Centacare on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Catholic Church in Australia is part of the worldwide

The Catholic Church in Australia is part of the worldwide

Since the 1980s, Catholicism has been largest Christian denomination in Australia, constituting around one-quarter of the overall population and becoming slightly larger than the

Since the 1980s, Catholicism has been largest Christian denomination in Australia, constituting around one-quarter of the overall population and becoming slightly larger than the

http://www.abs.gov.au Before the

The

The

NSW Blue Plaques Program Mother Mary Xavier established a new hospital at Adelaide in 1900 and

Section 116 of the Australian Constitution of 1901 to some extent prevented the new federal parliament from interfering with

Section 116 of the Australian Constitution of 1901 to some extent prevented the new federal parliament from interfering with

In 2001, in Rome, Pope John Paul II apologised to Aboriginal and other indigenous people in Oceania for past injustices by the church: "Aware of the shameful injustices done to indigenous peoples in Oceania, the Synod Fathers apologised unreservedly for the part played in these by members of the church, especially where children were forcibly separated from their families." Church leaders in Australia called on the Australian government to offer a similar apology.

In 2001,

In 2001, in Rome, Pope John Paul II apologised to Aboriginal and other indigenous people in Oceania for past injustices by the church: "Aware of the shameful injustices done to indigenous peoples in Oceania, the Synod Fathers apologised unreservedly for the part played in these by members of the church, especially where children were forcibly separated from their families." Church leaders in Australia called on the Australian government to offer a similar apology.

In 2001,

By 1833, there were around ten Catholic schools in the Australian colonies. Today one in five Australian students attend Catholic schools. There are over 1700 Catholic schools in Australia with more than 750,000 students enrolled, employing almost 60,000 teachers. Mary MacKillop was a 19th-century Australian

By 1833, there were around ten Catholic schools in the Australian colonies. Today one in five Australian students attend Catholic schools. There are over 1700 Catholic schools in Australia with more than 750,000 students enrolled, employing almost 60,000 teachers. Mary MacKillop was a 19th-century Australian

Church leaders have often involved themselves in political issues in areas they consider relevant to Christian teachings. In early Colonial times, Catholicism was restricted but

Church leaders have often involved themselves in political issues in areas they consider relevant to Christian teachings. In early Colonial times, Catholicism was restricted but  ; Australian Catholic politicians

Australia elected its first Catholic prime minister,

; Australian Catholic politicians

Australia elected its first Catholic prime minister,

File:StMarysCathedral b.jpg,

The body of literature produced by Australian Catholics is extensive. During colonial times, the

The body of literature produced by Australian Catholics is extensive. During colonial times, the

Catholic Church in Australia's official website

Australian Catholic Bishops Conference official website

Australian Catholic Historical Society

Timeline of Australian Catholic History

Australian Catholic Biographies

Website of Patrick O'Farrell, historian of Catholic Australia

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Catholic Church in Australia

The Catholic Church in Australia is part of the worldwide

The Catholic Church in Australia is part of the worldwide Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

under the spiritual and administrative leadership of the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

. From origins as a suppressed, mainly Irish minority in early colonial times, the church has grown to be the largest Christian denomination in Australia, with a culturally diverse membership of around 5,075,907 people, representing about 20% of the overall population of Australia according to the 2021 ABS Census data.

The church is the largest non-government provider of welfare and education services in Australia. Catholic Social Services Australia Catholic Social Services Australia (CSSA) is a body that seeks to advance the social service ministry of the Catholic Church and consists of member welfare organisations. It was established as a commission of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conferen ...

aids some 450,000 people annually, while the St Vincent de Paul Society

The Society of Saint Vincent de Paul (SVP or SVdP or SSVP) is an international voluntary organization in the Catholic Church, founded in 1833 for the service of the poor. Started by Frédéric Ozanam and Emmanuel-Joseph Bailly de Surcy and nam ...

's 40,000 members form the largest volunteer welfare network in the country. In 2016, the church had some 760,000 students in more than 1,700 schools.

The church in Australia has five provinces: Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney. It has 35 dioceses, comprising geographic areas as well as the military diocese and dioceses for the Chaldean

Chaldean (also Chaldaean or Chaldee) may refer to:

Language

* an old name for the Aramaic language, particularly Biblical Aramaic. See Chaldean Catholic Church#Terminology, Chaldean misnomer

* Suret, a modern Aramaic language spoken by Chaldean C ...

, Maronite

Maronites (; ) are a Syriac Christianity, Syriac Christian ethnoreligious group native to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant (particularly Lebanon) whose members belong to the Maronite Church. The largest concentration has traditionally re ...

, Melkite

The term Melkite (), also written Melchite, refers to various Eastern Christian churches of the Byzantine Rite and their members originating in West Asia. The term comes from the common Central Semitic root ''m-l-k'', meaning "royal", referrin ...

, Syro-Malabar (St Thomas Christians), and Ukrainian Rite

Rite may refer to:

Religion

* Ritual, an established ceremonious act

* Rite (Christianity), sacred rituals in the Christian religion

* Ritual family, Christian liturgical traditions; often also called ''liturgical rites''

* Catholic particular ch ...

s. The national assembly of bishops is the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference

The Australian Catholic Bishops’ Conference (ACBC) is the national episcopal conference of the Catholic bishops of Australia and is the instrumentality used by the Australian Catholic bishops to act nationally and address issues of national ...

(ACBC). There are a further 175 Catholic religious order

In the Catholic Church, a religious order is a community of consecrated life with members that profess solemn vows. They are classed as a type of Religious institute (Catholic), religious institute.

Subcategories of religious orders are:

* can ...

s operating in Australia, affiliated under Catholic Religious Australia. One Australian has been recognised as a saint by the Catholic Church: Mary MacKillop

Mary Helen MacKillop RSJ ( in religion Mary of the Cross; 15 January 1842 – 8 August 1909) was an Australian religious sister. She was born in Melbourne but is best known for her activities in South Australia. Together with Fr Julian Teniso ...

, who co-founded the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart

The Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart, often called the Josephites or Brown Joeys, are a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Mary MacKillop (1842–1909). Members of the congregation use the postnominal initials RSJ (Religious Sis ...

("Josephite") religious institute in the 19th century.

Demographics

Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

and Uniting churches combined. Up until the , adherents had been recorded as growing both numerically and as a percentage of the population; however, the 2016 census found a fall in both overall numbers and the percentage of Catholics as a proportion of Australian residents, with 5,291,839 Australian Catholics (around 22.6% of the population) in 2016, down from 5,439,257 in the (25.3% of the population). This was repeated again in 2021, with the numbers dropping to 5,075,907 people, representing about 20% of the overall population of Australia according to the 2021 ABS Census data.

Until the , Australia's most populous Christian church was the Anglican Church of Australia

The Anglican Church of Australia, originally known as the Church of England in Australia and Tasmania, is a Christian church in Australia and an autonomous church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. In 2016, responding to a peer-reviewed study ...

. Since then, Catholics have outnumbered Anglicans by an increasing margin. The change is partly explained by changes in immigration patterns.Religion in Australia: 2016 Census Data Summaryhttp://www.abs.gov.au Before the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the majority of immigrants to Australia came from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and most Catholic immigrants came from Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

. After the war, Australia's immigration diversified, and more than 6.5 million migrants arrived in the following 60 years, including more than a million Catholics from Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

, the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

.

