Sanskrit (; stem form ;

nominal singular , ,

) is a

classical language belonging to the

Indo-Aryan branch of the

Indo-European languages.

It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had

diffused there from the northwest in the late

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

.

Sanskrit is the

sacred language of

Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for a range of Indian religions, Indian List of religions and spiritual traditions#Indian religions, religious and spiritual traditions (Sampradaya, ''sampradaya''s) that are unified ...

, the language of classical

Hindu philosophy, and of historical texts of

Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

and

Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion whose three main pillars are nonviolence (), asceticism (), and a rejection of all simplistic and one-sided views of truth and reality (). Jainism traces its s ...

. It was a

link language in ancient and medieval South Asia, and upon transmission of Hindu and Buddhist culture to Southeast Asia, East Asia and Central Asia in the early medieval era, it became a language of religion and

high culture

In a society, high culture encompasses culture, cultural objects of Objet d'art, aesthetic value that a society collectively esteems as exemplary works of art, as well as the literature, music, history, and philosophy a society considers represen ...

, and of the political elites in some of these regions.

As a result, Sanskrit had a lasting effect on the languages of South Asia, Southeast Asia and East Asia, especially in their formal and learned vocabularies.

Sanskrit generally connotes several

Old Indo-Aryan language varieties.

The most archaic of these is the

Vedic Sanskrit

Vedic Sanskrit, also simply referred as the Vedic language, is the most ancient known precursor to Sanskrit, a language in the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan subgroup of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family. It is atteste ...

found in the

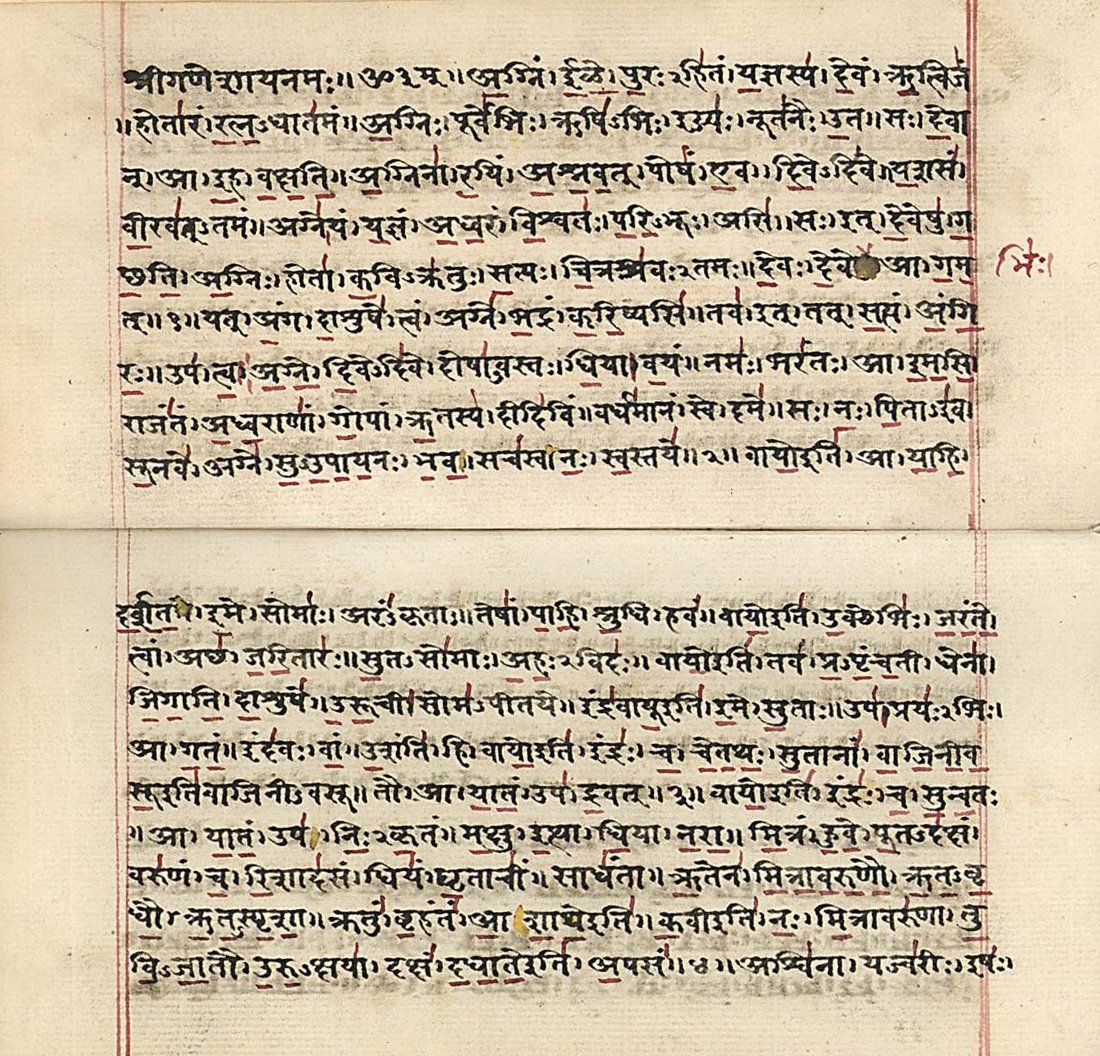

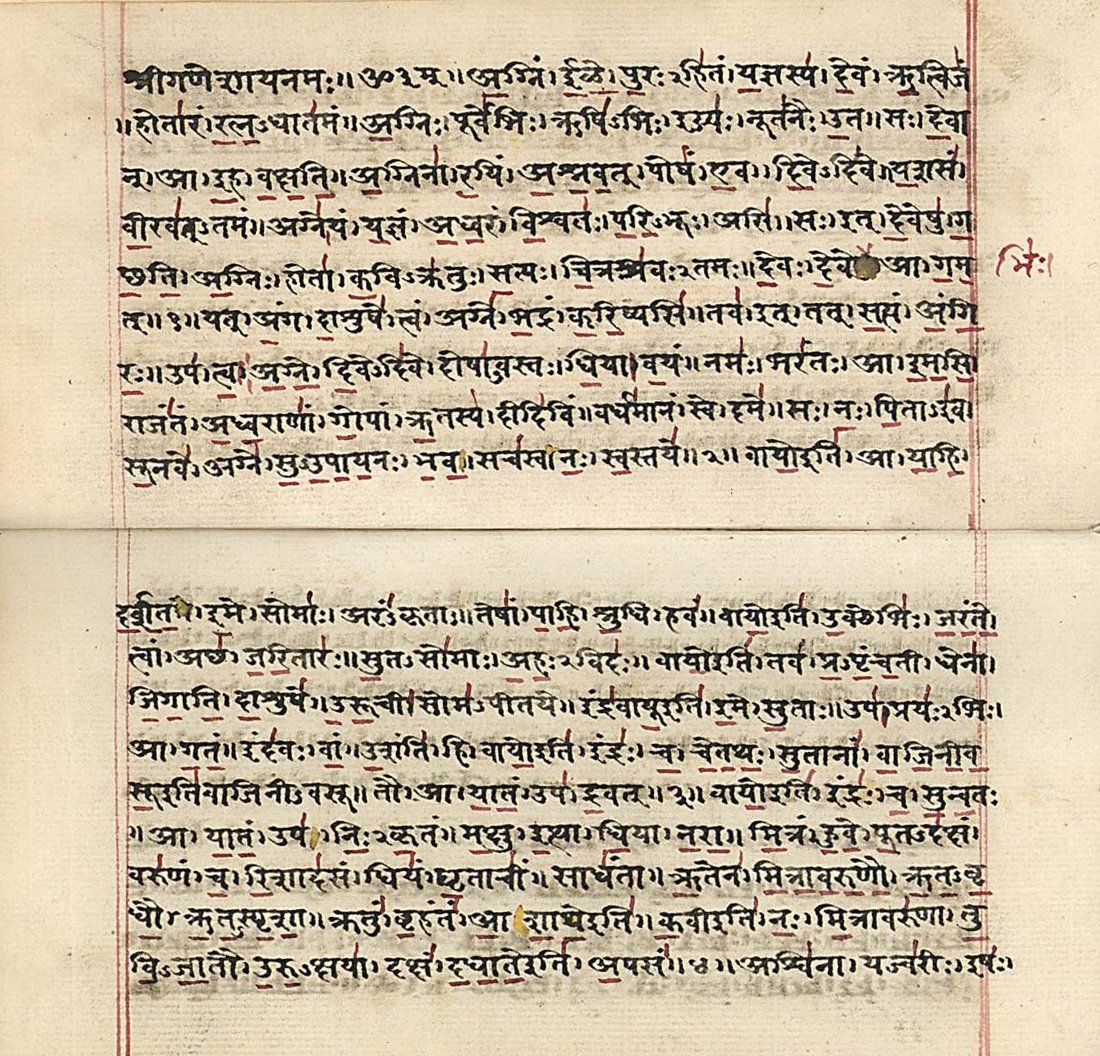

Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' (, , from wikt:ÓżŗÓżÜÓźŹ, ÓżŗÓżÜÓźŹ, "praise" and wikt:ÓżĄÓźćÓż”, ÓżĄÓźćÓż”, "knowledge") is an ancient Indian Miscellany, collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''s┼½ktas''). It is one of the four sacred canoni ...

