Dougga or Thugga or TBGG (; ) was a

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

, Punic and

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

settlement near present-day

Téboursouk in northern

Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

. The current

archaeological site

An archaeological site is a place (or group of physical sites) in which evidence of past activity is preserved (either prehistoric or recorded history, historic or contemporary), and which has been, or may be, investigated using the discipline ...

covers .

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

qualified Dougga as a

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

in 1997, believing that it represents "the best-preserved Roman small town in North Africa". The site, which lies in the middle of the countryside, has been protected from the encroachment of modern urbanization, in contrast, for example, to

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

, which has been pillaged and rebuilt on numerous occasions. Dougga's size, its well-preserved monuments and its rich

Numidia

Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya. The polity was originally divided between ...

n-

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

,

Punic

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians (and sometimes as Western Phoenicians), were a Semitic people who migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' ...

,

ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

, and

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

history make it exceptional. Amongst the most famous monuments at the site are a

Libyco-Punic Mausoleum, the Capitol, the

Roman theatre, and the temples of

Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant, with an average radius of about 9 times that of Earth. It has an eighth the average density of Earth, but is over 95 tim ...

and of

Juno Caelestis.

Names

The

Numidian

Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya. The polity was originally divided between ...

name of the settlement was recorded in the

Libyco-Berber alphabet

The Libyco-Berber alphabet is an abjad writing system that was used during the first millennium BC by various Berbers, Berber peoples of North Africa and the Canary Islands, to write ancient varieties of the Berber language like the Numidian lang ...

as TBGG. The

Punic

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians (and sometimes as Western Phoenicians), were a Semitic people who migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' ...

name of the settlement is recorded as () and (). The Root B GG in Phoenician means ("in the roof terrace").

Camps states that this may represent a borrowing of a

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

word derived from the root ("to protect").

[Gabriel Camps, « Dougga », ''L'Encyclopédie berbère'', tome XVI, éd. Edisud, Aix-en-Provence, 1992, p. 2522] This evidently derives from the site's position atop an easily defensible

plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; : plateaus or plateaux), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. ...

. The name was borrowed into

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

as Thugga. Once it was granted "free status", it was formally refounded and known as '; "Septimium" and "Aurelium" are references to the "new" town's "founders" ('),

Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; ; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through cursus honorum, the ...

and M. Aurelius Antoninus (i.e.,

Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname Caracalla (; ), was Roman emperor from 198 to 217 AD, first serving as nominal co-emperor under his father and then r ...

). For treatment of ', see below. Once Dougga received the status of a Roman colony, it was formally known as '.

In present-day

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

, it is known as either ''Dugga'' or ''Tugga''. That was borrowed into or and Dougga is a

French transcription of this Arabic name.

Location

The archaeological site is located SSW of the modern town of

Téboursouk on a plateau with an uninhibited view of the surrounding plains in the Oued Khalled. The site offers a high degree of natural protection, which helps to explain its early occupation. The slope on which Dougga is built rises to the north and is bordered in the east by the cliff known as Kef Dougga. Further to the east, the ridge of the

Fossa Regia

The Fossa Regia, also called the ''Fosse Scipio'', was the first part of the Borders of the Roman Empire#The southern borders, Limes Africanus to be built in Roman Africa (Roman province), Africa. It was used to divide the Berbers, Berber kingdom o ...

, a ditch and boundary made by the Romans after the destruction of Carthage, indicates Dougga's position as a point of contact between the

Punic

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians (and sometimes as Western Phoenicians), were a Semitic people who migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' ...

and

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

worlds.

History

Dougga's history is best known from the time of the Roman conquest, even though numerous pre-Roman monuments, including a

necropolis

A necropolis (: necropolises, necropoles, necropoleis, necropoli) is a large, designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The name stems from the Ancient Greek ''nekropolis'' ().

The term usually implies a separate burial site at a distan ...

, a

mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be considered a type o ...

, and several

temple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a place of worship, a building used for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. By convention, the specially built places of worship of some religions are commonly called "temples" in Engli ...

s have been discovered during archaeological digs. These monuments are an indication of the site's importance before the arrival of the Romans.

Berber Kingdom

The city appears to have been founded in the 6th century BC.

[Mustapha Khanoussi, « L'évolution urbaine de Thugga (Dougga) en Afrique proconsulaire : de l'agglomération numide à la ville africo-romaine », ''CRAI'', 2003, pp. 131-155] Some historians believe that Dougga is the city of Tocae (, ''Tokaí''), which was captured by a lieutenant of

Agathocles

Agathocles ( Greek: ) is a Greek name. The most famous person called Agathocles was Agathocles of Syracuse, the tyrant of Syracuse. The name is derived from and .

Other people named Agathocles include:

*Agathocles, a sophist, teacher of Damon

...

of

Syracuse

Syracuse most commonly refers to:

* Syracuse, Sicily, Italy; in the province of Syracuse

* Syracuse, New York, USA; in the Syracuse metropolitan area

Syracuse may also refer to:

Places

* Syracuse railway station (disambiguation)

Italy

* Provi ...

at the end of the 4th centuryBC;

Diodorus of Sicily

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which survive intact, bet ...

described Tocae as "a city of beautiful grandeur".

Dougga was in any case an early and important human settlement. Its urban character is evidenced by the presence of a necropolis with

dolmen

A dolmen, () or portal tomb, is a type of single-chamber Megalith#Tombs, megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the Late Neolithic period (4000 ...

s, the most ancient archaeological find at Dougga, a sanctuary dedicated to

Ba'al Hammon, neo-Punic

stele

A stele ( ) or stela ( )The plural in English is sometimes stelai ( ) based on direct transliteration of the Greek, sometimes stelae or stelæ ( ) based on the inflection of Greek nouns in Latin, and sometimes anglicized to steles ( ) or stela ...

s, a mausoleum, architectural fragments, and a temple dedicated to

Masinissa

Masinissa (''c.'' 238 BC – 148 BC), also spelled Massinissa, Massena and Massan, was an ancient Numidian king best known for leading a federation of Massylii Berber tribes during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), ultimately uniting the ...

, the remains of which were found during archaeological excavations. Even though our knowledge of the city before the Roman conquest remains very limited, recent archaeological finds have revolutionized the image that we had of this period.

The identification of the temple dedicated to Masinissa beneath the

forum disproved Louis Poinssot's theory that the Numidian city stood on the plateau but that it was separate from the newer Roman settlement. The temple, which was erected in the tenth year of

Micipsa

Micipsa ( Numidian: ''Mikiwsan''; , ; died BC) was the eldest legitimate son of Masinissa, the King of Numidia, a Berber kingdom in North Africa. Micipsa became the King of Numidia in 148 BC.

Early life

In 151 BC, Masinissa sent Micipsa and his ...

