uranium on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Uranium is a

Uranium is a silvery white, weakly radioactive

Uranium is a silvery white, weakly radioactive

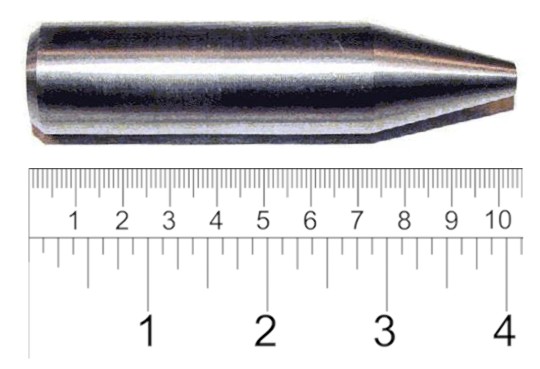

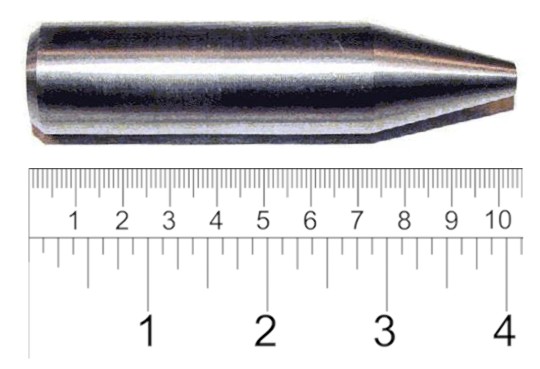

The major application of uranium in the military sector is in high-density penetrating projectiles. This ammunition consists of depleted uranium (DU) alloyed with 1–2% other elements, such as titanium or

The major application of uranium in the military sector is in high-density penetrating projectiles. This ammunition consists of depleted uranium (DU) alloyed with 1–2% other elements, such as titanium or

Before (and, occasionally, after) the discovery of radioactivity, uranium was primarily used in small amounts for yellow glass and pottery glazes, such as uranium glass and in Fiestaware.

The discovery and isolation of radium in uranium ore (pitchblende) by Marie Curie sparked the development of uranium mining to extract the radium, which was used to make glow-in-the-dark paints for clock and aircraft dials. This left a prodigious quantity of uranium as a waste product, since it takes three tonnes of uranium to extract one gram of radium. This waste product was diverted to the glazing industry, making uranium glazes very inexpensive and abundant. Besides the pottery glazes, uranium tile glazes accounted for the bulk of the use, including common bathroom and kitchen tiles which can be produced in green, yellow, mauve, black, blue, red and other colors.

Uranium was also used in photographic chemicals (especially uranium nitrate as a toner), in lamp filaments for stage lighting bulbs, to improve the appearance of dentures, and in the leather and wood industries for stains and dyes. Uranium salts are mordants of silk or wool. Uranyl acetate and uranyl formate are used as electron-dense "stains" in

Before (and, occasionally, after) the discovery of radioactivity, uranium was primarily used in small amounts for yellow glass and pottery glazes, such as uranium glass and in Fiestaware.

The discovery and isolation of radium in uranium ore (pitchblende) by Marie Curie sparked the development of uranium mining to extract the radium, which was used to make glow-in-the-dark paints for clock and aircraft dials. This left a prodigious quantity of uranium as a waste product, since it takes three tonnes of uranium to extract one gram of radium. This waste product was diverted to the glazing industry, making uranium glazes very inexpensive and abundant. Besides the pottery glazes, uranium tile glazes accounted for the bulk of the use, including common bathroom and kitchen tiles which can be produced in green, yellow, mauve, black, blue, red and other colors.

Uranium was also used in photographic chemicals (especially uranium nitrate as a toner), in lamp filaments for stage lighting bulbs, to improve the appearance of dentures, and in the leather and wood industries for stains and dyes. Uranium salts are mordants of silk or wool. Uranyl acetate and uranyl formate are used as electron-dense "stains" in

The

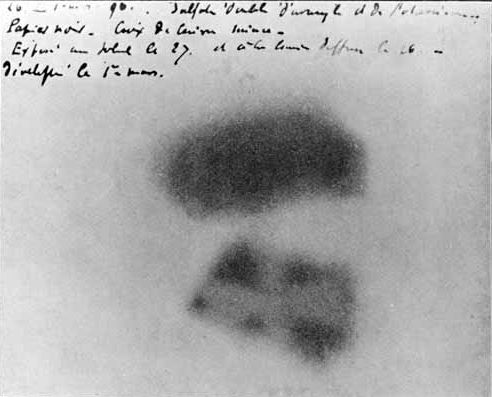

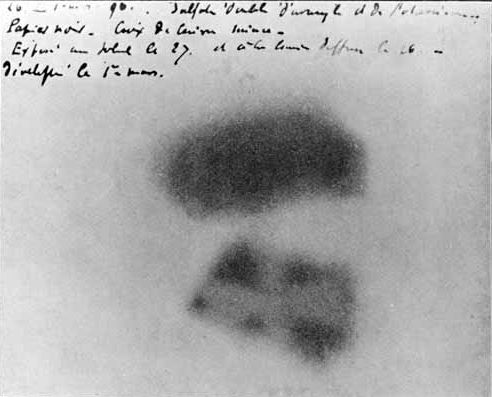

The  Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity by using uranium in 1896. Becquerel made the discovery in Paris by leaving a sample of a uranium salt, KUO(SO) (potassium uranyl sulfate), on top of an unexposed photographic plate in a drawer and noting that the plate had become "fogged". He determined that a form of invisible light or rays emitted by uranium had exposed the plate.

During World War I when the

Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity by using uranium in 1896. Becquerel made the discovery in Paris by leaving a sample of a uranium salt, KUO(SO) (potassium uranyl sulfate), on top of an unexposed photographic plate in a drawer and noting that the plate had become "fogged". He determined that a form of invisible light or rays emitted by uranium had exposed the plate.

During World War I when the

A team led by Enrico Fermi in 1934 found that bombarding uranium with neutrons produces beta rays (

A team led by Enrico Fermi in 1934 found that bombarding uranium with neutrons produces beta rays (

Two types of atomic bomb were developed by the United States during

Two types of atomic bomb were developed by the United States during

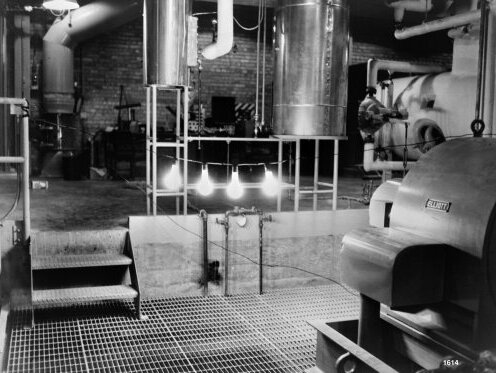

The X-10 Graphite Reactor at

The X-10 Graphite Reactor at

Above-ground nuclear tests by the Soviet Union and the United States in the 1950s and early 1960s and by

Above-ground nuclear tests by the Soviet Union and the United States in the 1950s and early 1960s and by

Some bacteria, such as '' Shewanella putrefaciens'', '' Geobacter metallireducens'' and some strains of '' Burkholderia fungorum'', can use uranium for their growth and convert U(VI) to U(IV). Recent research suggests that this pathway includes reduction of the soluble U(VI) via an intermediate U(V) pentavalent state.

Other organisms, such as the

Some bacteria, such as '' Shewanella putrefaciens'', '' Geobacter metallireducens'' and some strains of '' Burkholderia fungorum'', can use uranium for their growth and convert U(VI) to U(IV). Recent research suggests that this pathway includes reduction of the soluble U(VI) via an intermediate U(V) pentavalent state.

