The influence and

imperialism

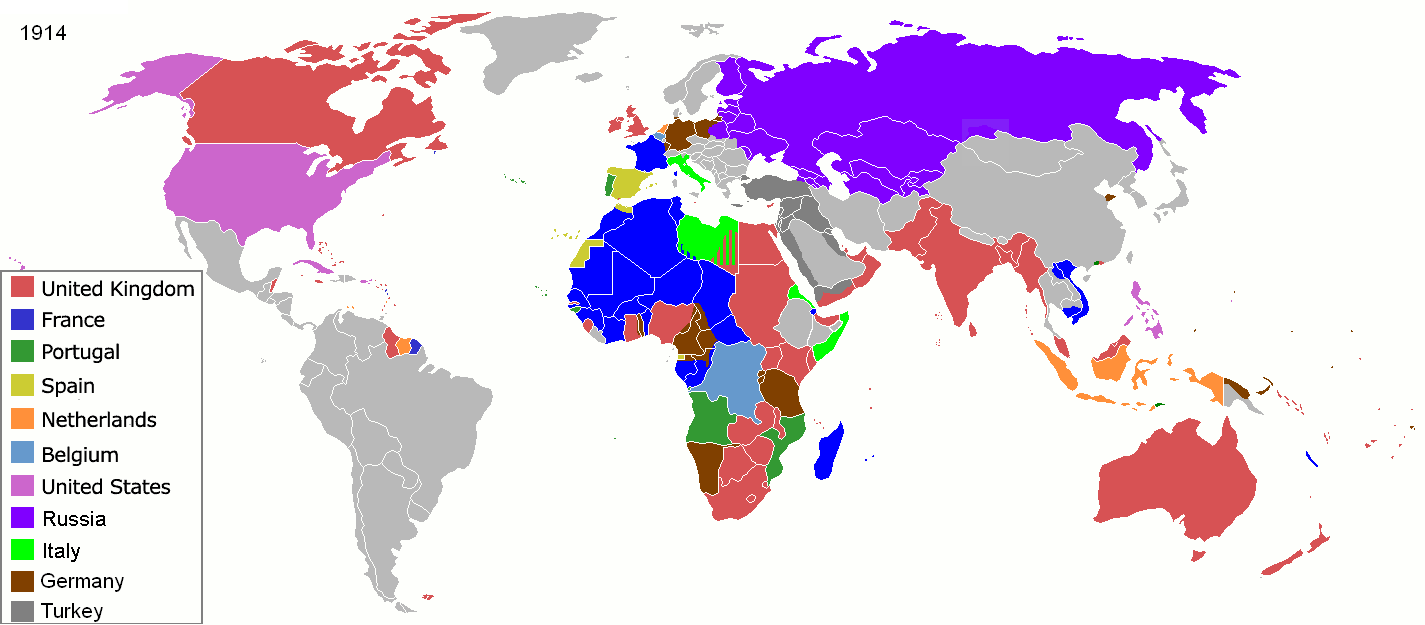

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

of the

West

West is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some Romance langu ...

peaked in Asian territories from the

colonial period beginning in the 16th century, and substantially reduced with 20th century

decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

. It originated in the 15th-century search for

trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over land or water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a singl ...

s to the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

and

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

, in response to

Ottoman control of the

Silk Road

The Silk Road was a network of Asian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over , it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the ...

. This led to the

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

, and introduction of

early modern warfare

Early modern warfare is the era of warfare during early modern period following medieval warfare. It is associated with the start of the widespread use of gunpowder and the development of suitable weapons to use the explosive, including art ...

into what Europeans first called the

East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

, and later the

Far East

The Far East is the geographical region that encompasses the easternmost portion of the Asian continent, including North Asia, North, East Asia, East and Southeast Asia. South Asia is sometimes also included in the definition of the term. In mod ...

. By the 16th century, the

Age of Sail

The Age of Sail is a period in European history that lasted at the latest from the mid-16th (or mid-15th) to the mid-19th centuries, in which the dominance of sailing ships in global trade and warfare culminated, particularly marked by the int ...

expanded European influence and development of the

spice trade under colonialism. European-style

colonial empire

A colonial empire is a sovereign state, state engaging in colonization, possibly establishing or maintaining colony, colonies, infused with some form of coloniality and colonialism. Such states can expand contiguous as well as Territory#Overseas ...

s and imperialism operated in Asia throughout six centuries of colonialism, formally ending with the independence of

Portuguese Macau

Macau was under Portuguese Empire, Portuguese rule from the establishment of the first official Portuguese settlement in 1557 until its Handover of Macau, handover to China in 1999. It comprised the Municipality of Macau and the Municipality of ...

in 1999. The empires introduced Western concepts of

nation

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective Identity (social science), identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, t ...

and the

multinational state

A multinational state or a multinational union is a sovereign entity that comprises two or more nations or states. This contrasts with a nation state, where a single nation accounts for the bulk of the population. Depending on the definition of ...

.

European political power, commerce, and culture in Asia gave rise to growing trade in

commodities

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that specifically has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

Th ...

—a key development in the rise of the

free market

In economics, a free market is an economic market (economics), system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of ...

economy. In the 16th century, the Portuguese broke the monopoly of the Arabs and Italians in trade between Asia and Europe by its

discovery of the sea route to India around the Cape of Good Hope. The ensuing rise of the rival

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

gradually eclipsed Portuguese influence in Asia. Dutch forces first established independent bases in the East and between 1640-60 wrested

Malacca

Malacca (), officially the Historic State of Malacca (), is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state in Malaysia located in the Peninsular Malaysia#Other features, southern region of the Malay Peninsula, facing the Strait of Malacca ...

,

Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, some southern Indian ports, and the lucrative

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

trade from the Portuguese. The English and French established settlements in India and trade with China and their acquisitions surpassed the Dutch. After the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

in 1763, the British eliminated French influence in India and established the

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

as the most important political force on the

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

.

Before the 19th century

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, demand for oriental goods such as

porcelain

Porcelain (), also called china, is a ceramic material made by heating Industrial mineral, raw materials, generally including kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The greater strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to oth ...

