Traditionalist conservatism, often known as classical conservatism, is a

political

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

and

social philosophy

Social philosophy is the study and interpretation of society and social institutions in terms of ethical values rather than empirical relations. Social philosophers emphasize understanding the social contexts for political, legal, moral and cultur ...

that emphasizes the importance of transcendent moral principles, manifested through certain posited

natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

s to which it is claimed society should adhere. It is one of many different forms of

conservatism

Conservatism is a Philosophy of culture, cultural, Social philosophy, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, Convention (norm), customs, and Value (ethics and social science ...

. Traditionalist conservatism, as known today, is rooted in

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

's political philosophy, as well as the similar views of

Joseph de Maistre

Joseph Marie, comte de Maistre (1 April 1753 – 26 February 1821) was a Savoyard philosopher, writer, lawyer, diplomat, and magistrate. One of the forefathers of conservatism, Maistre advocated social hierarchy and monarchy in the period immedi ...

, who designated the

rationalist rejection of

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

during previous decades as being directly responsible for the

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the French First Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and Capital punishment in France, nu ...

which followed the

French Revolution. Traditionalists value

social ties

In social network analysis and mathematical sociology, interpersonal ties are defined as information-carrying connections between people. Interpersonal ties, generally, come in three varieties: ''strong'', ''weak'' or ''absent''. Weak social t ...

and the preservation of ancestral institutions above what they perceive as excessive

rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the Epistemology, epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge", often in contrast to ot ...

and

individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

. One of the first uses of the phrase "conservatism" began around 1818 with a

monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. C ...

newspaper named "''Le Conservateur''", written by

Francois Rene de Chateaubriand with the help of

Louis de Bonald

Louis Gabriel Ambroise, Vicomte de Bonald (; 2 October 1754 – 23 November 1840) was a French counter-revolutionary philosopher and politician. He is mainly remembered for developing a theoretical framework from which French sociology would eme ...

.

The modern concepts of

nation

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective Identity (social science), identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, t ...

,

culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

,

custom

Custom, customary, or consuetudinary may refer to:

Traditions, laws, and religion

* Convention (norm), a set of agreed, stipulated or generally accepted rules, norms, standards or criteria, often taking the form of a custom

* Mores, what is wid ...

,

convention, religious roots,

language revival

Language revitalization, also referred to as language revival or reversing language shift, is an attempt to halt or reverse the decline of a language or to revive an extinct one. Those involved can include linguists, cultural or community group ...

, and

tradition

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common e ...

are heavily emphasized in traditionalist conservatism.

Theoretical reason

The modern division of philosophy into theoretical philosophy and practical philosophyImmanuel Kant, ''Lectures on Ethics'', Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 41 ("On Universal Practical Philosophy"). Original text: Immanuel Kant, ''Kant’s Ge ...

is regarded as of secondary importance to

practical reason

In philosophy, practical reason is the use of reason to decide how to act. It contrasts with theoretical reason, often called speculative reason, the use of reason to decide what to believe. For example, agents use practical reason to decide whet ...

. The

state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

is also viewed as a social endeavor with spiritual and

organic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product ...

characteristics. Traditionalists think that any positive change arises based within the

community

A community is a social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant characteristic, such as place, set of norms, culture, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given g ...

's traditions rather than as a consequence of seeking a complete and deliberate break with the past.

Leadership

Leadership, is defined as the ability of an individual, group, or organization to "", influence, or guide other individuals, teams, or organizations.

"Leadership" is a contested term. Specialist literature debates various viewpoints on the co ...

,

authority

Authority is commonly understood as the legitimate power of a person or group of other people.

In a civil state, ''authority'' may be practiced by legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government,''The New Fontana Dictionary of M ...

, and

hierarchy

A hierarchy (from Ancient Greek, Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy ...

are seen as natural to humans. Traditionalism, in the forms of

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was a political ideology advocating the restoration of the senior line of the House of Stuart to the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British throne. When James II of England chose exile after the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, ...

, the

Counter-Enlightenment

The Counter-Enlightenment refers to a loose collection of intellectual stances that arose during the European Enlightenment in opposition to its mainstream attitudes and ideals. The Counter-Enlightenment is generally seen to have continued from ...

and early

Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

, arose in Europe during the 18th century as a backlash against

the Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empirici ...

, as well as the

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

and

French Revolutions. More recent forms have included early

German Romanticism

German Romanticism () was the dominant intellectual movement of German-speaking countries in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, influencing philosophy, aesthetics, literature, and criticism. Compared to English Romanticism, the German vari ...

,

Carlism

Carlism (; ; ; ) is a Traditionalism (Spain), Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty, one descended from Infante Carlos María Isidro of Spain, Don Carlos, ...

, and the

Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival () was the late-nineteenth-century national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including folklore, mythology, sports, music, arts, etc.). Irish had diminished as a sp ...

. Traditionalist conservatism began to establish itself as an intellectual and political force in the mid-20th century.

Key principles

Religious faith and natural law

A number of traditionalist conservatives embrace

high church

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, Christian liturgy, liturgy, and Christian theology, theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, ndsacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although ...

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

(e.g.,

T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist and playwright.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biography''. New York: Oxford University ...

, an

Anglo-Catholic

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholicism, Catholic heritage (especially pre-English Reformation, Reformation roots) and identity of the Church of England and various churches within Anglicanism. Anglo-Ca ...

;

