Dnieper Cossacks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the

Wild Field (ДИКЕ ПОЛЕ)

. ''Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine''. 2004 Zaporozhian Host became established as a well-respected political entity with a parliamentary system of government. During the course of the 16th, 17th and well into the 18th century, the Zaporozhian Cossacks were a strong political and military force that challenged the authority of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the

In the 16th century, with the dominance of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth extending south, the Zaporozhian Cossacks were mostly, if tentatively, regarded by the

In the 16th century, with the dominance of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth extending south, the Zaporozhian Cossacks were mostly, if tentatively, regarded by the  During this time, the

During this time, the  The waning loyalty of the Cossacks and the szlachta's arrogance towards them resulted in several Cossack uprisings against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the early 17th century. Finally, the King's adamant refusal to bow to the Cossacks' demand to expand the Cossack Registry was the last straw that prompted the largest and most successful of these: the

The waning loyalty of the Cossacks and the szlachta's arrogance towards them resulted in several Cossack uprisings against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the early 17th century. Finally, the King's adamant refusal to bow to the Cossacks' demand to expand the Cossack Registry was the last straw that prompted the largest and most successful of these: the

The Zaporozhian Host as a military-political establishment developed based upon unique traditions and customs called the Cossack Code, which was formed mostly among the cossacks of Zaporozhian Host over decades. The host had its own military and territorially administrative division: 38

The Zaporozhian Host as a military-political establishment developed based upon unique traditions and customs called the Cossack Code, which was formed mostly among the cossacks of Zaporozhian Host over decades. The host had its own military and territorially administrative division: 38  The Zaporozhian Host, while being closely associated with the

The Zaporozhian Host, while being closely associated with the

The seal of the Zaporozhian Host was produced in a round form out of silver with a depiction of a Cossack in a gabled cap on a head, in

The seal of the Zaporozhian Host was produced in a round form out of silver with a depiction of a Cossack in a gabled cap on a head, in

After the

After the

Over the years the friction between the Cossacks and the Russian tsarist government lessened, and privileges were traded for a reduction in Cossack autonomy. The Ukrainian Cossacks who did not side with Mazepa elected as Hetman

Over the years the friction between the Cossacks and the Russian tsarist government lessened, and privileges were traded for a reduction in Cossack autonomy. The Ukrainian Cossacks who did not side with Mazepa elected as Hetman

Today, most of the Kuban Cossacks, modern descendants of the Zaporozhians, remain loyal towards Russia. Many fought in the local conflicts following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and today, just like before the revolution when they made up the private guard of the Emperor, the majority of the Kremlin Presidential Regiment is made up of Kuban Cossacks.

For the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the

Today, most of the Kuban Cossacks, modern descendants of the Zaporozhians, remain loyal towards Russia. Many fought in the local conflicts following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and today, just like before the revolution when they made up the private guard of the Emperor, the majority of the Kremlin Presidential Regiment is made up of Kuban Cossacks.

For the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Yanukovych cancels three decrees on Ukrainian Cossacks

Zaporizhia

at the ''

Zaporozhian Cossacks

at the ''Encyclopedia of Ukraine''

at the ''Encyclopedia of Ukraine'' {{Authority control * Cossacks Cossack hosts Early modern history of Ukraine Ethnic groups in Ukraine History of the Cossacks in Ukraine Zaporizhzhia Military history of Zaporizhzhia

Zaporozhian Host

The Zaporozhian Host (), or Zaporozhian Sich () is a term for a military force inhabiting or originating from Zaporizhzhia, the territory in what is Southern and Central Ukraine today, beyond the rapids of the Dnieper River, from the 15th to th ...

(), were Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossacks

Registered Cossacks (, ) comprised special Cossack units of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth army in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Registered Cossacks became a military formation of the Commonwealth army beginning in 1572 soon after the ...

and Sloboda Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossacks played an important role in the history of Ukraine

The history of Ukraine spans thousands of years, tracing its roots to the Pontic–Caspian steppe, Pontic steppe—one of the key centers of the Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages, Indo-European migrations, and early domestication of the horse, hors ...

and the ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is the formation and development of an ethnic group. This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th-century neologism that was later introduce ...

of Ukrainians

Ukrainians (, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. Their native tongue is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, and the majority adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, forming the List of contemporary eth ...

.

The Zaporozhian Sich

The Zaporozhian Sich (, , ; also ) was a semi-autonomous polity and proto-state of Zaporozhian Cossacks that existed between the 16th to 18th centuries, for the latter part of that period as an autonomous stratocratic state within the Cossa ...

grew rapidly in the 15th century from serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed dur ...

fleeing the more controlled parts of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

. The least controlled region, that was located between the Dniester

The Dniester ( ) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and then through Moldova (from which it more or less separates the breakaway territory of Transnistria), finally discharging into the Black Sea on Uk ...

and mid-Volga

The Volga (, ) is the longest river in Europe and the longest endorheic basin river in the world. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchment ...

was first known from the 15th century as the '' Wild Fields'', which was subject to colonization by the Zaporozhian Cossacks.Shcherbak, V.Wild Field (ДИКЕ ПОЛЕ)

. ''Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine''. 2004 Zaporozhian Host became established as a well-respected political entity with a parliamentary system of government. During the course of the 16th, 17th and well into the 18th century, the Zaporozhian Cossacks were a strong political and military force that challenged the authority of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the

Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia, also known as the Tsardom of Moscow, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of tsar by Ivan the Terrible, Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter the Great in 1721.

...

, and the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

.

The host

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

* Host Island, in the Wilhelm Archipelago, Antarctica

People

* ...

went through a series of conflicts and alliances involving the three powers, including supporting an uprising in the 18th century. Their leader signed a treaty with the Russians. This group was forcibly disbanded in the late 18th century by the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, with much of the population relocated to the Kuban

Kuban ( Russian and Ukrainian: Кубань; ) is a historical and geographical region in the North Caucasus region of southern Russia surrounding the Kuban River, on the Black Sea between the Don Steppe, the Volga Delta and separated fr ...

region on the south edge of the Russian Empire, while others founded cities in southern Ukraine and eventually became state peasants. The Cossacks served a valuable role of conquering the Caucasian tribes and in return enjoyed considerable freedom granted by the Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

s.

The name comes from the location of their fortress, the Sich, in ( "land beyond the rapids"), from Ukrainian "beyond" and "rapids

Rapids are sections of a river where the river bed has a relatively steep stream gradient, gradient, causing an increase in water velocity and turbulence. Flow, gradient, constriction, and obstacles are four factors that are needed for a rapid t ...

".

Origins

It is not clear when the first Cossack communities on the Lower Dnieper began to form. There are signs and stories of similar people living in theEurasian Steppe

The Eurasian Steppe, also called the Great Steppe or The Steppes, is the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands biome. It stretches through Manchuria, Mongolia, Xinjiang, Kazakhstan, Siberia, Europea ...

as early as the 12th century. At that time they were not called Cossacks, since ''cossack'' is a word that also in Turkic language means a "free man" which shares its etymology with the ethnic name " Kazakh". It later became a Ukrainian and Russian word for " freebooter." The steppes to the north of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

were inhabited by nomadic tribes such as the Cumans

The Cumans or Kumans were a Turkic people, Turkic nomadic people from Central Asia comprising the western branch of the Cumania, Cuman–Kipchak confederation who spoke the Cuman language. They are referred to as Polovtsians (''Polovtsy'') in Ru ...

