Bladder Cancer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

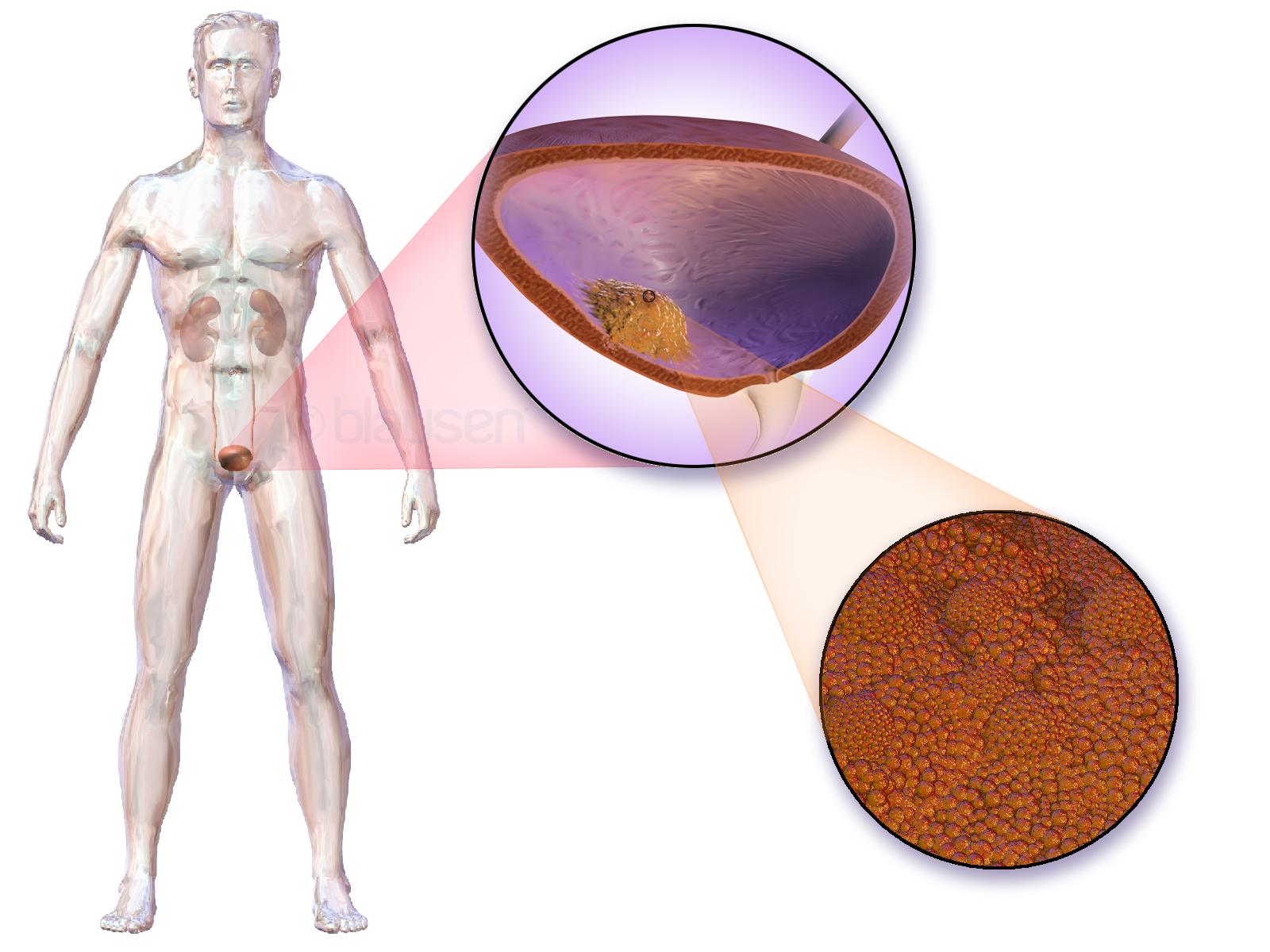

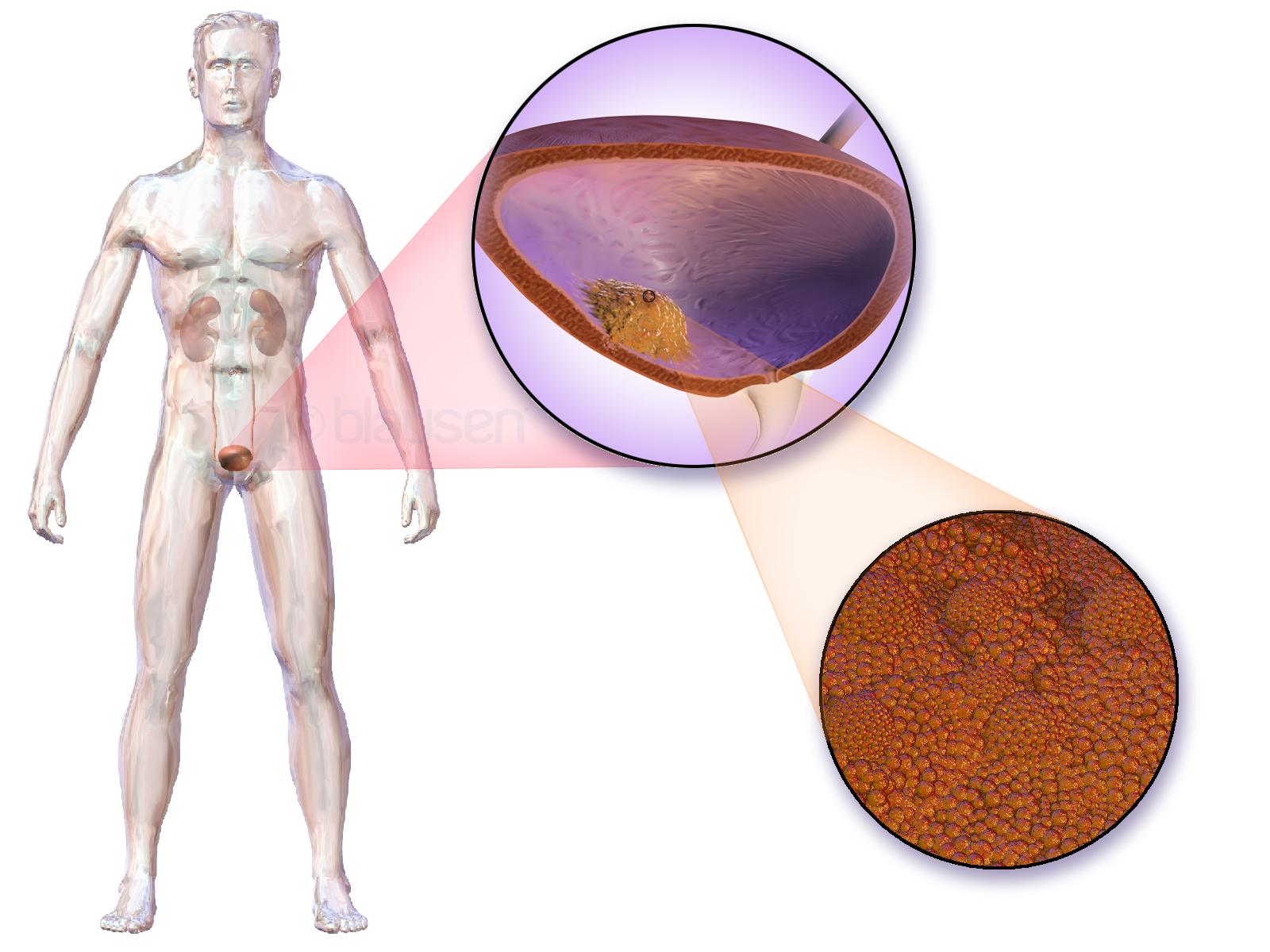

Bladder cancer is the abnormal growth of cells in the bladder. These cells can grow to form a tumor, which eventually spreads, damaging the bladder and other organs. Most people with bladder cancer are diagnosed after noticing blood in their urine. Those suspected of having bladder cancer typically have their bladder inspected by a thin medical camera, a procedure called cystoscopy. Suspected tumors are removed and examined to determine if they are cancerous. Based on how far the tumor has spread, the cancer case is assigned a stage 0 to 4; a higher stage indicates a more widespread and dangerous disease.

Those whose bladder tumors have not spread outside the bladder have the best prognoses. These tumors are typically surgically removed, and the person is treated with chemotherapy or one of several immune-stimulating therapies. Those whose tumors continue to grow, or whose tumors have penetrated the bladder muscle, often have their bladder surgically removed ( radical cystectomy). People whose tumors have spread beyond the bladder have the worst prognoses; on average they survive a year from diagnosis. These people are treated with chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors, followed by enfortumab vedotin.

Around 500,000 people are diagnosed with bladder cancer each year, and 200,000 die of the disease. The risk of bladder cancer increases with age and the average age at diagnosis is 73. Tobacco smoking is the greatest contributor to bladder cancer risk, and causes around half of bladder cancer cases. Exposure to certain toxic chemicals or the tropical bladder infection schistosomiasis also increases the risk.

