Bacteriophage Lambda Structure on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a

Bacterial viruses lack common ancestry and, for that reason, are classified in many unrelated taxa, listed hereafter:

* In the realm ''

Bacterial viruses lack common ancestry and, for that reason, are classified in many unrelated taxa, listed hereafter:

* In the realm ''

The life cycle of bacteriophages tends to be either a lytic cycle or a

The life cycle of bacteriophages tends to be either a lytic cycle or a

Bacterial cells are protected by a cell wall of

Bacterial cells are protected by a cell wall of

Bacteriophage genomes can be highly

Bacteriophage genomes can be highly

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

that infects and replicates within bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s that encapsulate a DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

or RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

, and may have structures that are either simple or elaborate. Their genomes may encode as few as four genes (e.g. MS2) and as many as hundreds of genes

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

. Phages replicate within the bacterium following the injection of their genome into its cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

.

Bacteriophages are among the most common and diverse entities in the biosphere

The biosphere (), also called the ecosphere (), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also be termed the zone of life on the Earth. The biosphere (which is technically a spherical shell) is virtually a closed system with regard to mat ...

. Bacteriophages are ubiquitous viruses, found wherever bacteria exist. It is estimated there are more than 1031 bacteriophages on the planet, more than every other organism on Earth, including bacteria, combined. Viruses are the most abundant biological entity in the water column of the world's oceans, and the second largest component of biomass after prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s, where up to 9x108 virions

A virion (plural, ''viria'' or ''virions'') is an inert virus particle capable of invading a cell. Upon entering the cell, the virion disassembles and the genetic material from the virus takes control of the cell infrastructure, thus enabling th ...

per millilitre have been found in microbial mats

A microbial mat is a multi-layered sheet or biofilm of microbial colony (biology), colonies, composed of mainly bacteria and/or archaea. Microbial mats grow at interface (chemistry), interfaces between different types of material, mostly on submer ...

at the surface, and up to 70% of marine bacteria may be infected by bacteriophages.

Bacteriophages were used from the 1920s as an alternative to antibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

in the former Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and Central Europe, as well as in France and Brazil. – Documentary about the history of phage medicine in Russia and the West They are seen as a possible therapy against multi-drug-resistant strains of many bacteria.

Bacteriophages are known to interact with the immune system both indirectly via bacterial expression of phage-encoded proteins and directly by influencing innate immunity and bacterial clearance. Phage–host interactions are becoming increasingly important areas of research.

Classification

Bacterial viruses lack common ancestry and, for that reason, are classified in many unrelated taxa, listed hereafter:

* In the realm ''

Bacterial viruses lack common ancestry and, for that reason, are classified in many unrelated taxa, listed hereafter:

* In the realm ''Duplodnaviria

''Duplodnaviria'' is a realm of viruses that includes all double-stranded DNA viruses that encode the HK97 fold major capsid protein. The HK97 fold major capsid protein (HK97 MCP) is the primary component of the viral capsid, which stores ...

'', the class ''Caudoviricetes

''Caudoviricetes'' is a class of viruses known as tailed viruses and head-tail viruses (''cauda'' is Latin for "tail"). It is the sole representative of its own phylum, ''Uroviricota'' (from ''ouros'' (ουρος), a Greek word for "tailed" + ...

'' contains bacterial viruses. Unlike the other taxa listed here, ''Caudoviricetes'' does not exclusively contain bacterial viruses; archaeal virus

An archaeal virus is a virus that infects and replicates in archaea, a domain of unicellular, prokaryotic organisms. Archaeal viruses, like their hosts, are found worldwide, including in extreme environments inhospitable to most life such as ac ...

es are also included in the class. Caudoviruses are also called tailed viruses or head-tail viruses, and they are often sorted into three types based on tail morphology: podoviruses (short tail), myoviruses (long, contractile tail), and siphoviruses (long, non-contractile tail).

* In the realm ''Monodnaviria

''Monodnaviria'' is a Realm (virology), realm of viruses that includes all DNA virus#Group II: ssDNA viruses, single-stranded DNA viruses that Genetic code, encode an HUH-tag, endonuclease of the HUH superfamily that initiates rolling circle repli ...

'', the kingdoms ''Loebvirae

''Tubulavirales'' is an order of viruses.

Taxonomy

The order contains the following families:

* ''Inoviridae

Filamentous bacteriophages are a family of viruses (''Inoviridae'') that infect bacteria, or bacteriophages. They are named for the ...

'' and ''Sangervirae

''Microviridae'' is a family of bacteriophages with a single-stranded DNA genome. The name of this family is derived from the ancient Greek word (), meaning "small". This refers to the size of their genomes, which are among the smallest of the ...

'' contain bacterial viruses.

* In the realm ''Riboviria

''Riboviria'' is a Realm (virology), realm of viruses that includes all viruses that use a homologous RNA-dependent polymerase for replication. It includes RNA viruses that Genetic code, encode an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, as well as Pararnavi ...

'', the phylum ''Artimaviricota

''Atsuirnavirus'' is a genus of virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, in ...

'', the class ''Vidaverviricetes

Cystoviruses are a family of double-stranded RNA viruses that infect bacteria. They constitute the family ''Cystoviridae''. The name of the group c''ysto'' derives from Greek ''kystis'' which means bladder or sack. There are seven genera in this ...

'', the class ''Leviviricetes

''Leviviricetes'' is a class of viruses, which infect prokaryotes. Most of these bacteriophages were discovered by metagenomics

Metagenomics is the study of all genetics, genetic material from all organisms in a particular environment, prov ...

'', and possibly the family '' Picobirnaviridae'' contain bacterial viruses.

* In the realm ''Singelaviria

''Singelaviria'' is a realm of viruses that includes all DNA viruses that encode major capsid proteins that contain a single vertical jelly roll fold. All viruses in ''Singelaviria'' have two major capsid proteins (MCPs) that both have a sing ...

'', the family '' Matsushitaviridae'' contains bacterial viruses.

* In the realm ''Varidnaviria

''Varidnaviria'' is a realm of viruses that includes all DNA viruses that encode major capsid proteins that contain two vertical jelly roll folds. The major capsid proteins (MCP) form into pseudohexameric subunits of the viral capsid, which s ...

'', the class '' Ainoaviricetes'', the order '' Vinavirales'', and the subphylum '' Prepoliviricotina'' contain bacterial viruses.

* Lastly, the families '' Obscuriviridae'' and '' Plasmaviridae'', which are unassigned to higher taxa, are bacterial virus families.

The taxonomy of the aforementioned taxa can be visualized as follows, with bacterial virus taxa in bold:

* Realm: ''Duplodnaviria''

** Kingdom: ''Heunggongvirae''

*** Phylum: ''Uroviricota''

**** Class: ''Caudoviricetes

''Caudoviricetes'' is a class of viruses known as tailed viruses and head-tail viruses (''cauda'' is Latin for "tail"). It is the sole representative of its own phylum, ''Uroviricota'' (from ''ouros'' (ουρος), a Greek word for "tailed" + ...

''

* Realm: ''Monodnaviria''

** Kingdom: ''Loebvirae

''Tubulavirales'' is an order of viruses.

Taxonomy

The order contains the following families:

* ''Inoviridae

Filamentous bacteriophages are a family of viruses (''Inoviridae'') that infect bacteria, or bacteriophages. They are named for the ...

''

** Kingdom: ''Sangervirae

''Microviridae'' is a family of bacteriophages with a single-stranded DNA genome. The name of this family is derived from the ancient Greek word (), meaning "small". This refers to the size of their genomes, which are among the smallest of the ...

''

* Realm: ''Riboviria''

** Kingdom: ''Orthornavirae''

*** Phylum: ''Artimaviricota

''Atsuirnavirus'' is a genus of virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, in ...

''

*** Phylum: ''Duplornaviricota''

**** Class: ''Vidaverviricetes

Cystoviruses are a family of double-stranded RNA viruses that infect bacteria. They constitute the family ''Cystoviridae''. The name of the group c''ysto'' derives from Greek ''kystis'' which means bladder or sack. There are seven genera in this ...

''

*** Phylum: ''Lenarviricota''

**** Class: ''Leviviricetes

''Leviviricetes'' is a class of viruses, which infect prokaryotes. Most of these bacteriophages were discovered by metagenomics

Metagenomics is the study of all genetics, genetic material from all organisms in a particular environment, prov ...

