George Grey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

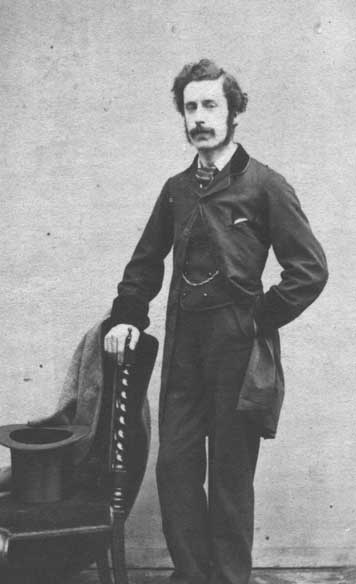

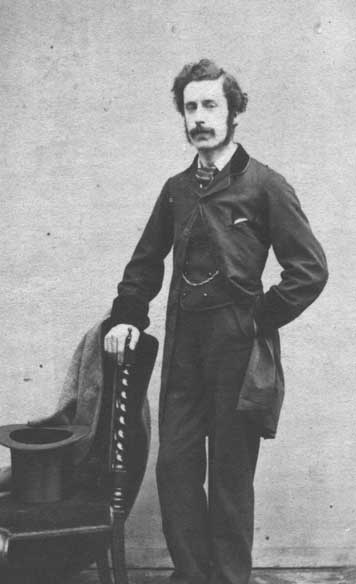

Sir George Grey, KCB (14 April 1812 – 19 September 1898) was a British soldier, explorer, colonial administrator and writer. He served in a succession of governing positions:

In March 1845, Māori chief

In March 1845, Māori chief

Grey was Governor of Cape Colony from 5 December 1854 to 15 August 1861. He founded Grey College, Bloemfontein in 1855 and was the benefactor for Grey High School in Port Elizabeth, founded by John Paterson (Cape politician), John Paterson in 1856. In 1859 he laid the foundation stone of the Somerset Hospital (Cape Town), New Somerset Hospital, Cape Town. When he left the Cape in 1861 he presented the National Library of South Africa with a remarkable personal collection of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts and rare books.

He began his term as governor a few years following the Convict crisis, Convict Crisis of 1849, an event that significantly influenced Cape politics until the establishment of responsible government in 1872. Grey faced a growing rivalry between the eastern and western halves of the Cape Colony, as well as a small, but also growing, movement for local democracy ("responsible government") and greater independence from British rule.

"There were moves for responsible government in the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope, Cape Parliament in 1855 and 1856 but they were defeated by a combination of Western conservatives and Easterners anxious about the defence of the frontier under a responsible system. But undoubtedly Sir George Grey's political ability, charm and force of personality – aided by the parliamentary leadership of liberal-minded Attorney-General, William Porter – contributed to this result."

In South Africa Grey dealt firmly with the natives, endeavouring to "protect" them from white settlement while simultaneously using reservations to coercively demilitarize them, using natives, in his own words, "as real though unavowed hostages for the tranquillity of their kindred and connections." On more than one occasion, Grey acted as arbitrator between the government of the Orange Free State and the natives, eventually drawing the conclusion that a federation, federated South Africa would be a good thing for everyone. The Orange Free State would have been willing to join the federation, and it is probable that the South African Republic, Transvaal would also have agreed. However, Grey was 50 years before his time: the

Grey was Governor of Cape Colony from 5 December 1854 to 15 August 1861. He founded Grey College, Bloemfontein in 1855 and was the benefactor for Grey High School in Port Elizabeth, founded by John Paterson (Cape politician), John Paterson in 1856. In 1859 he laid the foundation stone of the Somerset Hospital (Cape Town), New Somerset Hospital, Cape Town. When he left the Cape in 1861 he presented the National Library of South Africa with a remarkable personal collection of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts and rare books.

He began his term as governor a few years following the Convict crisis, Convict Crisis of 1849, an event that significantly influenced Cape politics until the establishment of responsible government in 1872. Grey faced a growing rivalry between the eastern and western halves of the Cape Colony, as well as a small, but also growing, movement for local democracy ("responsible government") and greater independence from British rule.

"There were moves for responsible government in the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope, Cape Parliament in 1855 and 1856 but they were defeated by a combination of Western conservatives and Easterners anxious about the defence of the frontier under a responsible system. But undoubtedly Sir George Grey's political ability, charm and force of personality – aided by the parliamentary leadership of liberal-minded Attorney-General, William Porter – contributed to this result."

In South Africa Grey dealt firmly with the natives, endeavouring to "protect" them from white settlement while simultaneously using reservations to coercively demilitarize them, using natives, in his own words, "as real though unavowed hostages for the tranquillity of their kindred and connections." On more than one occasion, Grey acted as arbitrator between the government of the Orange Free State and the natives, eventually drawing the conclusion that a federation, federated South Africa would be a good thing for everyone. The Orange Free State would have been willing to join the federation, and it is probable that the South African Republic, Transvaal would also have agreed. However, Grey was 50 years before his time: the

Grey was again appointed governor in 1861, to replace Governor Thomas Gore Browne, serving until 1868. His second term as governor was greatly different from the first, as he had to deal with the demands of an New Zealand Parliament, elected parliament, which had been established in 1852.

Grey was again appointed governor in 1861, to replace Governor Thomas Gore Browne, serving until 1868. His second term as governor was greatly different from the first, as he had to deal with the demands of an New Zealand Parliament, elected parliament, which had been established in 1852.

In 1889, recalling his earlier proposal for the Governor to be elected from his first draft of the 1852 Constitution Act, Grey put forward the Election of Governor Bill, which would have allowed for a "British subject" to be elected to the office of Governor "precisely as an ordinary parliamentary election in each district."

By now Grey was suffering from ill health and he retired from politics in 1890, leaving for Australia to recuperate. While in Australia, he took part in the Constitutional Convention (Australia)#1891 convention, Australian Federal Convention. On returning to New Zealand, a deputation requested him to contest the Newton (New Zealand electorate), Newton seat in Auckland in the 1891 Newton by-election, 1891 by-election. The retiring member, David Goldie (politician), David Goldie, also asked Grey to take his seat. Grey was prepared to put his name forward only if the election was unopposed, as he did not want to suffer the excitement of a contested election. Grey declared his candidacy on 25 March 1891. On 6 April 1891, he was declared elected, as he was unopposed. In December 1893, Grey was again elected, this time to Auckland (New Zealand electorate), Auckland City. He left for England in 1894 and did not return to New Zealand. He resigned his seat in 1895.

In 1889, recalling his earlier proposal for the Governor to be elected from his first draft of the 1852 Constitution Act, Grey put forward the Election of Governor Bill, which would have allowed for a "British subject" to be elected to the office of Governor "precisely as an ordinary parliamentary election in each district."

By now Grey was suffering from ill health and he retired from politics in 1890, leaving for Australia to recuperate. While in Australia, he took part in the Constitutional Convention (Australia)#1891 convention, Australian Federal Convention. On returning to New Zealand, a deputation requested him to contest the Newton (New Zealand electorate), Newton seat in Auckland in the 1891 Newton by-election, 1891 by-election. The retiring member, David Goldie (politician), David Goldie, also asked Grey to take his seat. Grey was prepared to put his name forward only if the election was unopposed, as he did not want to suffer the excitement of a contested election. Grey declared his candidacy on 25 March 1891. On 6 April 1891, he was declared elected, as he was unopposed. In December 1893, Grey was again elected, this time to Auckland (New Zealand electorate), Auckland City. He left for England in 1894 and did not return to New Zealand. He resigned his seat in 1895.