At the 2016 Census, the ancestries with which Australian Catholics most identified were English (1.49 million), Australian (1.12 million), Irish (577,000), Italian (567,000) and Filipino (181,000).

Despite a growing population of Catholics, weekly Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

attendance has declined from an estimated 74% in the mid-1950s to around 14% in 2006.

There are seven archdiocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associated ...

s and 32 diocese

In Ecclesiastical polity, church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided Roman province, prov ...

s, with an estimated 3,000 priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

s and 9,000 men and women in institutes of consecrated life

An institute of consecrated life is an association of faithful in the Catholic Church canonically erected by competent church authorities to enable men or women who publicly profess the evangelical counsels by religious vows or other sacred bon ...

and societies of apostolic life

A society of apostolic life is a group of men or women within the Catholic Church who have come together for a specific purpose and live fraternally. It is regarded as a form of Consecrated life, consecrated (or "religious") life.

This typ ...

, including six dioceses that cover the whole country: one each for those who belong to the Chaldean, Maronite, Melkite, Syro-Malabar and Ukrainian rites and one for those serving in the Australian Defence Force

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) is the Armed forces, military organisation responsible for the defence of Australia and its national interests. It consists of three branches: the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), Australian Army and the Royal Aus ...

s. There is also a personal ordinariate

A personal ordinariate for former Anglicans, shortened as personal ordinariate or Anglican ordinariate,"Bishop Stephen Lopes of the Anglican Ordinariate of the Chair of St Peter..." is a canonical structure within the Catholic Church establis ...

for former Anglicans, which has a similar status to a diocese.

History

Arrival and suppression

Among the first Catholics known to have sighted Australia were the crew of a Spanish expedition of 1605–6. In 1606, the expedition's leader, Pedro Fernandez de Quiros landed in theNew Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium () and named after the Hebrides in Scotland, was the colonial name for the island group in the South Pacific Ocean that is now Vanuatu. Native people had inhabited the islands for three th ...

, believing it to be the fabled southern continent. He named the land Austrialis del Espiritu Santo ''Southern Land of the Holy Spirit''. Later that year, his deputy Luís Vaz de Torres

Luís Vaz de Torres ( Galician and Portuguese), or Luis Váez de Torres in the Spanish spelling (born 1565; 1607), was a 16th- and 17th-century maritime explorer and captain of a Spanish expedition noted for the first recorded European navi ...

sailed through the Torres Strait

The Torres Strait (), also known as Zenadh Kes ( Kalaw Lagaw Ya#Phonology 2, �zen̪ad̪ kes, is a strait between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, ...

between Australia and New Guinea.

The permanent presence of Catholicism in Australia came rather with the arrival of the First Fleet

The First Fleet were eleven British ships which transported a group of settlers to mainland Australia, marking the beginning of the History of Australia (1788–1850), European colonisation of Australia. It consisted of two Royal Navy vessel ...

of British convict ships at Sydney in 1788. One-tenth of all the convicts who came to Australia on the First Fleet were Catholic, and at least half of them were born in Ireland. A small proportion of British marines were also Catholic.

Just as the British were setting up the new colony, French captain Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse

Commodore (rank), Commodore Jean François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse (; 23 August 1741 – ) was a French Navy officer and explorer. Having enlisted in the Navy at the age of 15, he had a successful career and in 1785 was appointed to lea ...

arrived off Botany Bay

Botany Bay (Dharawal language, Dharawal: ''Kamay'') is an open oceanic embayment, located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point a ...

with two ships.David Hill, ''1788: The Brutal Truth of the First Fleet'' La Pérouse was 6 weeks in Botany Bay, where the French, besides other things, held Catholic Masses. The crew conducted the first Catholic burial, that of Father Louis Receveur

Claude-Francois Joseph Louis Receveur O.F.M. Conv., (1757 – 17 February 1788) was a French friar priest, naturalist and astronomer who sailed with Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse.

Receveur was also considered a skilled botanist, ...

, a Franciscan friar who died while the ships were at anchor at Botany Bay.

Some of the Irish convicts had been transported to Australia for political crimes or social rebellion in Ireland, so the authorities were suspicious of Catholicism for the first three decades of settlement.

Catholic convicts were compelled to attend Church of England services and their children and orphans were raised by the authorities as Anglicans. The first Catholic priests arrived in Australia as convicts in 1800 – James Harold, James Dixon

James Dixon (August 5, 1814 – March 27, 1873) was a United States representative and Senator from Connecticut.

Biography

Dixon, son of William & Mary (Field) Dixon, was born August 5, 1814, in Enfield, Connecticut, Dixon pursued preparat ...

and Peter O'Neill, who had been convicted for "complicity" in the Irish 1798 Rebellion

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 (; Ulster-Scots: ''The Turn out'', ''The Hurries'', 1798 Rebellion) was a popular insurrection against the British Crown in what was then the separate, but subordinate, Kingdom of Ireland. The main organising force ...

. Fr Dixon was conditionally emancipated and permitted to celebrate Mass. On 15 May 1803, in vestments made from curtains and with a chalice made of tin, he conducted the first Catholic Mass in "New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

". The Irish-led Castle Hill Rebellion

The Castle Hill convict rebellion was a convict rebellion in Castle Hill, Sydney, then part of the British colony of New South Wales. Led by veterans of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the poorly armed insurgents confronted the colonial forces of ...

of 1804 alarmed the British authorities and Dixon's permission to celebrate Mass was revoked. Fr Jeremiah O' Flinn, an Irish Cistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

monk, was appointed as Prefect Apostolic

An apostolic prefect or prefect apostolic is a priest who heads what is known as an apostolic prefecture, a 'pre-diocesan' missionary jurisdiction where the Catholic Church is not yet sufficiently developed to have it made a diocese. Although it ...

of New Holland and set out from Britain for the colony, uninvited. Watched by authorities, Flynn secretly performed priestly duties before being arrested and deported to London. Reaction to the affair in Britain led to two further priests being allowed to travel to the colony in 1820 – John Joseph Therry

John Therry (1790 - 25 May 1864) was an Irish Roman Catholic priest in Sydney, Australia.

Early life

John Therry was born in Cork and was privately educated at St Patrick's College in Carlow. In 1815 he was ordained as a priest. He did parish ...

and Philip Conolly. The foundation stone for the first St Mary's Church, was laid on 29 October 1821 by Governor Lachlan Macquarie

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major General Lachlan Macquarie, Companion of the Order of the Bath, CB (; ; 31 January 1762 – 1 July 1824) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Scotland. Macquarie served as the fifth Gove ...

.

The absence of a Catholic mission in Australia before 1818 reflected the legal disabilities of Catholics in Britain and the difficult position of Ireland within the British Empire. The government therefore endorsed the English Benedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

monks to lead the early church in the colony. The Reverend William Bernard Ullathorne

William Bernard Ullathorne (7 May 180621 March 1889) was an English prelate who held high offices in the Roman Catholic Church during the nineteenth century.

Early life

Ullathorne was born in Pocklington, East Riding of Yorkshire, the eldest o ...

(1806–1889) was instrumental in influencing Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI (; ; born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari; 18 September 1765 – 1 June 1846) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1831 to his death in June 1846. He had adopted the name Mauro upon enteri ...

to establish the hierarchy in Australia. Ullathorne was in Australia from 1833 to 1836 as vicar-general to Bishop William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditiona ...

of Mauritius

Mauritius, officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island country in the Indian Ocean, about off the southeastern coast of East Africa, east of Madagascar. It includes the main island (also called Mauritius), as well as Rodrigues, Ag ...

