an

The

The

The

The  To the east, the stable Florida Platform was not covered by the sea until the latest Jurassic or the beginning of Cretaceous time. The Yucatán Platform was emergent until the mid-Cretaceous. After both platforms were submerged, the formation of

To the east, the stable Florida Platform was not covered by the sea until the latest Jurassic or the beginning of Cretaceous time. The Yucatán Platform was emergent until the mid-Cretaceous. After both platforms were submerged, the formation of

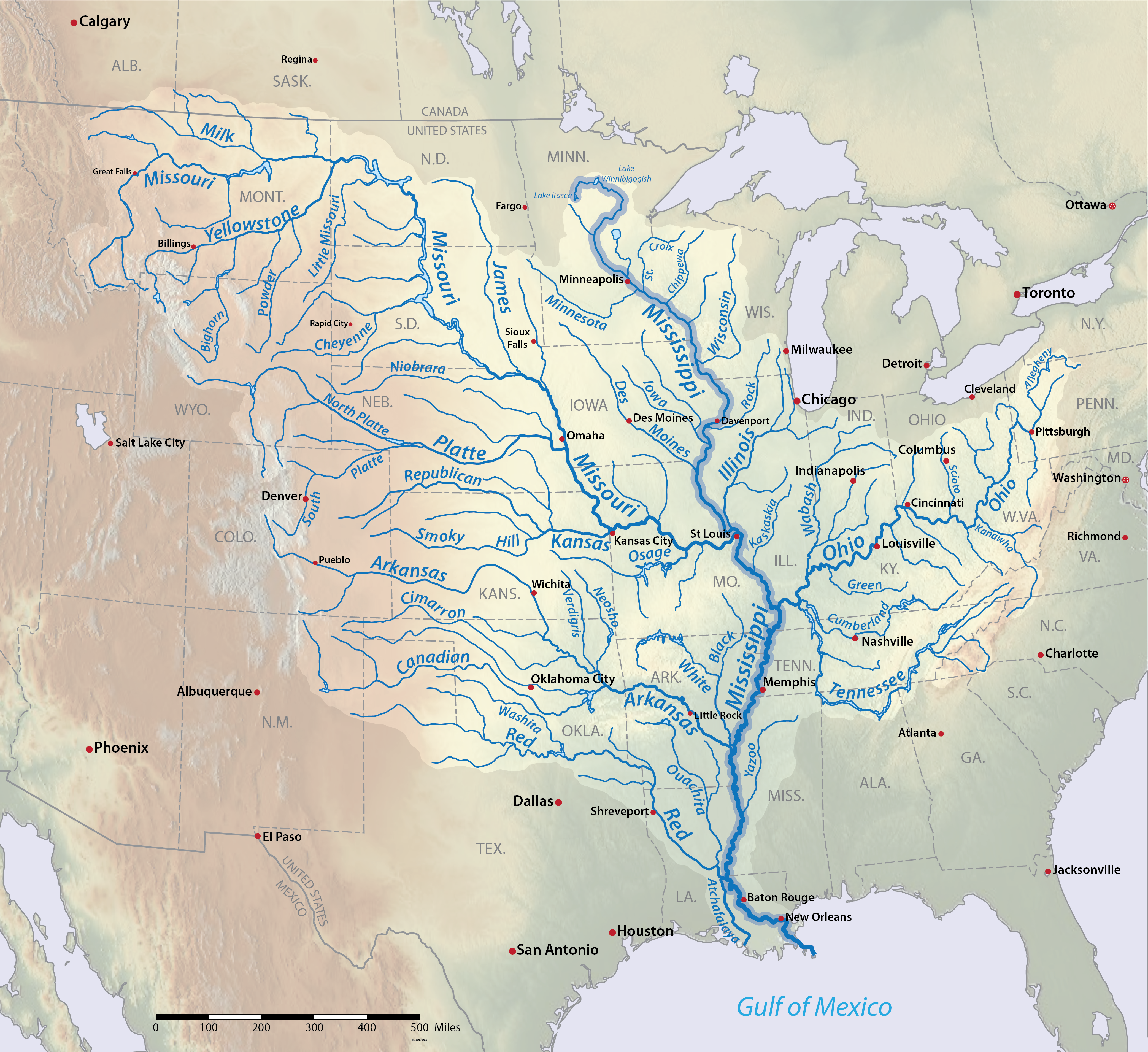

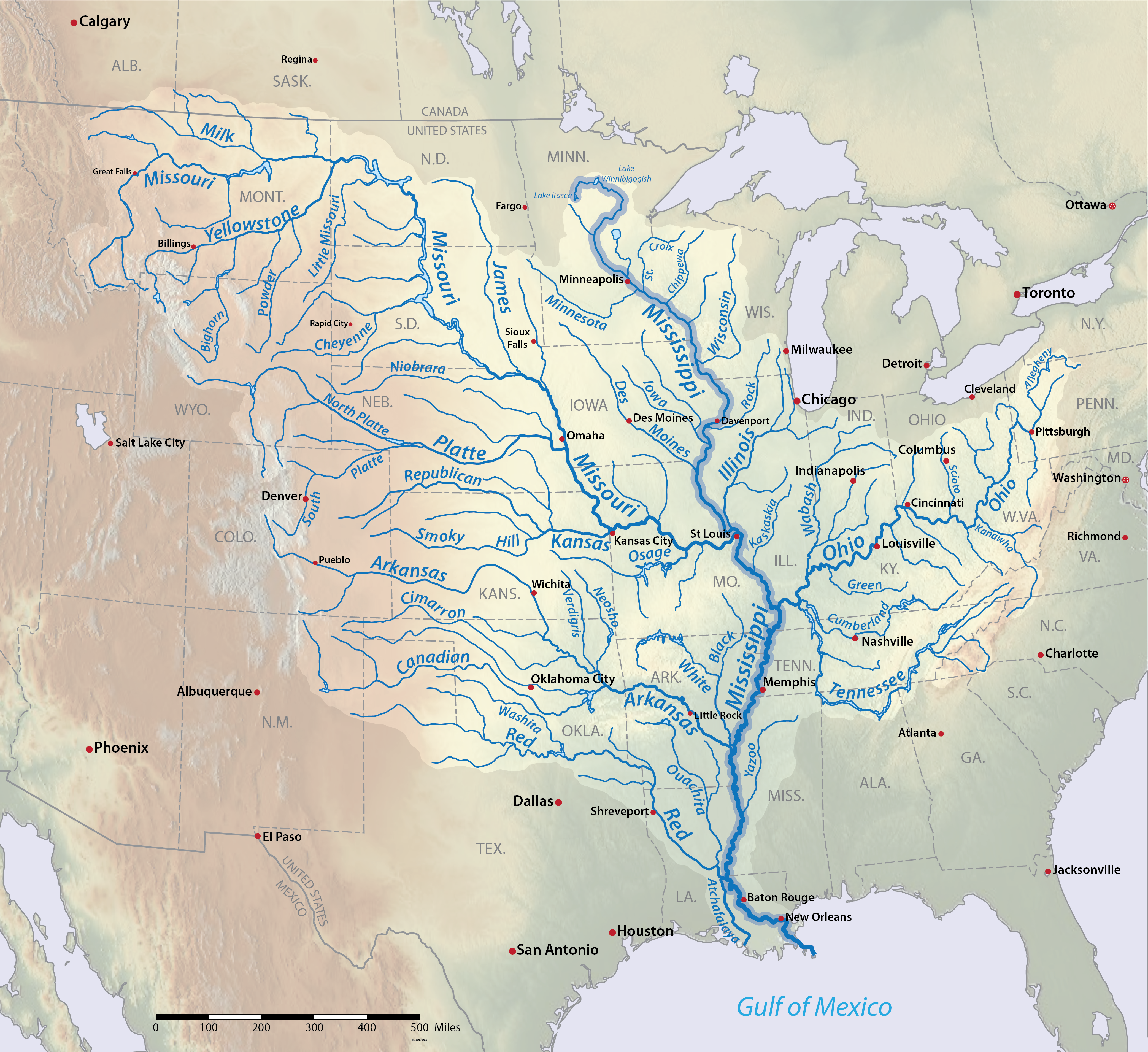

The Gulf of Mexico's eastern, northern, and northwestern shores lie along the US states of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. The US portion of the coastline spans , receiving water from 33 major rivers that drain 31 states and 2 Canadian provinces, and consisting of the coastline from the southern tip of

