Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in

West Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

. Located in

southern Arabia, it borders

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

to

the north,

Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

to

the northeast, the south-eastern part of the

Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea () is a region of sea in the northern Indian Ocean, bounded on the west by the Arabian Peninsula, Gulf of Aden and Guardafui Channel, on the northwest by Gulf of Oman and Iran, on the north by Pakistan, on the east by India, and ...

to the east, the

Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden (; ) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Channel, the Socotra Archipelago, Puntland in Somalia and Somaliland to the south. ...

to the south, and the

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

to the west, sharing

maritime borders with

Djibouti

Djibouti, officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to the east. The country has an area ...

,

Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

, and

Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

across the

Horn of Africa. Covering roughly 455,503 square kilometres (175,871 square miles),

with a coastline of approximately , Yemen is the second largest country on the Arabian Peninsula.

Sanaa is its constitutional capital and largest city. Yemen's estimated population is 34.7 million, mostly

Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

Muslims

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

. It is a member of the

Arab League

The Arab League (, ' ), officially the League of Arab States (, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world. The Arab League was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945, initially with seven members: Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt, Kingdom of Iraq, ...

, the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, the

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

and the

Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC; ; ), formerly the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, is an intergovernmental organisation founded in 1969. It consists of Member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, 57 member s ...

.

Owing to its geographic location, Yemen has been at the crossroads of many civilisations for over 7,000 years. In 1200 BCE, the

Sabaeans formed a thriving commercial kingdom that

colonized parts of modern

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

and Eritrea.

In 275 CE, it was succeeded by the

Himyarite Kingdom

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qataban, Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According ...

, which spanned much of Yemen's present-day territory and was heavily influenced by Judaism.

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

arrived in the fourth century, followed by the rapid spread of

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

in the seventh century. From its conversion to Islam, Yemen became a center of Islamic learning, and Yemenite troops played a crucial role in early Islamic conquests. Much of

Yemen's architecture survived until modern times. For centuries, it became a primary producer of

coffee

Coffee is a beverage brewed from roasted, ground coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content, but decaffeinated coffee is also commercially a ...

exported in the port of

Mocha. Various dynasties emerged between the 9th and 16th centuries. During the 19th century, the country was divided between the

Ottoman and

British empires. After

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the

Kingdom of Yemen was established, which in 1962 became the

Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) following a coup. In 1967, the British

Aden Protectorate became the independent

People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen), the first and only officially socialist state in the Arab world. In 1990, the two Yemeni states united to form the modern Republic of Yemen, with

Ali Abdullah Saleh serving as the first president until his resignation in 2012 in the wake of the

Arab Spring.

Since 2011, Yemen has been enduring

a political crisis, marked by

street protests against poverty, unemployment, corruption, and President Saleh's plan to amend

Yemen's constitution and eliminate the presidential term limit.

By 2015, the country became engulfed by

an ongoing civil war with multiple entities vying for governance, including the

Presidential Leadership Council of the internationally recognized government, and the

Houthi movement's

Supreme Political Council

The Supreme Political Council (SPC; ) is an extraconstitutional collective head of state and rival executive established in 2016 in Sanaa by the Houthis and the pro-Houthi faction of the General People's Congress (GPC) to rule Yemen opposed ...

. This conflict, which has escalated to involve various foreign powers, has led to a

severe humanitarian crisis.

Yemen is one of the

least developed countries in the world, facing significant obstacles to

sustainable development

Sustainable development is an approach to growth and Human development (economics), human development that aims to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.United Nations General ...

, and is one of the poorest countries in the

Middle East and North Africa. In 2019, the United Nations reported that Yemen had the highest number of people in need of humanitarian aid, amounting to about 24 million individuals, or nearly 75% of its population.

As of 2020, Yemen ranked highest on the

Fragile States Index and second-worst on the

Global Hunger Index, surpassed only by the

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to Central African Republic–Chad border, the north, Sudan to Central African Republic–Sudan border, the northeast, South Sudan to Central ...

.

As of 2024, Yemen is regarded as the world's least peaceful country by the

Global Peace Index. Additionally, it has the lowest

Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistical composite index of life expectancy, Education Index, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income i ...

out of all non-African countries. Yemen is one of the world's most vulnerable countries to

climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

and among the least prepared to handle its effects.

Etymology

The term ''Yamnat'' was first mentioned in the

Old South Arabian inscriptions on the title of one of the kings of the second

Himyarite Kingdom

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qataban, Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According ...

known as

Shammar Yahri'sh. The term probably referred to the southwestern coastline of the

Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

and the southern coastline between

Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

and

Hadhramaut.

Historical Yemen included much greater territory than the current nation, stretching from northern

'Asir in southwestern

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

to

Dhofar in southern

Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

.

One etymology derives Yemen from ''ymnt'', meaning literally "

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

[of the

Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

]", and significantly plays on the notion of the land to the right (wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Semitic/yamīn-, 𐩺𐩣𐩬). Other sources claim that Yemen is related to ''yamn'' or ''yumn'', meaning "felicity" or "blessed", as much of the country is fertile, in contrast to the barren land of most of Arabia. The Romans called it ''

Arabia Felix'' ("happy" or "fortunate"

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

"), as opposed to ''

Arabia Deserta'' ("deserted Arabia").

Latin and

Greek writers referred to ancient Yemen as "India", which arose from the Persians calling the

Abyssinians whom they came into contact with in South Arabia by the name of the black-skinned people who lived next to them.

History

Ancient history

With its long sea border between eastern and western civilizations, Yemen has long existed at a crossroads of cultures with a strategic location in terms of trade on the west of the Arabian Peninsula. Large settlements for their era existed in the mountains of northern Yemen as early as 5000 BC. The

Sabaean Kingdom came into existence in at least the 12th century BC. The four major kingdoms or tribal confederations in

South Arabia

South Arabia (), or Greater Yemen, is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it has also historically included Najran, Jazan, ...

were Saba,

Hadhramaut,

Qataban

Qataban () was an ancient Yemenite kingdom in South Arabia that existed from the early 1st millennium BCE to the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.

It was one of the six ancient South Arabian kingdoms of ancient Yemen, along with Sabaʾ, Maʿīn ...

, and

Ma'in

Ma'in (; ) was an ancient South Arabian kingdom in modern-day Yemen. It was located along the strip of desert called Ramlat al-Sab'atayn, Ṣayhad by medieval Arab geographers, which is now known as Ramlat al-Sab'atayn. Wadd was the national ...

.

''

Sabaʾ'' () is thought to be biblical Sheba and was the most prominent federation. The Sabaean rulers adopted the title

Mukarrib generally thought to mean ''unifier'', or a ''priest-king'', or the head of the confederation of South Arabian kingdoms, the "king of the kings". The role of the Mukarrib was to bring the various tribes under the kingdom and preside over them all. The Sabaeans built the

Great Dam of Marib around 940 BC. The dam was built to withstand the seasonal flash floods surging down the valley.

By the third century BC, Qataban, Hadhramaut, and Ma'in became independent from Saba and established themselves in the Yemeni arena. Minaean rule stretched as far as

Dedan, with their capital at

Baraqish. The Sabaeans regained their control over Ma'in after the collapse of Qataban in 50 BC. By the time of the Roman expedition to Arabia Felix in 25 BC, the Sabaeans were once again the dominating power in Southern Arabia.

Aelius Gallus was ordered to lead a military campaign to establish Roman dominance over the Sabaeans.

The

Romans had a vague and contradictory geographical knowledge about Arabia Felix. A Roman army of 10,000 men was defeated before reaching

Marib

Marib (; Ancient South Arabian script, Old South Arabian: 𐩣𐩧𐩨/𐩣𐩧𐩺𐩨 ''Mryb/Mrb'') is the capital city of Marib Governorate, Yemen. It was the capital of the ancient kingdom of ''Saba’, Sabaʾ'' (), which some scholars beli ...

.

Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

's close relationship with Aelius Gallus led him to attempt to justify his friend's defeat in his writings. It took the Romans six months to reach Marib and 60 days to return to

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. The Romans blamed their

Nabataean guide and executed him for treachery. No direct mention in Sabaean inscriptions of the Roman expedition has yet been found.