, Pechenegs

The Pechenegs () or Patzinaks, , Middle Turkic languages, Middle Turkic: , , , , , , ka, პაჭანიკი, , , ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Pečenezi, separator=/, Печенези, also known as Pecheneg Turks were a semi-nomadic Turkic peopl ...

and Khazars

The Khazars ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a nomadic Turkic people who, in the late 6th century CE, established a major commercial empire covering the southeastern section of modern European Russia, southern Ukraine, Crimea, a ...

. The role of these tribes in the ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is the formation and development of an ethnic group. This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th-century neologism that was later introduce ...

of the Cossacks is disputed, although later Cossack sources claimed a Slavicised Khazar ancestry.

There were also groups of people who fled into these wild steppes from the cultivated lands of Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus', also known as Kyivan Rus,.

* was the first East Slavs, East Slavic state and later an amalgam of principalities in Eastern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical At ...

in order to escape oppression or criminal pursuit. Their lifestyle largely resembled that of the people now called Cossacks. They survived chiefly from hunting and fishing and raiding Asiatic tribes for horses and food, but they also mixed with these nomads as well adopting a lot of their cultural traits. In the 16th century, a great organizer, Dmytro Vyshnevetsky, a Ruthenian ( Ukrainian) noble, united these different groups into a strong military organization.

The Zaporozhian Cossacks had various social and ethnic origins but were predominantly made up of escaped serfs who preferred the dangerous freedom of the wild steppes, rather than life under the rule of Polish aristocrats. However, townspeople, lesser noblemen and even Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

also became part of the Cossack host. They had to accept Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

as their religion and adopt its rituals and prayers.

Scientific studies conducted on the Zaporozhian Cossack genetics show that their Y-chromosomal genetic makeup forms the southern fragment of East Slavic population, with low levels to absence of Caucasian and Asian component in their gene pool.

The nomadic hypothesis was that the Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

came from one or more nomadic peoples who at different times lived in the territory of the Northern Black Sea. According to this hypothesis the Cossacks' ancestors were the Scythians

The Scythians ( or ) or Scyths (, but note Scytho- () in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern Iranian peoples, Iranian Eurasian noma ...

, Sarmatians

The Sarmatians (; ; Latin: ) were a large confederation of Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Iranian Eurasian nomads, equestrian nomadic peoples who dominated the Pontic–Caspian steppe, Pontic steppe from about the 5th century BCE to the 4t ...

, Khazars

The Khazars ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a nomadic Turkic people who, in the late 6th century CE, established a major commercial empire covering the southeastern section of modern European Russia, southern Ukraine, Crimea, a ...

, Polovtsy (Cumans), Circassians

The Circassians or Circassian people, also called Cherkess or Adyghe (Adyghe language, Adyghe and ), are a Northwest Caucasian languages, Northwest Caucasian ethnic group and nation who originated in Circassia, a region and former country in t ...

( Adygs), Tatars

Tatars ( )Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

, and others. The nomadic hypothesis of the origin of the Cossacks was formed under the influence of the Polish historical school of the 16th-17th centuries and was connected with the theory of the in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

Sarmatian

The Sarmatians (; ; Latin: ) were a large confederation of Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Iranian Eurasian nomads, equestrian nomadic peoples who dominated the Pontic–Caspian steppe, Pontic steppe from about the 5th century BCE to the 4t ...

origin of the gentry. According to the tradition of deriving the origin of the state or people from a certain people of antiquity, the Cossack chroniclers of the 18th century advocated the Khazar origin of the Cossacks. In the 20th century, the Russian scientist Gumilyov was an apologist for the Polovtsian origin of the Cossacks.

Within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

In the 16th century, with the dominance of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth extending south, the Zaporozhian Cossacks were mostly, if tentatively, regarded by the

In the 16th century, with the dominance of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth extending south, the Zaporozhian Cossacks were mostly, if tentatively, regarded by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

as their subjects. Registered Cossacks

Registered Cossacks (, ) comprised special Cossack units of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth army in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Registered Cossacks became a military formation of the Commonwealth army beginning in 1572 soon after the ...

were a part of the Commonwealth army until 1699.

Around the end of the 16th century, relations between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, which were not cordial to begin with, were further strained by increasing Cossack aggression. From the second part of the 16th century, the Cossacks started raiding Ottoman territories. The Polish government could not control the fiercely independent Cossacks but, since they were nominally subjects of the Commonwealth, it was held responsible for raids by their victims. Reciprocally, the Tatars

Tatars ( )Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

living under the Ottoman rule launched raids in the Commonwealth, mostly in the sparsely inhabited south-east territories of Ukraine. Cossacks, however, were raiding wealthy merchant port cities in the heart of the Ottoman Empire, which were just two days away by boat from the mouth of the in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

Dnieper River

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

.

By 1615 and 1625, Cossacks had managed to raze townships on the outskirts of Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, forcing the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV

Murad IV (, ''Murād-ı Rābiʿ''; , 27 July 1612 – 8 February 1640) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1623 to 1640, known both for restoring the authority of the state and for the brutality of his methods. Murad I ...

to flee his palace. His nephew, Sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

Mehmed IV

Mehmed IV (; ; 2 January 1642 – 6 January 1693), nicknamed as Mehmed the Hunter (), was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1648 to 1687. He came to the throne at the age of six after his father was overthrown in a coup. Mehmed went on to b ...

, fared little better as the recipient of the legendary Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, a ribald response to Mehmed's insistence that the Cossacks submit to his authority. Consecutive treaties between the Ottoman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth called for both parties to keep the Cossacks and Tatars in check, but enforcement was almost non-existent on both sides. In internal agreements, forced by the Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

, the Cossacks agreed to burn their boats and stop raiding

Raiding may refer to:

* The present participle of the verb Raid (disambiguation), which itself has several meanings

* Raid (military)

* Raid (video games), a group of video game players who join forces

* Raiding, Austria, a town in Austria

* Party ...

. However, boats could be rebuilt quickly, and the Cossack lifestyle glorified raids and looting.

During this time, the

During this time, the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

sometimes covertly employed Cossack raiders to ease Ottoman pressure on their own borders. Many Cossacks and Tatars shared an animosity towards each other due to the damage done by raids from both sides. Cossack raids followed by Tatar retaliation, or Tatar raids followed by Cossack retaliation, were an almost regular occurrence. The ensuing chaos and string of conflicts often turned the entire south-eastern Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth border into a low-intensity war zone and led to an escalation of Commonwealth–Ottoman warfare, from the Moldavian Magnate Wars

The Moldavian Magnate Wars, or Moldavian Ventures, refer to the period at the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century when the magnates of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth intervened in the affairs of Moldavia, clashing ...

to the Battle of Cecora (1620)

The Battle of Cecora (also known as the ''Battle of Țuțora'') took place during the Polish–Ottoman War (1620–21) between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (aided by rebel Moldavian troops) and Ottoman forces (backed by Nogais), fough ...

and wars in 1633–34.

Cossack numbers expanded, with Ukrainian peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

s running from serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Attempts by the szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

to turn the Zaporozhian Cossacks into serfs eroded the Cossacks' once fairly strong loyalty towards the Commonwealth. Cossack ambitions to be recognized as equal to the szlachta were constantly rebuffed, and plans for transforming the Polish–Lithuanian Two-Nations Commonwealth into a Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth (with the Ukrainian Cossack people) made little progress, owing to the Cossacks' unpopularity. The Cossacks' strong historic allegiance to the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

put them at odds with the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

-dominated Commonwealth. Tensions increased when Commonwealth policies turned from relative tolerance to the suppression of the Orthodox church, making the Cossacks strongly anti-Catholic, which at that time was synonymous with anti-Polish.