, a collection of 1,028 hymns composed between 1500 and 1200 BCE by Indo-Aryan tribes migrating east from the mountains of what is today northern

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the AfghanistanŌĆōIran borde ...

across northern

Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

and into northwestern India.

Vedic Sanskrit interacted with the preexisting ancient languages of the subcontinent, absorbing names of newly encountered plants and animals; in addition, the

ancient Dravidian languages influenced Sanskrit's

phonology

Phonology (formerly also phonemics or phonematics: "phonemics ''n.'' 'obsolescent''1. Any procedure for identifying the phonemes of a language from a corpus of data. 2. (formerly also phonematics) A former synonym for phonology, often pre ...

and

syntax.

''Sanskrit'' can also more narrowly refer to

Classical Sanskrit, a refined and standardized grammatical form that emerged in the mid-1st millennium BCE and was codified in the most comprehensive of ancient grammars, the ''

Aß╣Żß╣Ł─üdhy─üy─½'' ('Eight chapters') of

P─üß╣ćini.

[ The greatest dramatist in Sanskrit, K─ülid─üsa, wrote in classical Sanskrit, and the foundations of modern arithmetic were first described in classical Sanskrit.]Greek language

Greek (, ; , ) is an Indo-European languages, Indo-European language, constituting an independent Hellenic languages, Hellenic branch within the Indo-European language family. It is native to Greece, Cyprus, Italy (in Calabria and Salento), south ...

families, the '' Gathas'' of old Avestan

Avestan ( ) is the liturgical language of Zoroastrianism. It belongs to the Iranian languages, Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family and was First language, originally spoken during the Avestan period, Old ...

and ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'' of Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

.Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-Euro ...

.Brahmic scripts

The Brahmic scripts, also known as Indic scripts, are a family of abugida writing systems. They are used throughout South Asia, Southeast Asia and parts of East Asia. They are descended from the Brahmi script of ancient India and are used b ...

, and in the modern era most commonly in Devanagari

Devanagari ( ; in script: , , ) is an Indic script used in the Indian subcontinent. It is a left-to-right abugida (a type of segmental Writing systems#Segmental systems: alphabets, writing system), based on the ancient ''Br─ühm─½ script, Br─ü ...

.[ there are no first-language speakers of Sanskrit in India.][ Quote: "What this data tells us is that it is very difficult to believe the notion that Jhiri is a "Sanskrit village" where everyone only speaks fluent Sanskrit at a mother tongue level. It is also difficult to accept that the lingua franca of the rural masses is Sanskrit, when most the majority of L1, L2 and L3 Sanskrit tokens are linked to urban areas. The predominance of Sanskrit across the Hindi belt also shows a particular cultural/geographic affection that does not spread equally across the rest of the country. In addition, the clustering with Hindi and English, in the majority of variations possible, also suggests that a certain class element is involved. Essentially, people who identify as speakers of Sanskrit appear to be urban and educated, which possibly implies that the affiliation with Sanskrit is related in some way to at least some sort of Indian, if not, Hindu, nationalism."][ Quote: "Consider the example of this faith-based development narrative that has evolved over the past decade in the state of Uttarakhand. In 2010, Sanskrit became the state's second official language. ... Recently, an updated policy has increased this top-down imposition of language shift, toward Sanskrit. The new policy aims to create a Sanskrit village in every "block" (administrative division) of Uttarakhand. The state of Uttarakhand consists of two divisions, 13 districts, 79 sub-districts and 97 blocks. ... There is hardly a Sanskrit village in even one block in Uttarakhand. The curious thing is that, while 70% of the state's total population live in rural areas, 100pc of the total 246 L1-Sanskrit tokens returned at the 2011 census are from Urban areas. No L1-Sanskrit token comes from any villager who identifies as an L1-Sanskrit speaker in Uttarakhand."]hymns

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' ...

and chants.

Etymology and nomenclature

In Sanskrit, the verbal adjective ' is a compound word consisting of ('together, good, well, perfected') and ''-'' ('made, formed, work').Vedic period

The Vedic period, or the Vedic age (), is the period in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age of the history of India when the Vedic literature, including the Vedas (ŌĆō900 BCE), was composed in the northern Indian subcontinent, between the e ...

onwards, state Annette Wilke and Oliver Moebus, resonating sound and its musical foundations attracted an "exceptionally large amount of linguistic, philosophical and religious literature" in India. Sound was visualized as "pervading all creation", another representation of the world itself; the "mysterious magnum" of Hindu thought. The search for perfection in thought and the goal of liberation were among the dimensions of sacred sound, and the common thread that wove all ideas and inspirations together became the quest for what the ancient Indians believed to be a perfect language, the "phonocentric episteme" of Sanskrit.

Sanskrit as a language competed with numerous, less exact vernacular Indian languages called ''Prakritic languages'' ('). The term literally means "original, natural, normal, artless", states Franklin Southworth. The relationship between Prakrit and Sanskrit is found in Indian texts dated to the 1st millennium CE. Pata├▒jali acknowledged that Prakrit is the first language, one instinctively adopted by every child with all its imperfections and later leads to the problems of interpretation and misunderstanding. The purifying structure of the Sanskrit language removes these imperfections. The early Sanskrit grammarian Daß╣ćßĖŹin

Daß╣ćßĖŹi or Daß╣ćßĖŹin (Sanskrit: Óż”ÓżŻÓźŹÓżĪÓż┐Óż©ÓźŹ) () was an Indian Sanskrit grammarian and author of prose romances. He is one of the best-known writers in Indian history.

Life

Daß╣ćßĖŹin's account of his life in ''Avantisundari-ka ...

states, for example, that much in the Prakrit languages is etymologically rooted in Sanskrit, but involves "loss of sounds" and corruptions that result from a "disregard of the grammar". Daß╣ćßĖŹin acknowledged that there are words and confusing structures in Prakrit that thrive independent of Sanskrit. This view is found in the writing of Bharata Muni

Bharata (Devanagari: ÓżŁÓż░Óżż) was a '' muni'' (sage) of ancient India. He is traditionally attributed authorship of the influential performing arts treatise '' Natya Shastra'', which covers ancient Indian dance, poetics, dramaturgy, and music ...

, the author of the ancient ''Natya Shastra

The ''N─üß╣Łya Sh─üstra'' (, ''N─üß╣Łya┼ø─üstra'') is a Sanskrit treatise on the performing arts. The text is attributed to sage Bharata, and its first complete compilation is dated to between 200 BCE and 200 CE, but estimates vary b ...

'' text. The early Jain scholar Namis─üdhu acknowledged the difference, but disagreed that Prakrit language was a corruption of Sanskrit. Namis─üdhu stated that the Prakrit language was the ('came before, origin') and that it came naturally to children, while Sanskrit was a refinement of Prakrit through "purification by grammar".

History

Origin and development

Sanskrit belongs to the Indo-European family of languages. It is one of the three earliest ancient documented languages that arose from a common root language now referred to as Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-Euro ...

:Vedic Sanskrit

Vedic Sanskrit, also simply referred as the Vedic language, is the most ancient known precursor to Sanskrit, a language in the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan subgroup of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family. It is atteste ...

( 1500ŌĆō500 BCE).

* Mycenaean Greek

Mycenaean Greek is the earliest attested form of the Greek language. It was spoken on the Greek mainland and Crete in Mycenaean Greece (16th to 12th centuries BC). The language is preserved in inscriptions in Linear B, a script first atteste ...

( 1450 BCE) and Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

( 750ŌĆō400 BCE).

* Hittite ( 1750ŌĆō1200 BCE).

Other Indo-European languages distantly related to Sanskrit include archaic and Classical Latin

Classical Latin is the form of Literary Latin recognized as a Literary language, literary standard language, standard by writers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. It formed parallel to Vulgar Latin around 75 BC out of Old Latin ...

