Deinonychus (Raptor Prey Restraint) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Deinonychus'' ( ; ) is a

In 1974, Ostrom published another monograph on the shoulder of ''Deinonychus'' in which he realized that the pubis that he had described was actually a coracoid—a shoulder element. In that same year, another specimen of ''Deinonychus'', MCZ 4371, was discovered and excavated in Montana by Steven Orzack during a Harvard University expedition headed by Farish Jenkins. This discovery added several new elements: well preserved femora, pubes, a sacrum, and better ilia, as well as elements of the pes and metatarsus. Ostrom described this specimen and revised his skeletal restoration of ''Deinonychus''. This time it showed the very long pubis, and Ostrom began to suspect that they may have even been a little retroverted like those of birds.

In 1974, Ostrom published another monograph on the shoulder of ''Deinonychus'' in which he realized that the pubis that he had described was actually a coracoid—a shoulder element. In that same year, another specimen of ''Deinonychus'', MCZ 4371, was discovered and excavated in Montana by Steven Orzack during a Harvard University expedition headed by Farish Jenkins. This discovery added several new elements: well preserved femora, pubes, a sacrum, and better ilia, as well as elements of the pes and metatarsus. Ostrom described this specimen and revised his skeletal restoration of ''Deinonychus''. This time it showed the very long pubis, and Ostrom began to suspect that they may have even been a little retroverted like those of birds.

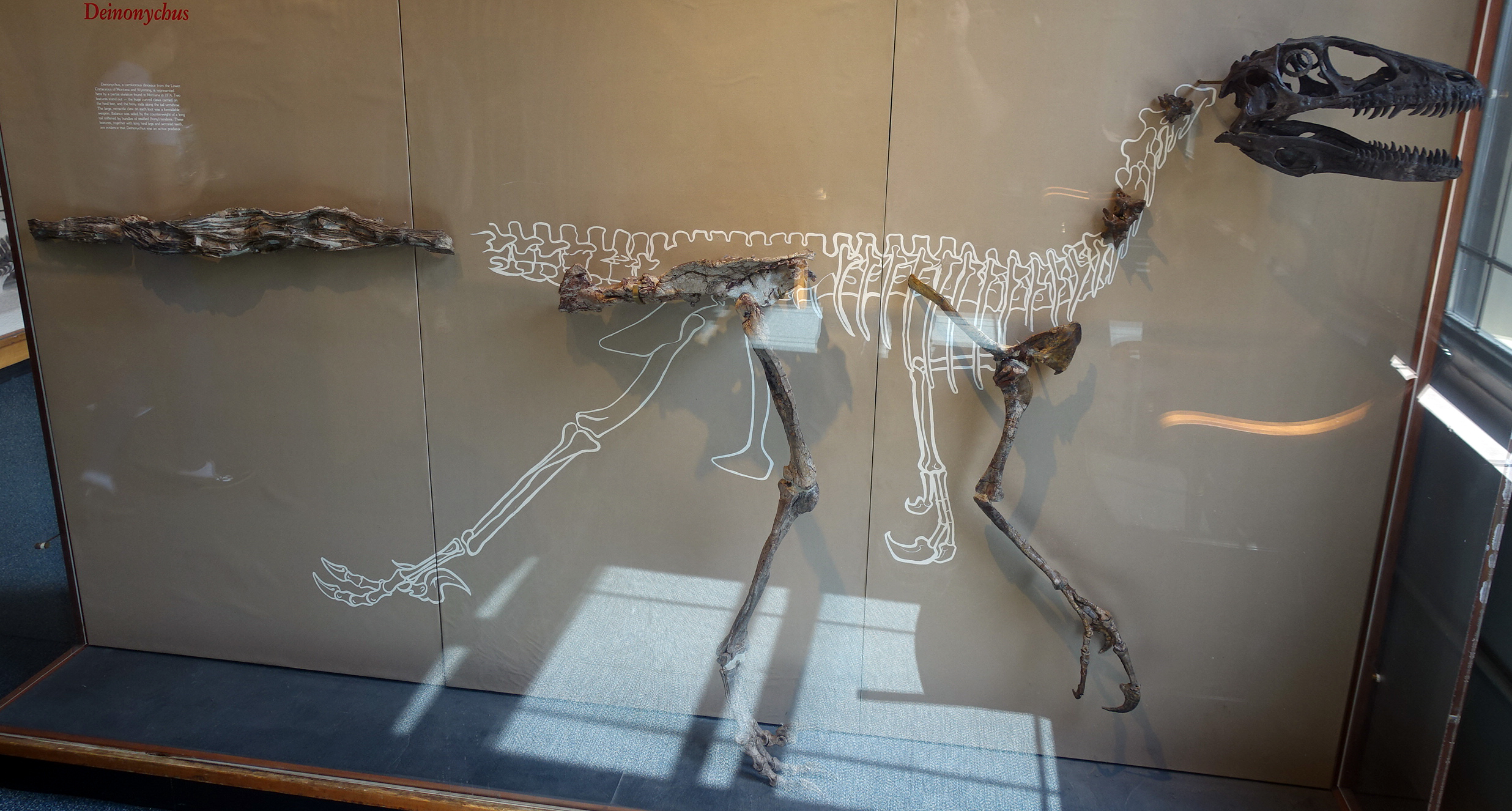

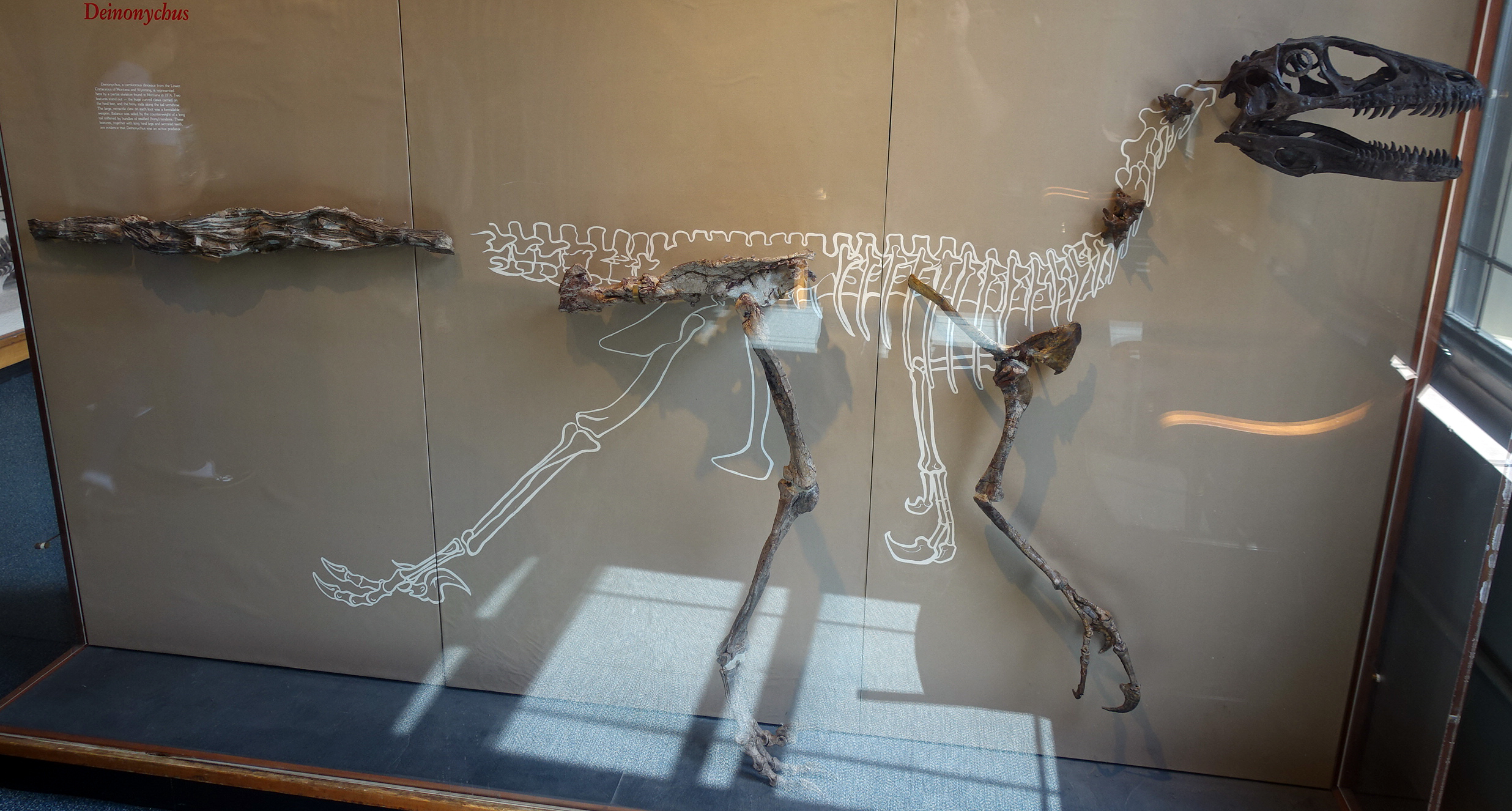

A skeleton of ''Deinonychus'', including bones from the original (and most complete) AMNH 3015 specimen, can be seen on display at the American Museum of Natural History, with another specimen (MCZ 4371) on display at the