's reign (139BC), is wide. It proves that the area around the forum was already built upon before the arrival of the Roman colonists.

A building dating to the 2nd centuryBC has also been discovered nearby. Similarly, Dougga's mausoleum is not isolated but stands within an urban necropolis.

Recent finds have disproved earlier theories about the so-called "Numidian walls". The walls around Dougga are in fact not Numidian; they are part of the city's fortifications erected in

late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

. Targeted digs have also proven that what had been interpreted as two Numidian towers in the walls are in fact two funeral monuments from the Numidian era reused much later as foundations and a section of defences.

The discovery of Libyan and Punic inscriptions at the site provoked a debate on the administration of the city at the time of the Kingdom of

Numidia

Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya. The polity was originally divided between ...

. The debateabout the interpretation of

epigraphic

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the wr ...

sourcesfocussed on the question of whether the city was still under Punic influence or whether it was increasingly Berber. Local Berber institutions distinct from any form of Punic authority arose from the Numidian period onwards, but

Camps notes that

Punic shofets were still in place in several cities, including Dougga, during the Roman era, which is a sign of continuing Punic influence and the preservation of certain elements of Punic civilization well after the fall of Carthage.

Roman Empire

The Romans granted Dougga the status of an indigenous city () following their conquest of the region.

The creation of the

colony

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their ''metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often orga ...

of

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

during the reign of

Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

complicated Dougga's institutional status. The city was included in the territory (''pertica'') of the Roman colony, but around this time, a

community

A community is a social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant characteristic, such as place, set of norms, culture, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given g ...

(') of Roman colonists also arose alongside the existing settlement. For two centuries, the site was thus governed by two civic and institutional bodies: the city with its

peregrini

In the early Roman Empire, from 30 BC to AD 212, a ''peregrinus'' () was a free provincial subject of the Empire who was not a Roman citizen. ''Peregrini'' constituted the vast majority of the Empire's inhabitants in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. ...

and the ' with its

Roman citizens

Citizenship in ancient Rome () was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cu ...

. Both had Roman civic institutions: magistrates and a council (') of

decurions for the city, a local council from the end of the 1st centuryAD, and local administrators for the ', who were legally subordinated to the distant but powerful colony of Carthage. In addition, epigraphic evidence indicates that a

Punic

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians (and sometimes as Western Phoenicians), were a Semitic people who migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' ...

-style dual magistracy, the ''

sufet

In several ancient Semitic-speaking cultures and associated historical regions, the shopheṭ or shofeṭ (plural shophetim or shofetim; , , , the last loaned into Latin as sūfes; see also ) was a community leader of significant civic stature, o ...

es'', achieved some civic stature here well into the imperial period. In fact, the city once had three magistrates serve at once, a relative rarity in the Mediterranean.

Over time, the

romanization

In linguistics, romanization is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Latin script, Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and tra ...

of the city brought the two communities closer together. Notable members of the ' increasingly adopted Roman culture and behavior, became Roman citizens, and the councils of the two communities began to take decisions in unison. The increasing closeness of the communities was facilitated at first by their geographic proximitythere was no physical distinction between their two settlementsand then later by institutional arrangements. During the reign of

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus ( ; ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 and a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors ...

, the city was granted

Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (), to the (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I.

Roman law also den ...

; from this moment onward, the magistrates automatically received

Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome () was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cu ...

and the rights of the city's inhabitants became similar to those of the Roman citizens. During the same era, the ' won a certain degree of autonomy from Carthage; it was able to receive bequests and administer public funds.

Nonetheless, it was not until AD205, during the reign of

Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; ; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through cursus honorum, the ...

, that the two communities came together as one

municipality

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having municipal corporation, corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality' ...

('), made "free" (see below) while Carthage's ' was reduced. The city was supported by the

euergetism of its great families of wealthy individuals, which sometimes reached exorbitant levels, while its interests were successfully represented by appeals to the

emperors

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/ grand empress dowager), or a woman who rule ...

. Dougga's development culminated during the reign of

Gallienus

Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus (; – September 268) was Roman emperor with his father Valerian from 253 to 260 and alone from 260 to 268. He ruled during the Crisis of the Third Century that nearly caused the collapse of the empire. He ...

, when it obtained the status of a separate

Roman colony

A Roman (: ) was originally a settlement of Roman citizens, establishing a Roman outpost in federated or conquered territory, for the purpose of securing it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It ...

.

Dougga's monuments attest to its prosperity in the period from the reign of

Diocletian

Diocletian ( ; ; ; 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed Jovius, was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Diocles to a family of low status in the Roman province of Dalmatia (Roman province), Dalmatia. As with other Illyri ...

to that of

[Collectif, ''L'Afrique romaine. 69-439'', p. 310] but it fell into a sort of stupor from the 4th century. The city appears to have experienced an early decline, as evidenced by the relatively poor remains of

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

.

The period of

Byzantine rule saw the area around the forum transformed into a fort; several important buildings were destroyed in order to provide the necessary materials for its construction.

Caliphate

Dougga was never completely abandoned following the

Muslim invasions of the area. For a long time, Dougga remained the site of a small village populated by the descendants of the city's former inhabitants, as evidenced by the small

mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

situated in the Temple of August Piety and the small bath dating to the

Aghlabid period on the southern flank of the forum.

Archaeological work

The first Western visitors to have left eyewitness accounts of the ruins reached the site in the 17th century. This trend continued in the 18th century and at the start of the 19th century.

[Exploration et collections du site de Dougga (Strabon)](_blank)

/ref> The best-preserved monuments, including the mausoleum, were described and, at the end of this period, were the object of architectural studies.

The establishment of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

's Tunisian protectorate in 1881 led to the creation of a national antiquities institute (), for which the excavation of the site at Dougga was a priority from 1901, parallel to the works carried out at Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

. The works at Dougga concentrated at first on the area around the forum; other discoveries ensured that there was an almost constant series of digs at the site until 1939. Alongside these excavations, work was conducted to restore the capitol, of which only the front and the base of the wall of the cella were still standing, and to restore the mausoleum, particularly between 1908 and 1910 .UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

list of World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

s.

Despite its importance and its exceptional state, Dougga remains off the beaten track for many tourists and receives only about 50,000 visitors per year. In order to make it more attractive, the construction of an on-site museum is being considered, while the national antiquities institute has established a website presenting the site and the surrounding region. For the time being, visitors with sufficient time can appreciate Dougga, not only because of its many ruins but also for its olive groves, which give the site a unique ambiance.

Dougga's "Liberty"

From AD205, when the city (') and community (') fused into one municipality ('), Dougga bore the title ''liberum'', whose significance is not immediately clear. The term appears in the titles of a certain number of other ' also founded at the same time: Thibursicum Bure, Aulodes, and Thysdrus. Several interpretations of its meaning have been suggested.

