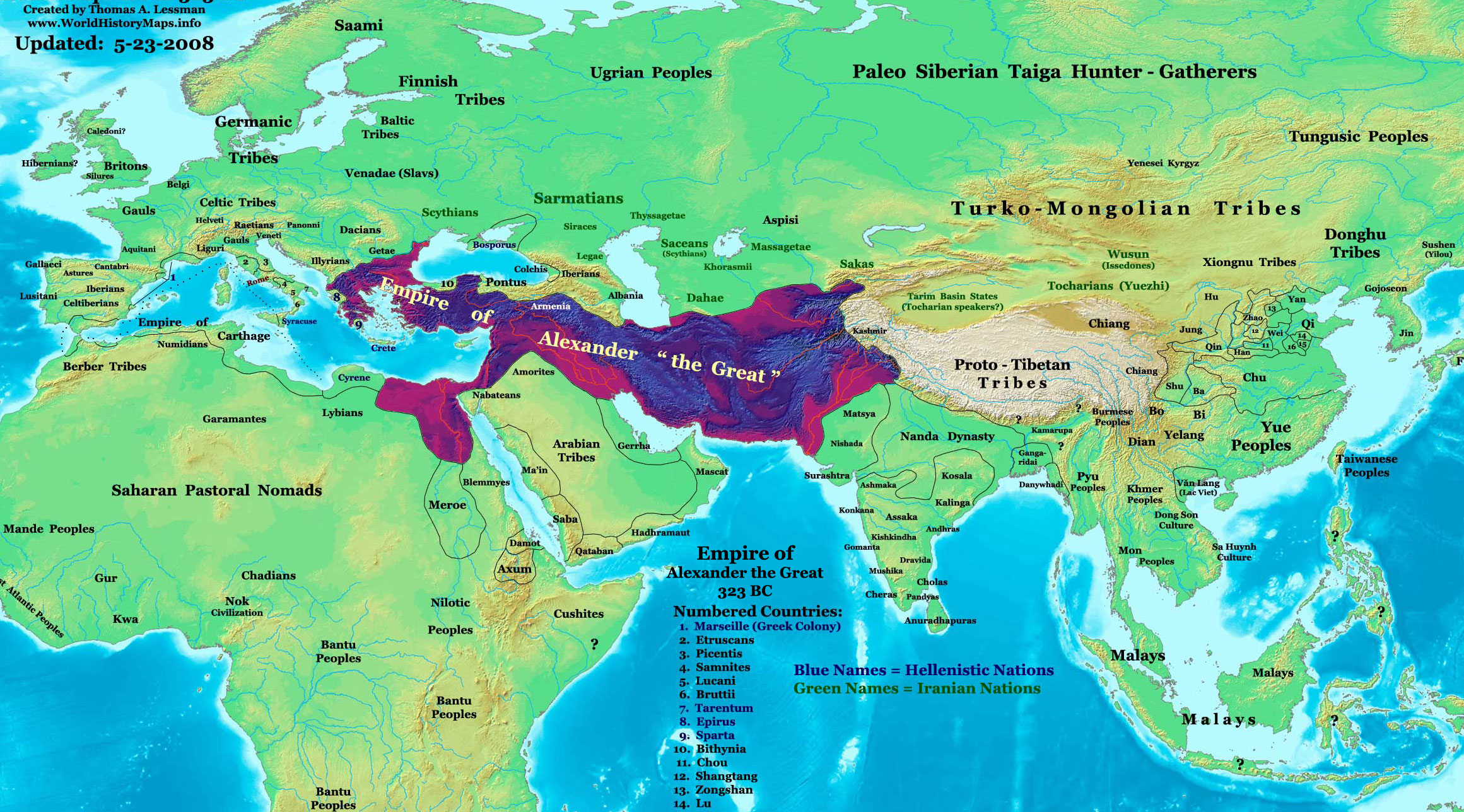

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

kingdom of

Macedon

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

. He succeeded his father

Philip II to the throne in 336 BC at the age of 20 and spent most of his ruling years conducting

a lengthy military campaign throughout

Western Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

,

Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

, parts of

South Asia

South Asia is the southern Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia that is defined in both geographical and Ethnicity, ethnic-Culture, cultural terms. South Asia, with a population of 2.04 billion, contains a quarter (25%) of the world's populatio ...

, and

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. By the age of 30, he had created one of the

largest empires

Several empires in human history have been contenders for the largest of all time, depending on definition and mode of measurement. Possible ways of measuring size include area, population, economy, and power. Of these, area is the most commonly ...

in history, stretching from

Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

to northwestern

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. He was undefeated in battle and is widely considered to be one of history's greatest and most successful military commanders.

Until the age of 16, Alexander was tutored by

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

. In 335 BC, shortly after his assumption of kingship over Macedon, he

campaigned in the Balkans and reasserted control over

Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

and parts of

Illyria

In classical and late antiquity, Illyria (; , ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; , ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyrians.

The Ancient Gree ...

before marching on the city of

Thebes Thebes or Thebae may refer to one of the following places:

*Thebes, Egypt, capital of Egypt under the 11th, early 12th, 17th and early 18th Dynasties

*Thebes, Greece, a city in Boeotia

*Phthiotic Thebes

Phthiotic Thebes ( or Φθιώτιδες Θ ...

, which was

subsequently destroyed in battle. Alexander then led the

League of Corinth

The League of Corinth, also referred to as the Hellenic League (, ''koinòn tõn Hellḗnōn''; or simply , ''the Héllēnes''), was a federation of Greek states created by Philip IIDiodorus Siculus, Book 16, 89. «διόπερ ἐν Κορί� ...

, and used his authority to launch the

pan-Hellenic project envisaged by his father, assuming leadership over all

Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

in their conquest of

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

.

In 334 BC, he invaded the

Achaemenid Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, it was the larges ...

and began

a series of campaigns that lasted for 10 years. Following his conquest of

Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

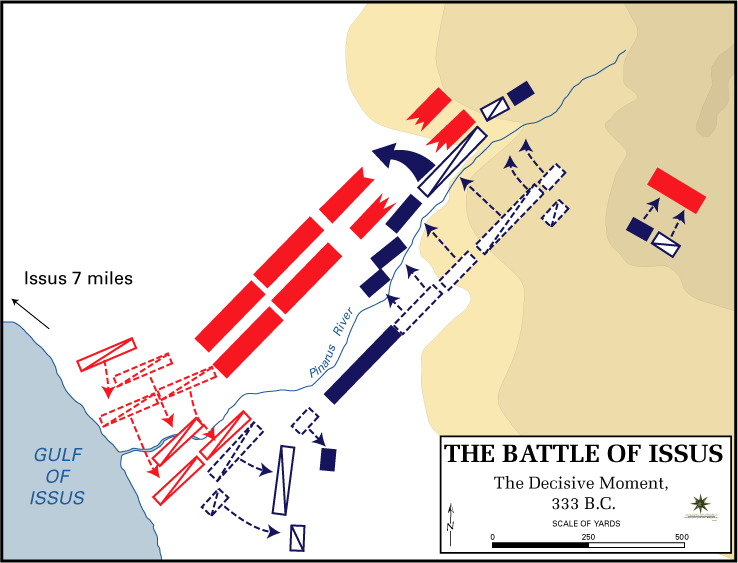

, Alexander broke the power of Achaemenid Persia in a series of decisive battles, including those at

Issus and

Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela ( ; ), also called the Battle of Arbela (), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Ancient Macedonian army, Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great and the Achaemenid Army, Persian Army under Darius III, ...

; he subsequently overthrew

Darius III

Darius III ( ; ; – 330 BC) was the thirteenth and last Achaemenid King of Kings of Persia, reigning from 336 BC to his death in 330 BC.

Contrary to his predecessor Artaxerxes IV Arses, Darius was a distant member of the Achaemenid dynasty. ...

and conquered the Achaemenid Empire in its entirety. After the fall of Persia, the

Macedonian Empire

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

held a vast swath of territory between the

Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

and the

Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayas, Himalayan river of South Asia, South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in the Western Tibet region of China, flows northw ...

