Duelling on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people with matched

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people with matched

PBS. Retrieved February 8, 2014 Public opinion, not legislation, caused the change. Research has linked the decline of dueling to increases in

In

In

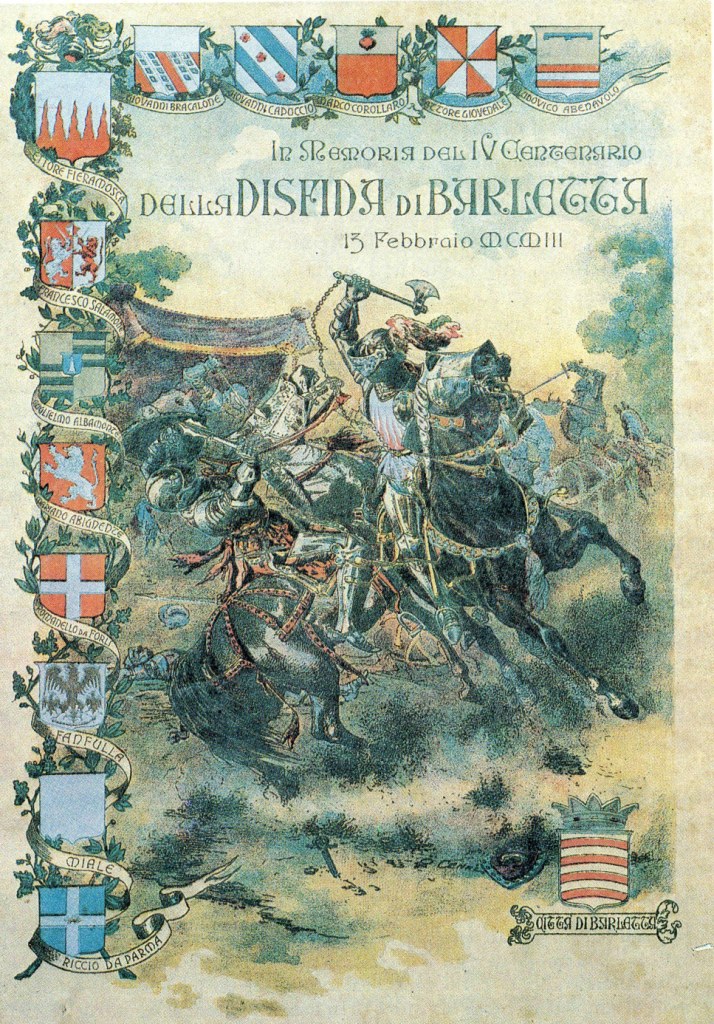

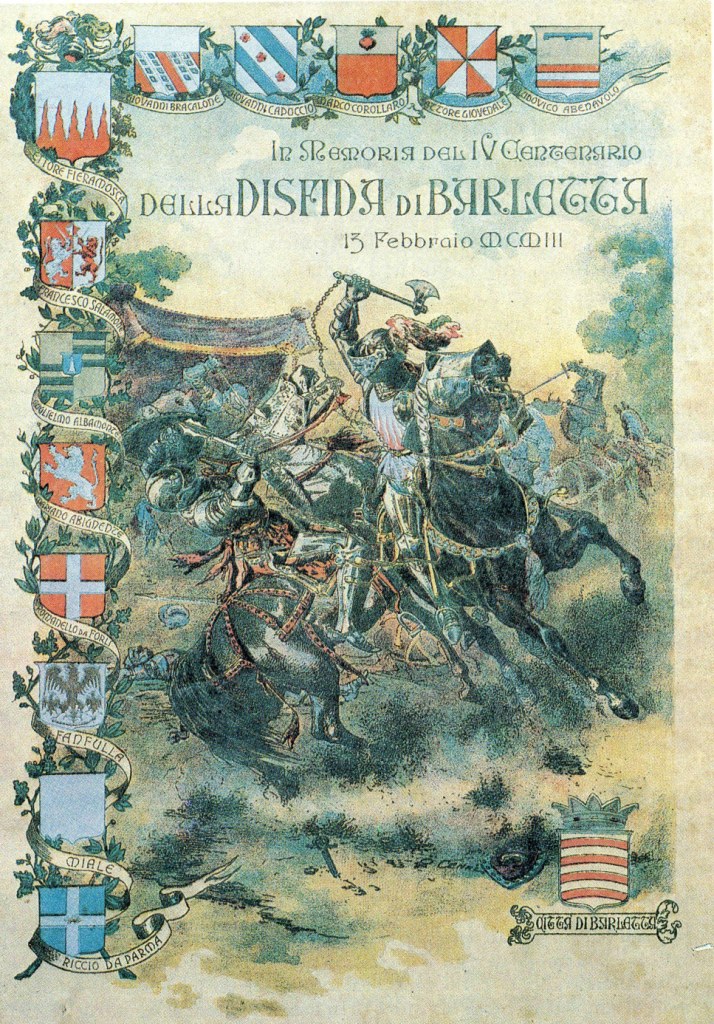

The first published '' code duello'', or "code of dueling", appeared in

The first published '' code duello'', or "code of dueling", appeared in

§ 93. 4. Der Zweikampf

(pp. 327–333).

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pistol dueling became popular as a sport in France. The duelists were armed with conventional pistols, but the cartridges had wax bullets and were without any powder charge; the bullet was propelled only by the explosion of the cartridge's primer.

Participants wore heavy, protective clothing and a metal helmet with a glass eye-screen. The pistols were fitted with a shield that protected the firing hand.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pistol dueling became popular as a sport in France. The duelists were armed with conventional pistols, but the cartridges had wax bullets and were without any powder charge; the bullet was propelled only by the explosion of the cartridge's primer.

Participants wore heavy, protective clothing and a metal helmet with a glass eye-screen. The pistols were fitted with a shield that protected the firing hand.

There were various methods of pistol dueling. The mode where the two duelists stood back-to-back, walked away from each other for a set number of paces before turning and firing was known as the "French" method.Hoptin (2011), p. 80 Another method required the duelists to stand still at an agreed distance and fire simultaneously on a signal – this was the type of duel favored in Britain. A variant of this required the duelists to take turns to shoot, with the challenger shooting first or the right of first shot being decided by a coin toss.