After the Roman expedition (perhaps earlier) the country fell into chaos, and two clans, namely

Hamdan and

Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

, claimed kingship, assuming the title King of Sheba and

Dhu Raydan. Dhu Raydan, ''i.e.'', Himyarites, allied themselves with

Aksum in Ethiopia against the Sabaeans. The chief of

Bakil and king of Saba and Dhu Raydan,

El Sharih Yahdhib, launched successful campaigns against the Himyarites and Habashat, ''i.e.'',

Aksum. El Sharih took pride in his campaigns and added the title Yahdhib to his name, which means "suppressor"; he used to kill his enemies by cutting them to pieces. Sana'a came into prominence during his reign, as he built the

Ghumdan Palace as his place of residence.

The Himyarites annexed Sana'a from Hamdan around 100 AD.

Hashdi tribesmen rebelled against them and regained Sana'a around 180.

Shammar Yahri'sh had conquered Hadhramaut,

Najran, and

Tihamah by 275, thus unifying Yemen and consolidating Himyarite rule. The Himyarites rejected

polytheism and adhered to a consensual form of

monotheism

Monotheism is the belief that one God is the only, or at least the dominant deity.F. L. Cross, Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. A ...

called

Rahmanism.

In 354, Roman Emperor

Constantius II sent an embassy headed by

Theophilos the Indian to convert the Himyarites to Christianity. According to

Philostorgius, the mission was resisted by local Jews.

Several inscriptions have been found in

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

and

Sabaean praising the ruling house in Jewish terms for "...helping and empowering the People of Israel."

According to Islamic traditions, King

As'ad the Perfect mounted a military expedition to support the Jews of

Yathrib. Abu Kariba As'ad, as known from the inscriptions, led a military campaign to central Arabia or

Najd to support the vassal

Kingdom of Kinda against the

Lakhmids. However, no direct reference to Judaism or Yathrib was discovered from his lengthy reign. Abu Kariba died in 445, having reigned for almost 50 years. By 515, Himyar became increasingly divided along religious lines and a bitter conflict between different factions paved the way for an

Aksumite intervention. The last Himyarite king Ma'adikarib Ya'fur was supported by Aksum against his Jewish rivals. Ma'adikarib was Christian and launched a campaign against the Lakhmids in southern

Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

, with the support of other Arab allies of

Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion () was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' continued to be used as a n ...

.

The Lakhmids were a bulwark of

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, which was intolerant to a proselytizing religion like Christianity.

After the death of Ma'adikarib Ya'fur around 521, a Himyarite Jewish warlord called

Dhu Nuwas rose to power. Emperor

Justinian I

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

sent an embassy to Yemen. He wanted the officially Christian Himyarites to use their influence on the tribes in inner Arabia to launch military operations against Persia. Justinian I bestowed the "dignity of king" upon the Arab

sheikh

Sheikh ( , , , , ''shuyūkh'' ) is an honorific title in the Arabic language, literally meaning "elder (administrative title), elder". It commonly designates a tribal chief or a Muslim ulama, scholar. Though this title generally refers to me ...

s of Kindah and

Ghassan in central and northern Arabia.

From early on, Roman and Byzantine policy was to develop close links with the powers of the coast of the

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

. They were successful in converting Aksum and influencing their culture. The results concerning to Yemen were rather disappointing.

A Kendite prince called Yazid bin Kabshat rebelled against Abraha and his Arab Christian allies. A truce was reached once the Great Dam of Marib had suffered a breach. Abraha died around 570. The

Sasanid Empire annexed Aden around 570. Under their rule, most of Yemen enjoyed great autonomy except for Aden and Sana'a. This era marked the collapse of ancient South Arabian civilization, since the greater part of the country was under several independent clans until the arrival of Islam in 630.

Middle Ages

Advent of Islam and the three dynasties

Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

sent his cousin

Ali to Sana'a and its surroundings around 630. At the time, Yemen was the most advanced region in Arabia. The

Banu Hamdan

Banu Hamdan (; Ancient South Arabian script, Musnad: 𐩠𐩣𐩵𐩬) is an ancient, large, and prominent Arab tribe in northern Yemen.

Origins and location

The Hamdan stemmed from the eponymous progenitor Awsala (nickname Hamdan) whose descent ...

confederation was among the first to accept Islam. Muhammad sent

Muadh ibn Jabal, as well to Al-Janad, in present-day

Taiz, and dispatched letters to various tribal leaders. Major tribes, including Himyar, sent delegations to

Medina

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

during the "year of delegations" around 630–631. Several Yemenis accepted Islam before 630, such as

Ammar ibn Yasir,

Al-Ala'a Al-Hadrami,

Miqdad ibn Aswad,

Abu Musa Ashaari, and

Sharhabeel ibn Hasana. A man named

'Abhala ibn Ka'ab Al-Ansi expelled the remaining Persians and claimed he was a prophet of

Rahman. He was assassinated by a Yemeni of Persian origin called

Fayruz al-Daylami. Christians, who were mainly staying in

Najran along with Jews, agreed to pay ''

jizya

Jizya (), or jizyah, is a type of taxation levied on non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Sharia, Islamic law. The Quran and hadiths mention jizya without specifying its rate or amount,Sabet, Amr (2006), ''The American Journal of Islamic Soc ...

h'' (), although some Jews converted to Islam, such as

Wahb ibn Munabbih and

Ka'ab al-Ahbar.

Yemen was stable during the

Rashidun Caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate () is a title given for the reigns of first caliphs (lit. "successors") — Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali collectively — believed to Political aspects of Islam, represent the perfect Islam and governance who led the ...

. Yemeni tribes played a pivotal role in the Islamic expansion into Egypt, Iraq, Persia, the

Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

,

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

,

North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

,

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, and

Andalusia

Andalusia ( , ; , ) is the southernmost autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain, located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in southwestern Europe. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomou ...

. Yemeni tribes who settled in

Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

contributed significantly to the solidification of

Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a membe ...

rule, especially during the reign of

Marwan I. Powerful Yemenite tribes such as Kinda were on his side during the

Battle of Marj Rahit.

Muhammad ibn Abdullah ibn Ziyad founded the Ziyadid dynasty in

Tihamah around 818. The state stretched from

Haly (in present-day Saudi Arabia) to Aden. They nominally recognized the

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 CE), from whom the dynasty takes ...

but ruled independently from

Zabid.