. Alexander endeavored to reach the "ends of the world and the Great Outer Sea" and

invaded India in 326 BC, achieving an important victory over

Porus

Porus or Poros ( ; 326–321 BC) was an ancient Indian king whose territory spanned the region between the Jhelum River (Hydaspes) and Chenab River (Acesines), in the Punjab region of what is now India and Pakistan. He is only mentioned in Gr ...

, an ancient Indian king of present-day

Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

, at the

Battle of the Hydaspes

The Battle of the Hydaspes also known as Battle of Jhelum, or First Battle of Jhelum, was fought between the Macedonian Empire under Alexander the Great and the Pauravas under Porus in May of 326 BCE. It took place on the banks of the Hydas ...

. Due to the mutiny of his homesick troops, he eventually turned back at the

Beas River and later died in 323 BC in

Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

, the city of

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

that he had planned to establish as his empire's capital.

Alexander's death left unexecuted an additional series of planned military and mercantile campaigns that would have begun with a Greek invasion of

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

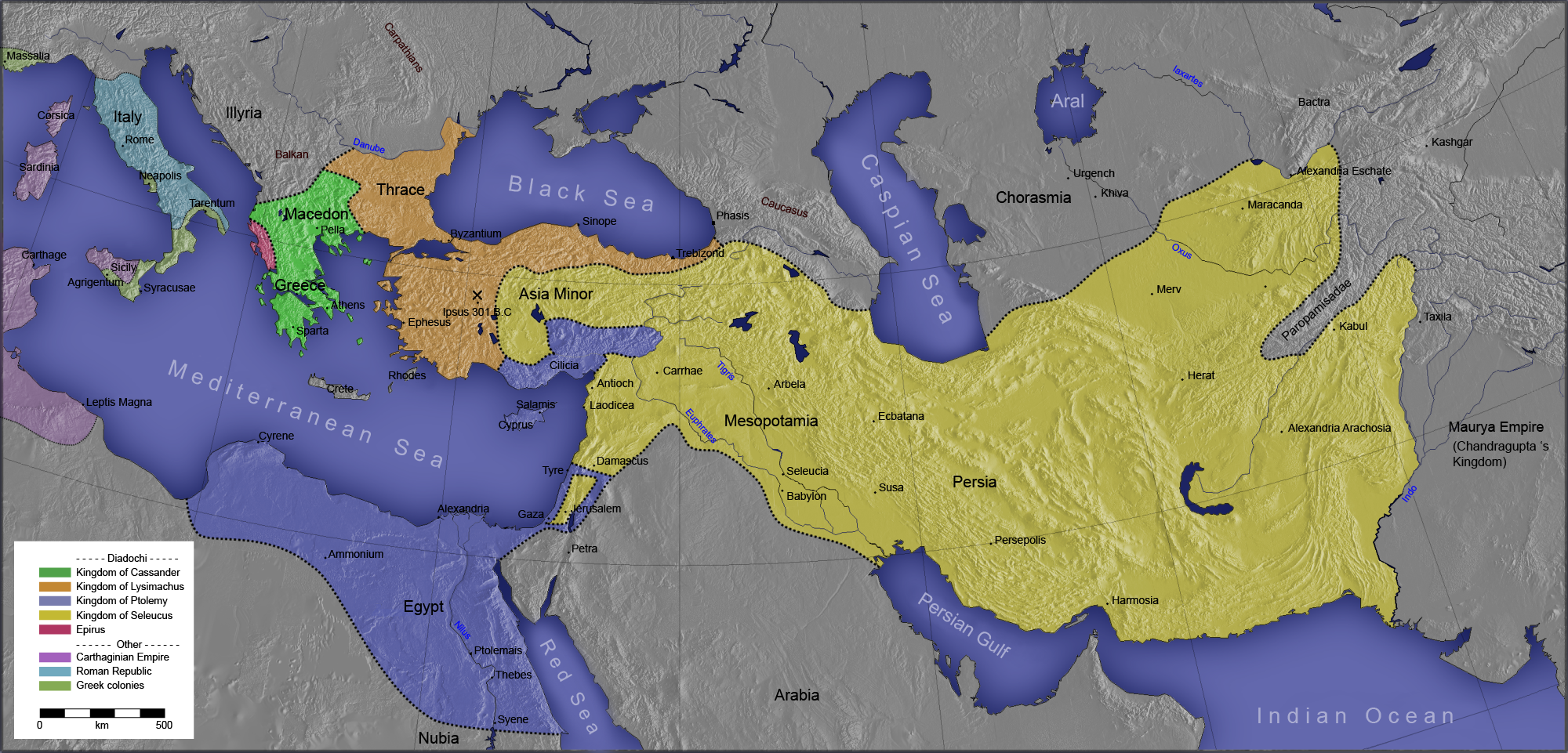

. In the years following his death,

a series of civil wars broke out across the Macedonian Empire, eventually leading to its disintegration at the hands of the

Diadochi

The Diadochi were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The Wars of the Diadochi mark the beginning of the Hellenistic period from the Mediterran ...

.

With his death marking the start of the

Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

, Alexander's legacy includes the

cultural diffusion

In cultural anthropology and cultural geography, cultural diffusion, as conceptualized by Leo Frobenius in his 1897/98 publication ''Der westafrikanische Kulturkreis'', is the spread of cultural items—such as ideas, styles, religions, technolo ...

and

syncretism

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various school of thought, schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or religious assimilation, assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the ...

that his conquests engendered, such as

Greco-Buddhism

Greco-Buddhism or Graeco-Buddhism was a cultural syncretism between Hellenistic culture and Buddhism developed between the 4th century BC and the 5th century AD in Gandhara, which was in present-day Pakistan and parts of north-east Afghanis ...

and

Hellenistic Judaism

Hellenistic Judaism was a form of Judaism in classical antiquity that combined Jewish religious tradition with elements of Hellenistic culture and religion. Until the early Muslim conquests of the eastern Mediterranean, the main centers of Hellen ...

.

