Australian Pitcher Plant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Cephalotus'' ( or ; Greek: ''κεφαλή'' "head", and ''οὔς''/''ὠτός'' "ear", to describe the head of the anthers) is a

The upper third, or the upper half of the trap leaf, is finely beset with glands. In the lower part of the trap there are two kidney-shaped, red-coloured spots that are densely covered with larger glands. These glands most likely produce the liquid in the can, as well as the digestive enzymes and also absorb the nutrients from the prey.

The upper third, or the upper half of the trap leaf, is finely beset with glands. In the lower part of the trap there are two kidney-shaped, red-coloured spots that are densely covered with larger glands. These glands most likely produce the liquid in the can, as well as the digestive enzymes and also absorb the nutrients from the prey.

The plant occurs in southern coastal districts of the Southwest botanical province in Australia; it has been recorded in the

The plant occurs in southern coastal districts of the Southwest botanical province in Australia; it has been recorded in the

The plant is

The plant is

''Cephalotus'' are cultivated worldwide. In the wild, they prefer warm day-time temperatures of up to 25 degrees Celsius during the growing season, coupled with cool night-time temperatures. It is commonly grown in a mixture of sphagnum peat moss,

''Cephalotus'' are cultivated worldwide. In the wild, they prefer warm day-time temperatures of up to 25 degrees Celsius during the growing season, coupled with cool night-time temperatures. It is commonly grown in a mixture of sphagnum peat moss,  There are several dozen ''Cephalotus'' clones that exist in cultivation; nine have been officially registered as

There are several dozen ''Cephalotus'' clones that exist in cultivation; nine have been officially registered as

File:Cephalotus follicularis Hennern 2.jpg, ''Cephalotus follicularis''

Inner World of ''Cephalotus follicularis'' from the John Innes Centre

* {{Taxonbar, from=Q2181577, from2=Q140898 Monotypic Oxalidales genera Oxalidales Oxalidales of Australia Carnivorous plants of Australia Rosids of Western Australia Vulnerable flora of Australia Endemic flora of Southwest Australia

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

which contains one species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

, ''Cephalotus follicularis'' the Albany pitcher plant, a small carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose nutrition and energy requirements are met by consumption of animal tissues (mainly mu ...

pitcher plant

Pitcher plants are carnivorous plants

known as pitfall traps—a prey-trapping mechanism featuring a deep cavity filled with digestive liquid. The traps of pitcher plant are considered to be "true" pitcher plants and are formed by specialized ...

. The pit-fall traps of the modified leaves have inspired the common name

In biology, a common name of a taxon or organism (also known as a vernacular name, English name, colloquial name, country name, popular name, or farmer's name) is a name that is based on the normal language of everyday life; and is often con ...

s for this plant, which also include Western Australian pitcher plant, Australian pitcher plant, or fly-catcher plant. It is an evergreen herb that is endemic to peaty swamps in the southwestern corner of Western Australia. As with the unrelated ''Nepenthes

''Nepenthes'' ( ) is a genus of carnivorous plants, also known as tropical pitcher plants, or monkey cups, in the monotypic family Nepenthaceae. The genus includes about 170 species, and numerous natural and many cultivated hybrids. They are m ...

'', it catches its victims with pitfall traps.

Description

''Cephalotus follicularis'' is a small, low growing, herbaceous species. Evergreen leaves appear from underground rhizomes, are simple with an entire leaf blade, and lie close to the ground. Theinsectivorous

A robber fly eating a hoverfly

An insectivore is a carnivorous animal or plant which eats insects. An alternative term is entomophage, which can also refer to the human practice of eating insects.

The first vertebrate insectivores we ...

leaves

A leaf (: leaves) is a principal appendage of the stem of a vascular plant, usually borne laterally above ground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, stem, ...

are small and have the appearance of moccasins

A moccasin is a shoe, made of deerskin or other soft leather, consisting of a sole (made with leather that has not been "worked") and sides made of one piece of leather, stitched together at the top, and sometimes with a vamp (additional pane ...

, forming the 'pitcher' of the common name. The pitchers develop a dark red colour in high light levels but stay green in shadier conditions. The foliage is a basal arrangement that is closely arranged with outward facing adapted leaf blades. These leaves give the main form of the species a height around 20 cm.

The 'pitcher' trap of the species is similar to other pitcher plant

Pitcher plants are carnivorous plants

known as pitfall traps—a prey-trapping mechanism featuring a deep cavity filled with digestive liquid. The traps of pitcher plant are considered to be "true" pitcher plants and are formed by specialized ...

s. The peristome

Peristome (from the Greek language, Greek ''peri'', meaning 'around' or 'about', and ''stoma'', 'mouth') is an anatomical feature that surrounds an opening to an organ or structure. Some plants, fungi, and shelled gastropods have peristomes.

In mo ...

at the entrance of the trap has a spiked arrangement that allows the prey to enter, but hinders its escape. The lid over the entrance, the operculum, prevents rainwater entering the pitcher and thus diluting the digestive enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s inside. Insects trapped in this digestive fluid are consumed by the plant. The operculum has translucent

In the field of optics, transparency (also called pellucidity or diaphaneity) is the physical property of allowing light to pass through the material without appreciable light scattering by particles, scattering of light. On a macroscopic scale ...

cells which confuse its insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

prey as they appear to be patches of sky.