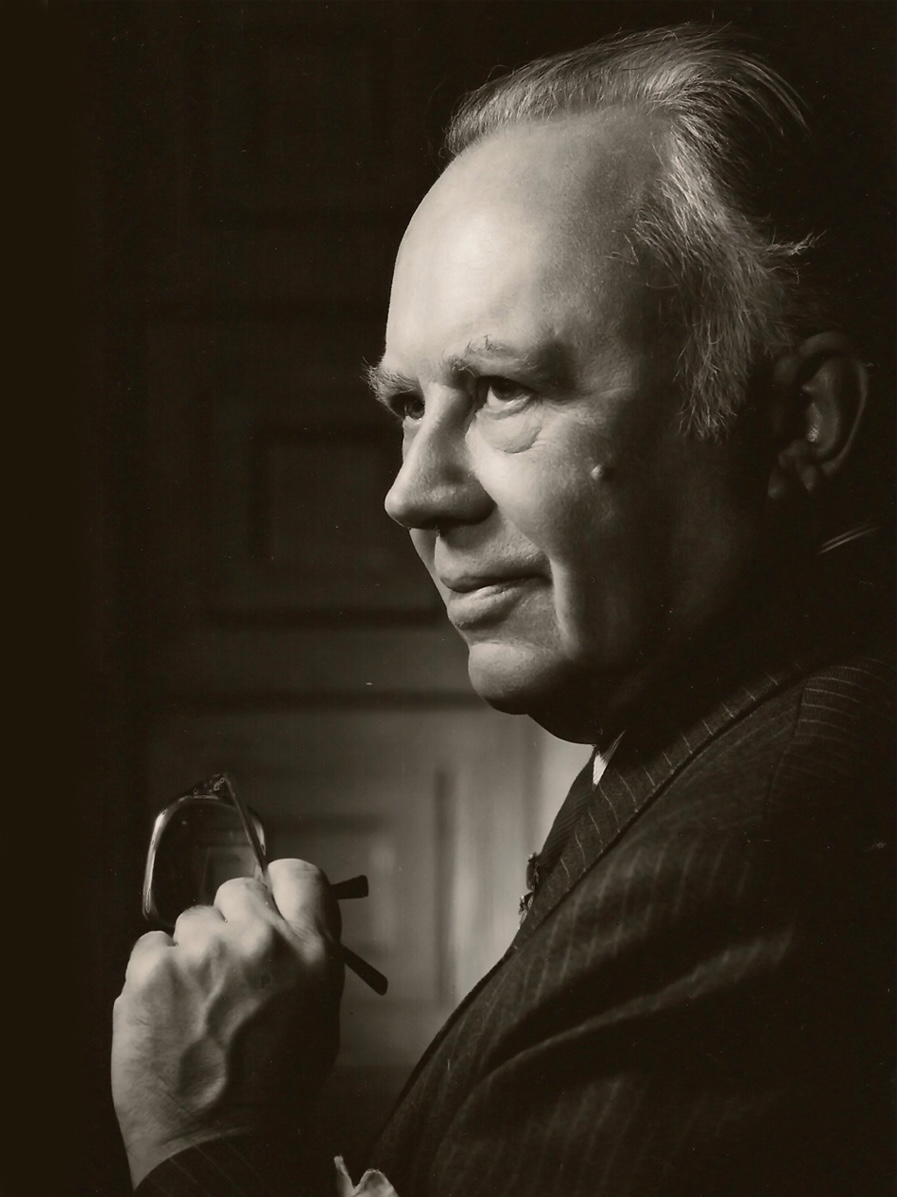

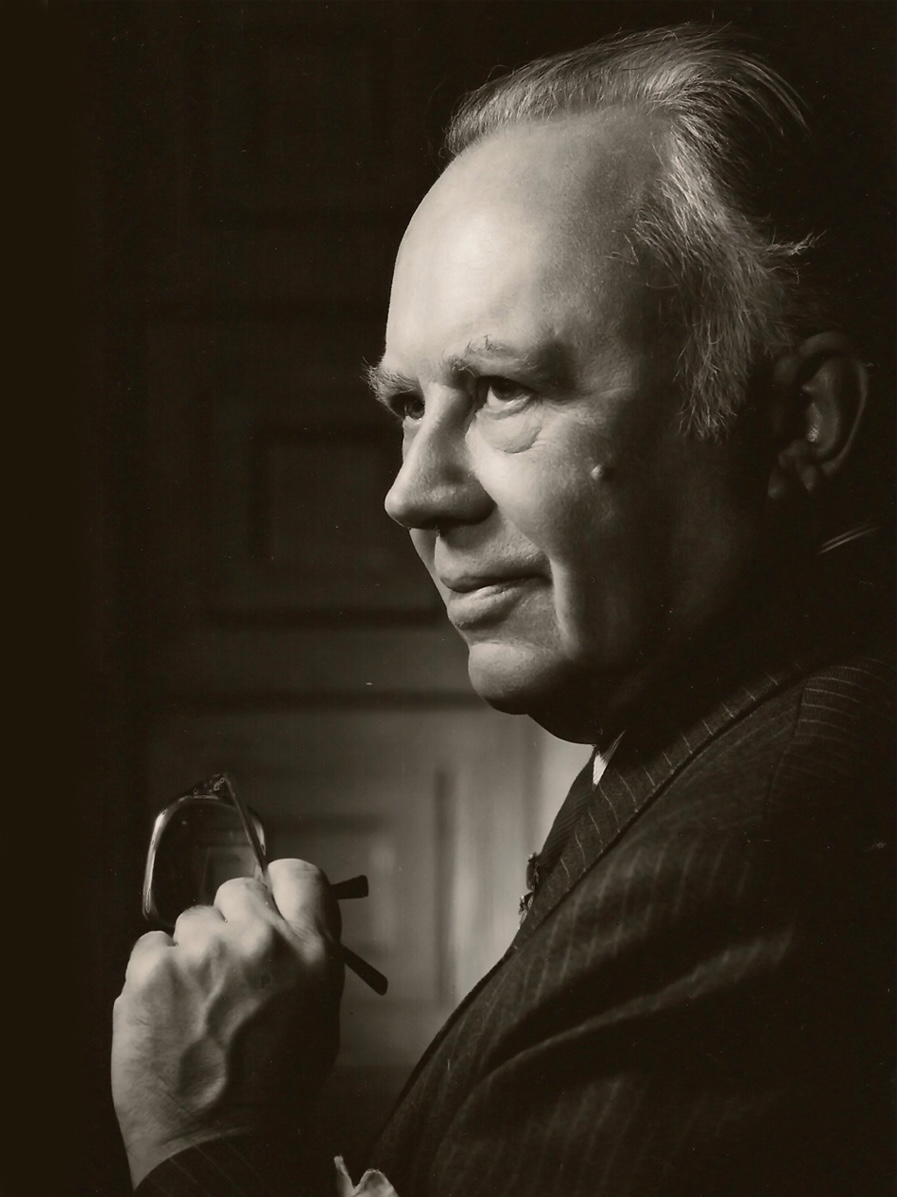

Russell Kirk

Russell Amos Kirk (October 19, 1918 – April 29, 1994) was an American political philosopher, moralist, historian, social critic, literary critic, author, and novelist who influenced 20th century American conservatism. In 1953, he authored '' T ...

, a Roman Catholic;

Rod Dreher

Ray Oliver Dreher Jr. (born February 14, 1967), known as Rod Dreher, is an American conservative writer and editor living in Hungary. He was a columnist with ''The American Conservative'' for 12 years, ending in March 2023, and remains an edito ...

, an

Eastern Orthodox Christian

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

). Another traditionalist who has stated his faith tradition publicly is

Caleb Stegall, an

evangelical Protestant

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of the Christian ...