''

*** Phylum: ''Pisuviricota''

**** Class: ''Duplopiviricetes''

***** Order: ''Durnavirales''

****** Family: '' Picobirnaviridae''

* Realm: ''Singelaviria''

** Kingdom: ''Helvetiavirae''

*** Phylum: ''Dividoviricota''

**** Class: ''Laserviricetes''

***** Order: ''Halopanivirales''

****** Family: '' Matsushitaviridae''

* Realm: ''Varidnaviria''

** Kingdom: ''Abadenavirae''

*** Phylum: ''Produgelaviricota''

**** Class: '' Ainoaviricetes''

**** Class: ''Belvinaviricetes''

***** Order: '' Vinavirales''

** Kingdom: ''Bamfordvirae''

*** Phylum: ''Preplasmiviricota''

**** Subphylum: '' Prepoliviricotina''

* Unassigned taxa: '' Obscuriviridae'' and '' Plasmaviridae''

History

In 1896, Ernest Hanbury Hankin reported that something in the waters of theGanges

The Ganges ( ; in India: Ganga, ; in Bangladesh: Padma, ). "The Ganges Basin, known in India as the Ganga and in Bangladesh as the Padma, is an international which goes through India, Bangladesh, Nepal and China." is a trans-boundary rive ...

and Yamuna

The Yamuna (; ) is the second-largest tributary river of the Ganges by discharge and the longest tributary in India. Originating from the Yamunotri Glacier at a height of about on the southwestern slopes of Bandarpunch peaks of the Low ...

rivers in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

had a marked antibacterial action against cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

and it could pass through a very fine porcelain filter. In 1915, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

bacteriologist

A bacteriologist is a microbiologist, or similarly trained professional, in bacteriology— a subdivision of microbiology that studies bacteria, typically Pathogenic bacteria, pathogenic ones. Bacteriologists are interested in studying and learnin ...

Frederick Twort

Frederick William Twort FRS (22 October 1877 – 20 March 1950) was an English bacteriologist and was the original discoverer in 1915 of bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria). He studied medicine at St Thomas's Hospital, London, was sup ...

, superintendent of the Brown Institution of London, discovered a small agent that infected and killed bacteria. He believed the agent must be one of the following:

# a stage in the life cycle of the bacteria

# an enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

produced by the bacteria themselves, or

# a virus that grew on and destroyed the bacteria

Twort's research was interrupted by the onset of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, as well as a shortage of funding and the discoveries of antibiotics.

Independently, French-Canadian

French Canadians, referred to as Canadiens mainly before the nineteenth century, are an ethnic group descended from French colonists first arriving in France's colony of Canada in 1608. The vast majority of French Canadians live in the prov ...

microbiologist

A microbiologist (from Greek ) is a scientist who studies microscopic life forms and processes. This includes study of the growth, interactions and characteristics of microscopic organisms such as bacteria, algae, fungi, and some types of par ...

Félix d'Hérelle, working at the Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (, ) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines for anthrax and rabies. Th ...

in Paris, announced on 3 September 1917 that he had discovered "an invisible, antagonistic microbe of the dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

bacillus". For d'Hérelle, there was no question as to the nature of his discovery: "In a flash I had understood: what caused my clear spots was in fact an invisible microbe... a virus parasitic on bacteria." D'Hérelle called the virus a bacteriophage, a bacterium-eater (from the Greek ', meaning "to devour"). He also recorded a dramatic account of a man suffering from dysentery who was restored to good health by the bacteriophages. It was d'Hérelle who conducted much research into bacteriophages and introduced the concept of phage therapy

Phage therapy, viral phage therapy, or phagotherapy is the therapeutic use of bacteriophages for the treatment of pathogenic bacterial infections. This therapeutic approach emerged at the beginning of the 20th century but was progressively r ...

. In 1919, in Paris, France, d'Hérelle conducted the first clinical application of a bacteriophage, with the first reported use in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

being in 1922.

Nobel prizes awarded for phage research

In 1969,Max Delbrück

Max Ludwig Henning Delbrück (; September 4, 1906 – March 9, 1981) was a German–American biophysicist who participated in launching the molecular biology research program in the late 1930s. He stimulated physical science, physical scientist ...

, Alfred Hershey, and Salvador Luria

Salvador Edward Luria (; ; born Salvatore Luria; August 13, 1912 – February 6, 1991) was an Italian microbiologist, later a Naturalized citizen of the United States#Naturalization, naturalized U.S. citizen. He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology ...

were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

for their discoveries of the replication of viruses and their genetic structure. Specifically the work of Hershey, as contributor to the Hershey–Chase experiment in 1952, provided convincing evidence that DNA, not protein, was the genetic material of life. Delbrück and Luria carried out the Luria–Delbrück experiment which demonstrated statistically that mutations in bacteria occur randomly and thus follow Darwinian

''Darwinism'' is a term used to describe a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others. The theory states that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural sele ...

rather than Lamarckian principles.

Uses

Phage therapy

Phages were discovered to be antibacterial agents and were used in the formerSoviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

Republic of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

(pioneered there by Giorgi Eliava with help from the co-discoverer of bacteriophages, Félix d'Hérelle) during the 1920s and 1930s for treating bacterial infections.

D'Herelle "quickly learned that bacteriophages are found wherever bacteria thrive: in sewers, in rivers that catch waste runoff from pipes, and in the stools of convalescent patients."

They had widespread use, including treatment of soldiers in the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

. However, they were abandoned for general use in the West for several reasons:

* Antibiotics were discovered and marketed widely. They were easier to make, store, and prescribe.

* Medical trials of phages were carried out, but a basic lack of understanding of phages raised questions about the validity of these trials.

* Publication of research in the Soviet Union was mainly in the Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

or Georgian language

Georgian (, ) is the most widely spoken Kartvelian language, Kartvelian language family. It is the official language of Georgia (country), Georgia and the native or primary language of 88% of its population. It also serves as the literary langu ...

s and for many years was not followed internationally.

* The Soviet technology was widely discouraged and in some cases illegal due to the red scare

A Red Scare is a form of moral panic provoked by fear of the rise of left-wing ideologies in a society, especially communism and socialism. Historically, red scares have led to mass political persecution, scapegoating, and the ousting of thos ...

.

The use of phages has continued since the end of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

in Russia, Georgia, and elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe. The first regulated, randomized, double-blind clinical trial

Clinical trials are prospective biomedical or behavioral research studies on human subject research, human participants designed to answer specific questions about biomedical or behavioral interventions, including new treatments (such as novel v ...

was reported in the ''Journal of Wound Care'' in June 2009, which evaluated the safety and efficacy of a bacteriophage cocktail to treat infected venous ulcers of the leg in human patients. The FDA approved the study as a Phase I clinical trial. The study's results demonstrated the safety of therapeutic application of bacteriophages, but did not show efficacy. The authors explained that the use of certain chemicals that are part of standard wound care (e.g. lactoferrin

Lactoferrin (LF), also known as lactotransferrin (LTF), is a multifunctional protein of the transferrin family. Lactoferrin is a globular proteins, globular glycoprotein with a molecular mass of about 80 Atomic mass unit, kDa that is widely repre ...

or silver) may have interfered with bacteriophage viability. Shortly after that, another controlled clinical trial in Western Europe (treatment of ear infections caused by ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'') was reported in the journal ''Clinical Otolaryngology

''Clinical Otolaryngology'' is a bimonthly peer-reviewed medical journal covering the field of otorhinolaryngology. It was established in 1976 as ''Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences'', obtaining its current title in 2005. It is published ...

'' in August 2009. The study concludes that bacteriophage preparations were safe and effective for treatment of chronic ear infections in humans. Additionally, there have been numerous animal and other experimental clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of bacteriophages for various diseases, such as infected burns and wounds, and cystic fibrosis-associated lung infections, among others. On the other hand, phages of ''Inoviridae

Filamentous bacteriophages are a family of viruses (''Inoviridae'') that infect bacteria, or bacteriophages. They are named for their filamentous shape, a worm-like chain (long, thin, and flexible, reminiscent of a length of cooked spaghetti), ...

