Secondary metabolite on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Secondary metabolites, also called ''specialised metabolites'', ''secondary products'', or ''natural products'', are

Secondary metabolites, also called ''specialised metabolites'', ''secondary products'', or ''natural products'', are

The two most commonly known

The two most commonly known  Codeine, also an alkaloid derived from the opium poppy, is considered the most widely used drug in the world according to

Codeine, also an alkaloid derived from the opium poppy, is considered the most widely used drug in the world according to

Selective breeding was used as one of the first biotechnological techniques used to reduce the unwanted secondary metabolites in food, such as naringin causing bitterness in grapefruit. In some cases increasing the content of secondary metabolites in a plant is the desired outcome. Traditionally this was done using in-vitro

Selective breeding was used as one of the first biotechnological techniques used to reduce the unwanted secondary metabolites in food, such as naringin causing bitterness in grapefruit. In some cases increasing the content of secondary metabolites in a plant is the desired outcome. Traditionally this was done using in-vitro

organic compound

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

s produced by any lifeform, e.g. bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

, fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

, animals

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, have myocytes and are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and grow from a ...

, or plants

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with cyanobacteria to produce sugars f ...

, which are not directly involved in the normal growth, development

Development or developing may refer to:

Arts

*Development (music), the process by which thematic material is reshaped

* Photographic development

*Filmmaking, development phase, including finance and budgeting

* Development hell, when a proje ...

, or reproduction

Reproduction (or procreation or breeding) is the biological process by which new individual organisms – "offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. There are two forms of reproduction: Asexual reproduction, asexual and Sexual ...

of the organism. Instead, they generally mediate ecological interactions, which may produce a selective advantage for the organism by increasing its survivability

Survivability is the ability to remain alive or continue to exist. The term has more specific meaning in certain contexts.

Ecological

Following disruptive forces such as flood, fire, disease, war, or climate change some species of flora, faun ...

or fecundity

Fecundity is defined in two ways; in human demography, it is the potential for reproduction of a recorded population as opposed to a sole organism, while in population biology, it is considered similar to fertility, the capability to produc ...

. Specific secondary metabolites are often restricted to a narrow set of species within a phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical dat ...

group. Secondary metabolites often play an important role in plant defense against herbivory

Plant defense against herbivory or host-plant resistance is a range of adaptations Evolution, evolved by plants which improve their fitness (biology), survival and reproduction by reducing the impact of herbivores. Many plants produce secondary ...

and other interspecies defenses. Humans use secondary metabolites as medicines, flavourings, pigments, and recreational drugs.

The term secondary metabolite was first coined by Albrecht Kossel

Ludwig Karl Martin Leonhard Albrecht Kossel (; 16 September 1853 – 5 July 1927) was a biochemist and pioneer in the study of genetics. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1910 for his work in determining the chemical ...

, the 1910 Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

laureate for medicine and physiology. 30 years later a Polish botanist Friedrich Czapek described secondary metabolites as end products of nitrogen metabolism.

Secondary metabolites commonly mediate antagonistic interactions, such as competition

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indi ...

and predation

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

, as well as mutualistic ones such as pollination

Pollination is the transfer of pollen from an anther of a plant to the stigma (botany), stigma of a plant, later enabling fertilisation and the production of seeds. Pollinating agents can be animals such as insects, for example bees, beetles or bu ...

and resource mutualisms. Usually, secondary metabolites are confined to a specific lineage or even species, though there is considerable evidence that horizontal transfer across species or genera of entire pathways plays an important role in bacterial (and, likely, fungal) evolution. Research also shows that secondary metabolism can affect different species in varying ways. In the same forest, four separate species of arboreal marsupial folivores reacted differently to a secondary metabolite in eucalypts. This shows that differing types of secondary metabolites can be the split between two herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically evolved to feed on plants, especially upon vascular tissues such as foliage, fruits or seeds, as the main component of its diet. These more broadly also encompass animals that eat ...

ecological niches. Additionally, certain species evolve to resist secondary metabolites and even use them for their own benefit. For example, monarch butterflies

The monarch butterfly or simply monarch (''Danaus plexippus'') is a milkweed butterfly (subfamily Danainae) in the family Nymphalidae. Other common names, depending on region, include milkweed, common tiger, wanderer, and black-veined brown. ...

have evolved to be able to eat milkweed (''Asclepias'') despite the presence of toxic cardiac glycoside

Cardiac glycosides are a class of organic compounds that increase the output force of the heart and decrease its rate of contractions by inhibiting the cellular sodium-potassium ATPase pump. Their beneficial medical uses include treatments for ...

s. The butterflies are not only resistant to the toxins, but are actually able to benefit by actively sequestering them, which can lead to the deterrence of predators.

Plant secondary metabolites

Plants are capable of producing and synthesizing diverse groups of organic compounds and are divided into two major groups: primary and secondary metabolites. Secondary metabolites are metabolic intermediates or products which are not essential to growth and life of the producing plants but rather required for interaction of plants with their environment and produced in response to stress. Their antibiotic, antifungal and antiviral properties protect the plant from pathogens. Some secondary metabolites such asphenylpropanoid

The phenylpropanoids are a diverse family of organic compounds that are biosynthesized by plants from the amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine in the shikimic acid pathway. Their name is derived from the six-carbon, aromatic phenyl group and ...

s protect plants from UV damage. The biological effects of plant secondary metabolites on humans have been known since ancient times. The herb '' Artemisia annua'' which contains Artemisinin, has been widely used in Chinese traditional medicine more than two thousand years ago. Plant secondary metabolites are classified by their chemical structure and can be divided into four major classes: terpene

Terpenes () are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n ≥ 2. Terpenes are major biosynthetic building blocks. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predomi ...

s, phenylpropanoids (i.e. phenolics), polyketide

In organic chemistry, polyketides are a class of natural products derived from a Precursor (chemistry), precursor molecule consisting of a Polymer backbone, chain of alternating ketone (, or Carbonyl reduction, its reduced forms) and Methylene gro ...

s, and alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

s.

