The Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 AD) was a major uprising by the

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

of

Judaea against the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, marking the final and most devastating of the

Jewish–Roman wars

The Jewish–Roman wars were a series of large-scale revolts by the Jews of Judaea against the Roman Empire between 66 and 135 CE. The conflict was driven by Jewish aspirations to restore the political independence lost when Rome conquer ...

. Led by

Simon bar Kokhba, the rebels succeeded in establishing an independent Jewish state that lasted for several years. The revolt was ultimately crushed by the Romans, resulting in the near-depopulation of

Judea

Judea or Judaea (; ; , ; ) is a mountainous region of the Levant. Traditionally dominated by the city of Jerusalem, it is now part of Palestine and Israel. The name's usage is historic, having been used in antiquity and still into the pres ...

through large-scale killings, mass enslavement, and the displacement of many Jews from the region.

Resentment toward Roman rule in Judaea and nationalistic aspirations remained high following the

destruction of Jerusalem during the

First Jewish Revolt in 70 AD. The immediate triggers of the Bar Kokhba revolt included Emperor

Hadrian

Hadrian ( ; ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic peoples, Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, Aelia '' ...

's decision to build ''

Aelia Capitolina

Aelia Capitolina (Latin: ''Colonia Aelia Capitolina'' ɔˈloːni.a ˈae̯li.a kapɪtoːˈliːna was a Roman colony founded during the Roman emperor Hadrian's visit to Judaea in 129/130 CE. It was founded on the ruins of Jerusalem, which had b ...

''—a

Roman colony

A Roman (: ) was originally a settlement of Roman citizens, establishing a Roman outpost in federated or conquered territory, for the purpose of securing it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It ...

dedicated to

Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

—on the ruins of Jerusalem, extinguishing hopes for the Temple's reconstruction, as well as a possible ban on

circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. T ...

, a central Jewish practice. Unlike the earlier revolt, the rebels were well-prepared, using

guerrilla tactics

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

and

underground hideouts embedded in their villages. Initially, the rebels achieved considerable success, driving Roman forces out of much of the province. Simon bar Kokhba was declared ''"

nasi"'' (prince) of Israel, and the rebels established a full administration, issuing their own

weights and

coinage. Contemporary documents celebrated a new era of "the redemption of Israel," and coinage carried similar slogans, dated according to the years of independence.

The tide turned when Hadrian appointed one of Rome’s most skilled generals,

Sextus Julius Severus, to lead the campaign, supported by six full

legions,

auxiliary

Auxiliary may refer to:

In language

* Auxiliary language (disambiguation)

* Auxiliary verb

In military and law enforcement

* Auxiliary police

* Auxiliaries, civilians or quasi-military personnel who provide support of some kind to a military se ...

units, and reinforcements from up to six additional legions. Hadrian himself also participated in directing operations for a time. The Romans launched a broad offensive across Judea, systematically devastating towns, villages, and the countryside. In 135 AD, the fortified stronghold of

Betar

The Betar Movement (), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionism, Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. It was one of several right-wing youth movements tha ...

, the rebels' last center of resistance, was captured and destroyed, and Simon bar Kokhba was killed, effectively ending the revolt. In its final stages, many

sought refuge in natural caves, particularly in the

Judaean Desert

The Judaean Desert or Judean Desert (, ) is a desert in the West Bank and Israel that stretches east of the ridge of the Judaean Mountains and in their rain shadow, so east of Jerusalem, and descends to the Dead Sea. Under the name El-Bariyah, ...

, but Roman troops besieged these hideouts, cutting off supplies and killing, starving or capturing those inside.

The consequences of the revolt were devastating for the Jewish population of Judaea. Ancient and contemporary sources estimate that hundreds of thousands were killed, while many others were enslaved or exiled. The region of Judea was largely depopulated, and Jewish life shifted to

Galilee

Galilee (; ; ; ) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon consisting of two parts: the Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and the Lower Galilee (, ; , ).

''Galilee'' encompasses the area north of the Mount Carmel-Mount Gilboa ridge and ...

and the expanding

diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of birth, place of origin. The word is used in reference to people who identify with a specific geographic location, but currently resi ...

. Messianic hopes became more abstract, and

rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism (), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, Rabbanite Judaism, or Talmudic Judaism, is rooted in the many forms of Judaism that coexisted and together formed Second Temple Judaism in the land of Israel, giving birth to classical rabb ...

adopted a cautious, non-revolutionary stance. The divide between Judaism and

early Christianity

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the History of Christianity, historical era of the Christianity, Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Spread of Christianity, Christian ...

also deepened. The Romans imposed harsh religious prohibitions, including bans on circumcision and

Sabbath observance, expelled Jews from Jerusalem, restricted their entry to one annual visit, and repopulated the city with foreigners.

Background

The Bar Kokhba revolt was the last of three

Jewish revolts against Rome fought within a span of approximately 60 years. It was preceded by the

First Jewish–Roman War

The First Jewish–Roman War (66–74 CE), also known as the Great Jewish Revolt, the First Jewish Revolt, the War of Destruction, or the Jewish War, was the first of three major Jewish rebellions against the Roman Empire. Fought in the prov ...

(66–73) and the

Diaspora Revolt (115–117). These revolts were brutally suppressed by Rome, resulting in the destruction of numerous Jewish communities, including

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, the national and religious center of the Jewish people. Hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed, many others were exiled or sold into slavery, and the status of Jews and Judaism throughout the Roman Empire was significantly diminished.

In 6 CE, Judaea transitioned from a

client kingdom of Rome to a directly ruled

Roman province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as Roman g ...

. For the next six decades, aside from a brief period under another client king,

Herod Agrippa I, the province was governed by successive

Roman officials. The Jewish population grew increasingly resentful due to mismanagement, corruption, and the incompetence of these governors. Their rule was often marked by acts of brutality and religious insensitivity, which further inflamed local tensions. Escalating tensions emerged from ethnic, religious, and territorial conflicts with neighboring populations, worsened by widening economic inequalities. Meanwhile, memories of the

Maccabean revolt

The Maccabean Revolt () was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167 to 160 BCE and ended with the Seleucids in control of ...

and the period of independence under the

Hasmoneans fueled Jewish nationalist aspirations for liberation from Roman rule. In 66 CE, unrest in Caesarea, followed by clashes in Jerusalem, sparked the outbreak of an open Jewish revolt—the

First Jewish–Roman War

The First Jewish–Roman War (66–74 CE), also known as the Great Jewish Revolt, the First Jewish Revolt, the War of Destruction, or the Jewish War, was the first of three major Jewish rebellions against the Roman Empire. Fought in the prov ...

. The rebellion was systematically subdued by the Romans under the command of

Vespasian

Vespasian (; ; 17 November AD 9 – 23 June 79) was Roman emperor from 69 to 79. The last emperor to reign in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty, which ruled the Empire for 27 years. His fiscal reforms and consolida ...

and later his son

Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September AD 81) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death, becoming the first Roman emperor ever to succeed h ...

. Jerusalem was razed, and the

Second Temple

The Second Temple () was the Temple in Jerusalem that replaced Solomon's Temple, which was destroyed during the Siege of Jerusalem (587 BC), Babylonian siege of Jerusalem in 587 BCE. It was constructed around 516 BCE and later enhanced by Herod ...

was destroyed.