'' have been shown to complicate biofilms

A biofilm is a syntrophic community of microorganisms in which cells stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy extracellular matrix that is composed of extracellular polymer ...

involved in pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

and cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner that impairs the normal clearance of Sputum, mucus from the lungs, which facilitates the colonization and infection of the lungs by bacteria, notably ''Staphy ...

and to shelter the bacteria from drugs meant to eradicate disease, thus promoting persistent infection.

Meanwhile, bacteriophage researchers have been developing engineered viruses to overcome antibiotic resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR or AR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from antimicrobials, which are drugs used to treat infections. This resistance affects all classes of microbes, including bacteria (antibiotic resis ...

, and engineering the phage genes responsible for coding enzymes that degrade the biofilm matrix, phage structural proteins, and the enzymes responsible for lysis

Lysis ( ; from Greek 'loosening') is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ...

of the bacterial cell wall. There have been results showing that T4 phages that are small in size and short-tailed can be helpful in detecting ''E. coli'' in the human body.

Therapeutic efficacy of a phage cocktail was evaluated in a mouse model with nasal infection of multi-drug-resistant (MDR) ''A. baumannii

''Acinetobacter baumannii'' is a typically short, almost round, rod-shaped (coccobacillus) Gram-negative bacterium. It is named after the bacteriologist Paul Baumann. It can be an opportunistic pathogen in humans, affecting people with compromise ...

''. Mice treated with the phage cocktail showed a 2.3-fold higher survival rate compared to those untreated at seven days post-infection.

In 2017, a 68-year-old diabetic patient with necrotizing pancreatitis complicated by a pseudocyst infected with MDR ''A. baumannii'' strains was being treated with a cocktail of Azithromycin, Rifampicin, and Colistin for 4 months without results and overall rapidly declining health.

Because discussion had begun of the clinical futility of further treatment, an Emergency Investigational New Drug (eIND) was filed as a last effort to at the very least gain valuable medical data from the situation, and approved, so he was subjected to phage therapy using a percutaneously (PC) injected cocktail containing nine different phages that had been identified as effective against the primary infection strain by rapid isolation and testing techniques (a process which took under a day). This proved effective for a very brief period, although the patient remained unresponsive and his health continued to worsen; soon isolates of a strain of ''A. baumannii'' were being collected from drainage of the cyst that showed resistance to this cocktail, and a second cocktail which was tested to be effective against this new strain was added, this time by intravenous (IV) injection as it had become clear that the infection was more pervasive than originally thought.

Once on the combination of the IV and PC therapy the patient's downward clinical trajectory reversed, and within two days he had awoken from his coma and become responsive. As his immune system began to function he had to be temporarily removed from the cocktail because his fever was spiking to over , but after two days the phage cocktails were re-introduced at levels he was able to tolerate. The original three-antibiotic cocktail was replaced by minocycline after the bacterial strain was found not to be resistant to this and he rapidly regained full lucidity, although he was not discharged from the hospital until roughly 145 days after phage therapy began. Towards the end of the therapy it was discovered that the bacteria had become resistant to both of the original phage cocktails, but they were continued because they seemed to be preventing minocycline resistance from developing in the bacterial samples collected so were having a useful synergistic effect.

Other

Food industry

Phages have increasingly been used to safen food products and to forestall spoilage bacteria. Since 2006, theUnited States Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respo ...

(FDA) and United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is an executive department of the United States federal government that aims to meet the needs of commercial farming and livestock food production, promotes agricultural trade and producti ...

(USDA) have approved several bacteriophage products. LMP-102 (Intralytix) was approved for treating ready-to-eat (RTE) poultry and meat products. In that same year, the FDA approved LISTEX (developed and produced by Micreos) using bacteriophages on cheese to kill ''Listeria monocytogenes

''Listeria monocytogenes'' is the species of pathogenic bacteria that causes the infection listeriosis. It is a facultative anaerobic bacterium, capable of surviving in the presence or absence of oxygen. It can grow and reproduce inside the ho ...

'' bacteria, in order to give them generally recognized as safe

Generally recognized as safe (GRAS) is a United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) designation that a chemical or substance added to food is considered safe by experts under the conditions of its intended use. An ingredient with a GRAS d ...

(GRAS) status. In July 2007, the same bacteriophage were approved for use on all food products. In 2011 USDA confirmed that LISTEX is a clean label processing aid and is included in USDA. Research in the field of food safety is continuing to see if lytic phages are a viable option to control other food-borne pathogens in various food products.

Water indicators

Bacteriophages, including those specific to ''Escherichia coli'', have been employed as indicators of fecal contamination in water sources. Due to their shared structural and biological characteristics, coliphages can serve as proxies for viral fecal contamination and the presence of pathogenic viruses such as rotavirus, norovirus, and HAV. Research conducted on wastewater treatment systems has revealed significant disparities in the behavior of coliphages compared to fecal coliforms, demonstrating a distinct correlation with the recovery of pathogenic viruses at the treatment's conclusion. Establishing a secure discharge threshold, studies have determined that discharges below 3000 PFU/100 mL are considered safe in terms of limiting the release of pathogenic viruses.Diagnostics

In 2011, the FDA cleared the first bacteriophage-based product for in vitro diagnostic use. The KeyPath MRSA/MSSA Blood Culture Test uses a cocktail of bacteriophage to detect ''Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often posi ...

'' in positive blood cultures and determine methicillin

Methicillin ( USAN), also known as meticillin ( INN), is a narrow-spectrum β-lactam antibiotic of the penicillin class.

Methicillin was discovered in 1960.

Medical uses

Compared to other penicillins that face antimicrobial resistance ...

resistance or susceptibility. The test returns results in about five hours, compared to two to three days for standard microbial identification and susceptibility test methods. It was the first accelerated antibiotic-susceptibility test approved by the FDA.

Counteracting bioweapons and toxins

Government agencies in the West have for several years been looking toGeorgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

and the former Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

for help with exploiting phages for counteracting bioweapons and toxins, such as anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Bacillus anthracis'' or ''Bacillus cereus'' biovar ''anthracis''. Infection typically occurs by contact with the skin, inhalation, or intestinal absorption. Symptom onset occurs between one ...

and botulism

Botulism is a rare and potentially fatal illness caused by botulinum toxin, which is produced by the bacterium ''Clostridium botulinum''. The disease begins with weakness, blurred vision, Fatigue (medical), feeling tired, and trouble speaking. ...

. Developments are continuing among research groups in the U.S. Other uses include spray application in horticulture for protecting plants and vegetable produce from decay and the spread of bacterial disease. Other applications for bacteriophages are as biocides for environmental surfaces, e.g., in hospitals, and as preventative treatments for catheters and medical devices before use in clinical settings. The technology for phages to be applied to dry surfaces, e.g., uniforms, curtains, or even sutures for surgery now exists. Clinical trials reported in ''Clinical Otolaryngology'' show success in veterinary treatment of pet dogs with otitis

Otitis is a general term for inflammation in ear or ear infection, inner ear infection, middle ear infection of the ear, in both humans and other animals. When infection is present, it may be viral or bacterial. When inflammation is present due t ...

.

Bacterium sensing and identification

The sensing of phage-triggered ion cascades (SEPTIC) bacterium sensing and identification method uses the ion emission and its dynamics during phage infection and offers high specificity and speed for detection.Phage display

Phage display

Phage display is a laboratory technique for the study of protein–protein, protein–peptide, and protein–DNA interactions that uses bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) to connect proteins with the genetic information that encodes ...

is a different use of phages involving a library of phages with a variable peptide linked to a surface protein. Each phage genome encodes the variant of the protein displayed on its surface (hence the name), providing a link between the peptide variant and its encoding gene. Variant phages from the library may be selected through their binding affinity to an immobilized molecule (e.g., botulism toxin) to neutralize it. The bound, selected phages can be multiplied by reinfecting a susceptible bacterial strain, thus allowing them to retrieve the peptides encoded in them for further study.

Antimicrobial drug discovery

Phage proteins often have antimicrobial activity and may serve as leads forpeptidomimetic

A peptidomimetic is a small protein-like chain designed to mimic a peptide. They typically arise either from modification of an existing peptide, or by designing similar systems that mimic peptides, such as peptoids and β-peptides. Irrespective ...

s, i.e. drugs that mimic peptides. Phage-ligand technology makes use of phage proteins for various applications, such as binding of bacteria and bacterial components (e.g. endotoxin

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), now more commonly known as endotoxin, is a collective term for components of the outermost membrane of the cell envelope of gram-negative bacteria, such as '' E. coli'' and ''Salmonella'' with a common structural archit ...