Other organisms, such as the

U production-demand.png, World uranium production (mines) and demand

Yellowcake.jpg, alt=A yellow sand-like rhombic mass on black background., Yellowcake is a concentrated mixture of uranium oxides that is further refined to extract pure uranium.

Uranium production, OWID.svg, Uranium production 2015, in tonnes

It is estimated that 6.1 million tonnes of uranium exists in ores that are economically viable at US$130 per kg of uranium, while 35 million tonnes are classed as mineral resources (reasonable prospects for eventual economic extraction).

Australia has 28% of the world's known uranium ore reserves and the world's largest single uranium deposit is located at the Olympic Dam Mine in

It is estimated that 6.1 million tonnes of uranium exists in ores that are economically viable at US$130 per kg of uranium, while 35 million tonnes are classed as mineral resources (reasonable prospects for eventual economic extraction).

Australia has 28% of the world's known uranium ore reserves and the world's largest single uranium deposit is located at the Olympic Dam Mine in

In 2005, ten countries accounted for the majority of the world's concentrated uranium oxides:

In 2005, ten countries accounted for the majority of the world's concentrated uranium oxides:

Salts of many oxidation states of uranium are water- soluble and may be studied in aqueous solutions. The most common ionic forms are (brown-red), (green), (unstable), and (yellow), for U(III), U(IV), U(V), and U(VI), respectively. A few

Salts of many oxidation states of uranium are water- soluble and may be studied in aqueous solutions. The most common ionic forms are (brown-red), (green), (unstable), and (yellow), for U(III), U(IV), U(V), and U(VI), respectively. A few

All uranium fluorides are created using uranium tetrafluoride (); itself is prepared by hydrofluorination of uranium dioxide. Reduction of with hydrogen at 1000 °C produces uranium trifluoride (). Under the right conditions of temperature and pressure, the reaction of solid with gaseous uranium hexafluoride () can form the intermediate fluorides of , , and .

At room temperatures, has a high vapor pressure, making it useful in the gaseous diffusion process to separate the rare uranium-235 from the common uranium-238 isotope. This compound can be prepared from uranium dioxide and uranium hydride by the following process:

: + 4 HF → + 2 (500 °C, endothermic)

: + → (350 °C, endothermic)

The resulting , a white solid, is highly reactive (by fluorination), easily sublimes (emitting a vapor that behaves as a nearly

All uranium fluorides are created using uranium tetrafluoride (); itself is prepared by hydrofluorination of uranium dioxide. Reduction of with hydrogen at 1000 °C produces uranium trifluoride (). Under the right conditions of temperature and pressure, the reaction of solid with gaseous uranium hexafluoride () can form the intermediate fluorides of , , and .

At room temperatures, has a high vapor pressure, making it useful in the gaseous diffusion process to separate the rare uranium-235 from the common uranium-238 isotope. This compound can be prepared from uranium dioxide and uranium hydride by the following process:

: + 4 HF → + 2 (500 °C, endothermic)

: + → (350 °C, endothermic)

The resulting , a white solid, is highly reactive (by fluorination), easily sublimes (emitting a vapor that behaves as a nearly

In nature, uranium is found as uranium-238 (99.2742%) and uranium-235 (0.7204%). Isotope separation concentrates (enriches) the fissile uranium-235 for nuclear weapons and most nuclear power plants, except for gas cooled reactors and pressurized heavy water reactors. Most neutrons released by a fissioning atom of uranium-235 must impact other uranium-235 atoms to sustain the nuclear chain reaction. The concentration and amount of uranium-235 needed to achieve this is called a ' critical mass'.

