The First Carlist War was a

civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

in

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

from 1833 to 1840, the first of three

Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the

Spanish monarchy

The monarchy of Spain or Spanish monarchy () is the constitutional form of government of Spain. It consists of a hereditary monarch who reigns as the head of state, being the highest office of the country.

The Spanish monarchy is constitu ...

: the conservative and devolutionist supporters of the late king's brother,

Carlos de Borbón (or ''Carlos V''), became known as

Carlists (''carlistas''), while the progressive and centralist supporters of the

regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

,

Maria Christina, acting for

Isabella II of Spain

Isabella II (, María Isabel Luisa de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904) was Queen of Spain from 1833 until her deposition in 1868. She is the only queen regnant in the history of unified Spain.

Isabella wa ...

, were called Liberals (''liberales''), ''cristinos'' or ''isabelinos''. Aside from being a

war of succession

A war of succession is a war prompted by a succession crisis in which two or more individuals claim to be the Order of succession, rightful successor to a demise of the Crown, deceased or deposition (politics), deposed monarch. The rivals are ...

about the question who the rightful successor to King

Ferdinand VII of Spain

Ferdinand VII (; 14 October 1784 – 29 September 1833) was Monarchy of Spain, King of Spain during the early 19th century. He reigned briefly in 1808 and then again from 1813 to his death in 1833. Before 1813 he was known as ''el Deseado'' (t ...

was, the Carlists' goal was the return to an

absolute monarchy, while the Liberals sought to defend the

constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

.

It was the largest and most deadly civil war in nineteenth-century Europe and fought by more men than the

Spanish War of Independence. It might have been the largest counter-revolutionary movement in 19th-century Europe depending on the figures. Furthermore, it is considered the "last great European conflict of the pre-industrial age". The conflict was responsible for the deaths of 5% of the 1833 Spanish population—with military casualties alone amounting to half this number. It was mostly fought in the

Southern Basque Country

The Southern Basque Country (; ) refers to the Basque territories southside of the Pyrenees, within the Iberian Peninsula.

Name

In Basque language, known as '' Euskera'', natives have referred to the Basque districts as ''Euskal Herria(k)''.

...

,

Maestrazgo, and

Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

and characterized by endless raids and reprisals against both armies and civilians.

Importantly, it is also considered a precursor to the idea of

the two Spains that would surface during the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

a century later.

Background

Before the start of the Carlist Wars, Spain was in a deep social, economic, and political crisis as a result of mismanagement by

Charles IV and

Ferdinand VII, and had stagnated from the reforms and successes of

Charles III of Spain

Charles III (; 20 January 1716 – 14 December 1788) was King of Spain in the years 1759 to 1788. He was also Duke of Parma and Piacenza, as Charles I (1731–1735); King of Naples, as Charles VII; and King of Sicily, as Charles III (or V) (1735� ...

.

Demographic

Spain had only slightly more than 20 inhabitants per square kilometer in the early 19th century, much less than other European countries. At the start of the Carlist War, the population was approximately 12.3 million people.

Loss of the colonies

While the

Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence () took place across the Spanish Empire during the early 19th century. The struggles in both hemispheres began shortly after the outbreak of the Peninsular War, forming part of the broader context of the ...

began in 1808, more than two decades before the death of Ferdinand VII, the social, economic and political effects of the American conflicts still were of great significance in the peninsula. In fact, not until the start of the Carlist conflict did Spain abandon all plans of military reconquest. Between 1792 and 1827 the value in millions of reales of imports of goods, imports of money, and exports from the Americas had decreased by a factor of 3.80, 28.0, and 10.3 respectively.

Furthermore,

various conflicts with the British and especially the

Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar was a naval engagement that took place on 21 October 1805 between the Royal Navy and a combined fleet of the French Navy, French and Spanish Navy, Spanish navies during the War of the Third Coalition. As part of Na ...

had left the Spanish without the naval strength to maintain healthy maritime trade with the Americas and the Philippines, leading to historically low overseas revenue. Between 1792 and 1827, Spanish foreign imports decreased from 714.9 million

reals to 226.2 and exports decreased from 397 million to 221.2. This economic weakness would prove crucial at restraining Spain's ability to climb out of the woes of the next decades and leading up to the Carlist wars.

War of Spanish Independence and the Napoleonic Wars

While Spain had been an ally of

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, this changed in 1808 after France occupied Spain and installed

Joseph Bonaparte

Joseph Bonaparte (born Giuseppe di Buonaparte, ; ; ; 7 January 176828 July 1844) was a French statesman, lawyer, diplomat and older brother of Napoleon Bonaparte. During the Napoleonic Wars, the latter made him King of Naples (1806–1808), an ...

as King in place of the

Bourbons. Although the high nobility accepted this change, the Spanish people did not and soon

a bloody guerilla war erupted. This war lasted until 1814, and during those years Spain would be ravaged by the estimated deaths of over a million civilians out of the twelve that populated Spain at the time. Furthermore, French troops heavily looted the country, especially as the focus of the army shifted towards the

French invasion of Russia

The French invasion of Russia, also known as the Russian campaign (), the Second Polish War, and in Russia as the Patriotic War of 1812 (), was initiated by Napoleon with the aim of compelling the Russian Empire to comply with the Continenta ...

.

Economic

In the 19th century, Spain was heavily in debt and in a dire situation economically.

Various conflicts with the British and especially the

Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar was a naval engagement that took place on 21 October 1805 between the Royal Navy and a combined fleet of the French Navy, French and Spanish Navy, Spanish navies during the War of the Third Coalition. As part of Na ...

had left the Spanish without the naval strength to maintain healthy maritime trade with the Americas and the Philippines, leading to historically low overseas revenue and ability to control the colonies. The ''de facto'' independence of many of these colonies during the Napoleonic Wars and later

wars of independence further strained the royal coffers. Between 1824 and 1833 the average annual income was "barely more than half" the pre-wars' level. Additionally, the political instability further constrained Spain's ability to collect taxes—the Riego revolt meant the government could only collect 12% of its projected revenue for the first half of 1820.

Spain had been heavily looted during the Napoleonic Wars and had only managed to fight as a junior partner under British leadership, financed and even clothed by British subsidies. Nonetheless, the Spanish government would be overburdened with costs needed to establish control over the country over the following decades—88% of taxes collected in February 1822 went to fund the military—which increased when Ferdinand maintained a French garrison between 1824 and 1828 "as a

Varangian Guard

The Varangian Guard () was an elite unit of the Byzantine army from the tenth to the fourteenth century who served as personal bodyguards to the Byzantine emperors. The Varangian Guard was known for being primarily composed of recruits from Nort ...

" to ensure his power. In 1833, Spain's forces comprised 100,000 Royalist Volunteers, 50,000 regulars, and 652 generals.

The progressives of the Trienio had managed to secure loans from British financiers, which Ferdinand then defaulted on. This made securing further loans even harder for the fledgling Spanish economy. Some historians argue that the Pragmatic Sanction was encouraged in order to please the politically-active liberal financiers, and in fact it was in the interest of loan repayment that the British and French protected the ''cristinos'' during the war. However, the former statement can be explained by the growing influence of Maria Cristina in the courts.

Furthermore, Spain was undergoing a deflationary spiral caused by both the Napoleonic War and the loss of the colonies, which left Spanish producers without the incredibly valuable market to sell their goods to as well as the Mint without the metal crucial to make coins. In order to protect the local industry, Spain established

protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

policies, which served to greatly encourage a black market. In fact, Great Britain was exporting three times as many products into Gibraltar than into the rest of Spain despite the dramatic discrepancy in population size.