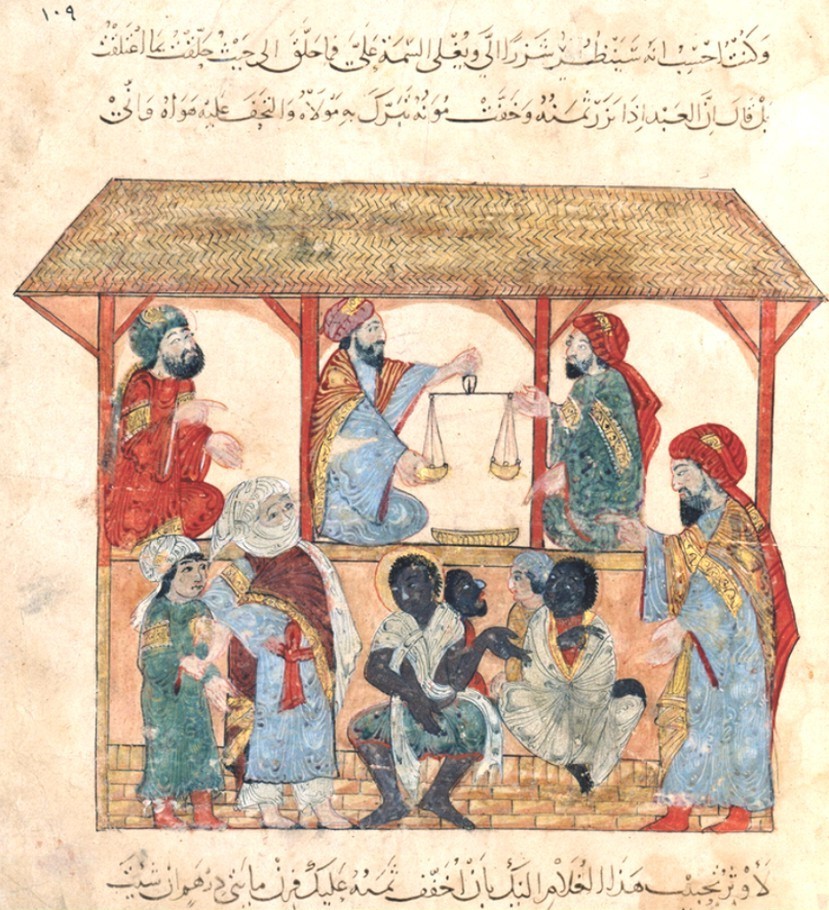

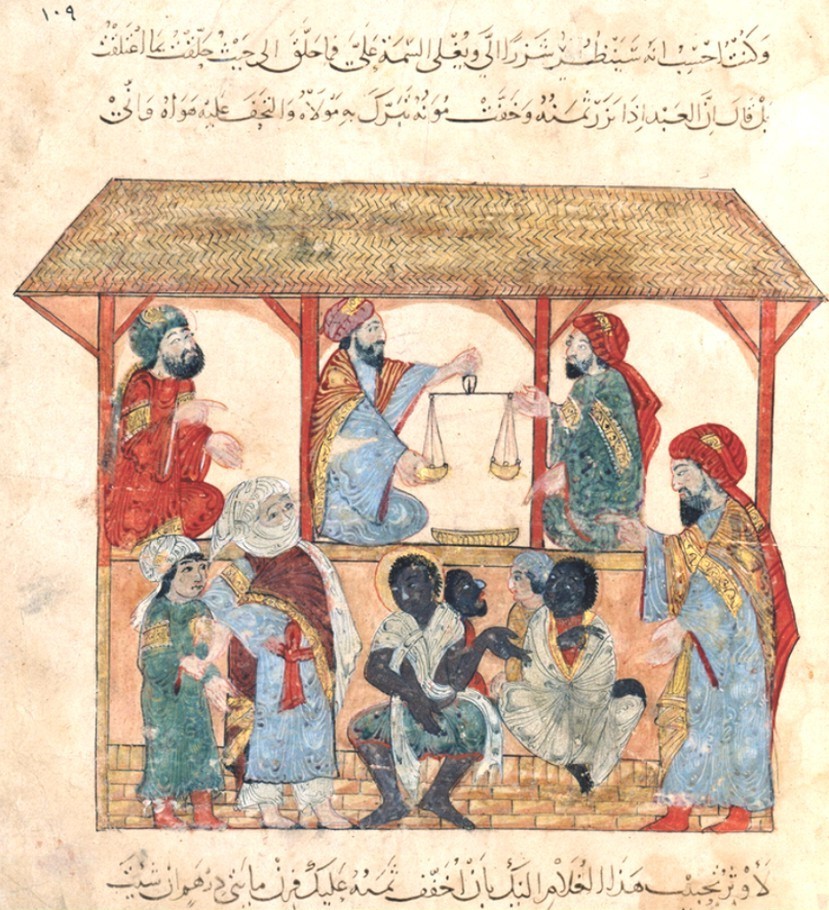

[ Paul Wheatley ''The Places Where Men Pray Together: Cities in Islamic Lands, Seventh Through the Tenth Centuries'' p. 128 University of Chicago Press, 2001 ] By virtue of its location, they developed a special relationship with

Abyssinia. The chief of the

Dahlak islands exported slaves, as well as amber and leopard hides, to the ruler of Yemen.

They controlled only a small portion of the coastal strip in Tihamah along the Red Sea, and never exercised control over the highlands and Hadhramaut. A Himyarite clan called the

Yufirids established their rule over the highlands from

Saada to

Taiz, while Hadhramaut was an Ibadi stronghold and rejected all allegiance to the Abbasids in

Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

.

The first

Zaidi imam,

Yahya ibn al-Husayn, arrived in Yemen in 893. He was a religious cleric and judge who was invited to come to Saada from Medina to arbitrate tribal disputes. Yahya persuaded local tribesmen to follow his teachings. The sect slowly spread across the highlands, as the tribes of

Hashid and

Bakil, later known as "the twin wings of the imamate", accepted his authority. He founded the

Zaidi imamate in 897. Yahya established his influence in Saada and Najran. He also tried to capture Sana'a from the Yufirids in 901 but failed miserably.

Sulayhid dynasty (1047–1138)

The

Sulayhid dynasty was founded in the northern highlands around 1040; at the time, Yemen was ruled by different local dynasties. In 1060,

Ali ibn Muhammad Al-Sulayhi conquered Zabid and killed its ruler Al-Najah, founder of the Najahid dynasty. His sons were forced to flee to Dahlak. Hadhramaut fell into Sulayhid hands after their capture of Aden in 1162.

By 1063, Ali had subjugated

Greater Yemen. He then marched toward

Hejaz

Hejaz is a Historical region, historical region of the Arabian Peninsula that includes the majority of the western region of Saudi Arabia, covering the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif and Al Bahah, Al-B ...

and occupied

Makkah. Ali was married to

Asma bint Shihab, who governed Yemen with her husband.

[Fatima Mernissi ''The Forgotten Queens of Islam'' p. 14 U of Minnesota Press, 1997 ] The

Khutba during

Friday prayers was proclaimed in both her husband's name and hers. No other Arab woman had this honor since the advent of Islam.

Ali al-Sulayhi was killed by Najah's sons on his way to Mecca in 1084. His son Ahmed Al-Mukarram led an army to Zabid and killed 8,000 of its inhabitants. He later installed the Zurayids to govern Aden. al-Mukarram, who had been afflicted with facial paralysis resulting from war injuries, retired in 1087 and handed over power to his wife

Arwa al-Sulayhi. Queen Arwa moved the seat of the Sulayhid dynasty from Sana'a to

Jibla, a small town in central Yemen near

Ibb. She sent Ismaili missionaries to India, where a significant Ismaili community was formed that exists to this day.

[Steven C. Caton ''Yemen'' p. 51 ABC-CLIO, 2013 ]

Queen Arwa continued to rule securely until her death in 1138.

She is still remembered as a great and much-loved sovereign, as attested in Yemeni historiography, literature, and popular lore, where she is referred to as ''Balqis al-sughra'' ("the junior queen of Sheba"). Shortly after Arwa's death, the country was split between five competing petty dynasties along religious lines. The

Ayyubid dynasty

The Ayyubid dynasty (), also known as the Ayyubid Sultanate, was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultan of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid Caliphate of Egyp ...

overthrew the

Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, i ...

in Egypt. A few years after their rise to power,

Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

dispatched his brother

Turan Shah to conquer Yemen in 1174.

Ayyubid conquest (1171–1260)

Turan Shah conquered Zabid from the

Mahdids in 1174, then marched toward Aden in June and captured it from the Zurayids. The

Hamdanid sultans of Sana'a resisted the Ayyubid in 1175, and the Ayyubids did not manage to secure Sana'a until 1189.

The Ayyubid rule was stable in southern and central Yemen, where they succeeded in eliminating the ministates of that region, while Ismaili and Zaidi tribesmen continued to hold out in several fortresses.

The Ayyubids failed to capture the Zaydis stronghold in northern Yemen. In 1191, Zaydis of

Shibam Kawkaban

Shibam Kawkaban ()

is a Twin cities, double town in Shibam Kawkaban District, Al Mahwit Governorate, Yemen, located 38 km west-northwest of Sanaa, the national capital. It consists of two distinct adjoining towns, Shibam () and Kawkaban () ...

rebelled and killed 700 Ayyubid soldiers. Imam

Abdullah bin Hamza proclaimed the imamate in 1197 and fought al-Mu'izz Ismail, the Ayyubid Sultan of Yemen. Imam Abdullah was defeated at first but was able to conquer Sana'a and

Dhamar in 1198, and al-Mu'izz Ismail was assassinated in 1202.

Abdullah bin Hamza carried on the struggle against the Ayyubid until his death in 1217. After his demise, the Zaidi community was split between two rival imams. The Zaydis were dispersed, and a truce was signed with the Ayyubid in 1219.

The Ayyubid army was defeated in

Dhamar in 1226.

Ayyubid Sultan Mas'ud Yusuf left for Mecca in 1228, never to return.

Other sources suggest that he was forced to leave for Egypt instead in 1223.