The Gulf of Mexico's eastern, northern, and northwestern shores lie along the US states of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. The US portion of the coastline spans , receiving water from 33 major rivers that drain 31 states and 2 Canadian provinces, and consisting of the coastline from the southern tip of  The

The  The Gulf of Mexico is an excellent example of a

The Gulf of Mexico is an excellent example of a  The gulf is considered aseismic; however, mild tremors have been recorded throughout history (usually 5.0 or less on the

The gulf is considered aseismic; however, mild tremors have been recorded throughout history (usually 5.0 or less on the

oceanic basin

In hydrology, an oceanic basin (or ocean basin) is anywhere on Earth that is covered by seawater. Geologically, most of the ocean basins are large Structural basin, geologic basins that are below sea level.

Most commonly the ocea ...

and a marginal sea

This is a list of seas of the World Ocean, including marginal seas, areas of water, various gulfs, bights, bays, and straits. In many cases it is a matter of tradition for a body of water to be named a sea or a bay, etc., therefore all these ...

of the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South or the South Coast, is the coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The list of U.S. states and territories by coastline, coastal states th ...

; on the southwest and south by the Mexican states

A Mexican State (), officially the Free and Sovereign State (), is a constituent federative entity of Mexico according to the Constitution of Mexico. Currently there are 31 states, each with its own constitution, government, state governor, a ...

of Tamaulipas

Tamaulipas, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tamaulipas, is a state in Mexico; one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It is divided into 43 municipalities.

It is located in nor ...

, Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

, Tabasco

Tabasco, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tabasco, is one of the Political divisions of Mexico, 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into Municipalities of Tabasco, 17 municipalities and its capital city is Villahermosa.

It i ...

, Campeche

Campeche, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Campeche, is one of the 31 states which, with Mexico City, make up the Administrative divisions of Mexico, 32 federal entities of Mexico. Located in southeast Mexico, it is bordered by the sta ...

, Yucatán

Yucatán, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Yucatán, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, constitute the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 106 separate municipalities, and its capital city is Mérida.

...

, and Quintana Roo

Quintana Roo, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Quintana Roo, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, constitute the 32 administrative divisions of Mexico, federal entities of Mexico. It is divided into municipalities of ...

; and on the southeast by Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

. The coastal areas along the Southern U.S. states of Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, and Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, which border the Gulf on the north, are occasionally referred to as the "Third Coast

"Third Coast" is an American colloquialism used to describe coastal regions distinct from the East Coast of the United States, East Coast and the West Coast of the United States, West Coast of the United States. Generally, the term "Third Coast" ...

" of the United States (in addition to its Atlantic and Pacific coasts), but more often as "the Gulf Coast".

The Gulf of Mexico took shape about 300 million years ago (mya) as a result of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

. The Gulf of Mexico basin is roughly oval and is about wide. Its floor consists of sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock (geology), rock formed by the cementation (geology), cementation of sediments—i.e. particles made of minerals (geological detritus) or organic matter (biological detritus)—that have been accumulated or de ...

s and recent sediments. It is connected to part of the Atlantic Ocean through the Straits of Florida

The Straits of Florida, Florida Straits, or Florida Strait () is a strait located south-southeast of the North American mainland, generally accepted to be between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, and between the Florida Keys (U.S.) an ...

between the U.S. and Cuba, and with the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

via the Yucatán Channel between Mexico and Cuba. Because of its narrow connection to the Atlantic Ocean, the gulf has very small tidal ranges.

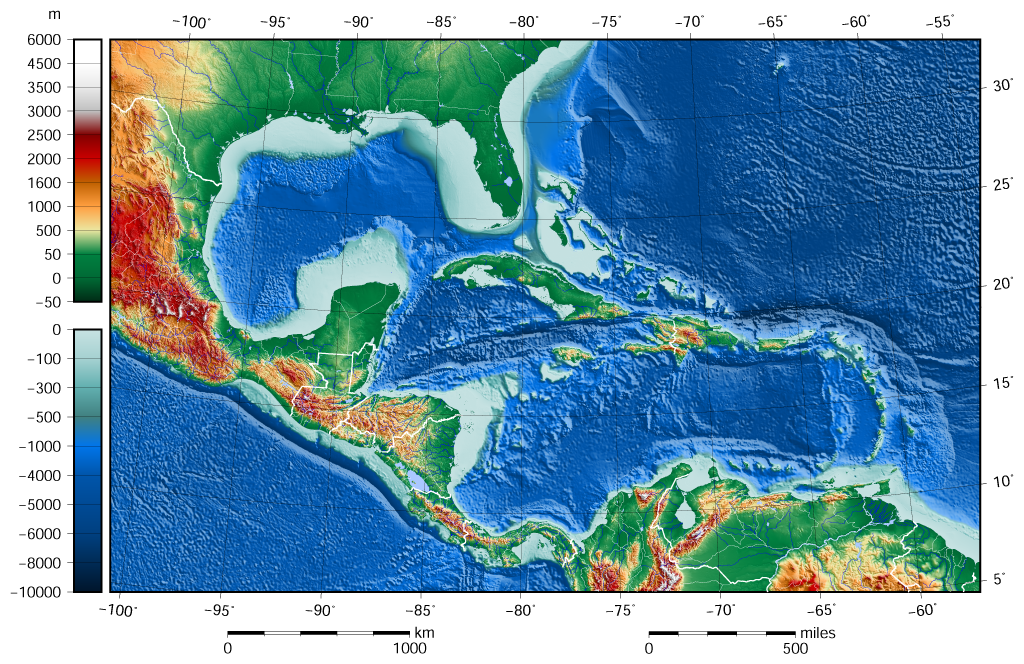

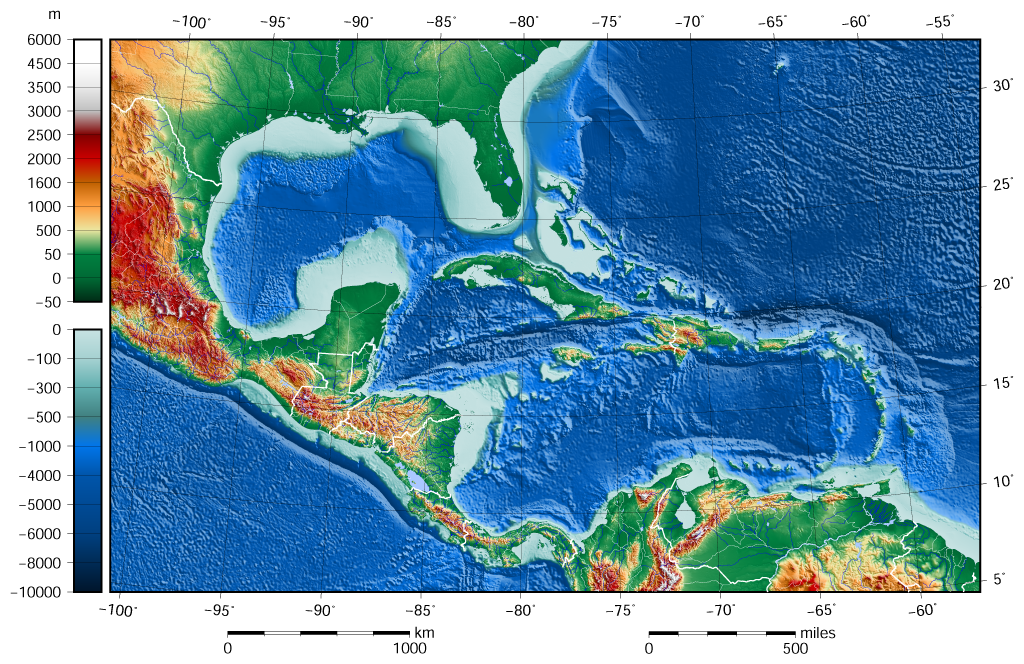

The size of the gulf basin is about . Almost half of the basin consists of shallow continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an islan ...

