thylacocephala on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Thylacocephala (from the Greek or ', meaning " pouch", and or ' meaning "The implications of a Silurian and other thylacocephalan crustaceans for the functional morphology and systematic affinities of the group

/ref> Beyond this, there remains much uncertainty concerning fundamental aspects of the thylacocephalan anatomy, mode of life, and relationship to the Crustacea, with whom they have always been cautiously aligned.

Researchers agree the Thylacocephala represent a class. Some efforts have been made at further classification: Schram split currently known taxa into two orders:

*Concavicarida Briggs & Rolfe, 1983 which possesses:

**A large, well developed optic notch

**A discrete compound eye

** A fused rostrum

** 8 to 16 homologous well-demarcated trunk segments diminishing in height anteriorly and posteriorly

** Order includes '' Ainiktozoon'' (

Researchers agree the Thylacocephala represent a class. Some efforts have been made at further classification: Schram split currently known taxa into two orders:

*Concavicarida Briggs & Rolfe, 1983 which possesses:

**A large, well developed optic notch

**A discrete compound eye

** A fused rostrum

** 8 to 16 homologous well-demarcated trunk segments diminishing in height anteriorly and posteriorly

** Order includes '' Ainiktozoon'' (

Class: Thylacocephala

* '' Ainiktozoon''

* '' Ankitokazocaris''

* '' Eodollocaris''

* '' Falcatacaris''

* '' Ligulacaris''

* '' Paraostenia''

* '' Polzia''

* '' Rugocaris''

* '' Silesicaris''

*'' Stoppanicaris''

* '' Thylacares''

* '' Victoriacaris''

* Order Concavicarida

** Family Austriocarididae

*** '' Austriocaris''

*** '' Yangzicaris''

** Family Clausocarididae

*** '' Clausocaris''

*** '' Convexicaris''

** Family Concavicarididae

*** '' Concavicaris''

*** '' Harrycaris''

*** '' Paraconcavicaris''

** Family: Microcarididae

*** '' Atropicaris''

*** '' Ferrecaris''

*** '' Keelicaris''

*** '' Microcaris''

*** '' Thylacocephalus''

** Family: Protozoeidae

*** '' Globulocaris''

*** '' Hamaticaris''

*** '' Protozoea''

*** '' Pseuderichthus''

* Order Conchyliocarida

** Family: Dollocarididae

*** '' Dollocaris''

*** '' Mayrocaris''

*** '' Paradollocaris''

*** '' Thylacocaris ''

** Family: Ostenocarididae

*** '' Kilianocaris''

*** '' Ostenocaris''

Class: Thylacocephala

* '' Ainiktozoon''

* '' Ankitokazocaris''

* '' Eodollocaris''

* '' Falcatacaris''

* '' Ligulacaris''

* '' Paraostenia''

* '' Polzia''

* '' Rugocaris''

* '' Silesicaris''

*'' Stoppanicaris''

* '' Thylacares''

* '' Victoriacaris''

* Order Concavicarida

** Family Austriocarididae

*** '' Austriocaris''

*** '' Yangzicaris''

** Family Clausocarididae

*** '' Clausocaris''

*** '' Convexicaris''

** Family Concavicarididae

*** '' Concavicaris''

*** '' Harrycaris''

*** '' Paraconcavicaris''

** Family: Microcarididae

*** '' Atropicaris''

*** '' Ferrecaris''

*** '' Keelicaris''

*** '' Microcaris''

*** '' Thylacocephalus''

** Family: Protozoeidae

*** '' Globulocaris''

*** '' Hamaticaris''

*** '' Protozoea''

*** '' Pseuderichthus''

* Order Conchyliocarida

** Family: Dollocarididae

*** '' Dollocaris''

*** '' Mayrocaris''

*** '' Paradollocaris''

*** '' Thylacocaris ''

** Family: Ostenocarididae

*** '' Kilianocaris''

*** '' Ostenocaris''

Based on Vannier, modified after Schram:

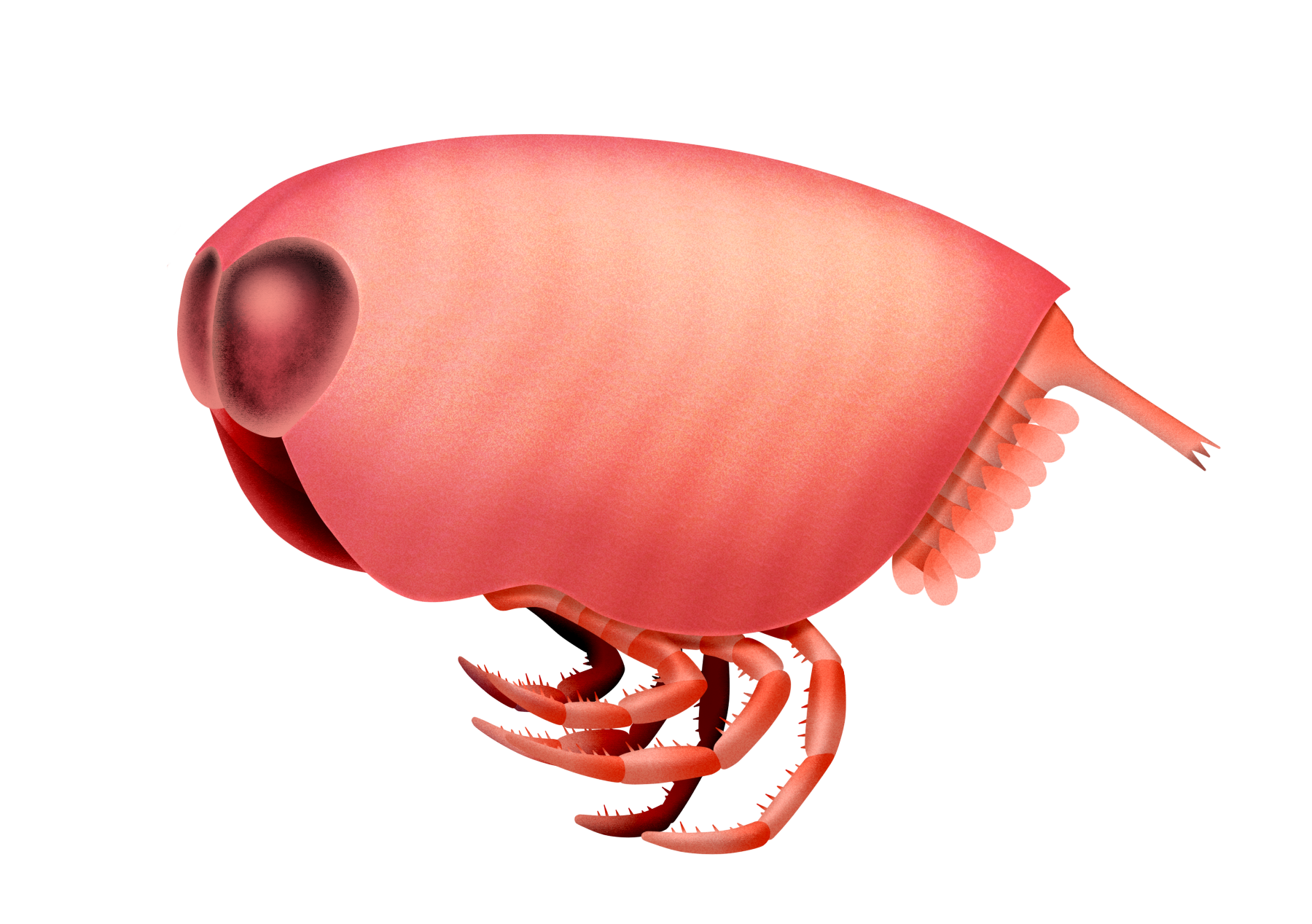

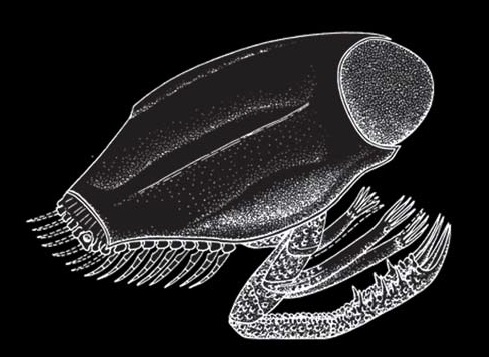

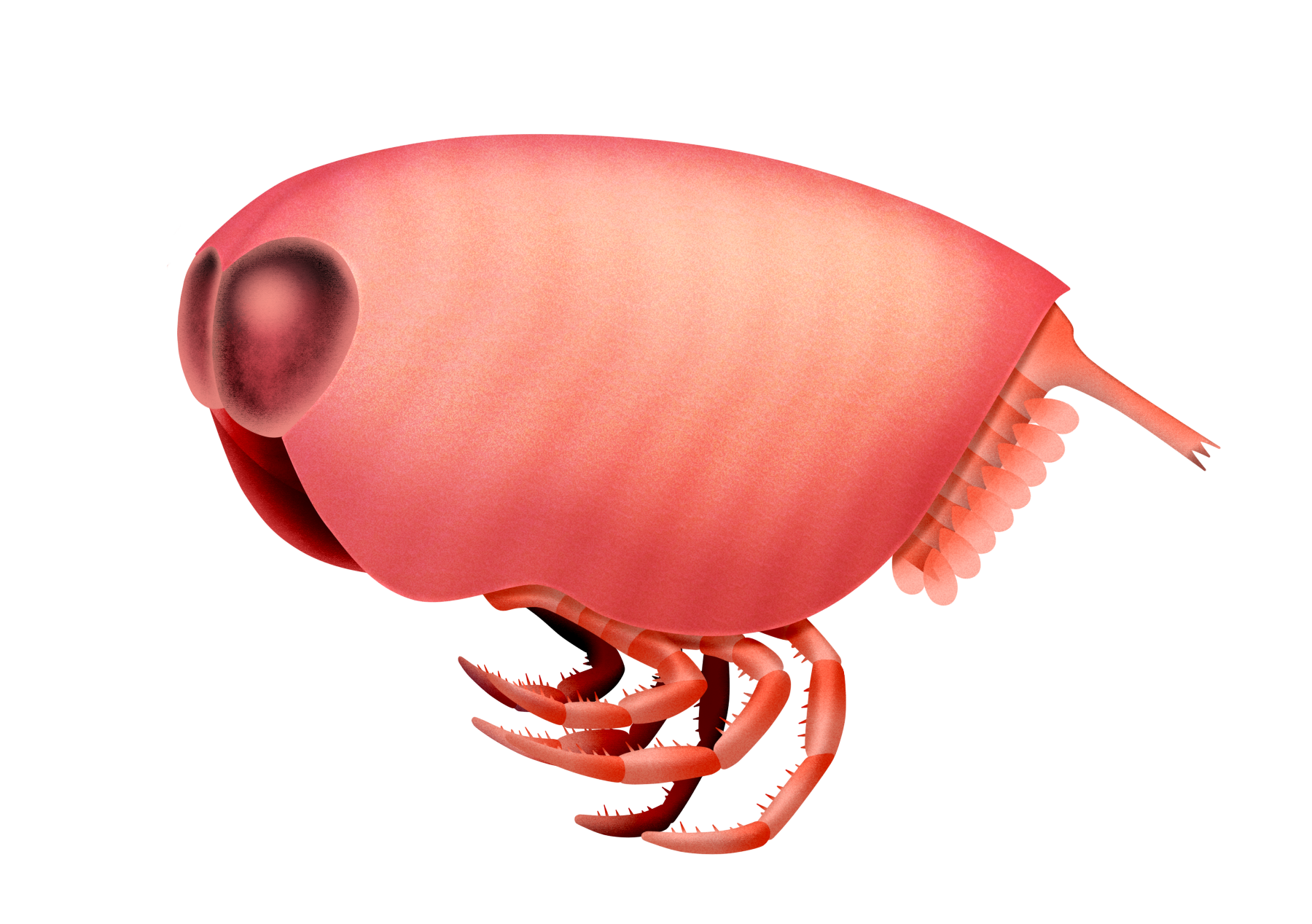

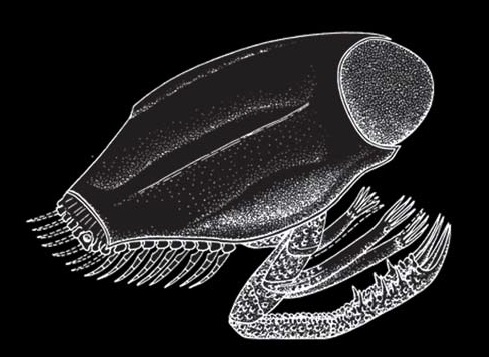

The Thylacocephala are bivalved arthropods with morphology exemplified by three pairs of long

Based on Vannier, modified after Schram:

The Thylacocephala are bivalved arthropods with morphology exemplified by three pairs of long

It is universally accepted that the Thylacocephala are

It is universally accepted that the Thylacocephala are

Numerous modes of life have been suggested for the Thylacocephala.

Secrétan suggested ''Dollocaris ingens'' was too large to swim, so inferred a predatory 'lurking' mode of life, lying in wait on the sea bed and then springing out to capture prey. The author also suggested it could be necrophagous, supported by Alessandrello ''et al.'', who suggest they would have been incapable of directly killing the shark remains found in the Osteno specimens' alimentary residues. Instead they surmise the Thylacocephala could have ingested shark vomit which included such remains.

Vannier ''et al.'' note the Thylacocephala possess features which would suggest adaptations for swimming in dim-light environments – a thin, non-mineralized carapace, well-developed rostral spines for possible