Following the war, Judaea underwent administrative reorganization. A senatorial-rank

legate was appointed as governor, overseeing the province. Under his command,

Legio X Fretensis

Legio X Fretensis ("Tenth legion of the Strait") was a legion of the Imperial Roman army. It was founded by the young Gaius Octavius (later to become Augustus Caesar) in 41/40 BC to fight during the period of civil war that started the dissolu ...

—which had participated in the war—was permanently stationed in the province, establishing its main base in the ruins of Jerusalem. To further secure the region, the regions of Judea and Idumea were designated as a military zone, administered directly by officers of the legion. The province's status changed again in the 110s CE when it was placed under a

proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a Roman consul, consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military ...

, a higher-ranking official. Around this time, an additional legion,

Legio VI Ferrata

Legio VI Ferrata ("Sixth Ironclad Legion") was a Roman legion, legion of the Imperial Roman army. In 30 BC it became part of the emperor Augustus's standing army. It continued in existence into the 4th century. A ''Legio VI'' fought in the Roman ...

, was stationed in the province, with its main base at

Legio (Kefar Othnai). The increased military presence was accompanied by efforts to establish and reinforce a more loyal population in the province, including through the settlement of discharged soldiers.

In 115 CE, during

Trajan

Trajan ( ; born Marcus Ulpius Traianus, 18 September 53) was a Roman emperor from AD 98 to 117, remembered as the second of the Five Good Emperors of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was a philanthropic ruler and a successful soldier ...

's reign, another large-scale Jewish insurrection, known as the

Diaspora Revolt, erupted, spreading across Jewish communities in

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

,

Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika (, , after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between the 16th and 25th meridians east, including the Kufra District. The coastal region, als ...

,

Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, and

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, and continuing until 117. The final stages of this conflict, known as the

Kitos War

The Kitos War took place from 116 to 118, as part of the Second Jewish–Roman War. Ancient Jewish sources date it to 52 years after the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73) and 16 years before the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136). Like other conflic ...

, appear to have led to unrest spilling over into Judaea. Mismanagement of the province in the early 2nd century likely contributed to the conditions that set the stage for the Bar Kokhba revolt, as governors enforcing anti-Jewish policies further destabilized an already volatile region.

Sources

Reconstructing the events of the Bar Kokhba revolt poses a challenge, as the historical sources are limited and fragmentary. Unlike the First Jewish–Roman war, which was chronicled in detail by

Flavius Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a History of the Jews in the Roman Empire, Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing ''The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Judaea ...

, the Bar Kokhba revolt had no surviving contemporary historian. Historians rely on a limited range of literary sources, each with distinct objectives, levels of reliability, and dates of composition, leaving many crucial questions unresolved.

Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history of ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

, a Roman statesman and historian of Greek background writing in the early 3rd-century AD, offers the most detailed surviving Roman account of the revolt, found in Book 69 of his ''Roman History''.

Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history of ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

, Translation by Earnest Cary. ''Roman History'', book 69, 12.1–14.3. Loeb Classical Library

The Loeb Classical Library (LCL; named after James Loeb; , ) is a monographic series of books originally published by Heinemann and since 1934 by Harvard University Press. It has bilingual editions of ancient Greek and Latin literature, ...

, 9 volumes, Greek texts and facing English translation: Harvard University Press, 1914 thru 1927. Online in LacusCurtius

LacusCurtius is the ancient Graeco-Roman part of a large history website, hosted as of March 2025 on a server at the University of Chicago. Starting in 1995, as of January 2004 it gave "access to more than 594 photos, 559 drawings and engravings, ...

br>

and livius.or

. Book scan in Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American 501(c)(3) organization, non-profit organization founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle that runs a digital library website, archive.org. It provides free access to collections of digitized media including web ...

br>

The original text, however, survives only through an 11th-century

epitome

An epitome (; , from ἐπιτέμνειν ''epitemnein'' meaning "to cut short") is a summary or miniature form, or an instance that represents a larger reality, also used as a synonym for embodiment. Epitomacy represents "to the degree of." A ...

by

John Xiphilinus, whose abridgments are generally considered faithful to Dio's language and content. Dio's account of the revolt presents a military viewpoint and includes descriptions of underground hideouts used by Jewish rebels—though he does not mention Bar Kokhba by name. He notes the global cohesion of the Jewish population and some level of non-Jewish participation. His narrative provides valuable insight into the revolt's scale and devastation, including losses sustained by both sides.

Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

, a 4th-century Christian bishop and historian from

Caesarea Maritima

Caesarea () also Caesarea Maritima, Caesarea Palaestinae or Caesarea Stratonis, was an ancient and medieval port city on the coast of the eastern Mediterranean, and later a small fishing village. It was the capital of Judaea (Roman province), ...

, offers a Late Antique Christian interpretation of the revolt. Though writing with a theological agenda—depicting Jewish uprisings as

divine punishment for the

crucifixion of Jesus

The crucifixion of Jesus was the death of Jesus by being crucifixion, nailed to a cross.The instrument of Jesus' crucifixion, instrument of crucifixion is taken to be an upright wooden beam to which was added a transverse wooden beam, thus f ...

—he had access to valuable sources, including the library of

Pamphilus, church archives in Aelia Capitolina, the works of earlier Christian writers such as

Aristo of Pella and

Julius Africanus, and possibly pagan texts. His account includes key details absent from Dio—whom he likely neither knew nor used as a source—such as naming

Tineius Rufus as the Roman governor, identifying Bar Kokhba (as '

''Barchochebas'',' interpreted as 'son of a star'), and citing Bethar (Beththera''

') as the site of the final siege. While shaped by a Christian

supersessionist worldview, his geographical proximity, access to now-lost materials, and possible use of Jewish traditions make his writings a significant—if ideologically filtered—source for the revolt.

The ''

Historia Augusta

The ''Historia Augusta'' (English: ''Augustan History'') is a late Roman collection of biographies, written in Latin, of the Roman emperors, their junior colleagues, Caesar (title), designated heirs and Roman usurper, usurpers from 117 to 284. S ...

'', a late Roman collection of imperial biographies compiled in the 4th century AD, devotes only a single sentence to the revolt in its ''Life of Hadrian'', briefly noting one of its possible causes. This portion of the work is believed to rely on relatively reliable

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

sources from the

Severan

The Severan dynasty, sometimes called the Septimian dynasty, ruled the Roman Empire between 193 and 235.

It was founded by the emperor Septimius Severus () and Julia Domna, his wife, when Septimius emerged victorious from civil war of 193 - 197, ...

period (193–235 ), making it roughly contemporary with Dio's account.

Jewish historical references to the Bar Kokhba revolt are primarily found in

rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire corpus of works authored by rabbis throughout Jewish history. The term typically refers to literature from the Talmudic era (70–640 CE), as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic ...

, including the ''

Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; , from the verb ''šānā'', "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah. Having been collected in the 3rd century CE, it is ...

'',

''Talmuds'', and other works compiled in the subsequent centuries. While these texts were not intended as historical chronicles—most were composed with a focus on Jewish law (''

halakhah'')—they nonetheless contain narrative sections (''

aggadah

Aggadah (, or ; ; 'tales', 'legend', 'lore') is the non-legalistic exegesis which appears in the classical rabbinic literature of Judaism, particularly the Talmud and Midrash. In general, Aggadah is a compendium of rabbinic texts that incorporat ...

'') that preserve anecdotes, teachings, legal rulings, and reflections. These passages, though often shaped by theological and didactic aims, offer valuable insights into the revolt and its broader historical context. While many texts were written down generations after the revolt and contain legendary elements, modern scholars acknowledge that they preserve genuine historical traditions, especially when corroborated by archaeology and other sources. Many of the stories associated with the revolt, such as those about Betar's fall, indeed appear in ''Aggadaic'' material, particularly in the

Babylonian Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the centerpiece of Jewi ...