Grey, Sir George (1812–1898)

, ''Australian Dictionary of Biography'', Volume 1, Melbourne University Press, MUP, 1966, pp. 476–80. Retrieved 28 December 2008. * *Polynesian Mythology (book)

Grey Collection, some 14,000 items given to the Auckland Free Public Library in 1887 by Sir George Grey

* * * * *[http://www.teara.govt.nz/1966/G/GreySirGeorge/GreySirGeorge/en "Sir George Grey" in the 1966 ''Encyclopaedia of New Zealand''] *Comments on scope of th

Collection

donated in 1861 by Sir George Grey, to the National Library of South Africa, South African Library containing the earliest South African printed specimen by Johann Christian Ritter and many other manuscripts, incunabula and books.

George Grey entry on AustLit with links to works available in full text.

(subscription required outside Australia)

Sir George Grey: Books and pamphlets

(information about the life of former South Australian Governor George Grey) —State Library of South Australia , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Grey, George 1812 births 1898 deaths Prime ministers of New Zealand 19th-century prime ministers of New Zealand People of the New Zealand Wars Governors of the Cape Colony Ministers of finance of New Zealand Members of the New Zealand House of Representatives Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Burials at St Paul's Cathedral Explorers of Western Australia Explorers of Australia Governors-general of New Zealand Governors of South Australia Governors of the Colony of South Australia Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst People educated at Royal Grammar School, Guildford Independent MPs of New Zealand New Zealand MPs for Auckland electorates Superintendents of New Zealand provincial councils 83rd (County of Dublin) Regiment of Foot officers 19th-century Australian writers 19th-century New Zealand people Kawau Island Members of the New Zealand Legislative Council (1841–1853) Colonial secretaries of New Zealand Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom British book and manuscript collectors British colonial governors and administrators in Oceania Georgist politicians Flagstaff War People associated with the Auckland Art Gallery

Governor of South Australia

The governor of South Australia is the representative in South Australia of the monarch, currently King Charles III. The governor performs the same constitutional and ceremonial functions at the state level as does the governor-general of Aust ...

, twice Governor of New Zealand

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the type of political region or polity, a ''governor'' ma ...

, Governor of Cape Colony

This article lists the governors of British South African colonies, including the colonial prime ministers. It encompasses the period from 1797 to 1910, when present-day South Africa was divided into four British Empire, British colonies namely ...

, and the 11th premier of New Zealand

The prime minister of New Zealand () is the head of government of New Zealand. The prime minister, Christopher Luxon, leader of the New Zealand National Party, took office on 27 November 2023.

The prime minister (informally abbreviated to ...

. He played a key role in the colonisation of New Zealand

The human history of New Zealand can be dated back to between 1320 and 1350 CE, when the main settlement period started, after it was discovered and settled by Polynesians, who developed a distinct Māori culture. Like other Pacific cultures, M ...

, and both the purchase and annexation

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held t ...

of Māori land.

Grey was born in Lisbon, Portugal, just a few days after his father, Lieutenant-Colonel George Grey, was killed at the Battle of Badajoz in Spain. He was educated in England. After military service (1829–37) and two explorations in Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

(1837–39), Grey became Governor of South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

in 1841. He oversaw the colony during a difficult formative period. Despite being less hands-on than his predecessor George Gawler

Colonel George Gawler (21 July 1795 – 7 May 1869) was the second Governor of South Australia, at the same time serving as Resident Commissioner, from 17 October 1838 until 15 May 1841.

Biography Early life

Gawler, born on 21 July 1795, was t ...

, his fiscally responsible measures ensured the colony was in good shape by the time he departed for New Zealand in 1845.G. H. Pitt, "The Crisis of 1841: Its Causes and Consequences" ''South Australiana'' (1972) 11#2 pp 43–81.

Grey was the most influential figure during the European settlement of New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

. Governor of New Zealand initially from 1845 to 1853, he was governor during the initial stages of the New Zealand Wars

The New Zealand Wars () took place from 1845 to 1872 between the Colony of New Zealand, New Zealand colonial government and allied Māori people, Māori on one side, and Māori and Māori-allied settlers on the other. Though the wars were initi ...

. Learning Māori to fluency, he became a scholar of Māori culture

Māori culture () is the customs, cultural practices, and beliefs of the Māori people of New Zealand. It originated from, and is still part of, Polynesians, Eastern Polynesian culture. Māori culture forms a distinctive part of Culture of New ...

, compiling Māori mythology

Māori mythology and Māori traditions are two major categories into which the remote oral history of New Zealand's Māori people, Māori may be divided. Māori myths concern tales of supernatural events relating to the origins of what was the ...

and oral history and publishing it in translation in London. He developed a cordial relationship with the powerful rangatira Pōtatau Te Wherowhero

Pōtatau Te Wherowhero (died 25 June 1860) was a Māori people, Māori rangatira who reigned as the inaugural Māori King Movement, Māori King from 1858 until his death. A powerful nobleman and a leader of the Waikato (iwi), Waikato iwi of the ...

of Tainui

Tainui is a tribal waka (canoe), waka confederation of New Zealand Māori people, Māori iwi. The Tainui confederation comprises four principal related Māori iwi of the central North Island of New Zealand: Hauraki Māori, Hauraki, Ngāti Maniapo ...

, in order to deter Ngāpuhi

Ngāpuhi (also known as Ngāpuhi-Nui-Tonu or Ngā Puhi) is a Māori iwi associated with the Northland regions of New Zealand centred in the Hokianga, the Bay of Islands, and Whangārei.

According to the 2023 New Zealand census, the estimate ...

from invading Auckland

Auckland ( ; ) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. It has an urban population of about It is located in the greater Auckland Region, the area governed by Auckland Council, which includes outlying rural areas and ...

. He was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

in 1848. In 1854, Grey was appointed Governor of Cape Colony in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, where his resolution of hostilities between indigenous South Africans and European settlers was praised by both sides. After separating from his wife and developing a severe opium addiction

Opium (also known as poppy tears, or Lachryma papaveris) is the dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which is ...

, Grey was again appointed Governor of New Zealand in 1861, three years after Te Wherowhero, who had established himself the first Māori King

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

in Grey’s absence, had died. The Kiingitanga (Maori King) posed a significant challenge to the British push for sovereignty, and with his Ngāpuhi absent from the movement, Grey found himself challenged on two sides. He struggled to reuse his skills in negotiation to maintain peace with Māori, and his relationship with Te Wherowhero's successor Tāwhiao

''Kīngitanga, Kīngi'' Tāwhiao (Tūkaroto Matutaera Pōtatau Te Wherowhero Tāwhiao, ; c. 1822 – 26 August 1894), known initially as Matutaera, reigned as the Māori King Movement, Māori King from 1860 until his death. After his flight to ...

deeply soured. Turning on his former allies, Grey began an aggressive crackdown on Tainui and launched the Invasion of the Waikato

The invasion of the Waikato became the largest and most important campaign of the 19th-century New Zealand Wars. Hostilities took place in the North Island of New Zealand between the military forces of the colonial government and a federation ...

in 1863, with 14,000 Imperial and colonial troops attacking 4,000 Māori and their families. Appointed in 1877, he served as Premier of New Zealand until 1879, where he remained a symbol of colonialism.

By political philosophy a Gladstonian liberal

Gladstonian liberalism is a political doctrine named after the British Victorian Prime Minister and Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone. Gladstonian liberalism consisted of limited government expenditure and low taxation whilst making ...

and Georgist

Georgism, in modern times also called Geoism, and known historically as the single tax movement, is an economic ideology holding that people should own the value that they produce themselves, while the economic rent derived from land—includ ...