From AD205, when the city (') and community (') fused into one municipality ('), Dougga bore the title ''liberum'', whose significance is not immediately clear. The term appears in the titles of a certain number of other ' also founded at the same time: Thibursicum Bure, Aulodes, and Thysdrus. Several interpretations of its meaning have been suggested.[ Claude Lepelley, « Thugga au IIIe siècle : la défense de la liberté », ''Dougga (Thugga). Études épigraphiques'', éd. Ausonius, Bordeaux, 1997, pp. 105-114, also available in Claude Lepelley, ''Aspects de l'Afrique romaine : les cités, la vie rurale, le christianisme'', éd. Edipuglia, Bari, 2001, pp. 69-81] According to Merlin

The Multi-Element Radio Linked Interferometer Network (MERLIN) is an interferometer array of radio telescopes spread across England. The array is run from Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire by the University of Manchester on behalf of UK Re ...

and Poinssot, the term derives from the name of the god Liber

In Religion in ancient Rome, ancient Roman religion and Roman mythology, mythology, Liber ( , ; "the free one"), also known as Liber Pater ("the free Father"), was a god of viticulture and wine, male fertility and freedom. He was a patron de ...

, in whose honor a temple was erected at Dougga. The epithet ''Liberum'' would thus follow the same pattern as ' and ', which appear in the title of Thibursicum Bure. Thibursicum Bure is however an exception to the rule; the titles of the other ' including the term ' do not include the names of any divinities, and this hypothesis has therefore been abandoned.Alexander Severus

Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander (1 October 208 – March 235), also known as Alexander Severus, was Roman emperor from 222 until 235. He was the last emperor from the Severan dynasty. Alexander took power in 222, when he succeeded his slain co ...

as the "preserver of liberty" (').

It is, however, unclear exactly what form this liberty took. Toutain Toutain is a French surname of Norman origin, itself from Old Norse '' Þórsteinn''. Albert Dauzat, ''Noms et prénoms de France'', Librairie Larousse 1980, édition revue et commentée par Marie-Thérèse Morlet, p. 572b Notable people with the s ...

is of the opinion that this is a designation for a particular type of 'free cities where the Roman governor did not have the right to control the municipal magistrates. There is however no evidence that Dougga enjoyed exceptional legal privileges of the type associated with certain free cities such as Aphrodisias

Aphrodisias (; ) was a Hellenistic Greek city in the historic Caria cultural region of western Asia Minor, today's Anatolia in Turkey. It is located near the modern village of Geyre, about east/inland from the coast of the Aegean Sea, and s ...

in Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

. Veyne has thus suggested that Dougga's "freedom" is nothing but an expression of the concept of liberty without any legal meaning; obtaining the status of a ' had freed the city of its subjugation and enabled it to adorn itself with the "ornaments of liberty" ('). The city's liberty was celebrated just as its dignity was extolled; the emperor Probus Probus may refer to:

People

* Marcus Valerius Probus (c. 20/30–105 AD), Roman grammarian

* Marcus Pomponius Maecius Probus, consul in 228

* Probus (emperor), Roman Emperor (276–282)

* Probus of Byzantium (–306), Bishop of Byzantium from 293 t ...

is a "preserver of liberty and dignity" ('). Gascou, in line with Veyne's interpretation, describes the situation thus: "', in ''Thugga''s title, is a term ..with which the city, which had waited a long time for the status of a municipium, is happy to flatter itself".

Despite Gascou's conclusion, efforts have been made more recently to identify concrete aspects of Dougga's liberty. Lepelley believes on the one hand that this must be a reference to the relations between the city and

Despite Gascou's conclusion, efforts have been made more recently to identify concrete aspects of Dougga's liberty. Lepelley believes on the one hand that this must be a reference to the relations between the city and Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

and on the other hand that the term can cover a range of diverse privileges of differing degrees.Trajan

Trajan ( ; born Marcus Ulpius Traianus, 18 September 53) was a Roman emperor from AD 98 to 117, remembered as the second of the Five Good Emperors of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was a philanthropic ruler and a successful soldier ...

's reign to defend the fiscal immunity of the territory of Carthage ('). The Dougga ' had not been granted this concession, so the fusion of ' with the ' meant that the citizens of the ' risked losing their enviable privilege. The liberty of the ' founded during the reign of Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; ; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through cursus honorum, the ...

could thus be a reference to the fiscal immunity made possible by the region's great wealth and by the emperor's generosity to each ' at the time of its fusion. During the reign of Gallienus

Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus (; – September 268) was Roman emperor with his father Valerian from 253 to 260 and alone from 260 to 268. He ruled during the Crisis of the Third Century that nearly caused the collapse of the empire. He ...

, a certain Aulus Vitellius Felix Honoratus, a well-known individual in Dougga, made an appeal to the emperor "in order to assure the public liberty". Lepelley believes that this is an indication that the city's privilege had been called into question, although Dougga appears to have been at least partially able to preserve its concessions, as evidenced by an inscription to the honor of "Probus, defender of its liberty".Michel Christol

Michel Christol (25 October 1942, Castelnau-de-Guers) is a French historian, specialist of ancient Rome, and particularly epigraphy.

Biography

Born in Herault, Michel Christol attended high school in Béziers then his university studies in Mon ...

, ''Regards sur l'Afrique romaine'', éd. Errance, Paris, 2005, p. 191Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus ( ; ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 and a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors ...

and the granting of Roman law that raised the specter of a fusion of the two communities, which would without a doubt have provoked a certain unease in the '. The inhabitants of the ' would have expressed "concern or even refusal when faced with the pretensions of their closest neighbors". This would explain the honor that the ' attributed to Commodus

Commodus (; ; 31 August 161 – 31 December 192) was Roman emperor from 177 to 192, first serving as nominal co-emperor under his father Marcus Aurelius and then ruling alone from 180. Commodus's sole reign is commonly thought to mark the end o ...

(', "protector of the community").

For Christol, the term ' must be understood in this context and in an abstract sense. This liberty derives from belonging to a city and expresses the end of the 's dependence, "the elevation of a community of peregrini to the liberty of Roman citizenship",

General layout

The city as it exists today consists essentially of remains from the Roman era dating for the most part to the 2nd and 3rd century. The Roman builders had to take account both of the site's particularly craggy terrain and of earlier constructions, which led them to abandon the normal layout of Roman settlements,

The city as it exists today consists essentially of remains from the Roman era dating for the most part to the 2nd and 3rd century. The Roman builders had to take account both of the site's particularly craggy terrain and of earlier constructions, which led them to abandon the normal layout of Roman settlements,[Hédi Slim et Nicolas Fauqué, ''La Tunisie antique. De Hannibal à saint Augustin'', éd. Mengès, Paris, 2001, p. 153] as is also particularly evident in places such as Timgad.