The inflorescence

In botany, an inflorescence is a group or cluster of flowers arranged on a plant's Plant stem, stem that is composed of a main branch or a system of branches. An inflorescence is categorized on the basis of the arrangement of flowers on a mai ...

is groupings of small, hermaphroditic, six-parted, regular flowers

Flowers, also known as blooms and blossoms, are the reproductive structures of flowering plants ( angiosperms). Typically, they are structured in four circular levels, called whorls, around the end of a stalk. These whorls include: calyx, m ...

, which are creamy, or whitish.

In the cooler months of winter (down to about 5 degrees Celsius), they have a natural dormancy period of about 3–4 months, triggered by the temperature drop and reduced light levels.

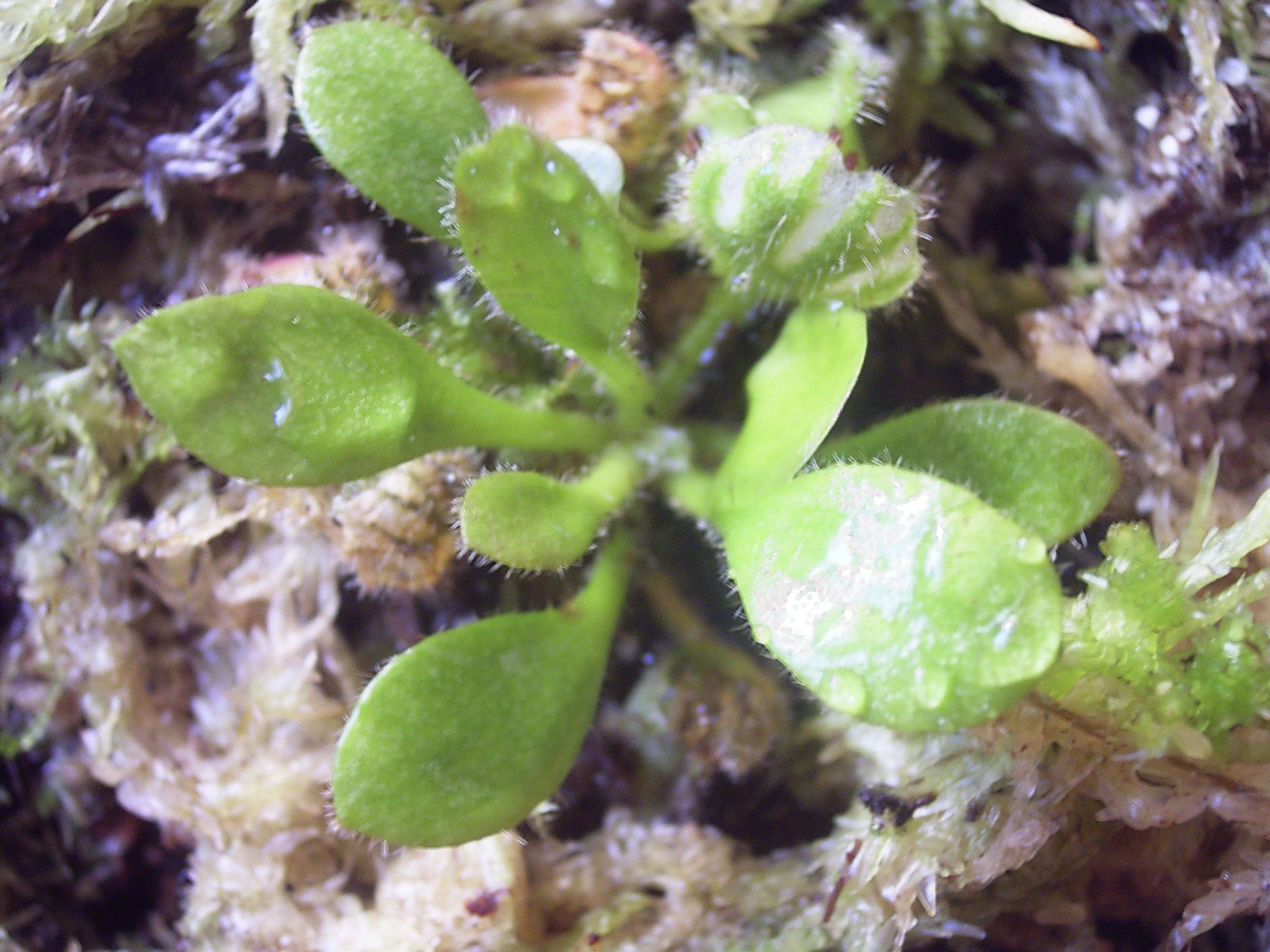

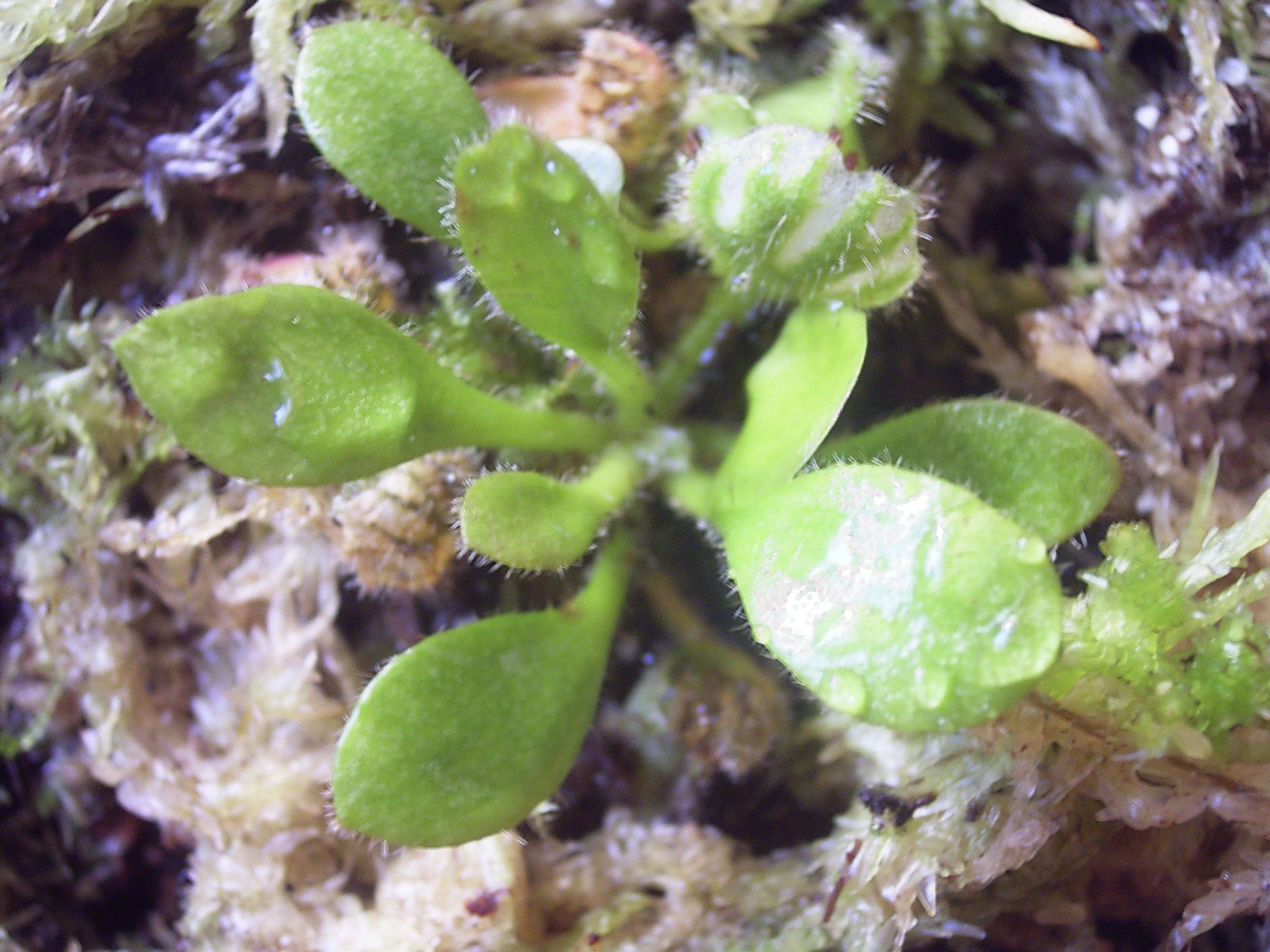

Habitus

The Australian pitcher plant is a wintergreen, long lasting,herbaceous plant

Herbaceous plants are vascular plants that have no persistent woody stems above ground. This broad category of plants includes many perennials, and nearly all annuals and biennials.

Definitions of "herb" and "herbaceous"

The fourth edition o ...

, which grows autochthonous rosettes and grows up to a height of 10 centimetres.

The rhizome

In botany and dendrology, a rhizome ( ) is a modified subterranean plant stem that sends out roots and Shoot (botany), shoots from its Node (botany), nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks or just rootstalks. Rhizomes develop from ...

