, strength1 = May 1919: 35,000

November 1920: 86,000

[Turkish General Staff, ''Türk İstiklal Harbinde Batı Cephesi'', Edition II, Part 2, Ankara 1999, p. 225]August 1922: 271,000

[Celâl Erikan, Rıdvan Akın: ''Kurtuluş Savaşı tarihi'', Türkiye İş̧ Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 2008, ]

p. 339

.

, strength2 =

60,000

30,000

20,000

7,000

, casualties1 = 13,000 killed

[Kate Fleet, Suraiya Faroqhi, Reşat Kasaba: ]

The Cambridge History of Turkey Volume 4

'', Cambridge University Press, 2008, , p. 159.22,690 died of disease

[Sabahattin Selek: ''Millî Mücadele – Cilt I (engl.: National Struggle – Edition I)'', Burçak yayınevi, 1963, p. 109. ]5,362 died of wounds or other non-combat causes

35,000 wounded

7,000 prisoners

[Ahmet Özdemir]

''Savaş esirlerinin Milli mücadeledeki yeri''

, Ankara University, Türk İnkılap Tarihi Enstitüsü Atatürk Yolu Dergisi, Edition 2, Number 6, 1990, pp. 328–332Total: 83,052 casualties

, casualties2 = 24,240 killed

[Σειρά Μεγάλες Μάχες: Μικρασιατική Καταστροφή (Νο 8), συλλογική εργασία, έκδοση περιοδικού Στρατιωτική Ιστορία, Εκδόσεις Περισκόπιο, Αθήνα, Νοέμβριος 2002, σελίδα 64 ]18,095 missing

48,880 wounded

4,878 died outside of combat

13,740 prisoners

1,100+ killed

3,000+ prisoners

~7,000

Total: 116,055 casualties

, casualties3 = 264,000

Greek civilians killed60,000–250,000

Armenian civilians killed[These are according to the figures provided by Alexander Miasnikyan, the President of the Council of People's Commissars of Soviet Armenia, in a telegram he sent to the Soviet Foreign Minister Georgy Chicherin in 1921. Miasnikyan's figures were broken down as follows: of the approximately 60,000 Armenians who were killed by the Turkish armies, 30,000 were men, 15,000 women, 5,000 children, and 10,000 young girls. Of the 38,000 who were wounded, 20,000 were men, 10,000 women, 5,000 young girls, and 3,000 children. Instances of mass rape, murder and violence were also reported against the Armenian populace of Kars and Alexandropol: see Vahakn N. Dadrian. (2003). ''The History of the Armenian Genocide: Ethnic Conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus''. New York: Berghahn Books]

pp. 360–361

. .15,000+ Turkish civilians killed in the Western Front

30,000+ buildings and 250+ villages burnt to the ground by the Hellenic Army and Greek/Armenian rebels.

, notes =

, campaignbox =

, casus =

Partitioning of the Ottoman Empire

, commander1 =

Mustafa Kemal Pasha Mustafa Fevzi Pasha Mustafa İsmet Pasha Fahrettin Pasha Ali Fuat Pasha Refet Pasha Nureddin Pasha Ali İhsan Pasha Osman the Lame Ethem the Circassian

, commander2 =

Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Cretan State, Cretan Greeks, Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. As the leader of the Liberal Party (Greece), Liberal Party, Venizelos ser ...

Leonidas Paraskevopoulos Constantine I

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

Dimitrios Gounaris Anastasios Papoulas

Anastasios Papoulas (; 1/13 January 1857 – 24 April 1935) was a Greek general, most notable as the Greek commander-in-chief during most of the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–22. Originally a firm royalist, after 1922 he shifted towards the re ...

Georgios Hatzianestis

Georgios Hatzianestis (, 3 December 1863 – 15 November 1922) was a Greek artillery and general staff officer who rose to the rank of lieutenant general. He is best known as the commander-in-chief of the Army of Asia Minor at the time of th ...

Henri Gouraud Drastamat Kanayan Movses Silikyan

Movses Silikyan or Silikov (, ; 14 September 1862 – 22 November 1937) was an Armenian general who served in the Imperial Russian Army during World War I and later in the army of the First Republic of Armenia. He is regarded as a national hero i ...

Sir George Milne

Mehmed VI

Mehmed VI Vahideddin ( ''Meḥmed-i sâdis'' or ''Vaḥîdü'd-Dîn''; or /; 14 January 1861 – 16 May 1926), also known as ''Şahbaba'' () among the Osmanoğlu family, was the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire and the penultimate Ottoman Cal ...

Damat Ferid Pasha Süleyman Şefik Pasha Anzavur Ahmed Pasha Ethem the Circassian

Alişer

The Turkish War of Independence (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns and a revolution waged by the

Turkish National Movement

The Turkish National Movement (), also known as the Anatolian Movement (), the Nationalist Movement (), and the Kemalists (, ''Kemalciler'' or ''Kemalistler''), included political and military activities of the Turkish revolutionaries that resu ...

, after the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

was occupied and

partitioned following its defeat in

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. The conflict was between the Turkish Nationalists against

Allied and

separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, regional, governmental, or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seekin ...

forces over the application of

Wilsonian principles, especially

self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

, in post-World War I

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

and

eastern Thrace

East Thrace or Eastern Thrace, also known as Turkish Thrace or European Turkey, is the part of Turkey that is geographically in Southeast Europe. Turkish Thrace accounts for 3.03% of Turkey's land area and 15% of its population. The largest c ...

. The revolution concluded the

collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the

Eastern question, ending the

Ottoman sultanate and the

Ottoman caliphate

The Ottoman Caliphate () was the claim of the heads of the Turkish Ottoman dynasty, rulers of the Ottoman Empire, to be the caliphs of Islam during the Late Middle Ages, late medieval and Early Modern period, early modern era.

Ottoman rulers ...

, and establishing the

Republic of Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

. This resulted in the transfer of sovereignty from the sultan-caliph to the

nation

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective Identity (social science), identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, t ...

, setting the stage for

nationalist revolutionary reform in Republican Turkey.

While World War I ended for the Ottomans with the

Armistice of Mudros, the

Allies continued occupying land per the

Sykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from Russia and Italy, to define their mutually agreed spheres of influence and control in an eventual partition of the Ottoman Empire.

T ...

, and to facilitate the

prosecution

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the adversarial system, which is adopted in common law, or inquisitorial system, which is adopted in Civil law (legal system), civil law. The prosecution is the ...

of former members of the

Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

and those involved in the

Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenians, Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily t ...