( 600 BCEŌĆō100 CE, Italic languages

The Italic languages form a branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family, whose earliest known members were spoken on the Italian Peninsula in the first millennium BC. The most important of the ancient Italic languages ...

), Gothic (archaic Germanic language

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania, and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, ...

, ), Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

( 200 CE and after), Old Avestan () and Younger Avestan ( 900 BCE).[ For detailed comparison of the languages, see pp. 90ŌĆō126.]Hindu Kush

The Hindu Kush is an mountain range in Central Asia, Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas. It stretches from central and eastern Afghanistan into northwestern Pakistan and far southeastern Tajikistan. The range forms the wester ...

region of northeastern Afghanistan and northwestern Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya ( ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the Earth's highest peaks, including the highest, Mount Everest. More than list of h ...

,Avestan

Avestan ( ) is the liturgical language of Zoroastrianism. It belongs to the Iranian languages, Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family and was First language, originally spoken during the Avestan period, Old ...

and Old Persian

Old Persian is one of two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of the Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native speakers as (I ...

ŌĆō both Iranian languages

The Iranian languages, also called the Iranic languages, are a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages in the Indo-European language family that are spoken natively by the Iranian peoples, predominantly in the Iranian Plateau.

The Iranian langu ...

.satem

Languages of the Indo-European family are classified as either centum languages or satem languages according to how the dorsal consonants (sounds of "K", "G" and "Y" type) of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) developed. An ...

group of the Indo-European languages.

Colonial era scholars familiar with Latin and Greek were struck by the resemblance of the Sanskrit language, both in its vocabulary and grammar, to the classical languages of Europe.

In ''The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World'', Mallory and Adams illustrate the resemblance with the following examples of cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymological ancestor in a common parent language.

Because language change can have radical effects on both the s ...

forms (with the addition of Old English for further comparison):

The correspondences suggest some common root, and historical links between some of the distant major ancient languages of the world.

The Indo-Aryan migrations

The Indo-Aryan migrations were the migrations into the Indian subcontinent of Indo-Aryan peoples, an ethnolinguistic group that spoke Indo-Aryan languages. These are the predominant languages of today's Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal, North India ...

theory explains the common features shared by Sanskrit and other Indo-European languages by proposing that the original speakers of what became Sanskrit arrived in South Asia from a region of common origin, somewhere north-west of the Indus region, during the early 2nd millennium BCE. Evidence for such a theory includes the close relationship between the Indo-Iranian tongues and the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ...

and Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavs, Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic language, Proto- ...

, vocabulary exchange with the non-Indo-European Uralic languages

The Uralic languages ( ), sometimes called the Uralian languages ( ), are spoken predominantly in Europe and North Asia. The Uralic languages with the most native speakers are Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian. Other languages with speakers ab ...

, and the nature of the attested Indo-European words for flora and fauna.

The pre-history of Indo-Aryan languages which preceded Vedic Sanskrit is unclear and various hypotheses place it over a fairly wide limit. According to Thomas Burrow, based on the relationship between various Indo-European languages, the origin of all these languages may possibly be in what is now Central or Eastern Europe, while the Indo-Iranian group possibly arose in Central Russia. The Iranian and Indo-Aryan branches separated quite early. It is the Indo-Aryan branch that moved into eastern Iran and then south into South Asia in the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE. Once in ancient India, the Indo-Aryan language underwent rapid linguistic change and morphed into the Vedic Sanskrit language.

Vedic Sanskrit

The pre-Classical form of Sanskrit is known as ''

The pre-Classical form of Sanskrit is known as ''Vedic Sanskrit

Vedic Sanskrit, also simply referred as the Vedic language, is the most ancient known precursor to Sanskrit, a language in the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan subgroup of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family. It is atteste ...

''. The earliest attested Sanskrit text is the Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' (, , from wikt:ÓżŗÓżÜÓźŹ, ÓżŗÓżÜÓźŹ, "praise" and wikt:ÓżĄÓźćÓż”, ÓżĄÓźćÓż”, "knowledge") is an ancient Indian Miscellany, collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''s┼½ktas''). It is one of the four sacred canoni ...

(), a Hindu scripture from the mid- to late-second millennium BCE. No written records from such an early period survive, if any ever existed, but scholars are generally confident that the oral transmission of the texts is reliable: they are ceremonial literature, where the exact phonetic expression and its preservation were a part of the historic tradition.

However some scholars have suggested that the original Ṛg-veda differed in some fundamental ways in phonology compared to the sole surviving version available to us. In particular that retroflex consonants did not exist as a natural part of the earliest Vedic language, and that these developed in the centuries after the composition had been completed, and as a gradual unconscious process during the oral transmission by generations of reciters.

The primary source for this argument is internal evidence of the text which betrays an instability of the phenomenon of retroflexion, with the same phrases having sandhi-induced retroflexion in some parts but not other. This is taken along with evidence of controversy, for example, in passages of the Aitareya-─Ćraß╣ćyaka (700 BCE), which features a discussion on whether retroflexion is valid in particular cases.

The ß╣Üg-veda is a collection of books, created by multiple authors. These authors represented different generations, and the mandalas 2 to 7 are the oldest while the mandalas 1 and 10 are relatively the youngest. Yet, the Vedic Sanskrit in these books of the ß╣Üg-veda "hardly presents any dialectical diversity", states Louis Renou ŌĆō an Indologist known for his scholarship of the Sanskrit literature and the ß╣Üg-veda in particular. According to Renou, this implies that the Vedic Sanskrit language had a "set linguistic pattern" by the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE. Beyond the ß╣Üg-veda, the ancient literature in Vedic Sanskrit that has survived into the modern age include the ''Samaveda'', ''Yajurveda'', ''Atharvaveda'', along with the embedded and layered Vedic texts such as the Brahmana

The Brahmanas (; Sanskrit: , International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration, IAST: ''Br─ühmaß╣ćam'') are Vedas, Vedic ┼øruti works attached to the Samhitas (hymns and mantras) of the Rigveda, Rig, Samaveda, Sama, Yajurveda, Yajur, and Athar ...

s, Aranyaka

The ''Aranyakas'' (; ; IAST: ') are a part of the ancient Indian Vedas concerned with the meaning of ritual sacrifice, composed in about 700 BC. They typically represent the later sections of the Vedas, and are one of many layers of Vedic text ...

s, and the early Upanishad

The Upanishads (; , , ) are late Vedic and post-Vedic Sanskrit texts that "document the transition from the archaic ritualism of the Veda into new religious ideas and institutions" and the emergence of the central religious concepts of Hind ...

s. These Vedic documents reflect the dialects of Sanskrit found in the various parts of the northwestern, northern, and eastern Indian subcontinent.

According to Michael Witzel, Vedic Sanskrit was a spoken language of the semi-nomadic Aryan

''Aryan'' (), or ''Arya'' (borrowed from Sanskrit ''─ürya''), Oxford English Dictionary Online 2024, s.v. ''Aryan'' (adj. & n.); ''Arya'' (n.)''.'' is a term originating from the ethno-cultural self-designation of the Indo-Iranians. It stood ...

s. The Vedic Sanskrit language or a closely related Indo-European variant was recognized beyond ancient India as evidenced by the "Mitanni

Mitanni (ŌĆō1260 BC), earlier called ßĖ¬abigalbat in old Babylonian texts, ; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat in Assyrian records, or in Ancient Egypt, Egyptian texts, was a Hurrian language, Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria (region), Syria an ...

Treaty" between the ancient Hittite and Mitanni

Mitanni (ŌĆō1260 BC), earlier called ßĖ¬abigalbat in old Babylonian texts, ; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat in Assyrian records, or in Ancient Egypt, Egyptian texts, was a Hurrian language, Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria (region), Syria an ...

people, carved into a rock, in a region that now includes parts of Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to SyriaŌĆōTurkey border, the north, Iraq to IraqŌĆōSyria border, t ...

and Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of T├╝rkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

.Varuna

Varuna (; , ) is a Hindu god. He is one of the earliest deities in pantheon, whose role underwent a significant transformation from the Vedic to the Puranic periods. In the early Vedic era, Varuna is seen as the god-sovereign, ruling the sky ...

, Mitra

''Mitra'' (Proto-Indo-Iranian language, Proto-Indo-Iranian: wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-Iranian/mitr├Īs, ''*mitr├Īs'') is the name of an Indo-Iranians#Religion, Indo-Iranian divinity that predates the Rigveda, Rigvedic Mitra (Hindu god), Mitr├Ī ...

, Indra

Indra (; ) is the Hindu god of weather, considered the king of the Deva (Hinduism), Devas and Svarga in Hinduism. He is associated with the sky, lightning, weather, thunder, storms, rains, river flows, and war. volumes

Indra is the m ...