,

silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

,

spice

In the culinary arts, a spice is any seed, fruit, root, Bark (botany), bark, or other plant substance in a form primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of pl ...

s, and

tea remained the driving force behind European imperialism. The European stake in Asia was confined largely to trading stations and outposts necessary to protect trade. Industrialization, however, dramatically increased European demand for Asian raw materials. The 1870s

Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in Panic of 1873, 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1899, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been e ...

provoked a scramble for new markets for Western European products and services in Africa, the Americas, Eastern Europe, and especially Asia. This coincided with an era known as "the

New Imperialism

In History, historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of Colonialism, colonial expansion by European powers, the American imperialism, United States, and Empire of Japan, Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. ...

", which saw a shift in focus from trade and

indirect rule

Indirect rule was a system of public administration, governance used by imperial powers to control parts of their empires. This was particularly used by colonial empires like the British Empire to control their possessions in Colonisation of Afri ...

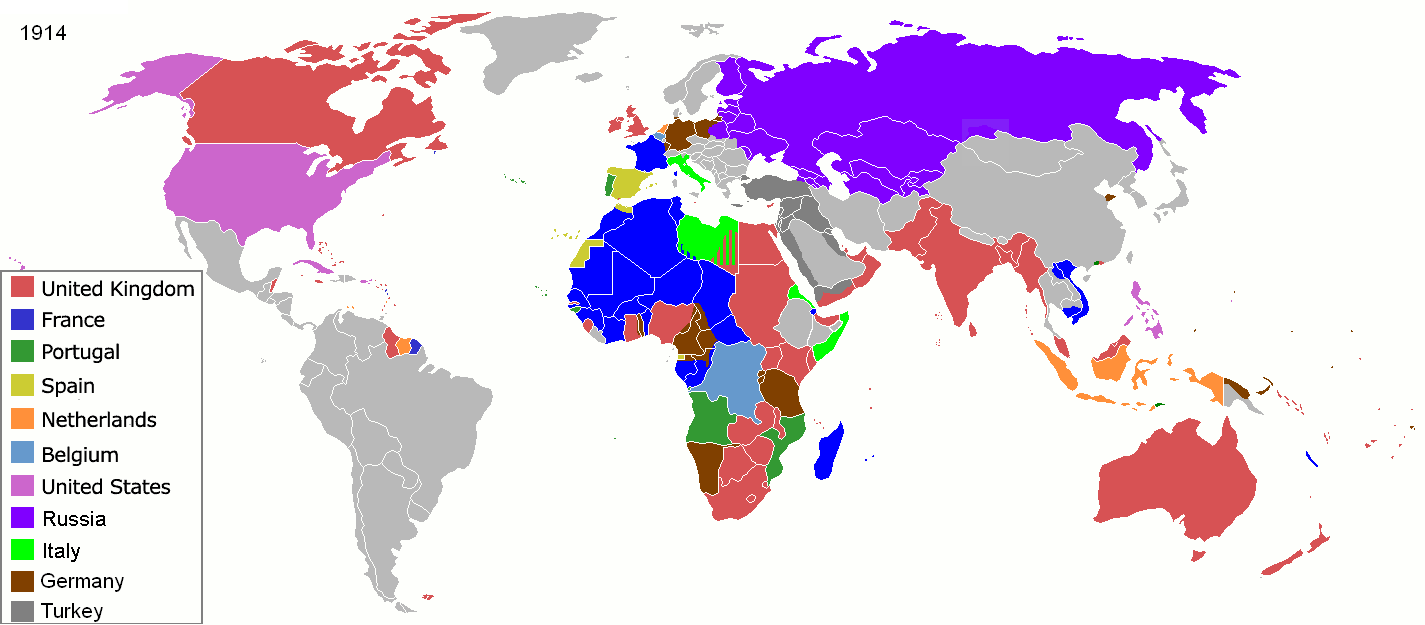

to colonial control of large overseas territories as political extensions of their mother countries. Between the 1870s and World War I in 1914, the UK, Netherlands and France—the established colonial powers in Asia—added to their empires in the

Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, Indian Subcontinent, and

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

. The

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

following the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

; the

German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

after the

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

in 1871;

Tsarist Russia; and the US following the

Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

in 1898, emerged as new imperial powers in

East Asia

East Asia is a geocultural region of Asia. It includes China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan, plus two special administrative regions of China, Hong Kong and Macau. The economies of Economy of China, China, Economy of Ja ...

and the

Pacific Ocean area.

In Asia, the World Wars were played out as struggles among imperial powers, with conflicts involving the European powers along with Russia and the rising American and Japanese. None of the colonial powers however, possessed the resources to withstand the strains of both wars and maintain their direct rule in Asia. Although nationalist movements throughout the colonial world led to the political independence of nearly all of Asia's remaining colonies,

decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

was intercepted by the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. Southeast Asia,

South Asia

South Asia is the southern Subregion#Asia, subregion of Asia that is defined in both geographical and Ethnicity, ethnic-Culture, cultural terms. South Asia, with a population of 2.04 billion, contains a quarter (25%) of the world's populatio ...

, the Middle East, and East Asia remained embedded in a world economic, financial, and military system in which the great powers competed to extend their influence. However, the rapid post-war economic development and rise of the

industrialized developed countries

A developed country, or advanced country, is a sovereign state that has a high quality of life, developed economy, and advanced technological infrastructure relative to other less industrialized nations. Most commonly, the criteria for eval ...

of

Republic of China on Taiwan,

Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

,

South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

,

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

and the developing countries of India, China, along with the collapse of the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, have greatly diminished European influence in Asia. The US remains influential with trade and military bases in Asia.

Early European exploration of Asia

European exploration of Asia started in

ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

times along the

Silk Road

The Silk Road was a network of Asian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over , it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the ...

. The Romans had knowledge of lands as distant as China. Trade with India through the Roman Egyptian

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

ports was significant in the first centuries of the

Common Era

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the ...

.

Medieval European exploration of Asia

In the 13th and 14th centuries, a number of Europeans, many of them Christian

missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Miss ...