Rasulid dynasty (1229–1454)

The

Rasulid dynasty was established in 1229 by

Umar ibn Ali, who was appointed deputy governor by the Ayyubids in 1223. When the last Ayyubid ruler left Yemen in 1229, Umar stayed in the country as caretaker. He subsequently declared himself an independent king by assuming the title "al-Malik Al-Mansur" (the king assisted by

Allah

Allah ( ; , ) is an Arabic term for God, specifically the God in Abrahamic religions, God of Abraham. Outside of the Middle East, it is principally associated with God in Islam, Islam (in which it is also considered the proper name), althoug ...

).

Umar first established himself at Zabid, then moved into the mountainous interior, taking the important highland centre Sana'a. However, the Rasulid capitals were Zabid and Taiz. He was assassinated by his nephew in 1249.

Omar's son

Yusuf

Yusuf ( ') is a male name meaning " God increases" (in piety, power and influence).From the Hebrew יהוה להוסיף ''YHWH Lhosif'' meaning " YHWH will increase/add". It is the Arabic equivalent of the Hebrew name Yosef and the English na ...

defeated the faction led by his father's assassins and crushed several counterattacks by the Zaydi imams who still held on in the northern highland. Mainly because of the victories he scored over his rivals, he assumed the honorific title "al-Muzaffar" (the victorious).

After the

fall of Baghdad to the

Mongols

Mongols are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, China ( Inner Mongolia and other 11 autonomous territories), as well as the republics of Buryatia and Kalmykia in Russia. The Mongols are the principal member of the large family o ...

in 1258, al-Muzaffar Yusuf I appropriated the title of

caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

.

He chose the city of Taiz to become the political capital of the kingdom because of its strategic location and proximity to Aden.

The Rasulid sultans built numerous

Madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , ), sometimes Romanization of Arabic, romanized as madrasah or madrassa, is the Arabic word for any Educational institution, type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whet ...

s to solidify the

Shafi'i

The Shafi'i school or Shafi'i Madhhab () or Shafi'i is one of the four major schools of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), belonging to the Ahl al-Hadith tradition within Sunni Islam. It was founded by the Muslim scholar, jurist, and traditionis ...

school of thought, which is still the dominant school of

jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, also known as theory of law or philosophy of law, is the examination in a general perspective of what law is and what it ought to be. It investigates issues such as the definition of law; legal validity; legal norms and values ...

amongst Yemenis today.

Under their rule, Taiz and Zabid became major international centres of Islamic learning.

The kings were educated men in their own right, who not only had important libraries but also wrote treatises on a wide array of subjects, ranging from astrology and medicine to agriculture and genealogy.

They had a difficult relationship with the

Mamluks of Egypt because the latter considered them a vassal state.

Their competition centred over the Hejaz and the right to provide ''

kiswa'' of the

Ka'aba in Mecca.

The dynasty became increasingly threatened by disgruntled family members over the problem of succession, combined with periodic tribal revolts, as they were locked in a war of attrition with the Zaydi imams in the northern highlands.

During the last 12 years of Rasulid rule, the country was torn between several contenders for the kingdom. The weakening of the Rasulid provided an opportunity for the

Banu Taher clan to take over and establish themselves as the new rulers of Yemen in 1454 AD.

Tahirid dynasty (1454–1517)

The

Tahirids were a local clan based in

Rada'a. They built schools, mosques, and irrigation channels, as well as water cisterns and bridges in Zabid, Aden,

Rada'a, and Juban. Their best-known monument is the

Amiriya Madrasa in

Rada' District, which was built in 1504. The Tahirids were too weak either to contain the Zaydi imams or to defend themselves against foreign attacks.

Realizing how rich the Tahirid realm was, the Mamluks decided to conquer it.

[Steven C. Caton ''Yemen'' p. 59 ABC-CLIO, 2013 ] The Mamluk army, with the support of forces loyal to Zaydi Imam

Al-Mutawakkil Yahya Sharaf ad-Din, conquered the entire Tahirid realm but failed to capture Aden in 1517. The Mamluk victory was short-lived. The

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

conquered Egypt, hanging the last Mamluk Sultan in

Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

.

The Ottomans had not decided to conquer Yemen until 1538. The Zaydi highland tribes emerged as national heroes

by offering stiff, vigorous resistance to the Turkish occupation.

The Mamluks tried to attach Yemen to Egypt and the Portuguese led by

Afonso de Albuquerque, occupied the island of

Socotra

Socotra, locally known as Saqatri, is a Yemeni island in the Indian Ocean. Situated between the Guardafui Channel and the Arabian Sea, it lies near major shipping routes. Socotra is the largest of the six islands in the Socotra archipelago as ...

and made an unsuccessful attack on Aden in 1513.

Portuguese (1498-1756)

Starting in the 15th century,

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

intervened, dominating the port of Aden for about 20 years and maintaining a fortified enclave on the island of Socotra during this period. From the 16th century, the Portuguese posed an immediate threat to Indian Ocean trade. The Mamluks therefore sent an army under Hussein al-Kurdi to fight the intruders The Mamluk sultan went to Zabid in 1515 and entered into diplomatic talks with the Tahiri sultan 'Amir bin Abdulwahab for money that would be needed for the jihad against the Portuguese. Instead of confronting them, the Mamluks, who were running out of food and water, landed on the coast of Yemen and began harassing the villagers of Tihamah to obtain the supplies they needed.

The interest of Portugal on the Red Sea consisted on the one hand of guaranteeing contacts with a Christian ally in Ethiopia and on the other of being able to attack Mecca and the Arab territories from the rear, while still having absolute dominance over trade of spices, the main intention was to dominate the commerce of the cities on the coast of Africa and Arabia. To this end, Portugal sought to influence and dominate by force or persuasion all the ports and kingdoms that fought among themselves. It was common for Portugal to keep under its influence the Arab allies that were interested in maintaining independence from other Arab states in the region.

Modern history

The Zaydis and Ottomans

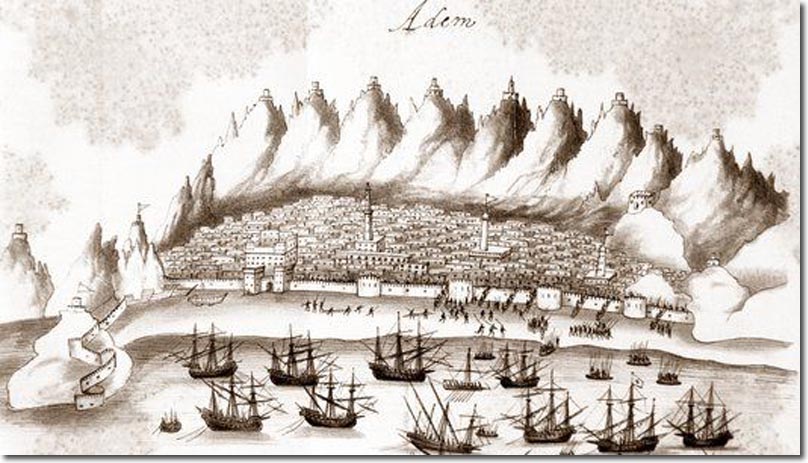

The Ottomans had two fundamental interests to safeguard in Yemen: The Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina, and the trade route with India in spices and textiles—both threatened, and the latter virtually eclipsed, by the arrival of the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea in the early 16th century.

Hadım Suleiman Pasha, the Ottoman governor of

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, was ordered to command a fleet of 90 ships to conquer Yemen. The country was in a state of incessant anarchy and discord as Pasha described it by saying:

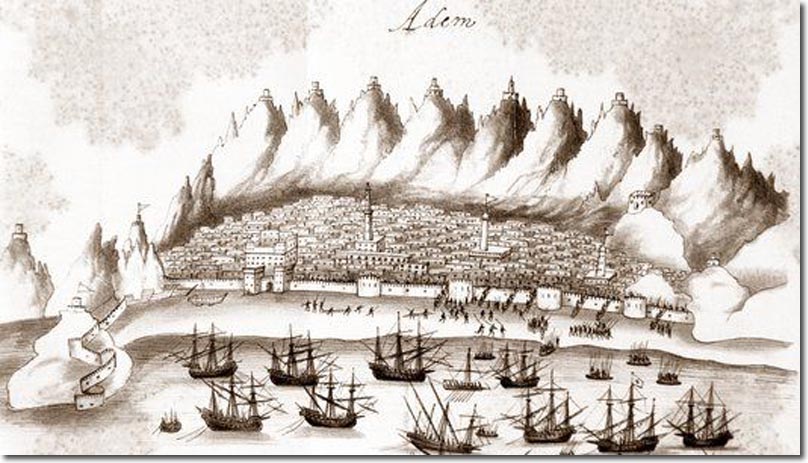

Imam

al-Mutawakkil Yahya Sharaf ad-Din ruled over the northern highlands including Sana'a, while Aden was held by the last Tahiride Sultan 'Amir ibn Dauod. Pasha stormed Aden in 1538, killing its ruler, and extended Ottoman authority to include Zabid in 1539 and eventually Tihamah in its entirety.