waters. The volume of water in the basin is roughly (). The gulf is one of the most important offshore petroleum

Offshore drilling is a mechanical process where a wellbore is drilled below the seabed. It is typically carried out in order to explore for and subsequently extract petroleum that lies in rock formations beneath the seabed. Most commonly, the ter ...

production regions in the world, making up 14% of the United States' total production. Moisture from the Gulf of Mexico also contributes to weather across the United States, including severe weather in Tornado Alley

Tornado Alley, also known as Tornado Valley, is a loosely defined location of the central United States and, in the 21st century, Canada where tornadoes are most frequent. The term was first used in 1952 as the title of a research project to st ...

.

Name

As with thename of Mexico

Several hypotheses seek to explain the etymology of the name "Mexico" (''México'' in modern Spanish) which dates, at least, back to 14th century Mesoamerica. Among these are expressions in the Nahuatl language such as (in translation), ''Mexitli ...

, the gulf's name is associated with the ethnonym ''Mexica

The Mexica (Nahuatl: ; singular ) are a Nahuatl-speaking people of the Valley of Mexico who were the rulers of the Triple Alliance, more commonly referred to as the Aztec Empire. The Mexica established Tenochtitlan, a settlement on an island ...

'', which refers to the Nahuatl

Nahuatl ( ; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahuas, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller popul ...

-speaking people of the Valley of Mexico

The Valley of Mexico (; ), sometimes also called Basin of Mexico, is a highlands plateau in central Mexico. Surrounded by mountains and volcanoes, the Valley of Mexico was a centre for several pre-Columbian civilizations including Teotihuacan, ...

better known as the Aztecs

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the ...

. In Aztec religion

The Aztec religion is a polytheistic and monistic pantheism in which the Nahua concept of '' teotl'' was construed as the supreme god Ometeotl, as well as a diverse pantheon of lesser gods and manifestations of nature. The popular religion te ...

, the gulf was called , or 'House of Chalchiuhtlicue

Chalchiuhtlicue (from ''chālchihuitl'' "jade" and ''cuēitl'' "skirt") (also spelled Chalciuhtlicue, Chalchiuhcueye, or Chalcihuitlicue) ("She of the Jade Skirt") is an Aztec deity of water, rivers, seas, streams, storms, and baptism. Chalch ...

', after the deity of the seas. Believing that the sea and sky merged beyond the horizon, they called the seas , meaning 'sky water', contrasting them with finite, landlocked bodies of water, such as lakes. The Maya civilization

The Maya civilization () was a Mesoamerican civilization that existed from antiquity to the early modern period. It is known by its ancient temples and glyphs (script). The Maya script is the most sophisticated and highly developed writin ...

, which used the gulf as a major trade route, likely called the gulf , meaning 'great water'.

Up to 1530, European maps depicted the gulf, though left it unlabeled. Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca (December 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions o ...

called it "Sea of the North" () in his dispatches, while other Spanish explorers called it the "Gulf of Florida" () or "Gulf of Cortés" (). A 1584 map by Abraham Ortelius

Abraham Ortelius (; also Ortels, Orthellius, Wortels; 4 or 14 April 152728 June 1598) was a cartographer, geographer, and cosmographer from Antwerp in the Spanish Netherlands. He is recognized as the creator of the list of atlases, first modern ...

also labeled it as the "Sea of the North" (). Other early European maps called it the "Gulf of St. Michael" (), "Gulf of Yucatán

Yucatán, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Yucatán, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, constitute the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 106 separate municipalities, and its capital city is Mérida.

...

" (), "Yucatán Sea" (), "Great Antillean Gulf" (), "Cathay

Cathay ( ) is a historical name for China that was used in Europe. During the early modern period, the term ''Cathay'' initially evolved as a term referring to what is now Northern China, completely separate and distinct from ''China'', which w ...

an Sea" (), or "Gulf of New Spain" (). At one point, New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

encircled the gulf, with the Spanish Main

During the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Spanish Main was the collective term used by English speakers for the parts of the Spanish Empire that were on the mainland of the Americas and had coastlines on the Caribbean Sea or Gulf of ...

extending into what later became Mexico and the southeastern United States.

The name "Gulf of Mexico" (; , later ) first appeared on a world map in 1550 and a historical account in 1552. As with other large bodies of water, Europeans named the gulf after Mexico, land of the Mexica, because mariners needed to cross the gulf to reach that destination. This name has been the most common name since the mid-17th century, when it was still considered a Spanish sea. French Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

used this name as early as 1672. In the 18th century, Spanish admiralty charts similarly labeled the gulf as "Mexican Cove" or "Mexican Sound" ( or ). Until the Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

broke away from Mexico in 1836, Mexico's coastal boundary extended eastward along the gulf to present-day Louisiana.

Among the other languages of Mexico

The Constitution of Mexico does not declare an official language; however, Spanish is the '' de facto'' national language spoken by over 99% of the population making it the largest Spanish speaking country in the world. Due to the cultural in ...

, the gulf is known as in Nahuatl

Nahuatl ( ; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahuas, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller popul ...

, in Yucatec Maya

Yucatec Maya ( ; referred to by its speakers as or ) is a Mayan languages, Mayan language spoken in the Yucatán Peninsula, including part of northern Belize. There is also a significant diasporic community of Yucatec Maya speakers in San Fra ...

, and in Tzotzil.

On January 20, 2025, United States president Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

signed an executive order directing U.S. federal agencies to adopt the name Gulf of America for the gulf waters bounded by the U.S. Although there is no formal protocol on the general naming of international waters

The terms international waters or transboundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water (or their drainage basins) transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed region ...

, ''Gulf of Mexico'' is officially recognized by the International Hydrographic Organization

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) (French: ''Organisation Hydrographique Internationale'') is an intergovernmental organization representing hydrography. the IHO comprised 102 member states.

A principal aim of the IHO is to ...

, which seeks to standardize the names of international maritime features for certain purposes and counts all three countries adjacent to the gulf as member states. Major online map platforms and several U.S.-based media outlets voluntarily adopted the change. Mexican president Claudia Sheinbaum

Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo (born 24 June 1962) is a Mexican politician, energy and climate change scientist, and academic who has served as the 66th president of Mexico since 2024. She is the List of elected and appointed female heads of state and ...

objected to the declaration of a name change.

Extent

International Hydrographic Organization

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) (French: ''Organisation Hydrographique Internationale'') is an intergovernmental organization representing hydrography. the IHO comprised 102 member states.

A principal aim of the IHO is to ...

publication ''Limits of Oceans and Seas

''Limits of Oceans and Seas'' ( or , S-23) is a special publication of the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) defining the names and borders of the oceans and seas. The publication serves as an international standard for hydrographic ...