is bulky, nodose with numerous scaly leaves and many offshoots. New rosettes grow at its stolon

In biology, a stolon ( from Latin ''wikt:stolo, stolō'', genitive ''stolōnis'' – "branch"), also known as a runner, is a horizontal connection between parts of an organism. It may be part of the organism, or of its skeleton. Typically, animal ...

so that it forms large tussocks with increasing age. The rhizome grows numerous fibrous root

In vascular plants, the roots are the plant organ, organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often bel ...

s. Younger plants also have a taproot

A taproot is a large, central, and dominant root from which other roots sprout laterally. Typically a taproot is somewhat straight and very thick, is tapering in shape, and grows directly downward. In some plants, such as the carrot, the taproot ...

, which dies when they grow older.John G. Conran: ''Cephalotaceae.'' In: Klaus Kubitzki

Klaus Kubitzki (3 May 1933 – 5 December 2022) was a German botanist. He was Emeritus professor in the University of Hamburg, at the Herbarium Hamburgense. He is known for his work on the systematics and biogeography of the angiosperms, particu ...

: (ed.): ''The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants.'' Volume 6: ''Flowering Plants – Dicotyledons – Celastrales, Oxalidales, Rosales, Cornales, Ericales.'' Springer, Berlin u. a. 2004, ISBN 3-540-06512-1, p. 65–69.