(e.g., ''Gittin 55b–58a''),

Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

(''Taanith iv 8, 68d–69b''), and ''

midrashim

''Midrash'' (;["midrash"]

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

'' like ''

Lamentations Rabbah

The Midrash on Lamentations () is a midrashic commentary to the Book of Lamentations.

It is one of the oldest works of midrash, along with Genesis Rabbah and the '' Pesikta de-Rav Kahana''.

Names

The midrash is quoted, perhaps for the first ti ...

''. These passages provide insight into how the Jewish people experienced and interpreted the events of the time. They include a variety of material—stories, rulings, and anecdotes—that shed light on the revolt and its aftermath. One of the most distinctive contributions of rabbinic literature is its portrayal of Bar Kokhba: it is the only source to explicitly describe him as a messianic figure and preserves two conflicting accounts of his death. Rabbinic texts also report Roman executions of Jewish sages and episodes of religious repression following the revolt. Some accounts present the revolt and its leaders in a sympathetic or even heroic light, though many others offer a more critical or negative evaluation.

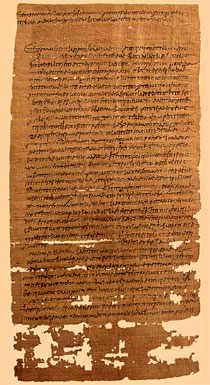

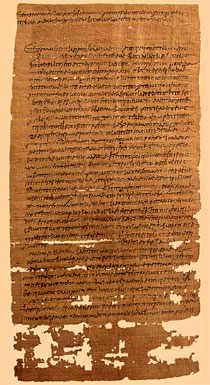

Archaeological discoveries, beginning in 1952, have transformed our understanding of the revolt. Chief among them are papyri discovered in the Cave of Letters, including legal documents and correspondence between Bar Kokhba and his subordinates. Among roughly 30 surviving texts, three are in Greek, and the rest are in Hebrew and Aramaic. These documents offer direct insight into the rebels' administration, military organization, religious practices, and internal challenges, though they provide limited information about the military course of the revolt itself. Additional evidence comes from coins minted by the rebels, which help estimate the revolt's duration and reveal its goals: the restoration of Jewish independence and the rebuilding of the Temple.

Causes

The causes of the Bar Kokhba revolt have been debated among historians, with two main ancient sources providing differing explanations. Cassius Dio attributes the revolt to Jewish anger over Emperor

Hadrian

Hadrian ( ; ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic peoples, Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, Aelia '' ...

's decision to rebuild Jerusalem as a

Roman colony

A Roman (: ) was originally a settlement of Roman citizens, establishing a Roman outpost in federated or conquered territory, for the purpose of securing it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It ...

,

Aelia Capitolina

Aelia Capitolina (Latin: ''Colonia Aelia Capitolina'' ɔˈloːni.a ˈae̯li.a kapɪtoːˈliːna was a Roman colony founded during the Roman emperor Hadrian's visit to Judaea in 129/130 CE. It was founded on the ruins of Jerusalem, which had b ...

. The ''Historia Augusta'' suggests that the immediate trigger for the uprising was a Roman ban on

circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. T ...

, a central Jewish practice. The prevailing scholarly consensus recognizes a combination of these causes in explaining the outbreak of the revolt.

Establishment of Aelia Capitolina

In 129–130 AD, Hadrian toured the eastern provinces, promoting Hellenistic culture. The region's non-Jewish population honored him with new city names and festivals. During his visit of Judaea, he decided to rebuild the destroyed Jerusalem as a

Roman colony

A Roman (: ) was originally a settlement of Roman citizens, establishing a Roman outpost in federated or conquered territory, for the purpose of securing it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It ...

named

Aelia Capitolina

Aelia Capitolina (Latin: ''Colonia Aelia Capitolina'' ɔˈloːni.a ˈae̯li.a kapɪtoːˈliːna was a Roman colony founded during the Roman emperor Hadrian's visit to Judaea in 129/130 CE. It was founded on the ruins of Jerusalem, which had b ...

, after his family name (''Publius Aelius Hadrianus'') and in honor of Capitoline

Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

. This decision enraged the Jews, extinguishing their hopes of ever rebuilding Jerusalem and the Temple.

Historians once debated whether Aelia Capitolina's foundation caused the revolt or followed it as punishment.

Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history of ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

wrote that Hadrian founded Aelia Capitolina on Jerusalem’s ruins and erected a temple to Jupiter on the Temple Mount. In his account, this caused "a long and serious war, since the Jews objected to having gentiles settled in their city and foreign cults established."

Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

, however, described the colony's foundation as a punitive measure after the uprising. He wrote: "when the city had been emptied of the Jewish nation and had suffered the total destruction of its ancient inhabitants, it was colonized by a different race, and the Roman city which subsequently arose changed its name." The debate was settled by the discovery of Aelia Capitolina coins at sites abandoned before the uprising and buried alongside Bar Kokhba coins, indicating that they were already in circulation during the revolt, thus confirming Dio's version that the colony's founding preceded the conflict.

One interpretation involves the visit in 130 of Hadrian to the ruins of the

Temple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a place of worship, a building used for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. By convention, the specially built places of worship of some religions are commonly called "temples" in Engli ...

. At first sympathetic towards the Jews, Hadrian promised to rebuild the Temple, but the Jews felt betrayed when they found out that he intended to build a temple dedicated to Jupiter.

A rabbinic version of this story, seemingly set during Hadrian's reign, suggests that the Romans did plan to rebuild the Temple, but a malevolent

Samaritan

Samaritans (; ; ; ), are an ethnoreligious group originating from the Hebrews and Israelites of the ancient Near East. They are indigenous to Samaria, a historical region of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah that ...

convinced them to abandon the idea, claiming that the Jews would rebel once their city was restored.

The reference to a malevolent Samaritan, however, is a common

motif in Jewish literature.

this account might reveal the Jewish sense of disappointment due to the Romans not rebuilding the Temple.

An additional legion, the

VI ''Ferrata'', arrived in the province to maintain order. Works on Aelia Capitolina commenced in 131. Consul

Quintus Tineius Rufus performed the foundation ceremony which involved ploughing over the designated city limits. "Ploughing up the Temple", seen as a religious offence, turned many Jews against the Roman authorities. The Romans issued a coin inscribed ''Aelia Capitolina''.

Mary E. Smallwood writes that the foundation of Aelia Capitolina was likely "an attempt to combat resurgent Jewish nationalism" by secularizing the Jewish holy capital. According to

Martin Goodman, Hadrian established the colony as a "final solution for Jewish rebelliousness," aiming to permanently erase the city and prevent future rebellions among Jews in Judaea or in diaspora communities. The foundation of a Roman colony—rather than a Hellenistic

polis

Polis (: poleis) means 'city' in Ancient Greek. The ancient word ''polis'' had socio-political connotations not possessed by modern usage. For example, Modern Greek πόλη (polē) is located within a (''khôra''), "country", which is a πατ ...

—was designed to transplant foreign populations and impose Roman religious practices. While Hadrian founded many cities, this case was unique in that it was "not to flatter but to suppress the natives."