Chemical classes

Terpenoids

Terpene

Terpenes () are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n ≥ 2. Terpenes are major biosynthetic building blocks. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predomi ...

s constitute a large class of natural products which are composed of isoprene

Isoprene, or 2-methyl-1,3-butadiene, is a common volatile organic compound with the formula CH2=C(CH3)−CH=CH2. In its pure form it is a colorless volatile liquid. It is produced by many plants and animals (including humans) and its polymers ar ...

units. Terpene

Terpenes () are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n ≥ 2. Terpenes are major biosynthetic building blocks. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predomi ...

s are only hydrocarbons and terpenoid

The terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, are a class of naturally occurring organic compound, organic chemicals derived from the 5-carbon compound isoprene and its derivatives called terpenes, diterpenes, etc. While sometimes used interchangeabl ...

s are oxygenated hydrocarbons. The general molecular formula of terpenes are multiples of (C5H8)n, where 'n' is number of linked isoprene units. Hence, terpenes are also termed as isoprenoid compounds. Classification is based on the number of isoprene units present in their structure. Some terpenoids (i.e. many sterols

A sterol is any organic compound with a Skeletal formula, skeleton closely related to Cholestanol, cholestan-3-ol. The simplest sterol is gonan-3-ol, which has a formula of , and is derived from that of gonane by replacement of a hydrogen atom on ...

) are primary metabolites. Some terpenoids that may have originated as secondary metabolites have subsequently been recruited as plant hormones, such as gibberellin

Gibberellins (GAs) are plant hormones that regulate various Biological process, developmental processes, including Plant stem, stem elongation, germination, dormancy, flowering, flower development, and leaf and fruit senescence. They are one of th ...

s, brassinosteroid

Brassinosteroids (BRs or less commonly BS) are a class of polyhydroxysteroids that have been recognized as a sixth class of

plant hormones and may have utility as anticancer drugs for treating endocrine-responsive cancers by inducing apoptosis of ...

s, and strigolactones.

Examples of terpenoid

The terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, are a class of naturally occurring organic compound, organic chemicals derived from the 5-carbon compound isoprene and its derivatives called terpenes, diterpenes, etc. While sometimes used interchangeabl ...

s built from hemiterpene oligomerization are:

* Azadirachtin, present in '' Azadirachta indica'', the ( Neem tree)

* Artemisinin, present in '' Artemisia annua'', Chinese wormwood

* Tetrahydrocannabinol

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is a cannabinoid found in cannabis. It is the principal psychoactive constituent of ''Cannabis'' and one of at least 113 total cannabinoids identified on the plant. Although the chemical formula for THC (C21H30O2) de ...

, present in ''Cannabis sativa

''Cannabis sativa'' is an annual Herbaceous plant, herbaceous flowering plant. The species was first classified by Carl Linnaeus in 1753. The specific epithet ''Sativum, sativa'' means 'cultivated'. Indigenous to East Asia, Eastern Asia, the pla ...

'', cannabis

''Cannabis'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae that is widely accepted as being indigenous to and originating from the continent of Asia. However, the number of species is disputed, with as many as three species be ...

* Saponin

Saponins (Latin ''sapon'', 'soap' + ''-in'', 'one of') are bitter-tasting, usually toxic plant-derived secondary metabolites. They are organic chemicals that become foamy when agitated in water and have high molecular weight. They are present ...

s, glycosylated triterpenes present in e.g. '' Chenopodium quinoa'', quinoa

Quinoa (''Chenopodium quinoa''; , from Quechuan languages, Quechua ' or ') is a flowering plant in the Amaranthaceae, amaranth family. It is a herbaceous annual plant grown as a crop primarily for its edible seeds; the seeds are high in prote ...

.

Phenolic compounds

Phenolics are a chemical compound characterized by the presence of aromatic ring structure bearing one or more hydroxyl groups. Phenolics are the most abundant secondary metabolites of plants ranging from simple molecules such asphenolic acid

Phenolic acids or phenolcarboxylic acids ? are phenolic compounds and types of aromatic acid compounds. Included in that class are substances containing a phenolic ring and an organic carboxylic acid function (C6-C1 skeleton). Two important nat ...

to highly polymerized substances such as tannin

Tannins (or tannoids) are a class of astringent, polyphenolic biomolecules that bind to and Precipitation (chemistry), precipitate proteins and various other organic compounds including amino acids and alkaloids. The term ''tannin'' is widel ...

s. Classes of phenolics have been characterized on the basis of their basic skeleton.

An example of a plant phenol is:

* Resveratrol

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-''trans''-stilbene) is a stilbenoid, a type of natural phenol or polyphenol and a phytoalexin produced by several plants in response to injury or when the plant is under attack by pathogens, such as bacterium, ba ...

, a C14 stilbenoid

Stilbenoids are hydroxylated derivatives of stilbene. They have a C6–C2–C6 structure. In biochemical terms, they belong to the family of phenylpropanoids and share most of their biosynthesis pathway with Chalconoid, chalcones. Most stilbenoids ...

produced by e.g. grape

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non- climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of grapes began approximately 8,0 ...

s.

Alkaloids

Alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

s are a diverse group of nitrogen-containing basic compounds. They are typically derived from plant sources and contain one or more nitrogen atoms. Chemically they are very heterogeneous. Based on chemical structures, they may be classified into two broad categories:

* Non heterocyclic or atypical alkaloids, for example hordenine or ''N''-methyltyramine, colchicine

Colchicine is a medication used to prevent and treat gout, to treat familial Mediterranean fever and Behçet's disease, and to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction. The American College of Rheumatology recommends colchicine, nonstero ...