) and lysis of bacteria.

Basic research

Bacteriophages are importantmodel organisms

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

for studying principles of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

and ecology

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their Natural environment, environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosystem, and biosphere lev ...

.

Detriments

Dairy industry

Bacteriophages present in the environment can cause cheese to not ferment. In order to avoid this, mixed-strain starter cultures and culture rotation regimes can be used.Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of Genetic engineering techniques, technologies used to change the genet ...

of culture microbes – especially '' Lactococcus lactis'' and ''Streptococcus thermophilus

''Streptococcus thermophilus'' formerly known as ''Streptococcus salivarius ''subsp.'' thermophilus'' is a gram-positive bacteria, gram-positive bacterium, and a lactic acid fermentation, fermentative facultative anaerobic organism, facultative ...

'' – have been studied for genetic analysis and modification to improve phage resistance. This has especially focused on plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and ...

and recombinant chromosomal modifications.

Some research has focused on the potential of bacteriophages as antimicrobial against foodborne pathogens and biofilm formation within the dairy industry. As the spread of antibiotic resistance is a main concern within the dairy industry, phages can serve as a promising alternative.

Replication

The life cycle of bacteriophages tends to be either a lytic cycle or a

The life cycle of bacteriophages tends to be either a lytic cycle or a lysogenic cycle

Lysogeny, or the lysogenic cycle, is one of two cycles of Virus, viral reproduction (the lytic cycle being the other). Lysogeny is characterized by integration of the bacteriophage nucleic acid into the host Bacteria, bacterium's genome or form ...

. In addition, some phages display pseudolysogenic behaviors.