, whose jurisdiction extended over the Australian missions.

Emancipation and growth

The

The Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

was disestablished in the colony of New South Wales by the ''Church Act of 1836

The Church Act, also known as the Church Building Act, was a 1836 law in the Colony of New South Wales. It was drafted by John Plunkett and enacted by the Governor, Sir Richard Bourke. It was subtitled "An Act to promote the building of Churches ...

'', which also provided equal funding of Protestant and Catholic churches. Drafted by the Catholic attorney-general John Plunkett

John Hubert Plunkett (June 1802 – 9 May 1869) was Attorney-General of New South Wales, an appointed member of the Legislative Council 1836–41, 1843–56, 1857–58 and 1861–69. He was also elected as a member of the Legislative Asse ...

, the act established legal equality for Anglicans, Catholics and Presbyterians and was later extended to Methodists. Nevertheless, social attitudes were slow to change. A laywoman, Caroline Chisholm

Caroline Chisholm ( ; born Caroline Jones; 30 May 1808 – 25 March 1877) was an English humanitarian known mostly for her support of immigrant female and family welfare in Australia. She is commemorated on 16 May in the Calendar of saints (Ch ...

(1808–1877), faced discouragements and anti-Catholic feeling when she sought to establish a migrant women's shelter. She worked for women's welfare in the colonies in the 1840s, though her humanitarian efforts later won her fame in England and great influence in achieving support for families in the colony.

The church's most prominent early leader was John Bede Polding

John Bede Polding OSB (18 November 179416 March 1877) was an English Benedictine monk and the first Roman Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, Australia.

Early life

Polding was born in Liverpool, England, on 18 November 1794. His father was of Du ...

, a Benedictine monk

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, they ...

who was Sydney's first bishop (and then archbishop) from 1835 to 1877. Polding requested a community of nuns be sent to the colony and five Irish Sisters of Charity

Many religious communities have the term Sisters of Charity in their name. Some ''Sisters of Charity'' communities refer to the Vincentian tradition alone, or in America to the tradition of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton (whose sisters are also of ...

arrived in 1838. While tensions arose between the English Benedictine hierarchy and the Irish, Ignatian-tradition religious institute from the start, the sisters set about pastoral care in a women's prison and began visiting hospitals and schools and establishing employment for convict women. In 1847, two sisters transferred to Hobart

Hobart ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the island state of Tasmania, Australia. Located in Tasmania's south-east on the estuary of the River Derwent, it is the southernmost capital city in Australia. Despite containing nearly hal ...

and established a school. The sisters went on to establish hospitals in four of the eastern states, beginning with St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney

St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney is a leading tertiary referral hospital and research facility located in Darlinghurst, Sydney. Though funded and integrated into the New South Wales state public health system, it is operated by St Vincent's Hea ...

, in 1857 as a free hospital for all people, but especially for the poor.

At Polding's request, the Christian Brothers arrived in Sydney in 1843 to assist in schools. Again jurisdictional tensions arose and the brothers returned to Ireland. In 1857, Polding founded an Australian religious institute

In the Catholic Church, a religious institute is "a society in which members, according to proper law, pronounce public religious vows, vows, either perpetual or temporary which are to be renewed, however, when the period of time has elapsed, a ...

in the Benedictine tradition – the Sisters of the Good Samaritan

The Congregation of the Sisters of the Good Samaritan, colloquially known as the "Good Sams", is a Roman Catholic congregation of religious women commenced by Bede Polding, OSB, Australia’s first Catholic bishop, in Sydney in 1857. The congrega ...

– to work in education and social work. While Polding was in office, construction began on the ambitious Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an Architectural style, architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half ...

designs for St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne

The Cathedral Church and Minor Basilica of Saint Patrick (colloquially St Patrick's Cathedral) is the cathedral church of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Melbourne in Victoria, Australia, and seat of its archbishop, currently Peter Comensol ...

, and the final St Mary's Cathedral in Sydney.

In 1845, Polding established the Australian Holy Catholic Guild of Saints Mary and Joseph. Some parishes have memorials dedicated to deceased members and friends. One such is at St Patrick's Boorowa, New South Wales. Examples of the Guild's reporting to members and election of office bearers can be seen in the Freeman's Journal. In 1848, they met under St Patrick's Church at the intersection of George and Hunter streets and had 250 members at that time. Records of the association, from 1845 to 1996, are held at the NSW State Library and this includes a copy of the constitution of the guild.

Establishing themselves first at Sevenhill

The Australian monastic town of Sevenhill is in the Clare Valley of South Australia, approximately 130 km north of Adelaide. The town was founded by members of the Jesuit order in 1850. The name, bestowed by Austrian Jesuit priest Aloysius ...

, in the newly established colony of South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

in 1848, the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

were the first religious order of priests to enter and establish houses in South Australia, Victoria, Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

and the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (abbreviated as NT; known formally as the Northern Territory of Australia and informally as the Territory) is an states and territories of Australia, Australian internal territory in the central and central-northern regi ...

– Austrian Jesuits established themselves in the south and north and Irish in the east. The goldrush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, Gr ...

saw an increase in the population and prosperity of the colonies and called for an increase in the number of episcopal see

An episcopal see is the area of a bishop's ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

Phrases concerning actions occurring within or outside an episcopal see are indicative of the geographical significance of the term, making it synonymous with ''diocese'' ...

s. When gold was discovered in late 1851, there were an estimated 9,000 Catholics in the Colony of Victoria, increasing to 100,000 by the time the Jesuits arrived 14 years later. While the Austrian priests traversed the Outback on horseback to found missions and schools, the Irish priests arrived in the east in 1860 and had by 1880 established the major schools of Xavier College

Xavier College is a Roman Catholic, day and boarding school predominantly for boys, founded in 1872 by the Society of Jesus, with its main campus located in Kew, an eastern suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Classes started in 1878.

The ...

in Melbourne and in Sydney St Aloysius' College and Saint Ignatius' College, Riverview – which each survive to the present.

During 1869 and 1870, some Australian based clergy attended the first Vatican Council in Rome.

Despite anti-Irish lobbying by English Catholic bishops and the British government, Irish cleric Patrick Francis Moran

Patrick Francis Moran (16 September 183016 August 1911) was a prelate of the Catholic Church and the third Archbishop of Sydney and the first cardinal appointed from Australia.

Early life

Moran was born at Leighlinbridge, County Carlow, Irel ...

won the favour of Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the Ap ...

and was appointed Archbishop of Sydney in 1884, arriving in New South Wales on 8 September. A prominent figure in Australian Catholic history, he became Australia's first cardinal the following year after being summoned back to Rome, and presided over Plenary Councils of Australasia in 1885, 1895 and 1905 which laid the foundations for Church structure in the 20th century. The Australian colonies had hitherto relied heavily on immigrant clergy. In 1889, Moran founded St Patrick's College, Manly

St Patrick's Seminary, Manly is a heritage-listed former residence of the Archbishop of Sydney and Roman Catholic Church seminary at 151 Darley Road, Manly, Northern Beaches Council, New South Wales, Australia. The property was also known as ...