buoyancy control in some species, a battery of pleopods for swimming, and large prominent eyes. This is supported by the Cretaceous species from Lebanon, which show adaptations for swimming, and possibly schooling.

Rolfe provides many possibilities, but concludes a realistic mode of life is mesopelagic, by analogy with

Numerous modes of life have been suggested for the Thylacocephala.

Secrétan suggested ''Dollocaris ingens'' was too large to swim, so inferred a predatory 'lurking' mode of life, lying in wait on the sea bed and then springing out to capture prey. The author also suggested it could be necrophagous, supported by Alessandrello ''et al.'', who suggest they would have been incapable of directly killing the shark remains found in the Osteno specimens' alimentary residues. Instead they surmise the Thylacocephala could have ingested shark vomit which included such remains.

Vannier ''et al.'' note the Thylacocephala possess features which would suggest adaptations for swimming in dim-light environments – a thin, non-mineralized carapace, well-developed rostral spines for possible buoyancy control in some species, a battery of pleopods for swimming, and large prominent eyes. This is supported by the Cretaceous species from Lebanon, which show adaptations for swimming, and possibly schooling.

Rolfe provides many possibilities, but concludes a realistic mode of life is mesopelagic, by analogy with

head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

") are group of extinct probable mandibulate arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s, that have been considered by some researchers as having possible crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

affinities. As a class they have a short research history, having been erected in the early 1980s.

They typically possess a large, laterally flattened carapace that encompasses the entire body. The compound eye

A compound eye is a Eye, visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidium, ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens (anatomy), lens, and p ...

s tend to be large and bulbous, and occupy a frontal notch on the carapace. They possess three pairs of large raptorial

In biology (specifically the anatomy of arthropods), the term ''raptorial'' implies much the same as ''predatory'' but most often refers to modifications of an arthropod leg, arthropod's foreleg that make it function for the grasping of prey whi ...

limbs, and the abdomen bears a battery of small swimming limbs. Their size ranges from ~15 mm to potentially up to 250 mm.