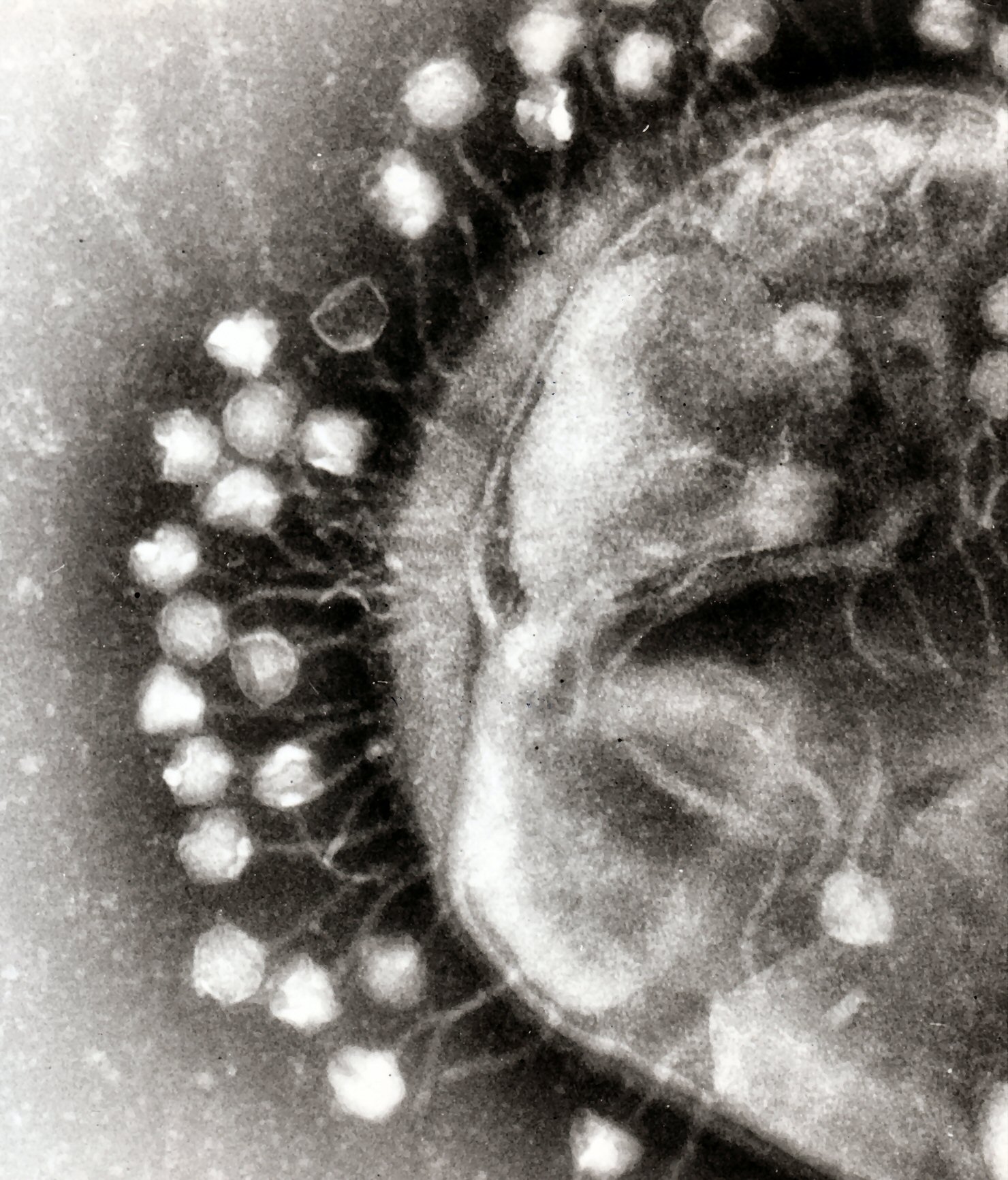

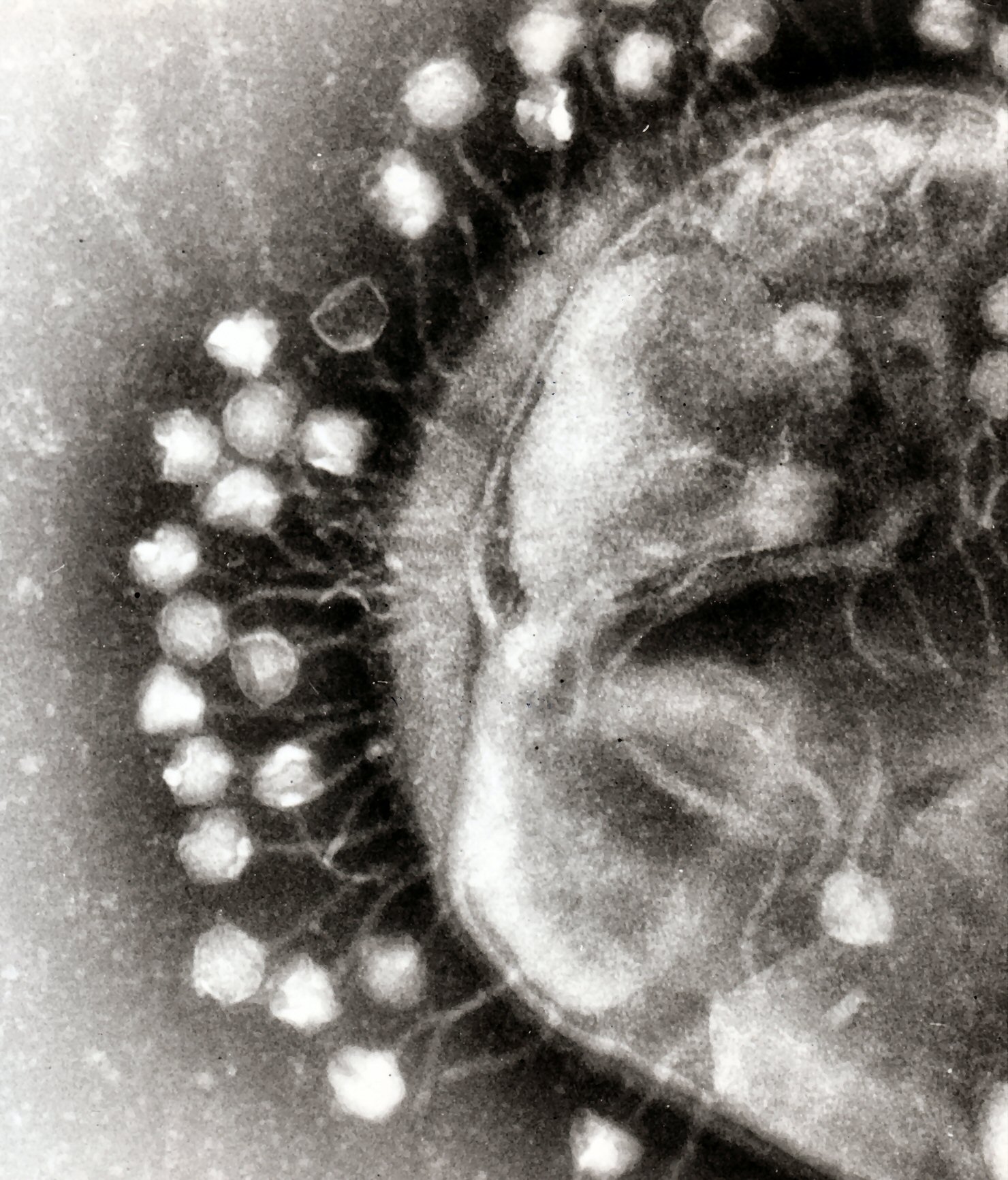

With ''lytic phages'' such as the T4 phage, bacterial cells are broken open (lysed) and destroyed after immediate replication of the virion. As soon as the cell is destroyed, the phage progeny can find new hosts to infect. Lytic phages are more suitable for phage therapy

Phage therapy, viral phage therapy, or phagotherapy is the therapeutic use of bacteriophages for the treatment of pathogenic bacterial infections. This therapeutic approach emerged at the beginning of the 20th century but was progressively r ...

. Some lytic phages undergo a phenomenon known as lysis inhibition, where completed phage progeny will not immediately lyse out of the cell if extracellular phage concentrations are high. This mechanism is not identical to that of the temperate phage going dormant and usually is temporary.

In contrast, the ''lysogenic cycle

Lysogeny, or the lysogenic cycle, is one of two cycles of Virus, viral reproduction (the lytic cycle being the other). Lysogeny is characterized by integration of the bacteriophage nucleic acid into the host Bacteria, bacterium's genome or form ...

'' does not result in immediate lysing of the host cell. Those phages able to undergo lysogeny are known as temperate phages. Their viral genome will integrate with host DNA and replicate along with it, relatively harmlessly, or may even become established as a plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and ...

. The virus remains dormant until host conditions deteriorate, perhaps due to depletion of nutrients, then, the endogenous

Endogeny, in biology, refers to the property of originating or developing from within an organism, tissue, or cell.

For example, ''endogenous substances'', and ''endogenous processes'' are those that originate within a living system (e.g. an ...

phages (known as prophage

A prophage is a bacteriophage (often shortened to "phage") genome that is integrated into the circular bacterial chromosome or exists as an extrachromosomal plasmid within the bacterial cell (biology), cell. Integration of prophages into the bacte ...

s) become active. At this point they initiate the reproductive cycle, resulting in lysis of the host cell. As the lysogenic cycle allows the host cell to continue to survive and reproduce, the virus is replicated in all offspring of the cell. An example of a bacteriophage known to follow the lysogenic cycle and the lytic cycle is the phage lambda of ''E. coli.''

Sometimes prophages may provide benefits to the host bacterium while they are dormant by adding new functions to the bacterial genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

, in a phenomenon called lysogenic conversion. Examples are the conversion of harmless strains of ''Corynebacterium diphtheriae

''Corynebacterium diphtheriae'' is a Gram-positive pathogenic bacterium that causes diphtheria. It is also known as the Klebs–Löffler bacillus because it was discovered in 1884 by German bacteriologists Edwin Klebs (1834–1912) and Friedrich ...

'' or ''Vibrio cholerae

''Vibrio cholerae'' is a species of Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-negative, Facultative anaerobic organism, facultative anaerobe and Vibrio, comma-shaped bacteria. The bacteria naturally live in Brackish water, brackish or saltwater where they att ...

'' by bacteriophages to highly virulent ones that cause diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacteria, bacterium ''Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild Course (medicine), clinical course, but in some outbreaks, the mortality rate approaches 10%. Signs a ...

or cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

, respectively. Strategies to combat certain bacterial infections by targeting these toxin-encoding prophages have been proposed.

Attachment and penetration

Bacterial cells are protected by a cell wall of

Bacterial cells are protected by a cell wall of polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s, which are important virulence factors protecting bacterial cells against both immune host defenses and antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

s.

Host growth conditions also influence the ability of the phage to attach and invade them. As phage virions do not move independently, they must rely on random encounters with the correct receptors when in solution, such as blood, lymphatic circulation, irrigation, soil water, etc.