, had sought to penetrate into China. The most famous of these travelers was

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

. But these journeys had little permanent effect on east–west trade because of a series of political developments in Asia in the last decades of the 14th century, which put an end to further European exploration of Asia. The

Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

in China, which had been receptive to European missionaries and merchants, was overthrown, and the new

Ming rulers were found to be unreceptive of religious proselytism. Meanwhile, the

Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks () were a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group in Anatolia. Originally from Central Asia, they migrated to Anatolia in the 13th century and founded the Ottoman Empire, in which they remained socio-politically dominant for the e ...

consolidated control over the eastern

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

, closing off key overland trade routes. Thus, until the 15th century, only minor trade and cultural exchanges between Europe and Asia continued at certain terminals controlled by Muslim traders.

Oceanic voyages to Asia

Western European rulers determined to find new trade routes of their own. The Portuguese spearheaded the drive to find oceanic routes that would provide cheaper and easier access to South and East Asian goods. This chartering of oceanic routes between East and West began with the unprecedented voyages of Portuguese and Spanish sea captains. Their voyages were influenced by medieval European adventurers, who had journeyed overland to the Far East and contributed to geographical knowledge of parts of Asia upon their return.

In 1488,

Bartolomeu Dias

Bartolomeu Dias ( – 29 May 1500) was a Portuguese mariner and explorer. In 1488, he became the first European navigator to round the Cape Agulhas, southern tip of Africa and to demonstrate that the most effective southward route for ships lies ...

rounded the southern tip of Africa under the sponsorship of Portugal's

John II, from which point he noticed that the coast swung northeast (

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

). While Dias' crew forced him to turn back, by 1497, Portuguese navigator

Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama ( , ; – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and nobleman who was the Portuguese discovery of the sea route to India, first European to reach India by sea.

Da Gama's first voyage (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

made the first open voyage from Europe to India. In 1520,

Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese navigator in the service of the

Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Kingdom of Castile, Castile and Kingd ...

('

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

'), found a sea route into the

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

.

Portuguese and Spanish trade and colonization in Asia

Portuguese monopoly over trade in the Indian Ocean and Asia

In 1509, the Portuguese under

Francisco de Almeida won the decisive

battle of Diu against a joint

Mamluk

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-so ...

and Arab fleet sent to expel the Portuguese of the Arabian Sea. The victory enabled Portugal to implement its strategy of controlling the Indian Ocean.

Early in the 16th century,

Afonso de Albuquerque emerged as the Portuguese colonial viceroy most instrumental in consolidating Portugal's holdings in Africa and in Asia. He understood that Portugal could wrest commercial supremacy from the Arabs only by force, and therefore devised a plan to establish forts at strategic sites which would dominate the trade routes and also protect Portuguese interests on land. In 1510, he

conquered Goa in India, which enabled him to gradually consolidate control of most of the commercial traffic between Europe and Asia, largely through trade; Europeans started to carry on trade from forts, acting as foreign merchants rather than as settlers. In contrast, early European expansion in the "

West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

", (later known to Europeans as a separate continent from Asia that they would call the "

Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

") following the 1492 voyage of

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

, involved heavy settlement in colonies that were treated as political extensions of the mother countries.

Lured by the potential of high profits from another expedition, the Portuguese established a permanent base in

Cochin

Kochi ( , ), formerly known as Cochin ( ), is a major port city along the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea. It is part of the district of Ernakulam in the state of Kerala. The city is also commonly referred to as Ernaku ...

, south of the Indian trade port of

Calicut in the early 16th century. In 1510, the Portuguese, led by

Afonso de Albuquerque, seized Goa on the coast of India, which

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

held until 1961, along with

Diu and

Daman (the remaining territory and enclaves in India from a former network of coastal towns and smaller fortified trading ports added and abandoned or lost centuries before). The Portuguese soon acquired a monopoly over trade in the Indian Ocean.

Portuguese viceroy Albuquerque (1509–1515) resolved to consolidate Portuguese holdings in Africa and Asia, and secure control of trade with the

East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

and China. His first objective was

Malacca

Malacca (), officially the Historic State of Malacca (), is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state in Malaysia located in the Peninsular Malaysia#Other features, southern region of the Malay Peninsula, facing the Strait of Malacca ...

, which controlled the narrow strait through which most Far Eastern trade moved.

Captured in 1511, Malacca became the springboard for further eastward penetration, starting with the voyage of

António de Abreu

Antonio is a masculine given name of Etruscan origin deriving from the root name Antonius. It is a common name among Romance language–speaking populations as well as the Balkans and Lusophone Africa. It has been among the top 400 most popul ...

and

Francisco Serrão in 1512, ordered by Albuquerque, to the Moluccas. Years later the first trading posts were established in the

Moluccas

The Maluku Islands ( ; , ) or the Moluccas ( ; ) are an archipelago in the eastern part of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located in West Melanesi ...

, or "Spice Islands", which was the source for some of the world's most hotly demanded spices, and from there, in

Makassar

Makassar ( ), formerly Ujung Pandang ( ), is the capital of the Indonesian Provinces of Indonesia, province of South Sulawesi. It is the largest city in the region of Eastern Indonesia and the country's fifth-largest urban center after Jakarta, ...

and some others, but smaller, in the

Lesser Sunda Islands

The Lesser Sunda Islands (, , ), now known as Nusa Tenggara Islands (, or "Southeast Islands"), are an archipelago in the Indonesian archipelago. Most of the Lesser Sunda Islands are located within the Wallacea region, except for the Bali pro ...

. By 1513–1516, the first Portuguese ships had reached

Canton on the southern coasts of China.

In 1513, after the failed attempt to conquer

Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

, Albuquerque entered with an armada, for the first time for Europeans by the ocean via, on the

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

; and in 1515, Albuquerque consolidated the Portuguese hegemony in the

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

gates, already begun by him in 1507, with the domain of

Muscat

Muscat (, ) is the capital and most populous city in Oman. It is the seat of the Governorate of Muscat. According to the National Centre for Statistics and Information (NCSI), the population of the Muscat Governorate in 2022 was 1.72 million. ...

and

Ormuz. Shortly after, other fortified bases and forts were annexed and built along the Gulf, and in 1521, through a military campaign, the Portuguese annexed

Bahrain

Bahrain, officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, is an island country in West Asia. Situated on the Persian Gulf, it comprises a small archipelago of 50 natural islands and an additional 33 artificial islands, centered on Bahrain Island, which mak ...

.