A skeleton of ''Deinonychus'', including bones from the original (and most complete) AMNH 3015 specimen, can be seen on display at the American Museum of Natural History, with another specimen (MCZ 4371) on display at the

Based on the few fully mature specimens,

Based on the few fully mature specimens,  ''Deinonychus'' possessed large "hands" (

''Deinonychus'' possessed large "hands" (

abstract

) Two Late Cretaceous genera, '' A 2021 study of the dromaeosaurid '' Kansaignathus'' recovered ''Deinonychus'' as a velociraptorine rather than a dromaeosaurine, with ''Kansaignathus'' being an intermediate basal form more advanced than ''Deinonychus'' but more primitive than ''Velociraptor''. The cladogram below showcases these newly described relationships:

A study in 2022, however, reclassified ''Deinonychus'' as a basal member of Dromaeosaurinae again.

A 2021 study of the dromaeosaurid '' Kansaignathus'' recovered ''Deinonychus'' as a velociraptorine rather than a dromaeosaurine, with ''Kansaignathus'' being an intermediate basal form more advanced than ''Deinonychus'' but more primitive than ''Velociraptor''. The cladogram below showcases these newly described relationships:

A study in 2022, however, reclassified ''Deinonychus'' as a basal member of Dromaeosaurinae again.

Bite force estimates for ''Deinonychus'' were first produced in 2005, based on reconstructed jaw musculature. This study concluded that ''Deinonychus'' likely had a maximum bite force only 15% that of the modern American alligator. A 2010 study by Paul Gignac and colleagues attempted to estimate the bite force based directly on newly discovered ''Deinonychus'' tooth puncture marks in the bones of a ''Tenontosaurus''. These puncture marks came from a large individual, and provided the first evidence that large ''Deinonychus'' could bite through bone. Using the tooth marks, Gignac's team were able to determine that the bite force of ''Deinonychus'' was significantly higher than earlier studies had estimated by biomechanical studies alone. They found the bite force of ''Deinonychus'' to be between 4,100 and 8,200

Bite force estimates for ''Deinonychus'' were first produced in 2005, based on reconstructed jaw musculature. This study concluded that ''Deinonychus'' likely had a maximum bite force only 15% that of the modern American alligator. A 2010 study by Paul Gignac and colleagues attempted to estimate the bite force based directly on newly discovered ''Deinonychus'' tooth puncture marks in the bones of a ''Tenontosaurus''. These puncture marks came from a large individual, and provided the first evidence that large ''Deinonychus'' could bite through bone. Using the tooth marks, Gignac's team were able to determine that the bite force of ''Deinonychus'' was significantly higher than earlier studies had estimated by biomechanical studies alone. They found the bite force of ''Deinonychus'' to be between 4,100 and 8,200

Despite being the most distinctive feature of ''Deinonychus'', the shape and curvature of the

Despite being the most distinctive feature of ''Deinonychus'', the shape and curvature of the  Biomechanical studies by Ken Carpenter in 2002 confirmed that the most likely function of the forelimbs in predation was grasping, as their great lengths would have permitted longer reach than for most other theropods. The rather large and elongated

Biomechanical studies by Ken Carpenter in 2002 confirmed that the most likely function of the forelimbs in predation was grasping, as their great lengths would have permitted longer reach than for most other theropods. The rather large and elongated  Parsons and Parsons have shown that juvenile and sub-adult specimens of ''Deinonychus'' display some morphological differences from the adults. For instance, the arms of the younger specimens were proportionally longer than those of the adults, a possible indication of difference in behavior between young and adults. Another example of this could be the function of the pedal claws. Parsons and Parsons have suggested that the claw curvature (which Ostrom

Parsons and Parsons have shown that juvenile and sub-adult specimens of ''Deinonychus'' display some morphological differences from the adults. For instance, the arms of the younger specimens were proportionally longer than those of the adults, a possible indication of difference in behavior between young and adults. Another example of this could be the function of the pedal claws. Parsons and Parsons have suggested that the claw curvature (which Ostrom

In his 1981 study of Canadian dinosaur footprints, Richard Kool produced rough walking speed estimates based on several trackways made by different species in the

In his 1981 study of Canadian dinosaur footprints, Richard Kool produced rough walking speed estimates based on several trackways made by different species in the

The identification, in 2000, of a probable ''Deinonychus'' egg associated with one of the original specimens allowed comparison with other theropod dinosaurs in terms of egg structure, nesting, and reproduction. In their 2006 examination of the specimen, Grellet-Tinner and Makovicky examined the possibility that the dromaeosaurid had been feeding on the egg, or that the egg fragments had been associated with the ''Deinonychus'' skeleton by coincidence. They dismissed the idea that the egg had been a meal for the theropod, noting that the fragments were sandwiched between the belly ribs and forelimb bones, making it impossible that they represented contents of the animal's stomach. In addition, the manner in which the egg had been crushed and fragmented indicated that it had been intact at the time of burial, and was broken by the fossilization process. The idea that the egg was randomly associated with the dinosaur was also found to be unlikely; the bones surrounding the egg had not been scattered or disarticulated, but remained fairly intact relative to their positions in life, indicating that the area around and including the egg was not disturbed during preservation. The fact that these bones were belly ribs (

The identification, in 2000, of a probable ''Deinonychus'' egg associated with one of the original specimens allowed comparison with other theropod dinosaurs in terms of egg structure, nesting, and reproduction. In their 2006 examination of the specimen, Grellet-Tinner and Makovicky examined the possibility that the dromaeosaurid had been feeding on the egg, or that the egg fragments had been associated with the ''Deinonychus'' skeleton by coincidence. They dismissed the idea that the egg had been a meal for the theropod, noting that the fragments were sandwiched between the belly ribs and forelimb bones, making it impossible that they represented contents of the animal's stomach. In addition, the manner in which the egg had been crushed and fragmented indicated that it had been intact at the time of burial, and was broken by the fossilization process. The idea that the egg was randomly associated with the dinosaur was also found to be unlikely; the bones surrounding the egg had not been scattered or disarticulated, but remained fairly intact relative to their positions in life, indicating that the area around and including the egg was not disturbed during preservation. The fact that these bones were belly ribs (

abstract

) The second such quarry is from the Antlers Formation of Oklahoma. The site contains six partial skeletons of ''Tenontosaurus'' of various sizes, along with one partial skeleton and many teeth of ''Deinonychus''. One tenontosaur humerus even bears what might be ''Deinonychus'' tooth marks. Brinkman ''et al.'' (1998) point out that ''Deinonychus'' had an adult mass of , whereas adult tenontosaurs were 1–4 metric tons. A solitary ''Deinonychus'' could not kill an adult tenontosaur, suggesting that pack hunting is possible. A 2007 study by Roach and Brinkman has called into question the gregariousness and cooperative pack hunting behavior of ''Deinonychus'', based on what is known of modern carnivore hunting and the

Geological evidence suggests that ''Deinonychus'' inhabited a

Geological evidence suggests that ''Deinonychus'' inhabited a

''Deinonychus'' were featured prominently in Harry Adam Knight's novel ''

''Deinonychus'' were featured prominently in Harry Adam Knight's novel ''

Yale's legacy in ''Jurassic World''

" ''Yale News'', June 18, 2015. The ''Jurassic Park'' filmmakers followed suit, designing the film's models based almost entirely on ''Deinonychus'' instead of the actual ''Velociraptor'', and they reportedly requested all of Ostrom's published papers on ''Deinonychus'' during production. As a result, they portrayed the film's dinosaurs with the size, proportions, and snout shape of ''Deinonychus''. The ''

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of dromaeosaurid

Dromaeosauridae () is a family (biology), family of feathered coelurosaurian Theropoda, theropod dinosaurs. They were generally small to medium-sized feathered carnivores that flourished in the Cretaceous period (geology), Period. The name Drom ...

theropod

Theropoda (; from ancient Greek , (''therion'') "wild beast"; , (''pous, podos'') "foot"">wiktionary:ποδός"> (''pous, podos'') "foot" is one of the three major groups (clades) of dinosaurs, alongside Ornithischia and Sauropodom ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

with one described species, ''Deinonychus antirrhopus''. This species, which could grow up to long, lived during the early Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

Period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Period (punctuation)

* Era, a length or span of time

*Menstruation, commonly referred to as a "period"

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (o ...