The distance at which the pistols were fired might depend on local custom, the wishes of the duelists or sometimes the severity of the insult. The American dueling code of 1838 suggested a distance between 10 and 20 paces.Hoptin (2011), p. 81 There were incidences of pistol duels taking place at just two or three paces, with a virtual certainty of one or both duelists being injured or killed.Hoptin (2011), p. 82

A method popular in Continental Europe was known as a ''barrier duel'' or a duel ("at pleasure"); it did not have a set shooting distance. The two duelists began some distance apart. Between them there were two lines on the ground separated by an agreed distance – this constituted the barrier and they were forbidden to cross it. After the signal to begin, they could advance towards the barrier to close the distance and were permitted to fire at any time. However, the one that shot first was required to stand still and allow his opponent to walk right up to his barrier line and fire back at leisure.Hoptin (2011), pp. 85–90

Many historical duels were prevented by the difficulty of arranging the "". In the instance of

There were various methods of pistol dueling. The mode where the two duelists stood back-to-back, walked away from each other for a set number of paces before turning and firing was known as the "French" method.Hoptin (2011), p. 80 Another method required the duelists to stand still at an agreed distance and fire simultaneously on a signal – this was the type of duel favored in Britain. A variant of this required the duelists to take turns to shoot, with the challenger shooting first or the right of first shot being decided by a coin toss.

The distance at which the pistols were fired might depend on local custom, the wishes of the duelists or sometimes the severity of the insult. The American dueling code of 1838 suggested a distance between 10 and 20 paces.Hoptin (2011), p. 81 There were incidences of pistol duels taking place at just two or three paces, with a virtual certainty of one or both duelists being injured or killed.Hoptin (2011), p. 82

A method popular in Continental Europe was known as a ''barrier duel'' or a duel ("at pleasure"); it did not have a set shooting distance. The two duelists began some distance apart. Between them there were two lines on the ground separated by an agreed distance – this constituted the barrier and they were forbidden to cross it. After the signal to begin, they could advance towards the barrier to close the distance and were permitted to fire at any time. However, the one that shot first was required to stand still and allow his opponent to walk right up to his barrier line and fire back at leisure.Hoptin (2011), pp. 85–90

Many historical duels were prevented by the difficulty of arranging the "". In the instance of

European styles of dueling established themselves in the colonies of European states in North America. Duels were to challenge someone over a woman or to defend one's honor. In the US, dueling tended to arise over political differences.

As early as 1728, some US states began to restrict or prohibit the practice. The penalty established upon conviction of killing another person in a duel in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in its 1728 law to punish and prevent dueling stated "In Case any Person shall slay or kill any other in Duel or Fight, as aforesaid and upon Conviction thereof suffer the Pains of Death, as is by Law provided for wilful Murder, the Body of such Person, shall not be allowed Christian Burial, but be buried without a Coffin, with a Stake driven Through the Body, at or near the Place of Execution, as aforesaid."

Dueling was the subject of an unsuccessful federal amendment to the United States Constitution in 1838. It was fairly common for politicians at that time in the United States to end disputes through duels, such as the Burr–Hamilton duel and the Jackson–Dickinson duel. While dueling had become outdated in the North since the early 19th century, this was not true of other regions of the nation.

Physician

European styles of dueling established themselves in the colonies of European states in North America. Duels were to challenge someone over a woman or to defend one's honor. In the US, dueling tended to arise over political differences.

As early as 1728, some US states began to restrict or prohibit the practice. The penalty established upon conviction of killing another person in a duel in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in its 1728 law to punish and prevent dueling stated "In Case any Person shall slay or kill any other in Duel or Fight, as aforesaid and upon Conviction thereof suffer the Pains of Death, as is by Law provided for wilful Murder, the Body of such Person, shall not be allowed Christian Burial, but be buried without a Coffin, with a Stake driven Through the Body, at or near the Place of Execution, as aforesaid."

Dueling was the subject of an unsuccessful federal amendment to the United States Constitution in 1838. It was fairly common for politicians at that time in the United States to end disputes through duels, such as the Burr–Hamilton duel and the Jackson–Dickinson duel. While dueling had become outdated in the North since the early 19th century, this was not true of other regions of the nation.

Physician

In

In

''Duels and Duelling'', Oxford: Shire, 2012

* Banks, Stephen. ''A Polite Exchange of Bullets; The Duel and the English Gentleman, 1750–1850'', (Woodbridge: Boydell 2010) * Banks, Stephen. "Very little law in the case: Contests of Honour and the Subversion of the English Criminal Courts, 1780-1845" (2008) 19(3) ''King's Law Journal'' 575–594. * Banks, Stephen. "Dangerous Friends: The Second and the Later English Duel" (2009) 32 (1) ''Journal of Eighteenth Century Studies'' 87–106. * Banks, Stephen. "Killing with Courtesy: The English Duelist, 1785-1845," (2008) 47 ''Journal of British Studies'' 528–558. * Bell, Richard, "The Double Guilt of Dueling: The Stain of Suicide in Anti-dueling Rhetoric in the Early Republic," ''Journal of the Early Republic,'' 29 (Fall 2009), 383–410. * Cramer, Clayton. ''Concealed Weapon Laws of the Early Republic: Dueling, Southern Violence, and Moral Reform'' * Freeman, Joanne B. ''Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic'' (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001; paperback ed., 2002) * Freeman, Joanne B. "Dueling as Politics: Reinterpreting the Burr-Hamilton Duel." ''The William and Mary Quarterly,'' 3d series, 53 (April 1996): 289–318. * Frevert, Ute. "Men of Honour: A Social and Cultural History of the Duel." trans. Anthony Williams Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995. * Greenberg, Kenneth S. "The Nose, the Lie, and the Duel in the Antebellum South." American Historical Review 95 (February 1990): 57–73. * * Kelly, James. ''That Damn'd Thing Called Honour: Duelling in Ireland 1570–1860'' (1995) * Kevin McAleer. ''Dueling: The Cult of Honor in Fin-de-Siecle Germany'' (1994) * * Rorabaugh, W. J. "The Political Duel in the Early Republic: Burr v. Hamilton." ''Journal of the Early Republic'' 15 (Spring 1995): 1–23. * Schwartz, Warren F., Keith Baxter and David Ryan. "The Duel: Can these Gentlemen be Acting Efficiently?." The Journal of Legal Studies 13 (June 1984): 321–355. * Steward, Dick. ''Duels and the Roots of Violence in Missouri'' (2000), * Williams, Jack K. ''Dueling in the Old South: Vignettes of Social History'' (1980) (1999), * Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. ''Honor and Violence in the Old South'' (1986) * Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. ''Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South'' (1982), * Holland, Barbara. "Gentlemen's Blood: A History of Dueling" New York, NY. (2003)

''Duels and Duelling'' (Stephen Banks) 2012

*

', John Lyde Wilson 1838 * ''The Field of Honor'' Benjamin C. Truman. (1884); reissued as ''Duelling in America'' (1993). * ''Savannah Duels & Duellists'', Thomas Gamble (1923) * ''Gentlemen, Swords and Pistols'', Harnett C. Kane (1951) * ''Pistols at Ten Paces: The Story of the Code of Honor in America'', William Oliver Stevens (1940) * ''The Duel: A History'', Robert Baldick (1965, 1996) * ''Dueling With the Sword and Pistol: 400 Years of One-on-One Combat'', Paul Kirchner (2004) * ''Duel'', James Landale (2005). . The story of the last fatal duel in Scotland * ''Ritualized Violence Russian Style: The Duel in Russian Culture and Literature'', Irina Reyfman (1999). * ''A Polite Exchange of Bullets; The Duel and the English Gentleman, 1750–1850'', Stephen Banks (2010)

1967 Epee Duel Deffere vs. Ribiere

* Ahn, Tom, Sandford, Jeremy, and Paul Shea. 2010.