Zabid became the administrative headquarters of

Yemen Eyalet.

The Ottoman governors did not exercise much control over the highlands. They held sway mainly in the southern coastal region, particularly around Zabid, Mocha, and Aden. Of 80,000 soldiers sent to Yemen from Egypt between 1539 and 1547, only 7,000 survived.

The Ottoman accountant-general in Egypt remarked:

The Ottomans sent yet another expeditionary force to Zabid in 1547, while Imam

al-Mutawakkil Yahya Sharaf ad-Din was ruling the highlands independently. Yahya chose his son Ali to succeed him, a decision that infuriated his other son

al-Mutahhar ibn Yahya.

Al-Mutahhar was lame, so he was not qualified for the imamate.

He urged Oais Pasha, the Ottoman colonial governor in

Zabid, to attack his father. Indeed, Ottoman troops supported by tribal forces loyal to Imam al-Mutahhar stormed Taiz and marched north toward Sana'a in August 1547. The Turks officially made Imam al-Mutahhar a ''

Sanjak-bey'' with authority over

'Amran. Imam al-Mutahhar assassinated the Ottoman colonial governor and recaptured Sana'a, but the Ottomans, led by

Özdemir Pasha, forced al-Mutahhar to retreat to his fortress in

Thula. Özdemir Pasha effectively put Yemen under Ottoman rule between 1552 and 1560. Özdemir died in Sana'a in 1561 and was succeeded by

Mahmud Pasha.

Mahmud Pasha was described by other Ottoman officials as a corrupt and unscrupulous governor, and he was displaced by Ridvan Pasha in 1564. By 1565, Yemen was split into two provinces, the highlands under the command of Ridvan Pasha and Tihamah under Murad Pasha. Imam al-Mutahhar launched a propaganda campaign in which he claimed that the prophet Mohammed came to him in a dream and advised him to wage ''jihad'' against the Ottomans. Al-Mutahhar led the tribes to capture Sana'a from Ridvan Pasha in 1567. When Murad tried to relieve Sana'a, highland tribesmen ambushed his unit and slaughtered all of them.

Over 80 battles were fought. The last decisive encounter took place in Dhamar around 1568, in which Murad Pasha was beheaded and his head sent to al-Mutahhar in Sana'a.

By 1568, only Zabid remained under the possession of the Turks.

In 1632, Al-Mu'ayyad Muhammad sent an expeditionary force of 1,000 men to conquer Mecca.

The army entered the city in triumph and killed its governor.

The Ottomans sent an army from Egypt to fight the Yemenites.

Seeing that the Turkish army was too numerous to overcome, the Yemeni army retreated to a valley outside Mecca.

Ottoman troops attacked the Yemenis by hiding at the wells that supplied them with water. This plan proceeded successfully, causing the Yemenis over 200 casualties, most from thirst.

The tribesmen eventually surrendered and returned to Yemen. Al-Mu'ayyad Muhammad died in 1644. He was succeeded by

Al-Mutawakkil Isma'il

Al-Mutawakkil Isma'il (c. 1610 – 15 August 1676) was an Imam of Yemen who ruled the country from 1644 until 1676. He was a son of Al-Mansur al-Qasim. His rule saw the biggest territorial expansion of the Zaidiyyah imamate in Greater Yemen.

Ear ...

, another son of al-Mansur al-Qasim, who conquered Yemen in its entirety.

Yemen became the sole

coffee

Coffee is a beverage brewed from roasted, ground coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content, but decaffeinated coffee is also commercially a ...

producer in the world. The country established diplomatic relations with the

Safavid dynasty

The Safavid dynasty (; , ) was one of Iran's most significant ruling dynasties reigning from Safavid Iran, 1501 to 1736. Their rule is often considered the beginning of History of Iran, modern Iranian history, as well as one of the gunpowder em ...

of Persia, Ottomans of Hejaz,

Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an Early modern period, early modern empire in South Asia. At its peak, the empire stretched from the outer fringes of the Indus River Basin in the west, northern Afghanistan in the northwest, and Kashmir in the north, to ...

in India, and Ethiopia, as well. In the first half of the 18th century, the Europeans broke Yemen's monopoly on coffee by smuggling coffee trees and cultivating them in their own colonies in the East Indies, East Africa, the West Indies, and Latin America. The imamate did not follow a cohesive mechanism for succession, and family quarrels and tribal insubordination led to the political decline of the Qasimi dynasty in the 18th century.

Great Britain and the nine regions

The British were looking for a coal depot to service their steamers en route to India. It took 700 tons of coal for a round-trip from

Suez

Suez (, , , ) is a Port#Seaport, seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest c ...

to

Bombay

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial centre, financial capital and the list of cities i ...

.

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

officials decided on

Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

. The

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

tried to reach an agreement with the Zaydi imam of Sana'a, permitting them a foothold in Mocha, and when unable to secure their position, they extracted a similar agreement from the

Sultan of Lahej, enabling them to consolidate a position in Aden.

The British managed to occupy Aden and evicted the Sultan of Lahej from Aden and forced him to accept their "protection".

In November 1839, 5,000 tribesmen tried to retake the town but were repulsed and 200 were killed.

With emigrants from India, East Africa, and Southeast Asia, Aden grew into a world city. In 1850, only 980 Arabs were registered as original inhabitants of the city. The English presence in Aden put them at odds with the Ottomans. The Turks asserted to the British that they held sovereignty over the whole of Arabia, including Yemen as the successor of Mohammed and the Chief of the Universal Caliphate.

Ottoman return

The Ottomans were concerned about the British expansion from the

British-ruled subcontinent to the Red Sea and Arabia. They returned to the Tihamah in 1849 after an absence of two centuries.

Rivalries and disturbances continued among the Zaydi imams, between them and their deputies, with the

ulema, with the heads of tribes, as well as with those who belonged to other sects. Some citizens of Sana'a were desperate to return law and order to Yemen and asked the Ottoman Pasha in Tihamah to pacify the country. The opening of the

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

in 1869 strengthened the Ottoman decision to remain in Yemen.

By 1873, the Ottomans succeeded in conquering the northern highlands. Sana'a became the administrative capital of

Yemen Vilayet.

The Ottomans learned from their previous experience and worked on the disempowerment of local lords in the highland regions. They even attempted to secularize the Yemeni society, while

Yemenite Jews

Yemenite Jews, also known as Yemeni Jews or Teimanim (from ; ), are a Jewish diaspora group who live, or once lived, in Yemen, and their descendants maintaining their customs. After several waves of antisemitism, persecution, the vast majority ...

came to perceive themselves in Yemeni nationalist terms. The Ottomans appeased the tribes by forgiving their rebellious chiefs and appointing them to administrative posts. They introduced a series of reforms to enhance the country's economic welfare. However, corruption was widespread in the Ottoman administration in Yemen. This was because only the worst of the officials were appointed because those who could avoid serving in Yemen did so.

The Ottomans had reasserted control over the highlands for a temporary duration.

The so-called ''

Tanzimat'' reforms were considered heretic by the Zaydi tribes. In 1876, the Hashid and Bakil tribes rebelled against the Ottomans; the Turks had to appease them with gifts to end the uprising.

The tribal chiefs were difficult to appease and an endless cycle of violence curbed Ottoman efforts to pacify the land.

Ahmed Izzet Pasha proposed that the Ottoman army evacuate the highlands and confine itself to Tihamah, and not unnecessarily burden itself with continuing military operation against the Zaydi tribes.