The Portuguese conquest of Malacca triggered the

Malayan–Portuguese war. In 1521,

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

China defeated the Portuguese at the

Battle of Tunmen and then defeated the Portuguese again at the

Battle of Xicaowan. The Portuguese tried to establish trade with China by illegally smuggling with the pirates on the offshore islands off the coast of

Zhejiang

)

, translit_lang1_type2 =

, translit_lang1_info2 = ( Hangzhounese) ( Ningbonese) (Wenzhounese)

, image_skyline = 玉甑峰全貌 - panoramio.jpg

, image_caption = View of the Yandang Mountains

, image_map = Zhejiang i ...

and

Fujian

Fujian is a provinces of China, province in East China, southeastern China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its capital is Fuzhou and its largest prefe ...

, but they were driven away by the

Ming navy in the 1530s-1540s.

In 1557, China decided to lease

Macau

Macau or Macao is a special administrative regions of China, special administrative region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). With a population of about people and a land area of , it is the most List of countries and dependencies by p ...

to the Portuguese as a place where they could dry goods they transported on their ships, which they held until 1999. The Portuguese, based at Goa and Malacca, had now established a lucrative maritime empire in the Indian Ocean meant to monopolize the

spice trade

The spice trade involved historical civilizations in Asia, Northeast Africa and Europe. Spices, such as cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, pepper, nutmeg, star anise, clove, and turmeric, were known and used in antiquity and traded in t ...

. The Portuguese also began a channel of trade with the Japanese, becoming the first recorded Westerners to have visited Japan. This contact introduced Christianity and firearms into Japan.

In 1505, (also possibly before, in 1501), the Portuguese, through

Lourenço de Almeida

Lourenço de Almeida ( – March 1508) was a Portuguese explorer and military commander.

He was born in Martim, Portugal, the son of Francisco de Almeida, first viceroy of Portuguese India. Acting under his father, Lourenço distinguished hims ...

, the son of Francisco de Almeida, reached

Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

. The Portuguese founded a fort at the city of

Colombo

Colombo, ( ; , ; , ), is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million, and 752,993 within the municipal limits. It is the ...

in 1517 and gradually extended their control over the coastal areas and inland. In a series of military conflicts and political maneuvers, the Portuguese extended their control over the

Sinhalese kingdoms, including

Jaffna

Jaffna (, ; , ) is the capital city of the Northern Province, Sri Lanka, Northern Province of Sri Lanka. It is the administrative headquarters of the Jaffna District located on a Jaffna Peninsula, peninsula of the same name. With a population o ...

(1591),

Raigama (1593),

Sitawaka (1593), and

Kotte (1594)- However, the aim of unifying the entire island under Portuguese control faced the

Kingdom of Kandy`s fierce resistance.

The Portuguese, led by

Pedro Lopes de Sousa, launched a full-scale military invasion of the kingdom of Kandy in the

Campaign of Danture of 1594. The invasion was a disaster for the Portuguese, with their entire army wiped out by Kandyan

guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

.

, romantically celebrated in the 17th century Sinhalese Epic (also for its greater humanism and tolerance compared to other governors) led the last military operation that also ended in disaster. He died in the

Battle of Randeniwela, refusing to abandon his troops in the face of total annihilation.

The energies of Castile (later, the ''unified'' Spain), the other major colonial power of the 16th century, were largely concentrated on the Americas, not South and East Asia, but the Spanish did establish a footing in the Far East in the Philippines. After fighting with the Portuguese by the Spice Islands since 1522 and the agreement between the two powers in 1529 (in the treaty of Zaragoza), the Spanish, led by

Miguel López de Legazpi

Miguel López de Legazpi (12 June 1502 – 20 August 1572), also known as ''Adelantado, El Adelantado'' and ''El Viejo'' (The Elder), was a Spanish conquistador who financed and led an expedition to conquer the Philippines, Philippine islan ...

, settled and conquered gradually the Philippines since 1564. After the discovery of the return voyage to the Americas by

Andres de Urdaneta

Andres or Andrés may refer to:

*Andres, Illinois, an unincorporated community in Will County, Illinois, US

*Andres, Pas-de-Calais, a commune in Pas-de-Calais, France

*Andres (name)

*Hurricane Andres

* "Andres" (song), a 1994 song by L7

See also ...

in 1565, cargoes of Chinese goods were transported from the

Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

to

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

and from there to

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. By this long route, Spain reaped some of the profits of Far Eastern commerce. Spanish officials converted the islands to Christianity and established some settlements, permanently establishing the Philippines as the area of East Asia most oriented toward the West in terms of culture and commerce. The Moro Muslims fought against the Spanish for over three centuries in the

Spanish–Moro conflict.

Decline of Portugal's Asian empire since the 17th century

The lucrative trade was vastly expanded when the Portuguese began to export

slave

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

s from Africa in 1541; however, over time, the rise of the slave trade left Portugal over-extended, and vulnerable to competition from other Western European powers. Envious of Portugal's control of trade routes, other Western European nations—mainly the

Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, France, and England—began to send in rival expeditions to Asia. In 1642, the Dutch drove the Portuguese out of the

Gold Coast in Africa, the source of the bulk of Portuguese slave laborers, leaving this rich slaving area to other Europeans, especially the Dutch and the English.

Rival European powers began to make inroads in Asia as the Portuguese and Spanish trade in the Indian Ocean declined primarily because they had become hugely over-stretched financially due to the limitations on their investment capacity and contemporary naval technology. Both of these factors worked in tandem, making control over Indian Ocean trade extremely expensive.

The existing Portuguese interests in Asia proved sufficient to finance further colonial expansion and entrenchment in areas regarded as of greater strategic importance in

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

and

Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

. Portuguese maritime supremacy was lost to the Dutch in the 17th century, and with this came serious challenges for the Portuguese. However, they still clung to Macau and settled a new colony on the island of

Timor

Timor (, , ) is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is Indonesia–Timor-Leste border, divided between the sovereign states of Timor-Leste in the eastern part and Indonesia in the ...

. It was as recent as the 1960s and 1970s that the Portuguese began to relinquish their colonies in Asia. Goa was invaded by India in 1961 and became an Indian state in 1987;

Portuguese Timor was abandoned in 1975 and was then invaded by

Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

. It became an independent country in 2002, and Macau was handed back to the Chinese as per a treaty in 1999.