, about 115–108 million year

A year is a unit of time based on how long it takes the Earth to orbit the Sun. In scientific use, the tropical year (approximately 365 Synodic day, solar days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, 45 seconds) and the sidereal year (about 20 minutes longer) ...

s ago (from the mid-Aptian

The Aptian is an age (geology), age in the geologic timescale or a stage (stratigraphy), stage in the stratigraphic column. It is a subdivision of the Early Cretaceous, Early or Lower Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch or series (stratigraphy), S ...

to early Albian

The Albian is both an age (geology), age of the geologic timescale and a stage (stratigraphy), stage in the stratigraphic column. It is the youngest or uppermost subdivision of the Early Cretaceous, Early/Lower Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch/s ...

stages

Stage, stages, or staging may refer to:

Arts and media Acting

* Stage (theatre), a space for the performance of theatrical productions

* Theatre, a branch of the performing arts, often referred to as "the stage"

* ''The Stage'', a weekly Brit ...

). Fossils have been recovered from the U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

s of Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

, Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

, Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

, and Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

, in rocks of the Cloverly Formation

The Cloverly Formation is a formation (geology), geological formation of Early Cretaceous, Early and Late Cretaceous age (Valanginian to Cenomanian stage) that is present in parts of Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and Utah in the western United State ...

and Antlers Formation

The Antlers Formation is a stratum which ranges from Arkansas through southern Oklahoma into northeastern Texas. The stratum is thick consisting of silty to sandy mudstone and fine to coarse grained sandstone that is poorly to moderately sorted. ...

, though teeth that may belong to ''Deinonychus'' have been found much farther east in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

.

Paleontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

John Ostrom

John Harold Ostrom (February 18, 1928 – July 16, 2005) was an American paleontologist who revolutionized the modern understanding of dinosaurs. Ostrom's work inspired what his pupil Robert T. Bakker has termed a " dinosaur renaissance".

Begin ...

's study of ''Deinonychus'' in the late 1960s revolutionized the way scientists thought about dinosaurs, leading to the " dinosaur renaissance" and igniting the debate on whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded

Warm-blooded is a term referring to animal species whose bodies maintain a temperature higher than that of their environment. In particular, homeothermic species (including birds and mammals) maintain a stable body temperature by regulating ...

or cold-blooded. Before this, the popular conception of dinosaurs had been one of plodding, reptilian giants. Ostrom noted the small body, sleek, horizontal posture, ratite

Ratites () are a polyphyletic group consisting of all birds within the infraclass Palaeognathae that lack keels and cannot fly. They are mostly large, long-necked, and long-legged, the exception being the kiwi, which is also the only nocturnal ...

-like spine, and especially the enlarged raptorial claws on the feet, which suggested an active, agile predator.

"Terrible claw" refers to the unusually large, sickle-shaped talon on the second toe of each hind foot. The fossil YPM 5205 preserves a large, strongly curved ungual

An ungual (from Latin ''unguis'', i.e. ''nail'') is a highly modified distal toe bone which ends in a hoof, claw, or nail. Elephants and ungulates have ungual phalanges, as did the sauropod

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; ...

. In life, archosaurs

Archosauria () or archosaurs () is a clade of diapsid sauropsid tetrapods, with birds and crocodilians being the only extant taxon, extant representatives. Although broadly classified as reptiles, which traditionally exclude birds, the cladistics ...

have a horny sheath over this bone, which extends the length. Ostrom looked at crocodile and bird claws and reconstructed the claw for YPM 5205 as over long. The species name ''antirrhopus'' means "counter balance", which refers to Ostrom's idea about the function of the tail. As in other dromaeosaurids, the tail vertebrae have a series of ossified tendons and super-elongated bone processes. These features seemed to make the tail into a stiff counterbalance, but a fossil of the very closely related ''Velociraptor mongoliensis

''Velociraptor'' (; ) is a genus of small dromaeosaurid dinosaurs that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous epoch, about 75 million to 71 million years ago. Two species are currently recognized, although others have been assigned in the ...

'' (''IGM'' 100/986) has an articulated tail skeleton that is curved laterally in a long S-shape. This suggests that, in life, the tail could bend to the sides with a high degree of flexibility. In both the Cloverly and Antlers formations, ''Deinonychus'' remains have been found closely associated with those of the ornithopod ''Tenontosaurus

''Tenontosaurus'' ( ; ) is a genus of iguanodontian ornithopod dinosaur. It had an unusually long, broad tail, which like its back was stiffened with a network of bony tendons.

The genus is known from the late Aptian to Albian ages of the Early ...

''. Teeth discovered associated with ''Tenontosaurus'' specimens imply they were hunted, or at least scavenged upon, by ''Deinonychus''. This has led to a debate on whether or not ''Deinonychus'' was gregarious or solitary, with recent evidence suggesting it may have been gregarious, despite not living in mammal-like packs.

Discovery and naming

Fossilized remains of ''Deinonychus'' have been recovered from theCloverly Formation

The Cloverly Formation is a formation (geology), geological formation of Early Cretaceous, Early and Late Cretaceous age (Valanginian to Cenomanian stage) that is present in parts of Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and Utah in the western United State ...

of Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

and Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

and in the roughly contemporary Antlers Formation

The Antlers Formation is a stratum which ranges from Arkansas through southern Oklahoma into northeastern Texas. The stratum is thick consisting of silty to sandy mudstone and fine to coarse grained sandstone that is poorly to moderately sorted. ...

of Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

, in North America. The Cloverly formation has been dated to the late Aptian

The Aptian is an age (geology), age in the geologic timescale or a stage (stratigraphy), stage in the stratigraphic column. It is a subdivision of the Early Cretaceous, Early or Lower Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch or series (stratigraphy), S ...

through early Albian

The Albian is both an age (geology), age of the geologic timescale and a stage (stratigraphy), stage in the stratigraphic column. It is the youngest or uppermost subdivision of the Early Cretaceous, Early/Lower Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch/s ...

stages of the early Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

, about 115 to 108 Ma. Additionally, teeth found in the Arundel Clay Facies (mid-Aptian), of the Potomac Formation

The Potomac Group is a Group (geology), geologic group in Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, and Virginia. It preserves fossils dating back to the Cretaceous Period (geology), period. An indeterminate tyrannosauroidea, tyrannosauroid and ''Priconod ...

on the Atlantic Coastal Plain

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

may be assigned to the genus.

The first remains were uncovered in 1931 in southern Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

near the town of Billings

Billings is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Montana, with a population of 117,116 as of the 2020 census. Located in the south-central portion of the state, it is the seat of Yellowstone County and the principal city of the Billin ...

. The team leader, paleontologist Barnum Brown

Barnum Brown (February 12, 1873 – February 5, 1963), commonly referred to as Mr. Bones, was an American paleontologist. He discovered the first documented remains of ''Tyrannosaurus'' during a career that made him one of the most famous fossil ...

, was primarily concerned with excavating and preparing the remains of the ornithopod

Ornithopoda () is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs, called ornithopods (). They represent one of the most successful groups of herbivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous. The most primitive members of the group were bipedal and relatively sm ...

dinosaur ''Tenontosaurus

''Tenontosaurus'' ( ; ) is a genus of iguanodontian ornithopod dinosaur. It had an unusually long, broad tail, which like its back was stiffened with a network of bony tendons.

The genus is known from the late Aptian to Albian ages of the Early ...

'', but in his field report from the dig site to the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

, he reported the discovery of a small carnivorous dinosaur close to a ''Tenontosaurus'' skeleton, "but encased in lime difficult to prepare." He informally called the animal "Daptosaurus agilis" and made preparations for describing it and having the skeleton, specimen AMNH 3015, put on display, but never finished this work. Brown brought back from the Cloverly Formation the skeleton of a smaller theropod with seemingly oversized teeth that he informally named "Megadontosaurus". John Ostrom

John Harold Ostrom (February 18, 1928 – July 16, 2005) was an American paleontologist who revolutionized the modern understanding of dinosaurs. Ostrom's work inspired what his pupil Robert T. Bakker has termed a " dinosaur renaissance".