Imam

Yahya Hamidaddin led a rebellion against the Turks in 1904; the rebels disrupted the Ottoman ability to govern. The revolts between 1904 and 1911 were especially damaging to the Ottomans, costing them as many as 10,000 soldiers and as much as 500,000

pounds per year. The Ottomans signed a treaty with imam

Yahya Hamidaddin in 1911. Under the treaty, Imam Yahya was recognized as an autonomous leader of the Zaydi northern highlands. The Ottomans continued to rule

Shafi'i

The Shafi'i school or Shafi'i Madhhab () or Shafi'i is one of the four major schools of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), belonging to the Ahl al-Hadith tradition within Sunni Islam. It was founded by the Muslim scholar, jurist, and traditionis ...

areas in the mid-south until their departure in 1918.

Mutawakkilite Kingdom

Imam Yahya hamid ed-Din al-Mutawakkil was ruling the northern highlands independently from 1911, from which he began a conquest of the Yemen lands. In 1925 Yahya captured al-Hudaydah from the

Idrisids.

In 1927, Yahya's forces were about away from Aden, Taiz, and Ibb, and were bombed by the British for five days; the imam had to pull back.

Small

Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu ( ; , singular ) are pastorally nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia (Iraq). The Bedouin originated in the Sy ...

forces, mainly from the

Madh'hij confederation of

Marib

Marib (; Ancient South Arabian script, Old South Arabian: 𐩣𐩧𐩨/𐩣𐩧𐩺𐩨 ''Mryb/Mrb'') is the capital city of Marib Governorate, Yemen. It was the capital of the ancient kingdom of ''Saba’, Sabaʾ'' (), which some scholars beli ...

, attacked

Shabwah but were bombed by the British and had to retreat.

The

Italian Empire

The Italian colonial empire (), also known as the Italian Empire (''Impero italiano'') between 1936 and 1941, was founded in Africa in the 19th century. It comprised the colonies, protectorates, concession (territory), concessions and depende ...

was the first to recognize Yahya as the king of Yemen in 1926. This created a great deal of anxiety for the British, who interpreted it as recognition of Imam Yahya's claim to sovereignty over Greater Yemen, which included the Aden protectorate and Asir. The Idrisis turned to

Ibn Saud seeking his protection from Yahya. However, in 1932, the Idrisis broke their accord with Ibn Saud and went back to Yahya seeking help against Ibn Saud, who had begun liquidating their authority and expressed his desire to annex those territories into his own Saudi domain.

Yahya demanded the return of all Idrisi dominion.

Negotiations between Yahya and Ibn Saud proved fruitless. After the 1934 Saudi-Yemeni war, Ibn Saud announced a ceasefire in May 1934.

Imam Yahya agreed to release Saudi hostages and the surrender of the Idrisis to Saudi custody. Imam Yahya ceded the three provinces of Najran, Asir, and

Jazan for 20 years. and signed another treaty with the British government in 1934. The imam recognized the British sovereignty over Aden protectorate for 40 years. Out of fear for

Hudaydah, Yahya did submit to these demands.

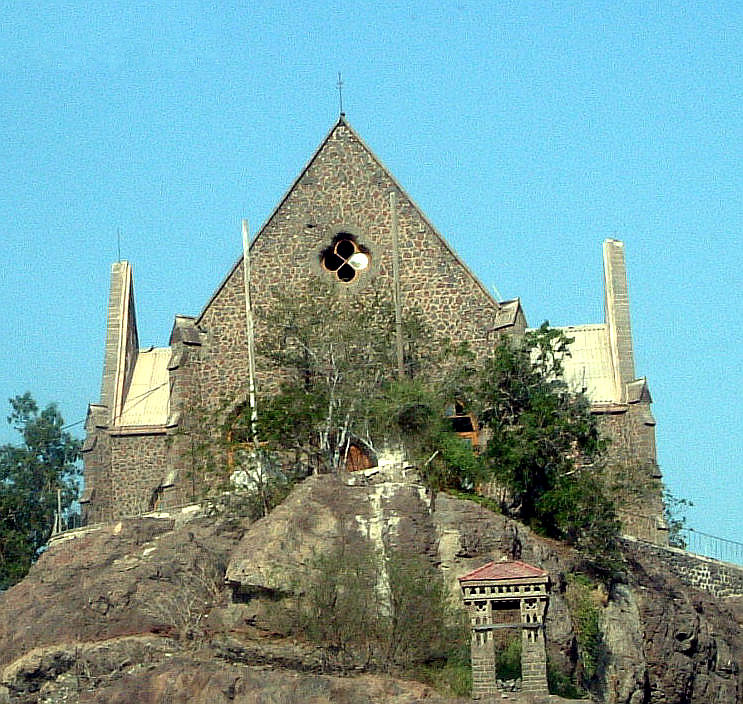

Colonial Aden

Starting in 1890, hundreds of Yemeni people from Hajz, Al-Baetha, and Taiz migrated to Aden to work at ports, and as labourers. This helped the population of Aden once again become predominantly Arab after, having been declared a free zone, it had become mostly foreigners. During World War II, Aden had increasing economic growth and became the second-busiest port in the world after

New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

.

[Kiren Aziz Chaudhry The Price of Wealth: Economies and Institutions in the Middle East p. 117] After the rise of labour unions, a rift was apparent between the sectors of workers and the first signs of resistance to the occupation started in 1943.

founded the first Arabic club and school in Aden, and was the first to start working towards a union.

The

Colony of Aden was divided into an eastern colony and a western colony. Those were further divided into 23 sultanates and emirates, and several independent tribes that had no relationships with the sultanates. The deal between the sultanates and Britain detailed protection and complete control of foreign relations by the British. The Sultanate of Lahej was the only one in which the sultan was referred to as ''His Highness''. The

Federation of South Arabia

The Federation of South Arabia (FSA; ') was a federal state under British protectorate, British protection in what would become South Yemen. Its capital was Aden.

History

Originally formed on April 4, 1962 from 15 states of the Federation ...

was created by the British to counter

Arab nationalism by giving more freedom to the rulers of the nations.

The

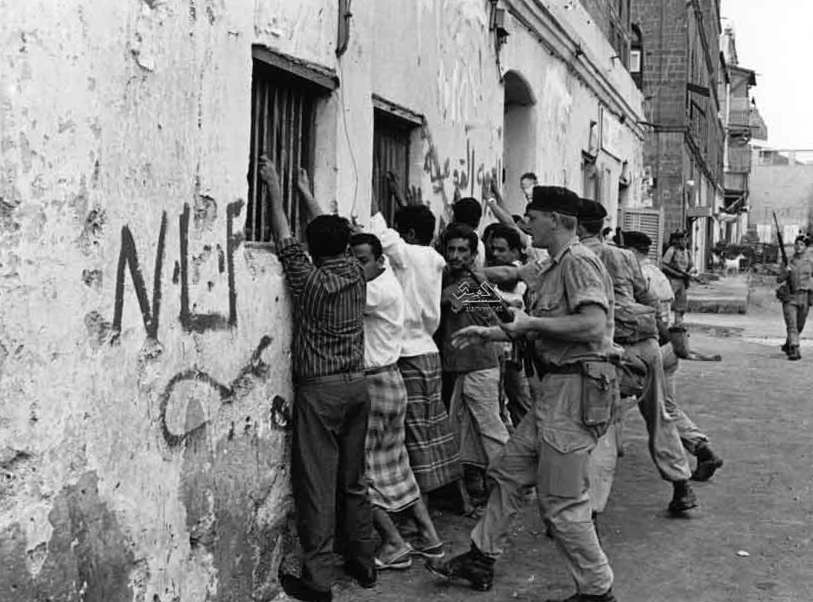

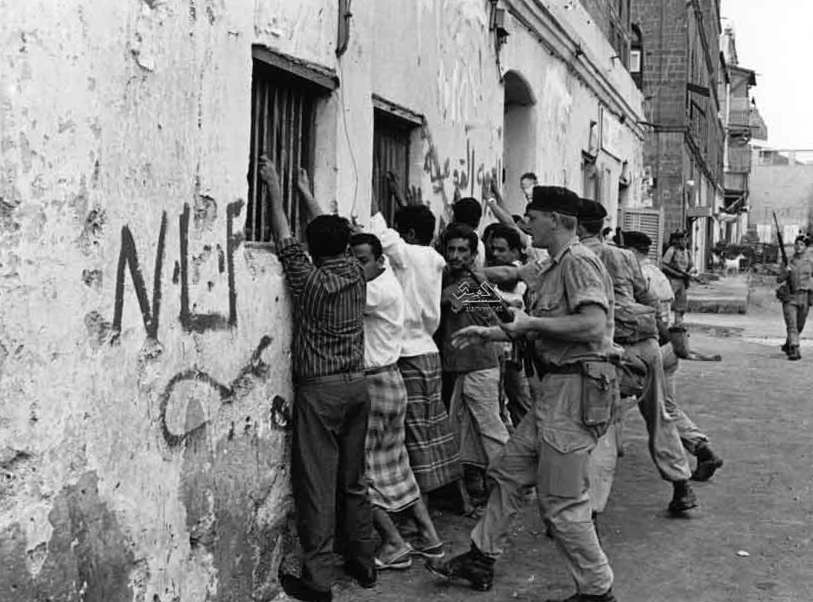

North Yemen Civil War inspired many in the south to rise against the British rule. The

