Université de Paris on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The University of Paris (), known

The corporation was formally recognised as an "'' Universitas''" in an edict by King Philippe-Auguste in 1200: in it, among other accommodations granted to future students, he allowed the corporation to operate under ecclesiastic law which would be governed by the elders of the Notre-Dame Cathedral school, and assured all those completing courses there that they would be granted a diploma.

The university had four faculties:

The corporation was formally recognised as an "'' Universitas''" in an edict by King Philippe-Auguste in 1200: in it, among other accommodations granted to future students, he allowed the corporation to operate under ecclesiastic law which would be governed by the elders of the Notre-Dame Cathedral school, and assured all those completing courses there that they would be granted a diploma.

The university had four faculties:

The school of Saint-Victor, under the abbey, conferred the licence in its own right; the school of Notre-Dame depended on the diocese, that of Ste-Geneviève on the abbey or chapter. The diocese and the abbey or chapter, through their

The school of Saint-Victor, under the abbey, conferred the licence in its own right; the school of Notre-Dame depended on the diocese, that of Ste-Geneviève on the abbey or chapter. The diocese and the abbey or chapter, through their  To allow poor students to study the first college des dix-Huit was founded by a knight returning from Jerusalem called Josse of London for 18 scholars who received lodgings and 12 pence or denarii a month.

As the university developed, it became more institutionalized. First, the professors formed an association, for according to

To allow poor students to study the first college des dix-Huit was founded by a knight returning from Jerusalem called Josse of London for 18 scholars who received lodgings and 12 pence or denarii a month.

As the university developed, it became more institutionalized. First, the professors formed an association, for according to

In 1200, King Philip II issued a diploma "for the security of the scholars of Paris," which affirmed that students were subject only to ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The provost and other officers were forbidden to arrest a student for any offence, unless to transfer him to ecclesiastical authority. The king's officers could not intervene with any member unless having a mandate from an ecclesiastical authority. His action followed a violent incident between students and officers outside the city walls at a pub.

In 1215, the Apostolic legate, Robert de Courçon, issued new rules governing who could become a professor. To teach the arts, a candidate had to be at least twenty-one, to have studied these arts at least six years, and to take an engagement as professor for at least two years. For a chair in theology, the candidate had to be thirty years of age, with eight years of theological studies, of which the last three years were devoted to special courses of lectures in preparation for the mastership. These studies had to be made in the local schools under the direction of a master. In Paris, one was regarded as a scholar only by studies with particular masters. Lastly, purity of morals was as important as reading. The licence was granted, according to custom, gratuitously, without oath or condition. Masters and students were permitted to unite, even by oath, in defence of their rights, when they could not otherwise obtain justice in serious matters. No mention is made either of law or of medicine, probably because these sciences were less prominent.

In 1229, a denial of justice by the queen led to suspension of the courses. The pope intervened with a

In 1200, King Philip II issued a diploma "for the security of the scholars of Paris," which affirmed that students were subject only to ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The provost and other officers were forbidden to arrest a student for any offence, unless to transfer him to ecclesiastical authority. The king's officers could not intervene with any member unless having a mandate from an ecclesiastical authority. His action followed a violent incident between students and officers outside the city walls at a pub.

In 1215, the Apostolic legate, Robert de Courçon, issued new rules governing who could become a professor. To teach the arts, a candidate had to be at least twenty-one, to have studied these arts at least six years, and to take an engagement as professor for at least two years. For a chair in theology, the candidate had to be thirty years of age, with eight years of theological studies, of which the last three years were devoted to special courses of lectures in preparation for the mastership. These studies had to be made in the local schools under the direction of a master. In Paris, one was regarded as a scholar only by studies with particular masters. Lastly, purity of morals was as important as reading. The licence was granted, according to custom, gratuitously, without oath or condition. Masters and students were permitted to unite, even by oath, in defence of their rights, when they could not otherwise obtain justice in serious matters. No mention is made either of law or of medicine, probably because these sciences were less prominent.

In 1229, a denial of justice by the queen led to suspension of the courses. The pope intervened with a

The "nations" appeared in the second half of the twelfth century. They were mentioned in the Bull of

The "nations" appeared in the second half of the twelfth century. They were mentioned in the Bull of

The scattered condition of the scholars in Paris often made lodging difficult. Some students rented rooms from townspeople, who often exacted high rates while the students demanded lower. This tension between scholars and citizens would have developed into a sort of civil war if Robert de Courçon had not found the remedy of taxation. It was upheld in the Bull of Gregory IX of 1231, but with an important modification: its exercise was to be shared with the citizens. The aim was to offer the students a shelter where they would fear neither annoyance from the owners nor the dangers of the world. Thus were founded the colleges (colligere, to assemble); meaning not centers of instruction, but simple student boarding-houses. Each had a special goal, being established for students of the same nationality or the same science. Often, masters lived in each college and oversaw its activities.

Four colleges appeared in the 12th century; they became more numerous in the 13th, including

The scattered condition of the scholars in Paris often made lodging difficult. Some students rented rooms from townspeople, who often exacted high rates while the students demanded lower. This tension between scholars and citizens would have developed into a sort of civil war if Robert de Courçon had not found the remedy of taxation. It was upheld in the Bull of Gregory IX of 1231, but with an important modification: its exercise was to be shared with the citizens. The aim was to offer the students a shelter where they would fear neither annoyance from the owners nor the dangers of the world. Thus were founded the colleges (colligere, to assemble); meaning not centers of instruction, but simple student boarding-houses. Each had a special goal, being established for students of the same nationality or the same science. Often, masters lived in each college and oversaw its activities.

Four colleges appeared in the 12th century; they became more numerous in the 13th, including

In the fifteenth century,

In the fifteenth century,

The ancient university disappeared with the

The ancient university disappeared with the

File:Francisco_de_Zurbar%C3%A1n_-_The_Prayer_of_St._Bonaventura_about_the_Selection_of_the_New_Pope_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg,

File:John Calvin - Young.jpg,

* Rodolfo Robles, physician

* Albert Simard, physician, activist during and post WWII.