.

Ottoman commanders therefore refused orders from the Allies and

Ottoman government to disband their forces. In an atmosphere of turmoil,

Sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

Mehmed VI

Mehmed VI Vahideddin ( ''Meḥmed-i sâdis'' or ''Vaḥîdü'd-Dîn''; or /; 14 January 1861 – 16 May 1926), also known as ''Şahbaba'' () among the Osmanoğlu family, was the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire and the penultimate Ottoman Cal ...

dispatched well-respected general

Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk), to restore order; however, he became an enabler and leader of

Turkish Nationalist resistance. In an attempt to establish control over the power vacuum in Anatolia, the Allies agreed to launch a Greek

peacekeeping

Peacekeeping comprises activities, especially military ones, intended to create conditions that favor lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed w ...

force and

occupy Smyrna (

İzmir

İzmir is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara. It is on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, and is the capital of İzmir Province. In 2024, the city of İzmir had ...

), inflaming sectarian tensions and beginning the Turkish War of Independence. A nationalist

counter government led by Mustafa Kemal was established in

Ankara

Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and List of national capitals by area, the largest capital by area in the world. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5,290,822 in its urban center ( ...

when it became clear the Ottoman government was

appeasing the Allies. The Allies pressured the Ottoman "Istanbul government" to suspend the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

,

Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, and sign the

Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres () was a 1920 treaty signed between some of the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire, but not ratified. The treaty would have required the cession of large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, ...

, a treaty unfavorable to Turkish interests that the "

Ankara government" declared illegal.

Turkish and

Syrian forces defeated the

French in the south, and remobilized army units went on to

partition Armenia with the

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

, resulting in the

Treaty of Kars (1921). The Western Front is known as the

Greco-Turkish War.

İsmet Pasha (İnönü)'s organization of militia into a

regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a ...

paid off when Ankara forces fought the Greeks in the

First and

Second Battle of İnönü

The Second Battle of İnönü () was fought between March 23 and April 1, 1921 near İnönü, Eskişehir, İnönü in present-day Eskişehir Province, Turkey during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22), also known as the western front of the larg ...

. The Greeks emerged victorious in the

Battle of Kütahya-Eskişehir and drove on Ankara. The Turks checked their advance in the

Battle of Sakarya and counter-attacked in the

Great Offensive

The Great Offensive () was the largest and final military operation of the Turkish War of Independence, fought between the Turkish Armed Forces loyal to the government of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, and the Kingdom of Greece, ending ...

, which expelled Greek forces. The war ended with the

recapture of İzmir, the

Chanak Crisis and another

armistice in Mudanya.

The Grand National Assembly in Ankara was recognized as the legitimate Turkish government, which signed the

Treaty of Lausanne, a treaty more favorable to Turkey than Sèvres. The Allies evacuated Anatolia and eastern Thrace, the Ottoman government was overthrown, the monarchy abolished, and the

Grand National Assembly of Turkey

The Grand National Assembly of Turkey ( ), usually referred to simply as the GNAT or TBMM, also referred to as , in Turkish, is the Unicameralism, unicameral Turkey, Turkish legislature. It is the sole body given the legislative prerogatives by ...

declared the

Republic of Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

on 29 October 1923. With the war, a

population exchange between Greece and Turkey, the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, and the abolition of the sultanate, the Ottoman era came to an end, and with

Atatürk's reforms

Atatürk's reforms ( or ''Atatürk Devrimleri''), also referred to as the Turkish Revolution (Turkish language, Turkish: ''Türk Devrimi''), were a series of political, legal, religious, cultural, social, and economic policy changes, designed ...

, the Turks created the secular nation of Turkey. Turkey's demographics were significantly impacted by the

Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenians, Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily t ...

and deportations of Greek-speaking, Orthodox Christian

Rum people. The Turkish Nationalist Movement carried out massacres and deportations to eliminate native Christian populations—a continuation of the Armenian genocide and

other ethnic cleansing during World War I.

[*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Levon Marashlian, "Finishing the Genocide: Cleansing Turkey of Armenian Survivors, 1920-1923," in Remembrance and Denial: The Case of the Armenian Genocide, ed. Richard Hovannisian (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1999), pp. 113-45: "Between 1920 and 1923, as Turkish and Western diplomats were negotiating the fate of the Armenian Question at peace conferences in London, Paris, and Lausanne, thousands of Armenians of the Ottoman Empire who had survived the massacres and deportations of World War I continued to face massacres, deportations, and persecutions across the length and breadth of Anatolia. Events on the ground, diplomatic correspondence, and news reports confirmed that it was the policy of the Turkish Nationalists in Angora, who eventually founded the Republic of Turkey, to eradicate the remnants of the empire's Armenian population and finalize the expropriation of their public and private properties."

*

*

*

*

* ] The historic Christian presence in Anatolia was largely destroyed; Muslims went from 80% to 98% of the population.

Background

Following the chaotic politics of the

Second Constitutional Era, the Ottoman Empire came under the control of the

Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

in a

coup in 1913, and then further consolidated its control after the assassination of

Mahmud Shevket Pasha. Founded as a radical revolutionary group seeking to prevent a collapse of the Ottoman Empire, by the eve of World War I it decided that the solution was to implement nationalist and centralizing policies. The CUP reacted to the losses of land and the

expulsion of Muslims from the

Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

by turning even more nationalistic. Part of its effort to consolidate power was to

proscribe

Proscription () is, in current usage, a 'decree of condemnation to death or banishment' (''Oxford English Dictionary'') and can be used in a political context to refer to state-approved murder or banishment. The term originated in Ancient Rome ...

and exile opposition politicians from the

Freedom and Accord Party to remote

Sinop.

The

Unionists brought the Ottoman Empire into

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

on the side of

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, during which a genocidal campaign was waged against Ottoman Christians, namely

Armenians

Armenians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the Armenian highlands of West Asia.Robert Hewsen, Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiq ...

,

Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks (; or ; , , ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group indigenous to the region of Pontus, in northeastern Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). They share a common Pontic Greek culture that is di ...

, and

Assyrians

Assyrians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to Mesopotamia, a geographical region in West Asia. Modern Assyrians share descent directly from the ancient Assyrians, one of the key civilizations of Mesopotamia. While they are distinct from ot ...