Moreover, Spain's agricultural production had greatly stalled during Ferdinand's reign, partly due to the wars but also importantly due to a lack of improvements in practices and technology. The effects of poor harvests in 1803-1804 and the most "serious shortages of food in a century and a half" that resulted were exacerbated by the Peninsular War. Still, agriculture accounted for 85% of the Spanish

GDP. While output had recovered to pre-war levels, the prices remained unattainable for many peasants. As most of the land was concentrated on the hands of wealthy nobles and the church who had no incentive to increase production, "vast tracks

f landlay totally uncultivated". Areas like the Basque Country were privileged exceptions to a Spain where "the majority of the population was made up of landless workers who eked out a miserable existence. One obstacle to increasing the productive use of land were the wide limits on noble, ecclesiastical, and town-owned lands' sale. These lands could be very profitable, such as in the case in mid-1700s

Castile and León

Castile and León is an Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in northwestern Spain. Castile and León is the largest autonomous community in Spain by area, covering 94,222 km2. It is, however, sparsely populated, with a pop ...

where land owned by the Church accounted for one-fourth of rent collected. All in all, unsellable land accounted for more than half of Spain's farmland, thus hiking the price of land and making it impossible for small farmers to acquire land.

In fact, many Spanish foods were invented in those times to combat the lack of food. In 1817 one finds the first reference to

Spanish omelette as "…two to three eggs in tortilla for 5 or 6

eopleas our women do know how to make it big and thick with fewer eggs, mixing potatoes, breadcrumbs or whatever."

Ferdinand's governmental gridlock only further exacerbated the economic situation, as they were unable to create significant economic policies to tackle the issues or encourage internal demand. In fact, Ferdinand clashed with burghers as to how to manage the rural areas which were now extremely sparsely populated, to the shock of international observers. The sparseness of population as well as the general predicaments of Spanish labourers resulted in gross mismanagement of arable landand inability of Spain to significantly restart industrial and commercial activity after the Napoleonic War. The economic troubles were portrayed at the time as a result of moral faults in society, introduced by either one's political enemies or the war.

National politics

In 1823, the Spanish Government during the

Trienio Liberal

The , () or Three Liberal Years, was a period of three years in Spain between 1820 and 1823 when a liberal government ruled Spain after a military uprising in January 1820 by the lieutenant-colonel Rafael del Riego against the absolutist rule ...

had re-instated the

Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy (), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz () and nicknamed ''La Pepa'', was the first Constitution of Spain and one of the earliest codified constitutions in world history. The Constitution ...

, which had abolished the

fueros and established a

parliamentary monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

, among other changes. Ferdinand VII repealed it later in the year after he appealed to European powers of the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

in order to restore his absolute powers and France

sent a military expedition. The decade that followed the end of the Trienio became known as the

Ominous Decade, in which Ferdinand suppressed his enemies, the press, and the institutional reforms of the liberals. He also established a militia called the ''

Voluntarios Realistas'' ("Royalist Volunteers") which peaked at 284,000 men in 1832 in order to facilitate this suppression, led by an inspector general who answered only to the King himself and funded independently by permanent tax revenues. They were recruited exclusively from conservatives and declared its aim the protection of the royals against liberal attacks.

This decade was plagued by political instability, with a large ultra-conservative revolt breaking out in

1827

Events

January–March

* January 5 – The first regatta in Australia is held, taking place in Tasmania (called at the time ''Van Diemen's Land''), on the River Derwent at Hobart.

* January 15 – Furman University, founded in 1826, b ...

and an unsuccessful British-backed liberal

Pronunciamiento in

1831. Ferdinand was unable to control the situation and cycled through ministers, being described by

Friedrich von Gentz in 1814: "The king himself enters the houses of his prime ministers, arrests them, and hands them over to their cruel enemies;" and on 14 January 1815: "the king has so debased himself that he has become no more than the leading police agent and prison warden of his country." This assessment seems accurate, as the king himself described himself as "a cork in a bottle of beer": as soon as that cork was removed, all the troubles of Spain would explode into the open. In addition, as part of his police state Ferdinand revived the inquisition and expanded it to have "agents in every single village in the realm."

The divide between liberals and conservatives, both unhappy with Ferdinand's reign, was further strengthened by his publication in March, 1830 of

the Pragmatic Sanction, which replaced

the Salic system with a mixed succession system that would allow his daughters to inherit the throne (he had no male heir). This replaced his brother Charles as next-in-succession with his first daughter Isabella, who would be born later that year in October. It was at this point that the Royalist Volunteers and police, which had become politicized towards conservatism, threatened Ferdinand's court as they might support Carlos instead of his heir. Ferdinand died a month before Isabella's third birthday, his reign considered one of the worst in Spanish history, and so the kingdom fell into a regency led first by her mother

Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies.

A strong absolutist party feared that the regent Maria Christina would make liberal reforms, and sought another candidate for the throne. This was due to her owing her choice as Ferdinand's wife to the liberal faction of the court and

Princess Luisa Carlotta of the Two Sicilies, wife of Ferdinand's brother

Francisco

Francisco is the Spanish and Portuguese form of the masculine given name ''Franciscus''.

Meaning of the name Francisco

In Spanish, people with the name Francisco are sometimes nicknamed "Paco (name), Paco". Francis of Assisi, San Francisco de A ...

and court rival of

Infanta Maria Francisca of Portugal, wife of Carlos. The natural choice, based on Salic Law, was Ferdinand's brother

Carlos. The differing views on the influence of the army and the Church in governance, as well as

the forthcoming administrative reforms paved the way for the expulsion of the Conservatives from the higher governmental circles. At the same time, moderate

royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

s and constitutionalist liberals coalesced around their support of the Pragmatic Sanction and against Carlos.

As written by one historian:

The first Carlist war was fought not so much on the basis of the legal claim of Don Carlos, but because a passionate, dedicated section of the Spanish people favored a return to a kind of absolute monarchy that they felt would protect their individual freedoms (fueros), their regional individuality and their religious conservatism.

This opportunistic view of Carlism is further supported by the fact that "Carlism" was first mentioned in official correspondence in 1824, both after the restoration of absolutism to Spain by the French expedition and more than 35 years after the

1789 succession discussions which Ferdinand ratified in his Sanction.

Crisis of 1832

By September 1832, it was clear that King Ferdinand would soon die. To avert a civil war, Maria Christina sent

Antonio de Saavedra y Jofré to ask Carlos to serve as principal advisor during the regency and arrange a marriage between Isabella and Carlos' son

Carlos Luis. Carlos refused on religious grounds. He warned her that God would punish him in the afterlife for giving away a throne that was rightfully his. On September 18, at the urging of Maria Christina who was outnumbered in Court by Carlists, Ferdinand revoked the Pragmatic Sanction. Soon afterwards, however, he regained his health and was no longer in immediate danger of dying (though by that point rumours had been widely published abroad that he had died). This episode spurred the liberals to enact extensive personnel changes in the government, army, bureaucracy, police, and Royalist Volunteers in order to drive out the royalists who had been so close to realizing Carlos's claim to the throne. For example, in one dispatch the captain-general of

Extremadura

Extremadura ( ; ; ; ; Fala language, Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is a landlocked autonomous communities in Spain, autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, Spain, Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central- ...

proposed the removal of 12 governors, king's lieutenants, and

garrison adjutants; 1 colonel; 5 field officers of the Royalist Volunteers; 3 employees of the military treasury; 5 employees of the captain-general's office; the former chief of police; 7 employees of the treasury office; 1 artillery captain; and 3 post office employees.

Cea Bermudez's centrist government (1 October 1832 - January 1834) inaugurated the return to Spain of many exiles from London and Paris, e.g.

Juan Álvarez Mendizabal (born Méndez). The rise of Cea Bermudez was followed by a closer collaboration and understanding with Spain's debtors, who in turn clearly encouraged the former's reforms and liberalization, i.e. the new liberal regime and the incorporation of Spain to the European financial system. After its formation, Maria Isabella published a manifesto threatening those that would seek any change in the government system (namely, "pure unadulterated monarchy under

..King Ferdinand VII"). Coverdale suggests this manifesto was inspired by Bermudez's philosophy of

enlightened despotism. Nonetheless, the political situation in Spain was too fragmented for a moderate government like Bermudez's to gain and maintain public support and most of its activity was restrained to controlling potential rebellions from both the Carlists and the liberals.

