The American frontier, also known as the Old West, and popularly known as the Wild West, encompasses the

geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

,

history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

,

folklore

Folklore is the body of expressive culture shared by a particular group of people, culture or subculture. This includes oral traditions such as Narrative, tales, myths, legends, proverbs, Poetry, poems, jokes, and other oral traditions. This also ...

, and

culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

associated with the forward wave of

American expansion in mainland

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

that began with

European colonial settlements in the early 17th century and ended with the admission of the last few contiguous western territories as states in 1912. This era of massive migration and settlement was particularly encouraged by President

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

following the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

, giving rise to the

expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who ...

attitude known as "

manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

" and historians' "

Frontier Thesis". The legends, historical events and folklore of the American frontier, known as the

frontier myth, have embedded themselves into United States culture so much so that the Old West, and the Western genre of media specifically, has become one of the defining features of American national identity.

Periodization

Historians have debated at length as to when the frontier era began, when it ended, and which were its key sub-periods.

[Brian W. Dippie, "American Wests: historiographical perspectives." ''American Studies International'' 27.2 (1989): 3–25.] For example, the Old West subperiod is sometimes used by historians regarding the time from the end of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

in 1865 to when the Superintendent of the Census,

William Rush Merriam, stated the

U.S. Census Bureau would stop recording western frontier settlement as part of its census categories after the

1890 U.S. census.

His successors however continued the practice until the

1920 census.

Others, including the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

and

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, often cite differing points reaching into the early 1900s; typically within the first two decades before American entry into

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

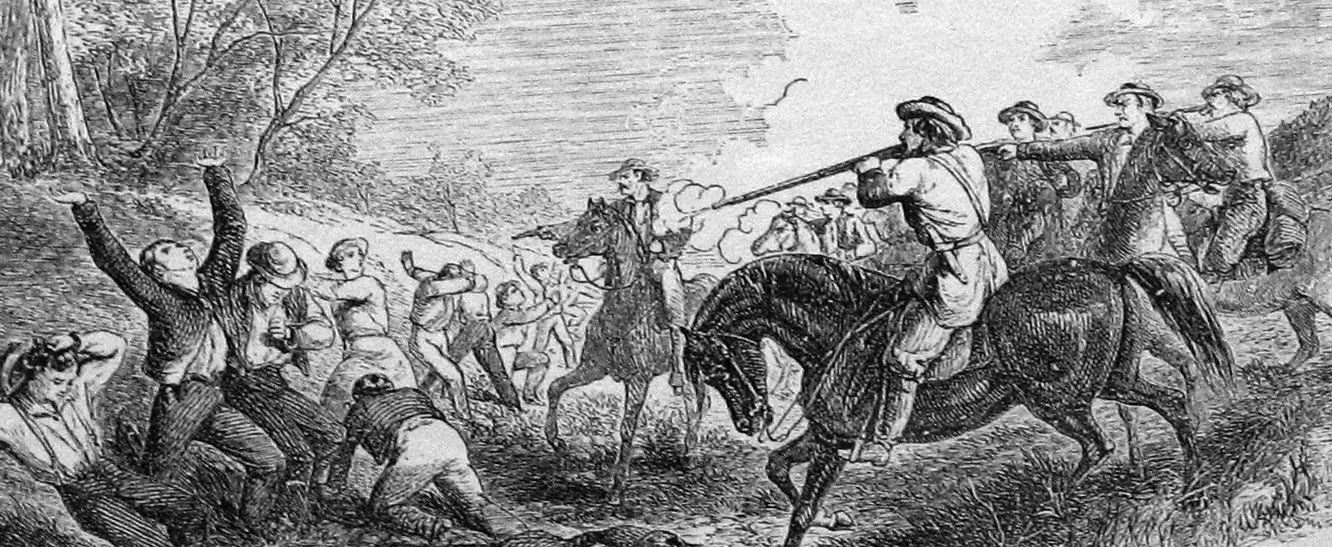

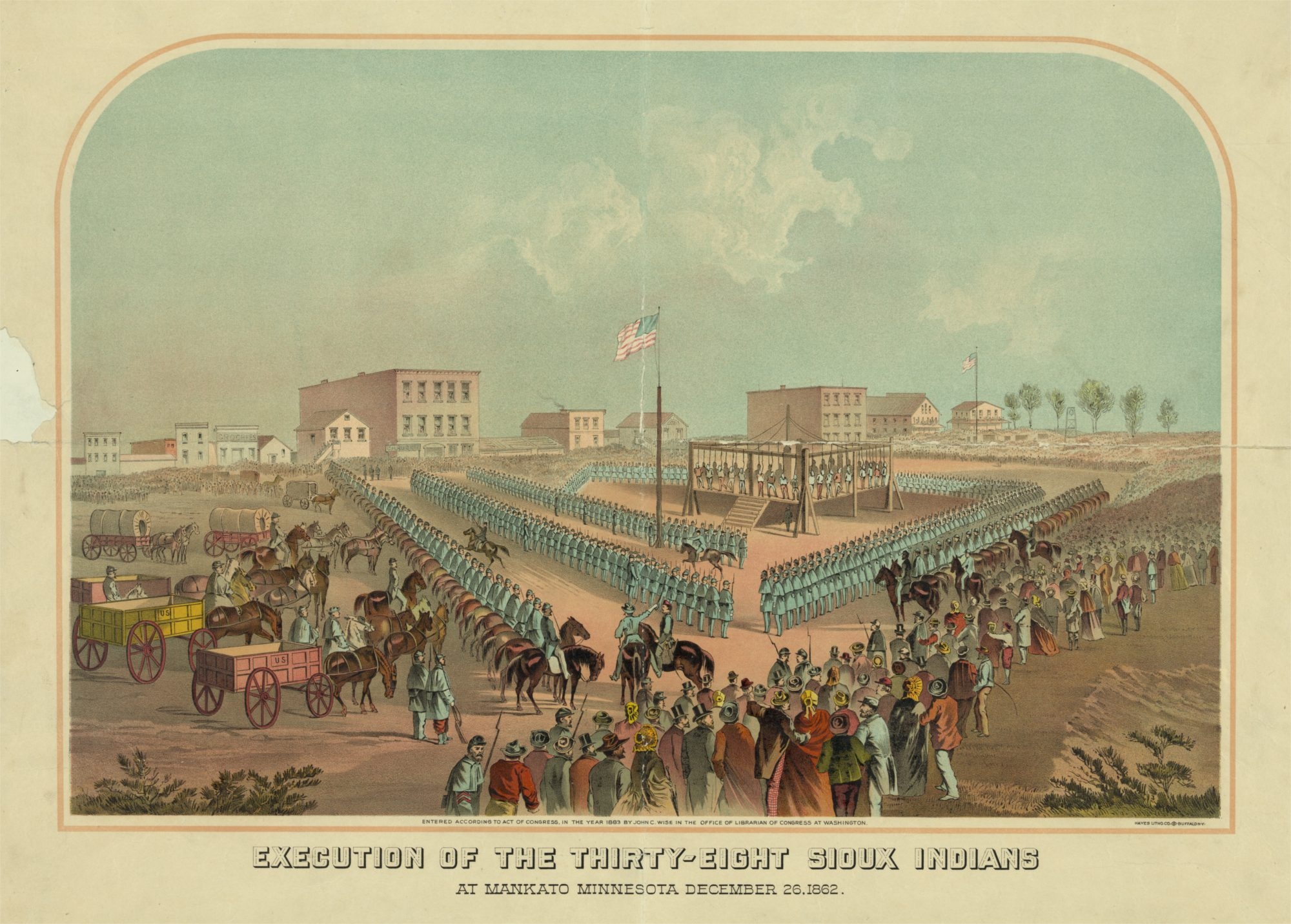

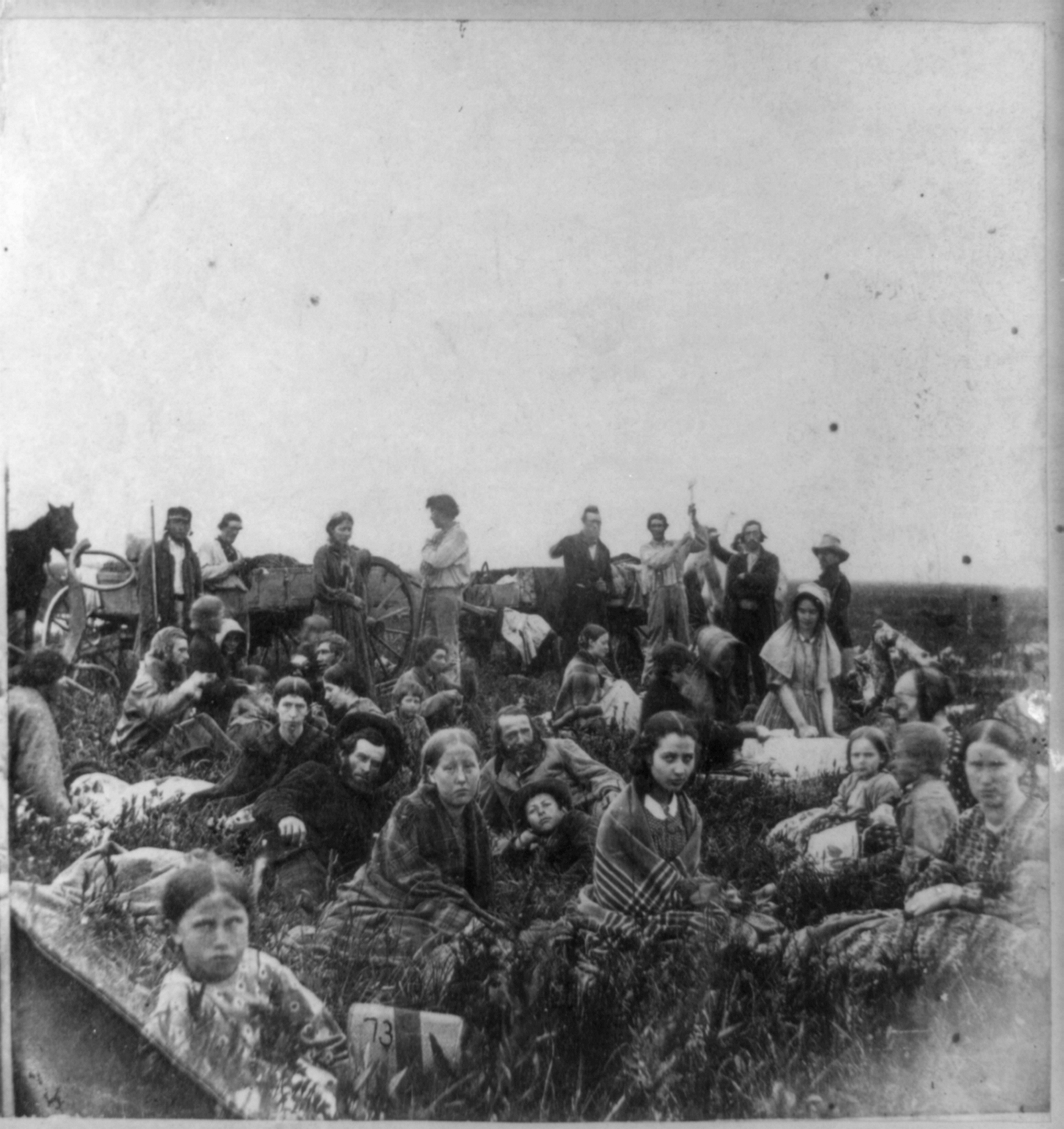

. A period known as "The Western Civil War of Incorporation" lasted from the 1850s to 1919. This period includes historical events synonymous with the archetypical Old West or "Wild West" such as