. It was based on

an alleged conspiracy that the three groups would rebel on the side of the Allies, so

collective punishment

Collective punishment is a punishment or sanction imposed on a group or whole community for acts allegedly perpetrated by a member or some members of that group or area, which could be an ethnic or political group, or just the family, friends a ...

was applied. A similar suspicion and suppression from the Turkish nationalist government was directed towards the Arab and Kurdish populations, leading to localized rebellions. The

Entente powers reacted to these developments by charging the CUP leaders, commonly known as the

Three Pashas, with "

crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

" and threatened accountability. They also had imperialist ambitions on Ottoman territory, with correspondence over a post-war settlement in the Ottoman Empire being leaked to the press as the

Sykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from Russia and Italy, to define their mutually agreed spheres of influence and control in an eventual partition of the Ottoman Empire.

T ...

. Russia's

exit

Exit(s) may refer to:

Architecture and engineering

* Door

* Portal (architecture), an opening in the walls of a structure

* Emergency exit

* Overwing exit, a type of emergency exit on an airplane

* Exit ramp, a feature of a road interchange

A ...

from World War I and descent into

civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

was driven in part by the Ottoman closure of the

Turkish straits

The Turkish Straits () are two internationally significant waterways in northwestern Turkey. The Straits create a series of international passages that connect the Aegean and Mediterranean seas to the Black Sea. They consist of the Dardanelles ...

to goods bound for

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. A new imperative was given to the Entente powers to knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war and restart the

Eastern Front.

World War I would be the nail in the coffin of

Ottomanism

Ottomanism or ''Osmanlılık'' (, . ) was a concept which developed prior to the 1876–1878 First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. Its proponents believed that it could create the Unity of the Peoples, , needed to keep religion-based ...

, an imperialist and multicultural nationalism. Mistreatment of non-Turk groups after 1913, and the general context of great socio-political upheaval that occurred in the

aftermath of World War I

The aftermath of World War I saw far-reaching and wide-ranging cultural, economic, and social change across Europe, Asia, Africa, and in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were a ...

, meant many minorities now wished to divorce their future from imperialism to form futures of their own by separating into (often

republican)

nation-states. Due to the Turkish nationalist policies pursued by the CUP against Ottoman Christians by 1918 the Ottoman Empire held control over a mostly homogeneous land of Muslims from

eastern Thrace

East Thrace or Eastern Thrace, also known as Turkish Thrace or European Turkey, is the part of Turkey that is geographically in Southeast Europe. Turkish Thrace accounts for 3.03% of Turkey's land area and 15% of its population. The largest c ...

to the Persian border. These included mostly

Turks, as well as

Kurds

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

,

Circassians

The Circassians or Circassian people, also called Cherkess or Adyghe (Adyghe language, Adyghe and ), are a Northwest Caucasian languages, Northwest Caucasian ethnic group and nation who originated in Circassia, a region and former country in t ...

, and

Muhacir groups from

Rumeli. Most

Muslim Arabs were now outside of the Ottoman Empire and under Allied occupation, with some "imperialists" still loyal to the Ottoman Sultanate-Caliphate, and others wishing for independence or Allied protection under a

League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate represented a legal status under international law for specific territories following World War I, involving the transfer of control from one nation to another. These mandates served as legal documents establishing th ...

. Sizable Greek and Armenian minorities remained within its borders, and most of these communities no longer wished to remain under the Empire.

Conclusion of World War I

In the summer months of 1918, the leaders of the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

realized that the

Great War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

was lost, including the Ottomans'. Almost simultaneously the

Palestinian Front and then the

Macedonian Front collapsed. The sudden decision by

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

to sign an

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

cut communications from Constantinople (

İstanbul) to

Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

and

Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, and opened the undefended Ottoman capital to Entente attack. With the major fronts crumbling, Unionist

Grand Vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

Talât Pasha intended to sign an armistice, and resigned on 8 October 1918 so that a new government would receive less harsh armistice terms. The

Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October 1918, ending World War I for the Ottoman Empire. Three days later, the

Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

(CUP)—which governed the Ottoman Empire as a one-party state since

1913

Events January

* January – Joseph Stalin travels to Vienna to research his ''Marxism and the National Question''. This means that, during this month, Stalin, Hitler, Trotsky and Tito are all living in the city.

* January 3 &ndash ...

—held its last congress, where it was decided the party would be dissolved. Talât,

Enver Pasha

İsmâil Enver (; ; 23 November 1881 – 4 August 1922), better known as Enver Pasha, was an Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Turkish people, Turkish military officer, revolutionary, and Istanbul trials of 1919–1920, convicted war criminal who was a p ...

,

Cemal Pasha

Ahmed Djemal (; ; 6 May 1872 – 21 July 1922), also known as Djemal Pasha or Cemâl Pasha, was an Ottoman military leader and one of the Three Pashas that ruled the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

As an officer of the II Corps, he was ...

,

Doctor Nâzım,

Bahaeddin Şakir, and three other high-ranking members of the CUP escaped the Ottoman Empire on a German torpedo boat later that night, plunging the country into a power vacuum.

With the fall of the CUP: the following factions hoped to take advantage of the power vacuum in the Ottoman Empire:

* The Palace: With Sultan

Mehmed V

Mehmed V Reşâd (; or ; 2 November 1844 – 3 July 1918) was the penultimate List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1909 to 1918. Mehmed V reigned as a Constitutional monarchy, constitutional monarch. He had ...

's death earlier in the summer of 1918,

Mehmed VI

Mehmed VI Vahideddin ( ''Meḥmed-i sâdis'' or ''Vaḥîdü'd-Dîn''; or /; 14 January 1861 – 16 May 1926), also known as ''Şahbaba'' () among the Osmanoğlu family, was the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire and the penultimate Ottoman Cal ...

was girded with the

sword of Osman. Unlike his half-brother, the new Sultan wished to reassert the monarchy as a center of power in the Ottoman Empire. In the following conflict, his singular goal was to safe guard the interests of the

royal family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term papal family describes the family of a pope, while th ...

.

* The Liberals: The

Freedom and Accord Party would be reestablished, and attempt to salvage the Ottoman Empire's diplomatic position by cooperating with Allied demands, though their detractors accused them of appeasement. Like its first period of operation from 1911–1913, Freedom and Accord Party again fell into infigting, and would be defunct by the summer of 1919. One of its old leaders,

Damat Ferid Pasha, would form a strong alliance with the Sultan, though he did not rejoin his party.

* The

Allies:

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

and

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

had several goals. Both countries hoped to carve up the Ottoman Empire with mandates and spheres of influence. Britain specifically focused on facilitating war crimes trials to try Ottoman war criminals. Their immediate short term goal was to secure supply lines to assist the

Whites

White is a racial classification of people generally used for those of predominantly European ancestry. It is also a skin color specifier, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, ethnicity and point of view.