Leaves

The Australian pitcher plant grows two kinds ofleaves

A leaf (: leaves) is a principal appendage of the stem of a vascular plant, usually borne laterally above ground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, stem, ...

with the change of seasons: simple flat leaves as well as strongly modified trap leaves. Occasionally, there are intermediate forms of leaves with only partially developed traps, lacking the front part. All leaves grow alternating, they are petiolate, with single-celled fine hairs and beset with numerous sessile nectar

Nectar is a viscous, sugar-rich liquid produced by Plant, plants in glands called nectaries, either within the flowers with which it attracts pollination, pollinating animals, or by extrafloral nectaries, which provide a nutrient source to an ...

ies.

The form of the flat leaves range from spatulate to reverse ovoid. Additionally, they are pointed and up to 15 centimetres long. Approximately, half of the length of the leaves is allotted to the petiole

Petiole may refer to:

*Petiole (botany), the stalk of a leaf, attaching the blade to the stem

*Petiole (insect anatomy)

In entomology, petiole is the technical term for the narrow waist of some hymenopteran insects, especially ants, bees, and ...

. They are thick and coriaceaous, the edges are fringed while the leaf surface is smooth and glossy.

Trap leaves

The trap leaves are up to 5 centimeters long, egg-shaped and liquid-filled pitfall traps that are open at the top. They lie on the substrate at an angle of 45° or they are sunk into it in the case of mossy substrates. The petiole is cylindrical and fused to the back of the upper edge of the trap.Allen Lowrie

Allen Lowrie (10 October 1948 - 30 August 2021) was a Western Australian Botany, botanist. He was recognised for his expertise on the genera ''Drosera'' and ''Stylidium''.Council of Heads of Australasian HerbariaResources of Australian Herbaria: W ...

: ''Carnivorous Plants of Australia.'' Volume 3. University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands 1998, ISBN 1-875560-59-9, p. 128–131.

Four very hairy ridges on the outside of the traps make it easier for crawling animals to reach the trap opening. The outer skin is completely covered with glands that secrete a liquid, presumably nectar

Nectar is a viscous, sugar-rich liquid produced by Plant, plants in glands called nectaries, either within the flowers with which it attracts pollination, pollinating animals, or by extrafloral nectaries, which provide a nutrient source to an ...

.

A lid over the opening, an outgrowth of the petiole, spans the interior and protects it from rain, which could cause the pitcher fluid to overflow and wash out dead prey. It is curved, notched and ciliated at the edge, lacking a midrib. The inside is covered with short, downward-pointing hairs. The lid is alternately divided into white-translucent and dark red sections without chlorophyll

Chlorophyll is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words (, "pale green") and (, "leaf"). Chlorophyll allows plants to absorb energy ...

. The translucent sections appear window-like, through which trapped flying insects try to escape, only to fall back into the pitchers afterwards.

The inwardly overhanging, thickened edge of the trap is surrounded by large, inward-pointing, claw-like teeth in between nectar glands. Immediately adjacent to this is an area of short, downward-facing papillae that make it difficult to climb back up. The rest of the inner wall of the cauldron is smooth, so that the prey slips into the trap and cannot climb out of it.

The upper third, or the upper half of the trap leaf, is finely beset with glands. In the lower part of the trap there are two kidney-shaped, red-coloured spots that are densely covered with larger glands. These glands most likely produce the liquid in the can, as well as the digestive enzymes and also absorb the nutrients from the prey.

The upper third, or the upper half of the trap leaf, is finely beset with glands. In the lower part of the trap there are two kidney-shaped, red-coloured spots that are densely covered with larger glands. These glands most likely produce the liquid in the can, as well as the digestive enzymes and also absorb the nutrients from the prey.

Blossoms, fruit and seeds

Stipules are missing. The single flower stalk appears at the beginning of the Australian summer (flowering time: January–February) and is up to 60 centimetres long, with apanicle

In botany, a panicle is a much-branched inflorescence. (softcover ). Some authors distinguish it from a compound spike inflorescence, by requiring that the flowers (and fruit) be pedicellate (having a single stem per flower). The branches of a p ...

at its end. Each of the secondary axes bears up to four or five white, upright, six-cornered flower

Flowers, also known as blooms and blossoms, are the reproductive structures of flowering plants ( angiosperms). Typically, they are structured in four circular levels, called whorls, around the end of a stalk. These whorls include: calyx, m ...

s, which are up to 7 millimeters in diameter. There are missing petals

Petals are modified leaves that form an inner whorl surrounding the reproductive parts of flowers. They are often brightly coloured or unusually shaped to attract pollinators. All of the petals of a flower are collectively known as the ''coroll ...

and the six carpels

Gynoecium (; ; : gynoecia) is most commonly used as a collective term for the parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds. The gynoecium is the innermost whorl of a flower; it consists of (one or more) ...

are not fused. Flowers sag when they are fertilized. The spadiciform leathery, hairy follicle fruits and contain one or two brown, ovoid seeds with a membranous testa and rich, granular endosperm

The endosperm is a tissue produced inside the seeds of most of the flowering plants following double fertilization. It is triploid (meaning three chromosome sets per nucleus) in most species, which may be auxin-driven. It surrounds the Embryo#Pla ...