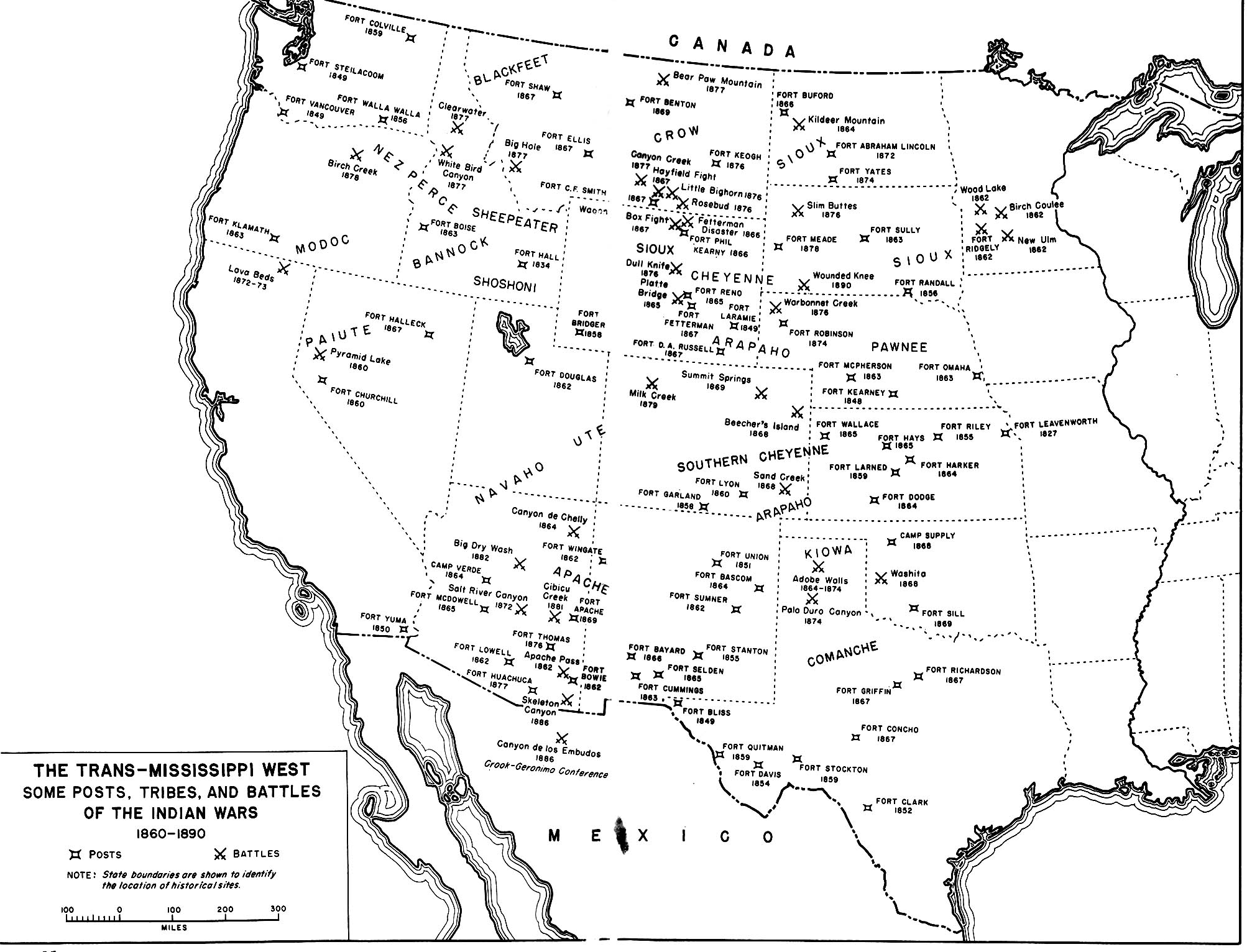

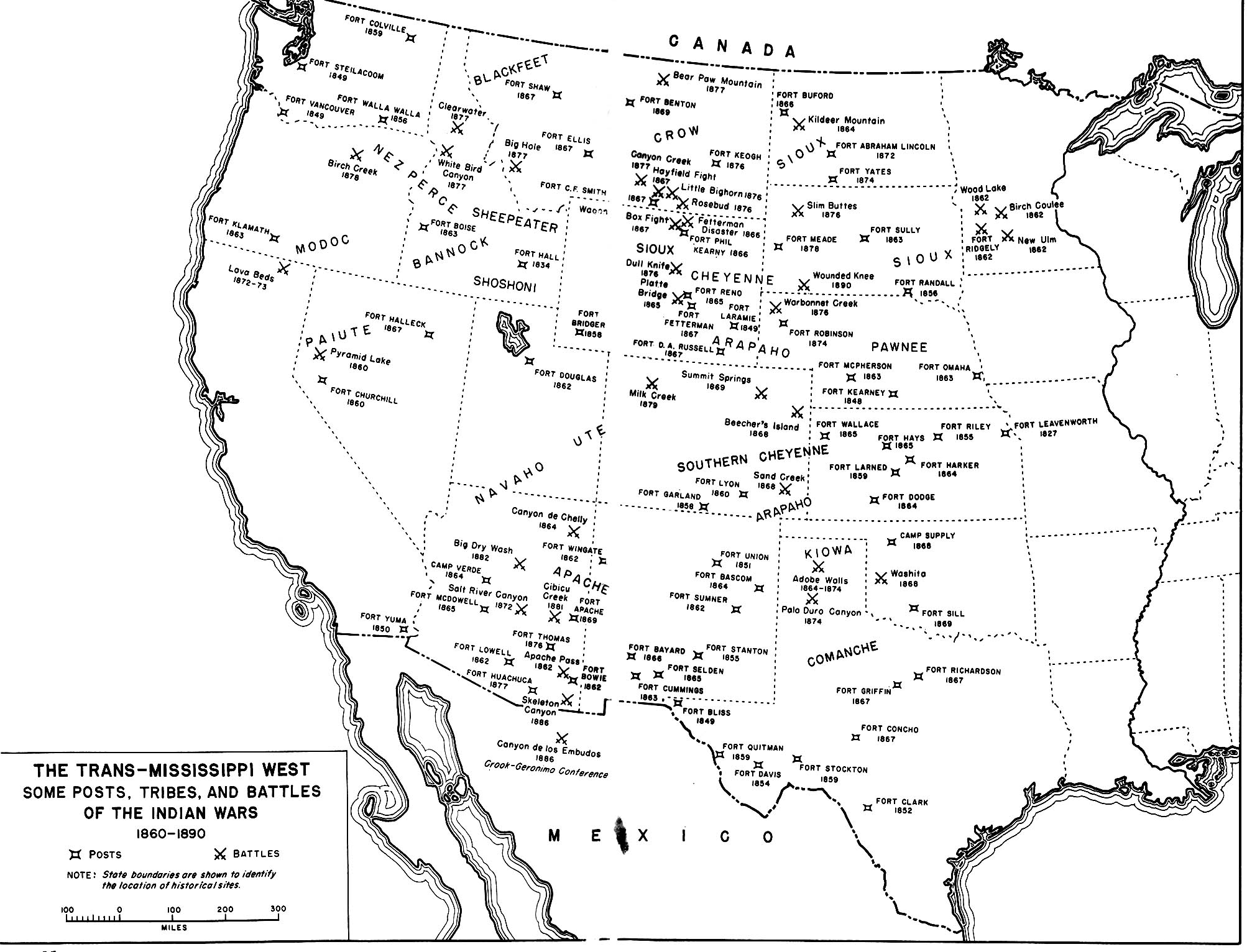

violent conflict arising from encroaching settlement into frontier land, the removal and assimilation of natives, consolidation of property to large corporations and government, vigilantism, and the attempted enforcement of laws upon outlaws.

In 1890, the Superintendent of the Census,

William Rush Merriam stated: "Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement, but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line. In the discussion of its extent, its westward movement, etc., it can not, therefore, any longer have a place in the census reports." Despite this, the later

1900 U.S. census continued to show the westward frontier line, and his successors continued the practice.

By the

1910 U.S. census however, the frontier had shrunk into divided areas without a singular westward line of settlement. An influx of agricultural homesteaders in the first two decades of the 20th century, taking up more acreage than homestead grants in the entirety of the 19th century, is cited to have significantly reduced open land.

A ''

frontier

A frontier is a political and geographical term referring to areas near or beyond a boundary.

Australia

The term "frontier" was frequently used in colonial Australia in the meaning of country that borders the unknown or uncivilised, th ...

'' is a zone of contact at the edge of a line of settlement. Theorist

Frederick Jackson Turner went deeper, arguing that the frontier was the scene of a defining process of American civilization: "The frontier," he asserted, "promoted the formation of a composite nationality for the American people." He theorized it was a process of development: "This perennial rebirth, this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward...furnish

sthe forces dominating American character." Turner's ideas since 1893 have inspired generations of historians (and critics) to explore multiple individual American frontiers, but the popular folk frontier concentrates on the conquest and settlement of

Native American lands west of the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

, in what is now the

Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

,

Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, the

Great Plains

The Great Plains is a broad expanse of plain, flatland in North America. The region stretches east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, and grassland. They are the western part of the Interior Plains, which include th ...

, the

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

, the

Southwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A '' compass rose'' is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west— ...

, and the

West Coast.

