Trimountaine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The written history of

The written history of

In 1684, fearing that the rumored revocation of the

In 1684, fearing that the rumored revocation of the

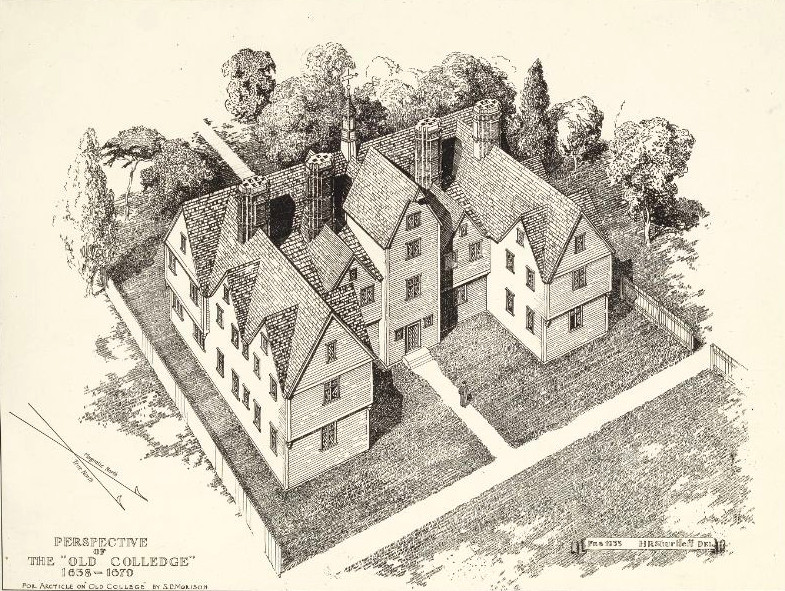

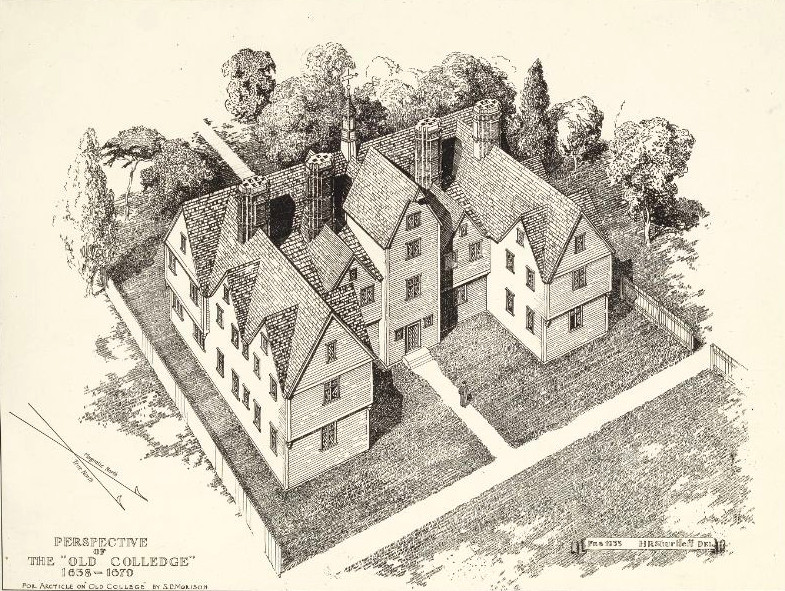

Early colonists believed that Boston was a community with a special covenant with God, as captured in Winthrop's " City upon a Hill" metaphor. This influenced every facet of Boston life, and made it imperative that colonists legislate morality as well as enforce marriage, church attendance, education in the Word of God, and the persecution of sinners. One of the first schools in America,

Early colonists believed that Boston was a community with a special covenant with God, as captured in Winthrop's " City upon a Hill" metaphor. This influenced every facet of Boston life, and made it imperative that colonists legislate morality as well as enforce marriage, church attendance, education in the Word of God, and the persecution of sinners. One of the first schools in America,  Town officials in colonial Boston were chosen annually; positions included

Town officials in colonial Boston were chosen annually; positions included  From 1686 until 1689, Massachusetts and surrounding colonies were united. This larger province, known as the

From 1686 until 1689, Massachusetts and surrounding colonies were united. This larger province, known as the

By the late 1760s, Patriot colonists focused on the

By the late 1760s, Patriot colonists focused on the

In 1831,

In 1831,

As the population increased rapidly,

As the population increased rapidly,

File:Boston-view-1841-Havell.jpeg, alt=Painting with a body of water with sailing ships in the foreground and a city in the background,

The I-695 Inner Belt shown on this map was never built.

The I-695 Inner Belt shown on this map was never built.

In the 1970s, after years of economic downturn, Boston boomed again. Financial institutions were granted more latitude, more people began to play the market, and Boston became a leader in the

In the 1970s, after years of economic downturn, Boston boomed again. Financial institutions were granted more latitude, more people began to play the market, and Boston became a leader in the

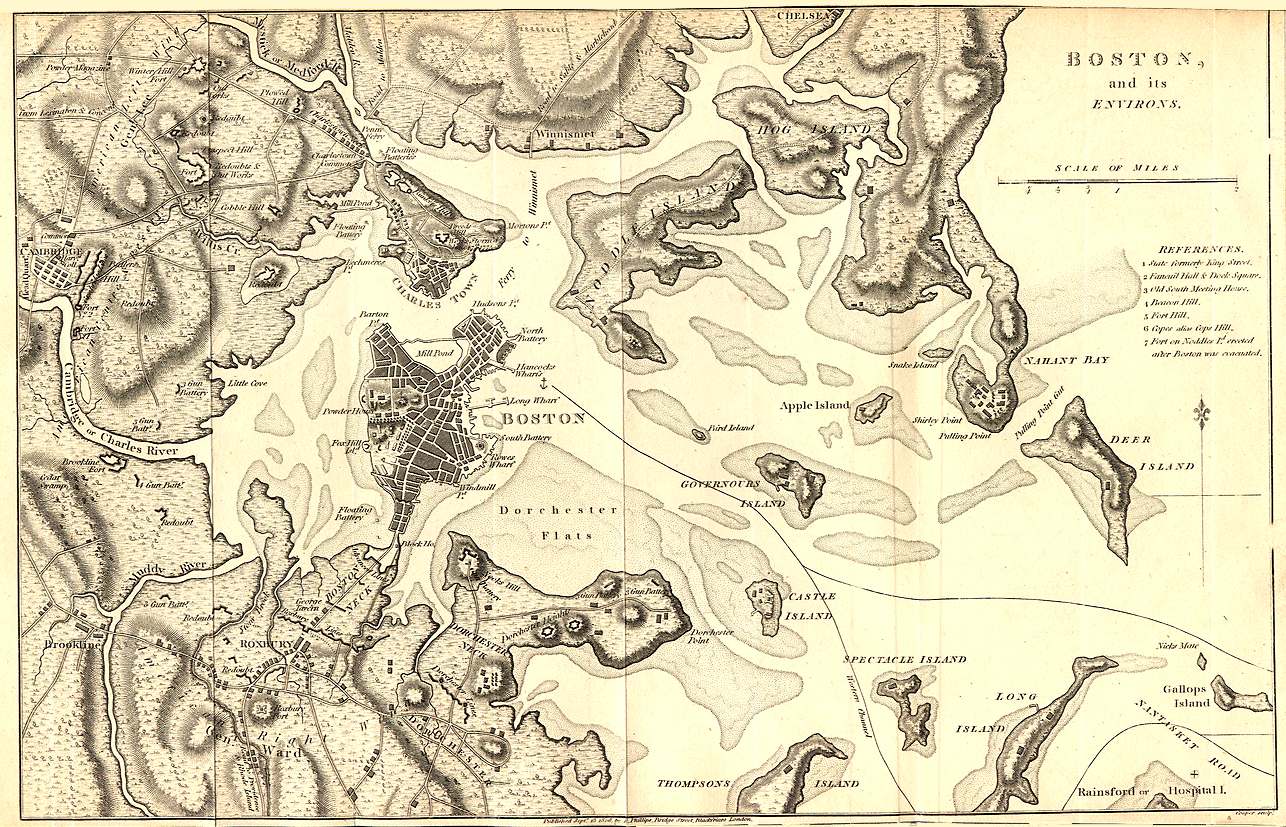

The City of Boston has expanded in two ways—through landfill and through annexation of neighboring municipalities.