The waning loyalty of the Cossacks and the szlachta's arrogance towards them resulted in several Cossack uprisings against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the early 17th century. Finally, the King's adamant refusal to bow to the Cossacks' demand to expand the Cossack Registry was the last straw that prompted the largest and most successful of these: the

The waning loyalty of the Cossacks and the szlachta's arrogance towards them resulted in several Cossack uprisings against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the early 17th century. Finally, the King's adamant refusal to bow to the Cossacks' demand to expand the Cossack Registry was the last straw that prompted the largest and most successful of these: the Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

, which started in 1648. The uprising became one of a series of catastrophic events known as the Deluge

A deluge is a large downpour of rain, often a flood.

The Deluge refers to the flood narrative in the biblical book of Genesis.

Deluge or Le Déluge may also refer to:

History

*Deluge (history), the Swedish and Russian invasion of the Polish-L ...

, which greatly weakened the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and set the stage for its disintegration one hundred years later. Even though Poland probably had the best cavalry in Europe, their infantry was weak. Since Poland recruited most of its infantry from Ukraine, once this became free from Polish rule, the army of the Commonwealth suffered greatly.

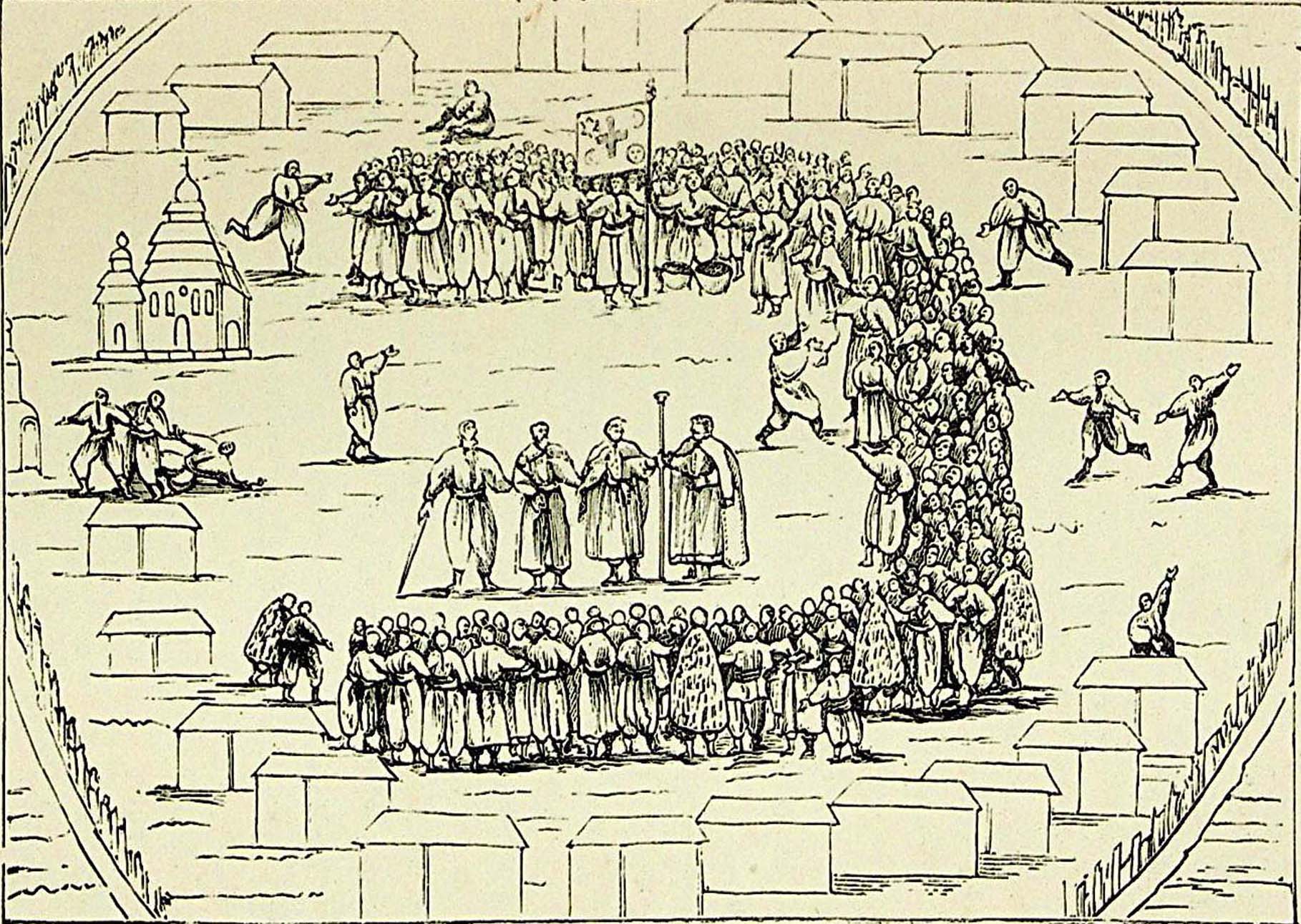

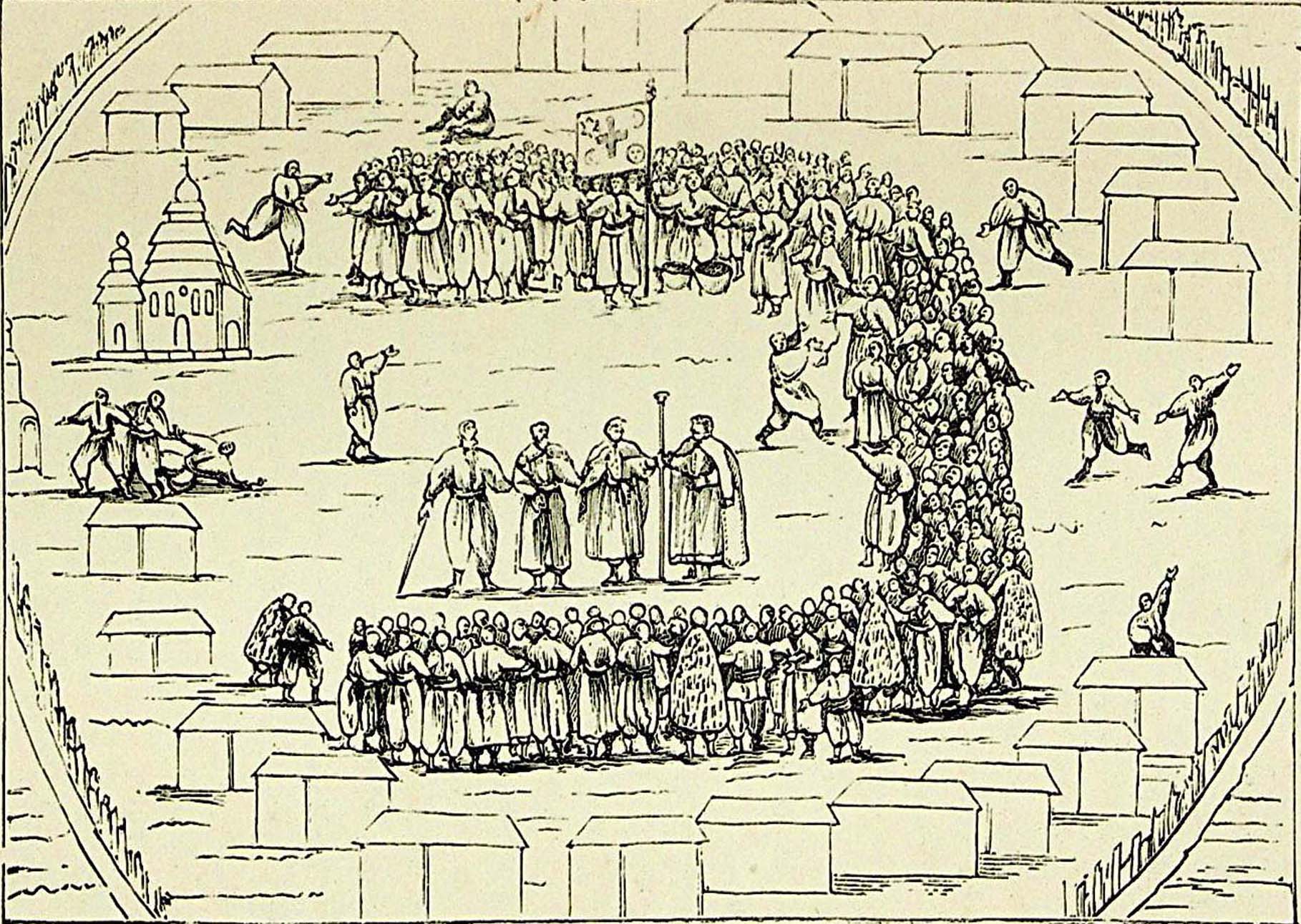

The Koliivshchyna

The Koliivshchyna (; ) was a major haidamaky rebellion that broke out in Right-bank Ukraine in June 1768, caused by the dissatisfaction of peasants with the treatment of Orthodox Christians by the Bar Confederation and serfdom, as well as b ...

was a major haydamak

The haydamaks, also haidamakas or haidamaky or haidamaks ( ''haidamaka''; ''haidamaky'', from and ) were soldiers of Ukrainian Cossack paramilitary outfits composed of commoners (peasants, craftsmen), and impoverished noblemen in the easter ...

rebellion that broke out in right-bank Ukraine

The Right-bank Ukraine is a historical and territorial name for a part of modern Ukraine on the right (west) bank of the Dnieper River, corresponding to the modern-day oblasts of Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Kirovohrad, as well as the western parts o ...

in June 1768. It was caused by the dissatisfaction of peasants and Cossacks with the treatment of Orthodox Christians by the Bar Confederation

The Bar Confederation (; 1768–1772) was an association of Polish nobles (''szlachta'') formed at the fortress of Bar, Ukraine, Bar in Podolia (now Ukraine), in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polish–Lithuanian C ...

. Zaporozhian Cossack Maksym Zalizniak

Maksym Zalizniak (), (born early 1740s in Medvedivka near Chyhyryn - date and place of death unknown, after 1768) was a Ukrainian Cossack and leader of the Koliivshchyna rebellion.

History

Zalizniak was born in a poor peasant family of Ort ...

was one of the leaders of the rebellion.

Organization

The Zaporozhian Host as a military-political establishment developed based upon unique traditions and customs called the Cossack Code, which was formed mostly among the cossacks of Zaporozhian Host over decades. The host had its own military and territorially administrative division: 38

The Zaporozhian Host as a military-political establishment developed based upon unique traditions and customs called the Cossack Code, which was formed mostly among the cossacks of Zaporozhian Host over decades. The host had its own military and territorially administrative division: 38 kurin

Kurin () has two definitions: a military and administrative unit of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, Black Sea Cossack Host, and others; and of a type of housing (see below).

In the administrative definition, a kurin usually consisted of a few hundred ...

s (sotnia

A sotnia ( Ukrainian and , ) was a military unit and administrative division in some Slavic countries.

Sotnia, deriving back to 1248, has been used in a variety of contexts in both Ukraine and Russia to this day. It is a helpful word to create ...