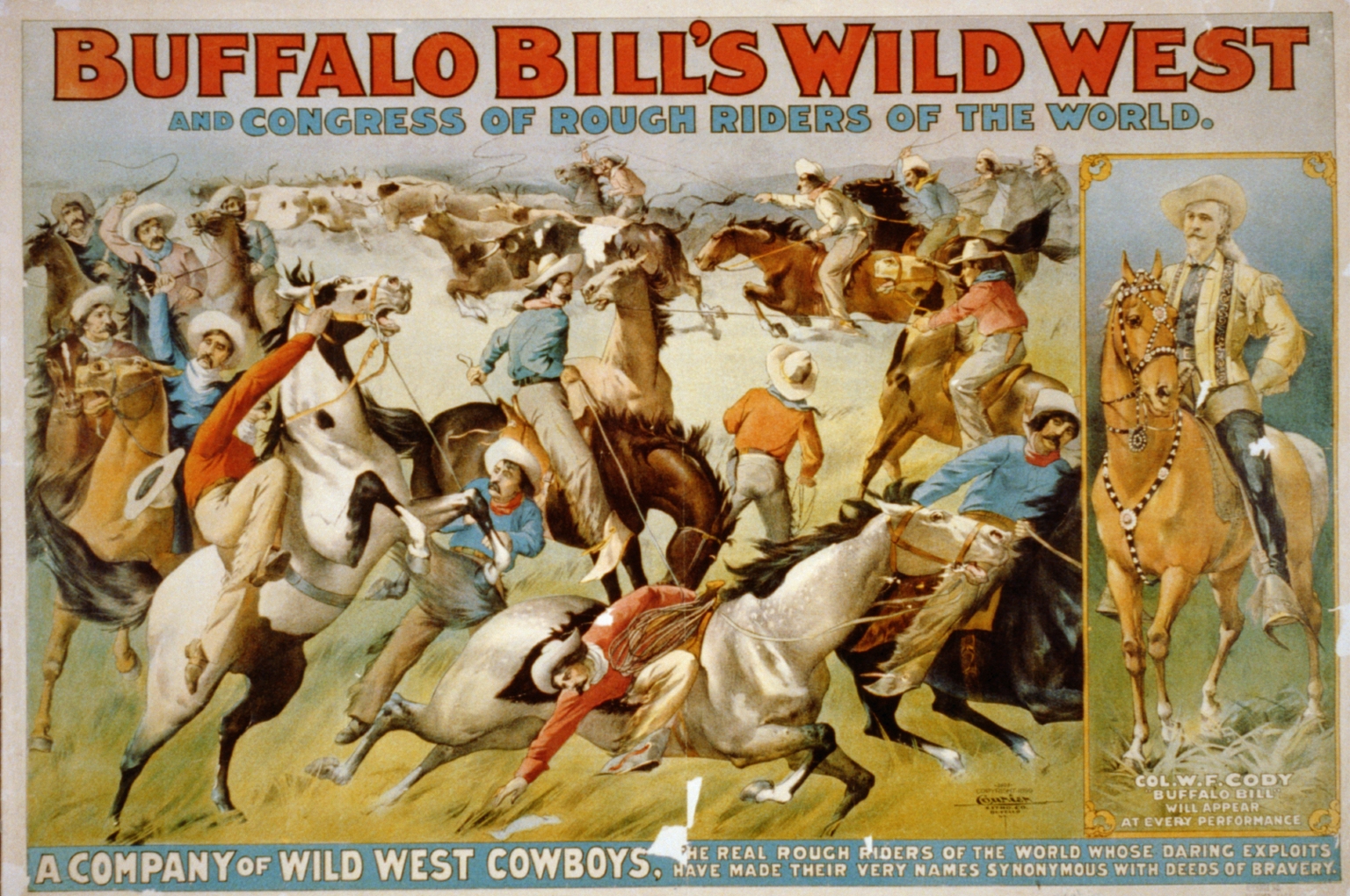

Enormous popular attention was focused on the

Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is List of regions of the United States, census regions United States Census Bureau.

As American settlement i ...

(especially the

Southwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A '' compass rose'' is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west— ...

) in the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century, from the 1850s to the 1910s. Such media typically exaggerated the romance, anarchy, and chaotic violence of the period for greater dramatic effect. This inspired the

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

genre of film, along with

television shows,

novels,

comic books

A comic book, comic-magazine, or simply comic is a publication that consists of comics art in the form of sequential juxtaposed panel (comics), panels that represent individual scenes. Panels are often accompanied by descriptive prose and wri ...

,

video games

A video game or computer game is an electronic game that involves interaction with a user interface or input device (such as a joystick, game controller, controller, computer keyboard, keyboard, or motion sensing device) to generate visual fe ...

, children's toys, and costumes.

As defined by Hine and Faragher, "frontier history tells the story of the creation and defense of communities, the use of the land, the development of crops and hotels, and the formation of states." They explain, "It is a tale of conquest, but also one of survival, persistence, and the merging of peoples and cultures that gave birth and continuing life to America." Turner himself repeatedly emphasized how the availability of "free land" to start new farms attracted pioneering Americans: "The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development."

Through treaties with foreign nations and

native tribes, political compromise, military conquest, the establishment of law and order, the building of farms, ranches, and towns, the marking of trails and digging of mines, combined with successive waves of immigrants moving into the region, the United States expanded from coast to coast, fulfilling the ideology of Manifest Destiny. In his "

Frontier Thesis" (1893), Turner theorized that the frontier was a process that transformed Europeans into a new people, the Americans, whose values focused on equality, democracy, and optimism, as well as

individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

, self-reliance, and even violence.

Terms ''West'' and ''frontier''

The

frontier

A frontier is a political and geographical term referring to areas near or beyond a boundary.

Australia

The term "frontier" was frequently used in colonial Australia in the meaning of country that borders the unknown or uncivilised, th ...

is the margin of undeveloped territory that would comprise the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

beyond the established frontier line. The

U.S. Census Bureau designated frontier territory as generally unoccupied land with a population density of fewer than 2 people per square mile (0.77 people per square kilometer). The frontier line was the outer boundary of European-American settlement into this land. Beginning with the first permanent European settlements on the

East Coast, it has moved steadily westward from the 1600s to the 1900s (decades) with occasional movements north into Maine and New Hampshire, south into Florida, and east from California into Nevada.

Pockets of settlements would also appear far past the established frontier line, particularly on the

West Coast and the deep interior, with settlements such as

Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

and

Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City, often shortened to Salt Lake or SLC, is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Utah. It is the county seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in the state. The city is the core of the Salt Lake Ci ...

respectively. The "

West

West is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some Romance langu ...

" was the recently settled area near that boundary. Thus, parts of the

Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

and

American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is census regions United States Census Bureau. It is between the Atlantic Ocean and the ...

, though no longer considered "western", have a frontier heritage along with the modern western states.

Richard W. Slatta, in his view of the frontier, writes that "historians sometimes define the American West as lands west of the ''98th

meridian'' or 98° west

longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

," and that other definitions of the region "include all lands west of the Mississippi or Missouri rivers."

Maps of United States territories

File:United States 1789-03-1789-08.png, 1789: The new nation

File:United States 1819-12-1820.png, 1819–1820: Post-War of 1812

File:United States 1845-12-1846-06.png, 1845–1846: Before Mexican–American War

File:United States 1859-1860.png, 1859–1860: Pre-Civil War Expansion

File:United States 1884-1889-11-02.png, 1884–1889: Post–Civil War expansion

File:United States 1912-08-1959-01.png, 1912: Contiguous US, all states

Key:

History

Colonial frontier

In the

colonial era, before 1776, the west was of high priority for settlers and politicians. The American frontier began when

Jamestown, Virginia

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent British colonization of the Americas, English settlement in the Americas. It was located on the northeast bank of the James River, about southwest of present-day Willia ...

, was settled by the English in 1607. In the earliest days of European settlement on the Atlantic coast, until about 1680, the frontier was essentially any part of the interior of the continent beyond the fringe of existing settlements along the Atlantic coast.

English,

French,

Spanish, and

Dutch patterns of expansion and settlement were quite different. Only a few thousand French migrated to Canada; these

habitants settled in villages along the

St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (, ) is a large international river in the middle latitudes of North America connecting the Great Lakes to the North Atlantic Ocean. Its waters flow in a northeasterly direction from Lake Ontario to the Gulf of St. Lawren ...

, building communities that remained stable for long stretches. Although French fur traders ranged widely through the Great Lakes and midwest region, they seldom settled down. French settlement was limited to a few very small villages such as

Kaskaskia, Illinois, as well as a larger settlement around

New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

. In what is now New York state the Dutch set up fur trading posts in the Hudson River valley, followed by large grants of land to rich landowning

patroon

In the United States, a patroon (; from Dutch '' patroon'' ) was a landholder with manorial rights to large tracts of land in the 17th-century Dutch colony of New Netherland on the east coast of North America. Through the Charter of Free ...

s who brought in tenant farmers who created compact, permanent villages. They created a dense rural settlement in upstate New York, but they did not push westward.

Areas in the north that were in the frontier stage by 1700 generally had poor transportation facilities, so the opportunity for commercial agriculture was low. These areas remained primarily in subsistence agriculture, and as a result, by the 1760s these societies were highly

egalitarian

Egalitarianism (; also equalitarianism) is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all h ...

, as explained by historian Jackson Turner Main:

In the South, frontier areas that lacked transportation, such as the

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

region, remained based on subsistence farming and resembled the egalitarianism of their northern counterparts, although they had a larger upper-class of slaveowners. North Carolina was representative. However, frontier areas of 1700 that had good river connections were increasingly transformed into plantation agriculture. Rich men came in, bought up the good land, and worked it with slaves. The area was no longer "frontier". It had a stratified society comprising a powerful upper-class white landowning gentry, a small middle-class, a fairly large group of landless or tenant white farmers, and a growing slave population at the bottom of the social pyramid. Unlike the North, where small towns and even cities were common, the South was overwhelmingly rural.

From British peasants to American farmers

The seaboard colonial settlements gave priority to land ownership for individual farmers, and as the population grew they pushed westward for fresh farmland. Unlike Britain, where a

small number of landlords owned most of the land, ownership in America was cheap, easy and widespread. Land ownership brought a degree of independence as well as a vote for local and provincial offices. The typical

New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

settlements were quite compact and small, under a square mile. Conflict with the Native Americans arose out of political issues, namely who would rule. Early frontier areas east of the Appalachian Mountains included the Connecticut River valley, and northern New England (which was a move to the north, not the west).

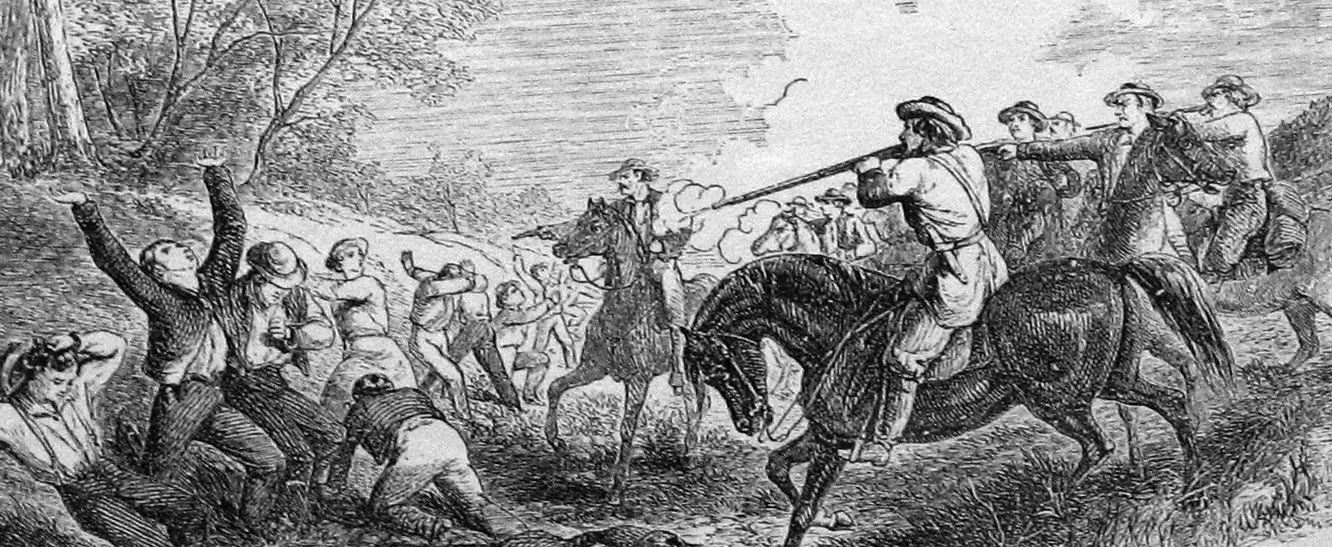

Wars with French and with natives

Settlers on the frontier often connected isolated incidents to indicate Indian conspiracies to attack them, but these lacked a French diplomatic dimension after 1763, or a Spanish connection after 1820.