'' defines the southeast limit of the Gulf of Mexico as:

A line joiningCape Catoche Cabo Catoche or Cape Catoche, in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, is the northernmost point on the Yucatán Peninsula. It lies in the municipality of Isla Mujeres, about north of the city of Cancún. According to the International Hydrograph ...Light Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...() with theLight Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...on Cape San Antonio in Cuba, through this island to the meridian of 83°W and to the Northward along this meridian to the latitude of the South point of theDry Tortugas Dry Tortugas National Park is a national park of the United States located about west of Key West in the Gulf of Mexico, in the United States. The park preserves Fort Jefferson and the several Dry Tortugas islands, the westernmost and most iso ...(24°35′N), along this parallel Eastward to Rebecca Shoal (82°35′W) thence through the shoals andFlorida Keys The Florida Keys are a coral island, coral cay archipelago off the southern coast of Florida, forming the southernmost part of the continental United States. They begin at the southeastern coast of the Florida peninsula, about south of Miami a ...to the mainland at the eastern end ofFlorida Bay Florida Bay is the bay located between the southern end of the Florida mainland (the Everglades, Florida Everglades) and the Florida Keys in the United States. It is a large, shallow estuary that while connected to the Gulf of Mexico, has limited ...and all the narrow waters between theDry Tortugas Dry Tortugas National Park is a national park of the United States located about west of Key West in the Gulf of Mexico, in the United States. The park preserves Fort Jefferson and the several Dry Tortugas islands, the westernmost and most iso ...and the mainland being considered to be within the Gulf.

Population

The total population of the five U.S. states facing the gulf is 67 million people. Of these, a total of 15.8 million people live in the Gulf Coastal Region, in counties directly bordering the gulf. The six Mexican states that face the gulf have a total population of 19.1 million people. Three provinces of northwestCuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, including Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.drilling rig

A drilling rig is an integrated system that Drilling, drills wells, such as oil or water wells, or holes for piling and other construction purposes, into the earth's subsurface. Drilling rigs can be massive structures housing equipment used to ...

s in the gulf hosted a temporary population of more than 10,000 workers on any given day, who were rotated on a weekly staggered schedule. Increasing automation later led to a decline in the offshore worker population.

Geology

The consensus among geologists is that before the lateTriassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

, the Gulf of Mexico did not exist. Before the late Triassic, the area consisted of dry land, which included continental crust

Continental crust is the layer of igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks that forms the geological continents and the areas of shallow seabed close to their shores, known as '' continental shelves''. This layer is sometimes called '' si ...

that now underlies Yucatán

Yucatán, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Yucatán, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, constitute the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 106 separate municipalities, and its capital city is Mérida.

...

, within the middle of the supercontinent Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea ( ) was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous period approximately 335 mi ...

. This land lay south of a continuous mountain range that extended from north-central Mexico, through the Marathon Uplift

The Marathon Uplift is a Paleogene-age domal uplift, approximately in diameter, in southwest Texas. The Marathon Basin was created by erosion of Cretaceous and younger strata from the crest of the uplift.McBride, E.F. and Hayward, O.T., 1988''Geo ...

in west Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

and the Ouachita Mountains

The Ouachita Mountains (), simply referred to as the Ouachitas, are a mountain range in western Arkansas and southeastern Oklahoma. They are formed by a thick succession of highly deformed Paleozoic strata constituting the Ouachita Fold and Thru ...

of Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

, and to Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

where it linked directly to the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

. It was created by the collision of continental plates that formed Pangaea. As interpreted by Roy Van Arsdale and Randel T. Cox, this mountain range was breached in the late Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

by the formation of the Mississippi Embayment

The Mississippi embayment is a physiographic feature in the south-central United States, part of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain. It is essentially a northward continuation of the fluvial sediments of the Mississippi River Delta to its conflu ...

.

The

The rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics. Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-graben ...

ing that created the basin was associated with zones of weakness within Pangaea, including sutures where the Laurentia

Laurentia or the North American craton is a large continental craton that forms the Geology of North America, ancient geological core of North America. Many times in its past, Laurentia has been a separate continent, as it is now in the form of ...

, South American

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

, and African plates collided to create it. First, there was a late Triassic–early Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

phase of rifting during which rift valley

A rift valley is a linear shaped lowland between several highlands or mountain ranges produced by the action of a geologic rift. Rifts are formed as a result of the pulling apart of the lithosphere due to extensional tectonics. The linear ...

s formed and filled with continental red beds

Red beds (or redbeds) are sedimentary rocks, typically consisting of sandstone, siltstone, and shale, that are predominantly red in color due to the presence of ferric oxides. Frequently, these red-colored sedimentary strata locally contain t ...

. Second, the continental crust was stretched and thinned as rifting progressed through early and middle Jurassic times. This thinning created a broad zone of transitional crust, which displays modest and uneven thinning with block faulting and a broad zone of uniformly thinned transitional crust, which is half the typical thickness of continental crust. At this time, rifting first created a connection to the Pacific Ocean across central Mexico and later eastwards to the Atlantic Ocean. This flooded the opening basin to create an enclosed marginal sea. The subsiding transitional crust was blanketed by the widespread deposition of Louann Salt and associated anhydrite

Anhydrite, or anhydrous calcium sulfate, is a mineral with the chemical formula CaSO4. It is in the orthorhombic crystal system, with three directions of perfect cleavage parallel to the three planes of symmetry. It is not isomorphous with the ...

evaporite

An evaporite () is a water- soluble sedimentary mineral deposit that results from concentration and crystallization by evaporation from an aqueous solution. There are two types of evaporite deposits: marine, which can also be described as oce ...

s. During the late Jurassic, continued rifting widened the basin and progressed to the point that seafloor spreading

Seafloor spreading, or seafloor spread, is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener ...

and formation of oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramaf ...

occurred. At this point, sufficient circulation with the Atlantic Ocean was established that the deposition of Louann Salt ceased. Seafloor spreading stopped at the end of the Jurassic, about 145–150 mya.During the late Jurassic through early Cretaceous, the basin experienced a period of cooling and subsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope mov ...

of the crust underlying it. The subsidence resulted from crustal stretching, cooling, and loading. Initially, the crustal stretching and cooling combination caused about of tectonic subsidence of the central thin transitional and oceanic crust. The basin expanded and deepened because subsidence occurred faster than sediment could fill it.

Later, loading of the crust within the basin and adjacent coastal plain by the accumulation of kilometers of sediments during the rest of the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

and all of the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic Era ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterized by the dominance of mammals, insects, birds and angiosperms (flowering plants). It is the latest of three g ...

further depressed the underlying crust to its current position about below sea level. Particularly during the Cenozoic, a time of relative stability for the coastal zones, thick clastic wedges built out the continental shelf along the northwestern and northern margins of the basin. To the east, the stable Florida Platform was not covered by the sea until the latest Jurassic or the beginning of Cretaceous time. The Yucatán Platform was emergent until the mid-Cretaceous. After both platforms were submerged, the formation of

To the east, the stable Florida Platform was not covered by the sea until the latest Jurassic or the beginning of Cretaceous time. The Yucatán Platform was emergent until the mid-Cretaceous. After both platforms were submerged, the formation of carbonates

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid, (), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word "carbonate" may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate group . ...

and evaporites has delineated the geologic history of these two stable areas. Most of the basin was rimmed during the early Cretaceous by carbonate platforms, and its western flank was involved during the latest Cretaceous and early Paleogene

The Paleogene Period ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Neogene Period Ma. It is the fir ...

periods in a compressive deformation episode, the Laramide Orogeny

The Laramide orogeny was a time period of mountain building in western North America, which started in the Late Cretaceous, 80 to 70 million years ago, and ended 55 to 35 million years ago. The exact duration and ages of beginning and end of the o ...

, which created the Sierra Madre Oriental

The Sierra Madre Oriental () is a mountain range in northeastern Mexico. The Sierra Madre Oriental is part of the American Cordillera, a chain of mountain ranges (cordillera) that consists of an almost continuous sequence of mountain ranges that ...

of eastern Mexico.

The Gulf of Mexico is 41% continental slope

A continental margin is the outer edge of continental crust abutting oceanic crust under coastal waters. It is one of the three major zones of the ocean floor, the other two being deep-ocean basins and mid-ocean ridges.

The continental margi ...

, 32% continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an islan ...