Begin ...

, reviewing this material decades later, realized that the teeth came from ''Deinonychus'', but the skeleton came from a completely different animal. He named this skeleton ''Microvenator

''Microvenator'' (meaning "small hunter") is a genus of dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous Cloverly Formation in what is now south central Montana. ''Microvenator'' was an oviraptorosaurian theropod. The holotype fossil is an incomplete skeleton, ...

''.

A little more than thirty years later, in August 1964, paleontologist John Ostrom led an expedition from Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

's Peabody Museum of Natural History

The Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University (also known as the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History or the Yale Peabody Museum) is one of the oldest, largest, and most prolific university natural history museums in the world. It ...

which discovered more skeletal material near Bridger. Expeditions during the following two summers uncovered more than 1,000 bones, among which were at least three individuals. Since the association between the various recovered bones was weak, making the exact number of individual animals represented impossible to determine properly, the type

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* ...

specimen (YPM 5205) of ''Deinonychus'' was restricted to the complete left foot and partial right foot that definitely belonged to the same individual. The remaining specimens were catalogued in fifty separate entries at Yale's Peabody Museum although they could have been from as few as three individuals.

Later study by Ostrom and Grant E. Meyer analyzed their own material as well as Brown's "Daptosaurus" in detail and found them to be the same species. Ostrom first published his findings in February 1969, giving all the referred remains the new name of ''Deinonychus antirrhopus''. The specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

"''antirrhopus''", from Greek ἀντίρροπος, means "counterbalancing" and refers to the likely purpose of a stiffened tail. In July 1969, Ostrom published a very extensive monograph

A monograph is generally a long-form work on one (usually scholarly) subject, or one aspect of a subject, typically created by a single author or artist (or, sometimes, by two or more authors). Traditionally it is in written form and published a ...

on ''Deinonychus''.

Though a myriad of bones was available by 1969, many important ones were missing or hard to interpret. There were few postorbital skull elements, no femurs, no sacrum, no furcula or sternum, missing vertebrae, and (Ostrom thought) only a tiny fragment of a coracoid. Ostrom's skeletal reconstruction of ''Deinonychus'' included a very unusual pelvic bone—a pubis that was trapezoidal and flat, unlike that of other theropods, but which was the same length as the ischium and which was found right next to it.

Further findings

In 1974, Ostrom published another monograph on the shoulder of ''Deinonychus'' in which he realized that the pubis that he had described was actually a coracoid—a shoulder element. In that same year, another specimen of ''Deinonychus'', MCZ 4371, was discovered and excavated in Montana by Steven Orzack during a Harvard University expedition headed by Farish Jenkins. This discovery added several new elements: well preserved femora, pubes, a sacrum, and better ilia, as well as elements of the pes and metatarsus. Ostrom described this specimen and revised his skeletal restoration of ''Deinonychus''. This time it showed the very long pubis, and Ostrom began to suspect that they may have even been a little retroverted like those of birds.

In 1974, Ostrom published another monograph on the shoulder of ''Deinonychus'' in which he realized that the pubis that he had described was actually a coracoid—a shoulder element. In that same year, another specimen of ''Deinonychus'', MCZ 4371, was discovered and excavated in Montana by Steven Orzack during a Harvard University expedition headed by Farish Jenkins. This discovery added several new elements: well preserved femora, pubes, a sacrum, and better ilia, as well as elements of the pes and metatarsus. Ostrom described this specimen and revised his skeletal restoration of ''Deinonychus''. This time it showed the very long pubis, and Ostrom began to suspect that they may have even been a little retroverted like those of birds.

Museum of Comparative Zoology

The Museum of Comparative Zoology (formally the Agassiz Museum of Comparative Zoology and often abbreviated to MCZ) is a zoology museum located on the grounds of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It is one of three natural-history r ...

at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

. The American Museum and Harvard specimens are from a different locality than the Yale specimens. Even these two skeletal mounts are lacking elements, including the sterna, sternal ribs, furcula, and gastralia.Parsons, W.L. & K.M. (2009). "Further Descriptions of the Osteology of ''Deinonychus antirrhopus'' (Saurischia, Theropoda)". ''Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences''. 38.

Even after all Ostrom's work, several small blocks of lime-encased material remained unprepared in storage at the American Museum. These consisted mostly of isolated bones and bone fragments, including the original matrix, or surrounding rock in which the specimens were initially buried. An examination of these unprepared blocks by Gerald Grellet-Tinner and Peter Makovicky in 2000 revealed an interesting, overlooked feature. Several long, thin bones identified on the blocks as ossified tendons (structures that helped stiffen the tail of ''Deinonychus'') turned out to actually represent gastralia

Gastralia (: gastralium) are dermal bones found in the ventral body wall of modern crocodilians and tuatara, and many prehistoric tetrapods. They are found between the sternum and pelvis, and do not articulate with the vertebrae. In these reptil ...

(abdominal ribs). More significantly, a large number of previously unnoticed fossilized eggshells were discovered in the rock matrix that had surrounded the original ''Deinonychus'' specimen.

In a subsequent, more detailed report, on the eggshells, Grellet-Tinner and Makovicky concluded that the egg

An egg is an organic vessel grown by an animal to carry a possibly fertilized egg cell (a zygote) and to incubate from it an embryo within the egg until the embryo has become an animal fetus that can survive on its own, at which point the ...

almost certainly belonged to ''Deinonychus'', representing the first dromaeosaurid egg to be identified. Moreover, the external surface of one eggshell was found in close contact with the gastralia suggesting that ''Deinonychus'' might have brooded its eggs. This implies that ''Deinonychus'' used body heat transfer as a mechanism for egg incubation, and indicates an endotherm

An endotherm (from Greek ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" and θέρμη ''thermē'' "heat") is an organism that maintains its body at a metabolically favorable temperature, largely by the use of heat released by its internal bodily functions inst ...

y similar to modern birds. Further study by Gregory Erickson and colleagues finds that this individual was 13 or 14 years old at death and its growth had plateaued. Unlike other theropods in their study of specimens found associated with eggs or nests, it had finished growing at the time of its death.

Implications

Ostrom's description of ''Deinonychus'' in 1969 has been described as the most important single discovery of dinosaur paleontology in the mid-20th century. The discovery of this clearly active, agile predator did much to change the scientific (and popular) conception of dinosaurs and opened the door to speculation that some dinosaurs may have beenwarm-blooded

Warm-blooded is a term referring to animal species whose bodies maintain a temperature higher than that of their environment. In particular, homeothermic species (including birds and mammals) maintain a stable body temperature by regulating ...

. This development has been termed the dinosaur renaissance. Several years later, Ostrom noted similarities between the forefeet of ''Deinonychus'' and that of birds, an observation which led him to revive the hypothesis that birds are descended from dinosaurs. Forty years later, this idea is almost universally accepted.

Because of its extremely bird-like anatomy and close relationship to other dromaeosaurids, paleontologists hypothesize that ''Deinonychus'' was probably covered in feathers. Clear fossil evidence of modern avian-style feathers exists for several related dromaeosaurids, including ''Velociraptor'' and ''Microraptor'', though no direct evidence is yet known for ''Deinonychus'' itself. When conducting studies of such areas as the range of motion in the forelimbs, paleontologists like Phil Senter have taken the likely presence of wing feathers (as present in all known dromaeosaurs with skin impressions) into consideration.

Description

Based on the few fully mature specimens,

Based on the few fully mature specimens, Paul

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo ...

estimated that ''Deinonychus'' could reach in length, with a skull length of , a hip height of and a body mass of . Campione and his colleagues proposed a higher mass estimate of based on femur and humerus circumference. The skull was equipped with powerful jaws lined with around seventy curved, blade-like teeth. Studies of the skull have progressed a great deal over the decades. Ostrom reconstructed the partial, imperfectly preserved skulls that he had as triangular, broad, and fairly similar to ''Allosaurus

''Allosaurus'' ( ) is an extinct genus of theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic period ( Kimmeridgian to late Tithonian ages). The first fossil remains that could definitively be ascribed to th ...