The most common symptom of bladder cancer is visible blood in the urine (haematuria) despite painless urination. This affects around 75% of people eventually diagnosed with the disease. Some instead have "microscopic haematuria" – small amounts of blood in the urine that can only be seen under a microscope during urinalysis – pain while urinating, or no symptoms at all (their tumors are detected during unrelated medical imaging). Less commonly, a tumor can block the flow of urine into the bladder; backed up urine can cause the kidneys to swell resulting in pain along the flank of the body between the ribs and the hips. Most people with blood in the urine do not have bladder cancer; up to 22% of those with visible haematuria and 5% with microscopic haematuria are diagnosed with the disease. Women with bladder cancer and haematuria are often misdiagnosed with urinary tract infections, delaying appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Around 3% of people with bladder cancer have tumors that have already spread (metastasized) outside the bladder at the time of diagnosis. Bladder cancer most commonly spreads to the bones, lungs, liver, and nearby lymph nodes. Tumors cause different symptoms in each location. People whose cancer has metastasized to the bones most often experience bone pain or bone weakness that increases the risk of fractures. Lung tumors can cause persistent cough, coughing up blood, breathlessness, or recurrent chest infections. Cancer that has spread to the liver can cause general malaise, loss of appetite, weight loss, abdominal pain or swelling, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), and skin itch. Spreading to nearby lymph nodes can cause pain and swelling around the affected lymph nodes, typically in the abdomen or groin.