Mend it, Don't End it: Optimal Mortality in Affairs of Honor

mimeo * Allen, Douglas, W., and Reed, Clyde, G., 2006,

The Duel of Honor: Screening for Unobservable Social Capital

" ''American Law and Economics Review'': 1–35.

Banks, Stephen, Dead before Breakfast: The English Gentleman and Honour Affronted", in S. Bibb and D. Escandell (eds), Best Served Cold: Studies on Revenge (Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2010)

Banks, Stephen "Challengers Chastised and Duellists Deterred: Kings Bench and Criminal Informations, 1800-1820" (2007) ANZLH E-Journal, Refereed Paper No (4)

* Kingston, Christopher G., and Wright, Robert E.

The Deadliest of Games: The Institution of Dueling

Dept. of Econ., Amherst College, Stern School of Business, NY Univ.

by John Lyde Wilson * {{Authority control Dueling

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people with matched

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people with matched weapon

A weapon, arm, or armament is any implement or device that is used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime (e.g., murder), law ...

s.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combat

Single combat is a duel between two single combatants which takes place in the context of a battle between two army, armies.

Instances of single combat are known from Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The champions were often combatants wh ...

s fought with sword

A sword is an edged and bladed weapons, edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter ...

s (the rapier

A rapier () is a type of sword originally used in Spain (known as ' -) and Italy (known as '' spada da lato a striscia''). The name designates a sword with a straight, slender and sharply pointed two-edged long blade wielded in one hand. It wa ...

and later the small sword

__NoTOC__

The small sword or smallsword (also court sword, Gaelic: or claybeg, French: , lit. “Sword of the court”) is a light one-handed sword designed for thrusting which evolved out of the longer and heavier rapier (''espada ropera'') o ...

), but beginning in the late 18th century in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, duels were more commonly fought using pistol

A pistol is a type of handgun, characterised by a gun barrel, barrel with an integral chamber (firearms), chamber. The word "pistol" derives from the Middle French ''pistolet'' (), meaning a small gun or knife, and first appeared in the Englis ...

s. Fencing

Fencing is a combat sport that features sword fighting. It consists of three primary disciplines: Foil (fencing), foil, épée, and Sabre (fencing), sabre (also spelled ''saber''), each with its own blade and set of rules. Most competitive fe ...

and shooting

Shooting is the act or process of discharging a projectile from a ranged weapon (such as a gun, bow, crossbow, slingshot, or blowpipe). Even the acts of launching flame, artillery, darts, harpoons, grenades, rockets, and guided missile ...

continued to coexist throughout the 19th century.

The duel was based on a code of honor. Duels were fought not to kill the opponent but to gain "satisfaction", that is, to restore one's honor by demonstrating a willingness to risk one's life for it. As such, the tradition of dueling was reserved for the male members of nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

; however, in the modern era, it extended to those of the upper class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status. Usually, these are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper cla ...

es. On occasion, duels with swords or pistols were fought between women.

Legislation against dueling dates back to the medieval period. The Fourth Council of the Lateran

The Fourth Council of the Lateran or Lateran IV was convoked by Pope Innocent III in April 1213 and opened at the Lateran Palace in Rome on 11 November 1215. Due to the great length of time between the council's convocation and its meeting, m ...

(1215) outlawed duels and civil legislation in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

against dueling was passed in the wake of the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

.

From the early 17th century, duels became illegal in the countries where they were practiced. Dueling largely fell out of favour in England by the mid-19th century and in Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous mainland of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by som ...

by the turn of the 20th century. Dueling declined in the Eastern United States

The Eastern United States, often abbreviated as simply the East, is a macroregion of the United States located to the east of the Mississippi River. It includes 17–26 states and Washington, D.C., the national capital.

As of 2011, the Eastern ...

in the 19th century and by the time of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, dueling had begun to wane even in the

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

.The History of Dueling in AmericaPBS. Retrieved February 8, 2014 Public opinion, not legislation, caused the change. Research has linked the decline of dueling to increases in

state capacity

State capacity is the ability of a government to accomplish policy goals, either generally or in reference to specific aims. More narrowly, state capacity often refers to the ability of a state to collect taxes, enforce law and order, and provide p ...

.

History

Early history and Middle Ages

In

In Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

society, the formal concept of a duel developed out of the medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

judicial duel

Trial by combat (also wager of battle, trial by battle or judicial duel) was a method of Germanic law to settle accusations in the absence of witnesses or a confession in which two parties in dispute fought in single combat; the winner of the ...

and older pre-Christian practices such as the Viking Age

The Viking Age (about ) was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonising, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. The Viking Age applies not only to their ...

''holmgang

Holmgang (, , Danish language, Danish and , ) is a duel practiced by early medieval Scandinavians. It was a legally recognized way to settle disputes.

The name ''holmgang'' (literally "holm-going") may derive from the combatants' dueling on a sm ...