* Carlos Alvarado-Larroucau, writer

*

Paul Nadar - Henri Becquerel.jpg, Antoine-Henri Becquerel

Marie_Curie_c1920.jpg, Marie Skłodowska Curie

Ren%C3%A9_Cassin_nobel.jpg, René Cassin

Henri_Bergson_02.jpg,

Gabriel Lippmann2.jpg,

''La Sorbonne: ses origines, sa bibliothèque, les débuts de l'imprimerie à Paris et la succession de Richelieu d'après des documents inédits, 2. édition''

Paris: L. Willem, 1875 * Leutrat, Jean-Louis: ''De l'Université aux Universités'' (From the University to the Universities), Paris: Association des Universités de Paris, 1997 * Post, Gaines: ''The Papacy and the Rise of Universities'' Ed. with a Preface by William J. Courtenay. Education and Society in the Middle Ages and Renaissance 54 Leiden: Brill, 2017. *Rivé, Phillipe: ''La Sorbonne et sa reconstruction'' (The Sorbonne and its Reconstruction), Lyon: La Manufacture, 1987 * Tuilier, André: ''Histoire de l'Université de Paris et de la Sorbonne'' (History of the University of Paris and of the Sorbonne), in 2 volumes (From the Origins to Richelieu, From LouisXIV to the Crisis of 1968), Paris: Nouvelle Librairie de France, 1997 * Verger, Jacques: ''Histoire des Universités en France'' (History of French Universities), Toulouse: Editions Privat, 1986 * Traver, Andrew G. 'Rewriting History?: The Parisian Secular Masters' ''Apologia'' of 1254,' ''History of Universities'' 15 (1997–9): 9–45.

Chancellerie des Universités de Paris

(official homepage)

Projet Studium Parisiense

: database of members of the University of Paris from the 11th to 16th centuries

Liste des Universités de Paris et d'Ile-de-France : nom, adresse, cours, diplômes...

{{DEFAULTSORT:University Of Paris 1150 establishments in Europe 1150s establishments in France 12th-century establishments in France 1970 disestablishments in France Paris, University of Defunct educational institutions Medieval European universities Philip II of France

metonymically

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something associated with that thing or concept. For example, the word "suit" may refer to a person from groups commonly wearing business attire, such as salespe ...

as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation

A corporation or body corporate is an individual or a group of people, such as an association or company, that has been authorized by the State (polity), state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law as ...

associated with the cathedral school

Cathedral schools began in the Early Middle Ages as centers of advanced education, some of them ultimately evolving into medieval universities. Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, they were complemented by the monastic schools. Some of these ...

of Paris, it was considered the second-oldest university in Europe. Charles Homer Haskins: ''The Rise of Universities'', Henry Holt and Company, 1923, p. 292. Officially charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the ...

ed in 1200 by King Philip II and recognised in 1215 by Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

, it was nicknamed after its theological College of Sorbonne

The College of Sorbonne () was a theological college of the University of Paris, founded in 1253 (confirmed in 1257) by Robert de Sorbon (1201–1274), after whom it was named.

The Sorbonne was disestablished by decree of 5 April 1792, after th ...

, founded by Robert de Sorbon

Robert de Sorbon (; 9 October 1201 – 15 August 1274) was a French theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typic ...

and chartered by King Louis IX around 1257.

Highly reputed internationally for its academic performance in the humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture, including Philosophy, certain fundamental questions asked by humans. During the Renaissance, the term "humanities" referred to the study of classical literature a ...

ever since the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

– particularly in theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

and philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

– it introduced academic standards and traditions that have endured and spread, such as doctoral degree

A doctorate (from Latin ''doctor'', meaning "teacher") or doctoral degree is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism '' licentia docendi'' ("licence to teach ...

s and student nation

Student nations or simply nations ( meaning "being born") are regional corporations of students at a university. Once widespread across Europe in medieval times, they are now largely restricted to the oldest universities of Sweden and Finland, in p ...

s. Notable popes

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the pope was the sovereign or head of sta ...

, royalty

Royalty may refer to:

* the mystique/prestige bestowed upon monarchs

** one or more monarchs, such as kings, queens, emperors, empresses, princes, princesses, etc.

*** royal family, the immediate family of a king or queen-regnant, and sometimes h ...

, scientists, and intellectuals were educated at the University of Paris. A few of the colleges of the time are still visible close to the Panthéon

The Panthéon (, ), is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, Paris, Latin Quarter (Quartier latin), atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was built between 1758 ...

and Jardin du Luxembourg

The Jardin du Luxembourg (), known in English as the Luxembourg Garden, colloquially referred to as the Jardin du Sénat (Senate Garden), is located in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, France. The creation of the garden began in 1612 when Mar ...

: Collège des Bernardins

The Collège of Bernardins, or Collège Saint-Bernard, located no 20, rue de Poissy in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, is a former Cistercian college of the University of Paris. Founded by Stephen of Lexington, abbot of Clairvaux, and built from 1 ...

(18 rue de Poissy, 5th arr.), Hôtel de Cluny (6 Place Paul Painlevé, 5th arr.), Collège Sainte-Barbe (4 rue Valette, 5th arr.), Collège d'Harcourt (44 Boulevard Saint-Michel, 6th arr.), and Cordeliers (21 rue École de Médecine, 6th arr.).

In 1793, during the French Revolution, the university was closed and, by Item 27 of the Revolutionary Convention, the college endowments and buildings were sold. A new University of France

The University of France (; originally the ''Imperial University of France'') was a highly centralized educational state organization founded by Napoleon I in 1806 and given authority not only over the individual (previously independent) universiti ...

replaced it in 1806 with four independent faculties: the Faculty of Humanities (), the Faculty of Law

A faculty is a division within a university or college comprising one subject area or a group of related subject areas, possibly also delimited by level (e.g. undergraduate). In North America, academic divisions are sometimes titled colleges, sc ...

(later including Economics), the Faculty of Science, the Faculty of Medicine

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, professional school, or forms a part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, ...

and the Faculty of Theology (closed in 1885).

In 1896, a new University of Paris was re-founded as a grouping of the Paris faculties of science, literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

, law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

, medicine, Protestant theology and the École supérieure de pharmacie de Paris. It was inaugurated on November 19, 1896, by French President Félix Faure. In 1970, after the civil unrest of May 1968, the university was divided into 13 autonomous universities, which today are the Sorbonne University

Sorbonne University () is a public research university located in Paris, France. The institution's legacy reaches back to the Middle Ages in 1257 when Sorbonne College was established by Robert de Sorbon as a constituent college of the Unive ...

, Panthéon-Sorbonne University, the Assas University, the Sorbonne Nouvelle University, the Paris Cité University, the PSL University, the Saclay University, the Nanterre University, the Sorbonne Paris North University

Sorbonne Paris North University () is a public university based in Paris, France. It is one of the thirteen universities that succeeded the University of Paris in 1968. It is a multidisciplinary university located in north of Paris, in the munici ...

, the Paris-East Créteil University and the Paris 8 University. The Chancellerie des Universités de Paris inherited the heritage assets of the University of Paris, including the Sorbonne building, the "''La Sorbonne''" brand, control of the inter-university libraries, and management of the staff of the Paris universities (until 2007).

History

Origins

In 1150, the future University of Paris was a student–teacher corporation operating as an annex of thecathedral school

Cathedral schools began in the Early Middle Ages as centers of advanced education, some of them ultimately evolving into medieval universities. Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, they were complemented by the monastic schools. Some of these ...

. The earliest historical reference to it is found in Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris (; 1200 – 1259), was an English people, English Benedictine monk, English historians in the Middle Ages, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts, and cartographer who was based at St A ...

's reference to the studies of his own teacher (an abbot of St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major ...

) and his acceptance into "the fellowship of the elect Masters" there in about 1170, and it is known that Lotario dei Conti di Segni, the future Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

, completed his studies there in 1182 at the age of 21. Its first college was the Collège des Dix-Huit, established in 1180 by an Englishman named Josse and endowed for 18 poor scholars.  The corporation was formally recognised as an "'' Universitas''" in an edict by King Philippe-Auguste in 1200: in it, among other accommodations granted to future students, he allowed the corporation to operate under ecclesiastic law which would be governed by the elders of the Notre-Dame Cathedral school, and assured all those completing courses there that they would be granted a diploma.

The university had four faculties:

The corporation was formally recognised as an "'' Universitas''" in an edict by King Philippe-Auguste in 1200: in it, among other accommodations granted to future students, he allowed the corporation to operate under ecclesiastic law which would be governed by the elders of the Notre-Dame Cathedral school, and assured all those completing courses there that they would be granted a diploma.

The university had four faculties: Arts

The arts or creative arts are a vast range of human practices involving creativity, creative expression, storytelling, and cultural participation. The arts encompass diverse and plural modes of thought, deeds, and existence in an extensive ...

, Medicine, Law, and Theology. The Faculty of Arts was the lowest in rank, but also the largest, as students had to graduate there in order to be admitted to one of the higher faculties. The students were divided into four '' nationes'' according to language or regional origin: France, Normandy, Picardy, and England. The last came to be known as the ''Alemannian'' (German) nation. Recruitment to each nation was wider than the names might imply: the English–German nation included students from Scandinavia and Eastern Europe.

The faculty and nation system of the University of Paris (along with that of the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna (, abbreviated Unibo) is a Public university, public research university in Bologna, Italy. Teaching began around 1088, with the university becoming organised as guilds of students () by the late 12th century. It is the ...

) became the model for all later medieval universities. Under the governance of the Church, students wore robes and shaved the tops of their heads in tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

, to signify they were under the protection of the church. Students followed the rules and laws of the Church and were not subject to the king's laws or courts. This presented problems for the city of Paris, as students ran wild, and its official had to appeal to Church courts for justice. Students were often very young, entering the school at 13 or 14 years of age and staying for six to 12 years.

12th century: Organisation

Three schools were especially famous in Paris: the ''palatine or palace school'', the ''school of Notre-Dame'', and that of Sainte-Geneviève Abbey. The latter two, although ancient, were initially eclipsed by the palatine school, until the decline of royalty brought about its decline. The first renowned professor at the school of Ste-Geneviève was Hubold, who lived in the tenth century. Not content with the courses atLiège

Liège ( ; ; ; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia, and the capital of the Liège Province, province of Liège, Belgium. The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east o ...

, he continued his studies at Paris, entered or allied himself with the chapter of Ste-Geneviève, and attracted many pupils via his teaching. Distinguished professors from the school of Notre-Dame in the eleventh century include Lambert, disciple of Fulbert of Chartres; Drogo of Paris; Manegold of Germany; and Anselm of Laon

Anselm of Laon (; 1117), properly Ansel ('), was a French theology, theologian and founder of a school of scholars who helped to pioneer biblical hermeneutics.

Biography

Born of very humble parents at Laon before the middle of the 11th centur ...

. These two schools attracted scholars from every country and produced many illustrious men, among whom were: St. Stanislaus of Szczepanów, Bishop of Kraków; Gebbard, Archbishop of Salzburg; St. Stephen, third Abbot of Cîteaux; Robert d'Arbrissel, founder of the Abbey of Fontevrault etc. Three other men who added prestige to the schools of Notre-Dame and Ste-Geneviève were William of Champeaux, Abélard, and Peter Lombard

Peter Lombard (also Peter the Lombard, Pierre Lombard or Petrus Lombardus; 1096 – 21/22 August 1160) was an Italian scholasticism, scholastic theologian, Bishop of Paris, and author of ''Sentences, Four Books of Sentences'' which became the s ...

.

Humanistic instruction comprised grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of rules for how a natural language is structured, as demonstrated by its speakers or writers. Grammar rules may concern the use of clauses, phrases, and words. The term may also refer to the study of such rul ...

, rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

, dialectics

Dialectic (; ), also known as the dialectical method, refers originally to dialogue between people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to arrive at the truth through reasoned argument. Dialectic resembles debate, but the ...

, arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

, geometry

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

, music, and astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

(trivium

The trivium is the lower division of the seven liberal arts and comprises grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

The trivium is implicit in ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury") by Martianus Capella, but the term was not used until the Carolin ...

and quadrivium

From the time of Plato through the Middle Ages, the ''quadrivium'' (plural: quadrivia) was a grouping of four subjects or arts—arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy—that formed a second curricular stage following preparatory work in th ...

). To the higher instruction belonged dogmatic

Dogma, in its broadest sense, is any belief held definitively and without the possibility of reform. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Judaism, Catholic Church, Roman Catholicism, Protes ...

and moral theology

Ethics involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior.''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy''"Ethics" A central aspect of ethics is "the good life", the life worth living or life that is simply satisfyin ...

, whose source was the Scriptures and the Patristic Fathers. It was completed by the study of Canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

. The School of Saint-Victor arose to rival those of Notre-Dame and Ste-Geneviève. It was founded by William of Champeaux when he withdrew to the Abbey of Saint-Victor. Its most famous professors are Hugh of St. Victor and Richard of St. Victor.

The plan of studies expanded in the schools of Paris, as it did elsewhere. A Bolognese compendium of canon law called the brought about a division of the theology department. Hitherto the discipline of the Church had not been separate from so-called theology; they were studied together under the same professor. But this vast collection necessitated a special course, which was undertaken first at Bologna, where Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (), to the (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I.

Roman law also den ...

was taught. In France, first Orléans

Orléans (,"Orleans"

(US) and Decretal Decretals () are letters of a pope that formulate decisions in canon law (Catholic Church), ecclesiastical law of the Catholic Church.McGurk. ''Dictionary of Medieval Terms''. p. 10 They are generally given in answer to consultations but are some ...

s of Gerard La Pucelle, Mathieu d'Angers, and Anselm (or Anselle) of Paris, were added to the Decretum Gratiani. However, civil law was not included at Paris. In the twelfth century, medicine began to be publicly taught at Paris: the first professor of medicine in Paris records is Hugo, ''physicus excellens qui quadrivium docuit''.

Professors were required to have measurable knowledge and be appointed by the university. Applicants had to be assessed by examination; if successful, the examiner, who was the head of the school, and known as ''scholasticus'', ''capiscol'', and ''chancellor,'' appointed an individual to teach. This was called the (US) and Decretal Decretals () are letters of a pope that formulate decisions in canon law (Catholic Church), ecclesiastical law of the Catholic Church.McGurk. ''Dictionary of Medieval Terms''. p. 10 They are generally given in answer to consultations but are some ...

licence

A license (American English) or licence (Commonwealth English) is an official permission or permit to do, use, or own something (as well as the document of that permission or permit).

A license is granted by a party (licensor) to another part ...

or faculty to teach. The licence had to be granted freely. No one could teach without it; on the other hand, the examiner could not refuse to award it when the applicant deserved it.

The school of Saint-Victor, under the abbey, conferred the licence in its own right; the school of Notre-Dame depended on the diocese, that of Ste-Geneviève on the abbey or chapter. The diocese and the abbey or chapter, through their

The school of Saint-Victor, under the abbey, conferred the licence in its own right; the school of Notre-Dame depended on the diocese, that of Ste-Geneviève on the abbey or chapter. The diocese and the abbey or chapter, through their chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

, gave professorial investiture in their respective territories where they had jurisdiction. Besides Notre-Dame, Ste-Geneviève, and Saint-Victor, there were several schools on the "Island" and on the "Mount". "Whoever", says Crevier "had the right to teach might open a school where he pleased, provided it was not in the vicinity of a principal school." Thus a certain Adam, who was of English origin, kept his "near the Petit Pont"; another Adam, Parisian by birth, "taught at the Grand Pont which is called the Pont-au-Change" (''Hist. de l'Univers. de Paris,'' I, 272).

The number of students in the school of the capital grew constantly, so that lodgings were insufficient. French students included princes of the blood, sons of the nobility, and ranking gentry. The courses at Paris were considered so necessary as a completion of studies that many foreigners flocked to them. Popes Celestine II, Adrian IV and Innocent III

Pope Innocent III (; born Lotario dei Conti di Segni; 22 February 1161 – 16 July 1216) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 until his death on 16 July 1216.

Pope Innocent was one of the most power ...

studied at Paris, and Alexander III sent his nephews there. Noted German and English students included Otto of Freising

Otto of Freising (; – 22 September 1158) was a German churchman of the Cistercian order and chronicled at least two texts which carry valuable information on the political history of his own time. He was the bishop of Freising from 1138. Ot ...

en, Cardinal Conrad, Archbishop of Mainz, St. Thomas of Canterbury, and John of Salisbury

John of Salisbury (late 1110s – 25 October 1180), who described himself as Johannes Parvus ("John the Little"), was an English author, philosopher, educationalist, diplomat and bishop of Chartres. The historian Hans Liebeschuetz described him ...

; while Ste-Geneviève became practically the seminary for Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

. The chroniclers of the time called Paris the city of letters par excellence, placing it above Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Rome, and other cities: "At that time, there flourished at Paris philosophy and all branches of learning, and there the seven arts were studied and held in such esteem as they never were at Athens, Egypt, Rome, or elsewhere in the world." ("Les gestes de Philippe-Auguste"). Poets extolled the university in their verses, comparing it to all that was greatest, noblest, and most valuable in the world.

To allow poor students to study the first college des dix-Huit was founded by a knight returning from Jerusalem called Josse of London for 18 scholars who received lodgings and 12 pence or denarii a month.

As the university developed, it became more institutionalized. First, the professors formed an association, for according to

To allow poor students to study the first college des dix-Huit was founded by a knight returning from Jerusalem called Josse of London for 18 scholars who received lodgings and 12 pence or denarii a month.

As the university developed, it became more institutionalized. First, the professors formed an association, for according to Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris (; 1200 – 1259), was an English people, English Benedictine monk, English historians in the Middle Ages, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts, and cartographer who was based at St A ...

, John of Celles, twenty-first Abbot of St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major ...

, England, was admitted as a member of the teaching corps of Paris after he had followed the courses (''Vita Joannis I, XXI, abbat. S. Alban''). The masters, as well as the students, were divided according to national origin,. Alban wrote that Henry II, King of England

Henry may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Henry (given name), including lists of people and fictional characters

* Henry (surname)

* Henry, a stage name of François-Louis Henry (1786–1855), French baritone

Arts and entertainme ...

, in his difficulties with St. Thomas of Canterbury, wanted to submit his cause to a tribunal composed of professors of Paris, chosen from various provinces (Hist. major, Henry II, to end of 1169). This was likely the start of the division according to "nations," which was later to play an important part in the university. Celestine III ruled that both professors and students had the privilege of being subject only to the ecclesiastical courts, not to civil courts.

The three schools: Notre-Dame, Sainte-Geneviève, and Saint-Victor, may be regarded as the triple cradle of the ''Universitas scholarium'', which included masters and students; hence the name ''University''. Henry Denifle and some others hold that this honour is exclusive to the school of Notre-Dame (Chartularium Universitatis Parisiensis), but the reasons do not seem convincing. He excludes Saint-Victor because, at the request of the abbot and the religious of Saint-Victor, Gregory IX in 1237 authorized them to resume the interrupted teaching of theology. But the university was largely founded about 1208, as is shown by a Bull of Innocent III. Consequently, the schools of Saint-Victor might well have contributed to its formation. Secondly, Denifle excludes the schools of Ste-Geneviève because there had been no interruption in the teaching of the liberal arts. This is debatable and through the period, theology was taught. The chancellor of Ste-Geneviève continued to give degrees in arts, something he would have ceased if his abbey had no part in the university organization.

13th–14th century: Expansion

In 1200, King Philip II issued a diploma "for the security of the scholars of Paris," which affirmed that students were subject only to ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The provost and other officers were forbidden to arrest a student for any offence, unless to transfer him to ecclesiastical authority. The king's officers could not intervene with any member unless having a mandate from an ecclesiastical authority. His action followed a violent incident between students and officers outside the city walls at a pub.

In 1215, the Apostolic legate, Robert de Courçon, issued new rules governing who could become a professor. To teach the arts, a candidate had to be at least twenty-one, to have studied these arts at least six years, and to take an engagement as professor for at least two years. For a chair in theology, the candidate had to be thirty years of age, with eight years of theological studies, of which the last three years were devoted to special courses of lectures in preparation for the mastership. These studies had to be made in the local schools under the direction of a master. In Paris, one was regarded as a scholar only by studies with particular masters. Lastly, purity of morals was as important as reading. The licence was granted, according to custom, gratuitously, without oath or condition. Masters and students were permitted to unite, even by oath, in defence of their rights, when they could not otherwise obtain justice in serious matters. No mention is made either of law or of medicine, probably because these sciences were less prominent.

In 1229, a denial of justice by the queen led to suspension of the courses. The pope intervened with a

In 1200, King Philip II issued a diploma "for the security of the scholars of Paris," which affirmed that students were subject only to ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The provost and other officers were forbidden to arrest a student for any offence, unless to transfer him to ecclesiastical authority. The king's officers could not intervene with any member unless having a mandate from an ecclesiastical authority. His action followed a violent incident between students and officers outside the city walls at a pub.

In 1215, the Apostolic legate, Robert de Courçon, issued new rules governing who could become a professor. To teach the arts, a candidate had to be at least twenty-one, to have studied these arts at least six years, and to take an engagement as professor for at least two years. For a chair in theology, the candidate had to be thirty years of age, with eight years of theological studies, of which the last three years were devoted to special courses of lectures in preparation for the mastership. These studies had to be made in the local schools under the direction of a master. In Paris, one was regarded as a scholar only by studies with particular masters. Lastly, purity of morals was as important as reading. The licence was granted, according to custom, gratuitously, without oath or condition. Masters and students were permitted to unite, even by oath, in defence of their rights, when they could not otherwise obtain justice in serious matters. No mention is made either of law or of medicine, probably because these sciences were less prominent.

In 1229, a denial of justice by the queen led to suspension of the courses. The pope intervened with a bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not Castration, castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e. cows proper), bulls have long been an important symbol cattle in r ...

that began with lavish praise of the university: "Paris", said Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX (; born Ugolino di Conti; 1145 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and the ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decretales'' and instituting the P ...

, "mother of the sciences, is another Cariath-Sepher, city of letters". He commissioned the Bishops of Le Mans and Senlis and the Archdeacon of Châlons to negotiate with the French Court for the restoration of the university, but by the end of 1230 they had accomplished nothing. Gregory IX then addressed a Bull of 1231 to the masters and scholars of Paris. Not only did he settle the dispute, he empowered the university to frame statutes concerning the discipline of the schools, the method of instruction, the defence of theses, the costume of the professors, and the obsequies of masters and students (expanding upon Robert de Courçon's statutes). Most importantly, the pope granted the university the right to suspend its courses, if justice were denied it, until it should receive full satisfaction.

The pope authorized Pierre Le Mangeur to collect a moderate fee for the conferring of the license of professorship. Also, for the first time, the scholars had to pay tuition fees

Tuition payments, usually known as tuition in American English and as tuition fees in English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English, are fees charged by education institutions for instruction or other services. Besides public spen ...

for their education: two sous weekly, to be deposited in the common fund.

Rector

The university was organized as follows: at the head of the teaching body was a rector. The office was elective and of short duration; at first it was limited to four or six weeks. Simon de Brion, legate of theHoly See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

in France, realizing that such frequent changes caused serious inconvenience, decided that the rectorate should last three months, and this rule was observed for three years. Then the term was lengthened to one, two, and sometimes three years. The right of election belonged to the procurators of the four nations

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, territory, or societ ...

. Henry of Unna was proctor

Proctor (a variant of ''wikt:procurator, procurator'') is a person who takes charge of, or acts for, another.

The title is used in England and some other English-speaking countries in three principal contexts:

# In law, a proctor is a historica ...

of the University of Paris in the 14th century, beginning his term on January 13, 1340.

Four "nations"

The "nations" appeared in the second half of the twelfth century. They were mentioned in the Bull of

The "nations" appeared in the second half of the twelfth century. They were mentioned in the Bull of Honorius III

Pope Honorius III (c. 1150 – 18 March 1227), born Cencio Savelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 July 1216 to his death. A canon at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, he came to hold a number of importa ...

in 1222. Later, they formed a distinct body. By 1249, the four nations existed with their procurators, their rights (more or less well-defined), and their keen rivalries: the nations were the French, English, Normans, and Picards. After the Hundred Years' War, the English nation was replaced by the Germanic. The four nations constituted the faculty of arts or letters.

The territories covered by the four nations were:

* French nation: all the Romance-speaking

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic branch of the Indo-European language family.

The fi ...

parts of Europe except those included within the Norman and Picard nations

* English nation (renamed 'German nation' after the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

): the British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

, the Germanic-speaking parts of continental Europe (except those included within the Picard nation), and the Slavic-speaking parts of Europe. The majority of students within that nation came from Germany and Scotland, and when it was renamed 'German nation' it was also sometimes called ''natio Germanorum et Scotorum'' ("nation of the Germans and Scots").

* Norman nation: the ecclesiastical province of Rouen, which corresponded approximately to the Duchy of Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between Charles the Simple, King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a r ...

. This was a Romance-speaking territory, but it was not included within the French nation.

* Picard nation: the Romance-speaking bishoprics

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associated ...

of Beauvais

Beauvais ( , ; ) is a town and Communes of France, commune in northern France, and prefecture of the Oise Departments of France, département, in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, north of Paris.

The Communes of France, commune o ...

, Noyon

Noyon (; ; , Noviomagus of the Viromandui, Veromandui, then ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Oise Departments of France, department, Northern France.

Geography

Noyon lies on the river Oise (river), Oise, about northeast of Paris. The ...

, Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; , or ) is a city and Communes of France, commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme (department), Somme Departments of France, department in the region ...

, Laon

Laon () is a city in the Aisne Departments of France, department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

History

Early history

The Ancient Diocese of Laon, which rises a hundred metres above the otherwise flat Picardy plain, has always held s ...

, and Arras

Arras ( , ; ; historical ) is the prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department, which forms part of the region of Hauts-de-France; before the reorganization of 2014 it was in Nord-Pas-de-Calais. The historic centre of the Artois region, with a ...

; the bilingual (Romance and Germanic-speaking) bishoprics of Thérouanne

Thérouanne (; ; Dutch ''Terwaan'') is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in the Hauts-de-France region of France west of Aire-sur-la-Lys and south of Saint-Omer, on the river Lys.

Population

History

At the time of the Gauls, ''T ...

, Cambrai

Cambrai (, ; ; ), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord department and in the Hauts-de-France region of France on the Scheldt river, which is known locally as the Escaut river.

A sub-pref ...

, and Tournai

Tournai ( , ; ; ; , sometimes Anglicisation (linguistics), anglicised in older sources as "Tournay") is a city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia located in the Hainaut Province, Province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies by ...

; a large part of the bilingual bishopric of Liège

Liège ( ; ; ; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia, and the capital of the Liège Province, province of Liège, Belgium. The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east o ...

; and the southernmost part of the Germanic-speaking bishopric of Utrecht

Utrecht ( ; ; ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city of the Netherlands, as well as the capital and the most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of Utrecht (province), Utrecht. The ...

(the part of that bishopric located south of the river Meuse

The Meuse or Maas is a major European river, rising in France and flowing through Belgium and the Netherlands before draining into the North Sea from the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. It has a total length of .

History

From 1301, the upper ...

; the rest of the bishopric north of the Meuse belonged to the English nation). It was estimated that about half of the students in the Picard nation were Romance-speakers (Picard

Picard may refer to:

Places

* Picard, Quebec, Canada

* Picard, California, United States

* Picard (crater), a lunar impact crater in Mare Crisium

People and fictional characters

* Picard (name), a list of people and fictional characters with th ...

and Walloon), and the other half were Germanic-speakers (West Flemish

West Flemish (''West-Vlams'' or ''West-Vloams'' or ''Vlaemsch'' (in French Flanders), , ) is a collection of Low Franconian varieties spoken in western Belgium and the neighbouring areas of France and the Netherlands.

West Flemish is spoken by ...

, East Flemish, Brabantian and Limburgish

Limburgish ( or ; ; also Limburgian, Limburgic or Limburgan) refers to a group of South Low Franconian Variety (linguistics), varieties spoken in Belgium and the Netherlands, characterized by their distance to, and limited participation ...

dialects).

Faculties

To classify professors' knowledge, the schools of Paris gradually divided into faculties. Professors of the same science were brought into closer contact until the community of rights and interests cemented the union and made them distinct groups. The faculty of medicine seems to have been the last to form. But the four faculties were already formally established by 1254, when the university described in a letter "theology, jurisprudence, medicine, and rational, natural, and moral philosophy". The masters of theology often set the example for the other faculties—e.g., they were the first to adopt an official seal. The faculties of theology, canon law, and medicine, were called "superior faculties". The title of " Dean" as designating the head of a faculty, came into use by 1268 in the faculties of law and medicine, and by 1296 in the faculty of theology. It seems that at first the deans were the oldest masters. The faculty of arts continued to have four procurators of its four nations and its head was the rector. As the faculties became more fully organized, the division into four nations partially disappeared for theology, law and medicine, though it continued in arts. Eventually the superior faculties included only doctors, leaving the bachelors to the faculty of arts. At this period, therefore, the university had two principal degrees, the baccalaureate and the doctorate. It was not until much later that the licentiate and the DEA became intermediate degrees.Colleges

The scattered condition of the scholars in Paris often made lodging difficult. Some students rented rooms from townspeople, who often exacted high rates while the students demanded lower. This tension between scholars and citizens would have developed into a sort of civil war if Robert de Courçon had not found the remedy of taxation. It was upheld in the Bull of Gregory IX of 1231, but with an important modification: its exercise was to be shared with the citizens. The aim was to offer the students a shelter where they would fear neither annoyance from the owners nor the dangers of the world. Thus were founded the colleges (colligere, to assemble); meaning not centers of instruction, but simple student boarding-houses. Each had a special goal, being established for students of the same nationality or the same science. Often, masters lived in each college and oversaw its activities.

Four colleges appeared in the 12th century; they became more numerous in the 13th, including

The scattered condition of the scholars in Paris often made lodging difficult. Some students rented rooms from townspeople, who often exacted high rates while the students demanded lower. This tension between scholars and citizens would have developed into a sort of civil war if Robert de Courçon had not found the remedy of taxation. It was upheld in the Bull of Gregory IX of 1231, but with an important modification: its exercise was to be shared with the citizens. The aim was to offer the students a shelter where they would fear neither annoyance from the owners nor the dangers of the world. Thus were founded the colleges (colligere, to assemble); meaning not centers of instruction, but simple student boarding-houses. Each had a special goal, being established for students of the same nationality or the same science. Often, masters lived in each college and oversaw its activities.

Four colleges appeared in the 12th century; they became more numerous in the 13th, including Collège d'Harcourt

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 14.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for students between ...

(1280) and the Collège de Sorbonne

The College of Sorbonne () was a theological college of the University of Paris, founded in 1253 (confirmed in 1257) by Robert de Sorbon (1201–1274), after whom it was named.

The Sorbonne was disestablished by decree of 5 April 1792, after th ...

(1257). Thus the University of Paris assumed its basic form. It was composed of seven groups, the four nations of the faculty of arts, and the three superior faculties of theology, law, and medicine. Men who had studied at Paris became an increasing presence in the high ranks of the Church hierarchy; eventually, students at the University of Paris saw it as a right that they would be eligible to benefices. Church officials such as St. Louis and Clement IV lavishly praised the university.

Besides the famous Collège de Sorbonne, other ''collegia'' provided housing and meals to students, sometimes for those of the same geographical origin in a more restricted sense than that represented by the nations. There were 8 or 9 ''collegia'' for foreign students: the oldest one was the Danish college, the ''Collegium danicum'' or ''dacicum'', founded in 1257. Swedish students could, during the 13th and 14th centuries, live in one of three Swedish colleges, the ''Collegium Upsaliense'', the ''Collegium Scarense'' or the ''Collegium Lincopense'', named after the Swedish dioceses of Uppsala

Uppsala ( ; ; archaically spelled ''Upsala'') is the capital of Uppsala County and the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, fourth-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö. It had 177,074 inhabitants in 2019.

Loc ...

, Skara and Linköping

Linköping ( , ) is a city in southern Sweden, with around 167,000 inhabitants as of 2024. It is the seat of Linköping Municipality and the capital of Östergötland County. Linköping is also the episcopal see of the Diocese of Linköping (Chu ...

.

The'' Collège de Navarre

The College of Navarre (, ) was one of the colleges of the historic University of Paris. It rivaled the University of Paris, Sorbonne and was renowned for its library.

History

The college was founded by Queen Joan I of Navarre in 1305, who provi ...

'' was founded in 1305, originally aimed at students from Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

, but due to its size, wealth, and the links between the crowns of France and Navarre, it quickly accepted students from other nations. The establishment of the College of Navarre was a turning point in the university's history: Navarra was the first college to offer teaching to its students, which at the time set it apart from all previous colleges, founded as charitable institutions that provided lodging, but no tuition. Navarre's model combining lodging and tuition would be reproduced by other colleges, both in Paris and other universities.

The German College, ''Collegium alemanicum'' is mentioned as early as 1345, the Scots college or ''Collegium scoticum'' was founded in 1325. The Lombard college or ''Collegium lombardicum'' was founded in the 1330s. The ''Collegium constantinopolitanum'' was, according to a tradition, founded in the 13th century to facilitate a merging of the eastern and western churches. It was later reorganized as a French institution, the ''Collège de la Marche-Winville''. The Collège de Montaigu

The Collège de Montaigu was one of the constituent colleges of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Paris.

History

The college, originally called Collège des Aicelins, was founded in 1314 by Gilles I Aycelin de Montaigu, Archbishop of Na ...

was founded by the Archbishop of Rouen

The Archdiocese of Rouen (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Rothomagensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse de Rouen'') is a Latin Church archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. As one of the fifteen Archbishops of France, the Archbishop of Rouen's ecclesi ...

in the 14th century, and reformed in the 15th century by the humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

Jan Standonck, when it attracted reformers from within the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

(such as Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

and Ignatius of Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola ( ; ; ; ; born Íñigo López de Oñaz y Loyola; – 31 July 1556), venerated as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, was a Basque Spaniard Catholic priest and theologian, who, with six companions, founded the religious order of the S ...

) and those who subsequently became Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

(John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

and John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

).

At this time, the university also went the controversy of the condemnations of 1210–1277.

The Irish College in Paris originated in 1578 with students dispersed between Collège Montaigu, Collège de Boncourt, and the Collège de Navarre; in 1677 it was awarded possession of the Collège des Lombards. A new Irish College was built in 1769 in rue du Cheval Vert (now rue des Irlandais), which exists today as the Irish Chaplaincy and Cultural centre.

15th–18th century: Influence in France and Europe

In the fifteenth century,

In the fifteenth century, Guillaume d'Estouteville

Guillaume d'Estouteville (c. 1412–1483) was a French aristocrat of royal blood who became a leading bishop (Catholic Church), bishop and cardinal (Catholic Church), cardinal. He held a number of Church offices simultaneously. He conducted th ...

, a cardinal and Apostolic legate, reformed the university, correcting its perceived abuses and introducing various modifications. This reform was less an innovation than a recall to observance of the old rules, as was the reform of 1600, undertaken by the royal government with regard to the three higher faculties. Nonetheless, and as to the faculty of arts, the reform of 1600 introduced the study of Greek, of French poets and orators, and of additional classical figures like Hesiod

Hesiod ( or ; ''Hēsíodos''; ) was an ancient Greece, Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.M. L. West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', Oxford University Press (1966), p. 40.Jasper Gr ...

, Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; ; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prowess and provide insight into the politics and cu ...

, Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

, Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

, and Sallust

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (, ; –35 BC), was a historian and politician of the Roman Republic from a plebeian family. Probably born at Amiternum in the country of the Sabines, Sallust became a partisan of Julius ...

. The prohibition from teaching civil law was never well observed at Paris, but in 1679 Louis XIV officially authorized the teaching of civil law in the faculty of decretal

Decretals () are letters of a pope that formulate decisions in canon law (Catholic Church), ecclesiastical law of the Catholic Church.McGurk. ''Dictionary of Medieval Terms''. p. 10

They are generally given in answer to consultations but are some ...

s. The "faculty of law" hence replaced the "faculty of decretals". The colleges meantime had multiplied; those of Cardinal Le-Moine and Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

were founded in the fourteenth century. The Hundred Years' War was fatal to these establishments, but the university set about remedying the injury.

Besides its teaching, the University of Paris played an important part in several disputes: in the Church, during the Great Schism; in the councils, in dealing with heresies and divisions; in the State, during national crises. Under the domination of England it played a role in the trial of Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc ( ; ; – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the Coronation of the French monarch, coronation of Charles VII o ...

.

Proud of its rights and privileges, the University of Paris fought energetically to maintain them, hence the long struggle against the mendicant orders on academic as well as on religious grounds. Hence also the shorter conflict against the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

, who claimed by word and action a share in its teaching. It made extensive use of its right to decide administratively according to occasion and necessity. In some instances it openly endorsed the censures of the faculty of theology and pronounced condemnation in its own name, as in the case of the Flagellants.

Its patriotism was especially manifested on two occasions. During the captivity of King John, when Paris was given over to factions, the university sought to restore peace; and under LouisXIV, when the Spaniards crossed the Somme and threatened the capital, it placed two hundred men at the king's disposal and offered the Master of Arts degree gratuitously to scholars who should present certificates of service in the army (Jourdain, ''Hist. de l'Univers. de Paris au XVIIe et XVIIIe siècle'', 132–34; ''Archiv. du ministère de l'instruction publique'').

1793: Abolition by the French Revolution

The ancient university disappeared with the

The ancient university disappeared with the ancien régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

in the French Revolution. On 15 September 1793, petitioned by the Department of Paris and several departmental groups, the National Convention

The National Convention () was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the ...

decided that independently of the primary schools, "there should be established in the Republic three progressive degrees of instruction; the first for the knowledge indispensable to artisans and workmen of all kinds; the second for further knowledge necessary to those intending to embrace the other professions of society; and the third for those branches of instruction the study of which is not within the reach of all men".Measures were to be taken immediately: "For means of execution the department and the municipality of Paris are authorized to consult with the Committee of Public Instruction of the National Convention, in order that these establishments shall be put in action by 1 November next, and consequently colleges now in operation and the faculties of theology, medicine, arts, and law are suppressed throughout the Republic". This was the death-sentence of the university. It was not to be restored after the Revolution had subsided, no more than those of the provinces.

1806–1968: Re-establishment

The university was re-established byNapoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

on 1 May 1806. All the faculties were replaced by a single centre, the University of France

The University of France (; originally the ''Imperial University of France'') was a highly centralized educational state organization founded by Napoleon I in 1806 and given authority not only over the individual (previously independent) universiti ...