The most common symptom of bladder cancer is visible blood in the urine (haematuria) despite painless urination. This affects around 75% of people eventually diagnosed with the disease. Some instead have "microscopic haematuria" – small amounts of blood in the urine that can only be seen under a microscope during urinalysis – pain while urinating, or no symptoms at all (their tumors are detected during unrelated medical imaging). Less commonly, a tumor can block the flow of urine into the bladder; backed up urine can cause the kidneys to swell resulting in pain along the flank of the body between the ribs and the hips. Most people with blood in the urine do not have bladder cancer; up to 22% of those with visible haematuria and 5% with microscopic haematuria are diagnosed with the disease. Women with bladder cancer and haematuria are often misdiagnosed with urinary tract infections, delaying appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Around 3% of people with bladder cancer have tumors that have already spread (metastasized) outside the bladder at the time of diagnosis. Bladder cancer most commonly spreads to the bones, lungs, liver, and nearby lymph nodes. Tumors cause different symptoms in each location. People whose cancer has metastasized to the bones most often experience bone pain or bone weakness that increases the risk of fractures. Lung tumors can cause persistent cough, coughing up blood, breathlessness, or recurrent chest infections. Cancer that has spread to the liver can cause general malaise, loss of appetite, weight loss, abdominal pain or swelling, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), and skin itch. Spreading to nearby lymph nodes can cause pain and swelling around the affected lymph nodes, typically in the abdomen or groin.

Suspected tumors are removed during cystoscopy in a procedure called "transurethral resection of bladder tumor" (TURBT). All tumors are removed, as well as a piece of the underlying bladder muscle. Removed tissue is examined by a pathologist to determine if it is cancerous. If the tumor is removed incompletely, or is determined to be particularly high risk, a repeat TURBT is performed 4 to 6 weeks later to detect and remove any additional tumors.

Several non-invasive tests are available to support the diagnosis. First, many undergo a physical examination that can involve a digital rectal exam and pelvic exam, where a doctor feels the pelvic area for unusual masses that could be tumors. Severe bladder tumors often shed cells into the urine; these can be detected by urine cytology, where cells are collected from a urine sample, and viewed under a

Suspected tumors are removed during cystoscopy in a procedure called "transurethral resection of bladder tumor" (TURBT). All tumors are removed, as well as a piece of the underlying bladder muscle. Removed tissue is examined by a pathologist to determine if it is cancerous. If the tumor is removed incompletely, or is determined to be particularly high risk, a repeat TURBT is performed 4 to 6 weeks later to detect and remove any additional tumors.

Several non-invasive tests are available to support the diagnosis. First, many undergo a physical examination that can involve a digital rectal exam and pelvic exam, where a doctor feels the pelvic area for unusual masses that could be tumors. Severe bladder tumors often shed cells into the urine; these can be detected by urine cytology, where cells are collected from a urine sample, and viewed under a

A bladder cancer case is assigned a stage based on the TNM system. A tumor is assigned three scores based on the extent of the primary tumor (T), its spread to nearby lymph nodes (N), and metastasis to distant sites (M).

The T score represents the extent of the original tumor. Tumors confined to the innermost layer of the bladder are designated Tis (for CIS tumors) or Ta (all others). Otherwise they are assigned a numerical score based on how far they have spread: into the bladder's connective tissue (T1), bladder muscle (T2), surrounding fatty tissue (T3) or extension fully outside the bladder (T4). The N score represents spread to nearby lymph nodes: N0 for no spread; N1 for spread to a single nearby lymph node; N2 for spread to several nearby lymph nodes; N3 for spread to more distant lymph nodes outside the pelvis. The M score designates spread to distant organs: M0 for a tumor that has not spread; M1 for one that has. The TNM scores are combined to determine the cancer case's stage on a scale of 0 to 4. A higher stage means a more extensive cancer with a poorer prognosis.

Around 75% of cases are confined to the bladder at the time of diagnosis (T scores: Tis, Ta, or T1), and are called non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). Around 18% have tumors that have spread into the bladder muscle (T2, T3, or T4), and are called muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Around 3% have tumors that have spread to organs far from the bladder, and are called metastatic bladder cancer. Those with more extensive tumor spread tend to have a poorer prognosis.

A bladder cancer case is assigned a stage based on the TNM system. A tumor is assigned three scores based on the extent of the primary tumor (T), its spread to nearby lymph nodes (N), and metastasis to distant sites (M).

The T score represents the extent of the original tumor. Tumors confined to the innermost layer of the bladder are designated Tis (for CIS tumors) or Ta (all others). Otherwise they are assigned a numerical score based on how far they have spread: into the bladder's connective tissue (T1), bladder muscle (T2), surrounding fatty tissue (T3) or extension fully outside the bladder (T4). The N score represents spread to nearby lymph nodes: N0 for no spread; N1 for spread to a single nearby lymph node; N2 for spread to several nearby lymph nodes; N3 for spread to more distant lymph nodes outside the pelvis. The M score designates spread to distant organs: M0 for a tumor that has not spread; M1 for one that has. The TNM scores are combined to determine the cancer case's stage on a scale of 0 to 4. A higher stage means a more extensive cancer with a poorer prognosis.

Around 75% of cases are confined to the bladder at the time of diagnosis (T scores: Tis, Ta, or T1), and are called non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). Around 18% have tumors that have spread into the bladder muscle (T2, T3, or T4), and are called muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Around 3% have tumors that have spread to organs far from the bladder, and are called metastatic bladder cancer. Those with more extensive tumor spread tend to have a poorer prognosis.