, intended to provide priests for all the colonies. Moran believed that Catholics' political and civil rights were threatened in Australia and, in 1896, saw deliberate discrimination in a situation where "no office of first, or even second, rate importance is held by a Catholic".

In Rome in 1884, Moran had met the Venerable Mary Potter and invited her to send a group of her newly established Little Company of Mary sisters to Australia in order to establish a local congregation. Six pioneering sisters arrived in Sydney in November 1885, commencing work caring for the sick and dying. Establishing a convent at Lewishman, they had nearly fifty members within just five years. In 1889 they opened a small hospital at Lewisham. Under the leadership of Mother Mary Xavier Lynch from 1899, the hospital would grow to be one of Sydney's leading general hospitals and nursing schools.About Little Company of Mary SistersNSW Blue Plaques Program Mother Mary Xavier established a new hospital at Adelaide in 1900 and

Wagga Wagga

Wagga Wagga (; informally called Wagga) is a major regional city in the Riverina region of New South Wales, Australia. Straddling the Murrumbidgee River, with an urban population of more than 57,003 as of 2021, it is an important agricultural, m ...

in 1926, and despatched sisters to found hospitals in New Zealand and South Africa. In 1922 she became the order's first provincial of Australasia, and is remembered as one of Australia's most noted hospital and nursing administrators.

The Catholic Church also became involved in mission work among the Aboriginal people of Australia during the 19th century as Europeans came to control much of the continent. According to Aboriginal anthropologist Kathleen Butler-McIlwraith, there were many occasions when the Catholic Church attempted to advocate for Aboriginal rights, but the missionaries were also "functionaries of the Protection

Protection is any measure taken to guard something against damage caused by outside forces. Protection can be provided to physical objects, including organisms, to systems, and to intangible things like civil and political rights. Although ...

and Assimilation policies" of the government and so "directly contributed to the current disadvantage experienced by Indigenous Australians". The missionaries themselves argued that they protected children from dysfunctional aspects of indigenous culture.

With the withdrawal of state aid for church schools around 1880, the Catholic Church, unlike other Australian churches, put great energy and resources into creating a comprehensive alternative system of education. It was largely staffed by sisters, brothers and priests of religious institutes, such as the Christian Brothers (who had returned to Australia in 1868); the Sisters of Mercy

The Sisters of Mercy is a religious institute for women in the Catholic Church. It was founded in 1831 in Dublin, Ireland, by Catherine McAuley. In 2019, the institute had about 6,200 Religious sister, sisters worldwide, organized into a number ...

(who had arrived in Perth in 1846); Marist Brothers

The Marist Brothers of the Schools, commonly known as simply the Marist Brothers, is an international community of Catholic Church, Catholic religious institute of Religious brother, brothers. In 1817, Marcellin Champagnat, a Marist priest from Fr ...

, who came from France in 1872; and the Sisters of St Joseph, founded in Australia by Mary MacKillop and Fr Julian Tenison Woods

Julian Edmund Tenison-WoodsThough common in modern references, his surname was not hyphenated in contemporary newspaper reports, his signature, or his headstone. (15 November 18327 October 1889), commonly referred to as Father Woods, was an Eng ...

in 1867. MacKillop travelled throughout Australasia

Australasia is a subregion of Oceania, comprising Australia, New Zealand (overlapping with Polynesia), and sometimes including New Guinea and surrounding islands (overlapping with Melanesia). The term is used in a number of different context ...

and established schools, convents and charitable institutions but came into conflict with those bishops who preferred diocesan control of the institute rather than central control from Adelaide by the Josephite religious institute. MacKillop administered the Josephites as a national religious institute at a time when Australia was divided among individually governed colonies. She is today the most revered of Australian Catholics, beatified

Beatification (from Latin , "blessed" and , "to make") is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their name. ''Beati'' is the ...

by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

in 1995 and canonised

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of sai ...

by Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until resignation of Pope Benedict XVI, his resignation on 28 Februar ...

in 2010. Catholic schools flourished in Australia and by 1900 there were 115 Christian Brothers teaching in Australia. By 1910 there were 5000 religious sister

A religious sister (abbreviated: Sr.) in the Catholic Church is a woman who has taken public vows in a religious institute dedicated to apostolic works, as distinguished from a nun who lives a cloistered monastic life dedicated to prayer and ...

s teaching in schools.

Federation

Section 116 of the Australian Constitution of 1901 to some extent prevented the new federal parliament from interfering with

Section 116 of the Australian Constitution of 1901 to some extent prevented the new federal parliament from interfering with freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

and ensured a separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

throughout Australia. Australia's first Catholic cardinal, Patrick Francis Moran

Patrick Francis Moran (16 September 183016 August 1911) was a prelate of the Catholic Church and the third Archbishop of Sydney and the first cardinal appointed from Australia.

Early life

Moran was born at Leighlinbridge, County Carlow, Irel ...

(1830–1911), had been a proponent of Australian Federation

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia (which also governed what is now the Northern Territory), and Wester ...

but in 1901 he refused to attend the inauguration ceremony of the Commonwealth of Australia because precedence was given to the Church of England. He was criticised in '' The Bulletin'' for speaking against racist immigration laws and he alarmed Catholic conservatives by supporting Trade Unionism

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

and the newly formed Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also known as the Labor Party or simply Labor, is the major Centre-left politics, centre-left List of political parties in Australia, political party in Australia and one of two Major party, major parties in Po ...

.

The Catholic Church was rooted in the working class Irish communities. Moran, the Archbishop of Sydney from 1884 to 1911, believed that Catholicism would flourish with the emergence of the new nation through Federation in 1901, provided that his people rejected "contamination" from foreign influences such as anarchism, socialism, modernism and secularism. Moran distinguished between European socialism as an atheistic movement and those Australians calling themselves "socialists"; he approved of the objectives of the latter while feeling that the European model was not a real danger in Australia. Moran's outlook reflected his wholehearted acceptance of Australian democracy and his belief in the country as different and freer than the old societies from which its people had come. Moran thus welcomed the Labor Party and the Catholic Church stood with it in opposing conscription in the referendums of 1916 and 1917. The hierarchy had close ties to Rome, which encouraged the bishops to support the British Empire and emphasize Marian piety.

Between the wars

Another Irish cleric, ArchbishopDaniel Mannix

Daniel Patrick Mannix (4 March 1864 – 6 November 1963) was an Irish-born Australian Catholic bishop. Mannix was the Archbishop of Melbourne for 46 years and one of the most influential public figures in 20th-century Australia.

Early lif ...

(1864–1963) of Melbourne, was a controversial voice against conscription

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it conti ...

during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and against British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

policy in Ireland. He was also a fervent critic of contraception. In 1920, the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

prevented him landing in his Irish homeland. In the Melbourne St Patrick's day parade of 1920, Archbishop Mannix participated with fourteen Victoria Cross recipients. Yet despite early 20th century sectarian feeling, Australia elected its first Catholic prime minister, James Scullin

James Henry Scullin (18 September 1876 – 28 January 1953) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the ninth prime minister of Australia from 1929 to 1932. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), ...

, of the Australian Labor Party in 1929 – decades before the Protestant majority of the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

would elect John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

as its first Catholic president. His successor, Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Australia, from 1932 until his death in 1939. He held office as the inaugural leader of the United Australia Par ...

, a devout Irish Catholic, split from Labor to form the fiscally conservative United Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four Elections in Australia, federal elections in that time, usually governing Coalition (Australia), in coalition ...