On 6 October, Ferdinand named Maria Cristina

interim governor and allowed her to publish decrees in his name on both urgent and day-to-day affairs. She quickly re-opened the universities (which had been closed as centers of liberal agitation) and removed many captains-generals and garrison town military commanders as well as General

Nazario Eguía from their positions. These included

Vicente González Moreno,

José O'Donnell, and

Santos Ladrón de Cegama, all of whom would later join the Carlists in the civil war. Additionally, the Queen suppressed the tax raised to fund the Royalist Volunteers (which were directly collected by them) and removed the political requirements for joining them.

On 15 October, Maria Cristina issued a political amnesty for many exiles and liberals (except for those that had voted in favor of the King's removal and those that had led armed forces against him). A few weeks later, these former political criminals became eligible to hold office again and consequently the liberals mobilized around the Queen.

Basque Carlism and the ''Fueros''

Historically, the loyalty of the Basque regions to the kings of Spain and, until the French Revolution, France depended on their upholding of traditional laws, customs, and special privileges. Their

representative assemblies go back to the Middle Ages, yet their privileges had been consistently and progressively devalued by both monarchies. While the fueros that formerly made up the

Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon (, ) ;, ; ; . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of Barcelona (later Principality of Catalonia) and ended as a consequence of the War of the Sp ...

and included Catalonia, Aragon, Valencia, and the Balearic Islands had been abolished in the

Nueva Planta decrees

The Nueva Planta decrees (, , ) were a number of decrees signed between 1707 and 1716 by Philip V of Spain, Philip V, the first House of Bourbon, Bourbon Monarchy of Spain, King of Spain, during and shortly after the end of the War of the Spani ...

of 1717, the Basques managed to maintain a relative autonomy to the rest of the Spanish Kingdom in thanks to their support of

Philip V of Spain

Philip V (; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was List of Spanish monarchs, King of Spain from 1 November 1700 to 14 January 1724 and again from 6 September 1724 to his death in 1746. His total reign (45 years and 16 days) is the longest in the ...

in the

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

.

The centralisers in the Spanish government supported some of the great powers against Basque merchants from at least since the time of the abolition of the Jesuit order and the

Godoy regime. First they sided with the French Bourbons to suppress the Jesuits, following the formidable changes in North America after the victory of the United States in the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. Then Godoy sided with the British against the Basques in the

War of the Pyrenees of 1793, and immediately afterwards with the French of

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, also against the Basques. The British interest was to destroy, for as long as possible, Spanish commercial routes and power, which were mainly sustained by the Basque ports and merchant fleet.

The Constitution of 1812 was written without Basque input, but they agreed to it due to the ongoing war against the French. As one example, the 1812 Constitution was signed by Gipuzkoan representatives under the watch of a sword-wielding

general Castaños, and tellingly the

San Sebastián

San Sebastián, officially known by the bilingual name Donostia / San Sebastián (, ), is a city and municipality located in the Basque Autonomous Community, Spain. It lies on the coast of the Bay of Biscay, from the France–Spain border ...

council representatives took the oath to the 1812 Constitution with the smell of smoke still wafting and

surrounded by rubble. This Constitution abolished Basque home rule, and in the following years the ''contrafueros'' (literally "against fueros") removed provisions such as fiscal sovereignty and specificity of

military draft. The resentment against the growing intervention of Madrid (e.g. attempts to take over Biscayan mines in 1826) and the loss of autonomy was considerably strong.

However,

King Ferdinand VII found an important support base in the Basque Country. The 1812

Constitution of Cádiz had suppressed Basque home rule, and was couched in terms of a unified Spanish nation which rejected the existence of the Basque nation, so the new Spanish king garnered the

endorsement of the Basques as long as he respected the Basque institutional and legal framework.

Most foreign observers, including

Charles F. Henningsen, Michael B. Honan, or Edward B. Stephens, English writers and first-hand witnesses of the First Carlist War, spent time in the

Basque districts were highly sympathetic to the Carlists, which they regarded as representing the cause of Basque home rule. A notable exception was John Francis Bacon, a diplomat residing in Bilbao during the Carlist siege of (1835), who, while praising Basque governance, could not hide his hostility towards the Carlists, whom he regarded as "savages." He went on to contest his compatriots' approach, denied a connection between the Carlist cause and the defense of the

Basque liberties, and speculated that Carlos V would be quick to erode or suppress them if he took the Spanish throne.

The privileges of the Basque provinces are odious to the Spanish nation, of which Charles is so well aware, that if he was king of Spain next year, he would quickly find excuses for infringing them, if not their total abolition. A representative government will endeavour to raise Spain to a level with the Basque provinces, – a despot, to whom the very name of freedom is odious, would strive to reduce the provinces to the same low level with the rest.

Modern historian Mark Lawrence agrees:

The Pretender's foralism was not proactive but purely in reaction to the fact that the rest of Spain (which had long been stripped of its fueros) had failed to rally to his cause. He was forced to rely on the fueros because no other wing of the Fernandine state, neither the army nor (mostly) the Church, defected to the Carlist cause. In fact, the fueros grew in importance only when military victory seemed impossible in the wake of the failed Royal Expedition, and as Carlist peace feelers voiced a growing willingness to abandon Don Carlos who, since 1834, had been the fueros’ champion.

and further notes that "the powers of the fueros themselves were increasingly curtailed by the Carlist Royal Government in the name of the war effort."

The interests of the Basque liberals were divided. On the one side, fluent cross-Pyrenean trade with other Basque districts and France was highly valued, as well as unrestricted overseas transactions. The former had been strong up to the French Revolution, especially in Navarre, but the new French national arrangement (1790) had abolished the separate legal and fiscal status of the

French Basque districts. Despite difficulties, on-off trade continued during the period of uncertainty prevailing under the French Convention, the

War of the Pyrenees (1793-1795),

Manuel Godoy's tenure in office, and the Peninsular War. Eventually, Napoleonic defeat left cross-border commercial activity struggling to take off

after 1813.

Overseas commerce was badly affected by the end of the

Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas (1785), the French-Spanish defeat at the

Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar was a naval engagement that took place on 21 October 1805 between the Royal Navy and a combined fleet of the French Navy, French and Spanish Navy, Spanish navies during the War of the Third Coalition. As part of Na ...

(1805),

independence movements in Latin America (started 1808),

the destruction of San Sebastián (1813), and the eventual breakup of the

Royal Philippine Company (1814). By 1826 all the grand Spanish (including the Basque) fleet of the late 18th century with its renowned Basque navigators was gone, and with it, the Atlantic vocation of the Enlightened Spain.

Notwithstanding the ideology of Basque liberals, overall supportive of home rule, the Basques and their industries were getting choked by the above circumstances and customs on the

Ebro

The Ebro (Spanish and Basque ; , , ) is a river of the north and northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, in Spain. It rises in Cantabria and flows , almost entirely in an east-southeast direction. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea, forming a de ...

, on account of the high levies enforced on them by the successive Spanish governments after 1776. Many Basque merchants advocated in turn for the relocation of the Ebro customs to the Pyrenees, and the encouragement of a Spanish market. However, a majority of Basque consumers benefited from their ability to buy foreign goods without paying Spanish tariffs and participation in the contraband trade.

On Ferdinand VII's death in 1833, the minor Isabella II was proclaimed queen, with Maria Christina acting as regent. In November, a new Spanish institutional arrangement was designed by the incoming government in Madrid,

homogenising Spanish administration according to provinces and conspicuously overruling Basque institutions.