) and five to eight ''palanka''s (territorial districts) as well as an original system of administration with three levels: military leaders, military officials, leaders of march and palankas. All officership (military starshyna) was elected by the General Military Council for a year on January 1. Based on the same customs and traditions the rights and duties of officers were explicitly codified. The Zaporozhian Host developed an original judicial system, at the base of which lay the customary Cossack Code. The norms of the code were affirmed by those social relations that have developed among cossacks. Some sources refer to the Zaporozhian Sich as a "cossack republic", as the highest power in it belonged to the assembly of all its members, and because its leaders (''starshina

( rus, Старшина, p=stərʂɨˈna, a=Ru-старшина.ogg or ) is a senior military rank or designation in the military forces of some Slavs, Slavic states, and a historical military designation. Depending on a country, it had differen ...

'') were elected.

Officially the leader of Zaporozhian Host never carried the title of hetman

''Hetman'' is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders (comparable to a field marshal or imperial marshal in the Holy Roman Empire). First used by the Czechs in Bohemia in the 15th century, ...

, while all leaders of Cossack formations were unofficially referred to as one. The highest body of administration in the Zaporozhian Host was the ''Sich Rada'' (council). The council was the highest legislative, administrative, and judicial body of the Zaporozhian Host. Decisions of the council were considered the opinion of the whole host and obligated to its execution each member of the cossack comradeship. At Sich Rada were reviewed issues of internal and foreign policies, conducted elections of military ''starshina'', division of assigned land, punishment of criminals who committed the worst crimes etc.

The Zaporozhian Host, while being closely associated with the

The Zaporozhian Host, while being closely associated with the Cossack Hetmanate

The Cossack Hetmanate (; Cossack Hetmanate#Name, see other names), officially the Zaporozhian Host (; ), was a Ukrainian Cossacks, Cossack state. Its territory was located mostly in central Ukraine, as well as in parts of Belarus and southwest ...

, had its own administration and orders. For military operations, cossacks of the host organized into ''Kish''. Kish is an old term for a reinforced camp that was used in the 11th-16th centuries and later adopted by cossacks. Kish was the central body of government in Sich under jurisdiction of which were administrative, military, financial, legal, and other affairs. Kish was elected on annual bases at the Sich Rada (Black Rada). Black Rada was a council of all Cossacks. Kish elections were taken place either on 1 January, 1 October (Intercession of the Theotokos

The Intercession of the Theotokos, or the Protection of Our Most Holy Lady Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary, is a Christian feast of the Mother of God celebrated in the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches on October 14 (Julian calend ...

holiday - Pokrova), or on the 2nd-3rd day of Easter.

There was a cossack military court, which severely punished violence and stealing among compatriots, bringing women to the Sich, consumption of alcohol in periods of conflict, etc. There were also churches and school

A school is the educational institution (and, in the case of in-person learning, the Educational architecture, building) designed to provide learning environments for the teaching of students, usually under the direction of teachers. Most co ...

s, providing religious services and basic education

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education als ...

. Principally, the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

was preferred and was a part of the national identity.

In times of peace, Cossacks were engaged in their occupations, living with their families, studying strategy, languages and educating recruits. As opposed to other armies, Cossacks were free to choose their preferred weapon. Wealthy Cossacks preferred to wear heavy armour

Armour (Commonwealth English) or armor (American English; see American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, e ...