. The seeds are 0.8 millimetres long and 0.4 millimetres wide. The germination only occurs if the seed remains in the fruit.

Cytology and constituents

The chromosome number is 2n = 20. Tannin cells are present as well asmyricetin

Myricetin is a member of the flavonoid class of polyphenolic compounds, with antioxidant properties. Common dietary sources include vegetables (including tomatoes), fruits (including oranges), nuts, berries, tea, and red wine.

Myricetin is stru ...

, quercetin

Quercetin is a plant flavonol from the flavonoid group of polyphenols. It is found in many fruits, vegetables, leaves, seeds, and grains; capers, red onions, and kale are common foods containing appreciable amounts of it. It has a bitter flavor ...

, ellagic acid

Ellagic acid is a polyphenol found in numerous fruits and vegetables. It is the dilactone of hexahydroxydiphenic acid.

Name

The name comes from the French term ''acide ellagique'', from the word ''galle'' spelled backward because it can be o ...

, gallic acid

Gallic acid (also known as 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid) is a trihydroxybenzoic acid with the formula C6 H2( OH)3CO2H. It is classified as a phenolic acid. It is found in gallnuts, sumac, witch hazel, tea leaves, oak bark, and other plant ...

. However, iridoids

Iridoids are a type of monoterpenoids in the general form of cyclopentanopyran, found in a wide variety of plants and some animals. They are biosynthetically derived from 8-oxogeranial. Iridoids are typically found in plants as glycosides, mos ...

are absent.

Taxonomy

Thegenus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

as well as the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Cephalotaceae include only this one species, which means they are monotypic

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unisp ...

. The Cunoniaceae

Cunoniaceae is a family of 27 genera and about 335 species of woody plants in the order Oxalidales, mostly found in the tropical and wet temperate regions of the Southern Hemisphere. The greatest diversity of genera are in Australia and Tasmania ...

are their nearest relations. ''Brocchinia reducta

''Brocchinia reducta'' is a carnivorous plant in the bromeliad family. It is native to southern Venezuela, Brazil, Colombia, and Guyana, and is found in areas with nutrient-poor, high moisture soil. ''B. reducta'' is able to grow in sparse cond ...

'' and the Australian pitcher plant are the only carnivorous plants that are not part of the orders of Lamiales

The Lamiales (also known as the mint order) are an order of flowering plants in the asterids clade of the Eudicots. Under the APG IV system of flowering plant classification the order consists of 24 families, and includes about 23,810 species ...

, Caryophyllales

Caryophyllales ( ) is a diverse and heterogeneous order of flowering plants with well-known members including cacti, carnations, beets, quinoa, spinach, amaranths, pigfaces and ice plants, oraches and saltbushes, goosefoots, sundews, Venu ...

or Ericales

The Ericales are a large and diverse order of flowering plants in the asterid group of the eudicots. Well-known and economically important members of this order include tea and ornamental camellias, persimmon, ebony, blueberry, cranberry, l ...

and therefore not even indirectly related to other carnivorous plant

Carnivorous plants are plants that derive some or most of their nutrients from trapping and consuming animals or protozoans, typically insects and other arthropods, and occasionally small mammals and birds. They have adapted to grow in waterlo ...

s.

Taxonomic history

Botanical specimens were first collected during the visit of toKing George Sound

King George Sound (Mineng ) is a sound (geography), sound on the south coast of Western Australia. Named King George the Third's Sound in 1791, it was referred to as King George's Sound from 1805. The name "King George Sound" gradually came in ...

in December 1801 and January 1802. On 2 January 1802 the expedition's botanist, Robert Brown Robert Brown may refer to: Robert Brown (born 1965), British Director, Animator and author

Entertainers and artists

* Washboard Sam or Robert Brown (1910–1966), American musician and singer

* Robert W. Brown (1917–2009), American printmaker ...

, wrote in his diary:

This represents the earliest documentary reference to this species; and although not entirely unambiguous as to the first collection, it is usually taken as evidence that the plant was discovered by Ferdinand Bauer

Ferdinand Lucas Bauer (20 January 1760 – 17 March 1826) was an Austrian botanical illustrator who travelled on Matthew Flinders' expedition to Australia.

Biography Early life and career

Bauer was born in Feldsberg in 1760, the youngest son ...

and William Westall on 1 January 1802. Whether or not there was an earlier collection is largely immaterial, however, as all collections were incorporated into Brown's collection without attribution, so Brown is treated as the collector in botanical contexts.

Brown initially gave this species the manuscript name "'Cantharifera paludosa' KG III Sound", but this name was not published, and it would not be Brown who published the first description.

The following year, further specimens were collected by Jean Baptiste Leschenault de la Tour

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* Jea ...

, botanist to Nicolas Baudin

Nicolas Thomas Baudin (; 17 February 175416 September 1803) was a French explorer, cartographer, naturalist and hydrographer, most notable for his explorations in Australia and the southern Pacific. He carried a few corms of Gros Michel banana ...