. A number of conservative mainline Protestants are also traditionalists, such as

Peter Hitchens

Peter Jonathan Hitchens (born 1951) is an English Conservatism in the United Kingdom, conservative author, broadcaster, journalist, and commentator. He writes for ''The Mail on Sunday'' and was a Foreign correspondent (journalism), foreign cor ...

and

Roger Scruton

Sir Roger Vernon Scruton, (; 27 February 194412 January 2020) was an English philosopher, writer, and social critic who specialised in aesthetics and political philosophy, particularly in the furtherance of Conservatism in the United Kingdom, c ...

, and some traditionalists are Jewish, such as the late

Will Herberg

William Herberg (June 30, 1901 – March 26, 1977) was an American writer, intellectual, and scholar. A communist political activist during his early years, Herberg gained wider public recognition as a social philosopher and sociologist of relig ...

,

Irving Louis Horowitz

Irving Louis Horowitz (September 25, 1929 – March 21, 2012) was an American sociologist, author, and college professor who wrote and lectured extensively in his field. He proposed a quantitative index for measuring a country's quality of life, a ...

,

Mordecai Roshwald

Mordecai Marceli Roshwald (May 26, 1921 – March 19, 2015) was an American academic and writer. Born in Drohobycz, Second Polish Republic (now Ukraine) to Jewish parents, Roshwald later made aliyah to the State of Israel. His most famous work ...

,

Paul Gottfried

Paul Edward Gottfried (born November 21, 1941) is an American paleoconservative political philosopher, historian, and writer. He is a former Professor of Humanities at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania. He is editor-in-chief of the paleocon ...

and

Eva Brann

Eva T. H. Brann (January 1, 1929 – October 28, 2024) was an American academician, dean and the longest-serving tutor at St. John's College, Annapolis. She was a 2005 recipient of the National Humanities Medal.

Life and career

Brann was born to ...

.

Natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

is championed by

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

in the ''

Summa Theologiae

The ''Summa Theologiae'' or ''Summa Theologica'' (), often referred to simply as the ''Summa'', is the best-known work of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), a scholastic theologian and Doctor of the Church. It is a compendium of all of the main the ...

.'' There, he affirms the principle of

noncontradiction ("the same thing cannot be affirmed and denied at the same time") as being the first principle of theoretical reason, and ("good is to be done and pursued and evil avoided") as the first principle of practical reason, or that which precedes and determines one's actions. The account of

Medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

Christian philosophy

Christian philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Christians, or in relation to the religion of Christianity.

Christian philosophy emerged with the aim of reconciling science and faith, starting from natural rational explanations wit ...

is the appreciation of the concept of the ''

summum bonum

''Summum bonum'' is a Latin expression meaning the highest or ultimate good, which was introduced by the Roman philosopher Cicero to denote the fundamental principle on which some system of ethics is based—that is, the aim of actions, which, ...

'' or "highest good". It is only through the silent

contemplation

In a religious context, the practice of contemplation seeks a direct awareness of the Divinity, divine which Transcendence (religion), transcends the intellect, often in accordance with religious practices such as meditation or contemplative pr ...

that someone is able to achieve the idea of the

good

In most contexts, the concept of good denotes the conduct that should be preferred when posed with a choice between possible actions. Good is generally considered to be the opposite of evil. The specific meaning and etymology of the term and its ...

. The rest of natural law was first developed somewhat in

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's work, also was referenced and affirmed in the works by

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

, and it has been developed by the Christian

Albert the Great

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

. This is not meant to imply that traditionalist conservatives must be Thomists and embrace a robustly Thomistic natural law theory. Individuals who embrace non-Thomistic understandings of natural law rooted in, e.g., non-Aristotelian accounts affirmed in segments of Greco-Roman, patristic, medieval, and Reformation thought, can identify with traditionalist conservatism.

Tradition and custom

Traditionalists think that

tradition

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common e ...

and

custom

Custom, customary, or consuetudinary may refer to:

Traditions, laws, and religion

* Convention (norm), a set of agreed, stipulated or generally accepted rules, norms, standards or criteria, often taking the form of a custom

* Mores, what is wid ...

should guide man and his worldview, as their names imply. Each generation inherits its ancestors' experience and culture, which man is able to transmit down to his offspring through custom and precedent.

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

, noted that "the individual is foolish, but the species is wise." Furthermore, according to

John Kekes

John Kekes (; born 22 November 1936) is Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the University at Albany, SUNY.

Education

Kekes received his Ph.D. in philosophy from the Australian National University.

Work

Kekes is the author of a number of books on ...

, "tradition represents for conservatives a continuum enmeshing the individual and social, and is immune to reasoned critique." Traditional conservatism typically prefers

practical reason

In philosophy, practical reason is the use of reason to decide how to act. It contrasts with theoretical reason, often called speculative reason, the use of reason to decide what to believe. For example, agents use practical reason to decide whet ...

instead of

theoretical reason

The modern division of philosophy into theoretical philosophy and practical philosophyImmanuel Kant, ''Lectures on Ethics'', Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 41 ("On Universal Practical Philosophy"). Original text: Immanuel Kant, ''Kant’s Ge ...

.

Conservatism, it has been argued, is based on living tradition rather than abstract political thinking. Within conservatism, political journalist

Edmund Fawcett

Edmund Fawcett is a British political journalist and author.

Family

Fawcett is the son of the human rights lawyer and international law professor James Fawcett, brother of the artist Charlotte Johnson Wahl, and maternal uncle of Prime Minister ...

argues the existence of two strains of conservative thought, a flexible conservatism associated with

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

(which allows for limited reform), and an inflexible conservatism associated with

Joseph de Maistre

Joseph Marie, comte de Maistre (1 April 1753 – 26 February 1821) was a Savoyard philosopher, writer, lawyer, diplomat, and magistrate. One of the forefathers of conservatism, Maistre advocated social hierarchy and monarchy in the period immedi ...

(which is more reactionary).

Within flexible conservatism, some commentators may break it down further, contrasting the "pragmatic conservatism" which is still quite skeptical of abstract theoretical reason, vs. the "rational conservatism" which does not have skepticism of said reason, and simply favors some sort of hierarchy as sufficient.

Hierarchy, organicism, and authority

Traditionalist conservatives believe that human society is essentially

hierarchical

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an importan ...

(i.e., it always involves various interdependent inequalities, degrees, and classes) and that political structures that recognize this fact prove the most just, thriving, and generally beneficial. Hierarchy allows for the preservation of the whole community simultaneously, instead of protecting one part at the expense of the others.