, while infantrymen preferred to wear simple clothes, although they also occasionally wore mail

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letter (message), letters, and parcel (package), parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid ...

.

At that time, the Cossacks were one of the finest military organizations in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, and were employed by Russian, Polish, and French empires.

Kurins of the Zaporozhian Host

* Levushkovsky * Plastunovsky * Dyadkovsky * Bryukhovetsky * Vedmedovsky * Platmyrovsky * Pashkovsky * Kushchevsky * Kyslyakovsky * Ivanovsky * Konelovsky * Serhiyevsky * Donsky * Krylovsky *Kaniv

Kaniv (, ) is a city in Cherkasy Raion, Cherkasy Oblast, central Ukraine. The city rests on the Dnieper River, and is one of the main inland river ports on the Dnieper. It is an urban hromada of Ukraine. Population:

Kaniv is a historical tow ...

sky

* Baturyn

Baturyn (, ) is a historic city in Chernihiv Oblast (province) of northern Ukraine. It is located in Nizhyn Raion (district) on the banks of the Seym River. It hosts the administration of Baturyn urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. P ...

sky

* Popovychevsky

* Vasyurynsky

* Nezamaikovsky

* Irkliyevsky

* Shcherbynovsky

* Tytarovsky

* Shkurynsky

* Kurenevsky

* Rohovsky

* Korsunsky

* Kalnybolotsky

* Humansky

* Derevyantsovsky

* Stebliyivsky-Higher

* Stebliyivsky-Lower

* Zherelovsky

* Pereyaslavsky

* Poltavsky

* Myshastovsky

* Minsk

Minsk (, ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach (Berezina), Svislach and the now subterranean Nyamiha, Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus and is the administra ...

y

* Tymoshevsky

* Velychkovsky

Beside the above-mentioned kurins there also was a great number of other kurins outside the Host.

Cossack Regalia (''Kleinody'')

The most important items of the host were the Cossack ''Kleinody'' (always in plural; related toImperial Regalia

The Imperial Regalia, also called Imperial Insignia (in German ''Reichskleinodien'', ''Reichsinsignien'' or ''Reichsschatz''), are regalia of the Holy Roman Emperor. The most important parts are the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire, C ...

) that consisted of valuable military distinctions, regalia, and attributes of the Ukrainian Cossacks and were used until the 19th century. Kleinody were awarded to Zaporozhian Cossacks by the Polish king Stephen Báthory

Stephen Báthory (; ; ; 27 September 1533 – 12 December 1586) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (1576–1586) as well as Prince of Transylvania, earlier Voivode of Transylvania (1571–1576).

The son of Stephen VIII Báthory ...

on 20 August 1576 to Bohdan Ruzhynsky, among which were khoruhva, bunchuk

A ''tug'' ( , , or ) or sulde (, ) is a pole with circularly arranged horsetail hairs of varying colors arranged at the top. It was historically flown by Turkic tribal confederations such as the Duolu (Tuğluğ Confederation) and also duri ...

, bulawa "mace" and a seal with a coat of arms on which was depicted a cossack with a ''samopal'' "rifle". The kleinody were assigned to hetman's assistants for safekeeping, thus there have appeared such ranks as ''chorąży

A standard-bearer ( Polish: ''Chorąży'' ; Russian and ; , chorunžis; ) is a military rank in Poland, Ukraine and some neighboring countries. A ''chorąży'' was once a knight who bore an ensign, the emblem of an armed troops, a voivodship, a l ...

'' ("flag-bearer"), ''bunchuzhny'' ("staff-keeper"), etc. Later part of Cossack kleinody became pernach

A pernach (, or , ) is a type of flanged mace originating in the 12th century in the region of Kievan Rus' and later widely used throughout Europe. The name comes from the Slavic word ''перо'' (''pero'') meaning feather, referring to a typ ...

es, timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion instrument, percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a Membranophone, membrane called a drumhead, ...

(''lytavry''), kurin banners (badges), batons, and others.

The highest symbol of power was the ''bulawa'' or mace carried by hetmans and kish-otamans. For example, Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Zynoviy Bohdan Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky of the Abdank coat of arms (Ruthenian language, Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern , Polish language, Polish: ; 15956 August 1657) was a Ruthenian nobility, Ruthenian noble ...

already from 1648 carried a silver gold-covered bulawa decorated with pearls and other valuable gem stones. The cossack colonels had pernachs (''shestoper''s) - smaller ribbed bulawas which were carried behind a belt.

kaftan

A kaftan or caftan (; , ; , ; ) is a variant of the robe or tunic. Originating in Asia, it has been worn by a number of cultures around the world for thousands of years. In Russian usage, ''kaftan'' instead refers to a style of men's long suit ...

with buttons on a chest, with a sabre

A sabre or saber ( ) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the Early Modern warfare, early modern and Napoleonic period, Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such a ...

(''shablya''), powder flask

A powder flask is a small container for gunpowder, which was an essential part of shooting equipment with muzzle-loading guns, before pre-made paper cartridges became standard in the 19th century. They range from very elaborately decorated works o ...

on a side, and a self-made rifle (''samopal'') on the left shoulder. Around the seal was an inscription «Печать славного Війська Запорізького Низового» ("Seal of the glorious Zaporozhian Host"). Palanka's and kurin's seals were either round or rectangular with images of lions, deers, horses, moon, stars, crowns, lances, sabers, and bows.

Khoruhva was mostly of a crimson color embroidered with coats of arms, saints, crosses, and others. It was always carried in front of the army next to the hetman or otaman. A badge (''znachok'') was a name for a kurin's or company's (sotnia

A sotnia ( Ukrainian and , ) was a military unit and administrative division in some Slavic countries.

Sotnia, deriving back to 1248, has been used in a variety of contexts in both Ukraine and Russia to this day. It is a helpful word to create ...

) banners. There was a tradition when the newly elected colonel was required at his own expense prepare palanka's banner. One of the banners was preserved until 1845 in Kuban

Kuban ( Russian and Ukrainian: Кубань; ) is a historical and geographical region in the North Caucasus region of southern Russia surrounding the Kuban River, on the Black Sea between the Don Steppe, the Volga Delta and separated fr ...

and was made out of tissue in two colors: yellow and blue. Kettledrums (lytavry) were large copper boilers that were fitted with a leather which served for transmission of various signals (calling cossacks to a council, raising an alarm etc.).

Each item of kleinody was granted to a clearly assigned member of cossack ''starshina'' (officership). For example, in the Zaporozhian Host, the bulawa was given to the otaman; the khoruhva - to the whole host although carried by a khorunzhy; the bunchuk also was given to otaman, but carried by a bunchuzhny or bunchuk comrade; the seal was preserved by a military judge, while the seals of the kurin - to the kurin otaman, and the seals of the palanka - to the colonel of a certain palanka; the kettledrums were in possession of a dovbysh (drummer); the staffs - to a military osavul

Yesaul, osaul or osavul (, ) (from Turkic yasaul - ''chief''), is a post and a rank in the Russian and Ukrainian Cossack units.

The first records of the rank imply that it was introduced by Stefan Batory, King of Poland in 1576.

Cossacks in Ru ...