Most of the frontiers experienced numerous conflicts. The

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

broke out between Britain and France, with the French making up for their small colonial population base by enlisting Native war parties as allies. The series of large wars spilling over from European wars ended in a complete victory for the British in the worldwide

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

. In the

peace treaty of 1763, France ceded practically everything, as the lands west of the Mississippi River, in addition to Florida and New Orleans, went to Spain. Otherwise, lands east of the Mississippi River and what is now Canada went to Britain.

Steady migration to frontier lands

Regardless of wars, Americans were moving across the Appalachians into western Pennsylvania, what is now West Virginia, and areas of the

Ohio Country, Kentucky, and Tennessee. In the southern settlements via the

Cumberland Gap, their most famous leader was

Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (, 1734September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyo ...

. Young

George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

promoted settlements in western Virginia and what is now West Virginia on lands awarded to him and his soldiers by the Royal government in payment for their wartime service in Virginia's militia. Settlements west of the Appalachian Mountains were curtailed briefly by the

Royal Proclamation of 1763, forbidding settlement in this area. The

Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768) re-opened most of the western lands for frontiersmen to settle.

New nation

The nation was at peace after 1783. The states gave Congress control of the western lands and an effective system for population expansion was developed. The

Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

of 1787 abolished slavery in the area north of the Ohio River and promised statehood when a territory reached a threshold population, as

Ohio did in 1803.

The first major movement west of the Appalachian mountains originated in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina as soon as the

Revolutionary War ended in 1781. Pioneers housed themselves in a rough lean-to or at most a one-room log cabin. The main food supply at first came from hunting deer, turkeys, and other abundant game.

In a few years, the pioneer added hogs, sheep, and cattle, and perhaps acquired a horse. Homespun clothing replaced the animal skins. The more restless pioneers grew dissatisfied with over civilized life and uprooted themselves again to move 50 or a hundred miles (80 or 160 km) further west.

Land policy

The land policy of the new nation was conservative, paying special attention to the needs of the settled East. The goals sought by both parties in the 1790–1820 era were to grow the economy, avoid draining away the skilled workers needed in the East, distribute the land wisely, sell it at prices that were reasonable to settlers yet high enough to pay off the national debt, clear legal titles, and create a diversified Western economy that would be closely interconnected with the settled areas with minimal risk of a breakaway movement. By the 1830s, however, the West was filling up with squatters who had no legal deed, although they may have paid money to previous settlers. The

Jacksonian Democrats favored the squatters by promising rapid access to cheap land. By contrast,

Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

was alarmed at the "lawless rabble" heading West who were undermining the utopian concept of a law-abiding, stable middle-class republican community. Rich southerners, meanwhile, looked for opportunities to buy high-quality land to set up slave plantations. The Free Soil movement of the 1840s called for low-cost land for free white farmers, a position enacted into law by the new Republican Party in 1862, offering free 160 acres (65 ha)

homesteads to all adults, male and female, black and white, native-born or immigrant.

After winning the

Revolutionary War (1783), American settlers in large numbers poured into the west. In 1788,

American pioneers to the Northwest Territory established

Marietta, Ohio

Marietta is a city in Washington County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is located in Appalachian Ohio, southeastern Ohio at the confluence of the Muskingum River, Muskingum and Ohio Rivers, northeast of Parkersburg, West Virginia ...

, as the first permanent American settlement in the

Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

.

In 1775,

Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (, 1734September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyo ...

blazed a trail for the

Transylvania Company from Virginia through the

Cumberland Gap into central Kentucky. It was later lengthened to reach the

Falls of the Ohio at

Louisville

Louisville is the most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeast, and the 27th-most-populous city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 24th-largest city; however, by populatio ...

. The Wilderness Road was steep and rough, and it could only be traversed on foot or horseback, but it was the best route for thousands of settlers moving into

Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

. In some areas they had to face Native attacks. In 1784 alone, Natives killed over 100 travelers on the Wilderness Road. Kentucky at this time had been depopulated—it was "empty of Indian villages." However raiding parties sometimes came through. One of those intercepted was

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

's grandfather, who was scalped in 1784 near Louisville.

Acquisition of native lands

The

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

marked the final confrontation involving major British and Native forces fighting to stop American expansion. The British war goal included the creation of an

Indian barrier state under British auspices in the Midwest which would halt American expansion westward. American frontier militiamen under General

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

defeated the Creeks and opened the Southwest, while militia under Governor

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

defeated the Native-British alliance at the

Battle of the Thames in Canada in 1813. The death in battle of the Native leader

Tecumseh dissolved the coalition of hostile Native tribes. Meanwhile, General

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

ended the Native military threat in the Southeast at the

Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814 in Alabama. In general, the frontiersmen battled the Natives with little help from the U.S. Army or the federal government.

To end the war, American diplomats negotiated the

Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

, signed towards the end of 1814, with Britain. They rejected the British plan to set up a Native state in U.S. territory south of the Great Lakes. They explained the American policy toward the acquisition of Native lands:

New territories and states

As settlers poured in, the frontier districts first became territories, with an elected legislature and a governor appointed by the president. Then when the population reached 100,000 the territory applied for statehood. Frontiersmen typically dropped the legalistic formalities and restrictive franchise favored by eastern upper classes and adopting more democracy and more egalitarianism.

In 1810, the western frontier had reached the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

.

St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Miss ...

, was the largest town on the frontier, the gateway for travel westward, and a principal trading center for Mississippi River traffic and inland commerce but remained under Spanish control until 1803.

Louisiana Purchase

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

thought of himself as a man of the frontier and was keenly interested in expanding and exploring the West. Jefferson's

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

of 1803 doubled the size of the nation at the cost of $15 million, or about $0.04 per acre ($ million in dollars, less than 42 cents per acre).

Federalists opposed the expansion, but

Jeffersonians hailed the opportunity to create millions of new farms to expand the domain of land-owning

yeomen; the ownership would strengthen the ideal republican society, based on agriculture (not commerce), governed lightly, and promoting self-reliance and virtue, as well as form the political base for

Jeffersonian Democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, wh ...

.

France was paid for its sovereignty over the territory in terms of international law. Between 1803 and the 1870s, the federal government purchased the land from the Native tribes then in possession of it. 20th-century accountants and courts have calculated the value of the payments made to the Natives, which included future payments of cash, food, horses, cattle, supplies, buildings, schooling, and medical care. In cash terms, the total paid to the tribes in the area of the Louisiana Purchase amounted to about $2.6 billion, or nearly $9 billion in 2016 dollars. Additional sums were paid to the Natives living east of the Mississippi for their lands, as well as payments to Natives living in parts of the west outside the Louisiana Purchase.

Even before the purchase, Jefferson was planning expeditions to explore and map the lands. He charged

Lewis and Clark

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* " Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohe ...

to "explore the Missouri River, and such principal stream of it, as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean; whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado, or any other river may offer the most direct and practicable communication across the continent for commerce". Jefferson also instructed the expedition to study the region's native tribes (including their morals, language, and culture), weather, soil, rivers, commercial trading, and animal and plant life.

Entrepreneurs, most notably

John Jacob Astor quickly seized the opportunity and expanded fur trading operations into the

Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

. Astor's "

Fort Astoria

Fort Astoria (also named Fort George) was the primary Fur trade, fur trading post of John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company (PFC). A maritime contingent of PFC staff was sent on board the ''Tonquin (1807 ship), Tonquin'', while another party tra ...

" (later Fort George), at the mouth of the Columbia River, became the first permanent white settlement in that area, although it was not profitable for Astor. He set up the American Fur Company in an attempt to break the hold that the

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

monopoly had over the region. By 1820, Astor had taken over independent traders to create a profitable monopoly; he left the business as a multi-millionaire in 1834.

Fur trade

As the frontier moved west,

trappers and

hunters moved ahead of settlers, searching out new supplies of

beaver

Beavers (genus ''Castor'') are large, semiaquatic rodents of the Northern Hemisphere. There are two existing species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers are the second-large ...

and other skins for shipment to Europe. The hunters were the first Europeans in much of the Old West and they formed the first working relationships with the Native Americans in the West. They added extensive knowledge of the Northwest terrain, including the important

South Pass through the central Rocky Mountains. Discovered about 1812, it later became a major route for settlers to Oregon and Washington. By 1820, however, a new "brigade-rendezvous" system sent company men in "brigades" cross-country on long expeditions, bypassing many tribes. It also encouraged "free trappers" to explore new regions on their own. At the end of the gathering season, the trappers would "rendezvous" and turn in their goods for pay at river ports along the

Green River, Upper Missouri, and the Upper Mississippi. St. Louis was the largest of the rendezvous towns. By 1830, however, fashions changed and beaver hats were replaced by silk hats, ending the demand for expensive American furs. Thus ended the era of the

mountain men, trappers, and scouts such as

Jedediah Smith,

Hugh Glass

Hugh Glass ( 1783 – 1833) was an American frontiersman, Trapping, fur trapper, trader, hunter and explorer. He is best known for his story of survival and forgiveness after being left for dead by companions when he was mauled by a grizzly bear ...

,

Davy Crockett

Colonel (United States), Colonel David Crockett (August 17, 1786 – March 6, 1836) was an American politician, militia officer and frontiersman. Often referred to in popular culture as the "King of the Wild Frontier", he represented Tennesse ...

,

Jack Omohundro, and others. The trade in beaver fur virtually ceased by 1845.

The federal government and westward expansion

There was wide agreement on the need to settle the new territories quickly, but the debate polarized over the price the government should charge. The conservatives and Whigs, typified by the president

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, wanted a moderated pace that charged the newcomers enough to pay the costs of the federal government. The Democrats, however, tolerated a wild scramble for land at very low prices. The final resolution came in the Homestead Law of 1862, with a moderated pace that gave settlers 160 acres free after they worked on it for five years.