Organicism

Organicism is the philosophical position that states that the universe and its various parts (including human societies) ought to be considered alive and naturally ordered, much like a living organism.Gilbert, S. F., and S. Sarkar. 2000. "Emb ...

also characterizes conservative thought. Edmund Burke notably viewed society from an organicist standpoint, as opposed to a more mechanistic view developed by liberal thinkers. Two concepts play a role in organicism in conservative thought:

* The internal elements of the organic society cannot be randomly reconfigured (similar to a living creature).

* The organic society is based upon natural needs and instincts, rather than that of a new ideological blueprint conceived by political theorists.

Traditional authority

Traditional authority is a form of leadership in which the authority of an organization or a regime is largely tied to tradition or custom. Reasons for the given state of affairs include belief that tradition is inherently valuable and a more g ...

is a common tenet of conservatism, albeit expressed in different forms.

Alexandre Kojève

Alexandre Kojève (born Aleksandr Vladimirovich Kozhevnikov; 28 April 1902 – 4 June 1968) was a Russian-born French philosopher and international civil service, civil servant whose philosophical seminars had some influence on 20th-century Frenc ...

distinguished between two forms of traditional authority: the father (fathers, priests, monarchs) and the master (aristocrats, military commanders). Obedience to said authority, whether familial or religious, continues to be a central tenet of conservatism to this day.

Integralism and divine law

Integralism

In politics, integralism, integrationism or integrism () is an interpretation of Catholic social teaching that argues the principle that the Catholic faith should be the basis of public law and public policy within civil society, wherever the ...

, typically a Catholic idea but also a broader religious one, asserts that faith and religious principles ought to be the basis for public law and policy when possible. The goal of such a system is to integrate religious authority with political power. While integralist principles have been sporadically associated with traditionalism, it was largely popularized by the works of

Joseph de Maistre

Joseph Marie, comte de Maistre (1 April 1753 – 26 February 1821) was a Savoyard philosopher, writer, lawyer, diplomat, and magistrate. One of the forefathers of conservatism, Maistre advocated social hierarchy and monarchy in the period immedi ...

.

Agrarianism

The countryside, as well as the values associated with it, are greatly valued (sometimes even being romanticized as in pastoral poetry).

Agrarian ideals (such as conserving small family farms, open land, natural resource conservation, and land stewardship) are important to certain traditionalists' conception of rural life.

Louis de Bonald

Louis Gabriel Ambroise, Vicomte de Bonald (; 2 October 1754 – 23 November 1840) was a French counter-revolutionary philosopher and politician. He is mainly remembered for developing a theoretical framework from which French sociology would eme ...

wrote a short piece on a comparison of the agriculturalism to industrialism.

Family structure

The importance of proper family structures is a common value expressed in conservatism. The concept of traditional morality is often coalesced with

familialism

Familialism or familism is a philosophy that puts priority to family. The term ''familialism'' has been specifically used for advocating a welfare system wherein it is presumed that families will take responsibility for the care of their memb ...

and

family values

Family values, sometimes referred to as familial values, are traditional or cultural values that pertain to the family's structure, function, roles, beliefs, attitudes, and ideals. Additionally, the concept of family values may be understood ...

, being viewed as the bedrock of society within traditionalist thought. Louis de Bonald wrote a piece on marital dissolution named "On Divorce" in 1802, outlining his opposition to the practice. Bonald stated that the broader human society was composed of three subunits (religious society - the church, domestic society - the family, public society - the state). He added that since the family made up one of these core categories, divorce would thereby represent an assault on the social order.

Morality

Morality, specifically traditional

moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

values, is a common area of importance within traditional conservatism, going back to Edmund Burke. Burke believed that a notion of sensibility was at the root of man's moral intuition. Furthermore, he theorized that divine moral law was both transcendent and immanent within humans.

Moralism

Moralism is a philosophy that arose in the 19th century that concerns itself with imbuing society with a certain set of morals, usually traditional behaviour, but also "justice, freedom, and equality". It has strongly affected North American and ...

, as a movement largely still exists within mainstream conservative circles with a focus on inherent or

deontological

In moral philosophy, deontological ethics or deontology (from Greek language, Greek: and ) is the normative ethics, normative ethical theory that the morality of an action should be based on whether that action itself is right or wrong under a ...

suppositions. While moral discussions exist across the political aisle, conservatism is distinct for including notions of purity-based reasoning. The type of morality attributed to Edmund Burke is referred to some as moral traditionalism.

Communitarianism

Communitarianism

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based on the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relation ...

is an ideology that broadly prioritizes the importance of the community over the individual's freedoms.

Joseph de Maistre

Joseph Marie, comte de Maistre (1 April 1753 – 26 February 1821) was a Savoyard philosopher, writer, lawyer, diplomat, and magistrate. One of the forefathers of conservatism, Maistre advocated social hierarchy and monarchy in the period immedi ...

was notably against individualism, and blamed Rousseau's individualism on the destructive nature of the French revolution. Some may argue that the communitarian ethic has considerable overlap with the conservative movement, although they remain distinct. While communitarians may draw upon similar elements of moral infrastructure to make their arguments, the communitarian opposition to liberalism is still more limited than that of conservatives. Furthermore, the communitarian prescription for society is more limited in scope than that of

social conservatives

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and a variety of conservatism which places emphasis on traditional social structures over social pluralism. Social conservatives organize in favor of duty, traditional values and social instit ...

. The term is typically used in two different senses; philosophical communitarianism which rejects liberal precepts and atomistic theory, vs. ideological communitarianism which is a syncretistic belief that holds in priority the positive right to social services for members of said community. Communitarianism may overlap with

stewardship

Stewardship is a practice committed to ethical value that embodies the responsible planning and management of resources. The concepts of stewardship can be applied to the environment and nature, economics, health, places, property, information ...

, in an environmental sense as well.

Social order

Social order

The term social order can be used in two senses: In the first sense, it refers to a particular system of social structures and institutions. Examples are the ancient, the feudal, and the capitalist social order. In the second sense, social orde ...

is a common tenet of conservatism, namely the maintenance of

social ties

In social network analysis and mathematical sociology, interpersonal ties are defined as information-carrying connections between people. Interpersonal ties, generally, come in three varieties: ''strong'', ''weak'' or ''absent''. Weak social t ...

, whether the family or the law. The concept may also tie into

social cohesion

Group cohesiveness, also called group cohesion, social harmony or social cohesion, is the degree or strength of bonds linking members of a social group to one another and to the group as a whole. Although cohesion is a multi-faceted process, it ...

. Joseph de Maistre defended the necessity of the public executioner as encouraging stability. In the ''

St Petersburg Dialogues

''St Petersburg Dialogues: or Conversations on the Temporal Government of Providence'' () is an 1821 book by the Savoyard diplomat and philosopher Joseph de Maistre.