''. Additional ''Deinonychus'' skull material and closely related species found with good three-dimensional preservation show that the palate was more vaulted than Ostrom thought, making the snout far narrower, while the jugals flared broadly, giving greater stereoscopic vision. The skull of ''Deinonychus'' was different from that of ''Velociraptor'', however, in that it had a more robust skull roof, like that of ''Dromaeosaurus

''Dromaeosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of Dromaeosauridae, dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period (middle late Campanian and Maastrichtian), sometime between 80 and 69 million years ago, in Alberta, Canada and th ...

'', and did not have the depressed nasals of ''Velociraptor''. Both the skull and the lower jaw had fenestra

A fenestra (fenestration; : fenestrae or fenestrations) is any small opening or pore, commonly used as a term in the biology, biological sciences. It is the Latin word for "window", and is used in various fields to describe a pore in an anatomy, ...

e (skull openings) which reduced the weight of the skull. In ''Deinonychus'', the antorbital fenestra

An antorbital fenestra (plural: fenestrae) is an opening in the skull that is in front of the eye sockets. This skull character is largely associated with Archosauriformes, archosauriforms, first appearing during the Triassic Period. Among Extant ...

, a skull opening between the eye and nostril, was particularly large.

''Deinonychus'' possessed large "hands" (

''Deinonychus'' possessed large "hands" (manus

Manus may refer to:

Relating to locations around New Guinea

*Manus Island, a Papua New Guinean island in the Admiralty Archipelago

** Manus languages, languages spoken on Manus and islands close by

** Manus Regional Processing Centre, an offshore ...

) with three claws on each forelimb. The first digit was shortest and the second was longest. Each hind foot bore a sickle-shaped claw on the second digit, which was probably used during predation.

No skin impressions have ever been found in association with fossils of ''Deinonychus''. Nonetheless, the evidence suggests that the Dromaeosauridae

Dromaeosauridae () is a family of feathered coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs. They were generally small to medium-sized feathered carnivores that flourished in the Cretaceous Period. The name Dromaeosauridae means 'running lizards', from ...

, including ''Deinonychus'', had feathers. The genus ''Microraptor

''Microraptor'' (Greek language, Greek, μικρός, ''mīkros'': "small"; Latin language, Latin, ''raptor'': "one who seizes") is a genus of small, four-winged dromaeosaurid dinosaurs. Numerous well-preserved fossil specimens have been recovere ...

'' is both older geologically and more primitive phylogenetically than ''Deinonychus'', and within the same family. Multiple fossils of ''Microraptor

''Microraptor'' (Greek language, Greek, μικρός, ''mīkros'': "small"; Latin language, Latin, ''raptor'': "one who seizes") is a genus of small, four-winged dromaeosaurid dinosaurs. Numerous well-preserved fossil specimens have been recovere ...

'' preserve pennaceous, vaned feathers like those of modern birds on the arms, legs, and tail, along with covert and contour feathers. ''Velociraptor

''Velociraptor'' (; ) is a genus of small dromaeosaurid dinosaurs that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous epoch, about 75 million to 71 million years ago. Two species are currently recognized, although others have been assigned in th ...

'' is geologically younger than ''Deinonychus'', but even more closely related. A specimen of ''Velociraptor'' has been found with quill knobs on the ulna. Quill knobs are where the follicular ligaments attached, and are a direct indicator of feathers of modern aspect.

Classification

''Deinonychus antirrhopus'' is one of the best knowndromaeosaurid

Dromaeosauridae () is a family (biology), family of feathered coelurosaurian Theropoda, theropod dinosaurs. They were generally small to medium-sized feathered carnivores that flourished in the Cretaceous period (geology), Period. The name Drom ...

species, and also a close relative of the smaller ''Velociraptor

''Velociraptor'' (; ) is a genus of small dromaeosaurid dinosaurs that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous epoch, about 75 million to 71 million years ago. Two species are currently recognized, although others have been assigned in th ...

'', which is found in younger, Late Cretaceous-age rock formations in Central Asia. The clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

they form is called Velociraptorinae

Eudromaeosauria ( ; "true dromaeosaurs") is a subgroup of terrestrial dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaurs. They were small to large-sized predators that flourished during the Cretaceous Period. Eudromaeosaur fossils are known almost exclusively f ...

. The subfamily name Velociraptorinae was first coined by Rinchen Barsbold

Rinchen Barsbold (, Rinchyengiin Barsbold, born December 21, 1935, in Ulaanbaatar) is a Mongolian paleontologist and geologist. He works with the Institute of Geology, at Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. He is an expert in vertebrate paleontology and Mesozo ...

in 1983 and originally contained the single genus ''Velociraptor''. Later, Phil Currie

Philip John Currie (born March 13, 1949) is a Canadian palaeontologist and museum curator who helped found the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Drumheller, Alberta and is now a professor at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. In the ...

included most of the dromaeosaurids.abstract

) Two Late Cretaceous genera, ''

Tsaagan

''Tsaagan'' (meaning "white") is a genus of dromaeosaurid dinosaur from the Djadokhta Formation of the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia.

Discovery and naming

The holotype of ''Tsaagan'' was discovered in 1996 and first identified as a specimen of ' ...

'' from Mongolia and the North American ''Saurornitholestes

''Saurornitholestes'' ("lizard-bird thief") is a genus of carnivorous dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur from the late Cretaceous of Canada (Alberta and Saskatchewan) and the United States (Montana, New Mexico, Alabama, and South Carolina).

Two spe ...

'', may also be close relatives, but the latter is poorly known and hard to classify. ''Velociraptor'' and its allies are regarded as using their claws more than their skulls as killing tools, as opposed to dromaeosaurines like ''Dromaeosaurus

''Dromaeosaurus'' (; ) is a genus of Dromaeosauridae, dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period (middle late Campanian and Maastrichtian), sometime between 80 and 69 million years ago, in Alberta, Canada and th ...

'', which have stockier skulls. Phylogenetically

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical data ...

, the dromaeosaurids represent one of the non-avialan dinosaur groups most closely related to birds. The cladogram below follows a 2015 analysis by paleontologists Robert DePalma, David Burnham, Larry Martin, Peter Larson, and Robert Bakker, using updated data from the Theropod Working Group. This study currently classifies ''Deinonychus'' as a member of the Dromaeosaurinae.

A 2021 study of the dromaeosaurid '' Kansaignathus'' recovered ''Deinonychus'' as a velociraptorine rather than a dromaeosaurine, with ''Kansaignathus'' being an intermediate basal form more advanced than ''Deinonychus'' but more primitive than ''Velociraptor''. The cladogram below showcases these newly described relationships:

A study in 2022, however, reclassified ''Deinonychus'' as a basal member of Dromaeosaurinae again.

A 2021 study of the dromaeosaurid '' Kansaignathus'' recovered ''Deinonychus'' as a velociraptorine rather than a dromaeosaurine, with ''Kansaignathus'' being an intermediate basal form more advanced than ''Deinonychus'' but more primitive than ''Velociraptor''. The cladogram below showcases these newly described relationships:

A study in 2022, however, reclassified ''Deinonychus'' as a basal member of Dromaeosaurinae again.

Paleobiology

Predatory behavior

In 2009, Manning and colleagues interpreted dromaeosaur claw tips as functioning as a puncture and gripping element, whereas the expanded rear portion of the claw transferred load stress through the structure.Manning, P. L., Margetts, L., Johnson, M. R., Withers, P., Sellers, W. I., Falkingham, P. L., Mummery, P. M., Barrett, P. M. and Raymont, D. R. 2009. Biomechanics of dromaeosaurid dinosaur claws: application of x-ray microtomography, nanoindentation and finite element analysis. Anatomical Record, 292, 1397-1405. They argue that the anatomy, form, and function of the foot's recurved digit II and hand claws of dromaeosaurs support a prey capture/grappling/climbing function. The team also suggest that a ratchet-like ‘‘locking’’ ligament might have provided an energy-efficient way for dromaeosaurs to hook their recurved digit II claw into prey. Shifting body weight locked the claws passively, allowing their jaws to dispatch prey. They conclude that the enhanced climbing abilities of dromaeosaur dinosaurs supported a scansorial (climbing) phase in the evolution of flight. In 2011, Denver Fowler and colleagues suggested a new method by which ''Deinonychus'' and other dromaeosaurs may have captured and restrained prey. This model, known as the "raptor prey restraint" (RPR) model of predation, proposes that ''Deinonychus'' killed its prey in a manner very similar to extantaccipitrid

The Accipitridae () is one of the four family (biology), families within the order (biology), order Accipitriformes, and is a family of small to large Bird of prey, birds of prey with strongly hooked bills and variable morphology based on diet. Th ...

birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as (although not the same as) raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively predation, hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and smaller birds). In addition to speed ...