Inconclusive claims of thylacocephalans have been reported from the lower lower Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

('' Zhenghecaris''), but later study considered that genus as radiodont or arthropod with uncertain systematic position. The oldest unequivocal fossils are Upper Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and System (geology), system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era (geology), Era, and the second of twelve periods of the Phanerozoic Eon (geology), Eon. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years f ...

and Lower Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 23.5 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the third and shortest period of t ...

in age. As a group, the Thylacocephala survived to the Santonian

The Santonian is an age in the geologic timescale or a chronostratigraphic stage. It is a subdivision of the Late Cretaceous Epoch or Upper Cretaceous Series. It spans the time between 86.3 ± 0.7 mya ( million years ago) and 83.6 ± 0.7 m ...

stage of the Upper Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

, around 84 million years ago./ref> Beyond this, there remains much uncertainty concerning fundamental aspects of the thylacocephalan anatomy, mode of life, and relationship to the Crustacea, with whom they have always been cautiously aligned.

Research history

The Thylacocephala is only recently described as aclass

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

, yet species now included within the group were first described at the turn of the century. These were typically assigned to the phyllocarids despite an apparent lack of abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front part of the torso between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and in other vertebrates. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal ...

and appendages. In 1982/83, three research groups independently created higher taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

to accommodate new species. Based on a specimen from northern Italy, Pinna ''et al.'' designated a new class, Thylacocephala, while Secrétan – studying ''Dollocaris ingens'', a species from the La Voulte-sur-Rhône konservat- lagerstätte in France – erected the class Conchyliocarida. Briggs & Rolfe, working on fossils from Australia's Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

deposits were unable to attribute certain specimens to a known group, and created an order of uncertain affinities, the Concavicarida, to accommodate them. It was apparent the three groups were in fact working on a single major taxon (Rolfe noted disagreements over interpretation and taxonomic placement largely resulted from a disparity of sizes and differences in preservation.) The group took the name Thylacocephala by priority, with Concavicarida and Conchyliocarida subjugated to orders, erected by Rolfe, and modified by Schram.

Taxonomy

Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 23.5 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the third and shortest period of t ...

), '' Harrycaris'' (Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

), '' Concavicaris'' (Devonian to Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

), '' Dollocaris'' (Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

).

*Conchyliocarida Secrétan, 1983:

** Lacks an optic notch

** Eyes on a protruding sac-like cephalon

** No rostrum.

** Order includes '' Convexicaris'' (Carboniferous), '' Yangzicaris'' (Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

), and '' Atropicaris'', '' Austriocaris'', '' Clausocaris'', '' Kilianocaris'', '' Ostenocaris'', and '' Paraostenia'' from the Jurassic.

The accuracy of this scheme has been questioned in recent papers, as it stresses differences in the eyes and exoskeletal structure, which – in modern arthropods – tend to be a response to environmental conditions. Thus it has been suggested these features are too strongly controlled by external factors to be used alone to distinguish higher taxa. The problem is exacerbated by the limited number of thylacocephalan species known. More reliable anatomical indicators would include segmentation and appendage attachments (requiring the internal anatomy, currently elusive as a result of the carapace).

Genera

Class: Thylacocephala

* '' Ainiktozoon''

* '' Ankitokazocaris''

* '' Eodollocaris''

* '' Falcatacaris''

* '' Ligulacaris''

* '' Paraostenia''

* '' Polzia''

* '' Rugocaris''

* '' Silesicaris''

*'' Stoppanicaris''

* '' Thylacares''

* '' Victoriacaris''

* Order Concavicarida

** Family Austriocarididae

*** '' Austriocaris''

*** '' Yangzicaris''

** Family Clausocarididae

*** '' Clausocaris''

*** '' Convexicaris''

** Family Concavicarididae

*** '' Concavicaris''

*** '' Harrycaris''

*** '' Paraconcavicaris''

** Family: Microcarididae

*** '' Atropicaris''

*** '' Ferrecaris''

*** '' Keelicaris''

*** '' Microcaris''

*** '' Thylacocephalus''

** Family: Protozoeidae

*** '' Globulocaris''

*** '' Hamaticaris''

*** '' Protozoea''

*** '' Pseuderichthus''

* Order Conchyliocarida

** Family: Dollocarididae

*** '' Dollocaris''

*** '' Mayrocaris''

*** '' Paradollocaris''

*** '' Thylacocaris ''

** Family: Ostenocarididae

*** '' Kilianocaris''

*** '' Ostenocaris''

Class: Thylacocephala

* '' Ainiktozoon''

* '' Ankitokazocaris''

* '' Eodollocaris''