Between 1630 and 1890, the city tripled its physical size by

The City of Boston has expanded in two ways—through landfill and through annexation of neighboring municipalities.

Between 1630 and 1890, the city tripled its physical size by  Timeline of annexations, secessions, and related developments (incomplete):

* 1705 – Hamlet of Muddy River split off to incorporate as

Timeline of annexations, secessions, and related developments (incomplete):

* 1705 – Hamlet of Muddy River split off to incorporate as

File:Oldandnewboston.jpg, Original Boston shoreline vs. 1903

File:Boston 1630 1675.jpg, Boston in 1630 vs. 1880. The original area of the Shawmut Peninsula was substantially expanded by landfill.

File:Boston 1772.png, Boston in 1772 vs. 1880

File:1852 Middlesex Canal (Massachusetts) map.jpg, Greater Boston in 1850 (Middlesex Canal highlighted)

File:Situationsplan von Boston (Massachusetts).jpg, A larger view of Boston in 1888 (''see also Colonial wide-area view, 1814 map, 1842 map, 1880 railroad map, 1903 map'')

The Boston Historical SocietyBoston Mapjunction

– Over 200 historical maps since 1630 and aerial photos compared with Maps of Today

City of Boston Archaeology Program and Lab

– The City of Boston has a City Archaeologist on staff to oversee any lots of land to be developed for historical artifacts and significance, and to manage the archaeological remains located on public land in Boston, and also has a City Archaeology Program and an Archaeology Laboratory, Education and Curation Center.

The Freedom House Photographs

Collection contains over 2,000 images of Roxbury people, places and events, 1950–1975 (Archives and Special Collections of the Northeastern University Libraries in Boston, MA).

Reading and Everyday Life in Antebellum Boston: The Diary of Daniel F. and Mary D. Child

* * * ] {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Boston History of Boston,

The written history of

The written history of Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

begins with a letter drafted by the first European inhabitant of the Shawmut Peninsula

Shawmut Peninsula is the promontory of land on which Boston, Massachusetts was built. The peninsula, originally a mere in area,Miller, Bradford A., "Digging up Boston: The Big Dig Builds on Centuries of Geological Engineering", GeoTimes, Octo ...

, William Blaxton

William Blaxton (also spelled William Blackstone; 1595 – 26 May 1675) was an early English settler in New England and the first European settler of Boston and Rhode Island.

Early life and education

William Blaxton was born in Horncastle, Li ...

. This letter is dated September 7, 1630, and was addressed to the leader of the Puritan settlement of Charlestown, Isaac Johnson. The letter acknowledged the difficulty in finding potable water on that side of Back Bay

Back Bay is an officially recognized Neighborhoods in Boston, neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, built on Land reclamation, reclaimed land in the Charles River basin. Construction began in 1859, as the demand for luxury housing exceeded the ...

. As a remedy, Blaxton advertised an excellent spring at the foot of what is now Beacon Hill and invited the Puritans to settle with him on Shawmut.

Boston was named and officially incorporated on September 30, 1630 (Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, they refer to the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries betwe ...

). The city quickly became the political, commercial, financial, religious and educational center of Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

and grew to play a central role in the history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

of the United States.

When harsh British retaliation for the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was a seminal American protest, political and Mercantilism, mercantile protest on December 16, 1773, during the American Revolution. Initiated by Sons of Liberty activists in Boston in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colo ...

resulted in further violence by the colonists, the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

erupted in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

. Colonists besieged the British in the city, fighting a famous battle at Breed's Hill

The Bunker Hill Monument is a monument erected at the site of the Battle of Bunker Hill in Boston, Massachusetts, which was among the first major battles between the United Colonies and the British Empire in the American Revolutionary War. The ...

in Charlestown on June 17, 1775—a battle lost by the colonists but one that inflicted great damage on British forces. The colonists later won the Siege of Boston

The siege of Boston (April 19, 1775 – March 17, 1776) was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War. In the siege, Patriot (American Revolution), American patriot militia led by newly-installed Continental Army commander George Wash ...

, forcing the British to evacuate the city on March 17, 1776. However, the combination of American and British blockades of the town and its port during the conflict seriously damaged the economy, leading to the exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* Ex ...

of two-thirds of its population in the 1770s.

The city recovered after 1800 and re-established its role as the transportation hub for New England with a network of railroads. Beyond a renewed economic success the re-invigorated Boston became the intellectual, educational and medical center of the nation. Along with New York, Boston became the financial center of the United States in the 19th century, and the large amount of capital available for investment there was crucial in funding the expansion of a nationwide railroad.

During and before the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

Boston was the launching pad and funding base for many of the country's anti-slavery activities. In the 19th century city politics and society became dominated by a financial elite known as the Boston Brahmin

The Boston Brahmins are members of Boston's historic upper class. From the late 19th century through the mid-20th century, they were often associated with a cultivated New England accent, Harvard University, Anglicanism, and traditional Britis ...

s. This entrenched power base squared off against the political challenge of more recent Catholic immigrants for the rest of the 19th century. Wealthy Irish Catholic political dynasties, typified by the Kennedy Family

The Kennedy family () is an American political family that has long been prominent in American politics, public service, entertainment, and business. In 1884, 35 years after the family's arrival from County Wexford, Ireland, Patrick Joseph "P ...

, assumed political control of the city by 1900. This control has been substantially maintained for more than a century, however this power has swayed as Boston continues to become more diverse.

The industrial base of the region, financed by Boston capital, reached its zenith around 1950. The city went into decline

Decline may refer to:

*Decadence, involves a perceived decay in standards, morals, dignity, religious faith, or skill over time

*in marketing, the stage in the product life cycle when demand for a product begins to taper off

* "Decline" (song), 20 ...

after the middle of the 20th century when thousands of textile mills and other factories were closed down as the United States began a long deindustrialization. By the early 21st century the city's economy recovered, moving from an industrial base to one centered on education, medicine, and high technology, especially biotechnology

Biotechnology is a multidisciplinary field that involves the integration of natural sciences and Engineering Science, engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms and parts thereof for products and services. Specialists ...

startups

A startup or start-up is a company or project undertaken by an Entrepreneurship, entrepreneur to seek, develop, and validate a scalable business model. While entrepreneurship includes all new businesses including self-employment and businesses tha ...

. The many towns surrounding Boston became residential suburbs that now house the city's large population of white collar workers

A white-collar worker is a person who performs professional service, desk, managerial, or administrative work. White-collar work may be performed in an office or similar setting. White-collar workers include job paths related to government, con ...

.

Indigenous era

Prior toEuropean colonization

The phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by various civilizations such as the Phoenicians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Han Chinese, and A ...

the region around modern-day Boston was inhabited by the Indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology)

In biogeography, a native species is indigenous to a given region or ecosystem if its presence in that region is the result of only local natural evolution (though often populari ...

Massachusett people

The Massachusett are a Native American tribe from the region in and around present-day Greater Boston in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name comes from the Massachusett language term for "At the Great Hill," referring to the Blue Hills ...

. Their habitation consisted of small, seasonal communities along what is now the Charles River

The Charles River (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ), sometimes called the River Charles or simply the Charles, is an river in eastern Massachusetts. It flows northeast from Hopkinton, Massachusetts, Hopkinton to Boston along a highly me ...