''. In medieval society, judicial duels were fought by knights and squires to end various disputes.David Levinson and Karen Christensen. ''Encyclopedia of World Sport: From Ancient Times to the Present''. Oxford University Press; 1st edition (July 22, 1999). pp. 206. . Countries such as France, Germany, England, and Ireland practiced this tradition. Judicial combat took two forms in medieval society, the feat of arms and chivalric combat. The feat of arms was used to settle hostilities between two large parties and supervised by a judge. The battle was fought as a result of a slight or challenge to one party's honor

Honour ( Commonwealth English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is a quality of a person that is of both social teaching and personal ethos, that manifests itself as a code of conduct, and has various elements such as val ...

which could not be resolved by a court. Weapons were standardized and typical of a knight's armoury, for example longswords or polearms; however, weapon quality and augmentations were at the discretion of the knight; for example, a spiked hand guard or an extra grip for half-swording. The parties involved would wear their own armour; for example, one knight wearing full plate might face another wearing chain mail. The duel lasted until one party could no longer fight back. In early cases, the defeated party was then executed. This type of duel soon evolved into the more chivalric '' pas d'armes,'' or "passage of arms", a chivalric hastilude

Hastilude is a generic term used in the Middle Ages to refer to many kinds of martial games. The word comes from the Latin ''hastiludium'', literally "lance game". By the 14th century, the term usually excluded tournaments and was used to des ...

that evolved in the late 14th century and remained popular through the 15th century. A knight or group of knights ( or "holders") would stake out a travelled spot, such as a bridge or city gate, and let it be known that any other knight who wished to pass ( or "comers") must first fight, or be disgraced. If a traveling did not have weapons or horse to meet the challenge, one might be provided, and if the chose not to fight, he would leave his spurs behind as a sign of humiliation. If a lady passed unescorted, she would leave behind a glove or scarf, to be rescued and returned to her by a future knight who passed that way.

The Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

was critical of dueling throughout medieval history, frowning both on the traditions of judicial combat and on the duel on points of honor among the nobility. Judicial duels were deprecated by the Lateran Council of 1215, but the judicial duel persisted in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

into the 15th century. The word duel comes from the Latin ''duellum'', cognate with ''bellum'', meaning 'war'.

Renaissance and early modern Europe

During the earlyRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, dueling established the status of a respectable gentleman

''Gentleman'' (Old French: ''gentilz hom'', gentle + man; abbreviated ''gent.'') is a term for a chivalrous, courteous, or honorable man. Originally, ''gentleman'' was the lowest rank of the landed gentry of England, ranking below an esquire ...

and was an accepted manner to resolve disputes.  The first published '' code duello'', or "code of dueling", appeared in

The first published '' code duello'', or "code of dueling", appeared in Renaissance Italy

The Italian Renaissance ( ) was a period in History of Italy, Italian history between the 14th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Western Europe and marked t ...

. The first formalized national code was that of France, during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

. From the late 1580s to the 1620s, an estimated 10,000 French individuals (most of them nobility) were killed in duels.

By the 17th century, dueling had become regarded as a prerogative of the aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

, throughout Europe, and attempts to discourage or suppress it generally failed. For example, King Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

outlawed dueling in 1626, a law which remained in force afterwards, and his successor Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

intensified efforts to wipe out the duel. Despite these efforts, dueling continued unabated, and it is estimated that between 1685 and 1716, French officers fought 10,000 duels, leading to over 400 deaths.

In Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, as late as 1777, a code of practice was drawn up for the regulation of duels, at the Summer assize

The assizes (), or courts of assize, were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes ex ...

s in the town of Clonmel

Clonmel () is the county town and largest settlement of County Tipperary, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The town is noted in Irish history for its resistance to the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, Cromwellian army which sacked the towns of Dro ...

, County Tipperary

County Tipperary () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. The county is named after the town of Tipperary (tow ...

. A copy of the code, known as 'The twenty-six commandments', was to be kept in a gentleman's pistol case for reference should a dispute arise regarding procedure.

Enlightenment-era opposition

By the late 18th century,Enlightenment era

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

values began to influence society with new self-conscious ideas about politeness

Politeness is the practical application of good manners or etiquette so as not to offend others and to put them at ease. It is a culturally defined phenomenon, and therefore what is considered polite in one culture can sometimes be quite rude or ...

, civil behavior, and new attitudes toward violence

Violence is characterized as the use of physical force by humans to cause harm to other living beings, or property, such as pain, injury, disablement, death, damage and destruction. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence a ...

. The cultivated art of politeness demanded that there should be no outward displays of anger or violence, and the concept of honor became more personalized.

By the 1770s, the practice of dueling was increasingly coming under attack from many sections of enlightened society, as a violent relic of Europe's medieval past unsuited for modern life. As England began to industrialize and benefit from urban planning and more effective police forces

The police are a constituted body of people empowered by a state with the aim of enforcing the law and protecting the public order as well as the public itself. This commonly includes ensuring the safety, health, and possessions of citize ...

, the culture of street violence in general began to slowly wane. The growing middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

maintained their reputation with recourse to either bringing charges of libel

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

, or to the fast-growing print media of the early 19th century, where they could defend their honor and resolve conflicts through correspondence in newspapers.

Influential new intellectual trends at the turn of the 19th century bolstered the anti-dueling campaign; the utilitarian philosophy of Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February Dual dating, 1747/8 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S.– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of mo ...

stressed that praiseworthy actions were exclusively restricted to those that maximize human welfare and happiness, and the Evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

notion of the "Christian conscience" began to actively promote social activism. Individuals in the Clapham Sect

The Clapham Sect, or Clapham Saints, were a group of social reformers associated with Holy Trinity Clapham in the period from the 1780s to the 1840s. Despite the label "sect", most members remained in the Established Church, established (and do ...

and similar societies, who had successfully campaigned for the abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

, condemned dueling as ungodly violence and as an egocentric culture of honor.

Modern history

The formerUnited States Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

was killed in a duel against the sitting Vice President

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician, businessman, lawyer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805 d ...

in 1804. Between 1798 and the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, the U.S. Navy lost two-thirds as many officers to dueling as it did in combat at sea, including naval hero Stephen Decatur

Commodore (United States), Commodore Stephen Decatur Jr. (; January 5, 1779 – March 22, 1820) was a United States Navy officer. He was born on the eastern shore of Maryland in Worcester County, Maryland, Worcester County. His father, Ste ...

. Many of those killed or wounded were midshipmen or junior officers. Despite prominent deaths, dueling persisted because of contemporary ideals of chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric language, is an informal and varying code of conduct that developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It is associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood, with knights being members of ...

, particularly in the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, and because of the threat of ridicule if a challenge was rejected.

By about 1770, the duel underwent a number of important changes in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. Firstly, unlike their counterparts in many continental nations, English duelists enthusiastically adopted the pistol, and sword duels dwindled. Special sets of dueling pistols were crafted for the wealthiest of noblemen for this purpose. Also, the office of 'second' developed into 'seconds' or 'friends' being chosen by the aggrieved parties to conduct their honor dispute. These friends would attempt to resolve a dispute upon terms acceptable to both parties and, should this fail, they would arrange and oversee the mechanics of the encounter.

In England, to kill in the course of a duel was formally judged as murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse committed with the necessary Intention (criminal law), intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisd ...