Ban on circumcision

Another oft-cited cause for the revolt is a possible ban on the Jewish practice of circumcision (''

Brit milah

The ''brit milah'' (, , ; "Covenant (religion), covenant of circumcision") or ''bris'' (, ) is Religion and circumcision, the ceremony of circumcision in Judaism and Samaritanism, during which the foreskin is surgically removed. According to t ...

''). The ''Historia Augusta'' claims that Hadrian prohibited the Jews from circumcising their sons (decried as ''mutilare genitalia'', "mutilating the genitals"), and that this edit precipitated the Jewish revolt. The imperial biography states: "in their impetuosity the Jews also began a war, as they had been forbidden to mutilate their genitals." However, the reliability of this account is questionable—the ''Historia Augusta'' was written centuries after the events and is prone to anecdote and error. Scholars have long debated the timing of the ban in relation to the revolt, with some arguing that the ban was introduced during or immediately after the uprising, rather than preceding it. It is known that in the 140s, and before 155,

Antoninus Pius

Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius (; ; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from AD 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatorial family, Antoninus held var ...

mitigated the ban on circumcision by allowing Jews by birth to circumcise legally, while prohibiting the practice for non-Jews. However, it remains unclear when the original ban was first instituted.

If the prohibition existed, some scholars suggest Hadrian, as a Hellenist, recognized circumcision as bodily mutilation.

[Christopher Mackay]

''Ancient Rome a Military and Political History''

Cambridge University Press 2007 p. 230 E. Mary Smallwood argues he imposed a universal ban, later relaxed by

Antoninus Pius

Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius (; ; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from AD 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatorial family, Antoninus held var ...

, who is known to have granted Jews an exemption. She cites Talmudic passages implying the ban preceded the revolt, including one where Rabbi

Eliezer ben Hurcanus

Eliezer ben Hurcanus (or Hyrcanus) () was one of the most prominent Judean ''tannaitic'' Sages of 1st- and 2nd-century Judaism, a disciple of Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai, Avot of Rabbi Natan 14:5 and a colleague of Gamaliel II (whose sister, ...

permitted hiding circumcision knives in peril. Other scholars such as

Peter Schäfer

Peter Schäfer (born 29 June 1943, Mülheim an der Ruhr, North Rhine-Westphalia) is a prolific German scholar of ancient religious studies, who has made contributions to the field of ancient Judaism and early Christianity through monographs, co-e ...

and Joseph Geiger doubt an antecedent ban, suggesting that Roman laws against genital mutilation were meant to stop the

castration

Castration is any action, surgery, surgical, chemical substance, chemical, or otherwise, by which a male loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical cas ...

of slaves, not Jewish circumcision, and that any prohibition on circumcision may have been imposed after the revolt as retribution.

Internal factors

In addition to the immediate causes, broader factors likely contributed to an atmosphere ripe for revolt. One such factor may have been eschatological anticipation: nearly sixty years had passed since the destruction of the Second Temple, and some may have expected divine intervention as the symbolic seventy-year mark approached. This expectation was rooted in the precedent of the

Babylonian exile

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile was the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were forcibly relocated to Babylonia by the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The deportations occurre ...

, which lasted seventy years following the destruction of the First Temple and culminated in its rebuilding—fulfilling a biblical prophecy attributed

Jeremiah

Jeremiah ( – ), also called Jeremias, was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible. According to Jewish tradition, Jeremiah authored the Book of Jeremiah, book that bears his name, the Books of Kings, and the Book of Lamentations, with t ...

. When redemption failed to materialize, growing frustration may have fueled a readiness to rebel.

Other causes thought to have contributed to the revolt include: changes in administrative law, the widespread presence of legally-privileged

Roman citizens

Citizenship in ancient Rome () was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cu ...

, alterations in agricultural practice with a shift from landowning to sharecropping, the impact of a possible period of economic decline, and an upsurge of nationalism, the latter influenced by the

Diaspora Revolt. Economic hardship following the First Jewish Revolt may have also played a role, as many Jews lost their land to Roman veterans and collaborators, creating a dispossessed class that likely became a core source of support for Bar Kokhba. The charismatic personality of Bar Kokhba himself is also thought to have been a major cause of the revolt.

Leadership

The revolt was led by

bar Kokhba

Simon bar Kokhba ( ) or Simon bar Koseba ( ), commonly referred to simply as Bar Kokhba, was a Jewish military leader in Judaea (Roman province), Judea. He lent his name to the Bar Kokhba revolt, which he initiated against the Roman Empire in 1 ...

, a charismatic leader whose support was likely driven by his personal qualities and abilities, including his

charisma

() is a personal quality of magnetic charm, persuasion, or appeal.

In the fields of sociology and political science, psychology, and management, the term ''charismatic'' describes a type of leadership.

In Christian theology, the term ''chari ...

. According to rabbinic literature,

Rabbi Akiva

Akiva ben Joseph (Mishnaic Hebrew: ; – 28 September 135 CE), also known as Rabbi Akiva (), was a leading Jewish scholar and sage, a '' tanna'' of the latter part of the first century and the beginning of the second. Rabbi Akiva was a leadin ...

, a leading sage, recognized Bar Kokhba as the messiah. However, this view was challenged by the contemporary rabbi

Yohanan ben Torta, who, according to the Jerusalem Talmud, retorted to Akiva, "Grass will grow on your cheeks, and the Messiah will not yet have come!"

The name ' does not appear in the

Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

but is found in early ecclesiastical sources. Previously, historians debated whether ', meaning "son of the star", was his original name, with some suggesting that the name ' (meaning "son of disappointment" or "son of lies" in this interpretation), found in rabbinic texts, was a later, derogatory term. However, documents discovered in the Judaean Desert in the 1950s revealed that his original name was . This name is believed to be derived from his place of origin. The title was likely bestowed upon him by Rabbi Akiva, based on the "

Star Prophecy" found in

Numbers

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The most basic examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers can ...

: "A star () rises from Jacob."

Seventeen letters discovered in the Judaean Desert offer insight into Bar Kokhba's personality. The documents portray him as a demanding and involved military leader, personally overseeing matters of discipline and logistics. His uncompromising style is evident in sharp threats and rebukes directed at his subordinate officers. The letters also reflect a strong sense of religious devotion, including observance of

Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; , , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazi Hebrew, Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the seven-day week, week—i.e., Friday prayer, Friday–Saturday. On this day, religious Jews ...

and the laws of

tithes

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Modern tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash, cheques or via onli ...

and

offerings. In one letter, Bar Kokhba instructs his men to procure (palm branches) and (citrons) to fulfill the mitzvah of the

Four Species during the festival of

Sukkot

Sukkot, also known as the Feast of Tabernacles or Feast of Booths, is a Torah-commanded Jewish holiday celebrated for seven days, beginning on the 15th day of the month of Tishrei. It is one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals on which Israelite ...

.

Rabbinic literature, reflecting elements of

folk memory shaped over the two to three centuries following the revolt, portrays Bar Kokhba as a heroic and fearsome figure of immense strength and severity, whose death could only be brought about by divine intervention. He is said to have slain large numbers of Roman soldiers by throwing massive

catapult

A catapult is a ballistics, ballistic device used to launch a projectile at a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden rel ...

stones single-handedly at them. Rabbinic legend also recounts that he tested his soldiers by requiring them either to sever a finger or to uproot a cedar tree. However, according to rabbinic traditions, the true strength of the revolt lay not in Bar Kokhba’s physical might, but in the spiritual support of the sages; once that was lost following Bar Kokhba's killing of one of them, the rebellion collapsed.