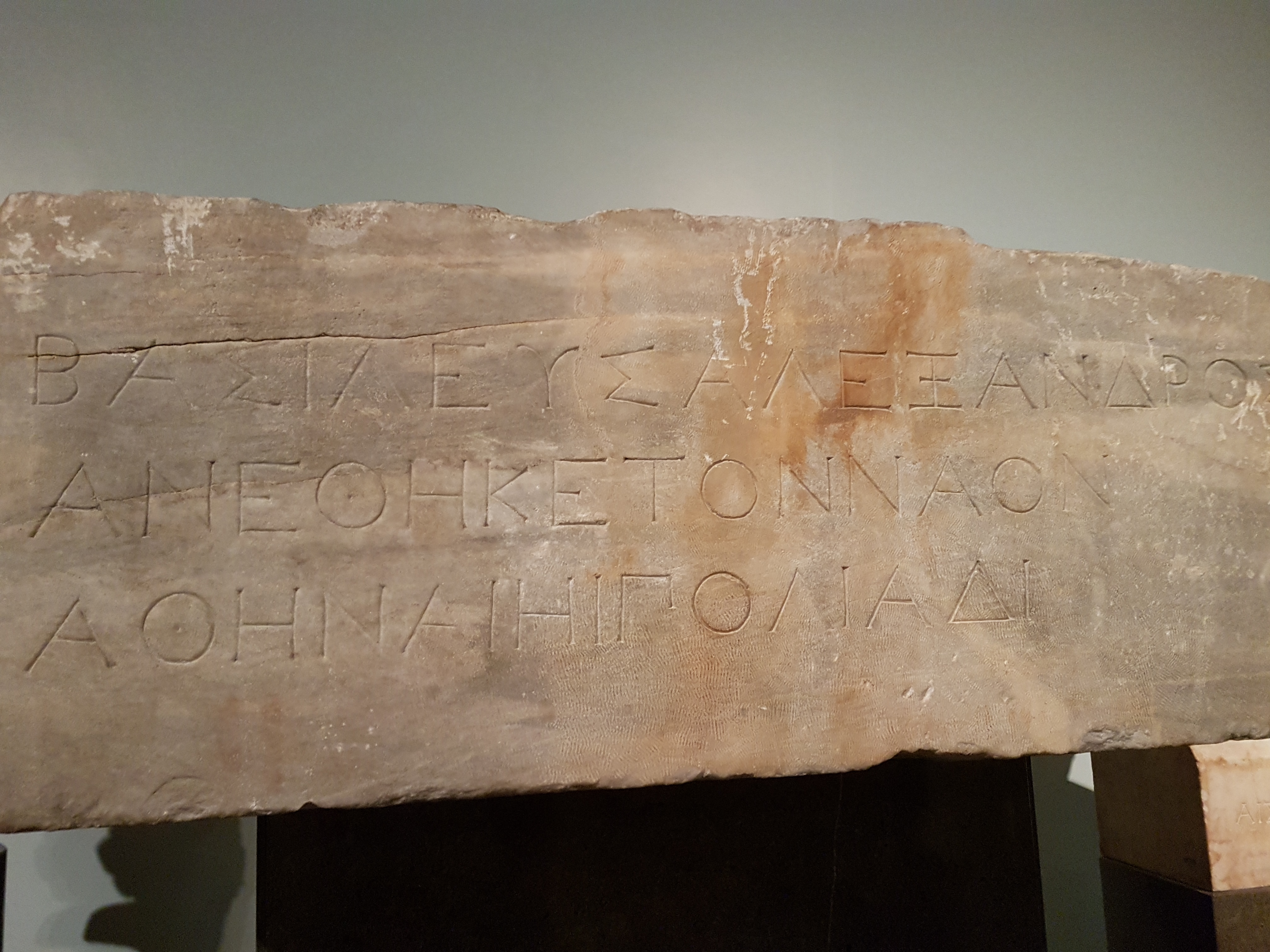

He founded more than twenty cities, with the most prominent being the city of

Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

in Egypt. Alexander's settlement of

Greek colonists and the resulting spread of

Greek culture

The culture of Greece has evolved over thousands of years, beginning in Minoan and later in Mycenaean Greece, continuing most notably into Classical Greece, while influencing the Roman Empire and its successor the Byzantine Empire. Other cultu ...

led to the overwhelming dominance of

Hellenistic civilization

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

and influence as far east as the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

. The Hellenistic period developed through the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

into modern

Western culture

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the Cultural heritage, internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompas ...

; the

Greek language

Greek (, ; , ) is an Indo-European languages, Indo-European language, constituting an independent Hellenic languages, Hellenic branch within the Indo-European language family. It is native to Greece, Cyprus, Italy (in Calabria and Salento), south ...

became the ''

lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, link language or language of wider communication (LWC), is a Natural language, language systematically used to make co ...

'' of the region and was the predominant language of the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

until its collapse in the mid-15th century AD.

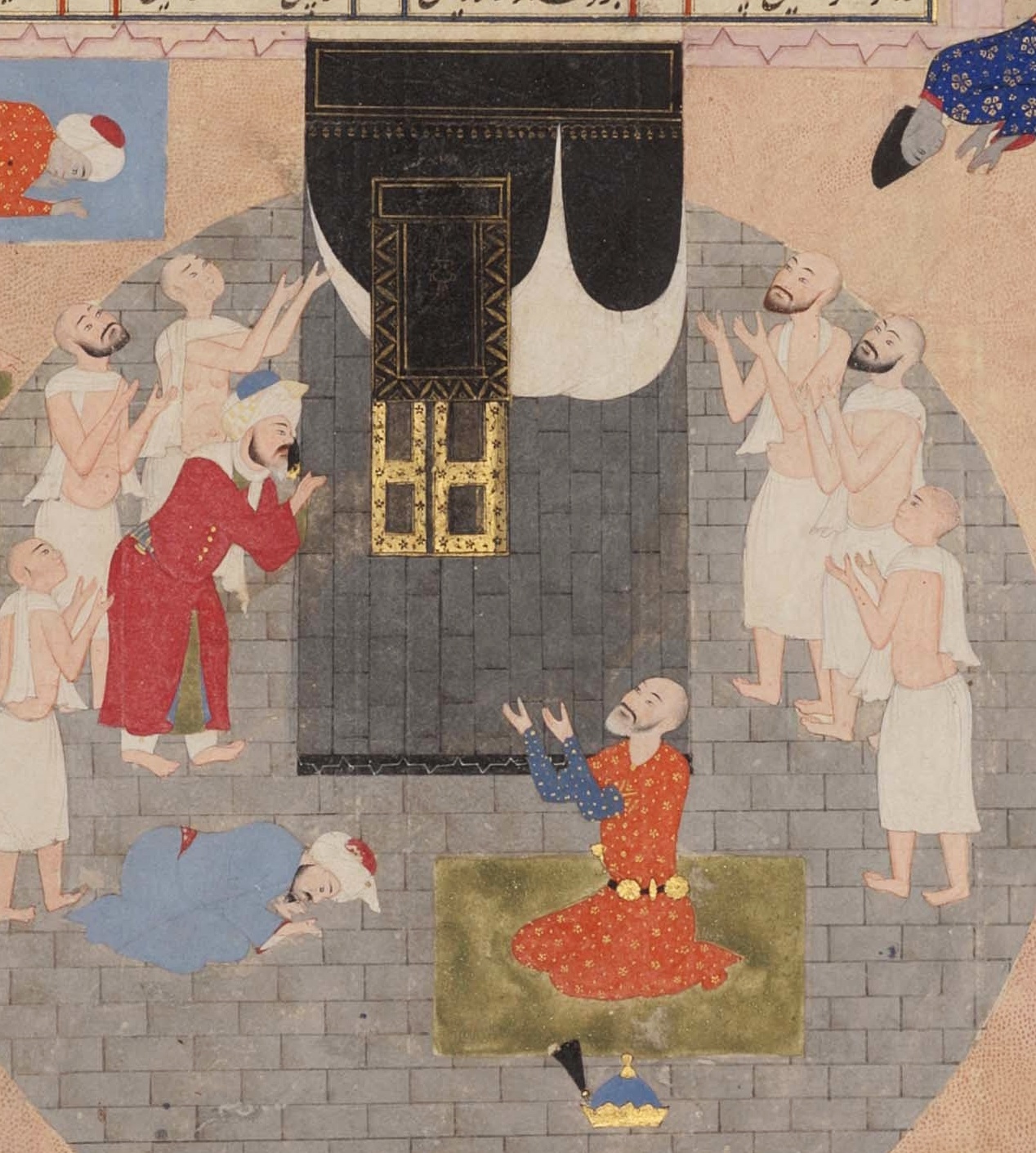

Alexander became legendary as a classical hero in the mould of

Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus () was a hero of the Trojan War who was known as being the greatest of all the Greek warriors. The central character in Homer's ''Iliad'', he was the son of the Nereids, Nereid Thetis and Peleus, ...

, featuring prominently in the historical and mythical traditions of both Greek and non-Greek cultures. His military achievements and unprecedented enduring successes in battle made him the measure against which many later military leaders would compare themselves, and his tactics remain a significant subject of study in

military academies worldwide. Legends of Alexander's exploits coalesced into the third-century ''

Alexander Romance'' which, in the premodern period, went through over one hundred recensions, translations, and derivations and was translated into almost every European vernacular and every language of the Islamic world.

After the

Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

, it was the most popular form of European literature.

Early life

Lineage and childhood

Alexander III was born in

Pella

Pella () is an ancient city located in Central Macedonia, Greece. It served as the capital of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. Currently, it is located 1 km outside the modern town of Pella ...

, the capital of the

Kingdom of Macedon

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchic state or realm ruled by a king or queen.

** A monarchic chiefdom, represented or governed by a king or queen.

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and me ...

, on the sixth day of the

ancient Greek month of

Hekatombaion

The Attic calendar or Athenian calendar is the lunisolar calendar beginning in midsummer with the lunar month of Hekatombaion, in use in ancient Attica, the ancestral territory of the Athenian polis. It is sometimes called the Greek calendar beca ...

, which probably corresponds to 20 July 356 BC (although the exact date is uncertain). He was the son of the king of Macedon,

Philip II, and his fourth wife,

Olympias

Olympias (; c. 375–316 BC) was a Ancient Greeks, Greek princess of the Molossians, the eldest daughter of king Neoptolemus I of Epirus, the sister of Alexander I of Epirus, the fourth wife of Philip of Macedon, Philip II, the king of Macedonia ...

(daughter of

Neoptolemus I, king of

Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

). Although Philip had seven or eight wives, Olympias was his principal wife for some time, likely because she gave birth to Alexander.