, and Nasatya found in the earliest layers of the Vedic literature.Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism ( ), also called Mazdayasn─ü () or Beh-d─½n (), is an Iranian religion centred on the Avesta and the teachings of Zarathushtra Spitama, who is more commonly referred to by the Greek translation, Zoroaster ( ). Among the wo ...

''Gathas'' and Homer's ''Iliad'' and ''Odyssey''.simile

A simile () is a type of figure of speech that directly ''compares'' two things. Similes are often contrasted with metaphors, where similes necessarily compare two things using words such as "like", "as", while metaphors often create an implicit c ...

s in the Ṛg-veda, the Old Avestan ''Gathas'' lack simile entirely, and it is rare in the later version of the language. The Homerian Greek, like Ṛg-vedic Sanskrit, deploys simile extensively, but they are structurally very different.

Classical Sanskrit

The early Vedic form of the Sanskrit language was far less homogenous compared to the Classical Sanskrit as defined by grammarians by about the mid-1st millennium BCE. According to Richard GombrichŌĆöan Indologist and a scholar of Sanskrit, P─üli and Buddhist StudiesŌĆöthe archaic Vedic Sanskrit found in the ''Rigveda'' had already evolved in the Vedic period, as evidenced in the later Vedic literature. Gombrich posits that the language in the early Upanishads of Hinduism and the late Vedic literature approaches Classical Sanskrit, while the archaic Vedic Sanskrit had by the

The early Vedic form of the Sanskrit language was far less homogenous compared to the Classical Sanskrit as defined by grammarians by about the mid-1st millennium BCE. According to Richard GombrichŌĆöan Indologist and a scholar of Sanskrit, P─üli and Buddhist StudiesŌĆöthe archaic Vedic Sanskrit found in the ''Rigveda'' had already evolved in the Vedic period, as evidenced in the later Vedic literature. Gombrich posits that the language in the early Upanishads of Hinduism and the late Vedic literature approaches Classical Sanskrit, while the archaic Vedic Sanskrit had by the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha (),*

*

*

was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism. According to Buddhist legends, he was ...

's time become unintelligible to all except ancient Indian sages.[Fortson, ┬¦10.26.] P─üß╣ćini cites ten scholars on the phonological and grammatical aspects of the Sanskrit language before him, as well as the variants in the usage of Sanskrit in different regions of India. The ten Vedic scholars he quotes are ─Ćpi┼øali, Ka┼øyapa, G─ürgya, G─ülava, Cakravarmaß╣ća, Bh─üradv─üja, ┼Ü─ükaß╣Ł─üyana, ┼Ü─ükalya, Senaka and Sphoß╣Ł─üyana.

In the , language is observed in a manner that has no parallel among Greek or Latin grammarians. P─üß╣ćini's grammar, according to Renou and Filliozat, is a classic that defines the linguistic expression and sets the standard for the Sanskrit language. P─üß╣ćini made use of a technical metalanguage consisting of a syntax, morphology and lexicon. This metalanguage is organised according to a series of meta-rules, some of which are explicitly stated while others can be deduced. Despite differences in the analysis from that of modern linguistics, P─üß╣ćini's work has been found valuable and the most advanced analysis of linguistics until the twentieth century.

Sanskrit and Prakrit languages

The earliest known use of the word (Sanskrit), in the context of a speech or language, is found in verses 5.28.17ŌĆō19 of the ''Ramayana''.

The earliest known use of the word (Sanskrit), in the context of a speech or language, is found in verses 5.28.17ŌĆō19 of the ''Ramayana''.[ Outside the learned sphere of written Classical Sanskrit, vernacular colloquial dialects (]Prakrit

Prakrit ( ) is a group of vernacular classical Middle Indo-Aryan languages that were used in the Indian subcontinent from around the 5th century BCE to the 12th century CE. The term Prakrit is usually applied to the middle period of Middle Ind ...

s) continued to evolve. Sanskrit co-existed with numerous other Prakrit languages of ancient India. The Prakrit languages of India also have ancient roots and some Sanskrit scholars have called these , literally 'spoiled'. The Vedic literature includes words whose phonetic equivalent are not found in other Indo-European languages but which are found in the regional Prakrit languages, which makes it likely that the interaction, the sharing of words and ideas began early in the Indian history. As the Indian thought diversified and challenged earlier beliefs of Hinduism, particularly in the form of Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

and Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion whose three main pillars are nonviolence (), asceticism (), and a rejection of all simplistic and one-sided views of truth and reality (). Jainism traces its s ...

, the Prakrit languages such as Pali

P─üli (, IAST: p─ül╠żi) is a Classical languages of India, classical Middle Indo-Aryan languages, Middle Indo-Aryan language of the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pali Canon, P─üli Can ...

in Theravada

''Therav─üda'' (; 'School of the Elders'; ) is Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school's adherents, termed ''Therav─üdins'' (anglicized from Pali ''therav─üd─½''), have preserved their version of the Buddha's teaching or ''Dharma (Buddhi ...

Buddhism and Ardhamagadhi in Jainism competed with Sanskrit in the ancient times.[ The Indian tradition states that the ]Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha (),*

*

*

was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism. According to Buddhist legends, he was ...

and the Mahavira

Mahavira (Devanagari: Óż«Óż╣ÓżŠÓżĄÓźĆÓż░, ), also known as Vardhamana (Devanagari: ÓżĄÓż░ÓźŹÓż¦Óż«ÓżŠÓż©, ), was the 24th ''Tirthankara'' (Supreme Preacher and Ford Maker) of Jainism. Although the dates and most historical details of his lif ...

preferred the Prakrit language so that everyone could understand it. However, scholars such as Dundas have questioned this hypothesis. They state that there is no evidence for this and whatever evidence is available suggests that by the start of the common era, hardly anybody other than learned monks had the capacity to understand the old Prakrit languages such as Ardhamagadhi.[

A section of European scholars state that Sanskrit was never a spoken language.]oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

that preserved the vast number of Sanskrit manuscripts from ancient India. The textual evidence in the works of Yaksa, Panini, and Patanajali affirms that Classical Sanskrit in their era was a spoken language () used by the cultured and educated. Some ''sutra

''Sutra'' ()Monier Williams, ''Sanskrit English Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, Entry fo''sutra'' page 1241 in Indian literary traditions refers to an aphorism or a collection of aphorisms in the form of a manual or, more broadly, a ...

s'' expound upon the variant forms of spoken Sanskrit versus written Sanskrit.[ Chinese Buddhist pilgrim ]Xuanzang

Xuanzang (; ; 6 April 6025 February 664), born Chen Hui or Chen Yi (), also known by his Sanskrit Dharma name Mokß╣Żadeva, was a 7th-century Chinese Bhikkhu, Buddhist monk, scholar, traveller, and translator. He is known for the epoch-making ...

mentioned in his memoir that official philosophical debates in India were held in Sanskrit, not in the vernacular language of that region.[

According to Sanskrit linguist professor Madhav Deshpande, Sanskrit was a spoken language in a colloquial form by the mid-1st millennium BCE which coexisted with a more formal, grammatically correct form of literary Sanskrit. This, states Deshpande, is true for modern languages where colloquial incorrect approximations and dialects of a language are spoken and understood, along with more "refined, sophisticated and grammatically accurate" forms of the same language being found in the literary works. The Indian tradition, states Winternitz, has favored the learning and the usage of multiple languages from the ancient times. Sanskrit was a spoken language in the educated and the elite classes, but it was also a language that must have been understood in a wider circle of society because the widely popular folk epics and stories such as the '']Ramayana

The ''Ramayana'' (; ), also known as ''Valmiki Ramayana'', as traditionally attributed to Valmiki, is a smriti text (also described as a Sanskrit literature, Sanskrit Indian epic poetry, epic) from ancient India, one of the two important epics ...

'', the ''Mahabharata

The ''Mah─übh─ürata'' ( ; , , ) is one of the two major Sanskrit Indian epic poetry, epics of ancient India revered as Smriti texts in Hinduism, the other being the ''Ramayana, R─üm─üyaß╣ća''. It narrates the events and aftermath of the Kuru ...

'', the ''Bhagavata Purana

The ''Bhagavata Purana'' (; ), also known as the ''Srimad Bhagavatam (Śrīmad Bhāgavatam)'', ''Srimad Bhagavata Mahapurana'' () or simply ''Bhagavata (Bhāgavata)'', is one of Hinduism's eighteen major Puranas (''Mahapuranas'') and one ...