People whose tumors continue to grow are often treated with surgery to remove the bladder and surrounding organs, called radical cystectomy. The bladder, several adjacent lymph nodes, the lower ureters, and nearby internal genital organs – in men the prostate and seminal vesicles; in women the womb and part of the

People whose tumors continue to grow are often treated with surgery to remove the bladder and surrounding organs, called radical cystectomy. The bladder, several adjacent lymph nodes, the lower ureters, and nearby internal genital organs – in men the prostate and seminal vesicles; in women the womb and part of the

Around 500,000 people are diagnosed with bladder cancer each year, and 200,000 die of the disease. This makes bladder cancer the tenth most commonly diagnosed cancer, and the thirteenth cause of cancer deaths. Bladder cancer is most common in wealthier regions of the world, where exposure to certain carcinogens is highest. It is also common in places where schistosome infection is common, such as North Africa.

Bladder cancer is much more common in men than women; around 1.1% of men and 0.27% of women develop bladder cancer. This makes bladder cancer the sixth most common cancer in men, and the seventeenth in women. When women are diagnosed with bladder cancer, they tend to have more advanced disease and consequently a poorer prognosis. This difference in outcomes is attributed to numerous factors such as difference in carcinogen exposure,

Around 500,000 people are diagnosed with bladder cancer each year, and 200,000 die of the disease. This makes bladder cancer the tenth most commonly diagnosed cancer, and the thirteenth cause of cancer deaths. Bladder cancer is most common in wealthier regions of the world, where exposure to certain carcinogens is highest. It is also common in places where schistosome infection is common, such as North Africa.

Bladder cancer is much more common in men than women; around 1.1% of men and 0.27% of women develop bladder cancer. This makes bladder cancer the sixth most common cancer in men, and the seventeenth in women. When women are diagnosed with bladder cancer, they tend to have more advanced disease and consequently a poorer prognosis. This difference in outcomes is attributed to numerous factors such as difference in carcinogen exposure,

Signs and symptoms

The most common symptom of bladder cancer is visible blood in the urine (haematuria) despite painless urination. This affects around 75% of people eventually diagnosed with the disease. Some instead have "microscopic haematuria" – small amounts of blood in the urine that can only be seen under a microscope during urinalysis – pain while urinating, or no symptoms at all (their tumors are detected during unrelated medical imaging). Less commonly, a tumor can block the flow of urine into the bladder; backed up urine can cause the kidneys to swell resulting in pain along the flank of the body between the ribs and the hips. Most people with blood in the urine do not have bladder cancer; up to 22% of those with visible haematuria and 5% with microscopic haematuria are diagnosed with the disease. Women with bladder cancer and haematuria are often misdiagnosed with urinary tract infections, delaying appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Around 3% of people with bladder cancer have tumors that have already spread (metastasized) outside the bladder at the time of diagnosis. Bladder cancer most commonly spreads to the bones, lungs, liver, and nearby lymph nodes. Tumors cause different symptoms in each location. People whose cancer has metastasized to the bones most often experience bone pain or bone weakness that increases the risk of fractures. Lung tumors can cause persistent cough, coughing up blood, breathlessness, or recurrent chest infections. Cancer that has spread to the liver can cause general malaise, loss of appetite, weight loss, abdominal pain or swelling, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), and skin itch. Spreading to nearby lymph nodes can cause pain and swelling around the affected lymph nodes, typically in the abdomen or groin.

The most common symptom of bladder cancer is visible blood in the urine (haematuria) despite painless urination. This affects around 75% of people eventually diagnosed with the disease. Some instead have "microscopic haematuria" – small amounts of blood in the urine that can only be seen under a microscope during urinalysis – pain while urinating, or no symptoms at all (their tumors are detected during unrelated medical imaging). Less commonly, a tumor can block the flow of urine into the bladder; backed up urine can cause the kidneys to swell resulting in pain along the flank of the body between the ribs and the hips. Most people with blood in the urine do not have bladder cancer; up to 22% of those with visible haematuria and 5% with microscopic haematuria are diagnosed with the disease. Women with bladder cancer and haematuria are often misdiagnosed with urinary tract infections, delaying appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Around 3% of people with bladder cancer have tumors that have already spread (metastasized) outside the bladder at the time of diagnosis. Bladder cancer most commonly spreads to the bones, lungs, liver, and nearby lymph nodes. Tumors cause different symptoms in each location. People whose cancer has metastasized to the bones most often experience bone pain or bone weakness that increases the risk of fractures. Lung tumors can cause persistent cough, coughing up blood, breathlessness, or recurrent chest infections. Cancer that has spread to the liver can cause general malaise, loss of appetite, weight loss, abdominal pain or swelling, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), and skin itch. Spreading to nearby lymph nodes can cause pain and swelling around the affected lymph nodes, typically in the abdomen or groin.

Diagnosis

Those suspected of having bladder cancer undergo several tests to assess the presence and extent of any tumors. Thegold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

is cystoscopy, wherein a flexible camera is threaded through the urethra and into the bladder to visually inspect for cancerous tissue. Cystoscopy is most efficient at detecting papillary tumors (tumors with a finger-like shape that grow into the urine-holding part of the bladder); it is less efficient with small, low-lying carcinoma in situ (CIS). CIS detection is improved by blue light cystoscopy, where a dye ( hexaminolevulinate) that accumulates in cancer cells is injected into the bladder during cystoscopy. The dye fluoresces when the cystoscope shines blue light on it, allowing for more accurate detection of small tumors.