, and 24% abyssal plain

An abyssal plain is an underwater plain on the deep ocean floor, usually found at depths between . Lying generally between the foot of a continental rise and a mid-ocean ridge, abyssal plains cover more than 50% of the Earth's surface. They ...

with the greatest depth of 12,467 feet in the Sigsbee Deep. Seven main areas are given as:

* Gulf of Mexico basin contains the Sigsbee Deep and can be further divided into the continental rise, the Sigsbee Abyssal Plain, and the Mississippi Cone.

* Northeast Gulf of Mexico extends from a point east of the Mississippi River Delta near Biloxi

Biloxi ( ; ) is a city in Harrison County, Mississippi, United States. It lies on the Gulf Coast of the United States, Gulf Coast in southern Mississippi, bordering the city of Gulfport, Mississippi, Gulfport to its west. The adjacent cities ar ...

to the eastern side of Apalachee Bay

Apalachee Bay is a bay in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico occupying an indentation of the Florida coast to the west of where the Florida peninsula joins the United States mainland. It is bordered by Taylor, Jefferson, Wakulla, and Franklin ...

.

* South Florida Continental Shelf and Slope extends along the coast from Apalachee Bay to the Straits of Florida

The Straits of Florida, Florida Straits, or Florida Strait () is a strait located south-southeast of the North American mainland, generally accepted to be between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, and between the Florida Keys (U.S.) an ...

and includes the Florida Keys and Dry Tortugas

Dry Tortugas National Park is a national park of the United States located about west of Key West in the Gulf of Mexico, in the United States. The park preserves Fort Jefferson and the several Dry Tortugas islands, the westernmost and most iso ...

.

* Campeche Bank extends from the Yucatán Straits in the east to the Tabasco

Tabasco, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tabasco, is one of the Political divisions of Mexico, 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into Municipalities of Tabasco, 17 municipalities and its capital city is Villahermosa.

It i ...

– Campeche Basin in the west and includes Arrecife Alacran.

* Bay of Campeche

The Bay of Campeche (), or Campeche Sound, is a bight in the southern area of the Gulf of Mexico, forming the north side of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. It is surrounded on three sides by the Mexican states of Campeche, Tabasco and Veracruz. The ...

is a bight extending from the western edge of Campeche Bank to the offshore regions east of Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

.

* Western Gulf of Mexico is located between Veracruz to the south and the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( or ) in the United States or the Río Bravo (del Norte) in Mexico (), also known as Tó Ba'áadi in Navajo language, Navajo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the Southwestern United States a ...

to the north.

* Northwest Gulf of Mexico extends from Alabama to the Rio Grande.

Brine pools

A number of brine pools, sometimes called brine lakes, are known on the seafloor of the northern half of the Gulf of Mexico. Brine pools in the Gulf of Mexico range from just across to long.Brine

Brine (or briny water) is a high-concentration solution of salt (typically sodium chloride or calcium chloride) in water. In diverse contexts, ''brine'' may refer to the salt solutions ranging from about 3.5% (a typical concentration of seawat ...

is produced wherever the water of the Gulf comes in contact with the Louann Salt, a evaporite

An evaporite () is a water- soluble sedimentary mineral deposit that results from concentration and crystallization by evaporation from an aqueous solution. There are two types of evaporite deposits: marine, which can also be described as oce ...

formation from the Jurassic period, along faults or in unconsolidated sediments. The Louann Salt extends under most of the continental shelf around the northern part of the Gulf from west of Florida to Texas. Under the pressure of overlaying sediments, the salt deforms and migrates, a process known as salt tectonics

upright=1.7

Salt tectonics, or halokinesis, or halotectonics, is concerned with the geometries and processes associated with the presence of significant thicknesses of evaporites containing rock salt within a stratigraphic sequence of rocks. This ...

. Masses of salt may rise through overlaying sediments to form salt domes, or may be extruded along the Sigsbee Escarpment where the slope of the continental shelf exposes lower laying stata.

The brines usually exceed 200 parts-per-thousand (ppt) of salt and are 25% or more denser than most seawater (average 35 ppt). The density difference inhibits mixing of the brine with other sea water, and the brine flows downslope and gathers in depressions in the gulf floor. Hydrocarbons and gas hydrates rising from salt diapir

A diapir (; , ) is a type of intrusion in which a more mobile and ductilely deformable material is forced into brittle overlying rocks. Depending on the tectonic environment, diapirs can range from idealized mushroom-shaped Rayleigh–Taylor ...

s may cause doming of the gulf floor, with the gas sometimes erupting strongly enough to leave a depression in the gulf floor surrounded by a rim, where brine may pool. The East Flower Garden Bank brine pool is in a crater formed by the collapsed cap of a salt dome. The circular pool covers with a maximum depth of , and is beneath the surface of the Gulf. It is anoxic

Anoxia means a total depletion in the level of oxygen, an extreme form of hypoxia or "low oxygen". The terms anoxia and hypoxia are used in various contexts:

* Anoxic waters, sea water, fresh water or groundwater that are depleted of dissolved ox ...

and contain quantities of hydrogen sulfide and methane.

The brine pool known as GB425, which is deep, is fed by a mud volcano

A mud volcano or mud dome is a landform created by the eruption of mud or Slurry, slurries, water and gases. Several geological processes may cause the formation of mud volcanoes. Mud volcanoes are not true Igneous rock, igneous volcanoes as th ...

. The temperature at the surface of the pool can vary from , and is on average warmer than normal bottom temperatures. The brine pool known as GC233 is at a depth similar to that of GB425, deep. The pool sits in a depression at the top of a mound and covers about . While GC233 has a lower inflow of brine than GB425 and a temperature about below that of GB425, the two pools share some similarities, such as a salinity of about 130 ppt, low sulfides, almost no sulfates, and high concentrations of hydrocarbons.

The Orca Basin is deep, and covers about with a maximum depth of . The large size is the result of the merger of several salt domes. Salinity in the pool increases gradually over a depth of , and reaches 300 ppt at depth, with zero dissolved oxygen.

A brine pool was discovered in 2014 on the sea floor at a depth of with a circumference of and depth of , which is four to five times saltier than the surrounding water. The site cannot sustain any kind of life other than bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

s with a symbiotic relationship

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biolo ...

, tube worms, and certain kinds of shrimp

A shrimp (: shrimp (American English, US) or shrimps (British English, UK)) is a crustacean with an elongated body and a primarily Aquatic locomotion, swimming mode of locomotion – typically Decapods belonging to the Caridea or Dendrobranchi ...

. It has been called the "Jacuzzi of Despair" because it is warmer at compared to the surrounding water at .

Hydrology

Circulation of water in and through the Gulf is part of the larger circulation patterns of the Atlantic Ocean. Water flows into the Gulf from the Caribbean Sea through the Yucatan Channel as the Yucatan Current, and exits to the North Atlanic Ocean through theFlorida Straits

The Straits of Florida, Florida Straits, or Florida Strait () is a strait located south-southeast of the North American mainland, generally accepted to be between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, and between the Florida Keys (U.S.) ...

as the Florida Current

The Florida Current is a thermal ocean current that flows from the Straits of Florida around the Florida Peninsula and along the southeastern coast of the United States before joining the Gulf Stream Current near Cape Hatteras. Its contributing cu ...

, which becomes the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude (North Carolin ...

. Movement through the two straits is confined to the upper layers of ocean water, as the Yucatan Strait has a maximum depth of only , while the Florida Straits has a maximum depth of only .