National Liberation Front (NLF) of Yemen was formed with the leadership of

Qahtan Muhammad Al-Shaabi. The NLF hoped to destroy all the sultanates and eventually unite with the

Yemen Arab Republic. Most of the support for the NLF came from

Radfan and Yafa, so the British launched Operation Nutcracker, which completely burned Radfan in January 1964.

Two states

Arab nationalism had an influence in some circles who opposed the lack of modernization efforts in the Mutawakkilite monarchy. This became apparent when Imam

Ahmad bin Yahya died in 1962. He was succeeded by his son, but army officers attempted to seize power, sparking the

North Yemen Civil War. The Hamidaddin royalists were supported by Saudi Arabia, Britain, and Jordan (mostly with weapons and financial aid, but also with small military forces), whilst the military rebels were backed by Egypt. Egypt provided the rebels with weapons and financial assistance, but also sent a large military force to participate in the fighting. Israel covertly supplied weapons to the royalists to keep the Egyptian military busy in Yemen and make Nasser less likely to initiate a conflict in the Sinai. After six years of civil war, the military rebels formed the

Yemen Arab Republic.

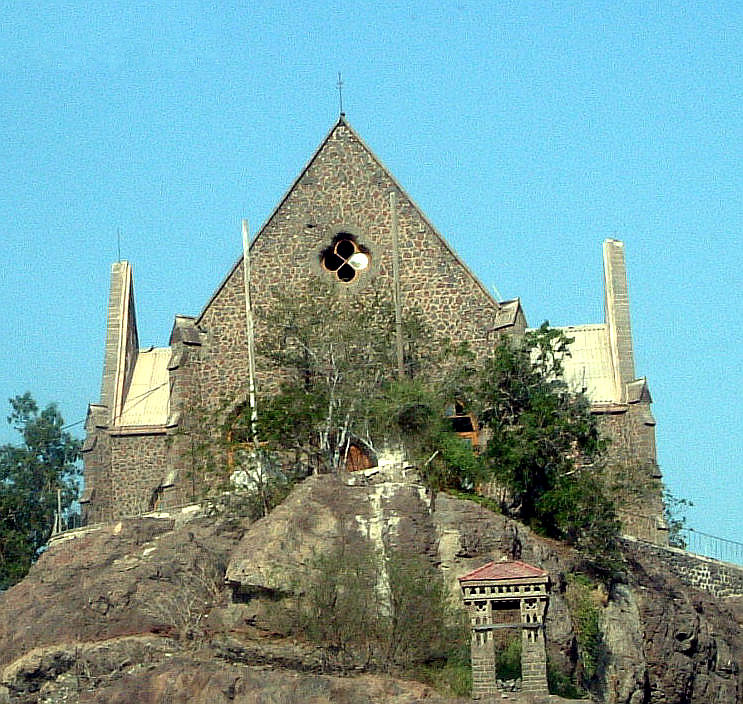

The revolution in the north coincided with the

Aden Emergency, which hastened the end of British rule in the south.

[The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "Yemeni Civil War". ''Encyclopedia Britannica'', 18 Jan. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/event/Yemeni-Civil-War. Accessed 3 April 2025] On 30 November 1967, the state of South Yemen was formed, comprising Aden and the former Protectorate of South Arabia. This socialist state was later officially known as the

People's Democratic Republic of Yemen and a programme of nationalisation was begun.

Relations between the two Yemeni states fluctuated between peaceful and hostile. The South was supported by the Eastern bloc. The North, however, was not able to get the same connections. In 1972, the two states fought a war. The war was resolved with a ceasefire and negotiations brokered by the

Arab League

The Arab League (, ' ), officially the League of Arab States (, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world. The Arab League was formed in Cairo on 22 March 1945, initially with seven members: Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt, Kingdom of Iraq, ...

, where it was declared that unification would eventually occur. In 1978,

Ali Abdullah Saleh was named as president of the Yemen Arab Republic.

After the war, the North complained about the South's help from foreign countries. This included Saudi Arabia.

In 1979, fresh fighting between the two states resumed and efforts were renewed to bring about unification.

Thousands were killed in 1986 in the

South Yemen Civil War

The South Yemeni crisis, colloquially referred to in Yemen as the events of '86, was a failed coup d'etat and brief civil war which took place on January 13, 1986, in South Yemen. The civil war developed as a result of ideological differences, ...

.

President

Ali Nasser Muhammad fled to the north and was later sentenced to death for treason. A new government formed.

Unification and civil war

In 1990, the two governments reached a full agreement on the joint governing of Yemen, and the countries were merged on 22 May 1990, with Saleh as president.

The president of South Yemen,

Ali Salim al-Beidh, became vice president.

A unified

parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

was formed and a unity constitution was agreed upon.

In the

1993 parliamentary election, the first held after unification, the

General People's Congress won 122 of 301 seats.

After the

invasion of Kuwait

The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, codenamed Project 17, began on 2 August 1990 and marked the beginning of the Gulf War. After defeating the Kuwait, State of Kuwait on 4 August 1990, Ba'athist Iraq, Iraq went on to militarily occupy the country fo ...

crisis in 1990, Yemen's president opposed military intervention from non-Arab states. As a member of the

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

for 1990 and 1991, Yemen abstained on a number of

UNSC resolutions concerning Iraq and Kuwait

and voted against the "...use of force resolution." The vote outraged the U.S., and Saudi Arabia expelled 800,000 Yemenis in 1990 and 1991 to punish Yemen for its opposition to the intervention.

In the absence of strong state institutions,

elite politics in Yemen constituted a ''de facto'' form of

collaborative governance, where competing tribal, regional, religious, and political interests agreed to hold themselves in check through tacit acceptance of the balance it produced. The informal political settlement was held together by a power-sharing deal among three men: President Saleh, who controlled the state; major general

Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, who controlled the largest share of the

Yemeni Armed Forces; and

Abdullah ibn Husayn al-Ahmar, figurehead of the Islamist

al-Islah party and Saudi Arabia's chosen broker of transnational

patronage payments to various political players, including tribal

sheikh

Sheikh ( , , , , ''shuyūkh'' ) is an honorific title in the Arabic language, literally meaning "elder (administrative title), elder". It commonly designates a tribal chief or a Muslim ulama, scholar. Though this title generally refers to me ...

s. The Saudi payments have been intended to facilitate the tribes' autonomy from the Yemeni government and to give the Saudi government a mechanism with which to weigh in on Yemen's political decision-making.

Following food riots in major towns in 1992, a new coalition government made up of the ruling parties from both the former Yemeni states was formed in 1993. However, Vice President al-Beidh withdrew to Aden in August 1993 and said he would not return to the government until his grievances were addressed. These included northern violence against his

Yemeni Socialist Party, as well as the economic marginalization of the south.

Negotiations to end the political deadlock dragged on into 1994. The government of Prime Minister

Haydar Abu Bakr Al-Attas became ineffective due to political infighting.

An accord between northern and southern leaders was signed in

Amman

Amman ( , ; , ) is the capital and the largest city of Jordan, and the country's economic, political, and cultural center. With a population of four million as of 2021, Amman is Jordan's primate city and is the largest city in the Levant ...