The early attempts of the Viceroy of Navarra to recruit villagers into Cristino ranks failed miserably, even when service wages were offered of double, then treble, what the Carlist insurgents promised. Coverdale summarised four factors as to why this was so: (1) traditional society was still economically viable for most of population, hence liberalism was seen a threat; (2) natural leadership strata (clergy, landowners) lived cheek by jowl with peasants and supported the Carlist cause; (3) the terrain was sufficiently abrupt and broken to prevent the use of cavalry and to facilitate small bands to escape (to change their shirts and fight another day), whilst the landscape was densely populated enough to allow regular food and supplies; and (4) the appearance of the extremely gifted guerrilla leader, Tomás de Zumalacárregui. Other parts of Spain may have had one, or some of these factors, but not all four.

In this context the additional importance of the loss of the colonies arises. The basques had traditionally emigrated to the New World in order to get better jobs and deal with their rising population in a highly mountainous region which could not support large populations. The end of this option during a period of accelerated population growth meant that the Basque region "faced a bottleneck of impoverished and underemployed men of military age who had little

olose by joining Carlist insurrections". It is important to note that Basque support for Carlism was "far more conditional than

istoriantraditionalists, neo-traditionalists, and even Liberals believed." As Mark Lawrence writes, "it would be superficial to explain Basque Carlism as a war in defence of the fueros" but also states that "Basque Carlism is also impossible to understand without them, not least because their most outspoken defenders were to be found in Carlist ranks and their most outspoken critics amongst the Cristino Liberals."

Contenders

The people of the

western Basque provinces (ambiguously called "Biscay" up to that point) and

Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

sided with Carlos because ideologically Carlos was close to them and more importantly because he was willing to uphold Basque institutions and laws. Some historians claim that the Carlist cause in the

Basque Country was a pro-''fueros'' cause, but others (

Stanley G. Payne

Stanley George Payne (born September 9, 1934) is an American historian of modern Spain and Europe, European fascism at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He retired from full-time teaching in 2004 and is currently Professor Emeritus at its Dep ...

) contend that no connection to the emergence of Basque nationalism can be postulated. Many supporters of the Carlists cause believed a traditionalist rule would better respect the ancient region specific institutions and laws established under historical rights. Navarre and the rest of the Basque provinces held their customs on the Ebro river. Trade had been strong with France (especially in Navarre) and overseas up to the Peninsular War (up to 1813), but getting sluggish thereafter.

Another important reason for the massive mobilisation of the western Basque provinces and Navarre for the Carlist cause was the tremendous influence of the Basque clergy whose number per capita was double that of other regions. Basque clergy still addressed the public in their own language,

Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

, unlike school and administration, institutions where Spanish had been imposed by then. The Basque

pro-''fueros'' liberal class under the influence of the Enlightenment and ready for independence from Spain (and initially at least allegiance to France) was put down by the Spanish authorities at the end of the

War of the Pyrenees (

San Sebastián

San Sebastián, officially known by the bilingual name Donostia / San Sebastián (, ), is a city and municipality located in the Basque Autonomous Community, Spain. It lies on the coast of the Bay of Biscay, from the France–Spain border ...

,

Pamplona

Pamplona (; ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Navarre, Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain.

Lying at near above sea level, the city (and the wider Cuenca de Pamplona) is located on the flood pl ...

, etc.). As of then, the strongest partisans of the

region specific laws were the rural based clergy, nobility and lower class—opposing new liberal ideas largely imported from France.

Salvador de Madariaga

Salvador de Madariaga y Rojo (23 July 1886 – 14 December 1978) was a Spanish "eminent liberal",

diplomat, writer, historian and pacifist who was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature and the Nobel Peace Prize and awarded the Charl ...

, in his book ''Memories of a Federalist'' (Buenos Aires, 1967), accused the Basque clergy of being "the heart, the brain and the root of the intolerance and the hard line" of the Spanish Catholic Church.

On the other side, the liberals and moderates united to defend the new order represented by María Cristina and her three-year-old daughter, Isabella. They controlled the institutions, almost the whole army, and the cities; the Carlist movement was stronger in rural areas. The liberals had the crucial support of

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

,

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, support that was shown in the important credits to Cristina's treasury and the military help from the British (British Legion or

Westminster Legion under

General de Lacy Evans), the French (the

French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (, also known simply as , "the Legion") is a corps of the French Army created to allow List of militaries that recruit foreigners, foreign nationals into French service. The Legion was founded in 1831 and today consis ...

), and the Portuguese (a Regular Army Division under General

Count of Antas). The Liberals were strong enough to win the war in two months, but an inefficient government and the dispersion of the Carlist forces gave Carlos time to consolidate his forces and hold out for almost seven years in the northern and eastern provinces.

As

Paul Johnson has written, "both royalists and liberals began to develop strong local followings, which were to perpetuate and transmute themselves, through many open commotions and deceptively tranquil intervals, until they exploded in the merciless civil war of 1936-39."

[Paul Johnson, ''The Birth of the Modern World: Society 1815-1830'' (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), 660.]

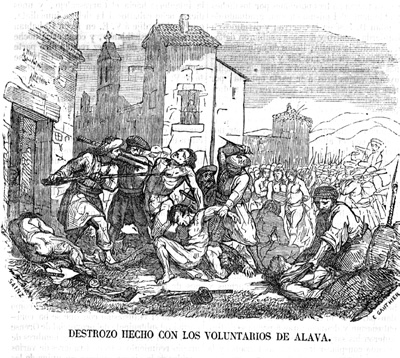

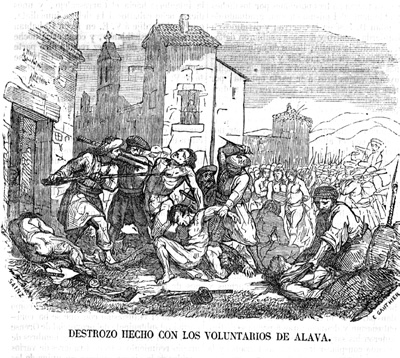

Combatants

Both sides raised special troops during the war. The Liberal side formed the volunteer Basque units known as the

Chapelgorris, while

Tomás de Zumalacárregui

Tomás de Zumalacárregui e Imaz (Basque language, Basque: Tomas Zumalakarregi Imatz; 29 December 178824 June 1835), known among his troops as "Uncle Tomás", was a Spaniards, Spanish Basques, Basque officer who led the Carlism, Carlist faction ...

created the special units known as

aduaneros. Zumalacárregui also established the unit known as

Guías de Navarra from Liberal troops from

La Mancha,

Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

,

Andalusia

Andalusia ( , ; , ) is the southernmost autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain, located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in southwestern Europe. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomou ...

and other places who had been taken prisoner at the

Battle of Alsasua (1834). After this battle, they had been faced with the choice of joining the Carlist troops or being executed.

The term

Requetés was at first applied to just the Tercer Batallón de Navarra (Third Battalion of Navarre) and subsequently to all Carlist combatants.

The war attracted independent adventurers, such as the

Briton

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs modern British citizenship and nationality, w ...

C. F. Henningsen, who served as Zumalacárregui's chief bodyguard (and later was his biographer), and

Martín Zurbano, a ''contrabandista'' or

smuggler

Smuggling is the illegal transportation of objects, substances, information or people, such as out of a house or buildings, into a prison, or across an international border, in violation of applicable laws or other regulations. More broadly, soc ...

, who:

soon after the commencement of the war sought and obtained permission to raise a body of men to act in conjunction with the queen's troops against the Carlists. His standard, once displayed, was resorted to by smugglers, robbers, and outcasts of all descriptions, attracted by the prospect of plunder and adventure. These were increased by deserters...["A Night Excursion with Martin Zurbano", ''Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine'', Vol. 48, July–December 1840 (T. Cadell and W. Davis, 1840), 740.]

About 250 foreign volunteers fought for the Carlists; the majority were French

monarchists

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. C ...

, but they were joined by men from

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

,

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

,

Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

,

Piedmont-Sardinia, and the

German states.