's expedition. In 1806, Jacques Labillardière

Jacques-Julien Houtou de Labillardière (28 October 1755 – 8 January 1834) was a French biologist noted for his descriptions of the flora of Australia. Labillardière was a member of a voyage in search of the Jean-François de Galaup, comte ...

used these specimens as the basis of his publication of the species in '' Novae Hollandiae plantarum specimen''. Labillardière did not attribute Leschenault as the collector, and it was long thought that Labillardière had collected the plant himself during his visit to the area in the 1790s; in particular, Brown wrongly acknowledged Labillardière as the discoverer of this plant.

Leschenault's specimen was a fruiting plant, but the fruit was in poor condition, and as a result Labillardière erroneously placed it in the family Rosaceae

Rosaceae (), the rose family, is a family of flowering plants that includes 4,828 known species in 91 genera.

The name is derived from the type genus '' Rosa''. The family includes herbs, shrubs, and trees. Most species are deciduous, but som ...

. This error was not corrected until better fruiting specimens were collected by William Baxter in the 1820s. These were examined by Brown, who concluded that the plant merited its own family, and accordingly erected Cephalotaceae. It has remained in this monogeneric family ever since.

Current placement

The Australian pitcher plant is an advanced rosid, and thus closer related toapple

An apple is a round, edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus'' spp.). Fruit trees of the orchard or domestic apple (''Malus domestica''), the most widely grown in the genus, are agriculture, cultivated worldwide. The tree originated ...

s and oak

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisp ...

s than to other pitcher plant

Pitcher plants are carnivorous plants

known as pitfall traps—a prey-trapping mechanism featuring a deep cavity filled with digestive liquid. The traps of pitcher plant are considered to be "true" pitcher plants and are formed by specialized ...

s like Nepenthaceae ( basal core eudicots

The eudicots or eudicotyledons are flowering plants that have two seed leaves (cotyledons) upon germination. The term derives from ''dicotyledon'' (etymologically, ''eu'' = true; ''di'' = two; ''cotyledon'' = seed leaf). Historically, authors h ...

) and Sarraceniaceae

Sarraceniaceae are a family of pitcher plants, belonging to order Ericales (reassigned from Nepenthales).

The family comprises three extant genera: ''Sarracenia'' (North American pitcher plants), '' Darlingtonia'' (the cobra lily or California ...

(basal asterid

Asterids are a large clade (monophyletic group) of flowering plants, composed of 17 orders and more than 80,000 species, about a third of the total flowering plant species. The asterids are divided into the unranked clades lamiids (8 orders) and ...

s). The placement of its monotypic

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unisp ...

family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Cephalotaceae in the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

Saxifragales

Saxifragales is an order (biology), order of flowering plants in the Superrosids, superrosid clade of the eudicots. It contains 15 Families (biology), families and around 100 genera, with nearly 2,500 species. Well-known and economically import ...

has been abandoned. It is now placed within the order of Oxalidales where it is most closely related to Brunelliaceae

''Brunellia'' is a genus of flowering plants. They are trees distributed in the mountainous regions of southern Mexico, Central America, West Indies, and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and ...

, Cunoniaceae

Cunoniaceae is a family of 27 genera and about 335 species of woody plants in the order Oxalidales, mostly found in the tropical and wet temperate regions of the Southern Hemisphere. The greatest diversity of genera are in Australia and Tasmania ...

, and Elaeocarpaceae

Elaeocarpaceae is a family of flowering plants. The family contains approximately 615 species of trees and shrubs in 12 genera."Elaeocarpaceae" In: Klaus Kubitzki (ed.). ''The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants'' vol. VI. Springer-Verlag: Ber ...

. The monotypic arrangement of the family and genus is indicative of a high degree of endemism

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

, one of four such species of the region.

Ecology

The plant occurs in southern coastal districts of the Southwest botanical province in Australia; it has been recorded in the

The plant occurs in southern coastal districts of the Southwest botanical province in Australia; it has been recorded in the Warren

Warren most commonly refers to:

* Warren (burrow), a network dug by rabbits

* Warren (name), a given name and a surname, including lists of persons so named

Warren may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Warren (biogeographic region)

* War ...

, southern Jarrah Forest

Jarrah Forest, also known as the Southwest Australia woodlands, is an interim Australian bioregion and ecoregion located in the south west of Western Australia.

, and Esperance Plains

Esperance Plains, also known as Eyre Botanical District, is a biogeography, biogeographic region in southern Western Australia on the South_coast_of_Western_Australia , south coast between the Avon Wheatbelt and Hampton bioregions, and bordere ...

regions. Its habitat is on moist peaty sands found in swamps or along creeks and streams, but it is tolerant of less damp situations. Its population in the wild has been reduced by habitat destruction

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss or habitat reduction) occurs when a natural habitat is no longer able to support its native species. The organisms once living there have either moved elsewhere, or are dead, leading to a decrease ...

and overcollecting; it is therefore classified as vulnerable species

A vulnerable species is a species which has been Conservation status, categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as being threatened species, threatened with extinction unless the circumstances that are threatened species, ...

(VU A2ac; C2a(i)) by the IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the status ...

. However, this classification is not in unison with Australia's national EPBC Act List of Threatened Species or Western Australia's Wildlife Conservation Act 1950

The ''Wildlife Conservation Act 1950'' is an act of the Western Australian Parliament that provides the statute relating to conservation and legal protection of flora and fauna. Text was copied from this source, which is available under Attrib ...

, which both list the species as Not Threatened.