The Yucatan Current fills most of the Yucatan Channel to a depth of up to , with a maximum flow of per second. There are weaker countercurrents along the coasts of Cuba and Yucatan and below the main current. The average volumetric flow rate

In physics and engineering, in particular fluid dynamics, the volumetric flow rate (also known as volume flow rate, or volume velocity) is the volume of fluid which passes per unit time; usually it is represented by the symbol (sometimes \do ...

through the Yucatan Channel varied between 15.8 and 28.1 Sverdrup

In oceanography, the sverdrup (symbol: Sv) is a non- SI metric unit of volumetric flow rate, with equal to . It is equivalent to the SI derived unit cubic hectometer per second (symbol: hm3/s or hm3⋅s−1): is equal to . It is used almost ...

s ( hectometers per second) from 1999 to 2013. The Florida Current fills all of the Florida Straits (at approximately 81°W, between the lower Florida Keys

The Florida Keys are a coral island, coral cay archipelago off the southern coast of Florida, forming the southernmost part of the continental United States. They begin at the southeastern coast of the Florida peninsula, about south of Miami a ...

and Cuba) to a depth of , with a maximum flow of per second. The average volumetric flow rate

In physics and engineering, in particular fluid dynamics, the volumetric flow rate (also known as volume flow rate, or volume velocity) is the volume of fluid which passes per unit time; usually it is represented by the symbol (sometimes \do ...

through the Florida Straits varied between 27.2 and 27.9 Sverdrups.

The Yucatan Current is connected to the Florida Current by an anti-cyclonic (clockwise) loop of variable size, the Loop Current

Mesh analysis (or the mesh current method) is a circuit analysis method for planar circuits; planar circuits are circuits that can be drawn on a plane surface with no wires crossing each other. A more general technique, called loop analysis ...

. The Loop Current may extend into the northeastern part of the Gulf, and may flow over the continental shelf along the west coast of the Florida peninsula. The Loop Current is as strong as the Gulf Stream and dominates the Gulf. Anti-cyclonic and cyclonic (anti-clockwise) rings or eddie's are shed from the Loop Current and move into the western Gulf. Cyclonic and anti-cyclonic eddies form pairs, and such pairs of eddie's often dominate circulation in the western Gulf.

The Loop Current is up to in diameter and is surrounded by small cyclonic (anti-clockwise) eddies. Large warm-core rings or eddies are shed off the Loop Current at irregular intervals. The Loop Current can be seen in satellite images using both sea surface temperature

Sea surface temperature (or ocean surface temperature) is the ocean temperature, temperature of ocean water close to the surface. The exact meaning of ''surface'' varies in the literature and in practice. It is usually between and below the sea ...

s and Sea surface height

Ocean surface topography or sea surface topography, also called ocean dynamic topography, are highs and lows on the ocean surface, similar to the hills and valleys of Earth's land surface depicted on a topographic map.

These variations are exp ...

. On the east side of the Gulf, a weak countercurrent flows north along the continental slope

A continental margin is the outer edge of continental crust abutting oceanic crust under coastal waters. It is one of the three major zones of the ocean floor, the other two being deep-ocean basins and mid-ocean ridges.

The continental margi ...

of the Florida peninsula. In the Northeast corner of the Gulf there is a weak cyclonic circulation over the continental shelf. The strength of this circulation is inversely proportional to how far north the Loop Current extends.

The Loop Current is part of the North Atlantic Gyre

The North Atlantic Gyre of the Atlantic Ocean is one of five great oceanic gyres. It is a circular ocean current, with offshoot eddies and sub-gyres, across the North Atlantic from the Intertropical Convergence Zone (calms or doldrums) to the pa ...

, a ocean current

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of seawater generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth contours, sh ...

circulation that includes the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude (North Carolin ...

, North Atlantic Current

The North Atlantic Current (NAC), also known as North Atlantic Drift and North Atlantic Sea Movement, is a powerful warm western boundary current within the Atlantic Ocean that extends the Gulf Stream northeastward.

Characteristics

The NAC ...

, Canary Current

The Canary Current is a wind-driven surface current that is part of the North Atlantic Gyre. This eastern boundary current branches south from the North Atlantic Current and flows southwest about as far as Senegal where it turns west and later jo ...

, and North Equatorial Current

The North Equatorial Current (NEC) is a westward wind-driven current mostly located near the equator, but the location varies from different oceans. The NEC in the Pacific and the Atlantic is about 5°-20°N, while the NEC in the Indian Ocean is v ...

. The eddies shed by the Loop Current spread though the Gulf, affecting the circulation in almost all parts of the Gulf. The creation of the eddies is a variable and often complex process, influenced in part by how far the Loop Currents has penetrated into the Gulf. Eddies shed by the Loop Current sometimes reattach to the Loop Current. Eddies surrounding the Loop Current react interactively with it, affecting both the penetration of the loop into the Gulf, and the size and number of eddies shed by the loop.

Rings or eddies shed from the Loop Current may be up to in diameter and deep. The outer currents in the ring may flow at up to , while the rings as a whole move westward at about .

The water flowing into the Gulf from the Caribbean Sea is not homogenous. About 40% is from the South Atlantic Ocean, and is warmer and fresher than the rest of the water. The South Atlantic component is distinguishable in the upper of the left hand and central parts of the Florida Current. Another component in the deeper part of the current is Antarctic intermediate water. The rest of the water carried into the Gulf consists of various masses from the North Atlantic.

History

Pre-Columbian

As early as theMaya civilization

The Maya civilization () was a Mesoamerican civilization that existed from antiquity to the early modern period. It is known by its ancient temples and glyphs (script). The Maya script is the most sophisticated and highly developed writin ...

, the Gulf of Mexico was used as a trade route off the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula ( , ; ) is a large peninsula in southeast Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north and west of the peninsula from the C ...

and present-day Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

.

Spanish exploration

Although Europeans credited the Spanish voyage ofChristopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

with the discovery of the Americas, the ships in his four voyages did not reach the Gulf of Mexico. Instead, the Spanish sailed into the Caribbean around Cuba and Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ) is an island between Geography of Cuba, Cuba and Geography of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the second-largest by List of C ...

. The first alleged European exploration of the Gulf of Mexico was by Amerigo Vespucci

Amerigo Vespucci ( , ; 9 March 1454 – 22 February 1512) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Florence for whom "Naming of the Americas, America" is named.

Vespucci participated in at least two voyages of the A ...

in 1497. Vespucci is purported to have followed the coastal land mass of Central America

Central America is a subregion of North America. Its political boundaries are defined as bordering Mexico to the north, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. Central America is usually ...

before returning to the Atlantic Ocean via the Straits of Florida between Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

and Cuba. However, this first voyage of 1497 is widely disputed. Many historians doubt that it took place as described. In his letters, Vespucci described this trip, and once Juan de la Cosa

Juan de la Cosa (c. 1450 – 28 February 1510) was a Basque navigator and cartographer, known for designing the earliest European world map which incorporated the territories of the Americas discovered in the 15th century.

De la Cosa was the o ...

returned to Spain, a famous world map was produced.

In 1506, Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca (December 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions o ...

participated in the conquest of Hispaniola and Cuba, receiving a large estate of land and enslaving Indigenous people for his efforts. In 1510, he accompanied Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, an aide to the governor of Hispaniola, on his expedition to conquer Cuba. In 1518, Velázquez put him in command of an expedition to explore and secure the interior of Mexico for colonization.

In 1517, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba discovered the Yucatán Peninsula. This was the first European encounter with an advanced civilization in the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

, with solidly built buildings and complex social structures which they found comparable to those of the Old World

The "Old World" () is a term for Afro-Eurasia coined by Europeans after 1493, when they became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia in the Eastern Hemisphere, previously ...

. They also had reason to expect that this new land would have gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

. All of this encouraged two further expeditions, the first in 1518 under the command of Juan de Grijalva

Juan de Grijalva (; c. 1490 – 21 January 1527) was a Spanish conquistador, and a relative of Diego Velázquez.Diaz de Castillo, Bernal. 1963, The Conquest of New Spain, London: Penguin Books, He went to Hispaniola in 1508 and to Cuba in 1511. ...

, and the second in 1519 under the command of Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca (December 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions o ...