. The river was accurately named ''Quinobequin'' in the Algonquin language

Algonquin (also spelled Algonkin; in Algonquin: or ) is either a distinct Algonquian languages, Algonquian language closely related to the Ojibwe language or a particularly divergent Ojibwe language dialects, Ojibwe dialect. It is spoken, alon ...

of the Massachusett, and they knew it as "the meandering one". The people who lived in the area most likely moved between inland winter homes along the meanders of the Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

and summer communities on the coast. Game was most easily hunted inland during bare-tree seasons while the fishing shoals and shellfish beds on the tidal flats of Boston harbor were more comfortably exploited during the summer months.

Being surrounded by mudflat

Mudflats or mud flats, also known as tidal flats or, in Ireland, slob or slobs, are coastal wetlands that form in intertidal areas where sediments have been deposited by tides or rivers. A global analysis published in 2019 suggested that tidal ...

s and salt marsh

A salt marsh, saltmarsh or salting, also known as a coastal salt marsh or a tidal marsh, is a coastal ecosystem in the upper coastal intertidal zone between land and open saltwater or brackish water that is regularly flooded by the tides. I ...

es, the Shawmut Peninsula

Shawmut Peninsula is the promontory of land on which Boston, Massachusetts was built. The peninsula, originally a mere in area,Miller, Bradford A., "Digging up Boston: The Big Dig Builds on Centuries of Geological Engineering", GeoTimes, Octo ...

itself was more sparsely occupied than its surroundings before the arrival of Europeans. Nevertheless, archeological excavations have revealed one of the oldest fish weirs in New England on Boylston Street. Native people constructed this weir to trap fish as early as 7,000 years before European arrival in the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the 180th meridian.- The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Geopolitically, ...

.

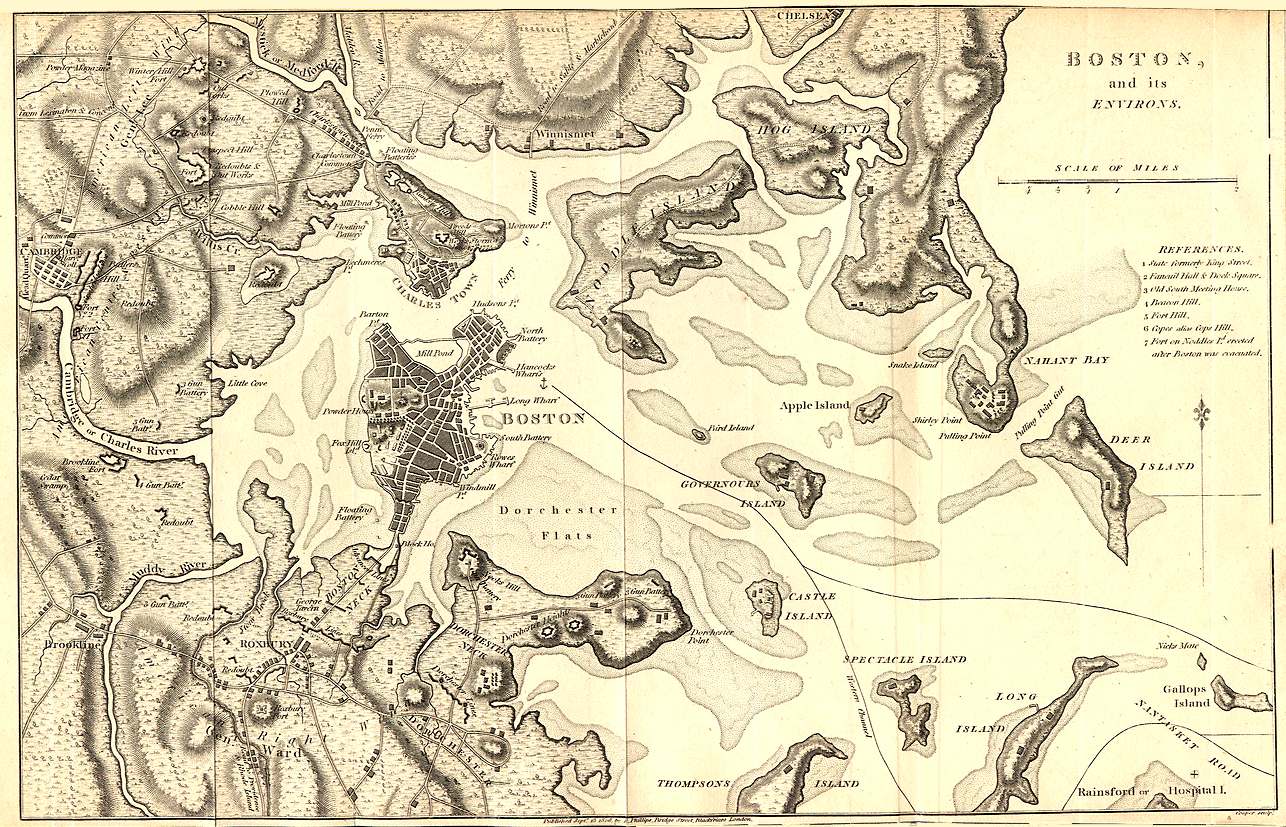

The Shawmut Peninsula

Shawmut Peninsula is the promontory of land on which Boston, Massachusetts was built. The peninsula, originally a mere in area,Miller, Bradford A., "Digging up Boston: The Big Dig Builds on Centuries of Geological Engineering", GeoTimes, Octo ...

was originally connected with the mainland to its south by a narrow isthmus

An isthmus (; : isthmuses or isthmi) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea count ...

, Boston Neck

The Boston Neck or Roxbury Neck was a narrow strip of land connecting the then-peninsular city of Boston to the mainland city of Roxbury (now a neighborhood of Boston). The surrounding area was gradually filled in as the city of Boston expan ...

, and was surrounded by Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor is a natural harbor and estuary of Massachusetts Bay, located adjacent to Boston, Massachusetts. It is home to the Port of Boston, a major shipping facility in the Northeastern United States.

History 17th century

Since its dis ...

and Back Bay

Back Bay is an officially recognized Neighborhoods in Boston, neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, built on Land reclamation, reclaimed land in the Charles River basin. Construction began in 1859, as the demand for luxury housing exceeded the ...

, an estuary

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime enviro ...

of the Charles River

The Charles River (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ), sometimes called the River Charles or simply the Charles, is an river in eastern Massachusetts. It flows northeast from Hopkinton, Massachusetts, Hopkinton to Boston along a highly me ...

. This neck of land was surrounded by infill beginning in 1803 and expanded to dozens of times its original width by the turn of the 20th century.

Foundation by Europeans

Blaxton Era (1624–1630)

The first European to live in what would become Boston wasWilliam Blaxton

William Blaxton (also spelled William Blackstone; 1595 – 26 May 1675) was an early English settler in New England and the first European settler of Boston and Rhode Island.

Early life and education

William Blaxton was born in Horncastle, Li ...

. He was directly responsible for the foundation of Boston by Puritan colonizers in 1630. Blaxton had joined the failed Ferdinando Gorges

Sir Ferdinando Gorges ( – 24 May 1647) was a naval and military commander and governor of the important port of Plymouth in England. He was involved in Essex's Rebellion against the Queen, but escaped punishment by testifying against the ma ...

expedition to America in 1623, which never landed. He eventually arrived later in 1623, as a chaplain to the subsequent expedition of Ferdinando's son, Robert Gorges

Robert Gorges (c. 1595 – late 1620s) was a captain in the Royal Navy and briefly Governor-General of New England from 1623 to 1624. He was the son of Sir Ferdinando Gorges. After having served in the Venetian wars, Gorges was given a commi ...

, aboard the ship ''Katherine''. This expedition landed in Weymouth, Massachusetts

Weymouth is a city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is one of 13 municipalities in the state to have city forms of government while retaining "town of" in their official names. It is named after Weymouth, Dorset, a coastal town ...