Holy wars

The arrival of the Portuguese and Spanish and their holy wars against Muslim states in the

Malayan–Portuguese war,

Spanish–Moro conflict and

Castilian War

The Castilian War, also called the Spanish Expedition to Borneo, was a conflict between the Spanish Empire and several Muslim states in Southeast Asia, including the Sultanates of Brunei, Sulu, and Maguindanao. It is also considered as part of ...

inflamed religious tensions and turned Southeast Asia into an arena of conflict between Muslims and Christians. The Brunei Sultanate's capital at Kota Batu was assaulted by Governor Sande who led the 1578 Spanish attack.

The word "savages" in Spanish, cafres, was from the word "infidel" in Arabic - Kafir, and was used by the Spanish to refer to their own "Christian savages" who were arrested in Brunei. It was said ''Castilians are kafir, men who have no souls, who are condemned by fire when they die, and that too because they eat pork'' by the Brunei Sultan after the term ''accursed doctrine'' was used to attack Islam by the Spaniards which fed into hatred between Muslims and Christians sparked by their 1571 war against Brunei.

The Sultan's words were in response to insults coming from the Spanish at Manila in 1578, other Muslims from Champa, Java, Borneo, Luzon, Pahang, Demak, Aceh, and the Malays echoed the rhetoric of holy war against the Spanish and Iberian Portuguese, calling them kafir enemies which was a contrast to their earlier nuanced views of the Portuguese in the Hikayat Tanah Hitu and Sejarah Melayu.

The war by Spain against Brunei was defended in an apologia written by Doctor De Sande.

The British eventually partitioned and took over Brunei while Sulu was attacked by the British, Americans, and Spanish which caused its breakdown and downfall after both of them thrived from 1500 to 1900 for four centuries.

Dar al-Islam was seen as under invasion by "kafirs" by the Atjehnese led by Zayn al-din and by Muslims in the Philippines as they saw the Spanish invasion, since the Spanish brought the idea of a crusader holy war against Muslim Moros just as the Portuguese did in Indonesia and India against what they called "Moors" in their political and commercial conquests which they saw through the lens of religion in the 16th century.

In 1578, an attack was launched by the Spanish against Jolo, and in 1875 it was destroyed at their hands, and once again in 1974 it was destroyed by the Philippines.

The Spanish first set foot on Borneo in Brunei.

The Spanish war against Brunei failed to conquer Brunei but it totally cut off the Philippines from Brunei's influence, the Spanish then started colonizing Mindanao and building fortresses. In response, the Bisayas, where Spanish forces were stationed, were subjected to retaliatory attacks by the Magindanao in 1599-1600 due to the Spanish attacks on Mindanao.

The Brunei royal family was related to the Muslim Rajahs who in ruled the principality in 1570 of Manila (

Kingdom of Maynila) and this was what the Spaniards came across on their initial arrival to Manila, Spain uprooted Islam out of areas where it was shallow after they began to force Christianity on the Philippines in their conquests after 1521 while Islam was already widespread in the 16th century Philippines. In the Philippines in the Cebu islands the natives killed the Spanish fleet leader Magellan. Borneo's western coastal areas at Landak, Sukadana, and Sambas saw the growth of Muslim states in the sixteenth century, in the 15th century at Nanking, the capital of China, the death and burial of the Borneo Bruneian king Maharaja Kama took place upon his visit to China with Zheng He's fleet.

The Spanish were expelled from Brunei in 1579 after they attacked in 1578.

There were fifty thousand inhabitants before the 1597 attack by the Spanish in Brunei.

During first contact with China, numerous aggressions and provocations were undertaken by the Portuguese

They believed they could mistreat the non-Christians because they themselves were Christians and acted in the name of their religion in committing crimes and atrocities.

This resulted in the

Battle of Xicaowan where the local Chinese navy defeated and captured a fleet of Portuguese caravels.

Dutch trade and colonization in Asia

Rise of Dutch control over Asian trade in the 17th century

The Portuguese decline in Asia was accelerated by attacks on their commercial empire by the Dutch and the English, which began a global struggle over the empire in Asia that lasted until the end of the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

in 1763. The

Netherlands revolt against Spanish rule facilitated Dutch encroachment on the Portuguese monopoly over South and East Asian trade. The Dutch looked on Spain's trade and colonies as potential spoils of war. When the two crowns of the Iberian peninsula were joined in 1581, the Dutch felt free to attack Portuguese territories in Asia.

By the 1590s, a number of Dutch companies were formed to finance trading expeditions in Asia. Because competition lowered their profits, and because of the doctrines of

mercantilism

Mercantilism is a economic nationalism, nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources ...

, in 1602 the companies united into a

cartel

A cartel is a group of independent market participants who collaborate with each other as well as agreeing not to compete with each other in order to improve their profits and dominate the market. A cartel is an organization formed by producers ...

and formed the

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

, and received from the government the right to trade and colonize territory in the area stretching from the

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

eastward to the

Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago to the south. Considered the most important natura ...

.

In 1605, armed Dutch merchants captured the Portuguese fort at

Amboyna in the Moluccas, which was developed into the company's first secure base. Over time, the Dutch gradually consolidated control over the great trading ports of the East Indies. This control allowed the company to monopolise the world

spice trade

The spice trade involved historical civilizations in Asia, Northeast Africa and Europe. Spices, such as cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, pepper, nutmeg, star anise, clove, and turmeric, were known and used in antiquity and traded in t ...

for decades. Their monopoly over the spice trade became complete after they drove the Portuguese from

Malacca

Malacca (), officially the Historic State of Malacca (), is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state in Malaysia located in the Peninsular Malaysia#Other features, southern region of the Malay Peninsula, facing the Strait of Malacca ...

in 1641 and

Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

in 1658.

Dutch East India Company colonies or outposts were later established in Atjeh (

Aceh

Aceh ( , ; , Jawi script, Jawoë: ; Van Ophuijsen Spelling System, Old Spelling: ''Atjeh'') is the westernmost Provinces of Indonesia, province of Indonesia. It is located on the northern end of Sumatra island, with Banda Aceh being its capit ...

), 1667;

Macassar, 1669; and

Bantam, 1682. The company established its headquarters at

Batavia (today

Jakarta

Jakarta (; , Betawi language, Betawi: ''Jakartè''), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta (; ''DKI Jakarta'') and formerly known as Batavia, Dutch East Indies, Batavia until 1949, is the capital and largest city of Indonesia and ...