, and taxol

Paclitaxel, sold under the brand name Taxol among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat ovarian cancer, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, Kaposi's sarcoma, cervical cancer, and pancreatic cancer. It is administered by ...

* Heterocyclic or typical alkaloids, for example quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

, caffeine

Caffeine is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant of the methylxanthine chemical classification, class and is the most commonly consumed Psychoactive drug, psychoactive substance globally. It is mainly used for its eugeroic (wakefulness pr ...

, and nicotine

Nicotine is a natural product, naturally produced alkaloid in the nightshade family of plants (most predominantly in tobacco and ''Duboisia hopwoodii'') and is widely used recreational drug use, recreationally as a stimulant and anxiolytic. As ...

Examples of alkaloids produced by plants are:

* Hyoscyamine

Hyoscyamine (also known as daturine or duboisine) is a naturally occurring tropane alkaloid and plant toxin. It is a secondary metabolite found in certain plants of the family Solanaceae, including Hyoscyamus niger, henbane, Mandragora officina ...

, present in '' Datura stramonium''

* Atropine

Atropine is a tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic medication used to treat certain types of nerve agent and pesticide poisonings as well as some types of slow heart rate, and to decrease saliva production during surgery. It is typically give ...

, present in ''Atropa belladonna'', deadly nightshade

* Cocaine

Cocaine is a tropane alkaloid and central nervous system stimulant, derived primarily from the leaves of two South American coca plants, ''Erythroxylum coca'' and ''Erythroxylum novogranatense, E. novogranatense'', which are cultivated a ...

, present in ''Erythroxylum coca'' the Coca

Coca is any of the four cultivated plants in the family Erythroxylaceae, native to western South America. Coca is known worldwide for its psychoactive alkaloid, cocaine. Coca leaves contain cocaine which acts as a mild stimulant when chewed or ...

plant

* Scopolamine, present in the ''Solanaceae'' (nightshade) plant family

* Codeine

Codeine is an opiate and prodrug of morphine mainly used to treat pain, coughing, and diarrhea. It is also commonly used as a recreational drug. It is found naturally in the sap of the opium poppy, ''Papaver somniferum''. It is typically use ...

and morphine

Morphine, formerly also called morphia, is an opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin produced by drying the latex of opium poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as an analgesic (pain medication). There are ...

, present in ''Papaver somniferum'', the opium poppy

* Vincristine

Vincristine, also known as leurocristine and sold under the brand name Oncovin among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat a number of types of cancer. This includes acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, Hodgkin lym ...

and vinblastine

Vinblastine, sold under the brand name Velban among others, is a chemotherapy medication, typically used with other medications, to treat a number of types of cancer. This includes Hodgkin's lymphoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, bladder canc ...

, mitotic inhibitors found in ''Catharanthus roseus'', the rosy periwinkle

Many alkaloids affect the central nervous system of animals by binding to neurotransmitter receptors.

Glucosinolates

Glucosinolate

Glucosinolates are natural components of many pungent plants such as mustard, cabbage, and horseradish. The pungency of those plants is due to mustard oils produced from glucosinolates when the plant material is chewed, cut, or otherwise damaged. ...

s are secondary metabolites that include both sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

and nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

s, and are derived from glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

, an amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

and sulfate

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salts of sulfuric acid and many ...

.

An example of a glucosinolate in plants is Glucoraphanin, from broccoli

Broccoli (''Brassica oleracea'' var. ''italica'') is an edible green plant in the Brassicaceae, cabbage family (family Brassicaceae, genus ''Brassica'') whose large Pseudanthium, flowering head, plant stem, stalk and small associated leafy gre ...

(''Brassica oleracea'' var. ''italica'').

Plant secondary metabolites in medicine

Many drugs used in modern medicine are derived from plant secondary metabolites. The two most commonly known

The two most commonly known terpenoid

The terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, are a class of naturally occurring organic compound, organic chemicals derived from the 5-carbon compound isoprene and its derivatives called terpenes, diterpenes, etc. While sometimes used interchangeabl ...

s are artemisinin and paclitaxel

Paclitaxel, sold under the brand name Taxol among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat ovarian cancer, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, Kaposi's sarcoma, cervical cancer, and pancreatic cancer. It is administered b ...

. Artemisinin was widely used in Traditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is an alternative medicine, alternative medical practice drawn from traditional medicine in China. A large share of its claims are pseudoscientific, with the majority of treatments having no robust evidence ...

and later rediscovered as a powerful antimalarial by a Chinese scientist Tu Youyou. She was later awarded the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

for the discovery in 2015. Currently, the malaria parasite, ''Plasmodium falciparum

''Plasmodium falciparum'' is a Unicellular organism, unicellular protozoan parasite of humans and is the deadliest species of ''Plasmodium'' that causes malaria in humans. The parasite is transmitted through the bite of a female ''Anopheles'' mos ...

'', has become resistant to artemisinin alone and the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

recommends its use with other antimalarial drugs for a successful therapy. Paclitaxel

Paclitaxel, sold under the brand name Taxol among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat ovarian cancer, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, Kaposi's sarcoma, cervical cancer, and pancreatic cancer. It is administered b ...

the active compound found in Taxol is a chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated chemo, sometimes CTX and CTx) is the type of cancer treatment that uses one or more anti-cancer drugs (list of chemotherapeutic agents, chemotherapeutic agents or alkylating agents) in a standard chemotherapy re ...

drug used to treat many forms of cancers including ovarian cancer, breast cancer

Breast cancer is a cancer that develops from breast tissue. Signs of breast cancer may include a Breast lump, lump in the breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, Milk-rejection sign, milk rejection, fluid coming from the nipp ...

, lung cancer

Lung cancer, also known as lung carcinoma, is a malignant tumor that begins in the lung. Lung cancer is caused by genetic damage to the DNA of cells in the airways, often caused by cigarette smoking or inhaling damaging chemicals. Damaged ...