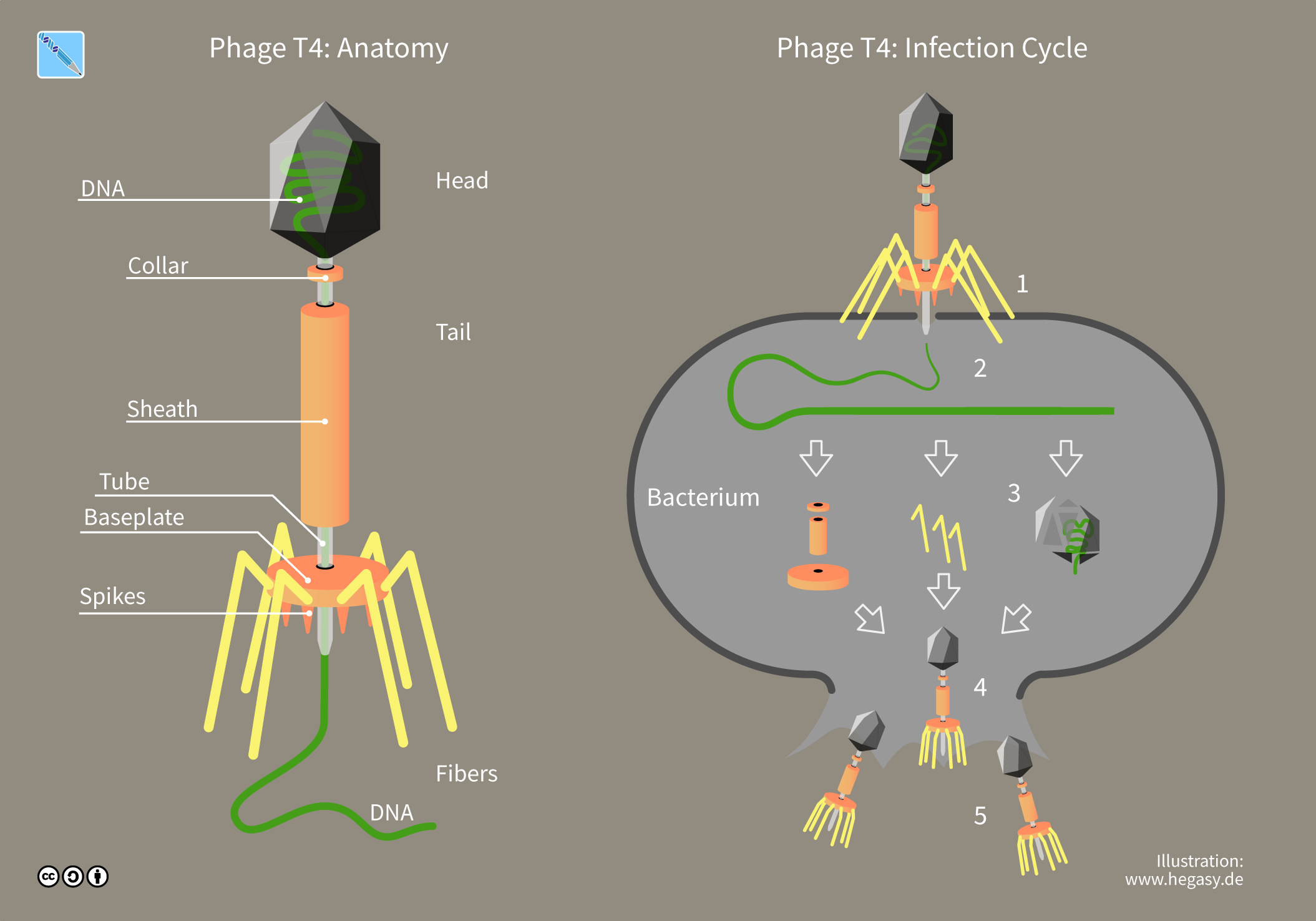

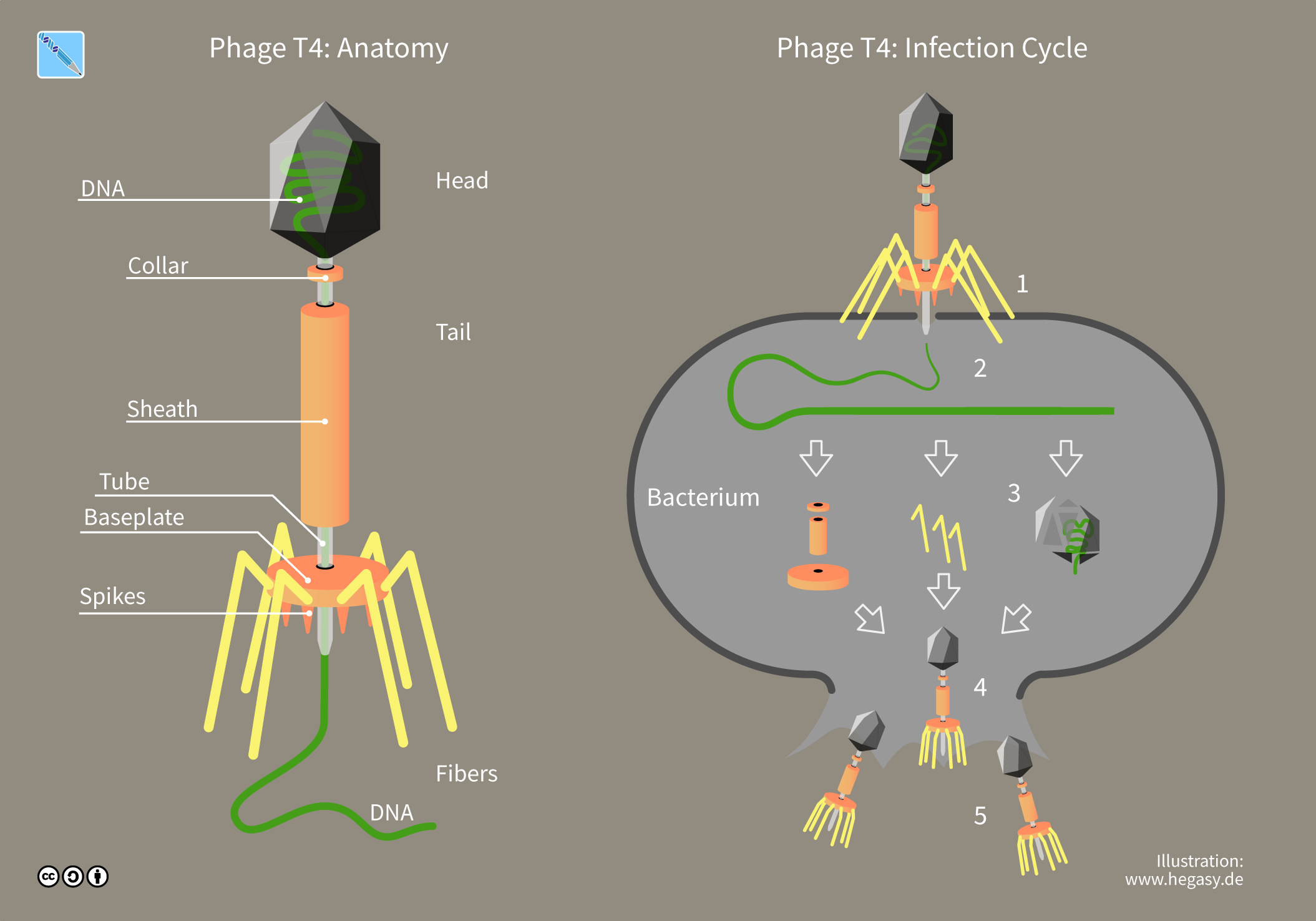

Myovirus bacteriophages use a hypodermic syringe

A syringe is a simple reciprocating pump consisting of a plunger (though in modern syringes, it is actually a piston) that fits tightly within a cylindrical tube called a barrel. The plunger can be linearly pulled and pushed along the insid ...

-like motion to inject their genetic material into the cell. After contacting the appropriate receptor, the tail fibers flex to bring the base plate closer to the surface of the cell. This is known as reversible binding. Once attached completely, irreversible binding is initiated and the tail contracts, possibly with the help of ATP present in the tail, injecting genetic material through the bacterial membrane. The injection is accomplished through a sort of bending motion in the shaft by going to the side, contracting closer to the cell and pushing back up. Podoviruses lack an elongated tail sheath like that of a myovirus, so instead, they use their small, tooth-like tail fibers enzymatically to degrade a portion of the cell membrane before inserting their genetic material.

Synthesis of proteins and nucleic acid

Within minutes, bacterialribosome

Ribosomes () are molecular machine, macromolecular machines, found within all cell (biology), cells, that perform Translation (biology), biological protein synthesis (messenger RNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order s ...

s start translating viral mRNA into protein. For RNA-based phages, RNA replicase

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) or RNA replicase is an enzyme that catalyzes the replication of RNA from an RNA template. Specifically, it catalyzes synthesis of the RNA strand complementary to a given RNA template. This is in contrast to ...

is synthesized early in the process. Proteins modify the bacterial RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reactions that synthesize RNA from a DNA template.

Using the e ...

so it preferentially transcribes viral mRNA. The host's normal synthesis of proteins and nucleic acids is disrupted, and it is forced to manufacture viral products instead. These products go on to become part of new virions within the cell, helper proteins that contribute to the assemblage of new virions, or proteins involved in cell lysis

Lysis ( ; from Greek 'loosening') is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ...

. In 1972, Walter Fiers (University of Ghent

Ghent University (, abbreviated as UGent) is a Public university, public research university located in Ghent, in the East Flanders province of Belgium.

Located in Flanders, Ghent University is the second largest Belgian university, consisting o ...

, Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

) was the first to establish the complete nucleotide sequence of a gene and in 1976, of the viral genome of bacteriophage MS2

Bacteriophage MS2 (''Emesvirus zinderi''), commonly called MS2, is an icosahedral, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus that infects the bacterium ''Escherichia coli'' and other members of the Enterobacteriaceae. MS2 is a member of a family ...

. Some dsDNA bacteriophages encode ribosomal proteins, which are thought to modulate protein translation during phage infection.