) on the island of

Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

. Outside the East Indies, the Dutch East India Company colonies or outposts were also established in

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

(

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

),

Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

(now

Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

and part of India),

Mauritius

Mauritius, officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island country in the Indian Ocean, about off the southeastern coast of East Africa, east of Madagascar. It includes the main island (also called Mauritius), as well as Rodrigues, Ag ...

(1638-1658/1664-1710),

Siam (now

Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

),

Guangzhou

Guangzhou, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Canton or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, southern China. Located on the Pearl River about nor ...

(Canton, China),

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

(1624–1662), and southern India (1616–1795).

Ming dynasty China defeated the Dutch East India Company in the

Sino-Dutch conflicts. The Chinese first

defeated and drove the Dutch out of the Pescadores in 1624. The Ming navy under

Zheng Zhilong defeated the Dutch East India Company's fleet at the 1633

Battle of Liaoluo Bay. In 1662, Zheng Zhilong's son

Zheng Chenggong (also known as Koxinga) expelled the Dutch from Taiwan after defeating them in the

siege of Fort Zeelandia. (''see''

History of Taiwan

The history of the island of Taiwan dates back tens of thousands of years to the earliest known evidence of human habitation. The sudden appearance of a culture based on agriculture around 3000 BC is believed to reflect the arrival of the ancest ...

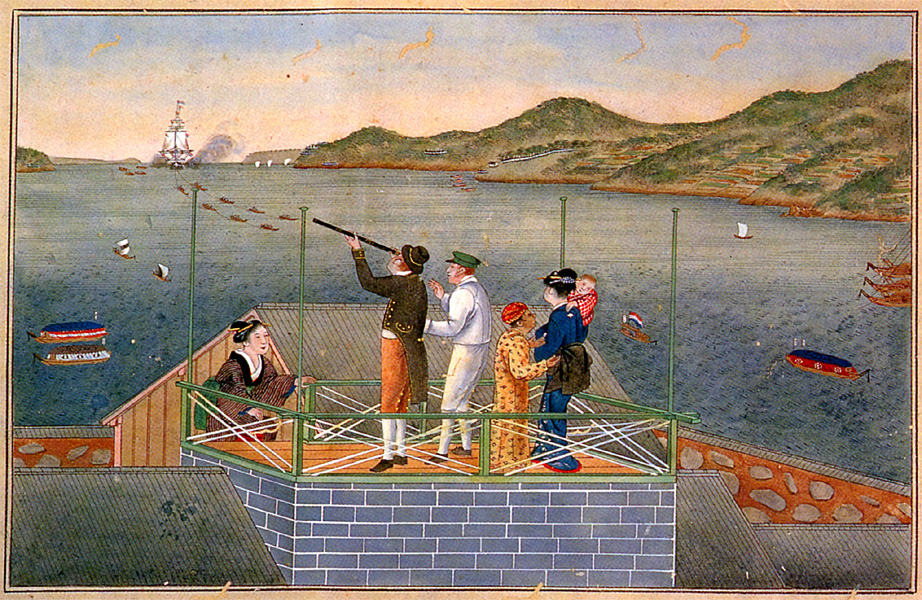

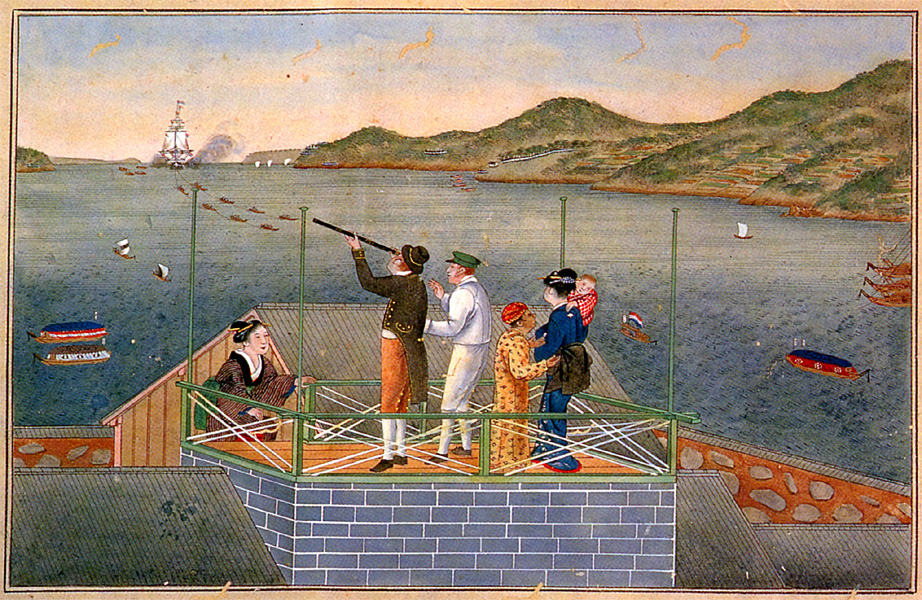

) Further, the Dutch East India Company trade post on

Dejima

or Deshima, in the 17th century also called , was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan, that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1858). For 220 years, it was the central con ...

(1641–1857), an artificial island off the coast of

Nagasaki

, officially , is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese, the port of Portuguese_Nagasaki, Nagasaki became the sole Nanban trade, port used for tr ...

, was for a long time the only place where Europeans could trade with Japan.

The Vietnamese

Nguyễn lords

The Nguyễn lords (, 主阮; 1558–1777, 1780–1802), also known as the Nguyễn clan (; ), were Nguyễn dynasty's forerunner and a feudal noble clan ruling southern Đại Việt in the Revival Lê dynasty. The Nguyễn lords were membe ...

defeated the Dutch

in a naval battle in 1643.

The Cambodians defeated the Dutch in the

Cambodian–Dutch War in 1644.

In 1652,

Jan van Riebeeck

Johan Anthoniszoon "Jan" van Riebeeck (21 April 1619 – 18 January 1677) was a Dutch navigator, ambassador and colonial administrator of the Dutch East India Company.