, but generally the courts were very lax in applying the law, as they were sympathetic to the culture of honor. Despite being a criminal act, military officers in many countries could be punished if they failed to fight a duel when the occasion called for it. In 1814, a British officer was court-martialed, cashiered, and dismissed from the army for failing to issue a challenge after he was publicly insulted. This attitude lingered on – Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

even expressed a hope that Lord Cardigan, prosecuted for wounding another in a duel, "would get off easily". The Anglican Church

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

was generally hostile to dueling, but non-conformist sects in particular began to actively campaign against it.

By 1840, dueling had declined dramatically; when the 7th Earl of Cardigan was acquitted on a legal technicality for homicide in connection with a duel with one of his former officers, outrage was expressed in the media, with ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' alleging that there was deliberate, high-level complicity to leave the loophole in the prosecution and reporting the view that "in England there is one law for the rich and another for the poor," and '' The Examiner'' describing the verdict as "a defeat of justice."

The last-known fatal duel between Englishmen in England occurred in 1845, when James Alexander Seton had an altercation with Henry Hawkey over the affections of his wife, leading to a duel at Browndown, near Gosport

Gosport ( ) is a town and non-metropolitan district with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in Hampshire, England. At the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 Census, the town had a population of 70,131 and the district had a pop ...

. However, the last-known fatal duel to occur in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

was between two French political refugees, Frederic Cournet and Emmanuel Barthélemy near Englefield Green

Englefield Green is a large village in the Borough of Runnymede, Surrey, England, approximately west of central London. It is home to Runnymede Meadow, The Commonwealth Air Forces Memorial, The Savill Garden,and Royal Holloway, University of L ...

in 1852; the former was killed. In both cases, the winners of the duels, Hawkey and Barthélemy, were tried for murder. But Hawkey was acquitted and Barthélemy was convicted only of manslaughter; he served seven months in prison.

Dueling also began to be criticized in America in the late 18th century; Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

denounced the practice as uselessly violent, and George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

encouraged his officers to refuse challenges during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

because he believed that the death by dueling of officers would have threatened the success of the war effort.

In the early nineteenth century, American writer and activist John Neal

John Neal (August 25, 1793 – June 20, 1876) was an American writer, critic, editor, lecturer, and activist. Considered both eccentric and influential, he delivered speeches and published essays, novels, poems, and short stories between the 1 ...

took up dueling as his earliest reform issue, attacking the institution in his first novel, ''Keep Cool'' (1817) and referring to it in an essay that same year as "the unqualified evidence of manhood". Ironically, Neal was challenged to a duel by a fellow Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

lawyer for insults published in his 1823 novel ''Randolph''. He refused and mocked the challenge in his next novel, ''Errata'', published the same year.

Reports of dueling gained in popularity in the first half of the 19th century especially in the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

and the states of the Old Southwest

The "Old Southwest" is an informal name for the southwestern frontier territories of the United States from the American Revolutionary War , through the early 1800s, at which point the US had acquired the Louisiana Territory, pushing the sout ...

. However, in this regional context, the term ''dueling'' had severely degenerated from its original 18th-century definition as a formal social custom among the wealthy classes, using fixed rules of conduct. Instead, 'dueling' was used by the contemporary press of the day to refer to any melee

A melee ( or ) is a confused hand-to-hand combat, hand-to-hand fight among several people. The English term ''melee'' originated circa 1648 from the French word ' (), derived from the Old French ''mesler'', from which '':wikt:medley, medley'' and ...

knife or gun fight between two contestants, where the clear object was simply to kill one's opponent.Cassidy, William L., ''The Complete Book Of Knife Fighting'', , (1997), pp. 9–18, 27–36: In some states the popularity of certain knives such as the ''Bowie'' and ''Arkansas Toothpick'' was such that schools were established to teach their use in knife fighting 'duels', further popularizing such knives and compelling authorities to pass legislation severely restricting such schools.

Dueling began an irreversible decline in the aftermath of the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. Even in the South, public opinion

Public opinion, or popular opinion, is the collective opinion on a specific topic or voting intention relevant to society. It is the people's views on matters affecting them.

In the 21st century, public opinion is widely thought to be heavily ...

increasingly came to regard the practice as little more than bloodshed.

Prominent 19th-century duels

United States

The most notorious American duel is the Burr–Hamilton duel, in which notableFederalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters call themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of deep ...

and former Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

was fatally wounded by his political rival, the sitting Vice President of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest ranking office in the Executive branch of the United States government, executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks f ...

Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician, businessman, lawyer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805 d ...

.

Another American politician, Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, later to serve as a General Officer

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

in the U.S. Army and to become the seventh president, fought two duels, though some legends claim he fought many more. On May 30, 1806, he killed prominent duellist Charles Dickinson, suffering himself from a chest wound that caused him a lifetime of pain. Jackson also reportedly engaged in a bloodless duel with a lawyer and in 1803 came very near dueling with John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

. Jackson also engaged in a frontier brawl (not a duel) with Thomas Hart Benton in 1813.

In 1827, during the Sandbar Fight, James Bowie

James Bowie ( ) (April 10, 1796 – March 6, 1836) was an American military officer, landowner and slave trader who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution. He was among the Americans who died at the Battle of the Alamo. Stories of him ...

was involved in an arranged pistol duel that quickly escalated into a knife-fighting melee

A melee ( or ) is a confused hand-to-hand combat, hand-to-hand fight among several people. The English term ''melee'' originated circa 1648 from the French word ' (), derived from the Old French ''mesler'', from which '':wikt:medley, medley'' and ...

, not atypical of American practices at the time.

On September 22, 1842, future President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, at the time an Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

state legislator

A legislator, or lawmaker, is a person who writes and passes laws, especially someone who is a member of a legislature. Legislators are often elected by the people, but they can be appointed, or hereditary. Legislatures may be supra-nat ...

, met to duel with state auditor James Shields, but friends intervened and persuaded them against it.

In 1864, American writer Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

, then a contributor to the '' New York Sunday Mercury'', narrowly avoided fighting a duel with a rival newspaper editor, apparently through the intervention of his second, who exaggerated Twain's prowess with a pistol.

France

In 1808, two Frenchmen are said to have fought in balloons over Paris, each attempting to shoot and puncture the other's balloon. One duellist is said to have been shot down and killed with his second. On 30 May 1832, French mathematicianÉvariste Galois

Évariste Galois (; ; 25 October 1811 – 31 May 1832) was a French mathematician and political activist. While still in his teens, he was able to determine a necessary and sufficient condition for a polynomial to be solvable by Nth root, ...

was mortally wounded in a duel at the age of twenty, cutting short his promising mathematical career. He spent the night before the duel writing mathematics; the inclusion of a note claiming that he did not have time to finish a proof spawned the urban legend

Urban legend (sometimes modern legend, urban myth, or simply legend) is a genre of folklore concerning stories about an unusual (usually scary) or humorous event that many people believe to be true but largely are not.