– predecessor to the modern Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia (LP) is the prominent centre-right political party in Australia. It is considered one of the two major parties in Australian politics, the other being the Australian Labor Party (ALP). The Liberal Party was fo ...

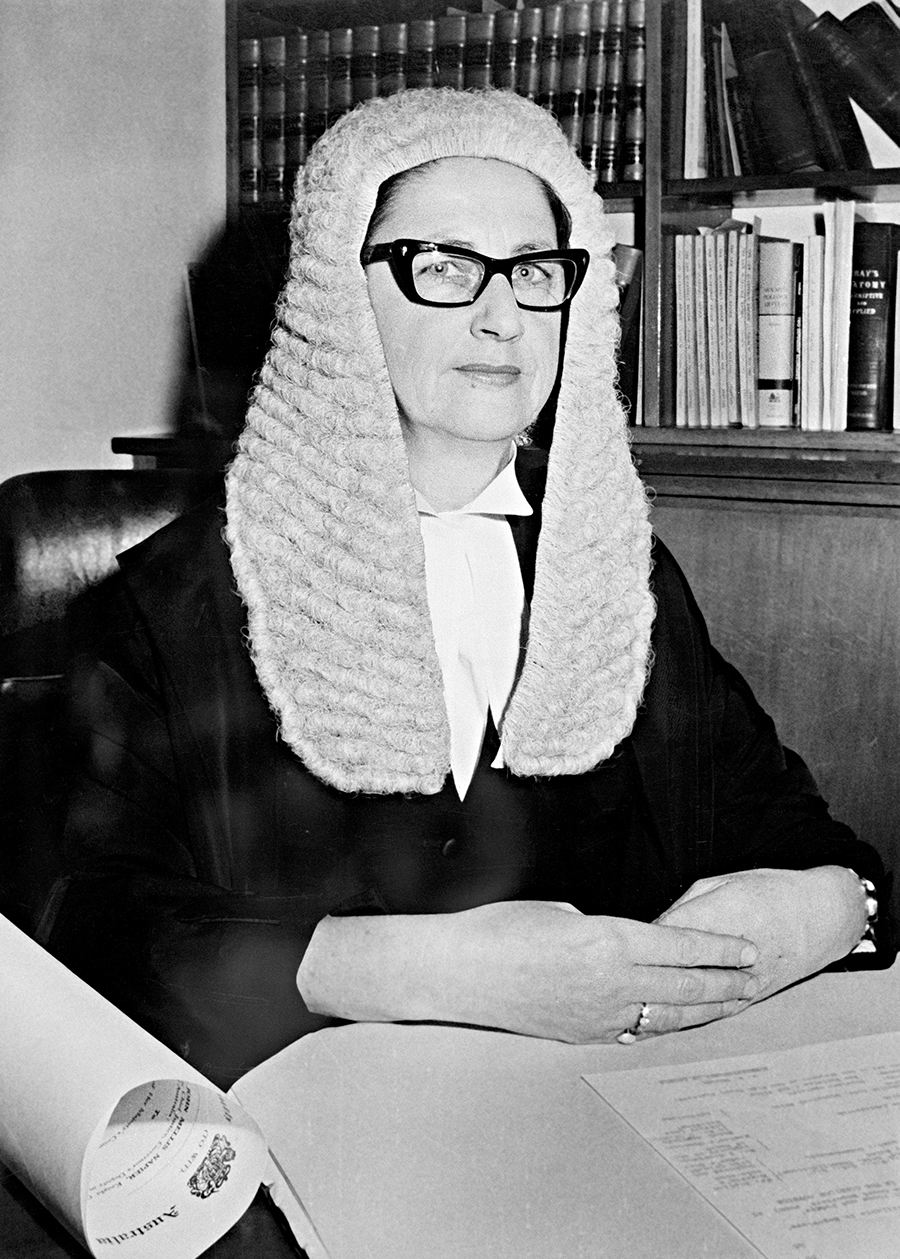

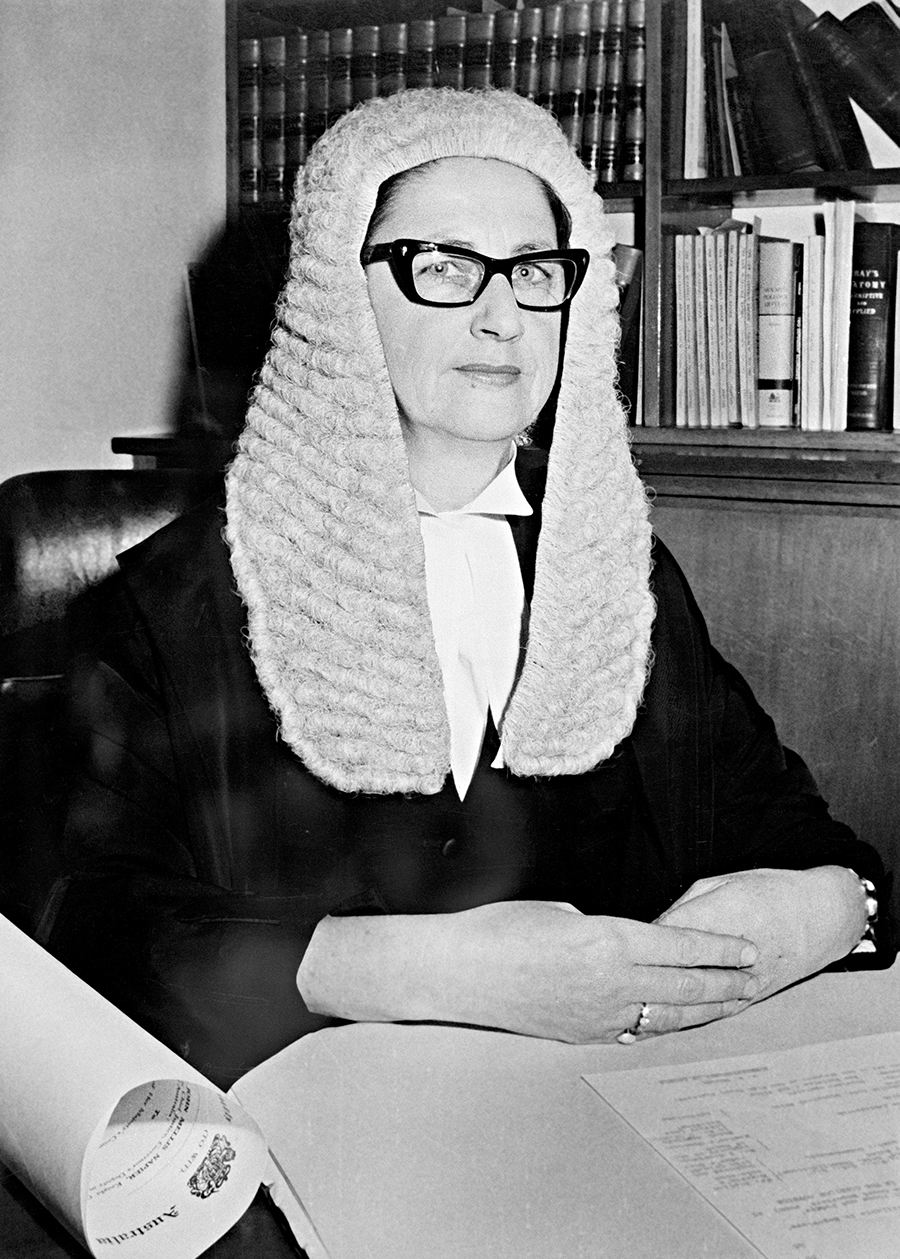

. His wife, Dame Enid Lyons

Dame Enid Muriel Lyons (; 9 July 1897 – 2 September 1981) was an Australian politician. She was notable as the being the first woman to be elected to the House of Representatives and to serve in the federal cabinet. Prior to her own politic ...