, five miles south of what is now Boston''.''

By 1625 the colony at Weymouth had failed and all of his fellow travelers returned to England. Blaxton remained, moving five miles north to a 1 mi2 rocky bulge at the end of a swampy isthmus surrounded on all sides by mudflats. Blaxton thus became the first colonist to settle in what would become Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

. He lived at the Western end of the Shawmut Peninsula

Shawmut Peninsula is the promontory of land on which Boston, Massachusetts was built. The peninsula, originally a mere in area,Miller, Bradford A., "Digging up Boston: The Big Dig Builds on Centuries of Geological Engineering", GeoTimes, Octo ...

at the foot of what is now Beacon Hill and was entirely alone for more than five years.

Puritan Era (1630–1750)

Invitation from Blaxton

In 1629 Isaac Johnson landed with thePuritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

in nearby Charlestown, having left Salem

Salem may refer to:

Places

Canada

* Salem, Ontario, various places

Germany

* Salem, Baden-Württemberg, a municipality in the Bodensee district

** Salem Abbey (Reichskloster Salem), a monastery

* Salem, Schleswig-Holstein

Israel

* Salem (B ...

for want of food. Blaxton and Johnson had been university contemporaries at Emmanuel College, Cambridge

Emmanuel College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1584 by Sir Walter Mildmay, Chancellor of the Exchequer to Elizabeth I. The site on which the college sits was once a priory for Dominican mo ...

. The rockier highlands of Charlestown lacked easily tappable wells. Knowing of this difficulty, Blaxton wrote an historic letter in September 1630 to Johnson and his group of Puritans that advertised Boston's excellent natural spring, and invited them to settle on his land. This they did over the course of September 1630.

Renamed "Boston"

One of Johnson's last official acts as the leader of the Charlestown community before dying on September 30, 1630, was to name the new settlement across the river "Boston." He named the settlement after his hometown in Lincolnshire, from which he, his wife (namesake of the ''Arbella

''Arbella'' or ''Arabella'' was the flagship of the Winthrop Fleet on which Governor John Winthrop, other members of the Company (including William Gager), and Puritan emigrants transported themselves and the Charter of the Massachusetts Bay C ...

'') and John Cotton (grandfather of Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a Puritan clergyman and author in colonial New England, who wrote extensively on theological, historical, and scientific subjects. After being educated at Harvard College, he join ...

) had emigrated

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanentl ...

to New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. The name of the English city ultimately derives from that town's patron saint, St. Botolph, in whose church John Cotton served as the rector until his emigration with Johnson. In early sources the Lincolnshire Boston was known as "St. Botolph's town", later contracted to "Boston". Prior to this renaming the settlement on the peninsula had been known as "Shawmut" by Blaxton and "Trimountaine" by the Puritan settlers he had invited.

Settlement on Shawmut Peninsula

The Puritans settled around the advertised springs on the north side of what is now Beacon Hill (at the time called "Trimountaine" from its three peaks). Blaxton negotiated a grant of for himself in the final paperwork with Johnson, amounting to around 10% of the peninsula's total area. However, by 1633 the new town's 4,000 citizens made retention of such a large parcel untenable and Blaxton sold all but six acres back to the Puritans in 1634 for £30 ($5,455 in adjusted USD). Governor Winthrop, Johnson's successor as leader of the settlement, purchased the land through a one-time tax on Boston residents of 6 shillings (around $50 adjusted) per head. This land became a town commons open to public grazing. It now forms the bulk ofBoston Common

The Boston Common is a public park in downtown Boston, Massachusetts. It is the oldest city park in the United States. Boston Common consists of of land bounded by five major Boston streets: Tremont Street, Park Street, Beacon Street, Charl ...

, the largest public park

An urban park or metropolitan park, also known as a city park, municipal park (North America), public park, public open space, or municipal gardens (United Kingdom, UK), is a park or botanical garden in cities, densely populated suburbia and oth ...

in present-day downtown Boston

Downtown Boston is the central business district of Boston, Massachusetts, United States. Boston was founded in 1630. The largest of the city's commercial districts, Downtown is the location of many corporate or regional headquarters; city, c ...

.

After Johnson's death the Episcopalian

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protes ...

Blaxton did not get along with the Puritan leaders of the Boston church, which rapidly became radically fundamentalist in its outlook as it began executing religious dissidents such as Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

. In 1635 Blaxton moved about south of Boston to what the Indians then called the Pawtucket River and is today known as the Blackstone River

The Blackstone River in the United States is a river that flows through Massachusetts and Rhode Island. It is long with a drainage area of 475 mi2 (1229 km2). It drains into the tidal river, Pawtucket River at Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Pawtuck ...

in Cumberland, Rhode Island

Cumberland is the northeasternmost town in Providence County, Rhode Island, United States, first settled in 1635 and incorporated in 1746. The population was 36,405 at the 2020 census, making it the seventh-largest municipality and the largest ...

. He was that region's first European settler, arriving one year before Roger Williams

Roger Williams (March 1683) was an English-born New England minister, theologian, author, and founder of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Pl ...

established Providence Plantations

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Island S ...

.

Original topography of the peninsula

The peninsula on which the Puritans settled was rocky scrubland with few trees. It held three major hills: Copps Hill (now the North End), Fort Hill (later theFinancial District

A financial district is usually a central area in a city where financial services firms such as banks, insurance companies, and other related finance corporations have their headquarters offices. In major cities, financial districts often host ...

), and Trimountaine ( Beacon Hill). Trimountaine was the tallest of the three, with its name coming from its three separate peaks. The name was retained for the hill and in later years Trimountaine would be shortened to Tremont, for which Tremont Street

Tremont Street is a major thoroughfare in Boston, Massachusetts.

Tremont Street begins at Government Center, Boston, Massachusetts, Government Center in Boston's city center as a continuation of Cambridge Street, and forms the eastern edge of ...

was named.

The three peaks of Trimountaine were,

# Cotton Hill—named for John Cotton, and later renamed Pemberton Hill (now Pemberton Square

Pemberton Square (est. 1835) in the Government Center area of Boston, Massachusetts, was developed by P.T. Jackson in the 1830s as an architecturally uniform mixed-use enclave surrounding a small park. In the mid-19th century both private resi ...

),

# Centry or Sentry Hill—the present location of the Massachusetts State House, and

# Mount Whoredom—also known as Mount Vernon, now the location of Louisburg Square

Louisburg Square is a street in the Beacon Hill neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, bisected by a small private park. The park, which is bounded by Pinckney Street to the north and Mount Vernon Street to the south, is maintained by the Louis ...

, home to some of the most expensive real estate in the nation.

Over the next two centuries the three hills would be regraded and the geography of the area transformed through landfill and annexation. Beacon Hill or Trimountaine, though shortened between 1807 and 1824, remains a prominent feature of the Boston cityscape. It received its current name from the signal beacon erected on its highest peak to warn outlying towns of danger.

Response to 1684 charter revocation

In 1684, fearing that the rumored revocation of the

In 1684, fearing that the rumored revocation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of M ...

's Charter by King Charles II would come to pass, Boston city fathers sought to buttress their fifty year old claim to the land of the Shawmut Peninsula. To this end in early 1684 they attempted to secure legal ownership of the Shawmut Peninsula from the descendents of Chickatawbut

Chickatawbut (died 1633; also known as Cicatabut and possibly as Oktabiest before 1622) was the sachem, or leader, of a large group of indigenous people known as the Massachusett tribe in what is now eastern Massachusetts, United States, during th ...