: by leaping onto its quarry, pinning it under its body weight, and gripping it tightly with the large, sickle-shaped claws. Like accipitrids, the dromaeosaur would then begin to feed on the animal while still alive, until it eventually died from blood loss and organ failure. This proposal is based primarily on comparisons between the morphology and proportions of the feet and legs of dromaeosaurs to several groups of extant birds of prey with known predatory behaviors. Fowler found that the feet and legs of dromaeosaurs most closely resemble those of eagle

Eagle is the common name for the golden eagle, bald eagle, and other birds of prey in the family of the Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of Genus, genera, some of which are closely related. True eagles comprise the genus ''Aquila ( ...

s and hawk

Hawks are birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. They are very widely distributed and are found on all continents, except Antarctica.

The subfamily Accipitrinae includes goshawks, sparrowhawks, sharp-shinned hawks, and others. This ...

s, especially in terms of having an enlarged second claw and a similar range of grasping motion. However, the short metatarsus

The metatarsal bones or metatarsus (: metatarsi) are a group of five long bones in the midfoot, located between the tarsal bones (which form the heel and the ankle) and the phalanges ( toes). Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are ...

and foot strength would have been more similar to that of owl

Owls are birds from the order Strigiformes (), which includes over 200 species of mostly solitary and nocturnal birds of prey typified by an upright stance, a large, broad head, binocular vision, binaural hearing, sharp talons, and feathers a ...

s. The RPR method of predation would be consistent with other aspects of ''Deinonychuss anatomy, such as their unusual jaw and arm morphology. The arms were likely covered in long feathers, and may have been used as flapping stabilizers for balance while atop struggling prey, along with the stiff counterbalancing tail. Its jaws, thought to have had a comparatively weak bite force, might be used for saw motion bites, like the modern Komodo dragon which also has a weak bite force, to finish off its prey if its kicks were not powerful enough. In 2020, Powers and colleagues analyzed the snout morphology of dromaeosaurids from North America and Asia, their findings suggest that the maxilla of ''Deinonychus'' was short and deep, resembling that of short-snouted canids, suggesting that ''Deinonychus'' specialized on larger prey. Within the same year, isotopic analysis done by Frederickson and colleagues, found that adult ''Deinonychus'' were likely feeding on ''Tenontosaurus'' to some degree.

Bite force

Bite force estimates for ''Deinonychus'' were first produced in 2005, based on reconstructed jaw musculature. This study concluded that ''Deinonychus'' likely had a maximum bite force only 15% that of the modern American alligator. A 2010 study by Paul Gignac and colleagues attempted to estimate the bite force based directly on newly discovered ''Deinonychus'' tooth puncture marks in the bones of a ''Tenontosaurus''. These puncture marks came from a large individual, and provided the first evidence that large ''Deinonychus'' could bite through bone. Using the tooth marks, Gignac's team were able to determine that the bite force of ''Deinonychus'' was significantly higher than earlier studies had estimated by biomechanical studies alone. They found the bite force of ''Deinonychus'' to be between 4,100 and 8,200

Bite force estimates for ''Deinonychus'' were first produced in 2005, based on reconstructed jaw musculature. This study concluded that ''Deinonychus'' likely had a maximum bite force only 15% that of the modern American alligator. A 2010 study by Paul Gignac and colleagues attempted to estimate the bite force based directly on newly discovered ''Deinonychus'' tooth puncture marks in the bones of a ''Tenontosaurus''. These puncture marks came from a large individual, and provided the first evidence that large ''Deinonychus'' could bite through bone. Using the tooth marks, Gignac's team were able to determine that the bite force of ''Deinonychus'' was significantly higher than earlier studies had estimated by biomechanical studies alone. They found the bite force of ''Deinonychus'' to be between 4,100 and 8,200 newtons

The newton (symbol: N) is the unit of force in the International System of Units (SI). Expressed in terms of SI base units, it is 1 kg⋅m/s2, the force that accelerates a mass of one kilogram at one metre per second squared.

The unit i ...

, greater than living carnivorous mammals including the hyena

Hyenas or hyaenas ( ; from Ancient Greek , ) are feliform carnivoran mammals belonging to the family Hyaenidae (). With just four extant species (each in its own genus), it is the fifth-smallest family in the order Carnivora and one of the sma ...

, and equivalent to a similarly-sized alligator.

However, this estimate has come into question, as it was based on bite marks rather than a ''Deinonychus'' skull. A recent 2022 study used a ''Deinonychus'' skull for their estimate and calculated .

Gignac and colleagues also noted, however, that bone puncture marks from ''Deinonychus'' are relatively rare, and unlike larger theropods with many known puncture marks like ''Tyrannosaurus

''Tyrannosaurus'' () is a genus of large theropod dinosaur. The type species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' ( meaning 'king' in Latin), often shortened to ''T. rex'' or colloquially t-rex, is one of the best represented theropods. It lived througho ...

'', ''Deinonychus'' probably did not frequently bite through or eat bone. Instead, they probably used their strong bite force for defense or to capture prey, rather than for feeding.

A 2024 study by Tse, Miller, and Pittman et al., focusing on the skull morphology and bite forces of various dromaeosaurids discovered that ''Deinonychus'', the largest taxon examined, had a skull that was well adapted to hunting of large vertebrates and delivering powerful bites to prey alongside ''Dromaeosaurus'', to which it was compared. In this study, ''Deinonychus'' represented the most extreme specializations compared to other dromaeosaurids when it came to its adaptations. The same study also revealed that ''Deinonychus skull was less resistant to bite forces than that of ''Velociraptor'', which apparently was engaging in more scavenging behavior, suggesting high bite force resistance was more common in dromaeosaurid taxa that were obtaining food through scavenging more than engaging in active predation. It is also suggested in these findings that Deinonychus may have fed by using neck-driven pullback movements to dismember carcasses when feeding, akin to modern varanid lizards.

Limb function

Despite being the most distinctive feature of ''Deinonychus'', the shape and curvature of the

Despite being the most distinctive feature of ''Deinonychus'', the shape and curvature of the sickle

A sickle, bagging hook, reaping-hook or grasshook is a single-handed agricultural tool designed with variously curved blades and typically used for harvesting or reaping grain crops, or cutting Succulent plant, succulent forage chiefly for feedi ...

claw varies between specimens. The type specimen described by Ostrom in 1969 has a strongly curved sickle claw, while a newer specimen described in 1976 had a claw with much weaker curvature, more similar in profile with the 'normal' claws on the remaining toes. Ostrom suggested that this difference in the size and shape of the sickle claws could be due to individual, sexual, or age-related variation, but admitted he could not be sure.

There is anatomical and trackway evidence that this talon was held up off the ground while the dinosaur walked on the third and fourth toes.

Ostrom suggested that ''Deinonychus'' could kick with the sickle claw to cut and slash at its prey. Some researchers even suggested that the talon was used to disembowel large ceratopsia

Ceratopsia or Ceratopia ( or ; Ancient Greek, Greek: "horned faces") is a group of herbivore, herbivorous, beaked dinosaurs that thrived in what are now North America, Asia and Europe, during the Cretaceous Period (geology), Period, although ance ...

n dinosaurs.Adams, Dawn (1987) "The bigger they are, the harder they fall: Implications of ischial curvature in ceratopsian dinosaurs" pp. 1–6 in Currie, Philip J. and Koster, E. (eds) Fourth symposium on mesozoic terrestrial ecosystems. Tyrrell Museum, Drumheller, Canada Other studies have suggested that the sickle claws were not used to slash but rather to deliver small stabs to the victim. In 2005, Manning and colleagues ran tests on a robotic replica that precisely matched the anatomy of ''Deinonychus'' and ''Velociraptor

''Velociraptor'' (; ) is a genus of small dromaeosaurid dinosaurs that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous epoch, about 75 million to 71 million years ago. Two species are currently recognized, although others have been assigned in th ...

'', and used hydraulic rams to make the robot strike a pig carcass. In these tests, the talons made only shallow punctures and could not cut or slash. The authors suggested that the talons would have been more effective in climbing than in dealing killing blows. In 2009, Manning and colleagues undertook additional analysis dromaeosaur claw function, using a numerical modelling approach to generate a 3D finite element stress/ strain map of a Velociraptor hand claw. They went on to quantitatively evaluate the mechanical behavior of dromaeosaur claws and their function. They state that dromaeosaur claws were well-adapted for climbing as they were resistant to forces acting in a single (longitudinal) plane, due to gravity.