These legends can be e ...

that he wrote his most important results on that night.

In 1843, two Frenchmen are said to have fought a duel by means of throwing billiard balls at each other.

Ireland

Irish political leaderDaniel O'Connell

Daniel(I) O’Connell (; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilisation of Catholic Irelan ...

killed John D'Esterre in a duel in February 1815. O'Connel offered D'Esterre's widow a pension equal to the amount her husband had been earning at the time, but the Corporation of Dublin, of which D'Esterre had been a member, rejected O'Connell's offer and voted the promised sum to D'Esterre's wife themselves. D'Esterre's wife consented to accept an allowance for her daughter, which O'Connell regularly paid for more than thirty years until his death. The memory of the duel haunted him for the remainder of his life.

Russia

The works of Russian poetAlexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

contained a number of duels, notably Onegin's duel with Lensky in ''Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' (, Reforms of Russian orthography, pre-reform Russian: Евгеній Онѣгинъ, романъ въ стихахъ, ) is a novel in verse written by Alexander Pushkin. ''Onegin'' is considered a classic of ...

''. These turned out to be prophetic, as Pushkin himself was mortally wounded in a controversial duel with Georges d'Anthès, a French officer rumored to be his wife's lover. D'Anthès, who was accused of cheating in this duel, married Pushkin's sister-in-law and went on to become a French minister and senator.

Germany

In the 1860s,Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

was reported to have challenged Rudolf Virchow

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow ( ; ; 13 October 18215 September 1902) was a German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician. He is known as "the father of modern pathology" and as the founder o ...

to a duel. Virchow, being entitled to choose the weapons, chose two pork sausages, one infected with the roundworm ''Trichinella

''Trichinella'' is the genus of parasitic roundworms of the phylum Nematoda that cause trichinosis (also known as trichinellosis). Members of this genus are often called trichinella or trichina worms. A characteristic of Nematoda is the one-way ...

''; the two would each choose and eat a sausage. Bismarck reportedly declined. The story could be apocryphal, however.

Scotland

In Scotland, James Stuart of Dunearn, was tried and acquitted after a duel that fatally wounded Sir Alexander Boswell. George Buchan published his own examination of arguments in favour of duelling alongside an account of the trial, taken in shorthand. Other duels have been fought in Scotland mostly between soldiers or the gentry with several subsequently brought to the law courts.Canada

The last known fatal duel inOntario

Ontario is the southernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Located in Central Canada, Ontario is the Population of Canada by province and territory, country's most populous province. As of the 2021 Canadian census, it ...

was in Perth, in 1833, when Robert Lyon challenged John Wilson to a pistol duel after a quarrel over remarks made about a local school teacher, whom Wilson married after Lyon was killed in the duel. Victoria, British Columbia

Victoria is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of British Columbia, on the southern tip of Vancouver Island off Canada's Pacific Ocean, Pacific coast. The city has a population of 91,867, and the Gre ...

was known to have been the centre of at least two duels near the time of the gold rush. One involved a British arrival by the name of George Sloane, and an American, John Liverpool, both arriving via San Francisco in 1858. In a duel by pistols, Sloane was fatally injured and Liverpool shortly returned to the US. The fight originally started on board the ship over a young woman, Miss Bradford, and then carried on later in Victoria's tent city. Another duel, involving a Mr. Muir, took place around 1861, but was moved to a US island near Victoria.

Decline in the 19th and 20th centuries

Duels had mostly ceased to be fought to the death by the late 19th century. By the start ofWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, dueling had not only been made illegal almost everywhere in the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and state (polity), states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also const ...

, but was also widely seen as an anachronism. Military establishments in most countries frowned on dueling because officers were the main contestants. Officers were often trained at military academies at government expense; when officers killed or disabled one another it imposed an unnecessary financial and leadership strain on a military organization, making dueling unpopular with high-ranking officers.

With the end of the duel, the dress sword lost its position as an indispensable part of a gentleman's wardrobe, a development described as an "archaeological terminus" by Ewart Oakeshott

Ronald Ewart Oakeshott (25 May 1916 – 30 September 2002) was a British illustrator, collector, and amateur historian who wrote prodigiously on medieval arms and armour. He was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, a Founder Member of the A ...

, concluding the long period during which the sword

A sword is an edged and bladed weapons, edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter ...

had been a visible attribute of the free man, beginning as early as three millennia ago with the Bronze Age sword

Bronze Age swords appeared from around the 17th century BC, in the Black Sea and Aegean regions, as a further development of the dagger. They were replaced by iron swords during the early part of the 1st millennium BC.

Typical Bronze Age sword ...

.

Legislation

Charles I outlawed dueling inAustria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

in 1917. Germany (the various states of the Holy Roman Empire) has a history of laws against dueling going back to the late medieval period, with a large amount of legislation () dating from the period after the Thirty Years' War. Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

outlawed dueling in 1851, and the law was inherited by the of the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

after 1871.Franz Liszt, ''Lehrbuch des Deutschen Strafrechts'', 13th ed., Berlin (1903)§ 93. 4. Der Zweikampf

(pp. 327–333).

Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the Ap ...

in the encyclica (1891) asked the bishops of Germany and Austria-Hungary to impose penalties on duellists. In Nazi-era Germany, legislations on dueling were tightened in 1937. After World War II, West German

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republic after its capital c ...

authorities persecuted academic fencing

Academic fencing () or is the traditional kind of fencing practiced by some student corporations () in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Latvia, Estonia, and, to a minor extent, in Belgium, Lithuania, and Poland. It is a traditional, strictly re ...

as duels until 1951, when a Göttingen

Göttingen (, ; ; ) is a college town, university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the Capital (political), capital of Göttingen (district), the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. According to the 2022 German census, t ...

court established the legal distinction between academic fencing and dueling.

In 1839, after the death of a congressman, dueling was outlawed in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

A constitutional amendment was even proposed for the federal constitution to outlaw dueling. Some U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

s' constitutions, such as West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

's, contain explicit prohibitions on dueling to this day. In Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

, the state constitution of 1891, which remains in effect, mandates that all state and local officeholders, attorneys who are members of the state bar and delegates to the Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

must swear or affirm that they had never engaged in a duel with deadly weapons, acted as a second in a duel with deadly weapons or otherwise aided or assisted anyone thus offending. Other U.S. states, like Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

until the late 1970s, formerly had prohibitions on dueling in their state constitutions, but later repealed them, whereas others, such as Iowa, constitutionally prohibited known duelers from holding political office until the early 1990s.