Summary

In a series of dialogues, three characters, called the Count, the Sena ...

'', he wrote: "all power, all subordination rests on the executioner: he is the horror and the bond of human association. Remove this incomprehensible agent from the world, and the very moment order gives way to chaos, thrones topple, and society disappears."

The concept of social order is not exclusive to conservatism, although it tends to be fairly prevalent within it. Both Jean Jacques Rousseau and Joseph de Maistre believed in social order, the difference was that Maistre preferred the status quo, indivisibility of law and rule, and the mesh of Church with State. Meanwhile, Rousseau preferred social contract and the ability to withdraw from such (and pick the ruler) as well as a separation of Church and state. Furthermore, Rousseau went on the criticize the "cult of the state" as well.

Classicism and high culture

Traditionalists defend classical

Western civilization

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompasses the social no ...

and value an education informed by the sifting of texts starting in the

Roman World

The culture of ancient Rome existed throughout the almost 1,200-year history of the civilization of Ancient Rome. The term refers to the culture of the Roman Republic, later the Roman Empire, which at its peak covered an area from present-day L ...

and refined under

Medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

and

Renaissance humanism. Similarly, traditionalist conservatives are

Classicist

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

s who revere

high culture

In a society, high culture encompasses culture, cultural objects of Objet d'art, aesthetic value that a society collectively esteems as exemplary works of art, as well as the literature, music, history, and philosophy a society considers represen ...

in all of its manifestations (e.g.

literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

,

Classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be #Relationship to other music traditions, distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical mu ...

,

architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

,

art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

, and

theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a Stage (theatre), stage. The performe ...

).

Localism

Traditionalists consider

localism

Localism may refer to:

* Fiscal localism, ideology of keeping money in a local economy

* Local purchasing, a movement to buy local products and services

* Conflict in surf culture, between local residents and visitors for access to beaches with lar ...

a core principle, described as a sense of devotion to one's homeland, in contrast to nationalists, who value the role of the state or nation over the

local

Local may refer to:

Geography and transportation

* Local (train), a train serving local traffic demand

* Local, Missouri, a community in the United States

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Local'' (comics), a limited series comic book by Bria ...

community. Traditionalist conservatives believe that allegiance to family, local community, and region is often more important than political commitments. Traditionalists also prioritize community closeness above nationalist state interest, preferring the

civil society

Civil society can be understood as the "third sector" of society, distinct from government and business, and including the family and the private sphere.[nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...]

can easily be radicalized and lead to

jingoism

Jingoism is nationalism in the form of aggressive and proactive foreign policy, such as a country's advocacy for the use of threats or actual force, as opposed to peaceful relations, in efforts to safeguard what it perceives as its national inte ...

, which sees the state as apart from the local community and family structure rather than as a product of both.

An example of a traditionalist conservative approach to immigration may be seen in Bishop

John Joseph Frederick Otto Zardetti

John Joseph Frederick Otto Zardetti (January 24, 1847 – May 10, 1902) was a Swiss prelate of the Roman Catholic Church. He first served as the first bishop of the new Diocese of Saint Cloud in Minnesota in the United States from 1889 to 189 ...

's September 21, 1892 "Sermon on the Mother and the Bride", which was a defence of Roman Catholic

German-American

German Americans (, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry.

According to the United States Census Bureau's figures from 2022, German Americans make up roughly 41 million people in the US, which is approximately 12% of the pop ...

s desire to preserve their faith, ancestral culture, and to continue speaking their

heritage language

A heritage language is a minority language (either immigrant or indigenous) learned by its speakers at home as children, and difficult to be fully developed because of insufficient input from the social environment. The speakers grow up with a ...

of the

German language in the United States

Over 50 million Americans claim German ancestry, which made them the largest single claimed ancestry group in the United States until 2020. Around 1.06 million people in the United States speak the German language at home. It is the second m ...

, against both the

English only movement

The English-only movement, also known as the Official English movement, is a political movement that advocates for the exclusive use of the English language in official United States government communication through the establishment of English ...

and accusations of being

Hyphenated Americans

In the United States, the term hyphenated American refers to the use of a hyphen (in some styles of writing) between the name of an ethnicity and the word in compound nouns, e.g., as in . Calling a person a "hyphenated American" was used as ...

.

History

British influences

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

, an Anglo-Irish

Whig statesman and philosopher whose political principles were rooted in moral natural law and the Western heritage, is one of the first expositors of traditionalist conservatism, although

Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

ism represented an even earlier, more primitive form of traditionalist conservatism. Burke believed in prescriptive rights, which he considered to be "God-given". He argued for what he called "

ordered liberty

Ordered liberty is a concept in political philosophy, where individual freedom is balanced with the necessity for maintaining social order.

The phrase "ordered liberty" originates from an opinion by Justice Benjamin Cardozo in ''Palko v. Connec ...

" (best reflected in the unwritten law of the British constitutional monarchy). He also fought for universal ideals that were supported by institutions such as the church, the family, and the state. He was a fierce critic of the principles behind the

French Revolution, and in 1790, his observations on its excesses and radicalism were collected in ''

Reflections on the Revolution in France

''Reflections on the Revolution in France'' is a political pamphlet written by the British statesman Edmund Burke and published in November 1790. It is fundamentally a contrast of the French Revolution to that time with the unwritten Constitutio ...

''. In ''Reflections'', Burke called for the constitutional enactment of specific, concrete rights and warned that abstract rights could be easily abused to justify tyranny. American social critic and historian

Russell Kirk

Russell Amos Kirk (October 19, 1918 – April 29, 1994) was an American political philosopher, moralist, historian, social critic, literary critic, author, and novelist who influenced 20th century American conservatism. In 1953, he authored '' T ...

wrote: "The ''Reflections'' burns with all the wrath and anguish of a prophet who saw the traditions of Christendom and the fabric of civil society dissolving before his eyes."

Burke's influence was felt by later intellectuals and authors in both Britain and continental Europe. The English Romantic poets

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ( ; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets with his friend William Wordsworth ...

,

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poetry, Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romanticism, Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Balla ...

and

Robert Southey

Robert Southey (; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic poetry, Romantic school, and Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth an ...

, as well as Scottish Romantic author

Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

, and the counter-revolutionary writers

François-René de Chateaubriand

François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand (4 September 1768 – 4 July 1848) was a French writer, politician, diplomat and historian who influenced French literature of the nineteenth century. Descended from an old aristocratic family from Bri ...