, Grey eschewed the class system to be part of Auckland's new governance he helped to establish. Cyril Hamshere argues that Grey was a "great British proconsul", although he was also temperamental, demanding of associates, and lacking in some managerial abilities. For the wars of territorial expansion against Māori which he started, he remains a controversial and divisive figure in New Zealand.

Early life

Grey was born inLisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, the only son of Lieutenant-Colonel George Grey, of the 30th (Cambridgeshire) Regiment of Foot

The 30th (Cambridgeshire) Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1702. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 59th (2nd Nottinghamshire) Regiment of Foot to form the East Lancashire Regiment in 1881.

...

, who was killed at the Battle of Badajoz in Spain just a few days before. His mother, Elizabeth Anne , on the balcony of her hotel in Lisbon, overheard two officers speak of her husband's death and this brought on the premature birth of the child. She was the daughter of a retired soldier turned Irish clergyman, Major later Reverend John Vignoles. Grey's grandfather was Owen Wynne Gray ( 1745 – 6 January 1819). Grey's uncle was John Gray, who was Owen Wynne Gray's son from his second marriage.

Grey was sent to the Royal Grammar School, Guildford

The Royal Grammar School, Guildford (originally 'The Free School'), also known as the RGS, is a Private schools in the United Kingdom, private selective day school for boys in Guildford, Surrey in England. The school dates its founding to the de ...

in Surrey, and was admitted to the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC) was a United Kingdom, British military academy for training infantry and cavalry Officer (armed forces), officers of the British Army, British and British Indian Army, Indian Armies. It was founded in 1801 at Gre ...

in 1826. Early in 1830, he was gazetted ensign in the 83rd Regiment of Foot. In 1830, his regiment having been sent to Ireland, he developed much sympathy with the Irish peasantry whose misery made a great impression on him. He was promoted lieutenant in 1833 and obtained a first-class certificate at the examinations of the Royal Military College, in 1836.

Exploration

In 1837, at the age of 25, Grey led an ill-prepared expedition that explored North-West Australia. British settlers in Australia at the time knew little of the region and only one member of Grey's party had been there before. It was believed possible at that time that one of the world's largest rivers might drain into the Indian Ocean in North-West Australia; if that were found to be the case, the region it flowed through might be suitable for colonisation. Grey, with Lieutenant Franklin Lushington, of the9th (East Norfolk) Regiment of Foot

The Royal Norfolk Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army until 1959. Its predecessor regiment was raised in 1685 as Henry Cornwall's Regiment of Foot. In 1751, it was numbered like most other British Army regiments and named ...

, offered to explore the region. On 5 July 1837, they sailed from Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

in command of a party of five, the others being Lushington; Dr William Walker, a surgeon and naturalist; and Corporals John Coles and Richard Auger of the Royal Sappers and Miners

The British Army during the Victorian era served through a period of great technological and social change. Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837, and died in 1901. Her long reign was marked by the steady expansion and consolidation of th ...

. Joining the party at Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

were Sapper Private Robert Mustard, J.C. Cox, Thomas Ruston, Evan Edwards, Henry Williams, and Robert Inglesby. In December they landed at Hanover Bay (west of Uwins Island in the Bonaparte Archipelago

The Bonaparte Archipelago is a group of islands off the coast of Western Australia in the Kimberley region, within the Shire of Wyndham-East Kimberley. The closest inhabited place is Kalumburu located about to the east of the island group. Th ...

). Travelling south, the party traced the course of the Glenelg River. After experiencing boat wrecks, near-drowning, becoming completely lost, and Grey himself being speared in the hip during a skirmish with Aboriginal people

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

, the party gave up. After being picked up by HMS ''Beagle'' and the schooner ''Lynher'', they were taken to Mauritius

Mauritius, officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island country in the Indian Ocean, about off the southeastern coast of East Africa, east of Madagascar. It includes the main island (also called Mauritius), as well as Rodrigues, Ag ...

to recover. Lieutenant Lushington was then mobilised to rejoin his regiment in the First Anglo-Afghan War

The First Anglo-Afghan War () was fought between the British Empire and the Emirate of Kabul from 1838 to 1842. The British initially successfully invaded the country taking sides in a succession dispute between emir Dost Mohammad Khan ( Bara ...

. In September 1838 Grey sailed to Perth hoping to resume his adventures.

In February 1839 Grey embarked on a second exploration expedition to the north, where he was again wrecked with his party, again including Surgeon Walker, at Kalbarri. They were the first Europeans to see the Murchison River, but then had to walk to Perth

Perth () is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth-most-populous city in Australia, with a population of over 2.3 million within Greater Perth . The ...

, surviving the journey through the efforts of Kaiber, a Whadjuk

Whadjuk or Wadjak, alternatively Witjari, are Noongar (Aboriginal Australian) people of the Western Australian region of the Perth bioregion of the Swan Coastal Plain.

Name

The ethnonym appears to derive from , the Whadjuk word for "no".

Count ...

Noongar

The Noongar (, also spelt Noongah, Nyungar , Nyoongar, Nyoongah, Nyungah, Nyugah, and Yunga ) are Aboriginal Australian people who live in the South West, Western Australia, south-west corner of Western Australia, from Geraldton, Western Aus ...

man (that is, indigenous to the Perth region), who organised food and what water could be found (they survived by drinking liquid mud). At about this time, Grey learnt the Noongar language

Noongar (), also Nyungar (), is an Australian Aboriginal languages, Australian Aboriginal language or dialect continuum, spoken by some members of the Noongar community and others. It is taught actively in Australia, including at schools, uni ...

.

Due to his interest in Aboriginal culture in July 1839, Grey was promoted to captain and appointed temporary Resident Magistrate

A resident magistrate is a title for magistrates used in certain parts of the world, that were, or are, governed by the British. Sometimes abbreviated as RM, it refers to suitably qualified personnel—notably well versed in the law—brought int ...

at King George Sound

King George Sound (Mineng ) is a sound (geography), sound on the south coast of Western Australia. Named King George the Third's Sound in 1791, it was referred to as King George's Sound from 1805. The name "King George Sound" gradually came in ...

, Western Australia, following the death of Sir Richard Spencer, the previous Resident Magistrate.

Marriage and children

On 2 November 1839 at King George Sound, Grey marriedEliza Lucy Spencer

Eliza Lucy Grey, Lady Grey (; 17 December 1822 – 4 September 1898), was the daughter of British Royal Navy officer Captain Sir Richard Spencer and Ann, Lady Spencer. She was the wife of Sir George Grey.

Early life

Elizabeth Lucy Spencer wa ...

(1822–1898), daughter of the late Government Resident, Sir Richard Spencer. Their only child, born in 1841 in South Australia, died aged five months and was buried at the West Terrace Cemetery

The West Terrace Cemetery, formerly Adelaide Public Cemetery is a cemetery in Adelaide, South Australia. It is the state's oldest cemetery, first appearing on Colonel William Light's 1837 plan of the Adelaide city centre, to the south-west of ...

. It was not a happy marriage. Grey, obstinate in his domestic affairs as in his first expedition, accused his wife unjustly of flirting with Rear-Admiral Sir Henry Keppel

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Henry Keppel, (14 June 1809 – 17 January 1904) was a Royal Navy officer. His first command was largely spent off the coast of Spain, which was then in the midst of the First Carlist War. As commanding officer of the co ...

on the voyage to Cape Town taken in 1860, and sent her away. Per her obituary, she was an avid walker, reader of literature, devout churchwoman, exceptional hostess and valued friend in her life away from him. It was noted that she had keen insight into character. After their separation, Grey began the habitual abuse of opium

Opium (also known as poppy tears, or Lachryma papaveris) is the dried latex obtained from the seed Capsule (fruit), capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid mor ...