Recent archaeological digs have confirmed the continuity in the city's urban development. The heart of the city has always been at the top of the hill, where the forum replaced the Numidian agora

The agora (; , romanized: ', meaning "market" in Modern Greek) was a central public space in ancient Ancient Greece, Greek polis, city-states. The literal meaning of the word "agora" is "gathering place" or "assembly". The agora was the center ...

. As Dougga developed, urban construction occupied the side of the hill, so that the city must have resembled "a compact mass", according to Hédi Slim

Numidian residence

Traces of a residence dating to the Numidian era have been identified in the foundations of the temple dedicated to Liber

In Religion in ancient Rome, ancient Roman religion and Roman mythology, mythology, Liber ( , ; "the free one"), also known as Liber Pater ("the free Father"), was a god of viticulture and wine, male fertility and freedom. He was a patron de ...

. Although these traces are very faint, they served to disprove the theories of the first archaeologists, including Louis Poinssot, that the Roman and pre-Roman settlements were located on separate sites. The two settlements evidently overlapped.

The ''trifolium'' villa

This residence, which dates to the 2nd or 3rd century, stands downhill from the quarters that surround the forum and the principal public monuments in the city, in an area where the streets are winding.

This residence, which dates to the 2nd or 3rd century, stands downhill from the quarters that surround the forum and the principal public monuments in the city, in an area where the streets are winding.[Jean-Claude Golvin, ''L'antiquité retrouvée'', éd. Errance, Paris, 2003, p. 99]

The ''trifolium'' villa, named after a clover

Clovers, also called trefoils, are plants of the genus ''Trifolium'' (), consisting of about 300 species of flowering plants in the legume family Fabaceae originating in Europe. The genus has a cosmopolitan distribution with the highest diversit ...

-shaped room that was without a doubt used as a triclinium

A ''triclinium'' (: ''triclinia'') is a formal dining room in a Ancient Rome, Roman building. The word is adopted from the Greek language, Greek ()—from (), "three", and (), a sort of couch, or rather chaise longue. Each couch was sized to ...

, is the largest private house excavated so far at Dougga. The house had two storeys, but there is almost nothing left of the upper storey. It stands in the south of the city, halfway up the hill. The house is particularly interesting because of the way in which it is built to align with the lay of the land; the entrance hall slopes down to a courtyard around which the various rooms were arranged.

The market

The market dates from the middle of the 1st century. It took the form of a square in size, surrounded by a portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cu ...

and shops on two sides. The northern side had a portico, while an exedra

An exedra (: exedras or exedrae) is a semicircular architecture, architectural recess or platform, sometimes crowned by a semi-dome, and either set into a building's façade or free-standing. The original Greek word ''ἐξέδρα'' ('a seat ou ...

occupied the southern side. The exedra probably housed a statue of Mercury.[Mustapha Khanoussi, ''Dougga'', p. 27]

In order to compensate for the natural incline of the ground on which the market stands, its builders undertook significant earthworks. These earthworks have been dated as being amongst the oldest Roman constructions, and their orientation vis-à-vis the forum seems to suggest that they were not built on any earlier foundations.

Licinian Baths

The Licinian Baths are interesting for having much of its original walls intact, as well as a long tunnel used by the slaves working at the baths. The baths were donated to the city by the Licinii family in the 3rd century. They were primarily used as winter baths. The frigidarium has triple arcades at both ends and large windows with views over the valley beyond.

Funerary structures

Dolmens

The presence of

The presence of dolmen

A dolmen, () or portal tomb, is a type of single-chamber Megalith#Tombs, megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the Late Neolithic period (4000 ...

s in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

has served to stoke historiographic debates that have been said to have ideological agendas. The dolmens at Dougga have been the subject of archaeological digs, which have also uncovered skeletons and ceramic models.

Although it is difficult to put a date on the erection of the dolmens, as they were in use until the dawn of the Christian era, it seems likely that they date from at least 2000 yearsBC. Gabriel Camps

Gabriel Camps (May 20, 1927 – September 6, 2002) was a French archaeologist and social anthropologist, the founder of the '' Encyclopédie berbère'' and is considered a prestigious scholar on the history of the Berber people.

Biography

G ...

has suggested that a link to Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

. He has made the same suggestion for the "''haouanet''" tombs found in Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

and Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

.

Numidian bazina tombs

A type of tomb unique to the Numidian world has been discovered at Dougga. They are referred to as bazina tombs or circular monument tombs.

A type of tomb unique to the Numidian world has been discovered at Dougga. They are referred to as bazina tombs or circular monument tombs.

Punic-Libyan Mausoleum

The Mausoleum of Ateban is one of the very rare examples of royal Numidian architecture. There is another in Sabratha

Sabratha (; also ''Sabratah'', ''Siburata''), in the Zawiya District[Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...](_blank)

. Some authors believe that there is a link with the funeral architecture in Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

and the necropoleis in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

from the 3rd and 2nd centuryBC.[Pierre Gros, ''L'architecture romaine du début du IIIe siècle à la fin du Haut-Empire'', tome 2 « Maisons, palais, villas et tombeaux », éd. Picard, Paris, 2001, p. 417]

This tomb is tall and was built in the 2nd centuryBC. A bilingual inscription installed in the mausoleum mentioned that the tomb was dedicated to Ateban, the son of Iepmatath and Palu. In 1842, Sir Thomas Reade, the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

in Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

seriously damaged the monument while removing this inscription. This bilingual Punic-Libyan Inscription, now held at the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

, made it possible to decode the Libyan characters. It has only recently been established that the inscription was originally located on one side of a fake window on the podium

A podium (: podiums or podia) is a platform used to raise something to a short distance above its surroundings. In architecture a building can rest on a large podium. Podiums can also be used to raise people, for instance the conductor of a ...

. According to the most recent research, the names cited in the inscription are only those of its architect and of representatives of the different professions involved in its construction. The monument was built by the inhabitants of the city for a Numidian prince; some authors believe that it was intended for Massinissa

Masinissa (''c.'' 238 BC – 148 BC), also spelled Massinissa, Massena and Massan, was an ancient Numidian king best known for leading a federation of Massylii Berber tribes during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), ultimately uniting th ...

archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

Louis Poinssot, who essentially reconstructed it from pieces that were left lying on the ground. The tomb is accessed via a pedestal

A pedestal or plinth is a support at the bottom of a statue, vase, column, or certain altars. Smaller pedestals, especially if round in shape, may be called socles. In civil engineering, it is also called ''basement''. The minimum height o ...

with five steps. On the northern side of the podium (the lowest of three levels in the monument), there is an opening to the funeral chamber that is closed with a stone slab. The other sides are decorated with fake windows and four Aeolic

In linguistics, Aeolic Greek (), also known as Aeolian (), Lesbian or Lesbic dialect, is the set of dialects of Ancient Greek spoken mainly in Boeotia; in Thessaly; in the Aegean island of Lesbos; and in the Greek colonies of Aeolis in Anat ...

pilaster

In architecture, a pilaster is both a load-bearing section of thickened wall or column integrated into a wall, and a purely decorative element in classical architecture which gives the appearance of a supporting column and articulates an ext ...

s. The second level is made up of a temple-like colonnade (''naiskos''); the columns on each side are Ionic. The third level is the most richly decorated of all: in addition to pilasters similar to those on the lowest level, it is capped with a pyramid

A pyramid () is a structure whose visible surfaces are triangular in broad outline and converge toward the top, making the appearance roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be of any polygon shape, such as trian ...