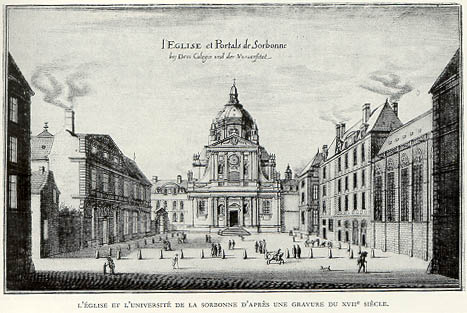

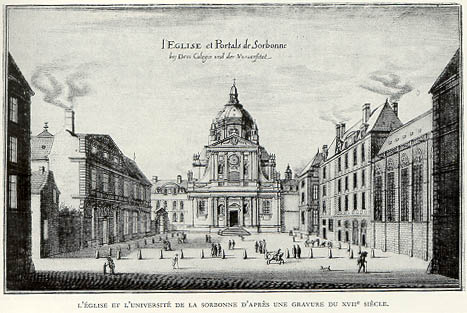

. The decree of 17 March 1808 created five distinct faculties: Law, Medicine, Letters/Humanities, Sciences, and Theology; traditionally, Letters and Sciences had been grouped together into one faculty, that of "Arts". After a century, people recognized that the new system was less favourable to study. The defeat of 1870 at the hands of Prussia was partially blamed on the growth of the superiority of the German university system of the 19th century, and led to another serious reform of the French university. In the 1880s, the "licence" (bachelor) degree is divided into, for the Faculty of Letters: Letters, Philosophy, History, Modern Languages, with French, Latin and Greek being requirements for all of them; and for the Faculty of Science, into: Mathematics, Physical Sciences and Natural Sciences; the Faculty of Theology is abolished by the Republic. At this time, the building of the Sorbonne was fully renovated.

May 1968–1970: Shutdown

The student revolts of the late 1960s were caused in part by the French government's failure to plan for a sudden spike in the number of university students as a result of the postwar baby boom. The number of French university students skyrocketed from only 280,000 during the 1962–63 academic year to 500,000 in 1967–68, but at the start of the decade, there were only 16 public universities in the entire country. To accommodate this rapid growth, the government hastily developed bare-bones off-site faculties as annexes of existing universities (roughly equivalent to Americansatellite campus

A satellite campus, branch campus or regional campus is a campus of a university or college that is physically at a distance from the original university or college area. This branch campus may be located in a different city, state, or country, ...

es). These faculties did not have university status of their own and lacked academic traditions and amenities to support student life or resident professors. One-third of all French university students ended up in these new faculties, and were ripe for radicalization as a result of being forced to pursue their studies in such shabby conditions.

In 1966, after a student revolt in Paris, Christian Fouchet

Christian Fouchet (; 17 November 1911 – 11 August 1974) was a French politician.

Biography

He was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Yvelines. He was a graduate of the Ecole des sciences politiques.

After Marshal Petain's request for an armis ...

, minister of education, proposed "the reorganisation of university studies into separate two- and four-year degrees, alongside the introduction of selective admission criteria" as a response to overcrowding in lecture halls. Dissatisfied with these educational reforms, students began protesting in November 1967, at the campus of the University of Paris in Nanterre

Nanterre (; ) is the prefecture of the Hauts-de-Seine department in the western suburbs of Paris, France. It is located some northwest of the centre of Paris. In 2018, the commune had a population of 96,807.

The eastern part of Nanterre, b ...

; indeed, according to James Marshall, these reforms were seen "as the manifestations of the technocratic-capitalist state by some, and by others as attempts to destroy the liberal university". After student activists protested against the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, the campus was closed by authorities on 22 March and again on 2 May 1968. Agitation spread to the Sorbonne the next day, and many students were arrested in the following week. Barricades were erected throughout the Latin Quarter

The Latin Quarter of Paris (, ) is an urban university campus in the 5th and the 6th arrondissements of Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine, around the Sorbonne.

Known for its student life, lively atmosphere, and bistros, t ...

, and a massive demonstration took place on 13 May, gathering students and workers on strike. The number of workers on strike reached about nine million by 22 May. As explained by Bill Readings:

De Gaulle Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...responded on May 24 by calling for a referendum, and ..the revolutionaries, led by informal action committees, attacked and burned theParis Stock Exchange Euronext Paris, formerly known as the Paris Bourse (), is a regulated securities trading venue in France. It is Europe's second largest stock exchange by market capitalization, behind the London Stock Exchange, as of December 2023. As of 2022, th ...in response. TheGaullist Gaullism ( ) is a French political stance based on the thought and action of World War II French Resistance leader Charles de Gaulle, who would become the founding President of the Fifth French Republic. De Gaulle withdrew French forces from t ...government then held talks with union leaders, who agreed to a package of wage-rises and increases in union rights. The strikers, however, simply refused the plan. With the French state tottering, de Gaulle fled France on May 29 for a French military base in Germany. He later returned and, with the assurance of military support, announced eneralelections ithinforty days. ..Over the next two months, the strikes were broken (or broke up) while the election was won by the Gaullists with an increased majority.

1970: Dissolution

Following the disruption, de Gaulle appointed Edgar Faure as minister of education; Faure was assigned to prepare a legislative proposal for reform of the French university system, with the help of academics.Berstein, p. 229. Their proposal was adopted on 12 November 1968;Berstein, p. 229; . in accordance with the new law, the faculties of the University of Paris were to reorganize themselves.Conac, p. 177. This led to the division of the University of Paris into 13 universities. In 2017, Paris 4 and Paris 6 universities merged to form theSorbonne University

Sorbonne University () is a public research university located in Paris, France. The institution's legacy reaches back to the Middle Ages in 1257 when Sorbonne College was established by Robert de Sorbon as a constituent college of the Unive ...

. In 2019, Paris 5 and Paris 7 universities merged to form the new Paris Cité University, leaving the number of successor universities at 11.

The successor universities to the University of Paris are now split over of the Île-de-France

The Île-de-France (; ; ) is the most populous of the eighteen regions of France, with an official estimated population of 12,271,794 residents on 1 January 2023. Centered on the capital Paris, it is located in the north-central part of the cou ...

region.

Most of these successor universities have joined several groups of universities and higher education institutions in the Paris region, created in the 2010s.

Notable people

Faculty

Bonaventure

Bonaventure ( ; ; ; born Giovanni di Fidanza; 1221 – 15 July 1274) was an Italian Catholic Franciscan bishop, Cardinal (Catholic Church), cardinal, Scholasticism, scholastic theologian and philosopher.

The seventh Minister General ( ...

File:Guizot,_Fran%C3%A7ois_-_2.jpg, François Guizot