From 1921 until 1992, Uruguay

Uruguay, officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast, while bordering the Río de la Plata to the south and the A ...

was one of the few places where duels were fully legal. During that period, a duel was legal in cases where "an honor tribunal of three respectable citizens, one chosen by each side and the third chosen by the other two, had ruled that sufficient cause for a duel existed".

Pistol sport dueling

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pistol dueling became popular as a sport in France. The duelists were armed with conventional pistols, but the cartridges had wax bullets and were without any powder charge; the bullet was propelled only by the explosion of the cartridge's primer.

Participants wore heavy, protective clothing and a metal helmet with a glass eye-screen. The pistols were fitted with a shield that protected the firing hand.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pistol dueling became popular as a sport in France. The duelists were armed with conventional pistols, but the cartridges had wax bullets and were without any powder charge; the bullet was propelled only by the explosion of the cartridge's primer.

Participants wore heavy, protective clothing and a metal helmet with a glass eye-screen. The pistols were fitted with a shield that protected the firing hand.

=Olympic dueling

= Pistol dueling was an associate (non-medal) event at the1908 Summer Olympics

The 1908 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the IV Olympiad and also known as London 1908) were an international multi-sport event held in London, England, from 27 April to 31 October 1908. The 1908 Games were originally schedu ...

in London.

Late survivals

Dueling culture survived inFrance

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Italy, and Latin America well into the 20th century. After World War II, duels had become rare even in France, and those that still occurred were covered in the press as eccentricities. Duels in France in this period, while still taken seriously as a matter of honor, were not fought to the death. They consisted of fencing with the épée mostly in a fixed distance with the aim of drawing blood from the opponent's arm.

In 1949, former Vichy official Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour

Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour (; 12 October 1907 – 29 September 1989) was a French lawyer and Far-right politics, far-right politician. Elected to the National Assembly (France), National Assembly in 1936, he initially collaborated with the Vichy ...

fought school teacher Roger Nordmann.

The last known duel in France took place in 1967, when Socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

Deputy and Mayor of Marseille Gaston Defferre

Gaston Defferre (14 September 1910 – 7 May 1986) was a French Socialist politician. He served as mayor of Marseille for 33 years until his death in 1986. He was minister for overseas territories in Guy Mollet’s socialist government in 1956 ...

insulted Gaullist

Gaullism ( ) is a French political stance based on the thought and action of World War II French Resistance leader Charles de Gaulle, who would become the founding President of the Fifth French Republic. De Gaulle withdrew French forces from t ...

Deputy René Ribière at the French Parliament

The French Parliament (, ) is the Bicameralism, bicameral parliament of the French Fifth Republic, consisting of the Senate (France), Senate (), and the National Assembly (France), National Assembly (). Each assembly conducts legislative sessi ...

and was subsequently challenged to a duel fought with swords. Ribière lost the duel, having been wounded twice. In Uruguay, a pistol duel was fought in 1971 between Danilo Sena and Enrique Erro, in which neither of the combatants was injured.

Various modern jurisdictions still retain mutual combat laws, which allow disputes to be settled via consensual unarmed combat, which are essentially unarmed duels, though it may still be illegal for such fights to result in grievous bodily harm or death. Few if any modern jurisdictions allow armed duels.

Rules

Offence and satisfaction

The traditional situation that led to a duel often happened after a perceived offense, whether real or imagined, when one party would demand satisfaction from the offender. The demand was commonly symbolized by an inescapably insulting gesture, such as throwing a glove to the ground before the offender. Usually, challenges were delivered in writing by one or more close friends who acted as "seconds". The challenge, written in formal language, laid out the real or imagined grievances and a demand for satisfaction. The challenged party then had the choice of accepting or refusing the challenge. Grounds for refusing the challenge could include that it was frivolous, or that the challenger was not generally recognized as a "gentleman" since dueling was limited to persons of equal social status. However, care had to be taken before declining a challenge, as it could result in accusations of cowardice or be perceived as an insult to the challenger's seconds if it was implied that they were acting on behalf of someone of low social standing. Participation in a duel could be honorably refused on account of a major difference in age between the parties and, to a lesser extent, in cases of social inferiority on the part of the challenger. Such inferiority had to be immediately obvious, however. As author Bertram Wyatt-Brown states, "with social distinctions often difficult to measure", most men could not escape on such grounds without the appearance of cowardice. Once a challenge was accepted, if not done already, both parties (known as "principals") would appoint trusted representatives to act as their seconds with no further direct communication between the principals being allowed until the dispute was settled. The seconds had a number of responsibilities, of which the first was to do all in their power to avert bloodshed provided their principal's honor was not compromised. This could involve back and forth correspondence about a mutually agreeable lesser course of action, such as a formal apology for the alleged offense. In the event that the seconds failed to persuade their principals to avoid a fight, they then attempted to agree on terms for the duel that would limit the chance of a fatal outcome, consistent with the generally accepted guidelines for affairs of honor. The exact rules or etiquette for dueling varied by time and locale but were usually referred to as the code duello. In most cases, the challenged party had the choice of weapons, with swords being favored in many parts of continental Europe and pistols in the United States and Great Britain. It was the job of the seconds to make all of the arrangements in advance, including how long the duel would last and what conditions would end the duel. Often sword duels were only fought until blood was drawn, thus severely limiting the likelihood of death or grave injury since a scratch could be considered as satisfying honor. In pistol duels, the number of shots to be permitted and the range were set out. Care was taken by the seconds to ensure the ground chosen gave no unfair advantage to either party. A doctor or surgeon was usually arranged to be on hand. Other things often arranged by the seconds could go into minute details that might seem odd in the modern world, such as the dress code (duels were often formal affairs), the number and names of any other witnesses to be present and whether or not refreshments would be served.Field of honor

The chief criteria for choosing the field of honor were isolation, to avoid discovery and interruption by the authorities; and jurisdictional ambiguity, to avoid legal consequences. Islands in rivers dividing two jurisdictions were popular dueling sites; the cliffs below Weehawken on the Hudson River where the Hamilton–Burr duel occurred were a popular field of honor for New York duelists because of the uncertainty of whether New York or New Jersey had jurisdiction. Duels traditionally took place at dawn, when the poor light would make the participants less likely to be seen, and to force an interval for reconsideration or sobering up. For some time before the mid-18th century, swordsmen dueling at dawn often carried lanterns to see each other. This happened so regularly that fencing manuals integrated lanterns into their lessons. An example of this is using the lantern to parry blows and blind the opponent. The manuals sometimes show the combatants carrying the lantern in the left hand wrapped behind the back, which is still one of the traditional positions for the off-hand in modern fencing.Conditions