, Kaposi sarcoma, cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is a cancer arising from the cervix or in any layer of the wall of the cervix. It is due to the abnormal growth of cells that can invade or spread to other parts of the body. Early on, typically no symptoms are seen. Later sympt ...

, and pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer arises when cell (biology), cells in the pancreas, a glandular organ behind the stomach, begin to multiply out of control and form a Neoplasm, mass. These cancerous cells have the malignant, ability to invade other parts of ...

. Taxol was first isolated in 1973 from barks of a coniferous tree, the Pacific Yew.

Morphine

Morphine, formerly also called morphia, is an opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin produced by drying the latex of opium poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as an analgesic (pain medication). There are ...

and codeine

Codeine is an opiate and prodrug of morphine mainly used to treat pain, coughing, and diarrhea. It is also commonly used as a recreational drug. It is found naturally in the sap of the opium poppy, ''Papaver somniferum''. It is typically use ...

both belong to the class of alkaloids and are derived from opium poppies

''Papaver somniferum'', commonly known as the opium poppy or breadseed poppy, is a species of flowering plant in the family Papaveraceae. It is the species of plant from which both opium and poppy seeds are derived and is also a valuable orname ...

. Morphine was discovered in 1804 by a German pharmacist Friedrich Sertürneranalgesic

An analgesic drug, also called simply an analgesic, antalgic, pain reliever, or painkiller, is any member of the group of drugs used for pain management. Analgesics are conceptually distinct from anesthetics, which temporarily reduce, and in s ...

effects, however, morphine is also used to treat shortness of breath and treatment of addiction to stronger opiates such as heroin

Heroin, also known as diacetylmorphine and diamorphine among other names, is a morphinan opioid substance synthesized from the Opium, dried latex of the Papaver somniferum, opium poppy; it is mainly used as a recreational drug for its eupho ...

. Despite its positive effects on humans, morphine has very strong adverse effects, such as addiction, hormone imbalance or constipation. Due to its highly addictive nature morphine is a strictly controlled substance around the world, used only in very severe cases with some countries underusing it compared to the global average due to the social stigma around it.

Codeine, also an alkaloid derived from the opium poppy, is considered the most widely used drug in the world according to

Codeine, also an alkaloid derived from the opium poppy, is considered the most widely used drug in the world according to World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

. It was first isolated in 1832 by a French chemist Pierre Jean Robiquet, also known for the discovery of caffeine

Caffeine is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant of the methylxanthine chemical classification, class and is the most commonly consumed Psychoactive drug, psychoactive substance globally. It is mainly used for its eugeroic (wakefulness pr ...

and a widely used red dye alizarin

Alizarin (also known as 1,2-dihydroxyanthraquinone, Mordant Red 11, C.I. 58000, and Turkey Red) is an organic compound with formula that has been used throughout history as a red dye, principally for dyeing textile fabrics. Historically it wa ...

. Primarily codeine is used to treat mild pain and relief coughing although in some cases it is used to treat diarrhea

Diarrhea (American English), also spelled diarrhoea or diarrhœa (British English), is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements in a day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration d ...

and some forms of irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by a group of symptoms that commonly include abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, and changes in the consistency of bowel movements. These symptoms may ...

. Codeine has the strength of 0.1-0.15 compared to morphine ingested orally, hence it is much safer to use. Although codeine can be extracted from the opium poppy, the process is not feasible economically due to the low abundance of pure codeine in the plant. A chemical process of methylation

Methylation, in the chemistry, chemical sciences, is the addition of a methyl group on a substrate (chemistry), substrate, or the substitution of an atom (or group) by a methyl group. Methylation is a form of alkylation, with a methyl group replac ...

of the much more abundant morphine is the main method of production.

Atropine

Atropine is a tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic medication used to treat certain types of nerve agent and pesticide poisonings as well as some types of slow heart rate, and to decrease saliva production during surgery. It is typically give ...

is an alkaloid first found in ''Atropa belladonna

''Atropa bella-donna'', commonly known as deadly nightshade or belladonna, is a toxic perennial herbaceous plant in the nightshade family Solanaceae, which also includes tomatoes, potatoes and eggplant. It is native to Europe and Western Asia, i ...

'', a member of the nightshade family

Solanaceae (), commonly known as the nightshades, is a family of flowering plants in the order Solanales. It contains approximately 2,700 species, several of which are used as agricultural crops, medicinal plants, and ornamental plants. Many me ...

. While atropine was first isolated in the 19th century, its medical use dates back to at least the fourth century B.C. where it was used for wounds, gout, and sleeplessness. Currently atropine is administered intravenously to treat bradycardia

Bradycardia, also called bradyarrhythmia, is a resting heart rate under 60 beats per minute (BPM). While bradycardia can result from various pathological processes, it is commonly a physiological response to cardiovascular conditioning or due ...

and as an antidote to organophosphate poisoning. Overdosing of atropine may lead to atropine poisoning which results in side effects such as blurred vision

Blurred vision is an ocular symptom where vision becomes less precise and there is added difficulty to resolve fine details.

Temporary blurred vision may involve dry eyes, eye infections, alcohol poisoning, hypoglycemia, or low blood pressur ...

, nausea

Nausea is a diffuse sensation of unease and discomfort, sometimes perceived as an urge to vomit. It can be a debilitating symptom if prolonged and has been described as placing discomfort on the chest, abdomen, or back of the throat.

Over 30 d ...

, lack of sweating, dry mouth and tachycardia

Tachycardia, also called tachyarrhythmia, is a heart rate that exceeds the normal resting rate. In general, a resting heart rate over 100 beats per minute is accepted as tachycardia in adults. Heart rates above the resting rate may be normal ...

.