Suspected tumors are removed during cystoscopy in a procedure called "transurethral resection of bladder tumor" (TURBT). All tumors are removed, as well as a piece of the underlying bladder muscle. Removed tissue is examined by a pathologist to determine if it is cancerous. If the tumor is removed incompletely, or is determined to be particularly high risk, a repeat TURBT is performed 4 to 6 weeks later to detect and remove any additional tumors.

Several non-invasive tests are available to support the diagnosis. First, many undergo a physical examination that can involve a digital rectal exam and pelvic exam, where a doctor feels the pelvic area for unusual masses that could be tumors. Severe bladder tumors often shed cells into the urine; these can be detected by urine cytology, where cells are collected from a urine sample, and viewed under a

Suspected tumors are removed during cystoscopy in a procedure called "transurethral resection of bladder tumor" (TURBT). All tumors are removed, as well as a piece of the underlying bladder muscle. Removed tissue is examined by a pathologist to determine if it is cancerous. If the tumor is removed incompletely, or is determined to be particularly high risk, a repeat TURBT is performed 4 to 6 weeks later to detect and remove any additional tumors.

Several non-invasive tests are available to support the diagnosis. First, many undergo a physical examination that can involve a digital rectal exam and pelvic exam, where a doctor feels the pelvic area for unusual masses that could be tumors. Severe bladder tumors often shed cells into the urine; these can be detected by urine cytology, where cells are collected from a urine sample, and viewed under a microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory equipment, laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic ...

. Cytology can detect around two thirds of high-grade tumors, but detects just 1 in 8 low-grade tumors. Additional urine tests can be used to detect molecules associated with bladder cancer. Some detect the bladder tumor antigen (BTA) protein, or NMP22 that tend to be elevated in the urine of those with bladder cancer; some detect the mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

of tumor-associated genes; some use fluorescence microscopy to detect cancerous cells, which is more sensitive than regular microscopy.

The upper urinary tract ( ureters and kidney) is also imaged for tumors that could cause blood in the urine. This is typically done by injecting a dye into the blood that the kidneys will filter into the urinary tract, then imaging by CT scanning. Those whose kidneys are not functioning well enough to filter the dye may instead be scanned by MRI. Alternatively, the upper urinary tract can be imaged with ultrasound.

Classification

Bladder tumors are classified by their appearance under the microscope, and by their cell type of origin. Over 90% of bladder tumors arise from the cells that form the bladder's inner lining, called urothelial cells or transitional cells; the tumor is then classified as urothelial cancer or transitional cell cancer. Around 5% of cases are squamous cell cancer (from a rarer cell in the bladder lining), which are less rare in countries where schistosomiasis occurs. Up to 2% of cases are adenocarcinoma (from mucus-producing gland cells). The remaining cases are sarcomas (from the bladder muscle) or small-cell cancer (from neuroendocrine cells), both of which are relatively rare. The pathologist also grades the tumor sample based on how distinct the cancerous cells look from healthy cells. Bladder cancer is divided into either low-grade (more similar to healthy cells) or high-grade (less similar).Staging

Treatment

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

NMIBC is primarily treated by surgically removing all tumors by TURBT in the same procedure used to collect biopsy tissue for diagnosis. For those with a relatively low risk of tumors recurring, a single bladder injection of chemotherapy ( mitomycin C, epirubicin, or gemcitabine) reduces the risk of tumors regrowing by about 40%. Those with higher risk are instead treated with bladder injections of the BCG vaccine (a live bacterial vaccine, traditionally used for tuberculosis), administered weekly for six weeks. This nearly halves the rate of tumor recurrence. Recurrence risk is further reduced by a series of "maintenance" BCG injections, given regularly for at least a year. Tumors that do not respond to BCG may be treated with the alternative immune stimulants nadofaragene firadenovec (sold as "Adstiladrin", a gene therapy that makes bladder cells produce an immunostimulant protein), nogapendekin alfa inbakicept ("Anktiva", a combination of immunostimulant proteins), or pembrolizumab ("Keytruda", an immune checkpoint inhibitor).vagina

In mammals and other animals, the vagina (: vaginas or vaginae) is the elastic, muscular sex organ, reproductive organ of the female genital tract. In humans, it extends from the vulval vestibule to the cervix (neck of the uterus). The #Vag ...

l wall – are all removed.

Surgeons then construct a new way for urine to leave the body. The most common method is by ileal conduit, where a piece of the ileum

The ileum () is the final section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear and the terms posterior intestine or distal intestine may ...

(part of the small intestine) is removed and used to transport urine from the ureters to a new surgical opening (stoma

In botany, a stoma (: stomata, from Greek language, Greek ''στόμα'', "mouth"), also called a stomate (: stomates), is a pore found in the Epidermis (botany), epidermis of leaves, stems, and other organs, that controls the rate of gas exc ...