, a Catholic convert, became the first female member of the Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Australian Senate, Senate. Its composition and powers are set out in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia.

...

and later first female member of cabinet in the Menzies Government. With the place of Catholics in the British Empire still complicated by the recent Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

and centuries of imperial rivalry with Catholic European nations, as prime minister, Lyons travelled to London in 1935 for the silver jubilee celebrations of King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

George was born during the reign of his pa ...

and faced anti-Catholic demonstrations in Edinburgh, then visited his ancestral homeland of Ireland and also had an audience with the Pope in Rome.

The Australian congregation known as Our Lady's Nurses for the Poor was founded by Melbourne-born mystic Eileen O'Connor

Eileen Rosaline O'Connor (19 February 1892 – 10 January 1921) was an Australian Roman Catholic and the co-founder of the Society of Our Lady's Nurses for the Poor religious order – also known as the Brown Nurses – to provide free nursing se ...

and Fr Ted McGrath

Timothy Edward McGrath (1881–1977) was an Australian Catholic priest and with Eileen O'Connor the founder of Our Lady's Nurses for the Poor religious order.

Early life

McGrath was born in Bungeet near Benalla in north-east Victoria in 1881 t ...

in a rented home at Coogee in 1913. A deeply religious youth, O'Connor had suffered a damaged spine when she was three years old and lived in a wheelchair with a painful disability. McGrath, the parish priest of Coogee, found accommodation for her widowed mother and family and was impressed by her courage. O'Connor told McGrath that she had experienced a visitation from the Virgin Mary, and McGrath shared with her his hope to establish a congregation of nurses to serve the poor. Eventually, a group of seven laywomen gathered around O'Connor and elected her as their first superior. Directed by the largely bed-ridden O'Connor, they visited the sick poor and nursed the frail aged. O'Connor died in 1921 of chronic tuberculosis of the spine and exhaustion. She was 28. Initially a group of laywomen, Our Lady's Nurses for the Poor later formed themselves into a religious community of sisters under vows and their work continues in Sydney, Newcastle and Macquarie Fields. In 2018, Australia's bishops voted to initiate her cause for sainthood and the Holy See granted her the title Servant of God

Servant of God () is a title used in the Catholic Church to indicate that an individual is on the first step toward possible canonization as a saint.

Terminology

The expression ''Servant of God'' appears nine times in the Bible, the first five in ...

.

In October 1916, the Catholic Women's Social Guild (now Catholic Women's League) was formed in Fitzroy, Victoria, and Mary Glowrey

Mary Glowrey JMJ, religious name ''Mary of the Sacred Heart'', (1887–1957) was an Australian born religious sister and educated doctor who spent 37 years in India, where she set up healthcare facilities, services and systems. She is believed t ...

became the inaugural president. Glowrey was one of the first women to study medicine at Melbourne University. She later went to India to become a missionary nun, founding the largest non-government healthcare system in that country. She was accorded the title Servant of God in 2013 and her cause for sainthood is underway.

The Australian Army Chaplains Department was promulgated in 1913, and 86 Catholic chaplains went on to serve in the army during World War One. As well as conducting church parades and religious services, chaplains organised activities to improve the morale and welfare of the troops. Fr John Fahey from Perth was the longest-serving front-line chaplain of the conflict. Assigned to the 11th battalion, he was the first chaplain ashore on Gallipoli, after disregarding orders to stay on the ship.

During the Second World War, the Australian-administered Territory of New Guinea

The Territory of New Guinea was an Australian-administered League of Nations and then United Nations trust territory on the island of New Guinea from 1914 until 1975. In 1949, the Territory and the Territory of Papua were established in an adm ...

was invaded by Japanese forces. Some 333 Martyrs of New Guinea

The Martyrs of New Guinea were Christians including clergy, teachers, and medical staff serving in New Guinea who were executed during the Japanese invasion during World War II in 1942 and 1943. A total of 333 church workers including Papuans and ...

are remembered from all denominations during WW2, including 197 Catholics. On Rabaul

Rabaul () is a township in the East New Britain province of Papua New Guinea, on the island of New Britain. It lies about to the east of the island of New Guinea. Rabaul was the provincial capital and most important settlement in the province ...

, Australians and Europeans found refuge at the Vunapope Catholic Mission, until the Japanese overwhelmed the island and took them prisoner in 1942. The local Bishop Leo Scharmach, a Pole, convinced the Japanese that he was German and to spare the internees. A group of indigenous Daughters of Mary Immaculate (FMI Sisters) then refused to give up their faith or abandon the Australians and are credited with keeping hundreds of internees alive for three and half years by growing food and delivering it to them over gruelling distances. Some of the Sisters were tortured by the Japanese and gave evidence during war crimes trials after the war. Indigenous Rabaul man Peter To Rot found himself in charge of the mission at Rakunai after the internment of the Europeans. He took on their work of teaching the faith, presiding over baptisms, prayer and marriages and caring for the sick and POWs. When the Japanese outlawed these practises, he continued them in secret, was exposed by a collaborator and sent to a labour camp where he was executed. Pope John Paul II declared him a martyr in 1993 and beatified him in 1995.

Post-war immigration: A more diverse church

Until about 1950, the Catholic Church in Australia was overwhelmingly Irish in its ethos. Most Catholics were descendants of Irish immigrants and the church was mostly led by Irish-born priests and bishops. A number of rural areas had high proportions of Irish and a strongly Catholic culture. From 1950 the ethnic composition of the church began to change, with the assimilation of Irish Australians and the arrival of Eastern EuropeanDisplaced Persons

Forced displacement (also forced migration or forced relocation) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR defines 'forced displaceme ...

from 1948 and more than one million Catholics from countries such as Italy, Malta, the Netherlands, Germany, Croatia and Hungary, and later Filipinos, Vietnamese, Lebanese and Poles around the 1980s. There are now also strong Chinese, Korean and Hispanic Catholic communities.

For a long time, Irish-Australians had a close political association with the Labor Party. The changing ethnic composition of Australian Catholicism and shifting political allegiances of Australian Catholics saw Catholic layman B. A. Santamaria, the son of Italian immigrants, lead a movement of working class Catholics against Communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

in Australia and the formation of his Democratic Labor Party (DLP) in 1955. The DLP was formed over concerns of Communist influence over the trade unions and Labor Party. The movement was not approved by the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

, but it siphoned a proportion of the Catholic vote away from the Labor Party, contributing to the success of the newly formed Liberal Party of Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, praise, reno ...