'', the ''Panchatantra

The ''Panchatantra'' ( IAST: Pa├▒catantra, ISO: Pa├▒catantra, , "Five Treatises") is an ancient Indian collection of interrelated animal fables in Sanskrit verse and prose, arranged within a frame story. '' and many other texts are all in the Sanskrit language. The Classical Sanskrit with its exacting grammar was thus the language of the Indian scholars and the educated classes, while others communicated with approximate or ungrammatical variants of it as well as other natural Indian languages. Sanskrit, as the learned language of Ancient India, thus existed alongside the vernacular Prakrits. Many Sanskrit drama

The term Indian classical drama refers to the tradition of dramatic literature and performance in ancient India. The roots of drama in the Indian subcontinent can be traced back to the Rigveda (1200-1500 BCE), which contains a number of hymns in ...

s indicate that the language coexisted with the vernacular Prakrits. The cities of Varanasi

Varanasi (, also Benares, Banaras ) or Kashi, is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic tradition of I ...

, Paithan, Pune

Pune ( ; , ISO 15919, ISO: ), previously spelled in English as Poona (List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1978), is a city in the state of Maharashtra in the Deccan Plateau, Deccan plateau in Western ...

and Kanchipuram

Kanchipuram (International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration, IAST: '; ), also known as Kanjeevaram, is a stand alone city corporation, satellite nodal city of Chennai in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu in the Tondaimandalam region, from ...

were centers of classical Sanskrit learning and public debates until the arrival of the colonial era.

According to Lamotte, Sanskrit became the dominant literary and inscriptional language because of its precision in communication. It was, states Lamotte, an ideal instrument for presenting ideas, and as knowledge in Sanskrit multiplied, so did its spread and influence. Sanskrit was adopted voluntarily as a vehicle of high culture, arts, and profound ideas. Pollock disagrees with Lamotte, but concurs that Sanskrit's influence grew into what he terms a "Sanskrit Cosmopolis" over a region that included all of South Asia and much of southeast Asia. The Sanskrit language cosmopolis thrived beyond India between 300 and 1300 CE.

Dravidian influence on Sanskrit

Rein├Čhl mentions that not only have the Dravidian languages borrowed from Sanskrit vocabulary, but they have also affected Sanskrit on deeper levels of structure, "for instance in the domain of phonology where Indo-Aryan retroflexes have been attributed to Dravidian influence".Old Tamil

Old Tamil is the period of the Tamil language spanning from the 3rd century BCE to the seventh century CE. Prior to Old Tamil, the period of Tamil linguistic development is termed as Proto-Tamil. After the Old Tamil period, Tamil becomes Middl ...

on Sanskrit.

Influence

Sanskrit has been the predominant language of Hindu texts

Hindu texts or Hindu scriptures are manuscripts and voluminous historical literature which are related to any of the diverse traditions within Hinduism. Some of the major Hindus, Hindu texts include the Vedas, the Upanishads, and the Itihasa. ...

encompassing a rich tradition of philosophical

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and religious

Religion is a range of social- cultural systems, including designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relate humanity to supernatural ...

texts, as well as poetry, music, drama

Drama is the specific Mode (literature), mode of fiction Mimesis, represented in performance: a Play (theatre), play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on Radio drama, radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a g ...

, scientific

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, technical and others. It is the predominant language of one of the largest collection of historic manuscripts. The earliest known inscriptions in Sanskrit are from the 1st century BCE, such as the Ayodhya Inscription of Dhana and Ghosundi-Hathibada (Chittorgarh).

Though developed and nurtured by scholars of orthodox schools of Hinduism, Sanskrit has been the language for some of the key literary works and theology of heterodox schools of Indian philosophies such as Buddhism and Jainism.[ They speculated on the role of language, the ontological status of painting word-images through sound, and the need for rules so that it can serve as a means for a community of speakers, separated by geography or time, to share and understand profound ideas from each other.][Madhav Deshpande (2010), ''Language and Testimony in Classical Indian Philosophy'', Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]

Source Link

These speculations became particularly important to the M─½m─üß╣ās─ü

''M─½m─üß╣üs─ü'' (Sanskrit: Óż«ÓźĆÓż«ÓżŠÓżéÓżĖÓżŠ; IAST: M─½m─üß╣ās─ü) is a Sanskrit word that means "reflection" or "critical investigation" and thus refers to a tradition of contemplation which reflected on the meanings of certain Vedic tex ...

and the Nyaya

Ny─üya (Sanskrit: Óż©ÓźŹÓż»ÓżŠÓż»Óżā, IAST: ny─üyaßĖź), literally meaning "justice", "rules", "method" or "judgment", is one of the six orthodox (─Ćstika) schools of Hindu philosophy. Ny─üya's most significant contributions to Indian philosophy ...

schools of Hindu philosophy, and later to Vedanta and Mahayana Buddhism, states Frits Staal

Johan Frederik "Frits" Staal (3 November 1930 ŌĆō 19 February 2012) was the department founder and Emeritus Professor of Philosophy and South/Southeast Asian Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. Staal specialized in the study of Ved ...

ŌĆöa scholar of Linguistics with a focus on Indian philosophies and Sanskrit.Nagarjuna

N─üg─ürjuna (Sanskrit: Óż©ÓżŠÓżŚÓżŠÓż░ÓźŹÓż£ÓźüÓż©, ''N─üg─ürjuna''; ) was an Indian monk and Mahayana, Mah─üy─üna Buddhist Philosophy, philosopher of the Madhyamaka (Centrism, Middle Way) school. He is widely considered one of the most importa ...

(200 CE), used Classical Sanskrit as the language for his texts. According to Renou, Sanskrit had a limited role in the Theravada tradition (formerly known as the Hinayana) but the Prakrit works that have survived are of doubtful authenticity. Some of the canonical fragments of the early Buddhist traditions, discovered in the 20th century, suggest the early Buddhist traditions used an imperfect and reasonably good Sanskrit, sometimes with a Pali syntax, states Renou. The Mah─üs─üß╣āghika

The Mah─üs─üß╣āghika (Brahmi script, Brahmi: æĆ½æĆ│æĆĖæĆ▓æĆĖæĆüæĆ¢æĆ║æĆō, "of the Great Sangha (Buddhism), Sangha", ) was a major division (nik─üya) of the early Buddhist schools in India. They were one of the two original communities th ...

and Mahavastu, in their late Hinayana forms, used hybrid Sanskrit for their literature. Sanskrit was also the language of some of the oldest surviving, authoritative and much followed philosophical works of Jainism such as the ''Tattvartha Sutra'' by Umaswati.

The Sanskrit language has been one of the major means for the transmission of knowledge and ideas in Asian history. Indian texts in Sanskrit were already in China by 402 CE, carried by the influential Buddhist pilgrim Faxian

Faxian (337ŌĆō), formerly romanization of Chinese, romanized as Fa-hien and Fa-hsien, was a Han Chinese, Chinese Chinese Buddhism, Buddhist bhikkhu, monk and translator who traveled on foot from Eastern Jin dynasty, Jin China to medieval India t ...

who translated them into Chinese by 418 CE. Xuanzang

Xuanzang (; ; 6 April 6025 February 664), born Chen Hui or Chen Yi (), also known by his Sanskrit Dharma name Mokß╣Żadeva, was a 7th-century Chinese Bhikkhu, Buddhist monk, scholar, traveller, and translator. He is known for the epoch-making ...

, another Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, learnt Sanskrit in India and carried 657 Sanskrit texts to China in the 7th century where he established a major center of learning and language translation under the patronage of Emperor Taizong. By the early 1st millennium CE, Sanskrit had spread Buddhist and Hindu ideas to Southeast Asia, parts of the East AsiaDalai Lama

The Dalai Lama (, ; ) is the head of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. The term is part of the full title "Holiness Knowing Everything Vajradhara Dalai Lama" (Õ£Ż Ķ»åõĖĆÕłć ńō”ķĮÉÕ░öĶŠŠÕ¢ć ĶŠŠĶĄ¢ Õ¢ćÕśø) given by Altan Khan, the first Shu ...

, the Sanskrit language is a parent language that is at the foundation of many modern languages of India and the one that promoted Indian thought to other distant countries. In Tibetan Buddhism, states the Dalai Lama, Sanskrit language has been a revered one and called ''legjar lhai-ka'' or "elegant language of the gods". It has been the means of transmitting the "profound wisdom of Buddhist philosophy" to Tibet.