. Some elements of carved stone have also survived.

Roman sepulchres

Although work has in the past been undertaken to uncover the Roman sepulchres, today they have been reclaimed in part by

Although work has in the past been undertaken to uncover the Roman sepulchres, today they have been reclaimed in part by olive tree

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'' ("European olive"), is a species of Subtropics, subtropical evergreen tree in the Family (biology), family Oleaceae. Originating in Anatolia, Asia Minor, it is abundant throughout the Mediterranean ...

s.

The different necropoleis mark the zones of settlement at Dougga. There are five areas that have been identified as necropoleis: the first in the northeast, around the Temple of Saturn and the Victoria Church, the second in the northwest, a zone which also encompasses the dolmens on the site, the third in the west, between the Aïn Mizeb and Aïn El Hammam cisterns and to the north of the Temple of Juno Caelestis, the fourth and the fifth in the south and the south-east, one around the mausoleum and the other around Septimius Severus' triumphal arch

A triumphal arch is a free-standing monumental structure in the shape of an archway with one or more arched passageways, often designed to span a road, and usually standing alone, unconnected to other buildings. In its simplest form, a triumphal ...

.

Hypogeum

The hypogeum

A hypogeum or hypogaeum ( ; plural hypogea or hypogaea; literally meaning "underground") is an underground temple or tomb.

Hypogea will often contain niches for cremated human remains or loculi for buried remains. Occasionally tombs of th ...

is a half-buried edifice from the 3rd century. It was erected in the middle of the oldest necropolis, which was excavated in 1913. The hypogeum was designed to house funeral urns in small niches in the walls; at the time of its discovery, it contained sarcophagi

A sarcophagus (: sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a coffin, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Greek σάρξ ' meaning "flesh", and φ� ...

, which suggests that it was in use for a long time.

Political monuments

Triumphal arches

Dougga still contains two

Dougga still contains two triumphal arch

A triumphal arch is a free-standing monumental structure in the shape of an archway with one or more arched passageways, often designed to span a road, and usually standing alone, unconnected to other buildings. In its simplest form, a triumphal ...

es, which are in different states of disrepair.

Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; ; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through cursus honorum, the ...

's arch, which is heavily damaged, stands close to the mausoleum and on the route leading from Carthage to Théveste.[Mustapha Khanoussi, ''Dougga'', p. 70] It was erected in AD205.

Alexander Severus' arch, which dates from 222 to 235, is relatively well preserved, despite the loss of its upper elements. It is equidistant from the capitol and the Temple of Juno Caelestis. Its arcade is tall.

A third triumphal arch, dating from the Tetrarchy

The Tetrarchy was the system instituted by Roman emperor Diocletian in 293 AD to govern the ancient Roman Empire by dividing it between two emperors, the ''augusti'', and their junior colleagues and designated successors, the ''caesares''.

I ...

, has been completely lost.

Forum

The city forum, which is in size is small. It is better preserved in some places than others, because the construction of the Byzantine fort damaged a large section of it.

The city forum, which is in size is small. It is better preserved in some places than others, because the construction of the Byzantine fort damaged a large section of it.[Pierre Gros, ''L'architecture romaine du début du IIIe siècle à la fin du Haut-Empire'', tome 1, p. 228] The capitol, which stands on an area surrounded by portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cu ...

s, dominates its surroundings by virtue of its imposing appearance. The "square of the Rose of the Winds" (which is named after a decorative element) seems more like an esplanade leading to the Temple of Mercury, which stands on its northern side, than an open public space.curia

Curia (: curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally probably had wider powers, they came to meet ...

and a tribune for speeches probably also stood here.ex nihilo

(Latin, 'creation out of nothing') is the doctrine that matter is not eternal but had to be created by some divine creative act. It is a theistic answer to the question of how the universe came to exist. It is in contrast to ''creatio ex mate ...

''. This suggestion has been contradicted by the discovery of a sanctuary dedicated to Massinissa

Masinissa (''c.'' 238 BC – 148 BC), also spelled Massinissa, Massena and Massan, was an ancient Numidian king best known for leading a federation of Massylii Berber tribes during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), ultimately uniting th ...

amongst the substructures to the rear of the capitol.[Mustapha Khanoussi, ''Dougga'', p. 32]

Recreational facilities

Theatre

Roman theatres were a fundamental element of the monumental make-up of a city from the reign of

Roman theatres were a fundamental element of the monumental make-up of a city from the reign of Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

.

The theatre, which was built in AD168 or 169, is one of the best preserved examples in Roman Africa

Roman Africa or Roman North Africa is the culture of Roman Africans that developed from 146 BC, when the Roman Republic defeated Carthage and the Punic Wars ended, with subsequent institution of Roman Empire, Roman Imperial government, through th ...

. It could seat 3500 spectators, even though Dougga only had 5000 inhabitants. It was one of a series of imperial buildings constructed over the course of two centuries at Dougga which deviate from the classic "blueprint

A blueprint is a reproduction of a technical drawing or engineering drawing using a contact print process on light-sensitive sheets introduced by Sir John Herschel in 1842. The process allowed rapid and accurate production of an unlimited number ...

s" only inasmuch as they have been adapted to take account of the local terrain. Some minor adjustments have been made and the local architects had a certain freedom with regard to the ornamentation of the buildings.

A dedication engraved into the pediment

Pediments are a form of gable in classical architecture, usually of a triangular shape. Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the cornice (an elaborated lintel), or entablature if supported by columns.Summerson, 130 In an ...

of the stage

Stage, stages, or staging may refer to:

Arts and media Acting

* Stage (theatre), a space for the performance of theatrical productions

* Theatre, a branch of the performing arts, often referred to as "the stage"

* ''The Stage'', a weekly Brit ...

and on the portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cu ...

the dominates the city, recalls the building's commissioner, P. Marcius Quadratus, who "built tfor his homeland with his own denarii

The ''denarius'' (; : ''dēnāriī'', ) was the standard Roman silver coin from its introduction in the Second Punic War to the reign of Gordian III (AD 238–244), when it was gradually replaced by the ''antoninianus''. It continued to be mi ...

"; the dedication was celebrated with "scenic representations, distributions of life, a festival and athletic games".