) in the abdomen. Urine drains passively into an ostomy bag worn outside the body, which can be emptied regularly by the wearer. Alternatively, one can have a continent urinary diversion, where the ureters are attached to a piece of ileum that includes the valve between the small and large intestine; this valve naturally closes, allowing urine to be retained in the body rather than in an ostomy bag. The affected person empties the new urine reservoir several times each day by self- catheterization – passing a narrow tube through the stoma. Some can instead have the piece of ileum attached directly to the urethra, allowing the affected person to urinate through the urethra as they would pre-surgery – although without the original bladder nerves, they will no longer have the urge to urinate when the urine reservoir is full.

Those not well enough or unwilling to undergo radical cystectomy may instead benefit from further bladder injections of chemotherapy – mitomycin C, gemcitabine, docetaxel, or valrubicin – or intravenous injection of pembrolizumab. Around 1 in 5 people with NMIBC will eventually progress to MIBC.

Most people with muscle-invasive bladder cancer are treated with radical cystectomy, which cures around half of those affected. Treating with chemotherapy prior to surgery (called " neoadjuvant therapy") using a cisplatin-containing drug combination (gemcitabine plus cisplatin; or methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin) improves survival an additional 5 to 10%.

Those with certain types of lower-risk disease may instead receive bladder-sparing therapy. People with just a single tumor at the back of the bladder can undergo partial cystectomy, with the tumor and surrounding area removed, and the bladder repaired. Those with no CIS or urinary blockage may undergo TURBT to remove visible tumors, followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy

Radiation therapy or radiotherapy (RT, RTx, or XRT) is a treatment using ionizing radiation, generally provided as part of cancer therapy to either kill or control the growth of malignant cells. It is normally delivered by a linear particle ...

, known as "trimodality therapy". Around two thirds of these people are cured. After treatment, surveillance tests – urine and blood tests, and MRI or CT scans – are done every three to six months to look for evidence that tumors may be recurring. Those who have retained their bladder also receive cystoscopies to look for additional bladder tumors. If cancer is found in lymph nodes removed during surgery, or there is high risk of recurrence, radiotherapy may be given after surgery. Recurrent bladder tumors are treated with radical cystectomy. Tumor recurrences elsewhere are treated as metastatic bladder cancer.

Metastatic disease

Stage IV bladder cancer that has reached the pelvic or abdominal wall (T4b), spread to distant lymph nodes (M1a) or other parts of the body (M1b) is difficult to completely remove surgically, the initial treatment usually being chemotherapy. The 2022 standard of care for metastatic bladder cancer is combination treatment with the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine. The average person on this combination survives around a year, though 15% experience remission, with survival over five years. Around half of those with metastatic bladder cancer are in too poor health to receive cisplatin. They instead receive the related drug carboplatin along with gemcitabine; the average person on this regimen survives around 9 months. Those whose disease responds to chemotherapy benefit from switching to immune checkpoint inhibitors pembrolizumab or atezolizumab ("Tecentriq") for long-term maintenance therapy. Immune checkpoint inhibitors are also commonly given to those whose tumors do not respond to chemotherapy, as well as those in too poor health to receive chemotherapy. Alternate treatment options might include: * the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab (Keytruda) combined with the antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) enfortumab vedotin (Padcev). This combination has also been recommended as a first-line therapy in place of chemotherapy. * the immunotherapy drug nivolumab (Opdivo) in conjunction with chemotherapy * chemotherapy, followed by the immunotherapy drug avelumab (Bavencio) Those whose tumors continue to grow after platinum chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors can receive the ADC enfortumab vedotin ("Padcev", targets tumor cells with the protein nectin-4). Those with genetic alterations that activate the proteins FGFR2 or FGFR3 (around 20% of those with metastatic bladder cancer) can also benefit from the FGFR inhibitor erdafitinib ("Balversa"). Bladder cancer that continues growing can be treated with second-line chemotherapies. Vinflunine is used in Europe, while paclitaxel, docetaxel, and pemetrexed are used in the United States; only a minority of those treated improve on these therapies. If medicines are no longer controlling the cancer, other treatments may still be helpful, e.g., palliative care that focuses on preventing or relieving problems the cancer may cause. Because metastatic bladder cancers are rarely cured by current treatment methods, many experts suggest considering clinical trials evaluating alternative treatments.Treatment adverse effects