, and struggled to regain his tenacity in maintaining peace between indigenous people

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

and British colonisers.

Grey adopted Annie Maria Matthews (1853–1938) in 1861, following the death of her father, his half-brother, Sir Godfrey Thomas. She married Seymour Thorne George

Seymour Thorne George (10 October 1851 – 2 July 1922) was a New Zealand politician. The premier, Sir George Grey, was his wife's half-uncle and adoptive father, and that relationship resulted in Thorne George representing the South Island elec ...

on 3 December 1872 on Kawau Island

Kawau Island is in the Hauraki Gulf, close to the north-eastern coast of the North Island of New Zealand. It is named after the Māori word for the shag.At its closest point it lies off the coast of the Northland Peninsula, just south of Tā ...

.

Governor of South Australia

Grey was the thirdGovernor of South Australia

The governor of South Australia is the representative in South Australia of the monarch, currently King Charles III. The governor performs the same constitutional and ceremonial functions at the state level as does the governor-general of Aust ...

, from May 1841 to October 1845. Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's government minister, minister in charge of managing certain parts of the British Empire.

The colonial secretary never had responsibility for t ...

, Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known as Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and again from 1865 to 186 ...

, was impressed by Grey's report on governing indigenous people. This led to Grey's appointment as governor.

Grey replaced George Gawler

Colonel George Gawler (21 July 1795 – 7 May 1869) was the second Governor of South Australia, at the same time serving as Resident Commissioner, from 17 October 1838 until 15 May 1841.

Biography Early life

Gawler, born on 21 July 1795, was t ...

, under whose stewardship the colony had become bankrupt through massive spending on public infrastructure. Gawler was also held responsible for the illegal retribution exacted by Major Thomas Shuldham O'Halloran

Thomas Shuldham O'Halloran (25 October 1797 – 16 August 1870) was the first Police Commissioner and first Police Magistrate of South Australia.

Early life and education

O'Halloran was born in Berhampore on 25 October 1797 (now Baharampur) ...

on an Aboriginal tribe, some of whose members had murdered all 25 survivors of the ''Maria

Maria may refer to:

People

* Mary, mother of Jesus

* Maria (given name), a popular given name in many languages

Place names Extraterrestrial

* 170 Maria, a Main belt S-type asteroid discovered in 1877

* Lunar maria (plural of ''mare''), large, ...

'' shipwreck. Grey was governor during another mass murder: the Rufus River Massacre

The Rufus River Massacre was a massacre of at least 30–40 Aboriginal people that took place in 1841 along the Rufus River, in the Central Murray River region of New South Wales (now Australia). The massacre was conducted by a large group of ...

, of at least 30 Aboriginals, by Europeans, on 27 August 1841.

Governor Grey sharply cut spending. The colony soon had full employment, and exports of primary products were increasing. Systematic emigration was resumed at the end of 1844. Gawler, to whom Grey ascribed every problem in the colony, undertook projects to alleviate unemployment that were of lasting value. The real salvation of the colony's finances was the discovery of copper at Burra Burra

Burra is a pastoral centre and historic tourist town in the mid-north of South Australia. It lies east of the Clare Valley in the Bald Hills range, part of the northern Mount Lofty Ranges, and on Burra Creek (South Australia), Burra Creek. The t ...

in 1845.

Aboriginal Witnesses Act

In 1844, Grey enacted a series ordinances and amendments first entitled the Aborigines' Evidence Act and later known as the Aboriginal Witnesses Act. The act, which was created to "facilitate the admission of the unsworn testimony of Aboriginal inhabitants of South Australia and parts adjacent", stipulated that unsworn testimony given byAustralian Aboriginals

Aboriginal Australians are the various indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, excluding the ethnically distinct people of the Torres Strait Islands.

Humans first migrated to Australia 50,000 to 65,000 years ...

would be inadmissible in court. A major consequence of the act in the following decades in Australian history was the frequent dismissal of evidence given by Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are people with familial heritage from, or recognised membership of, the various ethnic groups living within the territory of contemporary Australia prior to History of Australia (1788–1850), British colonisation. The ...

in massacres

A massacre is an event of killing people who are not engaged in hostilities or are defenseless. It is generally used to describe a targeted killing of civilians en masse by an armed group or person.

The word is a loan of a French term for "b ...

perpetrated against them by European settlers.The acts:

*

*

*

*

First term as governor of New Zealand

Grey served as Governor ofNew Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

twice: from 1845

Events

January–March

* January 1 – The Philippines began reckoning Asian dates by hopping the International Date Line through skipping Tuesday, December 31, 1844. That time zone shift was a reform made by Governor–General Narciso ...

to 1853

Events

January–March

* January 6 –

** Florida Governor Thomas Brown signs legislation that provides public support for the new East Florida Seminary, leading to the establishment of the University of Florida.

**U.S. President-elect ...

, and from 1861

This year saw significant progress in the Unification of Italy, the outbreak of the American Civil War, and the emancipation reform abolishing serfdom in the Russian Empire.

Events

January

* January 1

** Benito Juárez captures Mexico Ci ...

to 1868.

During this time, European settlement accelerated, and in 1859 the number of Pākehā

''Pākehā'' (or ''Pakeha''; ; ) is a Māori language, Māori-language word used in English, particularly in New Zealand. It generally means a non-Polynesians, Polynesian New Zealanders, New Zealander or more specifically a European New Zeala ...

came to equal the number of Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

, at around 60,000 each. Settlers were keen to obtain land and some Māori were willing to sell, but there were also strong pressures to retain land – in particular from the Māori King Movement

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

. Grey had to manage the demand for land for the settlers to farm and the commitments in the Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi (), sometimes referred to as ''Te Tiriti'', is a document of central importance to the history of New Zealand, Constitution of New Zealand, its constitution, and its national mythos. It has played a major role in the tr ...

that the Māori chiefs retained full "exclusive and undisturbed possession of their Lands and Estates Forests Fisheries and other properties." The treaty also specifies that Māori will sell land only to the Crown. The potential for conflict between the Māori and settlers was exacerbated as the British authorities progressively eased restrictions on land sales after an agreement at the end of 1840 between the company and Colonial Secretary Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known as Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and again from 1865 to 186 ...

, which provided for land purchases by the New Zealand Company

The New Zealand Company, chartered in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom, was a company that existed in the first half of the 19th century on a business model that was focused on the systematic colonisation of New Ze ...

from the Crown at a discount price, and a charter to buy and sell land under government supervision. Money raised by the government from sales to the company would be spent on assisting migration to New Zealand. The agreement was hailed by the company as "all that we could desire ... our Company is really to be the agent of the state for colonizing NZ." The Government waived its right of pre-emption in the Wellington region, Wanganui and New Plymouth in September 1841.

Following his term as Governor of South Australia, Grey was appointed the third Governor of New Zealand in 1845. During the tenure of his predecessor, Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy, politician and scientist who served as the second governor of New Zealand between 1843 and 1845. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of ...

, violence over land ownership had broken out in the Wairau Valley

Wairau Valley is the valley of the Wairau River in Marlborough, New Zealand and also the name of the main settlement in the upper valley. State Highway 63 runs through the valley. The valley opens onto the Wairau Plain, where Renwick and B ...

in the South Island

The South Island ( , 'the waters of Pounamu, Greenstone') is the largest of the three major islands of New Zealand by surface area, the others being the smaller but more populous North Island and Stewart Island. It is bordered to the north by ...

in June 1843, in what became known as the Wairau Affray

The Wairau Affray of 17 June 1843, also called the Wairau Massacre and the Wairau Incident, was the first serious clash of arms between British settlers and Māori people, Māori in New Zealand after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and t ...