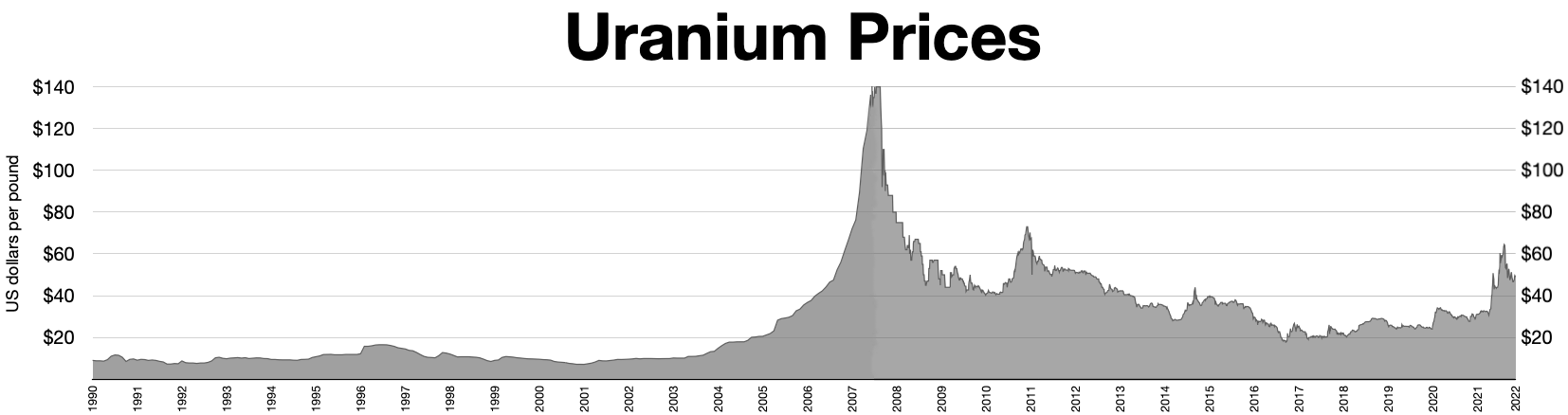

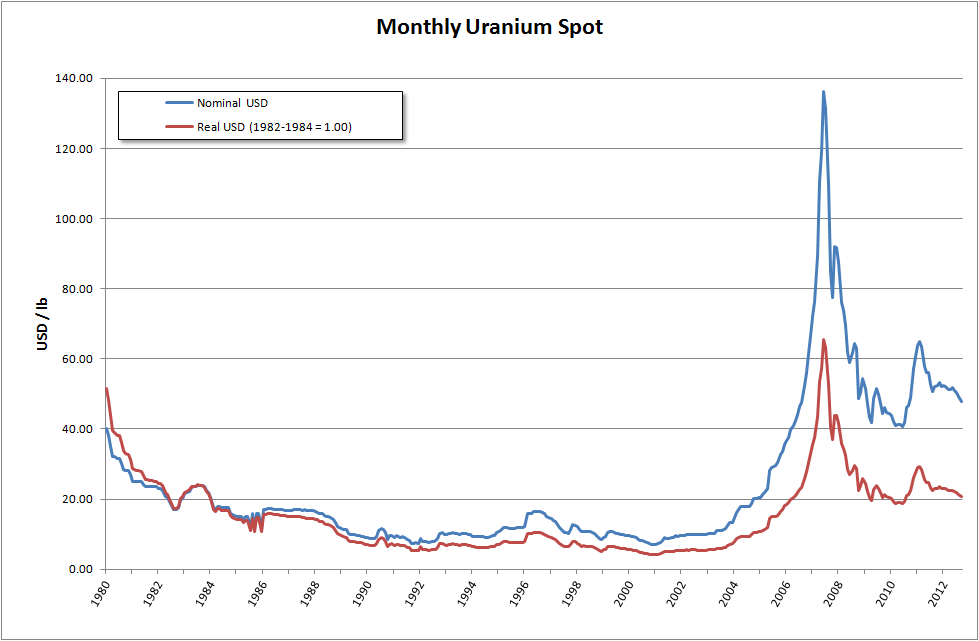

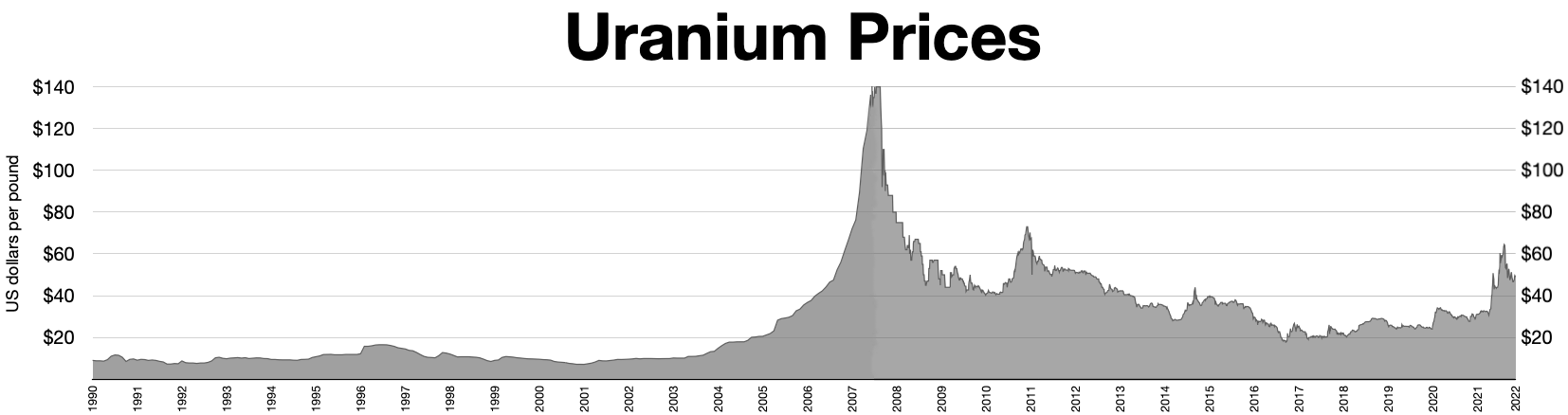

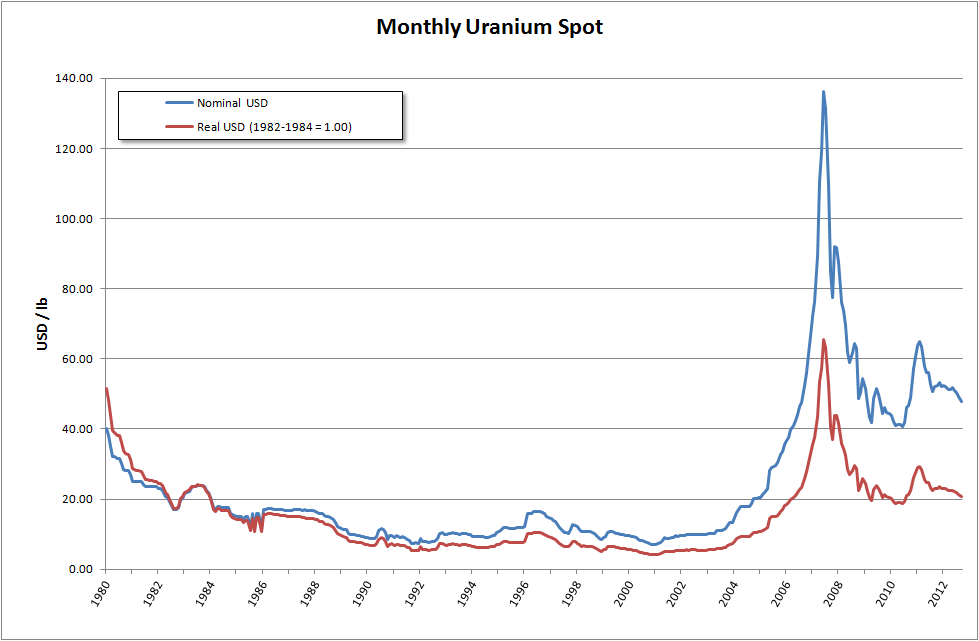

To be considered 'enriched', the uranium-235 fraction should be between 3% and 5%. This process produces huge quantities of uranium that is depleted of uranium-235 and with a correspondingly increased fraction of uranium-238, called depleted uranium or 'DU'. To be considered 'depleted', the U concentration should be no more than 0.3%. The price of uranium has risen since 2001, so enrichment tailings containing more than 0.35% uranium-235 are being considered for re-enrichment, driving the price of depleted uranium hexafluoride above $130 per kilogram in July 2007 from $5 in 2001.

The gas centrifuge process, where gaseous uranium hexafluoride () is separated by the difference in molecular weight between UF and UF using high-speed centrifuges, is the cheapest and leading enrichment process. The gaseous diffusion process had been the leading method for enrichment and was used in the Manhattan Project. In this process, uranium hexafluoride is repeatedly diffused through a

In nature, uranium is found as uranium-238 (99.2742%) and uranium-235 (0.7204%). Isotope separation concentrates (enriches) the fissile uranium-235 for nuclear weapons and most nuclear power plants, except for gas cooled reactors and pressurized heavy water reactors. Most neutrons released by a fissioning atom of uranium-235 must impact other uranium-235 atoms to sustain the nuclear chain reaction. The concentration and amount of uranium-235 needed to achieve this is called a ' critical mass'.

To be considered 'enriched', the uranium-235 fraction should be between 3% and 5%. This process produces huge quantities of uranium that is depleted of uranium-235 and with a correspondingly increased fraction of uranium-238, called depleted uranium or 'DU'. To be considered 'depleted', the U concentration should be no more than 0.3%. The price of uranium has risen since 2001, so enrichment tailings containing more than 0.35% uranium-235 are being considered for re-enrichment, driving the price of depleted uranium hexafluoride above $130 per kilogram in July 2007 from $5 in 2001.

The gas centrifuge process, where gaseous uranium hexafluoride () is separated by the difference in molecular weight between UF and UF using high-speed centrifuges, is the cheapest and leading enrichment process. The gaseous diffusion process had been the leading method for enrichment and was used in the Manhattan Project. In this process, uranium hexafluoride is repeatedly diffused through a

Nuclear fuel data and analysis

from the U.S. Energy Information Administration

World Uranium deposit maps

*

Annotated bibliography for uranium from the Alsos Digital Library

NLM Hazardous Substances Databank – Uranium, Radioactive

U.S.

Uranium

at '' The Periodic Table of Videos'' (University of Nottingham) {{Authority control Chemical elements Actinides Nuclear fuels Nuclear materials Suspected male-mediated teratogens Manhattan Project Pyrophoric materials

chemical element

A chemical element is a chemical substance whose atoms all have the same number of protons. The number of protons is called the atomic number of that element. For example, oxygen has an atomic number of 8: each oxygen atom has 8 protons in its ...

; it has symbol

A symbol is a mark, Sign (semiotics), sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, physical object, object, or wikt:relationship, relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by cr ...

U and atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of its atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei composed of protons and neutrons, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of pro ...

92. It is a silvery-grey metal

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, electricity and thermal conductivity, heat relatively well. These properties are all associated wit ...

in the actinide series of the periodic table

The periodic table, also known as the periodic table of the elements, is an ordered arrangement of the chemical elements into rows (" periods") and columns (" groups"). It is an icon of chemistry and is widely used in physics and other s ...