, which held power from 1949 to 1972, which, in return for DLP preferences, secured state aid for Catholic schools in Australia in 1963. Along with a sharp decline in sectarianism in post-1960s Australia, sectarian loyalty to political parties has diminished and Catholics have been well represented within the conservative Liberal and National

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

parties. Brendan Nelson

Brendan John Nelson (born 19 August 1958) is an Australian business leader, physician and former politician. He served as the federal Leader of the Opposition from 2007 to 2008, going on to serve as Australia's senior diplomat to the European ...

became the first Catholic to lead the Liberal Party in 2007. Former prime minister Tony Abbott is a former seminarian

A seminary, school of theology, theological college, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called seminarians) in scripture and theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy ...

who won the party leadership after defeating two other Catholic candidates for the post. In 2008, Tim Fischer

Timothy Andrew Fischer (3 May 1946 – 22 August 2019) was an Australian politician and diplomat who served as leader of the National Party of Australia, National Party from 1990 to 1999. He was the tenth Deputy Prime Minister of Australia, d ...

, a Catholic and former deputy prime minister in the Howard government

The Howard government refers to the Government of Australia, federal executive government of Australia led by Prime Minister John Howard between 11 March 1996 and 3 December 2007. It was made up of members of the Liberal Party of Australia, Li ...

, was nominated by the Labor prime minister, Kevin Rudd

Kevin Michael Rudd (born 21 September 1957) is an Australian diplomat and former politician who served as the 26th prime minister of Australia from 2007 to 2010 and June to September 2013. He held office as the Leaders of the Australian Labo ...

, as the first resident Australian ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or so ...

to the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

since 1973, when diplomatic relations with the Vatican and Australia were first established.

Post Second Vatican Council

Since theSecond Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the or , was the 21st and most recent ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council met each autumn from 1962 to 1965 in St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City for session ...

of the 1960s, the Australian church has experienced a decline in vocations to the religious life, leading to a priest shortage

In the years since World War II there has been a substantial reduction in the number of priests ''per capita'' in the Catholic Church, a phenomenon considered by many to constitute a "shortage" in the number of priests. From 1980 to 2012, the ratio ...

. On the other hand, lay leadership in education and other areas has expanded, and about 20% of Australian school students attend a Catholic school. While the numbers of nuns serving in Australian health facilities declined, the church maintained a strong presence in health care. The Sisters of Charity continued their mission among the sick, opening Australia's first HIV AIDS

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a preventable disease. It can ...

ward at St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney, in the 1980s. Declining vocations and increasing complexities in the health care technologies and management saw religious institutes like the Sisters of Charity and Sisters of Mercy amalgamating their efforts and divesting themselves of daily management of hospitals.

Following Vatican II, new styles of ministry were tried by Australian religious. Some rose to national prominence. Fr Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts who served as a member of the United States Senate from 1962 to his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic Party and ...

began one such ministry in Sydney's inner city Redfern presbytery in 1971 – an area with a large Aboriginal population. Working closely with Catholic Aboriginal laywoman "Mum" Shirl Smith, he developed a theology which held that the poor had special insights into the meaning of Christianity, worked as an advocate for Aboriginal rights and often challenged the civil and church establishment on questions of conscience. In 1989, Jesuit lawyer Fr Frank Brennan AO founded Uniya, a centre for social justice and human rights research, advocacy, education and networking. Uniya focused much of its attention on the plight of refugees, asylum seekers, and Indigenous reconciliation. In 1991, Fr Chris Riley formed Youth Off The Streets

Youth Off The Streets is an Australian non-denominational not-for-profit youth organisation. The organisation works with young people and their families and communities in an endeavour to create safety, offer support and provide opportunities to ...

, a community organisation working for young people who are "chronically homeless, drug dependent and recovering from abuse". Originally a food van in Sydney's King's Cross, it has grown to be one of the largest youth services in Australia, offering crisis accommodation, residential rehabilitation, clinical services and counselling, outreach programs, drug and alcohol rehabilitation, specialist Aboriginal services, education and family support. Melbourne priest Father Bob Maguire

Robert John Maguire (14 September 1934 – 19 April 2023), also known as Robert John Thomas Maguire and commonly known as Father Bob, was an Australian Roman Catholic priest, community worker and media personality. From 1973 to 2012, Maguire w ...

began parish work in the 1960s, but became a youth media personality in 2004 with the beginning of a series of collaborations with irreverent satirist John Safran

John Michael Safran (; born 13 August 1972) is an Australian radio personality, satirist, documentary maker and author, known for combining humour with religious, political and ethnic issues. First gaining fame appearing in '' Race Around the W ...

on SBS TV

SBS TV (Seoul Broadcasting System Television) is a South Korean free-to-air television channel operated by Seoul Broadcasting System. The channel was launched on 9 December 1991. Unlike competing network MBC, SBS operates using a federalized ...

and Triple J

Triple J is an Australian government-funded national radio station founded in 1975 as a division of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). It aims to appeal to young listeners of alternative music, and plays far more Australian conten ...

radio.

The year 1970 saw the first visit to Australia by a Pope, Paul VI

Pope Paul VI (born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 until his death on 6 August 1978. Succeeding John XXII ...

. Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

was the next Pope to visit Australia in 1986. At Alice Springs

Alice Springs () is a town in the Northern Territory, Australia; it is the third-largest settlement after Darwin, Northern Territory, Darwin and Palmerston, Northern Territory, Palmerston. The name Alice Springs was given by surveyor William ...

, the Pope made an historic address to indigenous Australians, in which he praised the enduring qualities of Aboriginal culture, lamented the effects of dispossession of and discrimination; called for acknowledgment of Aboriginal land rights

Indigenous land rights are the rights of Indigenous peoples to land and natural resources therein, either individually or collectively, mostly in colonised countries. Land and resource-related rights are of fundamental importance to Indigeno ...

and reconciliation in Australia; and said that the church in Australia would not reach its potential until Aboriginal people had made their "contribution to her life and until that contribution has been joyfully received by others".

In 1988, the Archbishop of Sydney, Edward Bede Clancy was created a cardinal and during the Australian Bicentenary

The bicentenary of Australia was celebrated in 1988. It marked 200 years since the arrival of the First Fleet of British convict ships at Sydney in 1788.

History

The bicentennial year marked Captain Arthur Phillip's arrival with the 11 ships ...

celebrations led the religious ceremonies for the opening of Parliament House, Canberra

Parliament House is the meeting place of the Parliament of Australia, the Legislature, legislative body of Politics of Australia, Australia's federal system of government. The building also houses the core of the Executive (government), execut ...

. Pope John Paul II visited Australia for the second time in 1995, to perform the rite

Rite may refer to:

Religion

* Ritual, an established ceremonious act

* Rite (Christianity), sacred rituals in the Christian religion

* Ritual family, Christian liturgical traditions; often also called ''liturgical rites''

* Catholic particular ch ...

of beatification

Beatification (from Latin , "blessed" and , "to make") is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their name. ''Beati'' is the p ...

for Mary MacKillop, founder of Australia's Josephite Sisters, before a crowd of 250,000.

From the late 1980s, cases of abuse within the Catholic Church and other child care institutions began to be exposed in Australia. In 1996, the church issued a document, ''Towards Healing'', which it described as seeking to "establish a compassionate and just system for dealing with complaints of abuse". In 2001, an apostolic exhortation from Pope John Paul II condemned incidents of sex abuse in Oceania

Oceania ( , ) is a region, geographical region including Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Outside of the English-speaking world, Oceania is generally considered a continent, while Mainland Australia is regarded as its co ...