Life

Early life

Jan van Riebeeck was born in Culemborg on 21 April ...

established an outpost at the

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

(the southwestern tip of Africa, currently in

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

) to restock company ships on their journey to East Asia. This post later became a fully-fledged colony, the

Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

(1652–1806). As Cape Colony attracted increasing Dutch and European settlement, the Dutch founded the city of Kaapstad (

Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

).

By 1669, the Dutch East India Company was the richest private company in history, with a huge fleet of merchant ships and warships, tens of thousands of employees, a private army consisting of thousands of soldiers, and a reputation on the part of its stockholders for high dividend payments.

Dutch New Imperialism in Asia

The company was in almost constant conflict with the English; relations were particularly tense following the

Amboyna Massacre in 1623. During the 18th century,

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

possessions were increasingly focused on the East Indies. After

the fourth war between the

United Provinces and England (1780–1784), the company suffered increasing financial difficulties. In 1799, the company was dissolved, commencing official colonisation of the

East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

. During the era of New Imperialism the territorial claims of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) expanded into a fully fledged colony named the

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

. Partly driven by re-newed colonial aspirations of fellow European nation states the Dutch strived to establish unchallenged control of the

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

now known as

Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian Ocean, Indian and Pacific Ocean, Pacific oceans. Comprising over List of islands of Indonesia, 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, ...

.

Six years into formal colonisation of the East Indies, in Europe the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

was occupied by the French forces of

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

. The Dutch government went into exile in England and formally ceded its colonial possessions to Great Britain. The pro-French Governor General of Java

Jan Willem Janssens, resisted

a British invasion force in 1811 until forced to surrender. British Governor

Raffles, who the later founded the city of

Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

, ruled the colony the following 10 years of the British

interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of revolutionary breach of legal continuity, discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one m ...

(1806–1816).

After the defeat of

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

and the

Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 colonial government of the East Indies was ceded back to the Dutch in 1817. The loss of South Africa and the continued scramble for Africa stimulated the Dutch to secure unchallenged dominion over its colony in the East Indies. The Dutch started to consolidate its power base through extensive military campaigns and elaborate diplomatic alliances with indigenous rulers ensuring the Dutch

tricolor was firmly planted in all corners of the

Archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

. These military campaigns included: the

Padri War (1821–1837), the

Java War

The Java War (; ; ), also known in Indonesia as the Diponegoro War (; ), was an armed conflict in central and eastern Java from 1825 to 1830, between native Javanese rebels headed by Prince Diponegoro and the Dutch East Indies supported by J ...

(1825–1830) and the

Aceh War

The Aceh War (), also known as the Dutch War or the Infidel War (1873–1904), was an armed military conflict between the Sultanate of Aceh and the Kingdom of the Netherlands which was triggered by discussions between representatives of Aceh ...

(1873–1904). This raised the need for a considerable military buildup of the colonial army (

KNIL

The Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (; KNIL, ; ) was the military force maintained by the Kingdom of the Netherlands in its Dutch colonial empire, colony of the Dutch East Indies, in areas that are now part of Indonesia. The KNIL's air arm ...

). From all over Europe soldiers were recruited to join the KNIL.

The Dutch concentrated their colonial enterprise in the

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

(Indonesia) throughout the 19th century. The Dutch lost control over the East Indies to the Japanese during much of World War II. Following the war, the Dutch fought Indonesian independence forces after Japan surrendered to the Allies in 1945. In 1949, most of what was known as the Dutch East Indies was ceded to the independent Republic of Indonesia. In 1962, also

Dutch New Guinea was annexed by Indonesia de facto ending Dutch imperialism in Asia.

British in India

Portuguese, French, and British competition in India (1600–1763)

The English sought to stake out claims in India at the expense of the Portuguese dating back to the

Elizabethan era

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The Roman symbol of Britannia (a female ...

. In 1600,

Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

incorporated the

English East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South Asia and Southeast A ...

(later the British East India Company), granting it a monopoly of trade from the Cape of Good Hope eastward to the Strait of Magellan. In 1639, it acquired

Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

on the east coast of India, where it quickly surpassed Portuguese Goa as the principal European trading Centre on the Indian Subcontinent.

Through bribes, diplomacy, and manipulation of weak native rulers, the company prospered in India, where it became the most powerful political force, and outrivaled its Portuguese and French competitors. For more than one hundred years, English and French trading companies had fought one another for supremacy, and, by the middle of the 18th century, competition between the British and the French had heated up. French defeat by the British under the command of

Robert Clive during the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

(1756–1763) marked the end of the French stake in India.

Collapse of Mughal India

The British East India Company, although still in direct competition with French and Dutch interests until 1763, following the subjugation of Bengal at the 1757

Battle of Plassey

The Battle of Plassey was a decisive victory of the British East India Company, under the leadership of Robert Clive, over the Nawab of Bengal and his French Indies Company, French allies on 23 June 1757. The victory was made possible by the de ...

. The British East India Company made great advances at the expense of the

Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an Early modern period, early modern empire in South Asia. At its peak, the empire stretched from the outer fringes of the Indus River Basin in the west, northern Afghanistan in the northwest, and Kashmir in the north, to ...

.

The reign of Aurangzeb had marked the height of Mughal power. By 1690 Mughal territorial expansion reached its greatest extent encompassing the entire Indian Subcontinent. But this period of power was followed by one of decline. Fifty years after the death of Aurangzeb, the great Mughal empire had crumbled. Meanwhile, marauding warlords, nobles, and others bent on gaining power left the

Subcontinent

A continent is any of several large geographical regions. Continents are generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria. A continent could be a single large landmass, a part of a very large landmass, as in the case of A ...

increasingly anarchic. Although the Mughals kept the imperial title until 1858, the central government had collapsed, creating a power vacuum.

From Company to Crown

Aside from defeating the French during the Seven Years' War,

Robert Clive, the leader of the East India Company in India, defeated

Siraj ud-Daulah

Mir Syed Jafar Ali Khan Mirza Muhammad Siraj-ud-Daulah (1733 – 2 July 1757), commonly known as Siraj-ud-Daulah or Siraj ud-Daula, was the last independent Nawab of the Bengal Subah. The end of his reign marked the start of the rule of th ...