Outbreak and strategy

The Bar Kokhba revolt and the establishment of the Bar Kokhba administration likely began in the summer of 132 AD. Simeon Bar Kokhba's forces waited for Hadrian to leave before launching the uprisings. Learning from the failures of the First Jewish Revolt, the Jews carefully planned the rebellion.

Cassius Dio reports that the insurgents avoided open battle, instead occupying strong natural positions reinforced with

underground hiding complexes, allowing them both refuge and concealed movement:

The Jews ..did not dare try conclusions with the Romans in the open field, but they occupied the advantageous positions in the country and strengthened them with mines and walls, in order that they might have places of refuge whenever they should be hard pressed, and might meet together unobserved underground; and they pierced these subterranean passages from above at intervals to let in air and light.

Archaeological evidence has confirmed Cassius Dio’s account of Jewish preparations for the Bar Kokhba revolt. Hundreds of underground hideout complexes have been identified across almost every populated area, with approximately 350 systems mapped within the ruins of 140 Jewish villages as of 2015.

NRG. 15 July 2015. These systems were extensively employed in the Judean Hills, the Judean Desert, and the northern Negev, with smaller concentrations in Galilee, Samaria, and the Jordan Valley. Many private houses were outfitted with underground chambers designed to exploit the narrowness of the passages for defensive purposes and ambushes. The interconnected cave networks served both as refuges for combatants and as shelters for their families.

Dio also states that the Jews manufactured their own weapons in preparation for the revolt: "The Jews

..purposely made of poor quality such weapons as they were called upon to furnish, in order that the Romans might reject them and that they themselves might thus have the use of them." However, there is no archaeological evidence to support Dio's claim that the Jews produced defective weapons. In fact, weapons found at sites controlled by the insurgents are identical to those used by the Romans.

Betar

The Betar Movement (), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionism, Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. It was one of several right-wing youth movements tha ...

(also Beitar, Bethar), a town situated at the edge of a mountain range southwest of Jerusalem, was chosen as the rebels' headquarters due to its strategic proximity to Jerusalem, abundant springs, and defensible position. Its ruins are now located at Khirbet el-Yehud, within the modern village of

Battir, which retains the ancient town's name. Excavations at the site have revealed fortifications likely built by Bar Kokhba's forces, though determining whether these defenses were constructed at the beginning of the revolt or later in the conflict remains unresolved.

The Bar Kokhba state

During the first year of the revolt, Bar Kokhba succeeded in establishing a functioning state, and life in Judaea appears to have continued with relative stability. This is evidenced by land lease agreements from the period involving substantial financial transactions. At the same time, the revolt disrupted Jewish communities beyond Judaea, as reflected in accounts of individuals fleeing from

Zoar in Transjordan to

Ein Gedi

Ein Gedi (, ), also spelled En Gedi, meaning "Spring (hydrology), spring of the goat, kid", is an oasis, an Archaeological site, archeological site and a nature reserve in Israel, located west of the Dead Sea, near Masada and the Qumran Caves. ...

sometime after 132 CE.

Military

Bar Kokhba led a well-organized army structured in a hierarchical system with designated ranks, including a "head of a camp." His letters indicate a clear chain of command, listing figures such as Judah bar Manasse, commander of Kiryath Arabaya, and Johnathan bar Beysayan and Masabala bar Simeon, commanders of

Ein Gedi

Ein Gedi (, ), also spelled En Gedi, meaning "Spring (hydrology), spring of the goat, kid", is an oasis, an Archaeological site, archeological site and a nature reserve in Israel, located west of the Dead Sea, near Masada and the Qumran Caves. ...

. These documents also suggest that his forces were composed of devout Jews. According to Rabbinic sources, some 400,000 men were at the disposal of Bar Kokhba at the peak of the rebellion.

Coinage

The new independent state minted its own coins. From the first year of the revolt, there are silver

tetradrachm

The tetradrachm () was a large silver coin that originated in Ancient Greece. It was nominally equivalent to four drachmae. Over time the tetradrachm effectively became the standard coin of the Antiquity, spreading well beyond the borders of the ...

s featuring the Temple on the obverse with the word "Jerusalem." On the reverse, a and are depicted, along with the inscription "Year One of the Redemption of Israel." As in the

Maccabean Revolt

The Maccabean Revolt () was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167 to 160 BCE and ended with the Seleucids in control of ...

and the First Jewish Revolt,

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

underwent a resurgence, its presence on coins and documents reinforcing its role as a symbol of Jewish nationhood and independence.

Bar Kokhba is depicted on the coins as "Simeon, Prince of Israel." Coins from the first year also feature the inscription "Eleazar the priest," though the identity of this figure remains uncertain and debated. Some scholars identify him as Eleazar, Bar Kokhba's uncle, who was executed for seeking negotiations with the Romans, according to rabbinic literature. Regardless, this suggests that Bar Kokhba may have been preparing for the Temple's reconstruction, appointing a

High Priest

The term "high priest" usually refers either to an individual who holds the office of ruler-priest, or to one who is the head of a religious organisation.

Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, a high priest was the chief priest of any of the many god ...

to officiate once it was restored. The coins suggest that restoring the Temple and its services was indeed a key goal, as they feature the Temple's facade and other related symbols.

For coins from the second year and undated coins, additional inscriptions appear, including "For the Freedom of Israel" and "For the Freedom of Jerusalem."

Geographic extent of the revolt

The exact extent of Bar Kokhba's control remains uncertain. It is widely agreed that the rebels held all of Judea, including the villages of the

Judaean Mountains

The Judaean Mountains, or Judaean Hills (, or ,) are a mountain range in the West Bank and Israel where Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Hebron and several other biblical sites are located. The mountains reach a height of . The Judean Mountains can be di ...

, the

Judaean Desert

The Judaean Desert or Judean Desert (, ) is a desert in the West Bank and Israel that stretches east of the ridge of the Judaean Mountains and in their rain shadow, so east of Jerusalem, and descends to the Dead Sea. Under the name El-Bariyah, ...

, and northern parts of the

Negev Desert

The Negev ( ; ) or Naqab (), is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. ), in the north. At its southern end is the Gulf of Aqaba and the resort town, resort city ...

. However, there are differing views on the broader scope of the revolt. Two main schools of thought have emerged: ''Maximalists'' argue that rebel control may have extended beyond Judea, incorporating other parts of the province, including

Galilee

Galilee (; ; ; ) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon consisting of two parts: the Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and the Lower Galilee (, ; , ).

''Galilee'' encompasses the area north of the Mount Carmel-Mount Gilboa ridge and ...

and the

Golan

Golan (; ) is the name of a biblical town later known from the works of Josephus (first century CE) and Eusebius (''Onomasticon'', early 4th century CE). Archaeologists localize the biblical city of Golan at Sahm el-Jaulān, a Syrian village eas ...

, while ''minimalists'' limit rebel control to Judea and its immediate surroundings.

[M. Menahem. ''WHAT DOES TEL SHALEM HAVE TO DO WITH THE BAR KOKHBA REVOLT?''. U-ty of Haifa / U-ty of Denver. SCRIPTA JUDAICA CRACOVIENSIA. Vol. 11 (2013) pp. 79–96.] Whether the rebels captured Jerusalem or resumed sacrificial worship on the Temple Mount remains unclear.

Until 1951, Bar Kokhba Revolt coinage was the sole archaeological evidence for dating the revolt.