The private

profit motive

In economics, the profit motive is the motivation of firms that operate so as to maximize their profits. Mainstream microeconomic theory posits that the ultimate goal of a business is "to make money" - not in the sense of increasing the firm ...

dominated the movement westward,

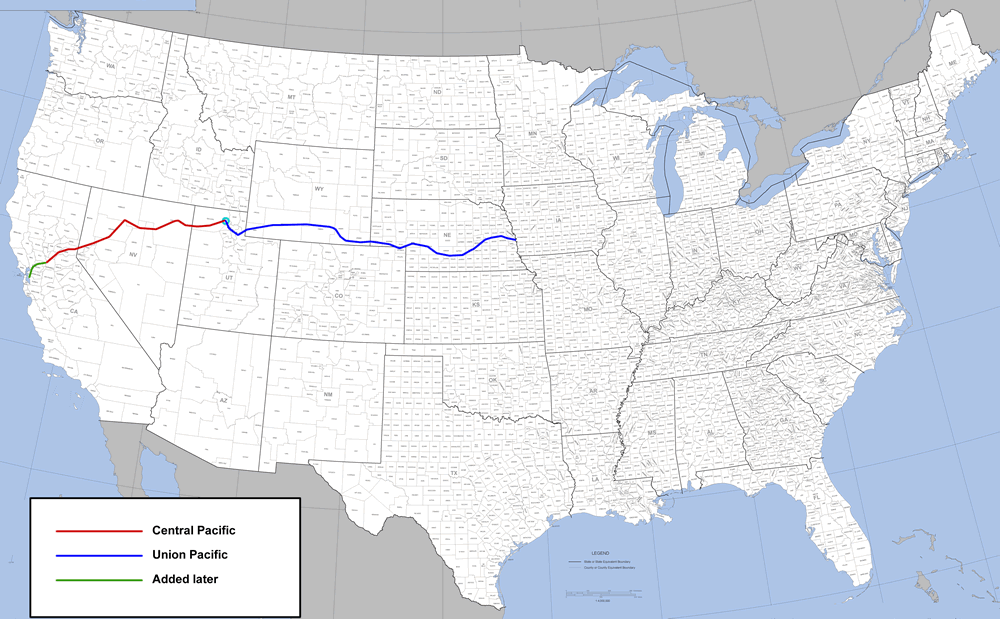

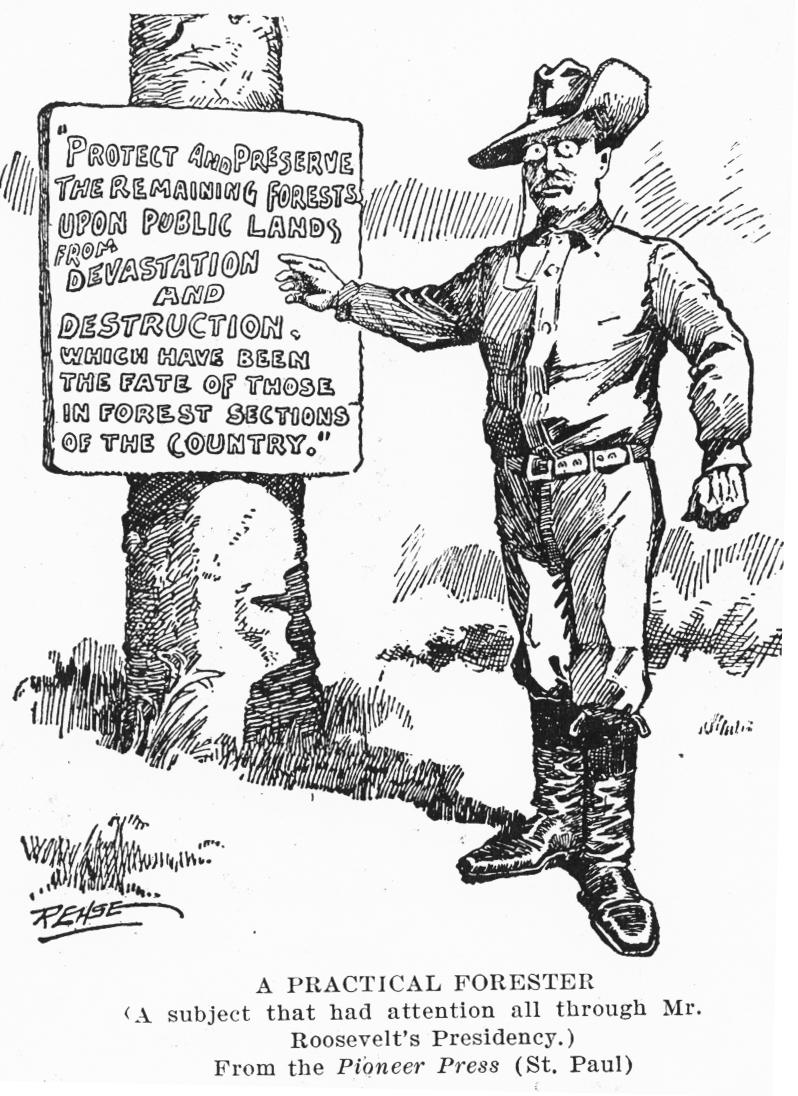

[Christine Bold, ''The Frontier Club: Popular Westerns and Cultural Power, 1880–1924'' (2013)] but the federal government played a supporting role in securing the land through treaties and setting up territorial governments, with governors appointed by the President. The federal government first acquired western territory through treaties with other nations or native tribes. Then it sent surveyors to map and document the land. By the 20th century, Washington bureaucracies managed the federal lands such as the

United States General Land Office

The General Land Office (GLO) was an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the United States government responsible for Public domain (land), public domain lands in the United States. It was created in 1812 ...

in the Interior Department, and after 1891, the

Forest Service in the Department of Agriculture. After 1900, dam building and flood control became major concerns.

Transportation was a key issue and the Army (especially the Army Corps of Engineers) was given full responsibility for facilitating navigation on the rivers. The steamboat, first used on the Ohio River in 1811, made possible inexpensive travel using the river systems, especially the Mississippi and Missouri rivers and their tributaries. Army expeditions up the Missouri River in 1818–1825 allowed engineers to improve the technology. For example, the Army's steamboat "

Western Engineer" of 1819 combined a very shallow draft with one of the earliest stern wheels. In 1819–1825, Colonel Henry Atkinson developed keelboats with hand-powered paddle wheels.

The

federal postal system played a crucial role in national expansion. It facilitated expansion into the West by creating an inexpensive, fast, convenient communication system. Letters from early settlers provided information and boosterism to encourage increased migration to the West, helped scattered families stay in touch and provide neutral help, assisted entrepreneurs to find business opportunities, and made possible regular commercial relationships between merchants and the West and wholesalers and factories back east. The postal service likewise assisted the Army in expanding control over the vast western territories. The widespread circulation of important newspapers by mail, such as the ''New York Weekly Tribune'', facilitated coordination among politicians in different states. The postal service helped to integrate already established areas with the frontier, creating a spirit of nationalism and providing a necessary infrastructure.

The army early on assumed the mission of protecting settlers along with the

Westward Expansion Trails, a policy that was described by

U.S. Secretary of War John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was an American politician who served as the List of governors of Virginia, 31st Governor of Virginia. Under president James Buchanan, he also served as the U.S. Secretary of War from 1857 ...

in 1857:

A line of posts running parallel without frontier, but near to the Indians' usual habitations, placed at convenient distances and suitable positions, and occupied by infantry, would exercise a salutary restraint upon the tribes, who would feel that any foray by their warriors upon the white settlements would meet with prompt retaliation upon their own homes.

There was a debate at the time about the best size for the forts with

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

,

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

, and

Thomas Jesup supporting forts that were larger but fewer in number than Floyd. Floyd's plan was more expensive but had the support of settlers and the general public who preferred that the military remain as close as possible. The frontier area was vast and even Davis conceded that "concentration would have exposed portions of the frontier to Native hostilities without any protection."

Scientists, artists, and explorers

Government and private enterprise sent many explorers to the West. In 1805–1806, Army lieutenant

Zebulon Pike (1779–1813) led a party of 20 soldiers to find the headwaters of the Mississippi. He later explored the Red and Arkansas Rivers in Spanish territory, eventually reaching the

Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( or ) in the United States or the Río Bravo (del Norte) in Mexico (), also known as Tó Ba'áadi in Navajo language, Navajo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the Southwestern United States a ...

. On his return, Pike sighted

the peak in Colorado named after him. Major

Stephen Harriman Long (1784–1864) led the Yellowstone and Missouri expeditions of 1819–1820, but his categorizing in 1823 of the

Great Plains

The Great Plains is a broad expanse of plain, flatland in North America. The region stretches east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, and grassland. They are the western part of the Interior Plains, which include th ...

as arid and useless led to the region getting a bad reputation as the "Great American Desert", which discouraged settlement in that area for several decades.

In 1811, naturalists

Thomas Nuttall

Thomas Nuttall (5 January 1786 – 10 September 1859) was an English botanist and zoologist who lived and worked in America from 1808 until 1841.

Nuttall was born in the village of Long Preston, near Settle in the West Riding of Yorkshire a ...

(1786–1859) and

John Bradbury (1768–1823) traveled up the Missouri River documenting and drawing plant and animal life. Artist

George Catlin (1796–1872) painted accurate paintings of Native American culture. Swiss artist

Karl Bodmer made compelling landscapes and portraits.

John James Audubon

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin, April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851) was a French-American Autodidacticism, self-trained artist, natural history, naturalist, and ornithology, ornithologist. His combined interests in art and ornitho ...

(1785–1851) is famous for classifying and painting in minute details 500 species of birds, published in ''Birds of America''.

The most famous of the explorers was

John Charles Frémont (1813–1890), an Army officer in the Corps of Topographical Engineers. He displayed a talent for exploration and a genius at self-promotion that gave him the sobriquet of "Pathmarker of the West" and led him to the presidential nomination of the new Republican Party in 1856. He led a series of expeditions in the 1840s which answered many of the outstanding geographic questions about the little-known region. He crossed through the Rocky Mountains by five different routes and mapped parts of Oregon and California. In 1846–1847, he played a role in conquering California. In 1848–1849, Frémont was assigned to locate a central route through the mountains for the proposed transcontinental railroad, but his expedition ended in near-disaster when it became lost and was trapped by heavy snow. His reports mixed narrative of exciting adventure with scientific data and detailed practical information for travelers. It caught the public imagination and inspired many to head west. Goetzman says it was "monumental in its breadth, a classic of exploring literature".

While colleges were springing up across the Northeast, there was little competition on the western frontier for

Transylvania University

Transylvania University is a private university in Lexington, Kentucky, United States. It was founded in 1780 and is the oldest university in Kentucky. It offers 46 major programs, as well as dual-degree engineering programs, and is Higher educ ...

, founded in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1780. It boasted of a law school in addition to its undergraduate and medical programs. Transylvania attracted politically ambitious young men from across the Southwest, including 50 who became United States senators, 101 representatives, 36 governors, and 34 ambassadors, as well as Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy.

Antebellum West

Religion

Most frontiersmen showed little commitment to religion until traveling evangelists began to appear and to produce "revivals". The local pioneers responded enthusiastically to these events and, in effect, evolved their populist religions, especially during the

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the late 18th to early 19th century in the United States. It spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching and sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a k ...

(1790–1840), which featured outdoor camp meetings lasting a week or more and which introduced many people to organized religion for the first time. One of the largest and most famous camp meetings took place at

Cane Ridge, Kentucky, in 1801.

The local Baptists set up small independent churches—Baptists abjured centralized authority; each local church was founded on the principle of independence of the local congregation. On the other hand, bishops of the well-organized, centralized Methodists assigned circuit riders to specific areas for several years at a time, then moved them to fresh territory. Several new denominations were formed, of which the largest was the

Disciples of Christ

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination in the United States and Canada. The denomination started with the Restoration Movement during the Second Great Awakening, first existing during the 19th ...

.