Ostrom compared ''Deinonychus'' to the ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds. Two living species are recognised, the common ostrich, native to large parts of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Somali ostrich, native to the Horn of Africa.

They are the heaviest and largest living birds, w ...

and cassowary

Cassowaries (; Biak: ''man suar'' ; ; Papuan: ''kasu weri'' ) are flightless birds of the genus ''Casuarius'', in the order Casuariiformes. They are classified as ratites, flightless birds without a keel on their sternum bones. Cassowaries a ...

. He noted that the bird species can inflict serious injury with the large claw on the second toe. The cassowary has claws up to long. Ostrom cited Gilliard (1958) in saying that they can sever an arm or disembowel a man. Kofron (1999 and 2003) studied 241 documented cassowary attacks and found that one human and two dogs had been killed, but no evidence that cassowaries can disembowel or dismember other animals.Kofron, Christopher P. (1999) "Attacks to humans and domestic animals by the southern cassowary (''Casuarius casuarius johnsonii'') in Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

, Australia Cassowaries use their claws to defend themselves, to attack threatening animals, and in agonistic displays such as the Bowed Threat Display. The seriema

The seriemas are the sole living members of the small bird family Cariamidae (the entire family is also referred to as "seriemas"), which is also the only surviving lineage of the order Cariamiformes. Once believed to be related to cranes, they ...

also has an enlarged second toe claw, and uses it to tear apart small prey items for swallowing. In 2011, a study suggested that the sickle claw would likely have been used to pin down prey while biting it, rather than as a slashing weapon.

Biomechanical studies by Ken Carpenter in 2002 confirmed that the most likely function of the forelimbs in predation was grasping, as their great lengths would have permitted longer reach than for most other theropods. The rather large and elongated

Biomechanical studies by Ken Carpenter in 2002 confirmed that the most likely function of the forelimbs in predation was grasping, as their great lengths would have permitted longer reach than for most other theropods. The rather large and elongated coracoid

A coracoid is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is present as part of the scapula, but this is n ...

, indicating powerful muscles in the forelimbs, further strengthened this interpretation. Carpenter's biomechanical studies using bone casts also showed that ''Deinonychus'' could not fold its arms against its body like a bird ("avian folding"), contrary to what was inferred from the earlier 1985 descriptions by Jacques Gauthier

Jacques Armand Gauthier (born June 7, 1948, in New York City) is an American vertebrate paleontologist, comparative morphologist, and systematist, and one of the founders of the use of cladistics in biology.

Life and career

Gauthier is the ...

and Gregory S. Paul

Gregory Scott Paul (born December 24, 1954) is an American freelance researcher, author and illustrator who works in paleontology. He is best known for his work and research on theropoda, theropod dinosaurs and his detailed illustrations, both l ...

in 1988.

Studies by Phil Senter in 2006 indicated that ''Deinonychus'' forelimbs could be used not only for grasping, but also for clutching objects towards the chest. If ''Deinonychus'' had feathered fingers and wings, the feathers would have limited the range of motion of the forelimbs to some degree. For example, when ''Deinonychus'' extended its arm forward, the 'palm' of the hand automatically rotated to an upward-facing position. This would have caused one wing to block the other if both forelimbs were extended at the same time, leading Senter to conclude that clutching objects to the chest would have only been accomplished with one arm at a time. The function of the fingers would also have been limited by feathers; for example, only the third digit of the hand could have been employed in activities such as probing crevices for small prey items, and only in a position perpendicular to the main wing. Alan Gishlick, in a 2001 study of ''Deinonychus'' forelimb mechanics, found that even if large wing feathers were present, the grasping ability of the hand would not have been significantly hindered; rather, grasping would have been accomplished perpendicular to the wing, and objects likely would have been held by both hands simultaneously in a "bear hug" fashion, findings which have been supported by the later forelimb studies by Carpenter and Senter. In a 2001 study conducted by Bruce Rothschild and other paleontologists, 43 hand bones and 52 foot bones referred to ''Deinonychus'' were examined for signs of stress fracture

A stress fracture is a fatigue-induced bone fracture caused by repeated stress over time. Instead of resulting from a single severe impact, stress fractures are the result of accumulated injury from repeated submaximal loading, such as running ...

; none were found.Rothschild, B., Tanke, D. H., and Ford, T. L., 2001, Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 331–336. The second phalanx of the second toe in the specimen YPM 5205 has a healed fracture.Molnar, R. E., 2001, Theropod paleopathology: a literature survey: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 337–363.

Parsons and Parsons have shown that juvenile and sub-adult specimens of ''Deinonychus'' display some morphological differences from the adults. For instance, the arms of the younger specimens were proportionally longer than those of the adults, a possible indication of difference in behavior between young and adults. Another example of this could be the function of the pedal claws. Parsons and Parsons have suggested that the claw curvature (which Ostrom

Parsons and Parsons have shown that juvenile and sub-adult specimens of ''Deinonychus'' display some morphological differences from the adults. For instance, the arms of the younger specimens were proportionally longer than those of the adults, a possible indication of difference in behavior between young and adults. Another example of this could be the function of the pedal claws. Parsons and Parsons have suggested that the claw curvature (which Ostrom 976

Year 976 ( CMLXXVI) was a leap year starting on Saturday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Byzantine Empire

* January 10 – Emperor John I Tzimiskes dies at Constantinople, after returning from a second campaign against ...

had already shown was different between specimens) maybe was greater for juvenile ''Deinonychus'', as this could help it climb in trees, and that the claws became straighter as the animal became older and started to live solely on the ground. This was based on the hypothesis that some small dromaeosaurids used their pedal claws for climbing.

Locomotion

Dromaeosaurids, especially ''Deinonychus'', are often depicted as unusually fast-running animals in the popular media, and Ostrom himself speculated that ''Deinonychus'' was fleet-footed in his original description. However, when first described, a complete leg of ''Deinonychus'' had not been found, and Ostrom's speculation about the length of thefemur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many quadrupeds, four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The Femo ...

(upper leg bone) later proved to have been an overestimate. In a later study, Ostrom noted that the ratio of the femur to the tibia

The tibia (; : tibiae or tibias), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two Leg bones, bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outsi ...

(lower leg bone) is not as important in determining speed as the relative length of the foot and lower leg. In modern fleet-footed birds, like the ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds. Two living species are recognised, the common ostrich, native to large parts of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Somali ostrich, native to the Horn of Africa.

They are the heaviest and largest living birds, w ...

, the foot-tibia ratio is .95. In unusually fast-running dinosaurs, like ''Struthiomimus

''Struthiomimus'', meaning "ostrich-mimic" (from the Greek στρούθειος/''stroutheios'', or "of the ostrich", and μῖμος/''mimos'', meaning "mimic" or "imitator"), is a genus of ornithomimid dinosaurs from the late Cretaceous of Nor ...

'', the ratio is .68, but in ''Deinonychus'' the ratio is .48. Ostrom stated that the "only reasonable conclusion" is that ''Deinonychus'', while far from slow-moving, was not particularly fast compared to other dinosaurs, and certainly not as fast as modern flightless birds.

The low foot to lower leg ratio in ''Deinonychus'' is due partly to an unusually short metatarsus

The metatarsal bones or metatarsus (: metatarsi) are a group of five long bones in the midfoot, located between the tarsal bones (which form the heel and the ankle) and the phalanges ( toes). Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are ...

(upper foot bones). The ratio is actually larger in smaller individuals than in larger ones. Ostrom suggested that the short metatarsus may be related to the function of the sickle claw, and used the fact that it appears to get shorter as individuals aged as support for this. He interpreted all these features—the short second toe with enlarged claw, short metatarsus, etc.—as support for the use of the hind leg as an offensive weapon, where the sickle claw would strike downwards and backwards, and the leg pulled back and down at the same time, slashing and tearing at the prey. Ostrom suggested that the short metatarsus reduced overall stress on the leg bones during such an attack, and interpreted the unusual arrangement of muscle attachments in the ''Deinonychus'' leg as support for his idea that a different set of muscles was used in the predatory stroke than in walking or running. Therefore, Ostrom concluded that the legs of ''Deinonychus'' represented a balance between running adaptations needed for an agile predator, and stress-reducing features to compensate for its unique foot weapon.