Radical cystectomy has both immediate and lifelong side effects. It is common for those recovering from surgery to experience gastrointestinal problems (29% of those who underwent radical cystectomy), infections (25%), and other issues with the surgical wound (15%). Around 25% of those who undergo the surgery end up readmitted to the hospital within 30 days; up to 2% die within 30 days of the surgery. Rerouting the ureters, urinary diversions, can cause permanent metabolic issues. The piece of ileum used to reroute urine flow can absorb more ions from the urine than the original bladder would, resulting in metabolic acidosis (blood becoming too acidic), which can be treated with sodium bicarbonate. Shortening the small intestine can result in reduced vitamin B12 absorption, which can be treated with oral vitamin B12 supplementation. Issues with the new urine system can cause urinary retention, which can damage the ureters and kidneys and increase one's risk of urinary tract infection. Chemotherapy common side effects include; hair loss, mouth sores, loss of appetite, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, premature menopause, infertility, and damage to the blood-forming cells within bone marrow. Most acute side effects are temporary, dissipating when treatment ceases, but some can be long-lasting or permanent. Long-term chemotherapy side effects include changes in the menstrual cycle, neuropathy, and nephrotoxicity. Checkpoint inhibitor (immunotherapy) side effects commonly include injection site pain, soreness, itchiness or rash. Additional flu-like symptoms may occur like fever, weakness, dizziness, nausea or vomiting, headache, fatigue, or blood pressure changes. More serious side effects might include heart palpitations, diarrhea, infection and organ inflammation. Some people might have allergic reactions with wheezing or breathing problems. Autoimmune reactions are possible because checkpoint inhibitors function by altering or removing immune system safeguards which can cause serious or even life-threatening problems. Antibody-drug conjugate side effects frequently include diarrhea and liver problems. Other side effects might include issues with blood clotting and wound healing, high blood pressure, fatigue, mouth sores, nail changes, loss of hair color, skin rash, or dry skin. Very rarely, a hole might form through the wall of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large bowel, rectum, or gallbladder. Radiotherapy acute side effects involve the gastrointestinal system, e.g., diarrhea and constipation; the urinary tract; and may cause cervicitis. Common late effects include: premature ovarian failure; telangiectasias, and subsequent hemorrhage; and progressive myelopathy. Pelvic radiotherapy late effects (with occurrence rates) include osteonecrosis (8-20%), vaginal stenosis (>2.5%) and chronic pelvic radiation disease (1-10%), e.g., lumbosacral plexopathy. Radiation also induces secondary malignancies such as leukemia, lymphoma, bone and soft-tissue sarcoma with occurrence rates between 0.2-1.0% per year for each. See also: Radiation therapy#Side effects.Causes

Bladder cancer is caused by changes to the DNA of bladder cells that result in those cells growing uncontrollably. These changes can be random, or can be induced by exposure to toxic substances such as those from consuming tobacco. Genetic damage accumulates over many years, eventually disrupting the normal functioning of bladder cells and causing them to grow uncontrollably into a lump of cells called a tumor. Cancer cells accumulate further DNA changes as they multiply, which can allow the tumor to evade the immune system, resist regular cell death pathways, and eventually spread to distant body sites. The new tumors that form in various organs damage those organs, eventually causing the death of the affected person.Smoking

Tobacco smoking is the main contributor to bladder cancer risk; around half of bladder cancer cases are estimated to be caused by smoking. Tobacco smoke contains carcinogenic molecules that enter the blood and are filtered by the kidneys into the urine. There they can cause damage to the DNA of bladder cells, eventually leading to cancer. Bladder cancer risk rises both with number of cigarettes smoked per day, and with duration of smoking habit. Those who smoke also tend to have an increased risk of treatment failure, metastasis, and death. The risk of developing bladder cancer decreases in those who quit smoking, falling by 30% after five years of smoking abstention. However, the risk will remain higher than those who have never smoked before. Because development of bladder cancer takes many years, it is not yet known if use of electronic cigarettes carries the same risk as smoking tobacco; however, those who use electronic cigarettes have higher levels of some urinary carcinogens than those who do not.Occupational exposure

Up to 10% of bladder cancer cases are caused by workplace exposure to toxic chemicals. Exposure to certain aromatic amines, namely benzidine, beta-naphthylamine, and ortho-toluidine used in the metalworking and dye industries, can increase the risk of bladder cancer in metalworkers, dye producers, painters, printers, hairdressers, and textiles workers. The International Agency for Research on Cancer further classifies rubber processing, aluminum production, and firefighting as occupations that increase one's risk of developing bladder cancer. Exposure to arsenic – either through workplace exposure or through drinking water in places where arsenic naturally contaminates groundwater – is also commonly linked to bladder cancer risk.Medical conditions

Chronic bladder infections can increase one's risk of developing bladder cancer. Most prominent is schistosomiasis, in which the eggs of the flatworm '' Schistosoma haematobium'' can become lodged in the bladder wall, causing chronic bladder inflammation and repeated bladder infections. In places withendemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

schistosomiasis, up to 16% of bladder cancer cases are caused by prior Schistosoma infection. Worms can be cleared by treatment with praziquantel, which reduces bladder cancer cases in schistosomiasis endemic areas. Similarly, those with long-term indwelling catheters are at risk for repeated urinary tract infections, and have increased risk of developing bladder cancer.

Some medical treatments are also known to increase bladder cancer risk. As many as 16% of those treated with the chemotherapeutic cyclophosphamide go on to develop bladder cancer within 15 years of their treatment. Similarly, those treated with pelvic radiation (typically for prostate or cervical cancer) are at increased risk of developing bladder cancer five to 15 years after treatment. Long-term use of the medication pioglitazone for type 2 diabetes may increase bladder cancer risk.

Genetics

Bladder cancer does not typically run in families. Only 4% of those diagnosed with bladder cancer have a parent or sibling with the disease, potentially inheriting a gene syndrome associated with bladder cancer, for example: * Mutations of the RB1 gene, while associated with 95% of Retinoblastoma cases, are also linked with bladder cancer. * Cowden disease is caused by mutations in the PTEN gene; see Cowden syndrome#Genetics. People with this syndrome have increased risk of developing several cancers, including bladder cancer. * Lynch syndrome is caused by mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 or PMS2; see main article Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). People with this syndrome have increased risk of developing several cancers, including bladder and urinary tract cancers. Large population studies have identified additional gene variants that each slightly increase bladder cancer risk. Most of these are variants in genes involved in metabolism of carcinogens ( NAT2, GSTM1, and UGT1A6), controlling cell growth ( TP63, CCNE1, MYC, and FGFR3), or repairing DNA damage ( NBN, XRCC1 and 3, and ERCC2, 4, and 5).Diet and lifestyle