. A uranium atom has 92 proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , Hydron (chemistry), H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' (elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an e ...

s and 92 electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium radioactively decays, usually by emitting an alpha particle. The half-life Half-life is a mathematical and scientific description of exponential or gradual decay.

Half-life, half life or halflife may also refer to:

Film

* Half-Life (film), ''Half-Life'' (film), a 2008 independent film by Jennifer Phang

* ''Half Life: ...

of this decay varies between 159,200 and 4.5 billion years for different isotopes, making them useful for dating the age of the Earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years. This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion (astrophysics), accretion, or Internal structure of Earth, core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating ...

. The most common isotopes in natural uranium are uranium-238 (which has 146 neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The Discovery of the neutron, neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nucle ...

s and accounts for over 99% of uranium on Earth) and uranium-235 (which has 143 neutrons). Uranium has the highest atomic weight of the primordially occurring elements. Its density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the ratio of a substance's mass to its volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' (or ''d'') can also be u ...

is about 70% higher than that of lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

and slightly lower than that of gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

or tungsten. It occurs naturally in low concentrations of a few parts per million in soil, rock and water, and is commercially extracted from uranium-bearing mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

s such as uraninite.

Many contemporary uses of uranium exploit its unique nuclear properties. Uranium is used in nuclear power plant

A nuclear power plant (NPP), also known as a nuclear power station (NPS), nuclear generating station (NGS) or atomic power station (APS) is a thermal power station in which the heat source is a nuclear reactor. As is typical of thermal power st ...

s and nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s because it is the only naturally occurring element with a fissile isotope – uranium-235 – present in non-trace amounts. However, because of the low abundance of uranium-235 in natural uranium (which is overwhelmingly uranium-238), uranium needs to undergo enrichment so that enough uranium-235 is present. Uranium-238 is fissionable by fast neutrons and is fertile, meaning it can be transmuted to fissile plutonium-239 in a nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

. Another fissile isotope, uranium-233, can be produced from natural thorium and is studied for future industrial use in nuclear technology. Uranium-238 has a small probability for spontaneous fission or even induced fission with fast neutrons; uranium-235, and to a lesser degree uranium-233, have a much higher fission cross-section for slow neutrons. In sufficient concentration, these isotopes maintain a sustained nuclear chain reaction. This generates the heat in nuclear power reactors and produces the fissile material for nuclear weapons. The primary civilian use for uranium harnesses the heat energy to produce electricity. Depleted uranium (U) is used in kinetic energy penetrators and armor plating.

The 1789 discovery

Discovery may refer to:

* Discovery (observation), observing or finding something unknown

* Discovery (fiction), a character's learning something unknown

* Discovery (law), a process in courts of law relating to evidence

Discovery, The Discovery ...

of uranium in the mineral pitchblende

Uraninite, also known as pitchblende, is a radioactive, uranium-rich mineral and ore with a chemical composition that is largely UO2 but because of oxidation typically contains variable proportions of U3O8. Radioactive decay of the urani ...

is credited to Martin Heinrich Klaproth, who named the new element after the recently discovered planet Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. It is a gaseous cyan-coloured ice giant. Most of the planet is made of water, ammonia, and methane in a Supercritical fluid, supercritical phase of matter, which astronomy calls "ice" or Volatile ( ...

. Eugène-Melchior Péligot

Eugène-Melchior Péligot (24 March 1811 – 15 April 1890), also known as Eugène Péligot, was a French chemist who isolated the first sample of uranium metal in 1841.

Péligot proved that the black powder of Martin Heinrich Klaproth was not ...

was the first person to isolate the metal, and its radioactive properties were discovered in 1896 by Henri Becquerel. Research by Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner

Elise Lise Meitner ( ; ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish nuclear physicist who was instrumental in the discovery of nuclear fission.

After completing her doctoral research in 1906, Meitner became the second woman ...

, Enrico Fermi and others, such as J. Robert Oppenheimer starting in 1934 led to its use as a fuel in the nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced by ...

industry and in Little Boy, the first nuclear weapon used in war. An ensuing arms race during the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

between the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

produced tens of thousands of nuclear weapons that used uranium metal and uranium-derived plutonium-239. Dismantling of these weapons and related nuclear facilities is carried out within various nuclear disarmament programs and costs billions of dollars. Weapon-grade uranium obtained from nuclear weapons is diluted with uranium-238 and reused as fuel for nuclear reactors. Spent nuclear fuel forms radioactive waste

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. It is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, nuclear decommissioning, rare-earth mining, and nuclear ...

, which mostly consists of uranium-238 and poses a significant health threat and environmental impact.

Characteristics

metal

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electrical resistivity and conductivity, electricity and thermal conductivity, heat relatively well. These properties are all associated wit ...

. It has a Mohs hardness of 6, sufficient to scratch glass and roughly equal to that of titanium, rhodium, manganese

Manganese is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese was first isolated in the 1770s. It is a transition m ...

and niobium

Niobium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Nb (formerly columbium, Cb) and atomic number 41. It is a light grey, crystalline, and Ductility, ductile transition metal. Pure niobium has a Mohs scale of mineral hardness, Mohs h ...

. It is malleable, ductile, slightly paramagnetic, strongly electropositive and a poor electrical conductor. Uranium metal has a very high density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the ratio of a substance's mass to its volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' (or ''d'') can also be u ...

of 19.1 g/cm, denser than lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

(11.3 g/cm), but slightly less dense than tungsten and gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

(19.3 g/cm).

Uranium metal reacts with almost all non-metallic elements (except noble gas

The noble gases (historically the inert gases, sometimes referred to as aerogens) are the members of Group (periodic table), group 18 of the periodic table: helium (He), neon (Ne), argon (Ar), krypton (Kr), xenon (Xe), radon (Rn) and, in some ...

es) and their compounds, with reactivity increasing with temperature. Hydrochloric and nitric acid

Nitric acid is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but samples tend to acquire a yellow cast over time due to decomposition into nitrogen oxide, oxides of nitrogen. Most com ...

s dissolve uranium, but non-oxidizing acids other than hydrochloric acid attack the element very slowly. When finely divided, it can react with cold water; in air, uranium metal becomes coated with a dark layer of uranium dioxide. Uranium in ores is extracted chemically and converted into uranium dioxide or other chemical forms usable in industry.

Uranium-235 was the first isotope that was found to be fissile. Other naturally occurring isotopes are fissionable, but not fissile. On bombardment with slow neutrons, uranium-235 most of the time splits into two smaller nuclei, releasing nuclear binding energy

In physics and chemistry, binding energy is the smallest amount of energy required to remove a particle from a system of particles or to disassemble a system of particles into individual parts. In the former meaning the term is predominantly use ...

and more neutrons. If too many of these neutrons are absorbed by other uranium-235 nuclei, a nuclear chain reaction occurs that results in a burst of heat or (in some circumstances) an explosion. In a nuclear reactor, such a chain reaction is slowed and controlled by a neutron poison, absorbing some of the free neutrons. Such neutron absorbent materials are often part of reactor control rods (see nuclear reactor physics for a description of this process of reactor control).

As little as of uranium-235 can be used to make an atomic bomb. The nuclear weapon detonated over Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui has b ...

, called Little Boy, relied on uranium fission. However, the first nuclear bomb (the ''Gadget'' used at Trinity) and the bomb that was detonated over Nagasaki ( Fat Man) were both plutonium bombs.

Uranium metal has three allotropic forms:

* α ( orthorhombic) stable up to . Orthorhombic, space group No. 63, ''Cmcm'', lattice parameters ''a'' = 285.4 pm, ''b'' = 587 pm, ''c'' = 495.5 pm.

* β (tetragonal

In crystallography, the tetragonal crystal system is one of the 7 crystal systems. Tetragonal crystal lattices result from stretching a cubic lattice along one of its lattice vectors, so that the Cube (geometry), cube becomes a rectangular Pri ...

) stable from . Tetragonal, space group ''P''42/''mnm'', ''P''42''nm'', or ''P''4''n''2, lattice parameters ''a'' = 565.6 pm, ''b'' = ''c'' = 1075.9 pm.

* γ ( body-centered cubic) from to melting point—this is the most malleable and ductile state. Body-centered cubic, lattice parameter ''a'' = 352.4 pm.

Applications

Military

The major application of uranium in the military sector is in high-density penetrating projectiles. This ammunition consists of depleted uranium (DU) alloyed with 1–2% other elements, such as titanium or

The major application of uranium in the military sector is in high-density penetrating projectiles. This ammunition consists of depleted uranium (DU) alloyed with 1–2% other elements, such as titanium or molybdenum

Molybdenum is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mo (from Neo-Latin ''molybdaenum'') and atomic number 42. The name derived from Ancient Greek ', meaning lead, since its ores were confused with lead ores. Molybdenum minerals hav ...

. At high impact speed, the density, hardness, and pyrophoricity of the projectile enable the destruction of heavily armored targets. Tank armor and other removable vehicle armor can also be hardened with depleted uranium plates. The use of depleted uranium became politically and environmentally contentious after the use of such munitions by the US, UK and other countries during wars in the Persian Gulf and the Balkans raised health questions concerning uranium compounds left in the soil (see Gulf War syndrome).

Depleted uranium is also used as a shielding material in some containers used to store and transport radioactive materials. While the metal itself is radioactive, its high density makes it more effective than lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

in halting radiation from strong sources such as radium. Other uses of depleted uranium include counterweights for aircraft control surfaces, as ballast for missile re-entry vehicles and as a shielding material. Due to its high density, this material is found in inertial guidance systems and in gyroscopic compasses. Depleted uranium is preferred over similarly dense metals due to its ability to be easily machined and cast as well as its relatively low cost. The main risk of exposure to depleted uranium is chemical poisoning by uranium oxide rather than radioactivity (uranium being only a weak alpha emitter).

During the later stages of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the entire Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, and to a lesser extent afterwards, uranium-235 has been used as the fissile explosive material to produce nuclear weapons. Initially, two major types of fission bombs were built: a relatively simple device that uses uranium-235 and a more complicated mechanism that uses plutonium-239 derived from uranium-238. Later, a much more complicated and far more powerful type of fission/fusion bomb (thermonuclear weapon

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

) was built, that uses a plutonium-based device to cause a mixture of tritium and deuterium to undergo nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a nuclear reaction, reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei combine to form a larger nuclei, nuclei/neutrons, neutron by-products. The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifested as either the rele ...

. Such bombs are jacketed in a non-fissile (unenriched) uranium case, and they derive more than half their power from the fission of this material by fast neutrons from the nuclear fusion process.

Civilian

The main use of uranium in the civilian sector is to fuelnuclear power plant

A nuclear power plant (NPP), also known as a nuclear power station (NPS), nuclear generating station (NGS) or atomic power station (APS) is a thermal power station in which the heat source is a nuclear reactor. As is typical of thermal power st ...

s. One kilogram of uranium-235 can theoretically produce about 20 terajoules of energy (2 joule

The joule ( , or ; symbol: J) is the unit of energy in the International System of Units (SI). In terms of SI base units, one joule corresponds to one kilogram- metre squared per second squared One joule is equal to the amount of work d ...

s), assuming complete fission; as much energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

as 1.5 million kilograms (1,500 tonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1,000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton in the United States to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the s ...

s) of coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

.

Commercial nuclear power plants use fuel that is typically enriched to around 3% uranium-235. The CANDU and Magnox designs are the only commercial reactors capable of using unenriched uranium fuel. Fuel used for United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

reactors is typically highly enriched in uranium-235 (the exact values are classified). In a breeder reactor, uranium-238 can also be converted into plutonium-239 through the following reaction:

: + n + γ

Before (and, occasionally, after) the discovery of radioactivity, uranium was primarily used in small amounts for yellow glass and pottery glazes, such as uranium glass and in Fiestaware.

The discovery and isolation of radium in uranium ore (pitchblende) by Marie Curie sparked the development of uranium mining to extract the radium, which was used to make glow-in-the-dark paints for clock and aircraft dials. This left a prodigious quantity of uranium as a waste product, since it takes three tonnes of uranium to extract one gram of radium. This waste product was diverted to the glazing industry, making uranium glazes very inexpensive and abundant. Besides the pottery glazes, uranium tile glazes accounted for the bulk of the use, including common bathroom and kitchen tiles which can be produced in green, yellow, mauve, black, blue, red and other colors.

Uranium was also used in photographic chemicals (especially uranium nitrate as a toner), in lamp filaments for stage lighting bulbs, to improve the appearance of dentures, and in the leather and wood industries for stains and dyes. Uranium salts are mordants of silk or wool. Uranyl acetate and uranyl formate are used as electron-dense "stains" in

Before (and, occasionally, after) the discovery of radioactivity, uranium was primarily used in small amounts for yellow glass and pottery glazes, such as uranium glass and in Fiestaware.

The discovery and isolation of radium in uranium ore (pitchblende) by Marie Curie sparked the development of uranium mining to extract the radium, which was used to make glow-in-the-dark paints for clock and aircraft dials. This left a prodigious quantity of uranium as a waste product, since it takes three tonnes of uranium to extract one gram of radium. This waste product was diverted to the glazing industry, making uranium glazes very inexpensive and abundant. Besides the pottery glazes, uranium tile glazes accounted for the bulk of the use, including common bathroom and kitchen tiles which can be produced in green, yellow, mauve, black, blue, red and other colors.

Uranium was also used in photographic chemicals (especially uranium nitrate as a toner), in lamp filaments for stage lighting bulbs, to improve the appearance of dentures, and in the leather and wood industries for stains and dyes. Uranium salts are mordants of silk or wool. Uranyl acetate and uranyl formate are used as electron-dense "stains" in transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is a microscopy technique in which a beam of electrons is transmitted through a specimen to form an image. The specimen is most often an ultrathin section less than 100 nm thick or a suspension on a g ...

, to increase the contrast of biological specimens in ultrathin sections and in negative staining of virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es, isolated cell organelles and macromolecules.

The discovery of the radioactivity of uranium ushered in additional scientific and practical uses of the element. The long half-life Half-life is a mathematical and scientific description of exponential or gradual decay.

Half-life, half life or halflife may also refer to:

Film

* Half-Life (film), ''Half-Life'' (film), a 2008 independent film by Jennifer Phang

* ''Half Life: ...

of uranium-238 (4.47 years) makes it well-suited for use in estimating the age of the earliest igneous rocks and for other types of radiometric dating

Radiometric dating, radioactive dating or radioisotope dating is a technique which is used to Chronological dating, date materials such as Rock (geology), rocks or carbon, in which trace radioactive impurity, impurities were selectively incorporat ...

, including uranium–thorium dating, uranium–lead dating and uranium–uranium dating. Uranium metal is used for X-ray

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

targets in the making of high-energy X-rays.

History

Pre-discovery use

The use ofpitchblende

Uraninite, also known as pitchblende, is a radioactive, uranium-rich mineral and ore with a chemical composition that is largely UO2 but because of oxidation typically contains variable proportions of U3O8. Radioactive decay of the urani ...

, uranium in its natural oxide

An oxide () is a chemical compound containing at least one oxygen atom and one other element in its chemical formula. "Oxide" itself is the dianion (anion bearing a net charge of −2) of oxygen, an O2− ion with oxygen in the oxidation st ...

form, dates back to at least the year 79 AD, when it was used in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

to add a yellow color to ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant, and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcela ...

glazes. Yellow glass with 1% uranium oxide was found in a Roman villa on Cape Posillipo in the Gulf of Naples

The Gulf of Naples (), also called the Bay of Naples, is a roughly 15-kilometer-wide (9.3 mi) gulf located along the south-western coast of Italy (Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania region). It opens to the west into the Mediterranean ...

, Italy, by R. T. Gunther of the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

in 1912. Starting in the late Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, pitchblende was extracted from the Habsburg silver mines in Joachimsthal, Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

(now Jáchymov in the Czech Republic) in the Ore Mountains

The Ore Mountains (, or ; ) lie along the Czech–German border, separating the historical regions of Bohemia in the Czech Republic and Saxony in Germany. The highest peaks are the Klínovec in the Czech Republic (German: ''Keilberg'') at ab ...

, and was used as a coloring agent in the local glass

Glass is an amorphous (non-crystalline solid, non-crystalline) solid. Because it is often transparency and translucency, transparent and chemically inert, glass has found widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in window pane ...

making industry. In the early 19th century, the world's only known sources of uranium ore were these mines.

Discovery

The

The discovery

Discovery may refer to:

* Discovery (observation), observing or finding something unknown

* Discovery (fiction), a character's learning something unknown

* Discovery (law), a process in courts of law relating to evidence

Discovery, The Discovery ...

of the element is credited to the German chemist Martin Heinrich Klaproth. While he was working in his experimental laboratory in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

in 1789, Klaproth was able to precipitate a yellow compound (likely sodium diuranate) by dissolving pitchblende

Uraninite, also known as pitchblende, is a radioactive, uranium-rich mineral and ore with a chemical composition that is largely UO2 but because of oxidation typically contains variable proportions of U3O8. Radioactive decay of the urani ...

in nitric acid

Nitric acid is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but samples tend to acquire a yellow cast over time due to decomposition into nitrogen oxide, oxides of nitrogen. Most com ...

and neutralizing the solution with sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly corrosive base (chemistry), ...

. Klaproth assumed the yellow substance was the oxide of a yet-undiscovered element and heated it with charcoal to obtain a black powder, which he thought was the newly discovered metal itself (in fact, that powder was an oxide of uranium). He named the newly discovered element after the planet Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. It is a gaseous cyan-coloured ice giant. Most of the planet is made of water, ammonia, and methane in a Supercritical fluid, supercritical phase of matter, which astronomy calls "ice" or Volatile ( ...

(named after the primordial Greek god of the sky), which had been discovered eight years earlier by William Herschel

Frederick William Herschel ( ; ; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline Herschel. Born in the Electorate of Hanover ...

.

In 1841, Eugène-Melchior Péligot

Eugène-Melchior Péligot (24 March 1811 – 15 April 1890), also known as Eugène Péligot, was a French chemist who isolated the first sample of uranium metal in 1841.

Péligot proved that the black powder of Martin Heinrich Klaproth was not ...

, Professor of Analytical Chemistry at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers (Central School of Arts and Manufactures) in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, isolated the first sample of uranium metal by heating uranium tetrachloride with potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

.

Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity by using uranium in 1896. Becquerel made the discovery in Paris by leaving a sample of a uranium salt, KUO(SO) (potassium uranyl sulfate), on top of an unexposed photographic plate in a drawer and noting that the plate had become "fogged". He determined that a form of invisible light or rays emitted by uranium had exposed the plate.

During World War I when the

Henri Becquerel discovered radioactivity by using uranium in 1896. Becquerel made the discovery in Paris by leaving a sample of a uranium salt, KUO(SO) (potassium uranyl sulfate), on top of an unexposed photographic plate in a drawer and noting that the plate had become "fogged". He determined that a form of invisible light or rays emitted by uranium had exposed the plate.

During World War I when the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

suffered a shortage of molybdenum to make artillery gun barrels and high speed tool steels, they routinely used ferrouranium alloy as a substitute, as it presents many of the same physical characteristics as molybdenum. When this practice became known in 1916 the US government requested several prominent universities to research the use of uranium in manufacturing and metalwork. Tools made with these formulas remained in use for several decades, until the Manhattan Project and the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

placed a large demand on uranium for fission research and weapon development.

Fission research

A team led by Enrico Fermi in 1934 found that bombarding uranium with neutrons produces beta rays (

A team led by Enrico Fermi in 1934 found that bombarding uranium with neutrons produces beta rays (electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s or positron

The positron or antielectron is the particle with an electric charge of +1''elementary charge, e'', a Spin (physics), spin of 1/2 (the same as the electron), and the same Electron rest mass, mass as an electron. It is the antiparticle (antimatt ...

s from the elements produced; see beta particle). The fission products were at first mistaken for new elements with atomic numbers 93 and 94, which the Dean of the Sapienza University of Rome, Orso Mario Corbino, named ausenium and hesperium, respectively. The experiments leading to the discovery of uranium's ability to fission (break apart) into lighter elements and release binding energy

In physics and chemistry, binding energy is the smallest amount of energy required to remove a particle from a system of particles or to disassemble a system of particles into individual parts. In the former meaning the term is predominantly use ...

were conducted by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in Hahn's laboratory in Berlin. Lise Meitner

Elise Lise Meitner ( ; ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish nuclear physicist who was instrumental in the discovery of nuclear fission.

After completing her doctoral research in 1906, Meitner became the second woman ...

and her nephew, physicist Otto Robert Frisch, published the physical explanation in February 1939 and named the process "nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactiv ...

". Soon after, Fermi hypothesized that fission of uranium might release enough neutrons to sustain a fission reaction. Confirmation of this hypothesis came in 1939, and later work found that on average about 2.5 neutrons are released by each fission of uranium-235. Fermi urged Alfred O. C. Nier to separate uranium isotopes for determination of the fissile component, and on 29 February 1940, Nier used an instrument he built at the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota Twin Cities (historically known as University of Minnesota) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint ...

to separate the world's first uranium-235 sample in the Tate Laboratory. Using Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

's cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Januar ...

, John Dunning confirmed the sample to be the isolated fissile material on 1 March. Further work found that the far more common uranium-238 isotope can be transmuted into plutonium, which, like uranium-235, is also fissile by thermal neutrons. These discoveries led numerous countries to begin working on the development of nuclear weapons and nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced by ...

. Despite fission having been discovered in Germany, the '' Uranverein'' ("uranium club") Germany's wartime project to research nuclear power and/or weapons was hampered by limited resources, infighting, the exile or non-involvement of several prominent scientists in the field and several crucial mistakes such as failing to account for impurities in available graphite samples which made it appear less suitable as a neutron moderator than it is in reality. Germany's attempts to build a natural uranium / heavy water

Heavy water (deuterium oxide, , ) is a form of water (molecule), water in which hydrogen atoms are all deuterium ( or D, also known as ''heavy hydrogen'') rather than the common hydrogen-1 isotope (, also called ''protium'') that makes up most o ...

reactor had not come close to reaching criticality by the time the Americans reached Haigerloch, the site of the last German wartime reactor experiment.

On 2 December 1942, as part of the Manhattan Project, another team led by Enrico Fermi was able to initiate the first artificial self-sustained nuclear chain reaction, Chicago Pile-1. An initial plan using enriched uranium-235 was abandoned as it was as yet unavailable in sufficient quantities. Working in a lab below the stands of Stagg Field at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

, the team created the conditions needed for such a reaction by piling together 360 tonnes of graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

, 53 tonnes of uranium oxide, and 5.5 tonnes of uranium metal, most of which was supplied by Westinghouse Lamp Plant in a makeshift production process.