Several legends surround Alexander's birth and childhood. According to the

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

biographer

Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, on the eve of the consummation of her marriage to Philip, Olympias dreamed that her womb was struck by a thunderbolt that caused a flame to spread "far and wide" before dying away. Sometime after the wedding, Philip is said to have seen himself, in a dream, securing his wife's womb with a

seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, also called "true seal"

** Fur seal

** Eared seal

* Seal ( ...

engraved with a lion's image.

Plutarch offered a variety of interpretations for these dreams: that Olympias was pregnant before her marriage, indicated by the sealing of her womb; or that Alexander's father was

Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

. Ancient commentators were divided about whether the ambitious Olympias promulgated the story of Alexander's divine parentage, variously claiming that she had told Alexander, or that she dismissed the suggestion as impious.

On the day Alexander was born, Philip was preparing a

siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

on the city of

Potidea

__NOTOC__

Potidaea (; , ''Potidaia'', also Ποτείδαια, ''Poteidaia'') was a colony founded by the Corinthians around 600 BC in the narrowest point of the peninsula of Pallene, the westernmost of three peninsulas at the southern end of C ...

on the peninsula of

Chalcidice

Chalkidiki (; , alternatively Halkidiki), also known as Chalcidice, is a peninsula and regional units of Greece, regional unit of Greece, part of the region of Central Macedonia, in the Geographic regions of Greece, geographic region of Macedon ...

. That same day, Philip received news that his general

Parmenion

Parmenion (also Parmenio; ; 400 – 330 BC), son of Philotas, was a Macedonian general in the service of Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great. A nobleman, Parmenion rose to become Philip's chief military lieutenant and Alexander's ...

had defeated the combined

Illyria

In classical and late antiquity, Illyria (; , ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; , ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyrians.

The Ancient Gree ...

n and

Paeonian

In antiquity, Paeonia or Paionia () was the land and kingdom of the Paeonians (or Paionians; ).

The exact original boundaries of Paeonia, like the early history of its inhabitants, are obscure, but it is known that it roughly corresponds to m ...

armies and that his horses had won at the

Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games (Olympics; ) are the world's preeminent international Olympic sports, sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a Multi-s ...

. It was also said that on this day, the

Temple of Artemis

The Temple of Artemis or Artemision (; ), also known as the Temple of Diana, was a Greek temple dedicated to an ancient, localised form of the goddess Artemis (equated with the Religion in ancient Rome, Roman goddess Diana (mythology), Diana) ...

in

Ephesus

Ephesus (; ; ; may ultimately derive from ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek city on the coast of Ionia, in present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in the 10th century BC on the site of Apasa, the former Arzawan capital ...

, one of the

Seven Wonders of the World

Various lists of the Wonders of the World have been compiled from antiquity to the present day, in order to catalogue the world's most spectacular natural features and human-built structures.

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World is the o ...

, burnt down. This led

Hegesias of Magnesia to say that it had burnt down because

Artemis

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Artemis (; ) is the goddess of the hunting, hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, transitions, nature, vegetation, childbirth, Kourotrophos, care of children, and chastity. In later tim ...

was away, attending the birth of Alexander. Such legends may have emerged when Alexander was king, and possibly at his instigation, to show that he was superhuman and destined for greatness from conception.

In his early years, Alexander was raised by a nurse,

Lanike

Lanike or Lanice pronounced (Lan iss) (Greek: ), also called Hellanike or Alacrinis, daughter of Dropidas, who was son of Critias, was the sister of Cleitus the Black, and the nurse of Alexander the Great. She was born, most likely, shortly after ...

, sister of Alexander's future general

Cleitus the Black

Cleitus the Black (; c. 375 BC – 328 BC) was an officer of the Macedonian army led by Alexander the Great. He saved Alexander's life at the Battle of the Granicus in 334 BC and was killed by him in a drunken quarrel six years later. Cleitus was ...

. Later in his childhood, Alexander was tutored by the strict

Leonidas

Leonidas I (; , ''Leōnídas''; born ; died 11 August 480 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek city-state of Sparta. He was the son of king Anaxandridas II and the 17th king of the Agiad dynasty, a Spartan royal house which claimed descent fro ...

, a relative of his mother, and by

Lysimachus of Acarnania Lysimachus of Acarnania (Greek: Λυσίμαχος, ''Lysimachos'') was one of the tutors of Alexander the Great. Though a man of very slender accomplishments, he ingratiated himself with the royal family by calling himself Phoenix, and Alexander A ...

. Alexander was raised in the manner of noble Macedonian youths, learning to read, play the

lyre

The lyre () (from Greek λύρα and Latin ''lyra)'' is a string instrument, stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the History of lute-family instruments, lute family of instruments. In organology, a ...

, ride, fight, and hunt. When Alexander was ten years old, a trader from

Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

brought Philip a horse, which he offered to sell for thirteen

talents. The horse refused to be mounted, and Philip ordered it away. Alexander, however, detecting the horse's fear of its own shadow, asked to tame the horse, which he eventually managed. Plutarch stated that Philip, overjoyed at this display of courage and ambition, kissed his son tearfully, declaring: "My boy, you must find a kingdom big enough for your ambitions. Macedon is too small for you", and bought the horse for him.

Alexander named it

Bucephalas

Bucephalus (; ; – June 326 BC) or Bucephalas, was the horse of Alexander the Great, and one of the most famous horses of classical antiquity. According to the '' Alexander Romance'' (1.15), the name "Bucephalus" literally means "ox-h ...

, meaning "ox-head". Bucephalas carried Alexander as far as

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. When the animal died (because of old age, according to Plutarch, at age 30), Alexander named a city after him,

Bucephala.

Education

When Alexander was 13, Philip began to search for a

tutor

Tutoring is private academic help, usually provided by an expert teacher; someone with deep knowledge or defined expertise in a particular subject or set of subjects.

A tutor, formally also called an academic tutor, is a person who provides assis ...

, and considered such academics as

Isocrates

Isocrates (; ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education through his teaching and writte ...

and

Speusippus

Speusippus (; ; c. 408 – 339/8 BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek philosopher. Speusippus was Plato's nephew by his sister Potone. After Plato's death, c. 348 BC, Speusippus inherited the Platonic Academy, Academy, near age 60, and remai ...

, the latter offering to resign from his stewardship of the

Academy

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

to take up the post. In the end, Philip chose

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

and provided the Temple of the Nymphs at

Mieza as a classroom. In return for teaching Alexander, Philip agreed to rebuild Aristotle's hometown of

Stageira

Stagira (), Stagirus (), or Stageira ( or ) was an ancient Greek city located near the eastern coast of the peninsula of Chalkidice, which is now part of the Greek province of Central Macedonia. It is chiefly known for being the birthplace of ...

, which Philip had razed, and to repopulate it by buying and freeing the ex-citizens who were slaves, or pardoning those who were in exile.

Mieza was like a boarding school for Alexander and the children of Macedonian nobles, such as

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

,

Hephaistion

Hephaestion ( ''Hēphaistíōn''; c. 356 BC – 324 BC), son of Amyntor, was an ancient Macedonian nobleman of probable "Attic or Ionian extraction" and a general in the army of Alexander the Great. He was "by far the dearest ...

, and

Cassander

Cassander (; ; 355 BC – 297 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 305 BC until 297 BC, and '' de facto'' ruler of southern Greece from 317 BC until his death.

A son of Antipater and a contemporary of Alexander the ...

. Many of these students would become his friends and future generals, and are often known as the "Companions". Aristotle taught Alexander and his companions about medicine, philosophy, morals, religion, logic, and art. Under Aristotle's tutelage, Alexander developed a passion for the works of

Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

, and in particular the ''

Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

''; Aristotle gave him an annotated copy, which Alexander later carried on his campaigns. Alexander was able to quote

Euripides

Euripides () was a Greek tragedy, tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars attributed ninety-five plays to ...

from memory.

In his youth, Alexander was also acquainted with Persian exiles at the Macedonian court, who received the protection of Philip II for several years as they opposed

Artaxerxes III

Ochus ( ), known by his dynastic name Artaxerxes III ( ; ), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 359/58 to 338 BC. He was the son and successor of Artaxerxes II and his mother was Stateira.

Before ascending the throne Artaxerxes was ...