[19th Century bibliography of military history in the Basque Country](_blank)

/ref> Friedrich, Prince of Schwarzenberg fought for the Carlists, and had taken part in the French conquest of Algeria

The French conquest of Algeria (; ) took place between 1830 and 1903. In 1827, an argument between Hussein Dey, the ruler of the Regency of Algiers, and the French consul (representative), consul escalated into a blockade, following which the Jul ...

and the Swiss civil war of the Sonderbund. The Carlists' ranks included such men as Prince Felix Lichnowsky, Adolfo Loning, Baron Wilhelm Von Radhen and August Karl von Goeben, all of whom later wrote memoirs concerning the war. The Liberal generals, such as Vicente Genaro de Quesada and Marcelino de Oraá Lecumberri, were often veterans of the

The Liberal generals, such as Vicente Genaro de Quesada and Marcelino de Oraá Lecumberri, were often veterans of the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1808–1814) was fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French ...

, or of the wars resulting from independence movements in South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

. For instance, Jerónimo Valdés participated in the battle of Ayacucho

The Battle of Ayacucho (, ) was a decisive military encounter during the Peruvian War of Independence. This battle secured the independence of Peru and ensured independence for the rest of belligerent South American states. In Peru it is conside ...

(1824).

Both sides executed prisoners of war by firing squad

Firing may refer to:

* Dismissal (employment), sudden loss of employment by termination

* Firemaking, the act of starting a fire

* Burning; see combustion

* Shooting, specifically the discharge of firearms

* Execution by firing squad, a method of ...

; the most notorious incident occurred at Heredia, when 118 Liberal prisoners were executed by order of Zumalacárregui. The British attempted to intervene, and through Lord Eliot, the Lord Eliot Convention was signed on April 27–28, 1835.

The treatment of prisoners of the First Carlist War became regulated and had positive effects. A soldier of the British Auxiliary Legion wrote:

The British and Chapelgorris who fell into their hands he Carlists were mercilessly put to death, sometimes by means of tortures worthy of the North American Indians; but the Spanish troops of the line were saved by virtue, I believe, of the Eliot treaty, and after being kept for some time in prison, where they were treated with sufficient harshness, were frequently exchanged for an equal number of prisoners made by the Christinos.[Charles William Thompson, ''Twelve Months in the British Legion, by an Officer of the Ninth Regiment'' (]Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

, 1836), 129.

However, Henry Bill, another contemporary, wrote that, although "it was mutually agreed upon to treat the prisoners taken on either side according to the ordinary rules of war, a few months only elapsed before similar barbarities were practiced with all their former remorselessness."[Henry Bill, ''The History of the World'' (1854), 142.]

The contenders

Carlos, the Church, and the Nobility

Carlos had refused to openly challenge either the Pragmatic Sanction nor his brother while the latter remained alive, as the "recent legitimist rising knowns as the Agraviados had taught him the wisdom of awaiting events." This may be due to nineteenth century Spain being highly politically unstable through endless pronunciamientos. His allies in the courts and important positions of the Spanish state had been purged by the liberals towards the last months of Ferdinand's life, weakening various centers of Carlist strength. Few private citizens, however, were persecuted for their political opinions during this time.

In order to strengthen public support, the Carlist created significant amounts of propaganda, both during the war and in the years leading up to it. Carlos's refusal to swear an oath to Isabel in a letter to his brother was widely published, as well as a supposed response from universities about Carlos's right to the throne and two articles published in French periodicals that also focused on the judicial right of Carlos to the throne. The pamphlets and manifestos are divided into two types: the first includes legal arguments for why Don Carlos was the sole rightful heir to the Spanish throne while the second was composed by political arguments that were often laden with heavily religious overtones.

Most of these propagandist pamphlets published before the war were printed in France by Carlist exiles who then smuggled them into Spain, and so were most widely distributed in the northern regions of the Basque Country, Navarre, Aragon, and Catalonia.

Carlos found allies in the same areas that resisted the Liberals near the end of the Trienio: primarily in upland Navarra and the Basque provinces but also in inland Catalonia, Aragon, Galicia, and Old Castille. One historian called the minor civil war between Liberals and royalists in 1823 "a geographic dress rehearsal for the Carlist War".

Nonetheless, support for Carlos was not politically uniform. Basque Carlism was socially conservative and supported their stable rural economy, whereas in the Maestrazgo and Catalonia it was more of a protest vehicle for peasants against the negative effects of urbanization and new Liberal property regulations were having on their livelihood Such regulations were threatening to abolish the ''de facto'' rights to use-ownership of land by peasants and move towards a more

Carlos had refused to openly challenge either the Pragmatic Sanction nor his brother while the latter remained alive, as the "recent legitimist rising knowns as the Agraviados had taught him the wisdom of awaiting events." This may be due to nineteenth century Spain being highly politically unstable through endless pronunciamientos. His allies in the courts and important positions of the Spanish state had been purged by the liberals towards the last months of Ferdinand's life, weakening various centers of Carlist strength. Few private citizens, however, were persecuted for their political opinions during this time.

In order to strengthen public support, the Carlist created significant amounts of propaganda, both during the war and in the years leading up to it. Carlos's refusal to swear an oath to Isabel in a letter to his brother was widely published, as well as a supposed response from universities about Carlos's right to the throne and two articles published in French periodicals that also focused on the judicial right of Carlos to the throne. The pamphlets and manifestos are divided into two types: the first includes legal arguments for why Don Carlos was the sole rightful heir to the Spanish throne while the second was composed by political arguments that were often laden with heavily religious overtones.

Most of these propagandist pamphlets published before the war were printed in France by Carlist exiles who then smuggled them into Spain, and so were most widely distributed in the northern regions of the Basque Country, Navarre, Aragon, and Catalonia.

Carlos found allies in the same areas that resisted the Liberals near the end of the Trienio: primarily in upland Navarra and the Basque provinces but also in inland Catalonia, Aragon, Galicia, and Old Castille. One historian called the minor civil war between Liberals and royalists in 1823 "a geographic dress rehearsal for the Carlist War".

Nonetheless, support for Carlos was not politically uniform. Basque Carlism was socially conservative and supported their stable rural economy, whereas in the Maestrazgo and Catalonia it was more of a protest vehicle for peasants against the negative effects of urbanization and new Liberal property regulations were having on their livelihood Such regulations were threatening to abolish the ''de facto'' rights to use-ownership of land by peasants and move towards a more contract

A contract is an agreement that specifies certain legally enforceable rights and obligations pertaining to two or more parties. A contract typically involves consent to transfer of goods, services, money, or promise to transfer any of thos ...

and cash

In economics, cash is money in the physical form of currency, such as banknotes and coins.

In book-keeping and financial accounting, cash is current assets comprising currency or currency equivalents that can be accessed immediately or near-i ...

-based system.

In addition, Carlism did not represent a rural fight against urban development, as " rbanartisans threatened by recurrent Liberal abolition of the guilds and redundant officeholders (cesantes) could be drawn to Carlism, whilst, by contrast, villagers who had benefited from the Liberal property revolution would correspondingly turn Cristino; flight either from or to the countryside in many cases entrenched a rural (Carlist) versus urban (Cristino) divide, but as an effect rather than a cause of the conflict."

It is highly likely that there were nobles outside of the three Carlist "heartlands" that were in favour of his cause, but any public show of support would have resulted in the Cristino court banishing those nobles from Madrid and seizing their extensive lands and income. Northern nobles, simply speaking, had much less land to lose. Carlism in Cristino areas can be differentiated into civic and ''faccioso'' (insurgent) Carlists. The latter were often bandits looking for political cover, while civic Carlists were subject to progressively harsher treatment as the war radicalized Spanish politics.

