|

Paleo-Arabic

Paleo-Arabic (or Palaeo-Arabic, previously called pre-Islamic Arabic or Old Arabic) is a pre-Islamic Arabian script used to write Arabic. It began to be used in the fifth century, when it succeeded the earlier Nabataeo-Arabic script, and it was used until the early seventh century, when the Arabic script was standardized in the Islamic era. Evidence for the use of Paleo-Arabic was once confined to Syria and Jordan. In more recent years, Paleo-Arabic inscriptions have been discovered across the Arabian Peninsula including: South Arabia (the Christian Hima texts), near Taif in the Hejaz and in the Tabuk region of northwestern Saudi Arabia. Most Paleo-Arabic inscriptions were written by Christians, as indicated by their vocabulary, the name of the signing author, or by the inscription/drawing of a cross associated with the writing. The term "Paleo-Arabic" was first used by Christian Robin in the form of the French expression "paléo-arabe". Classification Paleo-Arabic ref ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Hima Paleo-Arabic Inscriptions

The Ḥimà Paleo-Arabic inscriptions are a group of twenty-five inscriptions discovered at Hima, 90 km north of Najran, in southern Saudi Arabia, written in the Paleo-Arabic script. These are among the broader group of inscriptions discovered in this region and were discovered during the Saudi-French epigraphic mission named the ''Mission archéologique franco-saoudienne de Najran''. They were the first Paleo-Arabic inscriptions discovered in Saudi Arabia, before which examples had only been known from Syria. The inscriptions have substantially expanded the understanding of the evolution of the Arabic script. Date While the majority of the Hima inscriptions do not carry an absolute date, some of them date either to 470 or 513 AD, which makes the former (Ḥimà- Sud Pal Ar 1) the earliest precisely dated Paleo-Arabic inscription. Interpretation and significance Several of the Hima inscriptions are explicitly Christian, and the inscriptions appear to be the product of the ac ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

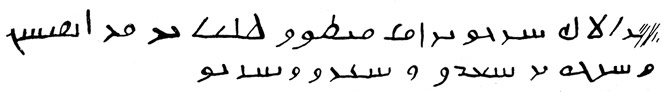

Zabad Inscription

The Zabad inscription (or trilingual Zabad inscription, Zebed inscription) is a trilingual Christian inscription containing text in the Greek, Syriac, and Paleo-Arabic scripts. Composed in the village of Zabad in northern Syria in 512, the inscription dedicates the construction of the martyrium, named the Church of St. Sergius, to Saint Sergius. The inscription itself is positioned at the lintel of the entrance portal. The Zabad inscription records the benefaction carried out by Arabic-speaking Christians in the Roman Empire. Despite the inscription being called a "trilingual", the Greek, Syriac, and Arabic components are not merely translations of one another but instead reflect the varying interests by different linguistic communities involved in the composition of the inscription. Only the Greek portion of the inscription explicitly mentions the martyrium and the saint. The individuals mentioned in the inscription are not otherwise known, but were the ones who played a rol ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ahmad Al-Jallad

Ahmad Al-Jallad is a Jordanian-American philologist, epigraphist, and a historian of language. Some of the areas he has contributed to include Quranic studies and the history of Arabic, including recent work he has done on pre-Islamic Arabian inscriptions written in Safaitic and Paleo-Arabic. He is currently Professor in the Sofia Chair in Arabic Studies at Ohio State University at the Department of Near Eastern and South Asian Languages and Cultures. He is the winner of the 2017 Dutch Gratama Science Prize. Biography Al-Jallad was born in Salt Lake City. As an undergraduate, he attended the University of South Florida. He entered Harvard University for his doctoral program in Semitic philology and received his Ph.D. in 2012. One of his mentors during his studies was Michael C. A. Macdonald from the University of Oxford and John Huehnergard from Harvard University. One of his earliest achievements was reconstructing a previously unknown Arabian zodiac from pre-Islamic Arabia. He i ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Abd Shams Inscription