(d. 1633), the Massachusett

The Massachusett are a Native American tribe from the region in and around present-day Greater Boston in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name comes from the Massachusett language term for "At the Great Hill," referring to the Blue Hills ...

sachem

Sachems and sagamores are paramount chiefs among the Algonquians or other Native American tribes of northeastern North America, including the Iroquois. The two words are anglicizations of cognate terms (c. 1622) from different Eastern Alg ...

at the time Blaxton first settled on the peninsula, fifty years prior. Such a descendent was located, a sachem named Josias Wampatuck. There is little evidence that this sachem, his grandfather Chickatawbut or any of their people ever inhabited the peninsula, however the lack of formal legal documents involving Indians during the Blaxton transactions encouraged the creation of a backdated deed

A deed is a legal document that is signed and delivered, especially concerning the ownership of property or legal rights. Specifically, in common law, a deed is any legal instrument in writing which passes, affirms or confirms an interest, right ...

(known in English common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

as a "quitclaim

Generally, a quitclaim is a formal renunciation of a legal claim against some other person, or of a right to land. A person who quitclaims renounces or relinquishes a claim to some legal right, or transfers a legal interest in land. Originally a c ...

") which Josias duly signed on March 19, 1684 (see document at right, and its transcription). The charter was revoked as promised later that year on the advice of colonial administrator Edward Randolph

Edward Randolph (~October 1690 – after 1756), sometimes referred to as Edward Randolph of Bremo, was a ship captain, a London tobacco merchant, and the seventh and youngest son of William Randolph and Mary Isham.

Biography

In 1713, Randolph ...

.

Colonial era

Early colonists believed that Boston was a community with a special covenant with God, as captured in Winthrop's " City upon a Hill" metaphor. This influenced every facet of Boston life, and made it imperative that colonists legislate morality as well as enforce marriage, church attendance, education in the Word of God, and the persecution of sinners. One of the first schools in America,

Early colonists believed that Boston was a community with a special covenant with God, as captured in Winthrop's " City upon a Hill" metaphor. This influenced every facet of Boston life, and made it imperative that colonists legislate morality as well as enforce marriage, church attendance, education in the Word of God, and the persecution of sinners. One of the first schools in America, Boston Latin School

The Boston Latin School is a Magnet school, magnet Latin schools, Latin Grammar schools, grammar State school, state school in Boston, Massachusetts. It has been in continuous operation since it was established on April 23, 1635. It is the old ...

(1635), and the first college in America, Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate education, undergraduate college of Harvard University, a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Part of the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Scienc ...

(1636), were founded shortly after Boston's European settlement.

Town officials in colonial Boston were chosen annually; positions included

Town officials in colonial Boston were chosen annually; positions included selectman

The select board or board of selectmen is commonly the executive arm of the government of New England towns in the United States. The board typically consists of three or five members, with or without staggered terms. Three is the most common numb ...

, assay

An assay is an investigative (analytic) procedure in laboratory medicine, mining, pharmacology, environmental biology and molecular biology for qualitatively assessing or quantitatively measuring the presence, amount, or functional activity ...

master, culler of staves, Fence Viewer A fence viewer is a town or city official who administers fence laws by inspecting new fences and settles disputes arising from trespass by livestock that had escaped enclosure.

The office of fence viewer is one of the oldest appointments in New En ...

, hayward, hogreeve, measurer of boards, pounder, sealer of leather, tithing

A tithing or tything was a historic English legal, administrative or territorial unit, originally ten hides (and hence, one tenth of a hundred). Tithings later came to be seen as subdivisions of a manor or civil parish. The tithing's leader or ...

man, viewer of bricks, water bailiff

A water bailiff is a law-enforcement officer responsible for the policing of bodies of water, such as rivers, lakes or the coast. The position has existed in many jurisdictions throughout history.

Scotland

In Scotland, under the Salmon and Fresh ...

, and woodcorder.

Boston's Puritans looked askance at unorthodox religious ideas, and exiled or punished dissenters. During the Antinomian Controversy

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of ...

of 1636 to 1638 religious dissident leader Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (; July 1591 – August 1643) was an English-born religious figure who was an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her strong religious formal d ...

and Puritan clergyman John Wheelwright

John Wheelwright (c. 1592–1679) was a Puritan clergyman in England and America, noted for being banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Antinomian Controversy, and for subsequently establishing the town of Exeter, New Hamps ...

were both banished from the colony. Baptist minister Obadiah Holmes

Obadiah Holmes (1610 – 15 October 1682) was an early Rhode Island settler, and a Baptist minister who was whipped in the Massachusetts Bay Colony for his religious beliefs and activism. He became the pastor of the Baptist Church in Newport, ...

was imprisoned and publicly whipped in 1651 because of his religion and Henry Dunster

Henry Dunster (November 26, 1609 (baptized) – February 27, 1658/59) was an Anglo-American Puritan clergyman and the first president of Harvard College. Brackney says Dunster was "an important precursor" of the Baptist denomination in America ...

, the first president of Harvard College during the 1640s–50s, was persecuted for espousing Baptist beliefs. By 1679, Boston Baptists were bold enough to open their own meetinghouse, which was promptly closed by colonial authorities. Expansion and innovation in practice and worship characterized the early Baptists despite the restrictions on their religious liberty. On June 1, 1660, Mary Dyer

Mary Dyer (born Marie Barrett; c. 1611 – 1 June 1660) was an English and colonial American Puritan-turned-Quaker who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony d ...

was hanged on Boston Common for repeatedly defying a law banning Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

from being in the colony.

In 1652 during the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when Kingdom of England, England and Wales, later along with Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, were governed as a republi ...

, the Massachusetts General Court

The Massachusetts General Court, formally the General Court of Massachusetts, is the State legislature (United States), state legislature of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts located in the state capital of Boston. Th ...

authorized Boston silversmith John Hull John Hull may refer to:

Politicians

*John Hull (MP for Hythe) (died 1540 or after), MP for Hythe

*John Hull (MP for Exeter) (died 1549), English MP for Exeter

* John A. T. Hull (1841–1928), American politician

* John C. Hull (politician) (1870� ...

to produce coinage. In 1661 after Charles II came to the throne, the English government considered the Boston mint to be treasonous. However, the mint continued operations until 1682. The coinage was a contributing factor to the revocation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony charter in 1684.

The Boston Post Road

The Boston Post Road was a system of mail-delivery routes between New York City and Boston, Massachusetts, that evolved into one of the first major highways in the United States.

The three major alignments were the Lower Post Road (now U.S. Ro ...

connected the city to New York and the major settlements in Central and Western Massachusetts. The lower route ran near present-day U.S. 1 via Providence, Rhode Island

Providence () is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Rhode Island, most populous city of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. The county seat of Providence County, Rhode Island, Providence County, it is o ...

. The upper route, laid out in 1673, left via Boston Neck and followed present-day U.S. Route 20

U.S. Route 20 or U.S. Highway 20 (US 20) is an east–west United States Numbered Highway that stretches from the Pacific Northwest east to New England. The "0" in its route number indicates that US 20 is a major coast-to-coast route. ...

until around Shrewsbury, Massachusetts

Shrewsbury (/ˈʃruzberi/ ''SHROOZ-bury'') is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 38,325 according to the 2020 United States census, in nearly 15,000 households.

Incorporated in 1727, Shrewsbury prospere ...

. It continued through Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engl ...

, Springfield, and New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound. With a population of 135,081 as determined by the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, New Haven is List ...

.

From 1686 until 1689, Massachusetts and surrounding colonies were united. This larger province, known as the

From 1686 until 1689, Massachusetts and surrounding colonies were united. This larger province, known as the Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was a short-lived administrative union of English colonies covering all of New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies, with the exception of the Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvani ...

, was governed by Sir Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 – 24 February 1714; also spelled ''Edmond'') was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other ...

, an appointee of King James II

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685, until he was deposed in the 1688 Glori ...

. Andros, who supported the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

in a largely Puritan city, grew increasingly unpopular. On April 18, 1689, he was overthrown due to a brief revolt. The Dominion was not reestablished.

Boston's first circulating library was established in 1756 which included 1,200 volumes of books. During this period, many wealthy persons amassed large libraries and loaned books within their social circles.