(FitzRoy was later dismissed from office by the Colonial Office for his handling of land issues). It was only in 1846 that the war leader Te Rauparaha

Te Rauparaha ( – 27 November 1849) was a Māori rangatira, warlord, and chief of the Ngāti Toa iwi. One of the most powerful military leaders of the Musket Wars, Te Rauparaha fought a war of conquest that greatly expanded Ngāti Toa south ...

was arrested and imprisoned by Governor Grey without charge, which remained controversial amongst the Ngāti Toa

Ngāti Toa, also called Ngāti Toarangatira or Ngāti Toa Rangatira, is a Māori people, Māori ''iwi'' (tribe) based in the southern North Island and the northern South Island of New Zealand. Ngāti Toa remains a small iwi with a population of ...

people.

Hōne Heke and the Flagstaff War

In March 1845, Māori chief

In March 1845, Māori chief Hōne Heke

Hōne Wiremu Heke Pōkai ( 1807 – 7 August 1850), born Heke Pōkai and later often referred to as Hōne Heke, was a highly influential Māori rangatira (chief) of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe) and a war leader in northern New Zealand; he was ...

began the Flagstaff War

The Flagstaff War, also known as Heke's War, Hōne Heke's Rebellion and the Northern War, was fought between 11 March 1845 and 11 January 1846 in and around the Bay of Islands, New Zealand. The conflict is best remembered for the actions of H� ...

, the causes of which can be attributed to the conflict between what the Ngāpuhi

Ngāpuhi (also known as Ngāpuhi-Nui-Tonu or Ngā Puhi) is a Māori iwi associated with the Northland regions of New Zealand centred in the Hokianga, the Bay of Islands, and Whangārei.

According to the 2023 New Zealand census, the estimate ...

understood to be the meaning of the Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi (), sometimes referred to as ''Te Tiriti'', is a document of central importance to the history of New Zealand, Constitution of New Zealand, its constitution, and its national mythos. It has played a major role in the tr ...

(1840) and the actions of succeeding governors of asserting authority over the Māori. On 18 November 1845 George Grey arrived in New Zealand to take up his appointment as governor, where he was greeted by outgoing Governor FitzRoy, who worked amicably with Grey before departing in January 1846. At this time, Hōne Heke challenged the British authorities, beginning by cutting down the flagstaff on Flagstaff Hill at Kororareka

Russell () is a town in the Bay of Islands, in New Zealand's far north. It was the first permanent European settlement and seaport in New Zealand.

History

Māori settlement

Before the arrival of the Europeans, the area now known as Russ ...

. On this flagstaff the flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand

The United Tribes of New Zealand () was a confederation of Māori tribes based in the north of the North Island, existing legally from 1835 to 1840. It received diplomatic recognition from the United Kingdom, which shortly thereafter proclaimed ...

had previously flown; now the Union Jack

The Union Jack or Union Flag is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. The Union Jack was also used as the official flag of several British colonies and dominions before they adopted their own national flags.

It is sometimes a ...

was hoisted; hence the flagstaff symbolised the grievances of Heke and his ally Te Ruki Kawiti

Te Ruki Kawiti (1770s – 5 May 1854) was a prominent Māori rangatira (chief). He and Hōne Heke successfully fought the British in the Flagstaff War in 1845–46. Belich, James. ''The New Zealand Wars''. (Penguin Books, 1986)

He traced descent ...

, as to changes that had followed the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi (), sometimes referred to as ''Te Tiriti'', is a document of central importance to the history of New Zealand, Constitution of New Zealand, its constitution, and its national mythos. It has played a major role in the tr ...

.

There were many causes of the Flagstaff War and Heke had a number of grievances in relation to the Treaty of Waitangi. While land acquisition

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of Earth not submerged by the ocean or another body of water. It makes up 29.2% of Earth's surface and includes all continents and islands. Earth's land surface ...

by the Church Missionary Society

The Church Mission Society (CMS), formerly known as the Church Missionary Society, is a British Anglican mission society working with Christians around the world. Founded in 1799, CMS has attracted over nine thousand men and women to serve as ...

(CMS) were politicised, the rebellion led by Heke was directed against the colonial forces with the CMS missionaries trying to persuade Heke to end the fighting. Despite the fact that Tāmati Wāka Nene

Tāmati Wāka Nene (1780s – 4 August 1871) was a Māori rangatira (chief) of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe) who fought as an ally of the British in the Flagstaff War of 1845–1846.

Early life

Tāmati Wāka Nene was born to chiefly rank in the Ng� ...

and most of Ngāpuhi sided with the government, the small and ineptly led British had been beaten at Battle of Ohaeawai. Backed by financial support, far more troops, armed with 32-pounder cannons that had been denied to FitzRoy, Grey ordered the attack on Kawiti

Te Ruki Kawiti (1770s – 5 May 1854) was a prominent Māori people, Māori rangatira (chief). He and Hōne Heke successfully fought the United Kingdom, British in the Flagstaff War in 1845–46.James Belich (historian), Belich, James. ''The New ...

's fortress at Ruapekapeka

The Battle of Ruapekapeka took place from late December 1845 to mid-January 1846 between British forces, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Despard, and Māori warriors of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe), led by Hōne Heke and Te Ruki Kawi ...

on 31 December 1845. This forced Kawiti to retreat. Ngāpuhi were astonished that the British could keep an army of nearly 1,000 soldiers in the field continuously. Heke's confidence waned after he was wounded in battle with Tāmati Wāka Nene

Tāmati Wāka Nene (1780s – 4 August 1871) was a Māori rangatira (chief) of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe) who fought as an ally of the British in the Flagstaff War of 1845–1846.

Early life

Tāmati Wāka Nene was born to chiefly rank in the Ng� ...

and his warriors, and by the realisation that the British had far more resources than he could muster; his enemies included some Pākehā Māori supporting colonial forces.

After the Battle of Ruapekapeka, Heke and Kawiti were ready for peace. It was Tāmati Wāka Nene they approached to act as intermediary in negotiations with Governor Grey, who accepted the advice of Nene that Heke and Kawiti should not be punished for their rebellion. The fighting in the north ended and there was no punitive confiscation of Ngāpuhi land.

Ngāti Rangatahi and Hutt Valley campaign

Colonists arrived at Port Nicholson,Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island ...

, in November 1839 in ships chartered by the New Zealand Company

The New Zealand Company, chartered in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom, was a company that existed in the first half of the 19th century on a business model that was focused on the systematic colonisation of New Ze ...

. Within months the New Zealand Company purported to purchase approximately in Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

, Wellington, Whanganui

Whanganui, also spelt Wanganui, is a city in the Manawatū-Whanganui region of New Zealand. The city is located on the west coast of the North Island at the mouth of the Whanganui River, New Zealand's longest navigable waterway. Whanganui is ...

and Taranaki

Taranaki is a regions of New Zealand, region in the west of New Zealand's North Island. It is named after its main geographical feature, the stratovolcano Mount Taranaki, Taranaki Maunga, formerly known as Mount Egmont.

The main centre is the ...

. Disputes arose as to the validity of purchases of land, which remained unresolved when Grey became governor.