.

Among them were

Artabazos II

Artabazos II (in Greek Ἀρτάβαζος) (fl. 389 – 328 BC) was a Persian general and satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia. He was the son of the Persian satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia Pharnabazus II, and younger kinsman (most probabl ...

and his daughter

Barsine

Barsine (; c. 363–309 BC) was the daughter of a Persian father, Artabazus, satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia, and a Greek Rhodian mother, the sister of mercenaries Mentor of Rhodes and Memnon of Rhodes. Barsine became the wife of her uncl ...

, possible future mistress of Alexander, who resided at the Macedonian court from 352 to 342 BC, as well as

Amminapes, future

satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

of Alexander, and a Persian nobleman named

Sisines

Archelaus (; fl. 1st century BC and 1st century, died 17 AD) was a Roman client prince and the last king of Cappadocia. He was also husband of Pythodorida, Queen regnant of Pontus.

Family and early life

Archelaus was a Cappadocian Greek nobl ...

.

This gave the Macedonian court a good knowledge of Persian issues, and may even have influenced some of the innovations in the management of the Macedonian state.

Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; ; ) is a large 10th-century Byzantine Empire, Byzantine encyclopedia of the History of the Mediterranean region, ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas () or Souidas (). It is an ...

writes that

Anaximenes of Lampsacus

Anaximenes of Lampsacus (; ; 320 BC) was a Greek rhetorician and historian. He was one of the teachers of Alexander the Great and accompanied him on his campaigns.

Family

His father was named Aristocles (). His nephew (son of his sister), was also ...

was one of Alexander's teachers, and that Anaximenes also accompanied Alexander on his campaigns.

Heir of Philip II

Regency and ascent of Macedon

At the age of 16, Alexander's education under Aristotle ended. Philip II had waged war against the

Thracians

The Thracians (; ; ) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Southeast Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area that today is shared betwee ...

to the north, which left Alexander in charge as

regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

and

heir apparent

An heir apparent is a person who is first in the order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person. A person who is first in the current order of succession but could be displaced by the birth of a more e ...

. During Philip's absence, the Thracian tribe of

Maedi

The Maedi (also ''Maidans'', ''Maedans'', or ''Medi''; ) were a Thracian tribe in antiquity. Their land was called Maedica (Μαιδική).

In historic times, they occupied the area between Paionia and Thrace, on the southwestern fringes of ...

revolted against Macedonia. Alexander responded quickly and drove them from their territory. The territory was colonized, and a city, named

Alexandropolis, was founded.

Upon Philip's return, Alexander was dispatched with a small force to subdue the revolts in southern

Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

. Campaigning against the Greek city of

Perinthus

Perinthus or Perinthos () was a great and flourishing town of ancient Thrace, situated on the Propontis. According to John Tzetzes, it bore at an early period the name of Mygdonia (Μυγδονία). It lay west of Selymbria and west of Byzanti ...

, Alexander reportedly saved his father's life. Meanwhile, the city of

Amphissa began to work lands that were sacred to

Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

near

Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

, a sacrilege that gave Philip the opportunity to further intervene in Greek affairs. While Philip was occupied in Thrace, Alexander was ordered to muster an army for a campaign in southern Greece. Concerned that other Greek states might intervene, Alexander made it look as though he was preparing to attack Illyria instead. During this turmoil, the

Illyrians

The Illyrians (, ; ) were a group of Indo-European languages, Indo-European-speaking people who inhabited the western Balkan Peninsula in ancient times. They constituted one of the three main Paleo-Balkan languages, Paleo-Balkan populations, alon ...

invaded Macedonia, only to be repelled by Alexander.

Philip and his army joined his son in 338 BC, and they marched south through

Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; ; Ancient: , Katharevousa: ; ; "hot gates") is a narrow pass and modern town in Lamia (city), Lamia, Phthiotis, Greece. It derives its name from its Mineral spring, hot sulphur springs."Thermopylae" in: S. Hornblower & A. Spaw ...

, taking it after stubborn resistance from its Theban garrison. They went on to occupy the city of

Elatea

Elateia (; ) was an ancient Greek city of Phthiotis, and the most important place in that region after Delphi. It is also a modern-day town that is a former municipality in the southeastern part of Phthiotis. Since the 2011 local government reform ...

, only a few days' march from both

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and

Thebes Thebes or Thebae may refer to one of the following places:

*Thebes, Egypt, capital of Egypt under the 11th, early 12th, 17th and early 18th Dynasties

*Thebes, Greece, a city in Boeotia

*Phthiotic Thebes

Phthiotic Thebes ( or Φθιώτιδες Θ ...

. The Athenians, led by

Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; ; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prowess and provide insight into the politics and cu ...

, voted to seek alliance with Thebes against Macedonia. Both Athens and Philip sent embassies to win Thebes's favour, but Athens won the contest. Philip marched on Amphissa (ostensibly acting on the request of the

Amphictyonic League), capturing the mercenaries sent there by Demosthenes and accepting the city's surrender. Philip then returned to Elatea, sending a final offer of peace to Athens and Thebes, who both rejected it.

As Philip marched south, his opponents blocked him near

Chaeronea

Chaeronea ( English: , ) is a village and a former municipality in Boeotia, Greece, located about 35 kilometers east of Delphi. The settlement was formerly known as (), and renamed to () in 1916. Since the 2011 local government reform it is pa ...

,

Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia (; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Greece (adm ...

. During the ensuing

Battle of Chaeronea, Philip commanded the right wing and Alexander the left, accompanied by a group of Philip's trusted generals. According to the ancient sources, the two sides fought bitterly for some time. Philip deliberately commanded his troops to retreat, counting on the untested Athenian

hoplites

Hoplites ( ) ( ) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the soldi ...

to follow, thus breaking their line. Alexander was the first to break the Theban lines, followed by Philip's generals. Having damaged the enemy's cohesion, Philip ordered his troops to press forward and quickly routed them. With the Athenians lost, the Thebans were surrounded. Left to fight alone, they were defeated.

After the victory at Chaeronea, Philip and Alexander marched unopposed into the

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

, devastating much of Laconia and ejecting the Spartans from various parts of it. At

Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

, Philip established a "Hellenic Alliance" (modelled on the old

anti-Persian alliance of the

Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Polis, Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world ...

), which included most Greek city-states except Sparta. Philip was then named ''

Hegemon

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states, either regional or global.

In Ancient Greece (ca. 8th BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' ...

'' (often translated as "Supreme Commander") of this league (known by modern scholars as the

League of Corinth

The League of Corinth, also referred to as the Hellenic League (, ''koinòn tõn Hellḗnōn''; or simply , ''the Héllēnes''), was a federation of Greek states created by Philip IIDiodorus Siculus, Book 16, 89. «διόπερ ἐν Κορί� ...

), and announced his plans to attack the

Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, it was the larg ...

.

Exile and return

When Philip returned to Pella, he fell in love with and married

Cleopatra Eurydice

Eurydice (Greek: Εὐρυδίκη), born Cleopatra (Greek: Κλεοπάτρα) was a mid-4th century BC Macedonian noblewoman, niece of Attalus, and last of the seven wives of Philip II of Macedon, but the first Macedonian one.

Biography

Cleop ...

in 338 BC, the niece of his general

Attalus

Attalus or Attalos may refer to:

People

*Several members of the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon

**Attalus I, ruled 241 BC–197 BC

**Attalus II Philadelphus, ruled 160 BC–138 BC

**Attalus III, ruled 138 BC–133 BC

*Attalus, father of Ph ...

. The marriage made Alexander's position as heir less secure, since any son of Cleopatra Eurydice would be a fully Macedonian heir, while Alexander was only half-Macedonian. During the

wedding banquet, a drunken Attalus publicly prayed to the gods that the union would produce a legitimate heir.

In 337 BC, Alexander fled Macedon with his mother, dropping her off with her brother, King

Alexander I of Epirus

Alexander I of Epirus (; c. 370 BC – 331 BC), also known as Alexander Molossus (), was a king of Epirus (343/2–331 BC) of the Aeacid dynasty.Ellis, J. R., ''Philip II and Macedonian Imperialism'', Thames and Hudson, 1976, pp. ...

in

Dodona

Dodona (; , Ionic Greek, Ionic and , ) in Epirus in northwestern Greece was the oldest Ancient Greece, Hellenic oracle, possibly dating to the 2nd millennium BCE according to Herodotus. The earliest accounts in Homer describe Dodona as an oracle ...