The Sanskrit language created a pan-Indo-Aryan accessibility to information and knowledge in the ancient and medieval times, in contrast to the Prakrit languages which were understood just regionally. It created a cultural bond across the subcontinent. As local languages and dialects evolved and diversified, Sanskrit served as the common language. It connected scholars from distant parts of South Asia such as Tamil Nadu and Kashmir, states Deshpande, as well as those from different fields of studies, though there must have been differences in its pronunciation given the first language of the respective speakers. The Sanskrit language brought Indo-Aryan speaking people together, particularly its elite scholars. Some of these scholars of Indian history regionally produced vernacularized Sanskrit to reach wider audiences, as evidenced by texts discovered in Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Maharashtra. Once the audience became familiar with the easier to understand vernacularized version of Sanskrit, those interested could graduate from colloquial Sanskrit to the more advanced Classical Sanskrit. Rituals and the rites-of-passage ceremonies have been and continue to be the other occasions where a wide spectrum of people hear Sanskrit, and occasionally join in to speak some Sanskrit words such as .

Classical Sanskrit is the standard

The Sanskrit language created a pan-Indo-Aryan accessibility to information and knowledge in the ancient and medieval times, in contrast to the Prakrit languages which were understood just regionally. It created a cultural bond across the subcontinent. As local languages and dialects evolved and diversified, Sanskrit served as the common language. It connected scholars from distant parts of South Asia such as Tamil Nadu and Kashmir, states Deshpande, as well as those from different fields of studies, though there must have been differences in its pronunciation given the first language of the respective speakers. The Sanskrit language brought Indo-Aryan speaking people together, particularly its elite scholars. Some of these scholars of Indian history regionally produced vernacularized Sanskrit to reach wider audiences, as evidenced by texts discovered in Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Maharashtra. Once the audience became familiar with the easier to understand vernacularized version of Sanskrit, those interested could graduate from colloquial Sanskrit to the more advanced Classical Sanskrit. Rituals and the rites-of-passage ceremonies have been and continue to be the other occasions where a wide spectrum of people hear Sanskrit, and occasionally join in to speak some Sanskrit words such as .

Classical Sanskrit is the standard register

Register or registration may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Music

* Register (music), the relative "height" or range of a note, melody, part, instrument, etc.

* ''Register'', a 2017 album by Travis Miller

* Registration (organ), ...

as laid out in the grammar of , around the fourth century BCE.Greater India

Greater India, also known as the Indian cultural sphere, or the Indic world, is an area composed of several countries and regions in South Asia, East Asia and Southeast Asia that were historically influenced by Indian culture, which itself ...

is akin to that of Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

and Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

in Europe. Sanskrit has significantly influenced most modern languages of the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

, particularly the languages of the northern, western, central and eastern Indian subcontinent.

Decline

The decline of Sanskrit began in the 13th century.[ This coincides with the beginning of ]Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

ic invasions of South Asia to create, and thereafter expand the Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

rule in the form of Sultanates, and later the Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an Early modern period, early modern empire in South Asia. At its peak, the empire stretched from the outer fringes of the Indus River Basin in the west, northern Afghanistan in the northwest, and Kashmir in the north, to ...

. Sheldon Pollock characterises the decline of Sanskrit as a long-term "cultural, social, and political change". He dismisses the idea that Sanskrit declined due to "struggle with barbarous invaders", and emphasises factors such as the increasing attractiveness of vernacular language for literary expression.

With the fall of Kashmir

Kashmir ( or ) is the Northwestern Indian subcontinent, northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term ''Kashmir'' denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir P ...

around the 13th century, a premier center of Sanskrit literary creativity, Sanskrit literature there disappeared, perhaps in the "fires that periodically engulfed the capital of Kashmir" or the "Mongol invasion of 1320" states Pollock. The Sanskrit literature which was once widely disseminated out of the northwest regions of the subcontinent, stopped after the 12th century. As Hindu kingdoms fell in the eastern and the South India, such as the great Vijayanagara Empire

The Vijayanagara Empire, also known as the Karnata Kingdom, was a late medieval Hinduism, Hindu empire that ruled much of southern India. It was established in 1336 by the brothers Harihara I and Bukka Raya I of the Sangama dynasty, belongi ...

, so did Sanskrit. There were exceptions and short periods of imperial support for Sanskrit, mostly concentrated during the reign of the tolerant Mughal emperor Akbar

Akbar (Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar, ŌĆō ), popularly known as Akbar the Great, was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Humayun, under a regent, Bairam Khan, who helped the young emperor expa ...

.Maratha Empire

The Maratha Empire, also referred to as the Maratha Confederacy, was an early modern India, early modern polity in the Indian subcontinent. It comprised the realms of the Peshwa and four major independent List of Maratha dynasties and states, Ma ...

, reversed the process, by re-adopting Sanskrit and re-asserting their socio-linguistic identity.dead

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sho ...

". After the 12th century, the Sanskrit literary works were reduced to "reinscription and restatements" of ideas already explored, and any creativity was restricted to hymns and verses. This contrasted with the previous 1,500 years when "great experiments in moral and aesthetic imagination" marked the Indian scholarship using Classical Sanskrit, states Pollock.

Scholars maintain that the Sanskrit language did not die, but rather only declined. Jurgen Hanneder disagrees with Pollock, finding his arguments elegant but "often arbitrary". According to Hanneder, a decline or regional absence of creative and innovative literature constitutes a negative evidence to Pollock's hypothesis, but it is not positive evidence. A closer look at Sanskrit in the Indian history after the 12th century suggests that Sanskrit survived despite the odds. According to Hanneder,

Modern Indo-Aryan languages

The relationship of Sanskrit to the Prakrit languages, particularly the modern form of Indian languages, is complex and spans about 3,500 years, states Colin MasicaŌĆöa linguist specializing in South Asian languages. A part of the difficulty is the lack of sufficient textual, archaeological and epigraphical evidence for the ancient Prakrit languages with rare exceptions such as Pali, leading to a tendency toward anachronistic

An anachronism (from the Greek , 'against' and , 'time') is a chronological inconsistency in some arrangement, especially a juxtaposition of people, events, objects, language terms and customs from different time periods. The most common typ ...

errors. Sanskrit and Prakrit languages may be divided into Old Indo-Aryan (1500 BCE ŌĆō 600 BCE), Middle Indo-Aryan (600 BCE ŌĆō 1000 CE) and New Indo-Aryan (1000 CE ŌĆō present), each can further be subdivided into early, middle or second, and late evolutionary substages.

Vedic Sanskrit belongs to the early Old Indo-Aryan stage, while Classical Sanskrit to the later Old Indo-Aryan stage. The evidence for Prakrits such as Pali (Theravada Buddhism) and Ardhamagadhi (Jainism), along with Magadhi, Maharashtri, Sinhala, Sauraseni and Niya (Gandhari), emerge in the Middle Indo-Aryan stage in two versionsŌĆöarchaic and more formalizedŌĆöthat may be placed in early and middle substages of the 600 BCE ŌĆō 1000 CE period. Two literary Indo-Aryan languages can be traced to the late Middle Indo-Aryan stage and these are ''Apabhramsa'' and ''Elu'' (a literary form of Sinhalese). Numerous North, Central, Eastern and Western Indian languages, such as Hindi, Gujarati, Sindhi, Punjabi, Kashmiri, Nepali, Braj, Awadhi, Bengali, Assamese, Oriya, Marathi, and others belong to the New Indo-Aryan stage.

There is an extensive overlap in the vocabulary, phonetics and other aspects of these New Indo-Aryan languages with Sanskrit, but it is neither universal nor identical across the languages. They likely emerged from a synthesis of the ancient Sanskrit language traditions and an admixture of various regional dialects. Each language has some unique and regionally creative aspects, with unclear origins. Prakrit languages do have a grammatical structure, but like Vedic Sanskrit, it is far less rigorous than Classical Sanskrit. While the roots of all Prakrit languages may be in Vedic Sanskrit and ultimately the Proto-Indo-Aryan language, their structural details vary from Classical Sanskrit.Indo-Aryan languages

The Indo-Aryan languages, or sometimes Indic languages, are a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages in the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family. As of 2024, there are more than 1.5 billion speakers, primarily concentrated east ...

ŌĆō such as Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, and Punjabi ŌĆō are descendants of the Sanskrit language. Sanskrit, states Burjor Avari, can be described as "the mother language of almost all the languages of north India".

Geographic distribution

The Sanskrit language's historic presence is attested across a wide geography beyond South Asia. Inscriptions and literary evidence suggests that Sanskrit language was already being adopted in Southeast Asia and Central Asia in the 1st millennium CE, through monks, religious pilgrims and merchants.