Overall, the Carlist position can be summarized as a radical reactionary policy to restore the privileges of the church and nobles, decentralise legislative and judicial powers, and bring the monarchy to a more medieval role that was less absolutist and more dependent on nobles. "In other words, the Carlists wanted to revise not just the recent Liberal revolution but the entire eighteenth-century legacy of enlightened absolutism."

Maria Christina, the Great Powers, and the Liberal Government

On the other side, the liberals and moderates united to defend the new order represented by María Cristina and her three-year-old daughter, Isabella. They controlled the institutions, almost the whole army, and the cities; the Carlist movement was stronger in rural areas. The liberals had the crucial support of United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, support that was shown in the important credits to Cristina's treasury and the military help from the British (British Legion or Westminster Legion under General de Lacy Evans), the French (the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (, also known simply as , "the Legion") is a corps of the French Army created to allow List of militaries that recruit foreigners, foreign nationals into French service. The Legion was founded in 1831 and today consis ...

), and the Portuguese (a Regular Army Division, under General Count of Antas).

Military

It is important to note that the liberals were just as multi-faceted as the Carlists, carrying on the factionalism that had characterized them during the Peninsular War. They disagreed in regards to military, with the ''guerilleros'' (patriot guerilla bands), the Bourbon army, and the National militia (a part-time citizen's force organized at a local level and "in the hands of property owners" which was written into the Constitution yet saw only "ephemeral" involvement at the end of the Napoleonic war) all favored by different politicians and at different times both before and during the war. The national militia was championed by the Liberals during the Trienio, but required a literacy test and ability to afford the uniform from those enlisted. However, they received the same privileges and immunity as the military while having as only requirement the condition of "when active in their duties" which led to significant in-fighting and an "extra-paramilitary double regime" during the Trienio.

The growing anti-militarist sentiment amongst the liberals resulted in the emergence in the Napoleonic War amongst the army of a faction that "was hostile to the whole constitutional experiment" due to the "shabby treatment" received from politicians. Conditions were not significantly better during the Ferdinandine reign, as soldiers faced late payments and inadequate rations and its Liberal officers placed on half-pay or remote garrisons by the distrustful king (many of these officers later led Rafael del Riego's ''pronunciamiento'').< Note also that conscripts had no ''a priori'' reason to be committed to the Cristino cause, while officers had a career they were willing to sacrifice their men and military considerations for.

The Liberal generals, such as Vicente Genaro de Quesada and Marcelino de Oraá Lecumberri, were often veterans of the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1808–1814) was fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French ...

, or of the wars resulting from independence movements in South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

. For instance, Jerónimo Valdés participated in the battle of Ayacucho

The Battle of Ayacucho (, ) was a decisive military encounter during the Peruvian War of Independence. This battle secured the independence of Peru and ensured independence for the rest of belligerent South American states. In Peru it is conside ...

(1824).

Army organization

Special troops and foreign volunteers

Both sides raised special troops during the war. The Liberal side formed the volunteer Basque units known as the Chapelgorris, while Tomás de Zumalacárregui

Tomás de Zumalacárregui e Imaz (Basque language, Basque: Tomas Zumalakarregi Imatz; 29 December 178824 June 1835), known among his troops as "Uncle Tomás", was a Spaniards, Spanish Basques, Basque officer who led the Carlism, Carlist faction ...

created the special units known as aduaneros. Zumalacárregui also established the unit known as Guías de Navarra from Liberal troops from La Mancha, Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

, Andalusia

Andalusia ( , ; , ) is the southernmost autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain, located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in southwestern Europe. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomou ...

and other places who had been taken prisoner at the Battle of Alsasua (1834). After this battle, they had been faced with the choice of joining the Carlist troops or being executed.

The term Requetés was at first applied to just the Tercer Batallón de Navarra (Third Battalion of Navarre) and subsequently to all Carlist combatants.

The war attracted independent adventurers, such as the Briton

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs modern British citizenship and nationality, w ...

C. F. Henningsen, who served as Zumalacárregui's chief bodyguard (and later was his biographer), and Martín Zurbano, a ''contrabandista'' or smuggler

Smuggling is the illegal transportation of objects, substances, information or people, such as out of a house or buildings, into a prison, or across an international border, in violation of applicable laws or other regulations. More broadly, soc ...

, who:soon after the commencement of the war sought and obtained permission to raise a body of men to act in conjunction with the queen's troops against the Carlists. His standard, once displayed, was resorted to by smugglers, robbers, and outcasts of all descriptions, attracted by the prospect of plunder and adventure. These were increased by deserters...

About 250 foreign volunteers fought for the Carlists; the majority were French monarchists

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. C ...

, but they were joined by men from Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

, Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

, and the German states.[19th Century bibliography of military history in the Basque Country](_blank)

/ref> Friedrich, Prince of Schwarzenberg fought for the Carlists, and had taken part in the French conquest of Algeria

The French conquest of Algeria (; ) took place between 1830 and 1903. In 1827, an argument between Hussein Dey, the ruler of the Regency of Algiers, and the French consul (representative), consul escalated into a blockade, following which the Jul ...

and the Swiss civil war of the Sonderbund. The Carlists' ranks included such men as Prince Felix Lichnowsky, Adolfo Loning, Baron Wilhelm Von Radhen and August Karl von Goeben, all of whom later wrote memoirs concerning the war.

Treatment of prisoners

Both sides executed prisoners of war by firing squad

Firing may refer to:

* Dismissal (employment), sudden loss of employment by termination

* Firemaking, the act of starting a fire

* Burning; see combustion

* Shooting, specifically the discharge of firearms

* Execution by firing squad, a method of ...

; the most notorious incident occurred at Heredia, when 118 Liberal prisoners were executed by order of Zumalacárregui. The British attempted to intervene, and through Lord Eliot, the Lord Eliot Convention was signed on April 27–28, 1835.

The treatment of prisoners of the First Carlist War in the Basque region became regulated and had temporary positive effects. A soldier of the British Auxiliary Legion wrote:The British and Chapelgorris who fell into their hands he Carlists were mercilessly put to death, sometimes by means of tortures worthy of the North American Indians; but the Spanish troops of the line were saved by virtue, I believe, of the Eliot treaty, and after being kept for some time in prison, where they were treated with sufficient harshness, were frequently exchanged for an equal number of prisoners made by the Christinos.

However, Henry Bill, another contemporary, wrote that, although "it was mutually agreed upon to treat the prisoners taken on either side according to the ordinary rules of war, a few months only elapsed before similar barbarities were practiced with all their former remorselessness."siege train

In military contexts, a train is the logistical transport elements accompanying a military force. Often called a supply train or baggage train, it has the job of providing materiel for their associated combat forces when in the field. When focus ...

s.

Prisoners also were the worst sufferers of the long forced marches that were common in the conflict. Most died of hunger or disease in the few months after being captured and were forced to scavenge for food, resorting first to unripe root crops and eventually to cannibalism. For example, during the Royal Expedition Cabrera executed a number of Cristino cannibals that were caught during the act but the prisoners could not even stand up to receive the bullets. Thankfully after some months the surviving prisoners of the expedition were exchanged between sides.

Logistics

Army conditions

Armies on both sides had difficulties securing food and medical treatment for their troops. The food situation was so bad that Wilhelm von Radhen wrote of Carlos subsisting on "a pan of fried potatoes a day".

Many wounded would be left for dead on the battlefield or taken to dirty field hospitals with high mortality rates. For example, 3/4 of the wounded Liberals in the Morella campaign died within days. Wounded soldiers, depending on the source, account for 11.1-37% of combat fatalities. However, it is hard to estimate exactly how many soldiers died due to army conditions as contemporary sources often had partisan agendas and distorted figures.

Use of Intelligence

Carlist forces had significantly superior access to and quality of information due to their support in the regions where the conflict was fought. This allowed them to develop internal lines of communication, which were then used to devastating effect by Carlist generals. As reported by British Ambassador George Villiers, they would use spy networks and flash telegrammes to gather and communicate information. Cristino armies were often forced to use the valleys when travelling in the front lines, while Carlists were able to use hillpaths to transport troops and supplies using mule trains. Cabrera was specially known for diversions, such as driving herds of cattle to leave false footprints or luring enemies by creating false exposed flanks.