[Hanan Eshel, 'The Bar Kochba revolt, 132-135,' in William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein, Steven T. Katz (eds.) ''The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4, The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period,'' pp. 105–127 05] Despite the reference to Jerusalem on the coins, as of early 2000s, archaeological finds, and the lack of revolt coinage found in Jerusalem, supported the view that the revolt did not capture Jerusalem.

[: "Returning to the Bar Kokhba revolt, we should note that up until the discovery of the first Bar Kokhba documents in Wadi Murabba'at in 1951, Bar Kokhba coins were the sole archaeological evidence available for dating the revolt. Based on coins overstock by the Bar Kokhba administration, scholars dated the beginning of the Bar Kokhba regime to the conquest of Jerusalem by the rebels. The coins in question bear the following inscriptions: "Year One of the redemption of Israel", "Year Two of the freedom of Israel", and "For the freedom of Jerusalem". Up until 1948 some scholars argued that the "Freedom of Jerusalem" coins predated the others, based upon their assumption that the dating of the Bar Kokhba regime began with the rebel capture Jerusalem." L. Mildenberg's study of the dies of the Bar Kokhba definitely established that the "Freedom of Jerusalem" coins were struck later than the ones inscribed "Year Two of the freedom of Israel". He dated them to the third year of the revolt.' Thus, the view that the dating of the Bar Kokhba regime began with the conquest of Jerusalem is untenable. lndeed, archeological finds from the past quarter-century, and the absence of Bar Kokhba coins in Jerusalem in particular, support the view that the rebels failed to take Jerusalem at all."]

In 2020, the fourth Bar Kokhba minted coin and the first inscribed with the word "Jerusalem" was found in Jerusalem Old City excavations. Despite this discovery, the Israel Antiques Authority still maintained the opinion that Jerusalem was not taken by the rebels, because more than 22,000 coins Bar Kokhba coins had been found outside Jerusalem but only four were found within the city. The Israel Antiques Authority's archaeologists Moran Hagbi and Dr. Joe Uziel speculated "It is possible that a Roman soldier from the Tenth Legion found the coin during one of the battles across the country and brought it to their camp in Jerusalem as a souvenir."

Among those findings are the rebel hideout systems in the Galilee, which greatly resemble the Bar Kokhba hideouts in Judea, and though they are less numerous, are nevertheless important. Excavations at

Wadi Hamam, near the

Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee (, Judeo-Aramaic languages, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ), also called Lake Tiberias, Genezareth Lake or Kinneret, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest freshwater lake on Earth ...

, uncovered the remains of a Jewish village that was destroyed during the reign of Hadrian, possibly during the revolt or shortly beforehand. However, the continued Jewish presence in the Galilee after the war has led some scholars to argue that the region either did not join the revolt or was subdued relatively early compared to Judea.

Several historians, notably W. Eck of the University of Cologne, theorized that the Tel Shalem arch depicted a major battle between Roman armies and Bar Kokhba's rebels in Bet Shean valley,

thus extending the battle areas some 50 km northwards from Judea. The 2013 discovery of the

military camp

A military camp or bivouac is a semi-permanent military base, for the lodging of an army. Camps are erected when a military force travels away from a major installation or fort during training or operations, and often have the form of large cam ...

of Legio VI Ferrata near

Tel Megiddo

Tel Megiddo (from ) is the site of the ancient city of Megiddo (; ), the remains of which form a tell or archaeological mound, situated in northern Israel at the western edge of the Jezreel Valley about southeast of Haifa near the depopulate ...

. However, Eck's theory on battle in Tel Shalem is rejected by M. Mor, who considers the location implausible given Galilee's minimal (if any) participation in the Revolt and distance from the main conflict flareup in Judea proper.

A 2015 archaeological survey in Samaria identified some 40 hideout cave systems from the period, some containing Bar Kokhba's minted coins, suggesting that the war raged in Samaria at high intensity.

Jews from Peraea are thought to have taken part in the revolt. This is demonstrated by a destruction layer dating from the early 2nd century at Tel Abu al-Sarbut in the

Sukkoth Valley, and by abandonment deposits from the same period that were discovered at al-Mukhayyat and

Callirrhoe. There is also evidence for Roman military presence in Perea in the middle of the century, as well as evidence of the settlement of Roman veterans in the area.

This view is supported by a destruction layer in

Tel Hesban that dates to 130, and a decline in settlement from the Early Roman to the Late Roman periods discovered in the survey of the

Iraq al-Amir region. However, it is still unclear whether this decline was caused by the First Jewish–Roman War or the Bar Kokhba revolt.

Bowersock suggested of linking the

Nabateans to the revolt, claiming "a greater spread of hostilities than had formerly been thought... the extension of the Jewish revolt into northern Transjordan and an additional reason to consider the spread of local support among

Safaitic

Safaitic ( ''Al-Ṣafāʾiyyah'') is a variety of the South Semitic scripts used by the Arabs in southern Syria and northern Jordan in the Harrat al-Sham, Ḥarrah region, to carve rock inscriptions in various dialects of Old Arabic and Ancient N ...

tribes and even at

Gerasa

Jerash (; , , ) is a city in northern Jordan. The city is the administrative center of the Jerash Governorate, and has a population of 50,745 as of 2015. It is located 30.0 miles north of the capital city Amman.

The earliest evidence of settl ...

."

[''The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered''](_blank)

by Peter Schäfer,

Foreign participation

According to Cassius Dio, the Jewish rebels were aided by "many outside nations," who were eager "for gain." Menachem Mor suggests that non-Jewish populations in the region may have indeed joined the revolt alongside the Jews, though their numbers are difficult to assess. These participants likely came from the lower classes in Hellenistic cities, motivated by a desire to undermine the Roman-backed aristocracy and improve their own socio-economic conditions.

Suppression of the revolt

After Legio X and Legio VI failed to subdue the rebels, additional reinforcements were dispatched from neighbouring provinces.

Gaius Poblicius Marcellus, the

legate of

Roman Syria

Roman Syria was an early Roman province annexed to the Roman Republic in 64 BC by Pompey in the Third Mithridatic War following the defeat of King of Armenia Tigranes the Great, who had become the protector of the Hellenistic kingdom of Syria.

...

, arrived commanding

Legio III ''Gallica'', while

Titus Haterius Nepos, the governor of

Roman Arabia, brought

Legio III ''Cyrenaica''. It is likely that

Legio XXII Deiotariana

Legio XXII Deiotariana ("Deiotarus' Twenty-Second Legion") was a legion of the Imperial Roman army, founded ca. 48 BC and disbanded or destroyed during the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132–136. Its cognomen comes from Deiotarus, a Celtic king of ...

was destroyed during the early stages of the revolt.

Following a series of setbacks, Hadrian called his general

Sextus Julius Severus from

Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

, and troops were brought from as far as the

Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

. In 133/4, Severus landed in Judea with three legions from Europe (including

Legio X ''Gemina'' and possibly also

Legio IX ''Hispana''), cohorts of additional legions and between 30 and 50 auxiliary units. They were joined by Hadrian himself who arrived in the province and commanded the campaign in person, at least for a time, as noted by Cassius Dio, This is supported by inscriptions describing an during which the emperor participated.

The size of the Roman army amassed against the rebels was much larger than that commanded by

Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September AD 81) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death, becoming the first Roman emperor ever to succeed h ...