Several studies have examined the impact of lifestyle factors on the risk of developing bladder cancer. A 2018 summary of evidence from the World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research concluded that there is "limited, suggestive evidence" that consumption of tea, and a diet high in fruits and vegetables reduce a person's risk of developing bladder cancer. They also considered available data on exercise, body fat, and consumption of dairy, red meat, fish, grains, legumes, eggs, fats, soft drinks, alcohol, juices, caffeine, sweeteners, and various vitamins and minerals; for each they found insufficient data to link the lifestyle factor to bladder cancer risk. Other studies have indicated a slight increased risk of developing bladder cancer in those who are overweight or obese, as well as a slight decrease in risk for those who undertake high levels of physical activity.Pathophysiology

Bladder tumors typically arise from the urothelium, the cell layer that lines the urine-storing part of the bladder. Parts of the urothelium can accumulate DNA mutations over years, making these areas more likely to give rise to tumors. This effect, called field cancerization, can allow several tumors to arise in the same area, or tumors to re-emerge from a given area after a first tumor was removed. Additionally, a cell that becomes cancerous can grow to give rise to several tumors – nearby and recurrent tumors are often monoclonal (descended from the same cancerous cell). Despite arising from the same tissue, NMIBC and MIBC develop along distinct pathways and bear distinct genetic mutations. Most NMIBC tumors start as low-grade papillary (finger-like, projecting into the bladder) tumors. Mutations in cell growth pathways are common. Most common are mutations that activate FGFR3 (present in up to 80% of NMIBC tumors). Mutations activating the growth pathway PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway are also common, including mutations in PIK3CA (in around 30% of tumors) and ERBB2/ERBB3

Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-3, also known as HER3 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 3), is a membrane bound protein that in humans is encoded by the ''ERBB3'' gene.

ErbB3 is a member of the EGFR family, epidermal growth factor re ...

(up to 15% of tumors), and loss of TSC1 (50% of tumors). Major regulators of chromatin (influences the expression of different genes) are inactivated in over 65% of NMIBC tumors.

MIBC often starts with low-lying, flat, high-grade tumors, that quickly spread beyond the bladder. These tumors have more genetic mutations and chromosomal abnormalities overall, with mutations more frequent than in any cancer but lung cancer and melanoma. Mutations that inactivate the tumor suppressor genes TP53

p53, also known as tumor protein p53, cellular tumor antigen p53 (UniProt name), or transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53) is a regulatory transcription factor protein that is often mutated in human cancers. The p53 proteins (originally thou ...

and RB are common, as are mutations in CDH1 (involved in metastasis) and VEGFR2 (involved in cell growth and metastasis).

Some genetic abnormalities are common to NMIBC and MIBC tumors. Around half of each have lost all or part of chromosome 9, which contains several regulators of tumor suppressor genes. Up to 80% of tumors have mutations in the gene TERT, which extends cells' telomeres to allow for extended replication.

Prognosis

Bladder cancer prognosis varies based on how widespread the cancer is at the time of diagnosis. For those with tumors confined to the innermost layer of the bladder (stage 0 disease), 96% are still alive five years from diagnosis. Those whose tumors have spread to nearby lymph nodes (stage 3 disease) have worse prognoses; 36% survive at least five years from diagnosis. Those with metastatic bladder cancer (stage 4 disease) have the most severe prognosis, with 5% alive five years from diagnosis.Epidemiology

genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

, social factors and quality of care.

As with most cancers, bladder cancer is more common in older people; the average person with bladder cancer is diagnosed at age 73. 80% of those diagnosed with bladder cancer are 65 or older; 20% are 85 or older.

Veterinary medicine

Bladder cancer is relatively rare in domestic dogs and cats. In dogs, around 1% of diagnosed cancers are bladder cancer. Shetland sheepdogs, beagles, and various terriers are at increased risk relative to other breeds. Signs of a bladder tumor – blood in the urine, frequent urination, or trouble urinating – are common to other canine urinary conditions, and so diagnosis is often delayed. Urine tests can aid in diagnosis; they test for the protein bladder tumor antigen (high in bladder tumors) or mutations in the BRAF gene (present in around 80% of dogs with bladder or prostate cancer). Dogs with confirmed cancer are treated with COX-2 inhibitor drugs, such as piroxicam, deracoxib, and meloxicam. These drugs halt disease progression in around 50% of dogs, shrink tumors in around 12%, and eliminate tumors in around 6%. COX-2 inhibitors are often combined with chemotherapy drugs, most commonly mitoxantrone, vinblastine, or chlorambucil. Bladder cancer is much less common in cats than in dogs; treatment is similar to that of canine bladder cancer, with chemotherapy and COX-2 inhibitors commonly used.Charities and funding

Several charities provide support for individuals affected by bladder cancer and fund research into improved treatments. Organisations such as Cancer Research UK (United Kingdom), Fight Bladder Cancer (United Kingdom), Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network (United States), and The World Bladder Cancer Patient Coalition (international), offer patient support, educational resources, and advocacy initiatives. These organisations contribute to research funding, early diagnosis campaigns, and patient support services, aiming to improve outcomes for those diagnosed with bladder cancer. Independent studies and health reports have recognised their role in advancing bladder cancer awareness and care.References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bladder Cancer Health effects of tobacco Types of cancer