The company saw itself as a prospective government of New Zealand and in 1845 and 1846 proposed splitting the colony in two, along a line from Mōkau

Mōkau is a small town on the west coast of New Zealand's North Island, located at the mouth of the Mōkau River on the North Taranaki Bight. Mōkau is in the Waitomo District and Waikato region local government areas, just north of the boundar ...

in the west to Cape Kidnappers

Cape Kidnappers, known in Māori as , and officially named Cape Kidnappers / Te Kauwae-a-Māui, is a headland at the southern extremity of Hawke Bay on the east coast of New Zealand's North Island. It is at the end of an peninsula that protr ...

in the east – with the north reserved for Māori and missionaries. The south would become a self-governing province, known as "New Victoria" and managed by the company for that purpose. Britain's Colonial Secretary rejected the proposal. The company was known for its vigorous attacks on those it perceived as its opponents – the British Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created in 1768 from the Southern Department to deal with colonial affairs in North America (particularly the Thirteen Colo ...

, successive governors of New Zealand, and the Church Missionary Society

The Church Mission Society (CMS), formerly known as the Church Missionary Society, is a British Anglican mission society working with Christians around the world. Founded in 1799, CMS has attracted over nine thousand men and women to serve as ...

(CMS) that was led by the Reverend Henry Williams Henry Williams may refer to:

Politicians

* Henry Williams (activist) (born 2000), chief of staff of the Mike Gravel 2020 presidential campaign

* Henry Williams (MP for Northamptonshire) (died 1558), member of parliament (MP) for Northamptonshire ...

. Williams attempted to interfere with the land purchasing practices of the company, Henry Williams Journal (Fitzgerald, pages 290-291) Letter Henry to Marianne, 6 December 1839 Henry Williams Journal 16 December 1839 (Fitzgerald, p. 302) which exacerbated the ill-will that was directed at the CMS by the Company in Wellington and the promoters of colonisation in Auckland who had access to the Governor and to the newspapers that had started publication.

Unresolved land disputes that had resulted from New Zealand Company operations erupted into fighting in the Hutt Valley

The Hutt Valley (or 'The Hutt') is the large area of fairly flat land in the Hutt River valley in the Wellington Region of New Zealand. Like the river that flows through it, it takes its name from Sir William Hutt, a director of the New Zea ...

in 1846. Ngāti Rangatahi were determined to retain possession of their land. They assembled a force of about 200 warriors led by Te Rangihaeata

Te Rangihaeata ( 1780s – 18 November 1855) was a Ngāti Toa chief and a nephew of Te Rauparaha. He played a leading part in the Wairau Affray and the Hutt Valley Campaign.

Early life

Te Rangihaeata, a member of the Māori iwi Ngāti Toa, was ...

, Te Rauparaha

Te Rauparaha ( – 27 November 1849) was a Māori rangatira, warlord, and chief of the Ngāti Toa iwi. One of the most powerful military leaders of the Musket Wars, Te Rauparaha fought a war of conquest that greatly expanded Ngāti Toa south ...

's nephew (son of his sister Waitohi, died 1839), also the person who had killed unarmed captives in Wairau Affray

The Wairau Affray of 17 June 1843, also called the Wairau Massacre and the Wairau Incident, was the first serious clash of arms between British settlers and Māori people, Māori in New Zealand after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and t ...

. Governor Grey moved troops into the area and by February had assembled nearly a thousand men together with some Māori allies from Te Āti Awa

Te Āti Awa or Te Ātiawa is a Māori iwi with traditional bases in the Taranaki and Wellington regions of New Zealand. Approximately 17,000 people registered their affiliation to Te Āti Awa in 2001, with about 10,000 in Taranaki, 2,000 in We ...

to begin the Hutt Valley campaign.

Māori attacked Taitā on 3 March 1846, but were repulsed by a company of the 96th Regiment. The same day, Grey declared martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

in the Wellington area.

Richard Taylor, a CMS missionary from Whanganui

Whanganui, also spelt Wanganui, is a city in the Manawatū-Whanganui region of New Zealand. The city is located on the west coast of the North Island at the mouth of the Whanganui River, New Zealand's longest navigable waterway. Whanganui is ...

, attempted to persuade Ngāti Tama

Ngāti Tama is a Māori people, Māori iwi, tribe of New Zealand. Their origins, according to oral tradition, date back to Tama Ariki, the chief navigator on the Tokomaru (canoe), Tokomaru waka (canoe), waka. Their historic region is in north Tar ...

and Ngāti Rangatahi to leave the disputed land. Eventually Grey paid compensation for the potato crop they had planted on the land. He also gave them at Kaiwharawhara

Kaiwharawhara is an urban seaside suburb of Wellington in New Zealand's North Island. It is located north of the centre of the city on the western shore of Wellington Harbour, where the Kaiwharawhara Stream reaches the sea from its headwaters ...

by the modern ferry terminal. Chief Taringakuri agreed to these terms. But when the settlers tried to move onto the land they were frightened off.The Canoes of Kupe. R. McIntyre. Fraser books. Masterton (2012) p 51. On 27 February, the British and their Te Āti Awa allies burnt the Māori pā

The word pā (; often spelled pa in English) can refer to any Māori people, Māori village or defensive settlement, but often refers to hillforts – fortified settlements with palisades and defensive :wikt:terrace, terraces – and also to fo ...

at Maraenuku in the Hutt Valley, which had been built on land that the settlers claimed to own. Ngāti Rangatahi retaliated on 1 and 3 March by raiding settlers' farms, destroying furniture, smashing windows, killing pigs, and threatening the settlers with death if they gave the alarm. They murdered Andrew Gillespie and his son. Thirteen families of settlers moved into Wellington for safety. Governor Grey proclaimed martial law on 3 March. Sporadic fighting continued, including a major attack on a defended position at Boulcott's Farm on 6 May. On 6 August 1846, one of the last engagements was fought – the Battle of Battle Hill

The Battle Hill engagement took place from 6 to 13 August 1846, during the New Zealand Wars and was one of the last engagements of the Hutt Valley Campaign.

The engagement was between Ngāti Toa on one side and a colonial force of European tro ...

– after which Te Rangihaeata left the area. The Hutt Valley campaign was followed by the Wanganui campaign

The Whanganui campaign was a brief round of hostilities in the North Island of New Zealand as indigenous Māori fought British settlers and military forces in 1847. The campaign, which included a siege of the fledgling Whanganui settlement (th ...

from April to July 1847.

In January 1846, fifteen chiefs of the area, including Te Rauparaha, had sent a combined letter to the newly arrived Governor Grey, pledging their loyalty to the British Crown. After intercepting letters from Te Rauparaha

Te Rauparaha ( – 27 November 1849) was a Māori rangatira, warlord, and chief of the Ngāti Toa iwi. One of the most powerful military leaders of the Musket Wars, Te Rauparaha fought a war of conquest that greatly expanded Ngāti Toa south ...

, Grey realised he was playing a double game. He was receiving and sending secret instructions to the local Māori who were attacking settlers. In a surprise attack on his pā at Taupō (now named Plimmerton

The suburb of Plimmerton lies in the northwest part of the city of Porirua in New Zealand, adjacent to some of the city's more congenial beaches. State Highway 59 and the North Island Main Trunk railway line pass just east of the main shoppi ...

) at dawn on 23 July, Te Rauparaha, who was now quite elderly, was captured and taken prisoner. The justification given for his arrest was weapons supplied to Māori deemed to be in open rebellion against the Crown. However, charges were never laid against Te Rauparaha so his detention was declared unlawful. While Grey's declaration of Martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

was within his authority, internment without trial would only be lawful if it had been authorised by statute. Te Rauparaha was held prisoner on ''HMS Driver'', then he was taken to Auckland on HMS ''Calliope'' where he remained imprisoned until January 1848.

His son Tāmihana was studying Christianity in Auckland and Te Rauparaha gave him a solemn message that their iwi

Iwi () are the largest social units in New Zealand Māori society. In Māori, roughly means or , and is often translated as "tribe". The word is both singular and plural in the Māori language, and is typically pluralised as such in English.