At the choice of the offended party, the duel could be fought to a number of conclusions: * To first blood, in which case the duel would be ended as soon as one man was wounded, even if the wound was minor. * Until one man was so severely wounded as to be physically unable to continue the duel. * To the death (or ), in which case there would be no satisfaction until one party was mortally wounded. * In the case of pistol duels, each party would fire one shot. If neither man was hit and if the challenger stated that he was satisfied, the duel would be declared over. If the challenger was not satisfied, a pistol duel could continue until one man was wounded or killed, but to have more than three exchanges of fire was considered barbaric, and, on the rare occasion that no hits were achieved, somewhat ridiculous. Under the latter conditions, one or both parties could intentionally miss in order to fulfill the conditions of the duel, without loss of either life or honor. However, doing so, known as deloping, could imply that one's opponent was not worth shooting. This practice occurred despite being expressly banned by the Irish of 1777. Rule XII stated: "No dumb shooting or firing in the air is admissible in any case ... children's play must be dishonourable on one side or the other, and is accordingly prohibited." Practices varied, however, but unless the challenger was of a higher social standing, such as a baron or prince challenging a knight, the person being challenged was allowed to decide the time and weapons used in the duel. The offended party could stop the duel at any time if he deemed his honor satisfied. In some duels, the seconds would take the place of the primary duelist if the primary was not able to finish the duel. This was usually done in duels with swords, where one's expertise was sometimes limited. The second would also act as a witness.Pistol duel

There were various methods of pistol dueling. The mode where the two duelists stood back-to-back, walked away from each other for a set number of paces before turning and firing was known as the "French" method.Hoptin (2011), p. 80 Another method required the duelists to stand still at an agreed distance and fire simultaneously on a signal – this was the type of duel favored in Britain. A variant of this required the duelists to take turns to shoot, with the challenger shooting first or the right of first shot being decided by a coin toss.

The distance at which the pistols were fired might depend on local custom, the wishes of the duelists or sometimes the severity of the insult. The American dueling code of 1838 suggested a distance between 10 and 20 paces.Hoptin (2011), p. 81 There were incidences of pistol duels taking place at just two or three paces, with a virtual certainty of one or both duelists being injured or killed.Hoptin (2011), p. 82

A method popular in Continental Europe was known as a ''barrier duel'' or a duel ("at pleasure"); it did not have a set shooting distance. The two duelists began some distance apart. Between them there were two lines on the ground separated by an agreed distance – this constituted the barrier and they were forbidden to cross it. After the signal to begin, they could advance towards the barrier to close the distance and were permitted to fire at any time. However, the one that shot first was required to stand still and allow his opponent to walk right up to his barrier line and fire back at leisure.Hoptin (2011), pp. 85–90

Many historical duels were prevented by the difficulty of arranging the "". In the instance of

There were various methods of pistol dueling. The mode where the two duelists stood back-to-back, walked away from each other for a set number of paces before turning and firing was known as the "French" method.Hoptin (2011), p. 80 Another method required the duelists to stand still at an agreed distance and fire simultaneously on a signal – this was the type of duel favored in Britain. A variant of this required the duelists to take turns to shoot, with the challenger shooting first or the right of first shot being decided by a coin toss.

The distance at which the pistols were fired might depend on local custom, the wishes of the duelists or sometimes the severity of the insult. The American dueling code of 1838 suggested a distance between 10 and 20 paces.Hoptin (2011), p. 81 There were incidences of pistol duels taking place at just two or three paces, with a virtual certainty of one or both duelists being injured or killed.Hoptin (2011), p. 82

A method popular in Continental Europe was known as a ''barrier duel'' or a duel ("at pleasure"); it did not have a set shooting distance. The two duelists began some distance apart. Between them there were two lines on the ground separated by an agreed distance – this constituted the barrier and they were forbidden to cross it. After the signal to begin, they could advance towards the barrier to close the distance and were permitted to fire at any time. However, the one that shot first was required to stand still and allow his opponent to walk right up to his barrier line and fire back at leisure.Hoptin (2011), pp. 85–90

Many historical duels were prevented by the difficulty of arranging the "". In the instance of Richard Brocklesby

Richard Brocklesby (11 August 1722 – 11 December 1797), an English physician, was born at Minehead, Somerset.

He was educated at Ballitore, in Ireland, where Edmund Burke was one of his school fellows, studied medicine at Edinburgh, an ...

, the number of paces could not be agreed upon; and in the affair between Mark Akenside and Ballow, one had determined never to fight in the morning, and the other that he would never fight in the afternoon. John Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English Radicalism (historical), radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlese ...

, "who did not stand upon ceremony in these little affairs", when asked by Lord Talbot how many times they were to fire, replied, "just as often as your Lordship pleases; I have brought a bag of bullets and a flask of gunpowder."

Western traditions

Europe

Great Britain and Ireland

The duel arrived at the end of the 16th century with the influx of Italian honor and courtesy literature – most notablyBaldassare Castiglione

Baldassare Castiglione, Count of Casatico (; 6 December 1478 – 2 February 1529),Dates of birth and death, and cause of the latter, fro, ''Italica'', Rai International online. was an Italian courtier, diplomat, soldier and a prominent Renaissan ...

's '' Libro del Cortegiano'' (Book of the Courtier), published in 1528, and Girolamo Muzio's ''Il Duello'', published in 1550. These stressed the need to protect one's reputation and social mask and prescribed the circumstances under which an insulted party should issue a challenge.

The word ''duel'' was introduced in the 1590s, modeled after Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. It was also the administrative language in the former Western Roman Empire, Roman Provinces of Mauretania, Numidi ...

''duellum'' (an archaic Latin form of ''bellum'' "war", but associated by popular etymology with ''duo'' "two", hence "one-on-one combat").

Soon domestic literature was being produced such as Simon Robson's ''The Courte of Ciuill Courtesie'', published in 1577. Dueling was further propagated by the arrival of Italian fencing masters such as Rocco Bonetti and Vincento Saviolo. By the reign of James I dueling was well entrenched within a militarized peerage – one of the most important duels being that between Edward Bruce, 2nd Lord Kinloss and Edward Sackville (later the 4th Earl of Dorset) in 1613, during which Bruce was killed. James I encouraged Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...