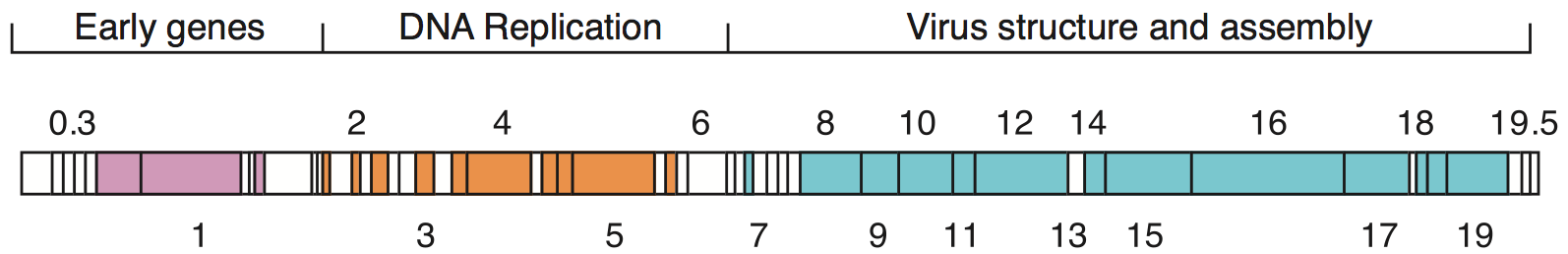

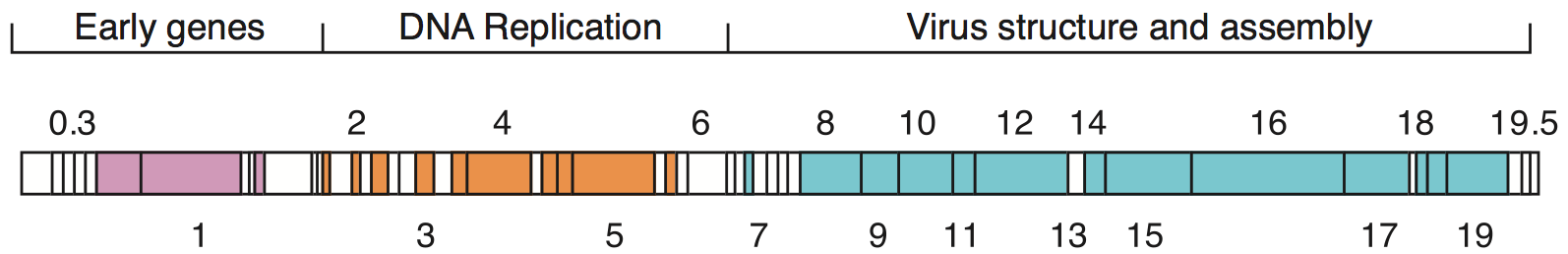

Virion assembly

In the case of the T4 phage, the construction of new virus particles involves the assistance of helper proteins that act catalytically during phagemorphogenesis

Morphogenesis (from the Greek ''morphê'' shape and ''genesis'' creation, literally "the generation of form") is the biological process that causes a cell, tissue or organism to develop its shape. It is one of three fundamental aspects of deve ...

. The base plates are assembled first, with the tails being built upon them afterward. The head capsids, constructed separately, will spontaneously assemble with the tails. During assembly of the phage T4 virion

A virion (plural, ''viria'' or ''virions'') is an inert virus particle capable of invading a Cell (biology), cell. Upon entering the cell, the virion disassembles and the genetic material from the virus takes control of the cell infrastructure, t ...

, the morphogenetic proteins encoded by the phage gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s interact with each other in a characteristic sequence. Maintaining an appropriate balance in the amounts of each of these proteins produced during viral infection appears to be critical for normal phage T4 morphogenesis

Morphogenesis (from the Greek ''morphê'' shape and ''genesis'' creation, literally "the generation of form") is the biological process that causes a cell, tissue or organism to develop its shape. It is one of three fundamental aspects of deve ...

. The DNA is packed efficiently within the heads. The whole process takes about 15 minutes.

Early studies of bactioriophage T4 (1962–1964) provided an opportunity to gain understanding of virtually all of the genes that are essential for growth of the bacteriophage under laboratory conditions. These studies were made possible by the availability of two classes of conditional lethal mutants. One class of such mutants was referred to as amber mutants. The other class of conditional lethal mutants was referred to as temperature-sensitive mutants Studies of these two classes of mutants led to considerable insight into the functions and interactions of the proteins employed in the machinery of DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all life, living organisms, acting as the most essential part of heredity, biolog ...

, repair

The technical meaning of maintenance involves functional checks, servicing, repairing or replacing of necessary devices, equipment, machinery, building infrastructure and supporting utilities in industrial, business, and residential installat ...

and recombination, and on how viruses are assembled from protein and nucleic acid components (molecular morphogenesis

Morphogenesis (from the Greek ''morphê'' shape and ''genesis'' creation, literally "the generation of form") is the biological process that causes a cell, tissue or organism to develop its shape. It is one of three fundamental aspects of deve ...

).

Release of virions

Phages may be released via cell lysis, by extrusion, or, in a few cases, by budding. Lysis, by tailed phages, is achieved by an enzyme called endolysin, which attacks and breaks down the cell wallpeptidoglycan

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer (sacculus) that surrounds the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. The sugar component consists of alternating ...

. An altogether different phage type, the filamentous phage, makes the host cell continually secrete new virus particles. Released virions are described as free, and, unless defective, are capable of infecting a new bacterium. Budding is associated with certain ''Mycoplasma

''Mycoplasma'' is a genus of bacteria that, like the other members of the class ''Mollicutes'', lack a cell wall, and its peptidoglycan, around their cell membrane. The absence of peptidoglycan makes them naturally resistant to antibiotics ...

'' phages. In contrast to virion release, phages displaying a lysogenic cycle do not kill the host and instead become long-term residents as prophage

A prophage is a bacteriophage (often shortened to "phage") genome that is integrated into the circular bacterial chromosome or exists as an extrachromosomal plasmid within the bacterial cell (biology), cell. Integration of prophages into the bacte ...

s.

Communication

Research in 2017 revealed that the bacteriophage Φ3T makes a short viral protein that signals other bacteriophages to lie dormant instead of killing the host bacterium.Arbitrium

Arbitrium is a viral peptide produced by bacteriophages to communicate with each other and decide host cell fate. It is six amino acids(aa) long, and so is also referred to as a hexapeptide. It is produced when a phage infects a bacterial host. a ...

is the name given to this protein by the researchers who discovered it.

Genome structure

Given the millions of different phages in the environment, phage genomes come in a variety of forms and sizes. RNA phages such as MS2 have the smallest genomes, with only a few kilobases. However, some DNA phages such as T4 may have large genomes with hundreds of genes; the size and shape of thecapsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or m ...

varies along with the size of the genome. The largest bacteriophage genomes reach a size of 735 kb. Bacteriophage genomes can be highly

Bacteriophage genomes can be highly mosaic

A mosaic () is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/Mortar (masonry), mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and ...

, i.e. the genome of many phage species appear to be composed of numerous individual modules. These modules may be found in other phage species in different arrangements. Mycobacteriophages, bacteriophages with mycobacteria

''Mycobacterium'' is a genus of over 190 species in the phylum Actinomycetota, assigned its own family, Mycobacteriaceae. This genus includes pathogens known to cause serious diseases in mammals, including tuberculosis ('' M. tuberculosis'') a ...

l hosts, have provided excellent examples of this mosaicism. In these mycobacteriophages, genetic assortment may be the result of repeated instances of site-specific recombination Site-specific recombination, also known as conservative site-specific recombination, is a type of genetic recombination in which DNA strand exchange takes place between segments possessing at least a certain degree of sequence homology. Enzymes know ...

and illegitimate recombination (the result of phage genome acquisition of bacterial host genetic sequences). Evolutionary mechanisms shaping the genomes of bacterial viruses vary between different families and depend upon the type of the nucleic acid, characteristics of the virion structure, as well as the mode of the viral life cycle.

Some marine roseobacter phages, also known as roseophages, contain deoxyuridine (dU) instead of deoxythymidine (dT) in their genomic DNA. There is some evidence that this unusual component is a mechanism to evade bacterial defense mechanisms such as restriction endonucleases and CRISPR/Cas systems which evolved to recognize and cleave sequences within invading phages, thereby inactivating them. Other phages have long been known to use unusual nucleotides. In 1963, Takahashi and Marmur identified a ''Bacillus

''Bacillus'', from Latin "bacillus", meaning "little staff, wand", is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria, a member of the phylum ''Bacillota'', with 266 named species. The term is also used to describe the shape (rod) of other so-sh ...

'' phage that has dU substituting dT in its genome, and in 1977, Kirnos et al. identified a cyanophage containing 2-aminoadenine (Z) instead of adenine (A).

Systems biology

The field ofsystems biology

Systems biology is the computational modeling, computational and mathematical analysis and modeling of complex biological systems. It is a biology-based interdisciplinary field of study that focuses on complex interactions within biological system ...

investigates the complex networks of interactions within an organism, usually using computational tools and modeling. For example, a phage genome that enters into a bacterial host cell may express hundreds of phage proteins which will affect the expression of numerous host genes or the host's metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

. All of these complex interactions can be described and simulated in computer models.

For instance, infection of ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common Bacterial capsule, encapsulated, Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-negative, Aerobic organism, aerobic–facultative anaerobe, facultatively anaerobic, Bacillus (shape), rod-shaped bacteria, bacterium that can c ...

'' by the temperate phage PaP3 changed the expression of 38% (2160/5633) of its host's genes. Many of these effects are probably indirect, hence the challenge becomes to identify the direct interactions among bacteria and phage.