De ...

in the

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

. Right after the armistice a ''de facto''

Allied occupation began in Constantinople. Some Ottoman intelligentsia hoped the Empire could become a mandate under the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, an upstart and trustworthy power that recently proclaimed the

Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

.

* Ethnic minorities:

Ottoman Greeks hoped to join

Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

and

Armenians

Armenians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the Armenian highlands of West Asia.Robert Hewsen, Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiq ...

hoped join the new

Armenian Republic.

Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks (; or ; , , ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group indigenous to the region of Pontus, in northeastern Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). They share a common Pontic Greek culture that is di ...

hoped to establish their own state. In April 1919 they renounced their allegiance to the Ottoman state through their patriarchs. Some

Kurds

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

hoped to establish an autonomous Kurdish state, but their claims overlapped with

Assyrian nationalists.

* Unionists: Though their leaders had escaped the country and the CUP as a whole was discredited and dissolved as an organization, ex-Unionists still controlled

parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, the

army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

, police, post and telegraph, bureaucracy, and more. They were the target of purges which started by 1919, but the Allies and the Liberals did not have the resources or manpower to go after all of them. They would eventually coalesce around

Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk).

Prelude: October 1918 – May 1919

Armistice of Mudros and occupation

On 30 October 1918, the

Armistice of Mudros was signed between the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

and the

Allies of World War I

The Allies or the Entente (, ) was an international military coalition of countries led by the French Republic, the United Kingdom, the Russian Empire, the United States, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Empire of Japan against the Central Powers ...

, bringing hostilities in the

Middle Eastern theatre of World War I

The Middle Eastern theatre of World War I saw action between 30 October 1914 and 30 October 1918. The combatants were, on one side, the Ottoman Empire, with some assistance from the other Central Powers; and on the other side, the British Em ...

to an end. The Ottoman Army was to demobilize, its

navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

and

air force

An air force in the broadest sense is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an army aviati ...

handed to the Allies, and occupied territory in the

Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

and

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

to be evacuated. Critically, Article VII granted the Allies the right to occupy forts controlling the

Turkish Straits

The Turkish Straits () are two internationally significant waterways in northwestern Turkey. The Straits create a series of international passages that connect the Aegean and Mediterranean seas to the Black Sea. They consist of the Dardanelles ...

and the vague right to occupy "in case of disorder" any territory if there were a threat to security. The clause relating to the occupation of the straits was meant to secure a

Southern Russian intervention force, while the rest of the article was used to allow for Allied controlled

peace-keeping forces. There was also a hope to follow through punishing local actors that carried out exterminatory orders from the CUP government against

Armenian Ottomans. For now, the

House of Osman escaped the fates of the

Hohenzollerns,

Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

, and

Romanovs to continue ruling their empire, though at the cost of its remaining sovereignty.

The armistice was signed because the Ottoman Empire had been defeated in important fronts, but the military was intact and retreated in good order. Unlike other Central Powers, the Allies did not mandate an abdication of the

imperial family

A royal family is the immediate family of monarch, monarchs and sometimes their extended family.

The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or emperor, empress, and the term papal family describes the family of ...

as a condition for peace, nor did they request the

Ottoman Army

The Military of the Ottoman Empire () was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire. It was founded in 1299 and dissolved in 1922.

Army

The Military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the years ...

to dissolve its

general staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, Enlisted rank, enlisted, and civilian staff who serve the commanding officer, commander of a ...

. Though the army suffered from mass

desertion

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ...

throughout the war which led to

banditry

Banditry is a type of organized crime committed by outlaws typically involving the threat or use of violence. A person who engages in banditry is known as a bandit and primarily commits crimes such as extortion, robbery, kidnapping, and murder, ...

, there was no threat of mutiny or revolutions like in

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

,

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, or

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. This is despite famine and economic collapse that was brought on by the extreme levels of

mobilization

Mobilization (alternatively spelled as mobilisation) is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the ...

, destruction from the war,

disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

, and mass murder since 1914.

On 13 November 1918, a French brigade entered Constantinople to begin a ''de facto''

occupation of the Ottoman capital and its immediate dependencies. This was followed by a fleet consisting of British, French, Italian and Greek ships deploying soldiers on the ground the next day, totaling 50,000 troops in Constantinople.

[Jowett, S. Philip, Kurtuluş Savaşı'nda Ordular 1919-22, çev. Emir Yener, Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 2015.] The Allied Powers stated that the occupation was temporary and its purpose was to protect the

monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

, the

caliphate

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

and the

minorities

The term "minority group" has different meanings, depending on the context. According to common usage, it can be defined simply as a group in society with the least number of individuals, or less than half of a population. Usually a minority g ...

.

Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe—the British signatory of the Mudros Armistice—stated the

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

's public position that they had no intention to dismantle the Ottoman government or place it under military occupation by "occupying Constantinople". However, dismantling the government and partitioning the Ottoman Empire among the Allied nations had been an objective of the Entente since the start of WWI.

A wave of seizures took place in the rest of the country in the following months. Questionably citing Article VII, the British occupied Mosul, claiming that Christian civilians in Mosul and

Zakho were killed en masse by the Turkish troops. In the Caucasus, Britain established a presence in

Menshevik Georgia and the

Lori and

Aras valleys as

peace-keepers. On 14 November, joint Franco-Greek occupation was established in the town of

Uzunköprü in eastern Thrace as well as the railway axis until the train station of

Hadımköy on the outskirts of Constantinople. On 1 December, British troops based in Syria occupied

Kilis,

Marash,

Urfa and

Birecik. Beginning in December, French troops began successive seizures of the

province of Adana, including the towns of

Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

,

Mersin

Mersin () is a large city and port on the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast of Mediterranean Region, Turkey, southern Turkey. It is the provincial capital of the Mersin Province (formerly İçel). It is made up of four district governorates ...

,

Tarsus,

Ceyhan,

Adana

Adana is a large city in southern Turkey. The city is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the northeastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea. It is the administrative seat of the Adana Province, Adana province, and has a population of 1 81 ...

,

Osmaniye, and

İslâhiye, incorporating the area into the

Occupied Enemy Territory Administration North while French forces embarked by

gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s and sent troops to the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

ports of

Zonguldak

Zonguldak () is a List of cities in Turkey, city of about 100 thousand people in the Black Sea region of Turkey. It is the seat of Zonguldak Province and Zonguldak District.[Karadeniz Ereğli

Karadeniz Ereğli (or Ereğli) is a city in Zonguldak Province of Turkey on the Black Sea shore. It is the seat of Ereğli District.] commanding Turkey's coal mining region. These continued seizures of land prompted Ottoman commanders to refuse demobilization and prepare for the resumption of war.