; the badges were given to all the 38 kurins in possession to the assigned badge comrades. All kleinody items (except for the kettledrum sticks) were stored in the Sich's Pokrova church treasury

A church treasury or church treasure is the collection of historical art treasures belonging to a church, usually a cathedral or monastery (monastery treasure). Such "treasure" is usually held and displayed in the church's treasury or in a dioces ...

and were taken out only on a special order of kish otaman. The kettledrum sticks were kept in the kurin with the assigned dovbysh. Sometimes, part of kleidony was considered a great silver inkwell

An inkwell is a small jar or container, often made of glass, porcelain, silver, brass, or pewter, used for holding ink in a place convenient for the person who is writing. The artist or writer dips the brush, quill, or dip pen into the inkwell ...

(''kalamar''), an attribute of a military scribe (''pysar'') of the Zaporozhian Host. Similar kleinods had the officership of the Cossack Hetmanate

The Cossack Hetmanate (; Cossack Hetmanate#Name, see other names), officially the Zaporozhian Host (; ), was a Ukrainian Cossacks, Cossack state. Its territory was located mostly in central Ukraine, as well as in parts of Belarus and southwest ...

, cossacks of Kuban, Danube, and other cossack societies.

Upon the destruction of the Sich and liquidation of Ukrainian Cossacks the kleinody were gathered and given away for storage in Hermitage and Transfiguration Cathedral Transfiguration Cathedral or Cathedral of the Transfiguration may refer to:

Canada

* Cathedral of the Transfiguration (Markham), Markham, Ontario, Canada

Lithuania

* Transfiguration Cathedral, Kaišiadorys

Romania

* Transfiguration Cathedral, Cl ...

in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

, Kremlin Armoury

The Kremlin ArmouryOfficially called the "Armoury Chamber" but also known as the cannon yard, the "Armoury Palace", the "Moscow Armoury", the "Armoury Museum", and the "Moscow Armoury Museum" but different from the Kremlin Arsenal. () is one of ...

in Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

as well as other places of storage. By the end of 19th century the Hermitage stored 17 kurin banners and one khoruhva, the Transfiguration Cathedral contained 20 kurin banners, three bunchuks, one silver bulawa, and one silver gold-covered baton. Today the fate of those national treasures of Ukrainian people is unknown. After the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

in 1917 the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was a provisional government of the Russian Empire and Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately after the abdication of Nicholas II on 2 March, O.S. New_Style.html" ;"title="5 ...

adopted the decisions of returning them to Ukraine, however, due to the events of the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

of the same year the decision was not executed. With the proclamation of independence, the Ukrainian government has raised the issue of returning the national cultural valuables before the leadership of Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

; no specific agreements have ever been reached, however.

Alliance with Russia

After the

After the Treaty of Pereyaslav

The Pereiaslav Agreement or Pereyaslav AgreementPereyaslav Agreement

in 1654, the Zaporozhian Host became a suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

under the protection of the tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

of Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, although for a considerable period of time it enjoyed nearly complete autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

. After the death of Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Zynoviy Bohdan Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky of the Abdank coat of arms (Ruthenian language, Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern , Polish language, Polish: ; 15956 August 1657) was a Ruthenian nobility, Ruthenian noble ...

in 1657, his successor Ivan Vyhovsky

Ivan Vyhovsky (; ; date of birth unknown, died 1664), a Ukrainian military and political figure and statesman, served as hetman of the Zaporizhian Host and of the Cossack Hetmanate for three years (1657–1659) during the Russo-Polish War (1654 ...

initiated a turn towards Poland, alarmed by the growing Russian interference in the affairs of the Hetmanate. An attempt was made to return to the three-constituent Commonwealth of nations with the Zaporozhian cossacks joining the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by signing the Treaty of Hadiach

The Treaty of Hadiach (; ) was a treaty signed on 16 September 1658 in Hadiach (present-day Ukraine) between representatives of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth ( representing Poland and representing Lithuania) and Zaporozhian Cossacks (repr ...

(1658). The treaty was ratified by the Sejm

The Sejm (), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (), is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of the Third Polish Republic since the Polish People' ...

but was rejected at the Hermanivka Rada by the Cossack rank and file, who would not accept a union with Catholic Poland, which they perceived as an oppressor of Orthodox Christianity. The angered cossacks executed ''Polkovnik

(; ) is a military rank used mostly in Slavic-speaking countries which corresponds to a colonel in English-speaking states, ''coronel'' in Spanish and Portuguese-speaking states and ''oberst'' in several German-speaking and Scandinavian countr ...

s'' Prokip Vereshchaka and Stepan Sulyma, Vyhovsky's associates at the Sejm, and Vyhovsky himself narrowly escaped death.

The Zaporozhians maintained a largely separate government from the Hetmanate. The Zaporozhians elected their own leaders, known as Kish otaman

Kish may refer to:

Businesses and organisations

* KISH, a radio station in Guam

* Kish Air, an Iranian airline

* Korean International School in Hanoi, Vietnam

People

* Kish (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Kish, a former ...

, for one-year terms. In this period, friction between the cossacks of the Hetmanate and the Zaporozhians escalated.

The Cossacks had fought in the past for independence from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and they were later involved in several uprisings against the tsar, in fear of losing their privileges and autonomy. In 1709, for example, the Zaporozhian Host led by Kost Hordiienko joined Hetman Ivan Mazepa

Ivan Stepanovych Mazepa (; ; ) was the Hetman of the Zaporozhian Host and the Left-bank Ukraine in 1687–1708. The historical events of Mazepa's life have inspired Cultural legacy of Mazeppa, many literary, artistic and musical works. He was ...

against Russia. Mazepa was previously a trusted adviser and close friend to Tsar Peter the Great

Peter I (, ;

– ), better known as Peter the Great, was the Sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia, Tsar of all Russia from 1682 and the first Emperor of Russia, Emperor of all Russia from 1721 until his death in 1725. He reigned j ...

but allied himself with Charles XII of Sweden

Charles XII, sometimes Carl XII () or Carolus Rex (17 June 1682 – 30 November 1718 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.), was King of Sweden from 1697 to 1718. He belonged to the House of Palatinate-Zweibrücken, a branch line of the House of ...

against Peter I. After the defeat at the Battle of Poltava

The Battle of Poltava took place 8 July 1709, was the decisive and largest battle of the Great Northern War. The Russian army under the command of Tsar Peter I defeated the Swedish army commanded by Carl Gustaf Rehnskiöld. The battle would l ...

Peter ordered a retaliatory destruction of the Sich.

With the death of Mazepa in Bessarabia

Bessarabia () is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Bessarabia lies within modern-day Moldova, with the Budjak region covering the southern coa ...

in 1709, his council elected his former general chancellor, Pylyp Orlyk

Pylyp Stepanovych Orlyk (; ; – May 26, 1742) was a Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack statesman, diplomat and member of Cossack starshyna who served as the Hetman of Zaporizhian Cossacks, hetman in exile from 1710 to 1742. He was a cl ...

, as his successor. Orlyk issued the project of the Constitution, where he promised to limit the authority of the Hetman, preserve the privileged position of the Zaporozhians, take measures towards achieving social equality among them, and steps towards the separation of the Zaporizhian Host from the Russian State—should he manage to obtain power in the Cossack Hetmanate. With the support of Charles XII, Orlyk made an alliance with the Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

and Ottomans against Russia, but following the early successes of their 1711 attack on Russia, their campaign was defeated, and Orlyk returned into exile. The Zaporozhians built a new Sich under Ottoman protection, the Oleshky Sich on the lower Dnieper.