Disasters in the 1700s

A particularly virulent sequence of six smallpox outbreaks took place from 1636 to 1698. In 1721–1722, the most severe epidemic occurred, killing 844 people. Out of a population of 10,500, 5889 caught the disease, 844 (14%) died, and at least 900 fled the city, thereby spreading the virus. Colonists tried to prevent the spread of smallpox by isolation. For the first time in America,inoculation

Inoculation is the act of implanting a pathogen or other microbe or virus into a person or other organism. It is a method of artificially inducing immunity against various infectious diseases. The term "inoculation" is also used more generally ...

was tried; it causes a mild form of the disease. Inoculation was itself very controversial because of the threat that the procedure itself could be fatal to 2% of those who were treated, or otherwise spread the disease. It was introduced by Zabdiel Boylston

Zabdiel Boylston, FRS (March 9, 1679 – March 1, 1766) was a physician in the Boston area. As the first medical school in North America was not founded until 1765, Boylston apprenticed with his father, an English-born surgeon named Thomas Boyl ...

and Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a Puritan clergyman and author in colonial New England, who wrote extensively on theological, historical, and scientific subjects. After being educated at Harvard College, he join ...

.

In 1755, Boston endured the largest earthquake ever to hit the Northeastern United States, (estimated at 6.0 to 6.3 on the Richter magnitude scale

The Richter scale (), also called the Richter magnitude scale, Richter's magnitude scale, and the Gutenberg–Richter scale, is a measure of the strength of earthquakes, developed by Charles Richter in collaboration with Beno Gutenberg, and pr ...

), called the ''Cape Ann earthquake

The 1755 Cape Ann earthquake took place off the coast of the British Province of Massachusetts Bay (present-day Massachusetts) on November 18. At between 6.0 and 6.3 on the Richter scale, it remains the largest earthquake in the history of Massac ...

''. There was some damage to buildings, but no deaths.

The first " Great Fire" of Boston destroyed 349 buildings on March 20, 1760. It was one of many significant fires fought by the Boston Fire Department

The Boston Fire Department provides fire services and first responder emergency medical services to the city of Boston, Massachusetts. It also responds to such incidents as motor vehicle accidents, dangerous goods, hazardous material spills, util ...

.

Boston and the American Revolution, 1765–1775

Boston had taken an active role in the protests against the Stamp Act of 1765. Its merchants avoided the customs duties which angered London officials and led to a crackdown on smuggling. GovernorThomas Pownall

Thomas Pownall (bapt. 4 September 1722 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S. – 25 February 1805) was a British colonial official and politician. He was governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay from 1757 to 1760, and afterwards sat in th ...

(1757 to 1760) tried to be conciliatory, but his replacement Governor Francis Bernard 1760–1769) was a hard-liner who wanted to stamp out the opposition voices that were growing louder and louder in town meetings and pamphlets. Historian Pauline Maier says that his letters to London greatly influenced officials there, but they "distorted" reality. "His misguided conviction that the 'faction' had espoused violence as its primary method of opposition, for example, kept him from recognizing the radicals' peace-keeping efforts.... Equally dangerous, Bernard's elaborate accounts were sometimes built on insubstantial evidence." Warden argues that Bernard was careful not to explicitly ask London for troops, but his exaggerated accounts strongly suggested they were needed. In the fall of 1767 he warned about a possible insurrection in Boston any day, and his exaggerated report of one disturbance in 1768, "certainly had given Lord Hillsboro the impression that troops were the only way to enforce obedience in the town." Warden notes that other key British officials in Boston wrote London with the "same strain of hysteria." Four thousand British Army troops arrived in Boston in October 1768 as a massive show of force; tensions escalated.

By the late 1760s, Patriot colonists focused on the

By the late 1760s, Patriot colonists focused on the rights of Englishmen

The "rights of Englishmen" are the traditional rights of English subjects and later English-speaking subjects of the The Crown, British Crown.

In the 18th century, some of the Patriot (American Revolution), colonists who objected to British ...

that they claimed to hold, especially the principle of " no taxation without representation" as articulated by John Rowe, James Otis Sr.

James Otis Sr. (1702–1778) was a prominent lawyer in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. His sons James Otis Jr. and Samuel Allyne Otis also rose to prominence, as did his daughter Mercy Otis Warren. He was often called "Colonel James" because ...

, Samuel Adams

Samuel Adams (, 1722 – October 2, 1803) was an American statesman, Political philosophy, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colonial Massachusetts, a le ...

and other Boston firebrands. Boston played a major role in the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

, including the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. On March 5, 1770, nine soldiers of the 29th Regiment of Foot

The 29th (Worcestershire) Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1694. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 36th (Herefordshire) Regiment of Foot to become the 1st Battalion, the Worcestershire R ...

opened fire at a crowd of Bostonians which was verbally and physically harassing them; five people were killed in what came to be known as the Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre, known in Great Britain as the Incident on King Street, was a confrontation, on March 5, 1770, during the American Revolution in Boston in what was then the colonial-era Province of Massachusetts Bay.

In the confrontati ...

, dramatically escalating tensions. The British Parliament, meanwhile, continued to insist on its right to tax the Britain's North American colonies and finally came up with a small tax on tea. Up and down the Thirteen Colonies, American colonists prevented merchants from selling the tea, but a shipment arrived in Boston Harbor. On December 16, 1773, members of the Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty was a loosely organized, clandestine, sometimes violent, political organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies founded to advance the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. It p ...

, disguised as Native Americans, dumped 342 chests of tea in the harbor in the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was a seminal American protest, political and Mercantilism, mercantile protest on December 16, 1773, during the American Revolution. Initiated by Sons of Liberty activists in Boston in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colo ...

. The Sons of Liberty decided to take action to defy Britain's new tax on tea, but the British government retaliated with a series of punitive laws, closing down the Port of Boston and stripping Massachusetts of its self-government. The other colonies rallied in solidarity behind Massachusetts, setting up the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates of twelve of the Thirteen Colonies held from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia at the beginning of the American Revolution. The meeting was organized b ...

, while arming and training militia units. The British sent more troops to Boston, and made its commander General Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator best known for his many years of service in North America, including serving as Commander-in-Chief, North America during the early days ...

the governor. Gage believed the Patriots were hiding munitions in the town of Concord, and he sent troops to capture them. Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, military officer and industrialist who played a major role during the opening months of the American Revolutionary War in Massachusetts, ...

, William Dawes

William Dawes Jr. (April 6, 1745 – February 25, 1799) was an American soldier, and was one of several men who, in April 1775, alerted minutemen in Massachusetts of the approach of British regulars prior to the Battles of Lexington and Concor ...

, and Dr. Samuel Prescott made their famous midnight rides to alert the Minutemen

Minutemen were members of the organized New England colonial militia companies trained in weaponry, tactics, and military strategies during the American Revolutionary War. They were known for being ready at a minute's notice, hence the name. Min ...

in the surrounding towns, who fought the resulting Battle of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775 were the first major military actions of the American Revolutionary War between the Kingdom of Great Britain and Patriot militias from America's Thirteen Colonies. Day-long running battl ...

in April 1775. It was the first battle of the American Revolution.

Militia units across New England rallied to the defense of Boston, and Congress sent in General George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

to take command. The British were trapped in the city, and suffered very heavy losses in their victory at the Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought on June 17, 1775, during the Siege of Boston in the first stage of the American Revolutionary War. The battle is named after Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Boston, Charlestown, Massachusetts, which was peri ...

.

Washington brought in artillery and forced the British out as the patriots took full control of Boston. The American victory on March 17, 1776, is celebrated as Evacuation Day. The city has preserved and celebrated its revolutionary past, from the harboring of the to the many famous sites along the Freedom Trail

The Freedom Trail is a path through Boston that passes by 16 locations significant to the history of the United States. It winds from Boston Common in downtown Boston, to the Old North Church in the North End and the Bunker Hill Monument i ...