, capital of the

Molossians

The Molossians () were a group of ancient Greek tribes which inhabited the region of Epirus in classical antiquity. Together with the Chaonians and the Thesprotians, they formed the main tribal groupings of the northwestern Greek group. On t ...

. He continued to Illyria where he sought refuge with one or more Illyrian kings, perhaps with

Glaucias, and was treated as a guest, despite having defeated them in battle a few years before. However, it appears Philip never intended to disown his politically and militarily trained son. Accordingly, Alexander returned to Macedon after six months due to the efforts of a family friend,

Demaratus

Demaratus (Greek: Δημάρατος, ''Demaratos''; Doric: Δαμάρατος, ''Damaratos'') was a king of Sparta from around 515 BC to 491 BC. He was the 15th ruler of the Eurypontid dynasty and the firstborn son of King Ariston. During his ...

, who mediated between the two parties.

In the following year, the Persian

satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

(governor) of

Caria

Caria (; from Greek language, Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; ) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Carians were described by Herodotus as being Anatolian main ...

,

Pixodarus

Pixodarus or Pixodaros (in Lycian script, Lycian 𐊓𐊆𐊜𐊁𐊅𐊀𐊕𐊀 ''Pixedara''; in Greek language, Greek Πιξώδαρoς; ruled 340–334 BC), was a satrap of Caria, nominally the Achaemenid Empire Satrap, who enjoyed the statu ...

, offered his eldest daughter to Alexander's half-brother,

Philip Arrhidaeus

Philip III Arrhidaeus (; BC – 317 BC) was king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 323 until his execution in 317 BC. He was a son of King Philip II of Macedon by Philinna of Larissa, and thus an elder half-brother of Alexander th ...

. Olympias and several of Alexander's friends suggested this showed Philip intended to make Arrhidaeus his heir. Alexander reacted by sending an actor,

Thessalus

In Greek mythology, the name Thessalus is attributed to the following individuals, all of whom were considered possible eponyms of Thessaly.

*Thessalus, son of Haemon (mythology), Haemon,Strabo, 9.5.23 son of Chlorus, son of Pelasgus.

*Thessalus, ...

of Corinth, to tell Pixodarus that he should not offer his daughter's hand to an illegitimate son, but instead to Alexander. When Philip heard of this, he stopped the negotiations and scolded Alexander for wishing to marry the daughter of a Carian, explaining that he wanted a better bride for him. Philip exiled four of Alexander's friends,

Harpalus

Harpalus (Greek: Ἅρπαλος), son of Machatas, was a Macedonian aristocrat and childhood friend of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC. Harpalus was repeatedly entrusted with official duties by Alexander and absconded with large su ...

,

Nearchus

Nearchus or Nearchos (; – 300 BC) was one of the Greeks, Greek officers, a navarch, in the army of Alexander the Great. He is known for his celebrated expeditionary voyage starting from the Indus River, through the Persian Gulf and ending at t ...

,

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

and

Erigyius Erigyius (in Greek Ἐριγυιoς; died 328 BC), a Mytilenaean, son of Larichus, was an officer in Alexander the Great's army. He had been driven into banishment by Philip II, king of Macedon, because of his faithful attachment to Alexander, and ...

, and had the Corinthians bring Thessalus to him in chains.

King of Macedon

Accession

In the 24th day of the

Macedonian month Dios, which probably corresponds to 25 October 336 BC, while at

Aegae attending the wedding of his daughter

Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator (; The name Cleopatra is pronounced , or sometimes in both British and American English, see and respectively. Her name was pronounced in the Greek dialect of Egypt (see Koine Greek phonology). She was ...

to Olympias's brother,

Alexander I of Epirus

Alexander I of Epirus (; c. 370 BC – 331 BC), also known as Alexander Molossus (), was a king of Epirus (343/2–331 BC) of the Aeacid dynasty.Ellis, J. R., ''Philip II and Macedonian Imperialism'', Thames and Hudson, 1976, pp. ...

, Philip was assassinated by the captain of his

bodyguards

A bodyguard (or close protection officer/operative) is a type of security guard, government law enforcement officer, or servicemember who protects an important person or group of people, such as high-ranking public officials, wealthy business ...

,

Pausanias, who, according to

Diodorus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which survive intact, b ...

, was also his lover. As Pausanias tried to escape, he tripped over a vine and was killed by his pursuers, including two of Alexander's companions,

Perdiccas

Perdiccas (, ''Perdikkas''; 355BC – 320BC) was a Macedonian general, successor of Alexander the Great, and the regent of Alexander's empire after his death. When Alexander was dying, he entrusted his signet ring to Perdiccas. Initially ...

and

Leonnatus

Leonnatus (; 356 BC – 322 BC) was a Macedonian officer of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Gre ...

. Alexander was proclaimed king on the spot by the nobles and

army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

at the age of 20.

Consolidation of power

Alexander began his reign by eliminating potential rivals to the throne. He had his cousin, the former

Amyntas IV, executed. He also had two Macedonian princes from the region of

Lyncestis

Lynkestis, Lyncestis, Lyngistis, Lynkos or Lyncus ( or Λύγκος or ''Lyncus'') was a region and principality traditionally located in Upper Macedonia. It was the northernmost mountainous region of Upper Macedonia, located east of the Prespa ...

killed for having been involved in his father's assassination, but spared a third,

Alexander Lyncestes

Alexander () (d. 330 BC), son of Aeropus of Lyncestis, was a native of the upper Macedonian district called Lyncestis, whence he is usually called Alexander of Lynkestis or Alexander Lyncestes. Justin makes the singular mistake of calling him A ...

. Olympias had Cleopatra Eurydice, and Europa, her daughter by Philip, burned alive. When Alexander learned about this, he was furious. Alexander also ordered the murder of Attalus, who was in command of the advance guard of the army in Asia Minor and Cleopatra's uncle.

Attalus was at that time corresponding with Demosthenes, regarding the possibility of defecting to Athens. Attalus also had severely insulted Alexander, and following Cleopatra's murder, Alexander may have considered him too dangerous to be left alive.

Alexander spared Arrhidaeus, who was by all accounts mentally disabled, possibly as a result of poisoning by Olympias.

News of Philip's death roused many states into revolt, including Thebes, Athens, Thessaly, and the Thracian tribes north of Macedon. When news of the revolts reached Alexander, he responded quickly. Though advised to use diplomacy, Alexander mustered 3,000 Macedonian cavalry and rode south towards Thessaly. He found the Thessalian army occupying the pass between

Mount Olympus

Mount Olympus (, , ) is an extensive massif near the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, located on the border between Thessaly and Macedonia (Greece), Macedonia, between the regional units of Larissa (regional unit), Larissa and Pieria (regional ...

and

Mount Ossa, and ordered his men to ride over Mount Ossa. When the Thessalians awoke the next day, they found Alexander in their rear and promptly surrendered, adding their cavalry to Alexander's force. He then continued south towards the

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

.

Alexander stopped at Thermopylae where he was recognized as the leader of the Amphictyonic League before heading south to

Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

. Athens sued for peace and Alexander pardoned the rebels. The famous

encounter between Alexander and Diogenes the Cynic occurred during Alexander's stay in Corinth. When Alexander asked Diogenes what he could do for him, the philosopher disdainfully asked Alexander to stand a little to the side, as he was blocking the sunlight. This reply apparently delighted Alexander who is reported to have said, "But verily, if I were not Alexander, I would like to be Diogenes." At Corinth, Alexander took the title of ''Hegemon'' ("leader") and, like Philip, was appointed commander for the coming war against Persia. He also received news of a Thracian uprising.

Balkan campaign

Before crossing to Asia, Alexander wanted to safeguard his northern borders. In the spring of 335 BC, he advanced to suppress several revolts. Starting from

Amphipolis

Amphipolis (; ) was an important ancient Greek polis (city), and later a Roman city, whose large remains can still be seen. It gave its name to the modern municipality of Amphipoli, in the Serres regional unit of northern Greece.

Amphipol ...