* '' Falcatacaris''

* '' Ligulacaris''

* '' Paraostenia''

* '' Polzia''

* '' Rugocaris''

* '' Silesicaris''

*'' Stoppanicaris''

* '' Thylacares''

* '' Victoriacaris''

* Order Concavicarida

** Family Austriocarididae

*** '' Austriocaris''

*** '' Yangzicaris''

** Family Clausocarididae

*** '' Clausocaris''

*** '' Convexicaris''

** Family Concavicarididae

*** '' Concavicaris''

*** '' Harrycaris''

*** '' Paraconcavicaris''

** Family: Microcarididae

*** '' Atropicaris''

*** '' Ferrecaris''

*** '' Keelicaris''

*** '' Microcaris''

*** '' Thylacocephalus''

** Family: Protozoeidae

*** '' Globulocaris''

*** '' Hamaticaris''

*** '' Protozoea''

*** '' Pseuderichthus''

* Order Conchyliocarida

** Family: Dollocarididae

*** '' Dollocaris''

*** '' Mayrocaris''

*** '' Paradollocaris''

*** '' Thylacocaris ''

** Family: Ostenocarididae

*** '' Kilianocaris''

*** '' Ostenocaris''

Anatomy

Based on Vannier, modified after Schram:

The Thylacocephala are bivalved arthropods with morphology exemplified by three pairs of long

Based on Vannier, modified after Schram:

The Thylacocephala are bivalved arthropods with morphology exemplified by three pairs of long raptorial

In biology (specifically the anatomy of arthropods), the term ''raptorial'' implies much the same as ''predatory'' but most often refers to modifications of an arthropod leg, arthropod's foreleg that make it function for the grasping of prey whi ...

(predatory) appendages and hypertrophied eyes. They have a worldwide distribution. A laterally compressed, shield−like carapace encloses the entire body, and often has an anterior rostrum−notch complex and posterior rostrum. Its lateral surface can be externally ornamented, and evenly convex or with longitudinal ridges. Spherical or drop-shaped eyes are situated in the optic notches, and are often hypertrophied, filling the notches or forming a paired, frontal globular structure. No prominent abdominal features emerge from the carapace, and the cephalon is obscured. Even so, some authors have suggested the presence of five cephalic appendages, three of which could be the very long genticulate and chelate raptorials protruding beyond the ventral margin. Alternatively these could originate from three anterior trunk segments. The posterior trunk has a series of eight to twenty styliform, filamentous pleopod-like appendages, decreasing in size posteriorly. Most Thylacocephala have eight pairs of well developed gills, found in the trunk region.

Beyond this there is a lack of knowledge about even basic thylacocephalan anatomy, including the number of posterior segments, origin of the raptorials, number of cephalic appendages, shape and attachment of gills, character of mouth, stomach and gut. This results from the class's all–encompassing carapace, which prevents the study of their internal anatomy in fossils.Affinities

It is universally accepted that the Thylacocephala are

It is universally accepted that the Thylacocephala are arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s, yet the position within this phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

is debated. It had formerly been cautiously assumed that the class was a member of the Crustacea

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

, but no conclusive proof exists. The strongest apomorphy

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel Phenotypic trait, character or character state that has evolution, evolved from its ancestral form (or Plesiomorphy and symplesiomorphy, plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy sh ...

aligning the class with other crustaceans is the carapace. As this feature has evolved independently numerous times within the Crustacea and other arthropods, it is not a very reliable pointer, and such evidence alone remains insufficient to align the class with the crustaceans.

Of the features which could prove crustacean affinities, the arrangement of mouthparts would be the easiest to find in the Thylacocephala. The literature features some mention of such a head arrangement, but none definitive. Schram reports the discovery of mandibles in the Mazon Creek thylacocephalan ''Concavicaris georgeorum''. Secrétan also mentions – with caution – possible mandibles in serial sections of ''Dollocaris ingens'', and traces of small limbs in the cephalic region (not well preserved enough to assess their identity). Lange ''et al.'' report a new genus and species, ''Thylacocephalus cymolopos'', from the Upper Cretaceous of Lebanon, which has two possible pairs of antennae, but note the possession of two pairs of antennae alone does not prove the class occupies a position in the crown-group Crustacea.