Resveratrol

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-''trans''-stilbene) is a stilbenoid, a type of natural phenol or polyphenol and a phytoalexin produced by several plants in response to injury or when the plant is under attack by pathogens, such as bacterium, ba ...

is a phenolic compound of the flavonoid class. It is highly abundant in grape

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non- climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of grapes began approximately 8,0 ...

s, blueberries

Blueberries are a widely distributed and widespread group of perennial flowering plants with blue or purple berries. They are classified in the section ''Cyanococcus'' with the genus ''Vaccinium''. Commercial blueberries—both wild (lowbush) ...

, raspberries and peanut

The peanut (''Arachis hypogaea''), also known as the groundnut, goober (US), goober pea, pindar (US) or monkey nut (UK), is a legume crop grown mainly for its edible seeds. It is widely grown in the tropics and subtropics by small and large ...

s. It is commonly taken as a dietary supplement for extending life and reducing the risk of cancer and heart disease, however there is no strong evidence supporting its efficacy. Nevertheless, flavonoids are in general thought to have beneficial effects for humans. Certain studies shown that flavonoids have direct antibiotic activity. A number of in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning ''in glass'', or ''in the glass'') Research, studies are performed with Cell (biology), cells or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in ...

and limited in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, an ...

studies shown that flavonoids such as quercetin

Quercetin is a plant flavonol from the flavonoid group of polyphenols. It is found in many fruits, vegetables, leaves, seeds, and grains; capers, red onions, and kale are common foods containing appreciable amounts of it. It has a bitter flavor ...

have synergistic activity with antibiotics and are able to suppress bacterial loads.

Digoxin

Digoxin (better known as digitalis), sold under the brand name Lanoxin among others, is a medication used to treat various heart disease, heart conditions. Most frequently it is used for atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and heart failure. ...

is a cardiac glycoside first derived by William Withering in 1785 from the foxglove ''(Digitalis)'' plant. It is typically used to treat heart conditions such as atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF, AFib or A-fib) is an Heart arrhythmia, abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia) characterized by fibrillation, rapid and irregular beating of the Atrium (heart), atrial chambers of the heart. It often begins as short periods ...

, atrial flutter

Atrial flutter (AFL) is a common abnormal heart rhythm that starts in the atrial chambers of the heart. When it first occurs, it is usually associated with a fast heart rate and is classified as a type of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). ...

or heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome caused by an impairment in the heart's ability to Cardiac cycle, fill with and pump blood.

Although symptoms vary based on which side of the heart is affected, HF ...

. Digoxin can, however, have side effects such as nausea

Nausea is a diffuse sensation of unease and discomfort, sometimes perceived as an urge to vomit. It can be a debilitating symptom if prolonged and has been described as placing discomfort on the chest, abdomen, or back of the throat.

Over 30 d ...

, bradycardia

Bradycardia, also called bradyarrhythmia, is a resting heart rate under 60 beats per minute (BPM). While bradycardia can result from various pathological processes, it is commonly a physiological response to cardiovascular conditioning or due ...

, diarrhea

Diarrhea (American English), also spelled diarrhoea or diarrhœa (British English), is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements in a day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration d ...

or even life-threatening arrhythmia

Arrhythmias, also known as cardiac arrhythmias, are irregularities in the cardiac cycle, heartbeat, including when it is too fast or too slow. Essentially, this is anything but normal sinus rhythm. A resting heart rate that is too fast – ab ...

.

Fungal secondary metabolites

The three main classes of fungal secondary metabolites are: polyketides,nonribosomal peptide

Nonribosomal peptides (NRP) are a class of peptide secondary metabolites, usually produced by microorganisms like bacterium, bacteria and fungi. Nonribosomal peptides are also found in higher organisms, such as nudibranchs, but are thought to be ma ...

s and terpene

Terpenes () are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n ≥ 2. Terpenes are major biosynthetic building blocks. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predomi ...

s. Although fungal secondary metabolites are not required for growth they play an essential role in survival of fungi in their ecological niche. The most known fungal secondary metabolite is penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of beta-lactam antibiotic, β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' Mold (fungus), moulds, principally ''Penicillium chrysogenum, P. chrysogenum'' and ''Penicillium rubens, P. ru ...

discovered by Alexander Fleming

Sir Alexander Fleming (6 August 1881 – 11 March 1955) was a Scottish physician and microbiologist, best known for discovering the world's first broadly effective antibiotic substance, which he named penicillin. His discovery in 1928 of wha ...

in 1928. Later in 1945, Fleming, alongside Ernst Chain

Sir Ernst Boris Chain (19 June 1906 – 12 August 1979) was a German-born British biochemist and co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on penicillin.

Life and career

Chain was born in Berlin, the son of Marg ...

and Howard Florey

Howard Walter Florey, Baron Florey, (; 24 September 1898 – 21 February 1968) was an Australian pharmacologist and pathologist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Ernst Chain and Sir Alexander Fleming for his ro ...

, received a Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

for its discovery which was pivotal in reducing the number of deaths in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

by over 100,000.

Examples of other fungal secondary metabolites are:

* Lovastatin

Lovastatin, sold under the brand name Mevacor among others, is a statin medication, to treat high blood cholesterol and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. Its use is recommended together with lifestyle changes. It is taken by mouth.

...

, a polyketide

In organic chemistry, polyketides are a class of natural products derived from a Precursor (chemistry), precursor molecule consisting of a Polymer backbone, chain of alternating ketone (, or Carbonyl reduction, its reduced forms) and Methylene gro ...

from e.g. ''Pleurotus ostreatus

''Pleurotus ostreatus'' (commonly known the oyster mushroom, grey oyster mushroom, oyster fungus, hiratake, or pearl oyster mushroom). Found in temperate and subtropical forests around the world, it is a popular edible mushroom.

Name

Both th ...