The established Eastern churches were slow to meet the needs of the frontier. The Presbyterians and Congregationalists, since they depended on well-educated ministers, were shorthanded in evangelizing the frontier. They set up a

Plan of Union of 1801 to combine resources on the frontier.

Democracy in the Midwest

Historian Mark Wyman calls Wisconsin a "palimpsest" of layer upon layer of peoples and forces, each imprinting permanent influences. He identified these layers as multiple "frontiers" over three centuries: Native American frontier, French frontier, English frontier, fur-trade frontier, mining frontier, and the logging frontier. Finally, the coming of the railroad brought the end of the frontier.

Frederick Jackson Turner grew up in Wisconsin during its last frontier stage, and in his travels around the state, he could see the layers of social and political development. One of Turner's last students,

Merle Curti used an in-depth analysis of local Wisconsin history to test Turner's thesis about democracy. Turner's view was that American democracy, "involved widespread participation in the making of decisions affecting the common life, the development of initiative and self-reliance, and equality of economic and cultural opportunity. It thus also involved Americanization of immigrant." Curti found that from 1840 to 1860 in Wisconsin the poorest groups gained rapidly in land ownership, and often rose to political leadership at the local level. He found that even landless young farmworkers were soon able to obtain their farms. Free land on the frontier, therefore, created opportunity and democracy, for both European immigrants as well as old stock Yankees.

Southwest

From the 1770s to the 1830s, pioneers moved into the new lands that stretched from Kentucky to Alabama to Texas. Most were farmers who moved in family groups.

Historian Louis Hacker shows how wasteful the first generation of pioneers was; they were too ignorant to cultivate the land properly and when the natural fertility of virgin land was used up, they sold out and moved west to try again. Hacker describes that in Kentucky about 1812:

Hacker adds that the second wave of settlers reclaimed the land, repaired the damage, and practiced more sustainable agriculture. Historian

Frederick Jackson Turner explored the individualistic worldview and values of the first generation:

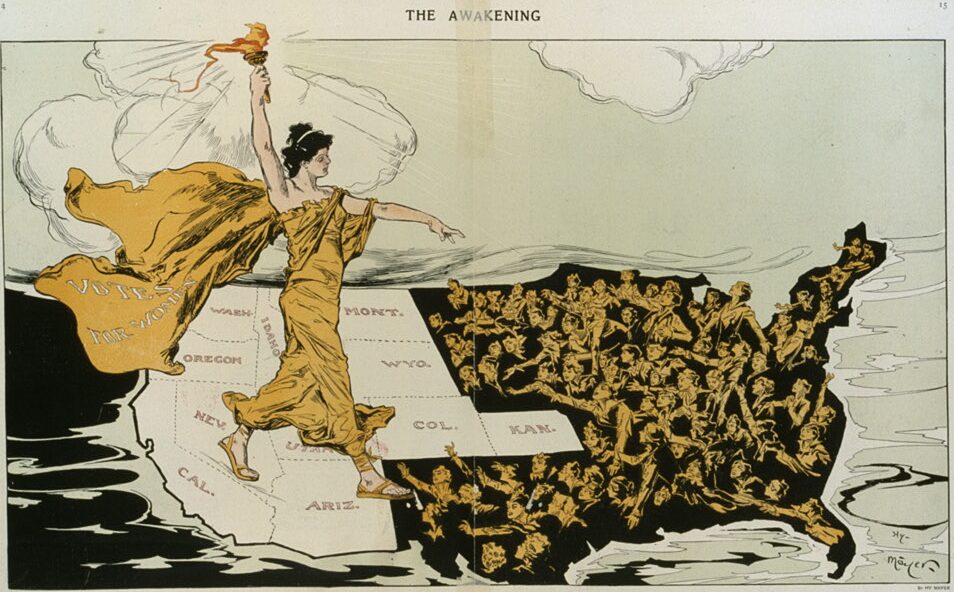

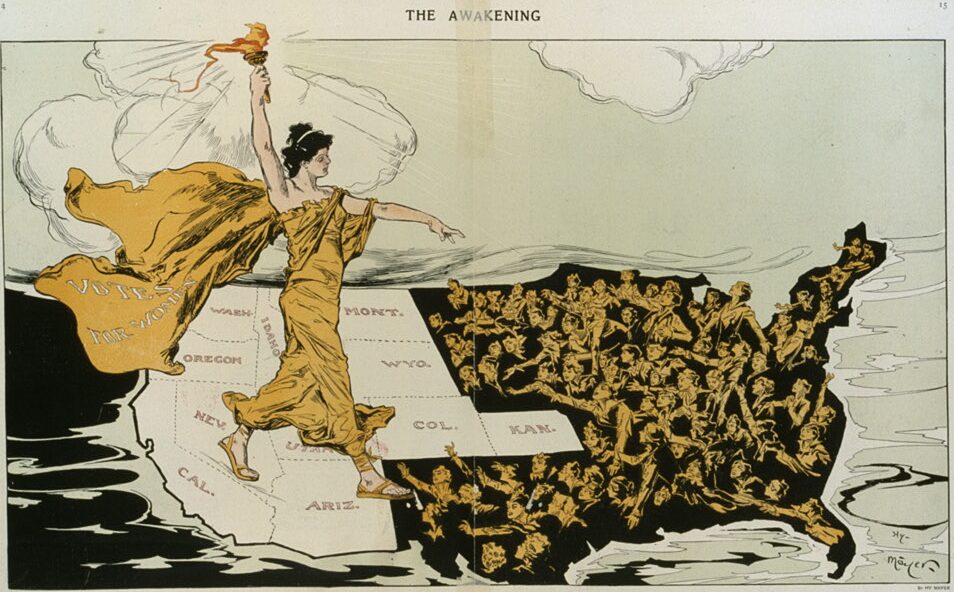

Manifest destiny

Manifest Destiny was the controversial belief that the United States was preordained to expand from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific coast, and efforts made to realize that belief. The concept has appeared during colonial times, but the term was coined in the 1840s by a popular magazine which editorialized, "the fulfillment of our manifest destiny...to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions." As the nation grew, "Manifest Destiny" became a rallying cry for expansionists in the Democratic Party. In the 1840s, the Tyler and Polk administrations (1841–1849) successfully promoted this nationalistic doctrine. However, the

Whig Party, which represented business and financial interests, stood opposed to Manifest Destiny. Whig leaders such as

Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

and

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

called for deepening the society through modernization and urbanization instead of simple horizontal expansion. Starting with the annexation of Texas, the expansionists got the upper hand.

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, an anti-slavery Whig, felt the Texas annexation in 1845 to be "the heaviest calamity that ever befell myself and my country".

Helping settlers move westward were the emigrant "guide books" of the 1840s featuring route information supplied by the fur traders and the Frémont expeditions, and promising fertile farmland beyond the Rockies.

[, For example, see ]