The larvae of '' Badisis ambulans'', an ant-like wingless micropezid fly, develop inside the pitchers. They have never been found anywhere else.

The plants survive occasional bush fires in the undergrowth by sprouting again from the rhizome. However, the seeds are not pyrophytes.

Carnivore

After the pitcher is formed, the lid lifts from theperistome

Peristome (from the Greek language, Greek ''peri'', meaning 'around' or 'about', and ''stoma'', 'mouth') is an anatomical feature that surrounds an opening to an organ or structure. Some plants, fungi, and shelled gastropods have peristomes.

In mo ...

and the pitcher is ready to catch. Digestive fluid is already in the pitcher. The prey is attracted by nectar secretions on the bottom of the pitcher lid and between the grooves of the pitcher rim. This causes the prey to fall in and drown. The liquid contains enzymes that break down the nutrients, including esterase

In biochemistry, an esterase is a class of enzyme that splits esters into an acid and an alcohol in a chemical reaction with water called hydrolysis (and as such, it is a type of hydrolase).

A wide range of different esterases exist that differ ...

s, phosphatase

In biochemistry, a phosphatase is an enzyme that uses water to cleave a phosphoric acid Ester, monoester into a phosphate ion and an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol. Because a phosphatase enzyme catalysis, catalyzes the hydrolysis of its Substrate ...

s and protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

s. In the majority of cases, ants are caught.

Traps as biotopes

As with all other carnivorous plant species with sliding traps, the trap fluid is also a biotope for other organisms. A study published in 1985 counted 166 different species, including 82%protozoa

Protozoa (: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically ...

, 4% oligochaeta

Oligochaeta () is a subclass of soft-bodied animals in the phylum Annelida, which is made up of many types of aquatic and terrestrial worms, including all of the various earthworms. Specifically, oligochaetes comprise the terrestrial megadril ...

and nematodes

The nematodes ( or ; ; ), roundworms or eelworms constitute the phylum Nematoda. Species in the phylum inhabit a broad range of environments. Most species are free-living, feeding on microorganisms, but many are parasitic. Parasitic worms (he ...

, 4% arthropods

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

(copepods

Copepods (; meaning 'oar-feet') are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (living in the water column), some are benthic (living on the sediments), several species have ...

, diptera

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advance ...

and mites

Mites are small arachnids (eight-legged arthropods) of two large orders, the Acariformes and the Parasitiformes, which were historically grouped together in the subclass Acari. However, most recent genetic analyses do not recover the two as eac ...

), 2% rotifers

The rotifers (, from Latin 'wheel' and 'bearing'), sometimes called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum (Rotifera ) of microscopic and near-microscopic pseudocoelomate animals.

They were first described by Rev. John Harris ...

, 1% tardigrades

Tardigrades (), known colloquially as water bears or moss piglets, are a phylum of eight-legged Segmentation (biology), segmented micro-animals. They were first described by the German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze in 1773, who calle ...

and 7% others (bacteria, fungi, algae). Bacteria and fungi in particular also secrete digestive enzymes and thus support the plant's digestive process. It is particularly noticeable that the traps are the "nursery" of two species of diptera. In addition to the larvae of a '' Dasyhelea'' species, the larvae of the micropezidae

The Micropezidae are a moderate-sized family of acalyptrate muscoid flies in the insect order Diptera, comprising about 500 species in about 50 genera and five subfamilies worldwide, (except New Zealand and Macquarie Island).McAlpine, D.K. (199 ...

'' Badisis ambulans'' also live in the cans.

Distribution and Endangerment

The plant is

The plant is endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

to the southwest of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, in the coastal area northeast of Albany in a zone of around between Augusta and Cape Riche

Cape Riche is a cape in the Great Southern region of Western Australia. By road, it is south-east of Perth and north-east of Albany. It is part of the locality of Wellstead and is south of the townsite.

Facilities in the area include a bo ...

. It is mainly found in cushions of Sphagnum on consistently moist but well-drained, acidic peat soils over granite, in seeping areas, along riverbanks or under so-called tussocks, grasses that grow in clumps (z. B. from Restionaceae

The Restionaceae, also called restiads and restios, are a family of flowering plants native to the Southern Hemisphere; they vary from a few centimeters to 3 meters in height. Following the APG IV (2016): the family now includes the former famil ...

).

The Australian pitcher plant is categorised as ''Vulnerable'' by the IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the status ...

due to its restricted distribution. However, there is no acute threat. Because parts of its distribution area are protected and the plants are common within this, they have been removed from CITES

CITES (shorter acronym for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of inte ...

-Appendix II.

Uses

The Australian pitcher plant is popular with enthusiasts of carnivorous plants and cultivated worldwide – however, its cultivation is considered challenging.Cultivation

perlite

Perlite is an amorphous volcanic glass that has a relatively high water content, typically formed by the Hydrate, hydration of obsidian. It occurs naturally and has the unusual property of greatly expanding when heated sufficiently. It is an indu ...

, and sand

Sand is a granular material composed of finely divided mineral particles. Sand has various compositions but is usually defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer to a textural ...

, a reasonable humidity

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation (meteorology), precipitation, dew, or fog t ...

(60–80%) is also preferred. It is successfully propagated from root and leaf cuttings, usually non-carnivorous leaves although pitchers can also be used. A dormancy period is probably crucial to long-term health of the plant.