, which led to the Spanish exploration, military invasion, and ultimately settlement and colonization known as the Conquest of Mexico

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire was a pivotal event in the history of the Americas, marked by the collision of the Aztec Triple Alliance and the Spanish Empire. Taking place between 1519 and 1521, this event saw the Spanish conquista ...

. Hernández did not live to see the continuation of his work: he died in 1517, the year of his expedition, as the result of the injuries and the extreme thirst suffered during the voyage, and disappointed in the knowledge that Velázquez had given precedence to Grijalva as the captain of the next expedition to Yucatán.

In 1523, a treasure ship was wrecked en route at Padre Island

Padre Island is the largest of the Texas barrier islands and the world's longest barrier island. The island is located along Texas's southern coast of the Gulf of Mexico and is noted for its white sandy beaches. Meaning ''father'' in Spanish, ...

, Texas. When word of the disaster reached Mexico City, the viceroy requested a rescue fleet and sent Ángel de Villafañe

Ángel de Villafañe (b. c. 1504) was a Spanish conquistador of Florida, Mexico, and Guatemala, and was an explorer, expedition leader, and ship captain (with Hernán Cortés), who worked with many 16th-century settlements and shipwrecks along t ...

from Mexico City, marching overland to find the treasure-laden vessels. Villafañe traveled to Pánuco and hired a ship to transport him to the site, which that community had already visited. He arrived in time to greet García de Escalante Alvarado (a nephew of Pedro de Alvarado

Pedro de Alvarado (; 1485 – 4 July 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, ''conquistador'', ''adelantado,'' governor and Captaincy General of Guatemala, captain general of Guatemala.Lovell, Lutz and Swezey 1984, p. 461. He participated in the c ...

), commander of the salvage operation, when Alvarado arrived by sea on July 22, 1554. The team laboured until September 12 to salvage the Padre Island treasure. This loss, combined with other ship disasters around the Gulf of Mexico, led to a plan for establishing a settlement on the northern Gulf Coast to protect shipping and rescue castaways more quickly. As a result, the expedition of Tristán de Luna y Arellano

Tristán de Luna y Arellano (1510 – September 16, 1573) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador of the 16th century.Herbert Ingram Priestley, Tristan de Luna: Conquistador of the Old South: A Study of Spanish Imperial Strategy (1936). http://pa ...

was sent and landed at Pensacola Bay

Pensacola Bay is a bay located in the northwestern part of Florida, United States, known as the Florida Panhandle.

The bay, an inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, is located in Escambia County and Santa Rosa County, adjacent to the city of Pensac ...

on August 15, 1559.

On December 11, 1526, Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

granted Pánfilo de Narváez

Pánfilo de Narváez (; born 1470 or 1478, died 1528) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' and soldier in the Americas. Born in Spain, he first sailed to the island of Jamaica (then Santiago) in 1510 as a soldier. Pánfilo participated in the conque ...

a licence to establish colonial settlements along the present-day Gulf Coast of the United States, known as the Narváez expedition

The Narváez expedition was a Spanish expedition started in 1527 that was intended to explore Florida and establish colonial settlements. The expedition was initially led by Pánfilo de Narváez, who died in 1528. Many more people died as the e ...

. The contract gave him one year to gather an army, leave Spain, be large enough to found at least two towns of 100 people each, and garrison two more fortresses anywhere along the coast. On April 7, 1528, they spotted land north of what is now Tampa Bay

Tampa Bay is a large natural harbor and shallow estuary connected to the Gulf of Mexico on the west-central coast of Florida, comprising Hillsborough Bay, McKay Bay, Old Tampa Bay, Middle Tampa Bay, and Lower Tampa Bay. The largest freshwater i ...

. They turned south and traveled for two days, looking for a great harbour the master pilot Miruelo knew of. Sometime during these two days, one of the five remaining ships was lost on the rugged coast, but nothing else is known.

In 1697, French sailor Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

was chosen by the Minister of Marine to lead an expedition to rediscover the mouth of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

and to settle Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

, which French explorer Robert Cavelier de La Salle had named. The English coveted this region, however in 1682 it was named to honour King Louis XIV of France. D'Iberville's fleet sailed from Brest on October 24, 1698, reaching Santa Rosa Island near Pensacola

Pensacola ( ) is a city in the Florida panhandle in the United States. It is the county seat and only city in Escambia County. The population was 54,312 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Pensacola metropolitan area, which ha ...

; he sailed from there to Mobile Bay

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. T ...

and explored Massacre Island. He anchored between Cat Island and Ship Island. On February 13, 1689, he went to ashore at what is now Biloxi

Biloxi ( ; ) is a city in Harrison County, Mississippi, United States. It lies on the Gulf Coast of the United States, Gulf Coast in southern Mississippi, bordering the city of Gulfport, Mississippi, Gulfport to its west. The adjacent cities ar ...

, with his teenage brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville (; ; February 23, 1680 – March 7, 1767), also known as Sieur de Bienville, was a French-Canadian colonial administrator in New France. Born in Montreal, he was an early governor of French Louisiana, appo ...

, and completed Fort Maurepas on the northeast side of the Bay of Biloxi on May 1. Three days later, d'Iberville sailed for France leaving his brother Jean-Baptiste as second in command.

The first permanent settlement, Fort Maurepas (now Ocean Springs, Mississippi

Ocean Springs is a city in Jackson County, Mississippi, United States, approximately east of Biloxi, Mississippi, Biloxi and west of Gautier, Mississippi, Gautier. It is part of the Pascagoula metropolitan area. The population was 18,429 at th ...

), was founded in 1699 by d'Iberville. By then the French had also built a small fort at the mouth of the Mississippi at a settlement they named La Balise (or La Balize), "seamark

A sea mark, also seamark and navigation mark, is a form of aid to navigation and pilotage that identifies the approximate position of a maritime channel, hazard, or administrative area to allow boats, ships, and seaplanes to navigate safel ...

" in French.

Geography

The Gulf of Mexico's eastern, northern, and northwestern shores lie along the US states of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. The US portion of the coastline spans , receiving water from 33 major rivers that drain 31 states and 2 Canadian provinces, and consisting of the coastline from the southern tip of

The Gulf of Mexico's eastern, northern, and northwestern shores lie along the US states of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. The US portion of the coastline spans , receiving water from 33 major rivers that drain 31 states and 2 Canadian provinces, and consisting of the coastline from the southern tip of Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

and the Florida Keys

The Florida Keys are a coral island, coral cay archipelago off the southern coast of Florida, forming the southernmost part of the continental United States. They begin at the southeastern coast of the Florida peninsula, about south of Miami a ...

to the U.S.–Mexican border between Brownsville, Texas

Brownsville ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the county seat of Cameron County, Texas, Cameron County, located on the western Gulf Coast in South Texas, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border, border with Matamoros, Tamaulipas ...

, and Matamoros, Tamaulipas

Matamoros, officially known as Heroica Matamoros, is a city in the northeastern Mexican state of Tamaulipas, and the municipal seat of the homonymous municipality. It is on the southern bank of the Rio Grande, directly across the border from Bro ...

. The Mexican coastline spans , consisting of the coastline from the US border to the Cabo Catoche

Cabo Catoche or Cape Catoche, in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, is the northernmost point on the Yucatán Peninsula. It lies in the municipality of Isla Mujeres, about north of the city of Cancún. According to the International Hydrograph ...

Light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

(near Cancún

Cancún is the most populous city in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, located in southeast Mexico on the northeast coast of the Yucatán Peninsula. It is a significant tourist destination in Mexico and the seat of the municipality of Benito J ...

) at the northern tip of the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula ( , ; ) is a large peninsula in southeast Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north and west of the peninsula from the C ...