, he travelled east into the country of the "Independent Thracians", and at

Mount Haemus

The Balkan mountain range is located in the eastern part of the Balkan peninsula in Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It is conventionally taken to begin at the peak of Vrashka Chuka on the border between Bulgaria and Serbia. It then runs f ...

, the Macedonian army attacked and defeated the Thracian forces manning the heights.

The Macedonians marched into the country of the

Triballi

The Triballi (, ) were an ancient people who lived in northern Bulgaria in the region of Roman Oescus up to southeastern Serbia, possibly near the territory of the Morava Valley in the late Iron Age. The Triballi lived between Thracians to the ...

and defeated their army near the

Lyginus

The Rositsa ( ) is river in northern Bulgaria, a left tributary of the river Yantra, itself a right tributary of the Danube. With a length of 164 km, it is the largest tributary of the Yantra and the 13th longest river in the country. Its anc ...

river (a

tributary of the Danube). Alexander then marched for three days to the

Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

, encountering the

Getae

The Getae or Getai ( or , also Getans) were a large nation who inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania, throughout much of Classical Antiquity. The main source of informa ...

tribe on the opposite shore. Crossing the river at night, he surprised them and forced their army to retreat after the first cavalry

skirmish

Skirmishers are light infantry or light cavalry soldiers deployed as a vanguard, flank guard or rearguard to Screening (tactical), screen a tactical position or a larger body of friendly troops from enemy advances. They may be deployed in a sk ...

.

News then reached Alexander that the Illyrian chieftain

Cleitus and

King Glaukias

Glaucias (; ruled c. 335 – c. 295 BC) was a ruler of the Taulantian kingdom which dominated southern Illyrian affairs in the second half of the 4th century BC. Glaucias is first mentioned as bringing a considerable force to the assistance o ...

of the

Taulantii

Taulantii or Taulantians ('swallow-men'; Ancient Greek: , or , ; ) were an Illyrians, Illyrian people that lived on the Adriatic coast of southern Illyria (modern Albania). They dominated at various times much of the plain between the rivers Dri ...

were in open revolt against his authority. Marching west into Illyria, Alexander defeated each in turn, forcing the two rulers to flee with their troops. With these victories, he secured his northern frontier.

Destruction of Thebes

While Alexander campaigned north, the Thebans and Athenians rebelled once again. Alexander immediately headed south. While the other cities again hesitated, Thebes decided to fight. The Theban resistance was ineffective and Alexander

razed the city and divided its territory between the other Boeotian cities. The end of Thebes cowed Athens, leaving all of Greece temporarily at peace. Alexander then set out on his Asian campaign, leaving

Antipater

Antipater (; ; 400 BC319 BC) was a Macedonian general, regent and statesman under the successive kingships of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. In the wake of the collapse of the Argead house, his son Cassander ...

as regent.

Conquest of the Achaemenid Persian Empire

Strategy

Alexander's invasion of Persia as a whole has been denoted as a supreme example of a "strategic line" of conducting war, a line formed by "the chain of logic that connects operations into a single whole." In his book ''Strategy'', Soviet military officer and theorist

Alexander Svechin

Alexander Andreyevich Svechin (; 17 August 1878 – 28 July 1938) was a Russian and Soviet military leader, military writer, educator, and theorist, and author of the military classic work ''Strategy''.

Early life

He was born in Odessa, wher ...

delineates Alexander's strategic steps. After securing his Greek base and the Balkans by subjugating his political opponents, and securing his army's rear through the conquest of all the Afro-Asian coastline, where the Persian fleet was based and from which it was supplied, Alexander, moved to confront directly the Persians. He thus resolved the eternal problem of an army conducting operations deep into enemy territory, Svechin states, in an "exemplary manner."

Asia Minor

After his victory at the

Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC)

The Battle of Mount Haemus was fought in 338 BC, near the city of Chaeronea in Boeotia, between Macedonia under Philip II and an alliance of city-states led by Athens and Thebes. The battle was the culmination of Philip's final campaigns ...

,

Philip II began the work of establishing himself as ''hēgemṓn'' () of a league which according to

Diodorus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which survive intact, b ...

was to wage a campaign against the Persians for the sundry grievances Greece suffered in

480

__NOTOC__

Year 480 ( CDLXXX) was a leap year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Basilius without colleague (or, less frequently, year 1233 ''Ab urbe condita''). The denominat ...

and free the Greek cities of the western coast and islands from Achaemenid rule. In 336 he sent

Parmenion

Parmenion (also Parmenio; ; 400 – 330 BC), son of Philotas, was a Macedonian general in the service of Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great. A nobleman, Parmenion rose to become Philip's chief military lieutenant and Alexander's ...

,

Amyntas

Amyntas () is a male given name, a variation of (''amyntes''), derived from the (''amyntor'') and ultimately from the verb . It was particularly widespread in ancient Macedon, and was given to several prominent ancient Macedonian and Hellenist ...

, Andromenes, Attalus, and an army of 10,000 men into

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

to make preparations for an invasion.

The Greek cities on the western coast of Anatolia revolted until the news arrived that Philip had been murdered and had been succeeded by his young son Alexander. The Macedonians were demoralized by Philip's death and were subsequently defeated near

Magnesia by the Achaemenids under the command of the mercenary

Memnon of Rhodes

Memnon of Rhodes (Greek: Μέμνων ὁ Ῥόδιος; 380 – 333 BC) was a prominent Rhodian Greek commander in the service of the Achaemenid Empire. Related to the Persian aristocracy by the marriage of his sister to the satrap Artabaz ...

.

Taking over the invasion project of Philip II, Alexander's army crossed the

Hellespont

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey t ...

in 334 BC with approximately 48,100 soldiers, 6,100 cavalry, and a fleet of 120 ships with crews numbering 38,000 drawn from Macedon and various Greek city states, mercenaries, and feudally raised soldiers from

Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

,

Paionia

In antiquity, Paeonia or Paionia () was the land and kingdom of the Paeonians (or Paionians; ).

The exact original boundaries of Paeonia, like the early history of its inhabitants, are obscure, but it is known that it roughly corresponds to m ...

, and

Illyria

In classical and late antiquity, Illyria (; , ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; , ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyrians.

The Ancient Gree ...

. He showed his intent to conquer the entirety of the Persian Empire by throwing a spear into Asian soil and saying he accepted Asia as a gift from the gods. This also showed Alexander's eagerness to fight, in contrast to his father's preference for diplomacy.

After an initial victory against Persian forces at the

Battle of the Granicus

The Battle of the Granicus in May 334 BC was the first of three major battles fought between Alexander the Great of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon and the Persian Achaemenid Empire. The battle took place on the road from Abydos (Hellespont ...

, Alexander accepted the surrender of the Persian provincial capital and treasury of

Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

; he then proceeded along the

Ionia

Ionia ( ) was an ancient region encompassing the central part of the western coast of Anatolia. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionians who ...

n coast, granting autonomy and democracy to the cities.

Miletus

Miletus (Ancient Greek: Μίλητος, Mílētos) was an influential ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in present day Turkey. Renowned in antiquity for its wealth, maritime power, and ex ...

, held by Achaemenid forces, required a delicate siege operation, with Persian naval forces nearby. Further south, at

Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus ( ; Latin: ''Halicarnassus'' or ''Halicarnāsus''; ''Halikarnāssós''; ; Carian language, Carian: 𐊠𐊣𐊫𐊰 𐊴𐊠𐊥𐊵𐊫𐊰 ''alos k̂arnos'') was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek city in Caria, in Anatolia. , in

Caria

Caria (; from Greek language, Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; ) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Carians were described by Herodotus as being Anatolian main ...

, Alexander successfully waged his first large-scale

siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

, eventually forcing his opponents, the mercenary captain

Memnon of Rhodes

Memnon of Rhodes (Greek: Μέμνων ὁ Ῥόδιος; 380 – 333 BC) was a prominent Rhodian Greek commander in the service of the Achaemenid Empire. Related to the Persian aristocracy by the marriage of his sister to the satrap Artabaz ...

and the Persian

satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

of Caria,

Orontobates

Orontobates (Old Persian: , Ancient Greek: ; lived 4th century BC) was a Persian, who married the daughter of Pixodarus, the usurping satrap of Caria, and was sent by the king of Persia to succeed him.

Biography

On the approach of Alexander th ...