Although some of the Zaporozhian cossacks returned to Moscow's protection, their popular leader Kost Hordiienko was resolute in his anti-Russian attitude and no rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word ''rapprocher'' ("to bring together"), is a re-establishment of cordial relations between two countries. This may be done due to a mutual antagonist, as the German Empire ...

was possible until his death in 1733.

Within the Russian Empire

Over the years the friction between the Cossacks and the Russian tsarist government lessened, and privileges were traded for a reduction in Cossack autonomy. The Ukrainian Cossacks who did not side with Mazepa elected as Hetman

Over the years the friction between the Cossacks and the Russian tsarist government lessened, and privileges were traded for a reduction in Cossack autonomy. The Ukrainian Cossacks who did not side with Mazepa elected as Hetman Ivan Skoropadsky

Ivan Skoropadsky (; ; 1646 – ) was a Cossack Hetman of the Zaporizhian Host from 1708 to 1722, and the successor to the Hetman Ivan Mazepa.

Biography

Born into a noble Cossack family in Humań, Podolia, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1 ...

, one of the "anti-Mazepist" polkovniks. While advocating for the preservation for the Hetmanate autonomy and privileges of the starshina, Skoropadsky was careful to avoid open confrontation and remained loyal to the union with Russia. To accommodate Russian military needs, Skoropadsky allowed for stationing of ten Russian regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, military service, service, or administrative corps, specialisation.

In Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of l ...

s in the territory of the Hetmanate. At the same time, Cossacks took part in construction, fortification and channel development projects in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

, as part of the effort by Peter the Great to establish the new Russian capital. Many did not return, and it is often stated that St. Peterburg "was built on bones".

In 1734, as Russia was preparing for a new war against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, an agreement was made between Russia and the Zaporozhian cossacks, the Treaty of Lubny. The Zaporozhian Cossacks regained all of their former lands, privileges, laws and customs in exchange for serving under the command of a Russian Army stationed in Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

. A new ''sich'' (''Nova Sich'') was built to replace the one that had been destroyed by Peter the Great. Concerned about the possibility of Russian interference in Zaporozhia's internal affairs, the Cossacks began to settle their lands with Ukrainian peasants fleeing serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

in Poland and Russia proper. By 1762, 33,700 Cossacks and over 150,000 peasants populated Zaporozhia.

By the late 18th century, much of the Cossack officer class in Ukraine was incorporated into the Russian nobility, but many of the rank and file Cossacks, including a substantial portion of the old Zaporozhians, were reduced to peasant status. They were able to maintain their freedom and continued to provide refuge for those fleeing serfdom in Russia and Poland, including followers of the Russian Cossack Yemelyan Pugachev

Yemelyan Ivanovich Pugachev (also spelled Pugachyov; ; ) was an ataman of the Yaik Cossacks and the leader of the Pugachev's Rebellion, a major popular uprising in the Russian Empire during the reign of Catherine the Great.

The son of a Do ...

, which aroused the anger of Russian Empress Catherine II

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter III ...

. As a result, by 1775 the number of runaway serfs from the Hetmanate and Polish-ruled Ukraine to Zaporizhiya rose to 100,000.

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (; ), formerly often written Kuchuk-Kainarji, was a peace treaty signed on , in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kaynardzha, Bulgaria and Cuiugiuc, Romania) between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, ending the R ...

(1774) annexed the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

into Russia, so the need for further southern frontier defence (which the Zaporozhians carried out) no longer existed. Colonisation of Novorossiya

Novorossiya rus, Новороссия, Novorossiya, p=nəvɐˈrosʲːɪjə, a=Ru-Новороссия.ogg; , ; ; ; "New Russia". is a historical name, used during the era of the Russian Empire for an administrative area that would later becom ...

began; one of the colonies, located just next to the lands of the Zaporozhian Sich, was New Serbia. This escalated conflicts over land ownership with the Cossacks, which often turned violent.

The end of the Zaporozhian Host (1775)

The decision to disband the Sich was adopted at the court council ofCatherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

on 7 May 1775. General Peter Tekeli

Peter Tekeli (; ;''Popović'' is often omitted. ; 1720–1792) was a Russian general-in-chief of Serb origin. He achieved the highest rank among the Serbs who served in the Imperial Russian Army.

Tekeli was born in a noble family of military tr ...

received orders to occupy and liquidate the main Zaporozhian fortress, the Sich. The plan was kept secret and regiments returning from the Russo-Turkish war, in which Cossacks also participated, were mobilized for the operation. They included 31 regiments (65,000 men in total). The attack took place on 15 May and continued until 8 June. The order was given by Grigory Potemkin

Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin-Tauricheski (A number of dates as late as 1742 have been found on record; the veracity of any one is unlikely to be proved. This is his "official" birth-date as given on his tombstone.) was a Russian mi ...

, who had formally become an honorary Zaporozhian Cossack under the name of Hrytsko Nechesa a few years prior. Potemkin was given a direct order from Empress Catherine II, which she explained in her Decree of 8 August 1775:

On 5 June 1775 General Tekeli's forces divided into five detachments and surrounded the Sich with artillery and infantry. The lack of southern borders and enemies in the past years had a profound effect on the combat-ability of the Cossacks, who realised the Russian infantry would destroy them after they were surrounded. To trick the Cossacks, a rumour was spread that the army was crossing Cossack lands en route to guard the borders. The surprise encirclement was a devastating blow to the morale of the Cossacks.

Petro Kalnyshevsky

Petro Ivanovych Kalnyshevsky (; 20 June 1690 – 31 October 1803) was a Ukrainian Cossack leader who served as the final Kish otaman of the Zaporozhian Sich, holding the office from 1765 to 1775. He had previously briefly served as kish otama ...

was given two hours to decide on the Empress's ultimatum

An ; ; : ultimata or ultimatums) is a demand whose fulfillment is requested in a specified period of time and which is backed up by a coercion, threat to be followed through in case of noncompliance (open loop). An ultimatum is generally the ...

. Under the guidance of a ''starshyna'' Lyakh, behind Kalnyshevky's back a conspiracy was formed with a group of 50 Cossacks to go fishing in the river Inhul

The Inhul () is a left tributary of the Southern Bug (Boh) and is the 14th longest river of Ukraine. It flows through the Kirovohrad and Mykolaiv regions.

It starts near the village of Rodnykivka, Oleksandriia Raion in Kirovohrad Oblast (Ce ...

next to the Southern Bug

The Southern Bug, also called Southern Buh (; ; ; or just ), and sometimes Boh River (; ),

in Ottoman provinces. The pretext was enough to allow the Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

to let the Cossacks out of the siege, who were joined by five thousand others. The fleeing Cossacks traveled to the Danube Delta

The Danube Delta (, ; , ) is the second largest river delta in Europe, after the Volga Delta, and is the best preserved on the continent. Occurring where the Danube, Danube River empties into the Black Sea, most of the Danube Delta lies in Romania ...

, where they formed the new Danubian Sich

The Danubian Sich () was an organization of the part of former Zaporozhian Cossacks who settled in the territory of the Ottoman Empire (the Danube Delta, hence the name) after their previous host was disbanded and the Zaporozhian Sich was des ...