Prelude to resistance

The British similarly asked

Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk) to turn over the port of Alexandretta (

İskenderun

İskenderun (), historically known as Alexandretta (, ) and Scanderoon, is a municipality and Districts of Turkey, district of Hatay Province, Turkey. Its area is 247 km2, and its population is 251,682 (2022). It is on the Mediterranean coas ...

), which he reluctantly did, following which he was recalled to Constantinople. He made sure to distribute weapons to the population to prevent them from falling into the hands of Allied forces. Some of these weapons were smuggled to the east by members of

Karakol, a successor to the CUP's

Special Organization, to be used in case resistance was necessary in Anatolia. Many Ottoman officials participated in efforts to conceal from the occupying authorities details of the burgeoning independence movement spreading throughout Anatolia.

Other commanders began refusing orders from the Ottoman government and the Allied powers. After Mustafa Kemal Pasha returned to Constantinople,

Ali Fuat Pasha (Cebesoy) brought

XX Corps under his command. He marched first to

Konya

Konya is a major city in central Turkey, on the southwestern edge of the Central Anatolian Plateau, and is the capital of Konya Province. During antiquity and into Seljuk times it was known as Iconium. In 19th-century accounts of the city in En ...

and then to

Ankara

Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and List of national capitals by area, the largest capital by area in the world. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5,290,822 in its urban center ( ...

to organise resistance groups, such as the Circassians, Circassian çetes he assembled with guerilla leader Çerkes Ethem. Meanwhile, Kâzım Karabekir, Kâzım Karabekir Pasha refused to surrender his intact and powerful XV Corps (Ottoman Empire), XV Corps in Erzurum. Evacuating from the Caucusus, puppet republics and Muslim uprisings in Kars and Sharur–Nakhichevan, Muslim militia groups were established in the army's wake to hamper the consolidation of the new First Republic of Armenia, Armenian state. Elsewhere in the country, regional nationalist resistance organizations known as ''Şûrâs'' –meaning "councils", not unlike ''Soviet (council), soviets'' in revolutionary Russia– were founded, most incorporating themselves into the Association for Defence of National Rights, Defence of National Rights movement which protested continued Allied occupation and appeasement by the Sublime Porte.

The Armistice era

Politics of de-Ittihadification

Following the occupation of Constantinople, Mehmed VI, Mehmed VI Vahdettin dissolved the Chamber of Deputies (Ottoman Empire), Chamber of Deputies which was dominated by Unionists 1914 Ottoman general election, elected back in 1914, promising elections for the next year. Vahdettin just ascended to the throne only months earlier with the death of Mehmed V Reşad, Mehmed V Reşâd. He was disgusted with the policies of the CUP, and wished to be a more assertive sovereign than his diseased half brother. Ottoman Greeks, Greek and

Armenian Ottomans declared the termination of their relationship with the Ottoman Empire through their respective patriarchates, and refused to partake in any future election. With the collapse of the CUP and its censorship regime, an outpouring of condemnation against the party came from all parts of Media of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman media.

A general amnesty was soon issued, allowing the exiled and imprisoned dissidents persecuted by the CUP to return to Constantinople. Sultan Vahdettin invited the pro-Ottoman dynasty, Palace politician

Damat Ferid Pasha to form a government, whose members quickly set out to purge the

Unionists from the

Ottoman government. Ferid Pasha hoped that his Anglophile, Anglophilia and an attitude of appeasement would induce less harsh peace terms from the Allied powers. However, his appointment was problematic for the Unionists, many being members of the liquidated committee that were surely to face trial. Years of corruption, unconstitutional acts, war profiteering, and enrichment from ethnic cleansing and Armenian genocide, genocide by the Unionists soon became basis of Prosecution of Ottoman war criminals, war crimes trials and Istanbul trials of 1919–1920, courts martial trials held in Constantinople. While many leading Unionists were sentenced lengthy prison sentences, many made sure to escape the country before Allied occupation or to regions that the government now had minimal control over; thus most were sentenced ''Trial in absentia, in absentia''. The Allies encouragement of the proceedings and the use of British Malta exiles, Malta as their holding ground made the trials unpopular. The partisan nature of the trials was not lost on observers either. The hanging of the Kaymakam of Boğazlıyan district Mehmet Kemal, Mehmed Kemal resulted in a demonstration against the courts martials trials.

With all the chaotic politics in the capital and uncertainty of the severity of the incoming peace treaty, many Ottomans looked to Washington with the hope that the application of

Wilsonian principles would mean Constantinople would stay Turkish, as Muslims outnumbered Christians 2:1. The

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

never declared war on the Ottoman Empire, so many imperial elite believed Washington could be a neutral arbiter that could fix the empire's problems. Halide Edib Adıvar, Halide Edip (Adıvar) and her :tr:Wilson Prensipleri Cemiyeti, Wilsonian Principles Society led the movement that advocated for the empire to be governed by an American League of Nations mandate, League of Nations Mandate (see United States during the Turkish War of Independence). American diplomats attempted to ascertain a role they could play in the area with the Harbord Commission, Harbord and King–Crane Commission, King–Crane Commissions. However, with the collapse of Woodrow Wilson's health, the United States diplomatically withdrew from the Middle East to focus on Europe, leaving the Entente powers to construct a post-Ottoman International order, order.

Banditry and the refugee crisis

The Entente would have arrived at Constantinople to discover an administration attempting to deal with decades of accumulated refugee crisis. The new government issued a proclamation allowing for deportees to Right of return, return to their homes, but many Greeks and Armenians found their old homes occupied by desperate Muhacir, Rumelian and Caucasian Muslim refugees which were settled in their properties during the First World War. Ethnic conflict restarted in Anatolia; government officials responsible for resettling Christian refugees often assisted Muslim refugees in these disputes, prompting European powers to continue bringing Ottoman territory under their control. Of the 800,000 Ottoman Christian refugees, approximately over half returned to their homes by 1920. Meanwhile 1.4 million refugees from the

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

would pass through the Turkish straits and Anatolia, with 150,000 White émigré, White émigrés choosing to settle in Istanbul for short or long term (see Evacuation of the Crimea). Many provinces were simply depopulated from years of fighting, conscription, and ethnic cleansing (see Ottoman casualties of World War I). The province of Yozgat lost 50% of its Muslim population from conscription, while according to the governor of Van, Turkey, Van, almost 95% of its prewar residents were dead or Internally displaced person, internally displaced.