The Umm Burayrah inscription (also known as the Abd Shams inscription) is a Paleo-Arabic inscription discovered in the Tabuk Province of northwestern Saudi Arabia. Among Paleo-Arabic inscriptions it contains a unique invocation formula, a prayer for forgiveness, and the personal name ʿAbd Shams (ʿAbd Šams). It was originally photographed and published by Muhammed Abdul Nayeem in 2000, and was recently redocumented by the amateur archaeologist Saleh al‐Hwaiti. Though no date is found on the inscription, one proposal places it in the late sixth or early seventh century. Text The following transliteration and translation comes from the 2023 edition of the inscription. The text can be divided into three parts: the opening formula, the personal pronoun "I" (''anā'') plus the personal name, and the closing formula.Vocalized transliteration bi‐smika Allāhumma anā ʿAbd Šams br al‐Muġīrah, yastaġfir Rabbahu Translation In your name, God, I, ʿAbd Šams, son of al‐Muġ ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Jebel Usays Inscription

The Jebel Usays inscription (or Jabal Usays, Jabal Says) is a small rock graffito dating to 528 AD, located at the site of Jabal Says, an ancient volcano in the basaltic steppe lands of southern Syria. It is written in the Paleo-Arabic script. Only two other inscriptions written in the Paleo-Arabic scripts are known from Syria: the Zabad inscription, dating to 512, and the Harran inscription dating to 567–568. All three are connected to the Jafnids. Text The following transcription and translation of the inscription comes from the 2015 edition of the inscription.Transliteration 1. ʾnh rqym br mʿrf ʾl-ʾwsy 2. ʾrsl-ny ʾl-h ˙ rṯʾl-mlk ʿly 3. ʾsys mslh ˙ h snt 4. 4. 4x100+20+1+1+1 Translation 1. I Ruqaym son of Maʿarrif the Awsite 2. Al-Hāriṯ the king sent me to 3. Usays, as a frontier guard, nthe year 4. 423 ad 528/9 Date The inscription states the year it was written, and that year has been read in two ways by experts. In one reading, it is read ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Pre-Islamic Arabian Inscriptions

Pre-Islamic Arabian inscriptions are Epigraphy, inscriptions that come from the Arabian Peninsula dating to Pre-Islamic Arabia, before the rise of Islam. They were written in both Arabic and other languages, including Sabaic, Hadramautic language, Hadramautic, Minaic, Qatabanian language, Qatabanic. These inscriptions come in two forms: graffiti, "self-authored personal expressions written in a public space", and monumental inscriptions, commissioned to a professional scribe by an elite for an official role. Unlike modern graffiti, the graffiti in these inscriptions are usually signed (and so not anonymous) and were not illicit or subversive. Graffiti are usually just scratchings on the surface of rock, but both graffiti and monumental inscriptions could be produced by painting, or the use of a chisel, charcoal, brush, or other tools. These inscriptions are typically non-portable (being lapidary) and were engraved (and not painted). Both graffiti and monumental inscriptions were als ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Monotheism In Pre-Islamic Arabia

Monotheism, the belief in a supreme Creator being, existed in pre-Islamic Arabia. This practice occurred among pre-Islamic Christian, Jewish, and other populations unaffiliated with either one of the two major Abrahamic religions at the time. Monotheism became a religious trend in pre-Islamic Arabia in the fourth century CE, when it began to supplant the polytheism that had been the common form of religion until then. Transition from polytheism to monotheism in this time is documented from inscriptions in all writing systems on the Arabian Peninsula (including those in Nabataean, Safaitic, and Sabaic), where polytheistic gods and idols cease to be mentioned. Epigraphic evidence is nearly exclusively monotheistic in the fifth century, and from the sixth century and until the eve of Islam, it is solely monotheistic. Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry is also monotheistic or henotheistic. An important locus of pre-Islamic Arabian monotheism, the Himyarite Kingdom, ruled over South Arabia, w ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ri Al-Zallalah Inscription