Defenses

While permanent fortresses placed in vantage points and equipped with artillery were used, guerilla patrols and armed farmers often served to control remote hilltops and roads between villages and cities.

War

The war was long and hard, and the Carlist forces (labeled "the Basque army" by John F. Bacon) achieved important victories in the north under the direction of the brilliant general Tomás de Zumalacárregui

Tomás de Zumalacárregui e Imaz (Basque language, Basque: Tomas Zumalakarregi Imatz; 29 December 178824 June 1835), known among his troops as "Uncle Tomás", was a Spaniards, Spanish Basques, Basque officer who led the Carlism, Carlist faction ...

. The Basque commander swore an oath to uphold home rule in Navarre (''fueros''), subsequently being proclaimed commander in chief of Navarre. The Basque regional governments of Biscay, Álava

Álava () or Araba (), officially Araba/Álava, is a Provinces of Spain, province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country (autonomous community), Basque Country, heir of the ancient Basque señoríos#Lords of Álava, Lordship ...

, and Gipuzkoa followed suit by pledging obedience to Zumalacárregui. He took to the bush in the Amescoas (to become the Carlist headquarters, next to Estella-Lizarra

Estella (Spanish language, Spanish) or Lizarra (Basque language, Basque) is a town located in the autonomous community of Navarre, in northern Spain. It lies south west of Pamplona, close to the border with La Rioja (autonomous community), La Rioj ...

), there making himself strong and avoiding the harassment of the Spanish forces loyal to Maria Christina (Isabella II). 3,000 volunteers with no resources came to swell his forces.

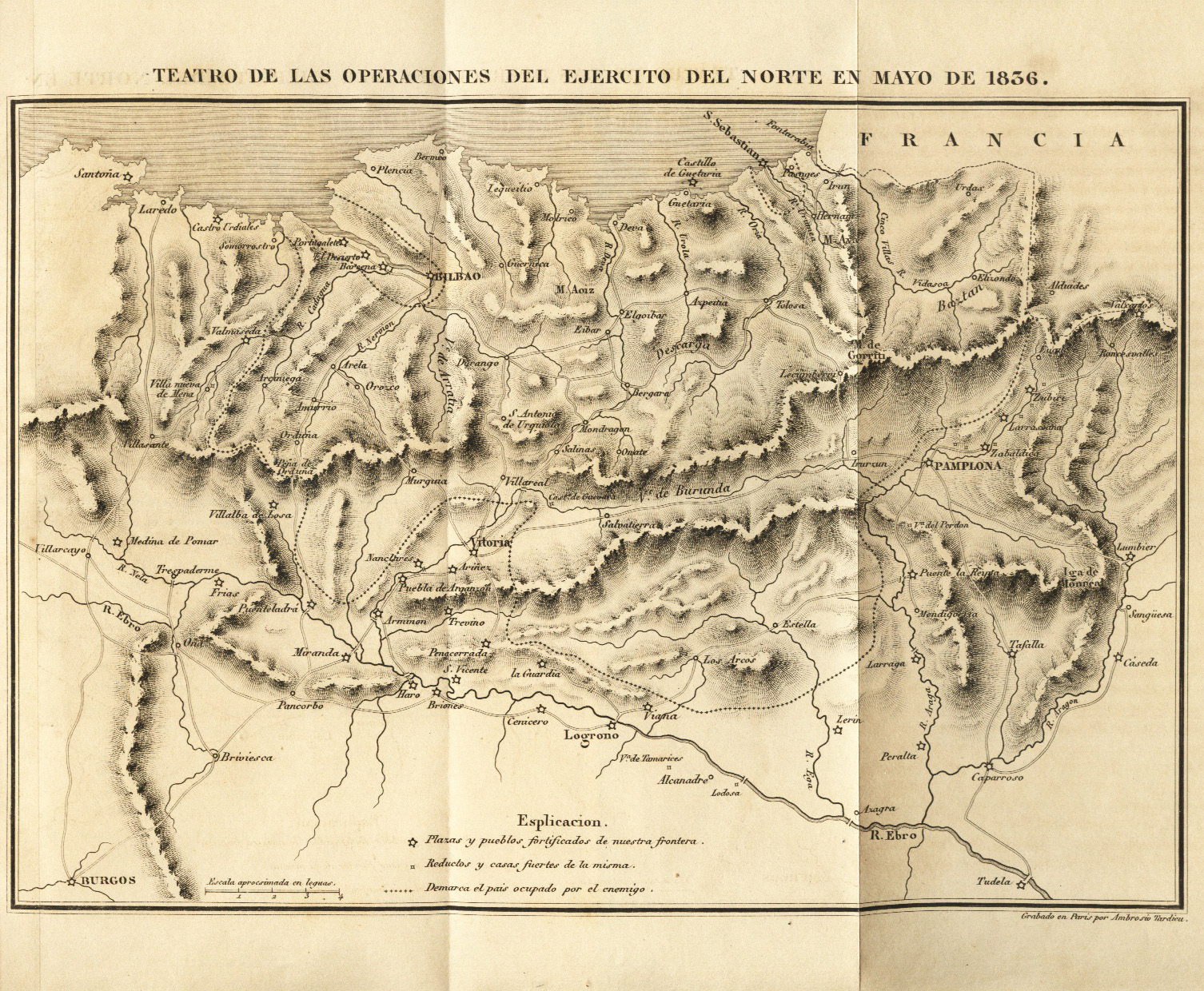

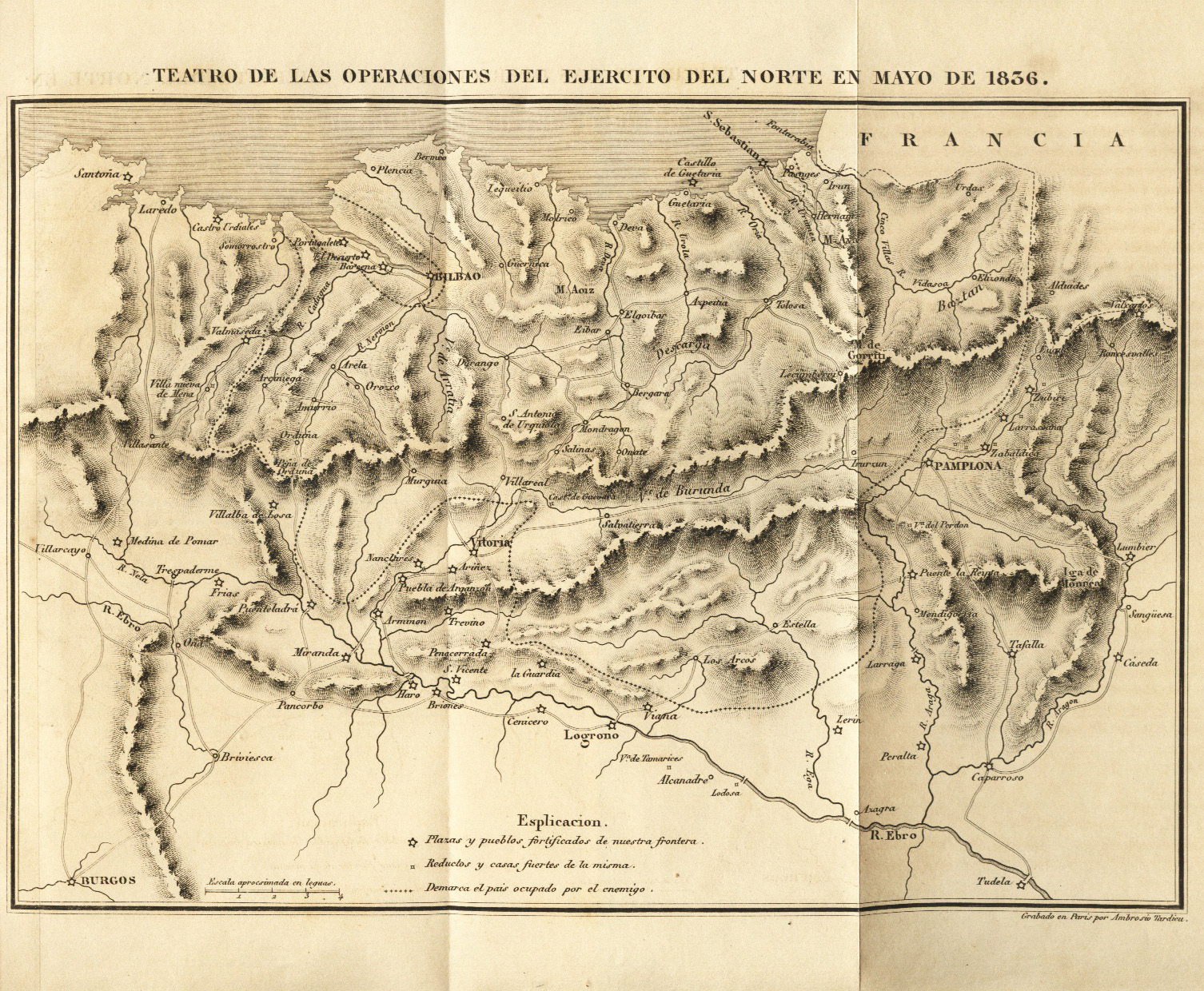

1833

Northern front

In December, Valdes's focus on Navarre allowed the Carlists in the other Basque provinces to regroup as the secondary units he left behind only patrolled the main roads and garrisoned the principal towns of the region. As local officials were mostly Carlists, men that returned to their towns were allowed to keep their weapons and thus join the Carlist army again. In response to the developing situation, Valdes established the death penalty for a number of offenses including returning to the Carlist bands after surrendering and accepting a pardon, encouraging or commanding others to join a Carlist band, failing to surrender one's weapons or give the authorities information on arms caches, and the distribution of subversive propaganda. Authorities would also face the death penalty if they failed to collect weapons from the inhabitants under them, if they allowed Carlist recruitment, or if they allowed mail in their jurisdiction to be stolen, except when faced by overwhelming force. Those who were reasonably suspected of these crimes but could not be proved guilty were instead sentenced to four years' hard labor. These measures were relatively ineffective.

Meanwhile, Zumalacárregui regrouped his forces in the Borunda valley along the road between Pamplona and Vitoria, which was conveniently placed between the Urbasa and Andia ranges and provided his troops with many escape routes through which they as locals could escape much more quickly than the Carlist regular troops could follow.

1834

In April 1834, France, Great Britain, Spain, and Portugal signed the treaty of the Quadruple Alliance. Under its terms, Pedro IV of Portugal

''Don (honorific), Dom'' Pedro I (12 October 1798 – 24 September 1834), known in Brazil and in Portugal as "the Liberator" () or "the Soldier King" () in Portugal, was the founder and List of monarchs of Brazil, first ruler of the Empire of ...

would expel the Carlists and Miguel I from Portugal with the aid of Spanish troops and the British navy. In additional stipulations, France established stricter border controls to prevent the entry of men, weapons, and military supplies into Spain to Carlist hands. Britain also pledged arms and munitions as well as possible naval support if necessary and Portugal promised Spain all possible aid. Even though the treaty was a significant diplomatic victory and lessened the likelihood of Carlists receiving diplomatic recognition or aid from other countries, Spain did not receive much material aid from France or Britain for more than a year afterwards. With state coffers yet again empty and the ''Trienio Liberal'' loan issue with the financiers still not settled, Cea Bermudez's government fell.

Northern front

In summer 1834, Liberal (Isabeline) forces set fire to the Sanctuary of Arantzazu

The Sanctuary of Our Lady of Arantzazu is a Franciscan church located in Oñati, Basque Country (autonomous community), Basque Country, Spain. The church is a much-loved place among Gipuzkoans, as the Virgin of Arantzazu is the shrine’s namesa ...

and a convent of Bera, while Zumalacárregui showed his toughest side when he had volunteers refusing to advance over Etxarri-Aranatz executed. The Carlist cavalry engaged and defeated in Viana an army sent from Madrid (14 September 1834), while Zumalacárregui's forces descended from the Basque Mountains over the Álavan Plains (Vitoria), and prevailed over general Manuel O'Doyle. The veteran general Espoz y Mina, a Liberal Navarrese commander, attempted to drive a wedge between the Carlist northern and southern forces, but Zumalacárregui's army managed to hold them back (late 1834).

1835

In January, the liberal government of Francisco Martínez de la Rosa successfully narrowly defeated an attempted military coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

and then faced urban uprisings in Málaga

Málaga (; ) is a Municipalities in Spain, municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 591,637 in 2024, it is the second-most populo ...

, Zaragoza

Zaragoza (), traditionally known in English as Saragossa ( ), is the capital city of the province of Zaragoza and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributaries, the ...

, and Murcia

Murcia ( , , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the Capital (political), capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the Ranked lists of Spanish municipalities#By population, seventh largest city i ...

in the spring. The government's inability to deal with these crises as well as the lack of military success in the North forced the government to resign in June to be followed by a new government headed by former finance minister José María Queipo de Llano, 7th Count of Toreno.

In April, the British sent a mission under Edward Eliot, 3rd Earl of St Germans to convince both sides to spare the lives of prisoners and of the wounded as well as tell Don Carlos he had no hope of winning the war (Carlos thought that Eliot had come to propose an agreement which would end the war). Jerónimo Valdés and Zumalacárregui agreed not to kill prisoners, exchange them on a regular basis, respect the wounded, and to not execute political prisoners without trial. However, the agreement which came to be called the Lord Eliot Convention applied only to the Basque Country (although it could be applied to the rest of the country if war spread there). This is because the Liberals argued that Carlist troops outside the Basque Country were not regular troops and thus did not fall under the purview of the treaty. The Carlists themselves did not see the terms of the Convention as applying to foreign troops on the Liberal side.

By this point in the war, Zumalacárregui had so continuously defeated the Liberals that a majority of the officers in the Reserve Army believed they would only be able to win with foreign intervention. By late May, the government reluctantly requested the French for enough troops to occupy the Basque Country and the British for increased diplomatic and naval support. Britain did not believe this was yet necessary and asked France to limit itself to strengthening its border. France thus also denied the Spanish request. In response and in the face of Carlos's near-total control of the Basque Country, Madrid asked to be allowed to recruit volunteers which was agreed to in June. Thus, the British Auxiliary Legion was created and the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (, also known simply as , "the Legion") is a corps of the French Army created to allow List of militaries that recruit foreigners, foreign nationals into French service. The Legion was founded in 1831 and today consis ...

expanded its activities to Spain under the name of the Spanish Legion

For centuries, Spain recruited foreign soldiers to its army, forming the foreign regiments () such as the Regiment of Hibernia (formed in 1709 from Irishmen who fled their own country in the wake of the Flight of the Earls and the Penal la ...

.

Northern front

In January, the Carlists took over Baztan in an operation where the general Espoz y Mina narrowly escaped a severe defeat and capture, while the local Liberal Gaspar de Jauregi ''Artzaia'' ('the Shepherd') and his '' chapelgorris'' were neutralized in Zumarraga and Urretxu. By May, virtually all Gipuzkoa

Gipuzkoa ( , ; ; ) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the autonomous community of the Basque Country. Its capital city is Donostia-San Sebastián. Gipuzkoa shares borders with the French department of Pyrénées-Atlantiqu ...

and seigneury of Biscay