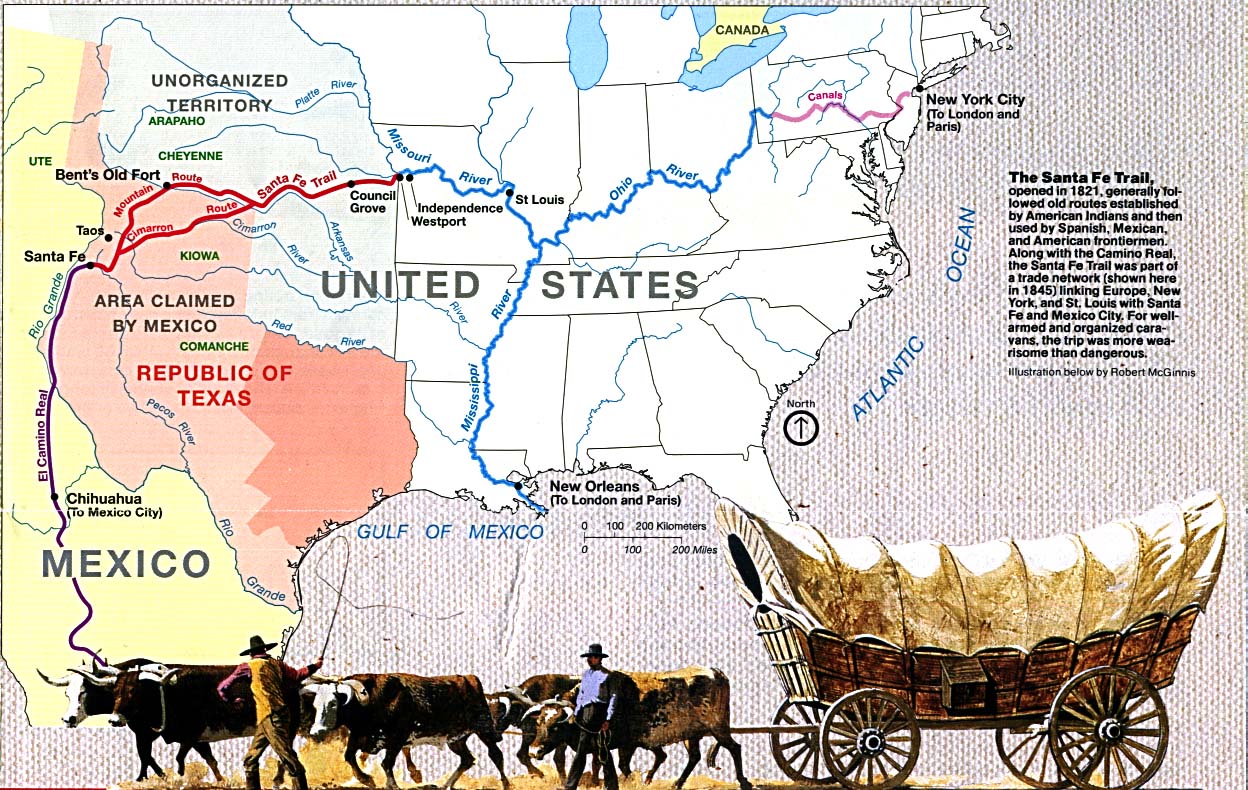

Mexico and Texas

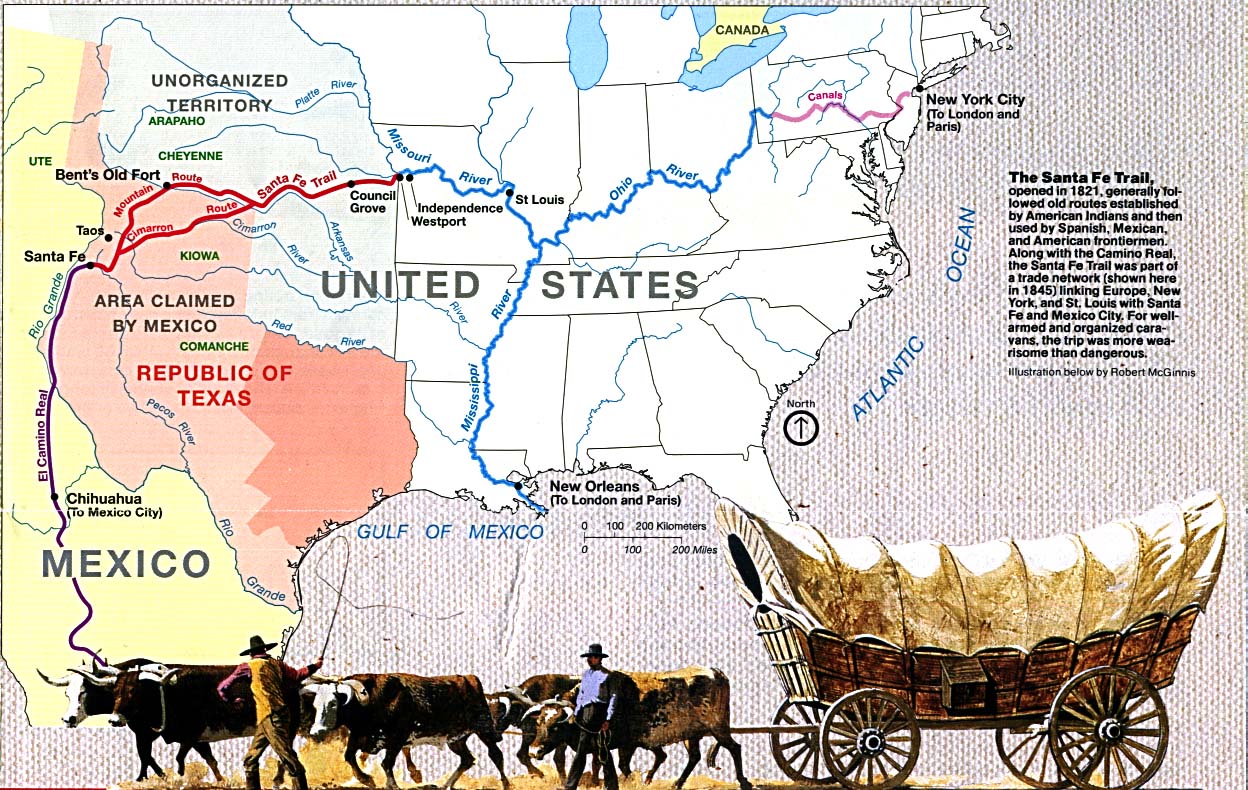

Mexico became independent of Spain in 1821 and took over Spain's northern possessions stretching from Texas to California. American caravans began delivering goods to the Mexican city

Santa Fe along the

Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail was a 19th-century route through central North America that connected Franklin, Missouri, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. Pioneered in 1821 by William Becknell, who departed from the Boonslick region along the Missouri River, the ...

, over the journey which took 48 days from Kansas City, Missouri (then known as Westport). Santa Fe was also the trailhead for the "El Camino Real" (the King's Highway), a trade route which carried American manufactured goods southward deep into Mexico and returned silver, furs, and mules northward (not to be confused with another "Camino Real" which connected the missions in California). A branch also ran eastward near the Gulf (also called the

Old San Antonio Road). Santa Fe connected to California via the

Old Spanish Trail.

The Spanish and Mexican governments attracted American settlers to Texas with generous terms.

Stephen F. Austin became an "empresario", receiving contracts from the Mexican officials to bring in immigrants. In doing so, he also became the ''de facto'' political and military commander of the area. Tensions rose, however, after an abortive attempt to establish the independent nation of

Fredonia in 1826.

William Travis, leading the "war party", advocated for independence from Mexico, while the "peace party" led by Austin attempted to get more autonomy within the current relationship. When Mexican president

Santa Anna shifted alliances and joined the conservative Centralist party, he declared himself dictator and ordered soldiers into Texas to curtail new immigration and unrest. However, immigration continued and 30,000 Anglos with 3,000 slaves were settled in Texas by 1835. In 1836, the

Texas Revolution

The Texas Revolution (October 2, 1835 – April 21, 1836) was a rebellion of colonists from the United States and Tejanos (Hispanic Texans) against the Centralist Republic of Mexico, centralist government of Mexico in the Mexican state of ...

erupted. Following losses at the

Alamo and

Goliad, the

Texians won the decisive

Battle of San Jacinto to secure independence. At San Jacinto,

Sam Houston

Samuel Houston (, ; March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two indi ...

, commander-in-chief of the Texian Army and future

President of the Republic of Texas famously shouted "Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad". The U.S. Congress declined to annex Texas, stalemated by contentious arguments over slavery and regional power. Thus, the

Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

remained an independent power for nearly a decade before it was annexed as the 28th state in 1845. The government of Mexico, however, viewed Texas as a runaway province and asserted its ownership.

Mexican–American War

Mexico refused to recognize the independence of Texas in 1836, but the U.S. and European powers did so. Mexico threatened war if Texas joined the U.S., which it did in 1845. American negotiators were turned away by a Mexican government in turmoil. When the Mexican army killed 16 American soldiers in disputed territory war was at hand.

Whigs such as Congressman

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

denounced the war, but it was quite popular outside New England.

The Mexican strategy was defensive; the American strategy was a three-pronged offensive, using large numbers of volunteer soldiers. Overland forces seized New Mexico with little resistance and headed to California, which quickly fell to the American land and naval forces. From the main American base at New Orleans, General

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

led forces into northern Mexico, winning a series of battles that ensued. The U.S. Navy transported General

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

to

Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

. He then marched his 12,000-man force west to Mexico City, winning the final battle at Chapultepec. Talk of acquiring all of Mexico fell away when the army discovered the Mexican political and cultural values were so alien to America's. As the ''Cincinnati Herald'' asked, what would the U.S. do with eight million Mexicans "with their idol worship, heathen superstition, and degraded mongrel races?"

The

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848 ceded the territories of California and New Mexico to the United States for $18.5 million (which included the assumption of claims against Mexico by settlers). The

Gadsden Purchase in 1853 added southern Arizona, which was needed for a railroad route to California. In all Mexico ceded half a million square miles (1.3 million km

2) and included the states-to-be of California, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming, in addition to Texas. Managing the new territories and dealing with the slavery issue caused intense controversy, particularly over the

Wilmot Proviso, which would have outlawed slavery in the new territories. Congress never passed it, but rather temporarily resolved the issue of slavery in the West with the

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

. California entered the Union in 1850 as a free state; the other areas remained territories for many years.

Growth of Texas

The new state grew rapidly as migrants poured into the fertile cotton lands of east Texas. German immigrants started to arrive in the early 1840s because of negative economic, social, and political pressures in Germany. With their investments in cotton lands and slaves, planters established cotton plantations in the eastern districts. The central area of the state was developed more by subsistence farmers who seldom owned slaves.

Texas in its Wild West days attracted men who could shoot straight and possessed the zest for adventure, "for masculine renown, patriotic service, martial glory, and meaningful deaths".

California gold rush

In 1846, about 10,000 Californios (Hispanics) lived in California, primarily on cattle ranches in what is now the Los Angeles area. A few hundred foreigners were scattered in the northern districts, including some Americans. With the outbreak of war with Mexico in 1846 the U.S. sent in Frémont and a

U.S. Army unit, as well as naval forces, and quickly took control. As the war was ending, gold was discovered in the north, and the word soon spread worldwide.

Thousands of "

forty-niners" reached California, by sailing around South America (or taking a short-cut through disease-ridden Panama), or walked the California trail. The population soared to over 200,000 in 1852, mostly in the gold districts that stretched into the mountains east of San Francisco.

Housing in San Francisco was at a premium, and abandoned ships whose crews had headed for the mines were often converted to temporary lodging. In the goldfields themselves, living conditions were primitive, though the mild climate proved attractive. Supplies were expensive and food poor, typical diets consisting mostly of pork, beans, and whiskey. These highly male, transient communities with no established institutions were prone to high levels of violence, drunkenness, profanity, and greed-driven behavior. Without courts or law officers in the mining communities to enforce claims and justice, miners developed their ad hoc legal system, based on the "mining codes" used in other mining communities abroad. Each camp had its own rules and often handed out justice by popular vote, sometimes acting fairly and at times exercising vigilantes; with Native Americans (Indians), Mexicans, and Chinese generally receiving the harshest sentences.

The gold rush radically changed the California economy and brought in an array of professionals, including precious metal specialists, merchants, doctors, and attorneys, who added to the population of miners, saloon keepers, gamblers, and prostitutes. A San Francisco newspaper stated, "The whole country... resounds to the sordid cry of gold! Gold! ''Gold!'' while the field is left half planted, the house half-built, and everything neglected but the manufacture of shovels and pickaxes." Over 250,000 miners found a total of more than $200 million in gold in the five years of the California gold rush.

[Howard R. Lamar (1977), pp. 446–447] As thousands arrived, however, fewer and fewer miners struck their fortune, and most ended exhausted and broke.

Violent bandits often preyed upon the miners, such as the case of

Jonathan R. Davis' killing of eleven bandits single-handedly.

[Fournier, Richard. "Mexican War Vet Wages Deadliest Gunfight in American History", ''VFW Magazine'' (January 2012), p. 30.] Camps spread out north and south of the

American River

The American River is a List of rivers of California, river in California that runs from the Sierra Nevada (U.S.), Sierra Nevada mountain range to its confluence with the Sacramento River in downtown Sacramento. Via the Sacramento River, it ...

and eastward into the

Sierras. In a few years, nearly all of the independent miners were displaced as mines were purchased and run by mining companies, who then hired low-paid salaried miners. As gold became harder to find and more difficult to extract, individual prospectors gave way to paid work gangs, specialized skills, and mining machinery. Bigger mines, however, caused greater environmental damage. In the mountains, shaft mining predominated, producing large amounts of waste. Beginning in 1852, at the end of the '49 gold rush, through 1883,

hydraulic mining

Hydraulic mining is a form of mining that uses high-pressure jets of water to dislodge rock material or move sediment.Paul W. Thrush, ''A Dictionary of Mining, Mineral, and Related Terms'', US Bureau of Mines, 1968, p.560. In the placer mining of ...

was used. Despite huge profits being made, it fell into the hands of a few capitalists, displaced numerous miners, vast amounts of waste entered river systems, and did heavy ecological damage to the environment. Hydraulic mining ended when the public outcry over the destruction of farmlands led to the outlawing of this practice.

The mountainous areas of the triangle from New Mexico to California to

South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

contained hundreds of hard rock mining sites, where prospectors discovered gold, silver, copper and other minerals (as well as some soft-rock coal). Temporary mining camps sprang up overnight; most became

ghost towns when the ores were depleted. Prospectors spread out and hunted for gold and silver along the Rockies and in the southwest. Soon gold was discovered in

Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Idaho, Montana, and South Dakota (by 1864).

The discovery of the

Comstock Lode

The Comstock Lode is a lode of silver ore located under the eastern slope of Mount Davidson, a peak in the Virginia Range in Virginia City, Nevada (then western Utah Territory), which was the first major discovery of silver ore in the U ...

, containing vast amounts of silver, resulted in the Nevada boomtowns of

Virginia City,

Carson City

Carson City, officially the Carson City Consolidated Municipality, is an independent city and the capital of the U.S. state of Nevada. As of the 2020 census, the population was 58,639, making it the 6th most populous city in the state. The m ...

, and

Silver City. The wealth from silver, more than from gold, fueled the maturation of San Francisco in the 1860s and helped the rise of some of its wealthiest families, such as that of

George Hearst

George Hearst (September 3, 1820 – February 28, 1891) was an American businessman, politician, and patriarch of the Hearst family, Hearst business dynasty. After growing up on a small farm in Missouri, he founded many mining operations a ...