, under the protectorate of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

When Tekeli became aware of the escape, there was little left to do for the remaining 12,000 Cossacks. The Sich was razed to the ground. The Cossacks were disarmed in a mostly bloodless operation, while their treasury and archives were confiscated. Kalnyshevsky was arrested and exiled to the Solovki, where he lived in confinement to 112 years of age. Most upper level Cossack Council members, such as Pavlo Holovaty

Pavlo Andriyovych Holovaty (; 1715–1795) was a Ukrainian military figure, a Kosh Otoman of the Zaporozhian Sich and last military judge of the Zaporozhian Cossack Host. He is often confused with his younger brother, the leader of the Zaporozahi ...

and Ivan Hloba, were repressed and exiled as well, although lower level commanders and rank and file Cossacks were allowed to join the Russian hussar

A hussar, ; ; ; ; . was a member of a class of light cavalry, originally from the Kingdom of Hungary during the 15th and 16th centuries. The title and distinctive dress of these horsemen were subsequently widely adopted by light cavalry ...

and dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat wi ...

regiments.

Aftermath

The destruction of the Sich created difficulties for the Russian Empire. Supporting the increase in the privileges gained by the higher ranking leadership put a strain in the budget, whilst the stricter regulations of the regular Russian Army prevented many other Cossacks from integrating. The existence of theDanubian Sich

The Danubian Sich () was an organization of the part of former Zaporozhian Cossacks who settled in the territory of the Ottoman Empire (the Danube Delta, hence the name) after their previous host was disbanded and the Zaporozhian Sich was des ...

, which would support the Ottoman Empire in the next war, was also troublesome for the Russians. In 1784 Potemkin formed the ''Host of the Loyal Zaporozhians'' (Войско верных Запорожцев) and settled them between the Southern Bug

The Southern Bug, also called Southern Buh (; ; ; or just ), and sometimes Boh River (; ),

and Dniester

The Dniester ( ) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and then through Moldova (from which it more or less separates the breakaway territory of Transnistria), finally discharging into the Black Sea on Uk ...

rivers. For their invaluable service during the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

(1787–1792), they were rewarded with the Kuban

Kuban ( Russian and Ukrainian: Кубань; ) is a historical and geographical region in the North Caucasus region of southern Russia surrounding the Kuban River, on the Black Sea between the Don Steppe, the Volga Delta and separated fr ...

land and migrated there in 1792.

In 1828, the Danubian Sich ceased to exist after it was pardoned by Emperor Nicholas I, and under amnesty its members settled on the shores of the Northern Azov

Azov (, ), previously known as Azak ( Turki/ Kypchak: ),

is a town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River just from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name from the town. The population is

History

Early settlements in the vici ...

between Berdyansk

Berdiansk or Berdyansk (, ; , ) is a port city in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, south-eastern Ukraine. It is on the northern coast of the Sea of Azov, which is connected to the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Berdiansk Raion. The ...

and Mariupol

Mariupol is a city in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine. It is situated on the northern coast (Pryazovia) of the Sea of Azov, at the mouth of the Kalmius, Kalmius River. Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it was the tenth-largest city in the coun ...

, forming the Azov Cossack Host

Azov Cossack Host (; ) was a Cossack host that existed on the northern shore of the Sea of Azov, between 1832 and 1862.

The host was made up of several Cossack groups who were re-settled there. The most numerous were the former Danubian Sich Cos ...

. Finally in 1862 they too migrated to the Kuban and merged with the Kuban Cossacks

Kuban Cossacks (; ), or Kubanians (, ''kubantsy''; , ''kubantsi''), are Cossacks who live in the Kuban region of Russia. Most of the Kuban Cossacks are descendants of different major groups of Cossacks who were re-settled to the western Norther ...

. The Kuban Cossacks served Russia's interests right up to the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, and their descendants are now undergoing active regeneration both culturally and militarily. The 30,000 descendants of those Cossacks who refused to return to Russia in 1828 still live in the Danube delta region of Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

and Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, where they pursue the traditional Cossack lifestyle of hunting and fishing and are known as ''Rusnaks''.

Legacy

Although in 1775 the Zaporozhian Host formally ceased to exist, it left a profound cultural, political and military legacy onUkraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

and other states that came in contact with it. The shifting alliances of the Cossacks have generated controversy, especially during the 20th century. For Russians, the Treaty of Pereyaslav

The Pereiaslav Agreement or Pereyaslav AgreementPereyaslav Agreement

gave the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia, also known as the Tsardom of Moscow, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of tsar by Ivan the Terrible, Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter the Great in 1721.

...

and later Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

the impulse to take over the Ruthenia

''Ruthenia'' is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin, as one of several terms for Rus'. Originally, the term ''Rus' land'' referred to a triangular area, which mainly corresponds to the tribe of Polans in Dnieper Ukraine. ''Ruthenia' ...

n lands, claim rights as the sole successor of the Kievan Rus', and for the Russian Tsar to be declared the protector of all Russias, culminating in the Pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism, a movement that took shape in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with promoting integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had ruled the South ...

movement of the 19th century.

Today, most of the Kuban Cossacks, modern descendants of the Zaporozhians, remain loyal towards Russia. Many fought in the local conflicts following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and today, just like before the revolution when they made up the private guard of the Emperor, the majority of the Kremlin Presidential Regiment is made up of Kuban Cossacks.

For the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the

Today, most of the Kuban Cossacks, modern descendants of the Zaporozhians, remain loyal towards Russia. Many fought in the local conflicts following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and today, just like before the revolution when they made up the private guard of the Emperor, the majority of the Kremlin Presidential Regiment is made up of Kuban Cossacks.

For the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

and the fall of the Zaporozhian Cossacks effectively marked the beginning of its end with the Deluge

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is a Hebrew flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre-Genesis creation narrative, creation state of watery Chaos (cosmogony), chaos and remake it ...

, which led to the gradual demise of the Commonwealth ending with the Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partition (politics), partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place between 1772 and 1795, toward the end of the 18th century. They ended the existence of the state, resulting in the eli ...

in the late 18th century. A similar fate awaited both the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire; having endured numerous raids and attacks from them both, the Zaporozhian Cossacks aided the Russian Army in ending Turkey's ambitions of expanding into northern and Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

, and like Poland, after the loss of Crimea, the Ottoman Empire began to decline.

The historical legacy of the Zaporozhian Cossacks shaped and influenced the idea of Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism (, ) is the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The origins of modern Ukrainian nationalism emerge during the Khmelnytsky Uprising, Cossack upri ...

in the latter half of the 19th century. Ukrainian historians, such as Adrian Kashchenko

Adrian Kashchenko () (19 September 1858 – 16 March 1921) was a well-known Ukrainians, Ukrainian writer, historian of Zaporozhian Cossacks.

Biography

Adrian Kashchenko was born in the family of small landowner claiming its roots to the Zaporozhi ...

(1858–1921), Olena Apanovich and others suggest that the final abolishment of the Zaporozhian Sich

The Zaporozhian Sich (, , ; also ) was a semi-autonomous polity and proto-state of Zaporozhian Cossacks that existed between the 16th to 18th centuries, for the latter part of that period as an autonomous stratocratic state within the Cossa ...

in 1775 was the demise of a historic Ukrainian stronghold. After the Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

, corps of Free Cossacks

Free Cossacks () were Ukrainian Cossacks that were organized as volunteer militia units in the spring of 1917 in the Ukrainian People's Republic. The Free Cossacks are seen as precursors of the modern Ukrainian national law enforcement organiz ...

were organized in Ukraine to defend the newly proclaimed Ukrainian People's Republic