The theater is still used for performances of classic theater, particularly during the festival of Dougga, and conservation work has been carried out on it.

Auditorium

The site known as the auditorium is an annex of the Temple of Liber

In Religion in ancient Rome, ancient Roman religion and Roman mythology, mythology, Liber ( , ; "the free one"), also known as Liber Pater ("the free Father"), was a god of viticulture and wine, male fertility and freedom. He was a patron de ...

, which probably served for the initiation of novices. Despite its modern appellation, the auditorium was not a site for spectacles; only its form suggests otherwise. It measures .

Circus

The city has a

The city has a circus

A circus is a company of performers who put on diverse entertainment shows that may include clowns, acrobats, trained animals, trapeze acts, musicians, dancers, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, magicians, ventriloquists, and unicy ...

designed for chariot racing

Chariot racing (, ''harmatodromía''; ) was one of the most popular Ancient Greece, ancient Greek, Roman Empire, Roman, and Byzantine Empire, Byzantine sports. In Greece, chariot racing played an essential role in aristocratic funeral games from ...

, but it is barely visible nowadays. Originally, the circus consisted of nothing more than a field; an inscription in the temple in honor of Caracalla's victory in Germany notes that the land was donated by the Gabinii in 214 and describes it as an ''ager qui appellatur circus'' (field that serves as a circus) ). In 225 though, the site was prepared and the circus was constructed. It was financed by the magistrates (duumviri

The duumviri (Latin for 'two men'), originally duoviri and also known in English as the duumvirs, were any of various joint magistrates of ancient Rome. Such pairs of Roman magistrates were appointed at various periods of Roman history both in ...

and aedile

Aedile ( , , from , "temple edifice") was an elected office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings () and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public orde ...

) after they had promised to do so following in response to a request from the entire population of the city. The circus was built to take the maximum possible advantage of the surrounding landscape, in reflection of an understandable need to limit costs in a medium-sized city with limited resources, but certainly also out of desire to finish the construction works as quickly as possible, given that magistrates' mandates were limited to one year. The construction was nonetheless expected to have "a certain magnitude";[Mustapha Khanoussi et Louis Maurin, ''Dougga. Fragments d'histoire. Choix d'inscriptions latines éditées, traduites et commentées (Ier-IVe siècles)'', p. 41] at long with a spina

Spina was an Etruscan port city, established by the end of the 6th century BCE, on the Adriatic at the ancient mouth of the Po.

Discovery

The site of Spina was lost until modern times, when drainage schemes in the delta of the Po River in 19 ...

, the circus is quite extraordinary in Roman Africa

Roman Africa or Roman North Africa is the culture of Roman Africans that developed from 146 BC, when the Roman Republic defeated Carthage and the Punic Wars ended, with subsequent institution of Roman Empire, Roman Imperial government, through th ...

. The circus marks Dougga out as one of the most important cities in the province, alongside Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

, Thysdrus, Leptis Magna

Leptis or Lepcis Magna, also known by #Names, other names in classical antiquity, antiquity, was a prominent city of the Carthaginian Empire and Roman Libya at the mouth of the Wadi Lebda in the Mediterranean.

Established as a Punic people, Puni ...

, Hadrumet et Utica.

Amphitheater

The question of whether there was an amphitheater

An amphitheatre ( U.S. English: amphitheater) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ('), meaning "place for vie ...

at Dougga has not been conclusively answered. Traditionally, a large elliptic depression to the northwest of the site has been interpreted as the site of an amphitheater. Archeologists have however become much more cautious on this subject.

Baths

Three

Three Roman baths

In ancient Rome, (from Greek , "hot") and (from Greek ) were facilities for bathing. usually refers to the large Roman Empire, imperial public bath, bath complexes, while were smaller-scale facilities, public or private, that existed i ...

have been completely excavated at Dougga; a fourth has so far only been partially uncovered. Of these four baths, one ("the bath of the house to the west of the Temple of Tellus") belongs to a private residence, two, the Aïn Doura bath and the bath known for a long time as the "Licinian bath", were, judging by their size, open to the public, while the nature of the last bath, the bath of the Cyclopses, is more difficult to interpret.

Bath of the Cyclopses

During the excavation of the Bath of the Cyclops

In Greek mythology and later Roman mythology, the Cyclopes ( ; , ''Kýklōpes'', "Circle-eyes" or "Round-eyes"; singular Cyclops ; , ''Kýklōps'') are giant one-eyed creatures. Three groups of Cyclopes can be distinguished. In Hesiod's ''Th ...

es, a mosaic

A mosaic () is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/Mortar (masonry), mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and ...

of ''cyclopses forging Jupiter's thunderbolts'' was uncovered. It is now on display at the Bardo National Museum, where several very well preserved latrines are also on display. The building has been dated to the 3rd century CE on the basis of a study of the mosaic.

The size of the building (its frigidarium

A ''frigidarium'' is one of the three main bath chambers of a Roman bath or ''thermae'', namely the cold room. It often contains a swimming pool.

The succession of bathing activities in the ''thermae'' is not known with certainty, but it is tho ...

is less than [ Yvon Thébert, ''Thermes romains d'Afrique du Nord et leur contexte méditerranéen'', éd. École française de Rome, Rome, 2003, p. 179]) has led some experts to believe that it was a private bath, but the identification of a domus

In ancient Rome, the ''domus'' (: ''domūs'', genitive: ''domūs'' or ''domī'') was the type of town house occupied by the upper classes and some wealthy freedmen during the Republican and Imperial eras. It was found in almost all the ma ...

in the immediate vicinity has proven difficult. The "trifolium villa" is quite distant, and the closest ruins are hard to identify as they have not been well preserved.

Antonian or Licinian Bath

The Antonian Bath, which dates from the 3rd century, was known as the Licinian Baths (after emperor ''Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus'') and has several storeys. Louis Poinssot's identification of the bath as dating to

The Antonian Bath, which dates from the 3rd century, was known as the Licinian Baths (after emperor ''Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus'') and has several storeys. Louis Poinssot's identification of the bath as dating to Gallienus

Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus (; – September 268) was Roman emperor with his father Valerian from 253 to 260 and alone from 260 to 268. He ruled during the Crisis of the Third Century that nearly caused the collapse of the empire. He ...

' reign on the basis of incomplete inscriptions and Dougga's prosperity at this time has been called into question by recent research, conducted in particular by Michel Christol. Christol has suggested that the bath dates from the reign of Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname Caracalla (; ), was Roman emperor from 198 to 217 AD, first serving as nominal co-emperor under his father and then r ...

; this thesis has since been confirmed by an analysis of inscriptions. Others have even suggested that the bath dates from the reign of the Severan dynasty

The Severan dynasty, sometimes called the Septimian dynasty, ruled the Roman Empire between 193 and 235.