...

should not take utu

Shamash ( Akkadian: ''šamaš''), also known as Utu ( Sumerian: dutu " Sun") was the ancient Mesopotamian sun god. He was believed to see everything that happened in the world every day, and was therefore responsible for justice and protection ...

against the government. Tāmihana returned to his rohe

The Māori people of New Zealand use the word ' to describe the territory or boundaries of tribes (, although some divide their into several .

Background

In 1793, chief Tuki Te Terenui Whare Pirau who had been brought to Norfolk Island drew ...

to stop a planned uprising. Tāmihana sold the Wairau land to the government for 3,000 pounds. Grey spoke to Te Rauaparaha and persuaded him to give up all outstanding claims to land in the Wairau valley. Then, realising he was old and sick he allowed Te Rauparaha to return to his people at Ōtaki in 1848.

Government at Auckland

Auckland

Auckland ( ; ) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. It has an urban population of about It is located in the greater Auckland Region, the area governed by Auckland Council, which includes outlying rural areas and ...

was made the new capital

Capital and its variations may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** Capital region, a metropolitan region containing the capital

** List of national capitals

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter

Econom ...

in March 1841 and by the time Grey was appointed governor in 1845, it had become a commercial centre as well as including the administrative institutions such as the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

. After the conclusion of the war in the north, government policy was to place a buffer zone of European settlement between the Ngāpuhi

Ngāpuhi (also known as Ngāpuhi-Nui-Tonu or Ngā Puhi) is a Māori iwi associated with the Northland regions of New Zealand centred in the Hokianga, the Bay of Islands, and Whangārei.

According to the 2023 New Zealand census, the estimate ...

and the city of Auckland. The background to the Invasion of Waikato

The invasion of the Waikato became the largest and most important campaign of the 19th-century New Zealand Wars. Hostilities took place in the North Island of New Zealand between the military forces of the colonial government and a federation ...

in 1863 also, in part, reflected a belief that the Auckland was at risk from attack by the Waikato

The Waikato () is a region of the upper North Island of New Zealand. It covers the Waikato District, Waipā District, Matamata-Piako District, South Waikato District and Hamilton City, as well as Hauraki, Coromandel Peninsula, the nort ...

Māori.

Governor Grey had to contend with newspapers that were unequivocal to their support of the interests of the settlers: the ''Auckland Times'', ''Auckland Chronicle'', ''The Southern Cross'', which started by William Brown as a weekly paper in 1843 and ''The New Zealander'', which was started in 1845 by John Williamson. These newspapers were known for their partisan editorial policies – both William Brown and John Williamson were aspiring politicians. ''The Southern Cross'' supported the land claimants, such as the New Zealand Company, and vigorously attacked Governor Grey's administration, while ''The New Zealander'', supported the ordinary settler and the Māori. The northern war adversely affected business in Auckland, such that ''The Southern Cross'' stopped publishing from April 1845 to July 1847. Hugh Carleton, who also became a politician, was the editor of ''The New Zealander'' then later established the ''Anglo-Maori Warder'', which followed an editorial policy in opposition to Governor Grey.

At the time of the northern war ''The Southern Cross'' and ''The New Zealander'' blamed Henry Williams Henry Williams may refer to:

Politicians

* Henry Williams (activist) (born 2000), chief of staff of the Mike Gravel 2020 presidential campaign

* Henry Williams (MP for Northamptonshire) (died 1558), member of parliament (MP) for Northamptonshire ...

and the other CMS missionaries for the Flagstaff War

The Flagstaff War, also known as Heke's War, Hōne Heke's Rebellion and the Northern War, was fought between 11 March 1845 and 11 January 1846 in and around the Bay of Islands, New Zealand. The conflict is best remembered for the actions of H� ...

. The ''New Zealander'' newspaper in a thinly disguised reference to Henry Williams, with the reference to "their Rangatira pakeha entlemencorrespondents", went on to state: We consider these English traitors far more guilty and deserving of severe punishment than the brave natives whom they have advised and misled. Cowards and knaves in the full sense of the terms, they have pursued their traitorous schemes, afraid to risk their own persons, yet artfully sacrificing others for their own aggrandizement, while, probably at the same time, they were most hypocritically professing most zealous loyalty.Official communications also blamed the CMS missionaries for the Flagstaff War. In a letter of 25 June 1846 to

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

, the Colonial Secretary in Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850), was a British Conservative statesman who twice was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835, 1841–1846), and simultaneously was Chancellor of the Exchequer (1834–183 ...

's government, Governor Grey referred to the land acquired by the CMS missionaries and commented that "Her Majesty's Government may also rest satisfied that these individuals cannot be put in possession of these tracts of land without a large expenditure of British blood and money". By the end of his first term as governor, Grey had changed his opinion as to the role of the CMS missionaries, which was limited to attempts to persuade Hōne Heke bring an end to the fighting with the British soldiers and the Ngāpuhi, led by Tāmati Wāka Nene

Tāmati Wāka Nene (1780s – 4 August 1871) was a Māori rangatira (chief) of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe) who fought as an ally of the British in the Flagstaff War of 1845–1846.

Early life

Tāmati Wāka Nene was born to chiefly rank in the Ng� ...

, who remained loyal to the Crown.

Grey was "shrewd and manipulative" and his main objective was to impose British sovereignty over New Zealand, which he did by force when he felt it necessary. But his first strategy to attain land was to attack the close relationship between missionaries and Māori, including Henry Williams who had relationships with chiefs.

In 1847 William Williams published a pamphlet that defended the role of the CMS in the years leading up to the war in the north. The first Anglican bishop of New Zealand

The Diocese of Auckland is one of the thirteen dioceses and ''hui amorangi'' ( Māori bishoprics) of the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia. The Diocese covers the area stretching from North Cape down to the Waikato River, ...

, George Selwyn (bishop of Lichfield), George Selwyn, took the side of Grey in relation to the purchase of the land. Grey twice failed to recover the land in the Supreme Court, and when Williams refused to give up the land unless the charges were retracted, he was dismissed from the CMS in November 1849. Governor Grey's first term of office ended in 1853. In 1854 Williams was reinstated to CMS after Bishop Selwyn later regretted the position and George Grey addressed the committee of the CMS and requested his reinstatement.

When he returned to New Zealand in 1861 for his second term as governor, Sir George and Henry Williams meet at the Te Waimate Mission, Waimate Mission Station in November 1861. Also in 1861 Henry Williams' son Edward Marsh Williams was appointed by Sir George to be the Resident Magistrate for the Bay of Islands and Northern Districts.

Self-government and Constitution Acts

Following a campaign for self-government by settlers in 1846, the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the New Zealand Constitution Act 1846, granting the colony self-government for the first time, requiring Māori to pass an English-language test to be able to participate in the new colonial government. In his instructions to Grey, Colonial Secretary Henry Grey, 3rd Earl Grey, Earl Grey (no relation to George Grey) sent the 1846 Constitution Act with instructions to implement self-government. George Grey responded to Earl Grey that the Act would lead to further hostilities and that the settlers were not ready for self-government. In a dispatch to Earl Grey, Governor Grey stated that in implementing the Act, Her Majesty would not be giving the self-government that was intended, instead:"...she will give to a small fraction of her subjects of one race the power of governing the large majority of her subjects of a different race... there is no reason to think that they would be satisfied with, and submit to, the rule of a minority"Earl Grey agreed and in December 1847 introduced an Act suspending most of the 1846 Constitution Act. Grey wrote a draft of a new Constitution Act while camping on Mount Ruapehu in 1851, forwarding this draft to the Colonial Office later that year. Grey's draft established both provincial and central representative assemblies, allowed for Māori districts and a Governor elected by the General Assembly. Only the latter proposal was rejected by the Parliament of the United Kingdom when it adopted Grey's constitution, the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852. Grey was briefly appointed Governor-in-Chief on 1 January 1848, while he oversaw the establishment of the first provinces of New Zealand, New Ulster Province, New Ulster and New Munster Province, New Munster.