Administration in much of the Anatolian and Thracian countryside would soon all but collapse by 1919. Army deserters who turned to

banditry

Banditry is a type of organized crime committed by outlaws typically involving the threat or use of violence. A person who engages in banditry is known as a bandit and primarily commits crimes such as extortion, robbery, kidnapping, and murder, ...

essentially controlled fiefdoms with tacit approval from bureaucrats and local elites. An amnesty issued in late 1918 saw these bandits strengthen their positions and fight amongst each other instead of returning to civilian life. Albanians in Turkey, Albanian and Circassians in Turkey, Circassian Muhacir, muhacirs resettled by the government in northwestern Anatolia and Kurds in Turkey, Kurds in southeastern Anatolia were engaged in blood feuds that intensified during the war and were hesitant to pledge allegiance to the Defence of Rights movement, and only would if officials could facilitate truces. Various Muhacir groups were suspicious of the continued İttihadism, Unionist ideology in the Defence of Rights movement, and the potential for themselves to meet fates 'like the Armenians' especially as warlords hailing from those communities assisted the deportations of the Christians even though as many commanders in the Nationalist movement also had Caucasian and Balkan Muslim ancestry.

Mustafa Kemal's mission

With Anatolia in practical anarchy and the Ottoman army being questionably loyal in reaction to Allied land seizures, Mehmed VI established the military inspectorate system to reestablish authority over the remaining empire. Encouraged by Karabekir and Edmund Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, Edmund Allenby, he assigned

as the inspector of the Ninth Army (Ottoman Empire)#After Mudros, Ninth Army Troops Inspectorate –based in Erzurum– to restore order to Ottoman military units and to improve internal security on 30 April 1919, with his first assignment to suppress a rebellion by Greek rebels around the city of Samsun.

Mustafa Kemal was a well known, well respected, and well connected army commander, with much prestige coming from his status as the "Hero of Battle of Anfartalar, Anafartalar"—for his role in the Gallipoli Campaign—and his title of "Honorary Aide-de-camp to His Majesty Sultan" gained in the last months of WWI. This choice would seem curious, as he was a nationalist and a fierce critic of the government's accommodating policy to the Entente powers. He was also an early member of the CUP. However Kemal Pasha did not associate himself with the fanatical faction of the CUP, many knew that he frequently clashed with the radicals of the Central Committee of the Committee of Union and Progress, Central Committee like Enver. He was therefore sidelined to the periphery of power throughout the Great War; after the CUP's dissolution he vocally aligned himself with moderates that formed the Ottoman Liberal People's Party, Liberal People's Party instead of the rump Renewal Party (Ottoman Empire), Renewal Party (both parties would be banned in May 1919 for being successors of the CUP). All these reasons allowed him to be the most legitimate nationalist for the sultan to placate. In this new political climate, Kemal, his friends, and soon to be sympathizers benefited from the purges, elevating to ever higher profile positions. He sought to capitalize on his war exploits to attain a better job, indeed several times he unsuccessfully lobbied for his inclusion in cabinet as Ministry of War (Ottoman Empire), War Minister. His new assignment gave him effective plenipotentiary powers over all of Anatolia which was meant to accommodate him and other nationalists to keep them loyal to the government.

Mustafa Kemal had earlier declined to become the leader of the Sixth Army (Ottoman Empire), Sixth Army headquartered in Nusaybin. But according to Patrick Balfour, 3rd Baron Kinross, Lord Kinross, through manipulation and the help of friends and sympathizers, he became the inspector of virtually all of the Ottoman forces in Anatolia, tasked with overseeing the disbanding process of remaining Ottoman forces while at the same time suppressing a Greek uprising nearby Samsun. Kemal had an abundance of connections and personal friends concentrated in the post-armistice War Ministry, a powerful tool that would help him accomplish his secret goal: to lead a nationalist movement to safeguard Turkish interests against the Allied powers and a collaborative Ottoman government.

The day before his departure to Samsun on the remote Black Sea coast, Kemal had one last audience with Sultan Vahdettin, where he affirmed his loyalty to the sultan-caliph. It was in this meeting that they were informed of the botched Greek landing at Smyrna, occupation ceremony of Smyrna (İzmir) by the Greeks. He and his carefully selected staff left Constantinople aboard the old steamer on the evening of 16 May 1919.

Negotiations for Ottoman partition

On 19 January 1919, the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, Paris Peace Conference was first held, at which Allied nations set the peace terms for the defeated

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

, including the Ottoman Empire. As a special body of the Paris Conference, "The Inter-Allied Commission on Mandates in Turkey", was established to pursue the secret treaties they had signed between 1915 and 1917. Italy sought control over the southern part of Anatolia under the Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne. France expected to exercise control over Hatay Province, Hatay, Lebanon, Syria (region), Syria, and a portion of southeastern Anatolia based on the

Sykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from Russia and Italy, to define their mutually agreed spheres of influence and control in an eventual partition of the Ottoman Empire.

T ...

.

Greece justified their territorial claims of Ottoman land not least from Greece's entrance to WWI on the Allied side but also through the Megali Idea as well as international sympathy from the suffering of

Ottoman Greeks in 1914 Greek deportations, 1914 and Pontic genocide, 1917–1918. Privately, Greek prime minister

Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Cretan State, Cretan Greeks, Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. As the leader of the Liberal Party (Greece), Liberal Party, Venizelos ser ...

had British prime minister David Lloyd George's backing because of his Philhellenism, and from his charisma and charming personality. Greece's participation in the Allies' Southern Russia intervention, Southern Russian intervention also earned it favors in Paris. Venizelos' demands included parts of eastern Thrace, the islands of Imbros (Gökçeada), Tenedos (Bozcaada), and parts of Western Anatolia around the city of Smyrna (

İzmir

İzmir is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara. It is on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, and is the capital of İzmir Province. In 2024, the city of İzmir had ...

), all of which had large Greek populations. Venizelos also advocated a large Armenian state to check a post-war Ottoman Empire. Greece wanted to incorporate Constantinople, but Entente powers did not give permission. Damat Ferid Pasha went to Paris on behalf of the Ottoman Empire hoping to minimize territorial losses using

Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

rhetoric, wishing for a return to ''status quo ante bellum'', on the basis that every province of the Empire holds Muslim majorities. This plea was met with ridicule.