South Asia has been the geographic range of the largest collection of the ancient and pre-18th-century Sanskrit manuscripts and inscriptions.[ Beyond ancient India, significant collections of Sanskrit manuscripts and inscriptions have been found in China (particularly the Tibetan monasteries),]Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

, Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

, Laos

Laos, officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic (LPDR), is the only landlocked country in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by Myanmar and China to the northwest, Vietnam to the east, Cambodia to the southeast, and Thailand to the west and ...

, Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

, Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

, and Malaysia

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia. Featuring the Tanjung Piai, southernmost point of continental Eurasia, it is a federation, federal constitutional monarchy consisting of States and federal territories of Malaysia, 13 states and thre ...

. Sanskrit inscriptions, manuscripts or its remnants, including some of the oldest known Sanskrit written texts, have been discovered in dry high deserts and mountainous terrains such as in Nepal,[ Afghanistan, Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan. Some Sanskrit texts and inscriptions have also been discovered in Korea and Japan.

]

Official status

In India, Sanskrit is among the 22 official languages of India in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution.Uttarakhand

Uttarakhand (, ), also known as Uttaranchal ( ; List of renamed places in India, the official name until 2007), is a States and union territories of India, state in North India, northern India. The state is bordered by Himachal Pradesh to the n ...

became the first state in India to make Sanskrit its second official language. In 2019, Himachal Pradesh

Himachal Pradesh (; Sanskrit: ''him─üc─ül pr─üdes;'' "Snow-laden Mountain Province") is a States and union territories of India, state in the northern part of India. Situated in the Western Himalayas, it is one of the thirteen Indian Himalayan ...

made Sanskrit its second official language, becoming the second state in India to do so.

Phonology

Sanskrit shares many Proto-Indo-European phonological features, although it features a larger inventory of distinct phonemes. The consonantal system is the same, though it systematically enlarged the inventory of distinct sounds. For example, Sanskrit added a voiceless aspirated "t╩░", to the voiceless "t", voiced "d" and voiced aspirated "d╩░" found in PIE languages.

The most significant and distinctive phonological development in Sanskrit is vowel merger. The short ''*e'', ''*o'' and ''*a'', all merge as ''a'' (Óżģ) in Sanskrit, while long ''*─ō'', ''*┼Ź'' and ''*─ü'', all merge as long ''─ü'' (Óżå). Compare Sanskrit ''n─üman'' to Latin ''n┼Źmen''. These mergers occurred very early and significantly affected Sanskrit's morphological system. Some phonological developments in it mirror those in other PIE languages. For example, the labiovelars merged with the plain velars as in other satem languages. The secondary palatalization of the resulting segments is more thorough and systematic within Sanskrit. For example, unlike the loss of the morphological clarity from vowel contraction that is found in early Greek and related southeast European languages, Sanskrit deployed ''*y'', ''*w'', and ''*s'' intervocalically to provide morphological clarity.

Vowels

The cardinal vowels (''svaras'') ''a'' (Óżģ), ''i'' (Óżć), and ''u'' (Óżē) distinguish length in Sanskrit. The short ''a'' (Óżģ) in Sanskrit is a closer vowel than ─ü, equivalent to schwa. The mid vowels ─ō (ÓżÅ) and ┼Ź (Óżō) in Sanskrit are monophthongizations of the Indo-Iranian diphthongs ''*ai'' and ''*au''. They are inherently long, though often transcribed ''e'' and ''o'' without the diacritic. The vocalic liquid ''r╠ź'' in Sanskrit is a merger of PIE ''*r╠ź'' and ''*l╠ź''. The long ''r╠ź'' is an innovation and it is used in a few analogically generated morphological categories.

According to Masica, Sanskrit has four traditional semivowels, with which were classed, "for morphophonemic reasons, the liquids: y, r, l, and v; that is, as y and v were the non-syllabics corresponding to i, u, so were r, l in relation to r╠ź and l╠ź". The northwestern, the central and the eastern Sanskrit dialects have had a historic confusion between "r" and "l". The Paninian system that followed the central dialect preserved the distinction, likely out of reverence for the Vedic Sanskrit that distinguished the "r" and "l". However, the northwestern dialect only had "r", while the eastern dialect probably only had "l", states Masica. Thus literary works from different parts of ancient India appear inconsistent in their use of "r" and "l", resulting in doublets that are occasionally semantically differentiated.

The nasal 'ß╣ā' is optionally the corresponding nasal consonant before plosives (aß╣ā + k = aß╣ģk or am k) and an 'm'-sound before r, s, ┼ø, ß╣Ż, and h. Before y, l, v, it can cause nasalaization and gemination (am + y = aß╗╣y or am y).

Consonants

Sanskrit possesses a symmetric consonantal phoneme structure based on how the sound is articulated, though the actual usage of these sounds conceals the lack of parallelism in the apparent symmetry possibly from historical changes within the language.

* Sanskrit has a series of retroflex stops originating as conditioned alternants of dentals.

* ''jh'' is a marginal phoneme in Sanskrit, hence its phonology is more difficult to reconstruct; it was more commonly employed in the Middle Indo-Aryan languages as a result of phonological processes resulting in the phoneme.

* The palatal nasal is a conditioned variant of n occurring next to palatal obstruents.

* The ''anusvara'' that Sanskrit deploys is a conditioned alternant of post-vocalic nasals, under certain sandhi conditions.

* The ''visarga'' is a word-final or morpheme-final conditioned alternant of s and r under certain sandhi conditions.

* The voiceless aspirated series is also an innovation in Sanskrit but is rarer than the other three series.

* While the Sanskrit language organizes sounds for expression beyond those found in the PIE language, it retained many features found in the Iranian and Balto-Slavic languages. An example of a similar process in all three is the retroflex sibilant ʂ being the automatic product of dental s following i, u, r, and k.

Phonological alternations, sandhi rules

Sanskrit deploys extensive phonological alternations on different linguistic levels through ''sandhi'' rules (literally, the rules of "putting together, union, connection, alliance"), similar to the English alteration of "going to" as ''gonna''. The Sanskrit language accepts such alterations within it, but offers formal rules for the ''sandhi'' of any two words next to each other in the same sentence or linking two sentences. The external ''sandhi'' rules state that similar short vowels coalesce into a single long vowel, while dissimilar vowels form glides or undergo diphthongization. Among the consonants, most external ''sandhi'' rules recommend regressive assimilation for clarity when they are voiced. These rules ordinarily apply at compound seams and morpheme boundaries. In Vedic Sanskrit, the external ''sandhi'' rules are more variable than in Classical Sanskrit.

Vedic Pitch Accent

Vedic Sanskrit included a three-way pitch accent system of ''ud─ütta'' (raised), ''anud─ütta'' (not-raised or grave), and ''svarita'' (sounded) which were high, low and falling pitches respectively. Each word generally had one ''ud─ütta'' accent except for certain compound words. The classical language ultimately lost this system, but it was preserved in Vedic texts and phonological treatises. Traditional chanting renders the ''ud─ütta'' as an unaccented mid-tone and the first half of the ''svarita'' as higher than an ''ud─ütta''; the other half is rendered the same level of that of an ''ud─ütta.''

Morphology

The basis of Sanskrit morphology is the root, states Jamison, "a morpheme bearing lexical meaning". The verbal and nominal stems of Sanskrit words are derived from this root through the phonological vowel-gradation processes, the addition of affixes, verbal and nominal stems. It then adds an ending to establish the grammatical and syntactic identity of the stem. According to Jamison, the "three major formal elements of the morphology are (i) root, (ii) affix, and (iii) ending; and they are roughly responsible for (i) lexical meaning, (ii) derivation, and (iii) inflection respectively".

A Sanskrit word has the following canonical structure:

The root structure has certain phonological constraints. Two of the most important constraints of a "root" is that it does not end in a short "a" (Óżģ) and that it is monosyllabic. In contrast, the affixes and endings commonly do. The affixes in Sanskrit are almost always suffixes, with exceptions such as the augment "a-" added as prefix to past tense verb forms and the "-na/n-" infix in single verbal present class, states Jamison.

Sanskrit verbs

Sanskrit has, together with Ancient Greek verbs , Ancient Greek, kept most intact among descendants Proto-Indo-European verbs, the elaborate verbal morphology of Proto-Indo-European. Sanskrit verbs thus have an inflection system for different co ...

have the following canonical structure:

According to Ruppel, verbs in Sanskrit express the same information as other Indo-European languages such as English. Sanskrit verbs describe an action or occurrence or state, its embedded morphology informs as to "who is doing it" (person or persons), "when it is done" (tense) and "how it is done" (mood, voice). The Indo-European languages differ in the detail. For example, the Sanskrit language attaches the affixes and ending to the verb root, while the English language adds small independent words before the verb. In Sanskrit, these elements co-exist within the word.