.

19th century

Economic and population growth

Boston was transformed from a relatively small and economically stagnant town in 1780 to a bustling seaport and cosmopolitan center with a large and highly mobile population by 1800. It had become one of the world's wealthiest international trading ports, exporting products like rum, fish, salt and tobacco. The upheaval of the American Revolution, and the British naval blockade that shut down its economy, had caused a majority of the population to flee the city. From a base of 10,000 in 1780, the population approached 25,000 by 1800. The abolition of slavery in the state in 1783 gave blacks greater physical mobility, but their social mobility was slow. Boston was part of the New England corner oftriangular trade

Triangular trade or triangle trade is trade between three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its major imports come. It has been used to offset ...

, receiving sugar from the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

and refining it into rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is often aged in barrels of oak. Rum originated in the Caribbean in the 17th century, but today it is produced i ...

and molasses

Molasses () is a viscous byproduct, principally obtained from the refining of sugarcane or sugar beet juice into sugar. Molasses varies in the amount of sugar, the method of extraction, and the age of the plant. Sugarcane molasses is usuall ...

, partly for export to Europe. Later, confectionery manufacturing would become another refined product made from similar raw materials. Related companies with facilities in Boston included the Boston Sugar Refinery (inventors of granulated sugar

White sugar, also called table sugar, granulated sugar, or regular sugar, is a commonly used type of sugar, made either of beet sugar or cane sugar, which has undergone a refining process. It is nearly pure sucrose.

Description

The refining ...

), Domino Sugar

Domino Foods, Inc. (also known as DFI and formerly known as W. & F.C. Havemeyer Company, Havemeyer, Townsend & Co. Refinery, and Domino Sugar) is a privately held sugar marketing and sales company based in Yonkers, New York, United States, tha ...

, the Purity Distilling Company, Necco

Necco (or NECCO ) was an American manufacturer of candy created in 1901 as the New England Confectionery Company through the merger of several small confectionery companies located in the Greater Boston area, with ancestral companies dating b ...

, Schrafft's

The Schrafft Candy Company was a candy, chocolate and cake company based in Sullivan Square, Charlestown, Massachusetts. In 1861, it introduced jelly beans to the United States and told the customers to send them off to civil war soldiers. ...

, Squirrel Brands

Squirrel Nut Caramels (chocolate flavored) and Squirrel Nut Zippers (vanilla flavored) were chewy caramel candy mixed with peanuts.

Description

Chocolate Squirrel caramels were the original flavor of Squirrel Nut brand caramels. The ingredients ...

(as the predecessor Austin T. Merrill Company of Roxbury) American Nut and Chocolate (1927) This legacy continued into the 20th century; by 1950, there were 140 candy companies in Boston. Others were located in and some moved to nearby Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

. The Boston Fruit Company

The Boston Fruit Company (1885–1899) was a fruit production and import business based in the port of Boston, Massachusetts. Andrew W. Preston and nine others established the firm to ship bananas and other fruit from the West Indies to north-east ...

began importing tropical fruit from the Caribbean in 1885; it is a predecessor of United Fruit Company

The United Fruit Company (later the United Brands Company) was an American multinational corporation that traded in tropical fruit (primarily bananas) grown on Latin American plantations and sold in the United States and Europe. The company was ...

and Chiquita Brands International

Chiquita Brands International S.à.r.l. (), formerly known as United Fruit Co., is a Swiss company producing and distributing bananas and other produce. The company operates under subsidiary brand names, including the flagship Chiquita bran ...

.

Boston had the status of a town; it was chartered as a city in 1822. The second mayor was Josiah Quincy III

Josiah Quincy III (; February 4, 1772 – July 1, 1864) was an American educator and political figure. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives (1805–1813), mayor of Boston (1823–1828), and President of Harvard University (182 ...

, who undertook infrastructure improvements in roads and sewers, and organized the city's dock area around the newly erected Faneuil Hall Marketplace, popularly known as Quincy Market. By the mid-19th century Boston was one of the largest manufacturing centers in the nation, noted for its garment production, leather goods, and machinery industries. Manufacturing overtook international trade to dominate the local economy. A network of small rivers bordering the city and connecting it to the surrounding region made for easy shipment of goods and allowed for a proliferation of mills and factories. The building of the Middlesex Canal

The Middlesex Canal was a 27-mile (44-kilometer) barge canal connecting the Merrimack River with the port of Boston. When operational it was 30 feet (9.1 m) wide, and 3 feet (0.9 m) deep, with 20 locks, each 80 feet (24 m) long and between 10 ...

extended this small river network to the larger Merrimack River and its mills, including the Lowell mills

The Lowell Mills were 19th-century textile mills that operated in the city of Lowell, Massachusetts, which was named after Francis Cabot Lowell; he introduced a new manufacturing system called the "Lowell system", also known as the " Waltham-Low ...

and mills on the Nashua River

The Nashua River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed October 3, 2011 is a tributary of the Merrimack River in Massachusetts and New Hampshire in the United States. It ...

in New Hampshire

New Hampshire ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

. By the 1850s, an even denser network of railroads (''see also List of railroad lines in Massachusetts

A list is a set of discrete items of information collected and set forth in some format for utility, entertainment, or other purposes. A list may be memorialized in any number of ways, including existing only in the mind of the list-maker, but ...

'') facilitated the region's industry and commerce. For example, in 1851, Eben Jordan and Benjamin L. Marsh opened the Jordan Marsh

Jordan Marsh was an American department store chain founded in 1841 by Eben Dyer Jordan and Benjamin L. Marsh. It was headquartered in Boston, Massachusetts, and operated throughout New England. The destruction of the historical flagship store o ...

Department store

A department store is a retail establishment offering a wide range of consumer goods in different areas of the store under one roof, each area ("department") specializing in a product category. In modern major cities, the department store mad ...

in downtown Boston. Thirty years later William Filene opened his own department store across the street, called Filene's

Filene's was an American department store chain founded in 1881 by William Filene. The historic Filene's Department Store in the Downtown Crossing district of Boston, Massachusetts housed the flagship store and headquarters, while branch store ...

.

Several turnpikes were constructed between cities to aid transportation, especially of cattle and sheep to markets. A major east–west route, the Worcester Turnpike (now Massachusetts Route 9

Route 9 is a major east–west state highway in Massachusetts, United States. Along with U.S. Route 20 (US 20), Route 2, and Interstate 90, Route 9 is one of the major east–west routes of Massachusetts. The western terminus is near th ...

), was constructed in 1810. Others included the Newburyport Turnpike (now Route 1) and the Salem Lawrence Turnpike (now Route 114).

Brahmin elite

Boston's "Brahmin elite" developed a particular semi-aristocratic value system by the 1840s—cultivated, urbane, and dignified, the ideal Brahmin was the very essence of enlightened aristocracy. He was not only wealthy, but displayed suitable personal virtues and character traits. The term was coined in 1861 by Dr.Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (; August 29, 1809 – October 7, 1894) was an American physician, poet, and polymath based in Boston. Grouped among the fireside poets, he was acclaimed by his peers as one of the best writers of the day. His most ...

The Brahmin had high expectations to meet: to cultivate the arts, support charities such as hospitals and colleges, and assume the role of community leader. Although the ideal called on him to transcend commonplace business values, in practice many found the thrill of economic success quite attractive. The Brahmins warned each other against "avarice" and insisted upon "personal responsibility." Scandal and divorce were unacceptable. The total system was buttressed by the strong extended family ties present in Boston society. Young men attended the same prep schools and colleges, and had their own way of talking. Heirs married heiresses. Family not only served as an economic asset, but also as a means of moral restraint. Most belonged to the Unitarian or Episcopal churches, although some were Congregationalists or Methodists. Politically, they were successively Federalists, Whigs, and Republicans.