'', oyster mushroom

''Pleurotus'' is a genus of Gill (mushroom), gilled mushrooms which includes one of the most widely eaten mushrooms, ''Pleurotus ostreatus, P. ostreatus''. Species of ''Pleurotus'' may be called oyster, abalone, or tree mushrooms, and are ...

s.

* Aflatoxin B1, a polyketide

In organic chemistry, polyketides are a class of natural products derived from a Precursor (chemistry), precursor molecule consisting of a Polymer backbone, chain of alternating ketone (, or Carbonyl reduction, its reduced forms) and Methylene gro ...

from ''Aspergillus flavus

''Aspergillus flavus'' is a saprotrophic and pathogenic fungus with a cosmopolitan distribution. It is best known for its colonization of cereal grains, legumes, and tree nuts. Postharvest rot typically develops during harvest, storage, and/or ...

''.

* Ciclosporin

Ciclosporin, also spelled cyclosporine and cyclosporin, is a calcineurin inhibitor, used as an immunosuppressant medication. It is taken Oral administration, orally or intravenously for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, Crohn's disease, nephr ...

, a non-ribosomal cyclic peptide

Peptides are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. A polypeptide is a longer, continuous, unbranched peptide chain. Polypeptides that have a molecular mass of 10,000 Da or more are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty am ...

from '' Tolypocladium inflatum''.

Lovastatin

Lovastatin, sold under the brand name Mevacor among others, is a statin medication, to treat high blood cholesterol and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. Its use is recommended together with lifestyle changes. It is taken by mouth.

...

was the first FDA approved secondary metabolite to lower cholesterol levels. Lovastatin occurs naturally in low concentrations in oyster mushrooms, red yeast rice, and Pu-erh. Lovastatin's mode of action

In pharmacology and biochemistry, mode of action (MoA) describes a functional or anatomical change, resulting from the exposure of a living organism to a substance. In comparison, a mechanism of action (MOA) describes such changes at the molecul ...

is competitive inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase

HMG-CoA reductase (3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, official symbol HMGCR) is the rate-limiting enzyme (NADH-dependent, ; NADPH-dependent, ) of the mevalonate pathway, the metabolic pathway that produces cholesterol and other ...

, and a rate-limiting enzyme responsible for converting HMG-CoA to mevalonate.

Fungal secondary metabolites can also be dangerous to humans. '' Claviceps purpurea'', a member of the ergot

Ergot ( ) or ergot fungi refers to a group of fungi of the genus ''Claviceps''.

The most prominent member of this group is '' Claviceps purpurea'' ("rye ergot fungus"). This fungus grows on rye and related plants, and produces alkaloids that c ...

group of fungi typically growing on rye, results in death when ingested. The build-up of poisonous alkaloids found in ''C. purpurea'' lead to symptoms such as seizures and spasm

A spasm is a sudden involuntary contraction of a muscle, a group of muscles, or a hollow organ, such as the bladder.

A spasmodic muscle contraction may be caused by many medical conditions, including dystonia. Most commonly, it is a musc ...

s, diarrhea

Diarrhea (American English), also spelled diarrhoea or diarrhœa (British English), is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements in a day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration d ...

, paresthesia

Paresthesia is a sensation of the skin that may feel like numbness (''hypoesthesia''), tingling, pricking, chilling, or burning. It can be temporary or Chronic condition, chronic and has many possible underlying causes. Paresthesia is usually p ...

s, Itching, psychosis

In psychopathology, psychosis is a condition in which a person is unable to distinguish, in their experience of life, between what is and is not real. Examples of psychotic symptoms are delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized or inco ...

or gangrene

Gangrene is a type of tissue death caused by a lack of blood supply. Symptoms may include a change in skin color to red or black, numbness, swelling, pain, skin breakdown, and coolness. The feet and hands are most commonly affected. If the ga ...

. Currently, removal of ergot bodies requires putting the rye in brine solution with healthy grains sinking and infected floating.

Bacterial secondary metabolites

Bacterial production of secondary metabolites starts in the stationary phase as a consequence of lack of nutrients or in response to environmental stress. Secondary metabolite synthesis in bacteria is not essential for their growth, however, they allow them to better interact with their ecological niche. The main synthetic pathways of secondary metabolite production in bacteria are; b-lactam, oligosaccharide, shikimate, polyketide and non-ribosomal pathways. Many bacterial secondary metabolites are toxic tomammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s. When secreted those poisonous compounds are known as exotoxins whereas those found in the prokaryotic cell wall are endotoxins.

Examples of bacterial secondary metabolites are:

Phenazine

* Pyocyanin, from ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common Bacterial capsule, encapsulated, Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-negative, Aerobic organism, aerobic–facultative anaerobe, facultatively anaerobic, Bacillus (shape), rod-shaped bacteria, bacterium that can c ...

''.

* Other phenazine

Phenazine is an organic compound with the formula (C6H4)2N2. It is a dibenzo annulation, annulated pyrazine, and the parent substance of many dyestuffs, such as the toluylene red, indulines, and safranines (and the closely related eurhodines). Phe ...

s from ''Pseudomonas

''Pseudomonas'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria belonging to the family Pseudomonadaceae in the class Gammaproteobacteria. The 348 members of the genus demonstrate a great deal of metabolic diversity and consequently are able to colonize a ...

'' ssp. and '' Streptomyces'' ssp.

Polyketides

* Avermectin, from '' Streptomyces avermitilis''. * Epothilones, macrolactones from the soil-dwelling myxobacterium '' Sorangium cellulosum''. *Erythromycin

Erythromycin is an antibiotic used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. This includes respiratory tract infections, skin infections, chlamydia infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, and syphilis. It may also be used ...

, '' Saccharopolyspora erythraea''.