The Rīʿ al-Zallālah inscription is a pre-Islamic Paleo-Arabic inscription, likely dating to the 6th century, located near Taif, in a narrow pass that connects this city to the al-Sayl al- Kabīr wadi. History The rock art the inscription is located on was first described by James Hamilton in 1845, although he did not include the inscriptions he saw in his publication. The inscription itself was only noticed with during the 1951–1952 Philby-Ryckmans-Lippens expedition by Adolf Grofmann, and, though he supplied a reading of the inscription, a copy was still not made. The Ṭāʾif- Mecca epigraphic survey led by Ahmad Al-Jallad and Hythem Sidky returned to the site in August 2021 and produced new photographs of the inscription, which was finally published with a new edition in 2022. Content The inscription reads:Transcription: ''brk- rb-nʾ'' ''ʾnʾ .rh'' ''br sd'' Arabic: ىركم رىىا اىا .ره ىر سد English: may our Lord bless you I am rh son o ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Trilingual Inscription At Zebed - Arabic Text - After Combe 1931

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world's population. More than half of all Europeans claim to speak at least one language other than their mother tongue; but many read and write in one language. Multilingualism is advantageous for people wanting to participate in trade, globalization and cultural openness. Owing to the ease of access to information facilitated by the Internet, individuals' exposure to multiple languages has become increasingly possible. People who speak several languages are also called polyglots. Multilingual speakers have acquired and maintained at least one language during childhood, the so-called first language (L1). The first language (sometimes also referred to as the mother tongue) is usually acquired without formal education, by mechanisms about which scholars disagree. Children acquiring ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Dalet

Dalet (, also spelled Daleth or Daled) is the fourth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician Dālet 𐤃, Hebrew Dālet , Aramaic Dālath , Syriac Dālaṯ , and Arabic (in abjadi order; 8th in modern order). Its sound value is the voiced alveolar plosive (). The letter is based on a glyph of the Proto-Sinaitic script, probably called ''dalt'' "door" (''door'' in Modern Hebrew is delet), ultimately based on a hieroglyph depicting a door: O31 Phoenician The Phoenician dālet gave rise to the Greek delta (Δ), Latin D, and the Cyrillic letter Д. Aramaic Hebrew Hebrew spelling: The letter is ''dalet'' in the modern Israeli Hebrew pronunciation (see Taw (letter), Tav (letter). ''Dales'' is still used by many Ashkenazi Jews and ''daleth'' by some Jews of Middle East, Middle-Eastern background, especially in the Jewish diaspora. In some academic circles, it is called ''daleth'', following the Tiberian Hebrew pronunciation. It is also called ''dale ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

ʾalif

Aleph (or alef or alif, transliterated ʾ) is the first letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician , Hebrew , Aramaic , Syriac , Arabic ʾ and North Arabian 𐪑. It also appears as South Arabian 𐩱 and Ge'ez . These letters are believed to have derived from an Egyptian hieroglyph depicting an ox's head to describe the initial sound of ''*ʾalp'', the West Semitic word for ox (compare Biblical Hebrew ''ʾelef'', "ox"). The Phoenician variant gave rise to the Greek alpha (), being re-interpreted to express not the glottal consonant but the accompanying vowel, and hence the Latin A and Cyrillic А. Phonetically, ''aleph'' originally represented the onset of a vowel at the glottis. In Semitic languages, this functions as a prosthetic weak consonant, allowing roots with only two true consonants to be conjugated in the manner of a standard three consonant Semitic root. In most Hebrew dialects as well as Syriac, the ''aleph'' is an absence of a true ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Arabic Diacritics

The Arabic script has numerous diacritics, which include: consonant pointing known as (), and supplementary diacritics known as (). The latter include the vowel marks termed (; singular: , '). The Arabic script is a modified abjad, where short consonants and long vowels are represented by letters but short vowels and consonant length are not generally indicated in writing. ' is optional to represent missing vowels and consonant length. Modern Arabic is always written with the ''i‘jām''—consonant pointing, but only religious texts, children's books and works for learners are written with the full ''tashkīl''—vowel guides and consonant length. It is however not uncommon for authors to add diacritics to a word or letter when the grammatical case or the meaning is deemed otherwise ambiguous. In addition, classical works and historic documents rendered to the general public are often rendered with the full ''tashkīl'', to compensate for the gap in understanding resultin ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |