Tweed Ring on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

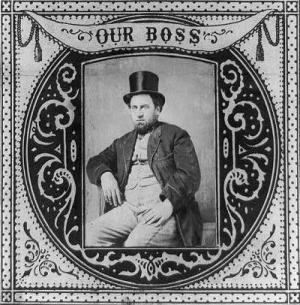

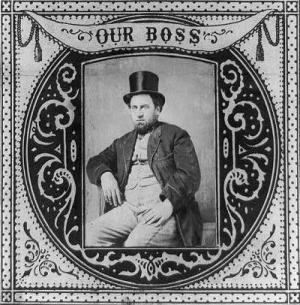

William Magear "Boss" Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878) was an American politician most notable for being the

Tweed became a member of the

Tweed became a member of the  With his new position and wealth came a change in style: Tweed began to favor wearing a large diamond in his shirtfront – a habit that

With his new position and wealth came a change in style: Tweed began to favor wearing a large diamond in his shirtfront – a habit that

''

"Assassin's Creed: Last Descendants Novels Announced"

''IGN''.

online

Encyclopedia.com (

"Boss Tweed"

'' Gotham Gazette''

1927 1st edition

published by

Green-Wood Cemetery page for WM Tweed

Map Showing the Portions of the City of New York and Westchester County under the Jurisdiction of the Department of Public Parks

talks about Tweed's takeover of the New York City parks system, from the

political boss

In the politics of the United States of America, a boss is a person who controls a faction or local branch of a political party. They do not necessarily hold public office themselves; most historical bosses did not, at least during the times of th ...

of Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. It became the main local ...

, the Democratic Party's political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership c ...

that played a major role in the politics of 19th-century New York City and State

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

.

At the height of his influence, Tweed was the third-largest landowner in New York City, a director of the Erie Railroad

The Erie Railroad was a railroad that operated in the Northeastern United States, originally connecting Pavonia Terminal in Jersey City, New Jersey, with Lake Erie at Dunkirk, New York. The railroad expanded west to Chicago following its 1865 ...

, a director of the Tenth National Bank, a director of the New-York Printing Company, the proprietor of the Metropolitan Hotel, a significant stockholder in iron mines and gas companies, a board member of the Harlem Gas Light Company, a board member of the Third Avenue Railway Company, a board member of the Brooklyn Bridge Company, and the president of the Guardian Savings Bank.

Tweed was elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

in 1852 and the New York County

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the smallest county by area in the U.S. state of New York. Located almost entire ...

Board of Supervisors in 1858, the year that he became the head of the Tammany Hall political machine. He was also elected to the New York State Senate

The New York State Senate is the upper house of the New York State Legislature, while the New York State Assembly is its lower house. Established in 1777 by the Constitution of New York, its members are elected to two-year terms with no term l ...

in 1867. However, Tweed's greatest influence came from being an appointed member of a number of boards and commissions, his control over political patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

in New York City through Tammany, and his ability to ensure the loyalty of voters through jobs he could create and dispense on city-related projects.

Boss Tweed was convicted for stealing an amount estimated by an aldermen's committee in 1877 at between $25 million and $45 million from New York City taxpayers by political corruption, but later estimates ranged as high as $200 million (equivalent to $ billion in ). Unable to make bail, he escaped from jail once but was returned to custody. He died in the Ludlow Street Jail.

Early life and education

Tweed was born April 3, 1823, at 1 Cherry Street,Share, Allen J. "Tweed, William M(agear) 'Boss'" in , pp. 1205–1206. on theLower East Side

The Lower East Side, sometimes abbreviated as LES, is a historic neighborhood in the southeastern part of Manhattan in New York City. It is located roughly between the Bowery and the East River from Canal to Houston streets. Historically, it w ...

of Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

. The son of a third-generation Scottish chair-maker, Tweed grew up on Cherry Street. His grandfather arrived in the United States from a town near the River Tweed

The River Tweed, or Tweed Water, is a river long that flows east across the Border region in Scotland and northern England. Tweed cloth derives its name from its association with the River Tweed. The Tweed is one of the great salmon rivers ...

close to Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

. Tweed's religious affiliation was not widely known in his lifetime, but at the time of his funeral ''The New York Times'', quoting a family friend, reported that his parents had been Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

and "members of the old Rose Street Meeting house". At the age of 11, he left school to learn his father's trade, and then became an apprentice to a saddler. He also studied to be a bookkeeper and worked as a brushmaker for a company he had invested in, before eventually joining in the family business in 1852. On September 29, 1844, he married Mary Jane C. Skaden and lived with her family on Madison Street for two years.

Early career

Tweed became a member of the

Tweed became a member of the Odd Fellows

Odd Fellows (or Oddfellows when referencing the Grand United Order of Oddfellows or some British-based fraternities; also Odd Fellowship or Oddfellowship) is an international fraternity consisting of lodges first documented in 1730 in 18th-cen ...

and the Masons, and joined a volunteer fire company, Engine No. 12. In 1848, at the invitation of state assemblyman John J. Reilly, he and some friends organized the Americus Fire Company No. 6, also known as the "Big Six", as a volunteer fire company, which took as its symbol a snarling red Bengal tiger

The Bengal tiger is a population of the ''Panthera tigris tigris'' subspecies and the nominate tiger subspecies. It ranks among the largest wild cats alive today. It is estimated to have been present in the Indian subcontinent since the Late ...

from a French lithograph, a symbol which remained associated with Tweed and Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. It became the main local ...

for many years. At the time, volunteer fire companies competed vigorously with each other; some were connected with street gangs and had strong ethnic ties to various immigrant communities. The competition could become so fierce, that burning buildings would sometimes be ignored as the fire companies fought each other. Tweed became known for his ax-wielding violence, and was soon elected the Big Six foreman. Pressure from Alfred Carlson, the chief engineer, got him thrown out of the crew. However, fire companies were also recruiting grounds for political parties at the time, thus Tweed's exploits came to the attention of the Democratic politicians who ran the Seventh Ward. The Seventh Ward put him up for Alderman in 1850, when Tweed was 26. He lost that election to the Whig candidate Morgan Morgans, but ran again the next year and won, garnering his first political position. Tweed then became associated with the "Forty Thieves", the group of aldermen and assistant aldermen who, up to that point, were known as some of the most corrupt politicians in the city's history.

Tweed was elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

in 1852, but his two-year term was undistinguished.Burrows & Wallace, p. 837. In an attempt by Republican reformers in Albany, the state capital, to control the Democratic-dominated New York City government, the power of the New York County Board of Supervisors was beefed up. The board had 12 members, six appointed by the mayor and six elected, and in 1858 Tweed was appointed to the board, which became his first vehicle for large-scale graft

Graft or grafting may refer to:

*Graft (politics), a form of political corruption

*Graft, Netherlands, a village in the municipality of Graft-De Rijp

Science and technology

*Graft (surgery), a surgical procedure

*Grafting, the joining of plant ti ...

; Tweed and other supervisors forced vendors to pay a 15% overcharge to their "ring" in order to do business with the city. By 1853, Tweed was running the seventh ward for Tammany. The board also had six Democrats and six Republicans, but Tweed often just bought off one Republican to sway the board. One such Republican board member was Peter P. Voorhis, a coal dealer by profession who absented himself from a board meeting in exchange for $2,500 so that the board could appoint city inspectors. Henry Smith was another Republican that was a part of the Tweed ring.

Although he was not trained as a lawyer, Tweed's friend, Judge George G. Barnard, certified him as an attorney, and Tweed opened a law office on Duane Street. He ran for sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland, the , which is common ...

in 1861 and was defeated, but became the chairman of the Democratic General Committee shortly after the election, and was then chosen to be the head of Tammany's general committee in January 1863. Several months later, in April, he became "Grand Sachem", and began to be referred to as "Boss", especially after he tightened his hold on power by creating a small executive committee to run the club. Tweed then took steps to increase his income: he used his law firm to extort money, which was then disguised as legal services; he had himself appointed deputy street commissioner – a position with considerable access to city contractors and funding; he bought the New-York Printing Company, which became the city's official printer, and the city's stationery supplier, the Manufacturing Stationers' Company, and had both companies begin to overcharge the city government for their goods and services. Among other legal services he provided, he accepted almost $100,000 from the Erie Railroad in return for favors. He also became one of the largest owners of real estate in the city. He also started to form what became known as the "Tweed Ring", by having his friends elected to office: George G. Barnard was elected Recorder of New York City; Peter B. Sweeny was elected New York County District Attorney

The New York County District Attorney, also known as the Manhattan District Attorney, is the elected district attorney for New York County, New York. The office is responsible for the prosecution of violations of New York state laws (federal l ...

; and Richard B. Connolly was elected City Comptroller. Other judicial members of the Tweed ring included Albert Cardozo, John McCunn, and John K. Hackett.

When Grand Sachem Isaac Fowler, who had produced the $2,500 to buy off the Republican Voorhis on the Board of Supervisors, was found to have stolen $150,000 in post office receipts, the responsibility for Fowler's arrest was given to Isaiah Rynders, another Tammany operative who was serving as a United States marshal at the time. Rynders made enough ruckus upon entering the hotel where Fowler was staying that Fowler was able to escape to Mexico.

With his new position and wealth came a change in style: Tweed began to favor wearing a large diamond in his shirtfront – a habit that

With his new position and wealth came a change in style: Tweed began to favor wearing a large diamond in his shirtfront – a habit that Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast (; ; September 26, 1840December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon".

He was a sharp critic of William M. Tweed, "Boss" Tweed and the T ...

used to great effect in his attacks on Tweed in ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper (publisher), Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many su ...

'' beginning in 1869 – and he bought a brownstone

Brownstone is a brown Triassic–Jurassic sandstone that was historically a popular building material. The term is also used in the United States and Canada to refer to a townhouse clad in this or any other aesthetically similar material.

Ty ...

to live in at 41 West 36th Street, then a very fashionable area. He invested his now considerable illegal income in real estate, so that by the late 1860s he ranked among the biggest landowners in New York City.

Tweed became involved in the operation of the New York Mutuals, an early professional baseball

Professional baseball is organized baseball in which players are selected for their talents and are paid to play for a specific team or club system. It is played in baseball league, leagues and associated farm teams throughout the world.

Moder ...

club, in the 1860s. He brought in thousands of dollars per home game by dramatically increasing the cost of admission and gambling

Gambling (also known as betting or gaming) is the wagering of something of Value (economics), value ("the stakes") on a Event (probability theory), random event with the intent of winning something else of value, where instances of strategy (ga ...

on the team. He has been credited with originating the practice of spring training

Spring training, also called spring camp, is the preseason of the Summer Professional Baseball Leagues, such as Major League Baseball (MLB), and it is a series of practices and exhibition games preceding the start of the regular season. Spri ...

in 1869 by sending the club south to New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

to prepare for the season.

Tweed was a member of the New York State Senate

The New York State Senate is the upper house of the New York State Legislature, while the New York State Assembly is its lower house. Established in 1777 by the Constitution of New York, its members are elected to two-year terms with no term l ...

(4th D.) from 1868 to 1873, sitting in the 91st, 92nd, 93rd, and 94th New York State Legislatures, but not taking his seat in the 95th and 96th New York State Legislatures. While serving in the State Senate, he split his time between Albany, New York and New York City. While in Albany, he stayed in a suite of seven rooms in Delevan House. Accompanying him in his rooms were his favorite canaries. Guests are presumed to have included members of the Black Horse Cavalry, thirty state legislators whose votes were up for sale. In the Senate he helped financiers Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who founded the Gould family, Gould business dynasty. He is generally identified as one of the Robber baron (industrialist), robber bar ...

and Big Jim Fisk

James Fisk Jr. (April 1, 1835 – January 7, 1872), known variously as "Big Jim", "Diamond Jim", and "Jubilee Jim" – was an American stockbroker and corporate executive who has been referred to as one of the "robber baron (industrialist), robb ...

to take control of the Erie Railroad

The Erie Railroad was a railroad that operated in the Northeastern United States, originally connecting Pavonia Terminal in Jersey City, New Jersey, with Lake Erie at Dunkirk, New York. The railroad expanded west to Chicago following its 1865 ...

from Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

by arranging for legislation that legitimized fake Erie stock certificates that Gould and Fisk had issued. In return, Tweed received a large block of stock and was made a director of the company. Tweed was also subsequently elected to the board of the Gould-controlled Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad (future Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad ( reporting mark PRR), legal name as the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, also known as the "Pennsy," was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At its ...

) in January 1870.

Corruption

After the election of 1869, Tweed took control of the New York City government. His protégé, John T. Hoffman, the former mayor of the city, won election as governor, and Tweed garnered the support of good-government reformers likePeter Cooper

Peter Cooper (February 12, 1791April 4, 1883) was an American industrialist, inventor, philanthropist, and politician. He designed and built the first American steam locomotive, the ''Tom Thumb (locomotive), Tom Thumb'', founded the Cooper Union ...

and the Union League Club, by proposing a new city charter which returned power to City Hall at the expense of the Republican-inspired state commissions. The new charter passed, thanks in part to $600,000 in bribes Tweed paid to Republicans, and was signed into law by Hoffman in 1870. Mandated new elections allowed Tammany to take over the city's Common Council when they won all fifteen aldermanic contests.Burrows & Wallace, pp. 927–928.

The new charter put control of the city's finances in the hands of a Board of Audit, which consisted of Tweed, who was Commissioner of Public Works, Mayor A. Oakey Hall and Comptroller Richard "Slippery Dick" Connolly, both Tammany men. Hall also appointed other Tweed associates to high offices – such as Peter B. Sweeny, who took over the Department of Public Parks – providing what became known as the Tweed Ring with even firmer control of the New York City government and enabling them to defraud the taxpayers of many more millions of dollars. In the words of Albert Bigelow Paine, "their methods were curiously simple and primitive. There were no skilful manipulations of figures, making detection difficult ... Connolly, as Controller, had charge of the books, and declined to show them. With his fellows, he also 'controlled' the courts and most of the bar." Crucially, the new city charter allowed the Board of Audit to issue bonds for debt in order to finance opportunistic capital expenditures the city otherwise could not afford. This ability to float debt was enabled by Tweed's guidance and passage of the Adjusted Claims Act in 1868. Contractors working for the city – "Ring favorites, most of them – were told to multiply the amount of each bill by five, or ten, or a hundred, after which, with Mayor Hall's 'O. K.' and Connolly's endorsement, it was paid ... through a go-between, who cashed the check, settled the original bill and divided the remainder ... between Tweed, Sweeny, Connolly and Hall".

For example, the construction cost of the New York County Courthouse, begun in 1861, grew to nearly $13 million—about $ in dollars, and nearly twice the cost of the Alaska Purchase

The Alaska Purchase was the purchase of Russian colonization of North America, Alaska from the Russian Empire by the United States for a sum of $7.2 million in 1867 (equivalent to $ million in ). On May 15 of that year, the United St ...

in 1867.

"A carpenter was paid $360,751 (roughly $ in ) for one month's labor in a building with very little woodwork ... a plasterer got $133,187 ($) for two days' work". Tweed bought a marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock consisting of carbonate minerals (most commonly calcite (CaCO3) or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) that have recrystallized under the influence of heat and pressure. It has a crystalline texture, and is ty ...

quarry in Sheffield, Massachusetts, to provide much of the marble for the courthouse at great profit to himself. After the Tweed Charter to reorganize the city's government was passed in 1870, four commissioners for the construction of the New York County Courthouse were appointed. The commission never held a meeting, though each commissioner received a 20% kickback from the bills for the supplies.

Tweed and his friends also garnered huge profits from the development of the Upper East Side, especially Yorkville and Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater ...

. They would buy up undeveloped property, then use the resources of the city to improve the area – for instance by installing pipes to bring in water from the Croton Aqueduct

The Croton Aqueduct or Old Croton Aqueduct was a large and complex water supply network, water distribution system constructed for New York City between 1837 and 1842. The great aqueduct (water supply), aqueducts, which were among the first in t ...

– thus increasing the value of the land, after which they sold and took their profits. The focus on the east side also slowed down the development of the west side, the topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the landforms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

of which made it more expensive to improve. The ring also took their usual percentage of padded contracts, as well as raking off money from property taxes. Despite the corruption of Tweed and Tammany Hall, they did accomplish the development of upper Manhattan, though at the cost of tripling the city's bond debt to almost $90 million.

During the Tweed era, the proposal to build a suspension bridge between New York and Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

, then an independent city, was floated by Brooklyn-boosters, who saw the ferry connections as a bottleneck to Brooklyn's further development. In order to ensure that the Brooklyn Bridge

The Brooklyn Bridge is a cable-stayed suspension bridge in New York City, spanning the East River between the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn. Opened on May 24, 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge was the first fixed crossing of the East River. It w ...

project would go forward, State Senator Henry Cruse Murphy approached Tweed to find out whether New York's aldermen would approve the proposal. Tweed's response was that $60,000 for the aldermen would close the deal, and contractor William C. Kingsley put up the cash, which was delivered in a carpet bag

A carpet bag is a top-opening travelling bag made of carpet, commonly from an oriental rug. It was a popular form of luggage in the United States and Europe in the 19th century, featuring simple handles and only an upper frame, which serve ...

. Tweed and two others from Tammany also received over half the private stock of the Bridge Company, the charter of which specified that only private stockholders had voting rights, so that even though the cities of Brooklyn and Manhattan put up most of the money, they essentially had no control over the project.

Tweed bought a mansion on Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major thoroughfare in the borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan in New York City. The avenue runs south from 143rd Street (Manhattan), West 143rd Street in Harlem to Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. The se ...

and 43rd Street, and stabled his horses, carriages and sleighs on 40th Street. By 1871, he was a member of the board of directors of not only the Erie Railroad and the Brooklyn Bridge Company, but also the Third Avenue Railway Company and the Harlem Gas Light Company. He was president of the Guardian Savings Banks and he and his confederates set up the Tenth National Bank to better control their fortunes.

Scandal

Tweed's downfall began in 1871. James Watson, who was a county auditor in Comptroller Dick Connolly's office and who also held and recorded the ring's books, died a week after his head was smashed by a horse in a sleigh accident on January 24, 1871. Although Tweed guarded Watson's estate in the week prior to Watson's death, and although another ring member attempted to destroy Watson's records, a replacement auditor, Matthew O'Rourke, associated with former sheriff James O'Brien, provided city accounts to O'Brien. The Orange riot of 1871 in the summer of that year did not help the ring's popularity. The riot was prompted after Tammany Hall banned a parade of Irish Protestants celebrating a historical victory against Catholicism, namely theBattle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne ( ) took place in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II, and those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and James's daughter), had acceded to the Crowns of England and Sc ...

. The parade was banned because of a riot the previous year in which eight people died when a crowd of Irish Catholic laborers attacked the paraders. Under strong pressure from the newspapers and the Protestant elite of the city, Tammany reversed course, and the march was allowed to proceed, with protection from city policemen and state militia. The result was an even larger riot in which over 60 people were killed and more than 150 injured.Burrows & Wallace, pp. 1003–1008.

Although Tammany's electoral power base was largely centered in the Irish immigrant population, it also needed both the city's general population and elite to acquiesce in its rule, and this was conditional on the machine's ability to control the actions of its people. The July riot showed that this capability was not nearly as strong as had been supposed.

Tweed had for months been under attack from ''The New York Times'' and Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast (; ; September 26, 1840December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon".

He was a sharp critic of William M. Tweed, "Boss" Tweed and the T ...

, the cartoonist from ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper (publisher), Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many su ...

'' – regarding Nast's cartoons, Tweed reportedly said, "Stop them damned pictures. I don't care so much what the papers say about me. My constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them damned pictures!" – but their campaign had only limited success in gaining traction. They were able to force an examination of the city's books, but the blue-ribbon commission of six businessmen appointed by Mayor A. Oakey Hall, a Tammany man, which included John Jacob Astor III, banker Moses Taylor and others who benefited from Tammany's actions, found that the books had been "faithfully kept", letting the air out of the effort to dethrone Tweed.Burrows & Wallace, pp. 1008–1011.

The response to the Orange riot changed everything, and only days afterwards the ''Times''/Nast campaign began to garner popular support. More important, the ''Times'' started to receive inside information from County Sheriff James O'Brien, whose support for Tweed had fluctuated during Tammany's reign. O'Brien had tried to blackmail

Blackmail is a criminal act of coercion using a threat.

As a criminal offense, blackmail is defined in various ways in common law jurisdictions. In the United States, blackmail is generally defined as a crime of information, involving a thr ...

Tammany by threatening to expose the ring's embezzlement

Embezzlement (from Anglo-Norman, from Old French ''besillier'' ("to torment, etc."), of unknown origin) is a type of financial crime, usually involving theft of money from a business or employer. It often involves a trusted individual taking ...

to the press, and when this failed he provided the evidence he had collected to the ''Times''.Ellis, pp. 347–348. Shortly afterward, county auditor Matthew J. O'Rourke supplied additional details to the ''Times'', which was reportedly offered $5 million to not publish the evidence. The ''Times'' also obtained the accounts of the recently deceased James Watson, who was the Tweed Ring's bookkeeper, and these were published daily, culminating in a special four-page supplement on July 29 headlined "Gigantic Frauds of the Ring Exposed". In August, Tweed began to transfer ownership in his real-estate empire and other investments to his family members.

The exposé provoked an international crisis of confidence in New York City's finances, and, in particular, in its ability to repay its debts. European investors were heavily positioned in the city's bonds and were already nervous about its management – only the reputations of the underwriters were preventing a run on the city's securities. New York's financial and business community knew that if the city's credit were to collapse, it could potentially bring down every bank in the city with it.

Thus, the city's elite met at Cooper Union

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, commonly known as Cooper Union, is a private college on Cooper Square in Lower Manhattan, New York City. Peter Cooper founded the institution in 1859 after learning about the government-s ...

in September to discuss political reform: but for the first time, the conversation included not only the usual reformers, but also Democratic bigwigs such as Samuel J. Tilden, who had been thrust aside by Tammany. The consensus was that the "wisest and best citizens" should take over the governance of the city and attempt to restore investor confidence. The result was the formation of the executive committee of Citizens and Taxpayers for Financial Reform of the city (also known as "the Committee of Seventy"), which attacked Tammany by cutting off the city's funding. Property owners refused to pay their municipal taxes, and a judge—Tweed's old friend George Barnard—enjoined the city Comptroller from issuing bonds or spending money. Unpaid workers turned against Tweed, marching to City Hall demanding to be paid. Tweed doled out some funds from his own purse—$50,000—but it was not sufficient to end the crisis, and Tammany began to lose its essential base.

Shortly thereafter, the Comptroller resigned, appointing Andrew Haswell Green

Andrew Haswell Green (October 6, 1820 – November 13, 1903) was an American lawyer, city planner, and civic leader who was influential in the development of New York City. Green was responsible for Central Park, the New York Public Library, ...

, an associate of Tilden, as his replacement. Green loosened the purse strings again, allowing city departments not under Tammany control to borrow money to operate. Green and Tilden had the city's records closely examined, and discovered money that went directly from city contractors into Tweed's pocket. The following day, they had Tweed arrested.

Imprisonment, escape, and death

Tweed was released on $1 million bail, and Tammany set to work to recover its position through the ballot box. Tweed was re-elected to the state senate in November 1871, due to his personal popularity and largesse in his district, but in general Tammany did not do well, and the members of the Tweed Ring began to flee the jurisdiction, many going overseas. Tweed was re-arrested, forced to resign his city positions, and was replaced as Tammany's leader. Once again, he was released on bail—$8 million this time—but Tweed's supporters, such asJay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who founded the Gould family, Gould business dynasty. He is generally identified as one of the Robber baron (industrialist), robber bar ...

, felt the repercussions of his fall from power.

Tweed's first trial before Judge Noah Davis, in January 1873, ended when the jury was unable to deliver a verdict. Tweed's defense counsel included David Dudley Field II

David Dudley Field II (February 13, 1805April 13, 1894) was an American lawyer and law reformer who made major contributions to the development of American civil procedure. His greatest accomplishment was engineering the move away from common ...

and Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican Party (United States), Republican politician, and statesman who served as the 41st United States Secretary of War under presidents William McKinley and Theodor ...

. His retrial, again before Judge Noah Davis in November resulted in convictions on 204 of 220 counts, a fine of $12,750 (the equivalent of $ today) and a prison sentence of 12 years; a higher court, however, reduced Tweed's sentence to one year. After his release from The Tombs

The Tombs was the colloquial name for Manhattan Detention Complex (formerly the Bernard B. Kerik Complex during 2001–2006), a former municipal jail at 125 White Street in Lower Manhattan, New York City. It was also the nickname for three prev ...

prison, New York State filed a civil suit

A lawsuit is a proceeding by one or more parties (the plaintiff or claimant) against one or more parties (the defendant) in a civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. T ...

against Tweed, attempting to recover $6 million in embezzled funds. Unable to put up the $3 million bail, Tweed was locked up in the Ludlow Street Jail, although he was allowed home visits. During one of these on December 4, 1875, Tweed escaped and fled to Spain, where he worked as a common seaman on a Spanish ship. The U.S. government discovered his whereabouts and arranged for his arrest once he reached the Spanish border, where he was recognized from Nast's political cartoons. He was turned over to an American warship, the , which delivered him to authorities in New York City on November 23, 1876, and he was returned to prison."'Boss' Tweed Delivered to Authorities"''

History Channel

History (formerly and commonly known as the History Channel) is an American pay television television broadcaster, network and the flagship channel of A&E Networks, a joint venture between Hearst Communications and the Disney General Entertainme ...

'' website, n.d.g. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

Desperate and broken, Tweed now agreed to testify about the inner workings of the Tweed Ring to a special committee set up by the Board of Aldermen in return for his release. However, after he did so, Tilden, now governor of New York, refused to abide by the agreement, and Tweed remained incarcerated.

Death and burial

He died in the Ludlow Street Jail on April 12, 1878, from severepneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

, and was buried in Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

's Green-Wood Cemetery

Green-Wood Cemetery is a cemetery in the western portion of Brooklyn, New York City. The cemetery is located between South Slope, Brooklyn, South Slope/Greenwood Heights, Brooklyn, Greenwood Heights, Park Slope, Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn, Win ...

. Mayor Smith Ely Jr. would not allow the flag at City Hall to be flown at half staff

Half-mast or half-staff (American English) refers to a flag flying below the summit of a ship mast, a pole on land, or a pole on a building. In many countries this is seen as a symbol of respect, mourning, distress signal, distress, or, in so ...

.

Evaluations

According to Tweed biographer Kenneth D. Ackerman:It's hard not to admire the skill behind Tweed's system ... The Tweed ring at its height was an engineering marvel, strong and solid, strategically deployed to control key power points: the courts, the legislature, the treasury and the ballot box. Its frauds had a grandeur of scale and an elegance of structure: money-laundering, profit sharing and organization.A minority view that Tweed was mostly innocent is presented in a scholarly biography by history professor Leo Hershkowitz. He states:

Except for Tweed's own very questionable "confession," there really was no evidence of a "Tweed Ring," no direct evidence of Tweed's thievery, no evidence, excepting the testimony of the informer contractors, of "wholesale" plunder by Tweed.... nstead there wasa conspiracy of self-justification of the corruption of the law by the upholders of that law, of a venal irresponsible press and a citizenry delighting in the exorcism of witchery.In depictions of Tweed and the Tammany Hall organization, most historians have emphasized the thievery and conspiratorial nature of Boss Tweed, along with lining his own pockets and those of his friends and allies. The theme is that the sins of corruption so violated American standards of political rectitude that they far overshadow Tweed's positive contributions to New York City. Although he held numerous important public offices and was one of a handful of senior leaders of Tammany Hall, as well as the state legislature and the state Democratic Party, Tweed was never the sole "boss" of New York City. He shared control of the city with numerous less famous people, such as the villains depicted in Nast's famous circle of guilt cartoon shown above. Seymour J. Mandelbaum has argued that, apart from the corruption he engaged in, Tweed was a modernizer who prefigured certain elements of the

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) was a period in the United States characterized by multiple social and political reform efforts. Reformers during this era, known as progressivism in the United States, Progressives, sought to address iss ...

in terms of more efficient city management. Much of the money he siphoned off from the city treasury went to needy constituents who appreciated the free food at Christmas time and remembered it at the next election, and to precinct workers who provided the muscle of his machine. As a legislator he worked to expand and strengthen welfare programs, especially those by private charities, schools, and hospitals. With a base in the Irish Catholic community, he opposed efforts of Protestants to require the reading of the King James Bible

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version (AV), is an Early Modern English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by ...

in public schools, which was done deliberately to keep out Catholics. He facilitated the founding of the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second-largest public library in the United States behind the Library of Congress a ...