* Nystatin

Nystatin, sold under the brand name Mycostatin among others, is an antifungal medication. It is used to treat ''Candida (fungus), Candida'' infections of the skin including diaper rash, Candidiasis, thrush, esophageal candidiasis, and vaginal ...

, from '' Streptomyces noursei''.

* Rifamycin, from '' Amycolatopsis rifamycinica''.

Nonribosomal peptides

*Bacitracin

Bacitracin is a polypeptide antibiotic. It is a mixture of related cyclic peptides produced by '' Bacillus licheniformis'' bacteria, that was first isolated from the variety "Tracy I" ( ATCC 10716) in 1945. These peptides disrupt Gram-positiv ...

, from ''Bacillus subtilis

''Bacillus subtilis'' (), known also as the hay bacillus or grass bacillus, is a gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium, found in soil and the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants, humans and marine sponges. As a member of the genus ''Bacill ...

'' (Tracy strain).

* Gramicidin, from ''Brevibacillus brevis

''Brevibacillus brevis'' (formerly known as ''Bacillus brevis'') is a Gram-positive

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bact ...

''.

* Polymyxin, from '' Paenibacillus polymyxa''.

* Ramoplanin, from '' Actinoplanes'' strain ATCC 33076.

* Teicoplanins, from '' Actinoplanes teicomyceticus''.

* Vancomycin

Vancomycin is a glycopeptide antibiotic medication used to treat certain bacterial infections. It is administered intravenously ( injection into a vein) to treat complicated skin infections, bloodstream infections, endocarditis, bone an ...

, from the soil bacterium '' Amycolatopsis orientalis''.

Ribosomal peptides

*Microcin

Microcins are very small bacteriocins, composed of relatively few amino acids. For this reason, they are distinct from their larger protein cousins. The classic example is microcin V, of ''Escherichia coli''. Subtilosin A is another bacterioci ...

s, bacteriocin

Bacteriocins are proteinaceous or peptide, peptidic toxins produced by bacteria to inhibit the growth of similar or closely related bacterial strain(s). They are similar to yeast and paramecium killing factors, and are structurally, functionally ...

s such as microcin V from ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Escherichia'' that is commonly fo ...

''.

* Thiostrepton, from several strains of streptomycetes, e.g. '' Streptomyces azureus''.

Glucosides

* Nojirimycin, an iminosugar from a class of '' Streptomyces'' species.Alkaloids

*Tetrodotoxin

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is a potent neurotoxin. Its name derives from Tetraodontiformes, an Order (biology), order that includes Tetraodontidae, pufferfish, porcupinefish, ocean sunfish, and triggerfish; several of these species carry the toxin. Alt ...

, a neurotoxin

Neurotoxins are toxins that are destructive to nervous tissue, nerve tissue (causing neurotoxicity). Neurotoxins are an extensive class of exogenous chemical neurological insult (medical), insultsSpencer 2000 that can adversely affect function ...

produced by '' Pseudoalteromonas'' and other bacteria living in symbiosis with animals such as e.g. pufferfish

Tetraodontidae is a family of marine and freshwater fish in the order Tetraodontiformes. The family includes many familiar species variously called pufferfish, puffers, balloonfish, blowfish, blowers, blowies, bubblefish, globefish, swellfis ...

.

Terpenoids

*Carotenoids

Carotenoids () are yellow, orange, and red organic compound, organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, archaea, and Fungus, fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips ...

, a pigment produced by different species of bacteria, such as ''Micrococcus'' sp.

* Strepsesquitriol, compound produced by ''Streptomyces sp.'' that can reduce inflammation without being toxic to cells, making a promising candidate for developing anti-inflammatory medicines.

* Micromonohalimane B., a diterpene

Diterpenes are a class of terpenes composed of four isoprene units, often with the molecular formula C20H32. They are biosynthesized by plants, animals and fungi via the HMG-CoA reductase pathway, with geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate being a primary ...

identified from ''Micromonospora sp.'', shows moderate antibacterial activity against some antibiotic resistant Gram-positive bacteria.

* Cyclomarins, a potent anti-inflammatory and antiviral compound produced by a marine ''Streptomyces,'' with strong cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines and also effective against herpesviruses.

Archaea secondary metabolites

Archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

are capable of producing a variety of secondary metabolites, which may have significant biotechnological applications. Despite knowing this, the biosynthetic pathways for secondary metabolites in archaea are less understood than those in bacteria. Notably, archaea often lack some biosynthesis genes commonly present in bacteria, which suggests that they may possess unique metabolic pathways for synthetizing these compounds.

Extracellular polymeric substances

Extracellular polymeric substances can effectively adsorb and degrade hazardous organic chemicals. While these compounds are produced by various organisms, archaea are particularly promising for wastewater treatment due to their high tolerance to saline concentrations and their ability to grow anaerobically.Biotechnological approaches

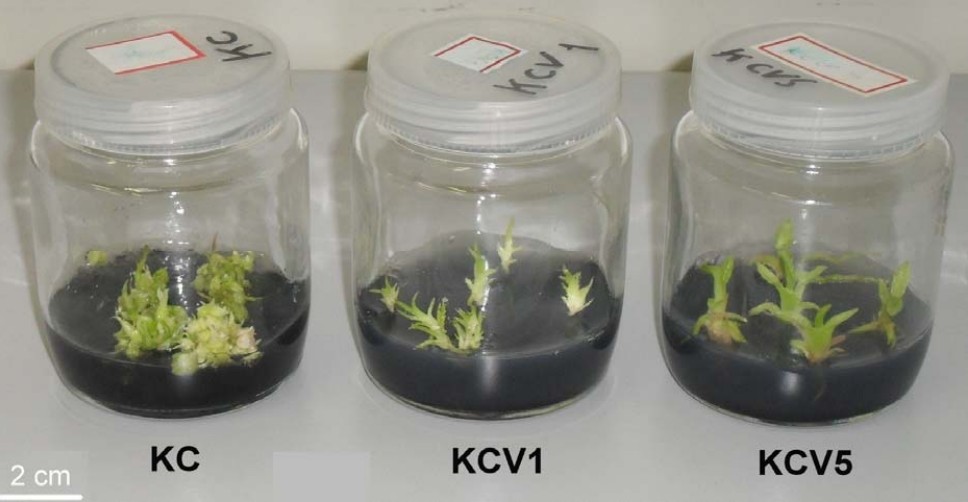

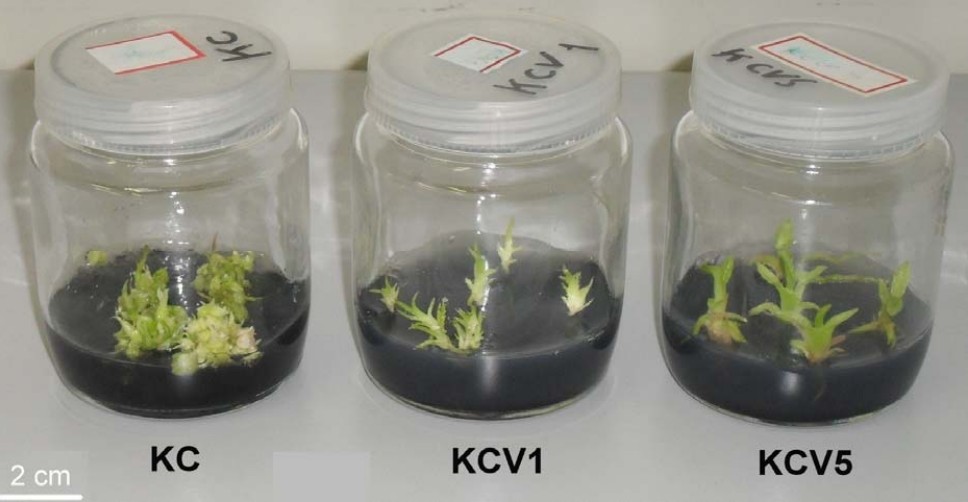

Selective breeding was used as one of the first biotechnological techniques used to reduce the unwanted secondary metabolites in food, such as naringin causing bitterness in grapefruit. In some cases increasing the content of secondary metabolites in a plant is the desired outcome. Traditionally this was done using in-vitro

Selective breeding was used as one of the first biotechnological techniques used to reduce the unwanted secondary metabolites in food, such as naringin causing bitterness in grapefruit. In some cases increasing the content of secondary metabolites in a plant is the desired outcome. Traditionally this was done using in-vitro plant tissue culture

Plant tissue culture is a collection of techniques used to maintain or grow plant cells, tissues, or organs under sterile conditions on a nutrient culture medium of known composition. It is widely used to produce clones of a plant in a method know ...

techniques which allow for: control of growth conditions, mitigate seasonality of plants or protect them from parasites and harmful-microbes. Synthesis of secondary metabolites can be further enhanced by introducing elicitors into a tissue plant culture, such as jasmonic acid, UV-B or ozone

Ozone () (or trioxygen) is an Inorganic compound, inorganic molecule with the chemical formula . It is a pale blue gas with a distinctively pungent smell. It is an allotrope of oxygen that is much less stable than the diatomic allotrope , break ...

. These compounds induce stress onto a plant leading to increased production of secondary metabolites.

To further increase the yield of SMs new approaches have been developed. A novel approach used by Evolva uses recombinant yeast S. cerevisiae strains to produce secondary metabolites normally found in plants. The first successful chemical compound synthesised with Evolva was vanillin, widely used in the food beverage industry as flavouring. The process involves inserting the desired secondary metabolite gene into an artificial chromosome in the recombinant yeast leading to synthesis of vanillin. Currently Evolva produces a wide array of chemicals such as stevia

Stevia () is a sweet sugar substitute that is about 50 to 300 times sweetness, sweeter than sugar. It is extracted from the leaves of ''Stevia rebaudiana'', a plant native to areas of Paraguay and Brazil. The active compounds in stevia are ...

, resveratrol

Resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxy-''trans''-stilbene) is a stilbenoid, a type of natural phenol or polyphenol and a phytoalexin produced by several plants in response to injury or when the plant is under attack by pathogens, such as bacterium, ba ...

or nootkatone.

Nagoya protocol

With the development of recombinant technologies the ''Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to theConvention on Biological Diversity

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), known informally as the Biodiversity Convention, is a multilateral treaty. The Convention has three main goals: the conservation of biological diversity (or biodiversity); the sustainable use of its ...

'' was signed in 2010. The protocol regulates the conservation and protection of genetic resources

Genetic resources are genetic material of actual or potential value, where genetic material means any material of plant, animal, microbial genetics, microbial or other origin containing functional units of heredity.

Genetic resources is one of the ...

to prevent the exploitation of smaller and poorer countries. If genetic, protein or small molecule resources sourced from biodiverse countries become profitable a compensation scheme was put in place for the countries of origin.

See also

*Chemical ecology

A chemical substance is a unique form of matter with constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Chemical substances may take the form of a single element or chemical compounds. If two or more chemical substances can be combin ...

* Hairy root culture, a strategy used in plant tissue culture to produce commercially viable quantities of valuable secondary metabolites

* Plant physiology

Plant physiology is a subdiscipline of botany concerned with the functioning, or physiology, of plants.

Plant physiologists study fundamental processes of plants, such as photosynthesis, respiration, plant nutrition, plant hormone functions, tr ...

* Volatile organic compound

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are organic compounds that have a high vapor pressure at room temperature. They are common and exist in a variety of settings and products, not limited to Indoor mold, house mold, Upholstery, upholstered furnitur ...

* Cetoniacytone A

References

External links

* {{Authority control Chemical ecology Ecology Evolutionary biology