The plants become colourful and grow vigorously when kept in direct sunlight, while plants cultivated in bright shade remain green.

Living plants were delivered to Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens is a botanical garden, botanic garden in southwest London that houses the "largest and most diverse botany, botanical and mycology, mycological collections in the world". Founded in 1759, from the exotic garden at Kew Park, its li ...

by Phillip Parker King

Phillip Parker King (13 December 1791 – 26 February 1856) was an early explorer of the Australian and Patagonian coasts.

Early life and education

King was born on Norfolk Island, to Philip Gidley King and Anna Josepha King ''née'' Coo ...

in 1823. A specimen flowered in 1827 and provided one source for an illustration in ''Curtis's Botanical Magazine

''The Botanical Magazine; or Flower-Garden Displayed'', is an illustrated publication which began in 1787. The longest running botanical magazine, it is widely referred to by the subsequent name ''Curtis's Botanical Magazine''.

Each of the issue ...

''.

This plant is a recipient of the Royal Horticultural Society

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS), founded in 1804 as the Horticultural Society of London, is the UK's leading gardening charity.

The RHS promotes horticulture through its five gardens at Wisley (Surrey), Hyde Hall (Essex), Harlow Carr ...

's Award of Garden Merit

The Award of Garden Merit (AGM) is a long-established award for plants by the British Royal Horticultural Society (RHS). It is based on assessment of the plants' performance under UK growing conditions.

It includes the full range of cultivated p ...

.

There are several dozen ''Cephalotus'' clones that exist in cultivation; nine have been officially registered as

There are several dozen ''Cephalotus'' clones that exist in cultivation; nine have been officially registered as cultivar

A cultivar is a kind of Horticulture, cultivated plant that people have selected for desired phenotypic trait, traits and which retains those traits when Plant propagation, propagated. Methods used to propagate cultivars include division, root a ...

s. One of the most well-known is 'Eden Black', a cultivar with unusually dark-coloured pitchers.

Genomics

Thegenome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

of the pitcher plant ''Cephalotus follicularis'' has been sequenced. Its carnivorous and non-carnivorous leaves have been compared to identify genetic differences associated with key features relating to the attraction of prey and their capture, digestion and nutrient absorption. Results support the independent convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

of ''Cephalotus'' and other carnivorous plant lineages. but also suggest that different lineages co-opted similar genes in developing digestive functions. This implies that the ways in which carnivory can be developed are limited.

Botanical History

The Australian pitcher plant was possibly already discovered in 1791 on the expedition by the botanistArchibald Menzies

Archibald Menzies ( ; 15 March 1754 – 15 February 1842) was a Scottish surgeon, botanist and naturalist. He spent many years at sea, serving with the Royal Navy, private merchants, and the Vancouver Expedition.

During his naval expeditions, h ...

. The plant was first described in 1806 by Jacques Julien Houtton de La Billardière. In 1800 Robert Brown Robert Brown may refer to: Robert Brown (born 1965), British Director, Animator and author

Entertainers and artists

* Washboard Sam or Robert Brown (1910–1966), American musician and singer

* Robert W. Brown (1917–2009), American printmaker ...

had already observed the species while catching insects. Since 1823 specimens of the plant have been cultivated in the botanic garden Kew Gardens

Kew Gardens is a botanical garden, botanic garden in southwest London that houses the "largest and most diverse botany, botanical and mycology, mycological collections in the world". Founded in 1759, from the exotic garden at Kew Park, its li ...

. In 1829 Dumortier categorised the species in its own monotypic family, which is still valid today.Wilhelm Barthlott

Wilhelm Barthlott (born 22 June 1946 in Forst, Germany) is a German botanist and biomimetic materials scientist. His official botanical author citation is Barthlott.

Barthlott's areas of specialization are biodiversity (global distribution, a ...

, Stefan Porembski, Rüdiger Seine, Inge Theisen: ''Karnivoren. Biologie und Kultur fleischfressender Pflanzen.'' Ulmer, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8001-4144-2, p. 87–90.

Due to the form of the anther

The stamen (: stamina or stamens) is a part consisting of the male reproductive organs of a flower. Collectively, the stamens form the androecium., p. 10

Morphology and terminology

A stamen typically consists of a stalk called the filament ...

La Billardière uses the Greek term ''kefalotus'' ("to have a head") for the genus. ''Follicularis'' derives from ''follicus'', meaning "small sack", and refers to the form of the jars. The Australian pitcher plant is also called ''Albany Pitcher Plant'' or ''Western Australian Pitcher Plant''.

Images

See also

*Carnivorous plants of Australia

Australia has one of the world's richest carnivorous plant floras, with around 187 recognised species from 6 genus, genera.Bourke, G. & R. Nunn 2012. ''Australian Carnivorous Plants''. Redfern Natural History Productions, Poole.

Species

The fol ...

References

External links

* *Inner World of ''Cephalotus follicularis'' from the John Innes Centre

* {{Taxonbar, from=Q2181577, from2=Q140898 Monotypic Oxalidales genera Oxalidales Oxalidales of Australia Carnivorous plants of Australia Rosids of Western Australia Vulnerable flora of Australia Endemic flora of Southwest Australia