, a key Indian ruler of Bengal, at the decisive

Battle of Plassey

The Battle of Plassey was a decisive victory of the British East India Company, under the leadership of Robert Clive, over the Nawab of Bengal and his French Indies Company, French allies on 23 June 1757. The victory was made possible by the de ...

(1757), a victory that ushered in the beginning of a new period in Indian history, that of informal British rule. While still nominally the sovereign. The transition to formal imperialism, characterized by

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

being crowned "Empress of India" in the 1870s, was a gradual process. The first step toward cementing formal British control extended back to the late 18th century. The British Parliament, disturbed by the idea that a great business concern, interested primarily in profit, was controlling the destinies of millions of people, passed acts in 1773 and 1784 that gave itself the power to control company policies.

The East India then fought a series of

Anglo-Mysore wars in

Southern India

South India, also known as Southern India or Peninsular India, is the southern part of the Deccan Peninsula in India encompassing the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana as well as the union territories of ...

with the

Sultanate of Mysore under

Hyder Ali and then

Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan (, , ''Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu''; 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799) commonly referred to as Sher-e-Mysore or "Tiger of Mysore", was a ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India. He was a pioneer of rocket artillery ...

. Defeats in the

First Anglo-Mysore war

The First Anglo-Mysore War (1767–1769) was a conflict in Mughal India, India between the Sultanate of Mysore and the East India Company. The war was instigated in part by the machinations of Nizam Ali Khan, Asaf Jah II, Asaf Jah II, the Niz ...

and stalemate in the

Second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

were followed by victories in the

Third and the

Fourth.

Following Tipu Sultan's death in the fourth war in the

Siege of Seringapatam (1799)

The siege of Seringapatam (5 April – 4 May 1799) was the final confrontation of the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War between the British East India Company and the Kingdom of Mysore. The British, with the allied Nizam Ali Khan, Asaf Jah II, Niz ...

, the kingdom would become a protectorate of the company.

The East India Company fought three Anglo-Maratha Wars with the

Maratha Confederacy

The Maratha Empire, also referred to as the Maratha Confederacy, was an early modern polity in the Indian subcontinent. It comprised the realms of the Peshwa and four major independent Maratha states under the nominal leadership of the former.

...

. The

First Anglo-Maratha War ended in 1782 with a restoration of the pre-war ''status quo''. The

Second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

and

Third Anglo-Maratha wars resulted in British victories. After the Surrender of Peshwa Bajirao II on 1818, the East India company acquired control of a large majority of the Indian Subcontinent.

Until 1858, however, much of India was still officially the dominion of the Mughal emperor. Anger among some social groups, however, was seething under the governor-generalship of

James Dalhousie (1847–1856), who annexed the

Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

(1849) after victory in the

Second Sikh War

The Second Anglo-Sikh War was a military conflict between the Sikh Empire and the East India Company which took place from 1848 to 1849. It resulted in the fall of the Sikh Empire, and the annexation of the Punjab region, Punjab and what sub ...

, annexed seven princely states using the

doctrine of lapse, annexed the key state of

Oudh on the basis of misgovernment, and upset cultural sensibilities by banning Hindu practices such as

sati

The 1857

Indian Rebellion, an uprising initiated by Indian troops, called sepoys, who formed the bulk of the company's armed forces, was the key turning point. Rumour had spread among them that their bullet cartridges were lubricated with pig and cow fat. The cartridges had to be bit open, so this upset the

Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

and

Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

soldiers. The

Hindu religion held cows sacred, and for Muslims pork was considered

haraam

''Haram'' (; ) is an Arabic term meaning 'taboo'. This may refer to either something sacred to which access is not allowed to the people who are not in a state of purity or who are not initiated into the sacred knowledge; or, in direct cont ...

. In one camp, 85 out of 90 sepoys would not accept the cartridges from their garrison officer. The British harshly punished those who would not by jailing them. The Indian people were outraged, and on May 10, 1857, sepoys marched to

Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, but spread chiefly to the west, or beyond its Bank (geography ...

, and, with the help of soldiers stationed there, captured it. Fortunately for the British, many areas remained loyal and quiescent, allowing the revolt to be crushed after fierce fighting. One important consequence of the revolt was the final collapse of the Mughal dynasty. The mutiny also ended the system of dual control under which the British government and the British East India Company shared authority. The government relieved the company of its political responsibilities, and in 1858, after 258 years of existence, the company relinquished its role. Trained civil servants were recruited from graduates of British universities, and these men set out to rule India. Lord Canning (created earl in 1859), appointed Governor-General of India in 1856, became known as "Clemency Canning" as a term of derision for his efforts to restrain revenge against the Indians during the Indian Mutiny. When the Government of India was transferred from the company to the Crown, Canning became the first

viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

of India.

The Company initiated the first of the

Anglo-Burmese Wars

The Anglo-Burmese people, also known as the Anglo-Burmans, are a community of Eurasians of Burmese and European descent; they emerged as a distinct community through mixed relationships (sometimes permanent, sometimes temporary) between the B ...

in 1824, which led to total annexation of Burma by the Crown in 1885. The

British ruled Burma as a

province of British India until 1937, then administered her separately under the

Burma Office except during the

Japanese occupation of Burma, 1942–1945, until granted independence on 4 January 1948. (Unlike India, Burma opted not to join the

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an International organization, international association of member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, 56 member states, the vast majo ...

.)

Rise of Indian nationalism

The denial of equal status to Indians was the immediate stimulus for the formation in 1885 of the

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

, initially loyal to the Empire but committed from 1905 to increased self-government and by 1930 to outright independence. The "Home charges", payments transferred from India for administrative costs, were a lasting source of nationalist grievance, though the flow declined in relative importance over the decades to independence in 1947.

Although majority

Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

and minority

Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

political leaders were able to collaborate closely in their criticism of British policy into the 1920s, British support for a distinct Muslim political organisation, the

Muslim League from 1906 and insistence from the 1920s on separate electorates for religious minorities, is seen by many in India as having contributed to Hindu-Muslim discord and the country's eventual

Partition.

France in Indochina

France, which had lost its empire to the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

by the end of the 18th century, had little geographical or commercial basis for expansion in Southeast Asia. After the 1850s, French imperialism was initially impelled by a

nationalistic need to rival the United Kingdom and was supported intellectually by the notion that French culture was superior to that of the people of

Annam (Vietnam), and its ''