Several attempts have been made to map protein–protein interaction

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) are physical contacts of high specificity established between two or more protein molecules as a result of biochemical events steered by interactions that include electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonding and t ...

s among phage and their host. For instance, bacteriophage lambda was found to interact with its host, ''E. coli'', by dozens of interactions. Again, the significance of many of these interactions remains unclear, but these studies suggest that there most likely are several key interactions and many indirect interactions whose role remains uncharacterized.

Host resistance

Bacteriophages are a major threat to bacteria and prokaryotes have evolved numerous mechanisms to block infection or to block the replication of bacteriophages within host cells. The CRISPR system is one such mechanism as areretron

A retron is a distinct DNA sequence found in the genome of many bacteria species that codes for reverse transcriptase and a unique single-stranded DNA/RNA hybrid called multicopy single-stranded DNA (msDNA). Retron msr RNA is the non-coding RNA p ...

s and the anti-toxin system encoded by them. The Thoeris defense system is known to deploy a unique strategy for bacterial antiphage resistance via NAD+

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a coenzyme central to metabolism. Found in all living cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an ade ...

degradation.

Bacteriophage–host symbiosis

Temperate phages are bacteriophages that integrate their genetic material into the host as extrachromosomal episomes or as aprophage

A prophage is a bacteriophage (often shortened to "phage") genome that is integrated into the circular bacterial chromosome or exists as an extrachromosomal plasmid within the bacterial cell (biology), cell. Integration of prophages into the bacte ...

during a lysogenic cycle

Lysogeny, or the lysogenic cycle, is one of two cycles of Virus, viral reproduction (the lytic cycle being the other). Lysogeny is characterized by integration of the bacteriophage nucleic acid into the host Bacteria, bacterium's genome or form ...

. Some temperate phages can confer fitness advantages to their host in numerous ways, including giving antibiotic resistance through the transfer or introduction of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), protecting hosts from phagocytosis, protecting hosts from secondary infection through superinfection exclusion, enhancing host pathogenicity, or enhancing bacterial metabolism or growth. Bacteriophage–host symbiosis may benefit bacteria by providing selective advantages while passively replicating the phage genome.

In the environment

Metagenomics

Metagenomics is the study of all genetics, genetic material from all organisms in a particular environment, providing insights into their composition, diversity, and functional potential. Metagenomics has allowed researchers to profile the mic ...

has allowed the in-water detection of bacteriophages that was not possible previously.

Also, bacteriophages have been used in hydrological

Hydrology () is the scientific study of the movement, distribution, and management of water on Earth and other planets, including the water cycle, water resources, and drainage basin sustainability. A practitioner of hydrology is called a hydro ...

tracing and modelling in river

A river is a natural stream of fresh water that flows on land or inside Subterranean river, caves towards another body of water at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. A river may run dry before reaching the end of ...

systems, especially where surface water and groundwater

Groundwater is the water present beneath Earth's surface in rock and Pore space in soil, soil pore spaces and in the fractures of stratum, rock formations. About 30 percent of all readily available fresh water in the world is groundwater. A unit ...

interactions occur. The use of phages is preferred to the more conventional dye

Juan de Guillebon, better known by his stage name DyE, is a French musician. He is known for the music video of the single "Fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction that involves supernatural or Magic (supernatural), magical ele ...

marker because they are significantly less absorbed when passing through ground waters and they are readily detected at very low concentrations. Non-polluted water may contain approximately 2×108 bacteriophages per ml.

Bacteriophages are thought to contribute extensively to horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

in natural environments, principally via transduction, but also via transformation. Metagenomics-based studies also have revealed that viromes from a variety of environments harbor antibiotic-resistance genes, including those that could confer multidrug resistance

Multiple drug resistance (MDR), multidrug resistance or multiresistance is antimicrobial resistance shown by a species of microorganism to at least one antimicrobial drug in three or more antimicrobial categories. Antimicrobial categories are ...

.

Recent findings have mapped the complex and intertwined arsenal of anti-phage defense tools in environmental bacteria.

In humans

Although phages do not infect humans, there are countless phage particles in the human body, given the extensivehuman microbiome

The human microbiome is the aggregate of all microbiota that reside on or within human tissues and biofluids along with the corresponding List of human anatomical features, anatomical sites in which they reside, including the human gastrointes ...

. One's phage population has been called the human phageome, including the "healthy gut phageome" (HGP) and the "diseased human phageome" (DHP). The active phageome of a healthy human (i.e., actively replicating as opposed to nonreplicating, integrated prophage

A prophage is a bacteriophage (often shortened to "phage") genome that is integrated into the circular bacterial chromosome or exists as an extrachromosomal plasmid within the bacterial cell (biology), cell. Integration of prophages into the bacte ...

) has been estimated to comprise dozens to thousands of different viruses.

There is evidence that bacteriophages and bacteria interact in the human gut microbiome both antagonistically and beneficially.

Preliminary studies have indicated that common bacteriophages are found in 62% of healthy individuals on average, while their prevalence was reduced by 42% and 54% on average in patients with ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of the two types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with the other type being Crohn's disease. It is a long-term condition that results in inflammation and ulcers of the colon and rectum. The primary sympto ...

(UC) and Crohn's disease

Crohn's disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that may affect any segment of the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms often include abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, abdominal distension, and weight loss. Complications outside of the ...

(CD). Abundance of phages may also decline in the elderly.

The most common phages in the human intestine, found worldwide, are crAssphages. CrAssphages are transmitted from mother to child soon after birth, and there is some evidence suggesting that they may be transmitted locally. Each person develops their own unique crAssphage clusters. CrAss-like phages also may be present in primates

Primates is an order of mammals, which is further divided into the strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and lorisids; and the haplorhines, which include tarsiers and simians ( monkeys and apes). Primates arose 74–63 ...

besides humans.

Commonly studied bacteriophages

Among the countless phages, only a few have been studied in detail, including some historically important phage that were discovered in the early days of microbial genetics. These, especially the T-phage, helped to discover important principles of gene structure and function. * 186 phage *λ phage

Lambda phage (coliphage λ, scientific name ''Lambdavirus lambda'') is a bacterial virus, or bacteriophage, that infects the bacterial species ''Escherichia coli'' (''E. coli''). It was discovered by Esther Lederberg in 1950. The wild type of ...

* Φ6 phage

* Φ29 phage

* ΦX174

* Bacteriophage φCb5

* G4 phage

* M13 phage

* MS2 phage (23–28 nm in size)

* N4 phage

* P1 phage

* P2 phage

* P4 phage

* R17 phage

* T2 phage

* T4 phage (169 kbp genome, 200 nm long)

* T7 phage

Bacteriophage T7 (or the T7 phage) is a bacteriophage, a virus that infects bacteria. It infects most strains of ''Escherichia coli'' and relies on these hosts to propagate. Bacteriophage T7 has a Lytic cycle, lytic life cycle, meaning that it ...

* T12 phage

Bacteriophage databases and resources

* Phagesdb * PhagescopeSee also

*Antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

* Bacterivore

A bacterivore is an organism which obtains energy and nutrients primarily or entirely from the consumption of bacteria. The term is most commonly used to describe free-living, heterotrophic, microscopic organisms such as nematodes as well as many s ...

* CrAssphage

* CRISPR

CRISPR (; acronym of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is a family of DNA sequences found in the genomes of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea. Each sequence within an individual prokaryotic CRISPR is d ...

* DNA viruses

* Macrophage

Macrophages (; abbreviated MPhi, φ, MΦ or MP) are a type of white blood cell of the innate immune system that engulf and digest pathogens, such as cancer cells, microbes, cellular debris and foreign substances, which do not have proteins that ...

* Phage ecology

* Phage monographs Bacteriophage (phage) are viruses of bacteria and arguably are Phage ecology#Vastness of phage ecology, the most numerous "organisms" on Earth. The history of phage study is captured, in part, in the books published on the topic. This is a list of o ...

(a comprehensive listing of phage and phage-associated monographs, 1921–present)

* Phagemid

* Polyphage

* RNA viruses

* Transduction

* Viriome

* Virophage

Virophages are small, double-stranded DNA viral phages that require the co-infection of another virus. The co-infecting viruses are typically giant viruses. Virophages rely on the viral replication factory of the co-infecting giant virus for t ...

, viruses that infect other viruses

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * *External links

* * * * * * * {{Authority control