,

Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

on 20 February 1994, but this could not stop the civil war. During these tensions, both the northern and southern armies (which had never integrated) gathered on their respective frontiers.

Contemporary Yemen

Ali Abdullah Saleh

Ali Abdullah Saleh became Yemen's first directly elected president in

the 1999 presidential election, winning 96% of the vote.

The only other candidate,

Najeeb Qahtan Al-Sha'abi, was the son of Qahtan Muhammad al-Sha'abi, a former president of South Yemen. Though a member of Saleh's

General People's Congress (GPC) party, Najeeb ran as an independent.

In October 2000, 17 U.S. personnel died after an al-Qaeda

suicide attack on the U.S. naval vessel USS ''Cole'' in

Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

. After the

September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, also known as 9/11, were four coordinated Islamist terrorist suicide attacks by al-Qaeda against the United States in 2001. Nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial airliners, crashing the first two into ...

on the United States, President Saleh assured U.S. President

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

that Yemen was a partner in his

War on Terror. In 2001, violence surrounded

a referendum, which apparently supported extending Saleh's rule and powers.

The

Houthi insurgency in Yemen began in June 2004 when dissident cleric

Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi, head of the Zaidi Shia sect, launched an uprising against the Yemeni government. The Yemeni government alleged that the

Houthis were seeking to overthrow it and to implement ''Shī'ite''

religious law

Religious law includes ethical and moral codes taught by religious traditions. Examples of religiously derived legal codes include Christian canon law (applicable within a wider theological conception in the church, but in modern times distin ...

. The rebels countered that they were "defending their community against discrimination" and government aggression.

In 2005, at least 36 people were killed in clashes across the country between police and protesters over rising fuel prices. In the

2006 presidential election, Saleh won with 77% of the vote. His main rival,

Faisal bin Shamlan, received 22%.

Saleh was sworn in for another term on 27 September.

A suicide bomber killed eight Spanish tourists and two Yemenis in the

Marib Governorate in July 2007. A series of bomb attacks occurred on police, official, diplomatic, foreign business, and tourism targets in 2008. Car bombings outside the U.S. embassy in Sana'a killed 18 people, including six of the assailants in September 2008. In 2008, an opposition rally in Sana'a demanding electoral reform was met with police gunfire.

Revolution and aftermath

The 2011

Yemeni revolution

The Yemeni revolution (or Yemeni intifada) followed the initial stages of the Tunisian revolution and occurred simultaneously with the 2011 Egyptian revolution and other Arab Spring, Arab Spring protests in the Middle East and North Africa. ...

followed other

Arab Spring mass protests in early 2011. The uprising was initially against unemployment, economic conditions, and corruption, as well as against the government's proposals to modify the

so that Saleh's son could inherit the presidency.

In March 2011, police snipers opened fire on a pro-democracy camp in Sana'a, killing more than 50 people. In May, dozens were killed in clashes between troops and tribal fighters in Sana'a. By this point, Saleh began to lose international support. In October 2011, Yemeni human rights activist

Tawakul Karman won the

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

, and the

UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

condemned the violence and called for a transfer of power. On 23 November 2011, Saleh flew to

Riyadh

Riyadh is the capital and largest city of Saudi Arabia. It is also the capital of the Riyadh Province and the centre of the Riyadh Governorate. Located on the eastern bank of Wadi Hanifa, the current form of the metropolis largely emerged in th ...

, in neighbouring Saudi Arabia, to sign the

Gulf Co-operation Council plan for political transition, which he had previously spurned. Upon signing the document, he agreed to legally transfer the office and powers of the presidency to his deputy, Vice President

Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi.

Hadi took office for a two-year term upon winning the uncontested presidential elections in February 2012.

A unity government—including a prime minister from the opposition—was formed. Al-Hadi would oversee the drafting of a new constitution, followed by parliamentary and presidential elections in 2014. Saleh returned in February 2012. In the face of objections from thousands of street protesters, parliament granted him full immunity from prosecution. Saleh's son, General

Ahmed Ali Abdullah Saleh, continues to exercise a strong hold on sections of the military and security forces.

AQAP claimed responsibility for a February 2012 suicide attack on the presidential palace that killed 26 Republican Guards on the day that President Hadi was sworn in. AQAP was also behind a suicide bombing that killed 96 soldiers in Sana'a three months later. In September 2012, a car bomb attack in Sana'a killed 11 people, a day after a local al-Qaeda leader

Said al-Shihri was reported killed in the south.

By 2012, there was a "small contingent of U.S. special-operations troops"—in addition to CIA and "unofficially acknowledged" U.S. military presence—in response to increasing terror attacks by AQAP on Yemeni citizens. Many analysts have pointed out the former Yemeni government role in cultivating terrorist activity in the country. Following the election of President

Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, the Yemeni military was able to push

Ansar al-Sharia back and recapture the

Shabwah Governorate.

The central government in Sana'a remained weak, staving off challenges from

southern separatists and Houthis as well as AQAP. The

Houthi insurgency intensified after Hadi took power, escalating in September 2014 as anti-government forces led by

Abdul-Malik al-Houthi

Abdul-Malik Badr al-Din al-Houthi (born 22 May 1979) is a Yemeni politician and religious leader who is the second leader of the Houthis (Ansar Allah), an organization principally made up of Zaydi Shia Muslims, since 2004.

His brothers, Yahi ...

swept into the capital and forced Hadi to agree to a "unity" government. The Houthis then refused to participate in the government, although they continued to apply pressure on Hadi and his ministers, even shelling the president's private residence and placing him under house arrest, until the government's mass resignation in January 2015. The following month, the Houthis dissolved parliament and

declared that a

Revolutionary Committee under

Mohammed Ali al-Houthi was the interim authority in Yemen. Abdul-Malik al-Houthi, a cousin of the acting president, called the takeover a "glorious revolution". However, the "constitutional declaration" of 6 February 2015 was widely rejected by opposition politicians and foreign governments, including the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

.

Hadi managed to flee from Sana'a to Aden, his hometown and stronghold in the south, on 21 February 2015. He promptly gave a televised speech rescinding his resignation, condemning the coup, and calling for recognition as the constitutional president of Yemen.

The following month, Hadi declared Aden Yemen's "temporary" capital.

The Houthis, however, rebuffed an initiative by the

Gulf Cooperation Council

The Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (), also known as the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC; ), is a Regional integration, regional, intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental, political, and economic union comprising Ba ...

and continued to move south toward Aden. All U.S. personnel were evacuated, and President Hadi was forced to flee the country to Saudi Arabia. On 26 March 2015, Saudi Arabia announced

Operation Decisive Storm and began airstrikes and announced its intentions to lead a military coalition against the Houthis, who they claimed were being aided by Iran and began a force buildup along the Yemeni border. The coalition included the

United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE), or simply the Emirates, is a country in West Asia, in the Middle East, at the eastern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is a Federal monarchy, federal elective monarchy made up of Emirates of the United Arab E ...

,

Kuwait

Kuwait, officially the State of Kuwait, is a country in West Asia and the geopolitical region known as the Middle East. It is situated in the northern edge of the Arabian Peninsula at the head of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to Iraq–Kuwait ...

,

Qatar

Qatar, officially the State of Qatar, is a country in West Asia. It occupies the Geography of Qatar, Qatar Peninsula on the northeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in the Middle East; it shares Qatar–Saudi Arabia border, its sole land b ...

,

Bahrain

Bahrain, officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, is an island country in West Asia. Situated on the Persian Gulf, it comprises a small archipelago of 50 natural islands and an additional 33 artificial islands, centered on Bahrain Island, which mak ...

,

Jordan

Jordan, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, is a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia. Jordan is bordered by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the south, and Israel and the occupied Palestinian ter ...

,

Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

,

Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

,

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, and

Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

. The United States announced that it was assisting with intelligence, targeting, and logistics. After Hadi troops took control of Aden from Houthis, jihadist groups became active in the city, and some terrorist incidents were linked to them such as

Missionaries of Charity attack in Aden on 4 March 2016. In February 2018, Aden was

seized by the UAE-backed separatist

Southern Transitional Council.

Yemen has been suffering from a