, to withdraw by sea. Alexander left the government of Caria to a member of the Hecatomnid dynasty,

Ada

Ada may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle'', a novel by Vladimir Nabokov

Film and television

* Ada, a character in 1991 movie '' Armour of God II: Operation Condor''

* '' Ada... A Way of Life'', a 2008 Bollywo ...

, who adopted Alexander.

From Halicarnassus, Alexander proceeded into mountainous

Lycia

Lycia (; Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; , ; ) was a historical region in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is today the provinces of Antalya and Muğ ...

and the

Pamphylia

Pamphylia (; , ''Pamphylía'' ) was a region in the south of Anatolia, Asia Minor, between Lycia and Cilicia, extending from the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean to Mount Taurus (all in modern-day Antalya province, Turkey). It was bounded on the ...

n plain, asserting control over all coastal cities to deny the Persians naval bases. From Pamphylia onwards, the coast held no major ports and Alexander moved inland. At

Termessos

Termessos (Greek Τερμησσός ''Termēssós''), also known as Termessos Major (Τερμησσός ἡ μείζων), was a Pisidian city built at an altitude of about 1000 metres at the south-west side of Solymos Mountain (modern Gül ...

, Alexander humbled and did not storm the

Pisidia

Pisidia (; , ; ) was a region of ancient Asia Minor located north of Pamphylia, northeast of Lycia, west of Isauria and Cilicia, and south of Phrygia, corresponding roughly to the modern-day province of Antalya in Turkey. Among Pisidia's set ...

n city. At the ancient Phrygian capital of

Gordium

Gordion ( Phrygian: ; ; or ; ) was the capital city of ancient Phrygia. It was located at the site of modern Yassıhüyük, about southwest of Ankara (capital of Turkey), in the immediate vicinity of Polatlı district. Gordion's location at ...

, Alexander "undid" the hitherto unsolvable

Gordian Knot

The cutting of the Gordian Knot is an Ancient Greek legend associated with Alexander the Great in Gordium in Phrygia, regarding a complex knot that tied an oxcart. Reputedly, whoever could untie it would be destined to rule all of Asia. In 33 ...

, a feat said to await the future "king of

Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

". According to the story, Alexander proclaimed that it did not matter how the knot was undone, and hacked it apart with his sword.

The Levant and Syria

In spring 333 BC, Alexander crossed the

Taurus

Taurus is Latin for 'bull' and may refer to:

* Taurus (astrology), the astrological sign

** Vṛṣabha, in vedic astrology

* Taurus (constellation), one of the constellations of the zodiac

* Taurus (mythology), one of two Greek mythological ch ...

into

Cilicia

Cilicia () is a geographical region in southern Anatolia, extending inland from the northeastern coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. Cilicia has a population ranging over six million, concentrated mostly at the Cilician plain (). The region inclu ...

. After a long pause due to an illness, he marched on towards Syria. Though outmanoeuvered by Darius's significantly larger army, he marched back to Cilicia, where he defeated Darius at

Issus. Darius fled the battle, causing his army to collapse, and left behind his wife, his two daughters, his mother

Sisygambis

Sisygambis (; died 323 BCE) was the mother of Darius III of Persia, whose reign was ended during the wars of Alexander the Great. After she was captured by Alexander at the Battle of Issus, she became devoted to him, and Alexander referred to he ...

, and a fabulous treasure. He offered a

peace treaty

A peace treaty is an treaty, agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually country, countries or governments, which formally ends a declaration of war, state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an ag ...

that included the lands he had already lost, and a ransom of 10,000

talents for his family. Alexander replied that since he was now king of Asia, it was he alone who decided territorial divisions. Alexander proceeded to take possession of

Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, and most of the coast of the

Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

.

In the following year, 332 BC, he was forced to attack

Tyre, which he captured after a long and difficult

siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

. The men of military age were massacred and the women and children sold into

slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

.

Egypt

When Alexander destroyed Tyre, most of the towns on the route to

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

quickly capitulated. However, Alexander was met with resistance at

Gaza

Gaza may refer to:

Places Palestine

* Gaza Strip, a Palestinian territory on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea

** Gaza City, a city in the Gaza Strip

** Gaza Governorate, a governorate in the Gaza Strip

Mandatory Palestine

* Gaza Sub ...

. The stronghold was heavily fortified and built on a hill, requiring a siege. When "his engineers pointed out to him that because of the height of the mound it would be impossible... this encouraged Alexander all the more to make the attempt". After three unsuccessful assaults, the stronghold fell, but not before Alexander had received a serious shoulder wound. As in Tyre, men of military age were put to the sword, and the women and children were sold into slavery.

Egypt was only one of a large number of territories taken by Alexander from the Persians. After his trip to Siwa, Alexander was crowned in the temple of Ptah at Memphis. It appears that the Egyptian people did not find it disturbing that he was a foreigner – nor that he was absent for virtually his entire reign.

Alexander restored the temples neglected by the Persians and dedicated new monuments to the Egyptian gods. In the temple of Luxor, near Karnak, he built a chapel for the sacred barge. During his brief months in Egypt, he reformed the taxation system on the Greek models and organized the military occupation of the country, but in early 331 BC he left for Asia in pursuit of the Persians.

Alexander advanced on Egypt in later 332 BC where he was regarded as a liberator. To legitimize taking power and be recognized as the descendant of the long line of pharaohs, Alexander made sacrifices to the gods at Memphis and went to consult the famous oracle of Amun-Ra at the

Siwa Oasis

The Siwa Oasis ( ) is an urban oasis in Egypt. It is situated between the Qattara Depression and the Great Sand Sea in the Western Desert (Egypt), Western Desert, east of the Egypt–Libya border and from the Egyptian capital city of Cairo. I ...

in the

Libyan

Demographics of Libya is the demography of Libya, specifically covering population density, ethnicity, and religious affiliations, as well as other aspects of the Libyan population. All figures are from the United Nations Demographic Yearbooks ...

desert,

at which he was pronounced the son of the deity

Amun

Amun was a major ancient Egyptian deity who appears as a member of the Hermopolitan Ogdoad. Amun was attested from the Old Kingdom together with his wife Amunet. His oracle in Siwa Oasis, located in Western Egypt near the Libyan Desert, r ...

. Henceforth, Alexander often referred to

Zeus-Ammon as his true father, and after his death,

currency depicted him adorned with horns, using the

Horns of Ammon

The horns of Ammon were curling ram horns, used as a symbol of the Egyptian deity Ammon (also spelled Amun or Amon). Because of the visual similarity, they were also associated with the fossils shells of ancient snails and cephalopods, the latter ...

as a symbol of his divinity. The Greeks interpreted this message – one that the gods addressed to all pharaohs – as a prophecy.

During his stay in Egypt, he founded

Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, which would become the prosperous capital of the

Ptolemaic Kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (; , ) or Ptolemaic Empire was an ancient Greek polity based in Ancient Egypt, Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian Greek general Ptolemy I Soter, a Diadochi, ...

after his death. Control of Egypt passed to Ptolemy I (son of Lagos), the founder of the Ptolemaic Dynasty (305–30 BC) after the death of Alexander.

Assyria and Babylonia

Leaving Egypt in 331 BC, Alexander marched eastward into

Achaemenid Assyria

Athura ( ''Aθurā'' ), also called Assyria, was a geographical area within the Achaemenid Empire in Upper Mesopotamia from 539 to 330 BC as a military protectorate state. Although sometimes regarded as a satrapy, Achaemenid royal inscriptions ...

in

Upper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia constitutes the Upland and lowland, uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, the regio ...

(now northern

Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

) and defeated Darius again at the

Battle of Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela ( ; ), also called the Battle of Arbela (), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Ancient Macedonian army, Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great and the Achaemenid Army, Persian Army under Darius III, ...

. Darius once more fled the field, and Alexander chased him as far as

Arbela

Arbela may refer to:

Places

* Greco-Roman name of the city of Erbil, Kurdistan Region, Iraq

* Arbel, Israel

* Irbid, Jordan

* Arbela, Ohio, United States

* Arbela Township, Michigan, United States

* Arbela, Missouri, United States

Other uses

...

. Gaugamela would be the final and decisive encounter between the two. Darius fled over the mountains to

Ecbatana