Despite a lack of evidence for a crustacean body plan, several authors have aligned the class with different groups of crustaceans. Schram provides an overview of possible affinities:

*Nothing in either Uniramia or Cheliceriformes seems likely.

*Conchostraca is possible, but there is no strong supporting evidence.

*A maxillopodan connection is possible. Largely considered due to the Italian researchers' insistence (see disagreements).

* Stomatopods show many parallels but have no comparison to cephalon or body regions.

* Remipedes show some parallels.

* Decapod-like gills suggest malacostraca

Malacostraca is the second largest of the six classes of pancrustaceans behind insects, containing about 40,000 living species, divided among 16 orders. Its members, the malacostracans, display a great diversity of body forms and include crab ...

n affinities.

In these various interpretations, numerous different limb arrangements for the three raptorials have been proposed:

*antennules, antennae and mandibles

*antennules, antennae and maxillipeds

*thoracic (in keeping with stromatopod analogies)

*maxillules, maxillae, maxillipedes

Further work is necessary to provide any solid conclusions.

A study in 2022 describing a new arthropod from Wisconsin, '' Acheronauta'', found that the Thylacocephalans occupied a position more primitive than the crustaceans and myriapods as basal stem-group mandibulates. This would place them outside of the crustaceans as a more basal branch of the arthropod family tree.

This cladogram represents the placement of the Thylacocephalans within the arthropoda as suggested by Pulsipher, 2022.

Disagreements

Numerous conflicts of opinion surround the Thylacocephala, of which the split between the “Italian school” and rest of the world is the most notable. Based on poorly preserved '' Ostenocaris cypriformis'' fossils from the Osteno deposits ofLombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

, Pinna ''et al.'' erected the class Thylacocephala. Based on inferred cirripede affinities the authors concluded the frontal lobed structure was not an eye, but a 'cephalic sac'. This opinion arose from the misinterpretation of the stomach as a reproductive organ (its contents included vertebral elements of fish, thought to be ovarian eggs). Such an arrangement is reminiscent of cirripede crustaceans, leading the authors to suggest a sessile, filter feeding mode of life, the 'cephalic sac' used to anchor the organism to the seabed. The researchers have since conceded it is highly improbable the ovaries are situated in the head, but maintain that the frontal structure is not an eye. Instead they suggest the 'cephalic sac' is covered with microsclerites, their arguments most recently presented in Alessandrello ''et al.''

*The structure is complex and "presumably multipurpose"

*“Apart from a few features” it shows little affinity with a compound eye

*There is a close connection with stomach residues, sac muscular system and outer hexagonal layer

*Having a stomach between the eyes is unusual

*Sclerite

A sclerite (Greek language, Greek , ', meaning "hardness, hard") is a hardened body part. In various branches of biology the term is applied to various structures, but not as a rule to vertebrate anatomical features such as bones and teeth. Instea ...

s that should correspond to rhabdoms in 'eye theory' are interstitial to the hexagons, not at centre as would be expected for individual ommatidium.

*Structural analogy with cirriped peduncle

Instead the authors suggest the sac is used to break down coarse chunks of food and reject indigestible portions.

All other parties interpret this as a large compound eye, the hexagons being preserved ommatidia (all researchers agree these are the same structure). This is supported by fossils of ''Dollocaris ingens'' which are so well preserved that individual retinula cells can be discerned. The preservation is so exceptional that studies have shown the species' numerous small ommatidia, distributed over the large eyes, could reduce the angle between ommatidia, thus improve their ability to detect small objects. Of the arguments above, it is posited by opponents that eyes are complex structures, and those in the Thylacocephala display clear and numerous affinities with compound eyes in other arthropod fossils, down to a cellular level of detail. The 'cephalic sac' structure itself is poorly preserved in Osteno specimens, a possible reason for interstitial 'sclerites'. The structural analogy with a cirripede peduncle lost supporting evidence when the 'ovaries' were shown to be alimentary residues, and the sac muscular system could be used to support the eyes. The unusual position of the stomach is thus the strongest inconsistency, but the Thylacocephala are defined by their unusual features, so this is not inconceivable. Further, Rolfe suggests the eyes' position can be explained if they have a large posterior area of attachment, while Schram suggests that the stomach region extending into the cephalic sac could result from an inflated foregut or anteriorly directed caecum.