. Cuba has only of official gulf coastline, along its northern land boundary. The southwestern and southern shores of the gulf lie along the Mexican states

A Mexican State (), officially the Free and Sovereign State (), is a constituent federative entity of Mexico according to the Constitution of Mexico. Currently there are 31 states, each with its own constitution, government, state governor, a ...

of Tamaulipas, Veracruz, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatán, and the northernmost tip of Quintana Roo. On its southeast quadrant, the gulf is bordered by Cuba. It supports major American, Mexican, and Cuban fishing industries. The outer margins of the wide continental shelves of Yucatán and Florida receive cooler, nutrient-enriched waters from the deep by a process known as upwelling

Upwelling is an physical oceanography, oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted sur ...

, which stimulates plankton growth in the euphotic zone

The photic zone (or euphotic zone, epipelagic zone, or sunlight zone) is the uppermost layer of a body of water that receives sunlight, allowing phytoplankton to perform photosynthesis. It undergoes a series of physical, chemical, and biological ...

. This attracts fish, shrimp, and squid. River drainage and atmospheric fallout from industrial coastal cities also provide nutrients to the coastal zone. The

The Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude (North Carolin ...

, a warm Atlantic Ocean current and one of the strongest ocean current

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of seawater generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth contours, sh ...

s known, originates in the gulf as a continuation of the Caribbean Current–Yucatán Current–Loop Current

Mesh analysis (or the mesh current method) is a circuit analysis method for planar circuits; planar circuits are circuits that can be drawn on a plane surface with no wires crossing each other. A more general technique, called loop analysis ...

system. Other circulation features include a permanent cyclonic gyre

In oceanography, a gyre () is any large system of ocean surface currents moving in a circular fashion driven by wind movements. Gyres are caused by the Coriolis effect; planetary vorticity, horizontal friction and vertical friction determine the ...

in the Bay of Campeche

The Bay of Campeche (), or Campeche Sound, is a bight in the southern area of the Gulf of Mexico, forming the north side of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. It is surrounded on three sides by the Mexican states of Campeche, Tabasco and Veracruz. The ...

and anticyclonic gyres, which are shed by the Loop Current and travel westwards, where they eventually dissipate. The Bay of Campeche constitutes a major arm of the Gulf of Mexico. Numerous bays and smaller inlets fringe the gulf's shoreline. Streams that empty into the gulf include the Mississippi River and the Rio Grande in the northern gulf and the Grijalva and Usumacinta rivers in the southern gulf. The land that forms the gulf's coast, including many long, narrow barrier islands, is almost uniformly low-lying and is defined by marshes, swamps, and stretches of sandy beach.

The Gulf of Mexico is an excellent example of a

The Gulf of Mexico is an excellent example of a passive margin

A passive margin is the transition between Lithosphere#Oceanic lithosphere, oceanic and Lithosphere#Continental lithosphere, continental lithosphere that is not an active plate continental margin, margin. A passive margin forms by sedimentatio ...

. The continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an islan ...

is quite wide at most points along the coast, notably at the Florida and Yucatán Peninsulas. The shelf is exploited for its oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) and lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturate ...

through offshore drilling rigs, most of which are situated in the western gulf and the Bay of Campeche. Another important commercial activity is fishing; major catches include red snapper, amberjack

Amberjacks are Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, Pacific fish in the genus ''Seriola'' of the family Carangidae. They are widely consumed across the world in various cultures, most notably for Pacific amberjacks in Japanese cuisine; they are most oft ...

, tilefish

file:Malacanthus latovittatus.jpg, 250px, Blue blanquillo, ''Malacanthus latovittatus''

Tilefishes are mostly small perciform marine fish comprising the family (biology), family Malacanthidae. They are usually found in sandy areas, especially n ...

, swordfish

The swordfish (''Xiphias gladius''), also known as the broadbill in some countries, are large, highly migratory predatory fish characterized by a long, flat, pointed bill. They are the sole member of the Family (biology), family Xiphiidae. They ...

, and various grouper

Groupers are a diverse group of marine ray-finned fish in the family Epinephelidae, in the order Perciformes.

Groupers were long considered a subfamily of the seabasses in Serranidae, but are now treated as distinct. Not all members of this f ...

, as well as shrimp

A shrimp (: shrimp (American English, US) or shrimps (British English, UK)) is a crustacean with an elongated body and a primarily Aquatic locomotion, swimming mode of locomotion – typically Decapods belonging to the Caridea or Dendrobranchi ...

and crabs. Oysters

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of Seawater, salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in Marine (ocean), marine or Brackish water, brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly Calcification, calcified, a ...

are also harvested on a large scale from many bays and sounds. Other important industries along the coast include shipping, petrochemical processing and storage, military use, paper manufacture, and tourism. The gulf is considered aseismic; however, mild tremors have been recorded throughout history (usually 5.0 or less on the

The gulf is considered aseismic; however, mild tremors have been recorded throughout history (usually 5.0 or less on the Richter magnitude scale

The Richter scale (), also called the Richter magnitude scale, Richter's magnitude scale, and the Gutenberg–Richter scale, is a measure of the strength of earthquakes, developed by Charles Richter in collaboration with Beno Gutenberg, and pr ...

). Interactions between sediment loading on the sea floor and adjustment by the crust may cause earthquakes. On September 10, 2006, the U.S. Geological Survey National Earthquake Information Center reported that a magnitude 6.0 earthquake occurred about west-southwest of Anna Maria, Florida

Anna Maria is a city in Manatee County, Florida, United States. Anna Maria is part of the North Port-Bradenton-Sarasota, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 968 at the 2020 census, down from 1,503 in 2010.

The city occu ...

. The quake was reportedly felt from Louisiana to Florida. There were no reports of damage or injuries. Items were knocked from shelves and seiche

A seiche ( ) is a standing wave in an enclosed or partially enclosed body of water. Seiches and seiche-related phenomena have been observed on lakes, reservoirs, swimming pools, bays, harbors, caves, and seas. The key requirement for formatio ...

s were observed in swimming pools in parts of Florida. The earthquake was described by the USGS

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), founded as the Geological Survey, is an government agency, agency of the United States Department of the Interior, U.S. Department of the Interior whose work spans the disciplines of biology, geograp ...

as an intraplate earthquake

An intraplate earthquake occurs in the ''interior'' of a Plate tectonics, tectonic plate, in contrast to an interplate earthquake on the ''boundary'' of a tectonic plate. They are relatively rare compared to the more familiar interplate earthqu ...

, the largest and most widely felt recorded in the past three decades in the region. According to ''The Tampa Tribune

''The Tampa Tribune'' was a daily newspaper published in Tampa, Florida. Along with the competing ''Tampa Bay Times'', the ''Tampa Tribune'' was one of two major newspapers published in the Tampa Bay area.

The newspaper also published a ''St. P ...

'' on the following day, earthquake tremors were last felt in Florida in 1952, recorded in Quincy, northwest of Tallahassee

Tallahassee ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Florida. It is the county seat of and the only incorporated municipality in Leon County. Tallahassee became the capital of Florida, then the Florida Territory, in 1824. In 2024, the est ...

.

Maritime boundary delimitation agreements

Cuba and Mexico: Exchange of notes constituting an agreement on thedelimitation

Electoral boundary delimitation (or simply boundary delimitation or delimitation) is the drawing of boundaries of electoral precincts and related divisions involved in elections, such as Federated state, states, counties or other municipalities ...

of the exclusive economic zone of Mexico in the sector adjacent to Cuban maritime areas (with map), of July 1976.

Cuba and United States: Maritime boundary

A maritime boundary is a conceptual division of Earth's water surface areas using physiographical or geopolitical criteria. As such, it usually bounds areas of exclusive national rights over mineral and biological resources,VLIZ Maritime Boun ...

agreement between the United States of America and the Republic of Cuba, of December 1977.

Mexico and United States: Treaty to resolve pending boundary differences and maintain the Rio Grande and Colorado River as the international boundary, of November 1970; Treaty on maritime boundaries between the United States of America and the United Mexican States (Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean), of May 1978, and treaty on the delimitation of the continental shelf in the western Gulf of Mexico beyond , of June 2000.