,

Louis de Bonald

Louis Gabriel Ambroise, Vicomte de Bonald (; 2 October 1754 – 23 November 1840) was a French counter-revolutionary philosopher and politician. He is mainly remembered for developing a theoretical framework from which French sociology would eme ...

and

Joseph de Maistre

Joseph Marie, comte de Maistre (1 April 1753 – 26 February 1821) was a Savoyard philosopher, writer, lawyer, diplomat, and magistrate. One of the forefathers of conservatism, Maistre advocated social hierarchy and monarchy in the period immedi ...

were all affected by his ideas. Burke's legacy was best represented in the United States by the

Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a conservativeMultiple sources:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* and nationalist American political party and the first political party in the United States. It dominated the national government under Alexander Hamilton from 17 ...

and its leaders, such as President

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

and Secretary of the Treasury

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

.

French influences

Joseph de Maistre

Joseph Marie, comte de Maistre (1 April 1753 – 26 February 1821) was a Savoyard philosopher, writer, lawyer, diplomat, and magistrate. One of the forefathers of conservatism, Maistre advocated social hierarchy and monarchy in the period immedi ...

, a French lawyer, was another founder of conservatism. He was an

ultramontane

Ultramontanism is a clerical political conception within the Catholic Church that places strong emphasis on the prerogatives and powers of the Pope. It contrasts with Gallicanism, the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by ...

Catholic, and thoroughly rejected progressivism and rationalism. In 1796, he published a political pamphlet entitled, ''

Considerations on France'', that mirrored Burke's ''

Reflections''. Maistre viewed the French revolution as "evil schism", and a movement premised on the "sentiment of hatred". After the demise of Napoleon, Maistre returned to France to meet with pro-royalist circles. In 1819, Maistre published a piece called ''Du Pape'' which outlined the Pope as the key sovereign, unto which authority derives from.

Critics of material progress

Three

cultural conservatives and

skeptics of material development,

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ( ; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets with his friend William Wordsworth ...

,

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

, and

John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English Catholic theologian, academic, philosopher, historian, writer, and poet. He was previously an Anglican priest and after his conversion became a cardinal. He was an ...

, were staunch supporters of Burke's classical conservatism.

According to conservative scholar Peter Viereck, Coleridge and his colleague and fellow poet

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poetry, Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romanticism, Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Balla ...

began as followers of the

French Revolution and the radical utopianism it engendered. Their collection of poems, ''Lyrical Ballads'', published in 1798, however, rejected the

Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

notion of reason triumphing over faith and tradition. Later works by Coleridge, such as ''Lay Sermons'' (1816), ''Biographia Literaria'' (1817) and ''Aids to Reflection'' (1825), defended traditional conservative positions on hierarchy and organic society, criticism of materialism and the merchant class, and the need for "inner growth" that is rooted in a traditional and religious culture. Coleridge was a strong supporter of social institutions and an outspoken opponent of

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February Dual dating, 1747/8 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S.

5 (five) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number, and cardinal number, following 4 and preceding 6, and is a prime number.

Humans, and many other animals, have 5 digits on their limbs.

Mathematics

5 is a Fermat pri ...

– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of mo ...

and his

utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the affected individuals. In other words, utilitarian ideas encourage actions that lead to the ...

theory.

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

, a writer, historian, and essayist, was an early traditionalist thinker, defending medieval ideals such as aristocracy, hierarchy, organic society, and class unity against communism and ''

laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

''

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

's "cash nexus." The "cash nexus," according to Carlyle, occurs when social interactions are reduced to economic gain. Carlyle, a lover of the poor, claimed that mobs, plutocrats, anarchists, communists, socialists, liberals, and others were threatening the fabric of British society by exploiting them and perpetuating class animosity. A devotee of Germanic culture and

Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

, Carlyle is best known for his works, ''

Sartor Resartus

''Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books'' is a novel by the Scottish people, Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle, first published as a serial in ''Fraser's Magazine'' in November 1833 ...

'' (1833–1834) and ''

Past and Present'' (1843).

The

Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a theological movement of high-church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the Un ...

, a religious movement aimed at restoring Anglicanism's Catholic nature, gave the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

a "catholic rebirth" in the mid-19th century. The

Tractarians

The Oxford Movement was a theological movement of high-church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the Un ...

(so named for the publication of their ''

Tracts for the Times

The Tracts for the Times were a series of 90 theological publications, varying in length from a few pages to book-length, produced by members of the English Oxford Movement, an Anglo-Catholic revival group, from 1833 to 1841. There were about a do ...

'') criticized

theological liberalism

Religious liberalism is a conception of religion (or of a particular religion) which emphasizes personal and group liberty and rationality. It is an attitude towards one's own religion (as opposed to criticism of religion from a secular position ...

while preserving "dogma, ritual, poetry,

ndtradition," led by

John Keble

John Keble (25 April 1792 – 29 March 1866) was an English Anglican priest and poet who was one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement. Keble College, Oxford, is named after him.

Early life

Keble was born on 25 April 1792 in Fairford, Glouces ...

,

Edward Pusey

Edward Bouverie Pusey (; 22 August 180016 September 1882) was an English Anglican cleric, for more than fifty years Regius Professor of Hebrew at the University of Oxford. He was one of the leading figures in the Oxford Movement, with interest ...

, and

John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English Catholic theologian, academic, philosopher, historian, writer, and poet. He was previously an Anglican priest and after his conversion became a cardinal. He was an ...

. Newman (who converted to Roman Catholicism in 1845 and was later made a Cardinal and a canonized saint) and the Tractarians, like Coleridge and Carlyle, were critical of material progress, or the idea that money, prosperity, and economic gain constituted the totality of human existence.

Cultural and artistic criticism

Culture and the arts were also important to British traditionalist conservatives, and two of the most prominent defenders of tradition in culture and the arts were

Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold (academic), Tom Arnold, literary professor, and Willi ...

and

John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English polymath a writer, lecturer, art historian, art critic, draughtsman and philanthropist of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, Critique of politic ...

.

A poet and cultural commentator,

Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold (academic), Tom Arnold, literary professor, and Willi ...

is most recognized for his poems and literary, social, and religious criticism. His book ''Culture and Anarchy'' (1869) criticized Victorian middle-class norms (Arnold referred to middle class tastes in literature as "

philistinism

In the fields of philosophy and of aesthetics, the term philistinism describes the attitudes, habits, and characteristics of a person who deprecates art, beauty, spirituality, and intellect.''Webster's New Twentieth Century Dictionary of the Eng ...