.

Oregon Trail

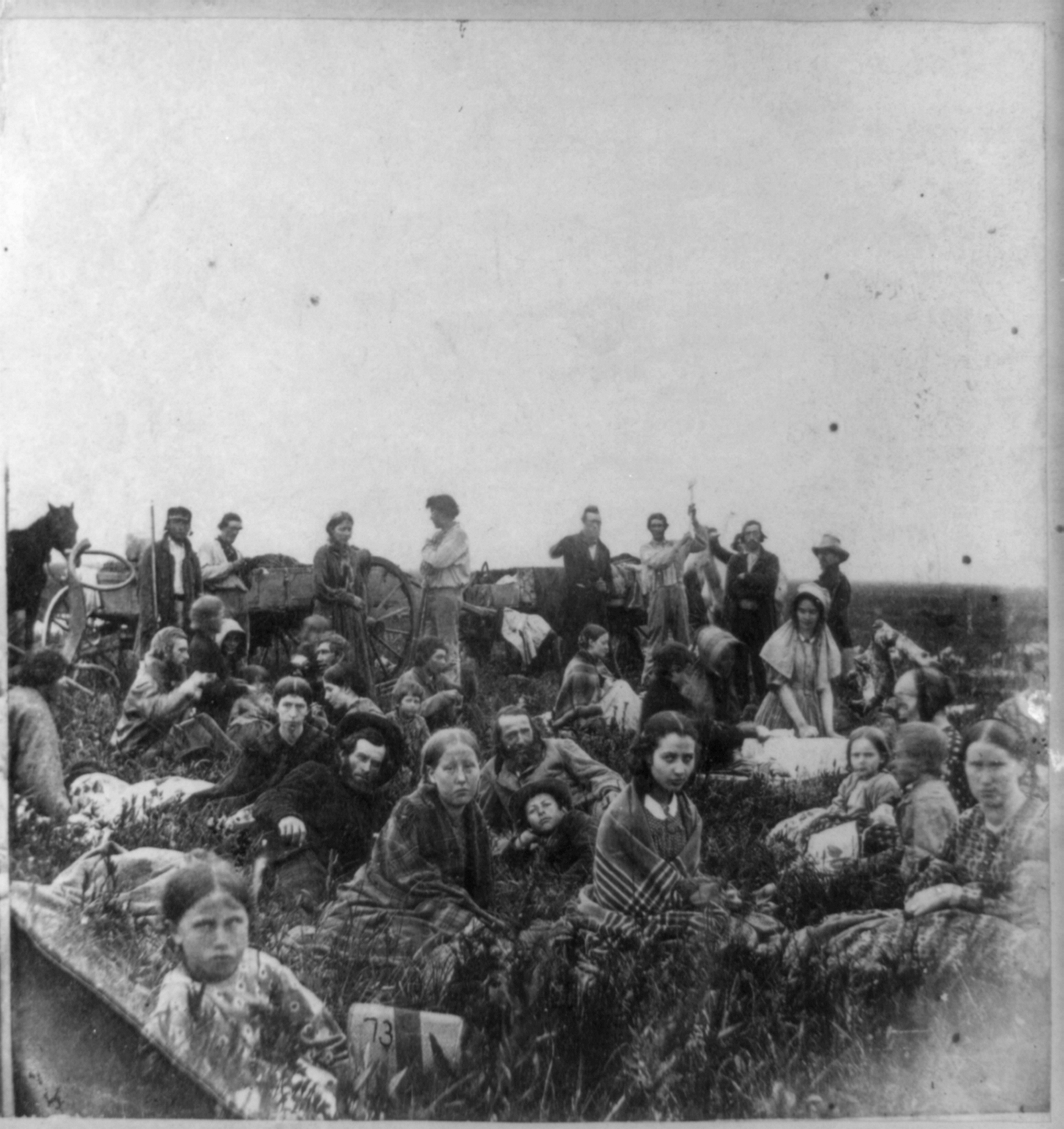

To get to the rich new lands of the West Coast, there were three options: some sailed around the southern tip of South America during a six-month voyage, some took the treacherous journey across the Panama Isthmus, but 400,000 others walked there on an overland route of more than 2,000 miles (3,200 km); their wagon trains usually left from Missouri. They moved in large groups under an experienced wagonmaster, bringing their clothing, farm supplies, weapons, and animals. These wagon trains followed major rivers, crossed prairies and mountains, and typically ended in Oregon and California. Pioneers generally attempted to complete the journey during a single warm season, usually for six months. By 1836, when the first migrant wagon train was organized in

Independence, Missouri

Independence is a city in and one of two county seats of Jackson County, Missouri, United States. It is a satellite city of Kansas City, Missouri, and is the largest suburb on the Missouri side of the Kansas City metropolitan area. In 2020 Unite ...

, a wagon trail had been cleared to

Fort Hall, Idaho. Trails were cleared further and further west, eventually reaching the

Willamette Valley in Oregon. This network of wagon trails leading to the Pacific Northwest was later called the

Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and Westward Expansion Trails, emigrant trail in North America that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon Territory. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail crossed what ...

. The eastern half of the route was also used by travelers on the

California Trail (from 1843),

Mormon Trail (from 1847), and

Bozeman Trail (from 1863) before they turned off to their separate destinations.

In the "Wagon Train of 1843", some 700 to 1,000 emigrants headed for Oregon; missionary

Marcus Whitman led the wagons on the last leg. In 1846, the

Barlow Road was completed around Mount Hood, providing a rough but passable wagon trail from the Missouri River to the Willamette Valley: about 2,000 miles (3,200 km). Though the main direction of travel on the early wagon trails was westward, people also used the Oregon Trail to travel eastward. Some did so because they were discouraged and defeated. Some returned with bags of gold and silver. Most were returning to pick up their families and move them all back west. These "gobacks" were a major source of information and excitement about the wonders and promises—and dangers and disappointments—of the far West.

Not all emigrants made it to their destination. The dangers of the overland route were numerous: snakebites, wagon accidents, violence from other travelers, suicide, malnutrition, stampedes, Native attacks, a variety of diseases (

dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

,

typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often ther ...

, and

cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

were among the most common), exposure, avalanches, etc. One particularly well-known example of the treacherous nature of the journey is the story of the ill-fated

Donner Party

The Donner Party, sometimes called the Donner–Reed Party, was a group of American pioneers who migrated to California interim government, 1846-1850, California in a wagon train from the Midwest. Delayed by a multitude of mishaps, they spent ...

, which became trapped in the

Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada ( ) is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primari ...

mountains during the winter of 1846–1847. Half of the 90 people traveling with the group died from starvation and exposure, and some resorted to cannibalism to survive. Another story of cannibalism featured

Alferd Packer and his trek to

Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

in 1874. There were also frequent attacks from bandits and

highwaymen, such as the infamous

Harpe brothers who patrolled the frontier routes and targeted migrant groups.

Mormons and Utah

In Missouri and Illinois,

animosity between the Mormon settlers and locals grew, which would mirror those in other states such as Utah years later. Violence finally erupted on October 24, 1838, when militias from both sides

clashed and a

mass killing of Mormons in Livingston County occurred 6 days later. A

Mormon Extermination Order was filed during these conflicts, and the Mormons were forced to scatter.

Brigham Young

Brigham Young ( ; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) from 1847 until h ...

, seeking to leave American jurisdiction to escape religious persecution in Illinois and Missouri, led the

Mormons

Mormons are a Religious denomination, religious and ethnocultural group, cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's d ...

to the valley of the

Great Salt Lake

The Great Salt Lake is the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere and the eighth-largest terminal lake in the world. It lies in the northern part of the U.S. state of Utah and has a substantial impact upon the local climate, partic ...

, owned at the time by Mexico but not controlled by them. A hundred rural Mormon settlements sprang up in what Young called "

Deseret", which he ruled as a theocracy. It later became Utah Territory. Young's

Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City, often shortened to Salt Lake or SLC, is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Utah. It is the county seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in the state. The city is the core of the Salt Lake Ci ...

settlement served as the hub of their network, which reached into neighboring territories as well. The communalism and advanced farming practices of the Mormons enabled them to succeed. The Mormons often sold goods to wagon trains passing through. After the

Battle at Fort Utah in 1850, Brigham Young began to articulate an Indian policy often paraphrased as "It is cheaper to feed them than to fight them." However,

Wakara's War and Utah's

Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the United States and Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans led by Black Hawk (Sauk leader), Black Hawk, a Sauk people, Sauk leader. The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of ...

demonstrate that hostilities persisted until federal and territorial leaders came to agree that the nearby Indigenous people should all be displaced to the Uinta Reservation. Education became a high priority to protect the beleaguered group, reduce heresy and maintain group solidarity.

Following the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, Utah was ceded to the United States by Mexico. Though the Mormons in Utah had supported U.S. efforts during the war; the federal government, pushed by the Protestant churches, rejected theocracy and polygamy. Founded in 1852, the Republican Party was openly hostile towards

the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Restorationism, restorationist Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, denomination and the ...

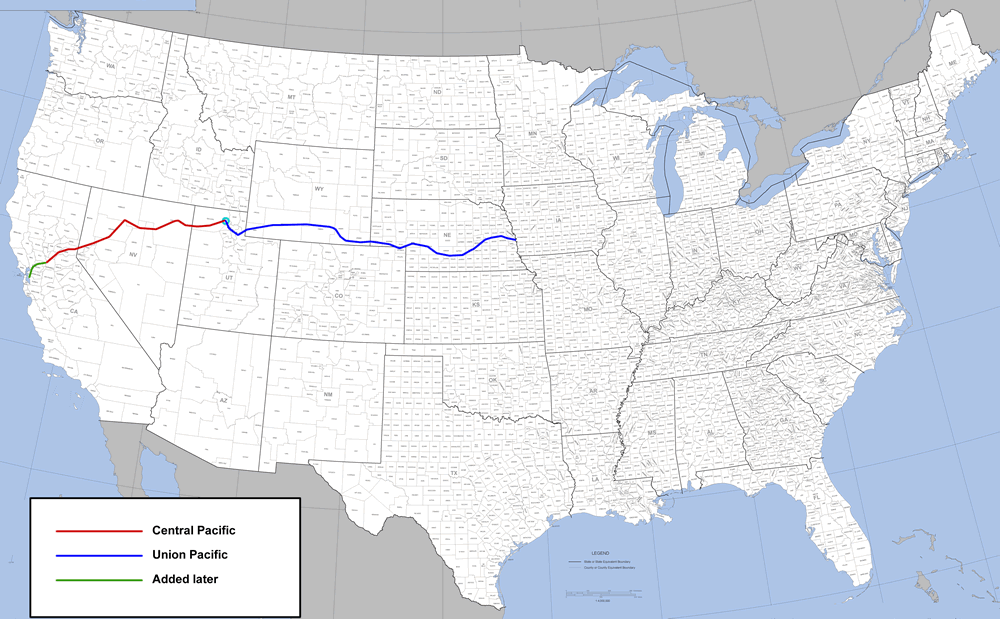

(LDS Church) in Utah over the practice of polygamy, viewed by most of the American public as an affront to religious, cultural, and moral values of modern civilization.