At the Paris Peace Conference, competing claims over Anatolia, Western Anatolia by Greek and Italian delegations led Greece to land the flagship of the Greek Navy at Smyrna, resulting in the Italian delegation walking out of the peace talks. On 30 April, Italy responded to the possible idea of Greek incorporation of Western Anatolia by sending a warship to Smyrna as a show of force against the Greek campaign. A large Italian force Italian occupation of Adalia, also landed in Antalya. Faced with Italian annexation of parts of Asia Minor with a significant ethnic Greek population, Venizelos secured Allied permission for Greek troops to land in Smyrna per Article VII, ostensibly as a

peacekeeping

Peacekeeping comprises activities, especially military ones, intended to create conditions that favor lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed w ...

force to keep stability in the region. Venizelos's rhetoric was more directed against the CUP regime than the Turks as a whole, an attitude not always shared in the Greek military: "Greece is not making war against Islam, but against the anachronistic [

İttihadism, Unionist] Government, and its corrupt, ignominious, and bloody administration, with a view to the expelling it from those territories where the majority of the population consists of Greeks." It was decided by the Triple Entente that Greece would control a zone around Smyrna and Ayvalık in western Asia Minor.

Organizational phase: May 1919 – March 1920

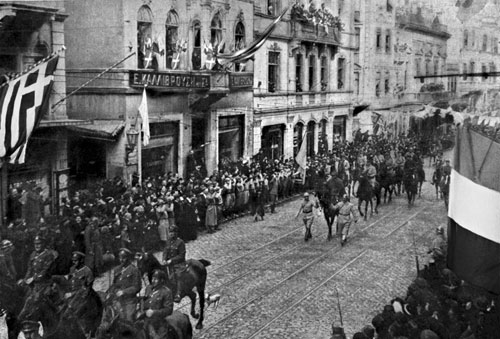

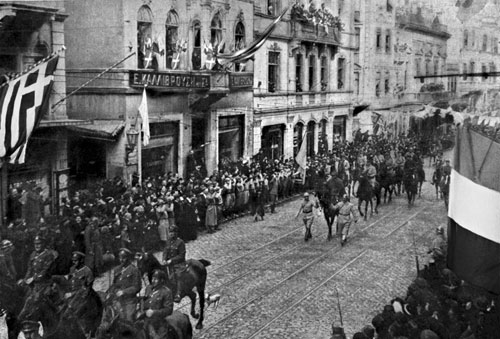

Greek landing at Smyrna

Most historians mark the Greek landing at Smyrna on 15 May 1919 as the start date of the Turkish War of Independence as well as the start of the "Kuva-yi Milliye Phase". The occupation ceremony from the outset was tense from nationalist fervor, with Ottoman Greeks greeting the soldiers with an ecstatic welcome, and Ottoman Muslims protesting the landing. A miscommunication in Greek high command led to an Evzones, Evzone column marching by the municipal Turkish barracks. The nationalist journalist Hasan Tahsin fired the "first bullet"

[Mehmet Çavuş's fire against the French in Dörtyol was misknown until near past. But Hasan Tahsin's firing was the first bullet in Western Front.] at the Greek standard bearer at the head of the troops, turning the city into a warzone. :tr:Süleyman Fethi Bey, Süleyman Fethi Bey was murdered by bayonet for refusing to shout "Zito Eleftherios Venizelos, Venizelos" (meaning "long live Venizelos"), and 300–400 unarmed Turkish soldiers and civilians and 100 Greek soldiers and civilians were killed or wounded.

Greek troops moved from Smyrna outwards to towns on the Karaburun Peninsula, Turkey, Karaburun peninsula; to Selçuk, situated a hundred kilometres south of the city at a key location that commands the fertile Küçük Menderes River valley; and to Menemen towards the north. Guerrilla warfare, Guerilla warfare commenced in the countryside, as Turks began to organize themselves into irregular guerilla groups known as Kuva-yi Milliye (national forces), which were soon joined by Ottoman soldiers, bandits, and disaffected farmers. Most Kuva-yi Milliye bands were led by rogue military commanders and members of the

Special Organization. The Greek troops based in cosmopolitan Smyrna soon found themselves conducting counterinsurgency operations in a hostile, dominantly Muslim hinterland. Groups of Ottoman Greeks also formed contingents that cooperated with the Army of Asia Minor, Greek Army to combat Kuva-yi Milliye within the zone of control. A Menemen massacre, massacre of Turks at Menemen was followed up with a Battle of Aydın, battle for the town of Aydın, which saw intense intercommunal violence and the razing of the city. What was supposed to be a peacekeeping mission of Western Anatolia instead inflamed ethnic tensions and became a counterinsurgency.

The reaction of Greek landing at Smyrna and continued Allied seizures of land served to destabilize Turkish civil society. Damat Ferid Pasha resigned as Grand Vizier, but the sultan reappointed him anyways. With the Chamber of Deputies dissolved, and the environment not looking conducive for an election, Sultan Mehmed VI called for a Sultanate Council (''Şûrâ-yı Saltanat''), so the government could be consulted by representatives of civil society how the Ottoman Empire should deal with its present predicaments. On 26 May 1919, 131 representatives of Ottoman civil society gathered in the capital as a faux parliament. Discussion focused on a new election for the Chamber of Deputies or to become a British or American mandate. By and large, the assembly was unsuccessful in its goals, and the Ottoman government did not develop a strategy to navigate the crises the empire was engulfed in.

Ottoman bureaucrats, military, and bourgeoisie trusted the Allies to bring peace, and thought the terms offered at Mudros were considerably more lenient than they actually were.

Pushback was potent in the capital, with 23 May 1919 being largest of the Sultanahmet demonstrations, Sultanahmet Square demonstrations organized by the Turkish Hearths against the Greek occupation of Smyrna, the largest act of civil disobedience in Turkish history at that point. The Ottoman government condemned the landing, but could do little about it.

Organizing resistance

Mustafa Kemal Pasha and his colleagues stepped ashore in Samsun on 19 May

and set up their first quarters in the Mıntıka Palace Hotel. British troops were present in Samsun, and he initially maintained cordial contact. He had assured Damat Ferid about the army's loyalty towards the new government in Constantinople. However, behind the government's back, Kemal made the people of Samsun aware of the Greek and Italian landings, staged discreet mass meetings, made fast connections via telegraph with the army units in Anatolia, and began to form links with various Nationalist groups. He sent telegrams of protest to foreign embassies and the War Ministry about British reinforcements in the area and about British aid to Greek brigand gangs. After a week in Samsun, Kemal and his staff moved to Havza. It was there that he first showed the flag of the resistance.