, even though one of its founders, Samuel Tilden, was Tweed's sworn enemy in the Democratic Party.

Tweed recognized that the support of his constituency was necessary for him to remain in power, and as a consequence he used the machinery of the city's government to provide numerous social services, including building more orphanages, almshouses and public baths. Tweed also fought for the New York State Legislature

The New York State Legislature consists of the Bicameralism, two houses that act as the State legislature (United States), state legislature of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York: the New York State Senate and the New York State Assem ...

to donate to private charities of all religious denominations, and subsidize Catholic schools

Catholic schools are parochial pre-primary, primary and secondary educational institutions administered in association with the Catholic Church. , the Catholic Church operates the world's largest religious, non-governmental school system. In 201 ...

and hospitals. From 1869 to 1871, under Tweed's influence, the state of New York spent more on charities than for the entire time period from 1852 to 1868 combined.

During Tweed's regime, the main business thoroughfare Broadway was widened between 34th Street 34th Street most commonly refers to 34th Street (Manhattan)

34th Street is a major crosstown street in the New York City borough of Manhattan. It runs the width of Manhattan Island from the West Side Highway on the West Side to FDR Drive on t ...

and 59th Street, land was secured for the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an Encyclopedic museum, encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the List of largest museums, third-largest museum in the world and the List of larg ...

, and the Upper East Side

The Upper East Side, sometimes abbreviated UES, is a neighborhood in the boroughs of New York City, borough of Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded approximately by 96th Street (Manhattan), 96th Street to the north, the East River to the e ...

and Upper West Side

The Upper West Side (UWS) is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Central Park on the east, the Hudson River on the west, West 59th Street to the south, and West 110th Street to the north. The Upper We ...

were developed and provided the necessary infrastructure – all to the benefit of the purses of the Tweed Ring.

Hershkowitz blames the implications of Thomas Nast in ''Harper's Weekly'' and the editors of ''The New York Times'', which both had ties to the Republican party. In part, the campaign against Tweed diverted public attention from Republican scandals such as the Whiskey Ring

The Whiskey Ring took place from 1871 to 1876 centering in St. Louis during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. The ring was an American scandal, broken in May 1875, involving the diversion of tax revenues in a conspiracy among government agent ...

.

Tweed himself wanted no particular recognition of his achievements, such as they were. When it was proposed, in March 1871, when he was at the height of his power, that a statue be erected in his honor, he declared: "Statues are not erected to living men ... I claim to be a live man, and hope (Divine Providence permitting) to survive in all my vigor, politically and physically, some years to come." One of Tweed's unwanted legacies is that he has become "the archetype of the bloated, rapacious, corrupt city boss".

Middle name

Tweed never signed his middle name with anything other than a plain "M.", and his middle name is often mistakenly listed as "Marcy". His actual middle name was Magear, his mother's maiden name. Confusion derived from a Nast cartoon with a picture of Tweed supplemented with a quote from William L. Marcy, the former governor of New York.In popular culture

* Arthur Train featured Tweed in his 1940 novel of life in Gilded Age New York, ''Tassels On Her Boots''. Tweed is portrayed as having contempt for the people he rules, at one point saying that once he would have been a Baron, with a castle, levying tribute on the people. But now, "'Boss', they call me – and they are glad to have me." * In 1945, Tweed was portrayed byNoah Beery Sr.

Noah Nicholas Beery (January 17, 1882 – April 1, 1946) was an American actor who appeared in films from 1913 until his death in 1946. He was the older brother of Academy Award-winning actor Wallace Beery as well as the father of characte ...

in the Broadway production of ''Up in Central Park'', a musical comedy

Musical theatre is a form of theatre, theatrical performance that combines songs, spoken dialogue, acting and dance. The story and emotional content of a musical – humor, pathos, love, anger – are communicated through words, music, ...

with music by Sigmund Romberg

Sigmund Romberg (July 29, 1887 – November 9, 1951) was a Hungarian-born American composer. He is best known for his Musical theatre, musicals and operettas, particularly ''The Student Prince'' (1924), ''The Desert Song'' (1926) and ''The New Moo ...

. The role was played by Malcolm Lee Beggs for a revival in 1947. In the 1948 film version, Tweed is played by Vincent Price

Vincent Leonard Price Jr. (May 27, 1911 – October 25, 1993) was an American actor. He was known for his work in the horror film genre, mostly portraying villains. He appeared on stage, television, and radio, and in more than 100 films. Price ...

.

* On the 1963–1964 CBS TV series '' The Great Adventure'', which presented one-hour dramatizations of the lives of historical figures, Edward Andrews

Edward Bryan Andrews Jr. (October 9, 1914 – March 8, 1985) was an American stage, film and television actor. Andrews was one of the most recognizable character actors on television and in films from the 1950s through the 1980s. His stark whi ...

portrayed Tweed in the episode "The Man Who Stole New York City", about the campaign by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' to bring down Tweed. The episode aired on December 13, 1963.