In his 1981 study of Canadian dinosaur footprints, Richard Kool produced rough walking speed estimates based on several trackways made by different species in the

In his 1981 study of Canadian dinosaur footprints, Richard Kool produced rough walking speed estimates based on several trackways made by different species in the Gething Formation

Gething Formation is a stratigraphic unit of Lower Cretaceous (Aptian) age in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. It is present in northeastern British Columbia and western Alberta, and includes economically important coal deposits.

The formati ...

of British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

. Kool estimated one of these trackways, representing the ichnospecies

An ichnotaxon (plural ichnotaxa) is "a taxon based on the fossilized work of an organism", i.e. the non-human equivalent of an artifact. ''Ichnotaxon'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''íchnos'') meaning "track" and English , itself derived from ...

''Irenichnites gracilis'' (which may have been made by ''Deinonychus''), to have a walking speed of 10.1 kilometers per hour (6 miles per hour).

In a 2015 paper, it was reported after further analysis of immature fossils that the open and mobile nature of the shoulder joint might have meant that young ''Deinonychus'' were capable of some form of flight.

In 2016, Scott Persons IV and Currie examined the limb proportion of numerous theropods and found Dromaeosaurids weren’t cursorial

A cursorial organism is one that is adapted specifically to run. An animal can be considered cursorial if it has the ability to run fast (e.g. cheetah) or if it can keep a constant speed for a long distance (high endurance). "Cursorial" is often ...

animals due to their low CLP scores, with ''Deinonychus'' scoring -2.2, suggesting they couldn’t maintain high speeds for extended periods of time.

Eggs

The identification, in 2000, of a probable ''Deinonychus'' egg associated with one of the original specimens allowed comparison with other theropod dinosaurs in terms of egg structure, nesting, and reproduction. In their 2006 examination of the specimen, Grellet-Tinner and Makovicky examined the possibility that the dromaeosaurid had been feeding on the egg, or that the egg fragments had been associated with the ''Deinonychus'' skeleton by coincidence. They dismissed the idea that the egg had been a meal for the theropod, noting that the fragments were sandwiched between the belly ribs and forelimb bones, making it impossible that they represented contents of the animal's stomach. In addition, the manner in which the egg had been crushed and fragmented indicated that it had been intact at the time of burial, and was broken by the fossilization process. The idea that the egg was randomly associated with the dinosaur was also found to be unlikely; the bones surrounding the egg had not been scattered or disarticulated, but remained fairly intact relative to their positions in life, indicating that the area around and including the egg was not disturbed during preservation. The fact that these bones were belly ribs (

The identification, in 2000, of a probable ''Deinonychus'' egg associated with one of the original specimens allowed comparison with other theropod dinosaurs in terms of egg structure, nesting, and reproduction. In their 2006 examination of the specimen, Grellet-Tinner and Makovicky examined the possibility that the dromaeosaurid had been feeding on the egg, or that the egg fragments had been associated with the ''Deinonychus'' skeleton by coincidence. They dismissed the idea that the egg had been a meal for the theropod, noting that the fragments were sandwiched between the belly ribs and forelimb bones, making it impossible that they represented contents of the animal's stomach. In addition, the manner in which the egg had been crushed and fragmented indicated that it had been intact at the time of burial, and was broken by the fossilization process. The idea that the egg was randomly associated with the dinosaur was also found to be unlikely; the bones surrounding the egg had not been scattered or disarticulated, but remained fairly intact relative to their positions in life, indicating that the area around and including the egg was not disturbed during preservation. The fact that these bones were belly ribs (gastralia

Gastralia (: gastralium) are dermal bones found in the ventral body wall of modern crocodilians and tuatara, and many prehistoric tetrapods. They are found between the sternum and pelvis, and do not articulate with the vertebrae. In these reptil ...

), which are very rarely found articulated, supported this interpretation. All the evidence, according to Grellet-Tinner and Makovicky, indicates that the egg was intact beneath the body of the ''Deinonychus'' when it was buried. It is possible that this represents brooding or nesting behavior in ''Deinonychus'' similar to that seen in the related troodontid

Troodontidae is a clade of bird-like theropod dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic to Late Cretaceous. During most of the 20th century, troodontid fossils were few and incomplete and they have therefore been allied, at various times, with many dinos ...

s and oviraptorid

Oviraptoridae is a group of bird-like, herbivorous and omnivorous maniraptoran dinosaurs. Oviraptorids are characterized by their toothless, parrot-like beaks and, in some cases, elaborate crests. They were generally small, measuring between one ...

s, or that the egg was in fact inside the oviduct

The oviduct in vertebrates is the passageway from an ovary. In human females, this is more usually known as the fallopian tube. The eggs travel along the oviduct. These eggs will either be fertilized by spermatozoa to become a zygote, or will dege ...

when the animal died.

Examination of the ''Deinonychus'' egg's microstructure confirms that it belonged to a theropod, since it shares characteristics with other known theropod eggs and shows dissimilarities with ornithischia

Ornithischia () is an extinct clade of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek ...

n and sauropod

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; from '' sauro-'' + '' -pod'', 'lizard-footed'), is a clade of saurischian ('lizard-hipped') dinosaurs. Sauropods had very long necks, long tails, small heads (relative to the rest of their b ...

eggs. Compared to other maniraptora

Maniraptora is a clade of coelurosaurian dinosaurs which includes the birds and the non-avian dinosaurs that were more closely related to them than to ''Ornithomimus velox''. It contains the major subgroups Avialae, Dromaeosauridae, Troodontidae, ...

n theropods, the egg of ''Deinonychus'' is more similar to those of oviraptorids than to those of troodontids, despite studies that show the latter are more closely related to dromaeosaurids like ''Deinonychus''. While the egg was too badly crushed to accurately determine its size, Grellet-Tinner and Makovicky estimated a diameter of about based on the width of the pelvic canal through which the egg had to have passed. This size is similar to the diameter of the largest ''Citipati

''Citipati'' (; meaning "funeral pyre lord") is a genus of oviraptorid dinosaur that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous Period (geology), period, about 75 million to 71 million years ago. It is mainly known from the Ukhaa Tolgod locality ...

'' (an oviraptorid) eggs; ''Citipati'' and ''Deinonychus'' also shared the same overall body size, supporting this estimate. Additionally, the thicknesses of ''Citipati'' and ''Deinonychus'' eggshells are almost identical, and since shell thickness correlates with egg volume, this further supports the idea that the eggs of these two animals were about the same size.

A study published in November 2018 by Norell, Yang and Wiemann et al., indicates that ''Deinonychus'' laid blue eggs, likely to camouflage them as well as creating open nests. The study also indicates that ''Deinonychus'' and other dinosaurs that created open nests likely represent an origin of color in modern bird eggs as an adaptation both for recognition and camouflage against predators.

Social behavior

Scientists have debated whether or not ''Deinonychus'' was gregarious. ''Deinonychus'' teeth found in association with fossils of theornithopod

Ornithopoda () is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs, called ornithopods (). They represent one of the most successful groups of herbivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous. The most primitive members of the group were bipedal and relatively sm ...

dinosaur ''Tenontosaurus'' are quite common in the Cloverly Formation. Two quarries have been discovered that preserve fairly complete ''Deinonychus'' fossils near ''Tenontosaurus'' fossils. The first, the Yale quarry in the Cloverly of Montana, includes numerous teeth, four adult ''Deinonychus'' and one juvenile ''Deinonychus''. The association of this number of ''Deinonychus'' skeletons in a single quarry suggests that ''Deinonychus'' may have fed on that animal, and perhaps hunted it. Ostrom and Maxwell have even used this information to speculate that ''Deinonychus'' might have lived and hunted in packs.abstract

) The second such quarry is from the Antlers Formation of Oklahoma. The site contains six partial skeletons of ''Tenontosaurus'' of various sizes, along with one partial skeleton and many teeth of ''Deinonychus''. One tenontosaur humerus even bears what might be ''Deinonychus'' tooth marks. Brinkman ''et al.'' (1998) point out that ''Deinonychus'' had an adult mass of , whereas adult tenontosaurs were 1–4 metric tons. A solitary ''Deinonychus'' could not kill an adult tenontosaur, suggesting that pack hunting is possible. A 2007 study by Roach and Brinkman has called into question the gregariousness and cooperative pack hunting behavior of ''Deinonychus'', based on what is known of modern carnivore hunting and the

taphonomy

Taphonomy is the study of how organisms decay and become fossilized or preserved in the paleontological record. The term ''taphonomy'' (from Greek language, Greek , 'burial' and , 'law') was introduced to paleontology in 1940 by Soviet scientis ...

of tenontosaur sites. Modern archosaur