60 years earliernearly one third of the Roman army took part in the campaign against Bar Kokhba. It is estimated that forces from at least 10 legions participated in Severus' campaign in Judea, including Legio X ''Fretensis'',

Legio VI ''Ferrata'', Legio III ''Gallica'', Legio III ''Cyrenaica'',

Legio II ''Traiana Fortis'',

Legio X ''Gemina'', cohorts of

Legio V ''Macedonica'', cohorts of

Legio XI ''Claudia'', cohorts of

Legio XII ''Fulminata'' and cohorts of

Legio IV ''Flavia Felix'', along with 30–50 auxiliary units, for a total force of 60,000–120,000 Roman soldiers facing Bar Kokhba's rebels. It is plausible that

Legio IX ''Hispana'' was among the legions Severus brought with him from Europe, and that its demise occurred during Severus' campaign, as its disappearance during the second century is often attributed to this war.

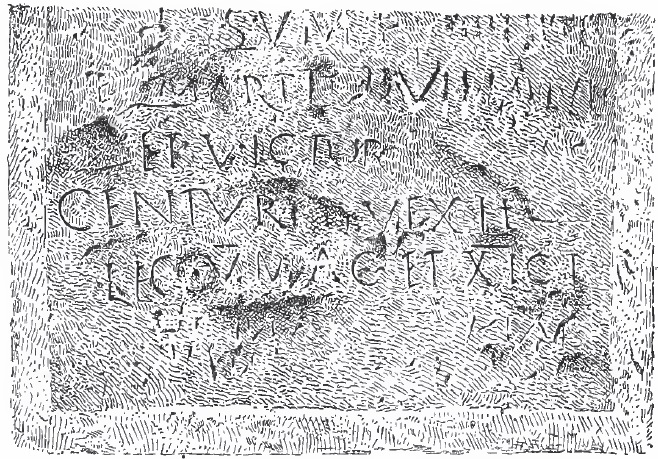

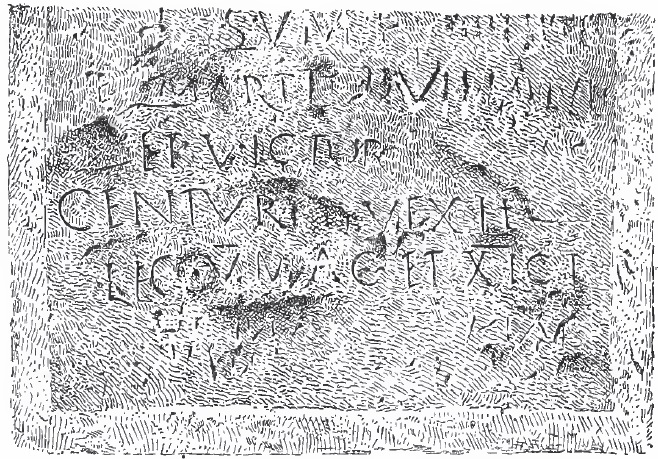

One of the crucial battles of the war took place near Tel Shalem in the

Beit She'an

Beit She'an ( '), also known as Beisan ( '), or Beth-shean, is a town in the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. The town lies at the Beit She'an Valley about 120 m (394 feet) below sea level.

Beit She'an is believed to ...

valley, near what is now identified as the legionary camp of Legio VI ''Ferrata''. This theory was proposed by

Werner Eck

Werner Eck (born 17 December 1939) is professor of Ancient History at Cologne University, Germany, and a noted expert on the history and epigraphy of imperial Rome.Eck, W. (2007) ''The Age of Augustus''. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, cover notes. Hi ...

in 1999, as part of his general maximalist work which did put the Bar Kokhba revolt as a very prominent event on the course of the Roman Empire's history. Next to the camp, archaeologists unearthed the remnants of a

triumphal arch

A triumphal arch is a free-standing monumental structure in the shape of an archway with one or more arched passageways, often designed to span a road, and usually standing alone, unconnected to other buildings. In its simplest form, a triumphal ...

, which featured a dedication to Hadrian, most likely referring to the defeat of Bar Kokhba's army. Additional finds at Tel Shalem, including a bust of Hadrian, specifically link the site to the period. The theory for a major decisive battle in Tel Shalem implies a significant extension of the area of the rebellion, with Eck suggesting the war encompassed also northern valleys together with Galilee.

Fall of Betar

After losing many of their strongholds, Bar Kokhba and the remnants of his army withdrew to the fortress of

Betar

The Betar Movement (), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionism, Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. It was one of several right-wing youth movements tha ...

, which subsequently came under siege in the summer of 135. Legio V ''Macedonica'' and Legio XI ''Claudia'' are said to have taken part in the siege. According to Jewish tradition, the town was breached and destroyed on

Tisha B'Av

Tisha B'Av ( ; , ) is an annual fast day in Judaism. A commemoration of a number of disasters in Jewish history, primarily the destruction of both Solomon's Temple by the Neo-Babylonian Empire and the Second Temple by the Roman Empire in Jerusal ...

, the ninth day of the lunar month of

Av, a day of fasting and mourning marking the anniversary of the destruction of the Second Temple.Talmudic tradition attributes the downfall of Betar to a Samaritan, who acted as a "

fifth column

A fifth column is a group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. The activities of a fifth column can be overt or clandestine. Forces gathered in secret can mobilize ...

" and sowed discord between Bar Kokhba and his maternal uncle, Rabbi

Eleazar of Modi'im

Eleazar of Modi'im () was a Jewish scholar of the second tannaitic generation (1st and 2nd centuries), disciple of Johanan ben Zakkai, and contemporary of Joshua ben Hananiah and Eliezer ben Hyrcanus.

Rabbinic career

Eleazar of Modi'im was an ...

. In this narrative, suspecting Eleazar of collaborating with the enemy, Bar Kokhba killed him with a single kick, forfeiting divine protection. Shortly thereafter, Betar was captured, and Bar Kokhba was killed. Scholars, however, consider this story to be a later addition with little historical value regarding the revolt. It is thought to reflect the deterioration of relations between Jews and Samaritans in the years following the revolt.

According to a Jewish tradition in

Lamentations Rabbah

The Midrash on Lamentations () is a midrashic commentary to the Book of Lamentations.

It is one of the oldest works of midrash, along with Genesis Rabbah and the '' Pesikta de-Rav Kahana''.

Names

The midrash is quoted, perhaps for the first ti ...

, when Bar Kokhba's body was shown to Hadrian, the emperor ordered that the rest of the body be brought forward. It was discovered with a snake coiled around his neck, and Hadrian is said to have commented, "If his God had not slain him, who could have overcome him?" According to another rabbinic legend, found in the

Babylonian Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the centerpiece of Jewi ...

,

Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Middle Aramaic , a loanword from , 'assembly,' 'sitting together,' hence ' assembly' or 'council') was a Jewish legislative and judicial assembly of either 23 or 70 elders, existing at both a local and central level i ...

, Bar Kokhba was executed by the sages after failing to meet the messianic expectation of judging "by scent" as described in

Isaiah 11:3–4, however, this account is generally regarded by scholars as legendary rather than historical.

The horrendous scene after the city's capture could be best described as a massacre. The Jerusalem Talmud relates that the number of dead in Betar was enormous, and that the Romans "went about slaughtering them until a horse sunk in blood up to its nostrils, and the blood carried away boulders that weighted forty

''sela'' until it went four miles into the sea. If you should think that it (Betar) was close to the sea, behold, it was forty miles distant from the sea."

Conclusion

According to ''Lamentations Rabbah'', Hadrian established three guard posts—in Hammat,

Bethlehem

Bethlehem is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, located about south of Jerusalem, and the capital of the Bethlehem Governorate. It had a population of people, as of . The city's economy is strongly linked to Tourism in the State of Palesti ...