Both verbs and nouns in Sanskrit are either thematic or athematic, states Jamison. ''Guna'' (strengthened) forms in the active singular regularly alternate in athematic verbs. The finite verbs of Classical Sanskrit have the following grammatical categories: person, number, voice, tense-aspect, and mood. According to Jamison, a portmanteau morpheme generally expresses the person-number-voice in Sanskrit, and sometimes also the ending or only the ending. The mood of the word is embedded in the affix.

These elements of word architecture are the typical building blocks in Classical Sanskrit, but in Vedic Sanskrit these elements fluctuate and are unclear. For example, in the ''Rigveda'' preverbs regularly occur in tmesis, states Jamison, which means they are "separated from the finite verb". This indecisiveness is likely linked to Vedic Sanskrit's attempt to incorporate accent. With nonfinite forms of the verb and with nominal derivatives thereof, states Jamison, "preverbs show much clearer univerbation in Vedic, both by position and by accent, and by Classical Sanskrit, tmesis is no longer possible even with finite forms".

While roots are typical in Sanskrit, some words do not follow the canonical structure. A few forms lack both inflection and root. Many words are inflected (and can enter into derivation) but lack a recognizable root. Examples from the basic vocabulary include kinship terms such as ''m─ütar-'' (mother), ''nas-'' (nose), ''┼øvan-'' (dog). According to Jamison, pronouns and some words outside the semantic categories also lack roots, as do the numerals. Similarly, the Sanskrit language is flexible enough to not mandate inflection.

The Sanskrit words can contain more than one affix that interact with each other. Affixes in Sanskrit can be athematic as well as thematic, according to Jamison. Athematic affixes can be alternating. Sanskrit deploys eight cases, namely nominative, accusative, instrumental, dative, ablative, genitive, locative, vocative.

Stems, that is "root + affix", appear in two categories in Sanskrit: vowel stems and consonant stems. Unlike some Indo-European languages such as Latin or Greek, according to Jamison, "Sanskrit has no closed set of conventionally denoted noun declensions". Sanskrit includes a fairly large set of stem-types. The linguistic interaction of the roots, the phonological segments, lexical items and the grammar for the Classical Sanskrit consist of four ''Paninian'' components. These, states Paul Kiparsky, are the ''Astadhyaayi'', a comprehensive system of 4,000 grammatical rules, of which a small set are frequently used; ''Sivasutras'', an inventory of ''anubandhas'' (markers) that partition phonological segments for efficient abbreviations through the ''pratyharas'' technique; ''Dhatupatha'', a list of 2,000 verbal roots classified by their morphology and syntactic properties using diacritic markers, a structure that guides its writing systems; and, the ''Ganapatha'', an inventory of word groups, classes of lexical systems.[

Sanskrit morphology is generally studied in two broad fundamental categories: the nominal forms and the verbal forms. These differ in the types of endings and what these endings mark in the grammatical context. Pronouns and nouns share the same grammatical categories, though they may differ in inflection. Verb-based adjectives and participles are not formally distinct from nouns. Adverbs are typically frozen case forms of adjectives, states Jamison, and "nonfinite verbal forms such as infinitives and gerunds also clearly show frozen nominal case endings".

]

Verbal forms

The Sanskrit language includes five tenses: present, future, past imperfect, past aorist

Aorist ( ; abbreviated ) verb forms usually express perfective aspect and refer to past events, similar to a preterite. Ancient Greek grammar had the aorist form, and the grammars of other Indo-European languages and languages influenced by the ...

and past perfect. It outlines three types of voices: active, passive and the middle. The middle is also referred to as the mediopassive, or more formally in Sanskrit as (word for another) and (word for oneself).

The paradigm for the tense-aspect system in Sanskrit is the three-way contrast between the "present", the "aorist" and the "perfect" architecture. Vedic Sanskrit is more elaborate and had several additional tenses. For example, the ''Rigveda'' includes perfect and a marginal pluperfect. Classical Sanskrit simplifies the "present" system down to two tenses, the perfect and the imperfect, while the "aorist" stems retain the aorist tense and the "perfect" stems retain the perfect and marginal pluperfect. The classical version of the language has elaborate rules for both voice and the tense-aspect system to emphasize clarity, and this is more elaborate than in other Indo-European languages. The evolution of these systems can be seen from the earliest layers of the Vedic literature to the late Vedic literature.

The three verbal moods in Sanskrit are indicative, potential (optative), and imperative.

Nominal forms

Sanskrit recognizes three numbersŌĆösingular, dual, and plural. The dual is a fully functioning category, used beyond naturally paired objects such as hands or eyes, extending to any collection of two. The elliptical dual is notable in the Vedic Sanskrit, according to Jamison, where a noun in the dual signals a paired opposition. Illustrations include ''dy─üv─ü'' (literally, "the two heavens" for heaven-and-earth), ''m─ütar─ü'' (literally, "the two mothers" for mother-and-father). A verb may be singular, dual or plural, while the person recognized in the language are forms of "I", "you", "he/she/it", "we" and "they".

There are three persons in Sanskrit: first, second and third. Sanskrit uses the 3├Ś3 grid formed by the three numbers and the three persons parameters as the paradigm and the basic building block of its verbal system.

The Sanskrit language incorporates three genders: feminine, masculine and neuter. All nouns have inherent gender. With some exceptions, personal pronouns have no gender. Exceptions include demonstrative and anaphoric pronouns. Derivation of a word is used to express the feminine. Two most common derivations come from feminine-forming suffixes, the ''-─ü-'' (Óżå, R─üdh─ü) and ''-─½-'' (Óżł, Rukmin─½). The masculine and neuter are much simpler, and the difference between them is primarily inflectional. Similar affixes for the feminine are found in many Indo-European languages, states Burrow, suggesting links of the Sanskrit to its PIE heritage.

Pronouns in Sanskrit include the personal pronouns of the first and second persons, unmarked for gender, and a larger number of gender-distinguishing pronouns and adjectives. Examples of the former include ''ah├Īm'' (first singular), ''vay├Īm'' (first plural) and ''y┼½y├Īm'' (second plural). The latter can be demonstrative, deictic or anaphoric. Both the Vedic and Classical Sanskrit share the ''s├Ī/t├Īm'' pronominal stem, and this is the closest element to a third person pronoun and an article in the Sanskrit language, states Jamison.

Prosody, metre

The Sanskrit language formally incorporates poetic metres.[ By the late Vedic era, this developed into a field of study; it was central to the composition of the Hindu literature, including the later Vedic texts. This study of Sanskrit prosody is called '' chandas'', and is considered one of the six ]Vedanga

The Vedanga ( ', "limb of the Veda-s"; plural form: ÓżĄÓźćÓż”ÓżŠÓżÖÓźŹÓżŚÓżŠÓż©Óż┐ ') are six auxiliary disciplines of Vedic studies that developed in Vedic and post-Vedic times.James Lochtefeld (2002), "Vedanga" in The Illustrated Encyclopedia o ...

s, or limbs of Vedic studies.[James Lochtefeld, James (2002). "Chandas". In ''The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism''. Vol. 1: A-M. Rosen. . p. 140]

Sanskrit metres include those based on a fixed number of syllables per verse, and those based on fixed number of morae per verse.

Writing system

The early history of writing Sanskrit and other languages in ancient India is a problematic topic despite a century of scholarship, states Richard Salomon ŌĆō an epigraphist and Indologist specializing in Sanskrit and Pali literature. The earliest possible script from South Asia is from the Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation, was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form from 2600 BCE ...

(3rd/2nd millennium BCE), but this script ŌĆō if it is a script ŌĆō remains undeciphered. If any scripts existed in the Vedic period, they have not survived. Scholars generally accept that Sanskrit was spoken in an oral society, and that an oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

preserved the extensive Vedic and Classical Sanskrit literature. Other scholars such as Jack Goody argue that the Vedic Sanskrit texts are not the product of an oral society, basing this view by comparing inconsistencies in the transmitted versions of literature from various oral societies such as the Greek (Greco-Sanskrit), Serbian, and other cultures. This minority of scholars argue that the Vedic literature is too consistent and vast to have been composed and transmitted orally across generations, without having been written down.Lalitavistara Sūtra

The ''Lalitavistara Sūtra'' is a Sanskrit Mahayana sutras, Mahayana Buddhist sutra that tells the story of Gautama Buddha from the time of his descent from Tushita until his first sermon in the Deer Park at Sarnath near Varanasi. The term ''La ...