Treaty obligations

In 1846, Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, Lord Stanley, the British Colonial Secretary, who was a devout Anglican, three times British Prime Minister and oversaw the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, was asked by Governor Grey how far he was expected to abide by theTreaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi (), sometimes referred to as ''Te Tiriti'', is a document of central importance to the history of New Zealand, Constitution of New Zealand, its constitution, and its national mythos. It has played a major role in the tr ...

. The direct response in the Queen's name was:

Following the election of the 1st New Zealand Parliament, first parliament in 1853, responsible government was instituted in 1856. The direction of "native affairs" was kept at the sole discretion of the governor, meaning control of Māori affairs and land remained outside of the elected ministry. This quickly became a point of contention between the Governor and the colonial parliament, who retained their own "Native Secretary" to advise them on "native affairs". In 1861, Governor Grey agreed to consult the ministers in relation to native affairs, but this position only lasted until his recall from office in 1867. Grey's successor as governor, George Bowen, took direct control of native affairs until his term ended in 1870. From then on, the elected ministry, led by the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Premier, controlled the colonial government's policy on Māori land.

The short-term effect of the treaty was to prevent the sale of Māori land to anyone other than the Crown. This was intended to protect Māori from the kinds of shady land purchases which had alienated indigenous peoples in other parts of the world from their land with minimal compensation. Before the treaty had been finalised the New Zealand Company had made several hasty land deals and shipped settlers from Great Britain to New Zealand, hoping the British would be forced to accept its land claims as a Glossary of French expressions in English#Fait accompli, fait accompli, in which it was largely successful.

In part, the treaty was an attempt to establish a system of property rights for land with the Crown controlling and overseeing land sale to prevent abuse. Initially, this worked well with the Governor and his representatives having the sole right to buy and sell land from the Māori. Māori were eager to sell land, and settlers eager to buy.

Legacy of Grey's first term as Governor

Grey took pains to tell Māori that he had observed the terms of theTreaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi (), sometimes referred to as ''Te Tiriti'', is a document of central importance to the history of New Zealand, Constitution of New Zealand, its constitution, and its national mythos. It has played a major role in the tr ...

, assuring them that their land rights would be fully recognised. In the Taranaki Province, Taranaki district, Māori were very reluctant to sell their land, but elsewhere Grey was much more successful, and nearly 33 million acres (130,000 km2) were purchased from Māori, with the result that British settlements expanded quickly. Grey was less successful in his efforts to assimilate Māori; he lacked the financial means to realise his plans. Although he subsidised mission schools, requiring them to teach in English, only a few hundred Māori children attended them at any one time.

During Grey's first tenure as Governor of New Zealand, he was created a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (1848). When Grey was knighted he chose Tāmati Wāka Nene

Tāmati Wāka Nene (1780s – 4 August 1871) was a Māori rangatira (chief) of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe) who fought as an ally of the British in the Flagstaff War of 1845–1846.

Early life

Tāmati Wāka Nene was born to chiefly rank in the Ng� ...

as one of his esquires.

Grey gave land for the establishment of Auckland Grammar School in Newmarket, New Zealand, Newmarket, Auckland in 1850. The school was officially recognised as an educational establishment in 1868 through the Auckland Grammar School Appropriation Act of the Auckland Province, Provincial Government. Chris Laidlaw concludes that Grey ran a "ramshackle" administration marked by "broken promises and outright betrayal" of Māori people. Grey's collection of Māori culture, Māori artefacts, one of the earliest from New Zealand and assembled during his first governorship, was donated to the British Museum in 1854.

Much of Grey's manuscript collections were donated to the Auckland Libraries, Auckland Free Public Library in 1887, one of the first substantial donations to the library. Grey's Māori manuscript collections held at Auckland Libraries were added to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register – Asia and the Pacific, Memory of the World Register in 2011.

Governor of Cape Colony

Grey was Governor of Cape Colony from 5 December 1854 to 15 August 1861. He founded Grey College, Bloemfontein in 1855 and was the benefactor for Grey High School in Port Elizabeth, founded by John Paterson (Cape politician), John Paterson in 1856. In 1859 he laid the foundation stone of the Somerset Hospital (Cape Town), New Somerset Hospital, Cape Town. When he left the Cape in 1861 he presented the National Library of South Africa with a remarkable personal collection of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts and rare books.

He began his term as governor a few years following the Convict crisis, Convict Crisis of 1849, an event that significantly influenced Cape politics until the establishment of responsible government in 1872. Grey faced a growing rivalry between the eastern and western halves of the Cape Colony, as well as a small, but also growing, movement for local democracy ("responsible government") and greater independence from British rule.

"There were moves for responsible government in the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope, Cape Parliament in 1855 and 1856 but they were defeated by a combination of Western conservatives and Easterners anxious about the defence of the frontier under a responsible system. But undoubtedly Sir George Grey's political ability, charm and force of personality – aided by the parliamentary leadership of liberal-minded Attorney-General, William Porter – contributed to this result."

In South Africa Grey dealt firmly with the natives, endeavouring to "protect" them from white settlement while simultaneously using reservations to coercively demilitarize them, using natives, in his own words, "as real though unavowed hostages for the tranquillity of their kindred and connections." On more than one occasion, Grey acted as arbitrator between the government of the Orange Free State and the natives, eventually drawing the conclusion that a federation, federated South Africa would be a good thing for everyone. The Orange Free State would have been willing to join the federation, and it is probable that the South African Republic, Transvaal would also have agreed. However, Grey was 50 years before his time: the

Grey was Governor of Cape Colony from 5 December 1854 to 15 August 1861. He founded Grey College, Bloemfontein in 1855 and was the benefactor for Grey High School in Port Elizabeth, founded by John Paterson (Cape politician), John Paterson in 1856. In 1859 he laid the foundation stone of the Somerset Hospital (Cape Town), New Somerset Hospital, Cape Town. When he left the Cape in 1861 he presented the National Library of South Africa with a remarkable personal collection of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts and rare books.

He began his term as governor a few years following the Convict crisis, Convict Crisis of 1849, an event that significantly influenced Cape politics until the establishment of responsible government in 1872. Grey faced a growing rivalry between the eastern and western halves of the Cape Colony, as well as a small, but also growing, movement for local democracy ("responsible government") and greater independence from British rule.

"There were moves for responsible government in the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope, Cape Parliament in 1855 and 1856 but they were defeated by a combination of Western conservatives and Easterners anxious about the defence of the frontier under a responsible system. But undoubtedly Sir George Grey's political ability, charm and force of personality – aided by the parliamentary leadership of liberal-minded Attorney-General, William Porter – contributed to this result."

In South Africa Grey dealt firmly with the natives, endeavouring to "protect" them from white settlement while simultaneously using reservations to coercively demilitarize them, using natives, in his own words, "as real though unavowed hostages for the tranquillity of their kindred and connections." On more than one occasion, Grey acted as arbitrator between the government of the Orange Free State and the natives, eventually drawing the conclusion that a federation, federated South Africa would be a good thing for everyone. The Orange Free State would have been willing to join the federation, and it is probable that the South African Republic, Transvaal would also have agreed. However, Grey was 50 years before his time: the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created in 1768 from the Southern Department to deal with colonial affairs in North America (particularly the Thirteen Colo ...