Nuclear weaponry

Two types of atomic bomb were developed by the United States during

Two types of atomic bomb were developed by the United States during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

: a uranium-based device (codenamed "Little Boy") whose fissile material was highly enriched uranium, and a plutonium-based device (see Trinity test and "Fat Man") whose plutonium was derived from uranium-238. Little Boy became the first nuclear weapon used in war when it was detonated over Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui has b ...

, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, on 6 August 1945. Exploding with a yield equivalent to 12,500 tonnes of TNT, the blast and thermal wave of the bomb destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings and killed about 75,000 people (see Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, during World War II. The aerial bombings killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civili ...

). Initially it was believed that uranium was relatively rare, and that nuclear proliferation could be avoided by simply buying up all known uranium stocks, but within a decade large deposits of it were discovered in many places around the world.

Reactors

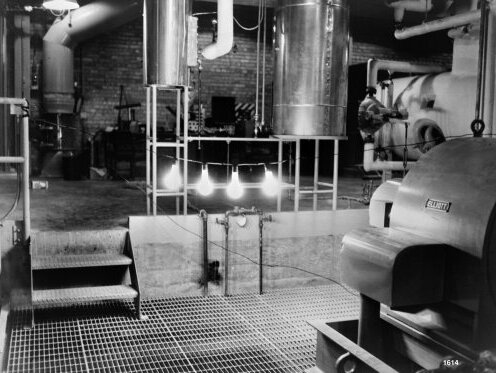

The X-10 Graphite Reactor at

The X-10 Graphite Reactor at Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) is a federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, United States. Founded in 1943, the laboratory is sponsored by the United Sta ...

(ORNL) in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, formerly known as the Clinton Pile and X-10 Pile, was the world's second artificial nuclear reactor (after Enrico Fermi's Chicago Pile) and was the first reactor designed and built for continuous operation. Argonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory is a Federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center in Lemont, Illinois, Lemont, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1946, the laboratory is owned by the United Sta ...

's Experimental Breeder Reactor I, located at the Atomic Energy Commission's National Reactor Testing Station near Arco, Idaho, became the first nuclear reactor to create electricity on 20 December 1951. Initially, four 150-watt light bulbs were lit by the reactor, but improvements eventually enabled it to power the whole facility (later, the town of Arco became the first in the world to have all its electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

come from nuclear power generated by BORAX-III, another reactor designed and operated by Argonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory is a Federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center in Lemont, Illinois, Lemont, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1946, the laboratory is owned by the United Sta ...

). The world's first commercial scale nuclear power station, Obninsk in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, began generation with its reactor AM-1 on 27 June 1954. Other early nuclear power plants were Calder Hall in England, which began generation on 17 October 1956, and the Shippingport Atomic Power Station in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, which began on 26 May 1958. Nuclear power was used for the first time for propulsion by a submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

, the USS ''Nautilus'', in 1954.

Prehistoric naturally occurring fission

In 1972, French physicist Francis Perrin discovered fifteen ancient and no longer active natural nuclear fission reactors in three separate ore deposits at the Oklo mine inGabon

Gabon ( ; ), officially the Gabonese Republic (), is a country on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa, on the equator, bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north, the Republic of the Congo to the east and south, and ...

, Africa, collectively known as the Oklo Fossil Reactors. The ore deposit is 1.7 billion years old; then, uranium-235 constituted about 3% of uranium on Earth. This is high enough to permit a sustained chain reaction, if other supporting conditions exist. The capacity of the surrounding sediment to contain the health-threatening nuclear waste products has been cited by the U.S. federal government as supporting evidence for the feasibility to store spent nuclear fuel at the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository.

Contamination and the Cold War legacy

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

into the 1970s and 1980s spread a significant amount of fallout from uranium daughter isotopes around the world. Additional fallout and pollution occurred from several nuclear accidents.

Uranium miners have a higher incidence of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

. An excess risk of lung cancer among Navajo uranium miners, for example, has been documented and linked to their occupation. The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, a 1990 law in the US, required $100,000 in "compassion payments" to uranium miners diagnosed with cancer or other respiratory ailments.

During the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

between the Soviet Union and the United States, huge stockpiles of uranium were amassed and tens of thousands of nuclear weapons were created using enriched uranium and plutonium made from uranium. After the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, an estimated 600 short tons (540 metric tons) of highly enriched weapons grade uranium (enough to make 40,000 nuclear warheads) had been stored in often inadequately guarded facilities in the Russian Federation

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and several other former Soviet states. Police in Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

on at least 16 occasions from 1993 to 2005 have intercepted shipments of smuggled bomb-grade uranium or plutonium, most of which was from ex-Soviet sources. From 1993 to 2005 the Material Protection, Control, and Accounting Program, operated by the federal government of the United States

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the Federation#Federal governments, national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct ...

, spent about US$550 million to help safeguard uranium and plutonium stockpiles in Russia. This money was used for improvements and security enhancements at research and storage facilities.

Safety of nuclear facilities in Russia has been significantly improved since the stabilization of political and economical turmoil of the early 1990s. For example, in 1993 there were 29 incidents ranking above level 1 on the International Nuclear Event Scale, and this number dropped under four per year in 1995–2003. The number of employees receiving annual radiation doses above 20 mSv, which is equivalent to a single full-body CT scan

A computed tomography scan (CT scan), formerly called computed axial tomography scan (CAT scan), is a medical imaging technique used to obtain detailed internal images of the body. The personnel that perform CT scans are called radiographers or ...

, saw a strong decline around 2000. In November 2015, the Russian government approved a federal program for nuclear and radiation safety for 2016 to 2030 with a budget of 562 billion rubles (ca. 8 billion USD). Its key issue is "the deferred liabilities accumulated during the 70 years of the nuclear industry, particularly during the time of the Soviet Union". About 73% of the budget will be spent on decommissioning aged and obsolete nuclear reactors and nuclear facilities, especially those involved in state defense programs; 20% will go in processing and disposal of nuclear fuel and radioactive waste, and 5% into monitoring and ensuring of nuclear and radiation safety.

Occurrence

Uranium is a naturally occurring element found in low levels in all rock, soil, and water. It is the highest-numbered element found naturally in significant quantities on Earth and is almost always found combined with other elements. Uranium is the 48th most abundant element in the Earth’s crust. The decay of uranium, thorium, andpotassium-40

Potassium-40 (K) is a long lived and the main naturally occurring radioactive isotope of potassium. Its half-life is 1.25 billion years. It makes up about 0.012% (120 parts-per notation, ppm) of natural potassium.

Potassium-40 undergoes four dif ...

in Earth's mantle is thought to be the main source of heat that keeps the Earth's outer core in the liquid state and drives mantle convection, which in turn drives plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

.

Uranium's concentration in the Earth's crust is (depending on the reference) 2 to 4 parts per million, or about 40 times as abundant as silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

. The Earth's crust from the surface to 25 km (15 mi) down is calculated to contain 10 kg (2 lb) of uranium while the ocean

The ocean is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of Earth. The ocean is conventionally divided into large bodies of water, which are also referred to as ''oceans'' (the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Indian, Southern Ocean ...

s may contain 10 kg (2 lb). The concentration of uranium in soil ranges from 0.7 to 11 parts per million (up to 15 parts per million in farmland soil due to use of phosphate fertilizers), and its concentration in sea water is 3 parts per billion.