It was founded by the emperor Septimius Severus () and Julia Domna, his wife, when Septimius emerged victorious from civil war of 193 - 197, ...

, because of a particularity which became common a century later in the west: the columns in the northwest peristyle

In ancient Ancient Greek architecture, Greek and Ancient Roman architecture, Roman architecture, a peristyle (; ) is a continuous porch formed by a row of columns surrounding the perimeter of a building or a courtyard. ''Tetrastoön'' () is a rare ...

feature dais

A dais or daïs ( or , American English also but sometimes considered nonstandard)[dais]

in the Random House Dictionary< ...

es bearing arches.[Gabriel Camps, « Dougga », ''L'Encyclopédie berbère'', p. 2526]

The bath was later used for the production of olive oil

Olive oil is a vegetable oil obtained by pressing whole olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea'', a traditional Tree fruit, tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin) and extracting the oil.

It is commonly used in cooking for frying foods, as a cond ...

at an unknown date.[Yvon Thébert, ''op. cit.'', p. 177]

The symmetrical building is medium-sized, with an area of excluding the palaestra

A palaestra ( or ; also (chiefly British) palestra; ) was any site of a Greek wrestling school in antiquity. Events requiring little space, such as boxing and wrestling, occurred there. ''Palaistrai'' functioned both independently and as a part ...

, of which are taken up by the frigidarium.[Yvon Thébert, ''op. cit.'', p. 178]

Aïn Doura Baths

In the immediate vicinity of Aïn Doura is a partially excavated complex that could turn out to be the largest bath in the city, the Aïn Doura Baths. On the basis of the mosaics that have been found here, it has been suggested that the bath dates from the end of the 2nd century or the start of the 3rd century, and that the mosaic décor was renewed in the 4th century CE.

In the immediate vicinity of Aïn Doura is a partially excavated complex that could turn out to be the largest bath in the city, the Aïn Doura Baths. On the basis of the mosaics that have been found here, it has been suggested that the bath dates from the end of the 2nd century or the start of the 3rd century, and that the mosaic décor was renewed in the 4th century CE.[Yvon Thébert, ''op. cit.'', p. 176]

The complex remains largely unexposed, but it seems, according to Yvon Thébert, that it has a symmetrical design, of which only a section of the cold rooms has been excavated.

The bath of the house to the west of the Temple of Tellus

This bath, measuring , which can be accessed from the house and from the street, was uncovered at the start of the 20th century. The archaeological analysis of the bath's relationship with the house in which it is located has led Thébert to suggest that it was a later addition to the original construction but he does not propose a date for this event.

Religious edifices

There is archaeological or epigraphic

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the wr ...

evidence for more than twenty temples at Dougga; a significant number for a small city. There are archaeological remains and inscriptions proving the existence of eleven temples, archaeological remains of a further eight, and inscriptions referring to another fourteen. This abundance of religious sites is the result in particular of the philanthropy of wealthy families.

Temple of Massinissa

The Temple of Massinissa

Masinissa (''c.'' 238 BC – 148 BC), also spelled Massinissa, Massena and Massan, was an ancient Numidian king best known for leading a federation of Massylii Berber tribes during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), ultimately uniting th ...

is located on the western flank of the capital. The first archaeologists believed that the remains of the temple were a monumental fountain

A fountain, from the Latin "fons" ( genitive "fontis"), meaning source or spring, is a decorative reservoir used for discharging water. It is also a structure that jets water into the air for a decorative or dramatic effect.

Fountains were o ...

, even though an inscription proving the existence of a sanctuary to the deceased Numidia

Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya. The polity was originally divided between ...

n king was discovered in 1904. This inscription has been dated to 139BC, during the reign of Micipsa

Micipsa ( Numidian: ''Mikiwsan''; , ; died BC) was the eldest legitimate son of Masinissa, the King of Numidia, a Berber kingdom in North Africa. Micipsa became the King of Numidia in 148 BC.

Early life

In 151 BC, Masinissa sent Micipsa and his ...

.

The remains are similar to those of the temple in Chemtouagora

The agora (; , romanized: ', meaning "market" in Modern Greek) was a central public space in ancient Ancient Greece, Greek polis, city-states. The literal meaning of the word "agora" is "gathering place" or "assembly". The agora was the center ...

. The stone remains found in this area seem to belong to several different structures; the exact location of the sanctuary is still open to debate.

Although it is believed that the sanctuary set Massinissa on par with a god, this is debated by some experts. Gsell believes that a temple to the king would reflect a continuation of eastern and Hellenic practices; Camps builds on this hypothesis, pointing out the lack of any antique sources testifying to anything more than simple expressions of respect by a people vis-à-vis its king. According to Camps, the temple is only a memorial, a site belonging to a funeral cult. Its construction ten years into Micipsa

Micipsa ( Numidian: ''Mikiwsan''; , ; died BC) was the eldest legitimate son of Masinissa, the King of Numidia, a Berber kingdom in North Africa. Micipsa became the King of Numidia in 148 BC.

Early life

In 151 BC, Masinissa sent Micipsa and his ...

's reign can be explained by its political symbolism: Micipsa, sole ruler after the death of his brothers Gulussa

Gulussa was the second legitimate son of Masinissa. Gulussa became the King of Numidia along with his two brothers around 148 BC and reigned as part of a triumvirate for about three years.

Biography

In 148 BC, Masinissa, feeling that he was ...

and Mastanabal

Mastanabal (Numidian: MSTNB; , ) was one of three legitimate sons of Masinissa, the King of Numidia, a Berber kingdom in, present day Algeria, North Africa. The three brothers were appointed by Scipio Aemilianus Africanus to rule Numidia after Ma ...

, was affirming the unity of his kingdom around the person of the king.

The Capitol

The Capitol is a Roman temple from the 2nd century, principally dedicated to Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