") and advocated a return to ancient literature. Arnold was likewise skeptical of the plutocratic grasping at socioeconomic issues that had been denounced by Coleridge, Carlyle, and the Oxford Movement. Arnold was a vehement critic of the Liberal Party and its Nonconformist base. He mocked Liberal efforts to disestablish the Anglican Church in Ireland, establish a Catholic university there, allow dissenters to be buried in Church of England cemeteries, demand temperance, and ignore the need to improve middle class members rather than impose their unreasonable beliefs on society. Education was essential, and by that, Arnold meant a close reading and attachment to the cultural classics, coupled with critical reflection. He feared anarchy—the fragmentation of life into isolated facts that is caused by dangerous educational panaceas that emerge from materialistic and utilitarian philosophies. He was appalled at the shamelessness of the sensationalistic new journalism of the sort he witnessed on his tour of the United States in 1888. He prophesied, "If one were searching for the best means to efface and kill in a whole nation the discipline of self-respect, the feeling for what is elevated, he could do no better than take the American newspapers."

One of the issues that traditionalist conservatives have often emphasized is that capitalism is just as suspect as the

classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited governmen ...

that gave birth to it. Cultural and artistic critic

John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English polymath a writer, lecturer, art historian, art critic, draughtsman and philanthropist of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, Critique of politic ...

, a medievalist who considered himself a "Christian communist" and cared much about standards in culture, the arts, and society, continued this tradition. The

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, according to Ruskin (and all 19th-century cultural conservatives), had caused dislocation, rootlessness, and vast urbanization of the poor. He wrote ''The Stones of Venice'' (1851–1853), a work of art criticism that attacked the Classical heritage while upholding Gothic art and architecture. ''The Seven Lamps of Architecture'' and ''Unto This Last'' (1860) were two of his other masterpieces.

One-nation conservatism

Burke, Coleridge, Carlyle, Newman, and other traditionalist conservatives' beliefs were distilled into former British Prime Minister

Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

's politics and ideology. When he was younger, Disraeli was an outspoken opponent of middle-class capitalism and the Manchester liberals' industrial policies (the Reform Bill and the Corn Laws). In order to ameliorate the suffering of the urban poor in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution, Disraeli proposed "

one-nation conservatism

One-nation conservatism, also known as one-nationism or Tory democracy, is a form of British political conservatism and a variant of paternalistic conservatism. It advocates the "preservation of established institutions and traditional pri ...

," in which a coalition of aristocrats and commoners would band together to counter the liberal middle class's influence. This new coalition would be a way to interact with disenfranchised people while also rooting them in old conservative principles. Disraeli's ideas (especially his critique of

utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the affected individuals. In other words, utilitarian ideas encourage actions that lead to the ...

) were popularized in the "Young England" movement and in books like ''Vindication of the English Constitution'' (1835), ''The Radical Tory'' (1837), and his "social novels," ''

Coningsby

Coningsby is a town and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in the East Lindsey Non-metropolitan district, district in Lincolnshire, England, it is situated on the A153 road, adjoining Tattershall on its western side, north west of Bost ...

'' (1844) and ''Sybil'' (1845). His one-nation conservatism was revived a few years later in

Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (13 February 1849 – 24 January 1895) was a British aristocrat and politician. Churchill was a Tory radical who coined the term "One-nation conservatism, Tory democracy". He participated in the creation ...

's Tory democracy and in the early 21st century in British philosopher

Phillip Blond

Phillip Blond (born 1 March 1966) is an English political philosopher, Anglican theologian, and director of the ResPublica think tank.

Early life

Born in Liverpool and educated at Pensby High School for Boys, Blond went on to study philosophy ...

's

Red Tory

A Red Tory is an adherent of a Centre-right politics, centre-right or Paternalistic conservatism, paternalistic-conservative political philosophy derived from the Tory tradition. It is most predominant in Canada; however, it is also found in the ...

thesis.

Distributism

In the early 20th century, traditionalist conservatism found its defenders through the efforts of

Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc ( ; ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a French-English writer, politician, and historian. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. His Catholic fait ...

,

G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English author, philosopher, Christian apologist, journalist and magazine editor, and literary and art critic.

Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brow ...

and other proponents of the socioeconomic system they advocated:

distributism

Distributism is an economic theory asserting that the world's productive assets should be widely owned rather than concentrated. Developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, distributism was based upon Catholic social teaching princi ...

. Originating in the papal encyclical ''

Rerum novarum

''Rerum novarum'', or ''Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor'', is an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on 15 May 1891. It is an open letter, passed to all Catholic patriarchs, primates, archbishops, and bishops, which addressed the condi ...

'', distributism employed the concept of

subsidiarity

Subsidiarity is a principle of social organization that holds that social and political issues should be dealt with at the most immediate or local level that is consistent with their resolution. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' defines subsid ...

as a "third way" solution to the twin evils of communism and capitalism. It favors local economies, small business, the agrarian way of life and craftsmen and artists. Otto von Bismarck implemented one of the first modern welfare systems in Germany during the 1880s. Traditional communities akin to those found in the Middle Ages were advocated in books like Belloc's ''The Servile State'' (1912), ''Economics for Helen'' (1924), and ''An Essay on the Restoration of Property'' (1936), and Chesterton's ''The Outline of Sanity'' (1926), while big business and big government were condemned. Distributist views were accepted in the United States by the journalist

Herbert Agar

Herbert Sebastian Agar (29 September 1897 – 24 November 1980) was an American journalist and historian, and an editor of the ''Louisville Courier-Journal''.

Early life and education

Herbert Sebastian Agar was born September 29, 1897, in New R ...

and Catholic activist

Dorothy Day

Dorothy Day, Oblate#Secular oblates, OblSB (November 8, 1897 – November 29, 1980) was an American journalist, social activist and Anarchism, anarchist who, after a bohemianism, bohemian youth, became a Catholic Church, Catholic without aba ...

as well as through the influence of the German-born British economist

E. F. Schumacher

Ernst Friedrich Schumacher (16 August 1911 – 4 September 1977) was a German-born British statistician and economist who is best known for his proposals for human-scale, decentralised and appropriate technologies.Biography on the inner dust ...

, and were comparable to

Wilhelm Roepke's work.

T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist and playwright.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biography''. New York: Oxford University ...

was a staunch supporter of Western culture and traditional Christianity. Eliot was a political reactionary who used literary modernism to achieve traditionalist goals. Following in the footsteps of

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

,

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ( ; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets with his friend William Wordsworth ...

,

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

,

John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English polymath a writer, lecturer, art historian, art critic, draughtsman and philanthropist of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as art, architecture, Critique of politic ...

,

G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English author, philosopher, Christian apologist, journalist and magazine editor, and literary and art critic.

Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brow ...

, and

Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc ( ; ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a French-English writer, politician, and historian. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. His Catholic fait ...