Uranium is more plentiful than antimony

Antimony is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Sb () and atomic number 51. A lustrous grey metal or metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient t ...

, tin, cadmium, mercury, or silver, and it is about as abundant as arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol As and atomic number 33. It is a metalloid and one of the pnictogens, and therefore shares many properties with its group 15 neighbors phosphorus and antimony. Arsenic is not ...

or molybdenum

Molybdenum is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mo (from Neo-Latin ''molybdaenum'') and atomic number 42. The name derived from Ancient Greek ', meaning lead, since its ores were confused with lead ores. Molybdenum minerals hav ...

. Uranium is found in hundreds of minerals, including uraninite (the most common uranium ore), carnotite, autunite, uranophane, torbernite, and coffinite. Significant concentrations of uranium occur in some substances such as phosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

rock deposits, and minerals such as lignite, and monazite sands in uranium-rich ores (it is recovered commercially from sources with as little as 0.1% uranium).

Origin

Like all elements with atomic weights higher than that ofiron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

, uranium is only naturally formed by the r-process

In nuclear astrophysics, the rapid neutron-capture process, also known as the ''r''-process, is a set of nuclear reactions that is responsible for nucleosynthesis, the creation of approximately half of the Atomic nucleus, atomic nuclei Heavy meta ...

(rapid neutron capture) in supernova

A supernova (: supernovae or supernovas) is a powerful and luminous explosion of a star. A supernova occurs during the last stellar evolution, evolutionary stages of a massive star, or when a white dwarf is triggered into runaway nuclear fusion ...

e and neutron star merger

A neutron star merger is the stellar collision of neutron stars. When two neutron stars fall into mutual orbit, they gradually inspiral, spiral inward due to the loss of energy emitted as gravitational radiation. When they finally meet, their me ...

s. Primordial thorium and uranium are only produced in the r-process, because the s-process (slow neutron capture) is too slow and cannot pass the gap of instability after bismuth. Besides the two extant primordial uranium isotopes, U and U, the r-process also produced significant quantities of U, which has a shorter half-life and so is an extinct radionuclide, having long since decayed completely to Th. Further uranium-236 was produced by the decay of Pu, accounting for the observed higher-than-expected abundance of thorium and lower-than-expected abundance of uranium. While the natural abundance of uranium has been supplemented by the decay of extinct Pu (half-life 375,000 years) and Cm (half-life 16 million years), producing U and U respectively, this occurred to an almost negligible extent due to the shorter half-lives of these parents and their lower production than U and Pu, the parents of thorium: the Cm/U ratio at the formation of the Solar System was .

Biotic and abiotic

Some bacteria, such as '' Shewanella putrefaciens'', '' Geobacter metallireducens'' and some strains of '' Burkholderia fungorum'', can use uranium for their growth and convert U(VI) to U(IV). Recent research suggests that this pathway includes reduction of the soluble U(VI) via an intermediate U(V) pentavalent state.

Other organisms, such as the

Some bacteria, such as '' Shewanella putrefaciens'', '' Geobacter metallireducens'' and some strains of '' Burkholderia fungorum'', can use uranium for their growth and convert U(VI) to U(IV). Recent research suggests that this pathway includes reduction of the soluble U(VI) via an intermediate U(V) pentavalent state.

Other organisms, such as the lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

''Trapelia involuta'' or microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s such as the bacterium '' Citrobacter'', can absorb concentrations of uranium that are up to 300 times the level of their environment. ''Citrobacter'' species absorb uranyl ions when given glycerol phosphate (or other similar organic phosphates). After one day, one gram of bacteria can encrust themselves with nine grams of uranyl phosphate crystals; this creates the possibility that these organisms could be used in bioremediation to decontaminate uranium-polluted water.

The proteobacterium '' Geobacter'' has also been shown to bioremediate uranium in ground water. The mycorrhizal fungus '' Glomus intraradices'' increases uranium content in the roots of its symbiotic plant.

In nature, uranium(VI) forms highly soluble carbonate complexes at alkaline pH. This leads to an increase in mobility and availability of uranium to groundwater and soil from nuclear wastes which leads to health hazards. However, it is difficult to precipitate uranium as phosphate in the presence of excess carbonate at alkaline pH. A '' Sphingomonas'' sp. strain BSAR-1 has been found to express a high activity alkaline phosphatase (PhoK) that has been applied for bioprecipitation of uranium as uranyl phosphate species from alkaline solutions. The precipitation ability was enhanced by overexpressing PhoK protein in '' E. coli''.

Plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s absorb some uranium from soil. Dry weight concentrations of uranium in plants range from 5 to 60 parts per billion, and ash from burnt wood can have concentrations up to 4 parts per million. Dry weight concentrations of uranium in food

Food is any substance consumed by an organism for Nutrient, nutritional support. Food is usually of plant, animal, or Fungus, fungal origin and contains essential nutrients such as carbohydrates, fats, protein (nutrient), proteins, vitamins, ...

plants are typically lower with one to two micrograms per day ingested through the food people eat.

Production and mining

Worldwide production of uranium in 2021 was 48,332tonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1,000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton in the United States to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the s ...

s, of which 21,819 t (45%) was mined in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

. Other important uranium mining countries are Namibia

Namibia, officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country on the west coast of Southern Africa. Its borders include the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south; in the no ...

(5,753 t), Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

(4,693 t), Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

(4,192 t), Uzbekistan

, image_flag = Flag of Uzbekistan.svg

, image_coat = Emblem of Uzbekistan.svg

, symbol_type = Emblem of Uzbekistan, Emblem

, national_anthem = "State Anthem of Uzbekistan, State Anthem of the Republ ...

(3,500 t), and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

(2,635 t).

Uranium ore is mined in several ways: open pit, underground, in-situ leaching, and borehole mining. Low-grade uranium ore mined typically contains 0.01 to 0.25% uranium oxides. Extensive measures must be employed to extract the metal from its ore. High-grade ores found in Athabasca Basin

The Athabasca Basin is a region in the Canadian Shield of northern Saskatchewan and Alberta, Canada. It is best known as the world's leading source of high-grade uranium and currently supplies about 20% of the world's uranium.

The basin i ...

deposits in Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada. It is bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and to the south by the ...

, Canada can contain up to 23% uranium oxides on average. Uranium ore is crushed and rendered into a fine powder and then leached with either an acid

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...

or alkali. The leachate

A leachate is any liquid that, in the course of passing through matter, extracts soluble or suspended solids, or any other component of the material through which it has passed.

Leachate is a widely used term in the environmental sciences wh ...

is subjected to one of several sequences of precipitation, solvent extraction, and ion exchange. The resulting mixture, called yellowcake, contains at least 75% uranium oxides UO. Yellowcake is then calcined to remove impurities from the milling process before refining and conversion.

Commercial-grade uranium can be produced through the reduction of uranium halides with alkali or alkaline earth metal

The alkaline earth metals are six chemical elements in group (periodic table), group 2 of the periodic table. They are beryllium (Be), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), strontium (Sr), barium (Ba), and radium (Ra).. The elements have very similar p ...

s. Uranium metal can also be prepared through electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses Direct current, direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of c ...

of or

, dissolved in molten calcium chloride () and sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as Salt#Edible salt, edible salt, is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. It is transparent or translucent, brittle, hygroscopic, and occurs a ...

( NaCl) solution. Very pure uranium is produced through the thermal decomposition of uranium halides on a hot filament.

Resources and reserves

It is estimated that 6.1 million tonnes of uranium exists in ores that are economically viable at US$130 per kg of uranium, while 35 million tonnes are classed as mineral resources (reasonable prospects for eventual economic extraction).