, and Kefar Lekitaya—to capture Jewish rebels attempting to flee. He dispatched heralds announcing that Jews in hiding should come out to receive a reward from the emperor. Those who complied were surrounded and massacred in the Valley of Beit Rimmon. The identification of these locations has been the subject of scholarly debate. Kefar Lekitaya has been identified by some with Khirbet al-Kut, near

Ma'ale Levona

Ma'ale Levona (, lit. ''Ascent of Frankincense'') is an Israeli settlement organized as a community settlement (Israel), community settlement in the West Bank. Located to the south-east of Ariel (city), Ariel, it falls under the jurisdiction o ...

, while others associate it with

Beit Liqya, located along the

Emmaus

Emmaus ( ; ; ; ) is a town mentioned in the Gospel of Luke of the New Testament. Luke reports that Jesus appeared, after his death and resurrection, before two of his disciples while they were walking on the road to Emmaus.

Although its geograp ...

–Jerusalem road. Hammat has been variously proposed to correspond to

Hamat Gader in the Galilee or Hammata near Emmaus in Judea. Similarly, the Valley of Bet Rimmon has been located either in the

Lower Galilee

The Lower Galilee (; ) is a region within the Northern District of Israel. The Lower Galilee is bordered by the Jezreel Valley to the south; the Upper Galilee to the north, from which it is separated by the Beit HaKerem Valley; the Jordan Rift ...

, near Wadi Ramana, or in Judea, near the village of

Rimon, south of

Ba'al-hazor. According to scholar

William Horbury, these guard posts probably marked the boundary of the area surrounding Jerusalem from which Jews were now excluded.Following the fall of Betar, the Roman forces went on a rampage of systematic killing, eliminating all remaining Jewish villages in the region and seeking out the refugees. Legio III ''Cyrenaica'' was the main force to execute this last phase of the campaign. Historians disagree on the duration of the Roman campaign following the fall of Betar. While some claim further resistance was broken quickly, others argue that pockets of Jewish rebels continued to hide with their families into the winter months of late 135 and possibly even spring 136. By early 136 however, it is clear that the revolt was defeated. The Babylonian Talmud (''

Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Middle Aramaic , a loanword from , 'assembly,' 'sitting together,' hence ' assembly' or 'council') was a Jewish legislative and judicial assembly of either 23 or 70 elders, existing at both a local and central level i ...

'' 93b) says that Bar Kokhba reigned for a mere two and a half years.

Consequences

Destruction and extermination

The revolt had catastrophic consequences for the Jewish population in Judaea, resulting in massive loss of life, widespread enslavement, and extensive forced displacement. The scale of devastation surpassed even that of the

First Jewish–Roman War

The First Jewish–Roman War (66–74 CE), also known as the Great Jewish Revolt, the First Jewish Revolt, the War of Destruction, or the Jewish War, was the first of three major Jewish rebellions against the Roman Empire. Fought in the prov ...

, leaving

Judea proper in a state of desolation.

Shimeon Applebaum estimates that about two-thirds of Judaea's Jewish population perished in the revolt. Some scholars characterize these consequences as an act of

genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

.

[Totten, S. ''Teaching about genocide: issues, approaches and resources.'' p. 24]

/ref>

Describing the devastating consequences of the revolt, several decades after its suppression, the Roman historian Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history of ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

(–235) wrote: "50 of their most important outposts and 985 of their most famous villages were razed to the ground. 580,000 men were slain in the various raids and battles, and the number of those that perished by famine, disease and fire was past finding out, Thus nearly the whole of Judaea was made desolate."Peter Schäfer

Peter Schäfer (born 29 June 1943, Mülheim an der Ruhr, North Rhine-Westphalia) is a prolific German scholar of ancient religious studies, who has made contributions to the field of ancient Judaism and early Christianity through monographs, co-e ...

,Tannaim

''Tannaim'' ( Amoraic Hebrew: תנאים "repeaters", "teachers", singular ''tanna'' , borrowed from Aramaic) were the rabbinic sages whose views are recorded in the Mishnah, from approximately 10–220 CE. The period of the Tannaim, also refe ...

'', early rabbinic scholars, reflects the devastation, with recurring expressions such as "Who sees the towns of Judaea in their destruction..." and "When Judaea was destroyed, may it soon be rebuilt." To date, no site in the region has revealed a continuous occupation layer throughout the 2nd century AD. The findings show clear signs of devastation or depopulation within the first few decades of the century, followed by a period of abandonment.material culture

Material culture is culture manifested by the Artifact (archaeology), physical objects and architecture of a society. The term is primarily used in archaeology and anthropology, but is also of interest to sociology, geography and history. The fie ...

, which differed significantly from that of the earlier Jewish population.

Expulsion and enslavement

Jewish survivors faced harsh punitive measures from the Romans, who often used social engineering to stabilize conflict zones.Tisha B'Av

Tisha B'Av ( ; , ) is an annual fast day in Judaism. A commemoration of a number of disasters in Jewish history, primarily the destruction of both Solomon's Temple by the Neo-Babylonian Empire and the Second Temple by the Roman Empire in Jerusal ...

. According to Jerome, Hadrian "commanded that by a legal decree and ordinances the whole nation should be absolutely prevented from entering from thenceforth even the district round Jerusalem, so that it could not even see from a distance its ancestral home." Similarly, Jerome writes that Jews were only allowed to visit the city to mourn its ruins, paying for the privilege.

Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

writes: " ..all the families of the Jewish nation have suffered pain worthy of wailing and lamentation because God's hand has struck them, delivering their mother-city over to strange nations, laying their Temple low, and driving them from their country, to serve their enemies in a hostile land." Jerome

Jerome (; ; ; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known ...

provides a similar account: "in Hadrian's reign, when Jerusalem was completely destroyed and the Jewish nation was massacred in large groups at a time, with the result that they were even expelled from the borders of Judaea." '' Dialogue with Trypho'', a 2nd-century Christian apologetic text by Justin Martyr

Justin, known posthumously as Justin Martyr (; ), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian apologist and Philosophy, philosopher.

Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and a dialogue did survive. The ''First Apolog ...

, presents a theological dialogue with a Jewish fugitive from the Bar Kokhba revolt, then residing in Corinth, Greece

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, ...

.

Roman policy also involved the mass enslavement

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and deportation of Jewish captives, a practice also observed after the revolt of the Salassi (25 BC), the wars with the Raeti (15 BC), and the Pannonian War (c. 12 BC).Jewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora ( ), alternatively the dispersion ( ) or the exile ( ; ), consists of Jews who reside outside of the Land of Israel. Historically, it refers to the expansive scattering of the Israelites out of their homeland in the Southe ...

.[Powell, ''The Bar Kokhba War AD 132–136'', Osprey Publishing, Oxford, ç2017, p. 81] The 7th-century ''Chronicon Paschale

''Chronicon Paschale'' (the ''Paschal'' or ''Easter Chronicle''), also called ''Chronicum Alexandrinum'', ''Constantinopolitanum'' or ''Fasti Siculi'', is the conventional name of a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle of the world. Its name com ...

'', drawing on earlier sources, states that Hadrian sold Jewish captives "for the price of a daily portion of food for a horse."Jerome

Jerome (; ; ; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known ...

reports that following the war, "innumerable people of diverse ages and both sexes were sold at the marketplace of Terebinthus," adding that "For this reason it is an accursed thing among the Jews to visit this acclaimed marketplace". In another work, he notes that thousands were sold there.Egypt