* In John Varley's 1977 science-fiction novel, '' The Ophiuchi Hotline'', a crooked politician in a 27th-century human settlement on the Moon assumes the name "Boss Tweed" in emulation of the 19th-century politician, and names his lunar headquarters "Tammany Hall".

* Tweed was played by Philip Bosco in the 1986 TV movie ''Liberty''. According to a review of the film in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', it was Tweed who made the suggestion to call the Statue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty (''Liberty Enlightening the World''; ) is a colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor, within New York City. The copper-clad statue, a gift to the United States from the people of French Thir ...

by that name, instead of its formal name ''Liberty Enlightening the World'', in order to read better in newspaper headlines.

* Andrew O'Hehir of ''The New York Times'' notes that ''Forever'', a 2003 novel by Pete Hamill, and ''Gangs of New York

''Gangs of New York'' is a 2002 American-Italian epic historical drama film directed by Martin Scorsese and written by Jay Cocks, Steven Zaillian, and Kenneth Lonergan, based on Herbert Asbury's 1928 book '' The Gangs of New York''. The fil ...

'', a 2002 film, both "offer a significant supporting role to the legendary Manhattan political godfather Boss Tweed", among other thematic similarities. In a review of the latter work, Chuck Rudolph praised Jim Broadbent

James Broadbent (born 24 May 1949) is an English actor. A graduate of the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art in 1972, he came to prominence as a character actor for his many roles in film and television. He has received various accolades ...

's portrayal of Tweed as "giving the role a masterfully heartless composure".

* Tweed appears as an antagonist in the 2016 novel, ''Assassin's Creed Last Descendants'' where he is the Grand Master of the American Templars during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.

* Tweed appears as an antagonist in the 2016 novel, ''Assassin's Creed Last Descendants'' where he is the Grand Master of the American Templars during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

.Rad, Chloi (February 18, 2016"Assassin's Creed: Last Descendants Novels Announced"

''IGN''.

See also

* Elbert A. Woodward * Timothy "Big Tim" Sullivan * Tweed law * William J. Sharkey (murderer)References

Notes Citations Bibliography * Ackerman, K. D. (2005). ''Boss Tweed: The rise and fall of the corrupt pol who conceived the soul of modern New York''. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. . * * Callow, Alexander B. (1966). ''The Tweed Ring''. New York: Oxford University Press * Ellis, Edward R. (2004). ''The Epic of New York City: A Narrative History''. Carroll & Graf Publishers. , * Hershkowitz, Leo. ''Tweed's New York: Another Look''. (New York: Anchor Press, 1977)online

Encyclopedia.com (

Cengage

Cengage Group is an American educational content, technology, and services company for higher education, K–12, professional, and library markets. It operates in more than 20 countries around the world.(June 27, 2014Global Publishing Leaders 2 ...

), May 23, 2018

* Mandelbaum, Seymour J. (1965). ''Boss Tweed's New York''. New York: John Wiley.

* Paine, Albert B. (1974). ''Th. Nast, His Period and His Pictures''. Princeton: Pyne Press. (The original edition, published in 1904, is now in the public domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work to which no Exclusive exclusive intellectual property rights apply. Those rights may have expired, been forfeited, expressly Waiver, waived, or may be inapplicable. Because no one holds ...

.)

* Sante, Lucy (2003). ''Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York''. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

* Staff (July 4, 2005)"Boss Tweed"

'' Gotham Gazette''

Further reading

* Lynch, Denis Tilden (2005) 927 ''Boss Tweed: The story of a grim generation''. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Michigan Historical Reprint Series, Scholarly Publishing Office, University of Michigan.1927 1st edition

published by

Boni & Liveright

Boni & Liveright (pronounced "BONE-eye" and "LIV-right") is an American trade book publisher established in 1917 in New York City by Albert Boni and Horace Liveright. Over the next sixteen years the firm, which changed its name to Horace Liv ...

External links

Green-Wood Cemetery page for WM Tweed

Map Showing the Portions of the City of New York and Westchester County under the Jurisdiction of the Department of Public Parks

talks about Tweed's takeover of the New York City parks system, from the

World Digital Library

The World Digital Library (WDL) is an international digital library operated by UNESCO and the United States Library of Congress.

The WDL has stated that its mission is to promote international and intercultural understanding, expand the volume ...

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tweed, William M.

1823 births

1878 deaths

American escapees

American people of Scottish descent

American people who died in prison custody

American political bosses from New York (state)

American politicians convicted of fraud

Burials at Green-Wood Cemetery

County legislators in New York (state)

Criminals from New York City

Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state)

Escapees from New York (state) detention

Fugitives

Leaders of Tammany Hall

New York (state) politicians convicted of crimes

Democratic Party New York (state) state senators

Prisoners and detainees of the United States federal government

Prisoners who died in New York (state) detention

American Freemasons

American people convicted of tax crimes

19th-century members of the New York State Legislature

19th-century members of the United States House of Representatives