, he wrote ''After Strange Gods'' (1934), and ''Notes towards the Definition of Culture'' (1948). At Harvard University, where he was educated by

Irving Babbitt

Irving Babbitt (August 2, 1865 – July 15, 1933) was an American academic and literary critic, noted for his founding role in a movement that became known as the New Humanism, a significant influence on literary discussion and conservative tho ...

and

George Santayana

George Santayana (born Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás, December 16, 1863 – September 26, 1952) was a Spanish-American philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist. Born in Spain, Santayana was raised and educated in the Un ...

, Eliot was acquainted with

Allen Tate

John Orley Allen Tate (November 19, 1899 – February 9, 1979), known professionally as Allen Tate, was an American poet, essayist, social commentator, and poet laureate from 1943 to 1944. Among his best known works are the poems " Ode to th ...

and

Russell Kirk

Russell Amos Kirk (October 19, 1918 – April 29, 1994) was an American political philosopher, moralist, historian, social critic, literary critic, author, and novelist who influenced 20th century American conservatism. In 1953, he authored '' T ...

.

T. S. Eliot praised

Christopher Dawson

Christopher Henry Dawson (12 October 188925 May 1970) was an English Catholic historian, independent scholar, who wrote many books on cultural history and emphasized the necessity for Western culture to be in continuity with Christianity not ...

as the most potent intellectual influence in Britain, and he was a prominent player in 20th-century traditionalism. The belief that religion was at the center of all civilization, especially Western culture, was central to his work, and his books reflected this view, notably ''The Age of Gods'' (1928), ''Religion and Culture'' (1948), and ''Religion and the Rise of Western Culture'' (1950). Dawson, a contributor to Eliot's ''

Criterion

Criterion (: criteria) may refer to:

General

* Criterion, Oregon, a historic unincorporated community in the United States

* Criterion Place, a proposed skyscraper in West Yorkshire, England

* Criterion Restaurant, in London, England

* Criteri ...

'', believed that religion and culture were crucial to rebuilding the West after World War II in the aftermath of

fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

and the advent of

communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

.

In the United Kingdom

Philosophers

Roger Scruton, a British philosopher, was a self-described traditionalist and conservative. One of his most well-known books, ''The Meaning of Conservatism'' (1980), is on foreign policy, animal rights, arts and culture, and philosophy. Scruton was a member of the

American Enterprise Institute

The American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, known simply as the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), is a center-right think tank based in Washington, D.C., that researches government, politics, economics, and social welfare ...

, the

Institute for the Psychological Sciences

The Institute for the Psychological Sciences (IPS) is a graduate school of psychology and an integral part of Divine Mercy University (DMU) in Loudoun County, Virginia, Sterling, Virginia. The institute was founded in 1999 with the mission of bas ...

, the

Trinity Forum

The Trinity Forum (TTF) is an American faith-based non-profit Christian organization founded in 1991 by author and social critic Os Guinness and American businessman and philanthropist Alonzo L. McDonald.

The current president of the Trinity ...

, and the

Center for European Renewal

The Center for European Renewal (CER) is a Pan-European identity, pan-European Conservatism, conservative organization based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The CER was founded in the summer of 2007 by a group of mainly European conservatives. The ...

. ''

Modern Age

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500 ...

'', ''

National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief is Rich L ...

'', ''

The American Spectator

''The American Spectator'' is a conservative American magazine covering news and politics, edited by R. Emmett Tyrrell Jr. and published by the non-profit American Spectator Foundation. It was founded in 1967 by Tyrrell (the current editor-in ...

'', ''

The New Criterion

''The New Criterion'' is a New York–based monthly literary magazine and journal of artistic and cultural criticism, edited by Roger Kimball (editor and publisher) and James Panero (executive editor). It has sections for criticism of poetry ...

'', and ''

City Journal

''City Journal'' is a public policy magazine and website, published by the conservative think tank Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, that covers a range of topics on urban affairs, such as policing, education, housing, and other issues. ...

'' were among the many publications for which he wrote.

Phillip Blond

Phillip Blond (born 1 March 1966) is an English political philosopher, Anglican theologian, and director of the ResPublica think tank.

Early life

Born in Liverpool and educated at Pensby High School for Boys, Blond went on to study philosophy ...

, a British philosopher, has recently gained notoriety as a proponent of traditionalist philosophy, specifically progressive conservatism, or

Red Tory

A Red Tory is an adherent of a Centre-right politics, centre-right or Paternalistic conservatism, paternalistic-conservative political philosophy derived from the Tory tradition. It is most predominant in Canada; however, it is also found in the ...

ism. Blond believes that Red Toryism would rejuvenate

British conservatism and society by combining civic

communitarianism

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based on the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relation ...

,

localism

Localism may refer to:

* Fiscal localism, ideology of keeping money in a local economy

* Local purchasing, a movement to buy local products and services

* Conflict in surf culture, between local residents and visitors for access to beaches with lar ...

, and traditional values. He has formed a think tank,

ResPublica

ResPublica (from the Latin phrase, ''res publica'', meaning 'public thing' or 'commonwealth') is a British independent public policy think tank, founded in 2009, by Phillip Blond. It describes itself as a multi-disciplinary, non-party politi ...

.

Publications and political organizations

The oldest traditionalist publication in the United Kingdom is ''

The Salisbury Review

''The Salisbury Review'' is a quarterly United Kingdom, British "magazine of Conservatism, conservative thought". It was founded in 1982 by the Salisbury Group, who sought to articulate and further traditional intellectual conservative ideas.

The ...

'', which was founded by British philosopher

Roger Scruton

Sir Roger Vernon Scruton, (; 27 February 194412 January 2020) was an English philosopher, writer, and social critic who specialised in aesthetics and political philosophy, particularly in the furtherance of Conservatism in the United Kingdom, c ...

. The ''Salisbury Review''s current managing editor is Merrie Cave.

A group of traditionalist MPs known as the

Cornerstone Group

The Cornerstone Group is a High Tory or traditional conservative political organisation within the British Conservative Party. It comprises Members of Parliament with a traditionalist outlook and was founded in 2005. The Group's president is ...

was created in 2005 within the

British Conservative Party

The Conservative and Unionist Party, commonly the Conservative Party and colloquially known as the Tories, is one of the two main political parties in the United Kingdom, along with the Labour Party. The party sits on the centre-right to right- ...

. The Cornerstone Group represents "faith, flag, and family" and stands for traditional values.

Edward Leigh

Sir Edward Julian Egerton Leigh (born 20 July 1950) is a British Conservative Party politician who has been serving as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Gainsborough, previously Gainsborough and Horncastle, since 1983. Parliament's longes ...

and

John Henry Hayes are two notable members.

In Europe

The