Discussion of the matter has ceased in the last decade, and most researchers accept the anterior structure is an eye. Confusion is most likely the result of differing preservation in Osteno.

Mode of life

Numerous modes of life have been suggested for the Thylacocephala.

Secrétan suggested ''Dollocaris ingens'' was too large to swim, so inferred a predatory 'lurking' mode of life, lying in wait on the sea bed and then springing out to capture prey. The author also suggested it could be necrophagous, supported by Alessandrello ''et al.'', who suggest they would have been incapable of directly killing the shark remains found in the Osteno specimens' alimentary residues. Instead they surmise the Thylacocephala could have ingested shark vomit which included such remains.

Vannier ''et al.'' note the Thylacocephala possess features which would suggest adaptations for swimming in dim-light environments – a thin, non-mineralized carapace, well-developed rostral spines for possible buoyancy control in some species, a battery of pleopods for swimming, and large prominent eyes. This is supported by the Cretaceous species from Lebanon, which show adaptations for swimming, and possibly schooling.

Rolfe provides many possibilities, but concludes a realistic mode of life is mesopelagic, by analogy with

Numerous modes of life have been suggested for the Thylacocephala.

Secrétan suggested ''Dollocaris ingens'' was too large to swim, so inferred a predatory 'lurking' mode of life, lying in wait on the sea bed and then springing out to capture prey. The author also suggested it could be necrophagous, supported by Alessandrello ''et al.'', who suggest they would have been incapable of directly killing the shark remains found in the Osteno specimens' alimentary residues. Instead they surmise the Thylacocephala could have ingested shark vomit which included such remains.

Vannier ''et al.'' note the Thylacocephala possess features which would suggest adaptations for swimming in dim-light environments – a thin, non-mineralized carapace, well-developed rostral spines for possible buoyancy control in some species, a battery of pleopods for swimming, and large prominent eyes. This is supported by the Cretaceous species from Lebanon, which show adaptations for swimming, and possibly schooling.

Rolfe provides many possibilities, but concludes a realistic mode of life is mesopelagic, by analogy with hyperiid

The Hyperiidea is one ot the six suborders of amphipods, small aquatic crustaceans. Unlike some other suborders of Amphipoda, hyperiids are exclusively marine and do not occur in fresh water. Hyperiids are distinguished by their large eyes and ...

amphipods

Amphipoda () is an order (biology), order of malacostracan crustaceans with no carapace and generally with laterally compressed bodies. Amphipods () range in size from and are mostly detritivores or scavengers. There are more than 10,700 amphip ...

. Further suggests floor-dwelling is also possible, and that the organism could rise to catch prey during the day and return to the sea floor at night. Another notable proposal is that, like hyperiids, the class could gain oil from their food source for buoyancy, an idea supported by their diet (known from stomach residues containing shark and coleoid remains, and other Thylacocephala).

Alessandrello ''et al.'' suggest a head-down, semi-sessile life on a soft bottom, in agreement with that of Pinna ''et al.'', based on cirripede affinities. A necrophagous diet is suggested.

Briggs & Rolfe report that all the Gogo formation Thylacocephala are found in a reef formation, suggesting a shallow water environment. The authors speculate that due to the terracing of the carapace an infaunal mode of life is possible, or the ridges could provide more friction for hiding in crevices of rock.

Schram suggests a dichotomy in size of the class results from different environments; larger Thylacocephala could have lived in a fluid characterized by turbulent flow, and relied on single power stroke of trunk limbs to position themselves. He suggests that smaller forms may have resided in a viscous medium, characterized by laminar flow, and used a lever to generate the speed necessary to capture prey.

References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q2430260 Prehistoric crustaceans Arthropod classes Prehistoric protostome classes Cambrian first appearances Late Cretaceous extinctions