. Impetus for the ''Towards Healing'' protocols was in part led by Bishop Geoffrey Robinson, who would later call for large scale systemic reform of the church globally in his 2007 book ''Confronting Power and Sex in the Catholic Church: Reclaiming the Spirit of Jesus''. The Australian Catholic Bishops Conference did not endorse the book. Pat Power, the Auxiliary Bishop

An auxiliary bishop is a bishop assigned to assist the diocesan bishop in meeting the pastoral and administrative needs of the diocese. Auxiliary bishops can also be titular bishops of sees that no longer exist as territorial jurisdictions.

...

of Canberra & Goulburn, wrote in 2002 that "the current crisis around sexual abuse is the greatest since the Reformation. At stake is the Church's moral authority, its credibility, its ability to interpret the 'signs of the times' and its capacity to confront the ensuing questions." Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

officially apologised to victims during World Youth Day 2008

World Youth Day 2008 was a Catholic youth festival that started on 15 July and continued until 20 July 2008 in Sydney, Australia. It was the first World Youth Day held in Australia and the first World Youth Day in Oceania. This meeting was deci ...

in Sydney and celebrated a Mass with four victims of clerical sexual abuse in the chapel of St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney

The Cathedral Church and Minor Basilica of the Immaculate Mother of God, Help of Christians, locally known as Saint Mary's Cathedral, is a Catholic basilica and the seat of the Archdiocese of Sydney. The cathedral is dedicated to the Blessed Vi ...

, and listened to their stories.

George Pell

George Pell (8 June 1941 – 10 January 2023) was an Australian cardinal of the Catholic Church. From 2002, he faced recurring accusations of sexual abuse, although his subsequent sexual abuse conviction was quashed on appeal to the High Cour ...

became the eighth Archbishop of Sydney and, in 2003, became a cardinal. Pell supported Sydney's bid to host World Youth Day 2008. In July 2008, Sydney hosted the massive youth festival led by Pope Benedict XVI. Around 500,000 welcomed the pope to Sydney and 270,000 watched the Stations of the Cross

The Stations of the Cross or the Way of the Cross, also known as the Via Dolorosa, Way of Sorrows or the , are a series of fourteen images depicting Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ on the day of Crucifixion of Jesus, his crucifixion and acc ...

. More than 300,000 pilgrims camped out overnight in preparation for the final Mass, where final attendance was between 300,000 and 400,000 people.

In February 2010, Pope Benedict XVI announced that Mary MacKillop would be recognised as the first Australian saint

In Christianity, Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of sanctification in Christianity, holiness, imitation of God, likeness, or closeness to God in Christianity, God. However, the use of the ...

of the Catholic Church. She was canonised on 17 October 2010 during a public ceremony in St Peter's Square

St. Peter's Square (, ) is a large plaza located directly in front of St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, the papal enclave in Rome, directly west of the neighborhood (rione) of Borgo. Both the square and the basilica are named after Saint ...

. An estimated 8,000 Australians were present in the Vatican City

Vatican City, officially the Vatican City State (; ), is a Landlocked country, landlocked sovereign state and city-state; it is enclaved within Rome, the capital city of Italy and Bishop of Rome, seat of the Catholic Church. It became inde ...

to witness the ceremony. The Vatican Museum

The Vatican Museums (; ) are the public museums of the Vatican City. They display works from the immense collection amassed by the Catholic Church and the papacy throughout the centuries, including several of the best-known Roman sculptures and ...

held an exhibition of Aboriginal art

Indigenous Australian art includes art made by Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, including collaborations with others. It includes works in a wide range of media including painting on leaves, bark painting, wood carving, ro ...

to honour the occasion titled "Rituals of Life". The exhibition contained 300 artefacts which were on display for the first time since 1925.

In the late 20th and early 21st century, Catholicism in Australia has been growing numerically, while remaining relatively stable as a proportion of the population and facing a long-term decline in numbers of people following vocations to the religious life. In 2016, the Catholic education sector ran 1,738 schools, accounting for some 20.2% of Australian school students. There were also two Catholic universities – University of Notre Dame Australia

The University of Notre Dame Australia (known simply as Notre Dame; ; French language, French for 'Mary, mother of Jesus, Our Lady') is a Private university, private Catholic university with campuses in Perth, Sydney and Broome, Western Austr ...

and the Australian Catholic University

Australian Catholic University (ACU) is a public university in Australia. It has seven Australian campuses and also maintains a campus in Rome.

History

Australian Catholic University was opened on 1 January 1991 following the amalgamation ...

. Catholic Social Services Australia Catholic Social Services Australia (CSSA) is a body that seeks to advance the social service ministry of the Catholic Church and consists of member welfare organisations. It was established as a commission of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conferen ...

, the church's peak national body for social services, had 52 member organisations providing services to hundreds of thousands of people each year. Catholic Health Australia Catholic Health Australia represents 75 hospitals and 550 residential and community aged care services and comprises Australia's largest non-government not-for-profit grouping of health and aged care services. Catholic Health Australia was establish ...

was the largest non-government provider grouping of health, community, and aged care services.

The church was among the secular and religious institutions examined at the 2013-2017 Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse was a royal commission announced in November 2012 and established in 2013 by the Australian government pursuant to the Royal Commissions Act 1902 to inquire into and repo ...

, which reported that abuse cases by Catholic personnel had peaked in the 1970s, with around 4400 cases and alleged cases over the 6 decades prior to the inquiry. In 2017, there were 5.5 million Australian Catholics. Gerard Henderson

Gerard Henderson (born 1945) is an Australian author, columnist and political commentator noted for his right-wing Catholic and conservative views. He founded and is the executive director of The Sydney Institute, a privately funded Australian ...

stated that statistics presented to the Royal Commission indicated that children were safer in a Catholic religious institution in Australia during the years studied than in any other religious institution (state institutions were not studied, so a statistical comparison could not be made).

Social and political engagement

Introduction

Catholic people and charitable organisations, hospitals and schools have played a prominent role in welfare and education in Australia ever since colonial times when Catholic laywomanCaroline Chisholm

Caroline Chisholm ( ; born Caroline Jones; 30 May 1808 – 25 March 1877) was an English humanitarian known mostly for her support of immigrant female and family welfare in Australia. She is commemorated on 16 May in the Calendar of saints (Ch ...

helped single, migrant women and rescued homeless girls in Sydney. In his welcoming address to the Catholic World Youth Day 2008 in Sydney, the prime minister, Kevin Rudd

Kevin Michael Rudd (born 21 September 1957) is an Australian diplomat and former politician who served as the 26th prime minister of Australia from 2007 to 2010 and June to September 2013. He held office as the Leaders of the Australian Labo ...

, said that Christianity had been a positive influence on Australia: "It was the church that began first schools for the poor, it was the church that began first hospitals for the poor, it was the church that began first refuges for the poor and these great traditions continue for the future".

Welfare

A number of Catholic organisations are providers ofsocial welfare

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance p ...

services (including residential aged care and the Job Network

Workforce Australia is an Australian Government-funded network of organisations (private and community, and originally also government) that are contracted by the Australian Government, through the Department of Employment and Workplace Relati ...

) and education in Australia

Education in Australia encompasses the sectors of early childhood education (preschool) and primary education (primary schools), followed by secondary education (high schools), and finally tertiary education, which includes higher education ( ...

. Australia-wide these include: Centacare

The Catholic Church in Australia is part of the worldwide Catholic Church under the spiritual and administrative leadership of the Holy See. From origins as a suppressed, mainly Irish minority in early colonial times, the church has grow ...