[Jäschke, Gotthard (1975), p.188]

Mustafa Kemal wrote in his memoir that he needed nationwide support to justify armed resistance against the Allied occupation. His credentials and the importance of his position were not enough to inspire everyone. While officially occupied with the disarming of the army, he met with various contacts in order to build his movement's momentum. He met with Hüseyin Rauf Orbay, Rauf Pasha, Karabekir Pasha,

Ali Fuat Pasha, and

Refet Pasha and issued the Amasya Circular (22 June 1919). Ottoman provincial authorities were notified via telegraph that the unity and independence of the nation was at risk, and that the government in Constantinople was compromised. To remedy this, a congress was to take place in Erzurum between delegates of the Six vilayets, Six Vilayets to decide on a response, and another congress would take place in Sivas where every Vilayet should send delegates. Sympathy and a lack of coordination from the capital gave Mustafa Kemal freedom of movement and telegraph use despite his implied anti-government tone.

On 23 June, High Commissioner Admiral Calthorpe, realising the significance of Mustafa Kemal's discreet activities in Anatolia, sent a report about the Pasha to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Foreign Office. His remarks were downplayed by George Kidson of the Eastern Department. Captain Hurst of the British occupation force in Samsun warned Admiral Calthorpe one more time, but Hurst's units were replaced with the Brigade of Gurkhas. When the British landed in Alexandretta, Admiral Calthorpe resigned on the basis that this was against the armistice that he had signed and was assigned to another position on 5 August 1919. The movement of British units alarmed the population of the region and convinced them that Mustafa Kemal was right.

Consolidation through congresses

By early July, Mustafa Kemal Pasha received telegrams from the sultan and Calthorpe, asking him and Refet to cease his activities in Anatolia and return to the capital. Kemal was in Erzincan and did not want to return to Constantinople, concerned that the foreign authorities might have designs for him beyond the sultan's plans. Before resigning from his position, he dispatched a circular to all nationalist organizations and military commanders to not disband or surrender unless for the latter if they could be replaced by cooperative nationalist commanders. Now only a civilian stripped of his command, Mustafa Kemal was at the mercy of the new inspector of Third Army (Ottoman Empire), Third Army (renamed from Ninth Army) Karabekir Pasha, indeed the War Ministry ordered him to arrest Kemal, an order which Karabekir refused.

The Erzurum Congress was a meeting of delegates and governors from the six Eastern Vilayets. They drafted the Misak-ı Millî, National Pact (''Misak-ı Millî)'', which envisioned new borders for the Ottoman Empire by applying principles of Self-determination, national self-determination per Woodrow Wilson's

Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

and the abolition of Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, the capitulations. The Erzurum Congress concluded with a circular that was effectively a declaration of independence: All regions within Ottoman borders upon the signing of the Mudros Armistice were indivisible from the Ottoman state –Greek and Armenian claims on Thrace and Anatolia were moot– and assistance from any country not coveting Ottoman territory was welcome. If the government in Constantinople was not able to attain this after electing a new parliament, they insisted a provisional government should be promulgated to defend Turkish sovereignty. The Committee of Representation was established as a provisional executive body based in Anatolia, with Mustafa Kemal Pasha as its chairman.

Following the congress, the Committee of Representation relocated to Sivas. As announced in the Amasya Circular, a new congress was held there in September with delegates from all Anatolian and Thracian provinces. The Sivas Congress repeated the points of the National Pact agreed to in Erzurum, and united the various regional Association for Defence of National Rights, Defence of National Rights Associations organizations, into a united political organisation: Association for Defence of National Rights, Anatolia and Rumeli Defence of Rights Association (A-RMHC), with Mustafa Kemal as its chairman. In an effort show his movement was in fact a new and unifying movement, the delegates had to swear an oath to discontinue their relations with the CUP and to never revive the party (despite most present in Sivas being previous members). It was also decided there that the Ottoman Empire should not be a League of Nations mandate under the United States, especially after the United States Senate, U.S Senate failed to ratify American membership in the League.

Momentum was now on the Nationalists' side. A :tr:Ali Galip Olayı, plot by a :tr:Ali_Galip_(Elazığ_valisi), loyalist Ottoman governor and a Edward Noel (Indian Army officer), British intelligence officer to arrest Kemal before the Sivas Congress led to the cutting of all ties with the Ottoman government until a new election would be held in the lower house of parliament, the Chamber of Deputies (Ottoman Empire), Chamber of Deputies. In October 1919, the last Ottoman governor loyal to Constantinople fled his province. Fearing the outbreak of hostilities, all British troops stationed in the Black Sea coast and Kütahya were evacuated. Damat Ferid Pasha resigned, and the sultan replaced him with a general with nationalist credentials: Ali Rıza Pasha. On 16 October 1919, Ali Rıza and the Nationalists held negotiations in Amasya. They agreed in the Amasya Protocol that an election would be called for the Ottoman Parliament to establish national unity by upholding the resolutions made in the Sivas Congress, including the National Pact.

By October 1919, the Ottoman government only held ''de facto'' control over Constantinople; the rest of the Ottoman Empire was loyal to Kemal's movement to resist a partition of Anatolia and Thrace. Within a few months Mustafa Kemal went from General Inspector of the Ninth Army to a renegade military commander discharged for insubordination to leading a homegrown anti-Entente movement that overthrew a government and driven it into resistance.

Last Ottoman parliament

In December 1919, an 1919 Ottoman general election, election was held for the Ottoman parliament, with polls only open in unoccupied Anatolia and Thrace. It was boycotted by Ottoman Greeks, Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Armenians and the

Freedom and Accord Party, resulting in groups associated with the Turkish National Movement, Turkish Nationalist Movement winning, including the A-RMHC. The Nationalists' obvious links to the CUP made the election especially polarizing and voter intimidation and ballot box stuffing in favor of the Kemalists were regular occurrences in rural provinces. This controversy led to many of the nationalist MPs organizing the :tr:Felâh-ı_Vatan, National Salvation Group separate from Kemal's movement, which risked the nationalist movement splitting in two.

Mustafa Kemal was elected an MP from Erzurum, but he expected the Allies neither to accept the Harbord Commission, Harbord report nor to respect his parliamentary immunity if he went to the Ottoman capital, hence he remained in Anatolia. Mustafa Kemal and the Committee of Representation moved from Sivas to

Ankara