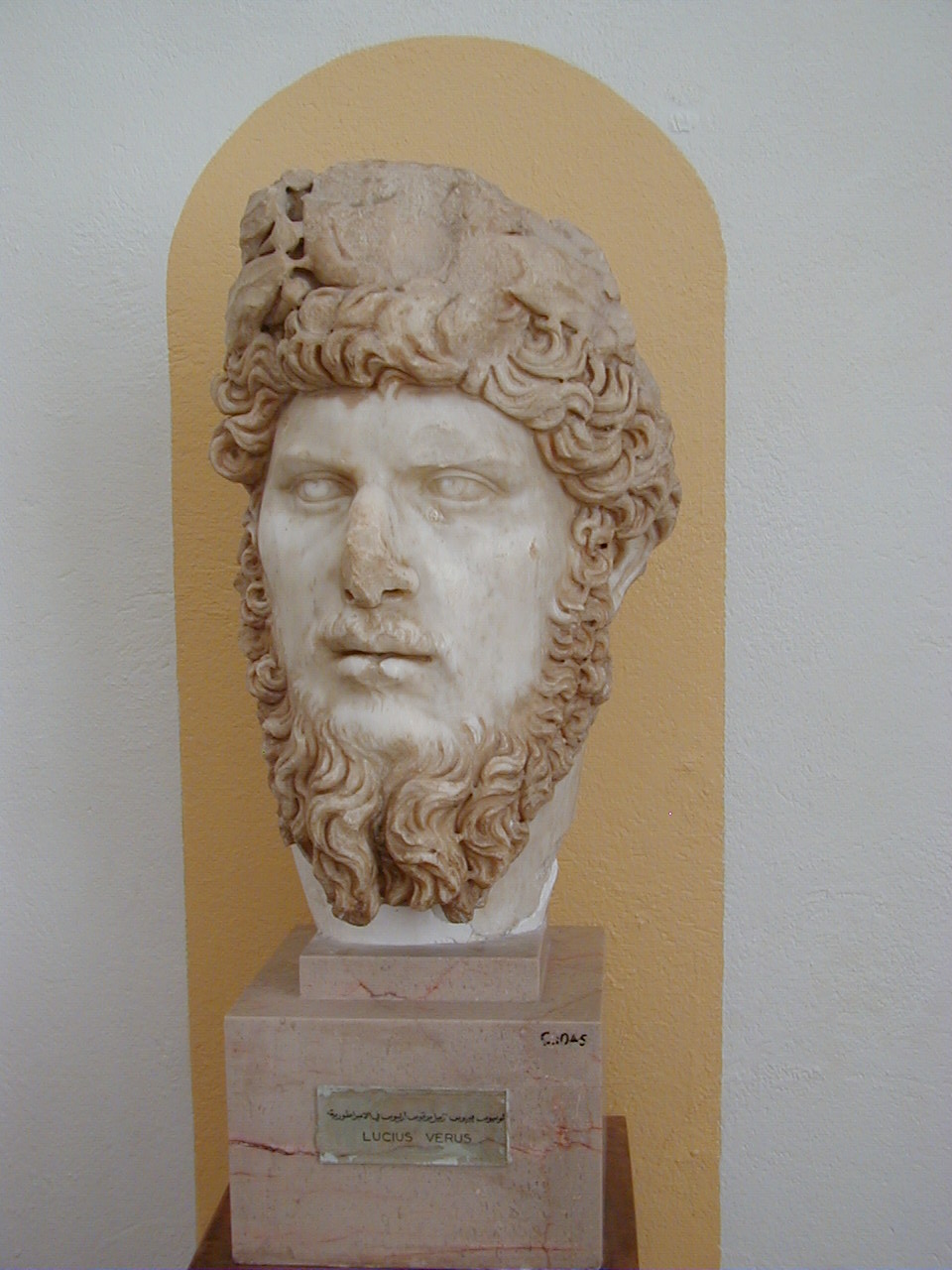

's protective triad: Jupiter Best and Greatest ('), Juno the Queen ('), and Minerva the August ('). It has a secondary dedication to the wellbeing of the emperors Lucius Verus

Lucius Aurelius Verus (; 15 December 130 – 23 January 169) was Roman emperor from 161 until his death in 169, alongside his adoptive brother Marcus Aurelius. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. Verus' succession together with Ma ...

and Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus ( ; ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 and a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors ...

; judging by this reference, the Capitol must have been completed in AD166-167.

Thomas d'Arcos identified the Capitol as a temple of Jupiter in the 17th century. It was the object of further research at the end of the 19th century, led in particular by the doctor Louis Carton in 1893. The walls, executed in '' opus africanum'' style, and the entablature

An entablature (; nativization of Italian , from "in" and "table") is the superstructure of moldings and bands which lies horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Entablatures are major elements of classical architecture, and ...

of the portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cu ...

were restored between 1903 and 1910. Claude Poinssot discovered a crypt

A crypt (from Greek κρύπτη (kryptē) ''wikt:crypta#Latin, crypta'' "Burial vault (tomb), vault") is a stone chamber beneath the floor of a church or other building. It typically contains coffins, Sarcophagus, sarcophagi, or Relic, religiou ...

beneath the cella

In Classical architecture, a or naos () is the inner chamber of an ancient Greek or Roman temple. Its enclosure within walls has given rise to extended meanings: of a hermit's or monk's cell, and (since the 17th century) of a biological cell ...

in 1955. The most recent works were carried out by the Tunisian ''Institut national du patrimoine'' between 1994 and 1996.[Sophie Saint-Amans, ''op. cit.'', p. 283]

The Capitol is exceptionally well preserved, which is a consequence of its inclusion in the Byzantine fortification. A series of eleven stairs lead up to the front portico. The temple front's Corinthian columns are tall, on top of which is the perfectly preserved pediment

Pediments are a form of gable in classical architecture, usually of a triangular shape. Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the cornice (an elaborated lintel), or entablature if supported by columns.Summerson, 130 In an ...

. The pediment bears a depiction of emperor Antoninus Pius

Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius (; ; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from AD 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatorial family, Antoninus held var ...

's elevation to godhood. The emperor is being carried by an eagle

Eagle is the common name for the golden eagle, bald eagle, and other birds of prey in the family of the Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of Genus, genera, some of which are closely related. True eagles comprise the genus ''Aquila ( ...

.North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, which Gros explains as a consequence of the greater proximity of the imperial cult

An imperial cult is a form of state religion in which an emperor or a dynasty of emperors (or rulers of another title) are worshipped as demigods or deities. "Cult (religious practice), Cult" here is used to mean "worship", not in the modern pejor ...

and the cult of Jupiter.

Near the Capitol are the "square of the Rose of the Winds"which is named after a compass rose that is engraved on the floorand the remains of the Byzantine citadel, which reused a section of the ruins after the city's decline.

Image:P6212479 dougga.jpg, Antoninus Pius' elevation to godhood

Image:Dougga-ninxol.JPG, Interior of the cella with the alcoves designed to hold statues

Image:Dougga capitole 1900.jpg, The Capitol at the start of the 20th century

File:The Capital Dougga Tunisia 2006.jpg, The front of the Capitol in 2006

File:Temple aux six colonnes 03.jpg, The Capitol at night

Temple of Mercury

The Temple of Mercury is also dedicated to Tellus. It faces towards the market; between the two lies the "square of the Rose of the Winds". The temple is largely in ruins. It has three

The Temple of Mercury is also dedicated to Tellus. It faces towards the market; between the two lies the "square of the Rose of the Winds". The temple is largely in ruins. It has three cella

In Classical architecture, a or naos () is the inner chamber of an ancient Greek or Roman temple. Its enclosure within walls has given rise to extended meanings: of a hermit's or monk's cell, and (since the 17th century) of a biological cell ...