A poem about Boston, attributed to various people, describes the city thus: "And here's to good old Boston / The land of the bean and the cod / Where Lowells talk only to Cabots / and Cabots talk only to God." While wealthy colonial families like the Lowells and Cabots (often called the ''Boston Brahmin

The Boston Brahmins are members of Boston's historic upper class. From the late 19th century through the mid-20th century, they were often associated with a cultivated New England accent, Harvard University, Anglicanism, and traditional Britis ...

s'') ruled the city, the 1840s brought waves of new immigrants from Europe. These included large numbers of Irish and Italians

Italians (, ) are a European peoples, European ethnic group native to the Italian geographical region. Italians share a common Italian culture, culture, History of Italy, history, Cultural heritage, ancestry and Italian language, language. ...

, giving the city a large Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

population.

Abolitionists

In 1831,

In 1831, William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an Abolitionism in the United States, American abolitionist, journalist, and reformism (historical), social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper ''The ...

founded '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

newsletter, in Boston. It advocated "immediate and complete emancipation of all slaves" in the United States, and established Boston as the center of the abolitionist movement. While living in Boston, David Walker published ''An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World.'' After the passing of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, Boston became a bastion of abolitionist thought. Attempts by slave-catchers to arrest fugitive slaves often proved futile, which included the notable case of Anthony Burns

Anthony Burns (May 31, 1834 – July 17, 1862) was an African-American man who escaped from slavery in Virginia in 1854. His capture and trial in Boston, and transport back to Virginia, generated wide-scale public outrage in the North and incre ...

and Kevin McLaughlin. After the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

in 1854, Boston also became the hub of efforts to send anti-slavery New Englanders to settle in Kansas Territory

The Territory of Kansas was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until January 29, 1861, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Slave and ...

through the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company

The New England Emigrant Aid Company (originally the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company) was a transportation company founded in Boston, Massachusetts by activist Eli Thayer in the wake of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed the population o ...

.

Irish

The earliest Irish settlers began arriving in the early 18th century. Initially, they were indentured servants who came to work in Boston and New England for five to seven years, before gaining their independence. They were mainly individuals and families, and they were forced to hide their religious roots since Catholicism was banned in the Bay Colony. Then in 1718, congregations of Presbyterians from Ulster in the north of Ireland began arriving in Boston Harbor. They were referred to as Ulster Irish but later were referred to as Scots-Irish because many of them had roots in Scotland. The Puritan leaders initially sent the Ulster Irish to the fringes of the Bay Colony, where they settled places like Belfast, Maine, Londonderry and Derry, New Hampshire, and Worcester, Massachusetts. But by 1729 they were permitted to set up a church in downtown Boston. Throughout the 19th century, Boston became a haven for Irish Catholic immigrants, especially following the Great Famine of the late 1840s. Their arrival transformed Boston from a singular, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant city to one that has progressively become more diverse. The Yankees hired Irish as workers and servants, but there was little social interaction. In the 1850s, an anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant movement was directed against the Irish, called the Know Nothing Party. But in the 1860s, many Irish immigrants joined the Union ranks to fight in the American Civil War, and that display of patriotism and valor began to soften the harsh sentiments of Yankees about the Irish. Nonetheless, as inNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, on July 14, 1863, a draft riot attempting to raid Union armories broke out among Irish Catholics in the North End, resulting in approximately 8 to 14 deaths. In the 1860 presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 6, 1860. The History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party ticket of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin emerged victoriou ...

, Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

received only 9,727 votes out of 20,371 cast in Boston (or 48 percent) while receiving 63 percent of the vote statewide, and Boston Irish Catholics mostly voted against Lincoln.

Even to the present day, Boston still commands the largest percentage of Irish-descended people of any city in the United States. With an expanding population, group loyalty, and block by block political organization, the Irish took political control of the city, leaving the Yankees in charge of finance, business and higher education. The Irish left their mark on the region in a number of ways: in still heavily Irish neighborhoods such as Charlestown and South Boston

South Boston (colloquially known as Southie) is a densely populated neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, United States, located south and east of the Fort Point Channel and abutting Dorchester Bay (Boston Harbor), Dorchester Bay. It has under ...

; in the name of the local basketball team, the Boston Celtics

The Boston Celtics ( ) are an American professional basketball team based in Boston. The Celtics compete in the National Basketball Association (NBA) as a member of the Atlantic Division (NBA), Atlantic Division of the Eastern Conference (NBA), ...

; in the dominant Irish-American political family, the Kennedys

The Kennedy family () is an American political family that has long been prominent in American politics, public service, entertainment, and business. In 1884, 35 years after the family's arrival from County Wexford, Ireland, Patrick Joseph "P ...

; in a large number of prominent local politicians, such as James Michael Curley

James Michael Curley (November 20, 1874 – November 12, 1958) was an American Democratic politician from Boston, Massachusetts. He served four terms as mayor of Boston between 1914 and 1955. Curley ran for mayor in every election for which he ...

, in the establishment of Catholic Boston College

Boston College (BC) is a private university, private Catholic Jesuits, Jesuit research university in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1863 by the Society of Jesus, a Catholic Religious order (Catholic), religious order, t ...

as a rival to Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

, and in underworld figures, such as Whitey Bulger

James Joseph "Whitey" Bulger Jr. (; September 3, 1929 – October 30, 2018) was an American organized crime boss who led the Winter Hill Gang, an Irish mob group based in the Winter Hill neighborhood of Somerville, Massachusetts, northw ...

.

Great Fire of 1872

TheGreat Boston Fire of 1872

The Great Boston Fire of 1872 was Boston's largest fire, and still ranks as one of the most costly fire-related property losses in American history. The conflagration began at 7:20 p.m. on Saturday, November 9, 1872, in the basement of a co ...

started at the corner of Summer Street and Kingston Street on November 9. In two days the conflagration destroyed about 65 acres (260,000 m2) of the city, including 776 buildings in the financial district

A financial district is usually a central area in a city where financial services firms such as banks, insurance companies, and other related finance corporations have their headquarters offices. In major cities, financial districts often host ...

, totaling $60 million in damage.

High culture

From the mid-to-late-19th century, the Boston Brahmins flourished culturally—they became renowned for its rarefied literary culture and lavish artistic patronage. Literary residents included, among many others, writersNathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (né Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associat ...

, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include the poems " Paul Revere's Ride", '' The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to comp ...

, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (; August 29, 1809 – October 7, 1894) was an American physician, poet, and polymath based in Boston. Grouped among the fireside poets, he was acclaimed by his peers as one of the best writers of the day. His most ...

, James Russell Lowell

James Russell Lowell (; February 22, 1819 – August 12, 1891) was an American Romantic poet, critic, editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the fireside poets, a group of New England writers who were among the first American poets to r ...

, and Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe ( ; May 27, 1819 – October 17, 1910) was an American author and poet, known for writing the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" as new lyrics to an existing song, and the original 1870 pacifist Mothers' Day Proclamation. She w ...

, as well as historians John Lothrop Motley

John Lothrop Motley (April 15, 1814 – May 29, 1877) was an American author and diplomat. As a popular historian, he is best known for his works on the Netherlands, the three volume work ''The Rise of the Dutch Republic'' and four volume ''His ...

, John Gorham Palfrey, George Bancroft

George Bancroft (October 3, 1800 – January 17, 1891) was an American historian, statesman and Democratic Party (United States), Democratic politician who was prominent in promoting secondary education both in his home state of Massachusetts ...

, William Hickling Prescott

William Hickling Prescott (May 4, 1796 – January 28, 1859) was an American historian and Hispanist, who is widely recognized by historiographers to have been the first American scientific historian. Despite having serious visual impairm ...

, Francis Parkman

Francis Parkman Jr. (September 16, 1823 – November 8, 1893) was an American historian, best known as author of '' The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky-Mountain Life'' and his monumental seven-volume '' France and England in North Ame ...

, Henry Adams